43 minute read

David Eccles and the Origins of Utah Construction Company — Utah International

David Eccles and the Origins of Utah Construction Company — Utah International

BY THOMAS G. ALEXANDER

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints–Mormons– who succeeded in making an enduring mark on the history of Utah and the nation generally did so by several means.First,some succeeded in business:entrepreneurs like Charles W.Nibley in lumbering and sugar refining;Jesse Knight in mining;and Reed Smoot in various businesses come to mind.Others obtained higher education in the learned professions:John A.Widtsoe in science;William H.King in law;and Martha Hughes Cannon in medicine.Some like Nibley and Smoot also became Mormon religious leaders.Smoot,King,and Cannon also used their success in business or profession as a springboard into politics.Significantly, in contrast with religion and politics,polygamy or monogamy did not seem to matter in business.Charles W.Nibley was a polygamist,yet he rubbed shoulders with nationally and locally powerful investors and business associates.In the business world,only success seemed to matter.

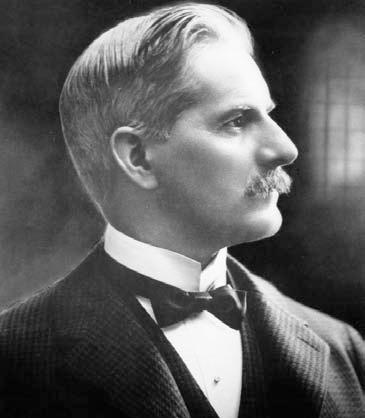

David Eccles

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

David Eccles was not a prominent religious leader, but belonged to the business group who also succeeded in politics. Born to abject poverty, Eccles achieved the American dream of significant success and personal wealth through hard work, careful planning, and an uncanny ability to recognize and capitalize on significant economic trends. In doing so he helped to establish successful firms in the lumbering, banking, and construction industries. In the latter field he became an organizer of one of the most internationally powerful Utah-based businesses–Utah Construction Company later renamed Utah International.

His story began in Paisley,Scotland,a market town and textile manufacturing center located about eight miles west of Glasgow that gave its name to a particularly attractive pattern of curved shapes woven into silk or cotton.In 1843,David’s father,William Eccles,then living in Paisley, married Irish immigrant,Sarah Hutchinson.1

A wood turner by trade,William Eccles moved with his wife to Glasgow in the hope of earning a better living.Astride the River Clyde,Glasgow was the major center in western Scotland and,at the time,Scotland’s largest city.During the mid-nineteenth century,the city grew 100 percent from 200,000 in 1830 to 400,000 in 1860.

William suffered from the growth of cataracts in his eyes,and to cope with his dimming vision,he learned to shape the products of his lathe by feel.Struggling just to survive in an age before modern medical care could have offered treatment for William’s disease,the Eccles family continued to grow.On May 12,1849,Sarah gave birth to David Eccles,who joined his older brother John among William’s and Sarah’s expanding family that eventually included seven children.2

Although laws in the United Kingdom required schooling for children, the need to keep starvation from the family’s door forced John,David,and their cousins James,John,and Stewart Moyes to labor from dawn to dusk.3 As a result,David had no more than a year of schooling in Scotland.4 For young David,schooling had become an unfulfilled dream.

Most people in Scotland heated their homes with coal,and lighted their fires with resin sticks.Seeing a means of support,the Eccles family began manufacturing resin fire lighters,and David became the family’s chief merchant.Driven by intense need and by an entrepreneurial spirit,David guided his burro cart far and wide from Glasgow,reaching Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital,forty-five miles east of his home.From the cart,he peddled resin sticks and the wooden kitchen utensils fabricated by his father.

Already,however,the family had begun to dream of a better life.Seven years before David’s birth and before William married Sarah,William and his mother,Margaret Eccles,had met Elder Andrew Sprowl a Mormon missionary.Following an introduction to the Book of Mormon,to Joseph Smith as God’s new prophet,and to the doctrine of gathering with the saints in America,William and his mother accepted baptism on February 5, 1842.In 1843,shortly after their marriage,William baptized Sarah.

Struggling to make ends meet,the family could not emigrate until 1863 when they received a grant of £75 (about $375) from the LDS Perpetual Emigrating Fund to travel to Utah.Arriving at Castle Garden,New York, the family traveled by rail and river boat to Florence,Nebraska,where they joined a wagon train bound for their new Zion.While on the trip west, John decided to return to Scotland,so David,at age fourteen,became the oldest child to accompany his family.

The family settled first in Ogden,then successively in Liberty and Eden in Ogden Valley.William again began turning utensils on the lathe,and David peddled the products from a pack in Ogden and Brigham City and points in between.

Because the Moyes cousins had trouble making a living in Utah, the two families moved to Oregon City, Oregon. William Eccles, David, now age eighteen, and his sixteen year-old brother, Stewart, found work cutting cordwood while the Moyes cousins worked in the woolen mills. The backbreaking labor of felling and sawing timber became David’s entrée into the business in which he grounded his fortune.5

After two years in Oregon,the Eccles family returned to Ogden in 1869 shortly after the joining of the Union and Central Pacific took place at Promontory Summit.Ogden soon became Utah’s transportation center and surpassed Provo to become the territory’s second largest city.

In the winter of 1869-70,David and Stewart sought additional work cutting and hauling hay and harvesting timber.David also contracted to freight goods to the Union Pacific railroad at South Pass,Wyoming,for a winter, and he returned to Eden where he worked on his father’s homestead.

The entrepreneurial spirit evident in his business ventures in Scotland, impelled him to disdain working for others.Capitalizing on the skills he had learned while in Oregon,he negotiated a contract to furnish logs for the Wheeler sawmill located at the confluence of Wheeler Creek and Ogden River just west of the present site of Pineview Dam.With his earnings he purchased a team of two oxen.To his great regret,an accident killed the oxen as they pulled logs for him.6

The death of his ox team forced him to return to work for others again. He worked for the Union Pacific’s Almy coal mine in Wyoming in 1871. Recognizing David’s industriousness,the boss gave him a job for which he had not qualified himself.Because of insufficient schooling he lacked sufficient arithmetic skills and soon lost the job as a bookkeeper for the company.Afterward Chinese workers,willing to work for much lower wages,replaced Euro-Americans in the jobs David could do.His boss fired him,and David returned to Ogden Valley where he again was engaged in logging.

Recognizing the need for a better education to supplement his entrepreneurial skill, David,during the winter of 1872-73 and again during a later winter, enrolled in a private school in Ogden run by Louis F.Moench in Ogden’s old city hall. 7 Moench,a well-educated immigrant from Germany’s Rhineland,later became the first principal of Weber Stake Academy (now Weber State University).He is best known today as lyricist of a familiar Latter-day Saint hymn,written first in German,and translated into English as:“Hark,All Ye Nations!”Although attending only for two terms,David learned enough to develop the skill of adding a row of figures at what seemed to observers like lightning speed.

The winter of 1872-73 proved extremely busy for the ambitious David. In addition to attending school,he negotiated a freighting contract to take a load of coffins from Ogden to the mining town of Pioche,Nevada.

David Eccles,standing on the far right in a Derby Hat,with employees at a lumber mill.

J. WILLARD MARRIOTT LIBRARY, THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH

During the summer of 1872,David had taken a contract to furnish logs for a mill owned by Bishop David James on Monte Cristo forty-five miles east of Ogden.After he finished the contract,he reached an agreement with two colleagues to share the cost of establishing a mill during the summer of 1873.He used a loan and the money he had earned from the coffin freighting contract as his share of the capital for the mill.The firm of Henry E.Gibson,W.T.Van Noy,and David Eccles operated the mill,and the following year they opened a yard in Ogden to sell their lumber.

David managed the mill on Monte Cristo,but found time to come down the mountain to Huntsville in Ogden Valley to dance.There,he renewed his acquaintance with Bertha Marie Jensen,whom he had seen previously in Huntsville and had met at Moench’s school.8 In contrast with David’s impoverished family,Bertha,a native of Pannerup,Aarhus, Denmark,had relatively well fixed parents.In spite of their social differences,the two fell in love and married in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City on December 17,1875.The marriage produced twelve children, six boys and six girls.9

After his marriage,David continued in the lumbering business.He logged and milled lumber on Monte Cristo first with Gibson and Van Noy, then just with Gibson.In 1881,after a dispute over Gibson’s trading of a span of horses that belonged to Eccles for some worthless oxen,he broke with Gibson and formed his own company.10

Convinced of the need to retail his own products,Eccles opened a lumber yard on the corner of 24th Street and Lincoln Avenue in Ogden which prospered,and which he always considered his main business.When he became bank president and president of Utah Construction Company, the lumber yard office remained his main office.Eccles soon moved his timber operation to Scofield,a coal mining area then in Emery County about forty miles northwest of Price.At the same time,he opened lumbering operations on the Wood River near Hailey and Bullion,Idaho.He also invested in an operation run by H.H.Spencer in Beaver Canyon,Idaho, near the Montana border.

While engaged in business with fellow Scotsman John Stoddard,who lived in Wellsville,Utah,David became interested in Ellen,one of John’s daughters.Ellen’s and David’s interest soon bloomed into love.Born in January 1867 and nearly eighteen years younger than David,Ellen was a couple of weeks shy of eighteen at the time of her marriage to David in the Logan LDS Temple on January 2,1885.Although the LDS church continued to encourage plural marriages,the federal government a year earlier inaugurated an intense campaign against polygamous Mormons,and David kept his marriage to Ellen secret.11 At various times she lived with her father’s family in Cache County,at Scofield,and in Oregon.The marriage produced nine children:five boys and four girls.12

Between 1884 and 1889 while continuing to run his lumber business, Eccles entered local politics.He served successively as an alderman, equivalent to a present-day combination city councilman and justice of the peace, and as mayor of Ogden. As mayor he bridged the gap between the Mormon and non-Mormon business communities, championing the organization of the Ogden Chamber of Commerce in April 1887.He also oversaw the construction of a new city hall.13 After he left the mayoral office, he and Thomas D. Dee sold the Ogden municipal water system, which they had previously purchased, to the city at a bargain price. Eccles believed that the culinary water should be a public utility rather than a private business.14

During his public service years in Ogden,David continued to expand his lumber operations,opening new timber stands in Oregon.The opportunity to market timber from these forests of the Mountain West and West Coast became part of the incentive for the construction of three more transcontinental railroads and a number of shorter regional lines.As a result during the 1880s,railroad logging boomed as entrepreneurs moved into the Rocky Mountains,California,and the Pacific Northwest to harvest evergreens.

Eccles had previously cut cordwood,logged,and cut timber for others in Utah.In the 1880s,however,he recognized that a large integrated lumbering operation situated on lush stands of evergreens and near a major railroad could supply ties the railroads needed.In 1883 he purchased a mill from John Stoddard to manufacture railroad ties at North Powder,Oregon. Organizing the firm of Spencer,Ramsey and Hall in 1887 with Thomas F. Hall,O.N.Ramsey,and H.H.Spencer,Eccles established sawmills at Viento,Oregon,and Chenowith,Washington.Fluming or floating logs to Viento,the company cut the logs into ties,loaded them on lumber cars, and shipped them out to the ever expanding web of railroads throughout the west.

In 1888,Eccles closed his Scofield operation and moved the mill to Telocaset,about thirty miles north of Baker,Oregon,and about eight miles from North Powder on the Union Pacific Railroad.Eccles’s loggers at Scofield had been cutting illegally on federal land,and after the inauguration of the Grover Cleveland administration in 1885,General Land Office Commissioner William A.J.Sparks began a sustained attack on illegal use of public resources.15 In addition,the GLO lumber inspectors had reportedly been extorting bribes from the company.

In 1887,Eccles began his association with Charles W. Nibley, and two years later Eccles and Nibley incorporated a larger company, encompassing Spencer ,Ramsey, and Hall into the Oregon Lumber Company. Nibley, a Scottish immigrant like Eccles, earned a fortune in lumbering and in the beet sugar business before and after accepting a call in 1908 as Presiding Bishop of the LDS church. Stockholders who held a controlling interest included Eccles, Nibley, Thomas D. Dee, N.C. Flygare, D.H. Peery, Joseph Clark, H.H. Spencer, Moroni Brown, Peter Minnoch, H.H. Young, and John Watson.16

In 1889,David moved Ellen’s family to North Powder,Oregon.A year later,Eccles and Nibley persuaded Union Pacific to use rails salvaged from other operations to construct a twenty-mile-long, narrow-gauge spur line from Salisbury,eight miles south of Baker,northeast through the Sumpter Valley to the town of Sumpter.Eccles invested in the new line.In addition,the UP contracted with Eccles’s firm to furnish five hundred thousand ties annually,which they shipped on the new line to railroad destinations.In 1891 the company shipped its first timber from Sumpter Valley and a year later,Eccles opened a saw mill in Baker.

Two-wheeled,one-horse carts were a vital part in the early days of building railroads by the Utah Construction Company.

STEWART LIBRARY, WEBER STATE UNIVERSITY

By 1893, the company had operations at Hood River,Meacham,North Powder,Baker,and Pleasant Valley.During the economic depression beginning in 1893 and the years that followed,Eccles’s company managed to weather the financial collapse in Europe and the United States,which had a devastating effect on Utah and the West.17 The company retained their employees because they honestly told the workers about the potential danger of continuing operations under the adverse conditions while promising the company would treat them fairly.

During the first decade of the twentieth century the company continued to expand its operation.In 1902,Eccles opened a mill at Inglis,Oregon, about forty miles northwest of Portland.The town lay on the Columbia River and on the railroad line.A year later,Eccles purchased the Lost Lake Lumber Company at Hood River,also on the railroad line and Columbia River,and consolidated it with the Oregon Lumber Company.In 1905, Eccles induced the Union Pacific to construct a spur line,the Hood River Railroad,from Hood River twenty-five miles south to Parkdale.This allowed Eccles access to lush stands of fir in the region.

In the meantime,Eccles had begun to invest in other businesses.He reluctantly bought stock in the Utah Sugar Company,the parent company of the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company.His reluctance arose from his belief that the company would have a difficult time succeeding in the competitive sugar market.In spite of his reservations,his connection with U and I proved a godsend.Thomas R.Cutler,U and I’s vice-president and general manager,introduced David to Henry O.Havemeyer,president of the American Sugar Refining Company,often called the Sugar Trust.Eccles and Havemeyer became friends,and that friendship proved extremely useful after Eccles invested in the Utah Construction Company.

Eccles also began to invest in banking,and it was the banking business that offered him entrée into Utah Construction.18 In 1881 a group associated with Horace S.Eldredge,then president of Deseret National Bank and manager of ZCMI,chartered the First National Bank in Ogden.The bank’s offices were on the corner of Washington Boulevard.and 24th Street.At the time,the only Ogden stockholder was N.C.Flygare.19 Two years later First National Bank had increased its capital from $100,000 to $150,000. David Eccles soon was elected to First National’s board of directors and in 1888,the board elected D.H.Peery president of the bank.In 1889,First National constructed a new building on the corner of Washington and 24th.In 1892,the board elected Eccles vice president,and two years later he purchased Peery’s stock,and the board elected him bank president. Eccles became a director of the Deseret Savings and Deseret National banks in Salt Lake City in 1898.These banks later became the basis for the First Security system of banks,now a part of the Wells Fargo Bank system.

As a faithful Latter-day Saint,Eccles responded to calls to help his church.Although he never served a mission,his sons served missions.He made his initial investment in the Utah Sugar Company which the LDS church had promoted because of a request from Apostle Heber J.Grant, one of the company’s directors.20 When LDS Church President Lorenzo

Snow decided to issue bonds to satisfy the church’s creditors,Eccles subscribed two hundred thousand dollars in bonds,again,at the request of Heber J.Grant.Eccles also paid off a seven hundred thousand dollar debt of the Ogden Fifth Ward by convincing Lorenzo Snow to allow the ward to credit Eccles’s tithing toward the payment of the debt.21

While David Eccles was amassing a fortune from lumbering,the earnings from which he invested in other business,two other Weber County young men,Edmund O.and William H.Wattis had also begun to make their mark in business.E.O.and W.H.farmed together in Uintah, but they also began taking grading contracts,often with their uncles George L.,Charles J.,Amos B.,and Warren W.Corey.

In 1881,the Corey brothers and Warren’s father-in-law,Ira N.Spaulding, organized the private Corey Brothers Construction Company.In the following years,W.H.and E.O.worked frequently on railroad construction for their uncles.

In 1886,the Wattis brothers joined with their uncles and a half-brother, Ira E.Spaulding,and incorporated Corey Brothers. 22 The corporation constructed railroads in Colorado,Wyoming,Montana,and Oregon,and a canal in Utah.Sometime after incorporating,David Eccles offered to purchase a share of the company,but reportedly the opposition from Warren Corey kept him out.Clearly,the tie-hacking operations associated with his lumber interests in Oregon,would have meshed extremely well with railroad construction,especially on a railroad line from Portland to Astoria for which Corey Brothers prepared the roadbed.

Already,Corey Brothers was financing its operations by borrowing fifty thousand dollars from Eccles’s First National Bank.For the Portland to Astoria job for which Corey Brothers,Inc.contracted to grade the railroad line,the contract required the railroad company to pay the contractors after the completion of each twenty miles of roadbed.As they proceeded with construction,the company ran short of funds,in part because they had to front the cost of construction.Financial problems arose,in addition,because a mining company in Nevada failed to pay them for construction work it had done there and in part because of the failure of financial institutions following the national economic collapse of 1893.23 When they failed to find financing to complete the railroad contract,local authorities auctioned their construction equipment to pay their obligations.

In the meantime,when Corey Brothers reached First National Bank’s lending limit of 10 percent of their capital,Warren Corey went to the bank to try to borrow more money.Bank officials told him that they could not lend more because of the limit,but referred him to David Eccles,the bank’s president at his office at the lumber company.When Corey contacted Eccles,Eccles told him that he wanted to talk first with W.H.Wattis,the company’s superintendent of construction.David asked Wattis:“What’s the matter? Why do you need more money?”Wattis replied that nothing was the matter “if we could get rid of the Coreys.”He told Eccles that the “job is not good enough for seven families to live off of.”24

Railroad construction workers for the Utah Construction Company pose in front of a partially completed trestle.

STEWART LIBRARY, WEBER STATE UNIVERSITY

Unable to meet their obligations as the 1893 depression deepened,the company filed for bankruptcy in 1895.To settle their debts,the Wattises and Coreys sold a great deal of their property in downtown Ogden and on the city’s east bench to the First National Bank.As a bankrupt company,Corey Brothers,Inc.passed into receivership,and the receivers sold the company’s assets now totaling about seven thousand dollars to a new company incorporated on November 6,1895,with a capital stock of ten thousand dollars as Corey Brothers Company.25

Significantly,in this new company,the Corey and Wattis brothers had a new set of senior partners,Thomas D.Dee,James Pingree,Joseph Clark, and David Eccles,all officers of First National Bank who now owned two-thirds of the Corey Brothers Company stock.Eccles held the largest block of shares with 36 percent,and Dee,Pingree,and Clark each held 10 percent.Among the Corey brothers,only Warren Corey and his wife Julia with 32 percent,and Amos Corey with 1 percent remained as stockholders. William H.Wattis also held only 1 percent.In what was an apparent effort to avoid a calamity similar to that experienced by the company in 1895, Eccles insisted that the company carry no long-term debt.

In a bow to the Corey-Wattis partnership,and because Eccles had confidence in William H.Wattis’s administrative and business ability,the new officers appointed him vice president and general manager.The new owners also elected Dee as president of the company and Pingree as secretary and treasurer.Since the company had come under the wing of the First National Bank,however,Eccles as bank president and largest stockholder became the major power in the company.

Soon,however,as Wattis had hoped,the new owners shut the Corey brothers out of management completely,and on January 8,1900,E.O.and W.H.Wattis together with their brother Warren L.Wattis incorporated Utah Construction Company.They subscribed stock worth $8,000 from an initial offering of $24,000.

A month later,on February 8,1900,David Eccles,Thomas Dee,James Pingree,and Joseph Clark met together with the Wattis brothers.Utah Construction had issued capital stock in the amount of $24,000,and the Utah Construction Company officers agreed to purchase Corey Brothers assets, except their books,for that amount.In the reorganization,the Wattis brothers and W.H.’s wife Marie held $8,000 in shares,the same number as David Eccles.Dee held $4,000 and Clark and Pingree $2,000 each.The directors reappointed W.H.Wattis as vice president and general manager and Dee as president.Wattis’s reappointment came on a motion from David Eccles,who had considerable confidence in the younger man’s ability.Eccles told his wife, Bertha,“that the Utah Construction Company was one business that he did not have to concern himself about and that Mr.Wattis knew the construction business and was competent to handle it.”He also had similar praise for E.O. Wattis whom he eventually placed in charge of the company’s San Francisco office.26 The one Corey relative they hired was Lester S.Corey,who served in various positions,and eventually became company president.

Under new management,Utah Construction still had to finish contracts that Corey Brothers had previously negotiated.27 Completing the Corey

A Utah Construction Company locomotive.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Brothers contracts,Utah Construction finished a number of other jobs including grading a road bed from Idaho Falls to St. Anthony,Idaho,for the Oregon Short Line,a subsidiary of New York railroad magnate Edward H.Harriman’s Union Pacific.

They also continued negotiating contracts for other small jobs.In 1900 Utah Construction contracted to grade a branch line of the Denver and Rio Grande to the booming Utah mining town of Park City.Afterward they graded a branch of the OSL from Blackfoot to Mackay,Idaho.At the same time they took a number of small contracts to change grades and curves or realign sections of the OSL line.Utah Construction hired a great many small subcontractors to work on these projects.28

In 1901,Utah Construction took a contract with the OSL to grade a line from its terminus near Modena in Utah to Las Vegas,Nevada.This construction project put OSL and Harriman’s Union Pacific system in competition with the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad owned by William Andrews Clark,a Montana banking,mining,and railroading entrepreneur who served in the United States Senate from 1899 to 1907.The Union Pacific had surveyed a line between southern California and Utah earlier,but Clark insisted that UP’s franchise for the rail line had lapsed because the company had failed to construct the railroad at the time.UP disagreed.This difference of opinion led to a frantic race between the two lines to complete construction through choke points–narrow canyons— where workers could construct only one line.

Both Utah Construction and the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad sent crews into the breach.At the choke points,construction crews actually graded roadbed between places where competing crews had already laid tracks.Lester Corey served as Utah Construction’s forwarding agent,and in that capacity made sure “hay,oats and other supplies”reached the camps ahead of the construction crews.29

A Utah Construction Company rock quarry in Tooele County photographed by Harry Shipler on May 25,1912.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

From this vantage point,Corey watched the progress and the confrontation as Utah Construction “sent men and teams overland to places as much as fifty or more miles ahead of the rail end.”Laying rails “at the rate of a mile per day,”the OSL people reached a choke point in Caliente Canyon, about sixty miles as the crow flies west of Modena,Utah,the last town before the tracks passed into Nevada.30 Crows,however,do not take the circuitous route that Utah Construction had to grade in order to pass down the canyon to Caliente on the Meadow Valley Wash in southeastern Nevada.

The Utah Construction crews reached Caliente Canyon before the LA & SL crews.Though the story is a bit unclear,Utah Construction must have already graded roadbed through the canyon since the OSL crews pulled in laying track on the way.When they got into the canyon,they found that the LA & SL crews had strung a wire fence across the roadbed. Behind the fence stood a squad of toughs armed with rifles aimed at the OSL track layers.OSL chief engineer,William Ashton ordered his men to push the construction cars up to the fence,where he dumped a small car of railroad ties across the fence.

In the face of the riflemen who had drawn their rifles to the firing position,Ashton jumped the fence “to call their bluff.”As it happened,the shooters were not bluffing–at least not exactly.As soon as he reached the other side of the fence,the riflemen greeted Ashton with a volley of shots.Fortunately, the shots were all bang and no lead because the shooters had loaded their rifles with blanks.Both sides laughed at the confrontation,and cooler heads prevailed.The Utah Construction crews packed up and returned to jobs in Utah and Idaho to carry out several “bank-widening”contracts.

The UP and LA & SL people took a year to negotiate an agreement. The line eventually became a part of the Union Pacific system,and Utah Construction returned to finish the road into Las Vegas.31 Significantly,one of the stations in Caliente Canyon is named “Eccles,”probably after David Eccles.

Eccles soon realized that Utah Construction would not really prosper if they continued to take small contracts for portions of railroad lines or for realigning completed lines as the Corey Brothers Company had done.He wanted to undertake a very large construction project,but needed help to negotiate it.His help came from Henry O.Havemeyer.As noted earlier, through the good offices of Thomas Cutler,Eccles had already met Havemeyer.(Cutler’s Utah-Idaho Sugar Company had sold a 51 percent interest to Havemeyer’s sugar trust.) In June 1902,after Cutler had introduced them,Havemeyer spent “most all day”in negotiation with Eccles.The wily New Yorker apparently thought he could wear Eccles down.Having cut his teeth on the rough and tumble of western business, Eccles held his own.Eccles recognized that he could not battle a powerful company like American Sugar Refining,so he bargained for the best deal he could.After having his fill of Havemeyer’s tactics,Eccles finally told him bluntly,“We don’t have to sell,we don’t owe a dollar—this is what we’ll do, this is my price and nothing under that.”32 Accepting Eccles’s proposal, Havemeyer purchased 51 percent of the Ogden,Logan,and Oregon Sugar Companies for more than the combined total value of the three companies,and he consolidated them into Amalgamated Sugar Company.33

Significantly, instead of detesting Eccles for his firm stand,Havemeyer found Eccles a capable and impressive businessman,and they became close friends.In Bertha Eccles’words,“Havemeyer didn’t lose any respect for him because he stood up for what he knew was right.”In fact,he kept Eccles on as company president.Later when Havemeyer sent one of his technical experts to investigate the Amalgamated Sugar Company plants,the expert returned with a complaint about the lack of advanced education of the men Eccles had hired as superintendents.Havemeyer defended Eccles by responding:“Any man Mr.Eccles employs as a superintendent or to work around the mill is satisfactory,and you must not interfere with Mr. Eccles.”34

Havemeyer’s friendship with Eccles proved more than propitious. Following the death of Collis P.Huntington in 1900,Edward H.Harriman gained control of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company.He already owned a controlling interest in the Union Pacific,and now with control of the SP,he effectively monopolized all railroad access from Salt Lake City to California.Previously,SP had divided its patronage between the Denver and Rio Grande and Union Pacific,but with the acquisition of SP,the first rate monopolist Harriman began to squeeze the D & RG.35

In the meantime,ownership of the D & RG had passed from Jay Gould to his oldest son,George J.who owned a controlling interest in railroads stretching from Buffalo,New York,to Ogden,Utah,and intended to extend that railroad from Baltimore to Oakland.To accomplish the western leg of this dream,Gould turned to E.T.Jeffery,president of the D & RG,in which Gould held a controlling interest.Gould and Jeffery tried to conduct surveys in secret over Beckwourth Pass and down the Feather River Canyon to Oroville,but Arthur Keddie and Walter Bartnett,who had long planned for such a railroad,learned of these efforts.Pressing Gould with claims they had already staked the route,Bartnett negotiated an agreement with Gould on February 6,1903,to provide for a new company to build the railroad.

On March 3,1903,a month after the two had signed this agreement and less than a year after Eccles had negotiated the sale of a controlling interest in his sugar plants to Havemeyer,eleven men sat down at the California Safe Deposit Building on California Street in San Francisco to sign an agreement to construct the Western Pacific from Salt Lake City to Oakland by way of Beckwourth Pass,the Feather River,and Oroville.Beckwourth Pass lay more than two thousand feet lower than Donner Pass which Southern Pacific controlled.Virgil Bogue,whom Gould sent west to conduct surveys,found that they could construct a road over that route with a grade of 1 percent,making it much more efficient than the Southern Pacific’s grade over Donner Pass.After word of the new railroad reached Ogden,the company officers learned that the contract for the western leg of the line from Oakland to Oroville had gone to E.B.and A.L.Stone of San Francisco.No one,however,had won the contract for the eastern end of the road from Oroville to Salt Lake City,which would cross the Sierra Nevada and span Nevada and western Utah.

No one in Utah Construction,except David Eccles,had an association with anyone with influence who could recommend them to Gould’s representatives.He was,in the words of Lester Corey,“the only one of our group who was known in eastern circles.” Moreover,Eccles firmly believed the company “could do the job,”so he agreed “to go to New York and see what could be done.” 36 Since he had a working relationship with Henry Havemeyer,Eccles went to see the sugar magnate

Because of Havemeyer’s confidence in Eccles’s business ability,he recommended Eccles to the WP officers.Eccles said Havemeyer “told [Gould and his associates] ...that anything that Eccles would sign his name to,they could be sure he would see it through.”37 Significantly,Eccles “personally obligated himself for the successful performance of the contract.”38

In what was probably the midst of these negotiations,Thomas D.Dee contracted pneumonia and died on July 11,1905.On August 7,vice-president W.H.Wattis called a meeting of the board of directors who elected David Eccles president of the company.

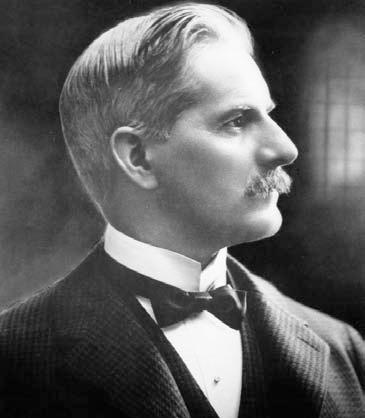

David Eccles,(left) and CharlesW. Nibley (right).

J. WILLARD MARRIOTT LIBRARY, THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH

On September 30 Eccles met with the board to ratify the first of the results of his negotiations.The directors agreed to sign the first of what appear to have been six contracts and seven supplemental contracts that authorized Utah Construction to prepare road bed for the laying of rails from Salt Lake City to Oroville. 39 The first contract obligated Utah Construction to grade between Salt Lake City and Silver Zone Pass that led through the Tono Range about 110 miles west of Salt Lake City.

Eccles tasked Andrew H.Christensen to supervise the contract from the Salt Lake City end,and Edmund O.Wattis to superintend the Oroville end.Each section of this line had its own problems.In crossing the Bonneville Salt Flats near Wendover,the construction crews faced a vast expanse of water-soaked salt lying on a bed of mud.Crews solved this problem by laying lumber on the salt,laying tracks on the lumber, and hauling “trainloads of earth and gravel”until the roadbed would hold the locomotives and train cars.40

Before 1905,the company had used nineteenth-century technology. Workmen had prepared the roadbed with horse-drawn plows,scrapers,and dump wagons.Crews blasted through rock with dynamite,but horsedrawn equipment did virtually all the earth moving.Since pneumatic drills available in the nineteenth century were bulky and difficult to move,crews did almost all drilling by hand to place dynamite and nitroglycerine.41

On the Western Pacific job,however,Utah Construction adopted new twentieth-century technology.Crews began to use “Air compressors,power drills,small steam locomotives,dump cars of four to eight cubic yard capacity,and steam shovels.”42 Lester Corey even set up a gasoline engine to run an air compressor,presumably to power a pneumatic drill.Significantly, although Utah Construction hired subcontractors for “lighter work,”the company’s crews did “much of the heavy grading with its own forces.”43

As construction neared completion in 1908,Utah Construction opened what they anticipated would be a temporary office in San Francisco.Eccles sent E.O.Wattis to head this office which was located in the Flood Building on Market Street between Turk and O’Farrell.After completion of the Western Pacific job,the company began to secure contracts for work on the West Coast,and instead of closing the “temporary”office,left it open.E.O.and his associates Henry J.Lawler,John G.Tyler,and John Q. Barlow aggressively sought contracts on the West Coast.44

With the exception of the difficulties encountered on Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats,Utah Construction crews had a relatively easy time completing the work through Utah and Nevada.However,the seventy-five mile Feather River Canyon in northwestern California between Keddie and Oroville seemed like something from another world.The canyon is so steep that the contour lines seem to lie on top of one another,and photographs from the canyon reveal a gloriously rugged landscape.In some places,surveyors had to hang by cables to drive in their center line and cut and fill stakes.45 Crews had to work hard to grade roadbed with only twenty degree curves.

Utah Construction crews blazed a trail and brought supplies by mule train,set up camps,and used these as bases for blasting out a wagon road to haul in provisions and equipment.Eleven men lost their lives working on a rope bridge and on the cliffs at Cromberg,five died in an explosion at Beckwourth Pass.At the confluence of Grizzly Creek,the crews had to raft around sheer cliffs.Utah Construction workmen blasted forty tunnels between forty and seventy-five hundred feet in length in addition to building bridges,trestles,cuts,and fills.E.O.Wattis moved his family to Oroville,just beyond the North Fork of the Feather River,and his daughter reported that they could hear the blasting from their home.

As construction proceeded,Utah Construction in general and David Eccles in particular faced a new problem caused in large part by the bank panic and recession of 1907.On October 22,1907,W.H.Wattis approached J.Dalzell Brown,WP’s treasurer,and asked him for payments due the company.Brown lied to Wattis insisting that the company did not have any money on hand,when,in fact,they had some Western Pacific deposits in the California Safe Deposit & Trust Company in San Francisco.Later,Brown, who was also treasurer,vice-president,and manager of California Safe Deposit sent Utah Construction and Wattis,who had returned to Salt Lake City,two checks totaling $236,735.28 drawn on California Safe Deposit.46

John Pingree,cashier of First National Bank of Ogden had left on business when the checks arrived,and James F.Burton,assistant cashier, received the checks and sent them to California Safe Deposit & Trust for credit instead of depositing them in the San Francisco clearing house in which First National generally did its business.Dalzell Brown and the other bank officers,however,knew something that neither Wattis nor Burton did. Throughout the month of October,California Safe Deposit was insolvent, perhaps as a result of the bank panic of 1907.In fact,only deposits of WP kept the bank from failing earlier,and the bank apparently tried to protect itself by paying only nominal amounts from the funds WP had deposited.Moreover, California Safe Deposit had not kept on hand the more than four hundred thousand dollars required by the State of California for its financial institutions.Thus,in an age before deposit insurance,First National stood at risk.

Employees at California Safe Deposit credited First National’s account for the checks on October 28,1907,but paid out no money.Safe Deposit proved quite an unsafe deposit,and it closed its doors on October 30.To compound the difficulty,and because of the recession,Western Pacific ordered construction curtailed to 40 percent of normal.In spite of WP’s curtailment,Utah Construction had obligated itself to pay its subcontractors their “retained percentages,”but WP did not have to pay Utah Construction.In effect,Utah Construction Company faced involuntary bankruptcy.47

David Eccles had guaranteed the contract with Western Pacific,so he felt personally responsible for the losses incurred by the California bank’s failure and the obligations to subcontractors.As a result,he negotiated a personal loan of $100,000 from Deseret Savings Bank which he gave to First National Bank.The remaining $125,000 came from Utah Construction’s undivided profits,80 percent in the bonds of two irrigation companies,and 20 percent in cash from the company’s coffers.Thus,Utah Construction and David Eccles absorbed the loss.Utah Construction,however,agreed to repay the bank for the losses,and though the documents on this matter are somewhat unclear,Eccles may have eventually recovered the money he advanced.48

After the completion of the contract,Utah Construction tried to recover its loss from Western Pacific.The railroad company insisted that since California Safe Deposit had credited Utah Construction with the two checks,it had incurred no liability.Since Safe Deposit was bankrupt,the checks were no good,Utah Construction’s officers believed that Western Pacific should repay.Officers of Utah Construction and Western Pacific agreed to submit their disagreement to arbitration and on April 29,1910, the two companies turned the dispute over to arbitrator Charles P.Ells.Ells ruled for Western Pacific,and in 1912 Utah Construction appealed to the California Superior Court in San Francisco.The California court also ruled in favor of Western Pacific and ordered Utah Construction to pay court costs and attorney’s fees to WP.Utah Construction appealed to the California Supreme Court,and on January 9,1917,five years after Eccles’s death,the Supreme Court upheld the lower court decision.49

In spite of this setback,Utah Construction had made its mark as one of the west’s major construction companies.The company received $22.3 million for a contract that kept its crews and subcontractors busy from January 2,1906 to November 1,1909.The company hired more than 7,700 workers on the project.It drew many of them from throughout Europe through an employment agency in Chicago.50

At about the same time that the company contracted to construct the WP line to Oroville,it also agreed to build a line for the Nevada Northern Railroad from Cobre,Nevada,on the Southern Pacific line southward to Ely.Mark Requa of the White Pine Copper Company projected the line to provide transportation for the products from the mine.For this project, Utah Construction planted telegraph poles and laid rails in addition to grading the roadbed.Construction of the 135 mile line took only a year–from September 1905 to September 1906 with fewer construction challenges compared to the Salt Lake Desert and the Feather River segments of the WP,but it added to the reputation of the company as a competent railroad builder.51

Eccles also purchased an interest in a large land and livestock company located in northeastern Nevada,which his son and the executor of his estate, David C.Eccles,sold to Utah Construction in 1913 to obtain money to pay his father’s inheritance taxes.At admission as a state,Nevada received a large allotment of land from the federal government.The terms of the grant allowed the state to select the land from the public domain,and since the state needed money immediately,it agreed to sell the land to Jasper Harrell and John Sparks,on favorable terms.In addition,Harrell and Sparks bought the holdings of homesteaders and purchased land scrip which they exchanged for more land.The outfit ran cattle herds on the land and on adjacent public domain.Sparks later became Nevada’s governor,and sold his interest to Harrell.After Harrell’s death,his daughter eventually obtained ownership of the vast land holdings and livestock operation but was uninterested and sold the land to a consortium consisting of David Eccles and the same associates who controlled Utah Construction and Utah National Bank. They incorporated it as “Vinyard Land & Stock Company.”52

Between 1908 and 1911 the company undertook a number of smaller projects which kept its construction crews busy.These included a $2.5 million contract for a line from Natron southeast of Eugene-Springfield to Oakridge on the Middle Fork of the Willamette in Oregon,and several small projects in Idaho,California,and Utah.

All of these activities proved extremely profitable.In 1900,David and the other incorporators had purchased the assets of Corey Brothers Company for $24,000;David had invested $8,000.Six years later the company increased the capital to $500,000 divided into 5,000 shares valued at $100.00 each.53 David Eccles died on December 5,1912,after suffering a heart attack while running to catch a train in Salt Lake City.At the time of his death the value of stock ($902,800) and undistributed profits ($1,415,315.81) of Utah Construction Company totaled $2,318,116.81.54

In 1971 when Leonard J. Arrington interviewed Marriner S. Eccles,a son of David Eccles and Ellen Stoddard Eccles,Marriner, then head of both the Utah Construction Company and First Security Corporation,told Arrington that Utah Construction was then worth in excess of sixty million dollars.“The Eccles family holdings,”he said,“in First Security are chicken feed compared to Utah Construction.”55 By today’s standards where billionaires seem to abound, his estate seems relatively small. David C.Eccles,administrator of the estate,valued it at $7,266,939.85, however,in 2007 dollars the estate would be worth more than $154 million. 56 Bertha received a widow’s share—one-third of the estate—and his children by Bertha and Ellen received equal shares of the remainder.As a plural wife,Ellen received none of the estate.His heirs paid an inheritance tax of $297,348.34.57

Eccles’s stocks in Utah Construction Company were valued at $235,000.58 This was the fifth highest valued block of stocks he owned, exceeded only by Amalgamated Sugar Company,Lewiston Sugar Company,Utah-Idaho Sugar Company,and Oregon Lumber Company.In effect,his $8,000 investment in Utah Construction in 1900 had grown nearly thirty fold in twelve years.

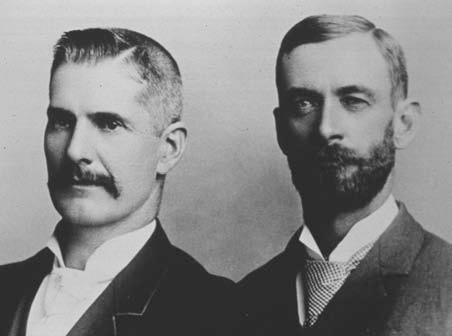

Thomas Dee.

UTASTEWART LIBRARY, WEBER STATE UNIVERSITY

To what did Eccles owe his success? The origins of his fortune lay in his hard work and thrift.During 1872 while he ran the mill on Monte Cristo for David James he seldom slept in a bed.He worked until dark,slept wherever he could find a place to nestle himself and began work again at dawn.He spent virtually none of the money that he earned,saving it instead as an investment to improve his situation as a capitalist.59 Although he had accumulated some debt during the early years,shortly after his marriage to Bertha he paid that off,and he ordered his business affairs so that he carried no long-term debt.

To understand David Eccles’s later success we must understand his early business efforts,and especially David’s enterprises in the lumber industry. His earnings in lumbering formed the basis for his fortune.Earnings in lumber provided the funds for his investment in the First National Bank of Ogden and in the sugar industry.His investment in the bank led to his investment in Utah Construction,and his investment in sugar led to Utah Construction Company’s first large contract.

He had excellent business acumen,and an extraordinary ability to recognize significant economic trends.He based his fortune on the lumbering business during a time of cheap or free land and a rapidly expanding market.Then,instead of carrying all his eggs in one basket,he diversified into eighty-three companies in a wide range of businesses ranging alphabetically from Adams Copper Mining & Smelting in Washington County,Utah,to ZCMI in Salt Lake City.

He was an excellent judge of the abilities of people with whom he associated and of opportunities that opened to him.He recognized the particular strengths of people like Thomas Dee,and William.H.and Edmund O.Wattis.

He knew how to cultivate the friendship of people who could help him. Without his association with Henry O.Havemeyer,it seems unlikely that Utah Construction would have obtained the large contract to construct the eastern leg of the Western Pacific Railroad Company’s grade.

Clearly Utah Construction Company owes much of the credit for the early success which provided a foundation for its future success to David Eccles.

NOTES

Thomas G.Alexander is the Lemuel Hardison Redd,Jr.Professor of Western American History Emeritus at Brigham Young University.My thanks go out to Beverly Ahlstrom and Tracy Alexander-Zappala for their help in research as well as Brooke Ann Alexander.Thanks also to Utah International for the opportunity to present this paper and to Richard Sadler,Joan Hubbard,John Sillito,and the staff of Special Collections at the Stewart Library at Weber State University for their help.Thanks also to Brad Cole and the staff of the Arrington Archives at the Merrill-Cazier Library at Utah State University and Greg Thompson and the staff of special collections at the Marriott Library at the University of Utah.Thanks to Lynn Wardle for his help.

1 Unless otherwise indicated,the treatment of the Eccles family in Scotland and David Eccles’work and entrepreneurial activities and families is based on Leonard J.Arrington, David Eccles,Pioneer Western Industrialist (Logan:Utah State University Press,1976),5-106.

2 Sarah Eccles Baird,“Memoirs,”1,David Eccles Papers,Series 3,Box 8,fd 3,Special Collections Stewart Library,Weber State University,Ogden,Utah.Hereafter,Special Collections,WSU.

3 The cousins’names are from Baird,“Memoirs,”2.

4 Bertha Eccles,“Memoirs of Bertha Eccles as Concerns Her Husband,David Eccles,”15,David Eccles Papers,Series III,Box 8,fd 15,Special Collections,WSU.

5 Baird,“Memoirs,”3.

6 Bertha Eccles,“Memoirs of Bertha Eccles as Concerns Her Husband,David Eccles,”23.

7 On the location of the school,see Eccles,“Memoirs of Bertha,”13.

8 Eccles,“Memoirs of Bertha,”13-14.

9 The additional information on the children comes from www.Familysearch.org

10 Bertha Eccles,“Memoirs….,”19-20.

11 On the campaign against polygamy,see Thomas G.Alexander,“Charles S.Zane,Apostle of the New Era,” Utah Historical Quarterly 34 (Fall 1966):290-314.

12 Information on the children comes from www.Familysearch.org

13 John Watson oral history interview,Ogden,Utah,September 20,1929,p 5,David Eccles Papers, Series III,Box 8,Special Collections,WSU.

14 Watson,oral history interview,p.6.

15 For more on the activities of William A.J.Sparks see Thomas G.Alexander, A Clash of Interests:Interior Department and Mountain West,1863-1896 (Provo:Brigham Young University Press,1977),90-95.On the complaints of Eccles’s operations at Scofield,see Alexander, The Rise of Multiple-Use Stewardship in the Intermountain West:A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service (Washington,D.C.:USDA Forest Service, 1987),9.

16 Watson oral history interview,6.

17 Leonard J.Arrington,“Utah and the Depression of the 1890s,” Utah Historical Quarterly 29 (January 1961):3-18;Ronald W.Walker,“Crisis in Zion:Heber J.Grant and the Panic of 1893,” Arizona and the West 21 (1979):257-78.

18 The treatment of Utah National Bank,First National Bank,and Ogden Savings Bank is based on First National Bank and First Savings Bank:Fifty-two Years of Leadership,1875-1927 (Ogden:First National Bank,1927).

19 Watson oral history interview,10.

20 For more on the Utah Sugar Company and its successor,the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company,see Leonard J.Arrington, Beet Sugar in the West:A History of the Utah Idaho Sugar Company,1891-1966 (Seattle: University of Washington Press,1966);and Matthew C.Godfrey, Religion,Politics,and Sugar:The Mormon Church,the Federal Government,and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company,1907-1921 (Logan:Utah State University Press,2007). Lorenzo Snow served as the president of the sugar company in 1901,p.177.

21 Watson oral history interview,12-13.

22 Salt Lake Tribune, January 1,1886,in Leonard J.Arrington History Archives (hereinafter LJAHA) Series IX,Box 99,fd,8,Special Collections,Merrill-Cazier Library,Utah State University,Logan,Utah (hereinafter USU).

23 For details on this see Royal Eccles Interview with W.H.Wattis,September 1929,Utah Construction Company Papers,Special Collections,WSU.

24 Leonard Arrington interview with Marriner S.Eccles,Salt Lake City,March 23,1971,LJAHA,1, Series VII,Box 30,fd 3:4,14,21,26,USU.Marriner Eccles is clearly confused about the dates.He placed the events in 1910,which was ten years after the dissolution of the Corey Brothers Company and the assumption of its assets by Utah Construction Company.I think that he has conflated the 1895 reorganization and the 1900 founding of Utah Construction Company and placed the events fifteen and twenty years after they actually occurred.

25 Articles of Incorporation of Corey Brothers Company,November 6,1895,Series 96/6,Company Histories Rough Drafts and Notes,Box 53,fd 3,Rought Draft & Notes by John McInerny,1974,Utah Construction Company Papers,Special Collections,WSU.For more information on the contractors in Springville,see Jay M.Haymond,“A Survey of the History of the Road Construction Industry of Utah,” (MA thesis,Brigham Young University,1967).

26 Eccles,“Memoirs…,”34.

27 Utah Construction purchased “all Contracts,credits,debts,due or owing;All the grading outfits, Horses,Harness etc.”Thomas D.Dee,and W.L.Wattis,Agreement between Corey Brothers and Utah Construction Company,January 8,1900,Series 60/1,box 9,fd 10,Utah Construction Papers,Special Collections,WSU.

28 Lester S.Corey,“Utah Construction & Mining Co.;An Historical Narrative,”(San Francisco:Utah Construction & Mining Co.,ca.1964),8-9,LJAHAI,Series VII,Box 30,fd 1;3,47,50-82,Special Collections & Archives,Merrill-Cazier Library,Utah State University,Logan,Utah.(Hereinafter,Corey, “Utah Construction,”with page number).

29 Corey,“Utah Construction,”9.

30 Ibid.,9-10.

31 Corey,“Utah Construction,”10.

32 Eccles,“Memoirs…,”33.

33 Arrington, David Eccles, 246.

34 Eccles,“Memoirs…,”32-34.

35 The following is based on G.H.Kneiss,“Fifty Candles for Western Pacific,”www.wpr rhs.org/wphistor y.html (accessed October 8,2007),and “Western Pacific:Oroville to Salt Lake City:‘Feather River Canyon Route,’”Utah Construction Company Papers,Box 65,fd 2,1.2 Western Pacific RR,Feather River Canyon Route,CA:1905-1910,Special Collections,WSU.

36 Corey,“Utah Construction,”14.

37 Eccles,“Memoirs…,”37.

38 “Western Pacific:Oroville,to Salt Lake City…”

39 Sterling D.Sessions and Gene A.Sessions, A History of Utah International:from Construction to Mining (Salt Lake City:University of Utah Press,2005),17.

40 Warren L.Wattis,Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Board of Directors of the Utah Construction Company,September 30,1905,Utah Construction Company Papers,Series 91,Box 40,fd 7,Special Collections,WSU;Minutes of Meeting of the Board of Directors of Utah Construction Company, November 23,1905,ibid.;“Agreement made and entered into this 31st day of October,1905…between Western Pacific Railway Company…and The Utah Construction Company,”ibid.;James Pingree, Resolution of Utah Construction Company,February 24,1906,ibid.

41 Corey,“Utah Construction,”15.

42 Ibid.,17-18.

43 Ibid.,15-16.

44 Ibid.,16.For the location of the Flood Building,see www.floodbuilding.com (accessed October 9, 2007).

45 Ibid.,19-20.

46 G.H.Kneiss,“Fifty Candles for Western Pacific,”www.wpr rhs.org/wphistor y.html (accessed October 8,2007);and Sessions and Sessions, History of Utah International, 17-19.

47 The best source on these matter is the plaintiff’s brief in Utah Construction Company vs.Western Pacific Railway Company,in the Superior Court of the State of California in and for the City and County of San Francisco,No.298274,July 11,1912,Series 91,Box 40,fd 7,Utah Construction Company Papers,Special Collections,WSU.

48 Plaintiff’s brief in Utah Construction Company vs.Western Pacific Railway Company;Royal Eccles interview with Sumner P.Nelson,Ogden,Utah,September 23,1929,David Eccles Papers,Series III,Box 8,fd 27,Special Collections,WSU;“Life of David Eccles:An incident pertaining to:First National Bank,Utah Construction Company,California Safe Deposit & Trust Company,”Box 7,Business (Resolutions of Respect),fd 13:First National Bank of Ogden,Utah Construction Co.,California Safe Deposit & Trust Co.,“Life of David Eccles,”nd,Special Collections,WSU.

49 Plaintiff’s Brief in Utah Construction Company vs.Western Pacific Railway Company;Utah Construction Co.vs.Western Pacific Railway Co.,174 California Reporter 156,and 162 Pacific Reporter 631 (January 9, 1917).A Utah company did not stand much of a chance of beating a California company in a California court in 1912,but might have stood a better chance had they filed in federal court.Conversation with Lynn Wardle,October 10,2007.

50 Sessions and Sessions, History of Utah International, 17-18.

51 Sessions and Sessions, History of Utah International, 19.

52 Corey,“Utah Construction,”21-24;Arrington, David Eccles, 253.

53 William H.Wattis and James Pingree,“Certificate of Amendment to the Articles of Incorporation of The Utah Construction Co.’’March 19,1906,Utah Consrtuction Company Papers,Series 60/1,box 9,fd 12,Special Collections,WSU.

54 “Statement of Resources and Liabilities,The Utah Construction Company,December 31,1912,”MS 100,Box 33,fd 3,2.3 Financial Statements:1912-1919,Utah Construction Company Papers,Special Collections,WSU.

55 Arrington interview with Marriner Eccles,2.

56 I have used the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis,Minnesota’s data to calculate the comparative value which was $154,131,776.See www.Mineapolisfed.org/Research/data/us/calc/hist1800.cfm (accessed October 15,2007).

57 David C.Eccles to Jesse D.Jewkes,June 1,1914,Box 9,fd 25,David Eccles Papers,WSU.

58 Untitled list of stocks and bonds,March 11,1913,Box 9,fd 23,David Eccles Papers,WSU.

59 Eccles,“Memoirs of Bertha,”19-20.