42 minute read

A Terror to Evil-Doers: Camp Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and Utah’s Civil War

A Terror to Evil-Doers: Camp Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and Utah’s Civil War

By WILL BAGLEY

In September 1863, Captain George Price’s Company M, Second California Volunteer Cavalry, stopped Mormon overland companies hauling freight and emigrants to Utah Territory to search for contraband. The confrontation between the troopers and three overloaded “church trains” illustrates the tensions between representatives of the federal government and Latter-day Saints during the Civil War. Twenty-five “U.S. Soldiers made their appearance and requested both aliens and citizens to take an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the United States, which we did,” wrote William McLachlan. The officers “caused our Captain J. W. Woolley to take an oath that he had no Powder or Ammunition in his possession only that necessary for his own protection and those under his charge.” 1 Farther west, a “compy of Armed Mounted Men Calling themselves, U.S. Soldiers” rode in between wagon trains under Isaac Canfield and Daniel McArthur. Both wagon trains had taken a detour to the Muddy River “to save the Cattles Feet,” a dangerously dry detour around Fort Bridger. McArthur said his “Oxen had had no water for two days & but verry little feed & he was afraid on account of the Roughness of the Road they would give out & die” if they were compelled to return to Fort Bridger. He “had broken no Law & had the right to travel which Road he Knew to be the best for his Cattle & also for the Passengers.”2 Given the route’s aridity when compared to the traditionalMormon Trail, it was an odd claim.

A map of Camp Douglas in June 1864.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The officer said “his orders were to convey us to the Fort, and to the Fort we must go,” reported journalist Edward Sloan. The soldiers gave vent to “their strong desire to pitch into the damned Mormons, one fellow saying, ‘Why the hell dont he give us the order and let us end the matter, without all this damned palavering’?” At a campground near the fort, the soldiers indulged “in a abundance of jeers, coarse jokes and abuse at our expense.” The post commander “affected to look upon us as Secessionists,” but took McArthur’s “word for the contents of the wagons, and postponed the ceremony of swearing.” The next morning, the soldiers mustered the persecuted “citizens of the Republic” inside the wagon corral “and had the oath of allegiance administered to them, after which the aliens were sworn to neutrality between the belligerent North and South. This concluded the entire business for which we were dragged across the country, like prisoners taken in arms,” Sloan wrote. The Mormons composed a protest and demanded five hundred dollars compensation for their trouble, but the officer in charge “declared his inability to do anything in the matter.”3

This incident, in which suspicious federal officials confronted Latter-day Saints who vehemently protested the violation of their rights, is familiar to students of Mormonism’s frontier history. Brigham Young decried the infringement of his followers’ Second Amendment rights: “Who have said that ‘Mormons’ should not be permitted to hold in their possession fire-arms and ammunition? Did a Government officer say this, one who was sent here to watch over and protect the interest of the community, without meddling or interfering with the domestic affairs of the people?” Young claimed, “I know what passes in their secret councils. Blood and murder are in their hearts, and they wish to extend the work of destruction over the whole face of the land.”4 For its part, the army acted under the authority of the Second Confiscation Act, which Congress passed on July 17, 1862, to give federal authorities broad powers “to suppress Insurrection, to punish Treason and Rebellion, to seize and confiscate the Property of Rebels.”5 The army had good reason to suspect LDS church trains were smuggling gunpowder into Utah Territory. “A company of Brethren [who] were Sent out by President Young to Green river to meet the trains that had powder, as a Company of U. S. Soldiers were Stationed near Hams Fork to Search the trains as they Passed,” wrote William McLachlan. At the Green River, “18 of the Boys with mules” greeted the Woolley party. The next morning “they left Green River with their mules loaded with Powder from Hector Haights train, on their mountain trail.”6 Teamster William Richardson recalled the trouble. The army suspected the train was carrying “two or three wagon loads of powder. They were afraid that if the powder got into Salt Lake City the Mormons would kill all the Gentiles in Camp Douglas.” An officer took Captain Haight to his tent and interrogated him for several hours, as the Mormons took “the Wagon with the pooder” across Green River and into the mountains, unloaded “the pooder into sacks & came back the nixt day.” That night, when troopers “sarched all the train,” they “did not find the lood of pooder then thay told us to go,” Richardson wrote.7

The confrontation on Hams Fork took place ten weeks after the battle of Gettysburg and two months before Abraham Lincoln visited the battlefield. The president went “to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.” Lincoln asked Americans engaged in a great civil war whether “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” or “any nation so conceived and so dedicated, could long endure.”8 Meanwhile, 2,019 miles to the west, a similar question was being asked in Great Salt Lake City.

Between 1862 and 1865, an American Moses and the Gaelic founder of Camp Douglas personified the conflict in Utah Territory. Ex-governor Brigham Young, one of the most famous men of his time and place, clashed with Patrick Edward Connor, a fiery Irish immigrant born in County Kerry on St. Patrick’s Day in 1820. Connor was a former First Dragoon, Texas Foot Rifleman, captain in the War with Mexico, and the contractor who laid the foundation for California’s state capitol. As commander at Camp Douglas, for three years the pugnacious Connor served as the military representative of federal power in Utah Territory, while the equally pugnacious President Young led the LDS church and a theocratic “ghost government” known as the “State of Deseret.” Both men held the other in sheer contempt and spewed inflammatory rhetoric as the debate between two of Utah’s most histrionic characters produced some of the Civil War’s most colorful language, posturing, and bombastic exchanges.

Patrick Edward Connor.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Utah’s history, to use Elliott West’s phrase, is contested ground. The story of the founding of Camp Douglas on Salt Lake City’s east bench 150 years ago illuminates why Utah’s history is so problematic—and why perceptions of the outpost’s early years are so partisan. Today revisionist and nuanced schools of Utah history debate whether the Latter-day Saints were loyal to a democratic republic as their prophets happily predicted the demise of the Union, or whether the religious leaders of Deseret, who had seen their beloved prophet murdered and had suffered mighty indignities during the Utah War, owed anything to agents of American imperialism who trampled their rights. The Civil War sesquicentennial, the opening of previously unavailable or obscure sources, and revolutionary research technology allow a revisionist to ask hard questions. Why was Mormon support for the Union so equivocal, and how did Abraham Lincoln manage his relations with Brigham Young? How much of Colonel Connor’s indictment of Mormon tyranny, treachery, and treason was the petrified truth? Were Mormons and Indians persecuted victims of American imperialism or active participants in a conflict in which both sides gave as good as they got? Finally, how much of Utah’s beloved Civil War mythology is not merely nuanced but fabricated?

The argument about Utah’s loyalty to the nation began soon after the territory’s creation. It already had a contentious history when two Sacramento Union correspondents renewed the debate December 1862. T. B. H. Stenhouse described how a “good many blue overcoats” in “the great Tabernacle” listened to loyal Latter-day Saints sing the “Star Spangled Banner,” “Yankee Doodle,” and “The Flag of Our Union” to deafening applause. Stenhouse is best remembered for his exposé of the Rocky Mountain Saints, but until his excommunication in 1869 he was Mormonism’s foremost intellectual defender. “Enfield,” the unidentified but high-caliber army correspondent, dismissed Mormon protestations of loyalty as “merely of the lips, nothing more,” and described how “sundry incendiary, ranting speeches” of John Taylor and Brigham Young worked the Saints up to “a fever heat of rebellion against the constituted authorities.”9

Mormon loyalty was complicated. An 1832 Joseph Smith prophecy said civil war would begin with “the rebellion of South Carolina” and the South would “call on other nations, even the nation of Great Britain.” The revelation predicted war would “be poured out upon all nations,” and told of a slave revolt, the uprising of “the remnants [of Israel] who are left of the land” (a reference to American Indians), famine, plagues, earthquakes, and vivid lightning “until the consumption decreed hath made a full end of all nations” and the blood of the Saints was “avenged of their enemies.”10

Johanna Connor, wife of Patrick Edward Connor.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Such apocalyptic beliefs suggested “a bond of sympathy between the Confederates and the people of Utah,” observed Utah Agricultural College professor Franklin Daines. Mormon leaders believed the Union was doing as much to destroy the Constitution as the Secessionists, so the “despised Mormons were hence the only loyalists,” but this “was loyalty to an ideal Government, not then in existence.” Utah’s professions of loyalty did not seem to convince Lincoln, who kept the army there “to make sure of having there a loyal force.”11 Brigham D. Madsen explained the Mormon perspective: despite statements by “second president” Heber C. Kimball that “the Government of the United States is dead, thank God it’s dead,” LDS church leaders believed the Constitution was a divine document and “continued to sustain the nation throughout the Civil War.” Yet this unique brand of loyalty was dedicated to the belief that all earthly kingdoms would be destroyed and the Kingdom of God would triumph, regardless of who won the Civil War. “No wonder Connor and others interpreted Mormon rhetoric and actions as signs of disloyalty,” Madsen noted.12

Some writers—including this one—have concluded Brigham Young remained carefully neutral during the conflict. But as E. B. Long observed, the Mormons condemned both sides, which ardent Unionists interpreted as proof of the Mormons’ basic disloyalty. “At such a moment of passion, any group which did not support either side wholeheartedly was suspect by both sides.” The Saints “were suspicious of Lincoln and critical, particularly in the early days of his presidency.” They might have held him in even greater disfavor than the documents he had seen indicated, Long noted.13 Recent evidence confirms Mormon leaders were more sympathetic to the Confederacy and critical of Lincoln than skilled historians concluded. Before hostilities began, Young claimed American officers “hate the Mormons because they feel they will rule the world.” He predicted a slave revolt in which both slaves and their masters “will be slaughtered by thousands.” Young regretted how many innocents would be killed, but he was “like the woman who saw her husband fighting with a Bear”: when he asked for help, she said, “I have no interest in who whips [whom].”14

In August 1861, President Young’s office journal reported, “the Brethren are gratified by hearing of the continued success which attends the Southern Confederacy.” Latter-day Saint leaders saw the conflict as God’s vengeance on the nation for countenancing the murder of their founding prophet. “Every move that has been made by the Government has been made to fulfil the sayings of Joseph,” Young said. It would now “be death upon death, and blood upon blood until the land is cleansed,” he preached.15 “The nation, as a people, objected to the Lord’s calling upon his servant Joseph, and sending him as a teacher to this generation,” he said. Americans had a right to reject the prophet’s revelations and God’s servants, but “the Lord has the right to come out from his hiding place and vex the nation. He too has rights. They had a right to kill Joseph, and the Lord has the right to destroy the nation.”16 Brigham Young conceded Lincoln might be sagacious, but he was no friend to Christ and “as wicked a man as ever lived.”17 He called “Abe Lincoln and his minions” cursed scoundrels “who have sought our destruction from the beginning.”18 The prophet considered the president “a damned old scamp and villain,” and did not believe “that Phoraoh [sic] of old was any worse, or any wickeder” than “old Abe Lincoln.”19

To grasp the significance of Camp Douglas requires understanding Utah in 1862. The arrival of the U.S. Army in 1858 had dramatically shifted the balance of power in the territory. The Utah War taught Brigham Young the perils of open defiance of the federal government, while the repeated failure of his apocalyptic prophecies increased the level of dissent. The last soldiers left the Wasatch Front in July 1861, and for fifteen months there would be virtually no military presence in Utah, or the security the army offered to disillusioned Latter-day Saints. The events that took take place during that time would, as historian David Bigler observed, “make this period among the most significant and revealing in the history of Utah Territory.”20

The interval saw the completion of the Pacific Telegraph line at Great Salt Lake City in October 1861. The Pony Express had reduced the time it took a letter to get from Missouri to Sacramento to ten days, but now the news of Abraham Lincoln’s election reached California in seven days and seventeen hours.21 Wherever the talking wire spoke, the telegraph changed everything. “Utah has not seceded but is firm for the Constitution and laws of our once happy country, and is warmly interested in such useful enterprises as the one so far completed,” President Brigham Young telegraphed in the first eastbound message.22 “Young was careful with his language,” historian John Turner concluded. “He was ‘firm’ for the Constitution, not for the Union or its present government. In short, Young and most of his coreligionistswere simply pro-Mormon during the crisis.” The Mormon president “did not wish Utah mixed up with the secession movement,” but Young “would be glad to hear that [Confederate] General Beauregard had taken the President & Cabinet and confined them in the South.”23

In April 1862, Indian raiders shut down the Overland Stage Line and a militia escort left Great Salt Lake City, “to guard the mail stage and passengers across the Indian-infested plains.” Brigham Young’s business agents, William Hooper and Chauncey West, and politicians in his favor “concluded not to wait any longer for the mail, but will start in the morning with an escort under the command of Col. Robert Burton.”24 A “company of cavalry for service of ninety days to protect the overland mail and telegraph against

Indian attack” followed Burton on May 1, under Lot Smith, best remembered for burning U.S. Army supply wagons in 1857. 25 Colonel Burton commanded a more dramatic military action on June 15, 1862, when five Utah militia companies brutally suppressed the followers of Joseph Morris. 26 Brigham Young (and a host of historians) used his contribution of a militia company to protect overland communications and standing “firm for the Constitution” as examples of his loyalty, but the murders of the Morrisite leaders provided a more revealing example of Mormon power.Young’s refusal to extend the enlistment of Lot Smith’s company—the sole military support Utah provided to the Union during the Civil War—compelled Lincoln to secure that force elsewhere.27

Monument in the Fort Douglas Cemetery to commemorate the Union dead at the Bear River massacre.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

President Lincoln kept abreast of affairs in the West and exhibited a distinct talent for managing Utah Territory, an accomplishment that few politicians could claim. “There is a batch of governors, and judges, and other officials here, shipped from Washington, and they maintain the semblance of a republican form of government,” James Street told Sam Clemens in 1861, “but the petrified truth is that Utah is an absolute monarchy and Brigham Young is king!” 28 It took only three weeks for John Dawson, the Indiana newspaper editor Lincoln appointed as Utah’s territorial governor, to learn that lesson in December 1861. On his arrival, Dawson called on the legislature to raise $26,982 as a federal war tax. Brigham Young complained the government would first want the taxes and then “they will want us to send 1,000 men to the war.” He would “see them in Hell before I will raise an army for them.” Take a man like Dawson who had been “an Editor for 15 years and you will find him to be a Jackass,” the Mormon prophet said.29 After Dawson vetoed a plan to win statehood for Deseret, someone took five shots at a federal judge in front of the governor’s rooms. Local authorities laughed it off and produced a widow’s affidavit charging the governor with making an indecent proposal. He got the message. On December 31, Dawson boarded an eastbound stagecoach, saying his health “imperatively demanded” he return home.30

Nobody ever had a worse New Year’s Eve than Governor Dawson. He told Lincoln “a band of Danites,” a rough set of young Mormon toughs, followed him from Salt Lake City. That night the crowd at Ephraim Hanks’s Mountain Dell stage station got drunk. Stage driver Wood Reynolds, a relative of the insulted widow, knocked the governor down and he was “viciously assaulted & beaten.” Lot Huntington and his hoodlums wounded “my head badly in many places, kicking me in the loins and right breast until I was exhausted” and then carried “on their orgies for many hours in the night,” Dawson said. On New Year’s Day the Deseret News reported Dawson had hired the gang that beat him up to “guard him faithfully and prevent his being killed or becoming qualified for the office of chamberlain in a kings palace.”31 Dawson’s congressman later “laughingly” informed George Q. Cannon that he “had been half emasculated.” Cannon insisted “the story in our country was that he was only whipped,” but Dawson’s doctor had informed the congressman “that an operation had been performed.”32

The ruffians claimed the chief of police had ordered the assault, but within a month most of them were dead at the hands of either Deputy Sheriff Orrin Porter Rockwell or the Salt Lake City police. In June 1863, Indians killed and scalped Wood Reynolds and another stage driver. They “brought the scalps of the poor men they killed” to Nephi and proudly displayed them. Mormon convert Phebe Westwood, an 1853 emigrant and wife of the Fort Crittenden overland agent, informed her husband she saw the scalps and “got dreadfully excited” when the bishop “treated the Indians with tobacco and ordered the people to feed them.” The incident angered her so much she “pitched into them and told them what I thought of them, and then I felt better.”33

There was little love lost between Utah’s religious leaders and the governor sent to replace Dawson. Stephen Harding arrived at Great Salt Lake City on July 7, 1862. “And that thing that is here that calls himself Governor,” Brigham Young said in October, “If you were to fill a sack with cow shit, it would be the best thing you could do for an imitation.”34 Abraham Lincoln had more pressing concerns than affairs in Utah or the Mormon petitions asking him to replace officials their prophet despised, but he listened to their complaints. After the South’s Army of Northern Virginia vanished on June 7, 1863, Lincoln met with Mormon journalist T. B. H. Stenhouse. He made typically “free jocular remarks about Hardin or Harding, or some such name that somebody had got him to appoint Governor of Utah.” Stenhouse explained the difference between the Mormon “position with the Indians, to that of the soldiers & the Indians.” Lincoln “sustained the settlers in keeping out of hostilities with the Indians.” The president hoped “his representatives there would behave themselves, & if the people let him alone, he would let them alone.” That was the substance of Stenhouse’s description of the encounter in a letter to Brigham Young two days later.35 His 1873 exposé of the Rocky Mountain Saints barely mentioned Lincoln and said nothing about the conversation.

Printing office of the Union Vedette at Fort Douglas. Photo taken in 1868.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Over time, writers adorned Stenhouse’s brief report with a story first told in 1886 to invent one of the most charming and oft-cited anecdotes in Mormon history. General James B. Fry, the son of an old friend of the president, knew Lincoln well. Among Fry’s “vexatious duties” as ProvostMarshal was fielding complaints about the draft from belligerent governors who took their ultimatums to the highest authority. One governor, probably Horatio Seymour, returned entirely satisfied. Fry assumed it required large concessions to deflect the governor’s “towering rage,” but Lincoln assured him, “Oh, no, I did not concede anything. You know how that Illinois farmer managed the big log that lay in the middle of his field!” The log “was too big to haul out, too knotty to split, and too wet and soggy to burn,” so the farmer ploughed around it. Lincoln said that was how he got rid of the governor—“I ploughed around him.” It took three hours to do it, and Lincoln “was afraid every minute he’d see what I was at.” The president, Fry observed, “was a good judge of men, and quickly learned the peculiar traits of character in those he had to deal with.”36

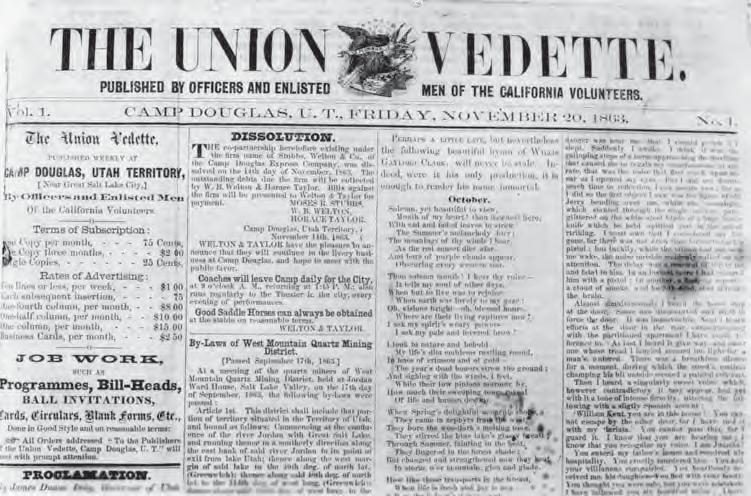

The November 20, 1863 issue of the Union Vedette published by the officers and soldiers at Fort Douglas.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Apostle Orson Whitney claimed Lincoln illustrated his “let them alone” policy “by comparing the Mormon question to a knotty, green hemlock log on a newly cleared frontier farm. The log being too heavy to remove, too knotty to split, and too wet to burn, he proposed, like a wise farmer, to ‘plow around it.’”37 In a biography of President Young noted for its silence about the prophet’s many marriages, Preston Nibley, embellished the story, claiming Lincoln said:

Lincoln did not move to Illinois until after his twenty-second birthday, so Nibley clearly manufactured the quote. Leaving the Mormons alone won Lincoln the grudging respect of LDS leaders and the Great Emancipator’s obvious integrity won the deep affection of the people of Utah. Of all the presidents who had to contend with Brigham Young, Lincoln proved far and away the most able. He wanted to avoid yet another rebellion in the West, and he stationed a substantial military force in Salt Lake City to made sure the Mormons left him and the Union alone.39

The Second California Volunteers marched out of Stockton, California, on July 12, 1862, with orders to protect the overland mail route. After a September visit, Connor denounced Utah as “a community of traitors, murderers, fanatics and whores,” whose people “publicly rejoice at reverses to our arms, and thank God that the American Government is gone, as they term it, while their prophet and bishops preach treason from the pulpit.” Federal officers were “entirely powerless, and talk in whispers for fear of being overheard by Brigham’s spies.” Young ruled “with despotic sway, and death by assassination is the penalty of disobedience to his commands.” Colonel Connor declined to re-occupy the remote ruins of Fort Crittenden, now in the hands of speculators, and resolved to locate his headquarters on a bench overlooking Great Salt Lake City, where he could “say to the Saints of Utah, enough of your treason.”40

Chaplain John A. Anderson described the army’s entry into Great Salt Lake City. The “Chief of the Danites” allegedly offered to bet five hundred dollars that the California Volunteers would never cross the Jordan and rumor said the Mormons “would forcibly resist an attempt to cross that stream.” Colonel Connor was not easily bluffed; he reportedly swore he would “cross the river Jordan if hell yawned below him.”Yet his men, “from the highest to the lowest” intended “to treat the Mormons with courtesy and the strictest justice, so long as they remain friendly to the Government.” The soldiers crossed the river without incident but received a chilling reception as they marched to their new post overlooking the city. “Every crossing was occupied by spectators, and windows, doors and roofs had their gazers,” Anderson wrote. “Not a cheer or jeer greeted us.” 41 Brigham Young immediately beefed up the city’s police force, instructing them to watch suspicious persons “night and day until they learned what they were doing and who frequented their houses.” If any Mormon women visited the army’s camp, “no matter under what pretense, they should cast them forth from the Church forthwith.”42 Connor, a longtime supporter of the late Senator Stephen Douglas, named the army’s new post Camp Douglas after the Mormon ally-turned-foe.

Colonel Connor, Stenhouse reported, was “determined that the highway between the Atlantic and Pacific shall be kept open and free from murder while he is here in command, and he will stop at no considerations of opinion in attaining this end.”43 The soldiers and the Saints settled into a mutually suspicious but muted hostility, broken only by the odd collaboration that led to the virtual destruction of the Northern Shoshones early in 1863. Before dawn on a bitterly cold January 29, 1863, the California Volunteers attacked Boa Ogoi, the tribe’s winter camp on Bear River, near today’s Preston, Idaho. Shoshones had allegedly attacked and kidnapped travelers on the Oregon-California Trail, but the bands at Bear River had little to do with these raids. They had, however, resisted the settlers who began moving into Cache Valley in 1860 and appropriated their land and water during the next three years. “They rejected the way of life and salvation,” Bishop Peter Maughn told Brigham Young. The settlers wanted the tribe out of the way. Porter Rockwell led the soldiers north to the Shoshone camp. Before leaving Salt Lake, Connor announced he would take no prisoners. Frostbite crippled almost a third of the soldiers before they reached Brigham City, and the approach of the army was no secret to the Shoshones. Three of Bear Hunter’s men visited his father’s farm before the attack, William Hull recalled. Having seen the Toquashes, or soldiers, Hull warned them, “Maybe you will all be killed.” A warrior replied, “Maybe Touquasho be killed too.”44

The Shoshones had fortified the ten-foot bank of Beaver Creek, and when the freezing soldiers arrived, the warriors were ready for a fight. Oddly enough, Indian missionary Sylvanus Collett claimed he watched the fight “from a nearby eminence,” and an old pioneer, Hans Jesperson recalled visiting the battlefield with Lot Smith. The Deseret News reported the Shoshones sang out, “Fours right, fours left; come on you California sons of b—hs!” William Hull credited Bear Hunter with the taunt, adding, “We’re ready for you!” Connor reported the warriors “with fiendish malignity waved the scalps of white women and challenged the troops to battle.” The outraged volunteers launched a disastrous frontal assault before flanking the Shoshone position and cutting off their retreat. By 8:00 o’clock the warriors were out of ammunition and the soldiers shot down the survivors with their revolvers. What began as a battle degenerated into a massacre of women and children.45

Local Mormons hailed the atrocity “as an intervention of the Almighty,” but U.S. Army surgeon John Lauderdale thought otherwise. This “hardest fought battle was instigated without a doubt by the Mormons. The latter being unfriendly to our army thought they would betray us into the hands of the Indians. They thought by so doing they would make a little speculation out of it themselves. They made the Indians believe they could capture us most easily & agreed to reward them finely if successful.” The sequel of the story, Lauderdale wrote, “proved the destruction of the Indians.” 46 Lauderdale was right about the sequel, but he did not arrive in Utah until April 1864, so his conclusion was based on hearsay. His claim of collusion lacks corroboration, even though Connor did not hesitate to charge the Mormons with aiding and abetting Indian attacks on emigrants and soldiers.

The January 27, 1864 issue of the Daily Union Vedette.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Army reports of an upsurge in Indian violence during the spring of 1863 support Connor’s charge that Mormons “encouraged and instigated” repeated attacks on army patrols at Cedar Fork, Pleasant Grove, and Spanish Fork Canyon. The assault on Lieutenant Francis Honeyman’s advance party in the middle of Pleasant Grove was especially revealing,for as an officer’s report noted, it took place in front of “several hundred people calling themselves civilized and American citizens—God save the mark!” More than a hundred townspeople, “apparently well pleased at the prospect of six Gentiles (soldiers) being murdered,” helped some fifty Ute raiders steal government mules. Honeyman was convinced the attack “was a contrived and partnership arrangement between some of the Mormons to murder his little party, take the property, and divide the spoils.”47 According to E.B. Long, Connor’s officers “to a man, felt that the Mormons, instead of cooperating in punishing the Indians, encouraged them.”48

Federal Civil War Indian policy was nasty, brutish, and short—the army brutally suppressed Native resistance, concluded treaties with tribes that sued for peace, and quickly stopped violence on the overland road. If Ute leaders such as Antero, Tabby, Kanosh, and Black Hawk desired peace he “was there to grant it on proper terms,” Colonel Connor told them. The government “would protect all good Indians, and was equally determined and able to severely punish all bad ones.” 49 Connor’s toughness, Long concluded, “combined with a degree of flexibility when pragmatism dictated it, his willingness to work for peace with both the Indians and the Mormons, in the long run worked. Connor had a job to do, was determined to do it as he saw it, and in the main he was a credit to the leadership of the United States in the crisis years of the Civil War.”50

Mrs. Selden Irwin performed at the Fort Douglas Theater in 1864.

Camp Douglas expanded the contest for the hearts and minds of Utah, and it made significant contributions to territorial culture. Its soldiers created the Union Vedette in November 1863, which became Utah’s first daily newspaper in January 1864. As its name indicated, the paper proposed to act as a mounted sentinel to expose those “bold, bad men” who sought to mislead the mass of Utah’s people, “who we know to be honest and sincere, though mistaken.” These devoted Unionists expressed their intense loyalty to “the freest, greatest, and most paternal Government on earth” and proclaimed it had “no enemies to punish; no prejudices to indulge; no private griefs to ventilate.” The editors promised to expose “the appeals of ambitious, crafty, designing men, to wean the people from the Government, that their own ends may be subserved—who constantly vilify and abuse the officers of the best Government with which this or any other people were ever blessed.” The soldiers wanted peace with the Mormons, but “toleration for disloyal sneers is no part of the duty of a true citizen.” Its first issue promoted opening “the rich veins of gold, silver, copper, and other minerals” to attract “a new, hardy and industrious population” to the only place in the West where a prospector could find himself “cast forth.”51

The first editor, Captain Charles H. Hempstead, tried to maintain a moderate tone until “pressing duties” led him to resign in December 1864, but “the continued and persistent disloyal utterances in Tabaernacle [sic] sermons” outraged his successors.52 A constant complaint was the contempt Mormon leaders displayed for President Lincoln and the federal government. “To aid the right, oppose the wrong,” The Vedette was unapologetically “bold, sarcastic, and obviously partisan, but no more so than most papers of its day.”53 The newspaper gave voice to the eloquent dissent of disillusioned Latter-Day Saints, reprinting a Scot convert’s description of life in Zion from a March 1864 Dundee Advertiser and publishing forty-five installments of a report by a “Resident of Utah” between March and October 1865.54 The Vedette’s alternate voice and the army’s presence provided a counterweight to Mormon power in Utah Territory.

Meanwhile, Utah’s war economy boomed and Brigham Young’s attempt to control prices floundered. After years of grinding poverty, mining discoveries in Idaho and Montana, a resulting surge in overland freighting, and the demands of Camp Douglas for grain, groceries, produce, beef, lumber, firewood, and entertainment introduced Latter-day Saints to the blessings of a free market. “More than one merchant of this city boasts of having made from $160,000 to $300,000 the past season, clear profit,” the New York Times reported in 1865. “A merchant that can’t make a fortune in a twelvemonth is ‘nowhere.’”55

President Young moderated his public rhetoric about the evils of Republican government as the Civil War wound down, but he never ceased to complain about “the strong arm of military power” Connor commanded in Utah. He denounced the army post as “an uncalled for, utterly useless, extravagant, and non-sensical operation.”56 As 1865 began, he said, “If Gen Connor crosses my path I will kill him so help me God. He must keep out of my path. He may say what he pleases about me and I will what I please about him.” Young threatened Connor with Governor Dawson’s fate, saying the Lord would be pleased if the Saints “cut him” and sent his soldiers back to California. Connor wanted “to kill the Saints, take our grain and destroy our Daughters and this I will not permit him to do,” Young told the State of Deseret’s legislators.57

Despite such prophetic fulminations, Union support grew in Utah as the Civil War came to its bloody end. Even Mormonism’s highest leaders seemed to join in a spirit of reconciliation on March 4. Wilford Woodruff described the “great Celebration in the City on this day of all the Military & Civil authorities on the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln to the presidential Chair & the late victories.” A very imposing mile-long procession marched through the “streets, broad and straight, of the Mormon Capital,” whose sidewalks, windows, house-tops were “thronged by eager, and in some instances, enthusiastic lookers-on.” Thousands of “Citizens Joined them in the Celebration,” along with the faith’s apostles, generals, and politicians, until the “vast concourse dispersed amid rousing cheers and salvos of artillery.” Apostle George A. Smith “waved the US Flag & said ‘One Country, A united Country An undivid[ed] Country & the old Flag Forever.’” The “citizen cavalry of Great Salt Lake City” escorted the soldiers back to Camp Douglas, and then the officers “were invited to partake of an elegant repast, provided by the City Council at the City Hall.” A new “era of toasts, speeches and good things generally seemed to have arrived. Mayor Smoot opened the ball by proposing the health of President Lincoln and success to the armies of the Union.” Mormon officials, businessmen, and four apostles joined in a “free, easy, hospitable and a most kindly interchange of loyal sentiment among gentlemen not wont often to meet over the convivial board.”58 Woodruff cast the celebration in a darker light: “Speeches weremade & tosts were drank. All this was for policy.”59

The Fort Douglas Military Band taken about 1865.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Woodruff’s “policy” comment raises questions about the sincerity of Mormon leaders, their interest in reconciliation with the diverse elements of Utah’s increasingly complex polity, and their proclamations of loyalty to the Constitution while happily predicting the demise of any government but their own. President Lincoln’s wise Utah policy and the economic benefits Camp Douglas brought to the territory began to win the hearts of the people. A repentant Thomas Stenhouse characterized General Connor and the California Volunteers as “a terror to evil-doers” and acknowledged that “neither the commander nor his officers had any feeling but sympathy” for the Mormon people, who were loyal to the Republic; leaders were only the disloyal. Brigham Young’s persistent claims of government persecution and abuse did “incalculable mischief to the Saints,” Stenhouse concluded. “It has robbed them of the natural loyalty of good citizens, and led them to curse the Government which protects them, and to pray for the overthrow and destruction of the nation.” The conflict between church and state, Stenhouse observed, revealed that “Theocracy and Republicanism were naturally antagonistic” and neither would yield to the other. Faithful Mormons were “enlisted on the side of ‘the Kingdom,’” but to the territory’s federal officers, “the Republic is everything, Brigham and his ‘kingdom’ are but an ‘ism.’”60

The tradesmen and working-people parading through the streets, cheering “the patriotic, loyal sentiments” expressed in the speeches, moved General Connor. “He wanted differences to be forgotten,” and he extended his hand to Thomas Stenhouse, editor of the Ogden Telegraph . Connor “expressed the joy he experienced in witnessing the loyalty of the masses of the people” and his hope for peace. The newspapers “had waged a fierce warfare, but as an evidence of good faith,” Connor proposed to stop publication of the Vedette immediately.61

As late as 1865 Mormon leaders believed the Civil War was only in its initial stages. On March 6, Daniel H. Wells of the First Presidency said Lincoln “would be in the presidential Chair untill He had destroyed the Nation. The North will never have power to Crush the South No never. The Lord will give the South power to fight the North untill they will destroy Each other.” 62 About the time Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, Brigham Young uttered his least celebrated prophecy to the semi-annual conference on April 9, 1865. “On the very day that the telegraph announces the downfall of rebellion in the destruction of the last army it could boast,” the Union Vedette reported, “this infallible seer raised the curtain of the future and to have ‘the war continue four years longer.’” The Deseret News limited its coverage of the sermon to “a few remarks upon sending missionaries to preach the gospel,” and comments on local grog shops, gambling dens, and “the present lamentable and mournful condition of our country.” The Vedette wondered if “the public has been made the victim of a grave hoax—that Lee has not surrendered, after all.”63

At the end of his service in Utah, General Connor concluded the secret power of Mormonism’s leaders “lies in this one word—isolation.”64 Word of President Lincoln’s assassination arrived in Utah on the morning he died and Salt Lake City businesses closed immediately. Many decorated their homes with emblems of mourning, and black borders framed the front pages of both the Union Vedette and Deseret News. The Salt Lake Theatre closed. “The citizens have done themselves lasting honor on this sad occasion, and we acknowledge the display of deep feeling on their part with the gratitude it deserves,” the Vedette acknowledged. The flags on Brigham Young’s residence and other houses flew at half-staff, and “the Mormon president’s carriage went through the town covered with crepe.” It was good policy, but Young declined to join the public events that celebrated Lincoln’s victory and all-too-soon mourned the martyred hero. The sorrow of the Mormon people contradicted the prophet’s long expressed contempt, ridiculing the president as “Abel Lincoln” and suspecting that Old Abe had plotted “to pitch into us when he has got though with the South.”65

On Sunday, April 19, the pulpit of the Tabernacle was draped in black. “This is the day Set apart by the Nation for the funeral Seremonies of Abram Lincoln in all the States & Territories,” wrote Wilford Woodruff, who delivered the benediction. “A Large Assembly met at the Tabernacle at 12 oclock of all Classes Civil & Military Jew & Gentile.” An immense concourse filled the building “to its utmost capacity, religious differences for the time ignored, and soldiers and civilians all uniting as fellow citizens in common observance of the solemn occasion,” the Vedette reported, praising the tone and sentiment of Amasa Lyman’s eulogy, which was “marked by much ability, feeling and fitness for the occasion.”66 Utah’s heartfelt reaction to a national tragedy was a quiet rebuke to Brigham Young’s contempt for the government and a landmark in the transformation of the territory from a religious theocracy to an American state.

The beloved president’s death and the end of the war that had torn a nation apart marked a sea change in American history. The Civil War saw the “triumph of nationalism over states’ rights,” as the war “created a national currency, a national banking system, a national army and new national taxes. The jealous restrictions against the power of the central government were broken in a score of ways,” wrote Mark Cannon.67 Congress exercised full sovereignty over the territories, granted homesteads, endowed agricultural colleges, and underwrote a Pacific railroad with massive land grants and bonds. With the abolition of slavery and the creation of a strong central government, the reunited United States resolved to make citizens of every faith obey American laws, including Justin Morrill’s 1862 “Act to punish and prevent the Practice of Polygamy in the Territories of the United States.” The long struggle to quell Mormon theocracy and “the second relic of barbarism,” Mormon polygamy, and the Latter-day Saints’ long campaign of religious and civil disobedience, now began.

NOTES

Will Bagley is an independent historian. With David Bigler, he is the author of The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, which won best book awards from the John Whitmer Historical Society and Western Writers of America, Salt Lake City Weekly’s Reader’s Award for Best Non-Fiction Book of 2011, and Utah State History’s Best Militar y History Award.

1 William McLachlan, Reminiscences, September 25. 1863, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1:115–39.

2 Elijah Larkin, Diary, September 25, 1863. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, MSS 175.

3 E. L. Sloan, Journal History, September 25, 1863, LDS Church History Library, 2–3.

4 Richard Van Wagoner, ed., Complete Discourses of Brigham Young 5 volumes, (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2009), October 9, 1863, 4:2162.

5 See U.S. Supreme Court, Miller v. U. S., 78 U.S. 268 (1870), which upheld the government’s “right to confiscate the property of public enemies wherever found.”

6 McLachlan, Journal, September 23, 24 1863, LDS Church History Library.

7 William Richardson, Autobiography, 18-20, LDS Church History Library.

8 Abraham Lincoln, “The Gettysburg Address,” November 19, 1863.

9 Liberal, “Letter From Salt Lake,” Sacramento Union, December 23, 1862; Enfield, “Letter From Salt Lake,” Sacramento Daily Union, March 27, 1863. “Reflections,” Union Vedette, August 10, 1864, identified Stenhouse as “Liberal.”

10 Doctrine and Covenants, Section 87:1–8.

11 Franklin D. Daines, “Separatism in Utah,” Annual Report , 1917 (Washington, D.C.: American Historical Association), 341–43.

12 Brigham D. Madsen, Glory Hunter: A Biography of Patrick Edward Connor (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 66–67.

13 E. B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 18, 271. University of Wyoming professor Everette Beach Long died at age sixty-one the year his masterfulvolume on Utah and the Civil War appeared.

14 Brigham Young Office Journal, December 28, 1860, March 15, 18, August 24, 1861, in Van Wagoner, ed., The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, 3:1720

15 Young, “Remarks,” August 31, 1862 and November 6, 1863, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-Day Saints Book Depot, 1854-1886), 10:367, 10:287-88.

16 “Synopsis of Instructions,” June 22–29, 1864, Journal of Discourses, 10:333.

17 “Completion of the Telegraph,” Deseret News, October 23, 1861, 5/3; Van Wagoner, ed., The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, December 28, 1860, March 15, 18, August 24, 1861, 3:1720, 1741; 4:1982, 1906.

18 Journal History, December 10, 1861, LDS Church History Library, cited in Long, The Saints and the Union, 50. Long thought this “was perhaps Brigham Young’s strongest known anti-Lincoln statement during the presidency.”

19 Anonymous, Minutes of the Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1835-1893 (Salt Lake City: Privately Published, 2010), August 23, 1863, 318.

20 David L. Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom: The Mormon Theocracy in the American West (Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1998), 199.

21 Riders carried the election results to the telegraph at Fort Churchill in today’s Nevada. Papers in Sacramento and San Francisco published them on November 14, 1860.

22 Orson Whitney, History of Utah 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Cannon and Sons Co., 1893), 2:30.

23 John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 318

24 Whitney, History of Utah, 2:43; Young to Bernhisel, April 25, 1862, Brigham Young Collection, LDS Church History Library.

25 Deseret News, April 30, 1862. Acting on Brigham Young’s suggestion, acting governor Frank Fuller called up Burton’s company. A few days later, the Secretary of War asked Young to provide Smith’s company.

26 The classic study is C. LeRoy Anderson, Joseph Morris and the Saga of the Morrisites (Logan: Utah State University Press, enlarged edition, 2010). For an insightful perspective, see Val Holley, “Slouching Towards Slaterville: Joseph Morris’s Wide Swath in Weber County,” Utah Historical Quarterly 76 (Summer 2008), 247–64.

27 Long, The Saints and the Union, 87–88.

28 Mark Twain, Roughing It (Hartford: American Publishing Company, 1872), 105.

29 Brigham Young Office Journal, December 25, 1861, in Turner, Brigham Young, 312.

30 Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom, 201–02; Scott Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, December 23, 1861, 10 vols. (Midvale: Signature Books, 1983), 5:609. Dawson was “a victim of misplaced confidence, and fell into a snare laid for his feet by some of his own brother-officials.” Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1873), 592.

31 “Departure of the Governor,” January 1, 1862, “Governor Dawson’s Statement,” January 22, 1862, both Deseret News

32 Cannon to Young, January 29, 1874, Brigham Young Collection.

33 Kenney, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, June 12, 1863, 6:115; War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 50, Part II, Serial 3584, 500. On January 12, 1864, a firing squad shot Jason Luce, the last known participant in Dawson’s assault, for the murder Samuel Burton. See Bigler, Forgotten Kingdom, 204n11

34 Van Wagoner, ed., The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, October 30, 1862, 4:1945.

35 Stenhouse to Young, June 7, 1863, Brigham Young Collection. Similarly, Lincoln told John Bernhisel he remembered less about Dawson “than any important appointment that I have made.” Long, The Saints and the Union, 60.

36 Allen Rice, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln ( New York: North American Publishing Company, 1886), 399–400.

37 Orson Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons Co., Publishers, 1893), 2:24–25.

38 Preston Nibley, Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1937), 369.

39 Long, The Saints and the Union, 26, 36, 168, 271.

40 War of the Rebellion, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1900) Vol. 50, Part 2, 119-20, cited in Long, The Saints and the Union, 101.

41 Long, The Saints and the Union, 111-12.

42 Journal History, October 26, 1862, cited in Long, The Saints and the Union, 112.

43 Liberal, Sacramento Daily Union, February 7, 1863.

44 William Hull, “Identifying the Indians of Cache Valley, Utah and Franklin County, Idaho,” Franklin County Citizen, January 25, 1928, cited in Madsen, The Shoshone Frontier, 182.

45 Deseret News, February 11, 1863. Rod Miller, Massacre at Bear River: First, Worst, Forgotten (Caldwell, ID: Caxton Press, 2008), 100-101 and 155-56.

46 Lauderdale to Dear Frank, June 15, 1864, Lauderdale Papers, Beinecke Library,Yale University.

47 War of the Rebellion,Vol. 50, Part 2, 205-206, cited in Long, The Saints and the Union, 176.

48 Long, The Saints and the Union, 177.

49 Connor to Drum, July 18, 1863, War of the Rebellion,Vol. 50, Part 2, 528.

50 Long, The Saints and the Union, 270–71.

51 “Salutatory” and “Ourselves,” Union Vedette, November 20, 1863. For more, see Lyman C. Pedersen, Jr., “The Daily Union Vedette: A Military Voice on the Mormon Frontier,” Utah Historical Quarterly 42, (Winter 1974), 39–48.

52 “Plainer Than Usual,” Union Vedette, January 7, 1865.

53 Long, The Saints and the Union, 208–09.

54 “Mormonism as Seen by a Scotchman,” Union Vedette, May 5, 1864; “An Address to the People, by a Resident of Utah,” March 16, 1865 to October 10, 1865, all Daily Union Vedette.

55 “Affairs in Utah,” New York Times, April 23, 1865.

56 Brigham Young Letter Books, LDS Church History Library, cited in Long, The Saints and the Union, 113–14.

57 Van Wagoner, Complete Discourses, January 23, 1865, 4:2261; Turner, Brigham Young, 329.

58 “The Inaugural Celebration” and “Reunion at the City Hall,” Union Vedette, March 6, 1865.

59 Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:215–16.

60 Stenhouse, The Rocky Mountain Saints, 248, 606, 683.

61 Ibid., 611–12.

62 Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, March 6, 1865, 6:216.

63 “Minutes,” Deseret Weekly News, April 12, 1865; “The Doctors Disagree,” Union Vedette, April 12, 1865.

64 Connor to Dodge, April 6, 1865, The War of the Rebellion, Series 1,Vol. 50, Part II, Serial 3584, 1185.

65 Brigham Young Office Journal, quoted in Long, The Saints and the Union , 36. See also 26 and 261–62

66 Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, April 19, 1861, 221; “Funeral Ceremonies at the Tabernacle,” Union Vedette, April 21, 1865.

67 Mark W. Cannon, “The Crusades Against the Masons, Catholics and Mormons: Waves of a Common Current,” BYU Studies 3 (Winter 1961), 39.