42 minute read

Utah’s Civil War(s): Linkages and Connections

Utah’s Civil War(s): Linkages and Connections

BY WILLIAM P. MACKINNON

“Could my voice be as effectually heard in the strife now surrounding you, as was yours in the troubles that seemed to overshadow us in 1857-8.” — Brigham Young to Thomas L. Kane, September 21, 1861

“You need not expect anything [from Utah] for the present. Things are not right.” — Utah Gov. Stephen S. Harding to Brig. Gen. James Craig, August 25, 1862

As the nation commemorates the American Civil War’s one-hundred-fiftieth anniversary, there is a need to remember Utah’s uniquely limited role in that conflict, especially the highly unusual linkages and connections that shaped it, and the reasons why the territory’s involvement unfolded as it did. It is a rich, exotic context that needs to be understood rather than a background to be overshadowed by our understandable, national fascination with the more dramatic stories of slavery and large-scale battles fought east of the Mississippi. This article’s intent is to shed light on Utah’s unusual Civil War role through a better understanding of a territorial-federal conflict that immediately preceded and shaped it, the Utah War of 1857-1858. It is not an easy connection to describe, for, as historian Michael Beschloss has observed, it is challenging “to dramatize a nonevent. Telling a tale that unfolds [invisibly] in conflicts behind Washington’s closed doors is more difficult than recounting the boom and bang of battlefields.”1

General Irwin McDowell.

CIVIL WAR ACADEMY

To what extent and how did Utah Territory participate in the American Civil War? 2 Our story begins with the “what” of the matter and then proceeds to the “why” question.

If one skips from the April 1861 start of the Civil War to the third week of October, it is apparent that the six-month-old conflict was going badly for the Union side. On October 21, for example, President Lincoln learned of the Union Army’s disastrous defeat at Ball’s Bluff,Virginia. That same day the president’s bodyguard, Ward H. Lamon, and Illinois congressman Elihu B. Washburne, wrote privately from St. Louis to describe in apocalyptical tones the leadership shortcomings of the army’s department commander in Missouri, General John C. Frémont, the flamboyant, erratic adventurer who had run for the presidency in 1856 on a Republican Party platform that linked and urged the eradication of polygamy and slavery as “the twin relics of barbarism.” Also on October 21, 1861, former president James Buchanan a prime mover in the Utah War—wrote from his Pennsylvania retirement mansion a shockingly inane note asking a beleaguered Lincoln to forward a borrowed book that he had inadvertently left behind in the White House library seven months earlier. Almost as an afterthought, Buchanan closed his only known note to Lincoln during the Civil War with the breezy comment: “Sincerely desiring that your administration may prove successful in restoring the union & that you may be more happy in your exalted Station than was your immediate predecessor.”

On October 22, 1861, the next day, the flow of mail to the White House with strange LDS linkages continued apace, especially from New York. James Gordon Bennett, editor-publisher of the New York Herald and a former brigadier general in the Mormon Nauvoo Legion, wrote to support Lincoln and the Union in language as vigorous as President Buchanan’s comments were insipid. The same day, James Arlington Bennet, a Brooklyn cemetery developer whom Joseph Smith, Jr. had earlier designated a Nauvoo Legion major general as well as his 1844 presidential running-mate, also wrote to Lincoln. His was a stunning, unsolicited proposition: “Will your Excellency accept from one to ten thousand Mormons to be mustered into the service of the U. States, to fight for our glorious Union & Constitution?” This Bennet, not to be confused with his brother-officer the Manhattan newspaperman, signed the letter with his former Nauvoo Legion rank and the self-description, “full of life fun & fight.”3

James Arlington Bennett’s unsolicited profferof thousands of Mormon troops for the Union Army would, on the surface, seem to have been a god-send for Abraham Lincoln—the prospect of the Mexican War’s Mormon Battalion but on a grander scale. The president’s initial call for the states to provide seventy-five thousand men had been met during the summer, but their three-month enlistments were expiring, and, after dramatic Union defeats at Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff, governors were challenged to provide fresh, longer-serving regiments for the duration of the war. The president was in need of, if not desperate for, troops. What did Lincoln do with James Arlington Bennet’s offer? Nothing. He filed it without response, much as the army’s adjutant general had literally pigeon-holed former captain U.S. Grant’s unsolicited offer to re-enter the army a few months earlier.

T.B.H. Stenhouse.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The reason for Lincoln’s decision to ignore this proposition is murky. Perhaps from his highly-developed political instincts, the president realized that James Arlington Bennet’s vision of brigades of Latter-day Saints was a non-credible pipe dream spawned in the isolation of Brooklyn from the rich fantasy life of an erratic, aging former Mormon insider-outsider. Then there was the matter of background. Bennet was not only the author of

accounting and mathematics texts but a small-time confidence man who had spent part of the 1850s imprisoned in Manhattan’s notorious Tombs. Although Brigham Young had baptized James Arlington Bennet in the surf of Long Island Sound in the early 1840s, Bennet had written to Lincoln in 1861 without consulting Young or anyone else in Utah Territory, home of the thousands of troops he envisioned to fight for the Union. As a cemetery promoter, Bennet might have been able to provide the free burial plot and 300-foot obelisk that he had quirkily tendered to President Buchanan as the Utah War started in the spring of 1857, but four years later he was wholly incapable of delivering the large religiously-based military force that he held out to Lincoln.4

If President Lincoln chose to distance himself from James Arlington Bennet’s byzantine recruiting scheme, he was equally wary of seeking largescale troop commitments directly from Utah Territory’s official and informal leaders. So also were they. A month before Bennet wrote to Lincoln, Brigham Young had written to his oldest non-Mormon friend, Thomas L. Kane of Philadelphia, who had just entered the Union Army as a lieutenant colonel after recruiting a regiment of Pennsylvania lumberjacks: “A word to you, my Friend, your present position and calling will bring no credit to you, nor to any other man. They are afraid of you, and will not give you your just dues. They will find out in time that the strife they are engaged in will bring no desirable celebrity. This is for your own eye and benefit [only].” 5 Accordingly, although there was a significant amount of military activity in and around Utah during 1861-1865, the territory, its civil-religious leaders, and its military-age men played virtually no part in the action.6

Thomas L. Kane

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

There was, of course, a notable exception to this generalization—the now-famous ninety-day service of Captain Lot Smith’s one hundred-man federal cavalry company raised in Utah with Brigham Young’s help during the spring of 1862. But that was it. When during August 1862 Brigadier General James Craig, the Union Army’s short-handed commander at Fort Laramie, sought to re-enlist Lot Smith’s troops and recruit even more extensively in the territory, Utah governor Stephen S. Harding waved him off. Harding, a Lincoln appointee, had just met with former governor Brigham Young, with the result his cryptic telegraphic report to General Craig: “You need not expect anything [from Utah] for the present. Things are not right.”7 Consequently, Craig and the Lincoln administration backed off for the balance of the war and recruited troops elsewhere – three hundred thousand of them in the next few months alone. In the fall of 1864 the army’s commander in San Francisco made one more attempt to explore the possibility of raising a regiment of volunteers in Utah, but the effort proved ineffective. Hence T.B.H. Stenhouse’s now-famous 1863 report to former governor Young that the president had described to him a Lincolnesque Mormon policy by which “if the people let him alone, he would let them alone.”8

This is not to say that individual Latter-day Saints living in the Middle West or South, rather than Utah, did not join the Union and Confederate armies. In fact, they did so. But their numbers were very small—only a handful have been identified by name—and their enlistment decisions were influenced by personal inclinations or local pressures rather than by any call to arms by Utah Territory’s distant official or informal leaders.9

And so from August of 1862 the responsibility for protecting Utahns as well as the transcontinental emigration trails and telegraph line through their territory fell to volunteer regiments raised not in Salt Lake City but in California and elsewhere. As Brigham Young so frequently phrased it in other contexts, “the job was let out.”

Compared to the participation, if not carnage, experienced by virtually every other state and territory, Utah’s absence from the fray was unparalleled and had long-lasting negative impact on attitudes about her patriotism throughout the United States. 10 If Utah’s men were not battlefield casualties, their territory’s reputation surely was, especially among Union and even Confederate veterans unaware of service by Lot Smith’s company and Abraham Lincoln’s ambivalence about a subsequent call on Utah Territory for military manpower.

Put most starkly, Union men from each of the eleven states of the Confederacy formed and provided more companies, battalions, and regiments to the United States Army than did Utah. Perhaps even more dramatic was the fact that at the end of the war Camp Douglas was garrisoned by at least one federal regiment recruited from Confederate prisoners of war who had been paroled with the condition that they enlist in the Union Army to fight Indians as “Galvanized Yankees.”11

So why would President Lincoln have to rely more on federal units with names like the First Alabama Cavalry and the First Georgia Infantry— regiments that joined General Sherman in his brutal march from Atlanta to the sea—rather than on, say, a Second Regiment of Utah Cavalry that was never recruited? The short answer is that because Utah Territory, under Brigham Young’s unofficial leadership, had, in effect, opted out of the Civil War with Lincoln’s acquiescence. Beyond his key, early role in raising Lot Smith’s single company of three-months men, President Young was unwilling for Utah to contribute further to the war effort. He had two main reasons for this decision—the first religiously oriented and the other emotional.

General James Craig.

PUBLIC DOMAIN

With respect to religion, Young felt that the American Civil War was simply not a Mormon conflict. When the war started Utah was technically a slave territory, but there were so few people living in bondage within its borders that defense of the Confederacy and its peculiar institution held no appeal for Mormons. By the same token, anti-black attitudes (President Young’s among them) muted any abolitionist fervor in Utah of the sort that had developed in many of the northern states to bring on the war itself while fueling the fires of strong pro-Union sentiments. Consequently Brigham Young saw the war in millennial or religious terms rather than through the lens of political or sectional allegiances. As one of Young’s senior apostles, John Taylor, put it on Independence Day of 1861, “Shall we join the North to fight against the South? No! … Why? They have both, as before shown, brought it upon themselves, and we have had no hand in the matter … we know no North, no South, no East, no West; we abide strictly and positively by the Constitution.”12

Since Joseph Smith’s 1832 prophecy that there would be a great American civil conflict and that it would begin in South Carolina, Mormons and their supreme leader had not only anticipated such a turn of events but viewed it as God-given retribution or punishment for Mormon persecution.13 They saw the Mormon role as one to be played out only at the war’s end. By this view, Mormons, with Lamanite allies at their side, were destined to save an exhausted country and its imperiled constitution by intervening to establish the Kingdom of God in anticipation of the end days and imminent Second Coming of Christ. Perhaps this is what Brigham Young meant in writing to Thomas L. Kane in September 1861 to comment on “disastrous results” and to say cryptically, “all this is but the beginning of still greater events, events which it may not be wise to too freely express one’s views upon.”14

In some respects Young’s religious views of the war closely resembled those of many other American religious leaders. In still other ways his interpretation of the Civil War was uniquely Mormon, leading President Young to counsel as he did a complete withdrawal from involvement in the conflict.

The similarities among Protestants, Catholics, Mormons, and Jews ran to their religious leaders’ view of what historian George C. Rable has called a “providential” (divinely involved) interpretation of the Civil War—one with millennial overtones:

In Brigham Young’s view, the national sin for which the Civil War was divinely engineered and deservedly calamitous, was godlessness aggravated by persecution of the Latter-day Saints and assassination of their founding prophet, abandoned to his fate by a feckless U.S. government. If before the Civil War Abraham Lincoln had worried about what he termed a House Divided, Brigham Young was more than willing, once the fighting began, to proclaim a plague on both its conflicted wings while awaiting societal collapse on a continental scale. From this ruin Mormonism was expected to arise triumphant. Given this interpretation of the war’s origins and meaning by the most influential religious leader in the territory, it is not surprising that Utahns abstained from rushing into such a scene.16

Aside from matters of religion, the second major factor driving Brigham Young’s antipathy toward Utah’s participation in the Civil War was an emotional one—anger and resentment toward the U.S. government, especially with respect to its involvement in the recently concluded Utah War of 1857-1858 and the federal military “occupation” of the territory that followed until the outbreak of the Civil War itself.

Take the matter of gunpowder, for example. All during the Utah War Young had tried without significant success to stimulate the local manufacture of this military necessity. As the Utah Expedition closed down Camp Floyd in 1861, to Young’s rage it blew up its ammunition magazines, prompting him to storm: “Was this course conciliatory and wise? Such destruction appears the more singular … when contrasted with the possibility that the Government may wish our armed assistance in some shape, at some time, for which those arms and munitions would be very requisite, and the destruction of which has placed a call for aid in such an awkward position to be made, should they at any time desire to make it. Where is the counsel of the prudent?”17

In 1861 Brigham Young had wistfully written to Kane: “Could my voice be as effectually heard in the strife now surrounding you, as was yours in the troubles that seemed to overshadow us in 1857-8, I would most cheerfully endeavor to reciprocate the noble deeds of yourself. But the roar of cannon and the clash of arms drown the still small voice of prudent counsel.”18 By 1862 it was too late; anti-federal attitudes rooted in the devastating Utah War experience and aggravated by both Congress’s rejection of another statehood petition for “Deseret” as well as Lincoln’s signature on the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, the first federal anti-polygamy statute, had solidified Brigham Young’s negative view of the Civil War. That year Young said:

Reinforcing Brigham Young’s hostility to the war effort was Lincoln’s unannounced insertion into Utah of Colonel Patrick Edward Connor’s regiment of California volunteers. Through his own intelligence sources, Young knew that Connor’s troops were coming weeks ahead of their arrival in Salt Lake City on October 26, 1862. As with the westward movement of the Utah Expedition five years earlier, Young had received no formal notification from the United States Government. As early as August 25, 1862, the day that Utah’s Governor Harding met unsuccessfully with Young to discuss General Craig’s desire to re-enlist Lot Smith’s cavalry company, President Young had sent the army’s adjutant general in Washington a telegram freighted with both ambivalence and sarcasm: “Please inform me whether the government wishes the militia of the Territory of Utah to go beyond her borders while troops are here from other States who have been sent to protect the mail and telegraphy property.”20 With this message Young signaled not only his annoyance over the unannounced troop movements then under way but his unwillingness to again use his influence to send Mormon troops into action outside Utah’s borders.

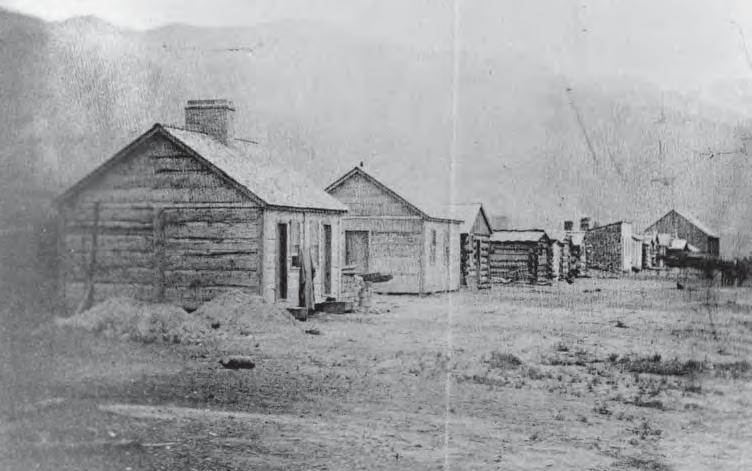

A view of Fort Douglas in 1868 looking from the northeast to the southwest.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Compounding the indignity of having Utah “occupied” by “foreign” troops while the U.S. government exerted pressure to recruit Mormon lads for service elsewhere, was Connor’s decision to name his bivouac on the bench overlooking Salt Lake City “Camp Douglas.” Connor’s selection of the late Senator Stephen A. Douglas as namesake for his new post was a deliberate thumb in Young’s eye. Given the well-known Mormon hostility to Douglas since his controversial, anti-Mormon speech given in Springfield, Illinois at the beginning of the Utah War, it is difficult to view Connor’s motives otherwise.21

Chaffing under the presence of Connor’s troops in Utah, in March 1863 Brigham Young’s anger boiled over. He publicly lashed out in a Sunday discourse to say, “[I]f the Government of the United States should now ask for a battalion of men to fight in the present battle-fields of the nation, while there is a camp of soldiers from abroad located within the corporate limits of this city, I would not ask one man to go; I would see them in hell first.”22 Connor’s Californians were in Utah, rather than battlefields in the East, because of President Young’s unwillingness to countenance local recruitment after the spring of 1862 and his opposition to raising regiments in Utah because of the war department’s decision to send Connor’s troops to Salt Lake City. Compounding this complexity was President Lincoln’s apparent unwillingness to call on Utah’s federally-appointed governor for a levy of troops as he had done throughout the rest of the country.

Nonetheless, in October 1864 Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, commander of the army’s Department of the Pacific, doggedly queried Utah governor James Duane Doty, a non-Mormon on good terms with Brigham Young, about the possibility of raising a four-company regiment of Utah infantry for the Union Army. Doty never quite said “no” in response to this overture, but he pointed out that Utahns already had the opportunity to join the Union Army by enlisting in Connor’s existing regiment. Doty also noted the inferiority of military pay versus wages for mining and agricultural work in Utah, the absence of an attractive enlistment bounty for Utahns of the sort available elsewhere, and the ineffectivenessof using infantry rather than cavalry in the region. McDowell, exiled to San Francisco following his disastrous 1861 defeat at First Bull Run, was in no mood to quibble with a clearly unenthusiastic territorial governor. After informing Governor Duty, “I do not propose to make requisition for cavalry instead of infantry,” General McDowell let the matter drop.23

Adding to this antipathy were Brigham Young’s strong reservations about, if not contempt for, President Lincoln, a man whom he had never met notwithstanding their common residence in Illinois. After Lincoln’s assassination and near-canonization, public criticism of the martyred president was carefully muted in Utah as elsewhere, but before that catastrophe, local comments about Lincoln were frequently caustic. Even before Lincoln’s first inauguration, Brigham Young referred to him publicly as a weakling “King Abraham” much as he continued to dub Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchanan, “King James.” Throughout the war Brigham Young was often scathing in his private comments about Lincoln as were some of the president’s own cabinet officers. 24 On August 23, 1863, a month after the fall of Vicksburg and the great battle at Gettysburg, Young referred to the president during a small council meeting at apostle Ezra T. Benson’s home as “old Abe Lincoln” and added, “Now you may excuse me or not, but he is a damned old scamp and villain, and I don’t believe that Phoraoh [sic] of old was any worse or wickeder.” 25 Unlike Brigham Young’s comments about General Connor, which were deeply personal, his negative remarks about Abraham Lincoln, as with those about James Buchanan before him, seem institutional more than personal.

With this background as to the “what” of Utah’s limited role in the Civil War, it is now appropriate to return to the “why” question and the linkage between that conflict and the Utah War that immediately preceded it. The 1857-1858 conflict was the single biggest factor in shaping Utah’s unique reaction to the Civil War when it began three years later.26

Lodging for non-commissioned soldiers and laundress quarters at Fort Douglas.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

In brief, the Utah War was a struggle for power and authority in Utah— ten years in the making—between the territory’s civil-religious leadership headed by Governor Brigham Young and the federal administration of President James Buchanan. At stake were competing philosophies of governance for Utah—its continuation as a de facto religious theocracy under Young’s authoritarian leadership or a territory ruled by republican principles under congressional supervision. This armed confrontation was the nation’s most extensive and expensive military undertaking during the period between the Mexican and Civil wars—one that eventually pitted Utah’s large, experienced territorial militia (Nauvoo Legion) against almost one-third of the United States Army.

During the war atrocities were committed by both sides on a scale that rivaled the carnage that had earned Utah’s eastern neighbor the enduring label “Bleeding Kansas.” Among the casualties was Brigham Young’s own reputation, damaged by federal grand jury indictments for treason and murder and stained, along with that of the church he led, by controversy over responsibility for the appalling Mountain Meadows Massacre of September 11, 1857. What followed during the three-year period between the U.S. Army’s entrance into the Salt Lake Valley in June 1858 and its 1861 departure for the battlefields of New Mexico and Virginia, was an ordeal that Mormons later likened to Reconstruction in the South during 1865-1876.

Upon the army’s arrival in Utah, private citizen Young went into seclusion, fearing for his life and curtailing church services in the Salt Lake City Tabernacle throughout the summer of 1858. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Mormon families from northern Utah trekked home and struggled to reestablish themselves after their epic, disruptive Move South to Provo during the spring of 1858. Theirs had been the largest mass movement of refugees since the expulsion of the Acadians from Nova Scotia and the British Loyalists from the United States following the French and Indian War and American Revolution, respectively. With the subsequent influx of troops, camp followers, merchants, miners, and opportunists the ratio of Utah’s Mormon to non-Mormon population changed forever. Destroyed with this change was the cultural, family, and religious isolation that had enabled Utah to become what it was when the Utah Expedition first arrived. Adding insult to injury, in March 1861 a departing president Buchanan reduced Utah’s borders drastically by signing legislation to take three “bites” from her western and eastern flanks to form Nevada and Colorado territories and to enlarge Nebraska. It was a loss to be replicated a few years later with reductions at Utah’s expense to form and then enlarge the State of Nevada while creating Dakota and Wyoming territor ies.As President Lincoln prepared to take office in March 1861 as president of a divided nation, the army’s largest garrison was in the desert forty miles southwest of Salt Lake City.

In terms of its immediate impact the Utah War had enormous negative consequences that were economic, geographic, personal, and reputational in character. Some of these consequences—especially the legacy of Mountain Meadows—are still evident today. The Utah War spawned not only ambivalence in Brigham Young but an exotic legacy comprised of rich, colorful, and fascinating personal experiences for thousands of other people that helped to shape the subsequent history of the Civil War, Utah, Mormonism, and the American West.

For many of these participants, the Utah War was a foundational experience in their formative years from which they subsequently sprang into a panoply of even more colorful adventures of both heroic and tragic stripe.27 The stories are legion of how their Utah War experiences shaped the post-1858 world of senior civilian leaders on both sides like James Buchanan, his cabinet officers, Brigham Young, and Alfred Cumming, Young’s gubernatorial successor. And then there are fascinating, well known vignettes involving the Utah War’s most senior military leaders like the U.S. Army’s Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, Brigadier General William S. Harney, and the Utah Expedition’s principal commander, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, as well as the Nauvoo Legion’s senior leader, Lieutenant General Daniel H. Wells. What should be noted at least briefly, though, is that among the junior officers, enlisted men, and even civilians who served under Colonel Johnston during the Utah War, scores of them would become Union or Confederate generals soon thereafter. Several among Johnston’s troops—enlistees as well as officers and even a few civilian employees—were destined to receive the Medal of Honor during the Civil War or the Indian campaigns that soon followed.

One graphic way to illustrate the vastness of the Utah Expedition’s experiential contribution to the Civil War’s talent pool is through the Union and Confederate command structure at a single 1863 battle— Gettysburg. It is a list that reads like a Who’s Who of Utah War veterans. It was a Confederate brigadier, Henry Heth, formerly a captain in the Utah Expedition’s Tenth Infantry, whom folklore credits with touching off the battle. Soon arrayed against Heth and his Confederate comrades—some of them Utah War veterans like General J.E.B. Stuart—were Union generals with similar backgrounds such as John F. Reynolds, late of the Third Artillery, and John Cleveland Robinson, a former Fifth Infantry captain. General Reynolds died famously at Gettysburg; General Robinson survived, later lost a leg, received the Medal of Honor, and went on to command the Grand Army of the Republic and serve as New York State’s lieutenant governor. Also rendering extraordinary service to the Union at Gettysburg were General Stephen H. Weed, a former first lieutenant in Phelps’ battery who died while defending Little Round Top, as well as Generals John Buford and Alfred Pleasonton, both formerly of the Utah Expedition’s Second Dragoons.

Among the most tragic deaths at Gettysburg was that of Confederate brigadier Lewis A. Armistead, killed while fighting his friend and brother officer from the Utah Expedition’s Sixth U.S. Infantry, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, a subsequent candidate for president of the United States. One of the battle’s most dramatic deaths was that of Brigadier General Elon John Farnsworth, a cavalry officer killed only four days after being promoted from captain while leading a gallop against entrenched Alabama troops likened to the Crimean War’s Charge of the Light Brigade. During the Utah War Farnsworth had worked at Camp Floyd as a civilian foragemaster after being expelled from the University of Michigan for his role in a fatal drinking bout. He was the sole Union Army general officer to die behind enemy lines during the entire war.

Lower in the Union Army’s leadership cadre at Gettysburg, one finds First Lieutenant James (“Jock”) Stewart, Scottish-born commander of the battle’s most decimated unit—Light Battery “B” of the Fourth U.S. Artillery, the unit in which Stewart served as first sergeant throughout the Utah War. Like Albert Sidney Johnston, Jock Stewart campaigned in the Civil War astride the horse that he had ridden into the Utah War. While Stewart led Light Battery “B” at Gettysburg, his Utah War comrade in the Fourth, Frederick Fuger, commanded the regiment’s Battery “A” as its first sergeant in helping to repulse Pickett’s Charge, a performance that brought Fuger both a lieutenant’s commission and a Medal of Honor.

On the Mormon side of the Utah War, the military talent was as colorful as that of the federals but not as well known because of the Nauvoo Legion’s almost total absence from the Civil War. Among the most dashing of the Legion’s veterans were a handful of men who during the Utah War carried relatively modest military and church rank but were among the West’s most accomplished horsemen. Best known of these, of course, was Major Lot Smith, a veteran of the Mormon Battalion, from whom came the Utah War’s most famous utterance during his spectacular, fiery raid on the army’s supply trains near Green River during the night of October 4-5, 1857. When an excited federal wagonmaster reportedly shouted, “For God’s sake, don’t burn the trains,” Smith’s reaction was, “it was for His sake that I was going to burn them.” It fell to Smith to command the single mounted company constituting Utah Territory’s contribution to the Union Army, a role that he carried out efficiently as a federal captain although he had earlier served as a militia major.

In 1892, living in self-imposed exile in the slick rock canyons of northern Arizona and somewhat estranged from his church, Lot Smith died of wounds sustained in a close-range exchange of gunfire with a Navajo shepherdin a grazing dispute. A decade later Smith’s body was exhumed and transported north to his former home at Farmington, Utah for an extraordinary recommital service attended by virtually the entire hierarchy of the LDS Church. This was a direct reflection of his standing as the Utah War’s best-known veteran on either side. For years thereafter Lot Smith’s comrades-in-arms from the Utah and Civil wars met for annual reunions at his grave. Even during the twenty-first century uniformed re-enactments of these gatherings continue periodically in Farmington as a gesture of respect for Lot Smith and pride in Mormon military service.

Space does not permit discussion of all the other Utah War soldiers— federal troops as well as Nauvoo Legionnaires—who entered the history books because of their colorful post-war adventures but did so largely unrecognized for their connection to the Utah War in which they earlier served. And so for now it is necessary to pass by the stories of men like Private William Gentles of the Tenth U.S. Infantry, a veteran of Captain Randolph B. Marcy’s epic winter march from Fort Bridger to New Mexico for remounts. It was Gentles whom folklore has delivering the mortal bayonet thrust to Chief Crazy Horse at the Fort Robinson, Nebraska guardhouse in 1877. Then there are Private Robert Foote of the Second Dragoons, a prominent civilian player in Wyoming’s Johnson County War of 1892; Corporal Myles Moylan of the same regiment, who during the Civil War was commissioned and then cashiered, reenlisted as a private under an alias, commissioned again in the Seventh U.S. Cavalry, and retired as a major in 1893 after surviving the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876 and receiving the Medal of Honor; Lieutenant Colonel Barnard E. Bee, commander of the Utah Expedition’s Volunteer Battalion, who died heroically as a Confederate brigadier at First Bull Run after giving General Thomas L. Jackson the nickname “Stonewall”; Bee’s Volunteer Battalion subordinate, Private Benjamin Harrison Clark, who fought in the Civil War, later became extraordinarily proficient in Cheyenne, and served as chief scout-interpreter for Generals Custer, Sheridan, Sherman, and Miles during the post-Civil War plains campaigns; Second Lieutenant Samuel Wragg Ferguson of the Second U.S. Dragoons, the Confederate brigadier who at the opening of the war accepted the surrender of Fort Sumter and who atthe end escorted Jefferson Davis in his last futile dash south from Richmond; and Captain Jesse Lee Reno, commander of the Utah Expedition’s siege battery, who died a federal major general at South Mountain, Maryland.

This 1864 photograph of the Fort Douglas Guardhouse which was constructed in 1862.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Also worthy of mention is William H.F. (“Rooney”) Lee, Robert E. Lee’s second son, who dropped out of Harvard in May 1857 to wangle a lieutenant’s commission in the Utah Expedition’s Sixth Infantry against his father’s wishes. Rooney Lee was to become the Confederacy’s youngest major general, a role in which he was captured on a Virginia battlefield by Samuel P. Spear, a lieutenant colonel of Pennsylvania cavalry whom Lee had earlier met in Utah when Spear was sergeant-major of the tough Second U.S. Dragoons. Spear ultimately became a brevet brigadier general in the Union Army; after the war he led the quixotic Fenian (Irish) invasion of Canada from Vermont.

Of all the later exploits of the Utah War’s veterans, it would be most intriguing to probe further the experiences of Private Charles H. Wilcken, a Prussian Army veteran with an iron cross to his credit, who deserted the U.S. Army’s Fourth Artillery during the fall of 1857, crossed into the Nauvoo Legion’s lines, and converted to Mormonism. Wilcken was probably unique in having served both the federal side and the Latter-day Saints. After the Utah War he took part in many of late nineteenth-century Mormonism’s seminal events. As a coachman, bodyguard, nurse, and eventually pallbearer for Presidents John Taylor and Wilford Woodruff, Wilcken was everywhere and saw everything.28

If Private Wilcken had a rival for most intriguing post-1858 life, it might well be his comrade-in-arms in the Fourth U.S. Artillery, Thomas Moonlight. After the Utah War former Sergeant Moonlight served in the Civil War, rising to brevet brigadier general. His political connections then brought him appointment as Kansas’s adjutant general, following which he became governor of Wyoming Territory and U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia before dying in 1899. It was as Wyoming’s governor that former sergeant Moonlight granted a pardon to that famous Utahn, the Sundance Kid, who also ended his career in Bolivia in spectacular fashion.

All of this is not to say that the Utah War experiences of these veterans were solely responsible for shaping their experiences during the Civil War and thereafter. Obviously there were other influences involved. But there was an impact, and it is important to recognize the connection as a significant contributing factor to the destinies these people met after such a remarkable experience during their formative years. For some of the older Civil War participants, the lessons learned in Mexico during 1846-1848 were, of course, important. Yet what they and their younger comrades later experienced for the first time during the Utah campaign—armed conflict between Americans—was as fresh and vivid as it was unique. It was why in 1858 former Mexican War officers William Tecumseh Sherman, George B. McClellan, and Simon Bolivar Buckner sought so anxiously (albeit unsuccessfully) to reenter the army for the action in Utah.

Would William C. Quantrill have become the Confederacy’s most notorious guerrilla if he had not at age twenty been a civilian teamster, card sharp, and camp cook in the sordid bivouacs of the Utah Expedition? Would John Jerome Healy have become sheriff of Fort Benton, Montana, creator of Alberta’s “Fort Whoop-Up,” and the Alaskan hero of Jack London’s first novel without first campaigning as a teenaged private in Albert Sidney Johnston’s Second U.S. Dragoons? Was the character that Charles R. Morehead displayed as mayor of first Leavenworth, Kansas, and then El Paso, Texas, forged in his boyhood home of Lexington, Missouri, or along the trail to Fort Bridger with Russell, Majors and Waddell?

When the Civil War broke out in 1861 and descended into unimaginable carnage, Brigham Young wrote to Thomas L. Kane of divine retribution and Utah’s contented disengagement. Having shaken off the depression that beset him with the Utah Expedition’s 1858 march through Salt Lake City, President Young was once again the roaring Lion of the Lord. In April 1864, with unintended insensitivity to the cause for which “the Little Colonel” had put his life on the line at Gettysburg and elsewhere, he wrote again to a war-wounded, convalescing Kane:

Self-confident, brooding over past conflicts, and preoccupied with his own millennial thoughts, Brigham Young failed to hear, let alone ponder, the patriotic, hymn-like song drifting westward from the blood-drenched Atlantic Coast. It was music with post-war implications for him and Mormon Utah as well as the Confederacy:

NOTES

Copyright 2012 by William P. MacKinnon. This article is derived from the author’s keynote address of same title for the 59th Annual Utah State History Conference, September 10, 2011.

William P. Mackinnon is an independent historian residing in Montecito, Santa Barbara County, California. He is a fellow and honorary life member of the Utah State Historical Society who published his first article in the Utah Historical Quarterly in 1965.

1 Michael Beschloss, “Missile Defense,” review of Neil Sheehan’s A Fiery Peace in a Cold War in New York Times Book Review, October 4, 2009.

2 For the most significant narrative studies of Utah’s Civil War involvement, see E.B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981 rptd. 2001); James F. Varley, Brigham and the Brigadier: General Patrick Connor and His California Volunteers in Utah and Along the Overland Trail (Tucson: Westernlore Press, 1989); Fred B. Rogers, Soldiers of the Overland, Being an Account of the Services of General Patrick Edward Connor and His Volunteers in the Old West (San Francisco: Grabhorn Press, 1938); and Margaret May Merrill Fisher, Utah and the Civil War: Being the Part Played by the People of Utah in that Great Conflict, with Special Reference to the Lot Smith Expedition and the Robert T. Burton Expedition (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1929).

3 Letters to Lincoln discussed above are all from Abraham Lincoln Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. The first known discussion of James Arlington Bennet’s quirky offer of Mormon troops was MacKinnon, “Stephen A. Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and ‘The Mormon Problem’: The 1857 Springfield Debate,” unpublished plenary talk at Mormon History Association annual conference, Springfield, Ill., May 23, 2009. Subsequent published discussion of this document appeared in Mary Jane Woodger and Wendy Vardeman White, “The Sangamo Journal’s ‘Rebecca’ and the ‘Democratic Pets’: Abraham Lincoln’s Interaction with Mormonism,” Journal of Mormon History 36 (Fall 2010), 96-128 and Woodger, “Abraham Lincoln and the Mormons,” chapter in Kenneth L. Alford, ed., Civil War Saints (Provo and Salt Lake City: BYU Religious Studies Center and Deseret Book, 2012) as well as in Ted Widmer, “Lincoln and the Mormons,” opinion essay of November 17, 2011, in New York Times “Opinionator,” accessed November 17, 2011 at http://opinionator.blogs. nytimes.com/2011/11/17/lincoln-and-themormons/?emc=e.

4 There is no full-length biography of Bennet, although some of his interactions with Joseph Smith and Brigham Young are discussed in Lyndon W. Cook, “James Arlington Bennet and the Mormons,” BYU Studies 19 (Winter 1979): 247-49. Bennet’s legal problems appear in fragmentary fashion in a variety of newspaper accounts, including those in Boston Courier, January 14, 1850, and Savannah, Georgia, Daily Morning News, January 16, 1850. The matter of presidential burial arrangements is discussed in Bennet to Buchanan, June 24, 1857, and Buchanan to Bennet, July 1, 1857, James Buchanan Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

5 Brigham Young to Thomas L. Kane, September 21, 1861, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

6 For context, see Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., The Civil War in the American West (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992).

7 Harding to Craig, August 25, 1862 quoted in Craig to Major General Henry Halleck, same date, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 3, vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899), 596. Unfortunately there is no record of Harding’s meeting with Young. The author’s conjecture is that Brigham Young was offended by his awareness that the Lincoln administration was then in the process of sending a regiment of California volunteer troops to garrison Utah without notifying either him or Governor Harding.

8 Stenhouse to Young, June 7, 1863, LDS Church History Library. Stenhouse, an English-born convert, was then a Mormon newspaperman and emigration agent in Manhattan, who kept the Mormon hierarchy current on eastern affairs. Years later, folklore transformed the phrasing of the most famous part of the Lincoln-Stenhouse interview into a more personalized version by which the president supposedly said, “You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone, I will let him alone.” The slight difference in phrasing is subtle but telling. See, for example, Preston Nibley, Brigham Young, The Man and His Work (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1936), 369. Interestingly, when Young received Stenhouse’s letter, he used its phrasing in describing the White House interview to George Q. Cannon rather than that later attributed to Lincoln by folklore.Young to Cannon, June 25, 1863, LDS Church History Library. One of the few accounts to grasp the distinction between folklore and what Stenhouse actually reported to Young as Lincoln’s words is Chad M. Orton, “‘We Will Admit You As a State’: William H. Hooper, Utah and the Secession Crisis,” Utah Historical Quarterly 80 (Summer 2012): 225 n 73.

9 For a discussion of the few known LDS troops who served other than in Lot Smith’s company, see Robert C. Freeman, “LDS Civil War Stories: Union and Confederate Soldiers,” chapter in Alford, ed., Civil War Saints

10 John Gary Maxwell, Gettysburg to Great Salt Lake: George R. Maxwell, Civil War Hero and Federal Marshal among the Mormons (Norman: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 2010). As for other western territories during the war, Nevada contributed 1,180 men, most of whom served in or around Utah. Arizona Territory was not carved out of New Mexico Territory until 1863, but the latter as well as California supplied multiple regiments of volunteer troops to defend Arizona against raids by Apaches, Navajos, and Confederates. Montana did not become a territory until May 1864, when it was created from eastern Idaho Territory. Montana contributed no Civil War units, wracked as it was by its own sectional partisanship. See Josephy, The Civil War in the American West. Even though much emphasis is given to the Civil War recruitment and service rendered by Captain Lot Smith’s lone cavalry company, it is important to understand its contribution in the context of military service rendered by other western territories during the war.

11 For a listing of such units see Frederick H. Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, 3 vols. (Des Moines: F.H. Dyer, 1908; rptd. Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Book Shop, 1978), vol. 3; Dee Brown, The Galvanized Yankees (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963).

12 John Taylor, Discourse of July 4, 1861, quoted in B.H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Century I, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1930), 5:11.

13 Doctrine and Covenants 87:1-8. At the time Joseph Smith made this prophecy, President Andrew Jackson was dealing with the Nullification crisis in South Carolina.

14 Young to Kane, September 21, 1861, LDS Church History Library.

15 Charles Reagan Wilson in review of George C. Rable, God’s Almost Chosen Peoples: A Religious History of the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) in Journal of American History 98 (December 2011): 801.

16 For a review of LDS Church leaders’ perspective on the war see David F. Boone, “The Church and the Civil War” in Robert C. Freeman, ed., Nineteenth-Century Saints at War (Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center, 2006), 113-39; Richard E. Bennett, “‘We Know No North, No South, No East, No West’: Mormon Interpretations of the Civil War, 1861-1865,” Mormon Historical Studies 10 (Spring 2009): v-xvii.

17 William P. MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point , Part 1, A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008).

18 Young to Kane, September 21, 1861, LDS Church History Library.

19 Brigham Young, “Constitutional Powers of the Congress of the United States.—Growth of the Kingdom of God,” Discourse of March 9, 1862, Journal of Discourses. 26 vols. (Liverpool: Latter-day Saints Book Depot) 10:38-39.

20 Young to Brig. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas, August 25, 1862, LDS Church History Library. The author thanks Prof. John Turner of the University of Southern Alabama, Mobile for bringing this telegram to his attention.

21 Kenneth L. Alford and William P. MacKinnon, “What’s in a Name?: Establishing Camp Douglas,” chapter in Alford, ed., Civil War Saints. Although not documented, it is also reasonable to assume that the California and mining background of Connor’s command did nothing to endear it to Brigham Young. As former residents of the Mormon colony in San Bernardino understood, President Young had long been ambivalent about California as a proper place for Latter-day Saints to gather. Young’s view of mining as an inappropriate Mormon occupation was well known.

22 Brigham Young, “The Persecution of the Saints.—Their Loyalty to the Constitution.—The Mormon Battalion.—The Law of God Relative to the African Race,” Discourse of March 8, 1863, Journal of Discourses, 10:107.

23 McDowell to Doty, October 3, 1864; Doty to McDowell, October 21, 1864; McDowell to Doty, October 22, 1864; photocopies in author’s possession courtesy of Ephriam D. Dickson III, curator, Fort Douglas Museum.

24 Some writers have concluded that as the war progressed,Young mellowed on the subject of Lincoln and grew to respect him. For a study subscribing to this more benign “mellowing” view, see George U. Hubbard, “Abraham Lincoln as Seen by the Mormons,” Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (Spring 1963): 91-108.

25 Minutes of Council Meeting at Logan, Utah, August 23, 1863, Church Historian’s Office, General Church minutes, 1839-1877, Box 3, Fd 34, LDS Church History Library.

26The most recent, comprehensive documentary and narrative accounts of the Utah War of 1857-1858, and the service of Utah War veterans in the Civil War and thereafter, are: MacKinnon, “Buchanan’s Thrust from the Pacific: The Utah War’s Ill-Fated Second Front,” California Territorial Quarterly 82 (Summer 2010): 4-27, “Epilogue to the Utah War: Impact and Legacy,” Journal of Mormon History 29 (Fall 2003): 186-248, and At Sword’s Point; David L. Bigler and Will Bagley, The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, 18571858 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011); Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-1859 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960). A concise account of the conflict is MacKinnon, “Utah War of 1857-58,” essay in W. Paul Reeve and Ardis E. Parshall, eds., Mormonism: A Historical Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2010), 120-22.

27Much of the following discussion of personal stories about Utah War participants is based on MacKinnon, “Epilogue to the Utah War” and “Prelude to Civil War: The Utah War’s Impact and Legacy,” chapter in Alford, ed., Civil War Saints.

28 Charles H. Wilcken is Mitt Romney’s great-grandfather and the namesake of Michigan governor George Wilcken Romney, Mitt’s late father.

29 Young to Kane, April 29, 1864, LDS Church History Library.

30 James Sloan Gibbons (words) and L.D. Emerson (music), “We Are Coming, Father Abraham,” accessed September 3, 2011 at http://www. civilwarpoetry. org/union/songs/coming.html.