52 minute read

Life and Labor Among the Immigrants of Bingham Canyon

CLASSIC REPRINT

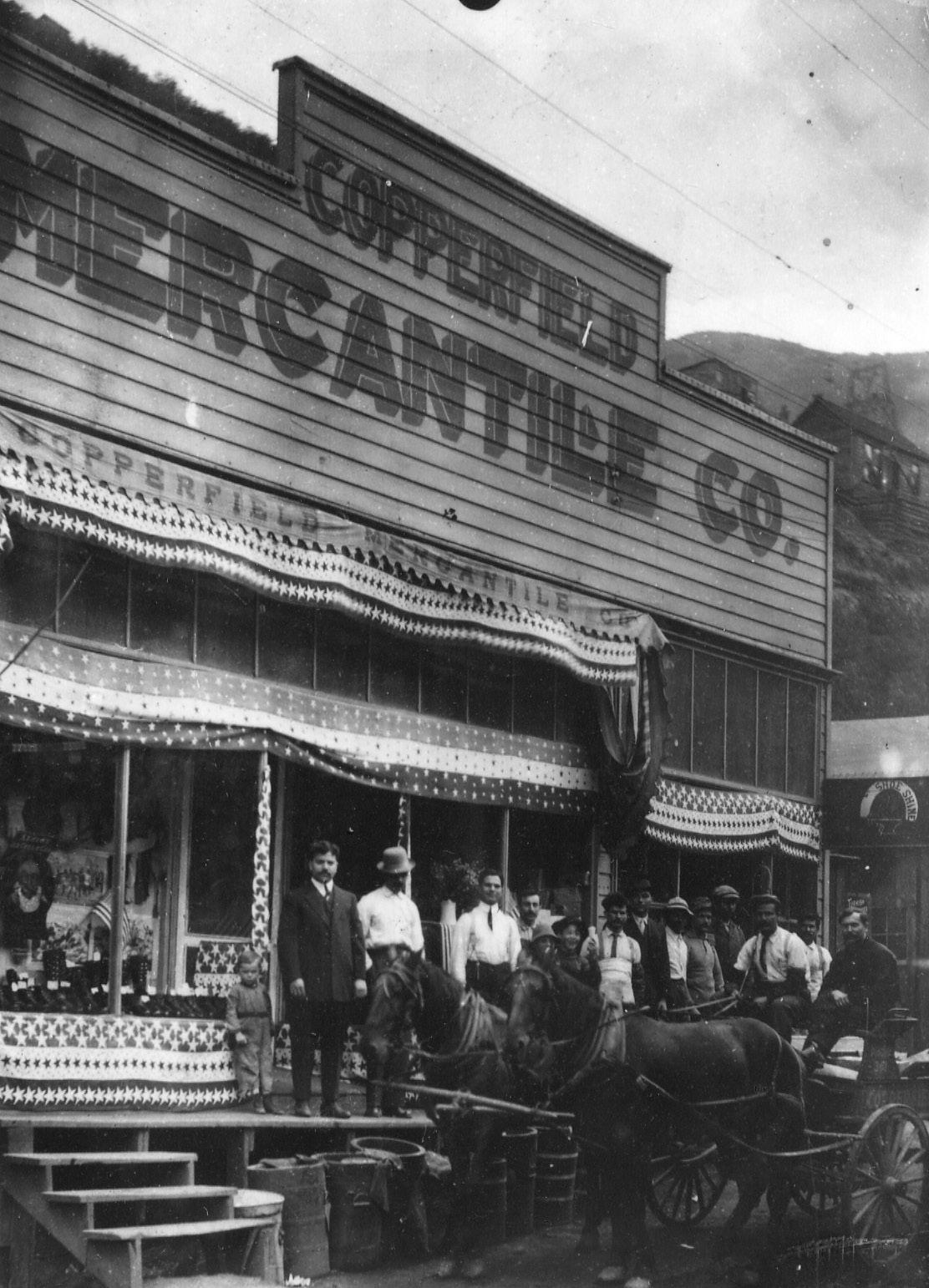

Copperfield Mercantile in Bingham Canyon, Utah. Utah State Historical Society, Peoples of Utah Photograph Collection, MSS C 239, no. 99, box 3.

Life and Labor among the Immigrants of Bingham Canyon

BY HELEN ZEESE PAPANIKOLAS

In 1917, in the little Carbon County coal town of Cameron, Emily Papachristos and George Zeese, Greek immigrants, brought their daughter Helen into the world. Helen Zeese Papanikolas, as she would become, grew up amidst the richness and realities of immigrant cultures in neighboring Helper, Utah. The Zeese family moved to Salt Lake City in the 1930s, and Helen went on to the University of Utah, where she graduated in bacteriology, intent on becoming a doctor. But Papanikolas had other talents as well: she edited the university’s literary magazine and, in 1947, wrote a fictional piece for Utah Humanities Review about a young woman of Greek ancestry. That laid the groundwork for the publication of a path-breaking 1954 essay in Utah Historical Quarterly (UHQ), “The Greeks of Carbon County.” 1

At that point, UHQ had published hardly a thing on immigrant groups—but it was not necessarily behind the times. The study of immigration to America took off in the 1960s, and although Papanikolas’s early scholarship did not employ the theoretical underpinnings of other works, it was unquestionably valuable. 2 Much of that value came not only from her formidable writing skills but also from her entrée into the Greek community and her lifelong understanding of it.

Papanikolas had, after all, attended Greek school throughout her childhood and witnessed Carbon County laborers join a nationwide coal strike in 1922, when she was only five years old.

In 1965, Papanikolas brought all of this—combined with much research—to the writing of the article reprinted below. “Life and Labor among the Immigrants of Bingham Canyon” centers on the Bingham strike of 1912 and the experiences of Greek laborers. Pushed from their own country by poverty, Greeks joined the ranks of wageworkers employed by railroads, mines, and smelters throughout the American West. Among the industrial operations they powered were the copper mines of Utah’s Bingham Canyon. By 1911, some 1,210 Greeks worked in the Bingham mines, which employed a total force of about 4,600 people. In the following year’s strike, the Greeks— with their grievances toward Leonidis G. Skliris, their countryman—played a critical role. 3

Papanikolas told the story of immigrant life in Bingham Canyon with sensitivity and color, and she established the place of the Greeks and other ethnic groups in the history of the growing, global systems of migration, industry, and finance of the early 1900s. Still, some aspects of the following article feel outdated or glib and call for analysis or at least a little more context: the list of newspaper headlines, for instance, or, much more importantly, the unremarked-upon descriptions of “Chinese and Negro ‘water boys,’” “Nigger Jim,” and “Japtown.” Yet, however flawed, this article opened the door for later scholarship, from Papanikolas and others. After “Life and Labor,” Papanikolas published the book-length Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah (1970) as an entire issue of UHQ. She continued writing, researching, and—importantly—interviewing the immigrant generation throughout the remainder of the twentieth century, leaving a foundation for further study of labor, Utah, and the American West.

Immigrants and Bingham’s terrain produced a unique life among mining towns. The long, winding Main Street reached for the cramped houses on the mountainsides and made them part of it. Talk, shouts, and oaths were heard in many languages outside the saloons, boardinghouses, candy stores, theaters, and dance halls. The first of Bingham’s immigrants were the young Irishmen fleeing the potato famine. They worked 10 hours a day on small claims, usually belonging to others, and lived in boardinghouses where they rivaled each other in boxing matches, wood cutting, and other feats of strength. 4 By 1870 the 276 inhabitants of Bingham were mostly Irish who resented the incoming English, the “Cousin Jacks” as they called them. 5 Saloons were many and prosperous, and traveling vaudeville acts were the high point in the miners’ lives.

By 1880 the Irish were leaving Bingham, but immigrants from the British Isles were still dominant. The census for that year lists the following. 6

The majority of the English-speaking miners were Cornish for whom mining was a hereditary occupation. 7 An easy relationship, based on their common tongue and ancestry, existed between the English- and the American-born miners. They held nightly track meets, broad jumped on the dumps, pole vaulted using iron pipes, and threw powder boxes. Boxing matches were weekly events, and men fought until they could no longer stand to the music of mouth organ, zither, and jewsharp. 8

Table 1. Residents of Bingham Canyon, 1880 Census*

Chinese and Negro “water boys” carried water from springs using pails suspended from shoulder poles. The most familiar was Nigger Jim who carried water for 30 years. 9 The water was bad and the sanitation primitive; the only protection for the miners was the old-country prescription of whiskey.

During the next two decades, Finns and Swedes came in greater numbers. Instead of skill they possessed the brute power that mining needed. The Italians followed, mostly Piedmontese, who were proficient at hammer work. They were also adept at leverage, and their stocky build and short legs gave them the nickname “Short Towns.” In the early 1900’s the Eastern Mediterranean and Balkan peoples came. 10 Slovenes, Croatians, Serbs, Greeks, Italians, Armenians, and Montenegrins gave Bingham a color unmatched anywhere in Utah except in the Carbon County coal fields. 11 The Chinese who had been in Bingham since 1875 running restaurants and doing menial labor had, except for a few, left town. Not until 1910 when Japanese and Korean labor gangs were brought in to work on the Bingham-Garfield Railroad construction did Bingham have a large colony of Orientals. 12

A Cretan celebration—possibly a union gathering—in Bingham Canyon, Utah. The banner reads “Pan Cretans Brotherhood.” Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 27216.

Gambling, drinking, bulldog fighting, and cock fighting now took precedence over the simple pastimes of the trackmeets and feats of strength. By 1900 there were 30 saloons on Main Street. “Old Crow” and “16 to 1” were the favorites. 13 The young, unattached men at the peak of their strength could not and, from the period’s court notes it is obvious, did not try to control their restlessness. Disturbing the peace, assault, mayhem, and killing vied with death and maiming of mine accidents to keep the town in continuous excitement.

Each minority was a labor gang in itself, with a foreman who could speak English, and formed its colony around boardinghouses. 14 Names, nostalgic now, immediately told much: Frogtown, where the natives lived; Yampa, a miniature town formed around the Apex Mine; Japtown; Dinkeyville, where powder-box cabins were built on company land; Highland Boy and Phoenix, where the Austrians and Slavs lived; Copperfield, where the Greeks had their boardinghouses; and Carr Fork, where Finns and Swedes had congregated.

Churches came 30 years after mining began. The Latter-day Saints established a church in 1890 as did the Methodist and Catholic churches, but without resident clergy. In 1897 a Methodist Mission Church was opened at Carr Fork, and in the same year Bingham was provided with a resident minister. The Catholic Church did not have a resident priest until 1907. 15 Greek miners traveled to Salt Lake City for religious services.

In 1912 the government immigrant inspector’s report to the U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor showed a complete change in the minority populations. 16 English-speaking workmen were leaving mining for other opportunities, and South Europeans quickly took their places in the mines.

Table 2. Bingham Canyon Ethnic Groups, 1912*

The good and the sordid existed together. Zack (Jack) Tallas, at the time a young Greek fireman in Copperfield, describes it:

The year 1912 was an important period in Bingham’s labor history, union men of great potential but also distrust and apathy. The immigrants “sheviks,” the “Wobblies,” the “labor agitators.” They lived precariously, both needing to make themselves and their principles known to the miners and at the same time hiding their identity from the law. The authorities were alert to the vaguest of rumors on which to base indictments for sedition, and if unsuccessful, they brought vagrancy charges to put labor organizers in jail.

The vast mission field of immigrant labor presented a face to the union men of great potential but also distrust and apathy. The immigrants had to depend on interpreters who knew little more English than they did. They had come, too, from cultures where the rich were the powerful and that was the fate of life. An exception in Bingham was Louis Theos (Theodoropoulos) who was known among his fellow Greeks as an officer of the IWW, and who had done undercover work for unions in the Carbon County coal mines. But in the main it was economics and not ideology that guided the immigrants. In contrast, for example, with the strike activities of the powerful Amalgamation of Garment Workers in the East where the immigrants had settled more than a generation earlier and produced their own leaders, the drawing of immigrant peoples of the West into strikes was emotional and not for principles.

The great Bingham strike of 1912 shows these factors graphically. 18 On May 1 of that year, the Western Federation of Labor called a strike at the lead plant of the American Smelting and Refining Company at Murray demanding recognition of the union and an increase in wages from $1.75 per day to $2.00 per day. The strike lasted six weeks, involved between 800 to 900 men, and closed the smelter for a short time. The strike was broken by strikebreakers, who were Greeks from the Island of Crete, brought from Bingham and Helper. 19 The strikebreakers were sent under orders of Leonidas G. Skliris, leading Greek labor agent in the West. 20 Skliris was called the “Czar of the Greeks,” and as labor agent for Utah Copper Company, Western Pacific Railroad, Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad, and the Carbon County coal mines in Castle Gate, Hiawatha, Sunnyside, and Scofield, he had great power. 21 His contacts with labor agents in Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, and California could, within minutes of a telephone call, have men on a train traveling to a destination where they would be hired as workers or used as strikebreakers.

The labor agents of those years worked under the padrone system. 22 The Italians, Greeks, and Japanese were dependent on this system to get work from their respective labor agents. They were the last laborers to be given work. The Japanese padrone system was of a different nature; housing and food were included in their contracts. 23 The Sako brothers, who represented Japanese labor in Salt Lake County, had camps in Magna and Garfield that housed between 400 and 500 men.

The Italian padrone system, loosely organized in the Carbon County coal camps, does not appear to have been in effect in Bingham. Fortunato Anselmo, the present Italian vice consul, denies it existed there. Italians found employment through relatives and countrymen. The various Balkan peoples (often listed as Austrians in official reports), Croatians, Serbs, Slovenes, and Montenegrins were divided by many diverse reasons: by old-country politics, by two different alphabets, and by three religions—Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Greek Catholic. A padrone common to them all would have been impossible. 24

The Greeks, however, were by far the majority of workers in Bingham, and Skliris was the dark force in their lives. The Greeks bitterly resented the suave, well-dressed countryman who lived in the amazing luxury of the newly built Hotel Utah on the money he exacted from them. One of the young miners waited for Skliris outside of the Hotel Utah with a pistol, but Skliris quickly disarmed him. Skliris did not lack courage and this kept him alive in his 15 years as a labor agent.

Leonidas G. Skliris, the “Czar of the Greeks,” was a powerful labor agent, or padrone, who came to be reviled by many of his countrymen in America for his practices. Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 13539.

For almost two years Greek miners had tried to expose Skliris as an extortionist who exacted tribute before handing out jobs and threatened the miners with discharge if they did not trade at the Pan Hellenic Grocery Store. A further grievance was the paying of higher wages to the Japanese who usually worked as bank men. With ropes tied around their waists, they lowered themselves over the banks and swung their picks into the ore—a dangerous occupation.

It was an auspicious time for a strike. When the officials of the Western Federation of Labor began their talks, they found the Greeks incensed and ready. The anger of the Greeks explains the phenomenal success of the Federation in the summer of 1912. Voler V. Viles’ report to the U.S. Department of Commerce showed 250 union members in July, 900 on August 27, and 2,500 in October. 25 At the meeting on the 17th of September, which was attended by at least a thousand miners, President Charles W. Moyer of the Federation asked that further attempts be made to negotiate with the mine officials before calling a strike. 26 At the time the payscale was $2.00 per day for surface men, $2.50 per day for muckers (diggers), and $3.00 per day for miners. 27 The union intended to ask for recognition of the Federation and a 50 cent a day raise for all workers.

The men refused Moyer’s suggestion and unanimously voted a walkout immediately affecting 4,800 men. The American-born miners had stayed away from the meeting, not wanting to align themselves with the “foreigners.” Another 150 steam-shovel men of American nationality were opposed to the strike, but “did not want to go against the wishes of the majority.” 28

Fifty National Guard sharpshooters from Fort Douglas and 25 deputy sheriffs from Salt Lake City, supplied with several thousand rounds of ammunition, were brought in. Rifles from the munition stores of the Utah National Guard were made ready for delivery to Bingham. Saloons and gambling halls were closed, and railroad crossings and mines were floodlighted. 30

The day after the walkout, President Moyer told 800 strikers at the Bingham Theater that the union officials had waited all day for an answer from the mine managers and had not received one. R. C. Gemmel, of Utah Copper, told the press that “we do not treat with officers of the union regarding matters connected with the mines. We do not recognize the Federation.” 31 Gemmel said, “I don’t think they [the miners] have any grievance. It is the officials of the miners’ union who have stirred up trouble.” 32 He stated the following day that “We advanced the men twenty-five cents [to become effective in November]. This was voluntary.” 33 If the miners would work through committees, Gemmel claimed, the trouble could be adjusted.

President Moyer countered, “as for the men meeting with the companies as individuals, I will only say that a great many of them cannot speak the English language, and their only opportunity is through their authorized representatives.” 34 Moyer denied the raise to the miners was voluntary, insisting it was the result of a similar raise in the mines of Montana the past June. Even a 50-cent increase, he said, would be less than what the Montana miners received for the same work. 35 Moyer stated that “their [the miners] hours are too long and the current high price of copper justifies the raise.” 36

The strikers took blankets and guns and settled in advantageous positions on the mountainsides. On the morning of September 19th, the strikers were given until noon to leave the mines; and if this ultimatum was defied, Salt Lake County Sheriff Joseph Sharp threatened to send 250 deputies armed with Winchesters. 37 Governor William H. Spry said, “We are going up on the hill and drive them down.” The governor was believed to be, according to the Deseret Evening News, “one of the party [who wanted] to attack the foreigners stronghold.” 38

A last attempt was made by President Moyer to convince the strikers to leave the mountainside. He sent Yanco Terzich, a director of the Federation, with his message, but his climb was in vain. 39

While the union spoke of wages, the Greeks, mostly Cretans “famed as men who, when the spirit moves them to fight, are difficult to control,” 40 were concerned first with getting Skliris fired. 41 Utah Copper Company posted notices in the Greek language informing the men that they were not required to pay for their jobs, and Vice-President Daniel C. Jackling in San Francisco for business meetings sent a telegram to the same effect. 42 Mr. Gemmel defended Skliris; and Governor William Spry, in response to a letter from one of the Greeks explaining Skliris’ extortion practices, sent out a “Greek detective” who predictably found no such practices. 43

A general view of the Utah Copper Company mining area, looking down Bingham Canyon, March 17, 1911. Utah State Historical Society, Shipler no. 11626.

Jackling, Moyer said, refused to believe the padrone system existed, perhaps because he was too busy. “I believe he does not look to the methods of Skliris and his ilk, but simply asks cheap labor no matter how it comes.” 44

Governor Spry quickly called a meeting with Sheriff Sharp, Adjutant General E. A. Wedgwood (commander of the National Guard at Fort Douglas), and the mine operators to discuss the calling out of the militia and the proclaiming of martial law. Moyer and Terzich were invited to give testimony as to whether “the striking foreigners [were] amenable to the counsel of the strike leaders.” The Salt Lake Tribune continued: “In Bingham the belief is prevalent that the foreign element among the strikers will be a law unto themselves despite the protestations of President Moyer.” 45 The union, Moyer admitted, could not handle the Greeks. 46

“Foreigners” had bought arms in quantity from Salt Lake City hardware and sporting-goods “stores.” The men are known to be from Bingham because they took the 3:15 train back to that camp.” Bingham store owners had stocked up on revolvers. They were requiring cash for all merchandise and were not sending out their delivery wagons. Druggists were told not to sell liquor. Deputies were arriving on every train. 47

The Salt Lake Herald Republican reported on the “vile conditions” of the powder-box houses where miners slept in shifts and yet sent $580,000 in money orders to Europe during the past year. 48 In Bingham businessmen and native Americans were hostile to the strikers knowing the long economic misery that would come to the town. Rumors and attempts to prove the immigrants ungrateful to America kept the town in an upheaval. All mines now except the Apex, which was working under Moyer’s orders, were out on strike. Only Ohio Copper officials would consider a conference with the union. In San Francisco Jackling told the press, “When I fight, I’ll fight hard.” 49

The strikers remained on the mountainside, and the deputies did not go up and drive them down. The attack was delayed by rumors that strikers had broken into the Utah Construction tunnel and stolen 60 cases of dynamite. While the deputies hesitated, 200 Austrians descended on the Denver and Rio Grande trestle between lower and upper Bingham and fired on anyone attempting to cross it. 50

Governor Spry had expected the strikers to heed the ultimatum to leave the mines and was waiting in the Bingham Theater to talk with the men. His visit seemed fruitless until a bearded priest in black robes with the tall black kalimafkion on his head walked up Main Street and up the mountain.

There, Sheriff Sharp wisely decided not to disarm the strikers although 250 deputies were at his service. The Greek miners “declared with vociferous acclaim” that they would go back to work at the present scale if Utah Copper would refuse to have anything to do with Leonidas G. Skliris, “Czar of the Greeks.” A carpenter, John (Scotty) Curie, speaking with a brogue, told the mine officials that the Greeks should not be given the entire responsibility for the strike because Italians and Austrians were also involved. Skliris, he told them, was the strike issue. Chris Kiousios repeated Scotty’s speech in Greek to the strikers’ “thunderous applause.” N. P. Stathakos, a Greek banker, spoke to the Greeks urging them to be peaceful.

A telegram was read from D. C. Jackling, representing Utah Copper, reiterating his previous statement that men did not have to pay to get jobs at Utah Copper. Governor Spry spoke in platitudes, and Robert C. Gemmel defended Skliris. Angrily the strikers left to continue the strike. 52

Moyer was asked to take Governor Spry and his party up the mountainside. The barricades were empty but “Cretans with rifles were far up. When Moyer’s attention was called to them he said they were probably hunting jackrabbits.” 53

The next day about 300 strikers patrolled the Bingham-Garfield Line ready to shoot at strikebreakers who were being brought into town. The Greek strikers, hearing that Skliris along with two Magna Greeks (Gus Paulos and Nick Floor), was now recruiting strikebreakers, became infuriated and taking a good supply of ammunition returned to their positions on the mountains.

Despite the strikers’ vigilance strikebreakers were finding ways of entering Bingham unnoticed. The townspeople were asking why the patrols had not been disarmed, and the sheriff’s office assured them that this would be done in the afternoon. People were leaving the canyon by the hundreds on the daily trains. The newspapers reported “White residents leaving camp, . . . The two daily trains carry about 200 of the better element of the camp, . . . the foreign element of Greeks, Italians, Austrians and Cretans are dominant in a situation into which the ‘white’ element has been forced against its will.” 54

The steady increase of deputies gave no confidence to the people of Bingham. Moyer said that among them were “irresponsible riff-raff of Salt Lake.” 55 Promiscuous shooting, theft, drunkenness, and the accidental killing of one deputy by another bore this out. 56 Moyer asked if Sheriff Sharp and Governor Spry would “deputize a couple-hundred armed men to protect the strikers from the gunmen of Utah Copper . . . the strikers, many of them citizens, who have committed the awful crime of banding together and demanding a better pay of their employers.” 57

Skliris returned from Colorado and Idaho where he found young unemployed Greeks through the labor agents, Karavellas and Babalis. He defended his 15 years as a labor agent in the West, insisting that he would pay $5,000 to anyone who could prove the padrone charge, the money to be used as a monument for Governor Stuenenberg or for any other appropriate purpose. 58 The Greek employees of Utah Copper were loyal, he said, but were coerced by an armed mob. 59

Ernest K. Pappas, spokesman for the Greeks, answered Skliris saying, “Where there is so much smoke, there must be some fire.” His letter to the Deseret Evening News continued:

This padrone has grown rich on his exploitation of Greek laborers whom he had induced to come to California, Utah, Nevada and Colorado by advertising in all Greek newspapers in the United States. These newspapers are widely circulated in Greece and Crete. On arrival these immigrants pay Skliris or his underlings $5 to $20 or more. This applies not only to Bingham Canyon, but coal mines at Castle Gate, Kenilworth, Helper, Sunnyside, Scofield, etc.

The Greeks would not have left the mines had the padrone system not been in effect.

As to the grocery store charge, it is well known that Steve G. Skliris, Leon G. Skliris’ representative, approves every Greek hired by Utah Copper and threatens with dismissal those who do not trade at Pan Hellenic. Goes farther by saying, “Your account this month is too small. You’ve been buying elsewhere. We look out for your job, you look out for us.” . . . If Greeks are loyal, why did they join union head first, 700 in one night took oath to gain freedom from padrone system. I accept Mr. Skliris’ offer of $5,000 . . . deposit in a Salt Lake bank with three judges appointed to decide question, one to be appointed by Governor Spry, one by Western Federation of Labor and one by Utah Copper. 60

Two days later Skliris resigned. Nothing more came of his $5,000 offer. The Greeks celebrated in the Copperfield coffeehouses before gathering again on the hills. 61 At this point they were ready to go back to work, but President Moyer convinced them that Skliris’ resignation was secondary to the union’s demands, and the strikers themselves were wary of Skliris fearing he had “made a deal” with the Utah Copper and would again supply the company with labor as soon as the strike was over. 62

The strikers became better organized and formed themselves into six-hour shifts with over a thousand men on picket duty. Skliris’ resignation had brought the first sign of optimism to the town.

Miners spent their free time repairing their cabins, but,

The Japanese, the better-paid gambling companions of the Greeks, had also gone out with the rest of the men.

The union leaders now threatened a general strike if the union was not recognized. Strikebreakers were steadily infiltrating into Bingham, even though strikers were covering all entrances to the town.

The mine operators continued to ignore the union, and the Federation ordered 3,000 miners out at the Ely Nevada Consolidated Mine. 66 In Bingham the operators were hopeful at activity which they misconstrued as the Greeks leaving Bingham. However, the Greeks had heard rumors that the companies were going to evict them from the powder-box houses they had built on company land and were taking the precaution of moving out of them before they were forced to leave. 67

Strikebreakers were coming into town in growing numbers. Nearly 500 were already settled in passenger trains made into sleeping cars in Bingham, and in six boxcars with kitchens at the Magna rail yards. When a sufficient labor force was brought together, work would be resumed, the mine officials said. Rumors that Utah Copper had three machine guns were denied by its officials; Jackling reiterated that the mines would “have nothing to do with the Western Federation”; and on October 10 strikebreakers, mostly Greek, were brought in by boxcar. 68

Heavily guarded by mine guards and deputies, Highland Boy, owned by Utah Consolidated, began work with 50 strikebreakers on October 9; and the next day a skeleton crew of 100 men, using one steam shovel, resumed work at Utah Copper. Fighting between guards and strikers broke out. In one incident an unarmed Greek, Mike Katrakis, was ordered back by Sam Lewman, a guard, and shot in the leg as he turned. 69 The Greeks became enraged and met at the Acropolis Coffeehouse owned by the Leventis brothers, one of whom, John Leventis, was the acknowledged leader of the Cretan strikers.

The streets were crowded and the miners were in an uproar over the shooting which required amputation of the striker’s leg. Deputies said the shooting was accidental, but two Italian women who witnessed the shooting said it was intentional. The Greeks reported their houses had been entered by “several hundred gunmen” and ammunition and money stolen. A thousand Greeks met in the Greek Orthodox Church in Salt Lake City and sent a telegram to their consul in Washington, D.C., protesting their treatment and asking for an investigation. 70

Hundreds of strikebreakers were still arriving each day, and by the middle of October 5,000 were expected to be at work. The majority of these were miners from Mexico who had been driven out of their country by the revolution and gone to California. Another 500 had been sent to Utah Copper by a New York labor agency. A later force arrived from Arizona and Mexico, and another 150 arrived the second week in November from Mexico and Wyoming. Utah Copper built housing for them behind the Bingham and Garfield Railway Depot. 71

Tooele smeltermen, as the workers at Garfield had done earlier, passed a resolution refusing to handle ore mined by strikebreakers. 72 To bring attention to their claims that deputies were committing “unlawful acts” under legal sanction, strikers and sympathizers held a rally that filled the Salt Lake Theatre. 73

On October 25 a battle in Galena Gulch, between strikebreakers and deputy sheriffs and strikers, ended with five men wounded of whom one, Harris Spinbon a Greek, died two weeks later. 74 The next day John and Steve Leventis were taken into custody at their coffeehouse on suspicion of having been involved in the shooting. On November 4, 40 Greeks were arrested at the Acropolis Coffeehouse. Yanco Terzich, the Federation director, and E. G. Locke, the local secretary, tried to prevent the arrest of the men and were in turn arrested. A week later at the same coffeehouse, deputies went in to arrest Zaharias Rasiaskis (Rasiskis) in connection with the shooting at Galena Gulch, and in the fight that followed three Greeks were shot. One of them, George Padaladonis (Papandonis), died two days later. J. H. White and another officer, Phil Culleton, of the Bingham Police Department, went to the aid of an unarmed Greek who was being beaten by two guards. White arrested the guards and was discharged for his efforts. Culleton was given a future hearing. 75

On October 31 Mr. Jackling of Utah Copper announced the company was ready to increase wages, as had been planned at the beginning of the strike, by 25 cents per day. This was to go into effect the following month and would include the Ely and McGill mines. This, Mr. Jackling said, was in accordance with a 1909 agreement that specified an automatic increase in wages when copper reached 17 cents a pound. 76

The announcement had no effect on the miners. Six weeks had passed with no sign of capitulation on either side. The miners were in desperate need. The Butte, Montana, members of the Western Federation sent help by voting $7,000 for the relief of the strikers. 77 Single men asking for relief received $3.00 per week and family men $6.00. 78

The strikers hoped that the companies would be willing to make concessions as the

November 15 termination date of the strikebreakers’ contracts approached. They hoped, too, that the inefficiency of the strikebreakers—caused by their lack of skill, their not being disciplined for regular work, and their being physically unaccustomed to hard labor—would force the companies to reconsider their position. The companies showed no sign of retreating, and the strikers saw the futility of their cause. The strike gradually died. The Federation remained unrecognized, and the 50-cent raise asked by the miners was denied. A 25-cent raise was granted to the muckers and miners; the surface men were raised 20 cents. 79

During the duration of the strike, the mining industry suffered badly as did the smelting and milling plants, such as Garfield. Normal operations took five months to achieve. Business and transportation were seriously affected in the entire county. 80 The killers of the two strikers were never apprehended.

The importance of the strike cannot be underestimated. It broke the power of Leonidas Skliris who went to Mexico and became part owner of a mine there. The padrone system was brought into the open, and officials could not longer pretend it did not exist. The immigrant inspector’s report for the year included the following:

An after effect of the strike was a new immigrant minority in Bingham. Many of the

Mexican strikebreakers remained. They now became the majority of cases on the court calendars, and gave Bingham its celebrated Lopez mystery. 82

World War I was now being fought in Europe, and American industry responded with increased production. In 1916, 14 million tons of metal ore were mined in Utah; 13 million of it in Bingham. This represented increased production of 77 per cent over the previous year. At Bingham and the Utah Copper Company mills in Magna, workers’ salaries had been increased better than 35 cents a day. 83 An attempt was made by the IWW under Big Bill Haywood to promote a strike, but it was unsuccessful. 84 The town reached the peak of its population and was in a continual state of flux from many forces.

The newspaper serving the town, the Bingham Press Bulletin, was an instant mirror of the attitudes toward the immigrants and the disparate news they produced. A half century later it gives an interesting picture of the town. Samplings for the year 1918 follow:

Mike Concas assault on Dan Cardich with deadly weapon. It seems Mike invited Dan outside at a party and then hit him over the head with shovel or club. (January 18)

Jap Greek White Slave Case

A queenly maiden from Missouri known to her friends in this section as Billie . . . crushingly beautiful, . . . worked in house in Copperfield for two years Japanese Yoko accused Billie of taking $100. Billie denied “cabbaging” money but beat it out of the neighborhood to Salt Lake with the Greek. Appears Jap loved Billie and Billie loved the Greek . . . found at the Newhouse Hotel. In Billie’s muff officers found $1,400 and a thousand dollars in diamonds. (February 1, March 8)

Foreigners Registering This Week (February 8)

Mucker terribly mangled by old shot. Greek employed in Montana-Bingham loses both eyes and is badly lacerated about the body when he strikes old blast with pick. (February 8)

Bingham Oriental Enlists in Uncle Sam’s Army (February 15)

Italian Boarding and Rooming House in mining town of Bingham. Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 16911.

Meatless and Wheatless Days (February 22)

Commercial Club Gives Farewell to Serbians

Serbians have already sent 90 to front (March 22)

Italians Hold Patriotic Meeting in Commercial Club

Greater part of program in Italian tongue (April 5)

Chin Ming Silk Movie Operator Died Suddenly

He was about 30 years of age and was one of the best Chinese in the camp. (April 5)

J. A. Young Assists Foreigners to Fill Assessment Blanks

Mr. Young spent the first of the week with the foreigners, many of whom were unable to speak English. Still he was greatly impressed with their honesty. Mr. Young is well pleased with the people of Bingham and was agreeably surprised

to find them so much better than he had been led to believe from the distorted accounts he had read of Bingham in the Salt Lake papers. (April 12)

Vasil Malinch Killed in Apex MineNative of Serbia (April 26)

Finns Resent Broadside in Salt Lake Paper

A big mass meeting Sunday night in Swedish-Finnish Temperance Hall to protest article in Salt Lake Tribune alleging 125 Finns as I.W.W.’s [had] been discharged from Bingham mines was branded falsehood. . . . believed caused by animosity towards their temperance movement and trying to clean up the camp, improving moral conditions. Denied Finns pro-German. . . . He also stated that the Finns were not strike agitators and that among them all in the great strike of 1912 not more than three or four voted for the strike and since America entered the war they were unanimous in their opposition to strikes. (May 10)

Joe Melich Goes to New York

Joe Melich prominent business man and official of Phoenix [Mine] will leave for New York to attend important national meetings of Serbian organization. (May 10)

John Sakellaris, native of Greece, invested entire savings $2,000 in bonds! First Greek citizen to invest such a large sum. Believe encouragement to other Greek citizens. (May 10)

Smith in Court on I.W.W.

Charge Eugene Smith alleged financial agent of I.W.W. in Utah charged with obstructing the recruiting and enlistment services of U.S. and hampering the work of the military forces and alleged to have made statements that “War is only murder “ and that American soldiers—that is, the militia—murdered and cremated women and children in Colorado. (May 10)

The Jesse Knight Miners are on Strike

Demand a pay day every two weeks instead of monthly. (May 17)

Patriotic Meeting for Red Cross

A rousing address by Greek consul, Mr. Pappalion and he spoke in English and Greek. (May 24)

Nearly 500 Draft Slackers Quizzed in Bingham

A large number of foreigners expressed willingness to serve, but some preferred being sent back to native country. (May 31)

Gamblers RaidedOne Japanese others Greek (June 21)

Restaurants Discard Sugar Bowls (July 12)

Sheriff Corless Warned Not to Destroy Booze Warning not to destroy anymore booze or may come in contact with T.N.T. Defender of booze says some miners connected with I.W.W. (August 9)

Isolation of Huns Favored by Speaker (September 6)

Call for Strike Monday Morning Not Heeded

Called by M.M.W.I.U. 80 branch of I.W.W. from Butte (September 6)

Bingham Has a Big Honor Roll

The Great Copper Company has 284 men for Uncle Sam’s Army. All nationalities represented (September 20)

Proprietors of Independent Grocery brought in whiskey marked as olive oil. (September 20)

Japanese Hold Liberty Mass Meeting (October 4)Influenza Spreading (October 4)

Serbians at Highland Boy gratified at conclusion of war celebrate with old-fashioned barbecue of ox. (November 15)

The war catalyzed changes that were evolving. The Southern Europeans were leaving the mines, and Orientals were becoming more numerous. In 1919 the Utah Copper Mine listed the following 1,800 employees. 85

The intensified production needed for war had brought a great number of men into mining and kept the copper and lead market favorable. With the end of hostilities, the oversupply of labor became evident, and the copper and lead market declined. By 1920 the mines had reached a low in output, and by 1921 metal mining was in “its worst condition in more than a generation . . . in condition of complete collapse by end of year.” Utah Copper was idle as were Utah Consolidated, Utah Apex, Ophir Hill Consolidated, and Utah Metal and Tunnel. 86

In 1922 a sudden revival in the market opened Utah Copper in April, and by autumn the output was half of normal capacity. The increased mechanization of the mines had brought problems which were new to the industry. Machinemen were needed, but the “old timers” preferred mucking, even though it paid less. The shortage of men was in part due to the Johnson Law which restricted immigration from any country to three per cent of that nationality in this country. This caused a drop of immigrants in 1921 to 355,000 compared with 1,218,480 in 1914 and 1,197,892 in 1918. 87

Table 3. Utah Copper Mine Employees, 1919*

Laundry draping the street in the mining town of Bingham, 1917. Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 15031.

Industry blamed the unions for their situation.

The shortage of drill men, particularly of the better type of English-speaking miners is a serious matter. One reason as already stated is the difficulties under union regulations of teaching young men the technique of drilling and blasting rock underground. Some means must be found to do so. 88

Although the mine operators during this time were still very conscious of a miner’s nationality, they stopped taking count of this specifically.

The reports of the Utah State Industrial Commission included the nationality of the dead, maimed, and injured for identification purposes and also the small sum that the companies paid to the survivors—most often in the miners’ native lands.

The immigrants and native Americans had an especially good relationship during the twenties. One important reason for this can be traced to the Copper League Baseball that was organized in April of 1923. 89 Bingham had had a baseball team since April 5, 1918, but the Copper League included all the mine and smelting camps. The League inspired community interest and feeling and gave the sons of immigrants an identification with their town and a sense of equality with the sons of the native born.

The newspaper still reported killings and “disturbances” by “foreigners,” particularly bootleg violations, but there was no sign of the Ku Klux Klan incidents that occurred in Magna and Carbon County. 90 The Bingham Press Bulletin of February 28, 1925, said: “The Klan parade at Salt Lake Monday evening surprised even those who are supposed to be well posted.”

Bootlegging involved the natives as well as the immigrants. It appeared at times to be a community project. A federal grand jury in May 1928, indicted 40 “citizenry, including people prominent in local circles” for conspiracy in running a bootlegging ring. 91

By the end of the 1920’s, the pattern of immigration became apparent again. The older immigrants who had caused the “disturbances” which were recorded in court notes a decade or two earlier had been marrying and raising children. Seldom now were the old-country names of the Continent carried in the court notes, except, of course, for bootlegging. The newer immigrants of this hemisphere, particularly the Mexicans, were the disturbers of the peace and the authors of violence. 92 Even the collapse of the economy did not change this.

The depression of the 1930’s brought out a valiant effort by the town to relieve “the distress of unemployment.” Benefits were held continually. Jobs of cleaning out flumes and improving roads and culverts gave temporary help. A work center was organized for women whose husbands were without work. The women sewed and quilted for general relief of needy families for $1.25 a day. The reduction of copper production cut the employees’ time. The policy of the companies was to hire more men at less time to help alleviate the destitute condition of the miners.

The WPA brought an education program for the unemployed—teaching English, Spanish, typewriting, stenography, bookkeeping, domestic arts, and shop. Schools were barely saved from closing. Union activity continued, helped by the Wagner Act which made strikes legal. An abortive strike occurred in 1931. A strike in the underground mines of Bingham and Lark, where the miners were members of International Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, was called on October 12, 1936, and settled on December 18 after extreme suffering by the strikers’ families. The miners asked a pay increase and an eight-hour portal-to-portal shift as at Tintic. The settlement called for a 25-cent pay increase per shift and no discrimination because of strike activity. 93

Throughout the depression years the immigrant generation and their children continued their old-country celebrations. The Serbians on Lossovo Day (commemorating the battle of Serbs and Turks on the Plain of Blackbirds, June 28, 1389) barbecued young pigs and recalled their native country’s songs and dances. The Greeks on Saints’ Days barbecued lambs and sang epic songs of their 400-year bondage to the Turks. The Italians on their national holidays prepared pasta dishes and could well have been, for the moment, in Italy. The songs and dances of various native countries are remembered by the native Americans to this day. Doctors, especially, and other professional people were invited to the celebrations as a sign of respect.

The war years of the forties again brought great activity to Bingham, but the immigrant generation had become the steady workers, living a quiet life. Their children were working in the mines and serving in the Army. The street was still the recreation of the immigrants. “One of Bingham’s most used recreation centers is the sidewalk. The men of the town congregate on steps and low walls to talk things over. The conversations exchange opinions in several languages.” 94

Their young people were marrying and raising families. Their sons, more often of Yugoslavic origins in contrast to those of Greek roots whose fathers left the mines in the twenties, were making mining, as it had been for the first Cornish miners, a hereditary occupation.

The immigrants had fared better in Bingham than those in other western mining towns. Along with the crowded, narrow terrain with its long ribbon of Main Street that made for close, colorful, and tolerant living, were exceptional people dedicated to the welfare of the immigrants. There were many native Americans who gave the immigrants the same respect that they gave each other. There were many immigrants who were hard-working and grateful to be in America, people such as the Catholic Creedons who ran a boardinghouse, Charles Demas from Greece who owned a grocery store. They represented industriousness and integrity that the American has always prized.

The interior of the Highland Boy Community House, with Ada Duhigg and a group of women and girls participating in a basket-weaving activity. Duhigg, a deaconess of the Methodist Church, established and ran the Highland Boy Community House as a place of recreation for the youth of Bingham. Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 17026.

All mining towns had worthy immigrants, but in Bingham the liberal attitude of the professional people reflected on the general population and made for the more enlightened atmosphere. In comparison with Carbon County, for example, where doctors, lawyers, and teachers usually stayed a short time and were often hostile to the immigrants, Bingham’s professional people were long-time residents, actively interested in the immigrants.

Doctor F. E. Straup, the autocratic mayor of Bingham for many years, came to the “camp” with less than a dollar expecting to die of consumption. He stayed, survived, and thrived. Dr. Russell G. Frazier (physician with Admiral Byrd’s 1939 antarctic expedition) and Dr. Paul Richards’ lives are interwoven with that of Bingham. Their work among the miners and their families is of the kind that inspires biographers.

John Creedon suggests that with passing time, mine managers felt closer to their workers and sponsored athletic programs and other civic projects for their benefit. The Gemmel Club was of great value to the community. Later managers lived in Bingham, and the absentee-landlord stigma was replaced with a sense of common ties. Louis Buchman, of Utah Copper; V. S. “Cap” Rood, superintendent of Apex; and Frank Wardlaw, of Highland Boy—all lived in the town.

The Catholic priests of the twenties and thirties did a great service to the youth of Bingham with their baseball and basketball programs as part of the Catholic Youth Organization. The relations between the immigrant children and the “American” children were better and closer than in most mining and smelting towns and can be traced to the efforts of priests, the Franciscan Sisters, ministers, and other religious representatives working together for the young people.

In Highland Boy a deaconess of the Methodist Church, Miss Ada Duhigg, came as a young woman and remained to help and comfort immigrant families. She kept a community house open to all nationalities. There she held kindergarten, provided a gymnasium, conducted funeral services, and helped those who were in need. Miss Vern Baer, well-loved teacher of an army of Bingham children for 32 years, says of Miss Duhigg,

Dismantling of the Thompson Building, Bingham Canyon, Utah, 1962. With the expansion of operations of Kennecott Copper Corporation, homes and businesses were purchased and dismantled. The Thompson Building had served as a rooming house, a bar, barbershop, and even a jail at one time. Utah State Historical Society, photo no. 15037.

With people such as these, with the vigorous life of which they were a part, and in the narrow, protected canyon that gave security, the immigrants found their new-world home. Their exodus in the early 1960’s, made necessary by the needs of the copper industry to expand their operations into the canyon, was their second uprooting. They lingered until the final moment. To leave their town was as hard for them as the leaving of their native lands when they were young. The old-timers feel their dispersion strongly and recall with nostalgia their town that has now only vestiges of what it had been. They know with regret that some day there will be no trace of the life that had been lived in Bingham Canyon.

Web Extra

Read more about Helen Papanikolas and Utah mining at history.utah.gov.

Notes

1 Miriam B. Murphy, “Helen Zeese Papanikolas (1917–): A Unique Voice in America,” in Worth Their Salt: Notable But Often Unnoted Women in Utah, ed. Colleen Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1996), 243–56; Philip F. Notarianni, “In Memoriam, Helen Zeese Papanikolas, 1917–2004,” Utah Historical Quarterly 73, no. 1 (Winter 2005): 87–88; Helen Z. Papanikolas, “Growing Up Greek in Helper, Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 48, no. 3 (Summer 1980), 244–60; and Katherine Kitterman, “Helen Zeese Papanikolas, Historian and Folklorist,” Better Days 2020, accessed August 15, 2019, utahwomenshistory.org.

2 David A. Gerber, “Immigration Historiography at the Crossroads,” Reviews in American History 39, no. 1 (2011): 74–86.

3 Charles S. Peterson and Brian Q. Cannon, The Awkward State of Utah: Coming of Age in the Nation, 1896–1945 (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society; University of Utah Press, 2015), 121–27. For further reading on Bingham Canyon and the strike of 1912, see, among others, Gunther Peck, Reinventing Free Labor: Padrones and Immigrant Workers in the North American West, 1880–1930 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000) and “Padrones and Protest: ‘Old’ Radicals and ‘New’ Immigrants in Bingham, Utah, 1905–1912,” Western Historical Quarterly 24, no. 2 (1993): 157–78; Bruce D. Whitehead and Robert E. Rampton, “Bingham Canyon,” in From the Ground Up: The History of Mining in Utah, ed. Colleen Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006), 230–35; John S. McCormick and John R. Sillito, A History of Utah Radicalism: Startling, Socialistic, and Decidedly Revolutionary (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2011), 141–43; Philip J. Mellinger, Race and Labor in Western Copper: The Fight for Equality, 1896–1918 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995); Charles Caldwell Hawley, A Kennecott Story: Three Mines, Four Men, and One Hundred Years, 1897–1997 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2014), 116–21; and Jeffrey D. Nichols, “The Fall of Leonidas Skliris, ‘Czar of the Greeks,’” History To Go, accessed August 15, 2019, historytogo.utah.gov /greek-czar/.

4 Beatrice Spendlove, “A History of Bingham Canyon, Utah” (Master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1937), 114.

5 Salt Lake Tribune, July 6, 1947.

6 U.S., Bureau of the Census, “10th Census, 1880, Utah,” Bingham Canyon (MS schedules, Microfilm File, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City).

7 Bingham Press Bulletin, December 30, 1922.

8 Utah Works Projects Administration, Utah: A Guide to the State (New York, 1945), 318.

9 Spendlove, “Bingham Canyon,” 101.

10 Bingham Press Bulletin, December 30, 1922.

11 Helen Zeese Papanikolas, “The Greeks of Carbon County,” Utah Historical Quarterly, XXII (April, 1954), 143–64.

12 Spendlove, “Bingham Canyon,” 112.

13 WPA, Utah Guide, 318.

14 Thomas Arthur Rickard, The Utah Copper Enterprise (San Francisco, 1919), 41.

15 Spendlove, “Bingham Canyon,” 129–34.

16 State of Utah, Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, First Report of the State Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics For the Years 1911–1912 (Salt Lake City, 1913), 31.

17 Personal interview, January 17, 1964.

18 Unless otherwise noted information regarding the strike was obtained from the following men who were either strikers at Murray or Bingham in 1912 or closely associated with the strikers: Spiro Stratis (Stratopoulos), Gus Delis, Nick Latsinos, George Papanikolas, Ernest Benardis, and Zack Tallas. Mr. P. S. Marthakis, Salt Lake City mathematics teacher for 41 years and state legislator for 10 years, was instrumental in obtaining some of these interviews.

19 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 31.

20 Thomas Burgess, Greeks in America (Boston, 1913), 165. 21 Tribune, September 20, 1912.

22 The word padrone meaning patron or master came from the Italians who initiated the system in America.

23 S. Frank Miyamoto, “The Japanese Minority in the Pacific Northwest,” Pacific Northwest Review, LIV (October, 1963), 143–49.

24 Information from Walter Bolic from the reminiscences of his father, Nick Bolic, Croatian immigrant and longtime resident of Bingham.

25 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 30.

26 Tribune, September 20, 1912.

27 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 31.

28 Tribune, September 18, 1912.

29 Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City), September 18, 1912.

30 Tribune, September 18, 1912; WPA, Utah Guide, 320.

31 Tribune, September 18, 1912.

32 Deseret Evening News, September 17, 1912.

33 Ibid., September 18, 1912.

34 Tribune, September 18, 1912.

35 Deseret Evening News, September 17, 1912.

36 Ibid., September 18, 1912.

37 Tribune, September 19, 1912.

38 Deseret Evening News, September 19, 1912.

39 Tribune, September 19, 1912.

40 Salt Lake Herald Republican, September 19, 1912.

41 Tribune, Deseret Evening News, and Herald Republican, September 20, 1912.

42 Ibid.

43 State of Utah, Governors’ Papers (William H. Spry [1909–1916]), correspondence files. The Governors’ Papers are in the Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City. Signatures of Greek miners and the fees they paid Skliris were collected in a notebook by Louis Theos.

44 Herald Republican, September 20, 1912.

45 Tribune, September 19, 1912.

46 Deseret Evening News, September 19, 1912.

47 Ibid.

48 Herald Republican, September 20, 1912. The extremely frugal habits of the immigrants that enabled them to help their impoverished families and provide dowries for their sisters in their native lands was a vital aim of Mediterraneans that Americans were incapable of understanding. In his report to the Department of Commerce, the government immigrant inspector gave the following information on drafts and money orders sent to foreign countries. Bingham Canyon postoffice: $295,751.56Citizens State Bank of Bingham: $121,499. 87Bingham State Bank: $142,839.59Victor Anselmo, Italian storekeeper: $21,028.00 The report continued: “Besides the foregoing there was a good deal of money sent through the Salt Lake banks and postoffices and a number of miners have safety deposits containing gold and silver and many others carry gold and paper money in belts around their waists. According to the bankers of Bingham Canyon, only about thirty per cent of the money paid out by the mining companies remains in Bingham Canyon.” (Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 31–32.)

49 Tribune, September 19, 1912.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid., September 20, 1912.

52 Ibid.

53 Herald Republican, September 20, 1912.

54 Deseret Evening News, September 20, 1912.

55 Herald Republican, September 20, 1912.

56 Deseret Evening News, October 11, 12, 22, 26, November 9, 1912; Tribune, October 18, 1912.

57 Tribune, September 21, 1912.

58 Frank Stuenenberg, governor of Idaho (1897–1901), was killed by a bomb in 1905 during mine labor troubles. The court case won renown because of the lawyers— William E. Borah represented the state and Clarence Darrow the accused.

59 Deseret Evening News, September 22, 1912.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid., September 24, 1912.

62 Herald Republican, September 24, 1912. 63 Deseret Evening News, September 27, 1912. 64 Tribune, September 26, 1912.

65 Ibid., September 28, 1912.

66 Ibid., October 2, 1912.

67 Ibid., October 5, 1912.

68 Deseret Evening News, October 5, 9, 10, 1912.

69 Tribune, October 12, 1912; Deseret Evening News, October 11, 1912.

70 Deseret Evening News, October 12, 1912.

71 Ibid., October 14, 15, November 2, 14, 1912.

72 Ibid., October 7, 14, 1912.

73 Tribune, October 18, 1912

74 Deseret Evening News, October 25, 1912.

75 Ibid., October 26, November 4, 12, 13, 14, 1912.

76 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 30–31.

77 Tribune, October 31, 1912.

78 Deseret Evening News, October 23, 1912.

79 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report . . . 1911–1912, 31.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid., 33.

82 Rickard, Utah Copper Enterprise. Raphael Lopez was a lessee in the Apex Mine. He was put in jail for a short time for “knocking down two Greeks molesting girls.” The sheriff, misinterpreting the situation, was said to have pistol whipped him. This, according to the Bingham Standard, resulted in legendary hate for the law. On November 21, 1913, Lopez shot Juan Valdez, who was found dead with a knife in his hand. Quarrel over Mexican politics was believed to be the reason by some, but the motive was never positively established. After the shooting Lopez armed himself with a rifle and cartridges and left Bingham. A posse followed his tracks in the fresh snow to a ranch near Utah Lake. Lopez started firing and killed three of the four officers. Other posses arrived but found no trace of Lopez. On November 26 Lopez returned to Bingham and went to the house of a friend, Mike Stefano. There he gathered food, clothing, a rifle, and 40 rounds of ammunition. Stefano informed the police who traced Lopez to the entrance of the Apex Mine. Although trapped, Lopez had the advantage of being familiar with the miles of tunnels and pillars that could hide him. Work at the mine was stopped, putting 200 men out of work. Guards were doubled and outlets sealed. Four men took a bale of hay inside and set it on fire in an attempt to smoke out Lopez. Three shots echoed in the tunnel killing one man and injuring another. A posse charged the mine, Lopez fired on it and disappeared deeper into the mine. On the 1st of December, lump sulphur, damp gunpowder, and cayenne pepper were lighted near the mine entrance, and the fires kept going for five days. On December 15th the mine was ransacked. All that was found was Stefano’s blanket. John J. Creedon, “Down Memory Lane,” Bingham Press Bulletin, November 22, December 6, 13, 1963, January 3, 10, 17, 1964, believes the mystery has been overly romanticized. Lopez knew the labyrinth of the mine well, and there were several openings by which he could have escaped.

83 Bureau of Immigration, Labor and Statistics, Report. . . 1915–1916, 17.

84 Spendlove, “Bingham Canyon,” 73–74.

85 Spendlove, “Bingham Canyon,” 112.

86 State of Utah, Industrial Commission, Report of the Industrial Commission of Utah [1920–1922] (Salt Lake City, [1923]), 938.

87 Bingham News, December 30, 1922.

88 Ibid.

89 Ibid., April 28, 1923.

90 Papanikolas, “Greeks of Carbon County,” U.H.Q., XXII, 159–62.

91 Bingham Bulletin, May 3, 1928.

92 For examples, see ibid., December 18, 1930, March 12, August 27, September 17, 1931, November 3, 1932.

93 Tribune, November 15, 1936.

94 Ibid., January 8, 1950.

95 Personal interview with Miss Vern Baer.

For complete tables please view this article on a desktop.