47 minute read

Ogden’s Forgotten City Hospital

Ogden’s Forgotten City Hospital

BY JOHN GRIMA

Speaking before the Ogden, Utah, city council in November 1889, Dr. H. J. Powers, the official city physician, presented a dramatic description of how he and another doctor had recently performed “a very delicate surgical operation upon a ward of the City which was of such importance that death would have soon resulted if he had not been treated promptly. This operation was made . . . under the most unfavorable of circumstances as there was no fire in his room and no one to leave with him.” 1 The need for adequate, publicly available medical facilities—rather than the hotels and rooming houses often used—would only become greater, he said, for “accidents, sickness, and pauperism are increasing in proportion to our rapid population growth.” Powers’s hope was to persuade the council to create a new entity, Ogden City Hospital, and his hope was soon to be realized.

Ogden City Hospital was Ogden’s first acute care hospital. Also known as Ogden General and Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital, it was the second largest hospital in Utah Territory when built in 1892 and the only one sponsored by a local governmental entity. The hospital grew out of the ambition of the city’s business and political leaders to assert Ogden’s importance within the area’s growing railroad economy and a desire on the part of the city’s physicians for a facility in which to care for patients. The hospital is particularly significant because of Ogden City’s role in its founding and in its initial years of operation. It was built with public funds, bonded for by the city, and, during its first five years, operated as a part of the city’s budget

This hospital is mostly forgotten today. Those who are aware of it mistakenly describe it as having closed almost immediately after opening, a victim of city retrenchments during the Panic of 1893. 2 One writer dismisses it as not a real hospital, a designation he reserved for the coming of the Dee Memorial Hospital in 1911. 3 In fact, Ogden City Hospital arose at a time of particular civic ambition, and, after some initial setbacks that did not include closing, it served the community as a valued resource until its replacement in 1911.

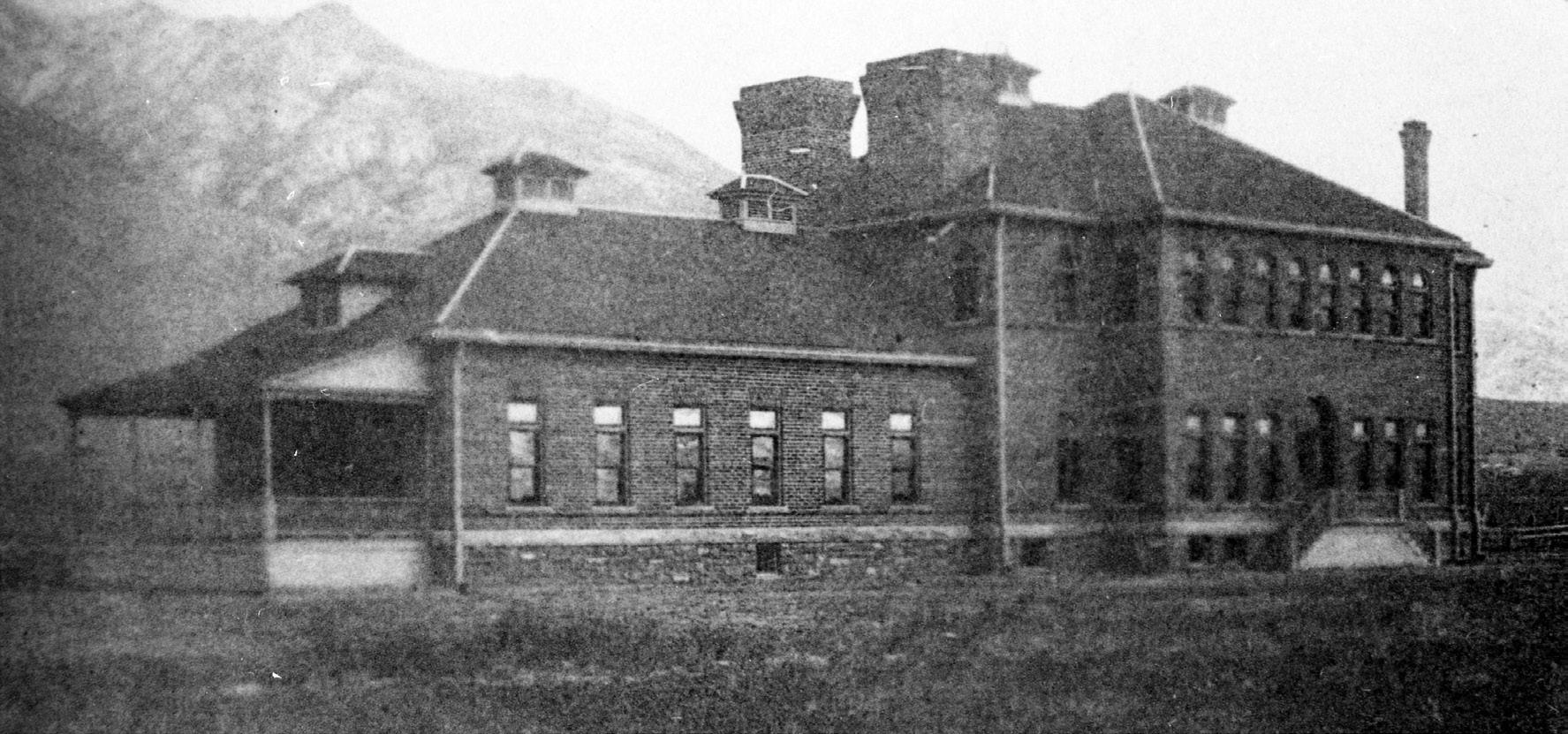

Ogden City Hospital was an acute care facility built and operated by the city of Ogden, Utah, that opened in 1892. The hospital is seen here soon after its completion. Ogden Union Station Museums.

Two facilities served as precursors to this hospital. Prior to its creation, the city had experimented with what was alternately called a hospital and a pest house. Ogden built it in 1882 on land well south of the city limits on a bluff above a stream, Burch Creek. 4 Mayor Lester Herrick described the primary motivation as “the necessity of having a hospital of suitable capacity and with the needed conveniences for the care and treatment of indigent persons, who by misfortune become objects of public charity.” 5

The immediate stimulus came about in the summer of 1882, when the mayor argued that a growing number of railway workers—lowwage, single men without family support—had increased the need for such care. However, the examples presented at council meetings concerned local people. One was a child who had fallen under a railroad car in the coal yards of the city; the child’s leg was crushed, requiring amputation. The railroad physician had attended to the child but would not continue care unless he was paid. The council was asked to accept the child as “an object of public charity,” pay the doctor, and pay for what further attendance the child required. Another case concerned a local man with severe frost bite of his feet and hands. “He was a poor man and had no relations to care for him.” He too needed amputations. The mayor asked the council to approve his placement at the Globe Hotel, where surgery could be performed, and to provide for the cost of the surgery, the hotel, and an attendant to continue care. Another person had a smashed foot, requiring another amputation. 6 Other cases involved persons in the early stages of potentially serious contagious diseases: smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever. All involved special arrangements for lodging and board—in hotels and rooming houses or in tents on the outskirts of town—and basic, custodial nursing care.

Neither the mayor nor the council challenged that the city was obliged to intervene in these “object of public charity” situations. What concerned them were the costs; they worried about being scammed by patients, their families, and other communities that might take advantage of Ogden’s largesse. They did not debate the city’s responsibility, but they wanted to limit its cost. 7

The decision to build the pest house came soon after the mayor moved a smallpox patient to an impromptu quarantine area south of the city, in the summer of 1882. 8 The city had begun a project for a new city hall and a jail, which did not at the time include a hospital. They intended to finance the new construction through the sale of city-owned land in the heart of the business district. 9 This plan stalled and with it progress on the city hall, but funding was available to start the jail, and the hospital, which had been under study, was authorized at the same time. The same contractor built both buildings. One gets a sense of the relative scope and importance of the two from the time and dollars expended on each: the jail took eight months and cost around $11,000; the hospital took one month and cost $2,000. 10

The contractor completed the building near the end of 1882, and the first patients were admitted in early 1883. 11 The six-room, rectangular structure had one room at each end and four rooms off of a central hallway, a kitchen, a storeroom, and four rooms for residents. There was no central heat, but expense records show purchases of coal, so there were coal stoves. The pest house had no plumbing and no connection to city water. Bathroom functions would have been served by an outhouse, water pumped and carried from a well or brought to the building from the creek. The roof blew off in severe windstorms. 12

Most patients fell under the charge of the city, although a few turned out to be the responsibility of the county. The doctor who attended to pest house patients—to the extent that a physician attended to them—would have been the city or county physician, officials whose duties included care for the indigent and who had the power to order confinement for reasons of public safety. Very rarely, private or railroad physicians sent patients to the pest house, people who could not be properly quarantined at home, all poor people. The conditions mentioned included pneumonia, measles, spinal concussion, delirium tremens, smallpox, recovery from amputations, and, in at least one case, pregnancy. 13 Smallpox patients, in some instances, did not stay in the building but rather in tents placed in “a hollow nearby.” 14 Persons who died from smallpox were buried in a nearby cemetery, as were individuals who died at home of smallpox. 15

While no record exists of opposition in 1882 to the pest house, an attempt to build a replacement in the 1910s generated resistance from people living in the area. 16 The facility very likely frightened the public. It became the subject of ghost stories, especially with an 1891 run of newspaper articles that told of hauntings at the hospital, at which time “the Pest House Ghost” became a motif in local advertising. 17

Lorenzo Waldram, together with his wife, acted as steward and operated the facility under a lease. This involved no rental payment; the city provided the facility for free and retained the obligation to fund repairs and improvements; the Waldrams agreed to care for consigned patients for a fixed daily rate. The arrangement served to insulate the city from the costs that came from caring for indigent patients in doctors’ offices, hotels, and rooming houses, with privately contracted caregivers. The fact of a pest house might also have acted in a subtle way to reduce demand for assistance from marginally poor people, who would have to accept humiliation and risk of confinement as a condition of receiving support. 18 The lease arrangement also ensured that the city would not have to pay staff when the facility had few inmates; the stewards accepted that risk.

The financial model appears to have failed from the start. The pest house’s census was often too low to generate any revenue for the stewards, who soon sought a salary and reimbursement for the operating expenses that were to have been covered by the daily rate. 19 The city made an appeal for public philanthropy to help defer the costs of the new service. It also sought support and financial participation from the railroads. 20 These efforts did not succeed. There was talk of approaching Weber County for support, but the county had a similar service at its poor farm. 21

Within a short time, the city council members were questioning their judgment in establishing the service. They mistrusted the stewards, worrying that they accepted patients too liberally and were not frugal with board and supplies. They worried that neighboring communities were sending their indigent sick to Ogden. 22 In October 1885, Ogden City abruptly closed the pest house, evicted the stewards, and terminated the lease. The city council publicly stated that the need had passed and that the hospital had become too expensive to maintain. A new territorial law then under discussion, which assigned counties responsibility for care of the indigent sick, seems also to have influenced the city’s decision. 23

The chatter about a ghost at Ogden City’s pest house in the late spring of 1891 prompted a local shop to use the brouhaha in its advertising. The pest house came to be when the city decided to run its own facility instead of making piecemeal payments when assisting sick and indigent persons. Ogden Daily Standard, June 3, 1891, page 6.

Ogden retained the building as a municipal asset and eventually rented it for residential use, prior to bringing it back into service for quarantine in the fall of 1900. 24 The reopening again occasioned conflict between Ogden City and Weber County over care of the poor, especially transients without established city or county residence. In 1902, the city took the county to court over Weber’s refusal to pay for such a patient. A local judge ruled in favor of the county. The city appealed to the new State Supreme Court and won. 25 The resolution seems to have led to more productive discussions, and in 1906 an agreement was concluded in which the county took over operation of the pest house on a no-rent lease with the city. It remained in operation as a county service until 1914. 26

A facility owned and operated by the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) served as the second important precursor to Ogden City Hospital. In 1883 the railroad purchased a building on the corner of Eighth and Spring streets, near the southern edge of Ogden, and converted it to hospital use. 27 Prior to that time, the UP had paid for services at facilities maintained or overseen by its locally contracted physicians, sometimes in the physicians’ offices, sometimes in rooming houses and hotels. One such doctor was T. E. Mitchell, whom the newspapers frequently described as the railroad physician, sometimes referring to his offices as the railroad’s hospital. 28

The railroad had established a hospital fund based on an employee payroll deduction in 1882, which likely supported the building’s purchase. 29 The judgment that the company would be better off providing hospital services to employees itself rather than purchasing them piecemeal from others—the same judgment that led to the creation of Ogden’s pest house—probably motivated the railroad. The building, which had previously served as a dance hall, was fairly large, with two floors and a basement, room for eight patient wards, a kitchen, a dining room, and an office. Surgery would have been performed in the wards. From 1887 to 1888, a contingent of Sisters of the Holy Cross briefly staffed the hospital, the same group that sponsored Salt Lake City’s Holy Cross Hospital, before moving to Price to work with the mining communities there. The facility seems to have seen quite heavy use, with a census as high as twenty-five individuals and patients brought in from Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada. 30 In 1890, the railroad added a separate building adjacent to the old dance hall. Reports at the time mention improved systems for heat and water but do not discuss the building’s clinical functions. 31

The UP hospital served only railroad employees hospitalized for employment-related conditions and was staffed only by railroad-contracted physicians. Although the facility made occasional exceptions for nonemployee patients under the care of a contracted physician, it completely barred other physicians in the community. In this era, doctors still delivered most private medical care in the home or in their offices, even surgery, but the presence of a modern operating room—off limits at a time of a growing array of surgical procedures—would have highlighted for local physicians their lack thereof and been a factor in the developing perception that Ogden needed a public hospital. 32

The Union Pacific Railroad hospital. As this image shows, the building was configured with the raised porch that, in other hospitals of the time, was used for receiving patients delivered by a horse-drawn wagon. If that was the use of the hospital’s porch, then there were likely trauma facilities just beyond the entryway. Ogden Union Station Museums.

The hospital closed in 1896, a victim of the UP’s bankruptcy following the Panic of 1893. It remained in operation until mid-1896 while the courts sorted out the liquidation of the railroad’s assets. Union Pacific subsequently provided hospital services for its employees under contracts with Ogden City Hospital and its successors, a critical factor in the new hospital’s success. 33

By 1890, driven by the city’s centrality as a railroad hub, Ogden’s population had more than doubled from 6,069 (1880) to 14,889, much of the growth caused by in-migration of non-Mormons seeking work and opportunity. 34 These demographics increased anti-Mormon sentiments in local politics, and—aided by the candidate and voter eligibility provisions of the Edmunds and Edmunds-Tucker acts of 1882 and 1887—resulted in the election of a non-Mormon Liberal Party mayor and city council in 1889. 35 The new mayor, Fred Kiesel, a founding member of the new and ecumenical chamber of commerce, championed Ogden and advocated for the separation of church and state rather than vociferously attacking Latter-day Saints. His ambitions for Ogden seem to have been widely shared. The projects of the next several years indicate that there was a broad community consensus that Ogden’s time had come—that the city should no longer cede leadership to Salt Lake City, that it should build for itself a place as the leading railroad hub in the Intermountain West. Kiesel himself imagined that Ogden might become the capital after statehood. 36

The previous administration had expanded the city’s bonding capacity from $50,000 to $150,000 and initiated design for the previously delayed city hall and a new fire station. 37 The city hall building, constructed from 1889 to 1890, expressed well Ogden’s sense of itself at the time. An ornate Second Empire–style structure, it housed Ogden’s municipal offices and, eventually, its public library. 38 The next construction item for the new administration, after the completion of the City Hall and fire station, was a hospital. No evidence exists that Kiesel and the city council had included a hospital in their campaigns, and reports of the mayor’s victory comments do not mention one. 39 But at a council meeting in October 1889, the mayor asserted the need for a hospital. He linked that need to the question of transient and indigent people, echoing the arguments for the pest house ten years earlier, but more forcefully to what he called Ogden’s “metropolitan” status. 40

Frederick J. Kiesel, a prominent Ogden businessman who became the city’s first non-Mormon mayor in 1889. Utah State Historical Society, photo 12774.

The role of hospitals in American cities at the end of the nineteenth century was in transition. They still retained an association as end-of-hope institutions, places where people were sent for the safety of their neighbors and where those too ill and too poor went to be out of sight while dying. But hospitals also symbolized modernity, municipal and philanthropic investment, and civic success. There had been real advances in

the possibilities of medical care that were now expressed in hospitals: aseptic surgical procedures, stand-alone operating rooms, and an evolved standard of nursing care. They were no longer considered appropriate for quarantine; in Ogden, the new civic hospital screened out patients with contagious diseases, diverting them instead to tents on the lawn, a “detention hospital” at the jail, or the city pest house after it reopened. 41 Hospitals had also become important as aggregation facilities and workshops for physicians. Facilitated by transportation changes that made it more efficient for patients to come to central locations for care, hospitals allowed doctors to group their sicker patients for trained oversight with room and board, specialized surgical facilities, and proximate stocks of drugs and supplies. 42 H. G. Powers, the city physician, clearly articulated this “physician workshop” perspective in arguments he presented to the city council in November 1889: “In constructing a hospital,” Powers noted, the chief consideration was “the work to be done in them; that is how to get the sick well in the greatest numbers and with reasonable comfort.” 43

The new hospital began in a preemptive way— without publicly reported discussion, approved by the city council after the fact—with the rental of a suite of rooms at Twenty-Fifth and Grant in downtown Ogden in January 1890. 44 The city, acting through City Physician Powers, hired a steward and arranged for food service, soon using the same vendor who supplied the jail. They arranged laundry and cleaning services; and acquired domestic and hospital supplies, along with stethoscopes, thermometers, and specialty items for surgery. The city paid all expenses, and the steward was an employee, not a contractor. 45 While never precisely declared such, this was a municipal hospital.

The old concerns about moral hazard and abuse of the city’s generosity emerged immediately. The council suspected that other cities were sending their patients to Ogden and that individuals were feigning poverty in order to avoid having to pay for care. In response, the sanitary committee developed a set of rules for the management of the facility. These required that the committee review charity admissions and that payment plans be set up after discharge for those who could return to work. There was an optimistic sense that these measures would work, that through them the city could control the financial risks that having such a hospital created. 46

The opening page of “Rules and Regulations of the Ogden City Hospital,” dating from the early 1890s. This document illustrates the municipal character of the new hospital, as well as its welcome stance to qualified physicians. Courtesy of Utah State Archives and Records Service, Series 5321, document 5245.

A year-and-a-half later, in the summer of 1891, having looked at and rejected a few existing buildings that might serve as a home for the hospital, the city council authorized the issuance of bonds and initiated a formal search for property for a new facility. They announced a competition for plans, open only to local architects, and they very quickly purchased a site, accepted a design, and awarded a contract for construction—again considering only local firms. By October 1891, the new hospital was under construction. 47

George A. d’Hemecourt, an architect who had worked for the city as a building inspector and advisor, was the designer. 48 It was a vertically aligned building with two wings, both with a basement, the second largest acute care hospital in the state at the time, built to accommodate fifty beds. Only the new Holy Cross Hospital in Salt Lake, completed in 1882, was larger. 49 The design included the possibility of a second building placed parallel to the first, suggesting that it was planned to accommodate expansion. The hospital’s built and planned sizes speak to the ambitions of the city’s planners, while the haste and decision not to seek specialized architectural expertise show their inexperience and suggest they underestimated the complexity of such a project.

The building was of brick and stone and the cost of construction was expected to be about $40,000. The first floor housed an operating room, a pharmacy, surgeon’s quarters, patient wards, toilet rooms, and dining rooms. Private wards made up the second floor. The basement held a kitchen, another dining room, a storeroom, a fuel room and a furnace room. Sterilization was done in the basement, with instruments carried back and forth to the first floor. The building included a coal furnace and lined flues for the delivery of heat to the upper floors. It was said to be the first heating system of that type to be included in any building in Ogden. The city extended water to that portion of Twenty-Eighth Street in time with the hospital’s construction, so it had piped, pressurized water when it opened in June 1892. 50

Ogden elected a new mayor and council at the end of 1891 as the hospital was about to open. 51 The new administration returned to discussions about the moral hazard and risks of being taken advantage of by citizens, adjacent communities, and the railroads, which frequently denied payment for employees who were deemed to have contributed to their illness or injury. The council and the sanitary committee worked and reworked these issues, developing a final set of regulations that gained majority approval in May 1892 as the hospital opened. 52 With them, the council passed a resolution authorizing the mayor to “make such changes and hire such help” for the hospital “as he in his judgment may see fit,” essentially establishing the hospital as a department within city government. 53

These regulations focused on maintaining city control, preventing abuse of the city’s generosity, and paving the way for privately paying patients. They held, first of all, that the hospital fell under the supervision of the mayor, the city physician, and the chairman of the sanitary committee. The hospital would admit no one as a free patient without the approval of the city’s supervisors. The city physician, acting as such, would attend only to patients under city sponsorship, and he was to receive no additional compensation for that care. The facility was to be open to graduates of reputable medical colleges, after application to the supervisors. Such physicians would set and collect their own fees, but their patients must pay in advance for their board and care. The rules noted that the object of this latter provision was “to make the Hospital self-supporting, as nearly as possible.” Mirroring the practice of the railroads but without dipping into wages, the city council allowed free admission for city employees who became ill in the performance of their duties, so long as the illness was not due to negligence. 54

The new hospital opened with a grand reception and praise from the local press. The newspaper lauded it as a symbol of Ogden’s progress, an echo of the sentiment that had motivated Mayor Kiesel and his colleagues to propose it and one comparable to the laurels other western newspapers heaped on their cities when a major building opened. Here was an institution asserted to be the equal of hospitals throughout the region, another sign of Ogden’s coming into its own. Carriages took the city leaders and other guests for tours and lunch, and “everything was found to be in splendid shape.” 55

Despite the hoopla, Ogden City Hospital launched with difficulty. There were design errors. The original plans had omitted electricity and lighting, which the council authorized in June 1892, just before opening. 56 No sewer ran to the site, and the cesspool—an underground arrangement for the collection and filtering of waste—failed and had to be replaced. 57 A Territorial Circuit Court judge, apparently acting in regards to a regular inspection of custodial institutions, found fault with the sanitation, the flooring, and pipe sizes with respect to fire safety. His report carried the authority to require corrections. 58 The hospital was located on the southeastern edge of town, and there was an initial problem with pigs on the site. 59

The Ogden Standard soon began printing stories about a low number of hospital patients, while other stories encouraged citizens to see the facility as safer than home for recovering from illness. 60 These latter articles read as placements by the hospital’s sponsors or attempts on the part of the newspaper, acting as a civic promoter, to boost the hospital’s image. They suggest that Ogden City Hospital was not succeeding in its goal of attracting privately paying patients.

The long economic expansion that had carried Ogden through the end of the 1880s ended abruptly in May and June 1893 with the nationwide Panic of 1893. The stock market crashed, a large number of banks and businesses failed, and, not least for Ogden, the Union Pacific Railroad went into receivership. 61 The city’s revenues declined and with them the city council’s confidence that it could maintain a hospital. At a July 1893 meeting, one month into the downturn and cheered on by local editorial writers, the council called for a broad set of budgetary retrenchments, including the closing of the hospital. It passed those cuts, which then went to Mayor Robert Lundy for final approval. He vetoed them along with the hospital closing, and his veto was sustained at a subsequent meeting. 62 Nevertheless, while the hospital had survived and stayed open, the glow was off.

Writers who have described Ogden City Hospital as closed between 1893 and 1897 might miss the veto and reversal of the council’s vote. 63 The way that the Ogden Standard reported the story obscures those events. The newspaper published several articles and editorials about budget retrenchment and the possible closure of the hospital but provided only limited coverage of the mayor’s 1893 veto and the failure to override it. It is clear, however, that the hospital continued to operate in the ensuing months and to be an expense item for the City and a subject of ongoing news. 64

The city council, meanwhile, continued to be split in its opinion, and that split next evolved into a dispute over the nature of the hospital’s financial relationship with the city. Within twelve months, in the summer of 1894, with the Ogden Standard’s editorial page still calling for closure, a majority of councilmen agreed that they preferred a lease arrangement like that with the old pest house in which a lessee would operate the hospital in return for accepting city-sponsored patients at a predetermined, negotiated rate—effectively shifting the financial risk of operations to the lessee. 65 The proposal divided the city administration, with the next new mayor, Charles M. Brough, and the members of the sanitary committee seeking to retain the municipal service model. Part of the community weighed in with a rare expression of progressive sentiment through a petition from the Ladies Charitable Association that opposed leasing “to the lowest bidder.” 66 The petitioners argued that doing so went “against public policy” and asserted that “no community is too poor but what it cannot properly take care of its sick.” More than one hundred individuals, including a number of the city’s physicians, signed the petition. 67

Mayor Brough and his allies eventually prevented the city council from awarding a lease to its preferred candidate and gained the council’s concession that, leased or not, the hospital would remain under the supervision of the city, the sanitary committee, and its officers. 68 However, the council prevailed on the larger issue: Ogden City awarded a contract to Frank Sherwood, its current hospital steward, whose status then changed to contractor. 69 Sherwood pledged a $1,000 bond; the term was to be eighteen months, expiring on February 1, 1896. The lease included the hospital, its furnishings, and the existing easements. He was responsible for heat, light, and the cost for all patients whom the city might consign there. 70 The city physician retained the responsibility to care for city patients, and the city government continued to support the hospital by paying expenses such as fire insurance premiums and needed property improvements. In this way, it continued to subsidize the institution. Yet the change to a lease agreement marked the end of the full municipal hospital model for Ogden City. It had existed for not quite five years. The city maintained its governance role, and it continued to provide the building and subsidies without seeking a return on investment, but it was no longer responsible for the cost of operations.

Even with the new model, the Standard and some councilmen continued to call for Ogden City Hospital’s closure throughout Sherwood’s term. 71 An 1895 law anticipating statehood repeated the ambiguously worded provisions of the 1888 territorial law that assigned counties responsibility for the care of the indigent. 72 This led to a round of proposals about whether the city or the county should own the hospital and which entity should be first in line to pay for certain patients, which in turn fed into arguments about closure and possible transfer to Weber County. 73 But the hospital did not close; it did not become a county entity. Rather, the institution persevered through Sherwood’s eighteen-month lease and then through another year of discussion about what should happen, as the economy improved and the Union Pacific bankruptcy worked its way through the courts. Upon leaving office at the end of 1895, Brough persisted in his opinion that the city had a duty to maintain a hospital, in the interests of both “suffering humanity” and “municipal economy.” 74

Little in the extant records tells us about hospital operations during the term of Sherwood’s lease. The cesspool project was completed, but one does not see other improvements. One gets the sense that the years during the economic downturn were ones of minimal growth and not a lot of use; it might not have been much of a hospital, not in the sense of equipment, staffing, and amenities. Nevertheless, when the lease came up for renewal in 1896, a number of individuals and groups came forward to bid, seeing Ogden City Hospital as a viable business opportunity, and this time the bidders came mostly from the ranks of “qualified physicians” rather than from nonphysician generalists like Sherwood. 75

The successors emerged in the fall of 1896, a group of five doctors that included two past city and county physicians, a future mayor, and the physician for some of the community’s wealthiest families. The group incorporated itself as the Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital Corporation (OMSH), an approach that allowed its members to protect their individual business and family wealth from any losses the hospital might incur. It was this entity that would now manage the hospital. A lease proposal dated September 7, 1896, indicates the applicants would lease the city hospital and its equipment for no less than two years, paying the city on an annual basis. 76 While there is no mention of a set price for city-sponsored patients and no explicit commitment to accept such patients, the hospital continued to accept those patients and bill the city for them.

An advertisement for Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital, also known as Ogden General Hospital, that appeared in the local newspaper on a reoccurring basis in 1897 and 1898. Ogden Daily Standard, April 27, 1897, p. 8.

Newspapers in Ogden and Salt Lake City took notice. The Salt Lake Tribune called it “a step forward” and said that the hospital deserved success. The Standard completely reversed its previous opposition. Now the hospital was “something that was urgently needed” that would be “of material advantage to the city.” The newspaper praised the doctors’ medical ability and competence, stated (probably prematurely) that the building had been “thoroughly renovated,” and predicted economic benefits for the city’s merchants. 77

This time, circumstances were more favorable. A key factor resulted from the 1893 railroad bankruptcies. The Union Pacific’s hospital had remained in operation, but its two buildings had been among the assets seized by the court to pay shareholders and creditors. Those buildings finally went out of service around mid- 1896. Railroad groups talked about starting a new hospital to replace the one lost to liquidation but those ideas never took off, and OMSH ended up as the contractor for hospital services to Union Pacific’s large base of employees with their reliable funding source. 78 By March 1897, the county had also agreed to a contract with the hospital corporation. 79 The new lessees petitioned Ogden City Council for a remission of their first year’s rent, arguing that the facility was in poor shape, and promised to invest an equal or greater amount in improvements. The council granted their petition, as it did with similar petitions in subsequent years. 80 Finally, as the area’s population grew and the number of “qualified physicians” in the community increased, it had become much more likely that private patients would in fact be served at the hospital. 81

The corporation promoted the enterprise extensively in newspaper advertisements, attempting to create a public perception of itself as technically competent, safe, and comfortable. An ad ran every other day or so in the Standard Examiner, well over 150 times, between April 1897 and the end of 1898. It addressed the lay public and physicians, noting that “the hospital is open to all reputable physicians who may desire its superior advantages for their patients.” The timing of the new financial model, near the end of the 1890s, fits neatly with a broader trend in American medicine when improvements in surgical practice increased the opportunity for paying patients and fed the growth of hospitals. 82 By mid-1899, the newspaper was reporting that the hospital—now alternately referred to as Ogden General—had installed a host of improvements, including a button-operated nurse-call system, operating rooms with marble slabs, and a complete dispensary. 83 One begins to see mention of named, nonindigent patients—even the occasional city councilman or his family members— cared for at the hospital, often for abdominal or orthopedic surgery. This suggests that the hospital had become acceptable to the middle and governing classes. Further, the Standard praised individual physicians by name and lauded their surgical successes. 84

Other developments indicate the increasingly professional nature of OMSH. The hospital hired a new chief nurse (or matron), a woman with hospital experience from Milwaukee, as well as nursing, laundry, and maintenance staff. 85 Ambulance service was initiated, and in 1906 Ogden City gave ambulances priority right-of-way on its streets. 86 The hospital became the beneficiary of charity on the part of the Elks Club and local women’s societies, and itself contributed to San Francisco earthquake relief in 1906. 87 Significantly, patients came from Davis and Box Elder counties, Idaho, and Wyoming for hospital care, hinting at a geographic service area not unlike that of Ogden’s present-day hospitals.

The city renewed the OMSH lease at the end of 1900 for ten years on terms similar to what had been in effect since 1897. Under it, the corporation owed the city a more than nominal amount for rent, but payment could continue to come in the form of improvements and equipment. 88 By the end of the lease period, after 1907 or so, disputes arose whether the OMSH physicians were meeting these obligations, but even then, the arrangement between the city and the hospital appears to have been quite stable. The city continued to employ a city physician, and it continued to make occasional payments to the hospital for the poor. It paid for fire insurance and for a connection to a newly extended city sewer system, and it continued to contribute the use of its building without a return on capital, while the corporation paid the expenses of operating the facility and employing its staff.

After 1905, while the city continued to depict the hospital as a proud community accomplishment, signs of strain in the relationship began to appear. 89 The Southern Pacific railroad developed a trauma station in the Ogden railyards, clearly with the intention of reducing costs; and although the county and the railroads continued to contract with Ogden General, a renewed sensitivity to costs on the part of purchasers was evident. 90 Accounts emerged about the hospital turning away patients at its doors because they lacked proof that they could pay for services. One particularly lurid story concerning a quack doctor, the Boy Phenomenal, Earl S. Beers, who was engaged in an affair with the wife of a merchant, seems to have stuck in the mind of editorial writers. 91 The local press complained about access to information for hospitalized patients. 92

By mid-1906, as houses began filling in the area around the hospital, the city council expressed concern that the level of investment OMSH had made pursuant to its lease obligations did not equal the rents the city had forgiven. The council twice voted to put the hospital up for sale and announced that it was accepting bids. 93 The lease remained in place and no sale occurred, but discussions began about creating a replacement facility.

The motivation for a new hospital apparently arose out of a sense that the community needed something better, both architecturally and organizationally. Newspapers were full of stories of the wonders about modern medicine as performed in hospitals, and new ones emerging elsewhere in the country now served as aspirational models for Ogden. 94 The major organizational shortcoming people saw in the existing model was the inability to accept unsponsored patients of limited means, a variant of the free-rider concerns that the city had faced prior to the OMSH era. Ogden General had dealt with this problem in much the same way that the city had in its 1892 hospital regulations: by forbidding admission to patients who did not have sponsorship and who could not prove that they could pay for service. Yet there was embarrassment about turning away the sick and injured, and a community sentiment seems to have grown to support extending care to the poor. 95 They also wanted to make medical care more generally available, to extend its benefits to low and moderate income people by, for instance, encouraging the use of the hospital for routine childbirth. 96

A description and image of Ogden General Hospital, also known as Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital, published in 1901. Industrial Utah, no. 35, July 15, 1901.

The city’s elected leaders apparently joined these discussions, but only as individuals and representatives of one among several stakeholder groups with a common ambition. No newspaper record exists after 1898 of a publicly vetted suggestion that the city should build a new hospital, and by the time these discussions were in progress in 1908, the city seems to have fully retreated from the idea that it should be in that role. Instead the community had seized upon a model based on philanthropy as a potentially perfect solution. The hospital would be funded with private donations from the wealthy and run through a not-for-profit corporation that would earn enough from paying patients to support reinvestment and growth, with additional needs supplied through further philanthropy. Philanthropy, this time in the form of an endowment, would also provide a solution for funding care for the indigent. 97

Annie Taylor Dee was the philanthropic lead for the new facility, the Thomas D. Dee Memorial Hospital, which was named for her deceased husband. Community physicians led the planning and preparation for design. The result was a better researched and designed facility that was larger and better appointed. It was completed in late 1910 and opened on January 1, 1911, a little more than a year after the formal expiration of the last OMSH lease. The OMSH operated right up until the opening of the new hospital. The two facilities coordinated the transfer of patients, staff, supplies, medicine, and at least some equipment. The entire medical staff of the old hospital moved to the Dee Memorial. 98 The railroad contracts passed to the new hospital, and there was no payment for the “going concern” value of the business that OMSH and the city might have claimed for the self-sustaining hospital operations that they had developed over the past thirteen years. 99

The Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital Corporation dissolved at the end of 1911. The Twenty-Eighth Street building was offered for sale in September after the opening of the new hospital. One sees a suggestion that it be converted to a detention home but no serious proposals for purchase. 100 The site was eventually subdivided and broken up into residential lots. The first houses built on the land appeared around 1922, so one can be confident that Ogden General was demolished within ten years of its closing. 101

The Dee Memorial Hospital continues today as the Intermountain McKay-Dee Hospital. However, the organizational model under which it began life lasted only a few years. Revenue grew more slowly than planned; expenses and demand for charitable care did in fact exceed the resources of the trusts designated to fund them. This time, the solution did not come from Ogden City or from transferring risk to private contractors, but rather through the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its local congregations, an arrangement that persisted into the late 1970s and the formation of Intermountain Health Care. 102

In 1890, during an era of expansion and with an administration focused on an ambitious program of building and growth, Ogden City committed itself to a municipally funded, acute care hospital that first opened in rented quarters in the downtown area, serving mostly indigents. At the end of 1892, the city opened a new, fifty-bed hospital facility on land just east of the city center, intending it to serve both publicly and privately funded patients. At the time of its opening, Ogden City Hospital was the second-largest such hospital in Utah and the only one sponsored by a city or county. Both the temporary facility and the 1892 hospital were funded entirely by Ogden City; both functioned as municipal hospitals—operating units of Ogden City government, supervised by the mayor, city physician, and city council, with all funding flowing through the city budget.

The Panic of 1893 strained Ogden City finances and almost led to the closing of the new hospital. A mayoral veto of a council motion for closing was sustained, and the hospital persisted, but, after 1894, in an altered organizational form. The city retreated from maintaining the hospital as a municipal operation and turned to a lease model that transferred risk to a lessee, still retaining components of oversight and control and continuing to subsidize the hospital by funding facility improvements and expenses such as insurance and water. The first lessee was not a doctor, but after three years a newly constituted physician corporation, the Ogden Medical and Surgical Hospital Corporation, replaced him. The hospital under that organization, variously known as Ogden General, Ogden City Hospital, and Ogden Medical Surgical Hospital, succeeded as a private enterprise. It made use of public capital, served public and private patients, and was accepted by and integrated with the community around it.

OMSH controlled the hospital until 1911, when it closed and was effectively absorbed into the new Thomas D. Dee Memorial Hospital, itself the first attempt in Ogden to finance hospital care through private, not-for-profit philanthropy. With the end of Ogden General, public funding of hospitals through the city came to an end. Ogden City Hospital, eclipsed by its immediate and subsequent replacements and lacking a constituency that valued its memory, faded from public awareness.

Web Extra

Visit history.utah.gov for photographs of contemporary Utah hospitals.

Notes

I presented a version of this paper at the Ogden Medical Surgical Society Meeting, May 16–18, 2018, at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah. Kurt Rifleman and my Tuesday coffee group have helped it with important advice and encouragement. Kathryn MacKay and Holly George provided extensive and valuable suggestions about format and content. The staffs of the Utah State Archives and the Ogden City Recorder’s offices, the latter in a wonderfully detailed response to a Government Records Access and Management Act request, provided invaluable assistance in identifying sources and enabling me to access them. Without Utah Digital Newspapers, there would be no paper. Sunee Grima, my wife, discovered the photos of Ogden General in collections at Weber County Library and the Union Station Museum photo archive. My thanks to all of them. 1 “City Council,” Ogden Semi-Weekly Standard, November 13, 1889, 6.

2 Richard C. Roberts and Richard W. Sadler, A History of Weber County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Weber County Commission, 1997), 218; Joseph Morrell, “Hospitals Important Now, but Pioneers Had None Until 1882–83,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, December 11, 1955.

3 Joseph Morrell, “Hospitals,” and Utah’s Health and You: A History of Utah’s Public Health (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1956), 145. Morrell, whose work was for many years the only secondary source about Ogden hospitals, might be the source of the “it closed” error. Morrell worked for a time at Ogden General prior to its replacement in 1910, but he had no personal experience of the events of 1893.

4 The spelling is Burch Creek today, but it was Birch Creek in the relevant 1880s news stories.

5 Minutes, January 12, 1883, Ogden City Council, Council Minutes, 1880–1894, Series 5316 (hereafter Council Minutes), Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter USARS); Ogden Herald, January 30, 1883.

6 Council Minutes, January 20 (qtn.), June 16, August 1, 1882.

7 Over the next twenty years, Utah would write two laws and experience at least one State Supreme Court case dealing with city and county responsibility for the “indigent sick.”

8 Council Minutes, August 25, 1882.

9 Council Minutes, February 14, 1882. This plan would fail in its specifics and lead eventually to a round of bonding that would set the stage for the funding of the hospital to be built in 1892.

10 Council Minutes, multiple sessions, 1882; Ogden Herald, October 21, 1882.

11 Ogden Herald, December 18, 1882, January 30, 1883; Council Minutes.

12 Ogden Daily Standard, May 28, 30, 31, 1891. Two windstorm incidents occurred in the early 1900s.

13 Ogden Herald, March 27, September 4, 1883. Reports of patients cared for at the city hospital were a staple of Ogden newspapers from the 1880s to the 1900s. They provide the basis for observations in this paper about patient case types and demographics. See also James B. Allen, “The Development of County Government in the Territory of Utah, 1860–1896” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1956), 78–80, 155.

14 Ogden Daily Standard, June 2, 1891.

15 Ogden Daily Standard, January 2, 1901.

16 Ogden Daily Standard, June 1, 1915.

17 Jennifer Jones, “A Haunting at the Pest House,” November 2, 2017, and “History of Ogden’s Pest Houses,” February 15, 2016, The Dead History, accessed December 20, 2017, thedeadhistory.com; Ogden Daily Standard, June 3, 1891.

18 Paul Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry (New York: Basic Books, 1982), 150.

19 Ogden Herald, August 12, September 6, 1884.

20 Ogden Herald, January 29, 30, February 8, 1883.

21 Ogden Herald, September 6, 1884.

22 Ogden Herald, November 29, 1884, September 5, 19, October 3, 1885.

23 Allen, “Development of County Government,” 200; Ogden Herald, October 3, 31, November 2, 14, December 12, 1885, May 29, 1886, January 8, February 7, 1887.

24 Ogden Daily Standard, September 15, November 27, 1900.

25 Ogden Daily Standard, April 26, 1902, February 2, 3, 1903; Deseret Evening News, January 29, 1903; Salt Lake Herald, May 10, 1903; Salt Lake Telegram, January 25, 1905.

26 Ogden Standard, June 5, 1903, July 23, 1906; Jones, “A Pest House Haunting” and “History of Ogden’s Pest Houses.”

27 Ogden Herald, April 1, 1884. These streets subsequently became Twenty-Eighth and Adams.

28 Salt Lake Herald, April 18, July 4, 1882; Ogden Herald, January 3, 1883.

29 Ogden Herald, February 6, 1882.

30 Kathryn L. MacKay, “Sisters of Ogden’s Mount Benedict Monastery,” Utah Historical Quarterly 77, no. 3 (Summer 2009): 242–59; “At the Hospital,” Ogden Herald, December 7, 1887.

31 “The U. P. Hospital,” Ogden Daily Standard, February 18, 1891.

32 Starr, Social Transformation, 179; Charles E. Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America’s Hospital System (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987).

33 See below.

34 Riley Moore Moffatt, Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850–1990 (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1996), 308.

35 Richard C. Roberts and Richard W. Sadler, Ogden: Junction City (Northridge, CA: Windsor Publications, 1985); Roberts and Sadler, Weber County, 138–39.

36 Richard C. Roberts, “Friedrich Johann Kiesel, Ogden Business and Political Leader,” in Ogden, Utah: The First 150 Years, 1851–2001, Ogden Sesquicentennial Committee (Ogden: Ogden Sesquicentennial Committee, 2002).

37 See, for example, Council Minutes, October 20, 1888, March 8, 15, 1889. These projects and their financing are mentioned iteratively in city council meeting minutes and in occasional newspaper meeting summaries many times between 1882 and 1892 as they evolved.

38 Roberts and Sadler, Weber County, 300.

39 Salt Lake Herald, February 12, 1889.

40 Council Minutes, April 23, 1889; Ogden Semi-Weekly Standard, October 23, 1889.

41 Ogden Daily Standard, January 1, 1901, January 18, March 27, September 16, 1902, February 24, May 14, 1903, March 24, 1905.

42 Rosenberg, The Care of Strangers; Starr, Social Transformation.

43 Ogden Semi-Weekly Standard, November 13, 1889.

44 Council Minutes, November 22, 1889, January 17, 1890.

45 Council Minutes, January 1, February 14, June 6, September 26, 1890; Ogden Daily Standard, February 24, 1891.

46 Council Minutes, January 24, 1890; G. H. Jones, “1891 City Physician and Hospital Report,” February 18, 1892, Ogden City Recorder Correspondence, Series 5321, US- ARS (hereafter Recorder Correspondence).

47 Ogden Daily Standard, May 7, August 20, 25, September 9, 15, October 20, 1891.

48 George A. d’Hemecourt appears to have come to Ogden from New Orleans in the mid-1880s and stayed through the mid-1890s, after which he practiced in the San Diego area. Willam Ellsworth Smythe, History of San Diego, 1542–1908: An Account of the Rise and Progress of the Pioneer Settlement on the Pacific Coast of the United States (San Diego: The History Company, 1908), 533; Roulhac Toledano and Mary Louise Christovich, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. VI: Faubourg Tremé and the Bayou Road (Gretna, LA: Pelican, 1980), 179; George A d’Hemecourt, Utah Center for Architecture, accessed December 5, 2018, utahcfa.org/architect/george-a-dhemecourt.

49 Morrell, Utah’s Health, 145, reports a capacity of thirtyfive beds prior to 1910, with some wards functioning as private rooms. The only other hospital was St. Marks, built in 1874. Deseret Hospital, 1882–1890, had ceased operating when the Ogden hospital opened. The W. H. Groves’ L.D.S. Hospital would not open until 1905; the Salt Lake County Hospital not until 1912.

50 Ogden Daily Standard, August 20, 25, September 15, 1891; Morrell, Utah’s Health, 144–45.

51 Ogden Daily Standard, February 10, 1891.

52 Ogden Daily Standard, February 9, 23, May 17, June 1, 1892.

53 Ogden Daily Standard, May 24, 1892.

54 Council Minutes, file 5464.

55 Ogden Daily Standard, June 28, 1892.

56 Ogden Daily Standard, June 14, November 19, 1892.

57 Ogden Daily Standard, September 19, December 15, 1891, May 10, 1892.

58 Ogden Daily Standard, March 2, 1893. The Ogden Daily Standard, for several years, reported on the annual inspections of the reform school, the hospital, and the city and county jails conducted by this court. The reports read as if the court was acting on its own authority, but it also might have been directed by a territorial authority. It does not appear to have originated from a litigant or other sort of complaint. Ogden Daily Standard, March 2, December 10, 1893.

59 Ogden Daily Standard, July 29, 1892.

60 Ogden Daily Standard, September 20, 27, 29, 1892.

61 Ronald W. Walker, “The Panic of 1893,” Utah History Encyclopedia, accessed March 23, 2018, uen.org/utah _history_encyclopedia; Ogden Daily Standard, October 14, 1893.

62 Ogden Daily Standard, June 20, July 18, 22, 26, August 1, 1893

63 Roberts and Sadler, Weber County, 218; Morrell, Hospitals and Utah’s Health, 145.

64 See, for example, Ogden Daily Standard, July 23, August 2, November 2, 1893.

65 Ogden Daily Standard, January 16, March 8, May 1, 1894.

66 Few references to this group exist in extant records, with an exception in “The Charitable Association,” Ogden Daily Commercial, May 29, 1891. Many women’s groups existed at this time in Utah and America, often with ties to churches and with missions of personal and community uplift. See Ogden City Directory (Ogden: R. L. Polk, 1896), 29–30, for contemporary women’s organizations.

67 Council Minutes, box 23, files 7165, 7230.

68 Ogden Daily Standard, May 1, 28, 29, June 5, 9, 18, 29, 1894.

69 Ogden Daily Standard, July 31, 1894.

70 Ogden Daily Standard, July 31, August 21, December 18, 1894, May 7, 1895; Council Minutes, box 23, file 7389, file 7393. The agreed-upon price per patient, per day was reported to be $1.23 (the bid) and $.83 (the council’s approved amount).

71 Ogden Daily Standard, January 9, 1895, January 21, May 30, 1896.

72 For the 1888 law, see Laws of the Territory of Utah (Salt Lake City: Tribune Printing, 1888), 161; Samuel Richard Thurman et al., The Compiled Laws of Utah: the Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the United States and Statutes of the United States Locally Applicable and Important (Salt Lake City: H. Pembroke, 1888), 1:299; Allen, “Development of County Government,” 33–39.

73 Ogden Daily Standard, January 8, 9, April 9, 13, 29, May 20, June 3, 1895.

74 “Mayor Brough’s Valedictory,” Ogden Daily Standard, January 1, 1896, 17. Brough eventually served as an administrator of the Dee Memorial Hospital. Auxiliary to the Weber County Medical Society, The History of Medicine in Weber County from 1852 to 1980 (n.p., 1983).

75 Ogden Daily Standard, July 28, August 4, 7, 1896.

76 Recorder Correspondence, user box 24, files 8794, 8854, 8855, 8923.

77 Salt Lake Tribune, November 21, 1896; Ogden Daily Standard, November 21, 1896.

78 Ogden Daily Standard, March 8, 1894, June 16, 17, 18, 25, July 27, December 3, 1898.

79 Ogden Daily Standard, May 29, September 1, 1896, January 7, February 17, 25, March 30, 1897.

80 Ogden Daily Standard, February 16, 1897; Recorder Correspondence, user box 24, files 9081, 9134, 9135.

81 Of the original thirty-two medical staff members at the Dee Memorial Hospital in 1911, all of them “qualified” by contemporary standards, just under 40 percent were already listed in the 1896 city directory. Ogden City Directory (Ogden: R. L. Polk, 1896); Eleanor B. Moler, A Tradition of Caring (n.p., 1982).

82 Starr, Social Transformation, 154–62.

83 Ogden Daily Standard, March 31, 1899.

84 Ogden Daily Standard, March 18, April 13, 1899, September 13, 1900, June 28, July 7, August 6, November 17, December 8, 1902, September 12, 1904, May 11, 1906. Cases mentioned in the press include gunshot wounds, head injury, crushed bones, meningitis, typhoid, pneumonia, stomach cancer, necrotic foot repair, female conditions, postamputation surgical repair, orthopedic repairs, elective amputation, tissue excision, stroke, brain abscess, bad back, and rheumatism.

85 “Changes at Hospital,” and want ads, Ogden Daily Standard, October 17, 1902; see also Polly Aird, “Small but Significant: The School of Nursing at Provo General Hospital, 1904–1924,” Utah Historical Quarterly 86, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 102–27, for the role and experience of a nurse matron at a contemporary Utah hospital.

86 Ogden Daily Standard, February 27, 1906.

87 Ogden Daily Standard, June 28, 1901, May 9, 11, 1906; Salt Lake Tribune, August 3, 1906.

88 “City Council Meeting,” Ogden Daily Standard, October 2, 1900.

89 Ogden Daily Standard, March 21, 1899, December 21, 1901.

90 Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 3, 1905, October 29, 1906, March 3, August 3, 1908; Deseret Evening News, August 4, 1908. The Southern Pacific also opened a hospital facility in Ogden for workers of Japanese descent, staffed by trained Japanese physicians. This facility remained in operation until at least 1913. “Hospital in Ogden for Japs,” Ogden Daily Standard, April 15, 1905; Ogden City Directory (Ogden: R. L. Polk, 1913).

91 Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 24, October 4, 1907.

92 Ogden Evening Standard, March 28, 1911. This might represent a developing sensitivity to patient privacy on the part of the hospital and perhaps accounts for the reduced number of admission notices one sees after about 1905.

93 Ogden Standard-Examiner, September 5, December 4, 1906, January 22, 28, 1907.

94 Ogden Standard-Examiner, August 12, 1908.

95 Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 4, 1907.

96 Moler, Tradition of Caring.

97 Ogden Daily Standard, March 30, 1909, February 25, 1910. In his end-of-term report to the city council, then Mayor H. H. Spencer floated the idea of bonding for the construction of “a modern city hospital,” a suggestion that went nowhere. Ogden Daily Standard, January 16, 1898.

98 Eleanor Moler, Tradition of Caring; Morrell, Utah’s Health, 145.

99 Ogden Daily Standard, February 25, 1910.

100 Salt Lake Tribune, October 1, 1911; Ogden Standard, September 19, 1911, December 17, 1914; Ogden Evening Standard, November 2, 1911.

101 Weber County Public Records, Weber County Assessor’s Office, Ogden, Utah.

102 Tom Vitelli, The Story of Intermountain Health Care (Salt Lake City: Intermountain Health Care, 1995).