48 minute read

When Buffalo Bill Came to Utah

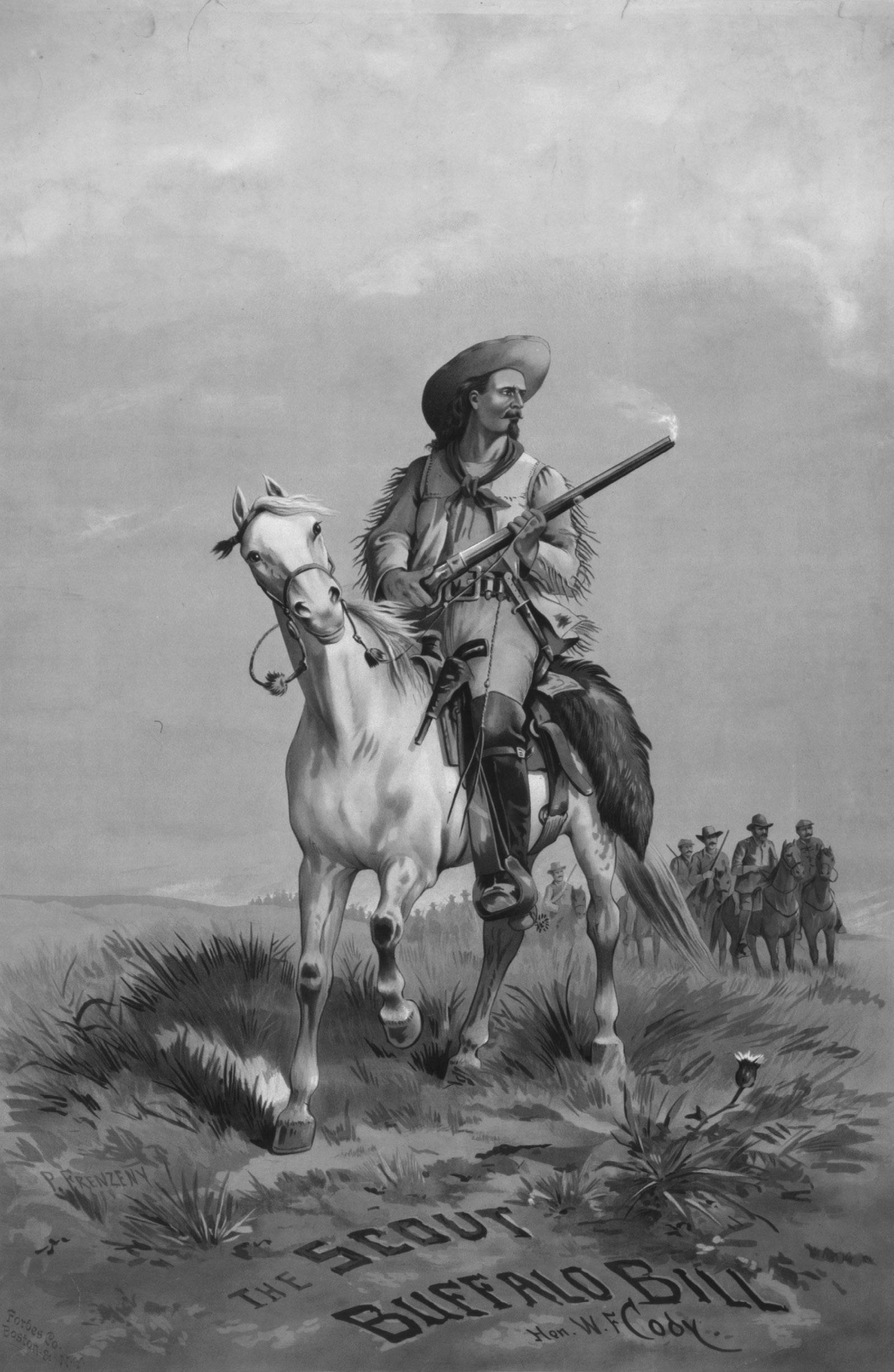

A lithograph portrait of William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody, inscribed “The Scout Buffalo Bill. Hon. W. F. Cody.” Paul Frenzeny, artist. Boston and New York: Forbes Co. Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIGpga-01266.

When Buffalo Bill Came to Utah

BY BRENT M. ROGERS

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody—perhaps the most famous American entertainer of his time—made a handful of documented visits to Utah in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That era had Americans looking to and thinking about the West, even as a celebrity culture grew in the East. Cody, the western army scout turned actor, emerged as the best-known celebrity symbol of the West. He rose to prominence as a stage performer and became an international sensation through his Wild West show. Buffalo Bill’s biographers have demonstrated that his persona and performances of created and recreated historical events significantly helped to define the meaning of western history and identity for generations of Americans. 1

Yet in all of this, scholars have given little attention to Cody’s relationship with and portrayal of Utahns and members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2 In the 1870s and 1880s some of Buffalo Bill’s routines portrayed Mormons as anti-American threats in the West. But by the 1890s, Cody began to perceive and publicly represent Utah Mormons as model Americans who played a significant role in conquering and redeeming the West, a shift that coincided with Latter-day Saint efforts to gain national acceptance and respectability. 3 This history provides insight not only into the heretofore unexplored visits of the famous plainsman to Utah but also into Cody as an indicator of the evolving perceptions of Utah Mormons in American popular culture.

The best-known account of Buffalo Bill’s first journey to Utah is one that appears to be dubious at best. According to his 1879 autobiography, an eleven-year-old Bill Cody went to work for the freighting firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell. He claimed to have traveled with the wagon train that supplied the U.S. Army heading west from Kansas “to fight the Mormons” in the 1857–1858 Utah War. 4 As a part of his carefully crafted public image, Cody’s autobiography asserts that he was present when Lot Smith and some “Mormon Danites” burned government supply wagons, leaving the boy Cody and other freighters stranded at Fort Bridger (then in Utah Territory) that winter. 5 While biographers and historians have debated the authenticity of this claim, evidence suggests that Cody fictitiously inserted himself into this scene in American and western history. 6 In the late 1870s and early 1880s, a time when Congress began to strengthen its antipolygamy legislation and when general anti-Mormon sentiment was on the rise, Americans would have understood and appreciated the efforts of the young Bill Cody struggling to combat Mormons, even if fabricated. That careful image-making—and the place of Mormons and Utah in it—provides a useful backdrop for understanding and appreciating Buffalo Bill’s better documented visits to Utah.

William F. Cody’s first verifiable visit to Utah came in May 1879, the same year he released his autobiography. With other performers, he arrived in Salt Lake City on May 1 while on a national tour. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that, after their arrival, Buffalo Bill and his acting company toured the city and visited with officers at Fort Douglas, the military installation on the mountain bench overlooking the capital. 7 Cody then prepared himself for a twonight stand at the Salt Lake Theatre.

During the 1879 tour, Cody’s troupe staged two plays: Knight of the Plains and May Cody, or Lost and Won. The former was a new performance that season and the latter was a production that Cody’s company had presented for the previous two years. The sensational drama May Cody best represents Buffalo Bill’s early portrayal of Latter-day Saint history. It reenacted the Mountain Meadows Massacre, the real-life killings of a California-bound emigrant train by Mormons in southern Utah Territory in September 1857. In his introduction to the play, Charles E. Blanchett, the Buffalo Bill stage manager at the time, described the “truthful incidents” of “horrible butchery” and even claimed that young Bill Cody was present in southern Utah at the time of the atrocious massacre. Buffalo Bill had again been inserted into Utah history. Unlike his autobiography, which placed him on the northern route to Utah at the time of the massacre, the May Cody script placed him in southern Utah ahead of the army and the freighting train on which he supposedly worked. Blanchett went so far as to claim that the young Cody was “one of the few” who had defended the emigrant wagon train, barely escaping from the ruthless Mormons. 8 Blanchett’s statement is historically inaccurate but was likely made to convince eastern American audiences of the authenticity of the play and its hero. The Washington, D.C., National Republican opined that “the plot cannot be said to be a deep one, nor is the play perfect. It seems crude and lacking in refinement, which facts, however, do not detract from the genuineness of the scenes of life on the frontier.” 9 For this reviewer, perceived authenticity was key, and it was heightened by depictions of the well-known Mormon characters John D. Lee, Brigham Young, and Ann Eliza Young.

May Cody used a narrative formula similar to the plots of dime novels of the post–Civil War era—with their dashing heroes, “villainous Mormon elders,” and young women kidnapped into polygamy—and employed these common stereotypes in the form of Danites, polygamy, and the Mountain Meadows Massacre. 10 The Danites were an oath-bound military society organized among the Mormons to protect church members during their conflict with Missourians in 1838, although rumors of their continued existence permeated popular thought well into the late nineteenth century and beyond. 11 May Cody cast the character of John D. Lee— who had been convicted and executed for his role in the actual Mountain Meadows Massacre in 1877, just prior to the play’s opening—as the leader of the “Mormon Danites,” the main villains of the play, billed only second to Cody himself. 12 In Cody’s plays, in dime novels, and in the popular imagination, the Danites embodied the nefarious nature of Mormons and prompted a fear of religious violence. A part of that fear was the controlling influence of ecclesiastical leaders. Enter Brigham Young’s role in May Cody. The play’s synopsis suggests that Lee’s Danites took orders directly from Young to capture the beautiful May. 13 With such a representation, audiences would have viewed Mormons as simpleminded, violent, and unquestionably obedient to the dictates of Young, making the leader and his followers a particularly dangerous group. 14

In one of the play’s scenes, set in the Mormon temple, Brigham Young attempts to force the abducted May Cody into a polygamous marriage. 15 The drama May Cody, then, offered a commentary on the Latter-day Saint practice of polygamy and the perception that it was a vicious, shameful system that kept women in bondage. Here is where the name of Ann Eliza Young becomes especially noteworthy. The show’s playbill lists Ann Eliza Young as one of the prophet’s wives. The real Ann Eliza Young had divorced Brigham Young in 1875 and, a year later, published an exposé entitled Wife No. 19 that summarily condemned polygamy and railed against Mormonism. Her publication added to the already negative perception Americans had toward Latter-day Saints and their practice of plural marriage. That Buffalo Bill’s play cast a character for Ann, given her public efforts to “impress upon the world what Mormonism really [was and] to show the pitiable condition of its women,” suggests that the famous plainsman wanted his audiences to understand the same. 16

Much like the real Ann Eliza Young, the representation of her in the show seems to have been intended to inform the public of the undesirability and unacceptability of Mormonism. Indeed, Cody’s claims of authenticity made his performances both crowd-pleasing and memorable. One eastern newspaper reviewer explained the message embedded in May Cody: “It is a vivid illustration of Mormon iniquity, villainy and crime, and is worth more by its thrilling portrayal of what Mormonism really is, towards awakening the sentiment of the people against the monstrous practices of these people than editorials or speeches could ever amount to. We . . . will say in all earnestness that every scene of every act is thrilling and awakens every emotion of the heart.” 17 Playing on preconceived notions of Mormon Utah, Cody apparently understood that anti-Mormonism was lucrative, and he sold to the people a “genuine” view of the religious group and its history. According to Cody’s autobiography, the opening season of May Cody was “a grand success both financially and artistically,” which contributed to the most profitable season Buffalo Bill had yet experienced. 18

Buffalo Bill’s character in May Cody ultimately saved May from the ominous fate of a forced polygamous marriage, making him the hero and the nation’s protector against peoples deemed un-American. His company’s timely anti-Mormon show gave faces and voices to the most negative tenets of Mormonism. While Cody may not have been involved in the writing of May Cody, he lent his name and persona to a popular anti-Mormon narrative. His production reflected the public’s entrenched perception of Mormon men as lecherous polygamists, especially Brigham Young (even if he had already passed away). It was what audiences wanted to see at a time rife with efforts to end polygamy in the West.

Buffalo Bill’s exhibition of May Cody occurred during the height of anti-Mormonism and antipolygamy legislation in the United States. Besides the publication of Ann Eliza Young’s exposé and John D. Lee’s trial and execution, the 1870s saw the passage of important federal legislation, a momentous federal court decision, and new directions from the nation’s chief executive related to Mormonism. The Poland Act of 1874 enhanced existing anti-polygamy laws. 19 The 1879 Supreme Court decision in Reynolds v. United States determined that the free exercise of religion did not protect local religious practice in domestic relations at the expense of federal laws, which made the Latter-day Saint arguments that the Constitution protected the practice of plural marriage moot. 20 In his annual message to Congress in 1879, President Rutherford B. Hayes pushed for the disenfranchisement of Mormons. To “firmly and effectively” execute marriage laws, Hayes advocated for the withdrawal or withholding of the rights and privileges of citizenship of “those who violate or oppose the enforcement of the law on this subject.” Moreover, Hayes’s administration sought to prevent foreign Mormons from immigrating to the United States. 21

When Buffalo Bill arrived in Salt Lake City for his early May 1879 performances at the Salt Lake Theatre, however, he did not present May Cody. Instead, the Salt Lake City crowds watched Knight of the Plains, a new drama complete with romance, a stagecoach robbery, and a demonstration of Cody’s shooting prowess. 22 Trying to draw a large crowd, Cody apparently chose Knight of the Plains because it did not have content directly related to Latter-day Saints.

A poster (partially damaged) advertising Buffalo Bill’s production, May Cody, or Lost and Won. Sensational and melodramatic, May Cody played on negative stereotypes of Mormon life. Buffalo Bill’s troupe toured with May Cody in 1879 but presented another show in Salt Lake City that year. New York: H. A. Thomas Lithograph Studio. Courtesy Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-54797.

The large Mormon population in Salt Lake City almost certainly would have frowned upon the damaging depiction of its religious culture and the darkest event of its recent past. Reporting on the contents of May Cody, the Washington, D.C., National Republican opined, “Mormon life is shown in all of its repulsive details, from the interior of the temple to the diabolical plots in the wilderness.” 23 The Buffalo Bill production company opted for the less sensational Knight of the Plains. Despite Cody’s efforts to play to the local population, his show brought in only a “fair-sized crowd.” In its review of Knight of the Plains, the Deseret News stated bluntly that it could not recommend the actors “as first class,” noting that the dialogue was often inaudible and that the play dragged considerably. Still, the Mormon-affiliated newspaper did enjoy the spectacle of the stage robbery and “Mr. Cody’s fancy shooting.” 24

Following two days at the Salt Lake Theatre, the company continued its tour. Cody would not return to Utah for nearly seven more years. During this interim, the United States government fortified its campaign against polygamy in Utah. Presidents Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland both hurled insults at the “barbarous system,” while Congress passed stronger antipolygamy legislation with the 1882 Edmunds Act. 25 The disdain that the government and the public had for plural marriage had nearly reached its zenith when Buffalo Bill returned to Utah.

In late February 1886, Cody and his company traveled via rail from Evanston, Wyoming, to Ogden to put on another new play, The Prairie Waif, at the Union Opera House. 26 This time, at the pinnacle of national anti-Mormonism, Buffalo Bill did not shy away from a performance that cast Mormons as villains. Descriptions and reviews of The Prairie Waif vary, but one newspaper remarked, “The plot is simple, yet very instructive, interesting, and laughable. Onita, a little prairie flower, is captured by the redskins and Mormons, and after ten years time, is discovered by Buffalo Bill, rescued and taken back to her father, after thrilling skirmishes and desperate encounters.” 27 The Salt Lake Herald’s announcement of the coming production did not include a description of its anti-Mormon content but simply declared, “‘Prairie Waif’ is one of those plays calculated to picture frontier life, with its various vicissitudes, and especially the thrilling adventures of a scout.” 28 The Ogden Herald also dropped any mention of the content and simply stated, “The company are highly spoken of by the press of the country, and we may expect a magnificent performance.” 29

The hype did not disappoint the Ogden crowd. According to the Herald’s summary of the one-night stand on February 26, the audience applauded the drama wildly and the reporter found “the acting throughout the entire play was all that could be desired. Mr. Cody (‘Buffalo Bill’) makes a grand hit as the rough, uncultured, but steel-hearted scout, and hero of the play. Miss Lydia Denier as the ‘Waif,’ played with exquisite taste the part of the longlost daughter of General Brown.” 30 The next morning, Buffalo Bill’s stage company traveled roughly forty miles south to Salt Lake City on the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. At about 11 a.m., the group of twenty individuals arrived at the Valley House, a commodious downtown hotel located on the southwest corner of South Temple and West Temple. 31 That afternoon, a downtown street parade for the company preceded a matinee showing of The Prairie Waif, which filled the Salt Lake Theatre “to excess.” 32

The Cody troupe came to Salt Lake City just one day after the internationally respected Italian actor Tommaso Salvini had performed in the city. Salvini impressed the crowd and newspaper critics by displaying his marvelous talents in a French tragedy entitled The Gladiator. Salvini spoke in his native tongue, but even those who did not understand Italian, one Salt Lake City newspaper declared, would enjoy the power of this acting master. 33 The Salt Lake Herald’s reporter couldn’t help but compare the skill and sophistication of Salvini with the players in Buffalo Bill’s western. The Herald critic wrote, “Mr. Buffalo Bill has secured a coterie of artists whose merits might cause Salvini himself to blush—for his profession.” In contrast to the Ogden reporter’s review, the Salt Lake newspaper writer mocked Cody’s acting abilities, suggesting that he was better suited to be a streetcar driver than an actor. The writer further criticized the western drama’s dialogue: “Miss Lydia Denier, the Waif, herself who gave utterance to all such thrilling chestnuts as ‘unhand me, villain!’, ‘Your bride? Never. I’d rather be a corpse!’ and ‘Death rather than dishonor’ in much the same tone. . . . It was a grand spectacle; one we hope, which we shall never be called upon to sit through again.” The critic blamed the Salt Lake Theatre’s management for scheduling Buffalo Bill immediately after Salvini. 34 In the end, the Herald’s critic scoffed at the inelegance and crudeness of the western scout, viewing him as an affront to refined acting of a “highbrow” professional. This assessment might suggest a deeper message. It points to a people in a time and place yearning for respectability after decades of prejudiced opinion about the Latter-day Saint faith and its practices. The message appears to be that Utahns, especially those residing in Salt Lake City, appreciated fine art and were refined in their cultural tastes in contrast to the lasting negative portrayal of Mormonism that the popular performer, Buffalo Bill, brought to the stage.

Cody’s troupe played Salt Lake City just that day and continued touring before returning to Park City, Utah, for a show on March 29, 1886. Cody then took leave of Utah for another six years, during which time Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act. That draconian 1887 measure, among its many stipulations, required plural wives to testify against their husbands and disincorporated the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 35 Three years later, in 1890, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Edmunds-Tucker Act and the Latter-day Saint president, Wilford Woodruff, issued a statement encouraging his church’s members to obey federal marriage laws. 36 Meanwhile, Buffalo Bill took his act overseas, growing his international brand and earning the applause of the Queen of England herself. 37

When he returned to the Great Basin in 1892, Cody brought with him an entourage that included British military officers. According to John Burke, the general manager and press agent for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, “When abroad Buffalo Bill heard so many officers of the army of France, England, and other countries ask about the Wild West of America, its game and wonderful scenery, that he extended an invitation to a number of gentlemen of rank and title to join him, with others from this country, on an extended expedition to the Grand Cañon of the Colorado, and thence on through Arizona and Utah to Salt Lake City on horseback.” 38 The expedition’s participants included the English officers W. H. MacKinnon and John Mildmay, Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, and two Utahns, Daniel Seegmiller (a Latter-day Saint ecclesiastical leader in and former sheriff of Washington County, Utah) and Junius F. Wells (a life-long Utahn and organizer of the church’s Young Men Mutual Improvement Association). 39

Outside of Burke’s notation about this trip, little has been known about it. Recently located sources, however, provide new, additional details. It is unclear how Seegmiller and Wells came to be acquainted with Buffalo Bill, but Wells was instrumental in organizing the expedition. Wells’s journal notes that in late October 1892 he traveled to New York City, where a telegram from Colonel William F. Cody awaited him. 40 On October 25, Wells met with Cody and Prentiss Ingraham at the Hoffman House hotel, a favorite lodging place for Cody in New York City, where Cody, Ingraham, and Wells “had good friendly chat & went over general plan of the trip West.” 41 Five days later, Wells wrote in his journal that he was “very busy with arranging [the] trip west.” 42 In early November, the men began to travel west by rail. On Friday, November 4, Wells arrived and spent the next couple of days at the North Platte, Nebraska, home of William F. Cody. 43 The expedition reached Flagstaff, Arizona, a few days later and began its journey north to the Grand Canyon and beyond.

William F. Cody and his traveling companions in Kanab, Utah. Utah State Historical Society, MSS C 103, box 2, fd. 1, no. 9.

In late November, Wells, Cody, and the rest of the party reached southern Utah and stopped at the border town of Kanab. 44 While there, they met Anthony W. Ivins of St. George and Edwin Woolley of Kanab, two Mormon ecclesiastical authorities from southern Utah. Buffalo Bill and his fellow travelers received lavish hospitality from the residents of Kanab, which they greatly appreciated. 45 Proceeding on to Richfield, Utah, on December 5, the party took the rails the next day and reached Salt Lake City, finding lodging at the downtown Templeton Hotel. 46 The Cody company “made their entry into the city in a six-horse coach, and attracted no little attention on account of the genuine frontier style in which they were driven to the hotel. Buffalo Bill was immediately surrounded by old friends and new acquaintances, while his companions were made willing captives by members of the Union Club, who extended to them the freedom of its rooms.” A Salt Lake Tribune reporter took the opportunity to hold a thirty-minute conversation with them. The Tribune published a synopsis of the meeting and gave Cody a hearty introduction by noting that his “exploits on the plains and recent exhibitions in Europe have made him familiar to almost every member of the English-speaking race.” 47

While in Salt Lake City, Junius F. Wells introduced Buffalo Bill and the party to the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which then consisted of Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F. Smith. Following that meeting, Wells shepherded them up the hill to meet with U.S. Army officers at Fort Douglas. 48 Reporting on the day spent in Salt Lake City, the Washington Post stated, “the party were entertained by President Woodruff, the head of the Mormon Church, and the Twelve Apostles, and every courtesy was shown them. At Fort Douglass, Gen. Penrose and his officers entertained Col. Cody and his party most royally, and the English officers were delighted with the drill of the Sioux soldiers and life in an American frontier post.” 49 Cody’s party had an enjoyable visit in Utah’s capital city. Having spent nearly six weeks together, Wells saw Cody and the other men board a train and bade them farewell as they departed the city on December 8. 50

The timing of Cody’s 1892 visit to the Great Basin and his meeting with Latter-day Saint authorities in Salt Lake City is worth noting. It came just two years after Wilford Woodruff issued the manifesto calling for the end to the practice of plural marriage among Mormons. It also came amid the continued efforts of Utahns to attain statehood, which had evaded them for more than forty years. From at least the mid-1880s, Latter-day Saint officials had engaged in public relations campaigns to neutralize and overturn the longstanding negative public image of the church and its people. They were painfully cognizant of the ways the larger American public had perceived them and sought to change their image. For example, they had made alliances with powerful political lobbyists and eastern newspaper editors, hoping to engender a more positive image. 51 While it is unknown precisely what was said during Cody’s meeting with the church’s First Presidency or in his many interactions with Junius F. Wells and others, it seems likely that the Latter-day Saint men wanted to persuade Buffalo Bill to publicly treat them more favorably than he had in his productions of May Cody and Prairie Waif. Mormons were desperate for national respectability, and Buffalo Bill, with his immense popularity, could help them attain it.

Following his great 1892 adventure, Cody wrote two private letters from Chicago to Wells about the potential of a business venture that the men likely discussed during their time together. 52 Buffalo Bill had been in the Intermountain West seeking to develop a natural game park and preserve. He used the expedition through the Grand Canyon country and into Utah as an opportunity to find a suitable tract of land to create a space for the conservation of western animals. Cody lamented, “Outside of the National Park at Yellowstone, America is wholly devoid of any place for the preservation of game.” 53 On its journey through the Grand Canyon and into southern Utah, Cody’s party saw “mountain sheep, elk, deer, antelope, mountain lion, wildcats, and coyotes,” as well as plentiful numbers of quail, ducks, grouse, and turkeys. 54

Cody was anxious to create an environmental conservation zone in the West. He wanted to speak with Wells on the matter but worried that they would not be able to secure “a sure title” to a large enough tract of land to proceed. 55 Although this endeavor failed to materialize, that he sought the Great Basin further indicates a shift in the ways that he conceived of Utah, its people, and its natural resources.

Even as Buffalo Bill privately pursued business ventures in Utah, he also made public remarks about Mormons following his 1892 expedition into Utah. “The Mormons,” Cody told the Washington Post, “are law-abiding, energetic, and hard-working people, and, as far as he could judge, good American citizens.” 56 Such a statement reversed the barbarous and anti-American image of Mormons presented in his earlier stage performances. The Post further informed its readers that Cody expressed satisfaction and even pleasure at a January 4, 1893, proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison. The president had granted amnesty and pardons to Mormons who had forsaken their unlawful cohabitations and plural marriages in order to “faithfully obey the laws of the United States.” 57 In fact, Cody and his colleague Prentiss Ingraham further lauded Latter-day Saints when they informed the Post that “Mormons in Utah were living up to the letter of the law against polygamy.” 58 Such a statement would have pleased Latter-day Saint leaders, who remained on the defensive against the entrenched image of Mormon polygamy. The public-facing remarks of the most popular American had shifted by 1893; his statements signaled to others that Mormons could now be accepted as respectable American citizens.

Around this time, the Logan-based Utah Journal published a letter written by Buffalo Bill that provides even more insight into his views of Utah and its people. Amid words about the territory’s grandiose scenery, Cody wrote a glowing statement of his experience with Utah Mormons. In Kanab, Cody stated, he was

He proceeded to explain that “plural marriages are abolished among them now under the law,” and that there was “a resigned acceptance of the situation among all with whom we talked.” Such acceptance, even if resigned, was enough to convince Cody that Mormons had been reformed and that the rest of their religion and culture were acceptable. Buffalo Bill painted a picture of a refined, settled, family-oriented people, which was a significant change from the stage plays replete with lecherous old men and lawless Danites that he had presented nearly fifteen years earlier.

Cody also wrote about the enterprising nature of Utah’s Mormons and their desire for statehood, which was then still three years away. “The Mormons seemed too wide awake,” he explained, “not to have their country improved and to bring wealth and immigration into it, independent of creed, and they did all in their power for our comfort, and to show us what the country was capable of. Out of a desert they have made a garden spot.” 60 Taken together, these messages foreshadowed the ways in which Americans began to talk about Utah. No longer caricatured as a land of backward polygamists, Utah was a place of good, industrious American citizens who had reclaimed a land devoid of natural resources. 61 In the 1890s, the Latter-day Saints faced a major challenge in convincing people that they had changed. It appears, however, that they had convinced Buffalo Bill, whose celebrity status could only help to improve the national perception of them.

Mormons had long advertised their own hard work and pioneering character to justify their dispossession of Native peoples and their efforts to make Great Basin lands flourish. In the 1890s, white Americans especially glorified the white pioneers who had supposedly conquered the western frontier. 62 Buffalo Bill’s articulation of the Mormon settler experience allowed other Americans to more readily recognize and embrace this peculiar group. His praiseworthy statements, in effect, celebrated the Mormon effort and incorporated it within the larger national story of white westward progress at a time when Americans began to revere the “winning of the West.” 63 In other words, Cody used his profound celebrity to help integrate a once-maligned people into the national narrative of westward expansion. Furthermore, by highlighting their traits of industriousness and their ability to tame dry lands and by downplaying their unusual beliefs, Cody dropped the negative perceptions of the Mormons and focused instead on what he viewed as positive developments in the West. 64 This was the type of press that Latter-day Saint leaders had been fighting for, a harbinger of the favorable publicity that would continue with the 1893 Chicago world’s fair and Utah statehood in 1896. 65 At a time when industrialization and urbanization prompted more and more eastern Americans to look at the opportunities of the West, Mormon history and society now demonstrated to those seekers the viability of thriving in the arid region.

The 1890s found William Cody determined to build up the Big Horn Basin in Wyoming. By then, the former star and producer of May Cody had become so positive about Utah and Mormons that he viewed them as a model for Big Horn Basin settlement. In an 1898 letter, Cody wrote,

Cody’s vision to make the Big Horn Basin bloom reflected his observations of Mormons and their own efforts in Utah.

His vision also echoed those of other observers who associated Mormons with productive irrigation works. For example, in his writings about the Chicago world’s fair, E. A. McDaniel described the displays seen at the Utah Agricultural Pavilion. The pavilion’s innovative irrigation diagrams and maps, which detailed “how the Mormon pioneers had made the Territory’s desert ‘blossom as the rose,’” captivated hundreds of thousands of curious visitors, according to McDaniel’s account. 67 Similarly, in The Conquest of Arid America, William Smythe wrote at length about the agricultural, industrial, and economic success of Utah. Such prosperity was built on the foundation of irrigation. Smythe lauded Salt Lake City’s irrigation works, which furnished a water supply for the sixty-thousand inhabitant metropolis. Moreover, he praised the Mormons as pioneer irrigators who made civilization flourish in Utah and whose example would help the rest of the West develop and prosper. 68 By adapting irrigation techniques, Latter-day Saints thrived amid difficult climatic conditions in the Great Basin. Buffalo Bill and other Americans respected Utah’s irrigation systems, hailing them as the blueprint for success in the arid West.

William F. Cody owned hundreds of thousands of acres of land and water rights in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin. Seeking to build a great metropolis there, since the mid-1890s, he had struggled mightily to get settlers to move there and to construct the necessary infrastructure, most notably irrigation canals. 69 Hoping to populate the basin and find help developing canals in the area, he recruited Latter-day Saints. 70 Buffalo Bill publicly praised the religious group as “the greatest irrigators on earth.” After news broke that he was recruiting Mormons to northwest Wyoming, Cody gave an interview with a midwestern newspaper in January 1900 in which he exclaimed, “Look what they did with the Salt Lake country! Well, I expect them to do the same thing in the way of irrigation in the Big Horn basin.” 71

In early February 1900, the Latter-day Saint apostle Abraham O. Woodruff, son of Wilford Woodruff, and a party of a dozen others set out from Utah and met Buffalo Bill at Eagle’s Nest, Wyoming, about fifteen miles east from the young town of Cody, Wyoming. During this meeting, according to Charles Welch’s recollection, Colonel Cody said, “I have secured a permit to irrigate nearly all of the lands on the north side of the Shoshone River, from Eaglesnest to the Big Horn River, but if the Mormons want to build a canal and irrigate the land down lower on the river I will relinquish both land and water to them, for if they will do this I know they are the kind of people who will do what they agree to do.” 72 What an offer! Free land and water rights to a substantial tract demonstrated both Buffalo Bill’s desperation and generosity. Nate Salsbury, one of Cody’s business partners, insisted that the Mormons pay $20,000 for the rights, but the showman did not make them pay. He saw more value in his liberal offering. It would bring in hundreds of settlers willing to fund and construct their own canals, which would in turn create essential infrastructure to encourage greater settlement and business opportunities in the Big Horn Basin. Approximately two weeks later, Cody relinquished his company’s right to 21,000 acres of land and water rights on the Shoshone River to Abraham Woodruff, at no charge. With water rights secured, Woodruff organized the Big Horn Basin Colonization Company, and by May 1900, a group of Latter-day Saints began work on an irrigation canal in the basin. 73

Wyoming state officials likewise visited Utah, hoping to boost Mormon colonization into the northwestern part of their state. According to a Deseret News story, they believed “Utah people to be desirable citizens whom they are glad to see added to their population.” 74 These government officers shared Cody’s view of Utah Mormons as hard-working Americans who could turn the basin into a “veritable garden spot.” 75 Now that Mormons were perceived as acceptable citizens, Buffalo Bill and Wyoming state officials acted opportunistically in recruiting Utahns to the Big Horn Basin to buoy its fledgling settlements and further encourage infrastructural developments in the area. 76

Even as he courted Mormon settlement in northwest Wyoming, Cody embarked on still more national tours with his Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World. The 1902 season brought the internationally famous entertainer back to Utah. On August 3, 1902, the Salt Lake Tribune alerted valley residents to the Wild West’s pending visit on August 13 and 14. The advertisement noted that Buffalo Bill’s spectacle was “now in the Zenith of its Overwhelming and Triumphant Success” and reminded readers of the show’s apparent authenticity, stating that it was “an exhibition that teaches but does not imitate.” The Tribune alerted potential attendees that the two performances each day would take place “Rain or Shine” and directed them to purchase tickets at the Smith Drug store on Main and Second South. 77 The auspicious advertisement proved prescient as tens of thousands of Utahns flocked to the grounds on Eighth South and Fourth West to witness the great exhibition of “devil-may-care cowboys, the dashing cavalrymen, the gaudily painted Indians and the various other attractions that go to depict the strenuous life of the world.” 78

Alongside the Wild West, John M. Burke also returned to Utah for the first time since he had accompanied the exploration party there in 1892. Burke, the show’s press agent, expressed his astonishment at the “wonderful improvements which have been made around the city since that time, and said that from what he had seen so far this was one of the liveliest burgs he had struck since leaving Chicago.” 79 Salt Lake City was certainly abuzz for Cody’s display. Men, women, and children occupied every seat at the enclosed exhibition, and while many monopolized the standing areas, hundreds were denied admittance. 80 The audience, among whom were “hundreds of men whose every-day life either of the past or present was being depicted in some of the cowboy and military scenes,” found the Wild West remarkable and appreciated its authentic feel. The front page of the August 14, 1902, Deseret Evening News declared, “Buffalo Bill is distinctly and unmistakably the man of the hour in Salt Lake” following his performances the previous day. 81

Buffalo Bill had a busy time in Salt Lake City. Following the afternoon presentation on August 13, Cody met Governor Heber M. Wells, the younger brother of Junius F. Wells, for dinner. He also visited several other friends prior to the evening show, which, like the matinee, dazzled some 15,000 spectators. 82 The next morning, Cody and his daughter called on the Latter-day Saint First Presidency—Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and John Henry Smith—at the Beehive House for an affable half-hour-long meeting. 83 The Deseret Evening News reported on this meeting, describing it as an effort to cement the friendship that had developed between Cody and the Latter-day Saints. Buffalo Bill emerged with “words of praise and commendation for the ‘Mormon’ people.” 84 Latter-day Saint leaders— conscious of their still-tenuous national reputation and with ongoing business and colonization interests in northwest Wyoming—sought to keep friendly relations with the showman. For his part, Buffalo Bill continued to offer positive public statements about Latter-day Saints despite some tension then brewing between him and the settlers in the Big Horn Basin, who were trying to acquire more prime land along the Shoshone River. 85

Two icons of the American West—Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Salt Lake Temple—seen together, circa August 14, 1902. Courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave, ID no. 70.0304.

Cody left his rendezvous with Latter-day Saint leaders and hurried to the Mormon tabernacle to attend a special organ recital with his company of some 300 individuals, a concert held specifically in their honor. “This meeting,” according to the Deseret Evening News, “was probably the most unique gathering that ever assembled in the great building.” The Wild West performers sat in the tabernacle dressed in their arena garb awaiting the concert, while residents and spectators poured into the galleries. Within twenty minutes, the tabernacle had an estimated 10,000 people in its bowels, another capacity crowd. Cody relished the event and gave high compliments to the singers and organist. In a statement to a Deseret Evening News reporter, he exclaimed, “Wonderful. The most marvelous building, all things considered, I was ever in. And certainly the most marvelous organ I have ever seen or heard—both the creations of a wonderful, yes, a very wonderful people.” The two Wild West shows of the 14th again filled the arena to the brim; in all, it is estimated that more than 60,000 people witnessed Cody’s exhibition in its two-day run in Salt Lake City. The celebrated scout commented on the turnout: “It simply proves what has so often been said of Salt Lake. It is the greatest amusement center of its size in the country.” 86 At the height of his international popularity, Buffalo Bill did big business in Utah’s capital city. Following his departure, Cody took his Wild West overseas in 1903; he did not return to Utah to perform for another five years.

Looking east from the Union Depot along Twenty-Fifth Street in Ogden, Utah. Advertisements are visible for Ringling Brothers Circus and Buffalo Bill’s Rough Riders on August 7 and August 12, 1911. Utah State Historical Society, Photo no. 21685.

By the time of Buffalo Bill’s penultimate visit to Utah in 1914, a reconfiguration of memory had taken place. “In days of old,” an Ogden Standard article proclaimed, “when they were not so well and favorably known and the practice of polygamy created almost universal prejudice against them, the great scout was one of the best friends of the Mormons, and was always ready to praise them for their industry, thrift, sobriety, honesty and other desirable characteristics, as he had observed them during their operations in the course of making the desert blossom as the rose, and establishing the nucleus of our now great and prosperous intermountain empire.” 87 Cody’s anti-Mormon

performances of the 1870s and 1880s apparently had been forgotten. Instead of a fascinating trajectory that began with pernicious perceptions of Mormons and concluded with mutual embrace and influence, this Utah newspaper column collapsed the narrative to highlight a constantly positive connection between the place, its people, and the celebrity.

The history of William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s documented visits to Utah offers insights into the evolution of Utah and Mormons in American popular culture in an era that saw Mormons included in narratives of white western expansion and becoming more acceptable to the national body politic. Latter-day Saints had long sought national acceptance and respectability. American perceptions of the dominant religion in Utah were negative and even hostile for most of the nineteenth century. Cody traded on those unfavorable perceptions and grew his business by doing so. After Latter-day Saint leaders called for the end to the practice of plural marriage in 1890 and after Buffalo Bill’s own 1892 journey from the Grand Canyon to Salt Lake City, a transformation occurred in Cody’s perception of and public pronouncements about Mormons. Further, the 1890s were a time that saw more Americans looking westward and

lauding the white pioneers, Mormons among them, who had made arid lands productive.

Cody’s influence and affirmation provided a powerful voice, indicative of a shift in popular opinion during a national reimagining of Mormonism. At the same time, Utah and its Mormon population inspired Buffalo Bill’s own view on town-building in a new West that required persistence, industriousness, and irrigation. Still, plenty of anti-Mormon sentiments remained. Established narratives die hard. 88 Although Mormons could never totally escape the old perceptions of them, they became appreciated for their desirable traits that proved the possibilities for settlement and success in the arid West. In the end, the shared influence emerging out of the relationship between Buffalo Bill and the Mormons tells us much about the image of Utah and rapidly evolving ideas about the West at the turn of the twentieth century.

Web Extras

Visit history.utah.gov to read an interview with Brent Rogers about this project. We also provide links to a few of the remarkable online resources about Buffalo Bill.

Notes

A resident fellowship from the Buffalo Bill Center of the West and a Charles Redd Fellowship in Western American History from the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies provided funds crucial for the research found in this article. Additionally, the staff of the Papers of William F. Cody opened their doors and their database to give me access to a wealth of pertinent source materials. I would like to extend my gratitude to these institutions and the individuals associated with them, as well as to the peer reviewers and editors of Utah Historical Quarterly, for assisting me in the development of this article.

1 “The Buffalo Bill Party,” Salt Lake Daily Tribune, December 7, 1892; Joy S. Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: Celebrity, Memory, and Popular History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), 5, 7, 123; Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), xi; William F. Cody, The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, Known as Buffalo Bill, ed. Frank Christianson (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), xv–xvi; Jonathan D. Martin, “‘The Grandest and Most Cosmopolitan Object Teacher’: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Politics of American Identity,” Radical History Review, no. 66 (Fall 1996): 92.

2 For book-length biographies, see Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America; Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West; Don Russell, The Lives and Legends of Buffalo Bill (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960); and Robert E. Bonner, William F. Cody’s Wyoming Empire: The Buffalo Bill Nobody Knows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007). According to the Cody Studies “authoritative list of scholarly publications about William F. Cody,” there are no publications directly about Cody’s relationship with Latter-day Saints or Utah. See “Historiography,” Cody Studies, accessed February 13, 2018, codystudies. org/historiography-2.

3 Charles S. Peterson and Brian Q. Cannon, The Awkward State of Utah: Coming of Age in the Nation, 1896–1945 (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and University of Utah Press, 2015), 2, 19.

4 Cody, The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, 69.

5 William Cody committed himself to this story when he met Latter-day Saints in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin in February 1900. To his Mormon visitors, Cody reportedly recounted his career with General Albert Sydney Johnston, who led the army to Utah in 1857. “Exploring the Big Horn Basin,” Deseret Evening News, February 19, 1900. For the autobiographical account of Cody in the Utah War, see Cody, The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, 88–89; see also William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008), 355–58.

6 This is one rare point in which scholars discuss the connections of Buffalo Bill, Utah, and Mormons. See, for example, John S. Gray, “Fact versus Fiction in the Kansas Boyhood of Buffalo Bill,” Kansas History 8, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 12–14; Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 17–21.

7 “Buffalo Bill,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 1, 1879.

8 “Sixth annual tour of the Buffalo Bill Combination in the New and Refined Sensational Drama, May Cody; or, Lost and Won!” box 12, fd. 2, p. 3, William F. Cody Collection, MS 6, Harold McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming.

9 “‘Lost and Won’ At the Opera House,” National Republican (Washington, D.C.), September 27, 1877.

10 Michael Austin and Ardis E. Parshall, eds. Dime Novel Mormons (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2017), ix.

11 “Danites,” Joseph Smith Papers, accessed January 31, 2018, josephsmithpapers.org/topic/danites.

12 For more on John D. Lee and his role in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, see Ronald W. Walker, Richard E. Turley, Jr., and Glen M. Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); and Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001).

13 “Sixth annual tour of the Buffalo Bill Combination,” 3.

14 Historians and writers continue to grapple with such a representation, while others continue to debate Brigham Young’s role in and responsibility for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. See, for example, Bagley, Blood of the Prophets, and Walker, Turley, and Leonard, Massacre at Mountain Meadows.

15 “Sixth annual tour of the Buffalo Bill Combination,” 3.

16 Ann Eliza Young, Wife No. 19, or the Story of a Life in Bondage, Being a Complete Expose of Mormonism and Revealing the Sorrows, Sacrifices and Sufferings of Women in Polygamy (Hartford: Dustin, Gilman, 1876), 32.

17 “May Cody,” Business—Combination—Scrapbooks—

18 Cody, The Life of Hon. William F. Cody, 425; Cheyenne (WY) Daily Sun, May 7, 1878.

19 Plural Marriage Prosecution Act of 1874, Pub. L. No. 43- 469, 18 Stat. 253 (1874). The Poland Act restricted Utah probate courts to matters of estates and guardianship, while all civil, chancery, and criminal cases now fell under the exclusive jurisdiction of federal courts. The Poland Act also reformed jury selection in Utah courts.

20 Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879), 166; see also Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth- Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 119–44.

21 Rutherford B. Hayes, “Third Annual Message,” December 1, 1879, available online at Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed January 29, 2019, presidency.ucsb.edu/node/204252.

22 Advertisement, Salt Lake Tribune, May 1, 3, 1879; Sandra K. Sagala, Buffalo Bill on Stage (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 118–19.

23 “‘Lost and Won’ At the Opera House,” National Republican (Washington, D.C.), September 27, 1877.

24 “Buffalo Bill,” Deseret Evening News, May 3, 1879.

25 Chester A. Arthur, “First Annual Message,” December 6, 1881, and Grover Cleveland, “First Annual Message,” December 8, 1885, both available online at Peters and Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed January 29, 2019, presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/app-categories/ written-messages/state-the-union-messages; Utah Commission, “The Edmunds Act: Reports of the Commission, Rules, Regulations and Decisions” (Salt Lake City: Tribune Printing and Publishing Company, 1883), 3–5; Amendment to 5350 U.S.C., in Compiled Laws of Utah, I (Salt Lake City: Herbert Pembroke Printer, 1888), 110–13.

26 “Route Schedules, Season ’86,” box 10, fd. 2, Cody Collection; Advertisement, Ogden Herald, February 23, 1886; “Buffalo Bill,” Ogden Herald, February 24, 1886; “The Prairie Waif,” Ogden Herald, February 26, 1886.

27 “Amusements,” Milwaukee Chronicle, undated, in “May Cody,” Business—Combination—Scrapbooks— 1879–1880, OV box 40, p. 19, Cody Collection.

28 “Buffalo Bill and His Play,” Salt Lake Herald, February 25, 1886.

29 “The Prairie Waif,” Ogden Herald, February 26, 1886.

30 “The Prairie Waif,” Ogden Herald, February 27, 1886.

31 “Personal,” Salt Lake Herald, February 27, 1886.

32 “Buffalo Bill,” Salt Lake Herald, February 27, 1886; “Dramatic and Lyric,” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1886.

33 “Salvini,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 26, 1886; “Salvini at the Theater,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 27, 1886.

34 “Dramatic and Lyric,” Salt Lake Herald, February 28, 1886.

35 Anti-Plural Marriage Act of 1887, Pub. L. No. 49-397, 24 Stat. 635 (1887).

36 The Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints v. United States, 136 U.S. 1 (1890); “Official Declaration,” Deseret Evening News, September 25, 1890.

37 “Victoria and Buffalo Bill,” Deseret News, May 25, 1887; see Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 282–340; Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 65–92.

38 John M. Burke, “Buffalo Bill” from Prairie to Palace (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1893), available at The William F. Cody Archive, accessed January 27, 2018, codyarchive.org/ texts/wfc.bks00010.html.

39 Burke, “Buffalo Bill” from Prairie to Palace. In 1881, Prentiss Ingraham, under the pen name Frank Powell, wrote an anti-Mormon dime novel, The Doomed Dozen; or, Dolores, the Danite’s Daughter, which featured Buffalo Bill Cody. According to Michael Austin and Ardis Parshall, “This novel brings all of the standard Mormon tropes together in a single place: secretive Danites wearing hoods, a wagon train massacre, women kidnapped to become polygamous wives, murder, betrayal, and, of course, Buffalo Bill, who manages to set everything aright in the end.” Ingraham produced many dime novels in the late nineteenth century; he was also a prominent promoter of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Austin and Parshall, eds., Dime Mormon Novels, xiv.

40 Junius F. Wells, Journal, October 23–25, 1892, box 1, fd. 15, Junius F. Wells Papers, MS 1351, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter CHL).

41 Wells, Journal, October 25, 1892.

42 Wells, Journal, October 30, 1892.

43 Wells, Journal, November 4, 1892.

44 Wells, Journal, November 29, 1892.

45 “The Buffalo Bill Party,” Salt Lake Daily Tribune, December 7, 1892.

46 Wells, Journal, November 29, December 5–6, 1892; “Hero of the Plains,” Salt Lake Herald, December 7, 1892.

47 “The Buffalo Bill Party,” Salt Lake Daily Tribune, December 7, 1892.

48 Wells, Journal, December 7, 1892. George Q. Cannon noted the visit in his journal, commenting specifically on Cody’s appearance: “Cody is a very fine looking man, and wears his hair full length.” George Q. Cannon, Journal, December 7, 1892, The Journal of George Q. Cannon, Church Historian’s Press, accessed February 6, 2019, churchhistorianspress.org/george-q-cannon?lang=eng. Church president Wilford Woodruff also recorded in his journal that Buffalo Bill and company “were very much pleased with their visit to Salt Lake City.” Wilford Woodruff, Journal, December 7, 1892, box 5, fd. 1, Wilford Woodruff Journals and Papers, 1828–1898, MS 1352, CHL.

49 “The Wild West of Today,” Washington Post, January 7, 1893.

50 Wells, Journal, December 8, 1892.

51 Edward Leo Lyman, Political Deliverance: The Mormon Quest for Utah Statehood (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 5, 76–79; Reid L. Nielson, Exhibiting Mormonism: The Latter-day Saints and the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 17, 40–41; Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890– 1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986).

52 William F. Cody to Junius F. Wells, December 22, 24, 1892, box 2, fd. 4, Wells Papers, CHL.

53 “Buffalo Bill on Utah,” Utah Journal (Logan, UT), February 8, 1893.

54 “The Wild West of Today,” Washington Post, January 7, 1893.

55 William F. Cody to Junius F. Wells, December 24, 1892.

56 “The Wild West of Today,” Washington Post, January 7, 1893.

57 Benjamin Harrison, “Proclamation 346—Granting Amnesty and Pardon for the Offense of Engaging in Polygamous or Plural Marriage to Members of the Church of Latter-Day Saints,” January 4, 1893, available online at Peters and Woolley, The American Presidency Project, accessed January 30, 2019, presidency.ucsb.edu/node/ 205484.

58 “The Wild West of Today,” Washington Post, January 7, 1893.

59 “Buffalo Bill on Utah,” Utah Journal (Logan, UT), February 8, 1893.

60 “Buffalo Bill on Utah.”

61 Peterson and Cannon, Awkward State of Utah, 21.

62 Frank Van Nuys, Americanizing the West: Race, Immigrants, and Citizenship, 1890–1930 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2002), 3–9.

63 See Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, 4 vols. (New York: Putnam and Sons, 1889–1896). As Frederick Jackson Turner noted, Roosevelt’s work “portrayed the advance of the pioneer into the wastes of the continent.” Frederick J. Turner, review of The Winning of the West, by Theodore Roosevelt, American Historical Review 2, no.1 (October 1896): 171.

64 Kasson, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 123.

65 Nielson, Exhibiting Mormonism, 40–41; Matthew J. Grow, “Contesting the LDS Image: The North American Review and the Mormons, 1881–1907,” Journal of Mormon History 32, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 111–36; Joseph F. Merrill, “Tabernacle Choir at Chicago Fair,” Millennial Star 96, no. 36 (September 6, 1934): 569.

66 William F. Cody to C. B. Jones, April 9, 1898, University of Wyoming, American Heritage Center, Buffalo Bill Letters to George T. Beck, available online at The William F. Cody Archive, accessed January 31, 2018, codyarchive.org/texts/wfc.css00520.html.

67 E. A. McDaniel, Utah at the World’s Columbian Exposition (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Lithographing, 1894), 37–38.

68 William Ellsworth Smythe, The Conquest of Arid America (New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1900), 55–56.

69 Charles Morrill to Charles W. Perkins, November 4, 1899, box 161, fd. 1186, Subseries 33, CB&Q 33 1890 6, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company Records, 1820–1999, CB&Q.33, (hereafter CB&Q), Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois; Bonner, William F. Cody’s Wyoming Empire, 88.

70 “City and Neighborhood,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 15, 1900; “Exploring the Big Horn Basin,” Deseret Evening News, February 19, 1900.

71 “‘Buffalo Bill’ to Raise Horses,” Kansas City Star, January 21, 1900.

72 Charles A. Welch, History of the Big Horn Basin: With Stories of Early Days, Sketches of Pioneers and Writings of the Author (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), 58.

73 Abraham O. Woodruff, Journal, March 3, 1900, box 1, fd. 1, Abraham O. Woodruff Collection, MS 777, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University; Welch, History of the Big Horn Basin, 58; Bonner, William F. Cody’s Wyoming Empire, 189.

74 “Big Horn Basin Colonization,” Deseret Evening News, February 5, 1900.

75 “Paragraphs of Interest to Big Horn People,” Cody (WY) Enterprise, February 13, 1902; “Mormon Settlements,” Cody (WY) Enterprise, February 27, 1902.

76 William Cody also used Mormon settlement as an opportunity to encourage the Burlington Railroad to construct a spur line into the Big Horn Basin and the town of Cody, Wyoming. William F. Cody to Charles F. Manderson, March 5, 1900, CB&Q 33 1890 6.8, CB&Q; William F. Cody to Charles Perkins, April 2, 1900, CB&Q 33 1890 6.8, Big Horn Basin Files, CB&Q; Cody Town Council Minutes, Excerpts, February 13, 1904, Cody-Early Settlers fd., Park County Archives, Cody, Wyoming; George Austin to Thomas R. Cutler, Report, February 23, 1904, box 5, fd. 1, Abraham O. Woodruff Collection; Welch, History of the Big Horn Basin, 53–54, 58–79.

77 Advertisement, Salt Lake Tribune, August 3, 1902.

78 “Thousands Saw Wild West,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 14, 1902.

79 “Maj. Burke Arrives,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 5, 1902.

80 “Thousands Saw Wild West,” Salt Lake Tribune.

81 “‘Buffalo Bill,’” Deseret Evening News, August 14, 1902.

82 “‘Buffalo Bill,’” Deseret Evening News, August 14, 1902.

83 Anthon Lund, Diary, August 14, 1902, in Danish Apostle: The Diaries of Anthon H. Lund, 1890–1921, ed. John P. Hatch (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2006), 200. The daughter in attendance with Cody was probably his youngest child, Irma.

84 “‘Buffalo Bill,’” Deseret Evening News, August 14, 1902.

85 Bonner, William F. Cody’s Wyoming Empire, 188–205; William F. Cody to Abraham O. Woodruff, March 20, 1900, box 14, fd. 1, Cody Collection.

86 “‘Buffalo Bill,’” Deseret Evening News, August 14, 1902.

87 “A Friend in Days of Old,” Ogden Standard, June 10, 1914.

88 From concerns over post-manifesto polygamy to the Reed Smoot hearings to dime novels and other anti- Mormon popular culture, negative depictions of Mormons continued to influence public perception. See Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 64–66; Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); and Kenneth L. Cannon II, “Mormons on Broadway, 1914 Style,” Utah Historical Quarterly 84, no. 3 (Summer 2016): 193–214. For dime novels, see, for example, The Buffalo Bill Stories, nos. 215, 364, and 366, Series 7: Dime Novels, Cody Collection.