9 minute read

PUBLIC HISTORY: Role Call

Role Call: Creating an Exhibit to Honor Utah Women

BY SABRINA SANDERS

The year 2020 marks the centennial of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ensuring that the right to vote cannot be restricted on the basis of sex. Inspired by this anniversary, we began to think about an exhibition drawn from the collections of the Utah State Historical Society (USHS) that would highlight influential women in Utah’s history. Two small venues were available for the exhibition: the downtown Salt Lake City Public Library and the spotlight wall at the Rio Grande Depot, also in Salt Lake City.

We tossed around ideas related to the exhibit’s theme and agreed on the title Role Call: Fearless Females in Utah History. While deliberating on possible titles, we began with a list of words that communicated ideas about the women we had been researching. Once we had a working list, the wordsmithing began and we hit on an idea: that this exhibition called out individuals like a teacher taking roll call in a classroom or a roll call vote in the Senate. Both examples connected to the ideas of the exhibition. It was easy to make the play on words—role instead of roll—because each of our subjects was a role model. I imagined these women standing proud and responding “Here!” as their names were called. We then conjured up the idea of lining up large portraits of each person across the top of the exhibition, as if they were in a roll call.

As I began my research, I was struck by the individual stories of a number of women, such as Martha Hughes Cannon. The artifacts, photographs, artwork, and writings of these women showcased their courage, drive, and talent. Then came the hard part: finding objects in the historical society’s collections that were at once connected with the women under study, worthy of display, and supportive of telling their stories. What’s more, the objects had to fit in small cases and cabinets. At this point, I had to narrow down the list of exhibit subjects based on the materials available in our collections.

Above: The title graphic for Role Call. Todd Anderson, Utah Department of Heritage and Arts. Right: Setting up the Role Call exhibit at the Salt Lake City Library. In creating this exhibit, we needed to choose subjects with artifacts held by the historical society and artifacts that were relatively small. Courtesy of the author.

Curating the objects for this exhibition had an impact on me: I began to see the women I was researching as whole people and not as one-dimensional heroes whose lives were incomparable with my own experiences. Their writings and photographs revealed the everyday—and relatable—work they did to bring about a change in women’s rights, the rights for women to have not only the vote but also to have a voice, own a business, be provocative, and do the everyday work to advocate for their beliefs. In my desire to bring out the relatable aspects of the women featured in the exhibition, we landed on the idea of using “fun facts.” These would be short statements printed on individual labels and posted around the objects pertaining to a specific individual. The family members of two women we chose to highlight allowed me to interview them. The interviews were insightful and touching, providing intimate details into the women’s lives. Another technique to make these stories and biographies relatable for the audience was the use of informal and conversational language within the exhibition text. Examples of this include the use of first names and short blocks of information for ease of digestion.

The photo essay that follows has been adapted from the library exhibition and its counterpart at the Rio Grande Depot. The image captions here are slightly modified versions of the labels appearing in the exhibition. Our hope for this exhibition was to bring more awareness to the role women have played in shaping our civic identity, inspiring present and future women.

Emmeline B. Wells, 1828–1921

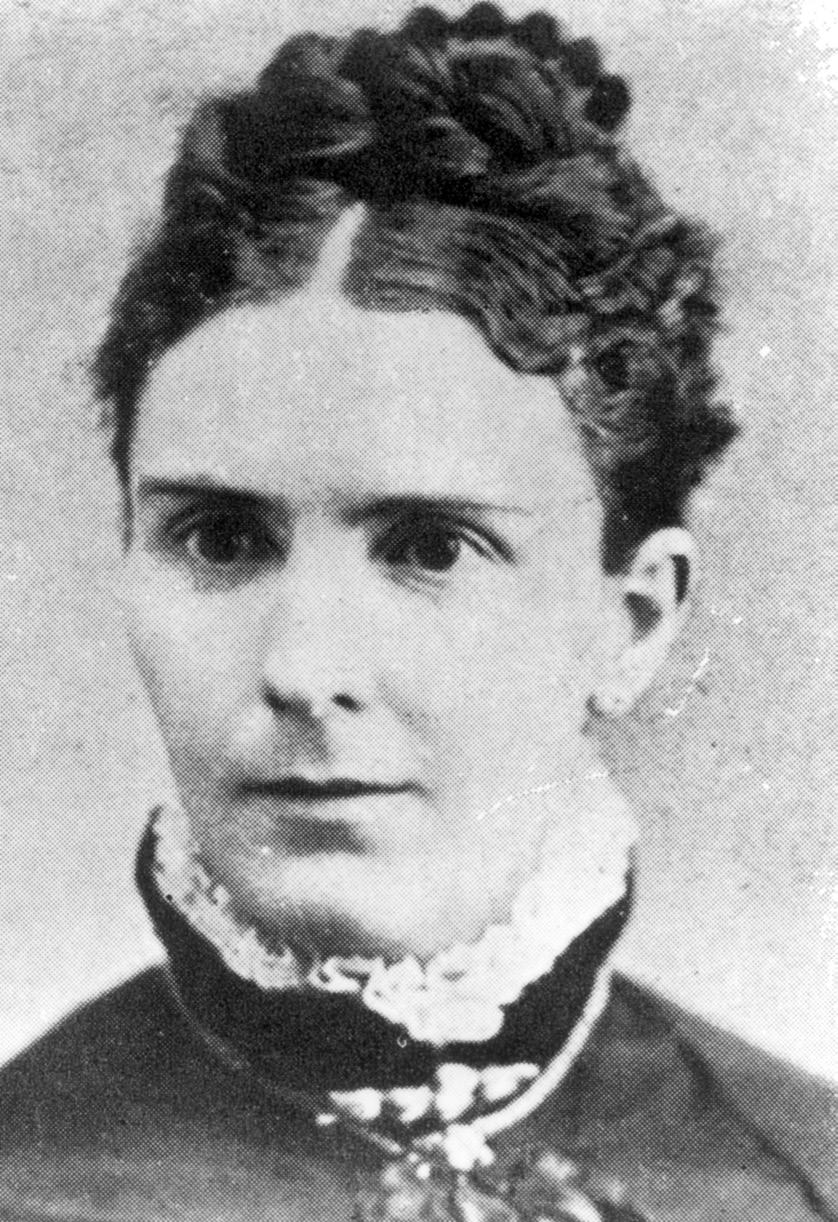

Emmeline worked hard to bring equal rights for women in America through her editorial work, membership with the National Woman Suffrage Association, and connections with the International Council of Women. A prodigious writer, Emmeline used her voice to push for social change at a time when women were seldom allowed to participate in our country’s civic conversations. 1 USHS, photo no. 17800.

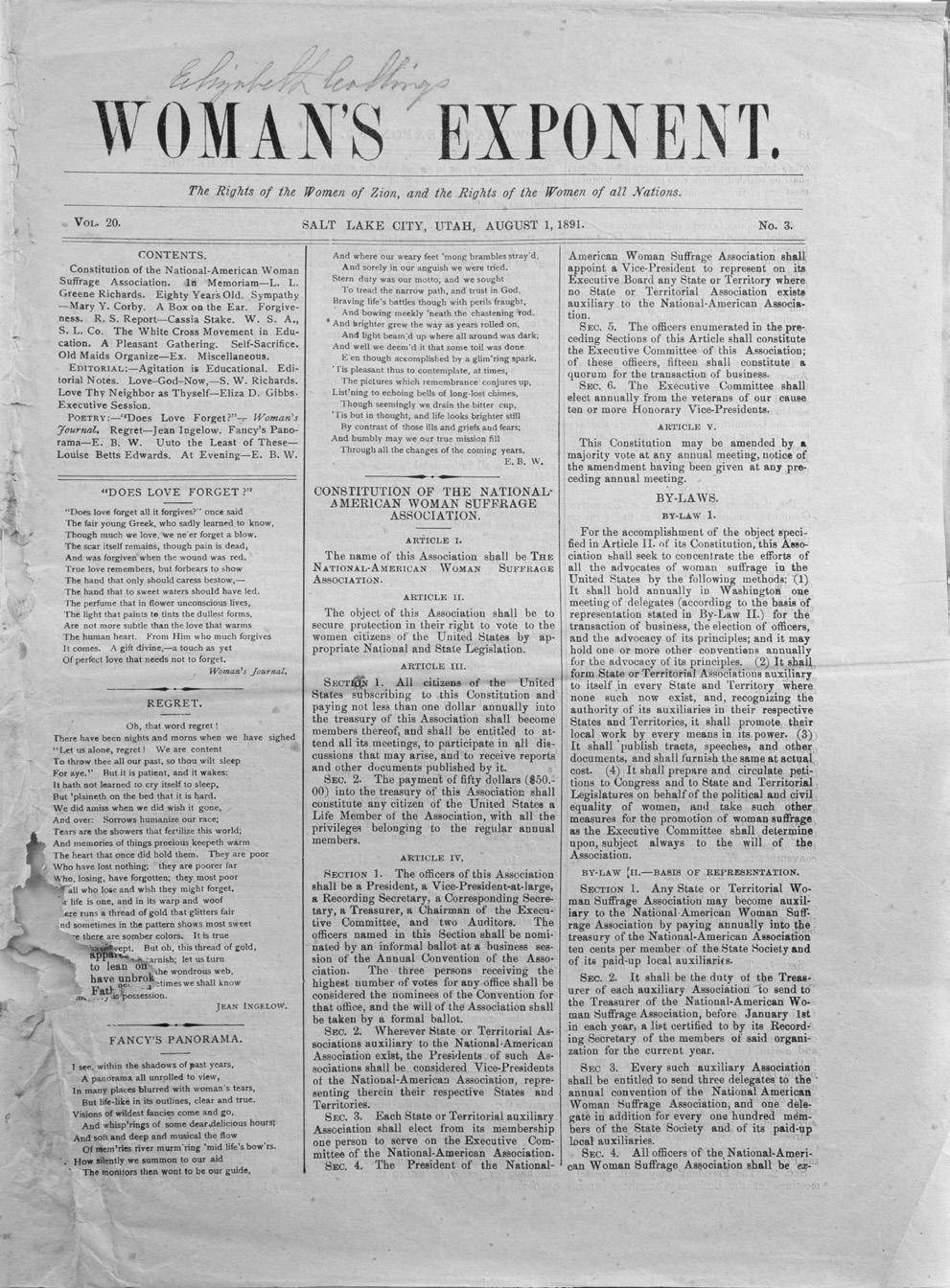

Woman’s Exponent, August 1, 1891, vol. 20, no. 3. In 1877, Emmeline became the editor of the Woman’s Exponent, a twice-monthly publication for Latter-day Saint women. In this capacity, she championed women’s causes and the practice of plural marriage. This edition of the Exponent makes that stance clear: its masthead declares “The Rights of the Women of Zion, and the Rights of the Women of all Nations,” and its front page reprints the constitution of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Chase Roberts, photographer. Utah Division of State History. Emmeline worked hard to bring equal rights for women in America through her editorial work, membership with the National Woman Suffrage Association, and connections with the International Council of Women. A prodigious writer, Emmeline used her voice to push for social change at a time when women were seldom allowed to participate in our country’s civic conversations. 1 USHS, photo no. 17800.

Alice Merrill Horne, 1868–1948

Alice knew the value of art in the community and created the civic framework to support the arts in Utah. Thanks to her diligence, Utah can claim the first state-sponsored arts agency in the nation. Alice was an artist, teacher, legislator, activist, and writer. She developed and wrote school lessons on art appreciation, landscape studies, and architecture—and she was also a clean air advocate. 2 USHS, photo no. 12534.

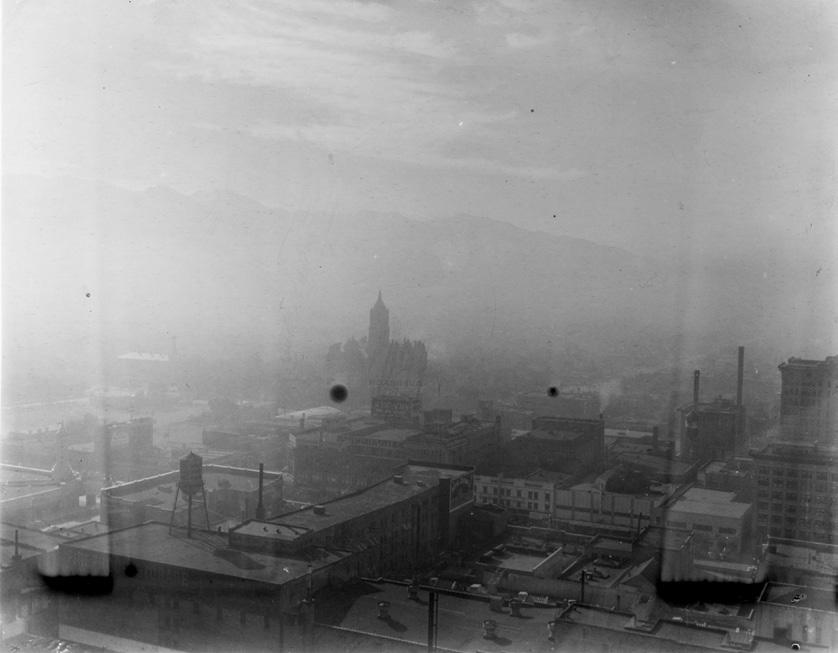

Above: Smog in the Salt Lake Valley, 1942. In response to the poor quality of Salt Lake Valley air, Alice helped organize the Smokeless Fuel Federation of Utah in the 1930s to agitate against pollution. USHS, photo no. 21216. Right: Pamphlet, Smokeless Fuel Federation of Utah, circa 1930. USHS.

Mignon Barker Richmond, 1897–1984

Mignon’s actions to better the community were a lifelong commitment; she was a true civil servant. The countless hours she devoted to serving in organizations such as the YWCA, NAACP, USO, Nettie Gregory Center, and Salt Lake City’s Central City Center only scratch the surface of telling the story of her kind and generous spirit. 3

Turnverein Group, Utah State Agricultural College (USAC), circa 1920. Mignon graduated from Salt Lake City’s West High School in 1917 and went on to become Utah’s first black college graduate in 1921, when she earned a degree in home economics. Because of racism, it would take years for Richmond to find work in her field. Yet she persevered and served in the community throughout her life. Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Merrill-Cazier Library, Utah State University.

Langston Hughes, The Dream Keeper, inscription. Mignon was a friend to two of the great writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman, who stayed with her family to escape the bustle of New York City. This book was signed by Langston and addressed to Mignon’s daughter, Ophelia, in 1937. USHS, catalog no. 1981–048–002.

Award program, Utah Community Services Council, 1970. On this occasion, Mignon was honored for her social welfare service. Throughout her career, she campaigned for anti-poverty legislation, established a school lunch program, and created recreational spaces for minority youth—among many other things. Today, Richmond Park in Salt Lake City is named in her honor. Courtesy of Mignon Richmond family.

Kuniko Muramatsu Terasawa, 1896–1991

Activism can be done in many ways, including quietly. Small, daily acts can bring about change. The everyday work Kuniko did to create the Utah Nippo helped bring together a community, change attitudes about Japanese immigrants, and provide an example of what a woman can achieve.4 Courtesy of Haruko Moriyasu.

The English-language section of Utah Nippo, February 25, 1942. Uneo Terasawa founded Utah Nippo in 1914. After his untimely death in 1939, Kuniko shouldered the responsibility of operating it. She kept the newspaper running amid the turmoil of World War II. It was distributed to all the Japanese detention centers, albeit with heavy censorship from the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Japanese-language manual typewriter, circa 1950. These type sets are an example of what would have been used at Utah Nippo. USHS, catalog no. 1992-110001a.

Back Cover: Kuniko setting type, circa 1990. As her life progressed, Kuniko continued serving her community and publishing Utah Nippo. She was, in turn, honored with several awards and magazine profiles. Courtesy of Haruko Moriyasu.

Ellis Reynolds Shipp, 1847–1939

Health is an important issue for everyone, and Ellis helped to professionalize women’s health care in nineteenth-century Utah. In 1878, she earned her medical degree, becoming one of the first female physicians in Utah; soon thereafter, she established the School of Nursing and Obstetrics in Salt Lake City. Ellis travelled from Canada to Mexico educating on women’s health and treating the medical needs of rural western women and children.5 USHS, photo no. 27187.

Ellis’s anatomical chart, circa 1880. During her career, Ellis delivered more than five thousand babies and trained five hundred women to be midwives. USHS, catalog no. 1983-003-020.

Mae Timbimboo Parry, 1919–2007

Mae always had a notebook nearby to take down stories, and she recorded important dates and events of her tribe for future generations. A dedicated historian and matriarch of the Northwestern Band of Shoshone, she willingly shared her family’s story and Shoshone heritage at schools and community presentations. Mae’s grandfather, Yeager Timbimboo, was one of the few survivors of the 1863 Bear River Massacre. Through her determination, the name Battle of Bear River was changed to Bear River Massacre. 6

Mae Timbimboo Parry, [Shoshone Pictorial Beaded Bag], 1988. Mae was a master beadwork artist who prepared hides using a traditional brain-tanning method. This bag, made of beads on white buckskin, depicts two bison in a meadow with birds overhead. Utah State Folk Arts Collection, accession 1988.16.

Susa Young Gates, 1856–1933

Susa was a strong woman who used her pen as an instrument for change. She was a critical player in several LDS organizations, especially those that involved women’s advancement. A prolific writer, she helped to establish key publications such as the Young Woman’s Journal and the Relief Society Magazine. Susa was a passionate advocate for women’s rights and suffrage, working with prominent national groups and leaders like Susan B. Anthony.7 USHS, photo no. 12328.

This piece by Susa tells at least two stories. The top portion commemorates her parents, Brigham Young and Lucy B. Young, with hairwork made circa 1870. The bottom portion is a card with Gates’s handwriting, noting her donation of it to an early relic hall display. After a prolonged illness, Gates dedicated herself to researching and preserving the history of her people. USHS, catalog no. 1980-013001.

Notes

1. Emmeline B. Wells, Musings and Memories (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1896); Carol Cornwall Madsen, An Advocate for Women: The Public Life of Emmeline B. Wells, 1870–1920 (Provo: Brigham Young University, 2006), and Emmeline B. Wells: An Intimate History (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2017); “Current Topics,” Relief Society Magazine, February 1916, 102.

2. Harriet Horne Arrington, “Alice Merrill Horne: Art Promoter and Early Utah Legislator,” in Worth Their Salt: Notable But Often Unnoted Women of Utah, ed. Colleen Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1996), 171–87; “Utah’s Third Legislature,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican, November 18, 1898, 4; “Women Urged to Campaign Against Smoke Nuisance,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 2, 1936, 11; “Church, Social Leader Succumbs at Hospital,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 8, 1948, 25.

3. Mignon Richmond, interview by David Schoenfeld, August 5, 1974, typescript, MSS A 4051, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah (USHS); Wilfred D. Samuels and David A. Hales, “Wallace Henry Thurman: A Utah Contributor to the Harlem Renaissance,” Utah Historical Quarterly 81, no. 4 (2013): 345–67; Jackie Thompson, “Mignon Barker Richmond, A Community Organizer with Heart,” Better Days 2020, accessed October 28, 2019, utahwomenshistory.org/bios /mignon-barker-richmond/; “Negro Health Week Will Be Observed,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 23, 1934, 24; “U. Dean Discusses Poverty,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 12, 1970, 22; Barbara Springer, “Young, Old Reach for Each Other,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 24, 1971, 21.

4. Haruko T. Moriyasu, “Kuniko Muramatsu Terasawa: Typesetter, Journalist, Publisher,” in Worth Their Salt, 202–217; Helen Z. Papanikolas and Alice Kasai, “Japanese Life in Utah,” in The Peoples of Utah, ed. Helen Z. Papanikolas (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976), 333–62; Miwame Tatai, interview with Paul Kato, November 19, 1975, typescript, MSS A 2817, USHS; “Kuniko Muramatsu Terasawa,” Beehive History 17 (1991): 29–30; “Utah Nippo (newspaper),” Densho Encyclopedia, accessed December 11, 2019, encyclopedia .densho.org.

5. Leonard J. Arrington and Susan Arrington Madsen, Sunbonnet Sisters: True Stories of Mormon Women and Frontier Life (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1984), 126–33; Gail Farr Casterline, “Ellis R. Shipp,” in Sister Saints, ed. Vicky Burgess-Olson (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), 363–81; Ellis Reynolds Shipp, While Others Slept: Autobiography and Journal of Ellis Reynolds Shipp (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962).

6. Mae Timbimboo Parry, interview by Michele Welch, May 2, 2006, transcript, Utah Valley University Digital Collections, accessed December 6, 2019, uvu.content dm.oclc.org/digital/collection/womenswalk/; “Brother and Sister Leaders in Shoshone Indian Affairs,” Hill Top Times (Kaysville, UT), June 13, 1969, 24; Quig Nielsen, “‘Greatest Indian Disaster’ Recanted,” Davis County (UT) Clipper, January 29, 1991, A6; John Barnes, “The Struggle to Control the Past: Commemoration, Memory, and the Bear River Massacre of 1863,” Public Historian 30, no. 1 (2008): 81–104; Darren Parry, “Mae Timbimboo Parry, Historian and Matriarch of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone,” Better Days 2020, accessed December 5, 2019, utahwomenshistory .org/bios/mae-timbimboo-parry/. See also Newell Hart, The Bear River Massacre (Preston, ID: Cache Valley Newsletter Pub. Co., [1983]).

7. Birthday of the Lion House and of Susa Young Gates (n.p., 1926), PAM 8597, USHS; Susa Young Gates, “Suffrage Won by the Mothers of the United States,” Relief Society Magazine, May 1920, 250–76; Annie Wells Cannon, “Birthday Party of Mrs. Susa Young Gates,” Relief Society Magazine, May 1926, 234–36; R. Paul Cracroft, “Susa Young Gates: Her Life and Literary Work” (master’s thesis, Utah State University, 1951).