By Tonya Reiter

By John Sillito

By Alan J. Clark and Henry McAllister

By Tonya Reiter

By John Sillito

By Alan J. Clark and Henry McAllister

By Brandon Plewe

Gary Topping

By Brandon Plewe

Gary Topping

By Tonya Reiter

By John Sillito

By Alan J. Clark and Henry McAllister

By Tonya Reiter

By John Sillito

By Alan J. Clark and Henry McAllister

By Brandon Plewe

Gary Topping

By Brandon Plewe

Gary Topping

77 Railroading Religion

Mormons, Tourists, and the Corporate Spirit of the West

By David WalkerReviewed by Brooke R. LeFevre

78 Frontier Religion

Mormons and America, 1857–1907

By Konden Smith HansenReviewed by Christopher Carroll Smith

79 Wonders of Sand and Stone

A History of Utah’s National Parks and Monuments

By Frederick H. SwansonReviewed by Angela Sirna

80 John Hance

The Life, Lies, and Legend of Grand Canyon’s Greatest Storyteller

By Shane MurphyReviewed by Frederick H. Swenson

82 Watchman on the Tower

Ezra Taft Benson and the Making of the Mormon Right

By Matthew L. HarrisReviewed by Joseph R. Stuart

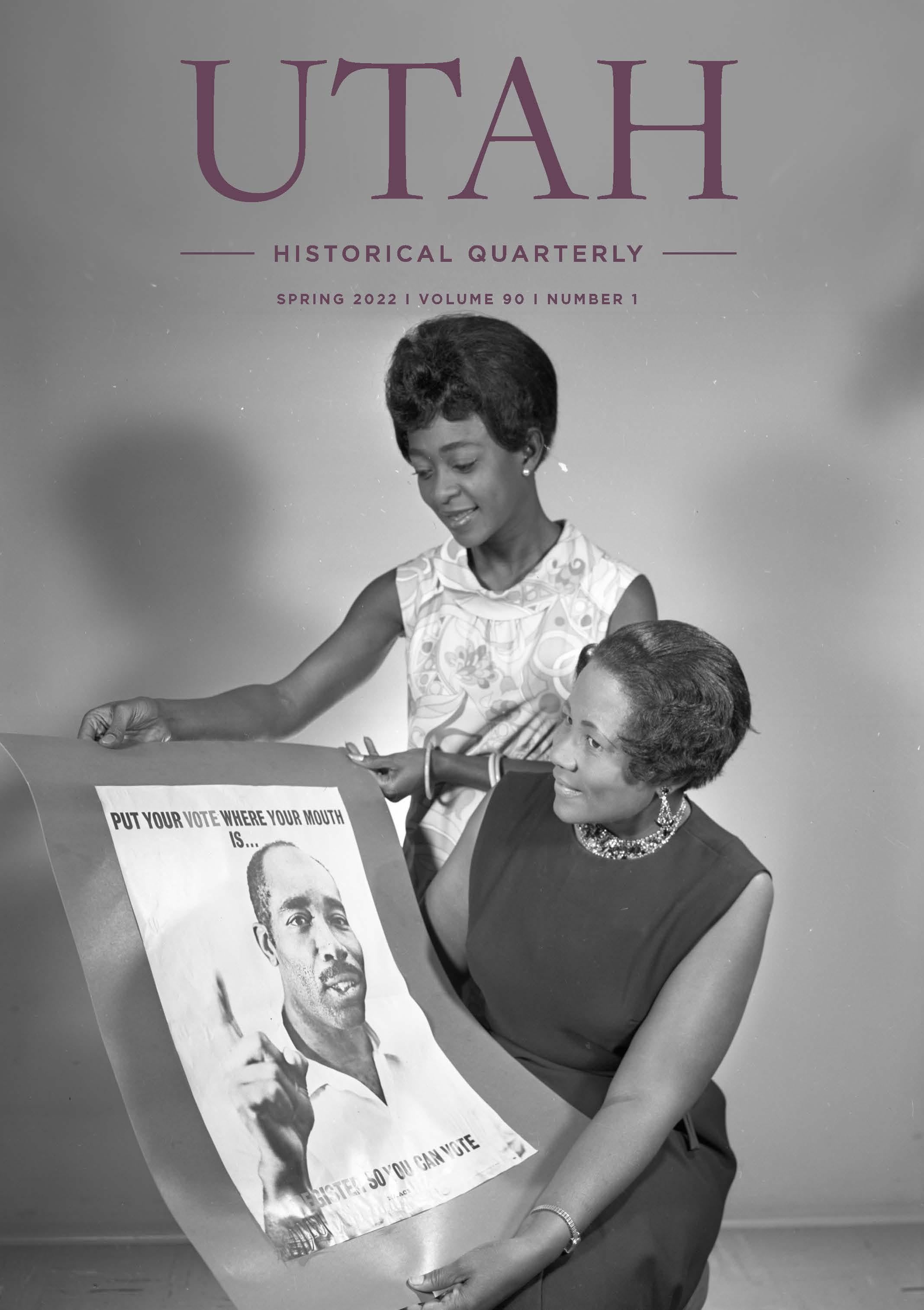

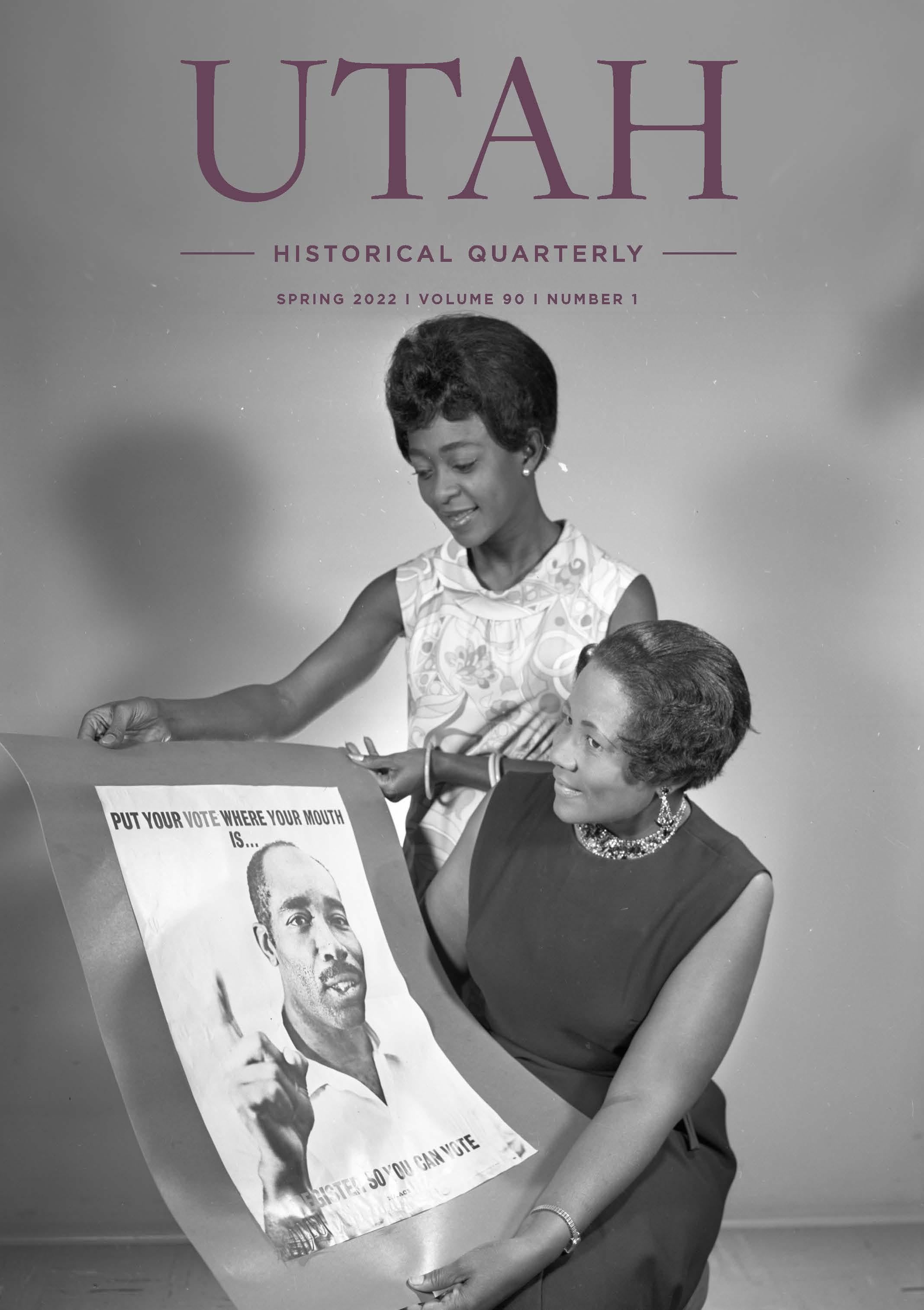

Two years ago—in the winter 2020 edition of Utah Historical Quarterly—we published a series of essays addressing race and religion in twentieth-century Utah. As we shared with readers then, we had not planned a thematically orchestrated issue. Beholden to the historical research submitted to our editorial office, we often look for ways to group like articles, and sometimes the results pleasantly surprise us. Like the winter 2020 issue, the edition before you continues the conversation about the African American experience in Utah.

However serendipitous may be the configuration of articles in the current issue, both social and academic trends likely account for heightened attention to racial and ethnic communities here in Utah and nationally. In legislative halls, classrooms, and public discourse, we collectively question socioeconomic disparities between racial groups, unequal representation in public institutions, healthcare access and public health outcomes, educational opportunities, and a host of other issues faced by people of color. Where do social and cultural disparities come from, and how are they perpetuated? How have individuals from underrepresented communities created for themselves spaces where they can act out their own futures? How have individuals and institutions historically responded to voices and acts of protest? Although not new, such questions challenge us to consider anew the forces of history that create the world we inhabit. This edition of UHQ contributes to an understanding of pressing questions and issues, primarily concerning race, that we care about today.

We lead out with Tonya Reiter’s history of an ofttold, 1939 attempt by white residents of Salt Lake City to establish a segregated “Negro district” outside the boundaries of their own neighborhood—the spurious action of unsubstantiated rumors. Although Salt Lake City did not then formalize de jure segregation in housing, de facto segregation and racially discriminatory

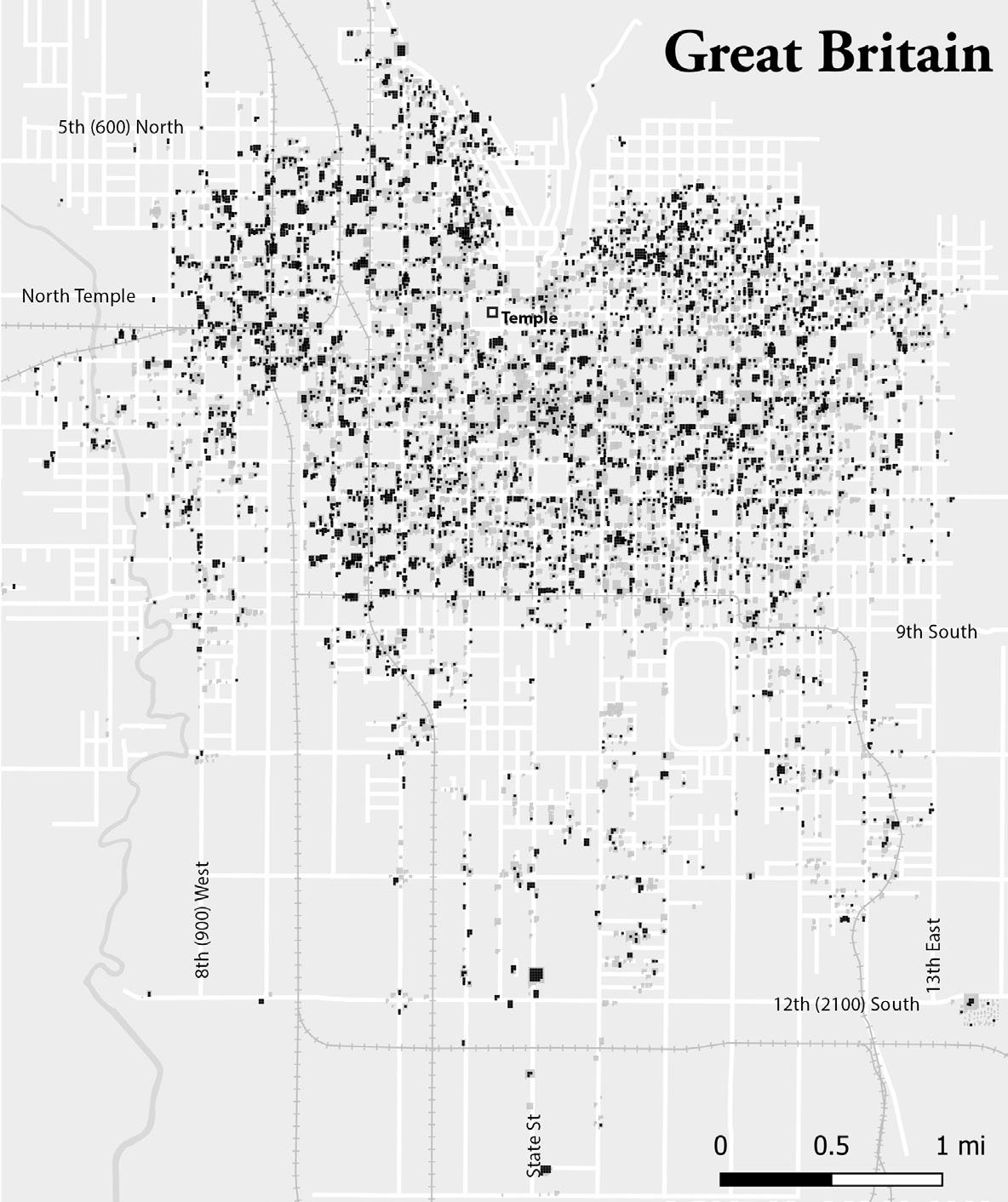

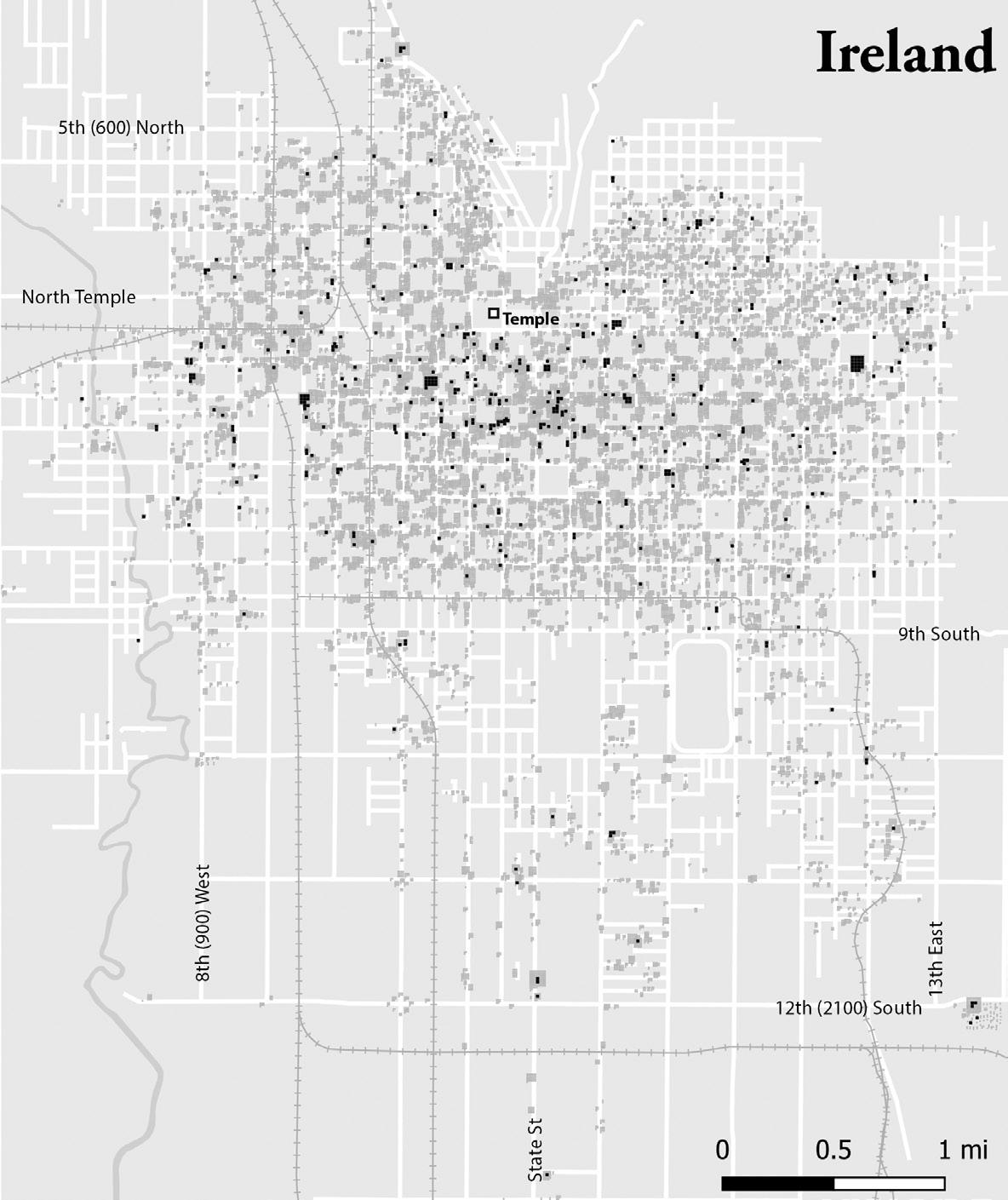

practices that preserved white property values at the expense of Black citizens—like those written in real estate codes—were prevalent at midcentury. We live today under the shadow of such practices, if one compares neighborhood demographics and property values. As we see from the findings of another essay in this issue, these disparities go back decades. Based on data from the 1900 US census, Brandon Plewe’s spatial analysis of ethnic groups in Salt Lake City at the turn of the twentieth century underscores the decisions and forces acting on immigrants arriving in an increasingly diverse urban city.

We also feature the quixotic campaign in Utah of Henry Wallace, the liberal former-vice-president-turned-third-party candidate who spoke assiduously for the kind of progressive policies advocated by some on the left today. As thoroughly detailed by John Sillito, the Wallace candidacy animated a core group of supporters, concentrated in the universities, concerned about social justice and civil rights.

Our next piece is a history of the prominent Pentecostal church, the Church of God in Christ, by Alan J. Clark and one of its pastors, Henry McAllister. While some readers may know something about the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Church in God in Christ and its long struggle to carve a place for itself primarily in Salt Lake City and Ogden finally gets attention in the pages of our journal.

A group of professors and students at Brigham Young University is currently working to encourage amends for their institution’s connection to slavery and racial discrimination. Grace Soelberg’s essay, our fifth, is one perspective among a multitude of others on applying the weight of history to address contemporary concerns.

Finally, we close the issue with Gary Topping’s homage to D. Michael Quinn, a prolific scholar and friend to many.

In the fall of 1939, a large group of residents living in one of Salt Lake City’s central areas, a part of the larger Sumner neighborhood, reacted to a rumored petition that requested a zoning change to create a “negro residential zone” in their part of town and encourage more Black families from outside Utah to relocate there.1 These residents did not name the plan’s proponents, nor is it possible to be certain, even now, who might have suggested Salt Lake City segregate housing. At the time, the protesters insisted that an unnamed group of Black people were responsible for the petition asking for the zoning change. It is possible the Sumner residents and property owners may have learned about a new federal housing program under investigation in Ogden, Utah where members of that Black community had proposed that it be sponsored by the city.2 They could have been aware that if sponsored by Salt Lake City, a federal program would change their neighborhood and bring more low-income residents into their area. These predominantly white residents of the Sumner neighborhood, under the leadership of Sheldon Brewster, reacted to the rumored petition by drafting their own petition to the Salt Lake City commission asking city officials to comply with three demands; the most controversial of which was that their neighborhood be spared and some other part of town be zoned as a Black district.3 The NAACP responded to the petition’s call for a racial housing zone by voicing its members’ opposition to segregation. In addition, an ad hoc group of Black Salt Lake Valley residents, including Mary Lucile Perkins Bankhead, gathered at the City and County Building to assert their constitutional right to own property and live in any part of town. Lucile Bankhead’s retelling of the story of the proposed segregated district and the response of the wider Black community was central to keeping the memory of this event alive.

This episode in the story of Utah’s race relations has been recounted many times, but not fully, and often with misremembered and inaccurate details. The most recent version published and many older retellings set

the Black protest at the Utah State Capitol.4 However, this was an issue proposed and debated at the city level, despite the leader of the Sumner neighborhood group, Sheldon Brewster, being a member of the Utah State House of Representatives.

From newspaper articles, city commission records, transcriptions of the 1939 petition, and later oral histories, it is possible to draw a more complete picture of what took place, correct the historical record, and illustrate how city officials responded to the competing demands of their constituents. Rumor, fear, and misunderstanding each played a part as citizens on both sides of the color line tested the limits of the power of local officials to control city housing based on racial identity.

On Wednesday, November 1, 1939, “an overflow crowd” of more than one thousand property

owners and residents of central Salt Lake City “jammed the Sumner School auditorium” to protest a rumored petition for a “negro residential zone” that, if granted, would be formed between 600 and 900 South Streets, bounded by Main and 500 East Streets.5 The organizers of the meeting, who owned real estate in the neighborhood, “summoned” other property owners by door-to-door canvassing and distributing printed circulars. Local resident Sheldon Riser Brewster took charge of the meeting and was chosen by the group to head a committee authorized to meet with “representatives of the negroes and attempt to work out an amicable agreement for establishing a special zone elsewhere in the city,” as well as meet with the city commission to protest the currently proposed district.6

A seven-person committee representing the Sumner residents drafted a petition and

presented it to Mayor John M. Wallace and the city commission. Petition No. 1133 called for “relief from a condition” that they found intolerable. More than one thousand signatories attested to problems associated with an “influx of Negroes,” the most egregious of which, according to the white residents who addressed the Sumner School gathering, was the depreciation of property values.7 The petitioners recommended three remedies, which the city commissioners considered:

1. Order the immediate closing and disposal of the social club known as the High Marine Club.

2. Deny the zoning of our district, either officially or unofficially as a Negro District.

3. Appoint a committee to investigate the Negro problem as it exists in Salt Lake City, who will learn how the matter has been handled in other cities, and establish a district where the needs of the Negroes can be agreeably supplied.8

Sheldon Brewster was a natural choice to head the committee created by the neighborhood protesters. The section of town under dispute lay mostly within the boundaries of the Salt Lake City Third Ward of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which consisted of a nine-block area. Brewster was the bishop of that ward in 1939. Not only was he an ecclesiastical leader, he was a community organizer and had been a Democratic member of the Utah House of Representatives since 1936. He served in that position until 1942. Given his experience, he was well-acquainted with the workings of local and church government. In addition to his active political involvement, he was a real estate investor, owning apartments and later a motel. He served as an officer in the Salt Lake Executives Association.9 His interest in central Salt Lake City grew out of his own experiences living there in the 1920s and 1930s and his desire to see what, in his opinion, had been one of the city’s nicest neighborhoods restored and beautified.

Brewster was interviewed for an oral history in 1974, in which he shared his memories

of the events of 1939, his view of his former neighborhood, and his beliefs about urban renewal.10 Brewster spoke about the apartment building he built and occupied from 1924 to 1961, located at 851 South 200 East, and his love for the area and its historical importance: “There were a lot of other historic homes, beautiful homes, some of the wealthy people of the city lived in the area. Then later they, as they died, or their children moved elsewhere, it became a rental area and was really starting to run down. . . . We formed an organization called the Central Civic and Beautification League . . . for the purpose of preserving the area as a residential area.”11 Brewster explained that although banks considered the central part of the city to be blighted and the city planned to turn the area into a manufacturing and industrial center, as homeowners and renters improved their properties, they were able to convince the city to retain residential zoning. Therefore, the banks became more willing to lend money for home remodels and improvements.12 What began as an effort for conservation and renewal took on a racially biased aspect in 1939, despite the neighborhood’s diverse character.

The central area of the city designated by the petitioners was part of Salt Lake City Municipal Ward 1, as enumerated in the 1940 US Census. Wanda Steffenson, the census taker, went beyond what she was required to do in documenting the races of residents and recorded the ethnicities of everyone in the neighborhood, giving us a very clear picture of the makeup of this particular locale. Of the 191 households she listed, ten were Greek or Mediterranean, four were Jewish, including several Russian Jewish households, two were Hispanic, and three were Black. So although the neighborhood was dominated by white northern European and English descendants, it included residents of other ethnicities. In his oral history, Brewster remembered that there had always been Black families living in this central city area: “We had a few Negroes in the area, they were nice people. They had been there, one family of Negroes came into the area with the pioneers. It was the servants of the prophet Joseph Smith and they lived in the area and then others came in. Nobody objected to them at all. Got along with them, they with us.”13

Since its founding in 1847, Salt Lake City had always supported a small population of Black residents. Three enslaved Black men had been part of the advance party of Mormon pioneers and descendants of early Black settlers had long farmed southeast of downtown in Mill Creek and Union. Many of these Black Utahns had Mormon heritage, and some of their progeny still retained membership in the LDS church. History shows they were hard-working and more or less integrated into their white Mormon communities.14 In 1886, with the arrival of the US Army’s Twenty-fourth Infantry, the Black population of Utah rose significantly, and for a few decades a small Black community supported its own newspapers as well as political, social, fraternal, and religious organizations.15 Despite the flowering of Black associations and businesses in the early 1900s and the fact that Salt Lake City’s population had nearly doubled between 1900 and 1930, Black residents were still few and far between. By the time the 1930 US Census was enumerated, only 1,108 Black residents were counted in all of Utah, making up only 0.02 percent of the population.16 The older Black families were a known quantity. Many shared a history and religious values with white LDS residents. It is obvious, however, from the number of people who attended the meeting at the Sumner School, the reports printed in the local papers, and especially the strong language used in Petition No. 1133 that white homeowners felt a high level of fear about what they saw as an outside threat entering their neighborhood.

Attendees at the mass meeting on November 1, 1939, who addressed the gathering maintained that an unnamed group of Black people were “circulating a petition to have the area designated by the city zoning commission as a negro residential zone.” They asserted that property values had already suffered because of an “influx of negroes.”17 Brewster believed that soon more would be moving into their neighborhood. The Salt Lake Herald reported him saying that “an influx of members of the race” was imminent and that “certain interests” were “attempting to buy and rent a group of houses for them.”18

The seven-member committee formed on November 1 consisted of Sheldon Brewster

as chair, Mrs. Roy Bowman, Mrs. Ollie J. Sinclair, R. H. Siddoway, Thomas Sawyer, Mrs. A. C. Lund, Colonel Elmer Johnson, and Leon F. McAllister.19 They “pledged to protest against the creation of a negro residential district” in their neighborhood.20 By November 16, Brewster and his committee had drafted Petition No. 1133 with its three main requests and had garnered the signatures of 1,000 property owners and residents. The first demand on the petition was the closing of a social club, the High Marine Club. The High Marine Lodge No. 12 of Free and Accepted Masons, a Black fraternal organization, had been chartered on September 12, 1893, in Salt Lake City. Black soldiers stationed at Fort Douglas were members, as was W. W. Taylor, the editor of the newspaper The Plain Dealer. 21 The Masons of the High Marine Lodge had planned to build a lodge at 523 South 200 East. They purchased the lot in 1922. By July 1929 an architect was drafting a plan for the new two-story structure, expected to cost $35,000 to $40,000.22 The next month, seventy-five local residents signed a petition protesting the construction of the lodge building on the grounds that it would be used as a “dance resort and would be detrimental to the moral and social welfare of the district.”23 The plans for the new building were then scrapped, and beginning in 1930, the lodge began meeting at 176 East 700 South.

Often referred to as the High Marine Hall, the building on Seventh South served as a meeting place for various types of events. In the 1930s the Salt Lake Chapter of the NAACP met there. During National Negro History Week in February 1939, the opening lectures took place there. Seeking support from the Black community, politicians rallied there. Evidently the on-site manager of the hall, John J. Jordan, also hosted more informal social events. Although the Polk Directory until 1940 listed 176 East 700 South as the address of the Masonic Lodge, when white neighbors lodged complaints about the noisy goings-on at that location, they referred to it as the High Marine Social Club. The hall could have served a dual purpose late in the 1930s and into the early 1940s.

Petition No. 1133 complained of the “unpleasant conditions aggravated as a result of . . . the High Marine Club. . White women and girls that

walk past this place after dark are constantly being accosted and insulted by Negroes. . . . [T] he continuous proceedings of this place are a disgrace to our city. If such a place is to be tolerated it certainly should be away from decent citizens.” One important point of friction could have been the hall’s proximity to the Salt Lake Third Ward meetinghouse on the same block, just across 700 South.

This was not the first time the Salt Lake City Commission had received a petition complaining about the High Marine Social Club. On August 17, 1939, Mrs. B. Gallion, who lived on the same block as the hall, submitted a petition signed by more than one hundred people that alleged “boisterous conduct” and car horn honking late into the night. The city commission referred the complaint to the public safety department.24

The second request put forth in Petition No. 1133 asked the city commission to deny the zoning of the central city neighborhood as a “Negro district.” The petitioners laid out their reasoning in terms of the proposed district’s location.

This district, which is in the very heart of Salt Lake City, in the shadow of the City and County Building could be and should be one of the most attractive and valuable parts of the City. . . . We recognize the citizenship and constitutional rights of the Negro. It is not our purpose to persecute or abuse him. But neither do we intend to stand idly by and see less than five hundred Negroes confiscate a district which is inhabited by more than five thousand whites. Do we want the thousands of tourists who come to our city each year to pass through a “Negro District”? And do we want our visitors in 1947 to find that the Negroes have taken over the center of Salt Lake City?”25

R. H. Siddoway, a member of Brewster’s committee, told a Tribune reporter, “We agree that a residential district for colored persons should be established, but we object to the area of the proposed district. It may take some time to iron out difficulties and reach an agreement, but I believe the matter can be worked out to everyone’s satisfaction.”26

As it turned out, many Black Salt Lakers were not satisfied with the concept of a segregated neighborhood, no matter where it might be located. When the NAACP members learned of their neighbors’ intentions, their organization passed a resolution that appeared in the Deseret News on Wednesday, November 8, 1939. It stated that “whereas the people of Salt Lake and vicinity have been informed through the press and otherwise that the negro people favor the segregated district, we the members of the Salt Lake branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People declare that this is not the fact and we wish to go on record that this segregated district is not the wish of the negro people and anyone requesting a segregated district is acting without the authority of the negro people.”27 Two days later, an article in the Salt Lake Tribune listed newly elected officers of the NAACP Salt Lake Branch and published a slightly different version of their resolution with an important distinction; “negro people” was changed to “negro citizens.”28 Among the elected officers of the local NAACP were Harmon O. Cole Jr. and Minnie Williams Cole, who lived a few blocks south of the Brewsters and the protesting Sumner homeowners—Harmon as chair of the executive board, Minnie as president. Harmon was also a former grandmaster of the High Marine Masonic Lodge.

Not all white Salt Lakers agreed with the central city protesters, either. A notice of an open forum scheduled on November 8, appeared just below the article listing new NAACP officers. A group called the Utah Conference for Human Relations proposed a discussion of “civil rights of racial groups.” The subject for the forum was chosen, “a recent proposal for residential zoning of negroes in Salt Lake City.” Two speakers, both white, were slated to present their views on the civil liberties of the “negro group” and other “racial minorities,” followed by D. H. Oliver, one of Utah’s early Black attorneys who planned to talk about the Bill of Rights.29

The NAACP assumed the right to represent the Black community of Salt Lake City, and it is clear from their resolution that their members were not party to any circulating petition for a segregated residential neighborhood. The question remains whether any other groups or individuals were behind the petition, or whether such claims were just unsubstantiated rumors?

The third recommendation made by the Sumner petitioners was that a committee be appointed to study “the Negro problem” and establish a segregated residential district to accommodate them. As they drafted Petition No. 1133, the writers invoked the memory of Salt Lake City’s Latter-day Saint founders as they advised city officials: “The matter of zoning a district for them will eventually have to be met. Why not have some of the wisdom and foresight of our pioneers by facing the issue now.” 30 The petitioners alleged, “We know that additional members of the race are planning to make Salt Lake City their home. We understand that twenty-five . . . families are being urged to move from Ogden to this City.” 31

For Sheldon Brewster, these twenty-five families were only the tip of the iceberg. He believed there was a larger plan in place. Over

thirty years later, he explained some of what he and his neighbors objected to in 1939:

There was a movement on in the South to move a lot of the Southern negroes to the North. . . . The alarming thing . . . was the fact that word had come that they were going to bring a large group of them to Salt Lake and wanted to obtain that area [central city] for settlement in. That was the thing . . . none of us wanted because you didn’t want it to become any particular area just a nice residential area for everybody. So we went up to the city commission . a lot of it was misunderstood. Some of them thought it was a fight against the negro people. It was a fight against them establishing it as a negro area. Which, of course, with integration it’s not supposed to be centralized in one area.

We went to the city commission and we said, ‘We don’t have any objection whatever of the negroes wanting an area . . . but no one should come from the outside.’ It wasn’t local negroes, it was an outside movement, you see. It didn’t interfere with the negroes who were there.32

At the time of his oral history in 1974, Brewster seemed anxious to explain away any bigotry that had attached itself to his earlier efforts by stating his appreciation for the Black Mormon families living in downtown Salt Lake City and attempting to distance them from what he characterized as outsiders whose culture clashed with LDS Utah culture. In fact, the language of Petition No. 1133 was inflammatory and derogatory toward members of the Black community. It listed the “evils” caused by an “influx of Negroes.” The petitioners claimed that Blacks “confiscate” the districts they “invade” and that “Colonization” of the neighborhood had resulted in “unpleasant conditions” being “aggravated.” As noted earlier, the number of Black residents in Utah had actually gone down from 1920 to 1939, so there really was no “influx.” It seems much of this language really referred to the High Marine Hall drawing people of color into the neighborhood.

The commission, which received the petition on November 7, agreed to hold a hearing dealing with the complaints and recommendations set forth by the Sumner petitioners the following week at its regularly scheduled meeting. At the same time, two interested parties filed their own petitions to oppose Petition No. 1133: Petition Nos. 1151 and 1152. Neither of these documents is extant. One was apparently filed by Helen Dennis, chair of the executive committee of the Utah Conference for Human Relations, the same organization that hosted the civil rights discussion earlier in the month. According to the Deseret News, this petition asked that the commission take no action to segregate Black residents or distinguish them from their white neighbors.33 The Salt Lake Telegram reported that she and two University of Utah professors appeared before the commission and spoke against segregation, condemning it on ethical and scientific grounds.34 The other petition was filed by Reverend Lilly who represented the Salt Lake Ministerial Association. Both

Dennis and Lilly asked the city commission to notify them if there was to be a hearing.35

On the day of the hearing, November 21, 1939, the city recorder’s official record of the meeting reported, “A group of persons were present in behalf of petition #1133 by Sheldon Brewster, et. al. representing property and residents in the territory between 5th and 9th So. and Main and 6th East St. complaining of the invasion of negroes in this section and asking the City to a [sic] zone or restrict the use of this property. Mayor Wallace announced that the City has not and does not intend to set aside any section of the City for the use of negroes and that the City Commission had not officially or unofficially taken any steps to set aside a negro district.”36 Regardless of this clarification, the petitioners pressed their desire for a segregated black housing district: “Mr. Brewster, Mrs. O. J. Sinclair . . . spoke stating that they were in favor of zoning or setting aside of some district for negroes as they have done in other cities and that they object to their neighborhood being invaded.”37

Salt Lake City Commission minutes do not list everyone in attendance at the hearing for Petition No. 1133, but the Deseret News reported that the commission chambers were “packed with negro residents of the district.”38 The story of their protest and effort to kill the proposed segregated district lives on thanks to Mary Lucile Perkins Bankhead and her retelling of the event. It has become something of a legend in Utah’s Black community.

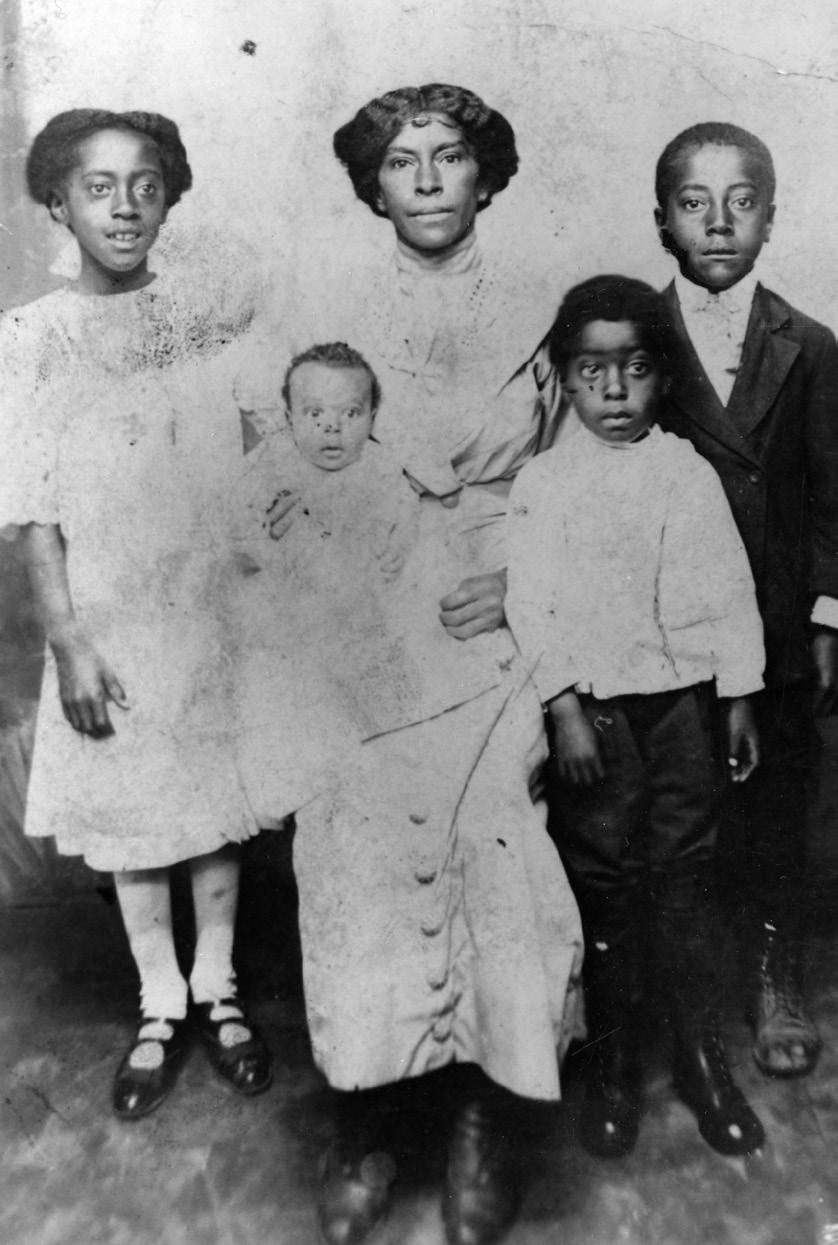

Bankhead was the direct descendant of Black Utah Mormon pioneers. Her mother was the granddaughter of Green Flake, an enslaved Latter-day Saint who came to Utah with Brigham Young’s advance party and became a property owner and miner after his emancipation. Bankhead’s father was the son of Frank Perkins, another enslaved Mormon brought into Utah, who has many descendants in the state and in the West. Lucile was a devoted Latter-day Saint all her life and became the first Black Relief Society president in the church when Genesis, a church-sponsored support group for Black Mormons, was created in 1971. She lived all her life in Mill Creek, about eight miles southeast of downtown Salt Lake City, where her father and many relatives farmed. In 1939, Bankhead

and members of her sewing club, the Camellia Arts Club, got wind of a plan to create a housing district for all of the Salt Lake Valley’s Black families. Opposed to the idea, they decided to voice their opposition to government officials. As detailed in a 1983 interview, Bankhead, with Alice Weaver Leggroan and three or four other women, “took a horse and wagon and we went up to the legislature and we sit there all day. ‘Course I was the one that did the talking. . . . I said we had no intention of selling our property and it was all clear, no taxes due, so what could you do about it? And we hit . . . so hard ‘til the newspaper got on it.”39 Remembering the event more than forty years later, Bankhead’s memory was, understandably, not entirely accurate. The zoning question was debated in the chambers of the Salt Lake City commission in the City and County Building, not the Utah State Capitol. The fact that Sheldon Brewster was a Utah state legislator likely added to the confusion.

Undoubtedly, Bankhead and the other members of the Camellia Arts Club were among the seventy-five Black protestors who packed the commission chambers on Tuesday, November 21. In retrospect, Bankhead realized the sensation they must have caused because even though most of the women dressed up to protest, “Mrs. Leggroan had on a big white apron . and a white dust cap.” Some of them had young children in tow. “We took our lunch and took the basket for the baby to sleep in after he was nursed and stayed all day long and I guess they was glad to get that crowd out of there when they got through. . . . I have to laugh about it. But we were really kind of mad. . . . [The commissioners] didn’t want us sitting up there all day.”40 Bankhead’s home was on land her family had owned since the nineteenth century, and she had no intention of letting anyone force her off it and make her relocate to a downtown neighborhood. “It’s been a hundred years that we’ve owned this place . and we’re still on it,” she explained.41

Bankhead’s comment about her desire to retain her familial inheritance begs a question. Her home was in Mill Creek, in Salt Lake County, outside the boundaries of the city and several miles from the neighborhood in question. While the city’s zoning powers did not extend into the county where Bankhead lived, she made assertions in her oral history that bear closer investigation and give hints as to what might have prompted Brewster and his neighbors to create their petition in the first place.

When asked by her interviewer about “that thing that happened in ’39,” Lucile Bankhead made it clear that at the time she believed the proposal was to create a Black residential district near 700 South and 200 East, downtown, and force all Black Salt Lake Valley residents to move there. She did not name the person responsible for the idea, but she told how she learned about it. One of her Mill Creek neighbors, a man she was related to through marriage, acted as an agent for an unknown person to obtain the support of members of the Black community, “We had a Black man helping him out . . . [and] he came to this meeting. The first thing we knew about it was the Black man telling us, did we want to sell our places? Come out to ask if we didn’t want to sell our homes. He had offered him money, if he could get us to sell[,] and then he told this story about him saying it would be best for all Blacks to be on 7th South. . [T]hat’s what they wanted us to do. He tried to get us to move up there. . . . It’s funny what people will do for money.”42

Looking back at this episode, some scholars have concluded that Sheldon Brewster was the unnamed person who wanted to restrict Black housing to the central city location, but by his own admission he and his neighbors petitioned the city commission to ensure that did not happen. It is evident by their petition and local newspaper reports that the Sumner neighborhood residents were in favor of segregating Black residents of Salt Lake City in a dedicated neighborhood, but they were also clear about not wanting it to be in the central city area where they lived. If Bankhead’s retelling is correct, her version agrees with the petitioners’ claim that some other group first suggested that part of the Sumner neighborhood be zoned for a segregated residential area

in which all Black Salt Lake County residents would be forced to reside.

Oddly enough, city commission minutes related that Brewster, Sinclair, and a “Mr. Oliver” spoke in favor of zoning “some district for negroes.”43 There was no “Mr. Oliver” named as part of the Sumner School committee, but D. H. Oliver is listed as an attendee of the city commission hearing. David Herbert Oliver was originally from Oakwood, Texas, and, after graduating from the University of Nebraska law school, practiced law for five years in Omaha. He relocated to Ogden in 1930 and passed the Utah state bar.44 Oliver’s name often appears in Salt Lake City and Ogden newspapers in connection with his legal cases and work as a defender of Black civil liberties.45 In 1939 Oliver was the president of the Utah Council of the National Negro Congress, a more politically radical organization than the NAACP.46 In its coverage of the November 21, 1939, meeting, after naming the Sumner School committee members, the Deseret News reported that “D. H. Oliver, negro attorney, told the commission he had come to represent this group but added that since a committee was appointed to investigate, he would appear before the committee.”47 No other information sheds light on Oliver’s involvement. What “group” Oliver intended to represent is not clear. If it was the group of Black residents assembled to voice opposition to the petition, Oliver must have realized his views ran counter to theirs. It is possible the city recorder mistakenly called one of the Sumner neighborhood petitioners “Mr. Oliver.” Or it is also possible that Oliver and Louis Leggroan, the man Bankhead named, stood in opposition to the wishes of the majority of the Black community as represented by the NAACP.

During the course of the commission hearing, the Sumner petitioners pressed their grievances against the High Marine Club and accused Jordan, the manager of the club, of selling hard liquor on the premises. Jordan responded that he had been the manager for three years and had never sold any on site.48 At the conclusion of the hearing, having listened to the grievances of the white residents and registering the counter-protests of the Black community, Mayor John Wallace decided to send the “question” to the city’s legal department with a request

that they attend to it and give an answer as soon as possible.

This was not the first time Utah residents tried to circumscribe Black housing to specially zoned areas. Earlier in 1939, white property owners in Ogden had attempted to prevent a Black family from renting a home in an allwhite neighborhood. Since the Deseret News reported the attempt on February 3, 1939, some Salt Lake City residents may have been aware of it.49 Minutes of the Ogden Board of Commissioners contain limited records of the tussle between a homeowner and her neighbors, but the Ogden Standard-Examiner reported the story in more detail. In its issue of February 2, 1939, the newspaper described “sharp words” exchanged at a city commissioners meeting over whether Edna G. Heflen could rent a home she owned on Patterson Avenue to a young Black couple and their baby. Eighty residents along Patterson Avenue had signed a petition addressed to the city board alleging that the “presence of the Negroes would depreciate property values.” Heflen argued that she was a widow and needed to rent the property to support her family and pay taxes. She also told the commissioners that the prospective renters were “intelligent . . . respectable, self-supporting American citizens,” and she asked, “Can you deny them equal rights?” Heflen believed the Black family’s presence would not lower property values. She said she resented the publicity over the rental and accused a city commissioner, who lived on Patterson Avenue, of being responsible for the petition. He heatedly denied her allegation but said he intended to go to the defense of his neighbors.50 The commissioners “instructed” the Ogden city attorney, George S. Barker, to “prepare an ordinance prohibiting Negro families from residing in certain sections of the city.”51

The demands for limiting Black housing in Ogden continued into the summer of that year. In July, four hundred residents along Ogden’s east bench asked for a new zoning ordinance to prohibit “the spread of Negro families through the municipal Fourth ward.” Again, the action was based on property values and the fear that the presence of Black residents would so depreciate home values that owners would see “the savings of our lifetime practically wiped

out.” The white homeowners, on this occasion, reacted to a change in railroad practice. Many Black train employees, porters and cooks, had been transferred from Omaha, Nebraska to Ogden. After arriving in Utah, they found it difficult to find “suitable” housing. As reported in the local newspaper, “railroad employees complained their present homes, located in the immediate area of railroad tracks, were unsanitary, crowded, and undesirable.”52

John R. Braggs, a member of a dining car waiters union, wrote a letter to the editor of the Ogden Standard-Examiner that appeared in the issue of July 14, 1939. “On behalf of the Negro citizens of Ogden, and the membership” of his organization, he replied to the July petition to bar Black people from renting or buying homes east of Washington Avenue. He quoted the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and asserted that the petitioners must not have ever read the document. He also urged Black families to exercise their constitutional rights and look for homes available due to foreclosures. “The United States government will accept money from black, as well as white Americans,” he advised.53

The reportage on the efforts to zone Ogden neighborhoods based on race, as well as the minutes of the Ogden Board of Commissioners meeting, mention something that bears on the protests over central Salt Lake City, sheds light on Lucile Bankhead’s understanding of the “Black district” proposal, and helps to explain Sheldon Brewster’s fear of outside influence. The Ogden Board of Commissioners meeting minutes of February 2 and the Ogden Standard-Examiner report that “the board accepted an offer of A. B. Paulson of Salt Lake City, member of a housing committee which proposes to provide moderately-priced homes through a federal project, to explain the proposal before a commission meeting next week.” Paulson explained, “‘I am well acquainted with the slum clearance problem in Utah in relation to the U. S. housing project.’ A bill is now before the Utah legislature, proposing to place the state in line to participate in the federal housing program.”54 Paulson served on a housing committee in Salt Lake City. The Deseret News added, “A plan proposed several weeks ago by Negro residents whereby a federal housing project

would be sponsored by the city is being investigated.”55 On February 7, Paulson, an architect, and others appeared before the Ogden Board of Commissioners to explain “in detail the United States Housing Administration” and its programs.56

It seems likely that Brewster, as a member of the Utah House of Representatives, would have known about this proposed legislation. House Bill No. 96 of 1939 outlined creation of a local housing authority to oversee the use of federal money to “clear slums” and build low-income housing in cities with a population over three thousand.57 The discussions and debates regarding the passage of the bill could very well be the source of Brewster’s impression that more Black families would be relocating to Salt Lake City. It is also possible that some Salt Lake City Black residents were in favor of their city, like Ogden, sponsoring a housing project in the heart of downtown. Brewster was not a proponent of later urban renewal programs. In his 1974 oral history, he argued that such renewal programs often called for historic structures to be leveled rather than restored, and as a preservationist he did not approve of that approach.58 Even earlier Brewster had clearly expressed his feeling that federal housing programs clashed with property rights and did not accomplish their stated goals. In an open letter he penned to his fellow democrats in the Utah House of Representatives, likely around 1959, he wrote:

[T]he idea of Public Housing came into existence and spread rapidly . . . because of its high sounding aims.

[In 1949] planners saw that public housing was not eliminating slums, so a new feature was conceived of “slum clearance” which has been given various names such as community redevelopment, urban renewal etc. . . . They [slums] have just been moved and new slums have even been created by the very program which proposed to eliminate them. . . . I was Bishop for 18 years in an area which is in the “plan” to be bulldozed out of existence. What will replace it? That isn’t planned yet, but it won’t be the people who are there now. They are buying and renting homes which fit

their economy. It is one of the most integrated parts of the city and there have been no serious race problems. They feel their property rights are just as sacred as anyone’s.59

Brewster based his objections to the housing programs of the New Deal and later urban renewal plans on the same principles.

The Ogden imbroglio might also shed light on why Brewster maintained that twenty-five Black families would be settled in Salt Lake City. Perhaps he had railroad employees in mind. It is difficult to know with certainty the source of the information that so alarmed the Sumner neighborhood residents and prompted their appeal to the city commission, but it is reasonable to draw a connection between the events in Ogden and what developed there.

The Salt Lake City Law Department gave its ruling on the demands of Petition No. 1133 to Mayor Wallace and the city commission in early 1940. On February 21, Salt Lake City Attorney Fisher Harris told the commission that “the results sought by Petition No. 1133 are beyond your power to accomplish and beyond your jurisdiction to influence.” Harris’s ruling echoed the earlier sentiments of Ogden railroad waiter John Braggs. The attorney cited the Fourteenth Amendment to inform his opinion of what the commission could legally do. Harris quoted, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States, nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law; nor deprive any person within its jurisdiction of the equal protection of the laws.” He asserted that “while the principal original purpose of this amendment was to protect persons of color, it has more frequently been invoked by others, and the broad language used has been uniformly held by the courts, both state and federal, to protect all persons, regardless of race, creed or complexion, against discriminatory legislation and governmental action, of every nature. Such is that sought, or at least suggested, to be induced by this petition.” After denying the petitioners a governmental or legal resolution of the conflict, he suggested another course of action: “If there is any remedy for the conditions complained of, it lies within the field of social cooperation

rather than in that of governmental action.”60 This was a somewhat recent application of the Fourteenth Amendment. The first time it was cited by the Supreme Court to strike down a local racial housing ordinance was in Buchanan vs. Wardley in 1917. The majority opinion stated that legislation to separate the races “must have its limitations, and cannot be sustained where the exercise of authority exceeds the restraints of the Constitution.”61

The 1939 attempts in Ogden and Salt Lake City to form legally zoned racial housing areas failed, but real estate contracts and covenants essentially segregated neighborhoods before and after this time. In two of Utah’s largest cities, real estate developers and agents used extralegal methods to attempt to maintain allwhite enclaves. In the Salt Lake City neighborhood of Highland Park, begun in 1909, Kimball and Richards planned to limit sales in their new subdivision to white residents only. They advertised the Highland Park restrictive covenants as a selling point in the Salt Lake Tribune. On January 19, 1919, the firm stated that this new neighborhood housed “only members of the Caucasian Race.” Ad copy informed prospective buyers that the building regulations included a provision that “the buyer agrees that no estate . . . shall be sold, transferred or

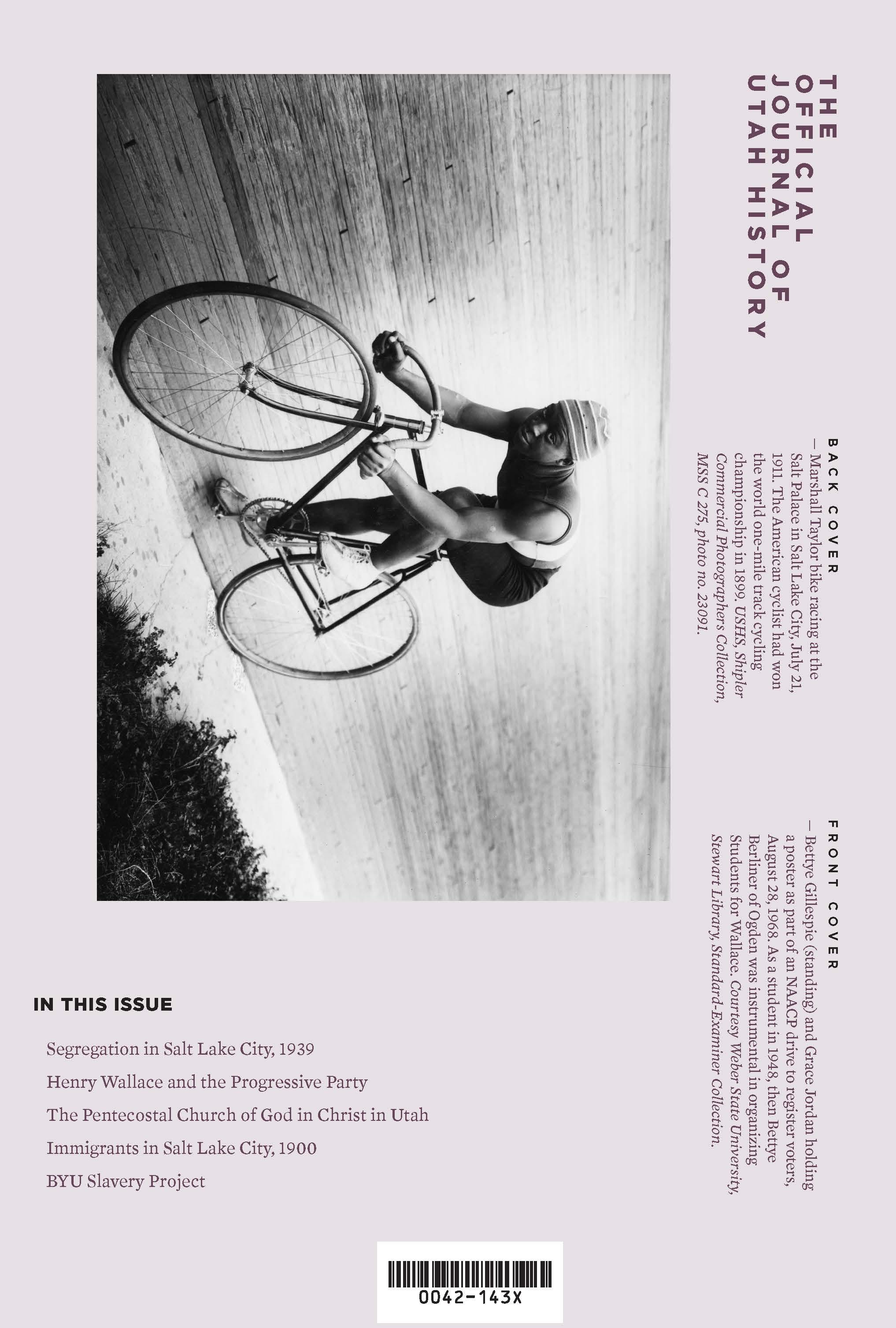

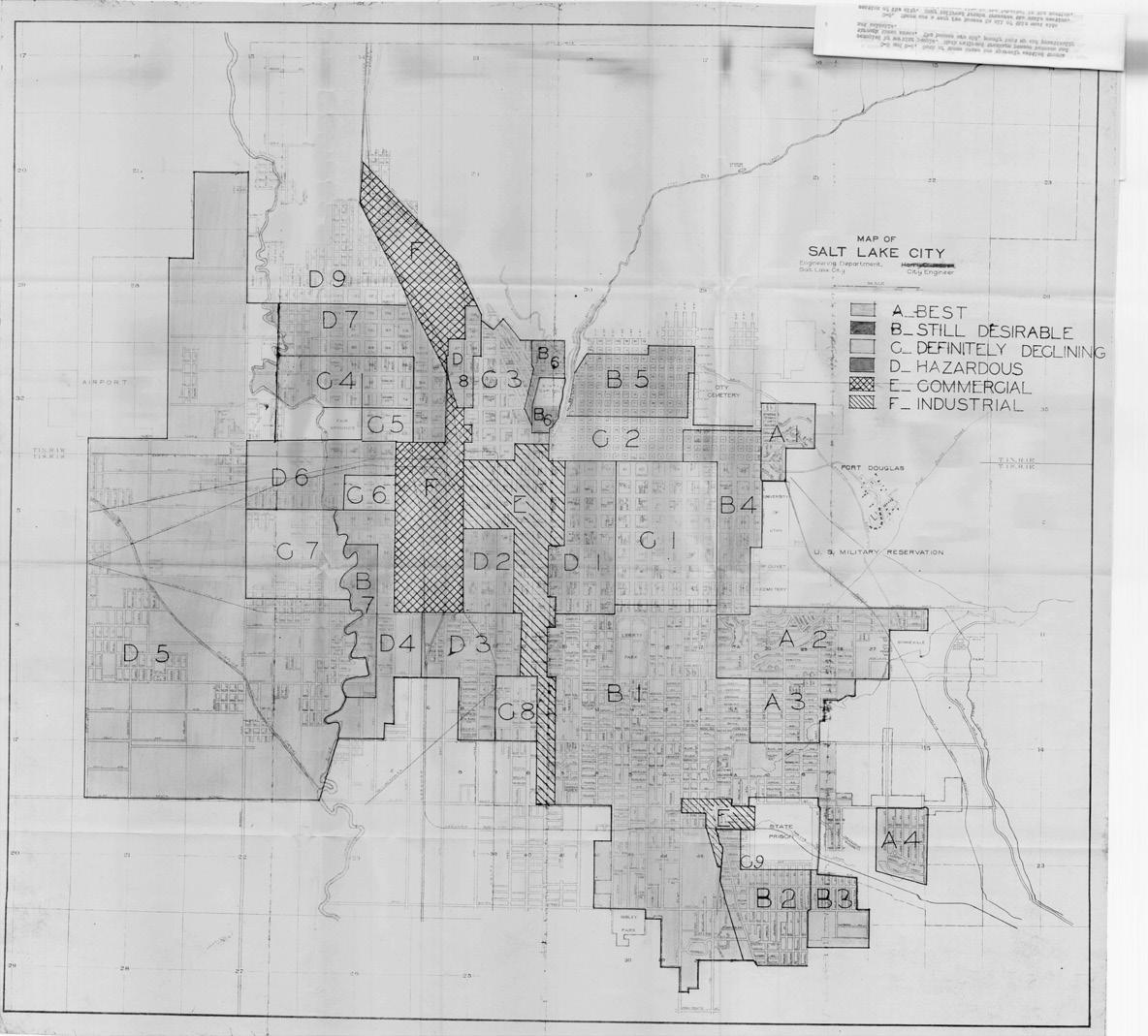

Map of Salt Lake City, 1940.

Created by the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, the map assigned grades signaling a neighborhood or area’s “mortgage security.” Rated safe were the “A” areas; “D” was the lowest grade and considered “hazardous.” Such “redlining” functioned as a barrier to people of colors from acquiring homes in certain neighborhoods. The notes commenting on D-1—the “old part of the city”—read: “In the southwest corner of this section is found the only concentration of negros in the city.” Home Owners’ Loan Corporation files in National Archives at https://dsl.richmond .edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5 /39.1/-94.58.

conveyed to any person not of the Caucasian race.” Therefore, “you will forever be assured of desirable neighbors.” In 1919, titles were amended to reflect that restriction.62 Several subdivisions in Ogden barred all but “the Caucasian race” from owning or living in homes there with the exception of live-in domestics.63 The Federal Housing Authority (FHA), created by the National Housing Act of 1934, “strongly encouraged” this type of racial restriction in neighborhoods to protect its mortgage investments. The agency feared “inharmonious racial or nationality groups” could upset the stability of a neighborhood. Redlining—the practice of identifying neighborhoods where banks took considerable risks to lend money to home buyers—grew out of this fear.64

In 1944 Salt Lake City realtors were forthright in informing city residents that they planned to do everything in their power to segregate neighborhoods. On May 7 that year, several newspaper articles reported their intentions. Don Carlos Kimball, the man who developed Highland Park, was chair of the “nonwhite housing control committee” of the Salt Lake Real Estate Board. He announced he had succeeded in obtaining pledges from most city real estate dealers to decline to sell homes to nonwhites in white neighborhoods. Kimball

said his committee used the 1940 US Census to establish the locations of nonwhite homes. He based his policy on “the National Association of Real Estate Boards’ code of ethics which forbids the sale of property to anyone who might ‘lower community standards.’” Kimball referred to “the recent influx of Negroes” and asserted that as they filtered into predominantly white neighborhoods, white residents left. Acknowledging Black residents’ citizenship, Kimball said that “we will tolerate them, but not favor them.” His committee’s stated goal was to “do everything possible to promote the general uplift of every community.”65

What law would not dictate, informal segregationist policy could accomplish. A number of real estate agents, developers, and individual sellers continued to make it difficult for people of color to buy property and live in predominantly white neighborhoods, at least until Congress passed the Federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, which was intended to finally end racially restrictive covenants and sales practices.66

After standing for property rights and equal protection for herself and members of the Utah Black community in 1939, Lucile Bankhead remained an outspoken leader and mentor to a younger generation of Black Mormons and Utahns. She lived on her Mill Creek land for the rest of her life, proud of her heritage, her religion, and her family.

Despite the Salt Lake City commission denying the demands of Petition No. 1133, Sheldon Brewster, continued to devote his time to government and church work. He was elected to two more terms in the Utah House of Representatives in 1956 and 1958. He was manager of the Utah State Fair from 1941 to 1949 and is best remembered for his work to protect property owner rights and preserve Saltair Resort. After serving eighteen years as bishop of the Salt Lake Third Ward, he became president of the LDS Liberty Stake. His earlier failure did not deter Brewster from his campaign to close the High Marine Social Club. On August 2, 1940, the Salt Lake Tribune reported that Salt Lake City Commissioners refused to issue a beer license to the club. Police Chief Olson recommended it be denied “because of friction the club has caused in the neighborhood between white and colored residents. The license

was also protested by Sheldon R. Brewster . . . chairman of the Central Civic and Beautification league.”67 The Brewster family moved out of the Sumner neighborhood in 1961, and by the end of that decade, a quarter of Utah’s Black population lived in one square mile in the central Salt Lake City area that Sheldon Brewster had called home.68

1. “Meeting Raps Plan for Negro District,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 2, 1939, 14; The Sumner neighborhood is directly southeast of the downtown business and shopping district of Salt Lake City and is part of what most Salt Lakers think of as “Central City.” It runs from 400 South to 900 South between State Street and 700 East. There is an area designated as the Central City National Historic District that encompasses the strip of land from just north of 100 South to 900 South between 500 East and 700 East, so while the two areas overlap, technically they are different. See Mark Hanner Hafey Jr., “Land Use Change: The Impact of the Traditional Process of Land Use Change on the Sumner Neighborhood in Salt Lake City” (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1974).

2. “Ogden Plans Negro Zones,” Deseret News, February 3, 1939, 7.

3. There is no way to tell who attended the Sumner School protest meeting and signed the petition presented to the city commission, but the neighborhood was predominately white and the struggle fell out on racial lines.

4. See Tarienne Mitchell, “Lucille [sic] Bankhead, Defender of African-American Rights,” BetterDays2020 website, https://www.utahwomenshistory.org/bios/ lucille-bankhead/; Helen Papanikolas, ed., The Peoples of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah Historical Society, 1976); Linda Sillitoe, History of Salt Lake County (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Salt Lake County Commission, 1996); and Thomas G. Alexander, “The Civil Rights Movement in Utah,” History To Go website, https://historytogo.utah.gov/?s=the+civil+rights +movement+in+utah. These sources recount Black residents marching on the State Capitol to register their opposition to a Black housing district proposed by Sheldon Brewster. Many details of the controversy are missing from these accounts. They confuse the area proposed as a Black district and they make no mention of other demands made by the Sumner residents, namely the closing of the High Marine Hall. The counter protest by the NAACP is often omitted.

5. “City Petitioned to Find Resident Zone for Negroes,” Deseret News, November 17, 1939, 6.

6. “Meeting Raps Plan for Negro District.”

7. “Meeting Raps Plans for Negro District.”

8. Salt Lake City Commission, Petition No. 1133, 1939, transcription, as quoted in Margaret Judy Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro in Utah and Institutional Efforts to Eliminate It (master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1971), 47. The Salt Lake City Recorder’s Office no longer has possession of the original petition. Some records were water damaged and destroyed, and the petition appears to be among them. Maag made a

transcription and included it in her thesis. The J. Willard Marriott Library Special Collections also holds an undated partial transcription from an unknown person that includes some wording not in the Maag transcript.

9. Nancy Weatherly Sharp and James Roger Sharp, eds., American Legislative Leaders in the West, 1911–1994 (Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997), 67–68.

10. Sheldon R. Brewster interview, September 6, 1974, transcript, 2–3, MSS A 3063, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah. Some spelling and punctuation has been corrected.

11. Brewster, interview, 2. Sheldon Brewster organized the first neighborhood beautification program in Salt Lake City in 1932, as documented in A Preservation Handbook for Historic Residential Properties and Districts in Salt Lake City, pt. 3, ch. 15, p. 5. The handbook also describes the changes the Central City neighbor underwent with the influx of unskilled laborers who moved into the area.

12. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map for Salt Lake City, 1933–1939, shows this neighborhood to be a red or hazardous area, meaning banks took considerable risks to lend money to home buyers there. “Redlining” is often associated with New Deal efforts to segregate housing stock, since many redlined neighborhoods were minority neighborhoods. These maps are located in Series: Residential Security Maps, 1933–1939, Records of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, 1933–1989, Record Group 195, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

13. Brewster, interview, 2–3. Brewster’s reference is to early Mormon convert, Jane Manning James, her descendants, and her brother, Isaac L. Manning. Manning and her brother had worked for Joseph Smith in Nauvoo, Illinois. James and Manning lived in the LDS Eighth Ward until James’s death. Then Isaac Manning moved in with James’s granddaughter, Josephine Washington, whose address in 1910 was 150 East 700 South. Her boarding house was within the boundaries of the LDS Third Ward. Brewster, while a young boy, may have known of Isaac Manning.

14. Tonya Reiter, “Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek,” Journal of Mormon History 44 (October 2018): 68–89.

15. Ronald G. Coleman, “African Americans in Utah,” Utah History Encyclopedia, accessed April 6, 2020, https:// www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/a/African _Americans.shtml.

16. Pamela S. Perlich, “Utah Minorities: The Story Told by 150 Years of Census Data,” Bureau of Economic and Business Research, David S. Eccles School of Business, University of Utah, available at https://gardner.utah.edu /bebr/Documents/studies/Utah_Minorities.pdf. The number of Black Utahns in 1930 was actually lower than the 1910 census figure of 1,144 and the 1920 count of 1,446. In 1940, the number of Blacks had only risen 127 to 1,235. Even with Black railroad employees and families moving in, it was not until after WWII that Utah’s Black population doubled to 2729 in 1950.

17. “Meeting Raps Plan for Negro District.”

18. “Negro Area Plan Draws Protests,” Salt Lake Telegram, November 2, 1939, 7.

19. “City Petitioned to Find Resident Zone for Negroes,” Deseret News, 17 November 17, 1939, 6.

20. “Group Protests Zone Plans,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 6, 1939, 10.

21. “M. B. McGee and the Broad Ax,” Broad Ax (Salt Lake City), September 25, 1897. 4.

22. “Colored Masons To Build Lodge Home,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 18, 1922, 6, “Society Plans New Building,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 29, 1929, 34.

23. “Petition Protests Giving Permit for Lodge Rooms,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 4, 1929, 34,

24. “Zoning Board Defers Action on Complaint,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 18, 1939, 13.

25. Petition No. 1133.

26. “Group Protests Zone Plan,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 6, 1939, 10.

27. “Salt Lake Negro Group Opposes Race Segregation,” Deseret News, November 8, 1939, 13.

28. “Colored Group Elects S. L. Leaders, Files Protest Against City Negro District,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 10, 1939, 24.

29. “Forum to Discuss Rights of Group,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 8, 1939, 24.

30. Petition No. 1133

31. “Negro Ghetto” in “Afro-Americans, Utah” Vertical File, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. This document is a partial transcription of Petition No. 1133. These two sentences are not found in the Maag transcript of Petition No. 1133.

32. Brewster, interview, 3.

33. “Committee Named to Study Negro Section,” Deseret News, November 21, 1939, 24.

34. “Racial Barrier Protest Filed,” Salt Lake Telegram, November 21, 1939.

35. Salt Lake City Commission Minutes, November 21, 1939, 834, Salt Lake City Recorder’s Office, Salt Lake City, Utah.

36. Commission Minutes, November 21, 1939, 833.

37. Commission Minutes, November 21, 1939, 833.

38. “Committee Named to Study Negro Section.”

39. Mary Lucile Perkins Bankhead, interview by Leslie G. Kelen, Salt Lake County, Utah, 1983, transcript, 26, box 1, fd. 6, pt. 3, “Interviews with Blacks in Utah, 1982–1988,” MS 0453, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

40. Bankhead, interview, 27.

41. Bankhead, interview, 27.

42. Bankhead, interview, 25–28. Bankhead names Louis Leggroan as the black agent. Ironically, he was the husband of Alice Weaver Leggroan who protested the idea of a segregated district with Lucile Bankhead. Alice had been an officer in the Salt Lake Branch of the NAACP earlier in the 1930s. For biographies of both Louis Leggroan and Alice Weaver Leggroan, see Century of Black Mormon, https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/ century-of-black-mormons/page/welcome.

43. Commission Minutes, November 21, 1939, 833.

44. “Negro Intends to Open Ogden Legal Practice,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 1, 1931, 4.

45. In 1940, the flamboyant D. H. Oliver told Judge Oscar McConkie that he wanted an entire pool of two hundred potential jurors dismissed because of their membership in “an organization prejudiced against the negro race.” When McConkie asked what that was, Oliver said they were all members of the Democratic Party! Evidently Oliver had a change of heart because twelve years later, in 1952, Milt Weilenmann, Utah Democratic state chairman, named Oliver as the Democratic campaign director for Blacks. See “Attor-

ney Charges Negro Prejudice by Jury Panel,” Deseret News, February 3, 1940, 14; and “Democrats Name Campaign Head,” Salt Lake Tribune, October 11, 1952, 29. Oliver is known for a book he wrote after living thirty plus years in Utah, A Negro on Mormonism.

46. The National Negro Congress was a short-lived organization affiliated with the Communist Party and had as its goal the fight for Black liberation. “National Negro Congress,” accessed April 27, 2020, https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Negro_Congress.

47. “Committee Named to Study Negro Section.”

48. Commission Minutes, November 21, 1939, 834.

49. “Ogden Plans Negro Zones,” Deseret News, February 3, 1939, 7.

50. “Sharp Remarks Made as Negro Trouble Aired,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, February 2, 1939, 11.

51. “Ogden Plans Negro Zones,” Deseret News, February 3, 1939, 7.

52. “Bench Citizens Resist Negro Family Influx; Protest Made to City,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 11, 1939, 14.

53. “Letters to the Editor,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, July 14, 1939, 3.

54. “Sharp Remarks Made as Negro Trouble Aired”; Minutes of the Regular Meeting Board of Commissioners of Ogden, Utah, February 2, 1939, 79. See also “Ogden Plans Negro Zones.”

55. “Ogden Plans Negro Zone.”

56. Minutes of the Regular Meeting Board of Commissioners of Ogden, Utah, February 7, 1939, 84.

57. 1939 Session: Bill 96, box 23, fd. 39, Utah Legislature, House of Representatives working bills, Series 432, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

58. Brewster, interview, 16–17.

59. Sheldon R. Brewster to Utah House of Representatives democrats, n.d. [ca. 1959], Sheldon Riser Brewster Papers, 1919–1975, MSS SC 1980, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. Some spelling and punctuation corrected.

60. “Reports of City Officers, 24,” in Salt Lake City Commission Minutes, February 21, 1940, 139, Salt Lake City Recorder’s Office, Salt Lake City, Utah. By this time the Fourteenth Amendment was often applied to state and local law through the principle of “incorporation.”

61. Buchanan vs. Wardley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

62. Polly Hart, “Highland Park Historic District,” accessed July 16, 2021, https://www.livingplaces.com/UT/Salt _Lake_County/Salt_Lake_City/Highland_Park_Historic _District.html; “Utah’s Black History includes legalized housing discrimination,” accessed July 16, 2021, https:// www.fox13now.com/news/uniquely-utah/legalized -housing-discrimination-mars-utah-neighborhoods -past.

63. “Professor Probes Housing Discrimination,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, May 26, 2021, 1.

64. Hart, “Highland Park Historic District”; “Utah’s Black History includes legalized housing discrimination.” Again, Buchanan vs. Wardley had already ruled that legislation to separate the races to keep the peace overstepped the police power held by the individual states. The majority opinion in that case stated that the problems “arising from a feeling of race hostility” cannot be solved by “depriving citizens of their constitutional rights and privileges.”

65. “S.L. Realtors Restrict Housing of Nonwhites in Urban Areas,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 7, 1944, 17.

66. See John Spencer Kirkham, “A Study of Negro Housing in Salt Lake County” (senior thesis, University of Utah, 1968).

67. “City Denies License to Social Club,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 2, 1940, 9.

68. Kirkham, “A Study of Negro Housing in Salt Lake County,” 6. According to Hafey, in “Land Use Change,” 52, by 1974, eighty percent of Black residents in the Sumner neighborhood were on welfare. “Many of these Blacks have migrated to this area from the Southern States and are poorly educated.” In his thesis, Hafey related many of the same problems Brewster talked about in the Sumner neighborhood. Housing units held by absentee landlords far outnumbered owneroccupied homes. Economics and land use changes resulted in owners creating smaller and smaller apartments out of former single-family houses. Uncertainty related to possible changes in land use and zoning gave rise to homeowners and renters neglecting properties, so many structures became sub-standard and were allowed to deteriorate. A cycle developed in which lenders became afraid to risk funds on the neighborhood, so the residents were unable to improve their homes, making them ineligible for loans and so on.

On December 29, 1947, former vice president Henry A. Wallace announced that he would enter the coming presidential race as an independent—the culmination of a series of events that began when Wallace was denied re-nomination in 1944. After that defeat, FDR had appointed him secretary of commerce as a consolation, and after Roosevelt’s death many liberals—but not all—considered him the leader of the New Deal legacy. Over the next three years, Wallace became increasingly critical of the foreign policy of Roosevelt’s successor Harry Truman, leading to Wallace’s eventual dismissal from the cabinet. Many then encouraged him to challenge Truman in the Democratic primaries; others suggested that he take advantage of the independent route. Among them, two groups, both nationally and in Utah, played a central role promoting Wallace’s independent candidacy—the Progressive Citizens of America (PCA) and the International Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union (IMMSWU).1 PCA was organized in December 1946 with ties to organized labor. It became a counteracting force to the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) founded a month later, and the major organization of anti-communist liberals. While these two groups generally agreed on domestic issues, they were at odds over the Truman Doctrine, Communist influence in politics and unions, and Wallace’s candidacy. The Communist Party was a third group instrumental in promoting Wallace and, ultimately, in creating a new party. In the last effort of their “popular front” approach tracing back to the New Deal, Communists and their allies provided grassroots organizational support for Wallace. Ultimately, the decision proved to be disastrous to the Communists and their labor allies, while also weakening the broad appeal of Wallace and the Progressive campaign.2

Wallace proclaimed that “a new political alignment” was necessary because “everywhere . . . today I find confusion, uncertainty and fear. The people do not ask ‘Will there be another war? – but when will the war

come? They do not ask ‘Will there be another depression? – but ‘When will the depression start?’”3 He invited those who agreed with him to join with “the forces of peace, progress and prosperity” as part of a “Gideon’s Army, small in number, powerful in conviction, ready for action.” Wallace concluded his remarks: “We face the future unfettered by any principle but the general welfare. We owe no allegiance to any group which does not serve that welfare. By God’s grace, the people’s peace will usher in the century of the common man.”4 A month later, Idaho Democratic Senator Glen Taylor agreed to be his vice-presidential nominee. Support for Wallace was at its highest at this point. Thousands of Americans—in union halls, on college campuses, and among critics of Truman’s foreign policy—flocked to his banner, and Democrats, who doubted he could win, were worried about his impact in the election. Wallace campaigned for civil rights, desegregation, social justice, and economic security, all under the cloud of nuclear war.

Much of the scholarly scrutiny over Henry Wallace’s campaign for president has focused on the extent of communist influence in the campaign.5 This article examines the efforts for Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party’s campaign in Utah. The activity of and issues facing the campaign in Utah were the same as they were elsewhere in the country, including communist involvement, even as certain uniquely Utah factors were at play. In that sense, Utah serves as a microcosm of what happened nationally. I also focus on the Utah Progressive Party’s leadership and supporters: what drew them to the Progressive cause, how they fared at the polls, and what happened to the Utah party and its key figures after the 1948 election. I follow Richard Hofstadter’s suggestion that political historians should “try to tell what people thought they were doing in their political activity—that is what they thought they were either conserving or reforming or constructing.”6

The immediate reaction in Utah to Wallace’s decision to run was mixed. As was true nationally, some Utah liberals were unsure how to proceed. Former Utah PCA chair George S. Ballif said that while Wallace was a “great guy,” he would not “follow him into a third party”

and “lessen the liberal movement in the Democratic party.”7 Republicans “professed glee” at Wallace’s decision, and state chair Vernon Romney said the move enhanced an “already assured” Republican victory. At the same time, Democratic chair Clinton Vernon told the press that while the former vice president had “a following in Utah,” he doubted that the Wallace candidacy would gain much support, because “there are quite a few Democrats friendly to Wallace who will not indorse the third party movement.” Still, he admitted that the new party might threaten the Democrats in 1948.8

Indeed, Wallace’s potential to hurt the Democrats was a factor in Utah as it was elsewhere. Utah Representative Walter K. Granger commented that Wallace was “a sincere man living in the clouds,” and that his potential candidacy was being used “by some groups who seek to promote confusion and chaos rather than the public welfare,” Yet Granger admitted that “some fine and sincere people will support him,” especially on issues like the draft and peace. Granger’s views received editorial support from the Salt Lake Tribune, which claimed that many Wallace backers consisted of “misty eyed persons who have a weakness for admiring anyone who proclaims himself a liberal fighting for the masses,” while other more “responsible” liberals were “already beginning to wonder” about the wisdom of such an effort.9

Louise Douglas, Utah Progressive Citizens of America secretary, responded that she was shocked the Tribune would “authorize publication of a statement losing sight of current political . . . life and imputing to Mr. Wallace a political narrative that is alien to his thought and action,” inferring that Wallace had become “a pawn or a dupe of unworthy elements.” Such an argument, Douglas asserted, was a “poisoned arrow borrowed from the propaganda arsenal of the enemies of the people.” She also offered the widely-held view of many liberals on the nature of the Democratic Party at the time, noting that because on several issues, it was just a “carbon copy” of the Republicans, “the third-party movement will bring to the polls the decisive liberal vote and therefore it will help rather than hurt ‘progressive’ candidates regardless of party.” Implicit in this view was a belief that under Truman the Democrats

had abandoned the liberalism of Franklin Roosevelt10

The roots of the PCA in Utah stretch back to July 1945, when former Minnesota governor and senator Elmer A. Benson visited Utah on behalf of the National Citizens Political Action Committee. Benson, chair of the NCPAC executive council, was accompanied on the two-day visit by vice chair C. B. “Beanie” Baldwin—a close aide to Wallace—and chief field officer Orville E. Olson. Their focus was building support within Utah labor for the Democratic Party generally, and Truman specifically. After meeting with Utah governor Herbert B. Maw and Utah Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) president Clarence Palmer, the group attended a banquet with a large group of Democratic Party and labor officials, at which Benson lauded Utah’s congressional delegation, telling the press he was seeking to gain an understanding of Utah’s “reconversion problems and postwar plans.” Benson focused on building support within Utah labor for the Democratic Party generally and Truman specifically. A month later, Baldwin suggested to Palmer that they were “very anxious to have a State Citizens PAC formed in Utah as soon as possible” to strengthen labor and progressive forces in the state. Baldwin believed “from a public relations standpoint it will be better to have this committee sponsored by other than the CIO leadership,” while recognizing that labor would “participate actively” in the effort.11

Another important step involved the Utah Independent Citizens Committee (UICC), formed in 1946 and chaired by Salt Lake City lawyer Gordon Hoxsie. The UICC favored national “legislation forbidding discrimination against minority groups, guaranteeing labor’s right to bargain collectively, and developing atomic energy under the direction of the United Nations.” On the state level, it advocated for rent control and repealing Utah’s sales tax. Over the next few months UICC sponsored several public forums and endorsed a number of candidates. Ultimately, they allied with the National Citizens Political Action Committee (NCPAC) and became the nucleus for a Utah PCA chapter, which was organized in April 1947, with M. I. Thompson as temporary chair.12 Utah PCA sought to “fight inflation,

discriminatory labor practices, the impoverishment of the farm, and for a lasting peace throughout the world.” Within a few days, Utah PCA made plans for Wallace to speak in Utah in May under their auspices, but ultimately the speech was cancelled.13 Wallace did visit Utah in May 1947, when he appeared at a brief stopover at the Salt Lake City airport. Wallace told reporters he feared the world was being divided into hostile camps by Truman’s policies. He also addressed his political future, noting he had found “many evidences of growing liberalism” among the large audiences that he had encountered on his speaking tour in California and the Pacific Northwest. When asked if there would be a third party in 1948, he replied though “impossible to answer,” he believed if “the Democratic party clearly becomes a war party” then “a third . liberal party next year” was likely. That same day, the Salt Lake Tribune editorialized that if Wallace became “the nominee of a third party,” it would be supported by “the undemocratic element” in the United States and the Soviets.14

In July George S. Ballif, judge of Utah’s Fourth Judicial District, became chair of the Utah PCA chapter. Other officers were F. E. Shippe, vice chair; M. I. Thompson, treasurer; and, Louise Douglas, secretary. They urged Utahns to join PCA because it was “a force resisting fascist tendencies, [and] the drift toward war and in to depression.” Later, after Ballif stepped down, Dr. James E. P.Toman, assistant professor of physiology at the University of Utah, assumed the post. In January 1948, Utah’s PCA endorsed Wallace and selected Betty Nickerson to attend the national PCA conference in Chicago that month. Nickerson was among some five hundred delegates from twenty-six states to participate and hear from Wallace. At the conclusion PCA voted to join with other “like-minded groups” to support Wallace, which allowed state PCA affiliates to join Wallace for President groups.15

From the beginning Wallace and his new party were widely accused of being influenced—even controlled—by Communists, primarily because the party endorsed him and did not field its own ticket. On December 30, 1947, the Deseret News ran a cartoon titled “The Papers Are Full of What Happens to People Who Pick Up

Hitchhikers.” It pictured a buck-toothed Wallace in a jalopy labeled “Henry’s Third Party” saying, “Sure! Hop in!” to a long-haired figure resembling a wolf, signifying American Communists. Similar images and sentiments would mark the Utah press in subsequent months.16

Despite these caricatures, both Wallace and Taylor were well known in Utah and occasionally visited the state. Utah Democrats had supported Wallace’s winning bid for vice president in 1940 and his losing effort at the 1944 convention.17 While divided between a conservative and a liberal wing, most Utah Democrats fell into the latter. They had been strongly supportive of Roosevelt and remained closely tied to the state’s labor movement. These factors drew them to Wallace, though, increasingly, the charges of Communist influence on him and his candidacy resonated with some.18

Glen Taylor was even better known to Utahns. He had visited the state before his political career as leader of the “Glendora Players,” a traveling theatrical company popular in Ogden and Salt Lake City that included his wife, Dora, and son, Arod (Dora spelled backwards). As the Salt Lake Telegram noted, he was a “colorful Democrat who has successfully roped cows, sung on the radio, and worked sheet metal for a living.”19 After losing Idaho races for US Congress in 1938 and the US Senate in 1940 and 1942, while campaigning in cowboy garb, Taylor, ran a successful Senate run in 1944 that was covered in the Utah press.20 By then he had dropped the western attire for a business suit.

During the 1946 midterm elections, Taylor keynoted the Utah Democratic convention held at Saltair, delivering a “stemwinder” directed against “big business, the ‘reactionary majority’ in congress, the ‘controlled press,’ and demagogues who seek to divide labor, farmers, and small businessmen.’” The Democratic Party, he stated, “must remain true to the liberal ideals” of Roosevelt, because there was a “fundamental difference” in the economic philosophy of the two parties. The Republicans, he said, “pour in at the top on the theory that the crumbs will fall below. The Democratic approach is to support the bottom and this in turn starts the wheels throughout the economic structure.” Taylor concluded with his belief “that the prosperity of the nation is founded on those who work for

wages and the fate of all the little people—laborers, farmers, and business—are tied up in the same bundle.”21

Later that year, Taylor, dubbed “Idaho’s Dynamic Democrat,” appeared at campaign rallies in Ogden, Salt Lake City, and Price. At the Ogden event, broadcast on local radio station KLO, Taylor pushed back on the Republicans’ insistence “that the issue of the day is Americanism vs. Communism” and that everyone who worked for a “square deal” for workers and farmers was a Communist. As he noted, “To hear the Republicans talk everybody in this room tonight is a Communist, and yet we know that we are just good American citizens who insist that the breaks in life should be shared.”22

Some early support existed for Wallace among University of Utah students. Roy E. Tremayne, a liberal political science senior, wrote in the Utah Daily Chronicle that Wallace’s entry into the race was the “most significant political development of 1947.” Tremayne suggested the formation of a Wallace For President club at the school, declaring that Wallace: has “become the great standard bearer of the FDR brand of liberalism. To cast a vote for Wallace is same as casting a vote for Roosevelt.” Wallace, Tremayne predicted, would keep America “on an even keel.”23

A move to organize Students for Wallace began in January, part of similar efforts in other states and colleges.24 The organizers, including the temporary chair of Students for Wallace, Adele Ernstrom, were members of the campus Young PCA (YPCA) chapter. Writing in the Daily Utah Chronicle, Don Wahlquist reported that it had been asserted that the “use of the name PCA would not be associated with the movement to support Wallace,” because PCA had been labeled in some press reports as a “Communist-supported organization.” The next day, Ernstrom refuted the account, noting that “YPCA members . . . did not feel there was a stigma to PCA sponsorship.” While the issue of Communist influence was troubling to some, many on the left saw it as red-baiting. As Ernstrom reflected “the Communists supported the New Deal with which Wallace was of course associated. I think there was an understanding that red-baiting was an attack on what the New Deal had stood for. In other words, the

Wallace candidacy represented a tradition that was coming under attack.”25