48 minute read

Beehive Brews

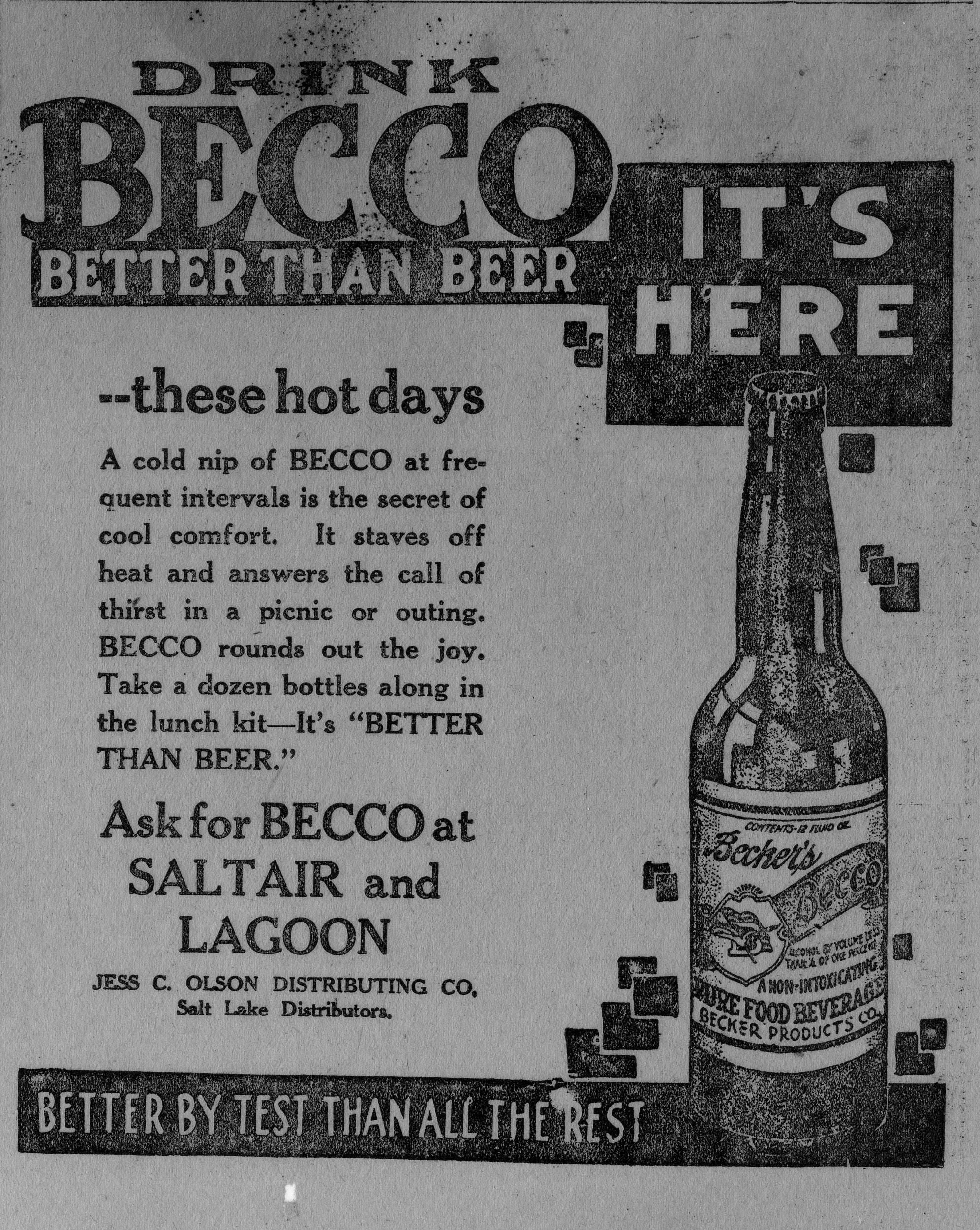

An Advertisement for Becker’s Becco, the company’s non-alcoholic near beer, from 1922. Brewers hoped near beer would keep their businesses going during Prohibition, but the product failed to live up to their expectations. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Becker Brewing and Malting Company Records Addendum, USU_CAINE COLL MSS 31.

Beehive Brews: A Heady History of the Becker Brewing and Malting Company

BY CODY PATTON

As the locomotive’s wheels ground to a halt, Albert E. Becker descended from a railcar in Ogden, Utah’s Union Station on July 7, 1891.1 Traveling from Winona, Minnesota, Albert arrived in Ogden to inspect the Becker family’s most recent business venture, a modern brewhouse on the banks of the Ogden River. The year before, William Schellhas, a business partner of the Beckers, had invested $50,000 to purchase land, construct a brewery, and install complex brewing equipment. Schellhas’s first batch of “Rocky Mountain Amber” received high praise from the citizens of Ogden.2 In 1892, Schellhas sold his shares of the Schellhas Brewing Company to Albert, his brother Gustav (Gus), and their father John Becker. As a result, Gus became president, with Albert taking the position of vice president of the newly incorporated Becker Brewing and Malting Company.3

The Becker Brewing and Malting Company, with their “Becker’s Best” brand beer, became one of Utah’s most successful beer-producing operations, and one of the most significant breweries in the American West. The Beckers grew their business in the thirty years before Prohibition, expanding into other western markets including Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, Arizona, Wyoming, and California. The Becker brewery became one of only 255 American breweries to continue operations during Prohibition by selling “near beer,” soda, and ice.4 In comparison, there had been more than twelve hundred breweries in 1917.5 After Prohibition’s repeal, the Becker brewery thrived in the 1940s but experienced a slow decline in the beer trade after World War II. Eventually, stiff competition from large national companies forced the Beckers to close their doors in 1964.6 The dissolution of the Becker plant, after nearly seventy-five years of operation, marked the end of Utah’s—and one of the nation’s—most successful regional brewing companies.

Given current misconceptions about Utah, the success of the Becker Brewing and Malting Company may seem unusual. Today, Utah is known nationally for its strained relationship with alcohol. Two thirds of Utah’s population belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS), which urges its members to abstain from alcohol consumption.7

Ranked by Time magazine in 2013 as the worst state in the nation for drinking, Utah’s dry population and strict liquor laws earned them an unfavorable reputation among those looking for a drink.8 Home to the infamous “Zion Curtain” until 2018 (a reference to partitions separating customers from where drinks are mixed), Utah also possesses some of the most stringent liquor laws in the country.9 Moreover, a 2015 survey found that Utah had the fewest bars per capita in the country, earning Utah the moniker of “most sober state,” and in 2017 the Smithsonian Magazine reported that “ordering a drink in Utah has long been a surreal experience.”10

Despite contemporary opinions, Utah possesses an incredibly rich brewing past. The Becker Brewing and Malting Company was one of several breweries to take root in the state. Despite persistent misconceptions, Utah’s historic brewing industry consistently mirrored national manufacturing trends. This history illustrates the Beehive state’s incorporation into mainstream American market culture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and challenges perceptions of Utah as a dry state. Indeed, the Becker company’s corporate archive demonstrates that Utah’s early twentieth-century brewers and beer drinkers shared a similar experience to their counterparts across the country, even with the state’s Mormon heritage.

When placed in the context of the American brewing industry, the notion of Mormon peculiarity surrounding alcohol in the state breaks down. As the historian Leonard J. Arrington claimed, “despite their assertions of ‘peculiarity’ much of what was done by the Mormons was truly American.”11 One of the nation’s leading brewing families, the Beckers of Ogden rubbed elbows with members of the Busch, Miller, and Coors dynasties, demonstrating just how connected the Utah industry was with the national scene.12 The study of beer in Utah, therefore, challenges simplistic historical stereotypes and shows that when it came to enjoying a pint of cold lager during the hot desert summer, Utahns of the past—Mormons and non-Mormons alike—operated in shades of gray.

While American brewing history has received periodic attention from historians studying food and business, it is surprisingly understudied, and the history of brewing in the American West even less so.13 While the academic literature on brewing may be limited, the field has experienced a renaissance over the past twenty years.14 Adding to a narrative that often centers on the Midwest and East Coast regions, this article incorporates Utah’s unique brewing environment into the growing conversation of America’s brewing history.15 Using the Becker Brewing and Malting Company as a case study, this article explores the impacts of national brewing trends and perceptions of the beer industry within Utah and demonstrates the predominant role these factors played in both the successes and failures of Utah’s early twentieth-century breweries.

The founder of Becker Brewing, John S. Becker, immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1847.16 As one of nearly one million Germans to arrive in the United States between 1850 and 1859, John Becker joined the company of other German immigrants who founded brewing companies.17 Adolphus Busch, the man behind Anheuser-Busch, and George Ehret, president of New York City’s massive Hell Gate Brewery, both migrated to the United States in 1857.18 The Best family, the founders of Pabst Brewery, settled in Milwaukee thirteen years earlier in 1844.19 Wherever German families settled in the United States, breweries seemed to open, even in Utah.20

The diaspora of Germans to the United States led to a sharp rise in both beer production and consumption throughout the country. Before the influx of German immigrants, Americans generally wetted their whistles with rum, whiskey, hard cider, and the occasional ale.21 According to the historian W. J. Rorabaugh, whiskey in the 1820s was cheaper than milk, wine, coffee, and tea, and on average an adult male consumed a half pint of the stuff daily.22 German immigrants, however, brought lager-style beer with them, which altered traditional drinking habits in the country. Lager utilizes a bottom-fermenting yeast and requires weeks of aging in cold storage. The resulting brew is light, bubbly, and contains relatively little alcohol when compared to spirits. Not only did this new beverage delight the tastebuds of American consumers, but its low alcohol content also fell in line with nineteenth-century morals regarding drink and intoxication, especially as industries tried to maximize worker productivity.23 Many

Americans viewed lager as a beverage of moderation and a healthy alternative to hard liquors such as whiskey and rum.24 As a result of lager’s explosive popularity, beer consumption in the United States increased by nearly 1000 percent between 1840 and 1900.25

Early members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS)—today known nationally for their abstention from alcohol—shared pre-Prohibition views of beer and spirits with many other Americans. The “Word of Wisdom,” lifestyle and dietary guidelines recorded by church founder Joseph Smith in 1833, advised against imbibing “wine or strong drink”: “That in as much as any man drinketh wine or strong drink among you, behold it is not good.”26 Although LDS leaders today interpret this verse to mean total abstention from all alcoholic beverages, this interpretation came about only after a century of negotiating the meaning of Smith’s revelation.27

The Mormon studies scholar Paul Y. Hoskisson outlines several stages of the Word of Wisdom’s development in the initial years of the church. Hoskisson argues that the statute was initially observed as a commandment in 1833. Adherence became a requirement to maintain a good standing in the church.28 While Mormons were commanded to abstain from tea, coffee, tobacco, and alcohol, exceptions were made for the medicinal application of these substances. This practice fell in line with the general acceptance of the medicinal quality of spirits in the United States.29 A decade later, church leadership even relaxed liquor laws to appease non-member residents of their communities. Smith endorsed the desire of Theodore Turley, a faithful member, to construct a brewery in Nauvoo in 1843. As a result, by the time of Smith’s death in 1844, Hoskisson notes, “the standard set in Kirtland had been abandoned.”30 Uneven adherence to the Word of Wisdom continued as the Saints settled the Utah Territory, where church leaders tolerated a degree of personal interpretation. The varied observance of the LDS health code continued among some church members until Prohibition, when church leaders formalized obedience to the Word of Wisdom as one of several requirements to enter LDS temples.31 The as-yet-unformalized interpretation of the Latter-day Saint health code, combined with the growth and diversification of Utah’s population facilitated by the arrival of railroads in the Utah Territory in the latter half of the nineteenth century, fostered conditions for the success of the Beckers and other brewers in nineteenth-century Utah.32

Photograph of the original Becker Brewing and Malting Company brewery on the banks of the Ogden River, c. 1893. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Gustav Lorenz Becker Photograph Collection, USU_P0361.

Prior to the Becker family’s arrival in Utah in 1890, John S. Becker had spent much of his life working as a brewmaster for William Schellhas in the latter’s Winona, Minnesota, brewery.33 In the late nineteenth century, the East Coast and Midwest were saturated with local brewing firms. In 1890 alone, 2,156 breweries supplied Americans with their favorite brews (in comparison, the United States would not again surpass this number of breweries until 2011).34 In response to these crowded conditions, Schellhas and the Becker family settled on Ogden as a logical location for a new brewing company. As a growing city of twelve thousand residents with heavy railroad traffic, “Junction City” (as it was then known) acted as a distribution center for much of the American West. A promotional brochure from the city published in 1888 aiming to attract new business ventures extolled Ogden’s advantages as a growing manufacturing center situated in a salubrious mountain climate. The booster promised that with the continual development of rail traffic, “Ogden is just entering upon an era of unprecedented prosperity.”35 The growing number of diverse citizens, travelers, and railroad workers that passed through Ogden would provide the Beckers with their local consumer base.36 Furthermore, Utah’s largest city, Salt Lake, already boasted several established brewing firms, such as the Salt Lake Brewing Company and the Fisher Brewing Company.37

The Becker Brewing and Malting Company rose from humble beginnings but expanded rapidly, quickly becoming the city’s primary brewing enterprise. William Schellhas constructed the original brewhouse among a glade of trees on the banks of the Ogden River. The facility contained modern brewing equipment but was constructed using hewn rock and timbers.38 In 1897, the brewery produced ten thousand thirty-one-gallon barrels of beer annually.39 During their first decade, the Beckers experienced a lively beer trade and updated their facilities to capitalize on the growing demand for their products. In 1905, the company built a new four-story brewery that contained an ice-producing plant, malt house, bottling department, with direct access to a rail line that aided in importing raw materials and exporting beer throughout the Mountain West.40 Louis Lehle—a prominent brewery architect from Chicago whose prior worked included Milwaukee’s massive Blatz and Schlitz Breweries—designed the Becker’s new facility.41 By the early twentieth century, the Beckers had expanded their production capabilities to twenty thousand barrels of beer annually, doubling their capacity in a decade.42 Business was booming. In addition to improving their brewhouse, the Beckers also used common industry growth tactics to stimulate their beer sales.

One of the most significant tactics adopted by the Beckers included the tried-and-true practice of regional price-fixing. By 1892, using new methods developed by Pasteur and bottling technology perfected by the Crown Cork and Seal Company, large brewing companies like Anheuser-Busch sold their beer across the country.43 To compete with the massive eastern firms, western brewers and wholesale liquor dealers often worked to fix the price of these “imported” brews and then undercut them with their own cheaper, locally produced beer. In December 1895, the Becker Brewing and Malting Company obtained the rights to sell and distribute Anheuser-Busch beer in Ogden.44 Two years later the Beckers reached an agreement with other beer distributors in the city, who sold other national brands, to fix the price of eastern beer at ten dollars per barrel on draught beer and eleven on bottled beer.45 The Beckers then sold their own beer at nine dollars a barrel and offered a three-dollar rebate for returned empty bottles.46

In addition to maintaining an affordable beer, price-fixing helped the Beckers emerge as champions of local industry. On January 1, 1896, the Ogden Daily Standard praised the Becker Brewing and Malting Company as a “striking example of home industry, as it employs Utah men only, consumes Utah raw materials, and the stock is owned in Ogden.” The paper continued by concluding that Becker’s beer “is as fine a beer as the best brands manufactured in the east.”47

Another critical strategy adopted by the Beckers and other brewers across the nation was the establishment of local tied houses. These contractual agreements established a system where a brewery would provide the funds to open a saloon or cover a liquor license fee in exchange for the proprietor agreeing to serve the brewery’s products exclusively. This agreement “tied” the saloon to the brewery. Tied houses played an essential role in the existence of local and regional breweries, allowing them to continue successful operations even though the large shipping firms held overwhelming economies of scale.48 The Beckers established one of many tied houses as early as 1893 with Ogden saloon owner George Thompson.49

The copious amounts of alcohol consumed by Americans made the success of the tied house system possible. During the nineteenth century, average annual beer consumption by Americans jumped from 2.3 gallons per person in 1840 to a staggering 23.6 gallons in 1900.50 This surge in consumption corresponds with the proliferation of saloons across the country, where the vast majority of beer was consumed. Utah was no exception.51 In 1908 nearly a thousand liquor dealers operated in the state, along with six distillers, five breweries, and more than six hundred saloons—one for nearly every six hundred people.52 In comparison, Utah claimed about one bar per five thousand people in 2015.53 While state-specific consumption data for the early twentieth century is not readily available, Utah exhibits a similar trend in the nationwide abundance of liquor and beer retailers, with over 237,468 establishments in 1910, leading up to the enactment of Prohibition.54

The vast number of saloons, tied or not, gave brewers plenty of options for selling their beer. Due to a desire to keep operating costs to a minimum, however, tied houses were often built on the cheap. Many gained an association with prostitution, gambling, and other vices, which fueled the causes of temperance groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League.55 In addition to their reputation as dens of vice, saloons also have a long history of serving as community institutions. As the historian Elliott West notes, migrants to the American West often turned to shared alcohol cultures and saloons as valuable community-building centers.56 In urban locales, saloons often provided free lunches to their patrons and served as informal political establishments and clubs for the working class.57 Despite these important social functions, the unsavory reputation of the saloon—including Utah’s six hundred—and its association with immigrants added fuel to the fire of middle-class Protestant reformers.

In his report to the United States Brewers’ Association in 1908, W. F. Schad stated, “At least twenty percent of the saloons of [Salt Lake City] should be cut out, for the reason that they are mostly low dives, catering for their trade to women of ill repute and the lowest class of men.”58 Again, broader trends regarding the liquor business can be observed in Utah. Not only did hundreds of saloons call Utah home, but many also acquired the same infamy as their counterparts across the country. The anti-saloon crusaders prevailed in shuttering the nation’s watering holes. Utah, however, became the exact middle state (twenty-fourth out of forty-eight) rather than an early adopter of statewide prohibition.59

The traditional explanation for Utah’s relatively sluggish adoption of statewide prohibition credits political debates within the state’s Republican Party about how to best retain power. The Republican “Federal Bunch” led by Reed Smoot, Governor Spry, and LDS church president Joseph F. Smith initially decided that keeping Utah wet was in their best political interests in the early twentieth century.60 State prohibition is additionally politically nuanced when incorporating the uneven adherence to the World of Wisdom, as outlined by Hoskisson. Health exceptions for alcoholic beverages for members continued to the eve of prohibition. For example, during this time LDS leaders, such as apostles Anthony H. Lund and Matthias F. Cowley, enjoyed the occasional glass of currant wine or pint of beer. George Albert Smith, who succeeded Heber J. Grant as church president in 1945, consumed brandy for medicinal purposes.61 Furthermore, Edgar Brossard—a key figure in establishing an LDS mission in Paris, France—was a frequent Becker customer. Brossard in fact ordered several barrels of beer from the Beckers in 1914.62 That these high-profile members maintained their good standing in the church while imbibing alcoholic beverages suggests that prohibition was not a clear-cut issue. Differing opinions on the morality of alcohol consumption among key church leaders helps explain the lack of a unified push among the faithful to outlaw alcohol in the state earlier. While some anti-liquor crusaders within the church like Heber J. Grant lamented the alcohol consumption of his fellow members, at the turn of the century, drinking and maintaining a good standing within the church were not yet mutually exclusive.

The debates over alcohol, especially beer, as beverage of moderation or intoxicating liquor not only raged among politicians and leaders of the LDS church, but also among the general populace. In the early 1900s, Utah newspapers brimmed with articles and advertisements boasting the nutritive qualities of beer. In 1915 the Salt Lake Herald-Republican ran the headline “Beer Best Brain Food, says Prof. Chandler” of Columbia University, who had argued that beer contained the same food qualities and nutrients as bread (since they were both made from grains and yeast).63 The Beckers, along with brewers across the country, capitalized on this mainstream perception, and in the three decades before Prohibition frequently featured claims about beer’s healthfulness in their advertisements. In 1906 a Becker Brewing and Malting Company postcard ad featured the testimony of a young girl claiming that a doctor’s prescription for their beer made her sick mother healthy again.64 Becker’s full-page ad in the Ogden Daily Standard featured multiple paragraphs describing the “nutritive value of beer,” claiming that Becker’s Best, being “food as well as the healthiest of all drinks, will help you to conserve your energy.” The ad also targeted women consumers by suggesting that a pint of Becker’s Best could even help ease the burdens and stress of housework.65

Due to the activism of Progressive-era reformers, however, the medical arguments for spirits began to ring hollow.66 While brewers and allies played up the benefits of their brews, anti-liquor crusaders pushed their own science that labeled beer as poison. In 1915 the Women’s Christian Temperance Union decried “Beer a[s] Poison” in the Iron County Record. Guest author T. D. Crothers, a scholar of inebriation and medical superintendent of Walnut Lodge Hospital in Connecticut, wrote that “beer is a most insidious poison because it produces other poisons, and starts new processes of degeneration that are unknown until the final collapse reveals them.”67 The debate surrounding beer continued in Utah and national newspapers, but by the outbreak of World War I the scales had shifted in favor of the prohibitionists.

This photograph depicts Gus and his wife Thekla picnicking under a tree. The whole Becker family enjoyed outdoor recreation and often hosted family gatherings and business meetings in the mountains above Ogden. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Gustav Lorenz Becker Photograph Collection, USU_ P0361.

On February 28, 1917, the high deserts of Utah became even drier with the statewide prohibition of alcohol. While the war had waged in moral, scientific, and medical terms, the potential loss of political power ultimately played a key role in Utah’s late adoption of prohibition. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Reed Smoot, a Utah senator and LDS apostle, along with LDS church president Joseph F. Smith, feared that outlawing liquor would create a rallying cry for non-Mormon interests and jeopardize their political grip on the Salt Lake City government. This apprehension led to Governor Spry, a member of Smith’s and Smoot’s “Federal Bunch,” vetoing two prohibition bills in 1909 and 1915. The temperance movement in Utah, however, was pan-religious, and several key LDS leaders who desired and preached prohibition, namely Heber J. Grant, worked with the Anti-Saloon League and leaders of other faiths to pass statewide prohibition legislation.68 Though the political agendas of Smoot and Spry stalled statewide prohibition, the crusade against the saloon gained ground in Utah as critical LDS church leaders joined forces with progressives and other religious leaders. W. F. Schad reported that “the ministers of Salt Lake City, outside of the Catholic and Jewish Denominations have an Assn., [sic] called the Ministerial Union of Salt Lake City. . . . They are naturally for prohibition and using every effort to get the Mormon Church to join them in this fight.”69 Governor Simon Bamberger, a Jewish immigrant who had run as a Democrat on a prohibition platform in 1916, signed the Young Prohibition bill into law in 1917.70

Word of Wisdom scholars state that Prohibition became the turning point in removing the long-standing medical exemption for alcohol.71 Thereafter, LDS leaders revoked medical exemptions commonly practiced among both LDS and broader American communities (common beliefs held that spirits aided in digestion and beer constituted an invigorating health tonic and food beverage). Leaders moved to strictly enforce the Word of Wisdom, including a churchwide ban on all alcohol consumption.72

Due to the federal tax revenue generated by beer sales along with the product’s popularity, brewers initially thought themselves safe from the anti-liquor crusade. However, beer’s distinction from other liquors would not last. The income tax amendment, passed in 1913, eclipsed beer sales as a governmental revenue stream, and with the rising tide of anti-German sentiment during the First World War, German American brewers became the target of temperance groups and other anti-German forces in the country.73 Due to wartime hysteria and the prevailing connection of brewers to Germany, drinking and producing beer became synonymous with disloyalty to the United States.74 In 1918 the U.S. Senate held hearings and trials in which several senators accused the United States Brewers’ Association (USBA) of aiding and abetting Imperial Germany by funding political races for pro-German politicians. The USBA had in fact funded the campaigns of anti-prohibition politicians and temperance advocates who used anti-German sentiments to tarnish the image of America’s beer producers.75 By now Americans were lumping beer in with other corrupting alcohols to be outlawed with the adoption of the Volstead Act and the Eighteenth Amendment.

The anti-German sentiment sweeping the nation did not stop the Beckers from trying to save their good name. On April 18, 1917, the Ogden Daily Standard reported that Gus Becker sent President Woodrow Wilson a personal telegram “tendering the use by the government of the great brewery plant in Ogden for any purpose in support of the national cause.” The Daily Standard stated that “Mr. Becker’s offer to the government is regarded as merely another evidence of the sincere patriotism of himself and his family.”76 However, it appears that President Wilson declined Gus’s offer. Even though the Beckers’ brewing business fell victim to the economic impacts of nationwide wartime anti-German hysteria that swept beer into the sights of anti-liquor crusaders, the family still enjoyed a favorable reputation in Ogden, and their patriotism was touted in local newspapers.

Throughout the heated political battles, the Beckers realized that despite their popularity, their small amount of political capital would be of little use in preventing state prohibition. So they pivoted their efforts to prepare for business operations in a dry state. One drastic measure was shifting the entirety of their beer-producing operations to Evanston, Wyoming. The Beckers opened a new brewery, still named the Becker Brewing and Malting Company, to serve their customers in the remaining wet states of Wyoming and Nevada.77 The Evanston brewery opened in November 1917 and operated for just two short years. With the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment on the horizon, the board of directors saw the writing on the wall and liquidated the Evanston brewery on January 15, 1919. Gus Becker purchased the remaining shares, which included the land, title, and rights of the Evanston brewhouse for $70,000.78

With their Evanston brewhouse closed, the Beckers returned their focus to Utah, looking to national trends to stay solvent during the dry years of Prohibition. The Beckers had invested in “near beer,” a non-alcoholic beverage made with malt and hops, labeled Becco, as early as 1911.79 Other leading brewers also devoted resources to developing alternative drinks to beer. From 1906 to 1916, the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association worked to perfect its own line of near beer that they released under the name of Bevo.80 Pabst also released its line of near beer, Pablo, in 1915.81 It was not until the 1920s, however, that the renamed Becker Products Company aggressively marketed their near beer.82 This, in addition to heavily investing in the soda and ice business, enabled the Beckers to operate the only brewery in Utah and one of only 255 breweries nationwide during Prohibition.83

The Beckers’ new products were met with much acclaim throughout the state, and production of Becco and soda soon outstripped the company’s previous manufacturing—from 60,000 barrels of beer in 1917 to 75,000 barrels of Becco and soda in 1924.84 From 1920 through the repeal of Prohibition in 1933 and beyond, Americans developed a penchant for soda, particularly ginger ale and Coca-Cola.85 The Beckers cashed in on this trend at the right time, and their soda production allowed the firm to sustain growth leading up to the Depression. The Beckers’ successful pivot to non-alcoholic beverages earned accolades from LDS church president Heber J. Grant, who in a personal letter praised Gus Becker for the quality of the company’s products and commitment to following dry laws.86

While many Americans hoped the national ban on alcohol would solve society’s ills, Prohibition in fact exacerbated some issues and spawned a host of new ones. After more than a decade of struggling to enforce dry laws, halt organized crime, and prevent deaths from illegally produced adulterated alcohol, President Franklin D. Roosevelt effectively terminated the nation’s legal beer drought on March 21, 1933. Roosevelt signed the Cullen-Harrison Act, which amended the Volstead Act to accommodate the production of 3.2 percent alcohol content beer.87 Prohibition officially ended eight months later when Utah ratified the Twenty-first Amendment—the twenty-sixth and deciding state to do so.88

Despite the new emphasis placed on temperance both nationally and within the church, Utahns favored repeal for several reasons. While Utah did not experience the same degree of violence in other states during Prohibition, the state had its fair share of bootlegging and shootings during the 1920s and 1930s.89 The primary purpose, however, was for economic factors. The prospect of new tax revenue and jobs motivated Utah voters, as it did for many in other states, to vote for repeal during the depths of the Great Depression.90 When the state temporarily closed the Becker Products Company for producing and selling beer with 3.2 percent alcohol content before the repeal of the state’s own liquor laws went into effect on January 1, 1934, one month after the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment, the Ogden and Salt Lake Chambers of Commerce pleaded with Governor Blood to intervene. They argued that the community of Ogden wanted the brewery operating again. The Chamber of Commerce supported the Beckers because their brewery provided one hundred desperately needed jobs.91 In response, Governor Blood signed “Permit No. 1” on June 26, 1933, which allowed the Beckers to ship their beer to thirsty customers in eleven states. Gus boasted that with the ability to export their beer, the Ogden brewery could now employ 125 workers and would contribute between $100 and $200 worth of tax revenue to the state per day.92 The Beckers were back in business.

An aerial photograph from the late 1930s of the Becker Products Company in Ogden, Utah. The Becker’s demolished and rebuilt their original brew house into the four-story brewery pictured here in 1906. The brewery was located at the corner of 19th Street and Lincoln Ave in Ogden. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Gustav Lorenz Becker Photograph Collection, USU_P0361.

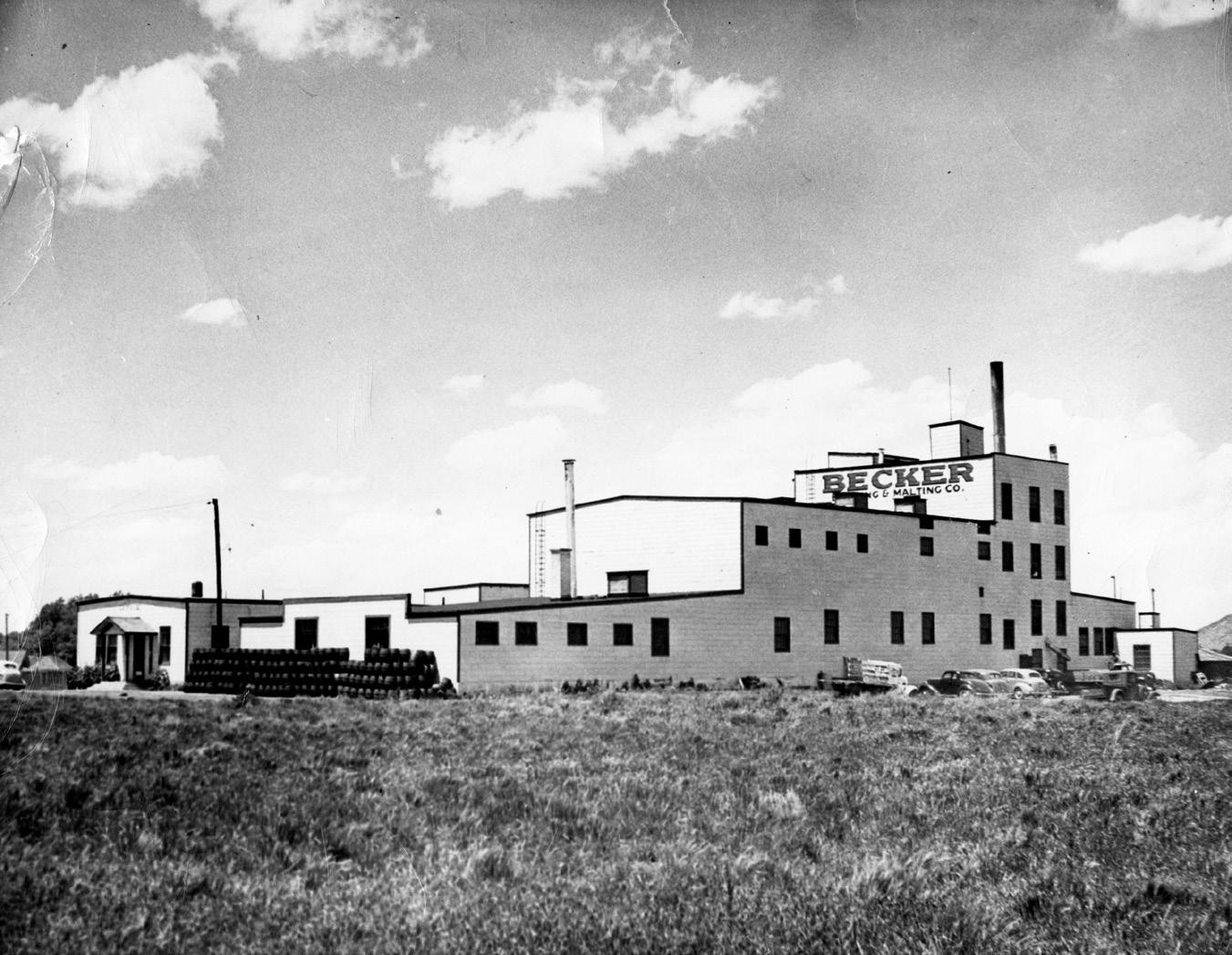

A photograph of the Becker Brewing and Malting Company of Evanston, Wyoming taken in the late 1930s or 1940s. The Beckers opened the Evanston plant in 1917 to brew beer for Western states after Utah went dry in 1916. The plant closed in 1919 with the enactment of national prohibition. The family revived the plant following repeal in 1933 to supply full-strength beer to Western markets. Their Ogden plant produced beer with 3.2 percent alcohol content for Utah markets. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives, Gustav Lorenz Becker Photograph Collection, USU_P0361.

As the Becker family rebuilt their beer business after repeal, they continued to produce their flagship 3.2 brew, Becker’s Best Pilsner, at their Ogden location for local consumption. Since Utah liquor laws prohibited the manufacture or sale of beer with more than 3.2 percent alcohol content by weight, the family revived the defunct Becker Brewing and Malting Company of Evanston, Wyoming, where it launched a line of full-strength beer—Becker’s Uinta Club.93 The return of legal beer (including Becker beer) to Evanston resulted in three days of revelry. One spectator at Evanston’s beer celebration on May 20, 1933, noted that “never did I see such unreserved surrender to the God of Pleasure.” The author also observed “cars of many makes and models, many having Utah license plates” among the merrymakers.94

New liquor revenue for the state became a bright spot in Utah’s financial situation during the 1930s. Even though since 1921 strict abstention from alcohol had become necessary to maintain good standing with the LDS church, liquor sales in Utah rebounded rapidly following repeal. Aside from those who crossed state lines to carouse in Evanston in 1933, many Utahns chose to patronize local joints and the newly established state liquor stores. The USBA Brewers’ Almanac reported that between 1934 and 1939, the state of Utah collected $683,000in tax revenue from beer sales. Utah taxed beer with 3.2 percent alcohol content at $1.20 per barrel until the state legalized full strength beer on March 25, 1935. After that, 3.2 beer was taxed at $0.80 per barrel with full strength taxed at $1.60 per barrel.95 The Salt Lake Telegram reported that in 1939 alone, Utahns spent nearly $4 million in the newly created state liquor stores.96

Despite the welcome revenue from beer sales, consumption failed to reach pre-Prohibition levels both in Utah and across the nation. Due to the near collapse of their industry, coupled with the popularity of soft drinks and cocktails, per capita beer consumption had dipped to 7.9 gallons in 1934, less than half from twenty years earlier.97 In response to the scarcity of demand, industry leaders—including Jacob Ruppert, the owner of the Jacob Ruppert Brewing Company of New York and the longtime president of the United States Brewers’ Association (USBA)— suggested that brewers flood the market with cheap beer that cost American consumers only a nickel per glass.98 He reasoned that pre-Prohibition prices would draw consumers back to their pint glasses.

This strategy, however, proved to hurt small firms that lacked the production capacity and technology to profit from this approach. Small brewers also struggled due to skyrocketing malt prices caused by the nationwide droughts of the 1930s. For many, it was financially impossible to lower their selling price while also paying more for their principal ingredient. Utah’s most celebrated brewer and second vice president of the USBA, Gus Becker, protested against this strategy. At the annual brewers’ convention in 1938, he urged brewers to slow production. Becker, who was in fact a western romantic, compared the race to produce cheap beer in the decade after repeal to the “blind, mad dash of herded cattle that are startled from sleep at night.” Instead, he encouraged cooperation and long-term industry planning. Becker further cautioned his fellow brewers that “over-selling customers in ‘volumania’ is the twin folly to over-expansion.”99 He reasoned that slow growth, rather than the rapid increases in production volume and brewhouse expansions called for by Ruppert’s plan, was far more viable for regional breweries. Becker advocated for quality and product profitability over what he termed “mere bigness.” In many ways, Becker’s approach to brewing foreshadowed the ethos adopted by today’s craft brewers who stress quality over quantity. This practice became a central tenet of Becker’s presidency when he assumed the office following Jacob Ruppert’s death in 1939.

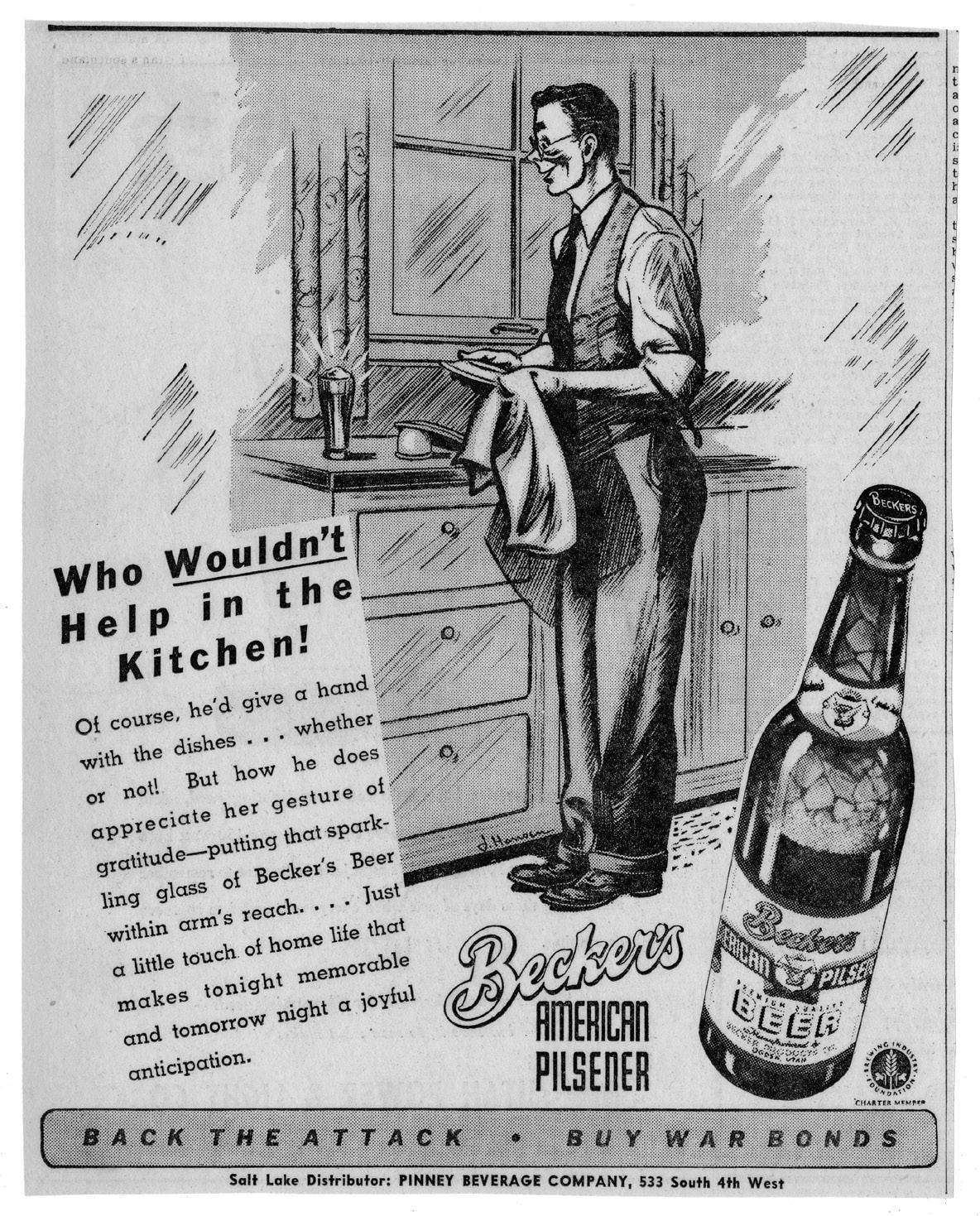

The nation’s brewers elected Gus Becker president of the USBA on October 3, 1939. In his inaugural address “When One Brewer Puts Another Out of Business He May Be Working with the Enemy,” Becker urged cooperation among brewers to prevent a second prohibition. Only by working together and supporting smaller firms, he determined, could the industry remain strong, healthy, and counter their perceived threats of a second prohibition brought on by another war with Germany.100 He argued that small brewers provided valuable links between the industry and the community, helping them maintain a positive image by employing local labor and integrating into the business community. Yet the fact that an increasingly smaller number of large firms in Milwaukee, St. Louis, and New York produced ever more beer suggests that brewers did not respond to Becker’s pleas. The largest firms continued to cut prices and stress production volume, thus increasing their market shares.101 “Mere bigness” won out for now. Despite the struggles between small brewers and their colossal counterparts during the late 1930s and early 1940s, the Beckers once again innovated to grow their business. They joined other brewers in a nationally coordinated advertising campaign to win over American consumers. The USBA decided that beer needed to be viewed as acceptable for home consumption and marketed as a moderate, wholesome beverage. The historian Nathan Corzine shows how this PR strategy is highly visible in ads, which featured men and women in traditional gender roles, the husband performing a stereotypical masculine task while his observant and caring wife provides him with his favorite beer.102 The historian Lisa Jacobson, also analyzing advertisements, suggests that brewers used wartime ads in the 1940s to associate beer with traditional American life to disassociate their product from the infamous saloon. During the war, America’s brewers, under the direction of their trade association, launched a “morale is a lot of little things” campaign to tie the enjoyment of a cold glass of beer with friendship and a homecooked meal. This successfully “repoliticized” beer and laid a foundation for the modern patriotic associations with the beverage.103

Wartime advertisement for Becker’s American Pilsner, 1944. During World War II, American brewers launched a nationally coordinated advertising campaign stressing beer’s importance to American home life and values. This campaign successfully politicized American beer as a patriotic product, something brewers failed to do during the First World War. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Becker Brewing and Malting Company Records Addendum, USU_ CAINE COLL MSS 31.

These themes can also be observed in Becker beer ads in various Utah newspapers. In 1944, the Becker Products Company released an ad featuring a husband at home cleaning dishes with the caption, “Of course, he’d give a hand with the dishes . . . whether or not! But how he does appreciate her gesture of gratitude—putting that sparkling glass of Becker’s Beer within arm’s reach. . . . Just a little touch of home life that makes tonight memorable and tomorrow night a joyful anticipation.”104 In addition to overt references to the “morale is a lot of simple things” campaign, the ad also plays on stereotypical gender roles and appeals to consumer patriotism by encouraging the purchase of war bonds. When marketing beer, the Beckers believed that national messaging would also be effective in Utah.

Once brewers effectively “repoliticized beer,” and no real threat of a second prohibition was evident, the large eastern firms began to ramp up beer production and advertising campaigns, which put most of their remaining small competitors out of business.105 Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Anheuser-Busch, Pabst, Miller, Schlitz, and Coors flooded the American beer market with cheap, heavily advertised beer. Local firms could no longer maintain a price advantage or compete with the slick marketing campaigns of the large firms, and the number of breweries declined rapidly. The two local breweries in Utah that had survived Prohibition—Becker Brewing Company of Ogden and the Fisher Brewing Company of Salt Lake City—competed for sales in the fierce beer market until Fisher closed in 1957.106 Nationwide, fewer firms cornered a larger share of the beer market: the five largest breweries held 24 percent of the market share in 1950 and a full 85 percent in 1985.107

While financial data for the Becker Products Company is rather limited, extant documents from its last two decades show the firm in steep decline. Gus Becker, the company’s flamboyant and charismatic president, died of a heart ailment in 1947.108 His brother Albert succeeded him as president until his death in 1961.109 The few remaining financial documents from the company show that the 1950s were not a prosperous time for regional brewers. From fiscal years 1958 to 1959, Becker beer sales decreased by 7,563 barrels of beer, shrinking from 57,567 to 50,004. As a result, their net profits tumbled 26 percent, falling from $11,308 to only $8,394.110 The Beckers were not alone in their losses, as regional breweries across the country saw their profits slowly dry up as consumers turned to national brands.111 In the 1960s and 1970s, many American regional breweries shuttered their doors.

While the Beckers’ beer sales plummeted, alcohol consumption in Utah did not. From 1947 to 1949, the state collected nearly $600,000 each year in tax revenue from beer sales.112 In fact, in fiscal year 1956, the Utah Foundation reported that state consumers spent a combined nearly $3 million on alcohol and tobacco, most from booze.113 Unfortunately for the local brewing industry, consumers appeared to be purchasing out-of-state brews and consuming more spirits and less beer.114 In 1964 the Becker Products Company could no longer sustain profits among the tough competition from national brands and a shrinking consumer base. The Becker factory ceased production, and the company sold off its assets through the 1960s and 1970s. Twenty years later, the city of Ogden demolished the abandoned building that had once been Utah’s longest continually operating brewery.115 When placed in the broader national context, the Beckers’ story demonstrates that national industry trends had a profound impact on Utah’s regional brewers.

Fortunately for today’s many microbreweries and their thirsty customers, local brewing only temporarily ceased in Utah and the United States. In the 1980s the craft beer revolution began to pick up steam, and for the first time, after thirty-five consecutive years of decline, the United States added breweries in 1982.116 In 1986, Greg Schirf established the state’s first craft brewery, Wasatch Brewery, in Park City. Since then the number has only increased. As of 2019, Utah boasted forty-two craft breweries. Together they produce nearly two hundred thousand barrels of beer each year.117 Even though modern Utah has a reputation for difficulty in acquiring alcohol, the state continues to follow national trends, offering award-winning craft brews to those willing to partake of them, including some members of the LDS church.118 Recent scholarship suggests that many Mormons hold a more nuanced stance toward alcohol than might be expected, and that Utah politicians are liberalizing the state’s notoriously draconian liquor laws in response to demands from the national beer industry. On November 1, 2019, Utah increased the legal alcohol content limit on beer sold in grocery stores and gas stations from 3.2 percent to 5 percent. This marked the first time the state increased legal alcohol limits since the repeal of Prohibition.119 This move falls in line with Oklahoma and other states that have removed their 3.2 percent restrictions.120 As the history of the Becker Brewing and Malting Company reveals, Utah shares many common practices of alcohol consumption with the wider American public, including a general acceptance of beer consumption. Before state prohibition in 1917, the LDS church allowed members who consumed alcohol to remain in good standing due to the perceived health benefits of spirits. In fact, current church policies regarding alcohol consumptions were not broadly enforced until prohibition became the law nationwide. The Becker Brewing and Malting Company manufactured products that reflected consumer tastes and kept abreast of industry technological innovations and marketing techniques. Further, as this article illustrates, it was the formation of the national brewing oligopoly that played a more significant role in putting the Beckers’ brewery out of business than local political and religious factors.

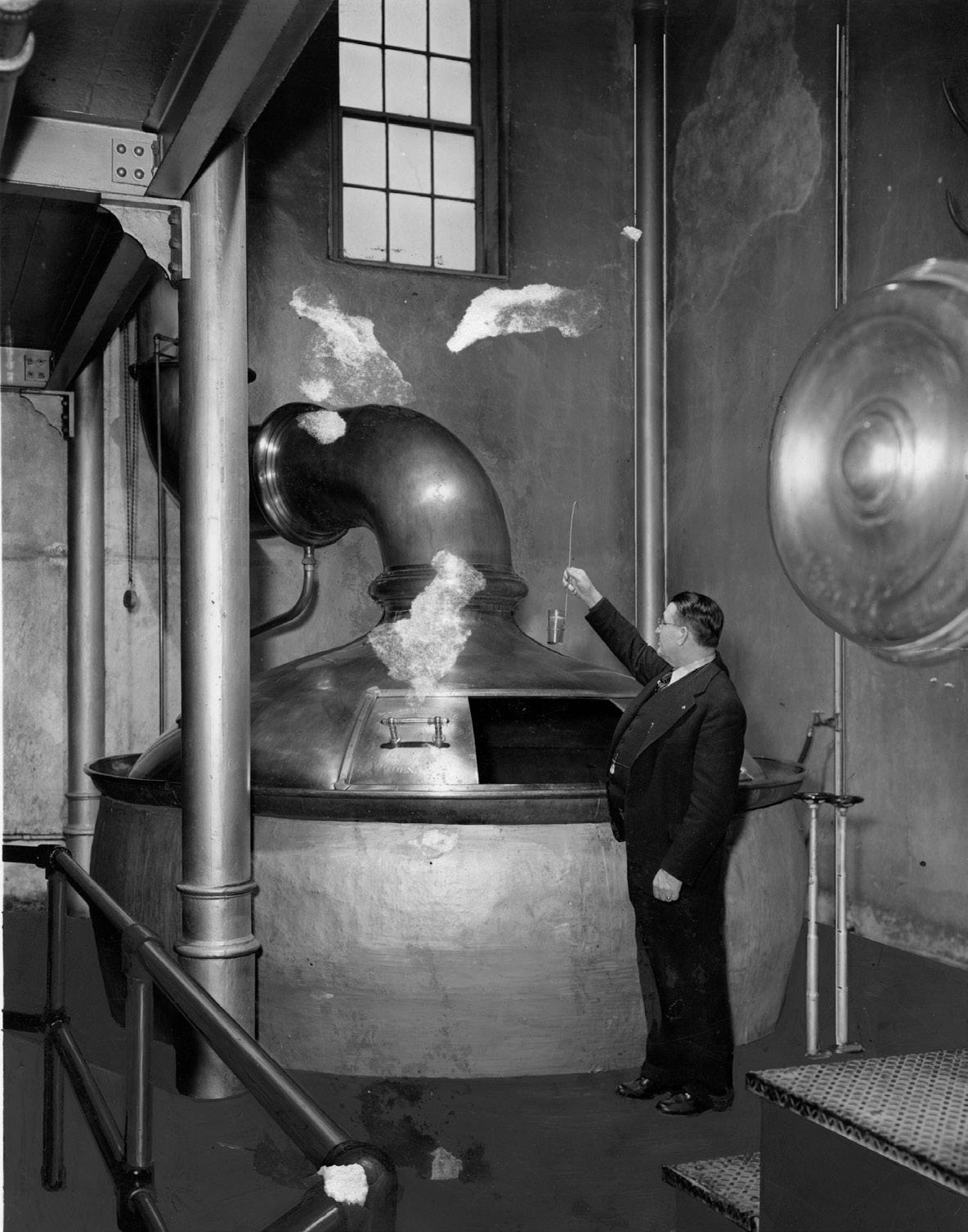

Albert E. Becker inspects the beer from the brewing kettle in the new family brewery, undated. Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections & Archives, Gustav Lorenz Becker Photograph Collection, USU_P0361.

Despite its low rankings for ease of alcohol consumption, Utah and its colorful history may surprise those who take a closer look. Brewpubs and small regional breweries have opened and expanded throughout the state, and Utah’s strict liquor laws have shifted, albeit slowly, to mirror policies of states possessing similar regulations on alcohol sales. When one takes a step back and places the state’s beer history within a wider context, Utah may not appear so peculiar after all.

Notes

1. “Hotel Arrivals,” Ogden Standard, July 9, 1891.

2. “Ogden’s New Brewery,” Ogden Standard, March 15, 1891.

3. “New Brewing Company,” Ogden Standard, May 25, 1892.

4. Samuel A. Batzli, “Mapping United States Breweries 1612 to 2011,” in The Geography of Beer, edited by Mark Patterson and Nancy Hoalst-Pullen (Dordecht: Springer, 2014), 38. Brewers at the turn of the century used the term “near beer” to describe non-alcoholic beer.

5. Brewers’ Association, “Historic U.S. Brewery Count,” accessed March 20, 2020, https://www.brewersassociation .org/statistics-and-data/national-beer-stats/.

6. “Historic brewery’s saga ending,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, 1984, box 7, fd. 8, series 3, Becker Brewing and Malting Company records, Caine MSS 31, Utah State University Merrill-Cazier Library, Logan, Utah (hereafter BBMC records).

7. Matt Canham, “Salt Lake County is becoming less Mormon—Utah County is headed the other direction,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 16, 2017.

8. Christopher Matthews, “The 3 Best and 3 Worst States in America for Drinking,” Time Magazine, December 5, 2013.

9. The Zion Curtain refers to a law in Utah requiring alcoholic drinks to be poured and mixed behind a barrier, out of sight of restaurant patrons. In 2020, the Utah legislature also voted to increase the alcohol content of beer purchased in grocery stores from 3.2 percent to 5 percent. Amy Held, “Utah’s ‘Zion Curtain’ Falls and Loosens State’s Tight Liquor Laws,” National Public Radio, July 2, 2017, accessed April 26, 2020, https://www .npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/07/02/535259524 /utahs-zion-curtain-falls-and-loosens-states-tight -liquor-laws.

10. Ashton Edwards, “See where Utah ranks on list of ‘drunkest’ states in U.S.,” Fox13, March 18, 2015, accessed March 17, 2020, https://fox13now.com/2015/03/17/map -shows-which-state-has-the-most-bars-per-capita/; Erin Blakemore, Smithsonian Magazine, July 5, 2017, accessed April 26, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag .com/smart-news/utah-just-did-away-liquor-hiding -curtains-180963949/.

11. Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (1958; Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press, 1993), xxii.

12. The American Brewer, vol. 67 no. 2 (1934), 15. Gus Becker became president of the United States Brewers’ Association in 1939. The organization’s past presidents and board members consisted of some the most iconic names in brewing, including the Busch, Miller, Coors, and Pabst families.

13. Several non-academic historians have written brewing histories for popular audiences. Some of these works fail to meet academic standards of source citation and context. Despite these shortcomings, popular works offer valuable insights into local history and provide an excellent starting place for anyone interested in researching their region’s brewing heritage. A few examples include Dell Vance, Beer in Beehive: A History of Beer in Utah (Salt Lake City: Dream Garden Press, 2006); Dane Hucklebridge, The United States of Beer: The Freewheeling History of the All-American Drink (New York: William Morrow, 2016). Arcadia Publishing’s American Palate series features a host of brewing history for different states and cities written by popular authors.

14. For works on American brewing history, see Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1944); Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962); A. M. McGahan, “The Emergence of the National Brewing Oligopoly: Competition in the American Market, 1933–1958,” Business History Review 65, no. 2 (1991): 229–84; Martin Stack, “Local and Regional Breweries in America’s Brewing Industry, 1865 to 1920,” Business History Review 74, no. 3 (2000): 435–63; Maureen Ogle, Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer (Orlando: Haricourt Inc., 2006); Lisa Jacobson, “Beer Goes to War: The Politics of Beer Promotion and Production in the Second World War,” Food, Culture, and Society 12, no. 3 (2009): 275–312; Martin Stack, “Was Big Beautiful? The Rise of National Breweries in America’s Pre-Prohibition Brewing Industry,” Journal of Macromarketing 30, no 1 (2010): 50–60; Nathan Corzine, “Right at Home: Freedom and Domesticity in the Language and Imagery of Beer Advertising, 1933–1960,” Journal of Social History 43, no. 4 (Summer 2010): 843–66; Ranjit S. Dighe, “A Taste for Temperance: How American Beer Got to Be So Bland,” Business History 58 (2016), 752–84.

15. For works on Prohibition, see Norman H. Clark, Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of Prohibition (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976); W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); Lori Rotskoff, Love on the Rocks: Men, Women, and Alcohol in Post-World War II America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002); Lisa McGirr, The War On Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016); W. J. Rorabaugh, Prohibition: A Concise History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

16. “John Becker Dies in California City,” obituary, 1918, p. 232, box 5, fd. 38, Gustav Lorenz Becker photograph collection, P0361, Utah State University Merrill-Cazier Library, Logan Utah (hereafter Becker photograph collection).

17. Library of Congress, “Germans in America,” accessed November 2, 2017, https://www.loc.gov/rr/european /imde/germchro.html. German immigration was driven by a number of factors, including the failed revolution of 1848 and economic opportunities. For a study of German immigration, see Don Heinrich Tolzmann, The German American-Experience (Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2000).

18. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 56.

19. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 6.

20. US Senate, Report and Hearings of the Subcommittee on the Judiciary United States Senate Relating to the Charges Made Against the United States Brewers’ Association and Allied Interests, S. Res. 307 and 439, Doc. No. 62, 66th Cong., 1st Sess. (1919), 1:1116.

21. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 15. Ale, which is brewed in the English tradition, uses a top fermenting yeast and does not require the cold storage of German-style lager.

22. Rorabaugh, Prohibition: A Concise History, 2.

23. Rorabaugh.

24. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 12–17, 71.

25. West, “Beer: A Western—and Human—Tradition,” Journal of the West 55 (Spring 2016): 15. Per capita consumption increased from 2.3 gallons in 1840 to 23.6 gallons by 1900.

26. Doctrine and Covenants 89:5.

27. For work on the Word of Wisdom, see Thomas G. Alexander, “The Word of Wisdom: From Principal to Requirement,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 14 (Autumn 1981): 78–88; Paul Y. Hoskisson, “The Word of Wisdom in Its First Decade,” Journal of Mormon History 38 (Winter 2012): 131–200; John E. Ferguson III, Benjamin R. Knoll, and Jana Riess, “The Word of Wisdom in Contemporary Mormonism: Perceptions and Practice,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51 (Spring 2018): 42.

28. Hoskisson, “The Word of Wisdom in Its First Decade,” 131–200.

29. Many Europeans and Americans also consumed fermented beverages and spirits because they provided a safer source of hydration than the brackish and contaminated water found in urban and industrial centers. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 6.

30. Hoskisson, “The Word of Wisdom in Its First Decade,” 180, 189, 199.

31. Hoskisson, 199.

32. Richard White, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865–1896 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 385.

33. “Obituary of John S. Becker, 1918,” p. 232, box 5, fd. 38, Becker Photograph Collection.

34. Brewers’ Association, “Historic U.S. Brewery Count,” accessed December 21, 2020, https://www.brewers association.org/statistics-and-data/national-beer -stats/.

35. McDaniel, “Ogden: The Junction City of the West,” 2, 39–40.

36. “Prospect of a Brewery,” Ogden Daily Standard, March 7, 1890; E. A. McDaniel, Ogden: The Junction City of the West (Salt Lake City: Tribune Print, 1888), 1.

37. The Salt Lake Brewing Company was established in Salt Lake’s Tenth Ward in 1873. The Fisher Brewery opened in 1884. “City News,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 5, 1873; “The New Brewery,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 1, 1885.

38. “Original Becker Brewing and Malting Company Brew Plant, c. 1893,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 26, 2020, http://exhibits.usu.edu/items/show/12856.

39. “Whence Comes Good Beer,” Ogden Daily Standard, June 17, 1897.

40. The new brewery was situated along Lincoln Ave near the Ogden River in downtown Ogden. “Larger Brewery Planned,” Ogden Daily Standard, February 4, 1905; “Banquet for Traveling Men,” Ogden Evening Standard, June 8, 1911.

41. “Larger Brewery Planned,” Ogden Daily Standard, February 4, 1905; National Parks Service, “Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company Brewery Complex,” National Register of Historic Place Form, March 15, 1986, accessed April 26, 2020, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/Get Asset/NRHP/86000793_text; National Parks Service, “Blatz Brewery Complex,” National Register of Historic Place Form, November 29, 1990, accessed April 26, 2020, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/590a9e4e-3630 -495c-87c0–25aefc36bed6.

42. “Will Double Capacity,” Salt Lake Telegram, February 15, 1905.

43. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 125–26.

44. Anheuser-Busch Brewing Association to the Becker Brewing and Malting Company, December 4, 1895, addendum, item 6, box 1, fd. 17, series 3, BBMC.

45. Price fixing agreement, July 26, 1897, addendum, item 1, box 4, fd. 9, series 3, BBMC.

46. Emil Hansen to Becker Brewing and Malting Company, July 2, 1914, box 16, fd. 6, series 1, BBMC.

47. “Becker Brewing Co. Section,” Ogden Daily Standard, January 1, 1896.

48. Stack, “Local and Regional Breweries in America’s Brewing Industry,” 435.

49. Tied-House Contract, April 14, 1893, box 4, fd. 9, series 4, BBMC records.

50. West, “Beer,” 15.

51. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 139–40.

52. Brent G. Thompson, “‘Standing between Two Fires’: Mormons and Prohibition, 1908–1917,” Journal of Mormon History 10 (1983): 36. Utah’s population in 1910 stood at approximately 373,000. US Census Bureau, “Utah Resident Population, 1850–2000,” 2000, accessed November 3, 2017, https://www.census.gov/dmd/www /resapport/states/utah.pdf.

53. Ashton Edwards, “See where Utah ranks on list of ‘drunkest’ states in U.S.”

54. Brewers’ Almanac (1940), 23.

55. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 139–40.

56. West, “Beer: A Western—and Human—Tradition,” 14–23.

57. McGirr, The War on Alcohol, 15–16; Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 89.

58. Hearing, S. Res. 307 and 439, 1115.

59. Thompson, “Standing Between Two Fires,” 35.

60. Thompson, 35. The “Federal Bunch” was a group of leading Utah Republicans in the early twentieth century, who, under Smoot, Spry, and Smith, received positions through political patronage.

61. Alexander, “The Word of Wisdom,” 78.

62. Edgar Brossard to the Becker Brewing and Malting Company, August 27, 1914, sales order, box 15, fd. 64, series 1, BBMC records; Edgar B. Brossard Papers, finding aid, MSS 004, Utah State University Merrill-Cazier Library, Logan, Utah. A barrel of beer refers to a thirtyone-gallon container and is the standard unit of measurement in the brewing industry.

63. “Beer Best Brain Food, Says Prof. Chandler,” Salt Lake Herald–Republican, May 15, 1915.

64. Becker Brewing and Malting Company, “Advertisement for Becker’s Best (2 of 29), 1906,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed March 17, 2020, http://exhibits.usu .edu/items/show/12738.

65. “East or West, It Is The Best,” Ogden Daily Standard, July 24, 1917.

66. Rorabaugh, A Short History of Prohibition, 43.

67. “Temperance,” Iron County Record, April 23, 1915.

68. Thompson, “‘Standing between Two Fires,’” 35, 37–39, 41–49.

69. Hearing, S. Res. 307 and 439, 1116.

70. Thompson, “‘Standing Between Two Fires,’” 51.

71. Ferguson III, Knoll, and Reiss, “The Word of Wisdom in Contemporary Mormonism,” 42.

72. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic, 117–19.

73. Amy Mittleman, Brewing Battles: A History of American Beer (New York: Algora Publishing, 2008), 71–96.

74. Tammy M. Proctor, “‘Patriotic Enemies’: Germans in the Americas, 1914–1920,” in Germans as Minorities during the First World War, edited by Panikos Panayi (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, 2014), 226–27. For more on German–Americans during the war, see Christopher Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

75. US Congress, Senate, 1919, Brewing and Liquor Interests and German and Bolshevik Propaganda: Report of the Subcommittee on the Judiciary United States Senate Relating to the Charges Made Against the United States Brewers’ Association and Allied Interests, S. Res. 307 and 436, Doc. No. 61, 65th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1–3; Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 179–81.

76. Ogden Daily Standard, April 18, 1917.

77. “Utah Goes Dry,” Utah Brews: The Untapped Story of Ogden’s Becker Brewing and Malting Company, USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 12, 2020, http:// exhibits.usu.edu/exhibits/show/beckerbrewing/state prohibition.

78. Chester C. Wilcox, “Liquidation of the Becker Brewing and Malting Company Legal Contract, 1919,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 12, 2020, http://exhibits .usu.edu/items/show/12841. The Eighteenth Amendment would be ratified the following day (January 16, 1919).

79. Advertisement of Becker’s Best, 1911, addendum, item 4, box 3, folder 1, series 3, BBMC records.

80. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 183.

81. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 209.

82. Advertisement for Becker’s Becco, c. 1920, addendum, item 41, box 3 folder, 1, series 3, BBMC records; Advertising pamphlet for Becco, c. 1925, addendum, item 1, box 3, fd. 18, series 3, BBMC records.

83. Samuel A. Batzli, “Mapping United States Breweries 1612 to 2011,” 38.

84. “Becker Enterprise Pioneer Brewers,” Ogden Standard, July 20, 1917; “Becker Products Display One of State Fair Features,” Salt Lake Telegram, October 5, 1924. Becker drinks won ribbons at the state fair held in 1920. “Becco Wins Blue Ribbon at State Fair,” Ogden Standard-Examiner, October 10, 1920.

85. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company, 333; Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 207.

86. Letter from Heber J. Grant to Gustav L. Becker, January 6, 1928, pg. 107, book 1, box 1, Becker photograph collection.

87. Ogle, Ambitious Brews, 196; McGirr, The War on Alcohol, xx.

88. Historical note, Convention to Ratify the 21st Amendment, Administrative Records, Series 6300, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah; John Dinan and Jac C. Heckelman, “Support for Repealing Prohibition,” Social Science Quarterly 95 (September 2014): 636–51.

89. Helen A. Papanikolas, “Bootlegging in Zion: Making and Selling the ‘Good Stuff,’” Utah Historical Quarterly 53 (Summer 1985): 272.

90. Ogle, Ambitious Brew, 192.

91. “Questions and Answers on Repeal,” Provo Evening Herald, October 27, 1933; “Blood is Urged to Save Utah’s Beer Industry,” Salt Lake Telegram, April 12, 1933.

92. “Ogden Brewer Gets First Beer Permit,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 26, 1933.

93. Becker Products Company, “Becker’s Golden Jubilee Booklet, 1940,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 12, 2020, http://exhibits.usu.edu/items/show/12815; Becker Brewing and Malting Company, “Advertisement for Becker’s Uinta Club (1 of 3), 1938,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 12, 2020, http://exhibits .usu.edu/items/show/12780.

94. Dave Smith, “Evanston’s 3.2 Percent Beer Celebration,” Rich Country Reaper, May 26, 1933.

95. Brewers’ Almanac (1940), 41, 68.

96. “Liquor Revenue of Utah Listed,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 18, 1939.

97. Brewers Almanac (1940), 27, 33–34. In 1939, per capita consumption of beer in the United States hovered near 12 gallons, down from 21 gallons in 1914. Per capita consumption in Utah remained close to the national average throughout the 1930s. Per capita consumption in Utah rose from 6 gallons to 8.6 by 1939. In comparison, the per-capita consumption nationally increased from 7.9 in 1934 to 12.3 gallons by the end of the decade.

98. Jacob Ruppert, “Ruppert Urges Five-Cent Beer,” American Brewer 67, no. 10 (October 1934), 13.

99. Gustav L. Becker, “Brewery Management,” American Brewer 71, no. 2 (February 1938), 11.

100.“Modern Brewer Magazine, 1939,” book 1, box 11, Becker Photograph Collection.

101. McGahan, “The Emergence of the National Brewing Oligopoly,” 231. From 1939 to 1958 the largest five breweries in the nation nearly doubled their market share from 16 percent to 30 percent.

102.Corzine, “Right at Home,” 843–44.

103.Jacobson, “Beer Goes to War,” 276–80.

104.Advertisement for Becker’s American Pilsner, 1944, addendum, item 61, box 3, fd. 1, series 3, BBMC records.

105.Corzine, “Right at Home,” 858.

106.The Fisher Brewing Company operated from 1884 until 1920 and from 1934 to 1957 when the company was sold to California brewer Lucky Lager. The greatgrandchildren of the firm’s founder, Albert Fisher, reopened the family brewing business in Salt Lake in 2017. Christopher Smart, “What Ever Happened to . . . Fisher Brewery?,” Salt Lake Tribune, August 30, 2016, accessed December 23, 2020, https://archive.sltrib.com /article.php?id=4270530&itype=CMSID.

107. Batzli, “Mapping United States Breweries,” 39.

108.“Pioneer Brewer Dies at Ogden of Heart Ailment,” Salt Lake Telegram, January 13, 1947.

109.“Albert Becker Death Certificate,” Department of Health, Office of Vital Records and Statistics Death Certificates, Series 81448, Utah State Archives, accessed April 26, 2020, https://archives.utah.gov/research /indexes.

110. Becker Products Company, “Becker Products Company Financial Documents, 1959 to 1960,” USU Digital Exhibits, accessed April 26, 2020, http://exhibits.usu .edu/items/show/12818.

111. Regional brewery financial records are scarce. The Becker Product Company’s marginal returns in Utah, however, mirrors the financial woes experienced by another regional brewery in Defiance, Ohio. Untitled newspaper clipping, October 22, 1938, Scrapbook, 1938–2006, Oversized Box 2, Diehl Inc. Records, MS 1057, Jerome Library, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio; Financial Records, 1949, Oversized Box 1, Diehl Inc. Records.

112. Utah Foundation, “Utah State government financial summary for the years 1948–49 and 1950–51 Bienniums, report no. 51, 1949,” https://digitallibrary.utah.gov /awweb/main.jsp?flag=browse&smd=1&awdid=7.

113. “Tobacco and Alcohol Sales Bring Tax Money of $19.8 Million in Utah,” Times–Independent, May 2, 1957.

114. Becker Products Company, “Becker Products Company Financial Documents, 1959 to 1960,” USU Digital Exhibits.

115. “Historic brewery’s saga ending,” Ogden Standard–Examiner, 1984, box 7, fd. 8, series 3, BBMC records.

116. Batzli, “Mapping United States Breweries,” 40.

117. Brewers’ Association, “Utah Craft Brewing Statistics 2019,” accessed April 26, 2020, https://www.brewers association.org/statistics/by-state/?state=UT.

118. Recent scholarship suggests that while the LDS church’s stance on alcohol has remained unchanged since 1921, some contemporary Mormons still practice a nuanced interpretation of the scripture. Ferguson III, Knoll, and Reiss, “The Word of Wisdom in Contemporary Mormonism,” 50.

119. Lindsay Whitehurst and the Associated Press, “Utah Gets Serious About Beer, As State Law Ups Alcohol Limit,” Fortune, accessed March 18, 2020, https:// fortune.com/2019/11/01/utah-beer-percentage-utah -beer-law-change-2019-utah-beer-funeral/.

120.Kathy Stephenson, “Another state ditching 3.2 beer, what’s in store for Utah?,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 9, 2016.