TEACHING FOR NEXT

2022–2023

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

TEACHING SPACES TRIBUTE

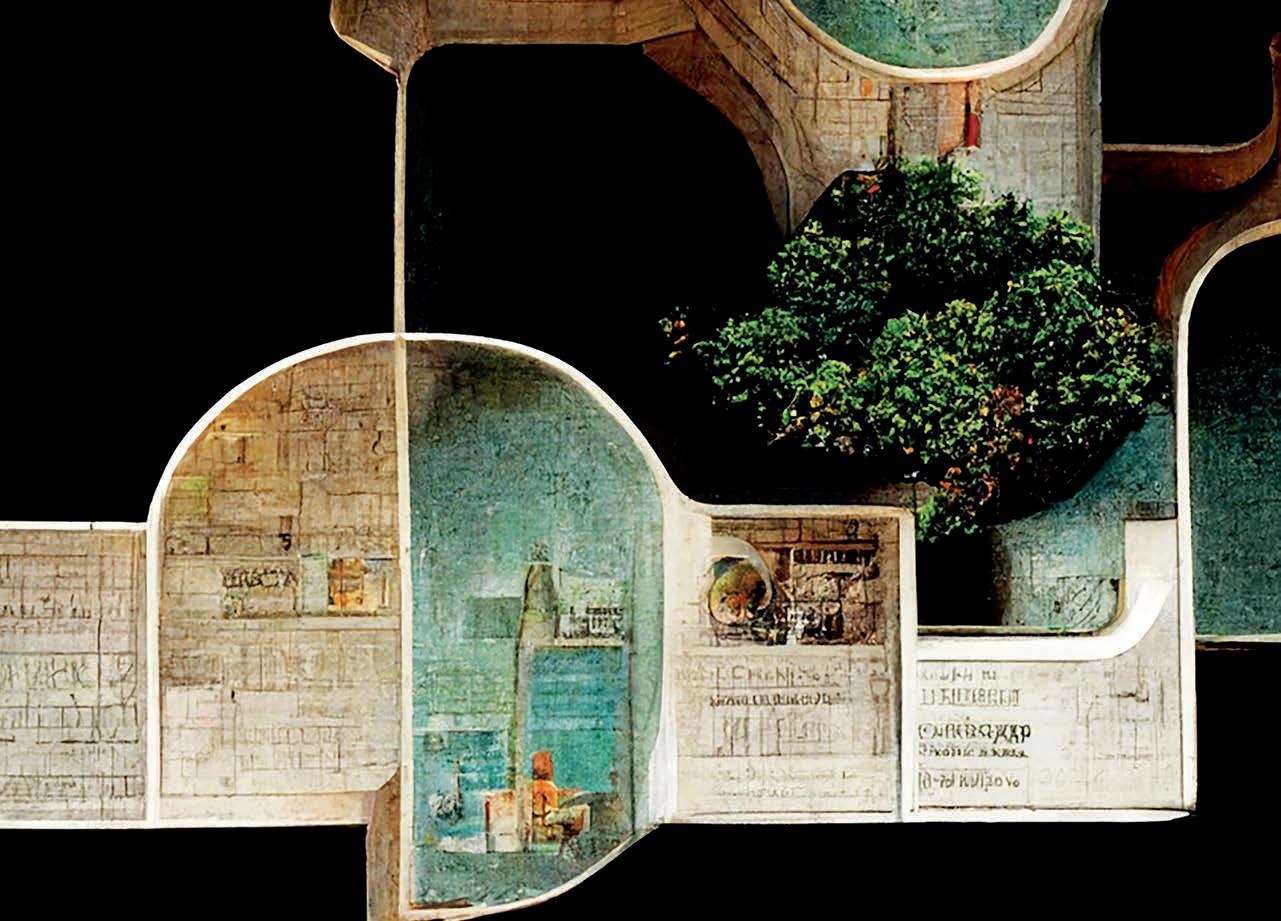

Presented throughout this issue is a collection of images of the School of Architecture buildings, studios, and courtyards as an extension of the Teaching for Next theme and a tribute to the spaces where we teach and learn.

EDITOR Elizabeth Danze

MANAGING EDITOR

Bridget Gayle Ground ASSISTANT EDITOR Emma Margulies

DESIGN Tenderling | tenderling.com

TO OUR READERS

We welcome ideas, questions, and comments. Please share your thoughts with us.

CONTENTS

310 Inner Campus Drive, B7500 Austin, TX 78712-1009 512.471.1922 | soa.utexas.edu

LEFT Teaching Spaces Tribute: Goldsmith Hall’s Eden and Hal Box Courtyard during Curtains installation, 2013. Image by Alison Steele.

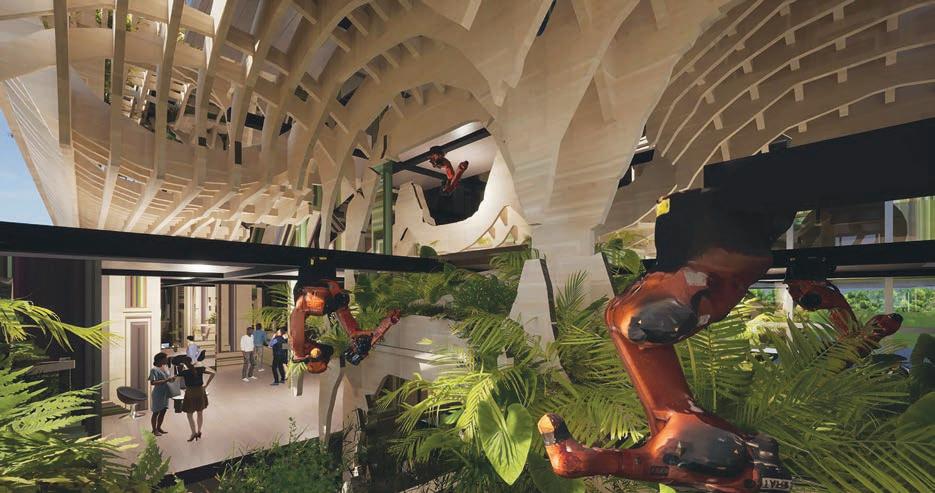

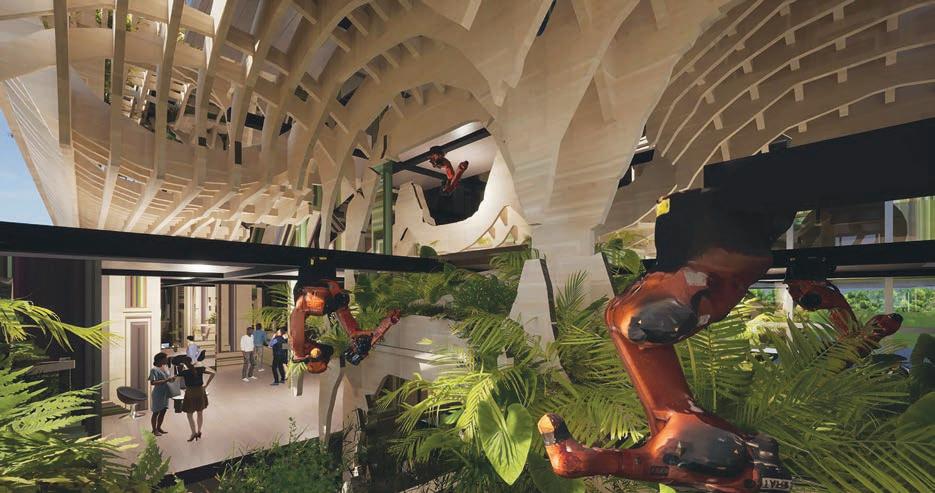

COVER Roofscape design by Kory Bieg with Midjourney AI, 2022.

02 D EAN’S MESSAGE D. Michelle Addington 04 CONTRIBUTORS 08 EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION Elizabeth Danze 10 R EFLECTIONS ON TEACHING: 47 YEARS AND COUNTING

Michael Benedikt, Michael Garrison, and Larry Speck interviewed by Richard Cleary 16 R EFLECTIONS ON TEACHING: 31 YEARS AND COUNTING Kevin Alter, John Blood, Elizabeth Danze, and David Heymann interviewed by Richard Cleary 22 N OT SO LIKE-MINDED Francisco Gomes 28 PROFESSIONAL RESIDENCY PROGRAM: EXPECTED OBJECTIVES AND SOME UNEXPECTED OUTCOMES Nichole Wiedemann 34 R EFLECTIONS ON STUDY ABROAD: THE PARIS STUDIO Igor Siddiqui 40 R ACE AND ARCHITECTURE AT UT: RESEARCHING AND TEACHING DIFFICULT AND CONTESTED HISTORIES IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Tara A. Dudley

48 RE-DRAWING CONNECTIONS: DESIGN ADVOCACY IN SECTION Maggie Hansen 54 PEDAGOGY FOR A TURBULENT WORLD: A PRACTICE OF RADICAL INTERDEPENDENCE Patricia A. Wilson 58 CRITICAL PEDAGOGY, ARTS-BASED RESEARCH, AND COMMUNITY-BASED PLANNING AND DESIGN: EXPERIENCES FROM AUSTIN AND THE DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

Bjørn Sletto, Samira Binte Bashar, Alexandra Lamiña, León Staines, Raksha Vasudevan 64 DIGITAL LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE’S EXTENDED REALITY Hope Hasbrouck and Robert Stepnoski

70 STUDYING ARCHITECTURE AFTER AI Daniel Koehler 76 ALUM INTERVIEW

Andrea Roberts interviewed by Elizabeth Danze 80 PHILANTHROPY

1

DEAN’S MESSAGE

D. MICHELLE ADDINGTON

About twenty or more years ago, while I was teaching at another university, my faculty col leagues and I were reviewing the accreditation criteria for architecture degrees when we came upon a new requirement that students should have an “awareness” of non-Western architec ture. Somewhat concerned as it meant that we had to review syllabi to specifically mark where such an exposure occurred, we were not too terribly inconvenienced as we had good exam ples of contemporary Japanese architecture peppered throughout our courses, particularly since so many of the featured architects had either been educated at our university or at least in the same tradition. Clearly, we missed the point of the requirement.

That first criterion created a toehold that opened a tiny crack in the periphery of our curricula, and it grew over the years as the re quirement was further codified and expanded. Students were introduced to stepwell con structions in India, and studio travel began to include Asia and Latin America, thus chipping away at the legacy of the Grand Tour of Italy and France. Exposure to the larger world, how ever, did little to displace the center tent pole of canon which remained firmly grounded by its classical origins in Western Europe, as well as narrowly bracketed by the lineage stemming from those origins. Indeed, I well remember an intense argument at another university after students demanded to know why no buildings designed by women or architects of color were included in a list of seminal examples of architecture given to every first year student. The rejoinder from so many—too many—was that this was, for good or for naught, simply a fact and that political correctness should not factor into the determination of proper prece dents. Eventually, Pritzker Prize winner Zaha Hadid’s Vitra Fire Station (in Germany) was added to the list to quell the discontent. The periphery might have begun to diversify but the center remained untouched.

What many of us did not realize as we were collecting non-Western examples to include in our classes was that there was a larger discourse regarding questions of the “other.” Why did the long history of building in Italy constitute Architecture with a capital “A” while the even longer history of building in China was relegated to the vernacular, as such little “a” architecture? Why were the Gothic cathedrals of France known, studied, and drawn by every student while the temples of other religions in Asia, Africa, and Meso-America were con sidered as idiosyncratic cultural relics? Why does every urban design curriculum devote a segment to Cerdà’s plan for Barcelona, but not to the city plan of Teotihuacán? The advent of decolonization put into stark relief how our narrow precedents from even narrower origins led us through two thousand years of focusing on the tiniest slivers of the built environment. As this discourse grew, so too did the reckon ing of who and what we have neglected: the “other,” which is essentially everything else we had fundamentally overlooked even insofar as we spent every day of our lives in this complex and diverse environment. While the tradi tionalists in our midst hewed closely to settled canon—albeit were willing to offer up a seat at their table to allow these other discourses to selectively filter in—the rest of us realized we had been sitting at the kids’ table all along. And while there remain many who think that these discourses are but a fad, a distraction, there are many more of us who are wondering why we had been so resistant to embrace our world as it is in all of its manifold complexity and envision how we could make it better rather than keep clinging to a single, simplified version of how we imagined it used to be.

About thirty or more years ago, when I was pursuing my graduate studies in architecture, our field was in the midst of a sea change due to the introduction of digital technologies. We still had our own drafting tables in the studio, but spent as much time in the computer lab teaching ourselves the software that was

rapidly emerging and changing. Eventually, a decision was made that every student would be required to take an introductory course in computer-aided design, and drafting tables across the country in universities as well as in firms were replaced with computer monitors and advanced processors. This was not without lament, anger, and debate. Many labeled the computer as heralding the end of the design process as we knew it; others believed that there was an ineffable quality to design that could only be manifested by the tactile engage ment of hand and pencil to line and paper. In conversations, lectures, and symposia, the allegiance to hand drawing emerged again and again all while digital models and methods were rapidly transforming our practices. The most fervent adherents to hand drawing also tended to revere classical architecture, even though drawing was not a common design or construction method until the Renaissance.

Digital methods and tools opened up vast new territories of collaboration—not only with other architects worldwide, but also with other disciplines. Digital models integrate with algo rithms for advanced simulations of structural, thermal, and lighting performance under a multitude of scenarios, and also integrate with platforms for verification, fabrication, and purchasing. A change in the thickness or property of a material would set off a cascade of changes that could affect every aspect of the

2 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

Tribute:

design and construction process when we were still drafting, whereas now there is real-time updating and analysis across every single docu ment. Most importantly, digital methods allow us to fold in so much more information while providing even greater opportunities to exper iment. Nevertheless, I was part of a conversa tion this summer with two firm principals in New York who were insistent that good design had to come from the hand of the designer and not from the computer. Similar to the canon debate, this question about method also differ entiates between the center tent pole of hand drawing and the expanded field opened up by digital (aka “other”) technologies.

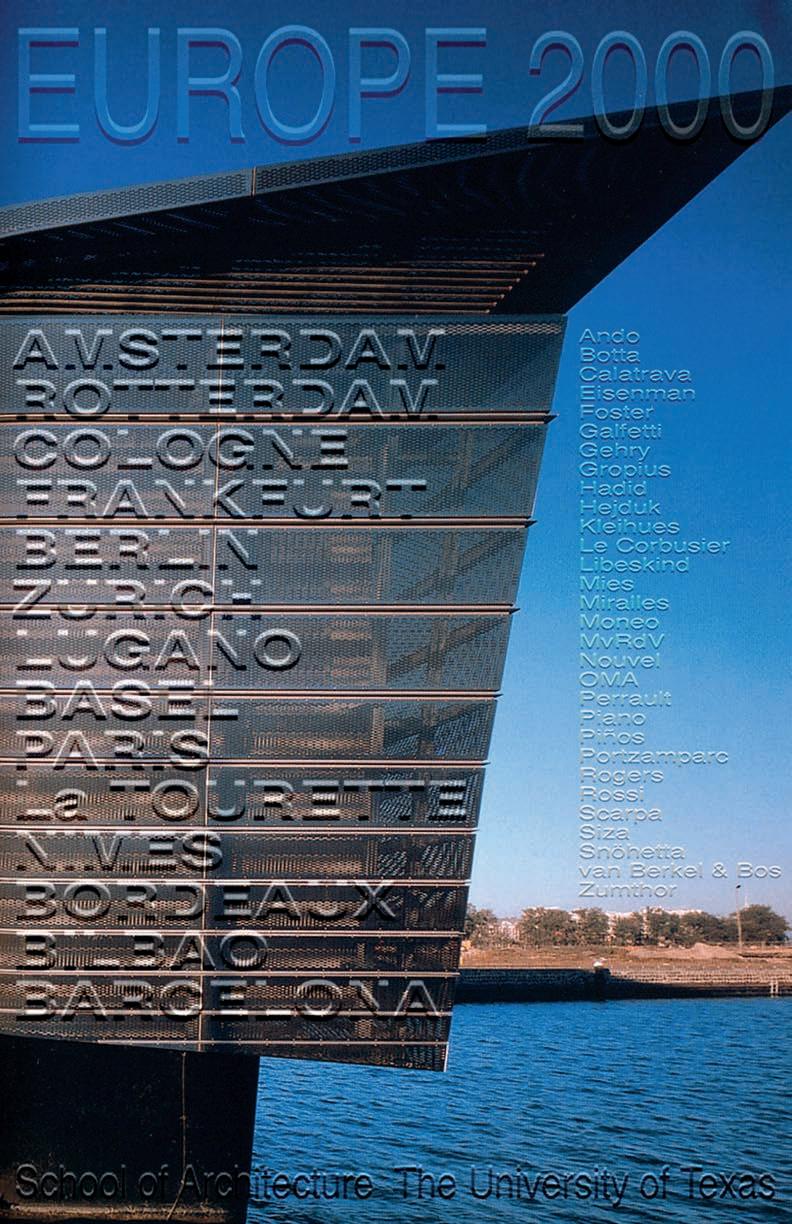

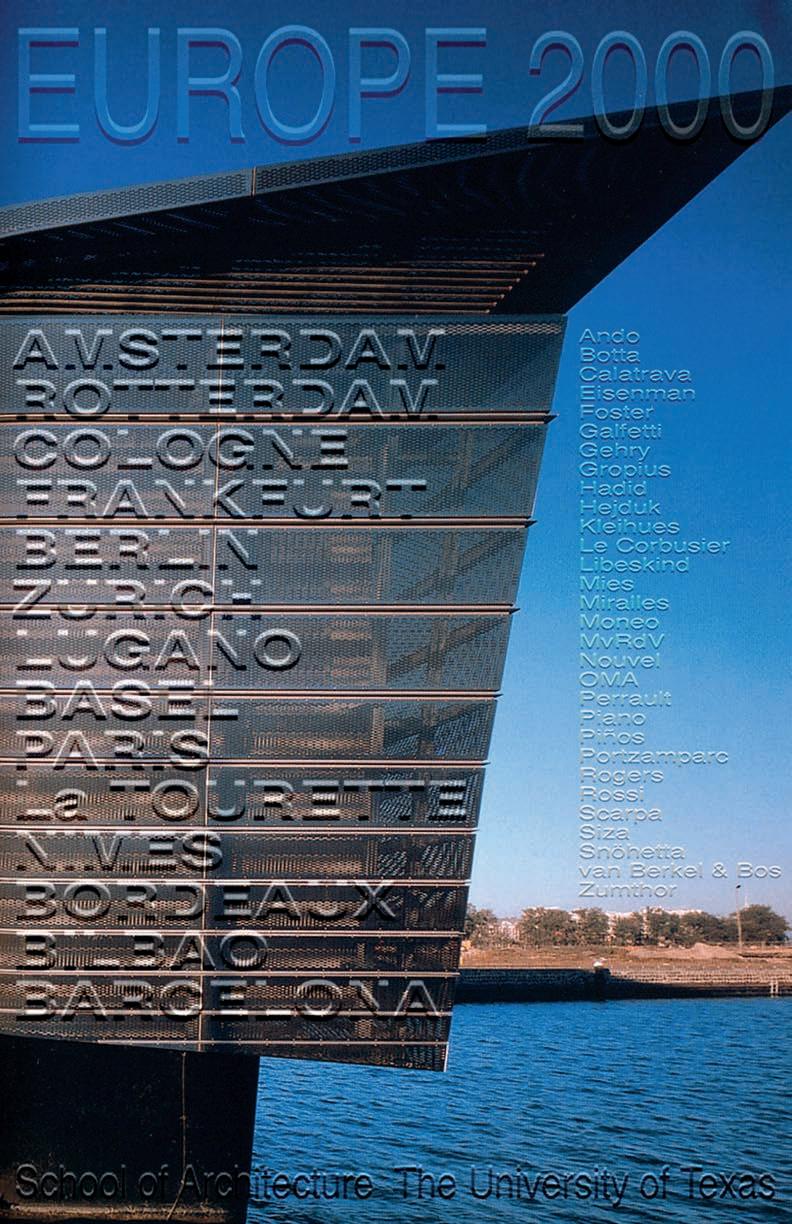

One might conclude from the above that architecture is resistant to change. This would be wrong, as there are few fields that have changed and adapted to rapidly shifting demographics, economies, technologies, and societies as quickly as has ours. I might rather suggest that we may be resistant to difference in what we consider to be our essential peda gogy—what and how we teach—because this has shifted very little even as our canon and methods have explosively grown in breadth and complexity. Our pedagogy is inextricably intertwined with our originary canon and method; they define and circumscribe each other. As such, that which is not spawned from the narrow lineage doesn’t fit in; it is instead part of the large, messy, and murky “other” that threatens to upend that which we know and that which we make.

We do not want to cast off our long history and start anew, but we also need to radically rethink our pedagogy moving forward so that we design for the world that is and could be, and not for an idealized version of the past. The essays in this volume of Platform are a snapshot into how our school has been wrestling with pushing beyond our former boundaries and into territory with unending possibility, while also making sure that we don’t lose our footing. Never before have we faced such extraordinary opportunities.

TOP Teaching Spaces

Tribute: Battle Hall exterior ornamentation. Photo by Nathan Sheppard.

BOTTOM Teaching Spaces

Sutton Hall exterior ornamentation, 2012.

TOP Teaching Spaces

Tribute: Battle Hall exterior ornamentation. Photo by Nathan Sheppard.

BOTTOM Teaching Spaces

Sutton Hall exterior ornamentation, 2012.

4 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

ELIZABETH DANZE

HOPE HASBROUCK

SAMIRA BINTE BASHAR

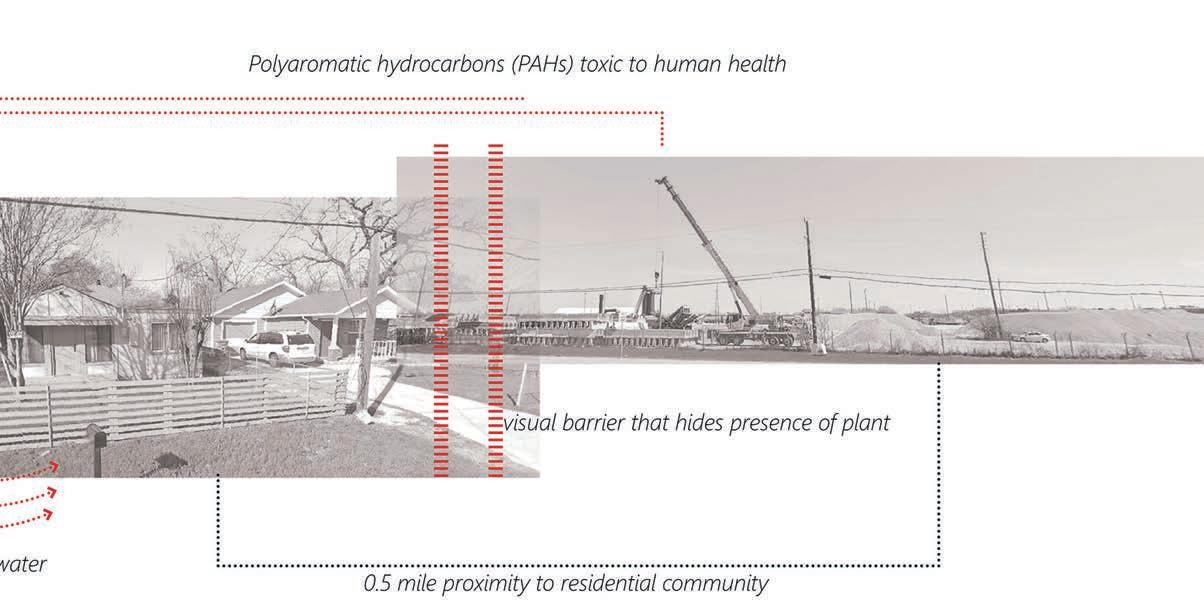

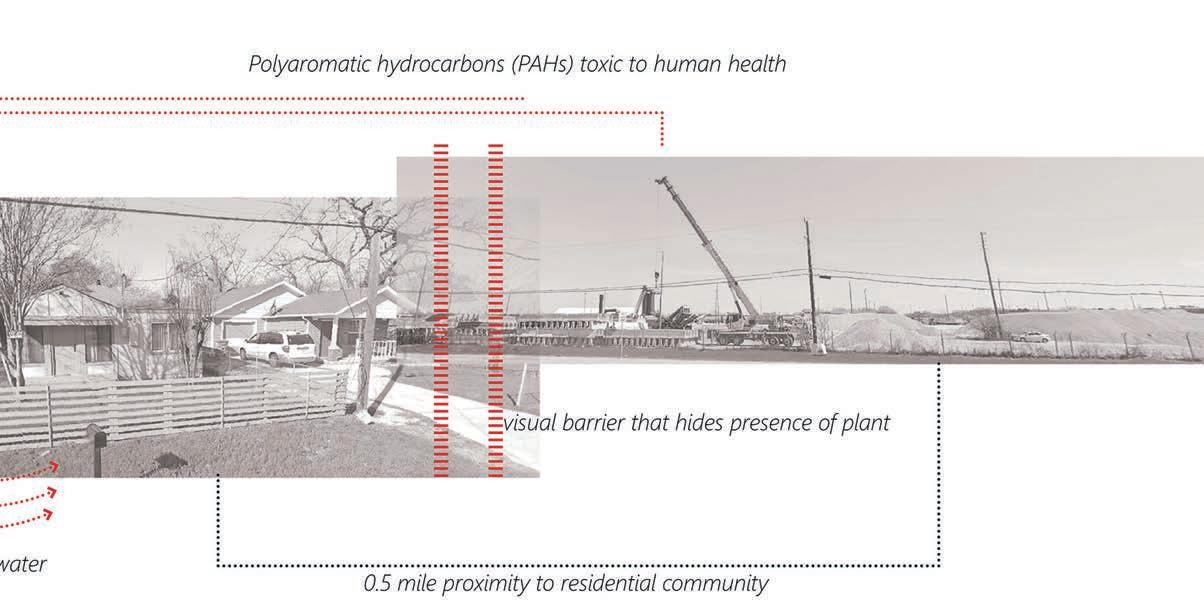

TARA A. DUDLEY

DANIEL KOEHLER

RICHARD CLEARY

PATRICIA A. WILSON

NICHOLE WIEDEMANN

FRANCISCO GOMES

MAGGIE HANSEN

RAKSHA VASUDEVAN

ROBERT STEPNOSKI

LEÓN STAINES

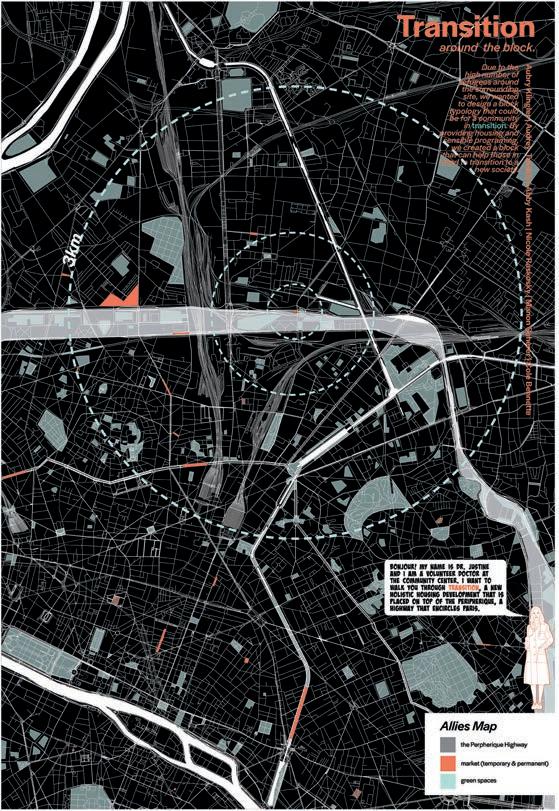

BJØRN SLETTO

IGOR SIDDIQUI

ALEXANDRA LAMIÑA

CONTRIBUTORS

SAMIRA BINTE BASHAR is a doctoral student in the Community and Regional Planning Program in the School of Architecture, where she also received her master’s degree in planning. Her research interest lies at the intersection of waterscape development, environmental justice, and informal urbanism in Bangladesh. Samira is particularly interested in advancing spatial justice and equity through planning by working with marginalized communities who have been traditionally excluded from the planning process. Her previous work focused on reevaluating the planning paradigms of Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar and the preservation of the settlement of a fisher community in her hometown of Chattogram, Bangladesh. Samira has more than two years of teaching experience in Bangladesh, where she led design studios focused on activity-space relationships, urban design, and housing and courses on the history and theory of architecture and design.

RICHARD CLEARY, PhD, is a professor emeritus in the School of Architecture who taught architectural history and theory from 1995 to 2019. He is a recipient of The University of Texas System Regents’ Outstanding Teaching Award. Prior to his appointment at the school, he taught at Carnegie Mellon University. He now resides in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and is an honorary fellow in the Department of Art History and a community associate in the Center for Culture, History, and Environment at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His current research addresses spatial practices in sports and topics on the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. His most recent publication is “Fields of Play as Laboratories of Spatial Invention,” a chapter in Landscapes of Sport: Histories of Physical Exercise, Sport, and Health, edited by Sonja Dümpelmann (Dumbarton Oaks, 2022).

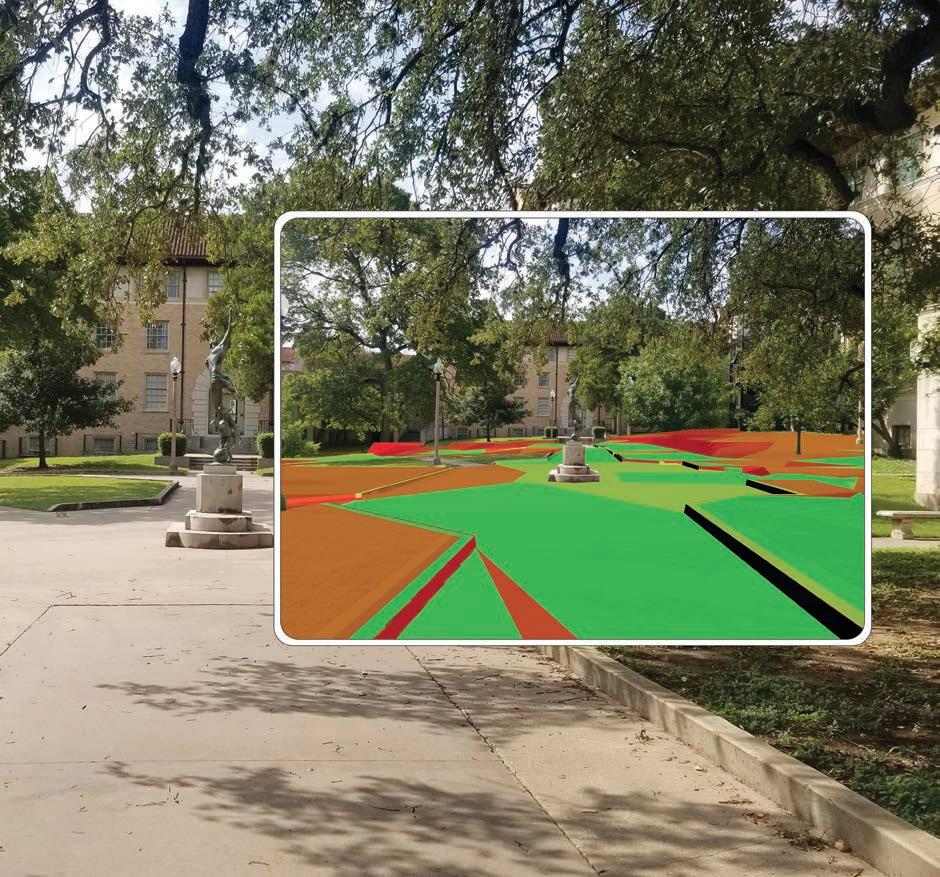

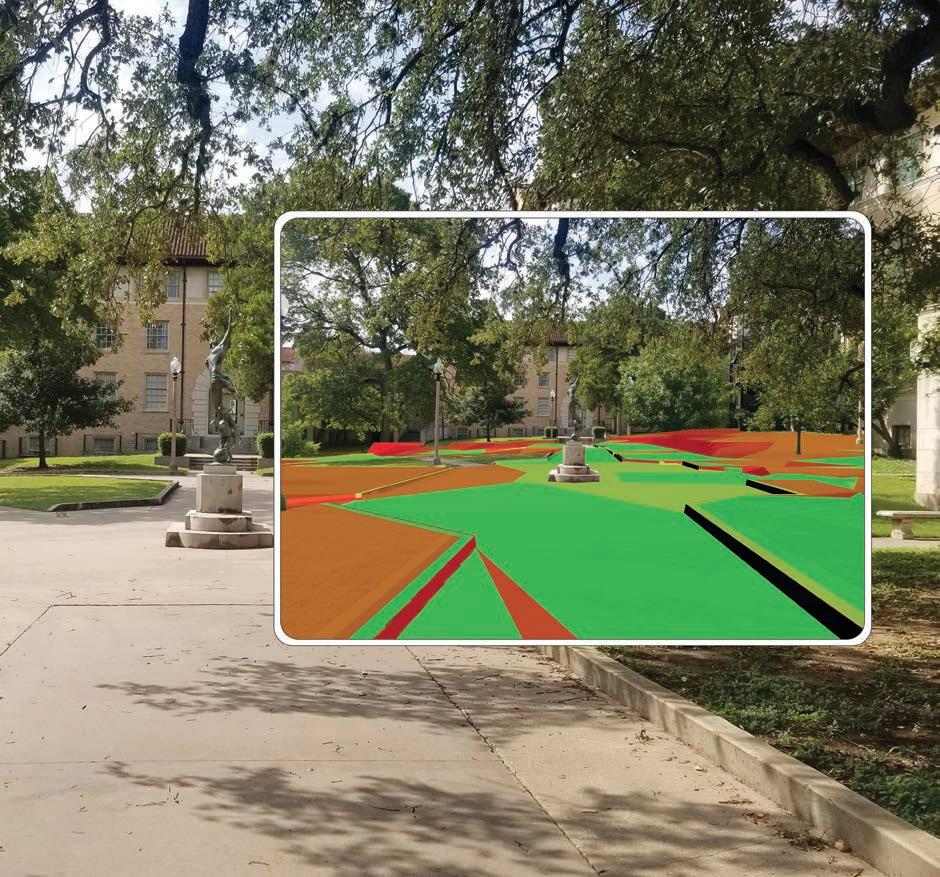

ELIZABETH DANZE , FAIA, is a professor in the School of Architecture, where she holds the Bartlett Cocke Regents Professorship in Architecture. She earned a BArch from The University of Texas at Austin, and MArch from Yale University. A principal with Danze Blood Architects, her work integrates practice and theory across disciplines by examining the convergence of sociology and psychology with the tangibles of space and construction. At the School of Architecture, Danze has served as Interim Dean, Associate Dean for Graduate Programs, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs. She is co-editor and author of Psychoanalysis and Architecture; The Annual of Psychoanalysis, Volume 33; and CENTER 17: Space and Psyche. She is the architect advisor to the American Psychoanalytic Association’s Committee on Psychoanalysis and the Academy. Danze is the recipient of The University of Texas System Regents’ Outstanding Teaching Award and the Texas Society of Architects Edward J. Romieniec Award for Outstanding Educational Contributions, is a member of The University of Texas Academy of Distinguished Teachers, and a Distinguished Professor of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture.

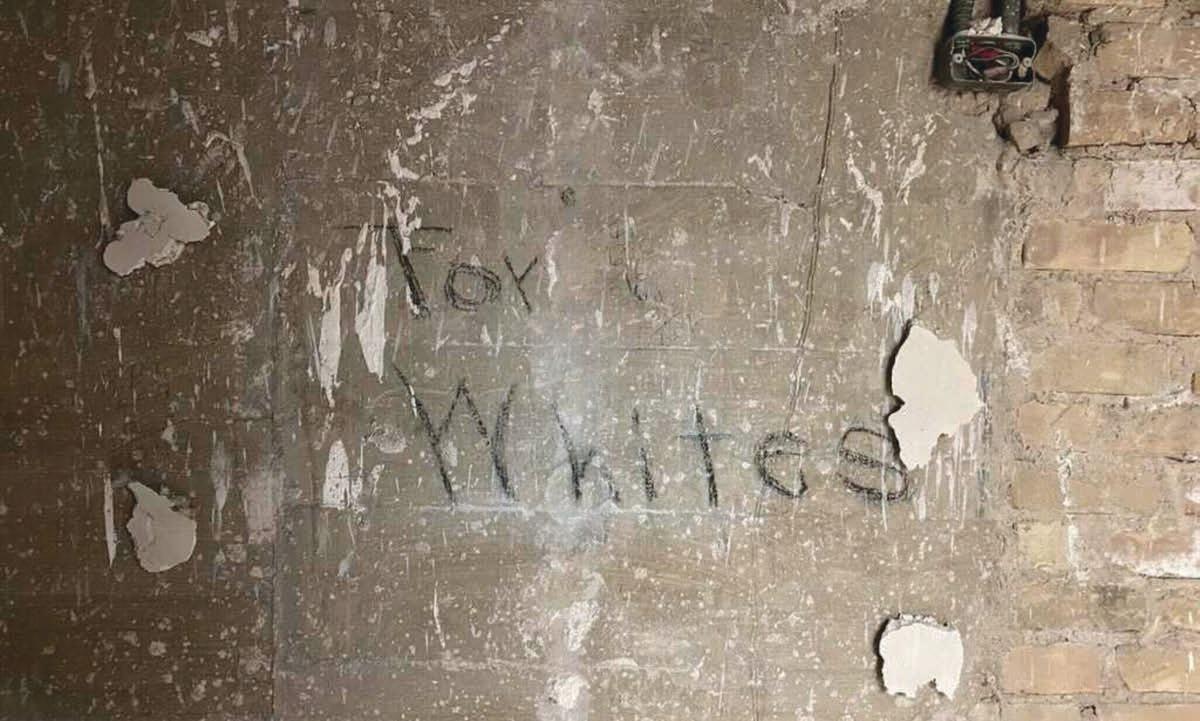

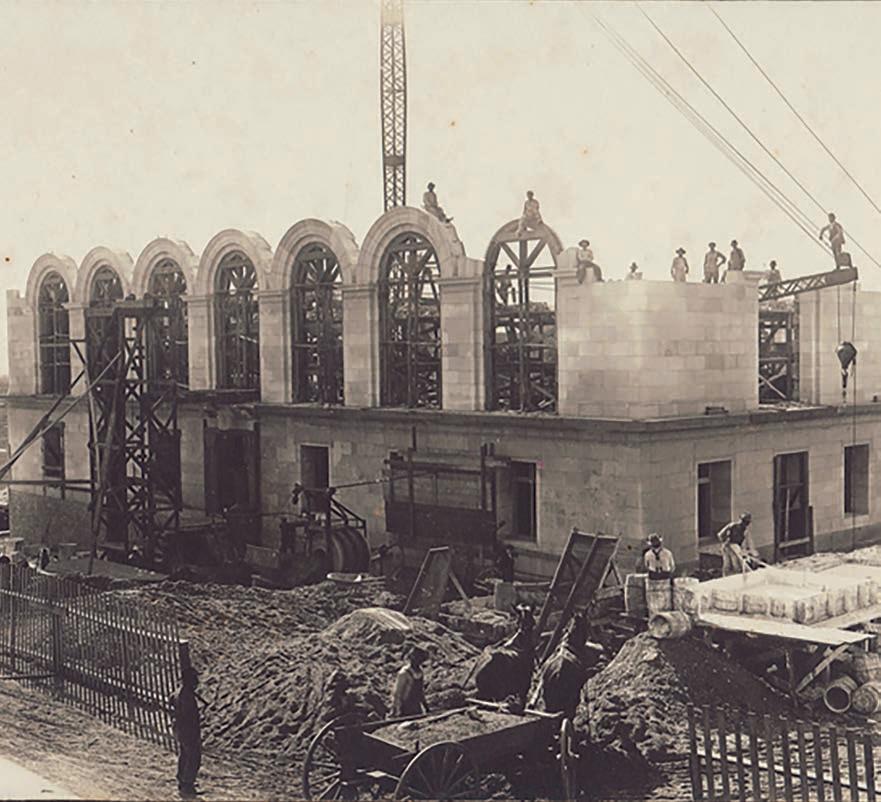

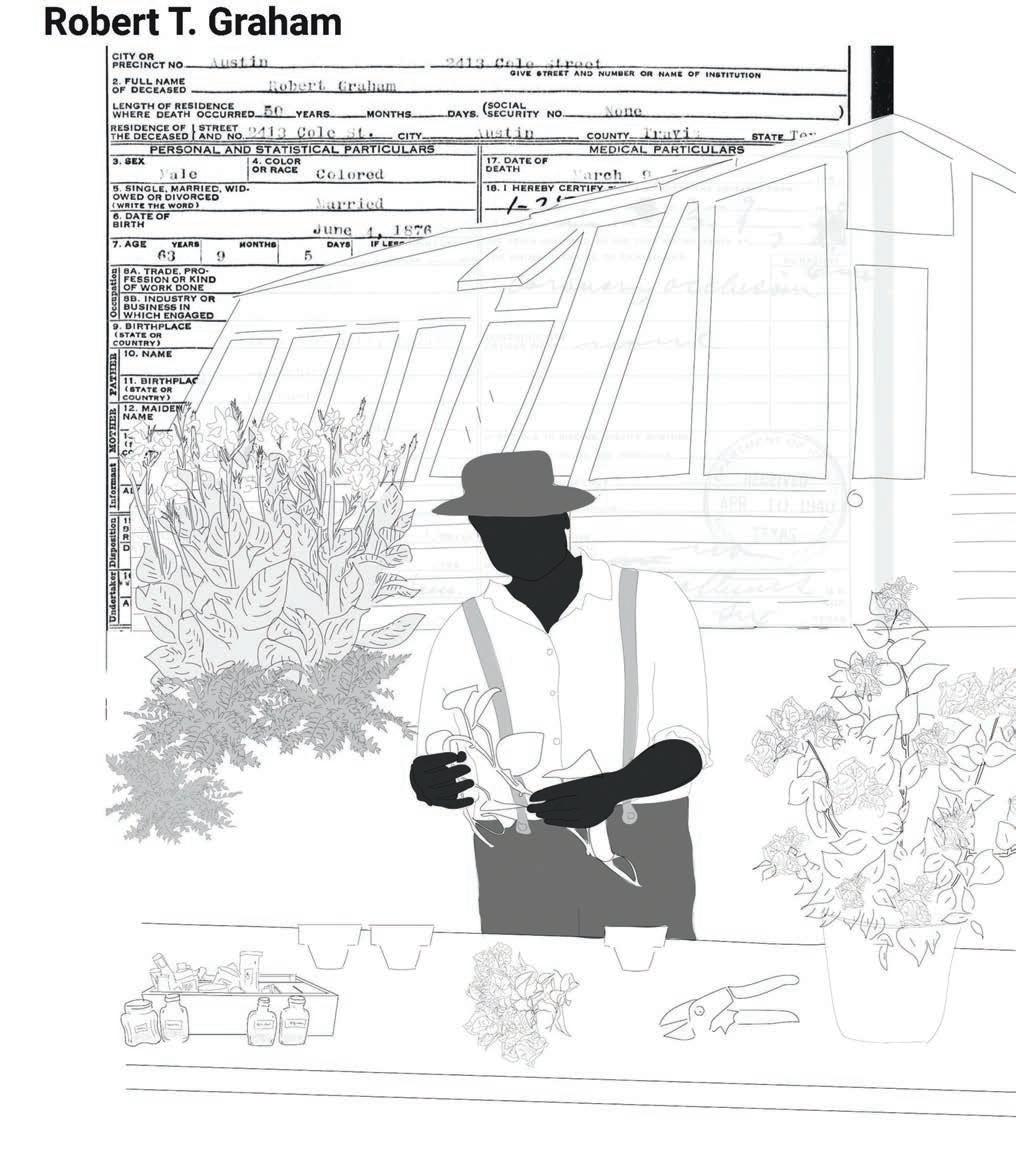

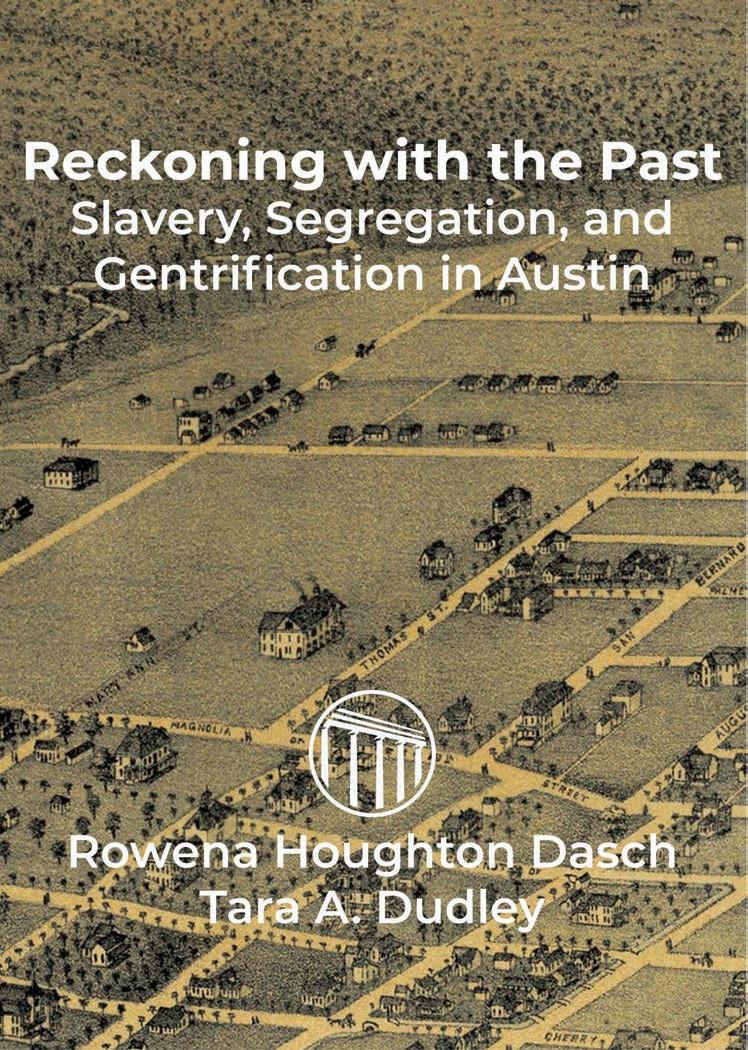

TARA A. DUDLEY, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Architecture. She uses an interdisciplinary approach to study cultural resources with a focus on nineteenth-century American design, African American architectural history, historic preservation, and material culture. Current research projects illuminate the contributions of African American builders and architects with a focus on the antebellum and Reconstruction eras in the South, including Texas. As a member of the UT Austin Contextualization and Commemoration Initiative research team, Dr. Dudley has turned her focus to revealing Black Austinites’ contributions to UT

Austin’s campus development. Her research methodology includes creative utilization of archival resources and normalization of nontraditional academic practices to intersect academia and public access and to encourage preservation as a tool for social justice in her work on preservation-related projects across the country. Dr. Dudley authored Building Antebellum New Orleans: Free People of Color and Their Influence (UT Press, 2021), winner of the Association of American Publishers 2022 Prose Award in Architecture & Urban Planning and the 2022 Summerlee Book Prize in Nonfiction. She obtained her doctorate in Architectural History and master’s degree in Historic Preservation from UT Austin and holds a bachelor’s degree in Art History from Princeton University.

FRANCISCO GOMES has taught at the School of Architecture since 2008, where he has also served as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and held the Meadows Foundation Centennial Fellowship. He is an architect, the son of Danish and Portuguese immigrants, and is extraordinarily lucky to be the husband of Dabney, with whom he is raising two kids. In addition to the design implications of construction materials and techniques, his interests include the history of radiology and surfski racing.

MAGGIE HANSEN is an assistant professor of landscape architecture in the School of Architecture, where she teaches core and advanced studios, visual communication, introductory design, and theory electives. Her research and teaching draw on her training in architecture, landscape architecture, theater, and contemporary art; experience working in community-based design in New Orleans; and experience contributing to the design of significant public spaces such as Olana State Historic Site, the Naval Cemetery Landscape memorial in Brooklyn, and Hudson Yards East. Her current research explores ongoing

5

practices of care and repair as design methods of shaping space and strengthening relationships between people and place. She is the 2021–2023 Meadows Foundation Centennial Fellow of the Center for American Architecture and Design and a designer with FORGE Landscape Architecture.

HOPE HASBROUCK is Director of the Graduate Program in Landscape Architecture at the School of Architecture, the David Bruton, Jr., Centennial Professorship in Urban Design fellow, and a fellow of the American Academy in Rome. Hasbrouck’s scholarly activities revolve around applied digital technologies in landscape architecture. Hope practiced professionally before twenty-five years of teaching at Harvard University and The University of Texas.

DANIEL KOEHLER is an assistant professor for architecture computation in the School of Architecture. He is an architect, urbanist, researcher, and co-founder of lab-eds. Previously, Daniel researched at The Bartlett in London and the University of Innsbruck, where he completed his PhD. He has taught at several institutions, among them Aalto University in Espoo, Finland; Vilnius Academy of Arts in Lithuania; and the University of East London. His work has been exhibited in Austin, Prague, Milan, Venice, Graz, Montreal, and London, and is part of the permanent collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. He is the author of The Mereological City, a study on the part-relationships between architecture and its city in the modern period. His current research focuses on the urban implications of distributive technologies, which are being designed by means of sets, data, interfaces, and their architecture.

ALEXANDRA LAMIÑA is an Ecuadorian doctoral candidate in Latin American Studies at The University of Texas at Austin, where she also earned a dual master’s degree in community and regional planning and Latin American studies. Her background is in geography, and her previous work focused on Indigenous geographies and regional planning in Ecuadorian Amazonia. Her collaborations with the Kichwa Nation in Amazonia have inspired her work to support Indigenous territoriality and political representation since 2010. Her current research examines how Indigenous people in Ecuadorian Amazonia transform colonial urbanization through Indigenous knowledge production, mobilities, and Indigenous planning. Alexandra primarily focuses on the Amazonian urban geographies, learning from Indigenous epistemological traditions and drawing on feminist, Indigenous, and decolonial thinking in geography and urban planning.

IGOR SIDDIQUI is an associate professor at the School of Architecture, where he currently serves as Program Director for Interior Design and is the Gene Edward Mikeska Endowed Chair. His work has been exhibited at the Tallinn Architecture Biennale, The Contemporary Austin, SITE Santa Fe, SXSW Eco, Fusebox Festival, Metro Show Art Fair, the Ogden Museum of Art, and Flux Factory, and has appeared in professional and popular publications such as Dwell, Interior Design, The Architect’s Newspaper, Artforum, Texas Architect, and SmART Magazine. Siddiqui’s academic writing includes contributions to the books Digital Fabrication in Interior Design, Appropriate(d) Interiors, Textile Technology and Design: From Interior Space to Outer Space, and The Handbook of Interior Architecture and Design, and has appeared in

peer-reviewed journals including Interiors: Design/Architecture/Culture, Interiority, IDEA Journal , and International Journal of Interior Architecture and Spatial Design After five years of service as Associate Editor for Interiors: Design/Architecture/ Culture, Siddiqui was recently appointed as the journal’s Co-Editor-in-Chief. Prior to establishing his own practice in 2006, Siddiqui worked with Kohn Pedersen Fox and 1100 Architect in New York City. He studied architecture at Yale and Tulane and is a registered architect in New York and Texas.

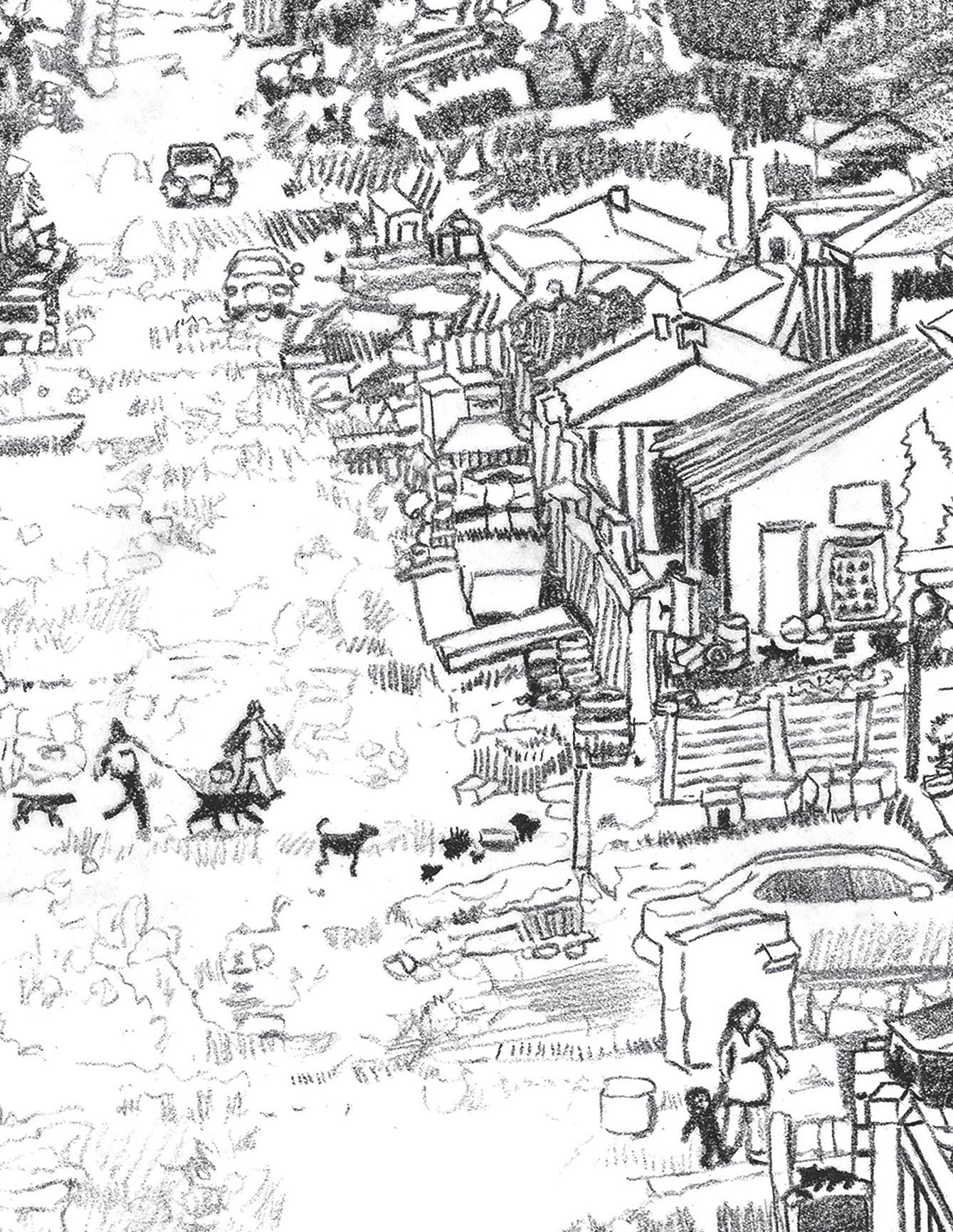

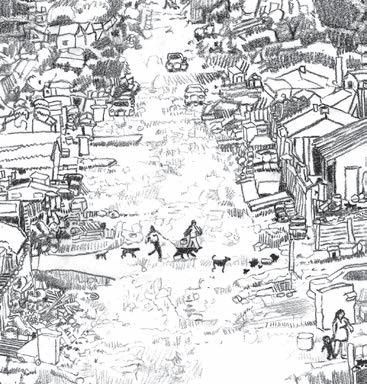

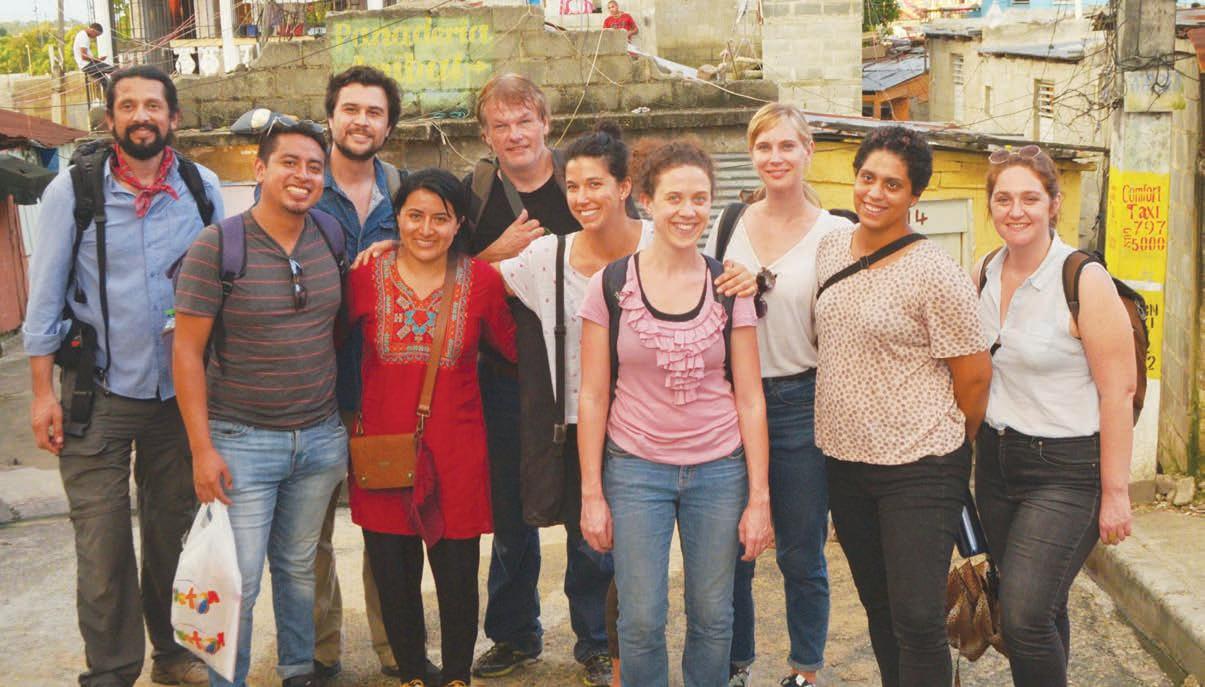

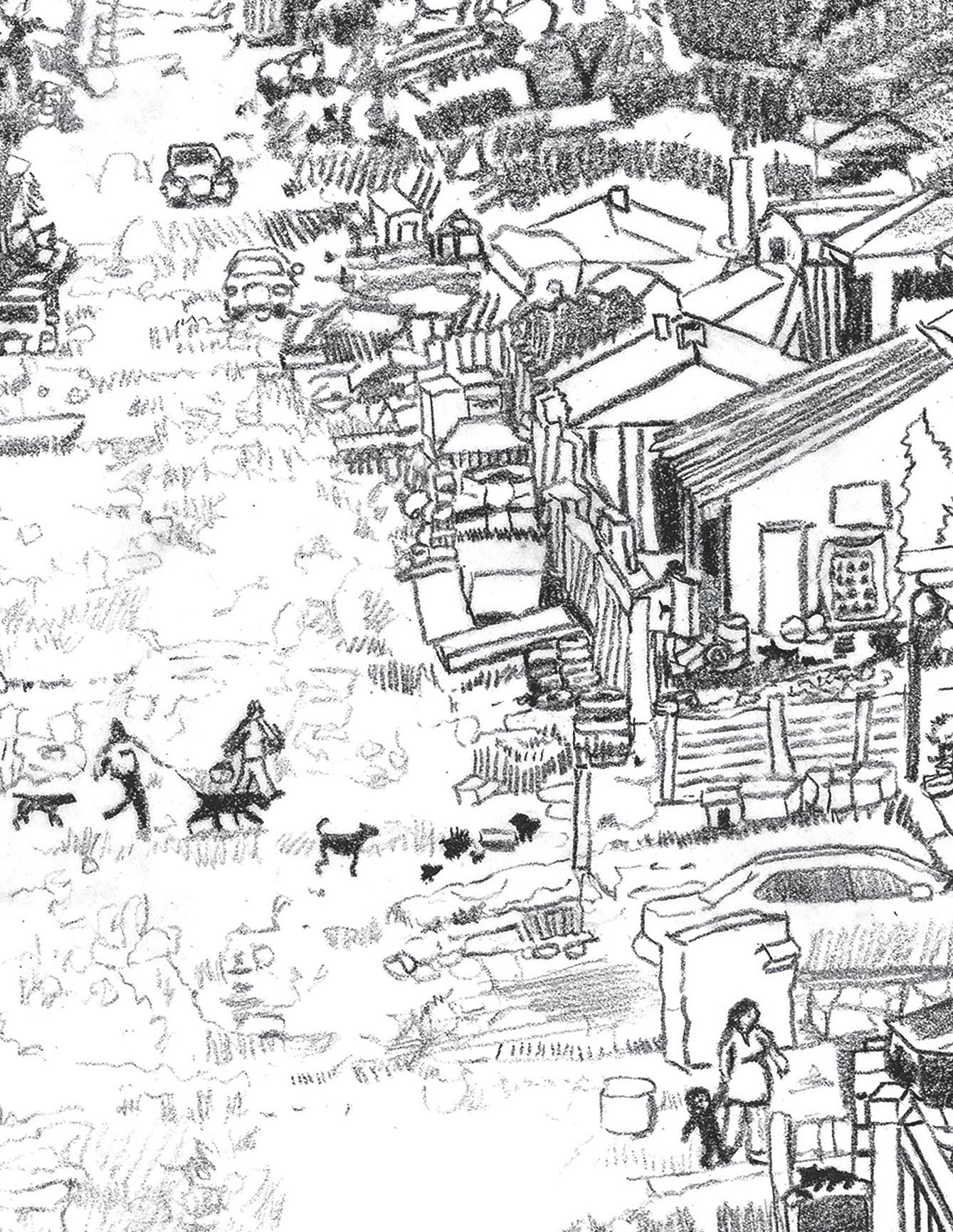

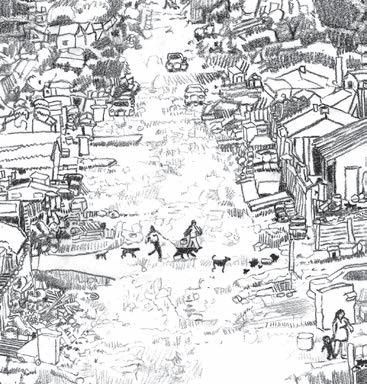

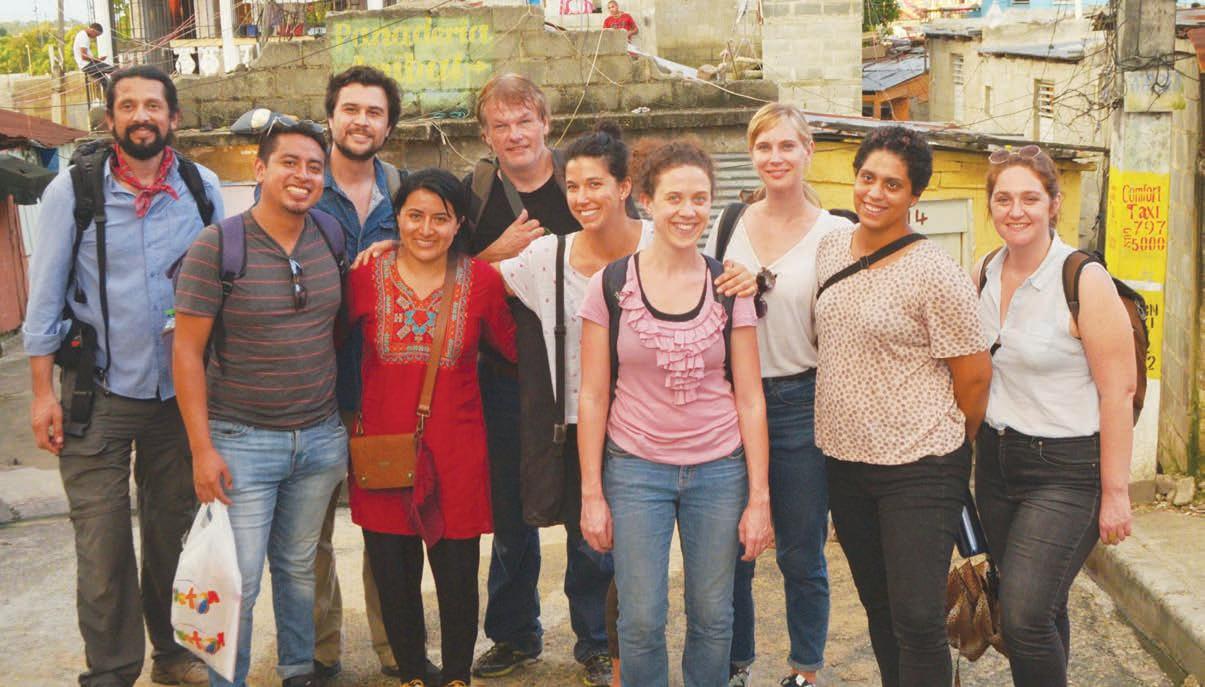

BJØRN SLETTO, PhD, is the graduate adviser for the Community and Regional Planning Program in the School of Architecture. He is an affiliated faculty member in the university’s Department of Geography and the Environment, the Institute of Latin American Studies, and the Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice. Sletto’s research focuses on environmental and social justice, informality, and insurgent and decolonial planning. His work engages with intersections of race, gender, class, and other markers of difference, drawing on ethnographic and arts-based approaches in order to foster transformative research, pedagogy, and plan-making in marginalized communities. He has lived and worked in Indigenous villages and border cities in Venezuela, investigating environmental conflicts and land rights struggles and conducting participatory mapping projects with the Pemon in the Gran Sabana and Yukpa in the Sierra de Perijá. For the past fifteen years, he has conducted activist research accompanied by his students in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, focusing on the role of critical pedagogy for insurgent planning in informal settlements.

6 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

LEÓN STAINES earned his PhD in the Community and Regional Planning Program in the School of Architecture. Originally from Monterrey, Mexico, he received a bachelor’s degree in architecture and a master’s degree in urban affairs from the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, where he has taught urban and architecture studios since 2012. He has also worked at the Monterrey Planning Department and conducted research on spatial justice in low-income communities in Monterrey, focusing on incorporating local knowledge into participatory planning processes. He has earned recognition for his architecture and urban design work in Mexico, and held a doctoral scholarship from CONACYT and ConTex.

ROBERT STEPNOSKI is a senior lecturer and remote pilot at the School of Architecture, where he has taught and researched at the intersection of architecture and digital technologies since 2009. Years of experience as an information technology director in the architectural field and a background in architecture ground his work, including the development and management of shared digital resources such as the GIS Enterprise System, Virtual Lab GPU GRID System, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV, a.k.a. drone) fleet, site scanning devices, large format plotting systems, the Render Farm, and the XR Lab—which, as part of the school’s Virtual Reality Initiative, opened new opportunities for all studios and courses to integrate virtual or augmented reality components into their curricula. As Remote Pilot, Rob collaborates with UT Environmental Health and Safety to maintain and evolve policies and ensure FAA compliance on all on- and off-campus UAV flight requests, while maintaining a FAA Part 107 Remote Pilot License. His current

research focuses on site scanning and point cloud technologies for historic preservation, the use of UAVs for mapping and modeling paired with information technologies for analysis and site discovery, the use of reality capture technologies for architecture, and 3D modeling in architecture.

RAKSHA VASUDEVAN received her PhD in Community and Regional Planning from the School of Architecture, and is currently a Dr. Bruce S. Goldberg Postdoctoral Fellow in Youth Wellbeing at the Center for Sustainable Futures, Teachers College, Columbia University. Her work focuses on the impacts of planning and education institutions on young people’s well-being and their possibilities for the future. Specifically, she is interested in how young people understand and negotiate socio-environmental uncertainties in their daily lives. Raksha’s work is inspired by intersectional and decolonial feminist scholars to envision alternative, more ethical modes of critical urban research and practice. Given that young people have intimate and embodied expertise about the neighborhoods in which they live, she combines feminist ethnography with mapping, oral histories, and arts-based methods to co-produce knowledge with young people and their families. Raksha’s prior work experiences are varied and include working as an intern architect and teaching small children in an arts-based school. She also managed the sustainability program at the National League of Cities, where she worked with sustainability directors and local elected officials to progress city sustainability efforts in the United States.

NICHOLE WIEDEMANN , AIA, is an associate professor and the director of the Professional Residency Program in the School of Architecture, where she also served as

Associate Dean for Undergraduate Programs from 2008 to 2013. She teaches design studios, drawing courses, theory seminars and study abroad programs. A registered architect, Wiedemann maintains a small independent practice with recent projects in Texas and Colorado. Her work, independent and collaborative, has been exhibited nationally and internationally and has been featured in the Journal of Architectural Education, On Site, Progressive Architecture, and other publications.

PATRICIA A. WILSON is a senior professor in the Community and Regional Planning Program in the School of Architecture. Her interests evolved over the decades from regional economic development and inequality to community engagement and the phenomenology of inclusive practice. Her recent courses include the Art of Community Engagement, International Participatory Action Research, and Participatory Democracy. Her field research in community-based change processes has included Latin America, South Africa, India, and the United States. A past president of the Sociedad Interamericana de Planificación, she led a seven-year action research program on informality in urban and peri-urban Mexico. Dr. Wilson earned a BA with honors in economics from Stanford, and her master’s and PhD in regional planning from Cornell. She is author or co-author of seven books and numerous journal articles. Her latest book, The Art of Community Engagement: Practitioner Stories from Across the Globe (Routledge, 2019), won the 2020 Hamilton Book Award for best textbook. Dr. Wilson currently serves on the editorial board of the new Journal of Awareness-Based Systems Change and as an adviser to the World Health Organization on its “whole person-whole system” community engagement protocols.

7

TEACHING EDITOR’S INTRO

FOR NEXT ELIZABETH DANZE

As a first-year student entering Goldsmith Hall in 1976, I had—as I thought at the time—clear ideas about what I might do with an architectural education. What I didn’t yet appreciate was that the School of Architecture was, and continues to be, abundantly more than a place to develop special skills and training. It is a rich ecosystem of diverse ideas, a community brought together in a distinct place where we collectively look broadly, deeply, and consequentially at the dynamic world we inhabit together. Looking back, I appreciate the unique and profound role that learning in our academic environment has provided thou sands of students like me. Looking forward as a teacher, I am regularly asking myself what is next? How are we to teach in ways that best prepare our students for a demanding, chal lenging, and ever-shifting world?

This issue of Platform features teaching at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture and explores how we set students up for success in a world that is different than we might have imagined even only a few years ago. The essays and interviews within include considerations of how faculty and students work together to create an atmosphere in which the study of our disciplines cuts across profes sional areas of expertise, expands perspectives, contributes to essential discourse about the built environment, and responds with dexterity and intelligence to changing contexts.

The following pages examine our teaching through several lenses: the range of methods, the hoped-for impacts, and their relevance for

LEFT Teaching Spaces

an unpredictable future. This issue’s contrib utors draw upon their individual pedagogical approaches and influences, including recent scholarship, teaching, and research methods; use of technology; reconsiderations of history, social, and cultural impacts; as well as critical practice. Their insights reveal the myriad ways we teach and think about teaching, and begin to answer key questions: What are the endur ing pedagogical approaches to teaching at the school? How has our teaching changed in the recent past? How have innovations in technolo gy affected what and how we teach now and in the future? How do ideas developed in school become evident in our profession? And, how does the school move the discipline forward?

Interviews in this issue include two cohorts of professors that began teaching together— one in 1975 and the other in 1991. Professor Emeritus Richard Cleary engaged both groups with questions centered around their role as educators then, now, and moving into the fu ture. Our alum interview highlights the work and teaching of University of Virginia profes sor and The Texas Freedom Colonies Project founder Andrea Roberts.

Essays in this issue include reflections by Cisco Gomes, Nichole Wiedemann, and Igor Siddiqui on programs that uniquely support the school’s teaching goals: the relatively new fellowship positions for emerging scholars and design thinkers, the almost fifty-year-old Professional Residency Program, and the even longer traditions and evolving programs for study abroad. Our own Battle Hall is the subject of Tara Dudley’s essay, which considers the building’s racialized past and approaches to researching, teaching, and preserving that difficult history. Maggie Hansen, using a case study from her design studio, writes of the overlap of policy and design. Looking at civic engagement and collaboration and drawing

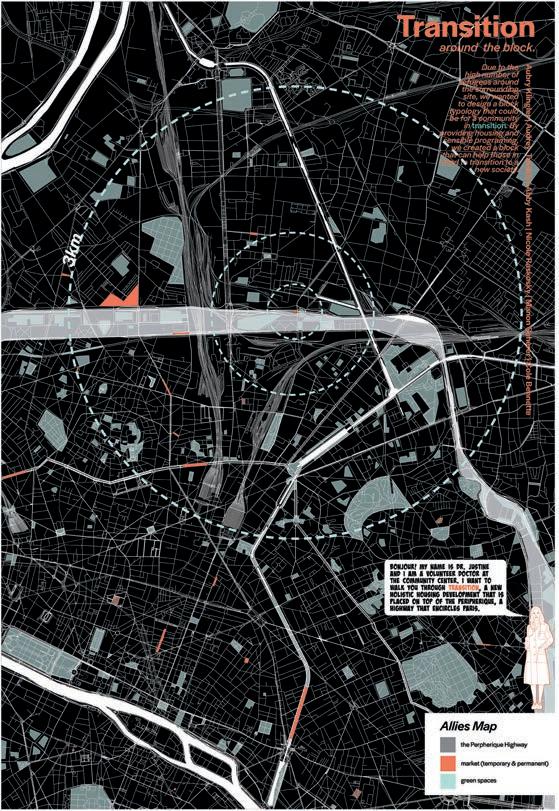

from her recent book, Patricia Wilson explores a particular pedagogical stance that includes working with communities across the globe; likewise, Bjørn Sletto and his students discuss stakeholder mapping and how mapping and epistemology can help address marginalization and social-environmental insecurity. The issue closes with considerations of new technologies, with Hope Hasbrouck and Robert Stepnoski exploring their use of digital immersive en vironments, and Daniel Koehler exploring artificial intelligence in the context of teaching in design studios.

Together these contributions reveal the deeply humanistic ways in which we work and teach. Whether engaging through human-to-human interactions, methods like archival research or drawing, or interactions dependent on machines, we do so with the goal of creating a better world for one another.

If we trace the words professional and professor back to their origins, we find that they refer to someone who makes a “public declaration” or a “profession of faith” in the midst of a disheart ening world.1 Today this root meaning has all but disappeared, but this issue of Platform makes it clear that we are teaching to this definition—and with passion. At the School of Architecture, we exemplify the complexity of what it means to work and live together and that “our great calling, opportunity, and power as educators is to shed light in [sometimes] dark places”2 so that together we support the positive potential and effects of the natural and built environment. As teachers, we work together and with our students to understand the world at large so that we might collectively design and steward the future—for what’s next.

1. Parker J. Palmer, The Courage to Teach (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017), 212.

2. Palmer, 213.

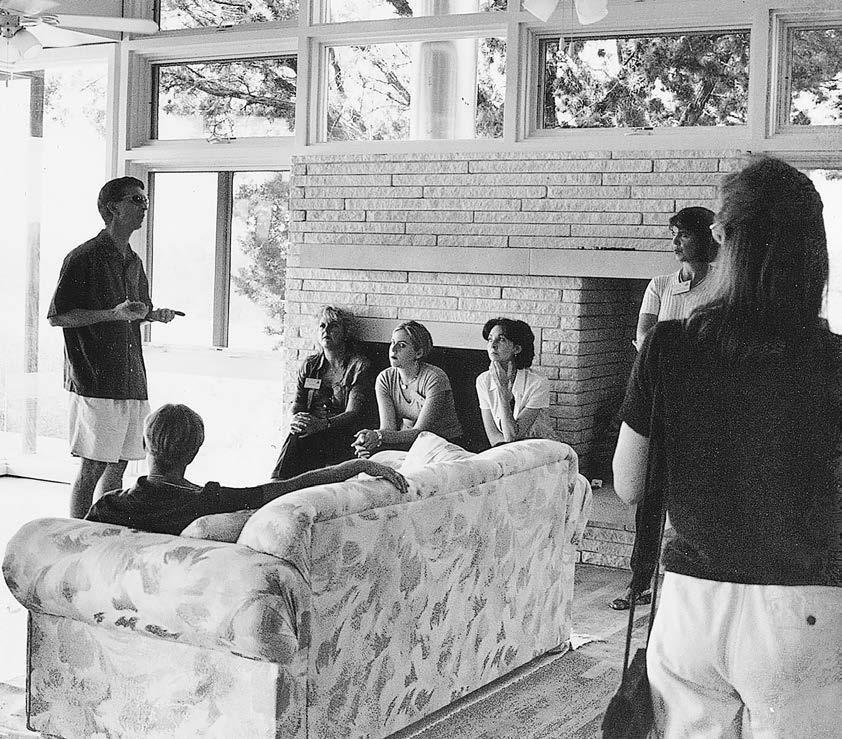

Tribute: Review in West Mall Building, 2019. Photo by Casey Dunn.

9

REFLECTIONS ON

10 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

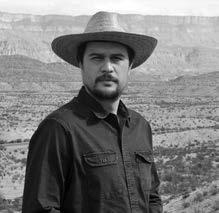

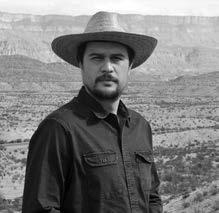

RIGHT L arry Speck, 2018. Photo by Sloan Breeden.

TEACHING

47 YEARS AND COUNTING

RICHARD CLEARY

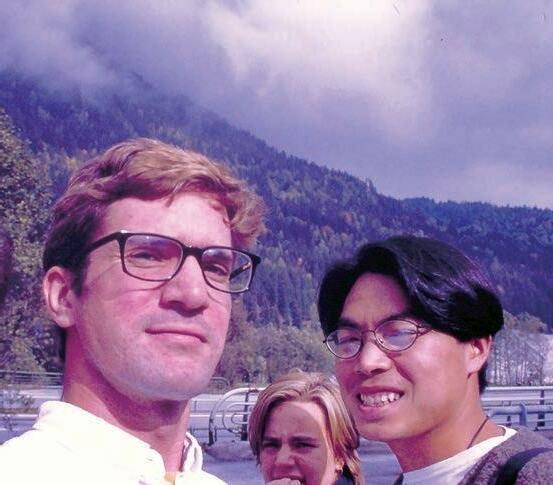

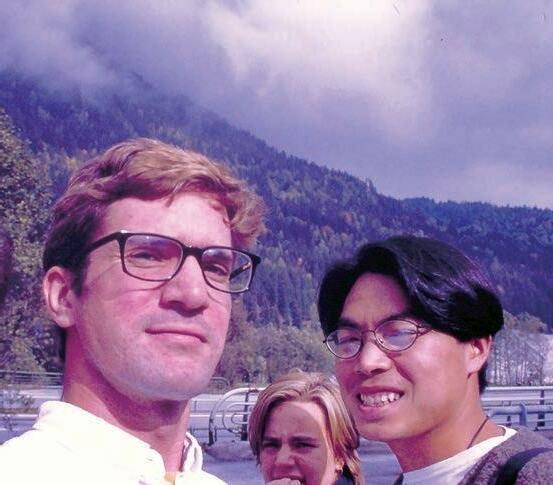

Michael Benedikt, who started his career in architecture in South Africa and went on to Yale for post-professional study; Michael Garrison, with degrees in architecture from LSU and Rice; and Larry Speck, with degrees in architecture and management from MIT, all joined the faculty of the School of Architecture in 1975. Forty-seven years later, they spoke with Professor Emeritus Richard Cleary about their experiences as teachers. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

RICHARD CLEARY What did you understand your role to be when you faced your first classes? What were you prepared for?

MICHAEL BENEDIKT I can honestly say that when I first came, I did not think of my mission very much in terms of Let’s make UT great, if that makes sense. I felt very grateful to be at an institution that would have me at all, quite frankly, and was very appreciative of Chuck [Charles] Burnette’s [Dean, 1973–75] confidence in me, meeting Michael and Larry, and feeling like we were a cohort. It took me a little while to think, Wait a minute, I have to build the school. My early years were mostly about what I thought my contribution could be to the profession, to theory, to what architecture was, and how we should think about it. I think I ended at what back then we called environment behavior. I really thought we didn’t understand what buildings were doing to people and what people were doing to buildings, and I was caught up in

the phenomenology of being in space and in different kinds of buildings and thinking we didn’t have a theoretical language, except just to wave vaguely at what space was pleasant or inspiring or oppressive. I thought a much finer set of questions could be asked. That’s where I started. I wanted to build my own career— I had a family; I had to make sure I got tenure and all—and it was only later that I felt some kind of co-ownership of the school as a ship, so to speak, as an institution.

RC Michael Garrison, what did you think you were about? Were you a rebel?

MICHAEL GARRISON Yeah, when I first came, I was a licensed architect and had worked after grad school for an architect, John Starnes, who was in Lou Kahn’s office when they did the Kimbell, and so I was really interested in conversations about building integration. It was just after the first so-called energy crisis, and there was a sense in the air that we needed to do something about it in terms of buildings. I worked on a project for a physics professor, John Wheeler, who had recently come to Texas from Princeton. Through conversations with him, I wrote a paper called “Living on Borrowed Time” that I presented to the UN Conference on Human Settlements, and that really defined the problem for me; it set the blueprint for my work for the last almost fifty years.

RC Larry, you followed the path of many Texas architects, by going to MIT for professional education. You came back to Texas. What did you think you were doing here?

LARRY SPECK I was extremely focused on the students. I thought, initially, my role was to be a teacher, and I needed to be really plugged into the students, but oh my, I was teaching two studios every semester, an incredibly heavy teaching load if you took it seriously, so I was just trying to meet the challenges of teaching. I’d had a much more luxurious situation teaching at MIT. At the same time, I was very focused on making buildings. I wanted to be an architect. In both my teaching and my practice, which I started immediately, I was very focused on how you make buildings. Not the idea of a building, but a building. I have very, very fond memories of working with those students in that era. They were not that much younger than we were, and there was an incredibly warm relationship between faculty and students. I was teaching in the basement of Sutton. The physical facilities and the resources were meager, and so my challenge, I thought, was: how can we deliver a really good education to these people—these delightful, bright, really ambitious young minds—with very, very little resources?

RC Can each of you think of a particular challenge or pivotal moment that inspired you to shift your pedagogical approach?

11

LS I’ll lead off on this one. There definitely was a pivotal moment for me. I’d been here for four years, and I got a Fulbright grant to be in Australia for a year. I’d had enough of being in a groove and a set of expectations, and I said, Where do I want to go, what do I want to do? In a completely different context, with a completely different set of colleagues, I went to five different universities in Australia and met amazing people—Glenn Murcutt was one of them—and there was a lively conversation about architecture going on there. But the pivotal thing was I began to realize that what had made the big difference in my education and thinking about design was courses that had more to do with reading and writing and critical thinking about architecture, than my studios where I’d been concentrating on “Do Do Do Do” production. So, when I came back, I did what the students called the “un-studio.” I did not go to the studio space, ever. I told them at the beginning, I’m never going to sit by your desk and do a crit, but we’re going to have discussions in a room; we’re going to read books, we’re going to talk about ideas, we’re going to look at buildings and images and the ways other architects translated ideas into buildings. I taught that un-studio for four or five years and eventually transitioned into teaching Architecture and Society to talk about ideas in architecture not just to an architectural audience, but other people as well, and Theory I, which I’ve taught since then. It was a complete transformation of how I saw my role as an architectural educator.

RC Michael?

MB Let’s go counter-clockwise.

LS Chicken.

RC That brings us to you, Michael G.

MG When I first started teaching, we didn’t have a graduate program. We started the graduate program I think about ’78, ’79. They had a background in architecture, so when I had these students, it was like, okay, what’s next? What’s the next level up? It was about that time when Hal Box [Dean, 1976–92]

said, I want our buildings to be sounder —I think “sound” was the word he used.

RC The sound building, that’s a Hal Box phrase.

MG Yeah, he told me, I want you to figure out how to make our buildings sounder. The work of the students is just not good enough. I remember going back to the studio thinking about what he had said. I had given a design problem, and the students were, I guess, almost three fourths of the way through it. I walked into the studio and said, I’ve got some good news and some bad news. The good news is you’ve been hired. The bad news is that the client went bankrupt, and you have to remodel the project to a completely different use. Flipping it like that made me rethink the way I was teaching and think a lot more about design and performance being two different ends of the same idea.

RC Sound building was a touchstone phrase when I arrived in ‘95 and continued at least until the early 2000s. Michael Benedikt?

MB I always thought that a conversation with a student, with a pencil in hand, about the opportunities facing us was the most thrilling part. To me, that’s where the rods of the nuclear reactor are, that’s where the heat is, and that’s the moment that needs to be protected from everything else. That’s how I was educated my first few years in an office. I was very close to the principal, and we had those kinds of dialogues with paper flying all over the place. He would get up from my desk, and I’d have to clean up for twenty minutes because he was drawing and talking so fast and

furious. There are little shades of that in me. And you know, when I watched videos of Louis Kahn working, I saw the same pattern. But I have to say, when I think back over the dozens of crazy projects I’ve invented to crack the code, if you will, of what great design is, what wonderful design is, I don’t know that I ever did crack the code. That means to this very day, I have jitters every time I start a studio with a new set of projects with some new idea to see if I can engage the students, to take them on a journey that they have not been on before.

RC How do you see your position as you’re trying to communicate the goals of the course while facing students who maybe are on track or are adrift? This is a time when awareness of faculty-student interactions is very different than when we were starting our teaching careers.

MB I think the quality of the dialogue with our students at a quasi-personal level— I wouldn’t say truly personal—was part of the teacher-student relationship. And I do think in recent years, it’s been much more institutionalized. There’s a proper way now to refer students to counseling services, to report if they’re in any kind of trouble, and it’s much, much more hands off. For me, there’s not a semester when I’m not tempted to try to be helpful in a paternal way—I mean being as old as I am of course—and in a caring way to say something helpful rather than just move them to a counseling situation. I’m not sure if Michael or Larry or any of my colleagues do any different. You can’t help but see the

12 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

I always thought that a conversation with a student, with a pencil in hand, about the opportunities facing us was the most thrilling part.

13

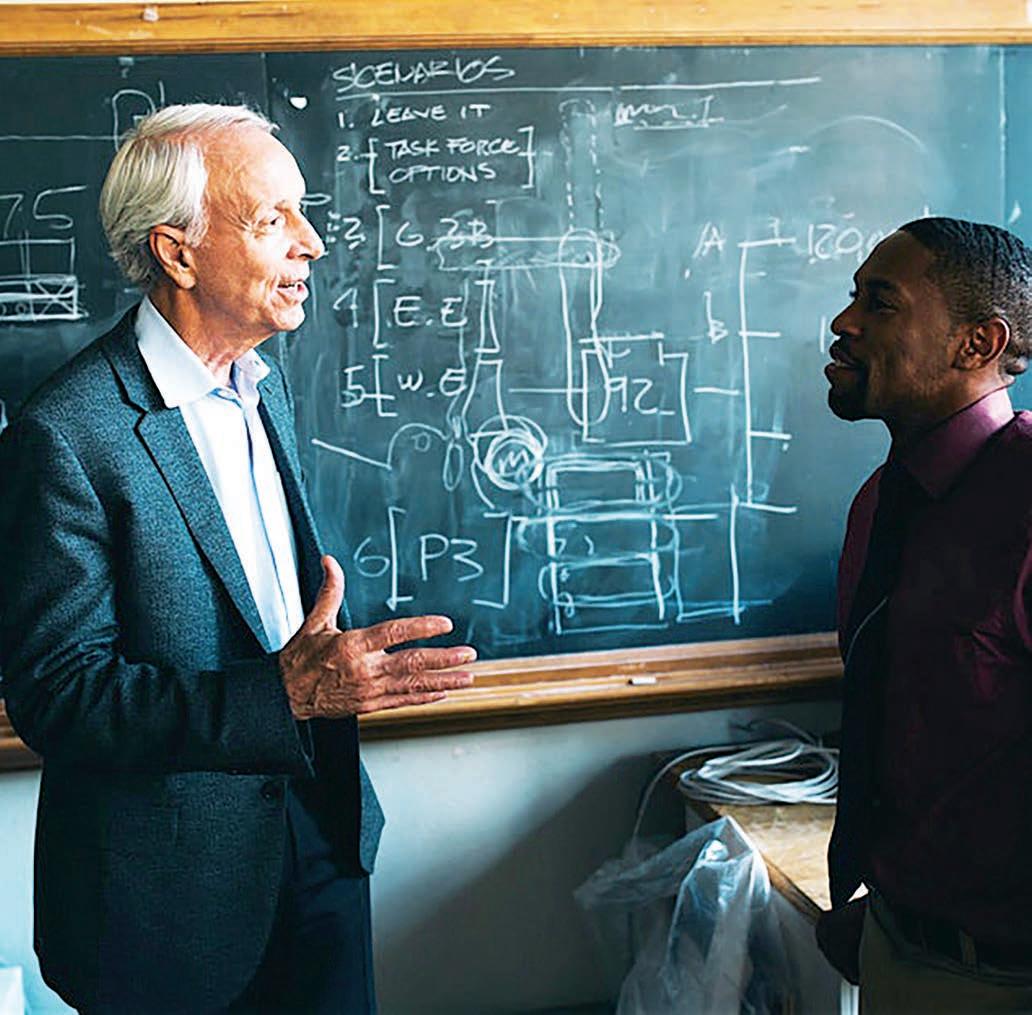

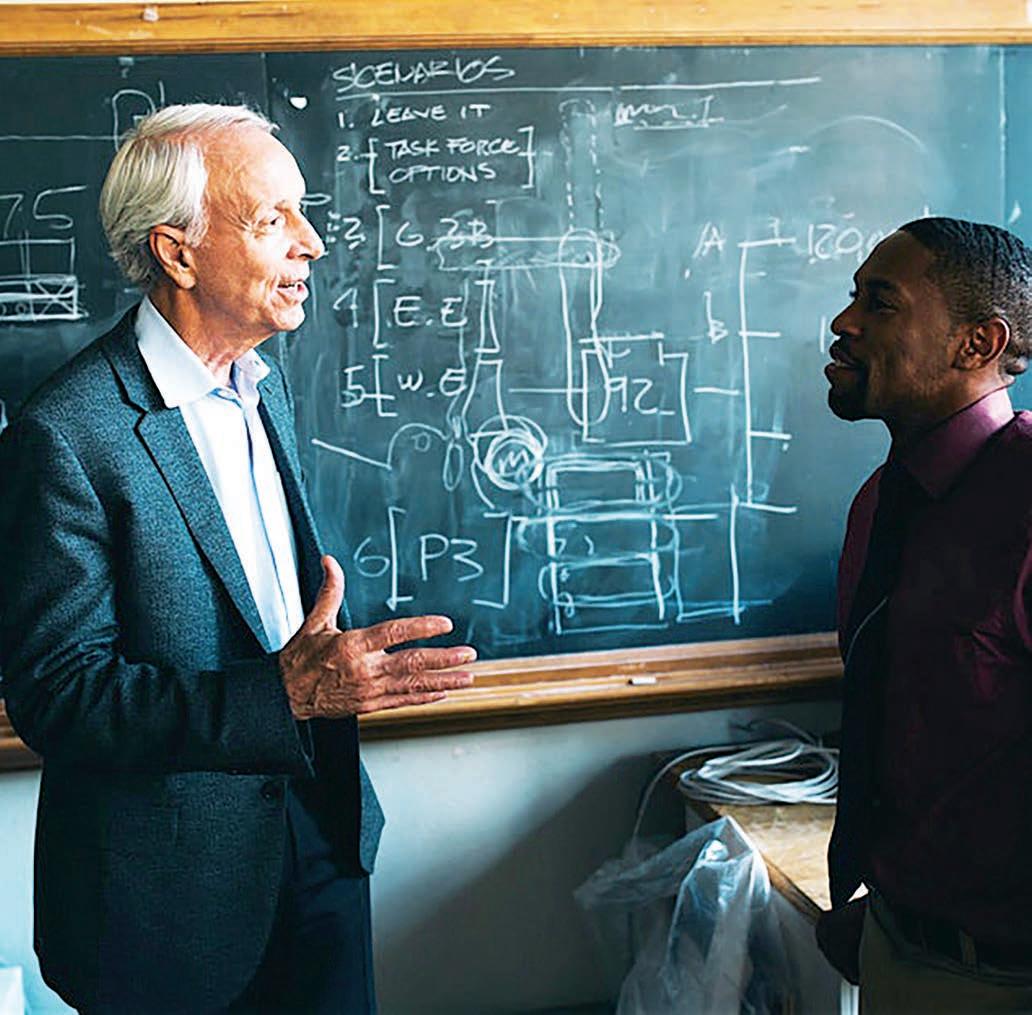

RIGHT R ichard Cleary, 2018.

LEFT M ichael Garrison, 1992.

ABOVE M ichael Benedikt, ca. 2011.

RIGHT M ichael Benedikt, 1978.

14 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

THINK LIKE AN ARCHITECT

students in their lives and to be sensitive to their circumstances.

MG We spend so much time with them that I begin to know a lot about them. I know where they’re from, their parents, their boyfriend, their girlfriend, their cat, their dog, what’s going on in their life a little bit. We’re looking for critical thinking instead of passive learning, and so to me, the important word is “induce”—to get something out of them that’s latent and build off of that. I’m trying to get them to open up and have confidence, and that requires knowing them well enough that you can actually see when they’re excited about something or have an idea that they want to express.

LS I think the appropriate word in all this for me is “mentorship.” That’s very different from being a parent, from being a friend, and from just being a detached teacher. That’s not for every student—you’re not going to be the mentor for everyone—but there are going to be some students who gravitate to you and say, I want help, and I want you to mentor me.

RC Most of us weren’t taught to be teachers: I didn’t have any kind of pedagogy training; I learned to be a teacher by thinking about how I was taught, what I rejected, what I admired, then kind of figured it out. How do you think as experienced faculty we can inculcate this notion of mentorship in our young faculty?

MB I think Larry makes a very good and very wise point. Michael also spoke to that without using the word mentorship. What I try to do if a student is having difficulty in their life is induce them, as Michael would put it, to remember their love of architecture, to see that architecture is in a certain sense, salvific. That the problem in front of them, the design problem, is worthy of their attention and will carry them through.

LS It’s interesting when you teach a large lecture class, you would think, oh, you can’t really get to know the students very well. But there will be a group who come regularly in

office hours and just attach themselves to you.

They want to have that kind of mentorship. It’s not that hard when you’re teaching something, as Michael Benedikt would say, that they’re interested in. This is an important part of their life, and they see you as a source, someone who can help them.

RC What do you think it means to think like an architect? What is it at its heart?

MB Larry and I think very differently, and we’re both architects, so what it means to think like an architect, I’m not even gonna try.

LS Something I’m very keen on is that there is a way of thinking like an architect. There are some disciplines where you can think linearly and can get to the answer, but in architecture you’re always thinking of multiple channels at the same time, and it’s all about trying to get synergy out of combining this and this and that intention.

MB Larry, I’m going to agree with you that an architect has to think in a kind of parallel, multi-dimensional, there’s-got-to-be-a-wayto-optimize-everything-all-at-once way. A magical sense of production is something I think architects are very committed to. What we probably differ about is what should be in your head, what deserves to be on the table, so to speak. I have a much more abstract and idealistic view, I think, than you do.

MG But there is an “aha!” moment in design.

LS I think there are hundreds of “aha!” moments.

MB It’s a mountain of “aha!”

RC And as teachers, your role is to help students find that, or recognize it, or learn how to?

LS Not to find it one time, but to figure out how to internalize that way of thinking. They’re taught all the way through their education to think I’m trying to get the right answer. I go through these steps and it’s going to

lead me to the right answer. Well, that doesn’t work in architecture. You’ve got to come at it with about one thousand different parameters, and then you’ve got to optimize and synthesize and it’s just a different thought process. Actually, that thought process is very good for non-architects. I teach a class in creative problem solving, and that’s applicable in business, engineering, a lot of other fields, but it’s particularly applicable in architecture.

MB Yeah, when you’re teaching in that sort of close-up way, you think and you think, and you draw and you draw and you draw, and then the teacher goes, Aha! There it is, there it is, and the student looks at you and goes, There’s what? And you say, There it is, don’t you see? We did this, we did that, and it’s knocked over ten problems in one shot. And then they go, Oh yeah, oh man, yeah. In other words, they don’t get the “aha!”s automatically. They have to see you model what “aha!” looks like.

LS So this is a really important point; the other thing that I have really changed my thinking about in the last ten years is that architecture is a team sport and that, if we think of it as an individual thing, it’s very counterproductive. And, just like Michael said, they need someone else to look at it from outside and say, Damn! That’s amazing and here’s why… And that’s team activity. That’s more than one person.

MB Absolutely, yeah.

MG I agree, I think mankind got to be the head of the food chain by working together. It took a whole village to bring down a mastodon. That’s one of the things I hope that we get back to. That’s one of the things that I don’t think we’re doing enough of right now, and that is working together; there’s still too much competition.

RC Michael Garrison, Michael Benedikt, Larry Speck: thank you for this. It’s wonderful to have this discussion and hear your thoughts.

15

REFLECTIONS ON

31 YEARS AND COUNTING

TEACHING

RICHARD CLEARY

In 1991, Dean Hal Box recruited Kevin Alter, John Blood, Elizabeth Danze, and David Heymann as faculty members. Kevin is a graduate of Bennington College and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). Alumni of the UT Austin School of Architecture, John and Elizabeth had earned post-professional degrees at Yale and had practiced before their return to Austin. David, who also had considerable professional experience, came from a faculty position at Iowa State University. A native Texan, he holds degrees in architecture from Cooper Union and the GSD. They spoke about their experiences as teachers with Professor Emeritus Richard Cleary. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

RICHARD CLEARY What did you think you were supposed to be doing on your first day at the School of Architecture?

ELIZABETH DANZE Having come from here, part of what I thought I would be doing was to bring the insight that I had gained as a practicing architect—and as someone who had spent time in the Northeast and at Yale—back to the school. Also, going away and coming back, I understood the school differently. I had some understanding of what the school was like as a student as an undergrad but, of course, coming back, it’s very different. It was also a little difficult, so it was both wonderful and very strange to be teaching with some of my professors from not that many years before.

JOHN BLOOD It’s a very interesting question, and it’s so rich to look back at this period. Both Elizabeth and I have the Bachelor of Architecture degree, and when we were in the program—and it’s still the case now—it was a very loaded program. There are very few electives and so much material to cover; it’s a serious professional degree. When we went to Yale as post-professional students, the curriculum there was completely open. Each semester we took advanced design studio and then any three electives at Yale we could get into, which was a completely different world. The biggest lesson in that for me was a sense of responsibility for my own education and trajectory in the world. I’ve tried to infuse that into my work as a teacher— this idea that we’re not only designing the project or building in front of us, but also approaching our lives as a design project.

RC It’s interesting to hear you to say this, John, because, Kevin, you’ve often said that you believe our school is a place where students are responsible for their own trajectory, particularly the graduate students, but also undergraduates. I can see you getting that at Bennington.

KEVIN ALTER I think there are two ways to answer. One is the lessons learned from my personal trajectory, and the other is responding to this new place. I think Hal, and Larry [Speck], as the effective chair at the time, gave us both the privilege and the

dilemma of extraordinary leeway. We were assigned courses to teach, but there certainly wasn’t a set curriculum, so we had to invent these courses. At Bennington, taking charge of your own trajectory was a crucial aspect of the educational model. In contrast, Harvard’s rigid curriculum was a shock for me. As much as it was an extraordinary experience in respect to the things to which we were exposed, it wasn’t the same kind of generous teaching institution that I knew. Coming to the University of Texas, I was interested in bringing the best of both worlds to my teaching. I saw an opportunity to introduce other work and ideas as a way to expand the conversation that was happening at the school.

DAVID HEYMANN Hal Box! I met with him, and he said, The only thing I need you to do, David, is improve the passing rate on the site design portion of the licensing exam. I go, Well let’s talk about the curriculum. He said, There’s no curriculum. There’s a bunch of strong professors. We hire strong professors. There was no written curriculum, which just blew my mind! I think it blew all our minds! What I also liked about UT, aside from the autonomy, was the fact that the school was actually interested in buildings, not necessarily as kinds of representations which was the case at almost every other school.

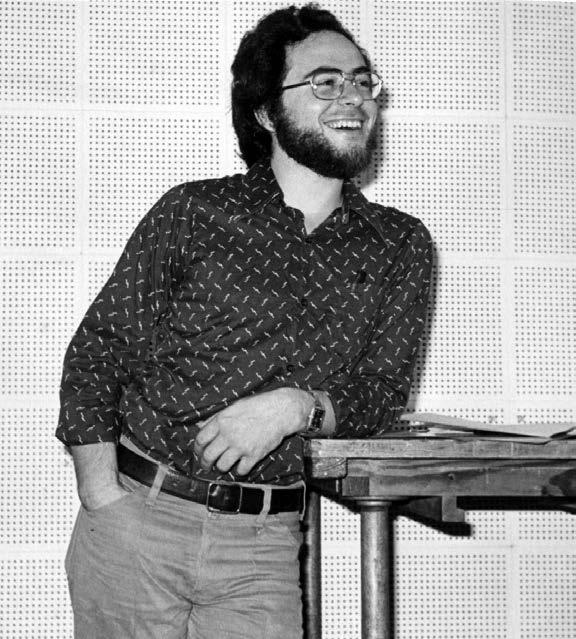

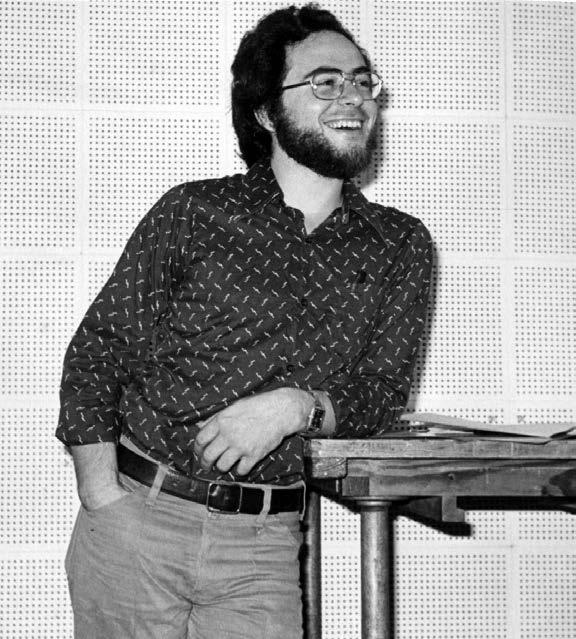

17 LEFT John Blood, 2012.

KA I think we felt like we were empowered and part of a wave that might change the school— and that was exciting.

RC What would a conversation between your 1991 self and your 2022 self say about what you think you’re doing here?

DH You don’t want to go there, Richard! In all fairness, I’ll say some things are the same for me. What I was mostly interested in—still remain interested in—is how buildings are extraordinarily meaningful single things. What is the value of the specific thing that you’re working on? How does it carry meaning? How is it meaningful at all? It’s the basis of the theory course I teach. It’s the basis of my studio teaching. How can we talk about it not so much as an exercise in formal development, but as a thing? As a part of the world? That remains true for me, and I think that’s one of the things that connects the four of us together.

JB The question is fundamentally different if it’s the older me talking to the younger me, or if it’s the younger me talking to the older me. So many things are different, and so many things have not changed at all. The tool set has expanded and changed for better or worse, but the questions and discourse are fundamentally the same. Elizabeth and I have practiced together; we’re grounded very much in the making of real buildings and have a commitment to that. But I have always had an interest in other things, or mutual things. I’ve had the great luxury to work in film on a regular basis. In trying to look at the whole picture, trying to look at it from my young self and my current self, I have constantly had to ask—and these are questions I’ve been asking for thirty years—What’s the common thread between the two? How do they inform each other? Or are they completely different disciplines? I don’t think that they are. I think

their relationship has to do with enriching human experience, whether it’s the creation of a building that solves a problem, creates a certain kind of environment, and awakens your sense of being a body in space and a person in the world, or if it’s a visual experience encapsulated within a film that expands one’s understanding or what you might imagine your world to be.

ED When I first came here and was teaching, I was interested in architecture in a sociological kind of way—its place in the world and society. But what I found was that I inherited a role that I wasn’t expecting: that I was a woman architect teaching at a school where there were not a lot of other female professors. I had two children—John and I have two children together—and in some ways I didn’t expect myself to be in that role of representing a woman who had children, who was negotiating a practice and teaching in the classroom with students who are often asking me, If I want to have a family, how do I do this? Looking at how I teach now and what I think about when I teach, I do look more holistically at the student. I think the student wants to be understood that way—who they are, where they come from, what their life experiences are, what they are dealing with financially, psychologically, emotionally.

DH One of the particular dilemmas for Elizabeth in this case is that, especially in the early years that we were here, we were trying really hard to increase the number of women in the student body, and there were few role models for them to turn to. I would go into Elizabeth’s studio, and it was a different discourse that she was being asked to deal with. I think it’s changed somewhat, but not 100 percent, that’s for sure.

KA I feel my role at the school has changed. When I arrived at UT I felt like there was a broad agreement on what architecture was, and that allowed me to play the role of an irritant— in the same way a grain of sand might irritate an oyster and produce a pearl. Over the time that we’ve been here, that broad agreement has disappeared from our school—and I think that was intentional. The school was clearly interested in broadening the way we looked at architecture, which in many ways was really important. But one of the consequences has been that there are many different voices at our school and no general agreement on the discipline’s core values. And so, I have seen my role evolve from being an outsider trying to broaden the school’s focus, to one where I’m trying to reinforce a kind of centerline of the discipline. For me, that is an interest in artifacts and how they carry meaning.

DH Now that you mention it, Kevin, things have changed in terms of where we position ourselves. When I came into the school, I was much more vested in practice and the possibility of practice, and over the years I’ve become much more doubtful about that. Many of us have diverged in different ways and play different roles in the school, but there isn’t a very effective way right now to use that difference in a powerful way. Maybe that’s too generalized, but it is interesting to think that, in actual fact, we have evolved quite dramatically.

RC I want to come back to some things Elizabeth was saying. This has to do with how you manage your relationship with students day-to-day, through a semester, and, sometimes, over years. I can imagine, Elizabeth, that in your work these questions have come up.

ED Sure. To start with, there is a power dynamic at play between a teacher and a student that needs to be recognized. I think students feel it and recognize it, and as teachers we do, too. I have recently become very interested in the relationship between the teacher and the student, and I’ve been looking at it through another professional lens, which is the therapist and the patient. To me, that’s super interesting because there’s also a power dynamic, but also a kind of emotional intimacy. I think that can happen when you get to know a student over many years or the many hours that a studio demands. One of the things that I have been writing about recently is how the student takes in the teacher

18 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

What I was mostly interested in—still remain interested in— is how buildings are extraordinarily meaningful single things.

RIGHT

BELOW John Blood, 2018.

19

Kevin Alter, 2022.

LEFT E lizabeth Danze, ca. 2009.

DIALOGUE TRAJECTORY

emotionally, and how the teacher, aware of that, can understand the power and impact that they have with the student. At first I thought I would be teaching from a place of reinforcing a healthy learning environment in the classroom. But over time that has evolved into something much deeper and gets back to how students want to be understood holistically. They don’t just want information given to them like they’re an open vessel to be receiving information. They want the dialogue to go back and forth.

KA I think the studio’s unique setting does encourage that kind of emotional intimacy and role modeling, and, in many ways, lifelong lessons beyond amassing knowledge in the field. I suspect that as young teachers, we were modeling ourselves on the teachers we had experienced and admired—at least I was. Our role was largely about providing exposure by curating precedents, architects, and theories based on our students’ individual interests—because at that time such information was difficult to ascertain without that guidance. Now, with so much information literally at our students’ fingertips, I’ve changed my role to be much more about interpretation, rather than introduction.

JB The really good news here is that we’re not in the business of just imparting our knowledge. There’s more than one way that buildings can be interesting. We live in a rich and wonderful world and have this opportunity to be in dialogue with students and to listen to them. That’s the real challenge: to build your ability to listen, be open to, and absorb what students are interested in.

DH We all came through kind of toxic educations—not just ones that had to do with relationships between individuals, but with power structures: how power structures were inculcated, and how people were belittled and so forth to get them to do work. I have to say that in our school we got to witness that get, to a certain degree, wrung out. One of the things that to me has arisen out of the studio

culture movement is to make the processes of discovery and design more uniform and more doable, so the students are guaranteed results, as opposed to the high-wire risk you take going into a design process and the role of the professor was not to tell you how to get to the end, but to be a safety net. I think that has changed. I don’t know if the three of you agree, but my own feeling is we came into the school very much in the safety-net mode; not in the telling-you-what-to-do mode.

ED When I first started teaching, I thought there was going to be a group of students in my studio, and the best thing I could do for them would be to get out of their way. To be there, have conversations with them, but just move out of the way. I don’t feel that very much anymore. Instead, I’m being asked to check what they’ve done. I’m asked, Is this what you want? My expectations coming into the school, and my own expectations as an architect and as a student were, You do the work, and it’s on you. I now feel more and more that it’s on the professor, somehow.

KA I like David’s thinking about faculty as safety nets. Obviously, our roles have always been about more than that; it is also supporting and directing. I love the Montessori term for teacher, the guide, as someone who’s there to help, but the individual drives their own education and the guides keep students from going off the rails too far. I love that students now expect to be treated professionally—that is a wonderful evolution from our experiences when we were in school. However, I agree with Elizabeth that the current model occasionally feels like as teachers we are being asked to red-line or correct students’ projects. Still, I prefer students to have an emboldened set of expectations to the model in which we were educated.

DH I think both Kevin and Elizabeth are correct that it shifts to a kind of professionalism, but that professionalism isn’t necessarily based on the profession.

It’s based on a certain level of expectation that still requires honesty and, often, quite severe and hard criticism.

JB Yeah, at the core is my belief in the value of an education where students can be creative, truly creative, and approach problems in a manner where you’re both trying to see the whole picture and working on specific parts of the problem at the same time. You get to do both of those things in a world that seems to get much, much more specialized.

DH Could I throw one more thing in? When I think about the way all four of us teach, more or less the mechanism is to have a very clear conceptual goal in mind, as opposed to a very clear building. And then you set up an infrastructure that gets the students rolling in order to get out of the way. That’s the whole idea: to figure out some mechanism that gets students rolling, whether it involves travel or involving other people, but it sets aside the idea of a formula. And then you begin to find out which of these students really stand out and which have remarkable ambition and so forth. One of the things about the four of us, in particular, is that the bottom in the studio tends to do well. Michael Benedikt has remarked on that saying, The four of you, you are so good at lifting the people who are not doing so well up.

RC It’s been so much fun to talk about these ideas, which are, as we all know, very hard to talk about during the semester. It’s good to reflect about why we’re here.

20 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

21

LEFT Kevin Alter, ca. 1995.

BELOW D avid Heymann, 2019.

LEFT D avid Heymann, ca. 1995.

NOT SO

22 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

LIKE-MINDED

FRANCISCO GOMES

There are new voices in the hallways, stu dios, and seminar rooms at the School of Architecture. Todd Brown has brought his expertise (and PhD) at the intersection of architectural and environmental perception, environmental justice, and social equity to conversations about inclusion and socioracial sustainability in design thinking. Stephanie Choi has led design studios integrating her interest in the interrogation of power struc tures with her substantive experience bridging installations and architecture in design practice. Tekena Koko’s interest in media and representation have informed his design stu dios and a seminar exploring the boundaries of architecture, landscape, and art. All three are fellows of the School of Architecture, a relative ly new faculty role which is neither lecturer nor tenure-track, designed to enhance the discourse and enrich the academic mission of the school with fresh thinking.

THE FELLOWSHIP POSITIONS

The School of Architecture has created a constellation of rotating full-time, two-year academic fellowship positions for ambitious scholars and design thinkers. In addition to a fellow of Race and Gender in the Built Environment of the American City and an Emerging Scholar in Design, the school most recently added a position for an emerging scholar whose expertise is not constrained to the design disciplines.

The first, established in 2016 in accor dance with a plan authored by the school’s Committee on Diversity and Equity, is the Race and Gender in the Built Environment of the American City fellowship.1 Initially, this fellowship had a term of one academic year, which put the fellows in the challenging position of having to begin searching for

the next stage of their post-fellowship career nearly as soon as they arrived on campus. We are thrilled to have Todd Brown, the seventh recipient of the Race and Gender fellowship, as a faculty colleague at the school and the first to begin this appointment with a two-year term.

In 2017, initially with funds cobbled together from the professional track teaching budget,2 we created the Emerging Scholar in Design fellowship. Established with the goal of bring ing new ideas and discourses into the academic community of the school, this position encour ages our invited scholars to develop their work through teaching, research, design speculation, and writing.

This visiting faculty member teaches design studios, including at least one advanced design studio, and seminars specific to their research project with the expectation that their intel lectual agendas will be disseminated through talks, an exhibition, or a publication as their two-year term comes to a conclusion. Like our Race and Gender fellow, the Emerging Scholar fellow is a full member of our faculty and is brought to our academic community through a rigorous search committee process that paral lels a tenure-track faculty search. Tekena Koko is our current Emerging Scholar in Design and is halfway through his term as the third fellow appointed in this position.

The success of the Emerging Scholar in Design fellowship led to the creation of a second Emerging Scholar position in 2020. Because teaching and scholarship at the school are not limited to the design disciplines of architec ture, urban design, landscape architecture, and interior design, neither is this second Emerging Scholar fellowship. In cases when a design scholar is selected for this second Emerging Scholar position—as is the case with its first ap pointee Stephanie Choi—their ambitions and responsibilities parallel those of the Emerging Scholar in Design. When a scholar in plan ning, history, preservation, or sustainability is selected for this position their teaching and research activities might vary markedly, but

they still have a somewhat lighter than typical teaching load and the encouragement to engage and broaden the discourse of the school, and to advance their discipline. By the time this essay is published, our academic community will have welcomed our newest Emerging Scholar, Tyler Swingle, to campus.

THE FELLOWSHIP GOALS AND CHARACTERISTICS

This type of fellowship is not unique to our school. We owe a debt to similar programs at Rice University, the University of Michigan, MIT, Princeton University, and others that offer valuable models. However, UT Austin has some important distinctions from these programs. Most notably, the University of Texas and Austin are particularly sticky places for a career in the disciplines addressing the built environment. Perhaps it is the collegiality of our faculty and professional communities, our beautiful campus, the scholarship and practice opportunities that arise from our rapidly growing city, or maybe it’s the live music scene. Whatever the reason, once here, our faculty tend to stay in Austin. The fellows provide continuous aeration of new thought flowing through our buildings, and this alone makes the program immeasurably valuable.

The terms, teaching responsibilities, and even the titles of the fellowships have evolved slight ly over time as we have learned what is best for both the fellows and the school, but the goals that characterize the fellowships have endured:

The Emerging Scholar and Race and Gender fellowships exist to explore ideas and enhance discourse around what matters—or should matter—to the disciplines addressed by the School of Architecture. Though the earliest Emerging Scholar fellows were required to teach a full “2-2” schedule to justify the funding of the nascent program, today their teaching is reduced by at least one course per academic year and all teach an open-topic seminar annually, allowing them to advance

23

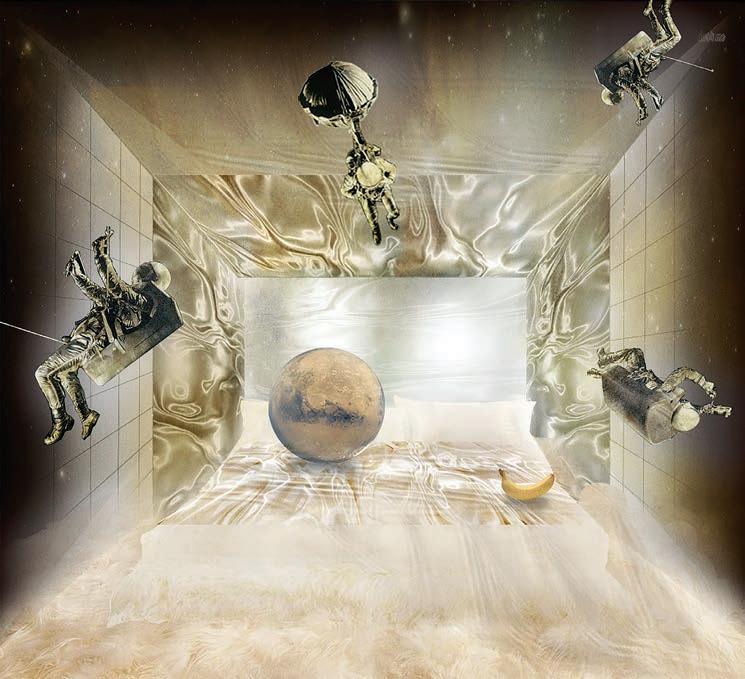

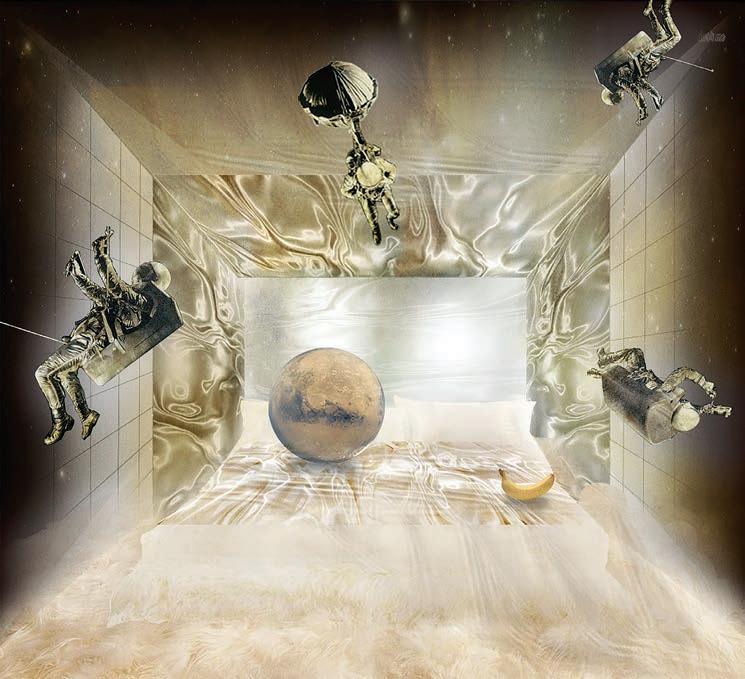

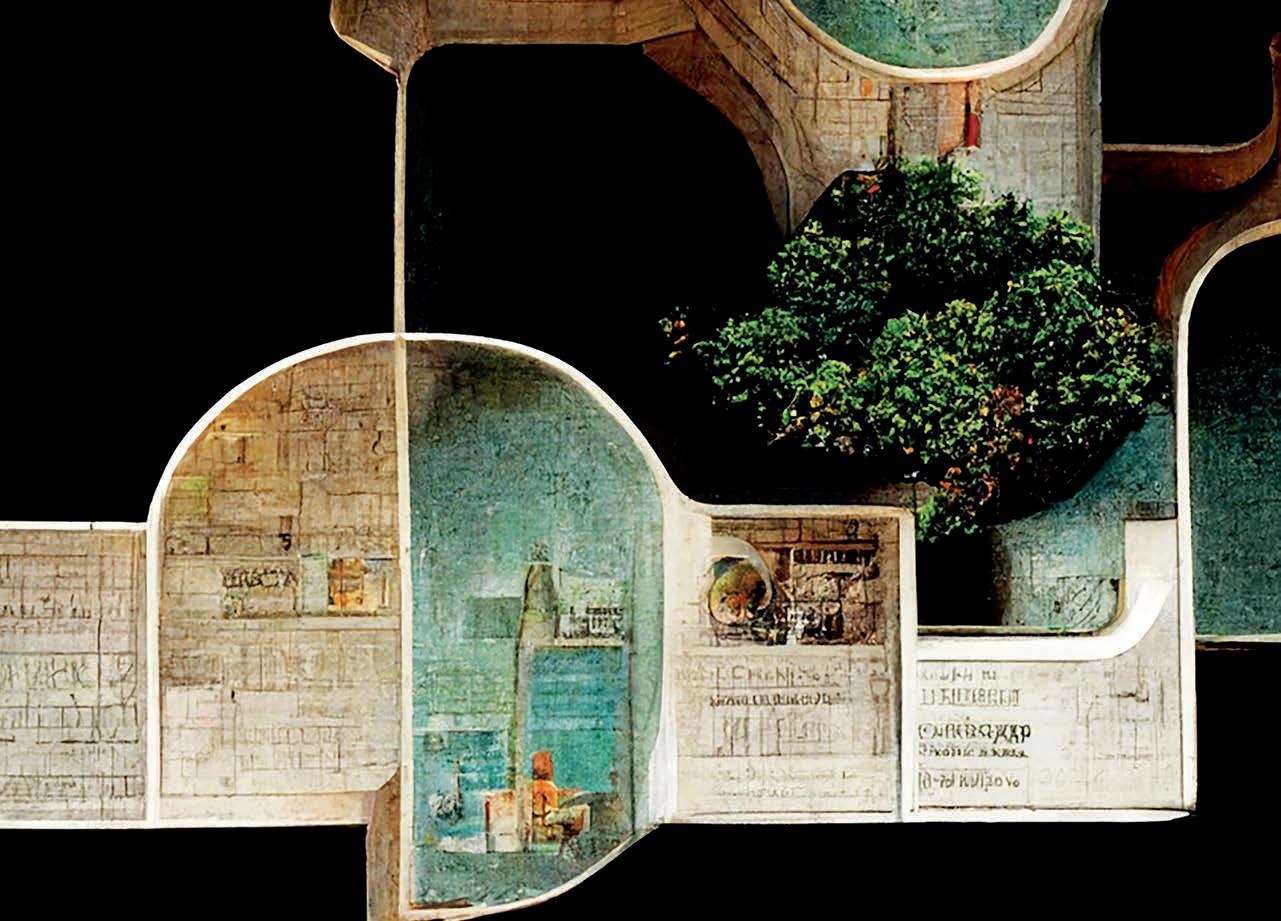

LEFT Josephine Baker sleep portal, work-in-progress by 2020–2022 Emerging Scholar Stephanie Choi.

their scholarship interests. For design faculty, an annual advanced studio with the curricular flexibility to be structured around their re search is similarly provided.

Much of the discourse of the school occurs beyond direct teaching engagement with students, through the informal discussions that develop across guest lecturer visits, design crits, committee meetings, and prolonged hallway greetings. The fellows are asked to extend this discourse more formally—typically during the second year of their appointment after they have had a chance to advance their work—through lectures, exhibitions (physical or digital), and workshops. Many also speak and publish in academic and professional venues beyond the University of Texas, and almost all have given talks as part of the forum series hosted by our Center for American Architecture and Design.3

The fellows are selected by our faculty in a process that mirrors a full tenure-track faculty search. It is an extremely rigorous multi-stage application, review, and interview process en suring the school engages the very best scholars and designers possible, while also providing the incoming fellows the credibility engen dered by this faculty-led process.

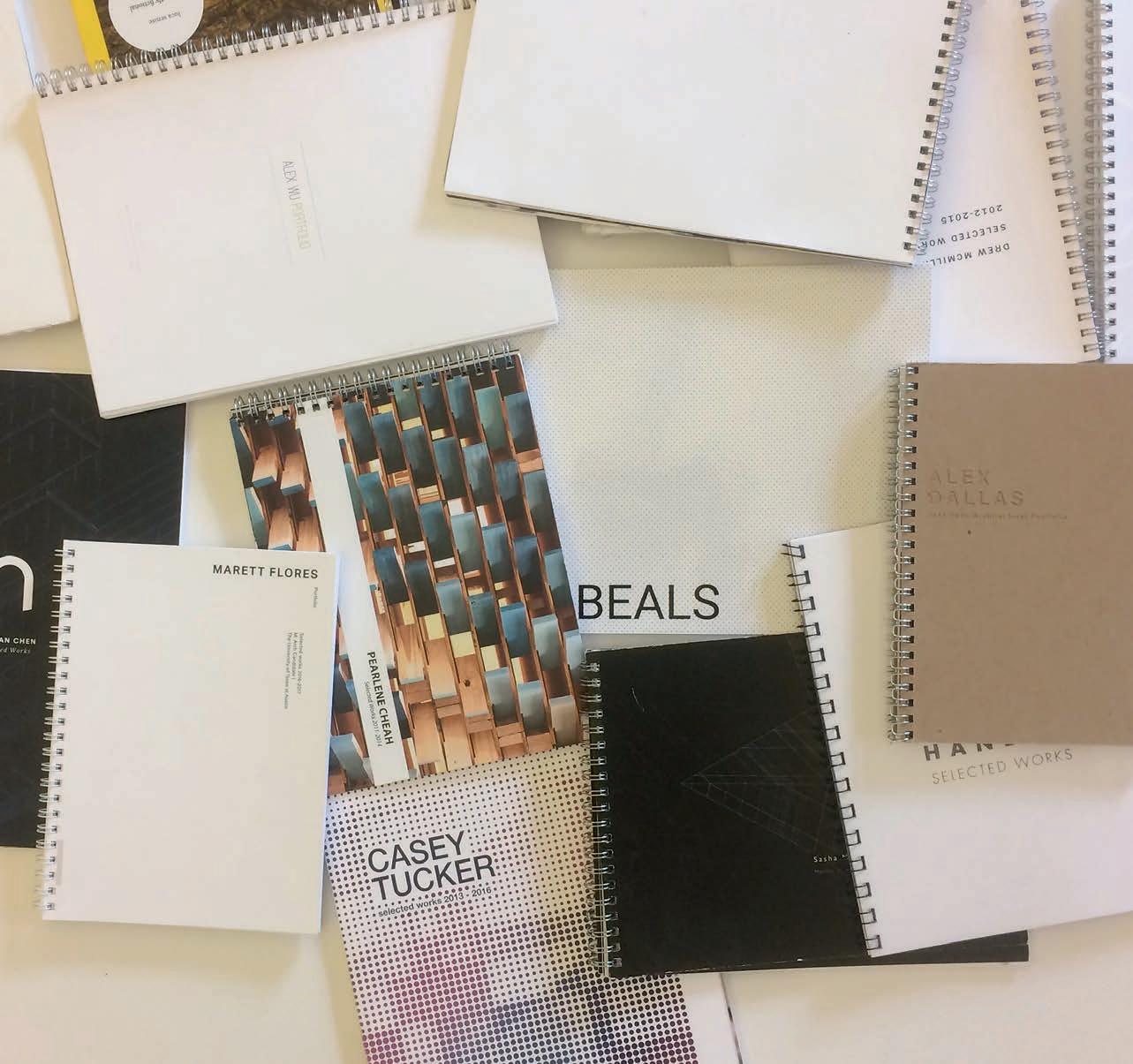

The appointments support fellows in their intellectual development and production of critical design work and scholarship needed to advance their academic and professional careers. Indeed, the fellows to-date have a re markable post-fellowship record including ten ure-track teaching appointments, acceptance to PhD programs at prestigious institutions, significant publications, and national design commissions and awards.

We hope that the fellowships will enhance the network and reputation of both the fellow and the School of Architecture. As the number of fellowships has grown, the school has moved to two-year terms for all the fellows, with staggered terms to maximize overlap and the development of intellectual networks among the fellows. With most of the fellows at an early stage in their promising careers, we antic ipate that they will spread word for many years of what we hope is a formative, productive, and

positive experience at The University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture.

EXTENSION OF THE FELLOWSHIP PRINCIPLES

We anticipate that the topics engaged by the fellows during their time at the school will influence the future of both our academic community and our disciplines. A more local way of looking forward is to speculate on how the values that shaped the fellowships might positively impact other aspects of the school. Phrased differently: if these fellowships are good, what other actions founded on the same principles should be considered?

I believe that a greater variety of perspectives and pedagogical approaches represented by more, and more diverse, scholars engaged with the School of Architecture is inherently valuable to academic discourse. But this is only a hypothesis; it may be that younger scholars are simply more attuned to the relevant issues and methods of the future. It’s also possible that a delimited two-year term of engagement couples a sense of urgency with the freedom to drive more risky ideas than that of faculty facing periodic reappointment or future “upor-out” tenure decisions.

As an example, we can speculate on the im plications of the first tenet—that a broader diversity of ideas and work within the school is a positive characteristic—as applied to the design studio. If true, that principle suggests the reconsideration of highly coordinated studios—those that share the same program, site, and schedule—in the early years of many

architecture curricula, including our own. The fellowships, for those who operate in the de sign disciplines, include advanced design stu dio assignments precisely because that is where instructors have the most freedom to structure a studio around their ideas. As a result, these studios are rich with variety and speculation.

It seems possible to change the nature of coor dinated studios to ensure that essential com petencies are addressed without unnecessarily constraining the range of ideas and hypotheses that these studios explore. Core design studios have the responsibility to teach particular skills, but all design studios could be funda mentally about exploring the design implica tions of a range of values. One doesn’t preclude the other and it’s probable that design students will engage in the conceptual interrogation most advanced studios demand more robustly if introduced to thesis-based studios earlier in the design sequence. Relevant design, represen tation, rhetorical, and other skills appropriate for a particular studio level can be addressed in the curriculum while still allowing faculty to structure each studio’s assignments to explore a well-defined thesis. Like the fellowships, this simple change might enhance our thriving school through discovery, innovation, and the expansion of our disciplines.

I am gratified to have played a role in the establishment and expansion of the fellowships at the school during my recently completed five-year term as an associate dean. My hope is that the School of Architecture and its faculty and students are better for their existence: re spected and engaged always, but hopefully not so like-minded.

RESPECTED AND ENGAGED

24 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

The fellows provide continuous aeration of new thought flowing through our buildings, and this alone makes the program immeasurably valuable.

EMERGING SCHOLARS IN DESIGN

Juan Jofre (2017–2019)

Design Studios: Intermediate Studio I; Intermediate Studio IV; Digital Drawing and Fabrication; Design I; Intermediate Studio

Advanced Design: Frenemies: Diplomacy, Architecture, and the Future of the US Embassy in Havana Seminars: Fortlandia: Outdoor Exhibit; Modules and Monoliths

Piergianna Mazzocca (2019–2021)

Design Studios: Vertical Studio; Design VI Intermediate Advanced Design: Objects, Systems, Technologies (with David Costanza); Architecture & The Future of Live Performance (with Igor Siddiqui); Good––Well, Better Seminars: For the Better

Tekena Koko (2021–2023)

Design Studios: Design IV Intermediate Studio; Design II Advanced Design: Performing Objects, Performing Subjects Seminars: Performing Objects

EMERGING SCHOLARS

Stephanie Choi (2020–2022)

Design Studios: Vertical Studio Advanced Design: Writing Prompts for Architects; Water Futures: A Desert Imaginary; State of Care/Body Talk Seminars: Illegible/Inconceivable

RACE AND GENDER IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT OF THE AMERICAN CITY

FELLOWS

Anna Livia Brand (2016–2017) Seminars: Race and Urban Development

Andrea Roberts (2016–2017) Seminars: Cultural Landscapes and Ethnographic Methods

See pages 76–79 to learn more about Dr. Roberts’ work.

Edna Ledesma (2017–2018)

Advanced Design: Advanced London Studio (with Simon Atkinson); Empowerment by Design: Brownsville West Rail Trail; Advanced London Studio (with Simon Atkinson) Seminars: Design and Informal City

Sara Zewde (2018–2019)

Advanced Design: Monuments, Movements, and the Mississippi River: Ecologies of Memory in the City of New Orleans

Adam Miller (2019–2021)

Advanced Design: Dragging Modernity: Between Beautiful and Ugly; Inside-Out: Public Parts in Private Seminars: Queering Architectural Taste

Todd Brown (2021–2023)

Design Studios: Studio workshops with Stephanie Choi (2020–2022 Emerging Scholar), Kevin Alter, and Danelle Briscoe, among many others Seminars: Racialized Urban Landscapes

work-in-progress.

STEPHANIE CHOI

2020–2022 Emerging Scholar

My practice, Daphne, imagines social possibili ties through research and experimentation. By exploring agency, ambiguity, and hybridity, Daphne seeks to build spatial justice through changes in the material and immaterial environment. In asking genealogical questions, our aim is to find new modes of relating to one another and new forms of collectivity.

25

T HE FELLOWS AND THEIR TEACHING

BELOW, RIGHT Josephine Baker sleep portal,

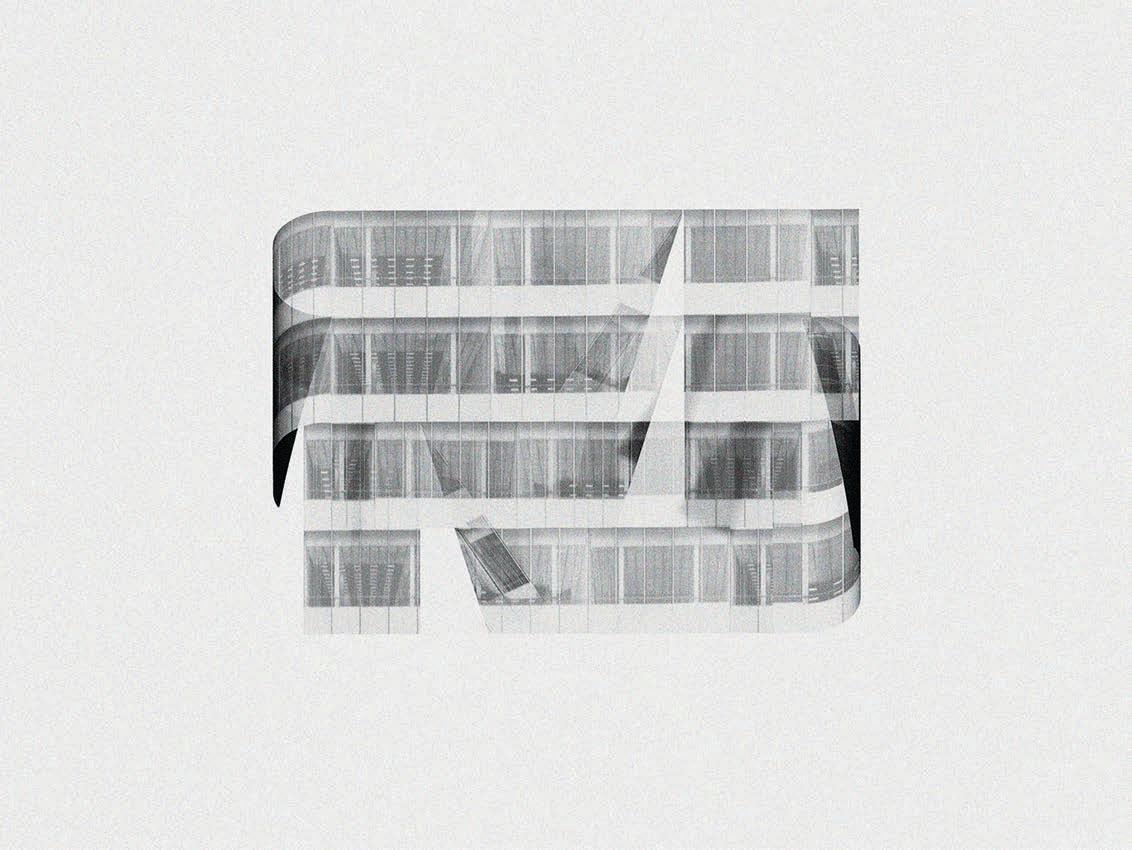

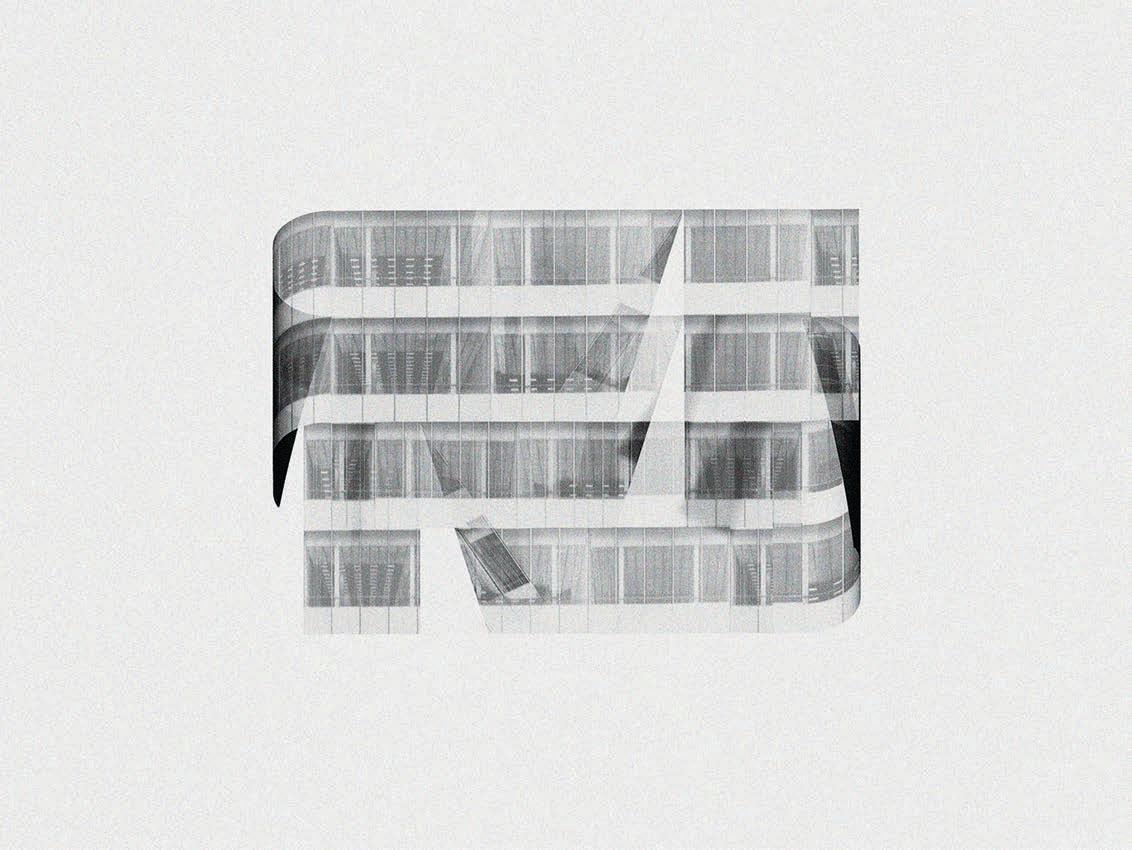

TEKENA KOKO

2021–2023 Emerging Scholar in Design

I am interested in the transfer of ideas and dis cursive processes from a closed disciplinary space of architecture toward a broader field of cultural consumption and evaluation. This extension occurs through the production of objects, instal lations, performances, teaching, and the design and making of buildings.

26 PLATFORM 2022-2023 TEACHING FOR NEXT

BELOW Shower Curtain Wall.

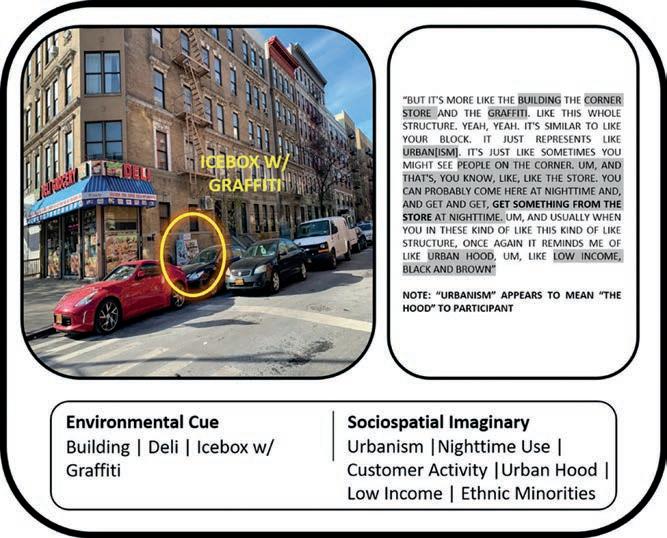

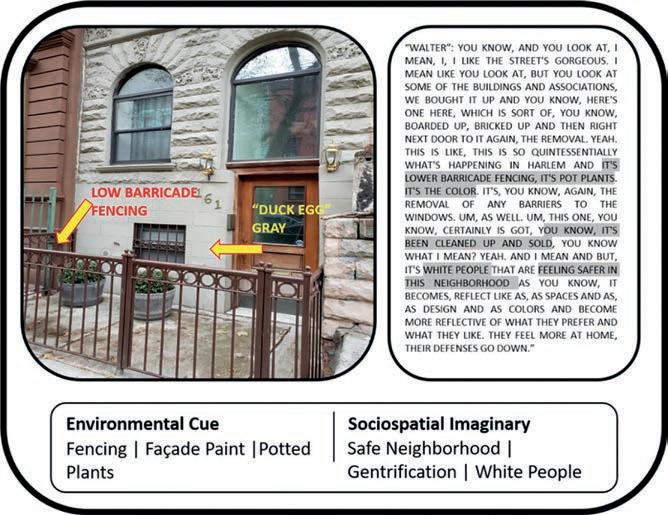

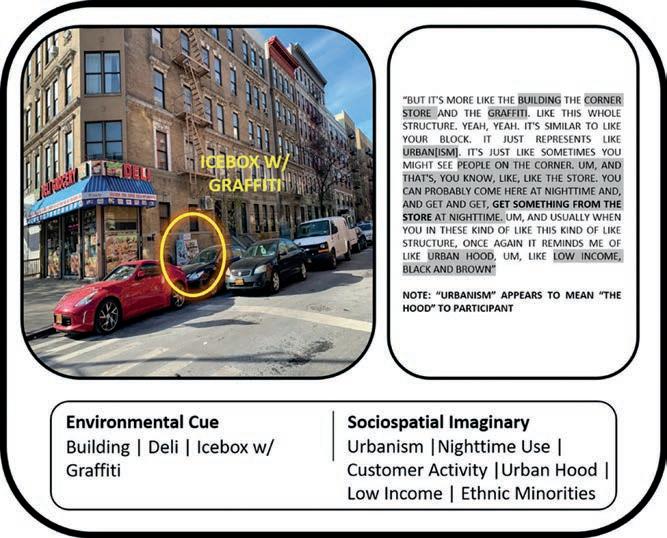

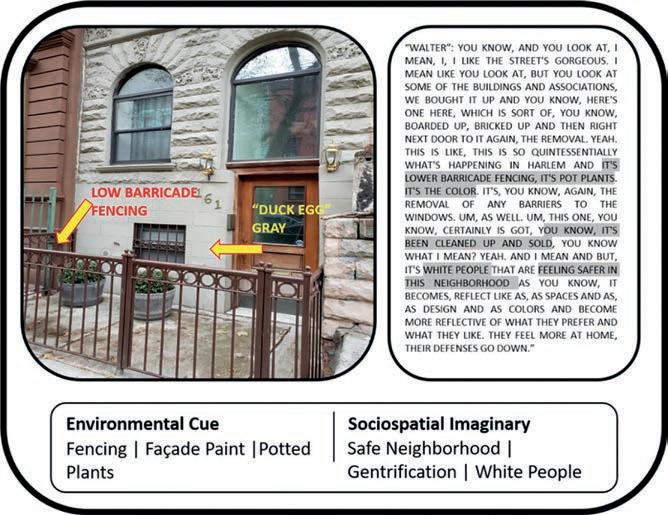

As a critical environmental psychologist trained in architecture, I examine the perceptions and outcomes of power structures embedded within the built environment. My research theoretically illustrates and empirically demonstrates how race, class, gender, and other psychosocial ideolo gies play palpable roles in the experience of space and place. The Race and Gender fellowship at the School of Architecture has been an amazing opportunity for me to bring my activist schol arship to architectural pedagogy and hopefully reshape how emerging designers consider the impact of their work.

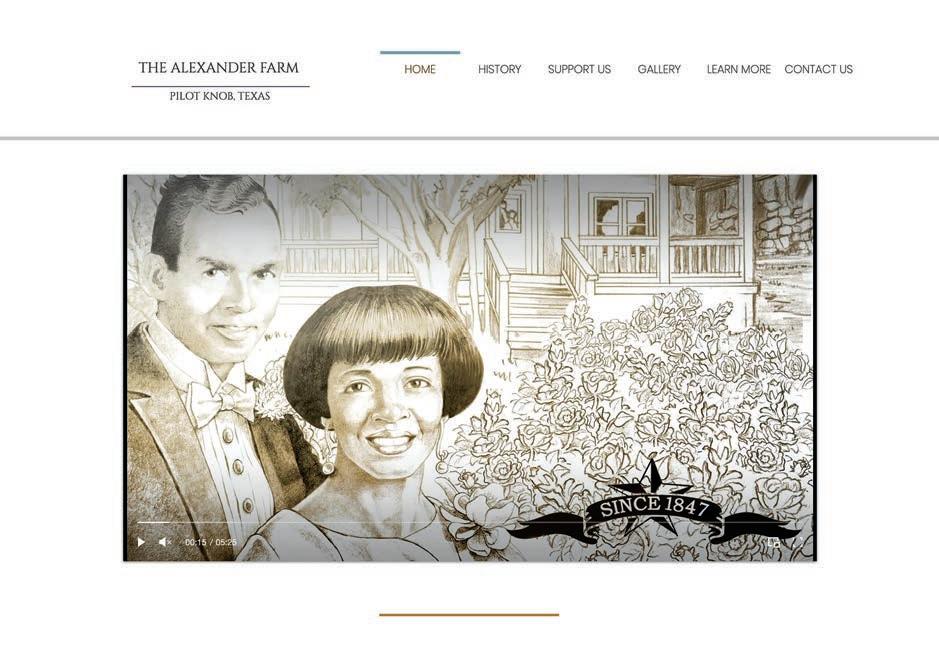

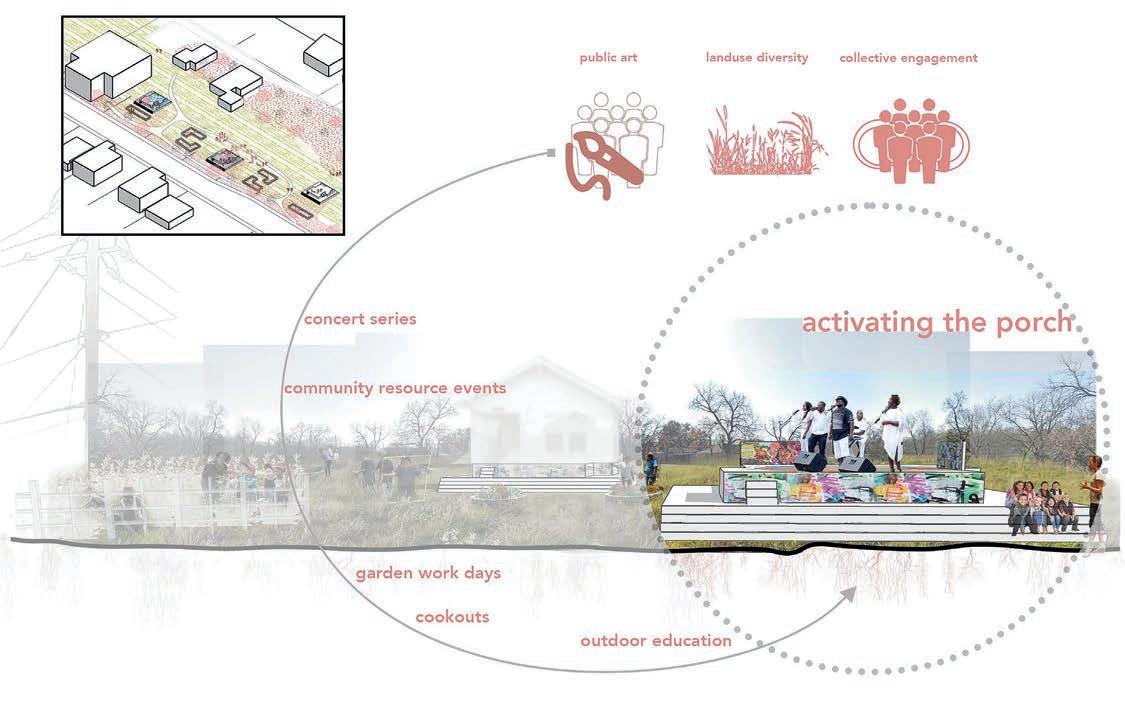

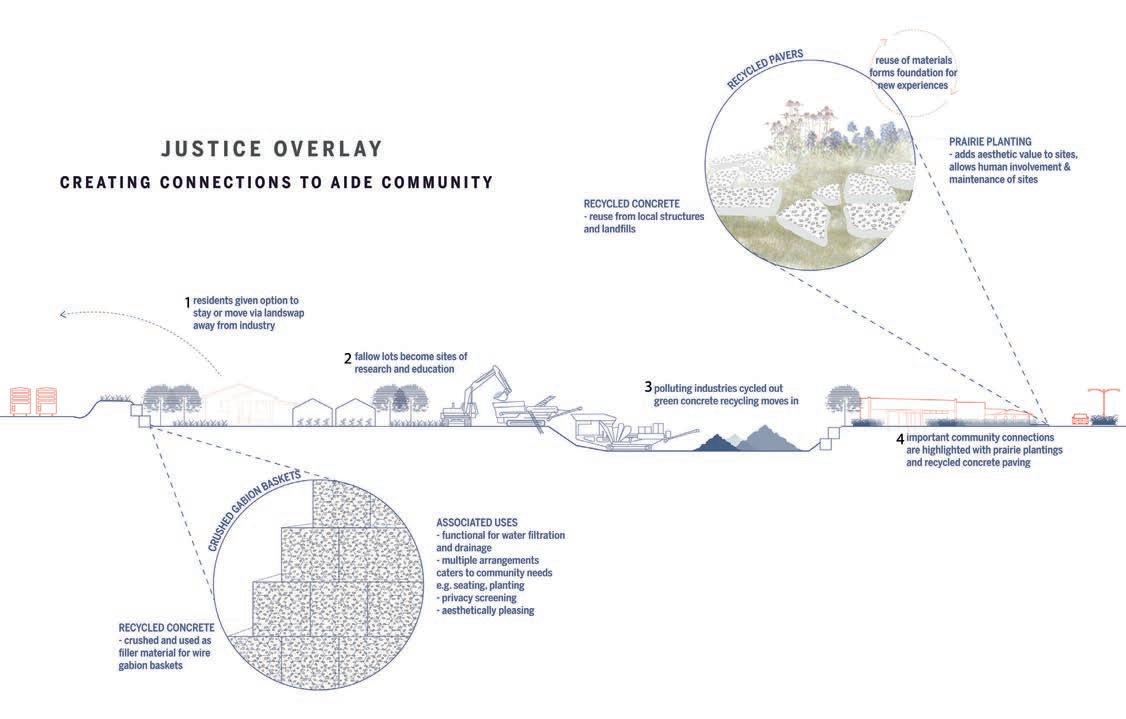

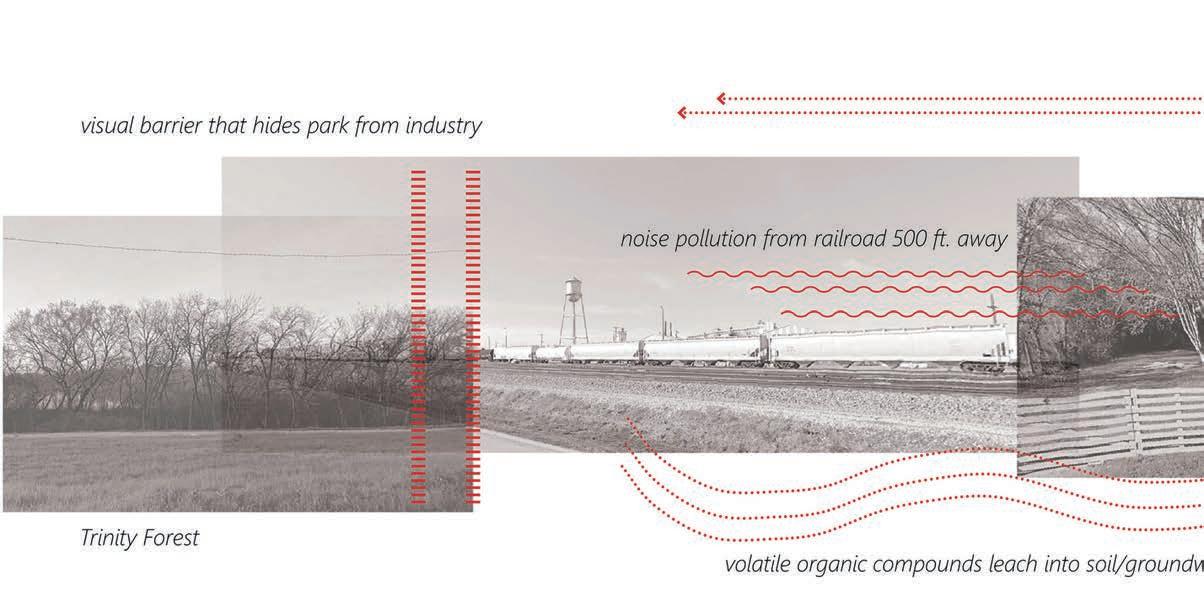

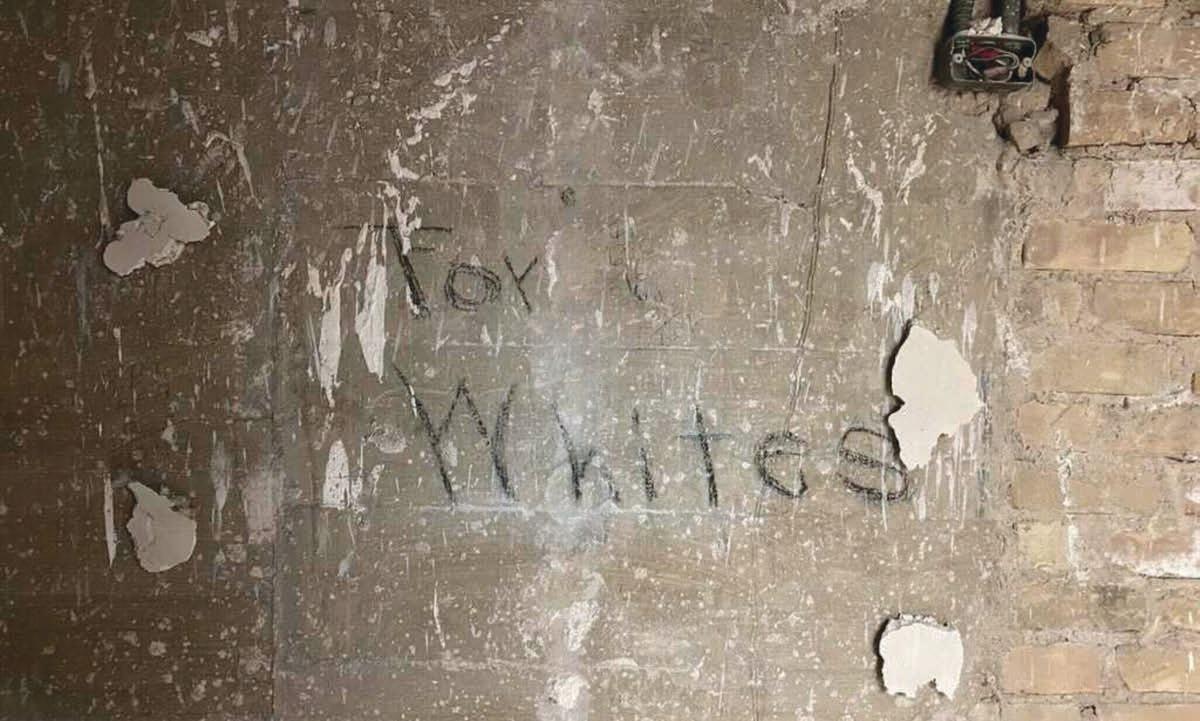

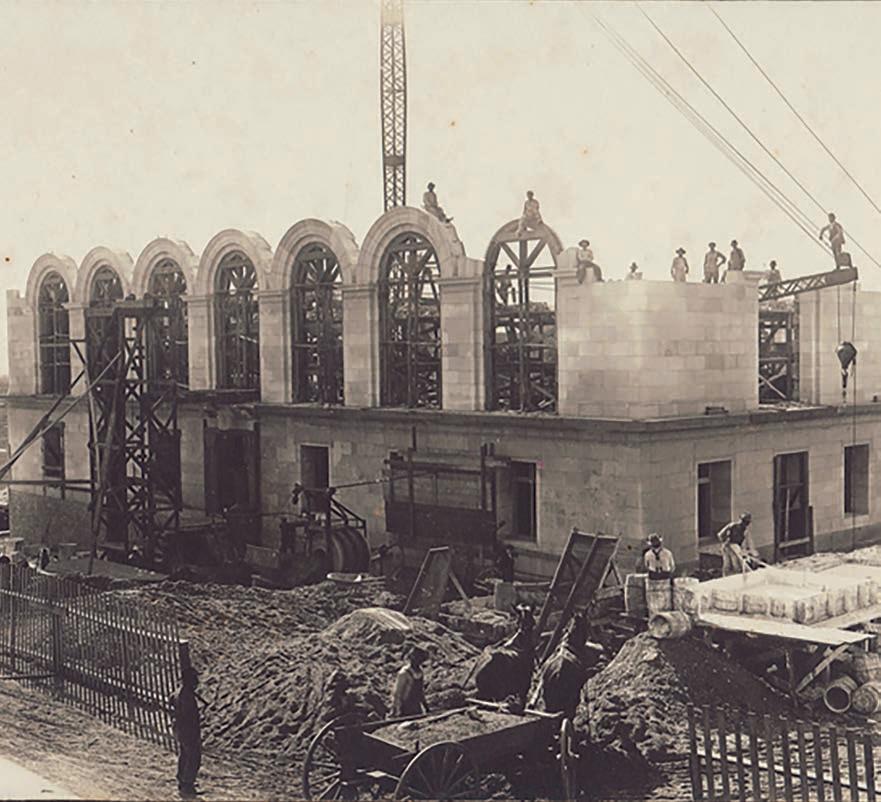

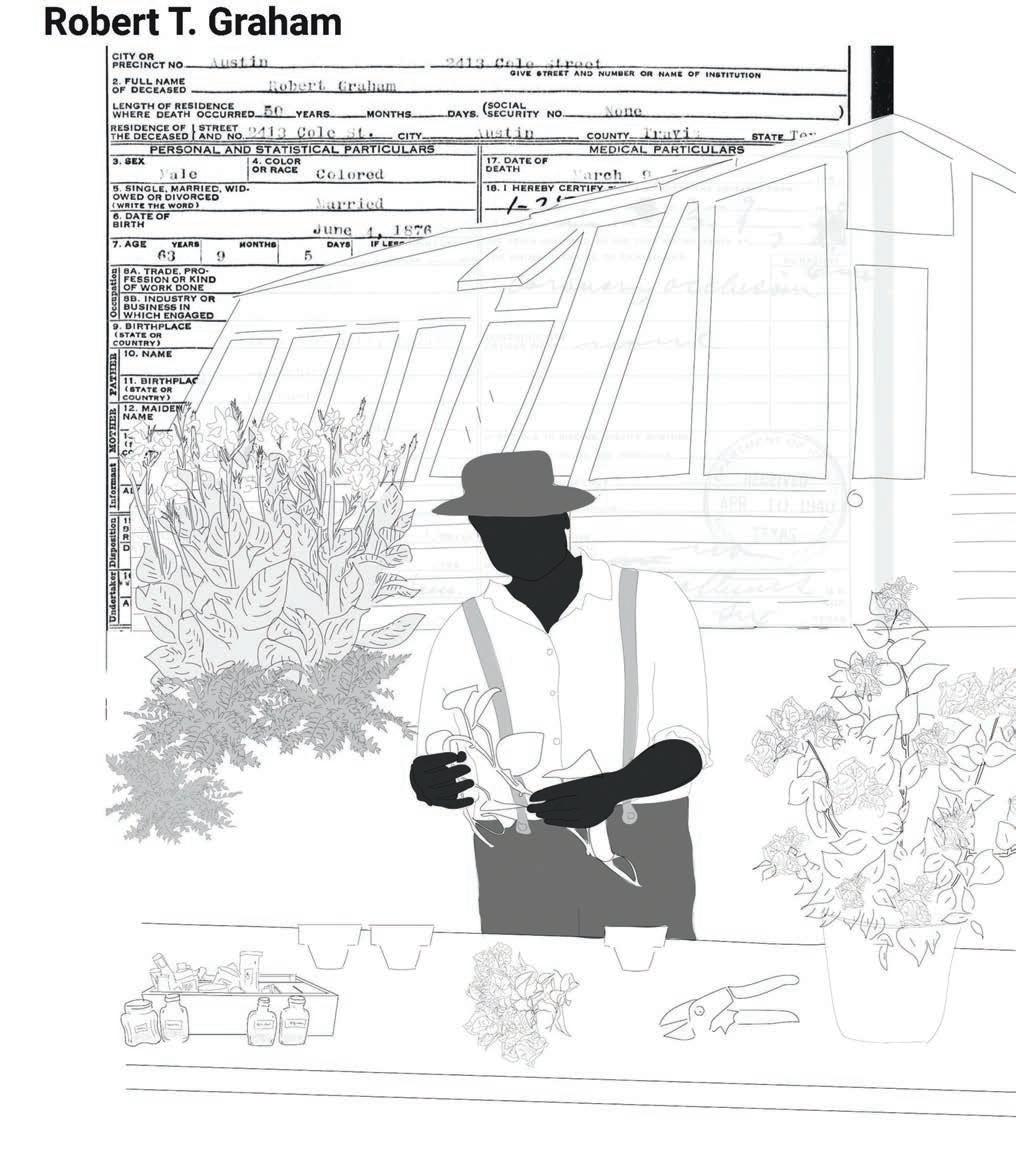

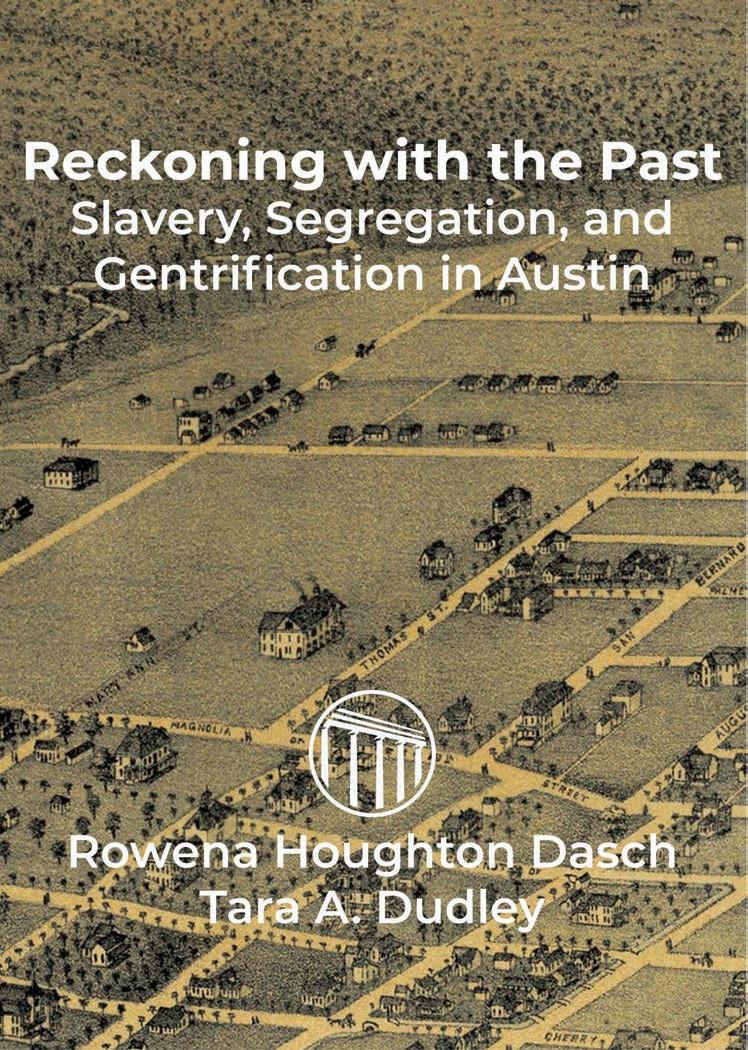

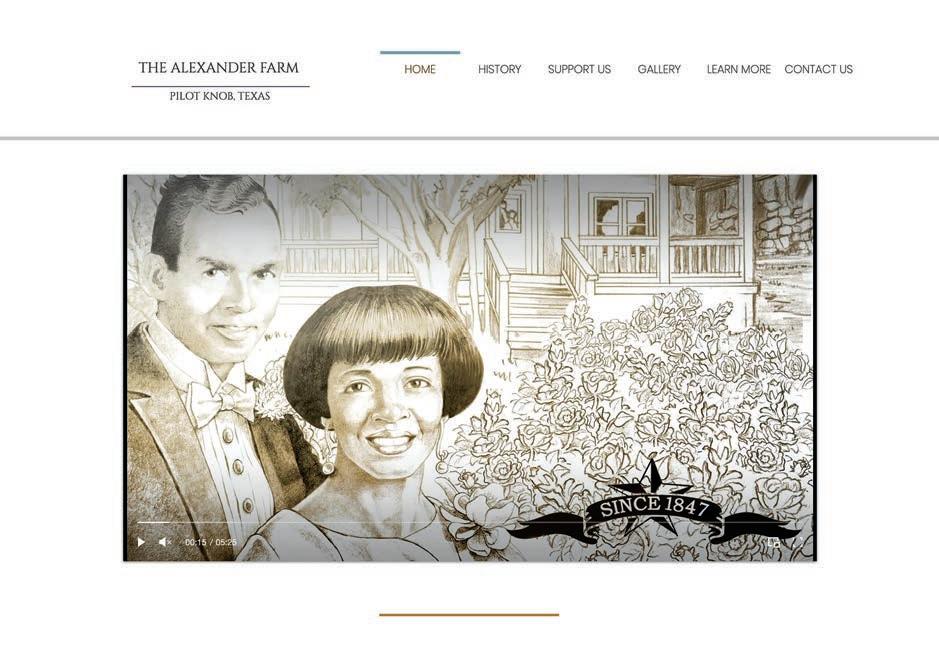

1. The plan included new tenure-track and tenured professor positions in addition to the fellowship, and the realization of the broader initiative owes a debt to Dean Addington who successfully advocated to the Office of the Provost for the university’s financial support of these appointments.