Take a nostalgic tour through the U District

Take a nostalgic tour through the U District

With plenty of charm and a vibrant downtown, Snohomish (population 10,000) sits at the confluence of the Snohomish and Pilchuck rivers. Originally used by the Sdohobsh (Snohomish people) and then populated with white settlers in the late 1850s, the city draws visitors with its scenic historic district and small businesses. This past year, through the UW’s Livable City Year not-for-profit initiative, Snohomish worked with MBA and Master of Urban Planning students to research the business landscape, look for opportunities for growth and help plan for climate change. A research team of students and faculty from the main campus and UW Tacoma found the business community wanted to promote tourism, preserve historic buildings and see more resources for community safety and small-business development. – Hannelore Sudermann

Photograph by David Ryder

TheUW astronomy undergrads test their cutting-edge coding skills in the cosmos, interpreting what a revolutionary new telescope will discover in the night sky. Their research helps scientists like Professor Mario Jurić (far right) observe present phenomena and unravel the universe’s past — while launching the students’ careers into the future.

For small steps. For big discoveries. BE BOUNDLESS.

Historians and activists who studied at the UW made HistoryLink.org into a community resource that has proven successful and popular over its 25 years.

By Shin Yu Pai

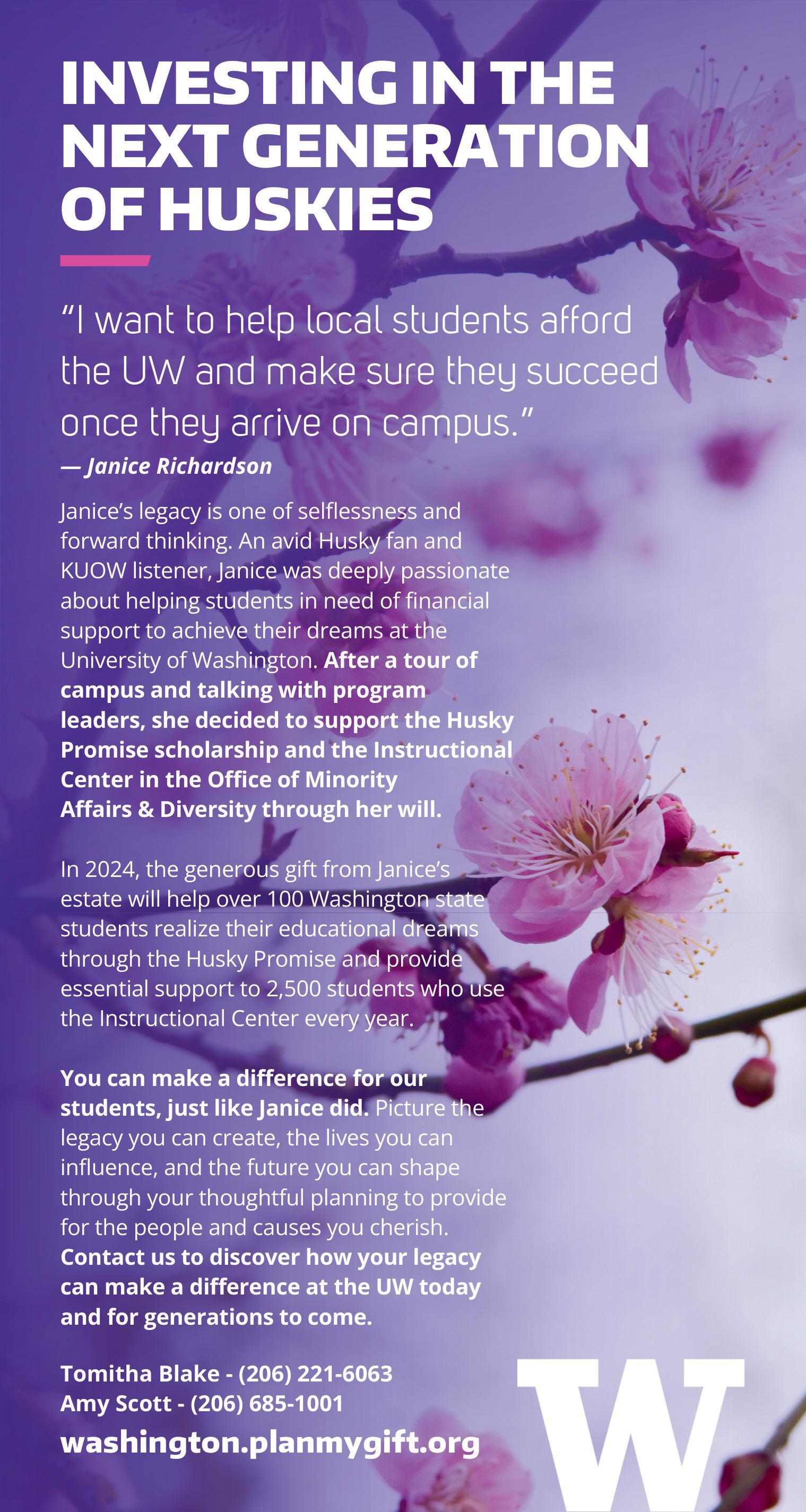

As another school year beckons, a bevy of longstanding businesses welcome alumni, friends and Husky fans back to the U District for fun and camaraderie.

Former American Library Association leader Tracie D. Hall brings her mission to overcome censorship and book banning to preserve our democracy to the UW.

startups and supporting spinoffs, the UW’s CoMotion innovation hub helps researchers and students along their

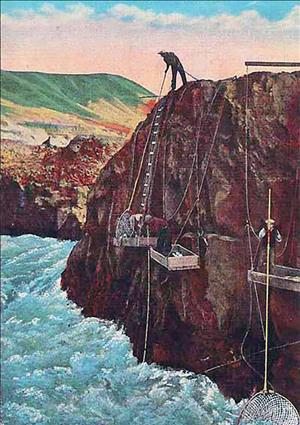

HistoryLink, an independent online encyclopedia with numerous UW ties, puts state history at our fingertips. In one entry, John Caldbic, ’76, describes Celilo Falls on the Columbia River, where, for more than 11,000 years, Indigenous people from at least 10 different tribes enjoyed an incredibly rich fishery. The spectacular falls were flooded in 1957 by The Dalles Dam.

uwmag.online

We’re captivated by the photography of Sung Park, ’01. Park explains how he got his start and what inspires his imagery. uwmag.online/park

HUSKY CREAMERIES

Summer is winding down, but ice cream is a year-round treat. We rounded up our favorite alumni-created ice cream shops around Seattle. uwmag.online/icecream

HEALTH HUB REBOOT

Husky Health Center (formerly Hall Health) honors its original namesake, a doctor and Olympic runner who established the first student health service on campus. uwmag.online/hall

It’s another happening summer night at one of the U District’s favorite and famous spots, the Neptune Theatre. Photo by Kris Ladera.

BY ANA MARI CAUCE

Just over 38 years ago, I arrived at the University of Washington in Seattle as a young assistant professor of psychology. I was deciding between multiple job offers, but I was irresistibly drawn to the UW, where the beautiful campus framing picture-perfect vistas of Mount Rainier complemented an academic culture grounded in service and collaboration. This was a place where great things were possible. Now, as I enter my last academic year as president, I am even more invigorated by the power of our community to create impact that betters the world.

This fall, we are welcoming students to campus, including around 11,500 who will

be starting their UW experience. Recently, especially during the past year, we’ve seen how deepening polarization and rising extremism in both our country and around the world can stymie our efforts toward making progress on the many problems confronting our society. We have both an opportunity and an obligation to equip students for lives and careers in which they can lead with empathy and collaborate across difference to achieve positive impact in their communities and in the world. That preparation must include providing them with the tools to engage in meaningful dialogue with those who hold

different perspectives, experiences and beliefs, which is a precondition for creating lasting change.

These essential life skills are not just a requirement for greater harmony, they are the bedrock of advancing learning, research, innovation and problem-solving. Universities serve as crucibles for ideas and discovery, an alchemy that is only possible in an environment where people are able to consider and evaluate different approaches, new evidence and competing narratives. This year, among other efforts to cultivate these abilities, Provost Tricia Serio is launching a campus-wide project to promote learning environments that encourage curiosity, critical thinking, active listening, productive dialogue and shared responsibility.

These same values and skills are also fundamental to our faculty and staff’s work to advance the public good through knowledge creation and service. As a convener across disciplines, organizations, sectors and communities, our mission depends on our ability to collaborate successfully with diverse stakeholders. Since the launch of our Population Health Initiative eight years ago, our strength in interdisciplinary collaboration has fueled projects ranging from supporting improved maternal health and alleviating childhood poverty to increasing knowledge and awareness of geographic health disparities. With the success of this interdisciplinary model as our guide, we are putting these same approaches to work in service of other large, complex challenges facing our world, including climate change and ethical computing.

These undertakings are ambitious and long-term, and they begin with a mindset that is open, curious and respectful of others’ talents and perspectives. Our students, faculty, staff, supporters and partners rely on the University of Washington to be a champion of intellectual inquiry and collaborative exploration in service of the public good. Our shared commitment to these ideals—the ideals that first brought me here decades ago—is the engine that drives the progress we will make together. As our alumni, you are a vital part of that engine for good, and I thank you for your continued engagement.

Ana Mari Cauce is the UW’s 33rd president. She has worked to expand access to higher education for Washington students and advanced interdisciplinary research to meet global challenges. This year will be her last as UW President.

MESSAGE FROM THE EDITOR

By Jon Marmor

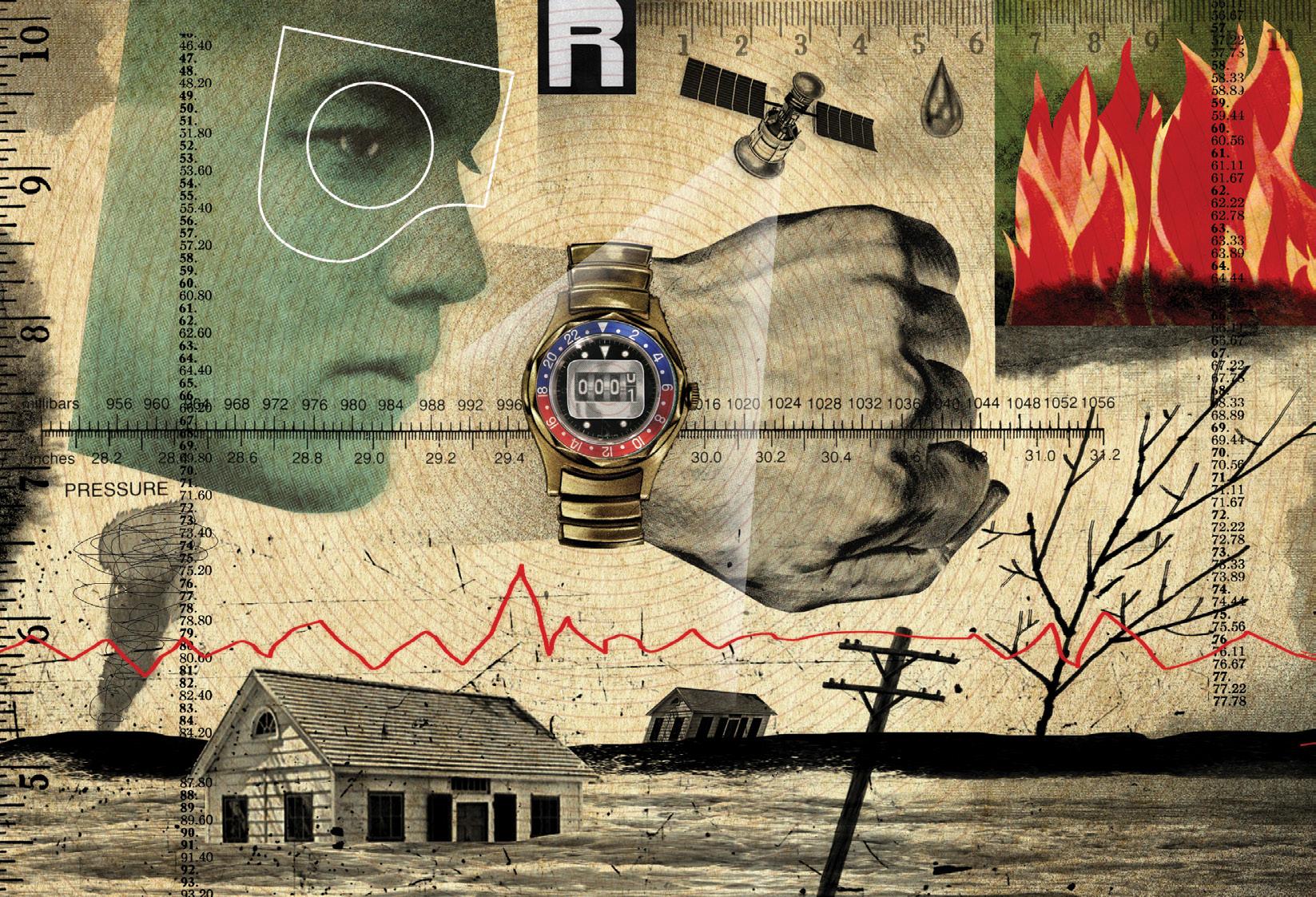

It seems that a day doesn’t go by without another natural disaster striking somewhere around the globe. It’s reassuring to know the University of Washington is a leader in efforts to learn all we can from these disasters: how communities handle them and what can be done to protect the public.

Thanks to $6 million in renewed funding from the National Science Foundation and an additional $1.5 million a year from the National Institutes of Health, the RAPID Facility—a first-of-its-kind center in the College of Engineering—provides natural hazard and disaster researchers with field instruments and other resources to study the effects of events such as wildfires, floods, hurricanes and earthquakes. The facility contains more than 100 unique instruments, including drones and a remote-controlled boat that uses sonar to scan underwater.

“Before RAPID, it was ad hoc, DIY or sometimes BYO [bring your own] equipment to a reconnaissance mission,” says facility director Joseph Wartman, a UW professor in civil and environmental engineering. “The few people who had reconnaissance instruments, such as lidar

(a laser-based sensing method), tended to be very overburdened. … They were asked to participate in numerous missions. It didn’t leave space and room for others to join.”

Officially known as the Natural Hazards Reconnaissance Facility, the RAPID facility is a collaboration among the UW, Oregon State University, Virginia Tech and the University of Florida. It opened its doors in 2018 and has transformed how data is gathered, processed and saved in the aftermath of disasters including the 2022 Skykomish wildfires, Hurricane Ian in 2022, and the 2021 Surfside condo collapse in Florida.

“We have everything we need to start making even more significant breakthroughs in years to come,” Wartman says. “I am very optimistic about what will come from the RAPID. Even in the first few months of the renewal [of the NSF grant], I’ve seen exciting uses of data and innovations in reconnaissance.”

With summer and fall bringing wildfire season to the state of Washington, it’s good to know we can count on the UW to help lead the way to keep us safe.

A publication of the UW Alumni Association and the University of Washington since 1908

PUBLISHER Paul Rucker, ’95, ’02

ASST. VICE PRESIDENT, UWAA MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS Terri Hiroshima

EDITOR Jon Marmor, ’94

MANAGING EDITOR Hannelore Sudermann, ’96

ART DIRECTION AND DESIGN Pentagram

DIGITAL EDITOR Caitlin Klask

STAFF WRITER Shin Yu Pai, ’09

CONTRIBUTING STAFF Karen Rippel Chilcote, Kerry MacDonald, ’04

UWAA BOARD OF TRUSTEES PUBLICATIONS

COMMITTEE CO-CHAIRS

Chair, Mark Ostersmith, ’90

Vice Chair, Roman Trujillo, ’95

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Lauren Kirschman, Kristin Baird Rattini, Mike Seely

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Satya Curcio, Matt Hagen, Kyle Johnson, Anil Kapahi, Kris Ladera, David Ryder, Raymond Smith, Mark Stone, Dennis Wise

CONTRIBUTING ILLUSTRATORS

Ewelina Karpowiak, Olivier Kugler, Ryan Melgar, David Plunkert, Anthony Russo

EDITORIAL OFFICES

Phone 206-543-0540

Email magazine@uw.edu Fax 206-685-0611

4333 Brooklyn Ave. N.E. UW Tower 01, Box 359559 Seattle, WA 98195-9559

ADVERTISING

SagaCity Media, Inc. 1416 NW 46th Street, Suite 105, PMB 136, Seattle, WA 98107

Megan Holcombe mholcombe@sagacitymedia.com, 703-638-9704

Carol Cummins

ccummins@sagacitymedia.com, 206-454-3058

Robert Page

rpage@sagacitymedia.com, 206-979-5821

University of Washington Magazine is published quarterly by the UW Alumni Association and UW for graduates and friends of the UW (ISSN 1047-8604; Canadian Publication Agreement #40845662). Opinions expressed are those of the signed contributors or the editors and do not necessarily represent the UW’s official position. �his magazine does not endorse, directly or by implication, any products or services advertised except those sponsored directly by the UWAA. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Station A, PO Box 54, Windsor, ON N9A 6J5 CANADA.

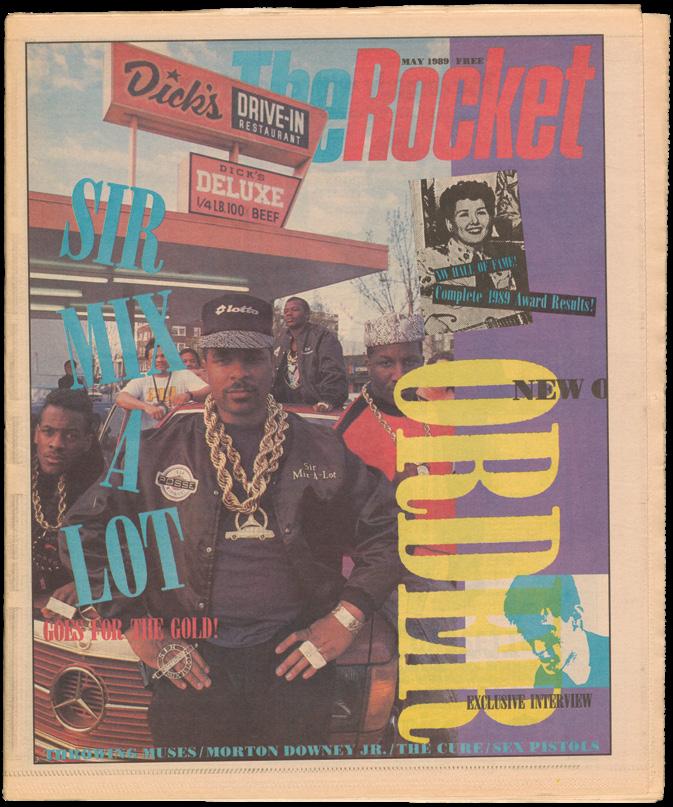

My name is Andrew L. Magee (originally class of ’84, graduated much later). In reading your article about The Rocket, I remember how I had a drum set (made by Sonor) years ago when I was still in high school. Around 1979, I advertised selling it, including the cymbals. I placed a want ad in the paper, and two guys called to come over and look at the cymbals, as I remember it. They drove a VW microbus. I noticed in the back of the VW they had a bunch of bundled newspapers, and I asked them about it. They said they were starting a magazine called The Rocket! I offered to take some of the bundles off their hands, so I could place them in the Bellevue DECA student store, and they were happy to oblige. As the years passed, and The Rocket began to thrive, I would always tell people that I was Bellevue’s first distributor of The Rocket. I wonder where these guys (and my cymbals, for that matter) went?

with a cover photo! It also deprives alumni of a cover worth beholding.

Antoinette Grosso Ziegler, ’65, Torrance, California

It was fun seeing a picture of my former high school chemistry teacher Linda Edgar (“Going the Distance,” Summer 2024). I remember bumping into her sometime around 1990 while walking on campus between classes and asking, “Mrs. Edgar? What are you doing here?” She told me she was going back to school to become a dentist, and I told her that I was studying civil engineering. Congratulations to Dr. Edgar! Linda Glas (Kask), ’92, Seattle

Andrew L. Magee, ’94, Mercer Island

What a treat to see the cover photos and relive memories of reading The Rocket, putting on my flannel shirt, dark lipstick and Doc Martens, and picking places to join the collective catharsis of grunge. I’m glad the issues are being digitally archived. Miriam Gonzalez-White, ’00, San Francisco

It was thrilling to see the photographs taken by Art Wolfe in the Summer 2024 edition of University of Washington Magazine. So I turned back to the magazine’s cover expecting it to feature another of Wolfe’s photos, but no… it was some silly photo having to do with the grunge era. What a shame not to honor Wolfe, this year’s Alumnus Summa Laude Dignatus,

I applaud the article “Dose of Advice for Weary Parents” advising parents to steer clear of melatonin. When discussing “sleep hygiene,” it is elementary to state the obvious detractors of sleep such as screen time and irregular sleep patterns. It would be remiss to not mention prescription medications given to children to “help them focus and calm them down.” These medications start the vicious cycle of sleepless and restless nights that require so-called sleep aids. Perhaps our job, as parents, is not to overthink or take blame for our children’s sleep issues. Enough time exercising, eating healthy diets and outdoor activity will inevitably cause the physical body to sleep. And if there are periods in their lives where this is not working, so be it. Most likely this is the time their psyche is overcoming their physique and trying to work something out. We need to let this happen; good mental hygiene may require periods of sleeplessness. Providing the comforts of a quiet environment and firm bedtime without negotiations sounds simple, but it does take effort.

Dr. Jennifer M. Hein, ’87, Geneva, Illinois

After reading the article (“Educational Opportunities for All,” Summer 2024) about Emily Yim, the president and CEO of the Washington Alliance for Better Schools, I felt compelled to promote broader support to improve global education. The Reinforcing Education Accountability in Development Act has served more than 122 million students worldwide by partnering with programs that improve education in low-income countries, strengthen education systems, achieve literary milestones and promote education as the foundation for sustained economic growth.

Hailey Alt, ’22, Sammamish

ART + ART HISTORY + DESIGN DANCE DRAMA DXARTS MUSIC BURKE MUSEUM HENRY ART GALLERY JACOB LAWRENCE GALLERY MEANY CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS

From musical performances to theatrical productions, natural history to interactive art exhibits, there's something for everyone.

UW Medicine opens a new center for behavioral health care and for training the next generation of mental health professionals

By Caitlin Klask

Washington residents might be frustrated with the scarcity of mental and behavioral health care in the state. Only 12% of us live somewhere we can expect our psychiatric needs to be met, and 41% of Washington’s counties don’t have a single practicing psychiatrist.

After years of advocating, planning and building, and a $244 million investment from the state, UW Medicine has opened the Center for Behavioral Health and Learning, an expansion of existing services on UW Medical Center’s Northwest campus. “This is something we can be proud of ... having the first behavioral-health teaching facility built from scratch in the Evergreen State,” says Gov. Jay Inslee, ’73, who had proposed the hospital in 2018 as part of a plan to transform Washington’s behavioral-health system.

There are just over 1,000 psychiatric hospital beds in Washington. The CBHL adds 150 more. Of those, half are designated for

patients on long-term, civil commitment status, involuntarily admitted by courts for treatment of serious and persistent mental health problems that make it impossible for them to safely live in the community.

The rooms serving patients on civil commitment status feature hallways with clear sightlines and windows that provide natural daylight and display the towering trees of the UWMC Northwest campus. Patients stay here for 90 to 180 days, “so we designed it with elements any of us would look for if we were trying to find an apartment, for example” says Dr. Ryan Kimmel, ’97, ’01, chief of psychiatry for UW Medical Center, who helped design the building. Attendees of the grand opening this spring toured private bedrooms, peaceful common areas with floor-to-ceiling photographs featuring Washington landscapes and balconies that provide fresh air.

Another 50 beds on two floors serve patients who have both psychiatric and

medical/surgical needs. “A lot of people have significant medical issues and significant behavioral health issues, and the two often make each other worse,” says Kimmel. “If we have a [psychiatry] patient with chest pain, they can remain hospitalized here and continue to see the behavioral health providers they already know.” Finally, the 25-bed geropsychiatry unit provides unique services to older patients with neurodegenerative, cognitive and mental impairments.

The CBHL also houses the Garvey Institute Center for Neuromodulation, a state-of-the-art program that offers treatments like transcranial magnetic stimulation, electroconvulsive therapy and other novel therapeutics. Neuromodulation treatments can improve recovery for a variety of conditions including major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. The new center also creates opportunities for trainees to learn the latest in neuromodulation and for clinician scientists to explore novel therapeutic approaches in interventional psychiatry. In addition to providing life-saving care, UW Medicine, which has the largest psychiatry residency in the nation, is training the next generation of health care professionals in collaborative, team-based mental health care. Recent innovations include involving families and caregivers as members of the care team. The facility also houses programs to address burnout in the workforce and a telepsychiatry consultation program to assist rural and overburdened providers statewide with caring for people with complex mental health and addiction problems.

“Any provider, whether they’re a prescriber, nurse or social worker, can call our psychiatry consultation line and talk to a UW faculty psychiatrist,” says Kimmel. “It enables providers to better treat what’s in front of them when there are no available specialists in their community.”

Systemic issues don’t end after behavioral health patients find care. “For too many of our neighbors, emergency visits to a hospital are followed by discharges to the street,” says state representative Frank Chopp, who sponsored the house bill establishing the CBHL. For some patients, the availability of longer-term treatment will help with a more complete recovery. For others, training of family and caregivers and involvement of peer bridgers and other resources could help with a successful transition into the community.

Taking inspiration from Depression-era muralists who incorporated scientific advancements into their works, Laura Brodax, ’76, combines elements of local history, natural surroundings and urban landscapes in her public art commission, “A Parable for Redmond.” Installed at the entryway of the new Redmond Senior & Community Center, the artist’s tile mural is one of four new city-commissioned artworks that were revealed to the public on May 3. Binary code seems to fall from the sky while circuit-board paths rise up from the ground like cattails. The technological elements are embedded within a natural landscape that includes native birds and the Sammamish River.

The HUB has hosted concerts with popular acts like Tina Turner, Thomas Dolby, Modern English and The Ramones. This year, students gathered on the HUB lawn, right, for the Spring Show, which was headlined by AG Club.

By Shin Yu Pai

The Husky Union Building has been the core of campus life since 1949. It has been the seat of student government, the host of concerts and makers fairs, a spot for student activism and the location of many a budding campus romance. Former Regent Bill Gates Sr., ’50, spent more time in the HUB than he did in the law school—in pursuit of his future wife, Mary, ’50. And Micki Flowers, ’73, still shares the details of her first date with former basketball star Bob Flowers, ’65, ’68. They went to the HUB for a jazz concert, and she tripped and fell climbing up a flight of stairs. “He picked me up and dusted me off,” she says. The rest is history.

Students in 1919 were the first to dream of a union building, but the project was delayed by the first Husky Stadium and then World War II. The plan to build “a gathering place for students” was revived in the early 1940s, according to a 70-yearold article in The Seattle Daily Times. Work began in April 1948.

On Oct. 25, 1949, student president Phil Palmer, ’54, cut a purple-and-gold ribbon held by UW President Raymond Allen and UW Alumni Association President William

Ferguson, before leading a procession of students and faculty into the new $1.3 million facility. The first phase of the three-story structure included an auditorium, restaurants, retail space and a hair salon. It also had lounges and a bowling alley. To meet evolving student needs, the Husky Union Building has been updated and expanded over its many decades.

“The HUB has been the ‘living room’ of campus, that home away from home where students and the community can gather, play, connect and grow,” says Carrie Moore, the executive director. “Because of this rich history, the HUB isn’t just a place, it’s a feeling. The people who work at the HUB are the stewards of this amazing legacy and pour their hearts and souls into this special place, creating … that sense of belonging for everyone.”

In its first three years, the HUB doubled its space. The University Book Store moved in in 1953. A coffee shop was added in the 1960s, alongside a cafeteria, billiards room and auditorium. The 1970s saw a remodel of the food-service area and the buildout of a “shell” for the East Ballroom. In the 1980s, the HUB became home to several

ASUW groups, including the Black Student Commission, American Indian Student Commission, the Asian Student Commission and La Raza (formerly MEChA). In the early 2000s, the Husky Den was remodeled into a food court and Rainy Dawg Radio debuted in the sub-basement. The UW Board of Regents approved the HUB’s most recent renovation in 2009. It took three years to complete.

“Looking back over 75 years, we feel a strong connection to the past as we look to the future,” says Moore. “As student needs and wants change, so will the HUB. We engage daily with students, staff, faculty and the community to help us shape that future, to help determine what the HUB will be for the next generation of UW students.”

Partnering with national academic and athletic powerhouses brings tremendous advantages for the UW

By Jon Marmor

September is always an exciting time at the University of Washington. Husky Football gets underway and fall classes are about to start. This year, however, a different kind of excitement is in the air.

The UW is a new member of the Big Ten Conference, meaning the UW and Husky Athletics is now part of a league of nationally renowned heavyweights in both academics and athletics.

When the UW joined the Big Ten Conference, the well-known ‘Maps’ commercial created by the creative studio Carbon was playfully updated to include UW landmarks and elements of the Northwest landscape. Find the new commercial here: uwmag. online/bigten.

A few things aren’t changing. The Huskies will maintain their long-standing West Coast rivalries with Oregon, UCLA and USC, who also joined the Big Ten.

The most talked-about benefit of this new configuration is how Husky Athletics needs more sustainable financial support (via the Big Ten’s TV contracts) to remain a powerhouse in the evolving world of college sports. What isn’t nearly as well-known is how joining the Big Ten opens doors on many academic fronts to create new partnerships and collaborations with such prominent universities as Michigan, Ohio State, Penn State and others in the Big Ten Academic Alliance.

“There are tremendous opportunities for us, and I was struck how excited the deans were about [joining the Big Ten],” UW Provost Tricia Serio says.

Those opportunities are eye-opening and far-ranging. For instance, the Big Ten

In the big picture, Serio says, the UW has joined its peers when it comes to graduation rates, referring to the Big Ten’s 84% graduation rate—20 points above the national average. “We share the same level of prestige, opportunities and priorities, so we are really aligned with a group of peers,” Serio says. “The Big Ten is the national model.” Rickey Hall, the UW’s vice president for minority affairs and diversity and University diversity officer, says all 18 institutions’ senior diversity officers already meet regularly to network and discuss vital issues.

While most of the publicity around finalizing the UW’s move to the Big Ten has been about athletics’ need to secure better financial footing, Kim Durand, deputy athletic director of student services and senior woman administrator, says that was not the only reason for joining the Big Ten. The ability to collaborate with the 17 other institutions on matters related to athletics and student issues will be a particularly huge benefit as the college sports world continues to deal with major challenges.

“It makes even more sense beyond athletics,” she says. “It’s the premier academic conference outside of the Ivy League.”

has a series of leadership development programs for deans, faculty and chairs. There’s a consortium of global affairs programs at the 18 Big Ten schools, and long-running programs where provosts, leaders from engineering and arts and sciences and student services get together to discuss the challenges and opportunities in their fields. Moreover, there’s an alliance of the universities’ library programs, which will provide an incredible array of advantages to students, faculty, staff and alumni. The Big Ten libraries hold 145 million volumes and 25% of all print titles in North America. That means more access to scholarly research materials and big discounts when it comes to subscribing to scientific journals, a major concern for universities nationwide.

Another benefit is in joining the Big Ten Cancer Research Consortium. “In cancer research, participation in collaborative efforts really means more opportunities,” says Evan Yu, medical oncologist at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center and professor in the UW School of Medicine’s Division of Hematology and Oncology. “It provides connections to others who are working on cancer discoveries and more exposure to emerging research and clinical trials, all of which can spark breakthroughs. It also provides investigators with opportunities for additional mentorship.”

On Aug. 2, the day the Huskies officially joined the Big Ten, UW Athletic Director Pat Chun said it was “a momentous day. … We’re honored to be a part of the Big Ten Conference. I tell people when you walk around our campus, we are a Big Ten school, this is where we are supposed to be, and we feel we can impact our young people the best by putting them on the biggest stage possible.”

Fans and supporters of the UW are just as excited about this new era for the Huskies. Dow Constantine, ’85, ’89, ’92, has attended every UW home football game since Nov. 7, 1969. In a recent Seattle Times op-ed, he wrote, “It was undoubtedly the right move for securing the future of Husky Athletics. And our affiliation with the Big Ten has a long and rich history born of years of tough competition across all sports. … Additionally, the conference shares our commitment to academic excellence and groundbreaking research.”

UW President Ana Mari Cauce is thrilled about the new era. “We are committed to developing student-athletes who thrive not only in competition on the field, but in the classroom and throughout their lives, and our new conference shares those values. This change has opened up opportunities not only for our students, but for our whole University to forge new partnerships and collaborations with many of the nation’s other leading research universities.”

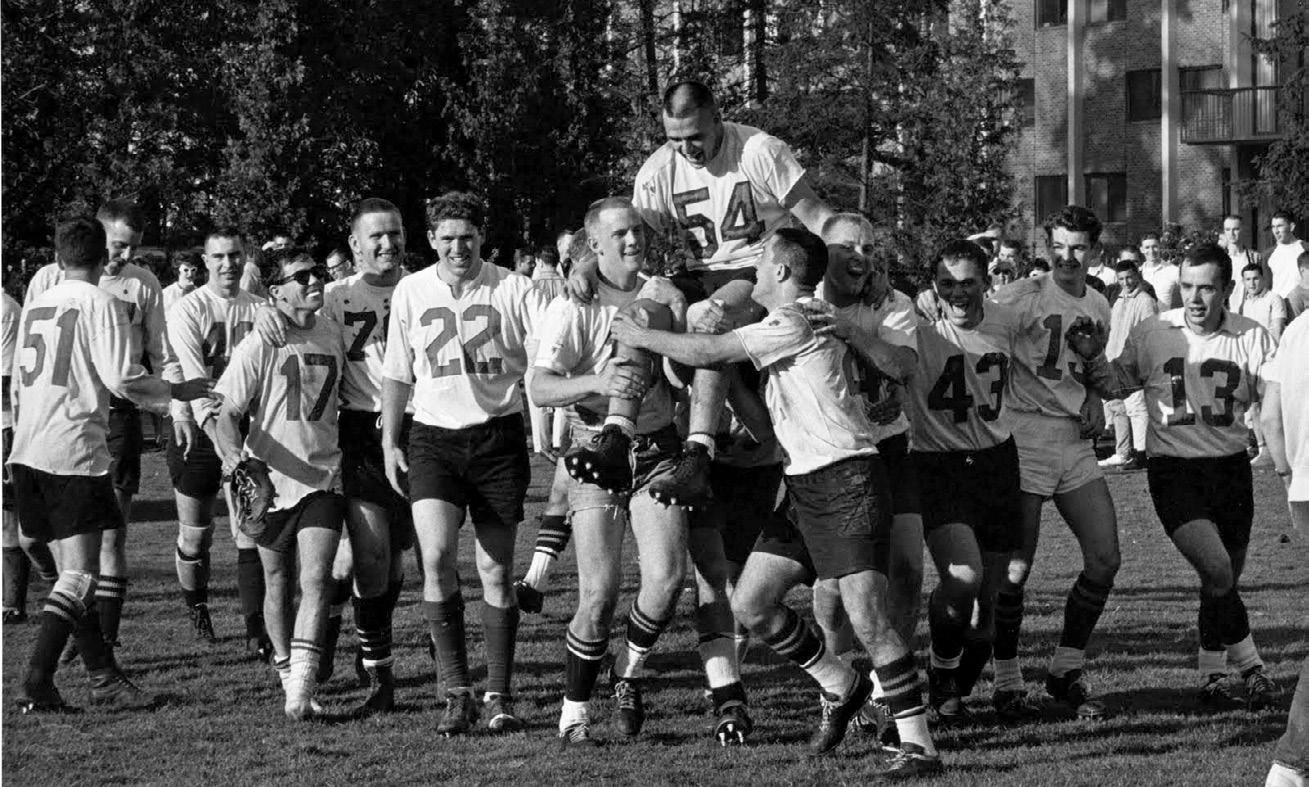

UW’s 60-year-old rugby club is poised for brighter days, thanks to the support of its alumni

By Mike Seely

After thriving as a running back on his high school football team in the Bay Area, Brian Cain Jr. had designs on walking on at the University of Washington. He had an in with one of former head coach Jimmy Lake’s assistants, but when Coach Lake was shown the door, that evaporated.

So Cain tried his hand at rugby and fell in love with “the intricacies of it,” says the senior-to-be, a political science and economics major who is now co-captain of the UW’s rugby team.

Cain was following the same path to the sport that Chris Majer took when he enrolled at the UW in the fall 1969.

“I was a marginal high school football player, walked on with the Huskies,” recalls Majer. “That lasted about two hours. I had some issues with authority, and this

was still Jim Owens football. A guy in my fraternity house started telling me about this sport [rugby] I’d never heard of. He took me out to a practice and I fell in love with it, and four years later I was captain of the team.”

UW’s team got its start as a club sport in 1963. It’s still a club sport, with the Huskies competing against the likes of Oregon, Washington State, Oregon State, Boise

Founded in 1963, the UW Rugby club is the oldest club on campus. The Huskies, who play in the Northwest Collegiate Rugby Conference, won Northwest titles in 1996, 2002, 2004 and 2005 and the 2014 D1AA Varsity Cup.

State and Western Washington in the Northwest Collegiate Rugby Conference.

“It’s gone through peaks and valleys,” says Majer, ’73, ’78. “To be blunt about it, moving out of a bit of a valley right now.”

Yet based on an encouraging mid-June event at the IMA facilities, the club might be poised to reach new heights.

For more about rugby at the UW, visit uwmag.online/rugby.

UW researchers note that music enhances the neural response to speech in infants. They also discover that families are not talking or singing directly to their children as much as as they thought.

By Lauren Kirschman

While past research has shown that speech plays a critical role in children’s language development, less is known about the music that infants hear—and the role it plays in their brain development.

A new University of Washington study compares the amount of music and the amount of speech that children hear in infancy. Results showed that infants hear more spoken language than music, with the gap widening as the babies get older.

“We wanted to get a snapshot of what’s happening in infants’ home environments,” says Christina Zhao, ’15, an assistant research professor in the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences. “Quite a few studies have looked at how many words babies hear at home, and they’ve shown that it’s the amount of infant-directed speech that’s important in language development.

We realized we don’t know anything about what type of music babies are hearing, and how it compares to speech.”

Researchers analyzed data from daylong audio recordings collected in Englishlearning infants’ home environments at ages 6, 10, 14, 18 and 24 months. At every age, infants were exposed to more music from an electronic device than from an in-person source. This pattern was reversed for speech. While the percentage of speech intended for infants significantly increased with time, it stayed constant for music.

“We’re shocked at how little music is in these recordings,” says Zhao, who directs the Lab for Early Auditory Perception (LEAP), which is housed in the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences (I-LABS).

streaming in the background or on the radio in the car. A lot of it is just ambient.”

This is a departure from the highly engaging, multisensory, movement-oriented music exposure that Zhao and her team had been studying in the lab. During these sessions, infants were given instruments and caregivers synchronized the babies’ movements to music. A control group of babies simply played.

‘We’re shocked at how little music is in these recordings.’

“We did that twice,” Zhao says. “Both times, we saw the same result: that music intervention was enhancing infants’ neural responses to speech sounds. That got us thinking about what would happen in the real world. This study is the first step into that bigger question.”

Past studies have largely relied on parental reports to examine musical input in infants’ environments, but parents tend to overestimate the amount they talk or sing to their children. This study closes the gap by analyzing daylong auditory recordings. The recordings, originally created for a separate study, documented infants’ natural sound environment for up to 16 hours per day for two days at each age.

Researchers then crowdsourced the process of annotating the recording data through Zooniverse, a citizen-science web portal. When volunteers identified speech or music, they noted whether it came from a live person or an electronic source. Finally, they judged whether the speech or music was intended for a baby.

The researchers will expand their study to see if the results can be generalized to different cultures and populations. They also want to explore when music moments happen in infants’ lives. “We’re curious to see whether music input is correlated with any developmental milestones later on for these babies,” Zhao says. “We know speech input is highly correlated with later language skills. In our data, we see that speech and music input are not correlated—so it’s not like a family who tends to talk more will also have more music. We’re trying to see if music contributes more independently to certain aspects of development.”

The study was published in the journal Developmental Science.

Layer on your Purple Pride with necklaces, bracelets and earrings from Kyle Cavan, a women-owned company. Inspired by iconic University of Washington symbols and campus architecture, these signature pieces are designed to evoke your favorite Husky memories. Explore the new UW collection at kylecavan.com

I NNOVATING THE PAST WITH BY

SHIN YU PAI

Did you hear about the Seattle Police officer who became one of the biggest bootleggers on the West Coast? Maybe you’re wondering about the strange spectacle of bear wrestling and how it played out in places like Longview and Walla Walla. Flying saucers in Washington?

You can learn about all that and more at HistoryLink, the independent online encyclopedia of Washington state’s history. With well over 8,000 original articles, it averages more than 4,500 visitors a day. Feature pieces, interactive tours and photographs highlight history from every corner of our state.

The nonprofit resource turned 25 in February and, in a world where universities are concerned about the very future of a history major, the success and popularity of HistoryLink proves there is an enduring public fascination with the past.

In 1997, Walt Crowley and wife Marie McCaffrey, historians and activists who studied at the UW in the 1960s, dreamed up the project. Crowley wanted to create an encyclopedia of Seattle and King County history; McCaffrey thought it should go online. With fellow non-academic historian Paul Dorpat, they started researching and assembling their content.

“From the beginning, there was always this civic idea at the core of HistoryLink,” says McCaffrey. “Knowing the history of the place where you live makes your life richer. But it also helps you to make better decisions as a participant in democracy.” In the spirit of enriching lives and engaging people in their community, McCaffrey and Crowley launched their digital encyclopedia, providing well-researched historical context and hoping to open minds and shift opinions. When Crowley died in 2007, HistoryLink had amassed more than 4,400 articles and become an inspiration for communities around the country. With McCaffrey as executive director, HistoryLink grew in financial stability, expanded its coverage of the state, published books and hosted events. McCaffrey transitioned out of leading HistoryLink in late 2023 and the organization is now stewarded by Jennifer Ott, ’93, an author, historian and occasional Seattle waterfront tour guide.

Ott was handpicked and closely mentored by McCaffrey over six years in preparation for taking the reins of the organization.

‘Knowi ng th e h istory of the place wh ere you live makes your l i fe r icher.’

Her first contribution to HistoryLink, in 2000, was an article on salmon stories from Indigenous communities in Western Washington. She became a regular freelance contributor to the site and eventually took on managing projects. Later, she stepped in as assistant director. One of Ott’s efforts is developing tribal histories through deepening long-term relationships with local tribal historians. She worked with staff of the Snoqualmie and Muckleshoot tribes to write histories related to local watersheds as a way to understand both place and space. “Many of our Indigenous communities haven’t been well incorporated into historical narratives. Or they’ve been harmed by historians,” says Ott. “If there’s been harm, you have to build the relationships.”

As an undergrad in the UW’s Comparative History of Ideas program, Ott studied with renowned environmental historian Richard White, ’72, and studied European history with John Toews. Her adviser encouraged her to pursue a double major. “Instead of just hoovering up information, I got to think about where the information was coming from. Who wrote it,” she says.

Ott completed her master’s in environmental and Western American history at the University of Montana. In 2009, she joined a HistoryLink book project focusing on the famed New York-based Olmsted Brothers firm and its early 1900s designs for Seattle landscapes, including the UW’s main campus. “Landscape design is an essential component of a healthy community,” Ott says. “Landscape architects have the vision to know what people will see, what impact that can have. I could never afford a house with a view of Mount Rainier. But I went to a university where I could see that gorgeous mountain framed by evergreens.”

As HistoryLink steps into a new era, Ott is eager to create resources for students and teachers, directing them toward Washington state history curriculum and archival resources. In response to conversations with the Washington State Talking Book and Braille Library, she plans to develop audio formats so users can listen to articles. The organization also hopes to amplify the work of smaller community-based historical societies and museums around the state by preserving and archiving their exhibits at the HistoryLink website. The digital format would allow those community history exhibits to endure. This fall, HistoryLink will partner with the Digital Public Library of America and the Washington State Library to include HistoryLink stories in their databases.

Thanks to careful research, quality writing and a thoughtful approach to a diversity of subjects, HistoryLink is a reliable resource for scholars, teachers and anyone else seeking to know more of the region’s story. “HistoryLink has been an important part of my career for a very long time,” says Associate Professor Joshua Reid, director of the UW Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. “The articles, historical photos and other resources it makes available are highly useful in the classroom. They’re a great place for students to get some relevant background on potential research topics. I especially appreciate the detailed citations and notes for the articles.”

Writer and founding editor Priscilla Long, ’90, developed a compilation of HistoryLink’s stories that gathered many voices and histories to provide a broader understanding of Washington history. “We see ourselves as translators between the academic and the cultural-resources folks who document historic sites for the government,” says Ott. Few people will pick up an EPA report, she says, but HistoryLink can be an intermediary for the general public. “We want history to be used by those who are making decisions or developing their understanding of place.”

History Professor Emeritus John Findlay says HistoryLink’s founders and staff have been “very skillful at innovating and occupying their own niche. … But in contrast to writings by academic scholars, HistoryLink has proven much more accessible.”

The organization has reached out to journalists and many scholars, including historians at the UW, to grow a stable of writers who produce high-quality work. They include David Wilma, ’71, who worked as a UW police officer while he pursued his history degree. He served as staff historian for HistoryLink and has written more than 125 features on subjects including early white settlement, hydroelectric development and many of the luminaries who shaped the region. Peter Blecha, a UW student in the 1970s, spotlighted the region’s entertainment history—from bear wrestling to grunge bands. Zola Mumford, who completed her Master of Library Science degree in 2009, crafted a history of the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Center. Last year, Emilie Miller, who earned a UW museology/museum studies certificate in 2020 and now is senior curator at Hibulb Cultural Center, featured the Tulalip Boarding School, an effort to distance Indigenous children from their culture. In one of her feature stories on the site, Tamiko Nimura, ’00, ’04, conjured up Tacoma’s once-vibrant Japantown. HistoryLink’s recent Future of History fundraising campaign will ensure that even more geographically diverse stories about Washington state are featured in the next evolution of the online encyclopedia. Looking ahead, Ott says, “We’ll have the bandwidth to go farther afield from the Seattle and King County regions to explore more deeply Eastern Washington and beyond.”

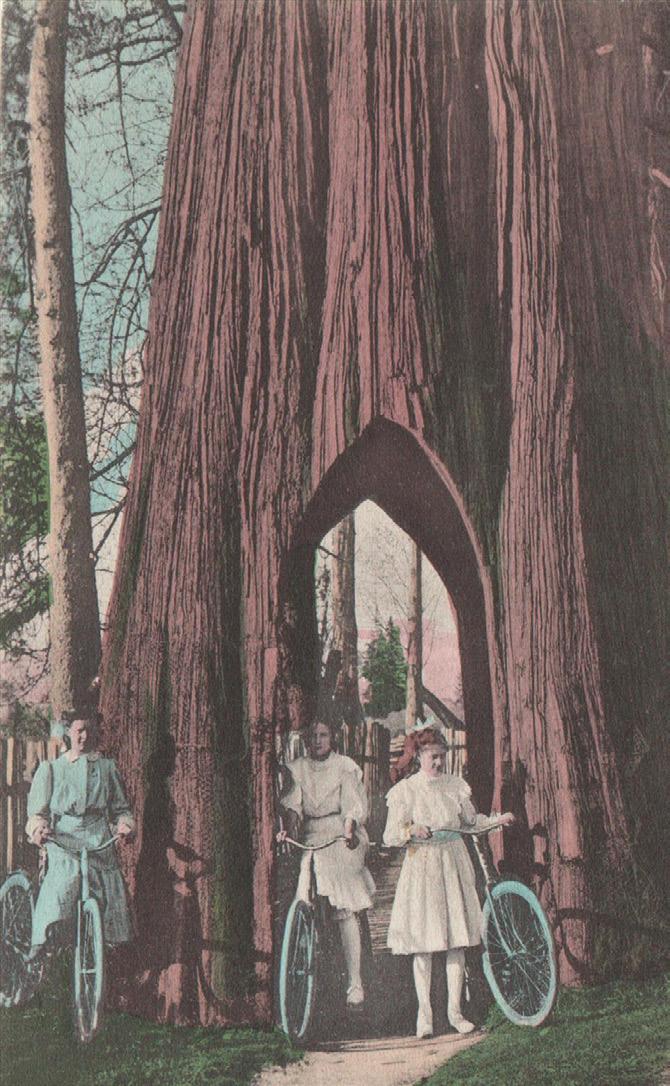

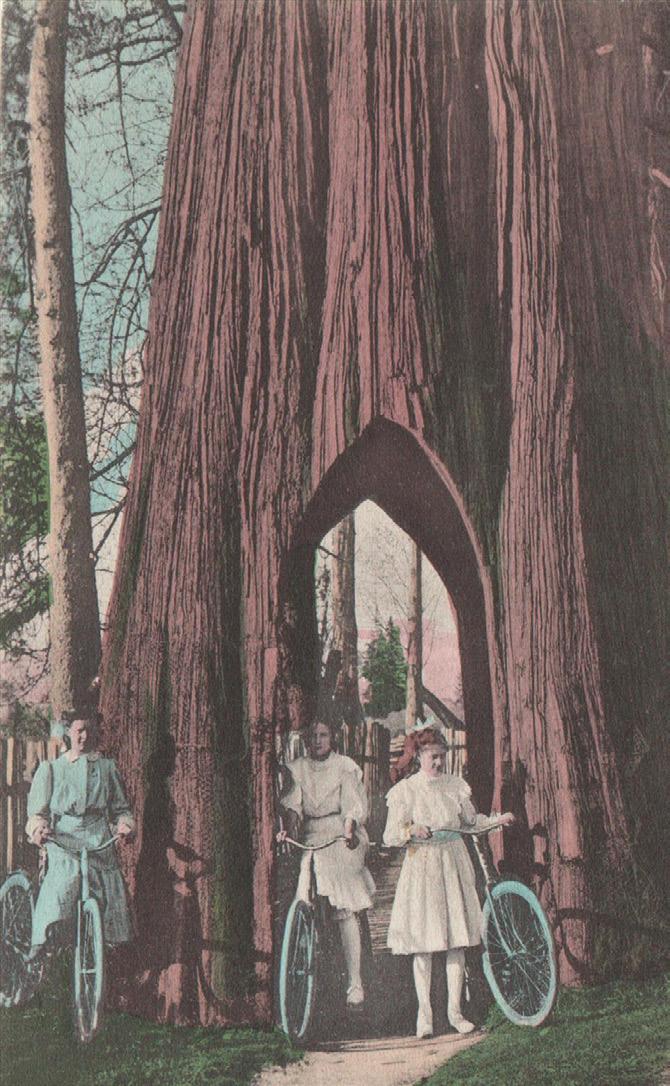

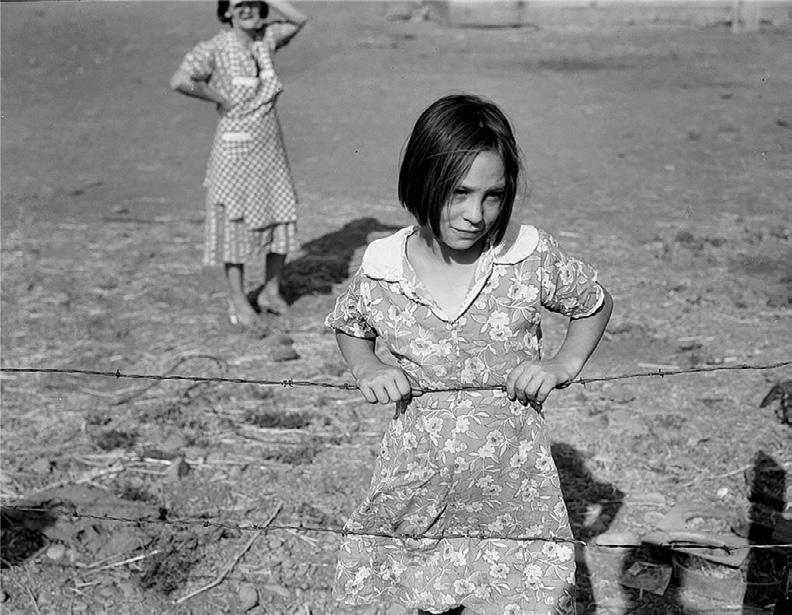

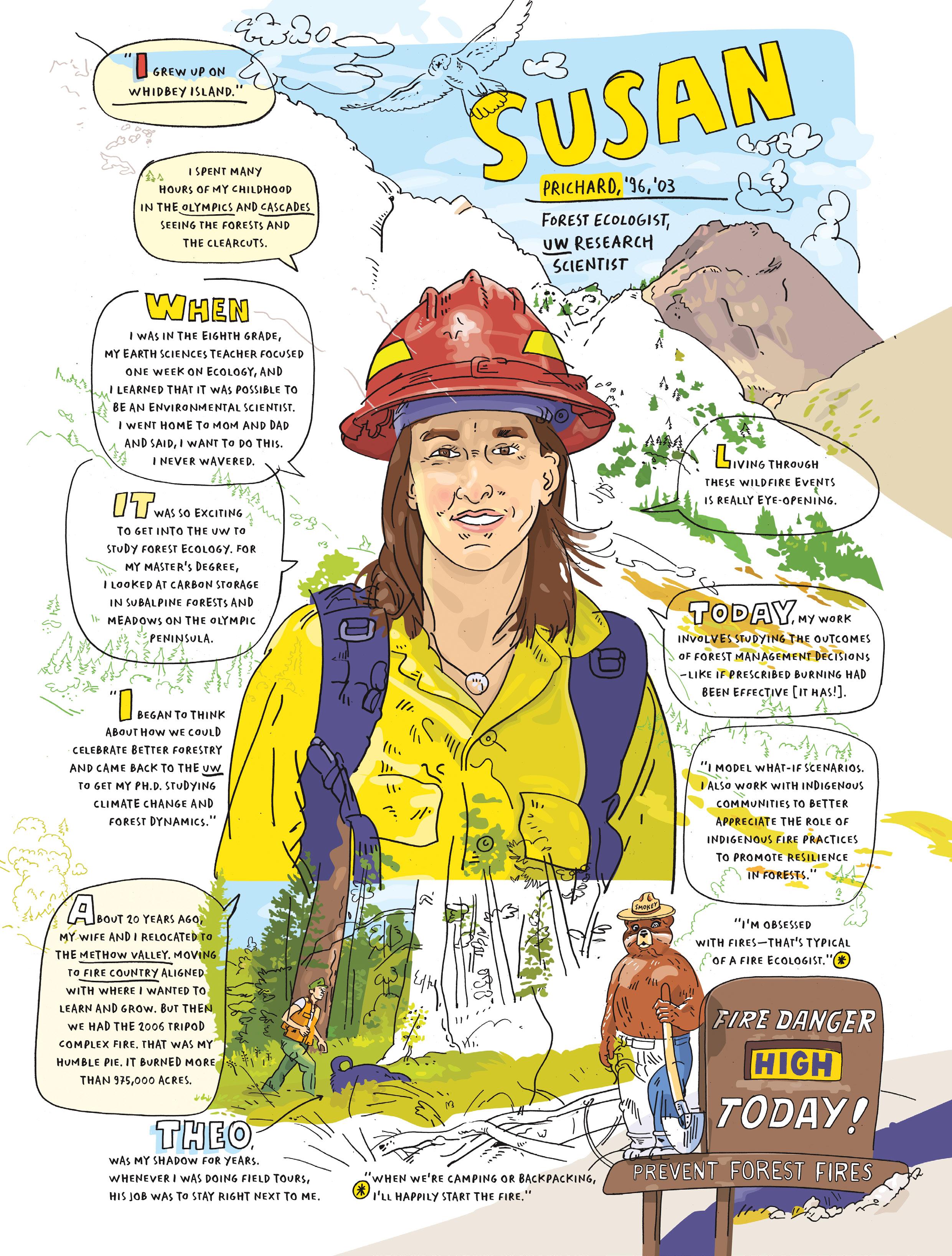

HistoryLink covers a breadth of Washington topics including culture, events and public works. Previous page, Clallam County loggers in 1909 (Asahel Curtis, Washington State Historical Society). Clockwise from bottom left, Lloyd Anderson, ’26, co-founder of REI (MOHAI), Edythe Turnham and Her Knights of Syncopation (Black Heritage Society of Washington State), The Diablo Dam Incline (Seattle Municipal Archives), The Bicycle Tree in Snohomish (courtesy Peter Blecha), Tulalip Indian School women’s basketball (UW Special Collections), Pike Place Market (HistoryLink), Child and Her Mother, Wapato, Yakima Valley (Dorothea Lange/ Library of Congress).

Clockwise from above, the 1916 Montlake Cut cofferdam burst (MOHAI). Native Americans fishing in the Columbia River at Celilo Falls ca. 1935 (HistoryLink), Thelma DeWitty, the first African American teacher in Seattle Public Schools (UW Special Collections). Center, the ruins of the Occidental Hotel after the Great Seattle Fire in 1889 (Seattle Public Library). For more about these photographs, visit magazine.uw.edu.

en gonyer is seattle to the core. She grew up in Southwest Seattle’s Arbor Heights neighborhood. Because public-school busing started when she was in elementary school, she was exposed to a wide swath of the city before that great social and educational experiment came to an end—and before traffic in the area became unbearable.

At about age 16, she began hanging out on University Way Northeast, aka the Ave. But Gonyer, who earned her associate’s degree from North Seattle College and her bachelor’s from Seattle University, wouldn’t attend the University of Washington until graduate school, where she studied medieval literature.

That’s not to say Gonyer shied away from the University District during her undergrad years. One of her favorite haunts was the College Inn Pub, a dungeon-like (in a good way!), subterranean watering hole that functions as the South Pole of the Ave’s business district.

“My husband and I have a history with the pub that goes back 30 years. My husband used to work at the Last Exit,” says Gonyer, referring to the late, great Brooklyn Avenue coffeehouse. “He was there in the late ’80s, and that’s when he started going to the pub. Everyone at the Last Exit went to the pub. It was a very symbiotic relationship.”

Gonyer first patronized the College Inn in 1992, and then she worked there in 1997 and 1998 before starting grad school in 1999. She continued to visit the pub until 2020, when she and her husband, Al Donohue, became its owners after the bar’s former proprietors abruptly shuttered the space after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Donohue and Gonyer weren’t the only ones in terested in picking up where the College Inn’s previous owners had left off, but they likely got the nod from the building’s landlord because, as Gonyer assumes, “Al and I were very adamant that we didn’t want to change anything.”

The pub—there’s a College Inn Hotel upstairs owned by someone else—is a 21-and-over establishment, so Gonyer is grateful to have another pair of “Ave Classics,” Big Time Brewery & Alehouse and Shultzy’s Bar & Grill, right up the street. Both places have more sophisticated kitchens and allow minors on their restaurant sides, so staffers at the College Inn direct families there should they descend the stairs unawares.

“We tend to think of Big Time and Shultzy’s as the other two points of a triangle with the pub,” says Gonyer. “We do really like having Big Time and Shultzy’s there. We share a lot of the same clientele. Shultzy’s and Big Time have some things that we don’t have.”

And then there’s Earl’s On The Ave, another neighborhood survivor that often sponges up a rambunctious undergrad crowd, allowing its neighbors to sustain a more relaxed vibe.

“Earl’s is an important creature in the ecosystem of the Ave,” says Gonyer. “Those who want to go wild and party and have a crazy good time, they go to Earl’s.”

Subtle fixes were a must, however, and the couple and their business partners had an entire year to whip the space into shape, seeing as how the UW moved its classes online during the 2020-2021 school year.

“The U District was a ghost town,” she recalls. “There were literally tumbleweeds coming down the Ave. So we just spent all that time doing deferred maintenance that people can’t see.”

The pub, which dates to the early ’70s (the 50th anniversary of its acquisition of a proper business license will be celebrated this September), reopened in August 2021. Immediately, Gonyer, who spent 12 years on campus as a grad student and staffer, concentrated on reconnecting with various university departments and the alumni association, which regularly rent out the bar’s back area, the Snug Room, for catered events.

The walk-in crowd, as always, is varied. Grad students typically trickle in at about 3 or 4 p.m. for an early happy hour, followed by faculty and staff at 5 or 6. Undergrads start to show up around 8 or 9, and after midnight, lingering grad students and staff from other bars are usually the ones left holding court.

Further exemplifying how dyed-in-the-wool Seattle Gonyer and her husband are, he’s the president of the Seafair Pirates, and she gets nostalgic when talking about how the city has changed over the decades.

“I could never take my grandchild around and show her the original buildings. Almost everything from our childhood and adult lives is gone,” laments Gonyer, who plans to sell the pub by mid2025 now that her goal of restoring it has been achieved.

“Being from a historical field and knowing the power of touchstones that build community, we saw the power of the pub and decided to give it a shot.”

Thankfully, she is not alone. The Ave and the U District at large have seen their share of changes over the years as Seattle has grown more affluent and prone to gentrification. But there’s something about the Ave that remains distinctly the Ave, thanks in no small part to the likes of the College Inn, Big Time, Shultzy’s, Earl’s, Bulldog News, Cafe Allegro, the Neptune, the Grand Illusion, Red Light Vintage, the Woolly Mammoth, Magus Books, Thai Tom and Gargoyles Statuary— eclectic, long-standing businesses that will ring familiar to many a UW alum returning for a stroll through the neighborhood’s central corridor.

Cafe Allegro, which opened in 1975, is one of Seattle’s oldest espresso bars, while Big Time (established in 1988) was the city’s first brewpub and the Grand Illusion (1970), its first arthouse cinema.

Meanwhile, Bulldog News, founded in 1983 by UW grad Doug Campbell, is Seattle’s longest-running newsstand.

“I had been looking for a place to open a newsstand since the mid-1970s,” says Campbell, who was also the projectionist at the Grand Illusion from 1982 to 1985. “At that time, the Ave was pretty busy. [There were] not a lot of retail spaces.”

The College Inn Pub (right) was brought back to life by new owners Jen Gonyer and her husband Al Donohue after it closed down during the pandemic. The legendary hangout remains as popular as ever.

Doug Campbell, left, opened Bulldog News in 1983. At right, Big Time Brewery, which opened in 1988, continues to be a U District mainstay. And the ever-popular Neptune Theatre, lower right, remains a favorite entertainment venue thanks to (L-R) Dan Reinharz, associate director of operations for the Neptune and Moore theaters, Neptune manager Miranda Bahr and Neptune stage manager Josh Bahr.

Originally operating out of the space now occupied by the Burger Hut, Bulldog has long paired coffee with its collection of hundreds of magazines and newspapers, boasting one of the earliest espresso machines on the Ave. And Campbell makes it clear that Bulldog’s brisk coffee trade, and not its print publications, keeps the business solvent.

“The magazine business as a whole is constantly shrinking,” says Campbell, who counts The New Yorker, Harper’s, Monocle and The New York Review of Books among his business’ more popular titles. “Undergrads are not big magazine customers. Our core audience is people above 50. They probably come to the U District looking for magazines.”

Political magazines and those catering to specific niches—sports card collectors, gear heads, those with an affinity for foreign

fashion—also tend to do quite well. Referring to a recent New York Times article about the newfound success of pricey, small-circulation publications, Campbell says, “I think that, in five years, that’s gonna be the strong spine of the magazine business—like people who used to collect National Geographic and have multiyear collections. I think that magazines are going to become more like that—still shrinking in circulation but increasing in quality.”

As for the Ave itself, Campbell, long a political animal, thinks it “should become pedestrianized and not be oriented toward diesel buses and automobiles.” He counts Gargoyles and Magus Books (around the corner from Bulldog) among his favorite businesses, while Big Time is his favorite drinking establishment.

“Rick [McLaughlin], the owner, is a really big-hearted guy,” he says. “His big-heartedness is expressed in the way that place is run all the time. You’re not just at the table you’re sitting at, you’re part of that big space.”

When the U District tries something new, it’s often rooted in the old. Take the Mountaineering Club, for instance. A rooftop bar offering craft cocktails and panoramic views atop the Graduate Hotel, it’s probably the poshest business to open in the neighborhood in recent memory. Yet it hardly neglects its roots.

While retaining its classic Art Deco look, the Graduate has been through several name changes since opening as the Edmond Meany Hotel in 1931. Meany was one of Seattle’s most influential and dynamic citizens in the late 1800s and early 1900s, thriving as a journalist, state legislator (he helped secure funding for UW’s present-day campus) and head of UW’s history department. Meany was also president of The Mountaineers, and his influence can be spotted all over various Mountaineering Club features—not the least of which are the mountain ranges visible on a clear day.

Sharing the intersection of Northeast 45th and Brooklyn Avenue Northeast with the Mountaineering Club and the Graduate is the Neptune Theatre. In the roaring ’20s, it was a large-capacity movie house; now, Seattle Theatre Group has recast the Neptune as a vital live-music venue while retaining its historic charm. (Movietheater popcorn is still available for purchase in a cute nod to the ghosts of the venue’s Rocky Horror Picture Show past.)

Dan Reinharz ran the bar program at the Neptune before he became its theater manager in 2014. He held that job for 10 years before a recent promotion, but of his decade at the helm of the U District institution, he says, “I developed a love for the Neptune in the years I was there. It had a very strong family vibe and the people were terrific.

“The Neptune is one of those venues where you get people on their way up and then on the other side of the mountain. It’s especially exciting when you get someone on the way up and they just blow the doors off the place,” adds Reinharz, mentioning Leon Bridges, Lizzo and Jason Isbell.

“We have three venues (Neptune, Moore, Paramount). If we can latch on to an artist early, we can graduate them up through a good portion of their career. After the Paramount, you’re playing arenas.”

Reinharz describes the Neptune’s festival-seating arrangement as “very democratic,” which are two words that could be used to describe the U District as well.

“You can’t talk about the U District without mentioning Thai Tom,” he says. “Earl’s, you got to love and hate it at the same time. Shultzy’s is great, the College Inn is great. The challenges make it a lot of what it is. To me, those are things that you deal with in an urban community.”

The star power at the TIME100 Gala in New York City last October rivaled the bright lights of nearby Broadway. Luminaries like director Steven Spielberg, actor Angela Bassett and rapper Doja Cat took center stage at the magazine’s glittering annual celebration of the 100 most influential people in the world.

The spotlight shifted from glamour to grit when honoree Tracie D. Hall, ’00, took the microphone. The widely acclaimed “warrior librarian” had earned national attention for her tenacious fight against censorship during her tenure as executive director of the American Library Association. In her toast, she honored her fellow librarians, her fellow warriors, who “despite bomb threats and threats of jail time are fighting to ensure that these words that stand as a vision of the American Library Association will always ring true: Free people read freely. Free people read freely. Free people read freely.” As she closed her toast with a fourth exhortation of those four powerful words, the A-list audience responded with a standing ovation.

Those four words remain Hall’s rallying cry as she continues her crusade defending libraries as the bulwark of democracy, vital for enhancing learning for all and instrumental for unleashing the intellectual and social potential of patrons, especially young ones. Her passion for working with young adults and for advancing her field has brought her back to UW’s iSchool as a Distinguished Practitioner in Residence. In her courses and research, she is

2023

4,240 BOOKS

providing the next generation of librarians with the real-world context necessary to better serve an increasingly diverse public in the face of ever escalating challenges. “I hope I can be a source of the same kind of inspiration and learning that I experienced at the iSchool,” says Hall.

Hall discovered the magic and power of libraries at the side of her grandmother, Bessie Marie Sanders-Scott, who had a limited education while growing up in the rural South and was awed by all that libraries offered. The pair frequently walked together to their local Watts branch of the Los Angeles Public Library, where Hall occasionally crashed story time for younger children by acting out the plot lines and found herself transported to far-off places in the books she read. “The library was a place where my grandmother encouraged me to roam free, to leap in and discover,” Hall recalls.

It was in one such far-off place that Hall first experienced the harsh impacts of censorship: at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, where she studied abroad as an exchange student at the University of California Santa Barbara. Due to tight government controls, Hall and her classmates in her African literature class had to search for their assigned books at Nairobi’s contraband market. Whoever found a book passed it around so everyone could write out chapters like scribes.

lifeblood of democracy,” she says. “It contributed to my belief that intellectual freedom has to be the core of all education and the foundation of librarianship.”

After earning a master’s degree in international studies from Yale University, Hall returned to California to work in Santa Monica as a director of a shelter for unhoused youth. She introduced the shelter’s residents to the wide array of services and materials available at the local library branch, not just for reading pleasure but for educational advancement.

“I saw how welcoming the librarians were to our unhoused youth,” she says. “I saw them doing the same work as I was, but through books and reading. That spoke to my curiosity and has everything to do with why I went from just loving libraries to really setting a life goal to work in them.”

When the shelter closed, Hall’s experience there positioned her perfectly for leading a youth-outreach program for the Seattle Public Library. There, she was encouraged to consider applying to library school by visiting American Library Association staff member Satia Orange, who told Hall about the then-new Spectrum Scholarship Program. It recruits and provides scholarships to students from underrepresented groups to help them obtain a graduate degree in library and information sciences and land leadership positions within the profession and the ALA. Hall applied to UW’s iSchool and graduated two years later with her master’s degree.

The iSchool “changed me,” she says. “I was elated my entire time there. Everything I learned felt new. I knew it wasn’t just conceptual. I could see how what I was learning could make a difference not only in my life but in the lives of the people I’d worked with previously, people in the neighborhood where I’d grown up.”

Hall thrived under the mentorship of the late Spencer Shaw, a beloved longtime professor of library science at the iSchool, a nationally recognized storyteller and advocate for children’s reading. “Having someone like Spencer Shaw as your visiting lecturer shows you the caliber of instruction at the iSchool,” Hall says. “It was like having Fred Astaire as your dance instructor.

“He set a high standard,” she continues. “The first area I worked in was young adult services, and I approached it with a sense of gravity and professionalism. Not just because children’s and young adult literature is what caught my own attention, but because Dr. Shaw had stressed the role children’s literature can play in the development of children’s intellectual and social development.”

Hall followed in Shaw’s footsteps after graduation by taking a position at the Hartford (Connecticut) Public Library, where Shaw had been the first-ever Black librarian hired and eventually manager of the same Albany branch that Hall took charge of. She fully embraced her title of community librarian by embedding herself in the library’s surrounding African American and AfroCaribbean neighborhood to better understand and respond to residents’ informational needs. “I began to feel a personal responsibility for supporting every family, every resident, every student in our service area,” she says.

She launched free summer science and photography camps. She hosted poetry readings and talks by Caribbean authors including Rosa Guy and Edwidge Danticat. She showcased artwork by local artists. She offered free computer courses six nights a week. She transformed the Albany branch from having some of the lowest visitation and circulation numbers in the library district into a showpiece where patrons would proudly bring visitors and politicians would kick off campaigns. In recognition of Hall’s achievements, in 2003 Hartford’s mayor declared Feb. 13 “Tracie Hall Day.” “I’d learned from librarians like Spencer Shaw, Anwar Ahmad and Satia Orange,” Hall said, “and I wanted to honor the precedent they’d set.” REF02

“That’s where I really understood how dangerous censorship was, how it stifles potential, intellectual development and the

Hall was recommended for the executive director role at the ALA, in part, because of her contributions as the association’s director of what’s now called the Office for Diversity, Literacy and Outreach Services from 2003 to 2006. Her co-authorship of “Diversity Counts,” the ALA’s first racial and ethnic census of the profession, galvanized the library field. “It gave us the necessary data to do something about the gap between who worked in libraries and made decisions about library services and who used them,” she says.

To help close that demographic gap, she secured grants to permanently endow and expand the Spectrum Scholarship Program that had enabled her to attend the iSchool. The program has now supported more than 1,300 students nationwide. Hall also led the design and secured the funding for the initial Spectrum Doctoral Fellowship, created to diversify the library and information science professorate.

Hall’s career path during the 14 years between her two tenures at the ALA drew on not only her formidable community building and librarianship skills but also her artistic interests as a poet, writer, artist and curator, and development as a sought-after organizational strategist. She worked in corporate social responsibility for Boeing, as vice president of strategic planning and organizational development at the Queens Library and as assistant dean of the LIS program at Dominican University. “To meet someone like Tracie who looks like me, was around my age and had an administrative role was so inspirational for me,” says Joslyn Bowing Dixon, a Dominican LIS graduate and library administrator for whom Hall remains a mentor. “It meant that I could do it, too.”

Hall also served as deputy commissioner for Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events and as director of the culture program of the Joyce Foundation, a $1 billion philanthropy advancing racial equity in the arts as well as economic mobility in the Great Lakes region.

“What speaks to me most in any job opportunity is the size and intensity of need,” she says. “There has to be some sense of high stakes attached. The setting doesn’t matter to me. There’s not much difference, really. Government agencies, nonprofits and Fortune 500s are all run by people. It’s about the problem to be solved. If the work to be done intimidates me a bit, I know it’s right.”

The stakes could not have been higher after Hall became the first Black woman to lead the ALA and its 50,000 members since its inception in 1876. A mere month after she took office in February 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. “It posed an existential threat not just to the association but to libraries in general,” Hall says. “Librarians were very much on the front lines. Even as libraries began to close, we couldn’t stop providing library services.” Librarians sprang into action to reduce the digital access divide that disproportionately affected patrons in disadvantaged communities.

Hall soon faced surges in an equally alarming threat: censorship. Starting in 2020, the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom documented a precipitous rise in attempts to ban book titles in schools and public libraries, with books by LGBTQIA and BIPOC authors the predominant targets. In 2023, there were efforts to censor 4,240 unique book titles, a 60% increase from the year before. In Florida alone, 2,672 titles were challenged in schools and libraries in 2023.

The ALA responded by creating the Unite Against Book Bans campaign. “It’s a playbook for standing up against censorship, preserving our democracy and ensuring that policymakers and the public do not fall sway to that very small, politicized minority that sees in book banning a way to wrestle some political ground or status for themselves,” Hall explains.

National organizations, from the Author’s Guild to the Human Rights Campaign to the American Federation of Teachers, joined

the initiative. Hall became the resonant voice speaking out against censorship, rallying new recruits to the “Free People Read Freely” cause. “Tracie is one of the greatest spokespeople we’ve ever had in the library world,” says Chris Brown, commissioner of the Chicago Public Library. “She was able to reach out beyond our field and connect with Americans about the importance of libraries, of freedom of speech and our First Amendment rights.”

Hall’s passion and perseverance earned her a multitude of honors: Forbes Magazine’s 50 Over 50: Impact List; the National Book Foundation’s Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community; the medal for Freedom of Speech and Free Expression by the Franklin D. Roosevelt Institute; and, of course, the TIME100 list. “I’m grateful for each and every honor I’ve received professionally, because they reflect on the entire sector, particularly library workers’ commitment—through Covid and now censorship—to serve their communities and to keep information open and accessible no matter the obstacles,” Hall says.

Hall’s transition between the ALA and the iSchool was anything but a respite. She testified on Capitol Hill about the dangers of the rise of censorship and the perils of inattention to low adult literacy. She gave presentations in Colombia and Australia. She conducted research in England on the impact of Brexit on public libraries. And she cut the ribbon on a project near and dear to her heart. The Litanies for Survival reading room in Chicago is a space stocked with works by and about people of color and the LGBTQIA community—the very books being banned elsewhere.

This fall at UW, she’ll continue her ongoing research on the connections between censorship and low literacy, teach information management and introduce a course on the Black information future. “I’ll use the social, economic and political conditions that Black people have historically faced and that they face today to imagine how libraries and information services can predict and prepare for their future information needs,” she says.

She’s encouraged by how attuned young people are to the perils of censorship. “They are starting to organize, because they’re the ones being impacted,” she says. “They are more diverse, racially, ethnically, and in terms of gender expression, than previous generations, and they understand how important it is to amplify their lived experience.”

And she’s invigorated by students’ energy. “Most of them are at a point where it’s all about potential and possibility,” she says. “They are willing to experiment. They haven’t ‘done it all before.’ Exploring, experimenting has been my entire approach to life, so I find working with students especially gratifying.”

Tracie D. Hall developed a national reputation leading the charge against censorship. Says Chicago Public Library commissioner Chris Brown: ‘Tracie is one of the greatest spokespeople we’ve ever had in the library world. She was able to reach out beyond our field and connect with Americans about the importance of libraries, of freedom of speech and our First Amendment rights.’

Valerie daggett, a uw scientist on a quest to understand protein dynamics, has developed a novel approach for the early diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease as well as other neurodegenerative conditions. Now, with guidance and resources from CoMotion, the UW’s innovation hub, she is on the brink of bringing her breakthrough to the real world.

Daggett discovered her talent for numbers and equations as a middle schooler in Oregon, when she cruised through highschool-level mathematics. When she got to high school, her teachers kept her busy working on proofs, priming her for research in college. “Then in college, when I started doing physics and realized you could apply the math to real things, it got even more interesting,” Daggett says from a desk in her gleaming new laboratory overlooking Lake Union. She is helming AltPep, the company spun off from her UW research to develop and commercialize a blood test for Alzheimer’s and provide therapeutics to stop its progress.

In college, Daggett pursued science, discovering she loved chemistry and then falling for proteins, the building blocks of life. She wanted to know how they worked, how they unfolded and how they influenced what happens in the human body. She followed this curiosity to graduate school and a postdoctoral position at Stanford University with structural biology professor Michael Levitt, whose work exploring the world of molecules through computers led to the 2013 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. There, she sought funding and established her own projects using computer simulations to explore protein unfolding and misfolding.

But when it came to setting up her own lab, Daggett was eager to move from the crowded, expensive Bay Area back to the Northwest. Arriving at the UW in 1993, she launched her research program to conduct computational work simulating the folding and unfolding of proteins. Raising funding wasn’t easy because it was a new area of study. “People weren’t believing it,” she says. “And it wasn’t helping that I was the only woman in the field.”

Her first lab was “in a closet in Bagley Hall,” she says, where research scientists and students perched at computers and focused on amyloids: abnormal aggregates of proteins that have been associated with diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and type 2 diabetes. One of their significant discoveries centered on identifying causes of neurodegenerative diseases and exploring therapeutic responses. They took their findings from their computers to the hands-on laboratory, to test them in real-life settings, and the results were increasingly promising, leading to a highly accurate method of finding misshapen proteins.

Financing her research through federal grants and other sources was cumbersome, Daggett says. “We had something that could really change Alzheimer’s detection and treatment, and I felt driven to move it out of academia and into a situation where we could move faster,” she says.

Enter CoMotion, the technology transfer office and innovation hub at the UW. Created shortly after the Bayh-Dole Act of 1980, it helps researchers and students bring their discoveries into the real world. It has evolved into an assemblage of interconnected services and programs designed to catalyze innovation and startup creation and to build connections among UW researchers, entrepreneurs, investors and the broader community.

Five years ago, François Baneyx became UW’s vice provost for innovation and director of CoMotion. A professor of chemical engineering and bioengineering, Baneyx had the experience of launching one of his own ideas into Proteios Technology, Inc., which produces affordable and easy-to-use kits for purifying proteins and isolating therapeutic cells.

Under his leadership, CoMotion has expanded to serve more UW-affiliated innovators, providing training, IP strategy advising, funding, mentorship, incubation space and connections to industry. Daggett’s team, for example, secured bench space for its new company in CoMotion Lab’s life-sciences incubator. Two other incubators across campus focus on technology and hardware.

CoMotion has also expanded programs, workshops and resources to help startups navigate and network their way off campus. The Innovation Gap Fund provides UW researchers

By Hannelore Sudermann Ilustration by Ewelina Karpowiak

and students with early stage funding of up to $50,000 to bridge the journey between their research funding and early commercial investment. Baneyx is also intensifying CoMotion’s efforts toward inclusion, diversity and equity in the regional startup community, bringing in industry mentors from diverse backgrounds and providing focused support for women and people of color who are underrepresented in the startup ecosystem.

“Before they become a company, we can do a lot for them,” Baneyx says of all UW-related startups. “We have lawyers on staff that can help them protect their IP. We have programs that help them think about licensing their technology with different companies. We can teach them to pitch their product and match them with mentors who meet their needs.”

In 2020, the UW formed the Innovation Roundtable, convening investors, industry leaders, academics and nonprofit principals around a mission of connecting UW research with industry and addressing complex challenges like health care and environmental sustainability. A few years ago, the group, which included investors and entrepreneurs Chris DeVore, Mike Halperin, ’85, ’90, and Matt McIlwain, identified a significant challenge that seems

The UW receives more federal research dollars than any other public university in the United States. CoMotion’s role is to help bring to market the discoveries and inventions that come out of this research by providing training, IP advising, funding, licensing and mentoring opportunities. It also offers incubator space and wraparound programming to get fledgling startups on their feet.

Total funding raised by UW spinoffs since 1994

287

117 Active UW spinoffs in Washington spinoffs from CoMotion

3,249

Employees working at UW spinoffs

unique to Seattle startups: a dearth of early stage investing.

“The UW does a great job of marshaling the resources and bringing in and developing talent from around the world,” says Ken Horenstein, ’10, ’16, founder and partner in Pack Ventures, LLC, a venture capital firm focused on UW alumni and campus-connected startups. He adds that university research is leading to significant discoveries in computer science and the life sciences, particularly with therapeutics, “but there’s a little bit of a gap in securing funding to help facilitate those spinouts.”

“UW founders are being overlooked and undervalued [compared to startups from Ivy League schools], even though they progress to the same mean as the Ivy Leagues in the next round of funding,” he says. While many of Pack Ventures’ partners are seasoned investors, Horenstein envisions the firm being a conduit for newer investors who want to back UW-connected startups.

Pack Ventures has invested in several startups including seven from alumni of the UW’s Institute for Protein Design. “By 2030, we want to invest in 150 UW-affiliated founders,” Horenstein says. “This is us really catching up and being competitive with other universities and having this as a resource for our founders—our students and professors.”

In early 2024, CoMotion and UW Advancement, the division responsible for fundraising, alumni relations, and marketing and communications, signed a memorandum of understanding with

Pack Ventures allowing the fund specific use of UW imagery and trademarks. In exchange, the firm will work with CoMotion to plan educational and training events for UW researchers, students and faculty, and it will coordinate with entrepreneurial and startup development programs on all three campuses. It also made a non-binding commitment to gifting a small share of its profits back to the UW to support innovation.

“We feel Ken is bringing so much value by providing complementary services, teaching classes and seminars through a VC lens, and pledging to reinvest in the UW,” Baneyx of CoMotion says, adding that Pack Ventures is independent of the UW, gets no preferential access and that CoMotion works with all interested investors.

“What I hope to emphasize is what’s new with CoMotion and help people understand the complexity of what we do and the constituencies we serve,” says Baneyx. With nearly $1.9 billion in sponsored grants and contracts at the UW, there are many more discoveries and ideas to bring out of academia, he says. “Our focus is to help scale lifesaving technologies and making lives better across the world.”

Daggett has been working with CoMotion and its predecessors since 2007. It started with visits from the organization’s experts to help her protect technology invented in her lab. “It took about 10 years to get our platform patent,” Daggett says. “We were

doing something that was really novel, and the [U.S.] patent office struggled to understand it because we sought to patent a structure, not an amino sequence.” During that time, the lab used its platform (or templated structure) with different amino acids, testing it over and over again, getting the data and showing that it worked with Alzheimer’s as well as Parkinson’s and other amyloid diseases. “The patent office finally said, ‘OK, we get it,’” Daggett says. That was in 2018. “At that point we could spin out,” she says. And her company, AltPep, was born.

With the patent and seed funding, half a workbench in Fluke Hall wasn’t going to do it. Daggett moved her lab off campus to Northlake Way Northeast to “a funky space near Ivar’s.” It was still too small. Then COVID-19 slowed everything down, but it allowed Daggett to shift her focus to finding investors. “CoMotion was important in all of that,” she says.