Telling the Story of Diversity at the

Welcome to the Fall 2022 issue of View point. We began the quarter full of excite ment. Some of that excitement is related to us welcoming one of the most diverse group of students ever to study at the Uni versity of Washington. As the University becomes more diverse, we have an even greater responsibility to ensure that the campus is welcoming to each new and returning student, as well as to faculty, staff, alumni and visitors and the complete identity of each—a place where they feel a sense of belonging.

Belonging is about far more than just a physical space or being around like-mind ed peers or colleagues. It is about the in tention put into fostering a climate that is equitable and inclusive, where people can bring their full selves. It is about ensur ing that our physical environment is rep resentative of those who learn, live and work here. Mostly, it is about fostering a culture where an individual’s differences and experiences are not overlooked or tokenized, but instead valued. With this in mind, the University of Washington Diversity Blueprint prioritizes cultivating an accessible, inclusive and equitable cli mate. That includes recruiting and retain ing a diverse student body, faculty and staff. It also prioritizes the development of place-based education and engagement

to advance access, equity and inclusion.

In this issue of Viewpoint, you will read about the individuals who help advance a more inclusive and equitable university ex perience. You will read about Vern Harner, a graduate student who helped change a complex administrative policy to be more inclusive to transgender students. We wel come the new dean of the UW School of Law, Tamara Lawson, and the impact she is already having on campus. We tell student stories of belonging and finding their com munity within OMA&D, and we share the success of former Educational Opportunity Program student Ricardo Ruiz, and the publishing of his first book of poetry, “We Had Our Reasons.”

As a world-class university, we have a great deal to celebrate about our current students, alumni, faculty, and staff. There is no shortage of examples that show where and how those who call this institution home find their sense of belonging and help create the space for others to do the same. As you read these stories, I hope you reflect on where you found a sense of be longing at the UW or what made you feel as though you belonged.

Published by the UW Alumni Association in partnership with the UW Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity

4311 11th Ave. NE, Suite 220 Box 354989 Seattle, WA 98195-4989 Phone: 206-543-0540 Fax: 206-685-0611 Email: vwpoint@ uw.edu Viewpoint on the Web: UWalum.com/viewpoint

VIEWPOINT STAFFPaul Rucker, ’95, ’02 PUBLISHER

Hannelore Sudermann, ’96 EDITOR

Ken Shafer ART DIRECTOR

Chris Talbott STAFF WRITER

Matt Hagen

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHER

Manisha Jha, Lauren Kirschman, Misty Shock-Rule

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Rickey Hall

Vice President for Minority Affairs & Diversity University Diversity Officer

Tamara Leonard

Associate Director Center for Global Studies Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies

Eric Moss Director of Communications Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity

Students Isabel Corona-Campiz, left, and Fati ma Gbla have not only found ways to deepen their own sense of belonging on campus, they are helping other students find belonging.

Artist Nina Chanel Abney was inspired to explore the history of Black Americans in the fishing industry by Gordon Parks’ pho tographs of fishermen and fish markets from the 1940s. She saw that fishing has deep roots in the Black community, but that the voices of Black fishermen are underrepresented in photographs and much of the historical record. Her collages, which she cre ated during a Gordon Parks Foundation fellowship, are now on display at The Henry Art Gallery. Chanel Abney's work cele brates the Black self, community, sanctuary and leisure. It also reconsiders the entangled legacies of exploited labor, land use and property that continue to shape society in the United States. The exhibit runs through March 5.

“Sea and Seize,” 2022. ©Nina Chanel Abney.

While completing their PhD in social wel fare, Vern Harner led the effort to change University policy for names on diplomas. Now it is possible for trans students to have diplomas reflecting their chosen names. Harner recently joined the faculty as an assis tant professor of social work at UW Tacoma.

Vern Harner spent a lot of time and emo tional energy fighting to get their chosen name on their diploma at their previous school before heading to the University of Washington to begin a social welfare doc torate. Given the UW’s reputation as an LGBTQIA+-friendly environment, Harner didn’t expect to have to do it all over again as they neared graduation in Seattle.

After asking around, Harner found that many fellow trans people had asked the same question: Why can’t I have my cho sen name on my diploma? “A lot of folks were surprised that this was still a battle that had to be fought in 2021,” Harner says. “We’re hearing from places like UDub that they value diversity, they value what I bring as a trans person doing trans work. But then they won’t put my name on the diploma? Those things are at odds, right?”

University Registrar Helen Garrett agreed with Harner and their list of reasons the policy should be changed—individual preference, professional clarity and person al safety among them. When she came to the UW in 2016, Garrett had overseen the

University’s adoption of a preferred-name practice—students can choose whatever names they would like on their university records.

She was sympathetic to the idea. But UW policy required a legal name on diplo mas, and Garrett didn’t have the power to change that. The decision rested with the faculty senate.

Garrett outlined steps the senate need ed to take to change the policy permanent ly. Harner, who completed their degree last spring and is now an assistant professor of social work at UW Tacoma, decided to make sure it happened.

Armed with a petition containing near ly 32,000 signatures and with support from UAW 4121, the union of academic student employees and postdocs, Harner contacted faculty senate leaders. To them, in retrospect, the request seemed obvi ous. “Of course, you should be able to put whatever name you want on your diplo ma,” says Chris Laws, former faculty sen ate chair. “You work hard for that diploma and it’s yours.”

Obvious or not, the process took time. First, there were new procedures to work out with the registrar. Then there was a process of approval from the senate and the provost’s office. Graduates receiving diplomas in September 2021 were the first to have the option to use their preferred names. It took a few steps, but trans stu dents will not have to fight this fight again.

“The moral of the story,” Garrett says, “is if you want to impact change, you’ll want to find what are the systems and who is in charge, and that’s exactly what happened here. This is a good lesson for any student to learn. Following through on those pro cesses will give hope to other students.”

“This is a real testament to how well shared governance works at the Univer sity of Washington,” Laws says. “People sometimes like to talk about how the gov ernance system is clunky or doesn’t work. It does work. And this is a very clear exam ple of how students and faculty and admin istration came together to solve problems in a very effective way.”

Harner hopes this process will make clear that there is still work to do to make all students feel welcome and hopes that University leadership will seek out oth er disconnects. “I know that to some ex tent there is an awareness of these is sues there,” they say. “But I’d like for folks in power across campus to make these changes before a student has to become a squeaky wheel.”

UW trans students can now choose their preferred names on diplomas, thanks to the efforts of a graduate studentUW SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK

Professor Emerita Colleen McElroy, ’73, was recently honored by the College of Arts & Sci ences. Her name now graces the main confer ence room in the dean’s office in her honor.

McElroy, a mentor and inspiration to many students, earned her doctorate in educa tion at the UW. Her focus was ethnolinguis tic patterns of dialect differences and oral traditions. She also started writing poetry in graduate school. Early in her UW career, she supervised freshman composition in the Equal Opportunity Program and taught po etry classes, which eventually became a fulltime creative writing position in the English department. In 1983, McElroy became the first African American woman to be made a full professor at the UW. She is the author of 12 books, including “Queen of the Ebony Isles,” which won the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation.

The UW's new po lice chief, Craig Wilson, has served 26 years in the de partment.

The UW’s new police chief, Craig Wilson, is an alum, a Navy veteran, a career UW police officer and a parent. He brings all of it to the job as the UW’s lead public safe ty officer.

He takes the helm at a time when the University—with the help of students, fac ulty and staff—has been working to im prove and transform safety school-wide. In September, the University announced a new Campus & Community Safety division that brings together SafeCampus (a unit that helps students, faculty and staff pre vent violence), the UW Police Department and UW Emergency Management. The new holistic approach is a step in an on going process to reimagine safety—includ

choice was already on campus. In late July, the announcement of Wilson’s promotion to chief cited his “track record of commu nity collaboration and trust.”

The UW Police Department is accredit ed by the Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies and the Wash ington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs. The officers are trained in law en forcement, critical incident management and customer service.

“When you look at our size and the total ity of the community that we represent, it is the size of a city,” says Wilson. “However, it is kind of a different type of policing we do at the UW.” The department works with students, faculty and staff to provide a safe and secure environment where the com munity can focus on learning and research.

The UW is also engaging with the City of Seattle, Seattle Police and the U District Partnership to prevent violence near cam pus. Events in early October, including a shooting on The Ave where four students were injured, prompted the University to deploy a trained (not armed) security patrol on Friday and Saturday nights.

In recent years, the UWPD has faced scrutiny with both internal challenges and national events—including the 2020 mur der of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis—exposing a widespread dis trust for law enforcement. Student groups called for defunding the department and disarming the officers.

The UW welcomed one of its largest and most diverse incoming classes in late September at the New Student Convocation at Hec Ed mundson Pavilion. The ceremony set atten dance records with more than 7,500 students, family and friends.

The incoming class at the main campus is estimated to top out at around 7,250 students, with nearly 15% being from underrepresented minority groups and 23% first generation. An additional 1,150 transfer students are expected to arrive this fall, about 80% of whom will be from Washington community colleges. Official numbers will be reported later in the quarter.

UW Bothell and UW Tacoma also welcome their incoming classes, with about 980 and 600 freshmen and about 510 and 640 trans fer students expected, respectively.

ing individual wellbeing, crime prevention, crisis response and unarmed interventions.

Wilson, ’94, hails from Alabama and served aboard the USS Long Beach, a nu clear-powered guided missile cruiser. The Navy brought him to the Northwest and “I immediately fell in love,” he says.

After his tour of duty, he enrolled at the UW to pursue a degree in law, society and justice. He then pursued his MS in law and justice at Central Washington University.

After graduate school, Wilson joined the department. “The rest is history,” he says. For the past 26 years, he has climbed the ranks from patrol officer to deputy chief. In January, Wilson was tasked with lead ing the department while a national search for a permanent chief took place. The best

The UW administration began working in earnest with faculty, staff and students to explore long-term changes in public safety work as the country began reckoning with the history of policing and the spread of ex pectations facing officers.

Police and other safety staff are focusing on how to respond to incidents in ways that respect individuals and help them feel saf er. Under Wilson’s leadership, UWPD con tinues to work with campus groups on de termining how UWPD’s officers, Campus Safety Responders and security guards help achieve safety and the sense of safety, and help the campus thrive.

There are more changes ahead, Wilson says. “We want to make sure the commu nity has a police department that is here to represent everyone and here to protect ev eryone,” he says. “It’s a new era of public safety on campus.”

the story of diversity at the

In late summer, Tamara Lawson started work as the Toni Rembe Dean and profes sor at the Univer sity of Washington School of Law.

The UW’s new law dean, Tamara Lawson, brings both a record of academic and of fundraising success and real-world experi ence. Her scholarly work includes examin ing the trials and outcomes of the Trayvon Martin and George Floyd cases. Her ex pertise includes enforcement inequality in crimes against women and police brutality. She is also passionate about mainstream ing civil rights in law school curriculum.

“She’s amazing—obviously,” says law student Annalyse Harris. When Harris, then at St. Thomas, heard Lawson was headed for the UW, she transferred to fol

low her. “She is so intellectual. She encom passes so much more than just education. She advances equality and justice and al ways promotes an academic and innova tive atmosphere. And she’s so personable. People love her.”

As dean at St. Thomas University in Florida she turned a financial deficit into a surplus, boosted enrollment by almost 40% and secured a $10 million donation, the largest in St. Thomas history. She also over saw the retooling of the curriculum at the College of Law and founded the Benjamin L. Crump Center for Social Justice. During

her 18-year tenure at the school, she taught courses in criminal law, criminal procedure and evidence and seminars on race and the law, twice earning professor-of-the-year honors.

Lawson was born in Los Angeles and grew up in California. She attended Cla remont McKenna College and the Univer sity of San Francisco School of Law. Her work as a Clark County deputy district at torney in Las Vegas included the special victim’s unit for domestic violence. She also argued cases before the Nevada Su

preme Court. Not long after completing a Master of Laws degree from the George town University Law Center in 2003, she joined the St. Thomas faculty.

As Lawson started her new job at the UW this fall, she spent her first few weeks building relationships.

“Dean Lawson is quickly establishing herself as an engaged and visible leader,” says Provost Mark Richards. “She has met with members of the Washington State Supreme Court, UW faculty, staff and student leaders. In addition to exploring a philanthropic campaign to secure resourc es for scholarships, she plans to share her expertise with students by teaching a course on race and the law.”

Lawson sees UW law as a “good bones, good foundation” school with a communi ty that wants to expand its diversity work. “As they say in the international world,” Lawson says, “there’s a coalition of the willing. And we want to work together for this larger goal—the goal being the best public law school measured by global im pact and the programs that we have.”

The school’s current Asian and Indian law programs are great strengths, and the Ph.D. program is “unique in the country,” she says. There are other natural partners in the community for future growth in teaching and scholarship, she adds. “Our proximity to Asia and the benefit of tech nology right here in our backyard, these things are synergies that we have to maxi mize for the benefit of our students.”

Lawson has written and lectured exten

The UW’s new law dean wants to infuse social justice and civil rights throughout the law school curriculumGREG

sively on legal issues, tackling troubling aspects of our legal system like police bru tality, prosecutorial bias and stand-yourground laws. Her pieces blend easily iden tifiable cultural references with tricky legal concepts. In one study, she looked at how TV shows like “CSI” are harming the crimi nal jury process.

She points to prosecutorial discretion as a problem in a legal system that requires lawyers to be experts in increasingly com plex areas like race and civil rights. She has written about the legal cases surrounding the deaths of Martin and Floyd, whose kill ers received very different legal outcomes. Martin’s killer was exonerated, while Floyd’s will spend decades in prison.

“Not only do you have to deal with your objective facts, you also have to as an effec tive litigator deal with what’s truly on the mind of the jurors when they go in their room and deliberate,” Lawson says. “And so we saw a very different version when we saw the prosecution of Derek Chauvin for the Floyd allegation of murder.”

These sorts of distinctions are more obvious to those who have a varied law school experience, she says. Many Ameri can law students receive little or no train ing in the areas of race and social justice. Lawson would like to see that sort of coursework woven throughout the UW’s curricular tapestry.

“I do know that the faculty is very aware of the importance of these issues, as well as the University,” Lawson says. “The DEI work of the University of Washington is first class or model setting, I would say. And it’s part of what drew me to this par ticular school, because there’s a desire to impact justice.”

Lawson also blends an entrepreneurial background with her social justice and academic work. Her skills in negotiation and networking helped her connect Benja min Crump, the prominent civil rights at torney who represented the Floyd family, with St. Thomas. He had no previous ties to the school, but Lawson engaged him in supporting a social justice center to train the next generation of social justice legal experts.

She plans to build similar relationships at the UW. “It’s important that we look at not only our alumni base and our existing donors to reinvigorate them and engage them, but we also need to bring in new partners and to make the case as to why it’s important that they should partner with us,” Lawson says. “I bring that en trepreneurial spirit to being a dean. And I think I’m unique among my peers, that I not only embrace the teaching, embrace the scholarship, but embrace the going concern of this business enterprise that we have for the benefit of the students.”

Botanical gardens have historically been exclusive spaces. The University of Wash ington is working to change that starting with its own gardens—the Washington Park Arboretum and the Center for Urban Horticulture.

Many botanical gardens around the world originated as private spaces for pre dominantly white and wealthy individuals, says Christina Owen, director of the UW Botanic Gardens. And building the collec tions often involved biopiracy and replac ing the plants’ Indigenous names with scientific names that often referenced the collector, she says.

department's equity and justice committee was creating a speaker series to explore how public gardens can meet the needs of diverse local communities. Owen is build ing out this effort to center equity and so cial justice work, increase the diversity of staff and enhance the culture of support for employees of color.

The UW Botanic Gar dens are centers for horticultural research and conservation.

Around 600,000 peo ple visit each year. Visitors can access the arboretum via canoe, like the one below from the campus Waterfront Activities Center.

“There’s a history of colonialism,” Owen says. “That is the bedrock on which we’re standing. Plants and collections that exist throughout the world were collected in ways that did not honor the people and did not honor the plants themselves.” Along with the land and the plants, this legacy has come with the many gardens that were gifted to cities and universities.

The UW's gardens have plants from around the world. In the Pacific Connec tions Garden in the Washington Park Arbo retum, for example, visitors can view plants collected from Cascadia, Australia, China, Chile and New Zealand. “It’s important to be intentional and thoughtful about these plants and places, how they’re collected and grown and the meaning to the people that are from there,” Owen says.

How to address that and make the gar dens more inclusive is the challenge for the University’s Botanic Gardens department. When Owen came to the UW in 2021, the

The recent speaker series addressed topics like engaging with local Indigenous communities, developing youth leadership, creating job-training programs and finding opportunities for public land to support ur ban food systems and BIPOC communities. It culminated in September with a town hall to explore a new vision for how public gardens can serve their communities.

“We’re learning a lot about the priorities of the communities that we want to con nect with,” says Jessica Farmer, the adulteducation supervisor for the gardens. Un derstanding and responding to those prior ities will help build relationships, she adds.

In early October, the outreach contin ued with the Urban Forest Symposium, which brought tribal leaders and tribal ecologists together with UW scientists and state resource managers. This year’s event, which was held at —Intellec tual House, focused on bridging the gap be tween tribal practices and local government.

“We’re looking at Indigenous people’s access to and role in the management of the local urban forests,” Farmer says. “We’re looking at an identity shift for our organization, but we need to hear from oth ers in the community and not have it be an insular conversation.”

Studies show that students who feel a sense of belonging—of being connected to community, place and purpose—are more likely to thrive in college and experience better personal wellbeing.

Fall quarter started out strong for Fatima Gbla, a junior pursu ing a degree in molecular, cell and developmental biology. With classes, good friends, several student clubs and an advisory role in the Office of Minority Affairs & Diversity, she was on the go. She even attended the groundbreaking for a new campus building.

But in her first year, Gbla struggled to feel at home at the UW. Her challenge was rooted, in part, in not immediately finding oth er Black and African students. And she still deals with the sense of being an outsider.

“I often feel out of place in terms of how I am perceived and understood by my classmates,” says Gbla, whose family immigrat ed from West Africa. “Even if I might be included in things like group discussions and clubs, I often lack the feeling that I actual ly belong in that space.”

That feeling of not belonging—not being at home in the uni versity—is one that “has been most frequent among minority students that I have encountered,” Gbla says, “especially within STEM classes, where your intelligence and effort is tested the most as you are pitted against students who have had more access to quality education and resources.”

Few people walk into a university for the first time and feel like they belong. And for some, particularly underrepresented and non-traditional students, the feeling can worsen during their first weeks or months on campus. Since the late 1960s, universities across the country have worked to increase access and diversity for underrepresented students and faculty. The concept of DE&I (diversity, equity and inclusion) became a core focus in academia. But now the UW and other schools have expanded DE&I work to prioritize belonging—to make campus a place where individuals feel invited to be themselves. Where they are accepted, included and—like Gbla in her advisory role—engaged.

For her part, Gbla worked to root herself in a community of peers, which she discovered in the Black Student Union and the African Student Association. “Initially, I was a bit fearful opening up to members of these clubs, since I was so used to feeling like an outcast,” she says. “However, once I was able to understand that these students had similar experiences and could relate to me in a way that no other student could, I finally began to feel as if I found my own community, which led me to finding my own identity beyond what I felt I was labeled as.”

Belonging is a concept that psychologists started exploring in earnest in the 1990s. The idea is that belonging is a human need, like food and shelter, says Professor Sapna Cheryan, a social psy chologist and director of the UW Stereotypes, Identity & Belong ing Lab. People need to belong to thrive. That sense of belonging may be affected by the way the university interacts with facets of their identity, Cheryan says. It could be in the way classes are de signed, or even in the spaces where they’re taught.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, academia started to see the relationship between belonging and student well-being and en gagement. In 1987, the UW started a First-year Interest Group program that created small communities of students who shared academic interests and took classes together, with the idea that they would provide community for one another.

“We know that being at an institution where you feel safe and embraced is critical to student success,” says Denzil Suite, vice president for Student Life. “There is ample research that shows that students who feel connected to campus, who feel a sense of community and who participate in organized activities fare much better academically than those who feel isolated.”

Today, efforts to build student belonging at the UW start before admission. Shades of Purple, a summer workshop, brings hun

Fatima Gbla, a junior, didn't feel like she belonged when she started at the UW, particularly in her science major. She found a com munity of peers, though, through the Black Student Union and the African Student Association. Now she's a member of the First Year Experience Advisory Council.

Isabel Corona-Campiz didn't feel fully at home as an environmental studies major. She added a second major in ethnic studies where she found classmates and teach ers with whom she could more easily relate. Now a senior, she has a job at the Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center that allows her to support other students as they create clubs and events that make the UW more inclusive.

dreds of high school seniors from underrepresented communi ties in Washington to explore campus together and learn about the admissions process.

Another key moment comes at the beginning of the school year. A week after classes start, students are invited to commu nity welcome celebrations at the Kelly Ethnic Cultural Center (ECC). Some events are centered on students from specific cul tures and ethnicities including Alaskan Native/American Indian, Asian/Asian American, Black, Latine, Pacific Islander and undoc umented.

But there’s a difference between talking about belonging and changing a place like a university where the buildings and class es had been designed with one particular type of student in mind. Schools try to counter this by reaching out to the students with messaging that they all belong. The problem, says Cheryan, is that institutions that spend too much time reiterating that "you be long" can cause students to wonder whether they actually do. In stead, schools need to look at all their structures and systems— even how they build classrooms and residence halls and how they approach their subjects—and adapt them to serve the students of today.

“The sheer amount of white people in my classes was enough to deter me and [left me] just feeling scared to even ask ques tions,” says senior Isabel Corona-Campiz, a first-generation stu dent from Royal City. In her science classes, it seemed like the other students had already learned the content in high school, “and it was my first time hearing about it.”

In one of Corona-Campiz’s environmental studies classes, there was a focus on pesticides. The discussion centered on how the environment was affected, but Corona-Campiz thought the conversation should include people. She knew that agricultural workers, like those from her hometown, would also be affected.

Corona-Campiz decided to seek classes outside her major that offered content, students and faculty she related to. She ended up with an additional major in ethnic studies. It deepened her con nection to the pockets of home she found on campus, she says. “I feel like I belong there because I feel like that group of people is generally involved in other things. They’re also at the ECC or also use different resources under the OMA&D umbrella,” she says.

“Ethnic studies is more of a community-based major. For the past three years I’ve been seeing the same people over and over again, which is pretty comforting, especially at the UW, which is huge.”

It can go beyond just feeling comfortable in a space. Deep be longing includes a point of contribution, of being known, need ed and loved. In her junior year, Corona-Campiz found a job at the Kelly ECC, where she is the student leadership programs as sistant. She supports other students as they seek to develop pro grams and spaces that are inclusive to them.

Campus is one thing. Feeling like you belong in your field of study is another. STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) fields, for example, struggle to attract and retain Black, His panic and women students.

Cheryan’s lab studies belonging in fields including engineering and computer science. Stereotypes, she says, can dissuade girls as early as elementary school from even pursuing STEM careers.

What do students imagine when they think about what a com puter scientist or physicist looks like? The iconic leaders repre sent a narrow group of people, she says. They’re usually white men, people who grew up with a lot of privilege. They drink en ergy drinks, are obsessed with computers and like science fic tion. That’s problematic, because the stereotypes shape who as pires to be in these fields, Cheryan says. A lot of people don’t fit that image.

There is also the issue of “ambient belonging,” a term her lab came up with to capture the idea that a person can feel out of place based on what a classroom or laboratory looks like. In a more inclusive, gender-neutral space, it may be that a computer lab is decorated with plants instead of “Star Trek” posters.

Cheryan has seen where changes in cultural practices, expand ing the way people interact and showcasing new role models can go far in making a class or program feel more inclusive.

While masculine stereotypes for fields like computer science start early and are pervasive, it’s not too late when you get to col lege, Cheryan says. As computer science departments around the country are changing their cultures to be more welcoming and in clusive, they are building a more diverse faculty. As a result, more women will graduate in that field, she says.

The UW’s ADVANCE Center for Institutional Change is at the heart of some of those improvements. The center was start ed in 2001 with a $3.75 million grant from the National Science Foundation and focuses on addressing the underrepresentation of women faculty in science and engineering. If the adage “You can’t be what you can’t see” has any truth to it, Joyce Yen, the pro gram director, and her team are working to make sure women stu dents and faculty can see women thriving in powerful places in STEM fields. “There is power in community, even a community of just two,” Yen says. “It’s not solely up to individual students to solve these issues for themselves. But if the structures and sys tems are not yet meeting these needs, then we can still create community for ourselves.”

Professor Cheryan is part of that community of UW women faculty. “We have been meeting every other week, sometimes more, since 2008 as a peer mentorship group,” she says. The group helps the professors navigate their departments, the uni versity and the tenure process.

Cheryan’s insights on stereotypes, identity and belonging can also be seen at work in her own lab. Her students help define the ways they want to be together. They organize meetings outside of the lab and interact at cafes, happy hours, dinners and boba out ings. “We share a desire to do research that helps the world, and the people in the lab are not only great researchers but also great people,” Cheryan says.

While the University’s focus on belonging includes undergrad uates, staff and faculty, one group that often gets overlooked is older students. Margaret Lundberg, for example, had not taken a college class since 1975. When she returned to finish her under graduate degree at UW Tacoma in 2009, she felt out of place. She describes being in the Dawghouse Student Lounge, with its vid eo games, pool tables and loud music. “You know every moment that this place just wasn’t built for you,” she says.

Lundberg coped by swapping stories with other returning stu dents. One of her challenges was figuring out how to write for school again. She would get writing assignments and ask, “What is APA style? Do we still do footnotes?” Once she figured it out for herself, she took a job at the UW Tacoma Writing Center, where she could help others facing the same challenges. There she met a student who had to bring along her 7- and 9-year-old children to tutoring sessions. She couldn’t afford child care and told Lund berg that she was about to become homeless.

This was hardly the first time Lundberg had heard of a return ing student dealing with crisis-level hardship. “I’m hearing them,” she says. “Is anyone else hearing them?”

She decided to investigate and enshrine the rarely studied top ic into academic literature. She focused her 2022 doctoral disser tation on women who return to complete their degree after the age of 35. Her research included interviewing eight older women returning as students. Lundberg found that once a student finds her community within the university, she develops a renewed en ergy to finish her degree and encourages others to do so too.

Of the eight students Lundberg interviewed in depth and iden tified by pseudonym for her dissertation, five were not white. One was a Native American woman [Omaha, Nez Perce and Win nebago] in her 50s who returned to the UW for her master’s in social work. She and her husband were also raising two grandchil dren after their daughter died of COVID-19.

Being Indigenous, the woman knew she was out of place in

Professor Sapna Cheryan, an expert in social psychol ogy, explores stereotypes, identity and belonging. Among the questions under investigation in her lab are why women are under represented in STEM, how identities interact and how to address institu tional racism.

academia and how few—historically less than 1 percent—Native Americans complete graduate degrees. She felt she always had to prove she deserved to be on campus. But she found belonging in the UW Tacoma library. There the staff treated her like a research er and she began to see herself as part of a community of scholars. “It was a place that made me feel like I belonged and felt worthy of being at a university,” she told Lundberg.

She might not have finished her degree after her daughter died, but one of her professors showed insight and compassion, giving her extra time to complete her work and the feeling that she was cared for. He told her: “Don’t worry, I will get you through this.”

Now the woman has advice for anyone struggling with belong ing. “First thing, you’ve got to believe what people say to you, es pecially when they’re good things,” she told Lundberg for her re search. “And you hold on to it, and you take it in like a sponge and don’t wring it out. You hold on to it until it becomes part of you and then you can release it to let others know. To tell them about the thing that’s positive about them.”

Lundberg concluded her dissertation with these parting words: “Universities are coming to understand that they can—and in deed, must—revise themselves to be more inclusive of a wider range of student identities. This is the purpose of campus diver sity programs like the Center for Equity and Inclusion, like firstgeneration support groups and veterans’ services; and I would suggest that this attention be extended to include mature return ers as well.” —Hannelore Sudermann contributed to this story.

the story of diversity at the UW

rector at the Wing Luke Museum—to re trieve plants left behind by a friend who was hospitalized. “I’d never seen so many flowers on a hoya carnosa [also known as a porcelain flower],” she says. It seemed like a beautiful but terrible omen. “We weren’t sure if [the coworker] was going to make it,” she tells Pai, her voice drop ping low. Rubenacker decided that sav ing the plant would be her way of fighting for her friend’s life—if the plant survived, hopefully her friend would too. And it did. And she did.

Another episode focuses on a chador, a full-body cloak worn by some Muslim women. This particular chador is red and covered with sequins, a creation of Anida Yoeu Ali, now a teacher and artist in res idence at UW Bothell. The story of Ali’s performance art explores the concept of clothes and identity.

The chador’s story starts with Ali’s pre paring to participate in an art exhibit in France where the burqa is banned by the

In her new podcast, “The Blue Suit,” poet Shin Yu Pai uses everyday objects to tell unique stories

By Manisha Jha

By Manisha Jha

A podcast featuring Asian American sto ries launched with eight episodes this summer. Many of the guests who share their stories with host Shin Yu Pai are con nected to the UW as former students, alumni and faculty.

Shin Yu Pai, a poet and UW museology graduate, ’09, whose creative career has spanned continents and forms, has taken on podcasting as her newest mode of sto rytelling. In “The Blue Suit,” she explores the stories of cherished everyday objects from Americans who were children of the Asian diaspora. The objects include plants, miso, a piece of vitrified glass and, as you might expect, a blue suit.

The show, which is produced through KUOW and edited by Jim Gates, started broadcasting in July. In an early episode, Pai introduces one of her own beloved ob jects, a favorite childhood toy in the form of a 1974 stuffed animal, a Dakin Drooper

dog she once carried everywhere and that her mother often lovingly repaired. The stuffed animal is a reminder of the good parts of her childhood, of being raised by immigrant parents who took pains to make her feel safe and loved.

While the podcast's objects are com monplace, they're imbued with deeper meanings. In another episode, a plant be comes a way for Jessica Rubenacker, ’09, to connect with a sick friend at a time of social distancing. “Some plants, when they are under severe stress, will flower. It’s like their last-ditch effort to continue on,” says Rubenacker. She went into her pandemic-closed office—she is exhibit di

government. Ali, a Muslim woman with Cambodian roots, knew her participation in the exhibit would involve a covering. She created one that was hard to miss—bright, sparkling and provocative. Her perfor mance involved wearing the “Red Chador” in spaces where she could be seen. The chadors are extensions of identity and an cestry.

Ali walked through Paris, visiting land marks and stopping on corners, often touching her heart before extending both hands to others. People she encountered reciprocated. “They do see me, and they’re acknowledging this moment of exchange,” she tells Pai. The message of the chador is one of unapologetic Muslim identity, she explains. In some people it stirred anger or confusion, in others it brought smiles and sincerity. In herself, “it brings out a play fulness and a joyfulness,” she says.

Another episode focused on taste, smell and memory. Tomo Nakayama, a Seattle musician who studied at the UW in the 1990s, took up cooking in the early days of the pandemic to cope with the loss of live audiences. For him, the smell of miso is an avenue to a different place and time: the umami in the air of his birthplace, Ko chi, Japan. “Umami … uh, what is umami?”

The objects are lures to get people to listen and normalize the stories of Asian Americans

he says, laughing, struggling to think of a direct translation in his conversation with Pai. He decides it is the depth of flavor, the complexity, “the thing that lingers on your tastebuds.”

Nakayama grew up in the U.S. and of ten woke to the smell of miso. He contrast ed this with how he felt at school when his classmates would turn up their noses at the unfamiliar smell of his homemade lunch. Now, the scent makes Nakayama long for the home of his childhood.

Sometimes the objects Pai explores with her podcast bring up feelings of homesick ness for people who are no longer around. When she speaks with composer Byron Au Yong, ’96, she learns about the pa per objects he made with his father’s ma terials. Helping care for his ailing father, Au Yong started making folded art out of old business magazines, insurance paper work, and chemistry and engineering text books. He saw layers of his father’s identi ty in the pages. They were things his father had touched and held many times; that it self was sacred to Au Yong and worth pre serving.

The impetus for the podcast came about in the greater context of the pandemic, as Asian Americans—like everyone—faced prolific disease, disability and death, Pai says. Then members of America’s Asian communities experienced a spike in vio lent racism, as President Trump and other high-profile leaders referred to COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus” and “kung flu.”

Pai says the objects she highlights are really lures to get people to listen to and normalize the stories of Asian Americans.

“The objects aren’t the point,” she ex plains. “The point is our connections with our past.”

Pai was inspired to make objects the fo cus of her podcast after she saw viral pho tos of Rep. Andy Kim, D-N.J., on his hands and knees, cleaning up debris in the Capi tol rotunda after the Jan. 6, 2021 riot.

Kim, a child of Korean immigrants, had bought a blue suit on sale at J. Crew to wear during the certification the presidential election results. Instead, after barricading in his office with his staff for eight hours as they waited for the riot to end and the Cap itol Building to be secured, he walked back to the Rotunda filled with broken glass, gar bage, bottles and cigarettes people had put out on statues. “I felt my heart breaking,” he told Pai. He found a roll of trash bags, got down on his knees and spent the next hour and a half cleaning up the debris.

He wore the suit again a week later—to vote for the impeachment of Trump—dust still on his trousers.

The suit later found a home in the Smithsonian National Museum of Ameri can History, which was collecting artifacts from that infamous day. At first, Kim had wanted to throw it away. “It just brought

‘Water Birth, The Red Chador: Genesis I,’ Performance and Con cept by Anida Yoeu Ali. Ali is a senior art ist in residence at UW Bothell. She shares the story of her work in an episode of the “Blue Suit.”

back such terrible memories.” He recalls the Confederate flags brought into the Capitol that day—a symbol of slavery and white supremacy that had never before been inside the building. “What does it mean to be American right now?” he asks Pai. But now he sees the value in giving the garment to the museum.

When they’re older he hopes to take his sons to visit the suit and tell them, “When something you love is broken, you fix it.”

�he eight-episode first season of “�he Blue Suit” is available from KUOW, NPR. com and Apple Podcasts.

the story of diversity at theLawney Lawrence Reyes, ’59, was an artist, author, activist and an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and the Sinixt Band, and of Filipi no descent. He started life in Bend, Oregon, spent part of his childhood on the Colville Reservation.

His parents opened a Chinese restaurant in Grand Coulee to feed the workers there to build the Grand Coulee Dam. He had a front-row seat to the massive public works project that would eventually inundate his family’s hometown of Inchelium.

When his parents divorced several years later, a judge sent Reyes and his sis ter, Luana, to boarding school at Chemawa Indian School near Salem, Oregon. They were there for two years. He learned about different Native communities from the other children and started drawing and painting. After two years, Reyes and his sister returned to their father in Eastern Washington and moved around with him as he sought work.

As a young adult, Reyes earned a degree at Wenatchee Junior College before mov ing to Seattle to attend the UW in 1952. A health issue caused him to miss the start

of his junior year, so Reyes instead enlisted in the Army, which took him to Germany for a few years. From there he explored other countries before returning to the UW to complete his degree in interior design in 1959. He worked as a designer for Seattle First National Bank (later Seafirst) and also started his profes sional art career. During the 1970s, he codesigned the Daybreak Star Indian Cultur al Center in Seattle, a resource for urban Indians made possible by activism led by his younger brother Bernie Whitebear. He also became the art procurer for Seafirst Bank, helping develop the corporation’s fine art collection.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Reyes created sculptures and public artworks throughout Seattle. He received numerous awards for his art. In retirement, he became an author. His writing includes “White Grizzly Bear’s Legacy: Learning to Be In dian” and “B Street: A Gathering of Saints and Sinners,” both published by UW Press. He also wrote about his brother in “Ber nie Whitebear: An Urban Indian’s Quest for Justice” (University of Arizona Press). Reyes died on Aug. 10 at the age of 91.

Dave Barnett, ’84, started running as a little kid and never slowed down, winning every race he ran in high school and most he entered at the University before set ting a scorching pace in life and service to the Cowlitz Indian Tribe.

The general council chair man for the Cowlitz Tribe had a history of service. He helped the Cowlitz Tribe open the Ilani Resort & Casino and move toward a number of social and cultural goals. He died unexpectedly on May 28 of a heart attack at the age of 64 at his home in Shoreline. The tribal news release an nouncing his death listed a number of initiatives that Barnett was actively work ing toward at the time of his death. “If you measure length of life by how fast a guy moved, he outlived us all,” Cowlitz Chief Operating Officer Kent Caputo told The Seattle Times.

Barnett was the son of John Barnett. The two helped guide the Cowlitz to federal

recognition in 2000. Barnett was elected chairman in 2021.

Barnett had also worked on a project with The Lan guage Conservancy to help revitalize the tribe’s language and implemented vote-bymail elections. He worked to ensure all tribal members received equal distribution of COVID-19 relief funds and universal health care, and sought equal distribution of casino earnings.

Barnett attended the UW on a scholar ship after one of the most distinguished high school cross country and track ca reers in state history. He was a high school all-American after winning every race he participated in during his junior and se nior seasons at Aberdeen High. He won more than 20 races at the UW, turning in a 1-mile time that remains one of the fast est in school history, and participated in the NCAA championships.

He earned a degree in communications and media studies.

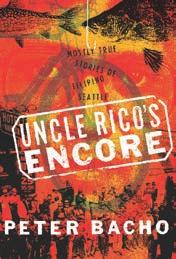

Peter Bacho, ’74, ’81 University of Washington Press, May 2022

UW Law alum Peter Ba cho is an American Book Award-winner for his work exploring themes of Filipino American ex perience and identity. His 1991 novel, “Cebu,” brought his engaging and insightful storytelling into national view. Now he has crafted a memoir that opens views into the lives of those of Fili pino descent who landed in or grew up in Seattle. The stories of love and resilience unfold in the Central District, the China town International District and Rainier Valley from the 1950s to the 1970s. His ma terial spans Alaska cannery workers, union activism, memories of family, community and his own childhood.

We Had Our Reasons: Poems by Ricardo Ruiz and Other Hardworking Mexicans From Eastern Washington

Ricardo Ruiz, ’20 Pulley Press, May 2022

Though he came to the UW to study business, Ricardo Ruiz was drawn to creative writing and found his calling. As an intern with Frances McCue, a teaching professor who was starting a new poetry imprint for Clyde Hill Press, he helped de velop the imprint’s focus to discover and encourage poetry from rural America. The Pulley Press imprint seeks poems and po ets from the less-visited parts of our coun try, “beyond bright, shining cities.”

That editing and publishing experience, along with his own interests and talent, led to a book contract with the new press to develop “We Had Our Reasons.” The collection draws upon Ruiz's own ex perience as a first-generation Mexican American growing up in Eastern Wash ington and the stories shared with him by members of his community. The po ems, in Spanish and English, come with biographies and details that highlight the people whose voices he shares.

An illustration of a handwashing device from “The Book of Knowledge of Inge nious Mechanical De vices” showing one of the world’s earliest robot inventions. The 12th century inventor, Ismail al-Jazari, in spired a professor and his student to write a children’s book.

In their new children’s book, “Robots and Other Amazing Gadgets Invented 800 Years Ago,” Professor Faisal Hossain, an expert in hydrology, and Qishi Zhou, a graduate student in engineering, explore the work of a 12th-century scholar, artist and engineer who is considered the “fa ther of robotics.”

The book, published this month by Mascot Books, explores the origins of eight of Ismail al-Jazari’s inventions. They include a four-cycle gear system, a bloodmeasurement device, an elephant-shaped water clock and a robot that helps wash and dry hands.

Hossain first learned about al-Jazari’s work a few years ago in the long-ago in ventor’s own compilation, “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.” The genius and variety of his inventions, conceived during the Islamic Golden Age, amazed the UW professor. Zhou and Hossain met when the

student was participating in the Col lege of Engineering’s industry capstone program. Zhou's team was creating a remote-controlled culvert inspection ve hicle under Hossain’s guidance. The two connected over water issues and a shared desire to serve the community of work ers who focus on water for research, in dustry, policy, planning and utilities. For the project, they trained their efforts on developing robots and gadgets to solve societal problems and improve quality of life. “This was almost like a microcosm of what Ismail al-Jazari did 800 years ago when he used automation to create tools to improve quality of life,” Hossain says.

They decided to jointly tell the story of the 12th-century inventor and encourage children to engage with the natural world and explore technology there. “The natu ral world is a laboratory,” says Hossain. Harnessing how water works and moves, for example, was part of designing the first

robot. The message “we want our kids to take: Spend more time outside watching and learning from nature and less time with computers,” he says.

One of Hossain’s favorite al-Jazari in ventions is a robot that dispenses water for cleaning and performing ablution (a ritual washing). While the user is clean ing themself, the robot plays a flute-like sound and then hands over a towel. Ev ery sequence of the task is timed and organized.

Al-Jazari used water—hydrostatic pres sure and water physics—to drive his de vices. “It never dawned on me that such concepts could be used to drive automa tion and even build robots when there was no electricity,” Hossain says. “It just drove home the concept that water is as powerful and relevant as today’s electronics, com puters and information technology. This thought makes me feel quite proud as a hydrologist.”

diversity

Celebrating the inventions of the Islamic Golden AgeFREER GALLERY OF ART, SMITHSONIAN

This cycle of ghost stories is built around the mystery of a girl who has gone missing in rural Appalachia. The play is set in the structure of a Japanese Noh drama—where time shifts and ghosts appear—and in the location of a small southern town. In this haunting, touching play, Iizuka weaves a story of grief, loss, guilt and karma. Director Curtis-Newton is a professor of acting and directing and head of directing at the UW. She also oversees the Hansberry Project, a professional African American theater lab.

By Han Eckelberg, ’22 Odegaard Undergraduate Library

By Han Eckelberg, ’22 Odegaard Undergraduate Library

This new permanent art installation on the central staircase of Odegaard was created by Han Eckelberg while he was a UW un dergraduate in art and American ethnic studies. Eckelberg, now a graduate student, created the project for a class in 2020. It was embraced by his fellow students, winning Best Artwork in the 2020 UW Makers Summit. The piece pays homage to actor and martial arts legent Bruce Lee, who studied drama and philosophy at the UW in the early 1960s. Over the years, there have been sev eral attempts to recognize Bruce Lee on campus. Now the UW community is celebrating the permanent work. The library is a resource for UW undergraduates and is currently open only to those with a Husky Card.

Feb. 9, 2023

Location to be determined

Join an exciting evening with artist and activist Chuck D, the lead er and co-founder of the legendary rap group Public Enemy. Best known for writing and performing music like “Fight the Power” and “Don’t Believe the Hype,” Chuck D has expanded his activ ism, working with Rock the Vote, the National Urban League and Partnership to End Addiction (formerly known as Partnership for a Drug-Free America). UW alum Daudi Abe, an author and historian, will guide a conversation about culture, race, gender, communication and, of course, hip-hop. The event is hosted by the Graduate School.

In 1976, artist and UW professor George Tsutakawa designed and installed a set of bronze gates at the north entrance of the arbore tum near campus. In 2020, at the start of the pandemic, the origi nal gates were stolen and destroyed. But through public support and private donations, George’s son Gerard was able to re-create the works using his father’s original plans. The refabricated gates were completed this summer and installed in August, now in a more secure location close to the Graham Visitors Center. They are now part of the city’s permanent art collection.