The cover of Sotheby’s London Impressionist and modern art sale catalogue of February 2015 features Monet´s “Les Peupliers à Giverny’’. Sotheby’s has auctioned the work on Feb. 3 and it was sold for 10,789,000 GBP. This sale is particularly interesting because of the seller—the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The market is now so distorted and tilted toward contemporary art that 10 million GBP raised from the auction of a Monet is less than the cost of a large work by a contemporary art star like Andy Warhol, Gerhard Richter, Jeff Koons, and many others. Some works are considerably more than that. Is it really worth trading a Monet for a slice of Koons´s hanging locomotive?

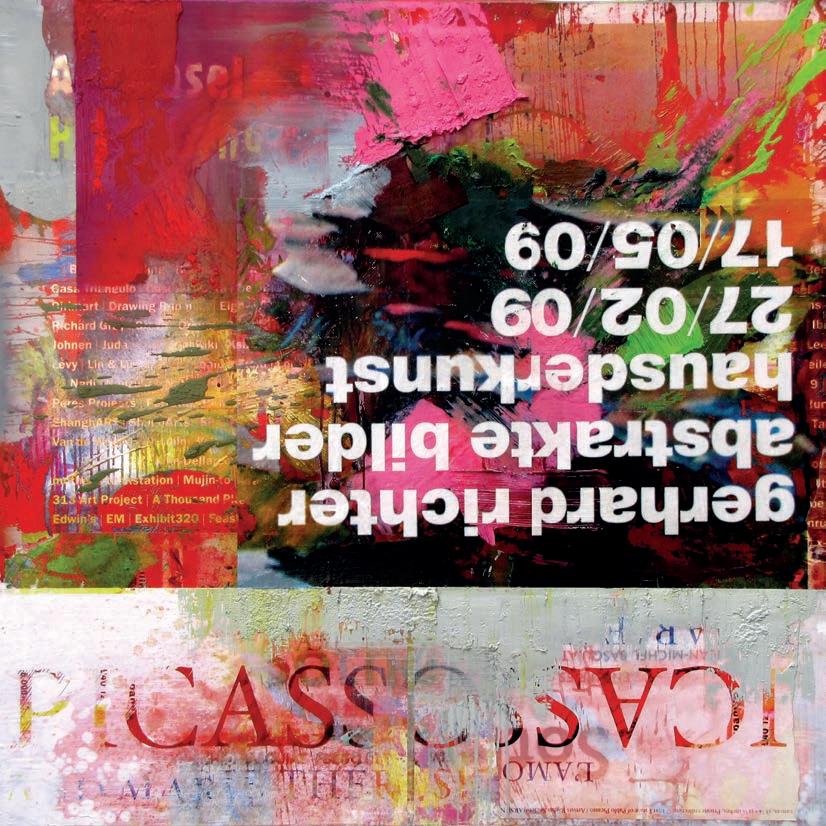

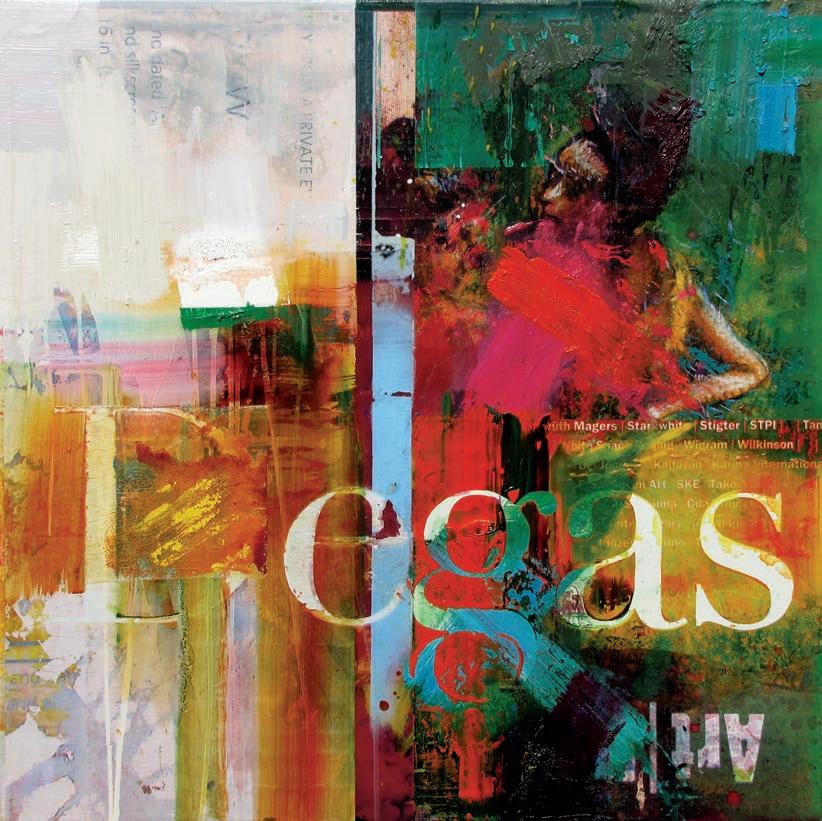

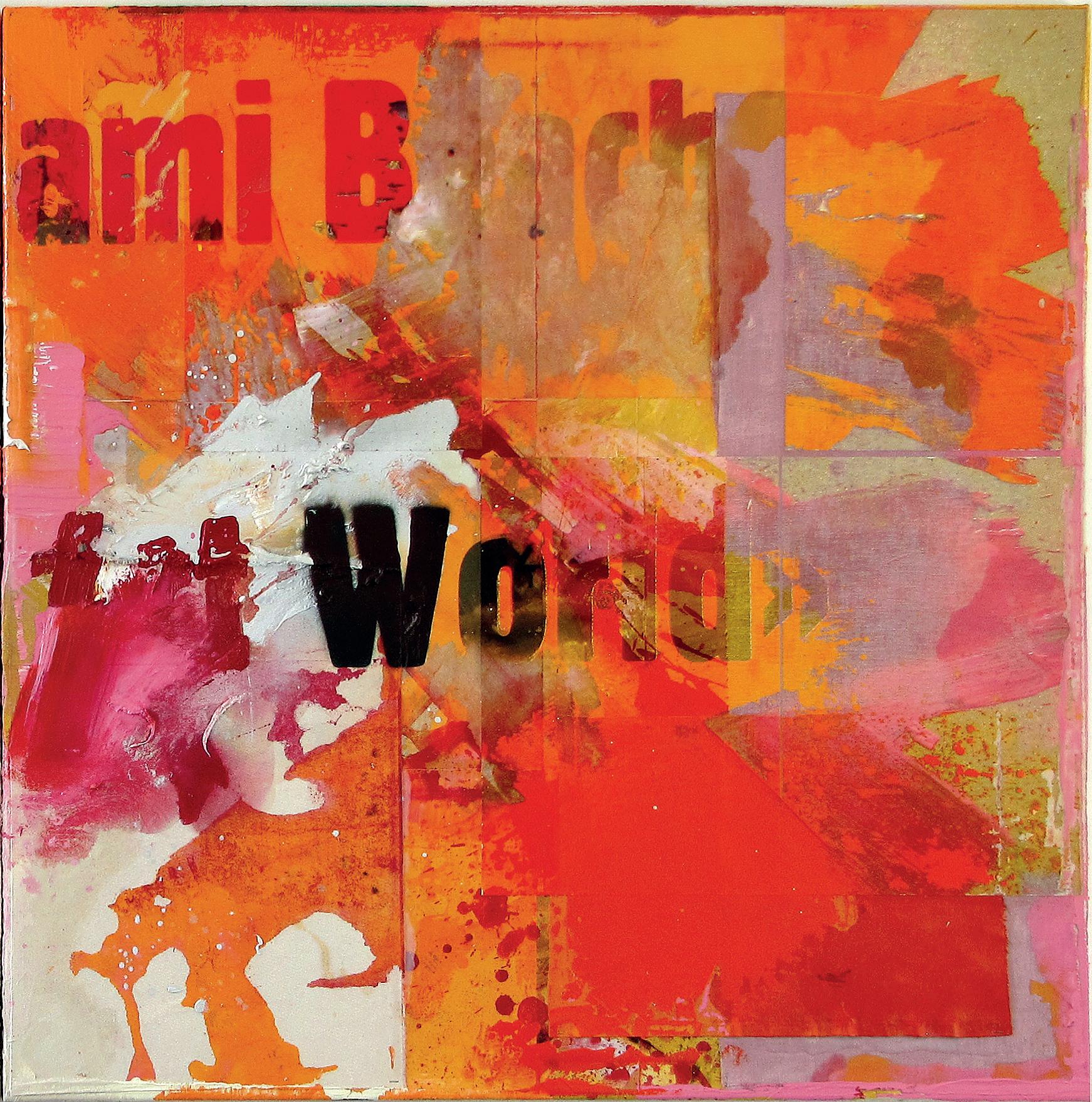

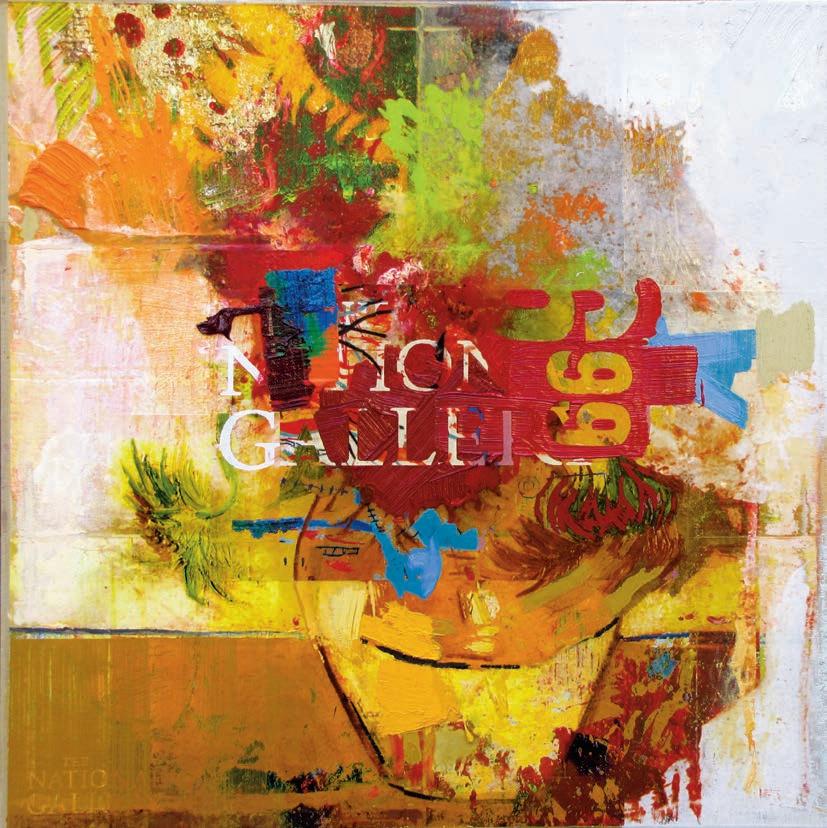

Since art and money go together like peanut butter and jelly, Peter Vahlefeld´s new paintings are the perfect metaphor for our twenty-first-century. One Century spent de-coding and re-constructing art history, a system so complex and contradictory in the hopes that something more than the sum of its parts might be communicated and devoted to emptying art of everything except what Karl Marx righteously called commodity fetish. As the English critic John Berger first argued in »Ways of Seeing«, oil painting as we know it is innately materialistic. The paint is a kind of material and when it is applied to canvas the result is an image that is essentially a kind of property that can be bought, traded, and moved from place to place—as well as photography, which has been associated with materialism since its invention. Despite its relative lack of physical presence compared to painting, photography serves to record the material reality in front of the lens. Historically, it is a product of our materialistic, industrial age. But today in our digital world—a world where everything is being instantly, infinitely and indefinitely reproduced—virtually anything from trash to home mortgages to art, may be monetized, in other words exchanged on an international market in an abstracted representational form. By treating digital prints in the same manner as painters treat canvas, Peter Vahlefeld tends to dematerialize both mediums, focusing on the interface between analog and digital painting. He recognizes that works of art in a capitalist culture inevitably are reduced to the condition of commodity. What he does is to short-circuit the process and start with the commodity—he over-paints advertisements for international galleries, museums, auction houses, and museum shop merchandising that form the base of his paintings.

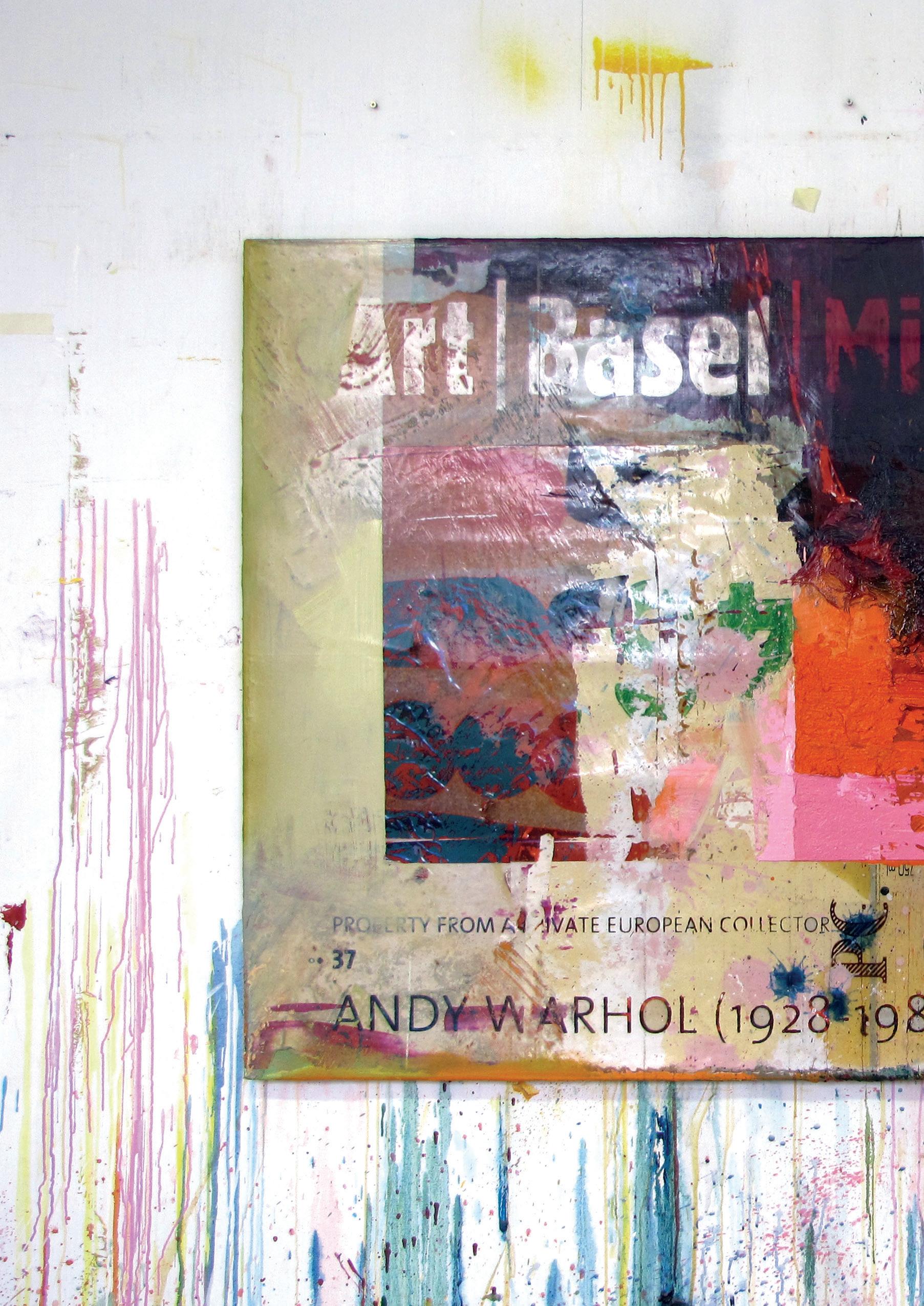

As it happens, the camera, the scanner and the computer have been comfortably assimilated into the practices of most contemporary artists. Peter Vahlefeld´s overpaintings of printed matter are scanned, over-painted again on his computer, before being transferred to canvas to be over-painted again, digitized again, and so forth, becoming a conceptual and formal construct, from the heterogeneous combining of elements. However, these works use technology rather than reflecting on digital visuality per se, hovering between the painted and the printed image, striving for something beyond both. Painting with photography and print and the refinement of modernist art with the vulgarities of mass cultural representation forces us to consider how we interpret

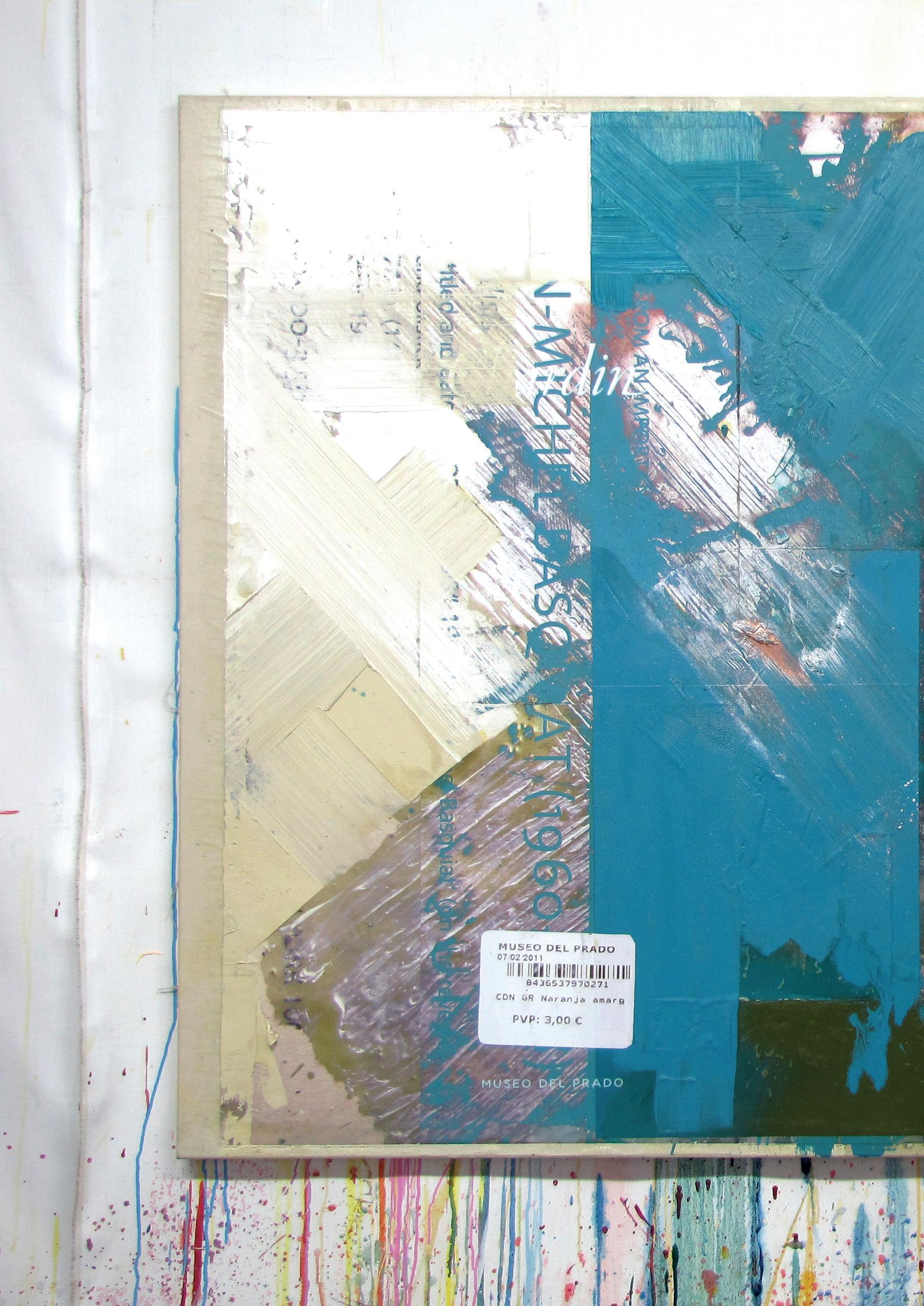

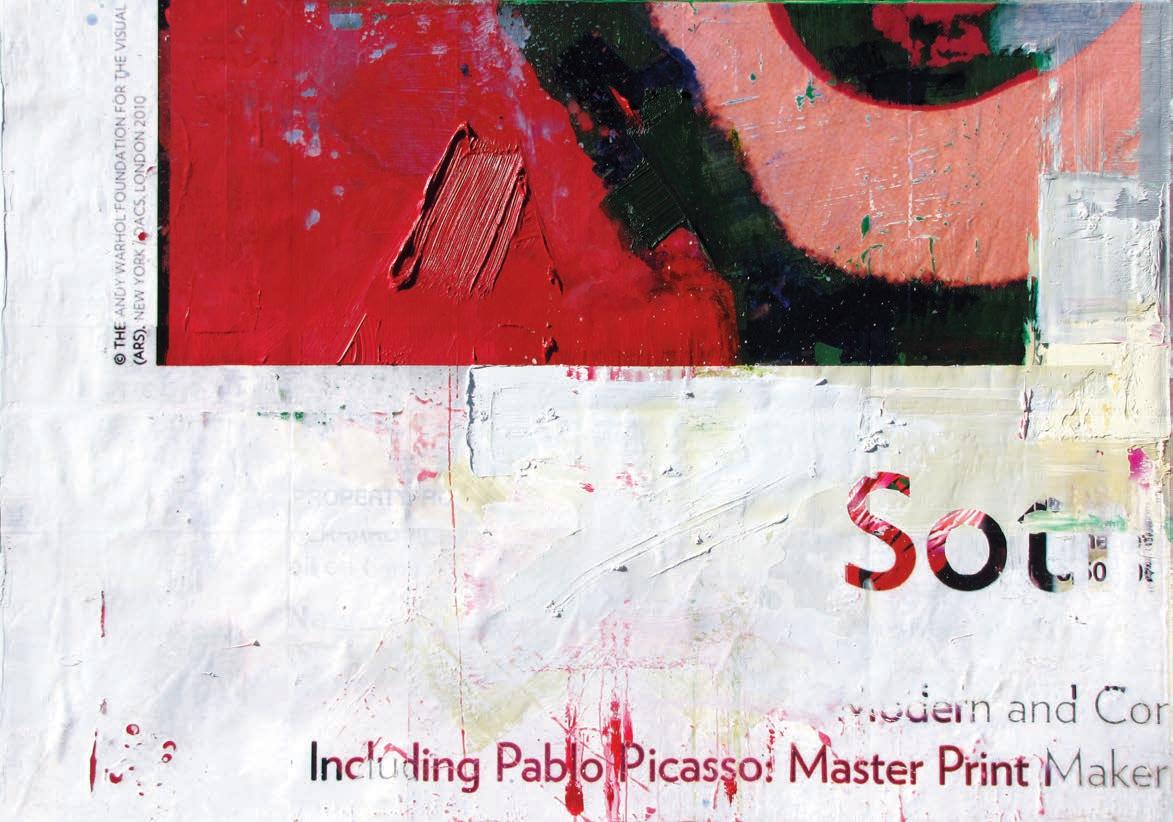

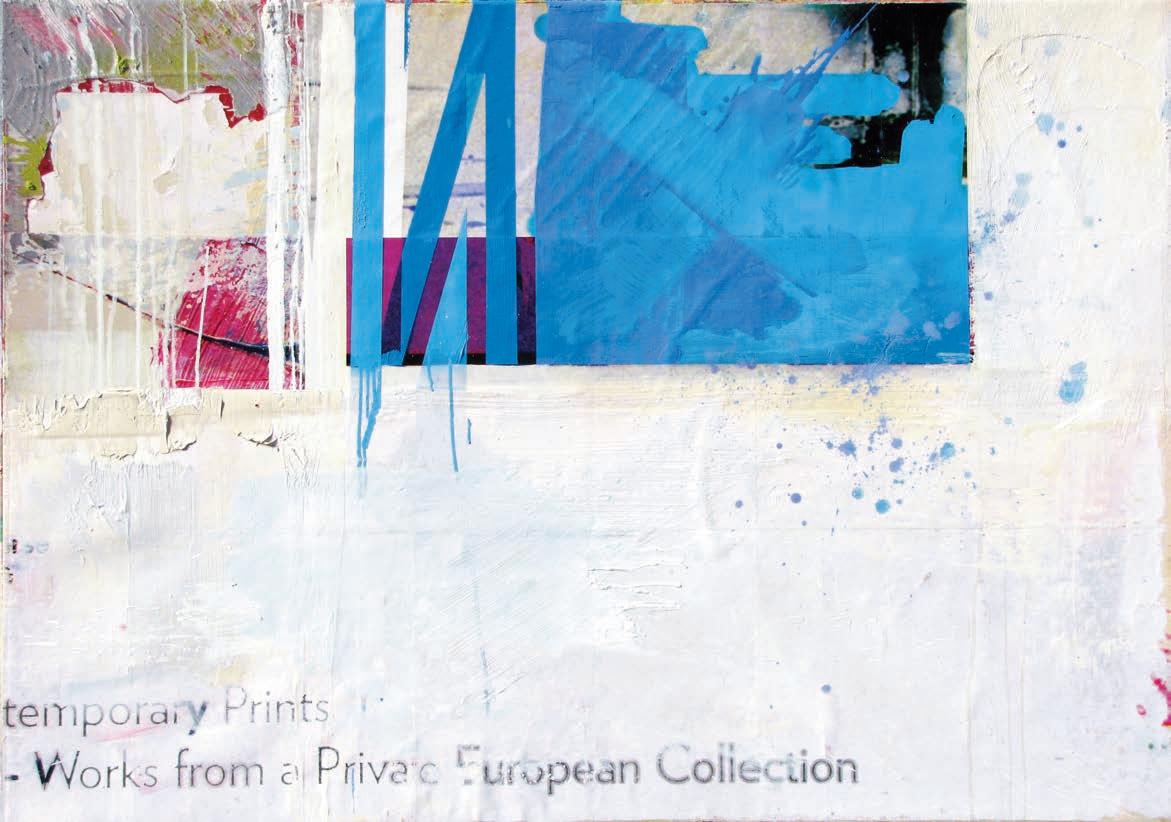

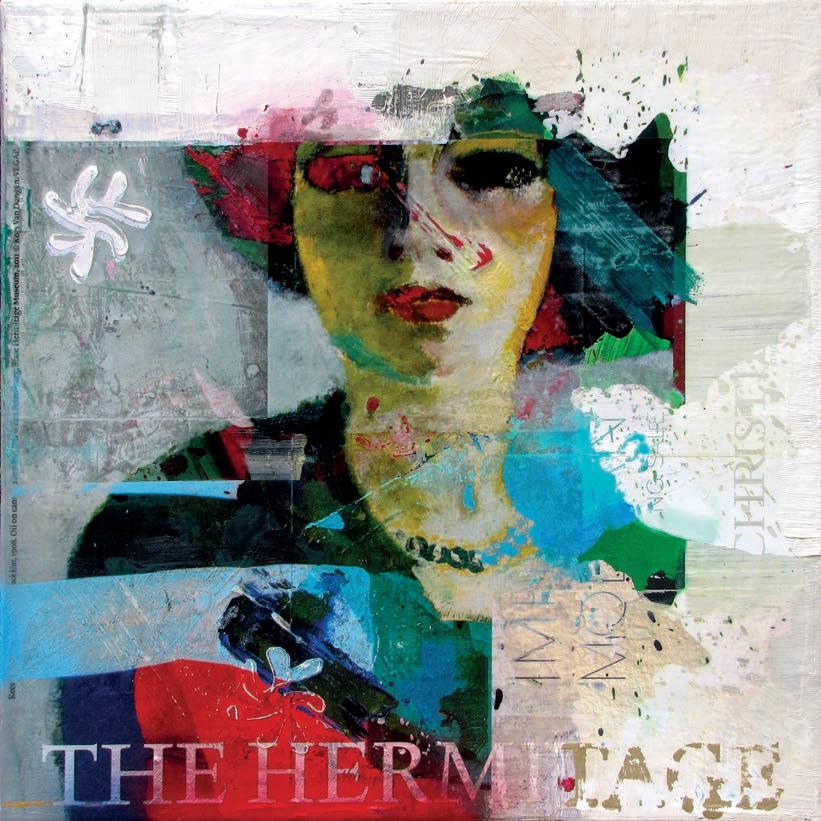

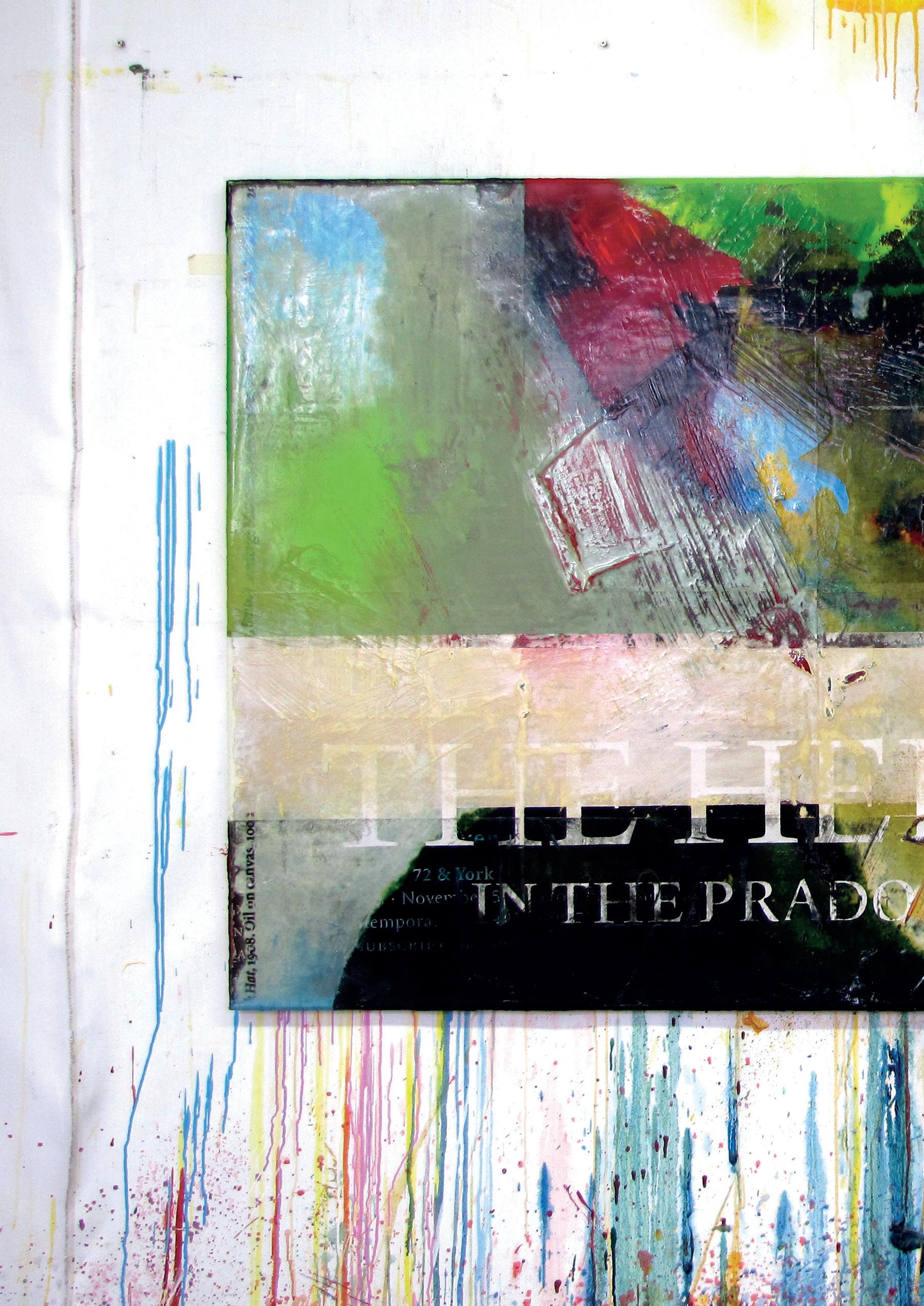

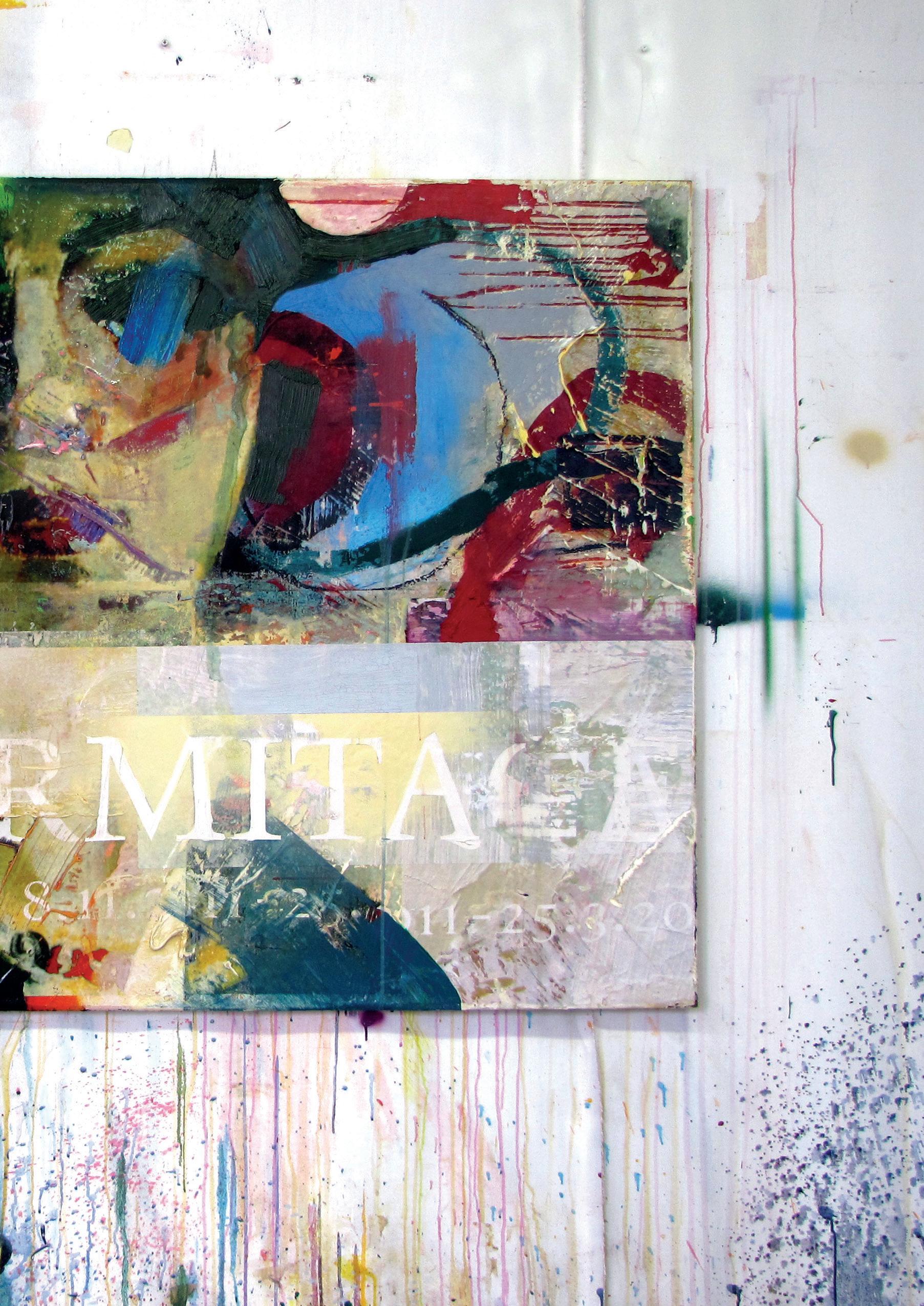

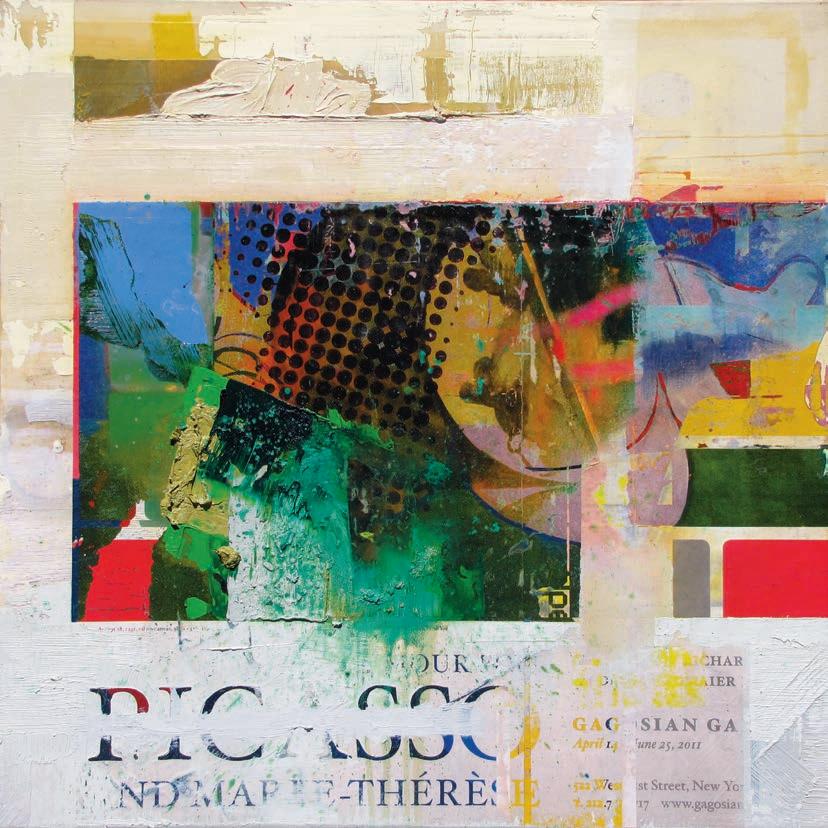

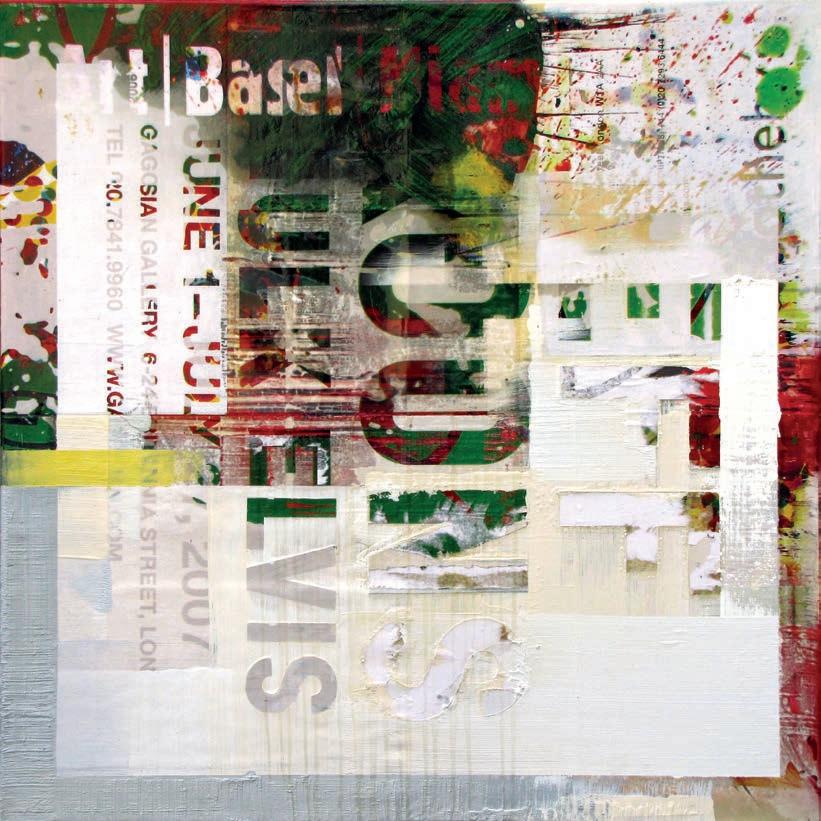

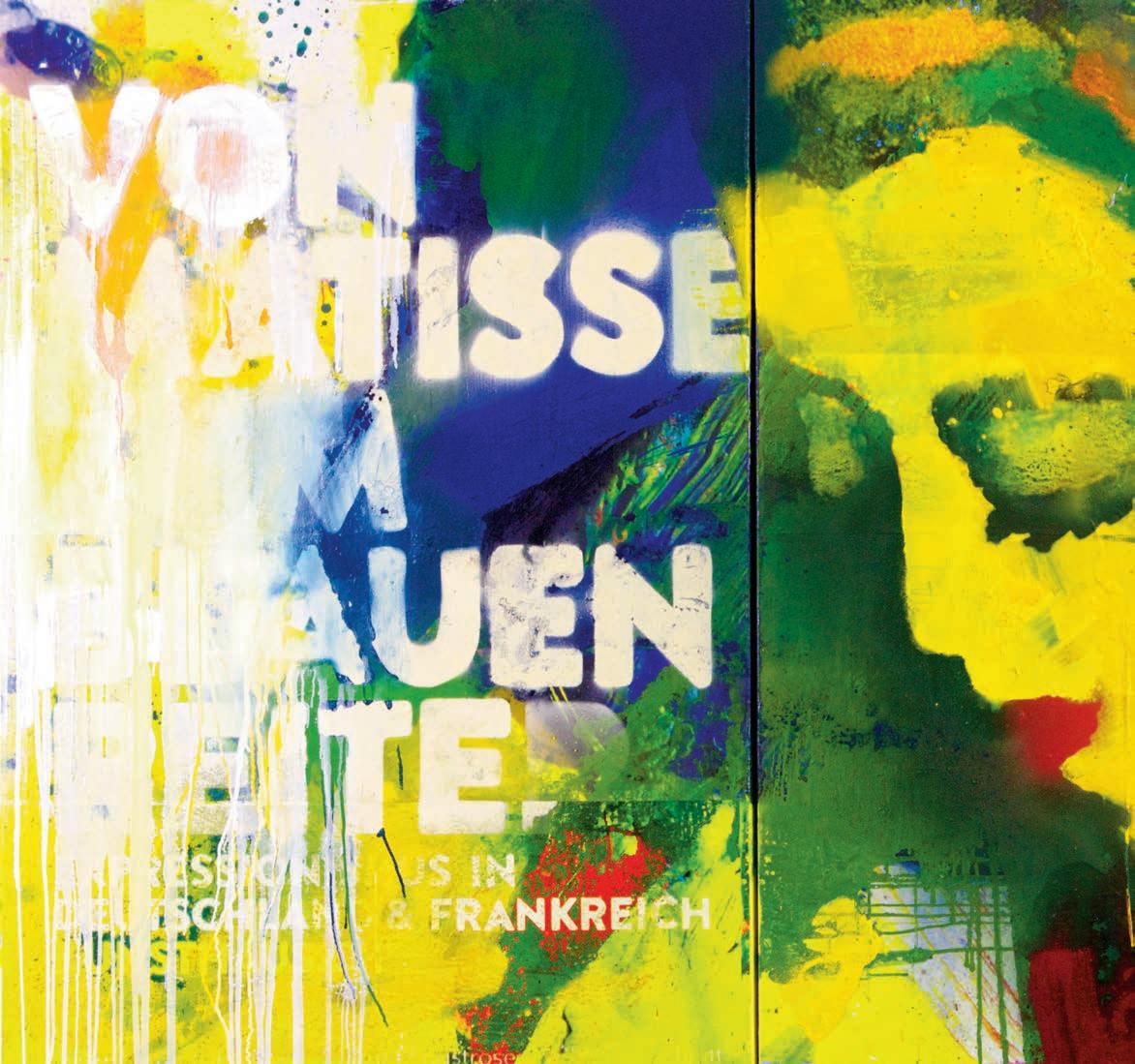

media and advertising. Do we accept mass media at face value, or do we view the world through coloured glasses? The history of art is being constantly rewritten according to the demands of the present, piecing fragments of the old together to form a visual language, which resonates with the contemporary consumer. Nothing coheres in a way that could be said to have substantive narrative dimension or pictorial legibility, except for visible stops and starts that prod the limits of content. We read snippets like »Hermitage«, »Museo del Prado«, »Chardin«, »Von Matisse zum Blauen Reiter«, etc. Other words are fragmented or superimposed to the point of eligibility. Traces of subtractions—the scraping off of layers of pigment—are as central to his process-based works as the scratchy lines of the sanding machine or the iridescent staining with heavy oil paint by the broom.

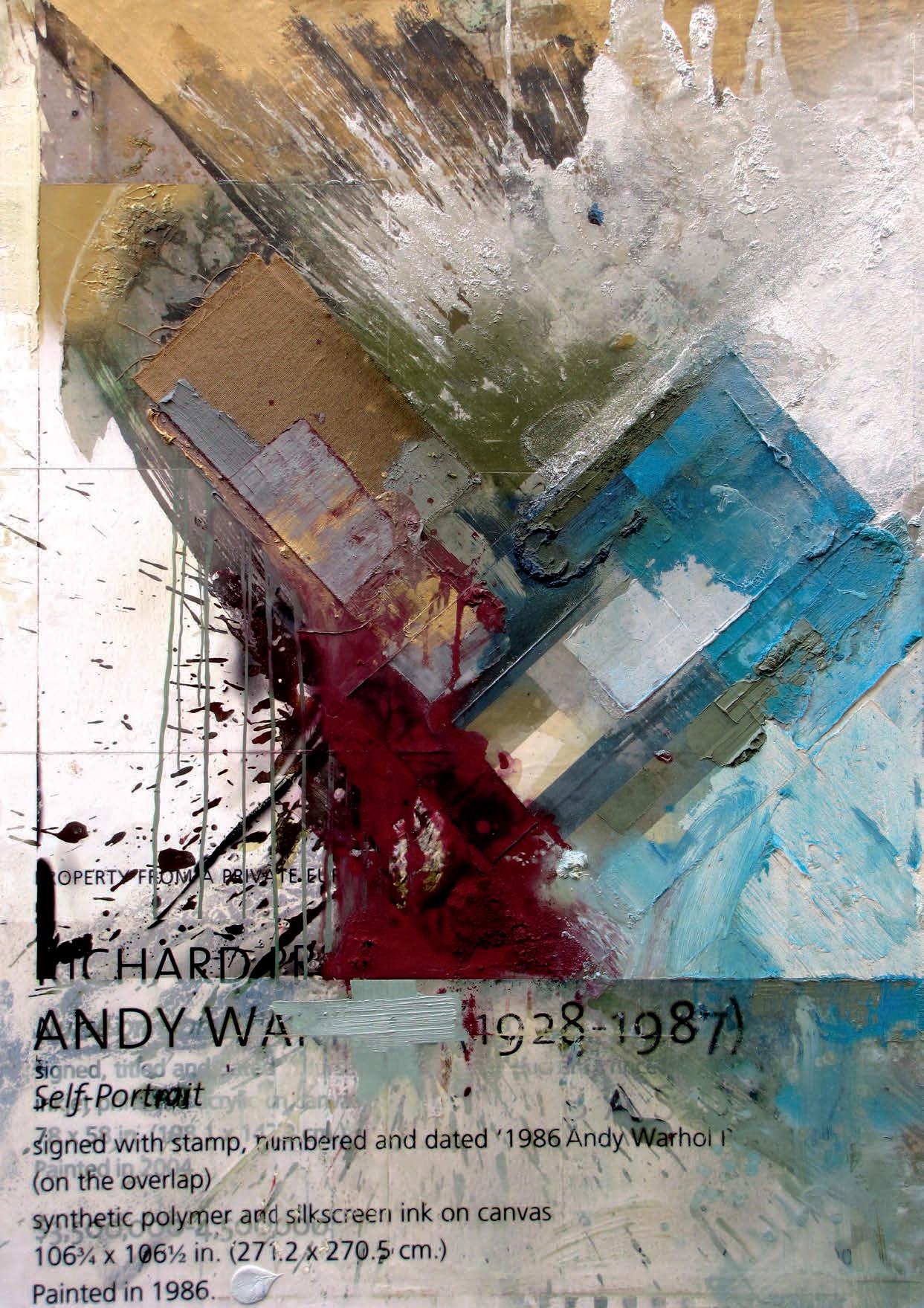

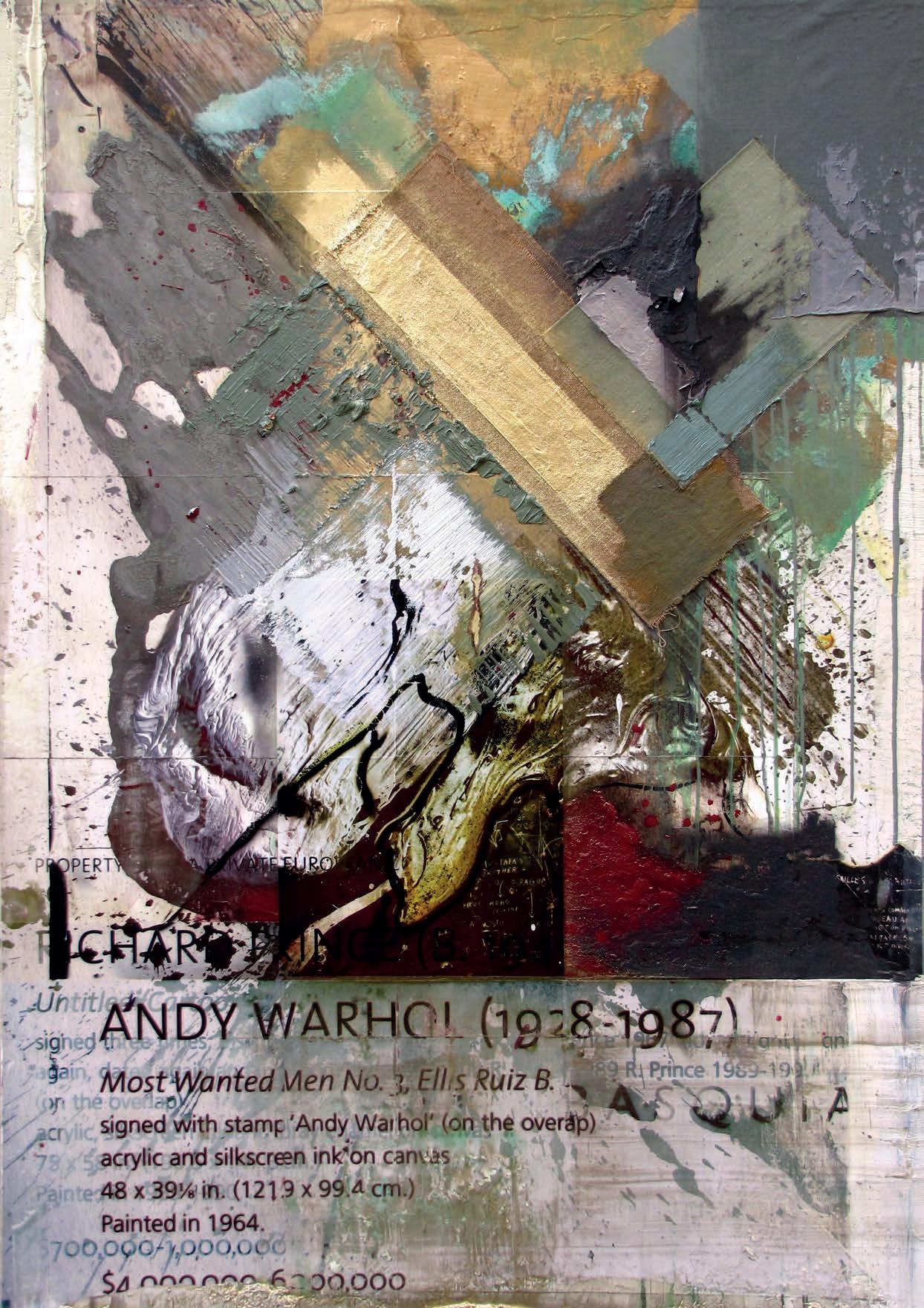

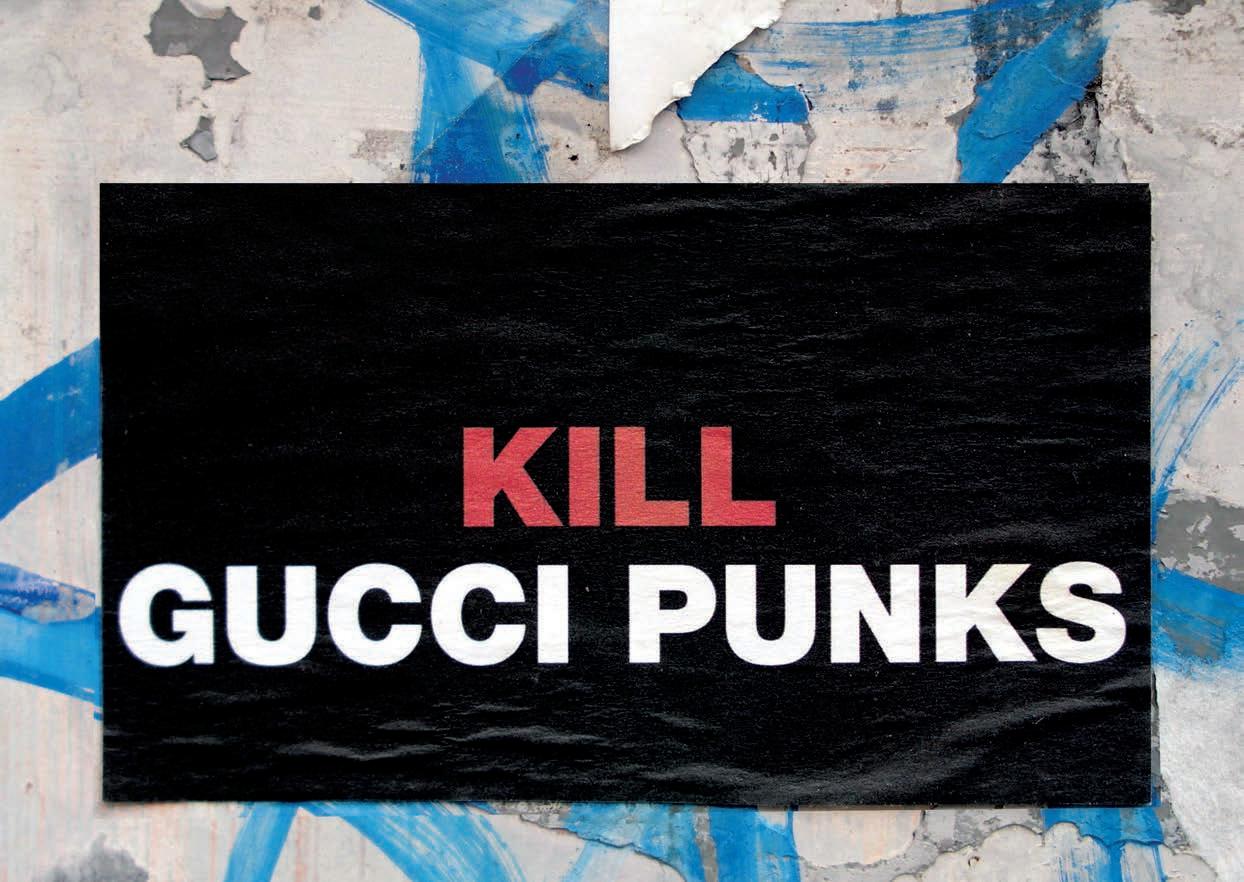

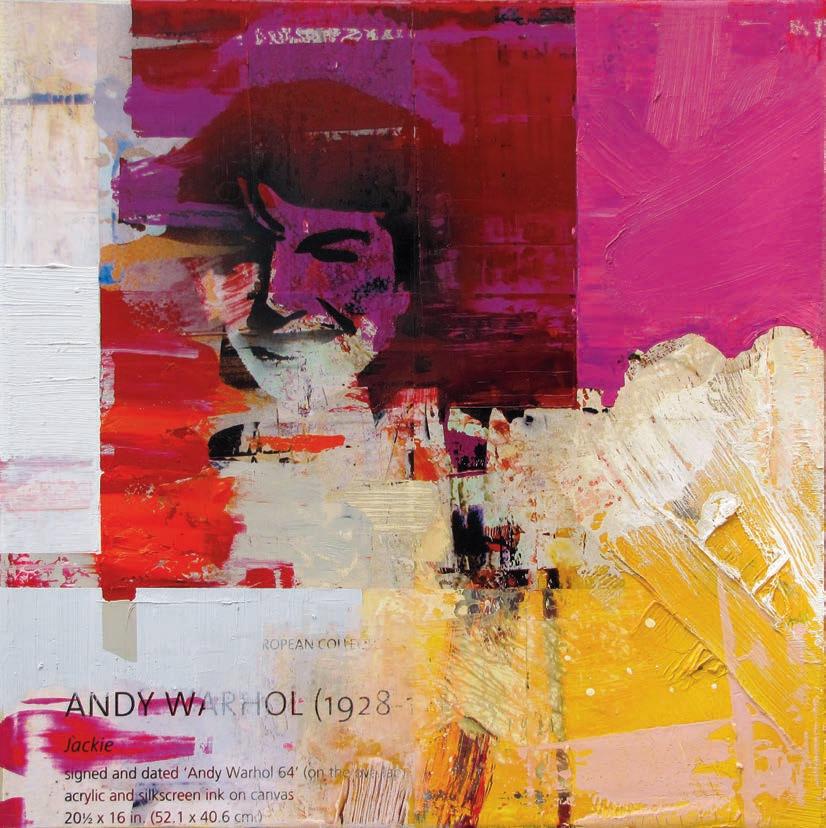

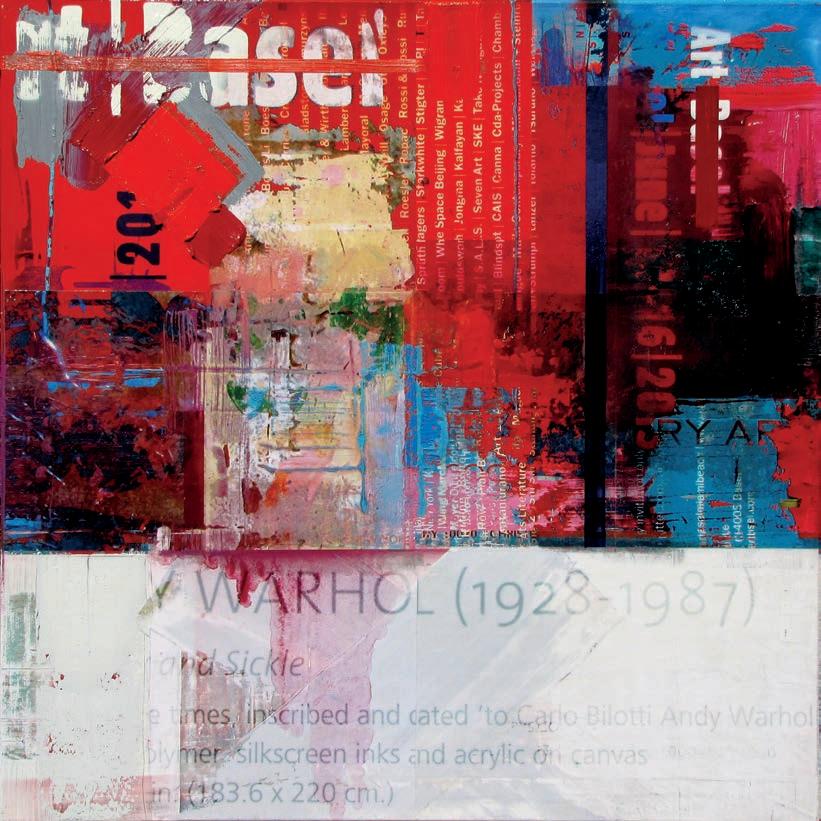

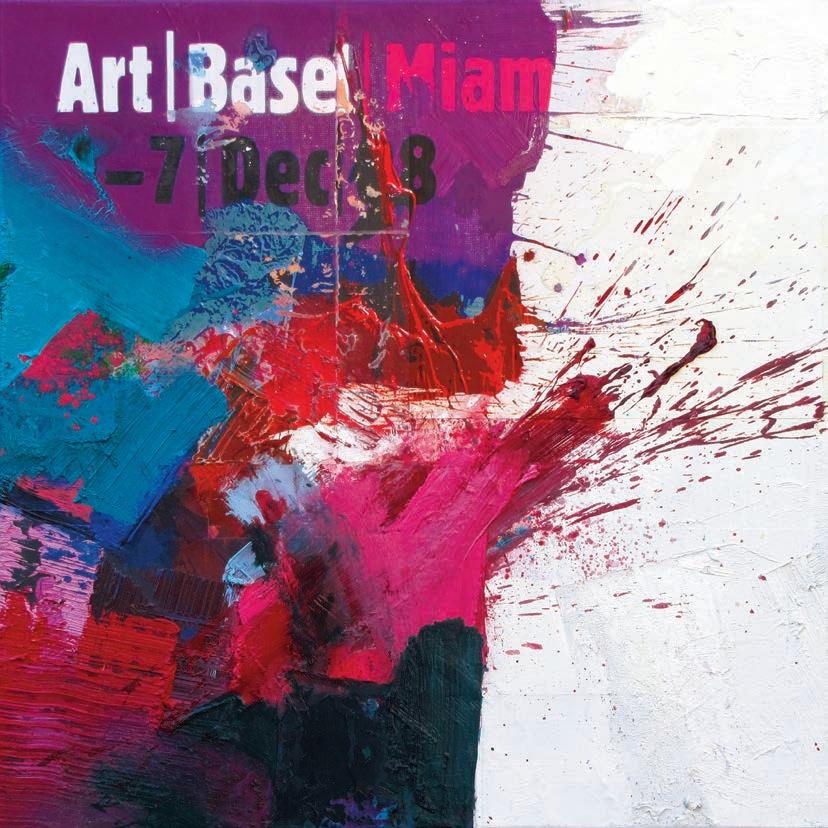

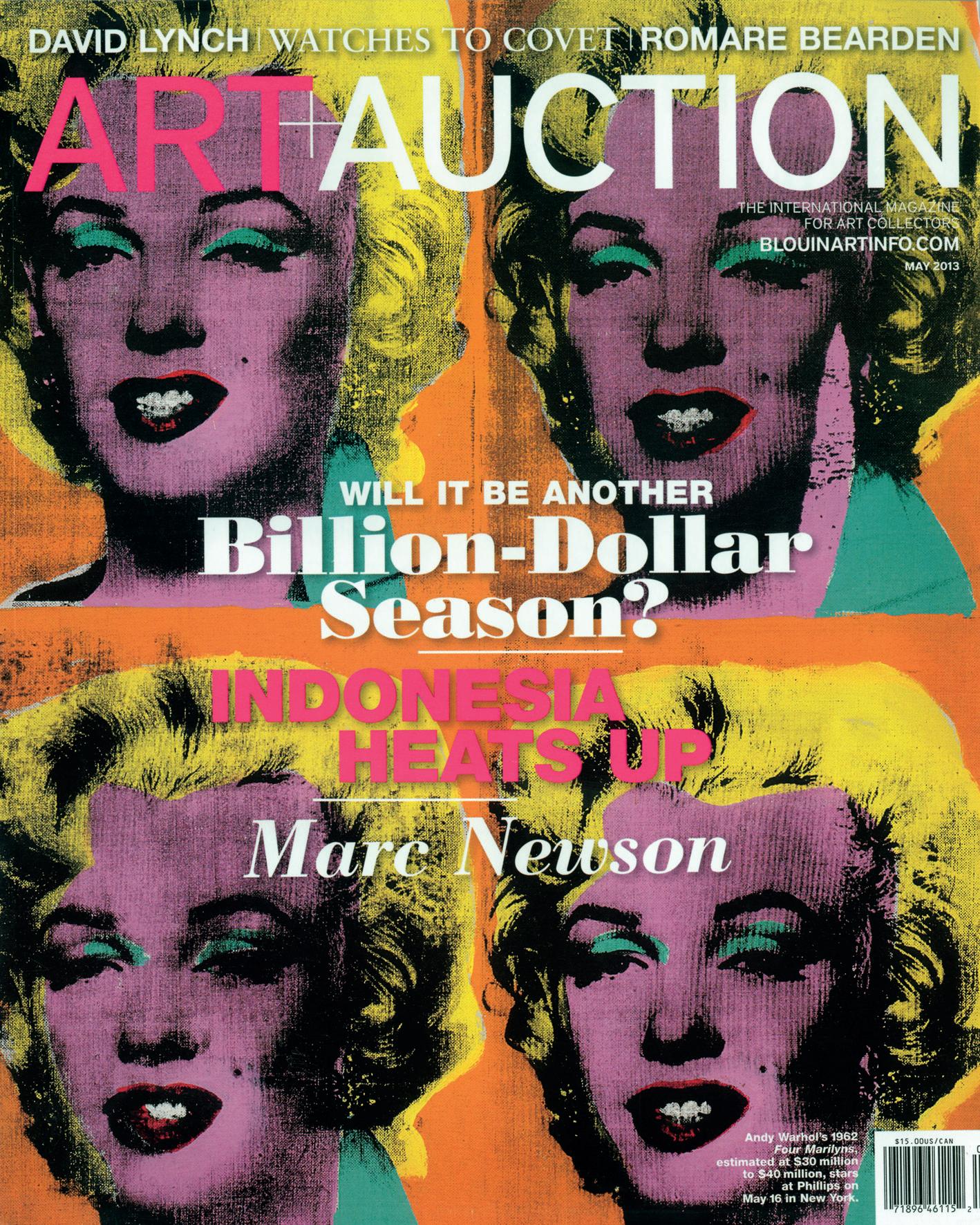

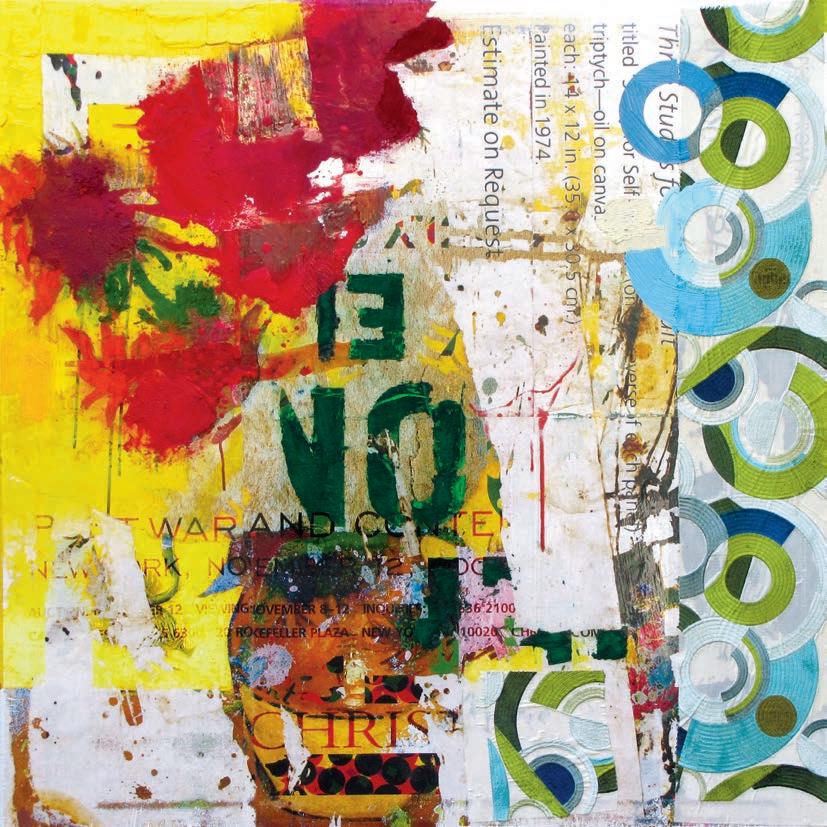

Like a kid in a candy store, it seems to Peter Vahlefeld that the entire history of art and image making is present at the same time—it´s all now. His paintings distort art historical references deconstructing the role of abstraction in both modernism and contemporary art practice. Recognizable visual codes and references like logos, gallery names, exhibition titles, quotes from art history, prices from auction house catalogues, and names of artists such as Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, Georg Baselitz, and David Hockney pop up. Peter Vahlefeld´s abstractions unite high art and popular culture as unorthodox tableaux of unequivocal beauty. Built up in sensuous layers of inkjet prints and paint, ranging from silky and skinlike to oily and singed, he offers abstraction in his grid-like compositions with an urban flair that´s explosively contemporary. Evolving his surface as a highly textured topography, Vahlefeld uses gesture and mark making to encapsulate the dissonance and excitement of a metropolitan media landscape. Each work confounds expectations and provokes another painting and a new set of challenges. Painting thus, for the artist, is a practice of overlaying multiple images in which one mark leads to the next–and one completed work leads to another. One over-painted advertisement superimposed over another one to be overpainted again. The layers of paint are worked and reworked over long periods of time; each layer contains a shade of the past layer, and so forth. Peter Vahlefeld establishes a totally new and complex relationship between the painted and the digitalized image of paint. The power of the image has turned against itself, partly or entirely defaced. The highly stylized »Untitled Painting on Andy Warhol´s Orange Marilyn by Christie´s« epitomizes the polished allure of luxury consumer culture. The »Warhol-Paintings« of over-painted auction house catalogue pages are not simply riffing on the recent »hotness« in the Warhol market and then slightly supplemented by trying to cash in on reputation, brand, and logo but they become a canvas for making a comment about the art-market-as-commodity-bubble which has burst all over everyone´s faces, like a big rainbow-coloured spunk-bomb made of liquid cash. Higher. Faster. Farther.

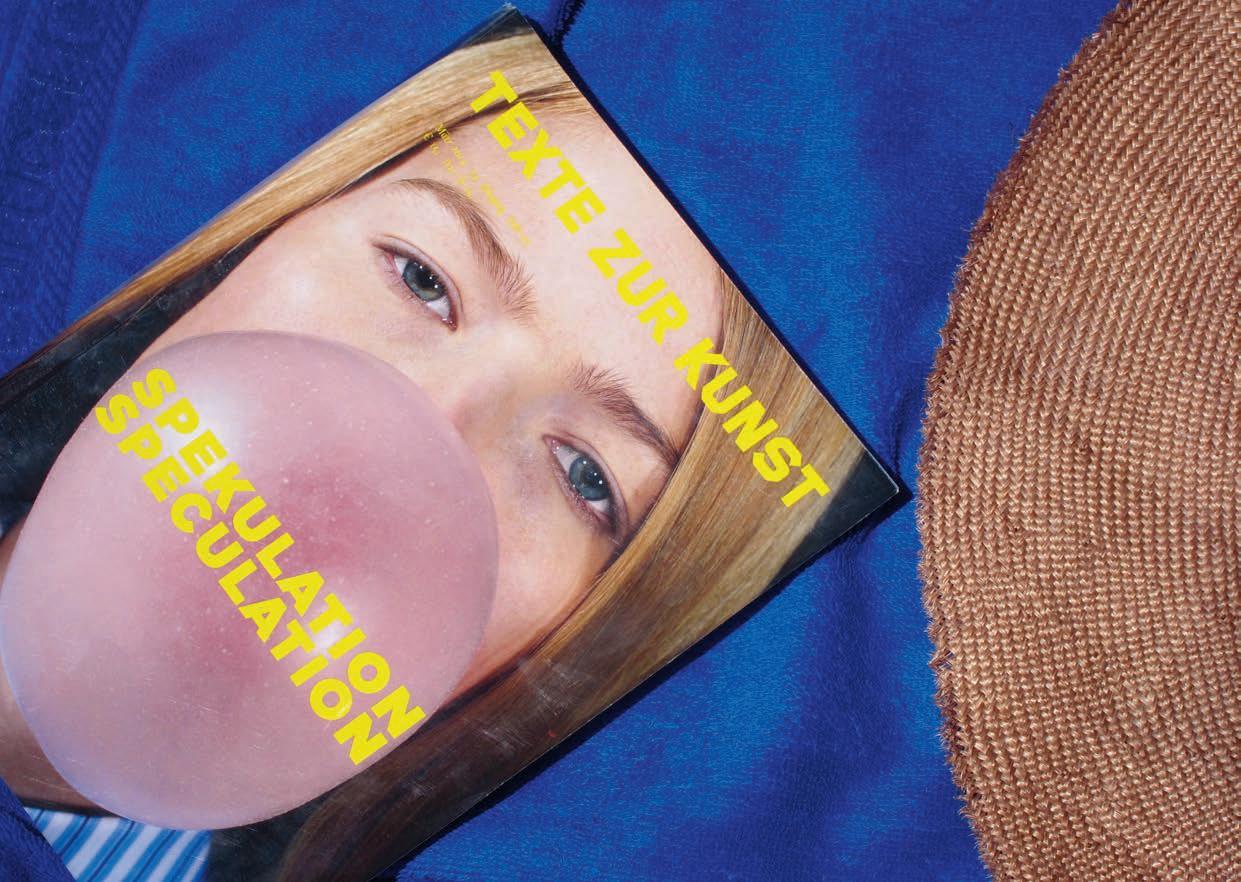

The ability to reproduce images, higher, faster, farther is at the base of our entire culture now and »Institutional Critique« in which artists criticize the institutions they‘re forced to inhabit does plug in rather perfectly to the insane contemporary art market, where culture exists in a state of simultaneity, and where all of art history and institutional critique is equally available for use. Much of the work categorized as »Institutional Critique« since the late 1960s parodies the power of art without either adequately defining it or coming close to actually extinguishing it. Asserting that a work of art is a function of the framing

conditions of the museum or other art world institutions is certainly not false, but it tends to accept the museum´s ideological self-presentation on its own terms as a given rather than exploiting its complex format more creatively or to bypass the art world altogether. Every day we are seeing nonstop; every day there are a myriad of images being dumped into our awareness. The various categories, media and histories become materials to use like the institutions you inhabit. In a literal depiction of a graveyard, Peter Vahlefeld presents the canon of art history as a hallowed myth, resonant beyond its expiration date of the latest contemporary evening auction or museum shop calendar. Their self-consciously brutal surfaces seem to be corrupted from within. A decoded script of interrupted image and muted texture takes its pleasure in contrast and surface humorously critiquing the hallowed respect and predominant values of art history, which have to be monetized by auction houses in order to gain value.

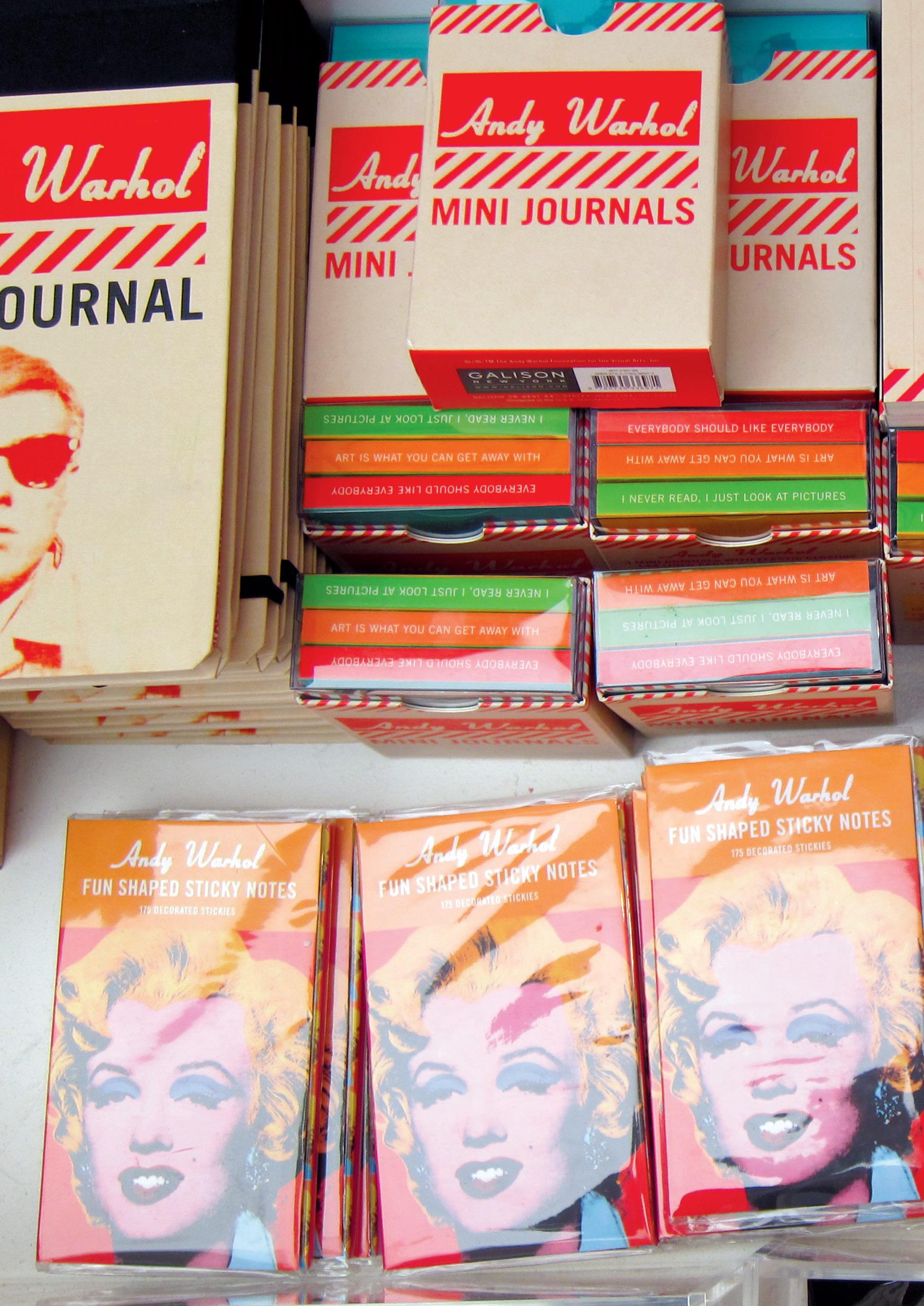

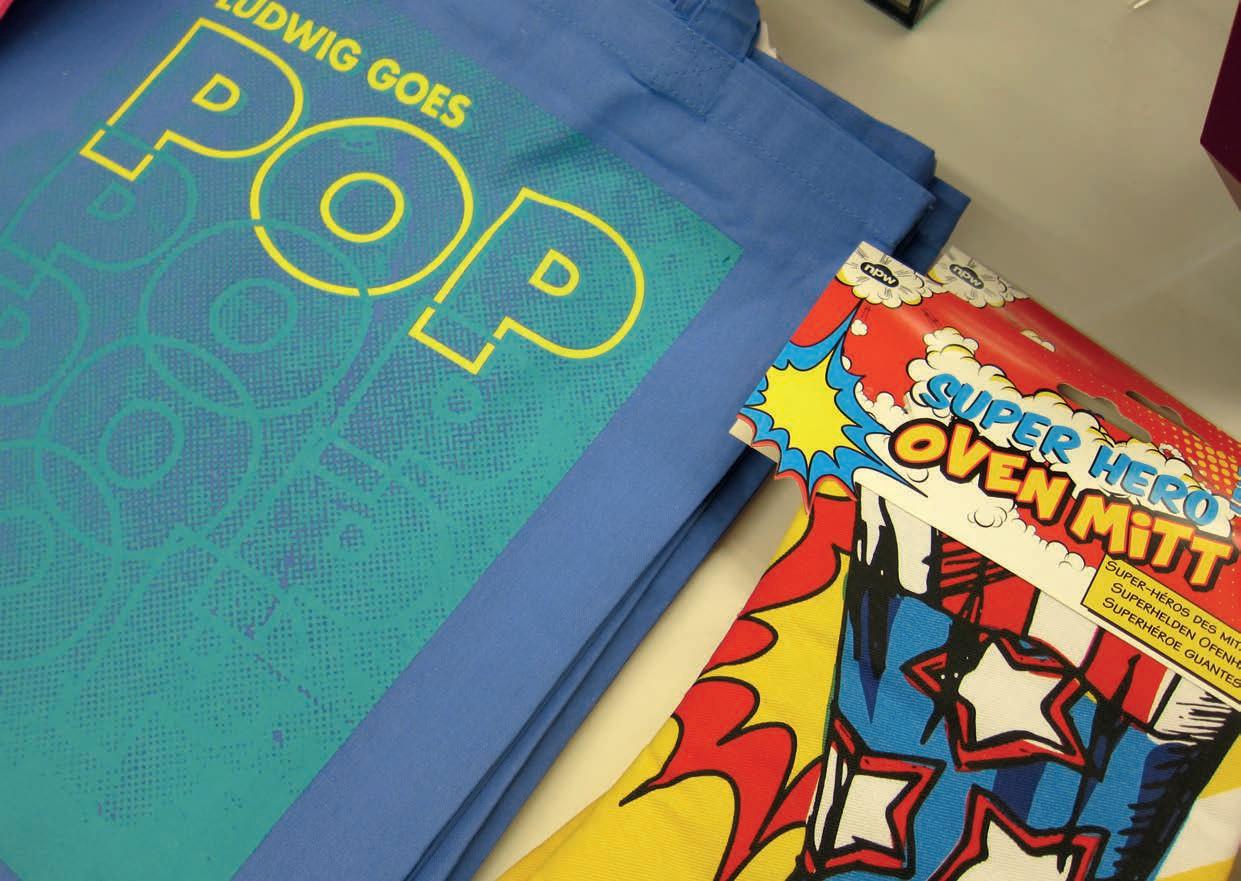

What has happened that has made images the focus of so much passion? Museums are jam-packed with massive queues and people running frenetically not to miss their allocated time slot. Big institutions must be given credit for making contemporary art available to the masses, and that´s obviously very important, but regrettably, at the same time, the individual experience has been heavily compromised—except for the museum shop, which amalgamates past, present and future with merchandising providing a platform for fridge magnets, coffee mugs, puzzles, cushions, etc.

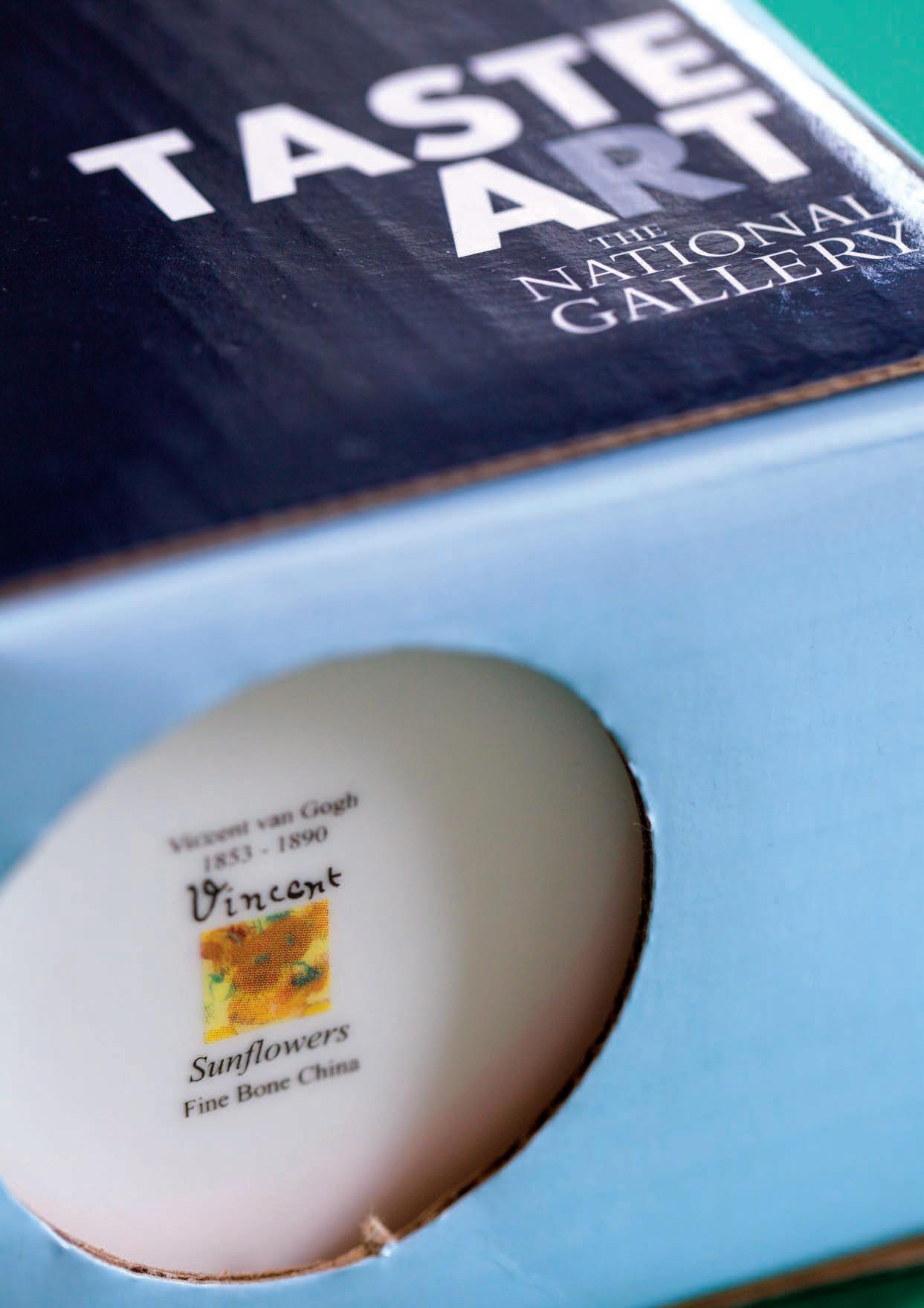

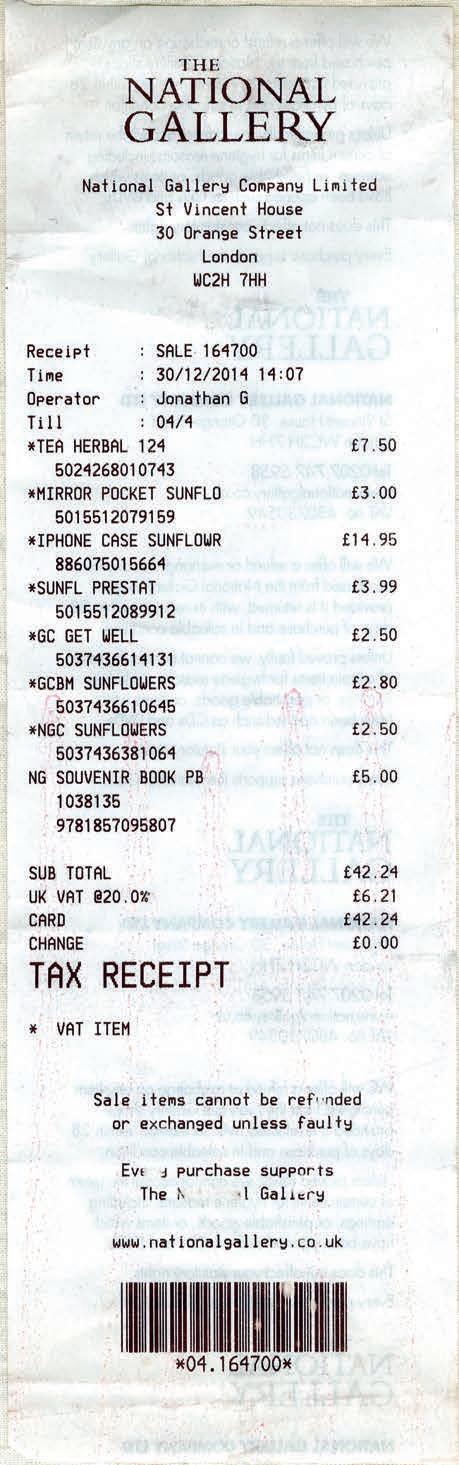

Vahlefeld´s over-paintings of museum shop merchandise draw on the symbiotic relationship between high art and commerce, exploring the »un-reality« where art becomes fashionable and this fashion excessively cheap. Fridge magnets with Vincent van Gogh´s Sunflowers for 5 GBP; T-Shirts, tattoo templates and even toilet paper with the same motif for 3 GBP. The quaint old notion of the museum as a haven for the contemplation of the art it owns has given way to the museum as a cog in the exhibition-industrial complex of shopping malls, to put on an endless list of exhibitions, to satisfy show-addicted visitors, tourists, critics, sponsors, trustees, politicians. And if the show is sold out, please apply for tickets online a minimum of several weeks in advance !!!

By embracing digital innovations and state-of-the-art marketing strategies, museums have finally embedded themselves in the mass culture machine as well. Museum shop merchandise and their surface of art are used as a means of seduction or ridicule; they appear highly plasticised, saturated in gloss and permeated by sensuality. To confront the binary of oppositions, which pervades contemporary art, Peter Vahlefeld deconstructs, reconstructs and abstracts these surfaces; knowing how to work with materials loaded with symbolism in order to suggest something else. The notion that art has some inherent value is the central and most productive illusion of the art market. The rhythms of production, distribution, and consumption are now key, not the things in themselves, that characterizes our cultural moment at the beginning of this new millenium.

Richard Mutt

3

Untitled Painting on Andy Warhol´s Self-Portrait by Christie´s 2015 Oil, Inkjetprints, Fabric on Canvas 200 x 140 cm

6

7

200 x 135 cm

8

Untitled Painting on Basquiat´s Job Analisis by Christie´s 2015 Oil, Inkjetprints, Fabric, Epson Ultrachrome Ink on Canvas

200 x 135 cm

Am 3. Februar 2015 rief das Auktionshaus Sotheby´s in London das Los mit der Nummer 21 auf: ein Bild von Claude Monet, »Die Pappeln in Giverny«, geschätzt auf 14 bis 18 Millionen Dollar. Eingeliefert hatte es, was die Sache interessant macht, das Museum of Modern Art in New York, weil das Bild, so hieß es, nicht mehr in das Sammlungsprofil des Hauses passe. Kunstwerke, jedenfalls die des MoMAs, haben die Eigenschaft, dass sie teuer sind. Dass die Kunst kein Spekulationsobjekt sei, belehrte Kulturstaatssekretärin Monika Grütters die Spiel- und Landesbanken Nordrhein-Westfalens, die Ende 2014 ihre Andy Warhols versilberten und es mit weiteren 380 »Objekten«, darunter Werke von Picasso und Sigmar Polke, noch vorhaben. Allerdings kann man die Kunstsammlung von Casinobetreibern oder ehemaligen Landesbanken nicht mit der eines Museums vergleichen. Banken und vor allem Casinos sind ja selbst Spekulationsspezialisten. Sie nehmen ihren Kunden Geld ab, und damit die das nicht merken, schmücken sie die Wände mit Kunst. Einmal mit dem Verkaufen angefangen, werden die Museen jetzt wahrscheinlich massenhaft ihre Werke verschleudern, um Heizungen zu erneuern, Klos zu bauen und Museumsshops einzurichten.

Monet – Manet – Money – nirgendwo offenbart sich unserer Zeit deutlicher als in diesem symbolischen Austausch des Konsums. Er ist der Zirkus, in dem unser Lebensstil verhandelt wird, und wie gut es uns als Konsumenten geht: »mein Haus, mein Auto, mein Boot, mein Bild, meine Frau«. Werbung und Kunst rivalisieren miteinander als ernstzunehmende Konkurrenten im freien Spiel um Illusion und Ästhetik in dem beide die für die andere Partei typischen Strategien für sich in Anspruch nehmen. Peter Vahlefeld lässt dieses Paradox, in seiner Malerei, nicht ohne eine gewisse Ironie, aufeinanderprallen, als Kommentar zur malerischen Geste des abstrakten Expressionismus und zugleich als Reflexion über die Kunst an sich.

Zunächst sind alle verwendeten Vorlagen, die er übermalt, Medienprodukte, die zirkulieren, um auf Kunstereignisse, Ausstellungen und Auktionen, aufmerksam zu machen. Bei den Übermalungen von Auktionshauskatalogen und deren Anzeigen, ist der Zusammenhang zwischen der Zirkulation des Bildes und der erwarteten Zirkulation einer möglichst hohen Geldsumme offenkundig. Konsequenterweise lässt Vahlefeld nahezu alle schriftlichen Hinweise auf die Funktion und den Kontext der Abbildungen wie Bildunterschriften, Seitenzahlen und Galerienamen sichtbar. Die Druckerzeugnisse werden mit Ölfarbe attackiert und erscheinen im Orginalformat wie archaische Manifeste. Das Widerspiel aus skulptural modellierter Farbe – pastosem Vordergrund und planem Hintergrund – wird ausgeleuchtet, digital fotografiert und dient fortan als Malgrund, wobei Vahlefeld die computergestützte Bildproduktion als Fortsetzung der Malerei mit anderen

Mitteln versteht. Seine Medien sind Inkjet-Drucke mit pigmentierten Tinten im Dialog mit Acryl- und Ölfarbe. Das Material wird, anders als im Rechner dessen Funktionslogik auf beschriebenen Regeln basiert, selbst zum Thema als Folge von Aktionen. Geschüttete Farbpartien und markante Gesten, treffen mal auf ein digitalen Ausdruck, mal auf farblichen Stoff oder echte Farbe. Mit Pinsel, Rakel, Roller, Schablonen, Schleifgeräten und anderen mechanischen Hilfsmitteln wird gestört oder neu aufgebaut, bis die so gesetzten Akzente das Bildgefüge überraschen oder irritieren.

Peter Vahlefelds Bilder sind kraftvoll und expressiv. Jeder Malakt ist eine Setzung, die eine andere nach sich zieht. Das Digitale reflektiert dabei die Malerei als Möglichkeit, verhandelt sie, während sie im Analogen wirklich praktiziert wird, um danach in Teilen mit dem exakt fotografischen Abbild verkleidet zu werden. Die Leinwand als tautologische Tapete, die Peter Vahlefeld dann wieder digitalisiert, um sie erneut mit digitalen Ausdrucken zu verkleiden und zu übermalen. Verdoppelungen, Trompe-l´oeils, Vergrößerungen und Raster sind die spielerischen Mittel, mit denen er die Ikonen der Kunstgeschichte hinterfragt. Durch wiederholtes Scannen, Ausdrucken und Übermalen wird das Branding der Medienprodukte mit Farbe kontaminiert und deren Bedeutung ausgelöscht. Übrig bleibt oft nur eine zerschürfte Bildoberfläche, die durch ihre Schichtungen plastische Tiefe vermittelt. Was gemalt erscheint, kann ausgedruckt, was wie gedruckt erscheint, tatsächlich gemalt sein. Die suggerierte Unmittelbarkeit der Farbe, Farbspritzer und Schlieren zeigt sich dabei oft als technisch vermittelte Repräsentation. Nicht nur die abstruse Größe der Farbspritzer verrät deren Artifizialität – man erkennt Wiederholungen derselben Schlieren, die sich in unterschiedlichen Anordnungen auf der Bildfläche verteilen und zu abstrakten Flächen verdichten. Es ist die Differenz des Bildes von sich selbst, die sich unmissverständlich als Tautologie manifestiert und sich zwischen das Material und dessen Erscheinung legt. Die Wirkung der Bilder hängt von dieser medialen Verdopplung ab und ist nicht als Zitat der eigenen Übermalung zu verstehen, sondern als Wiederholung ihrer eigenen Mediatisierung. Was sich wiederholt, ist nicht nur die ursprüngliche Malerei mit Farbe und Pinsel, sondern die Reproduktion dieses Vorgangs als massenmediales Bild, wo zwischen materieller Spur und ihres kommerziellen »Aus-Drucks« durch einen Tintenstrahldrucker nicht mehr klar unterschieden werden kann. Malerei, die ihre eigene Geschichte als massenmediales Abziehbild reflektiert, wird zugunsten eines expressiven Gestus und einer abstrakten Komposition teilweise komplett ausgelöscht. Außer dem Namen des Künstlers, dem des Galeristen oder Auktionshauses ist alles übermalt. Vielleicht ein ironischer Kommentar oder nur ein bissiger Hinweis auf die Art und Weise, in der wir heute nicht den Werken der bildenden Kunst einen Wert zumessen, sondern den damit verbundenen Markennamen und Millionensummen! Enteignung (Expropriation) ist deshalb hier vielleicht der bessere Begriff als Aneignung. Enteignet ist nicht nur der Inhalt des Bildes – enteignet ist vor allem die Form des Bildes selbst.

Luther Blisset

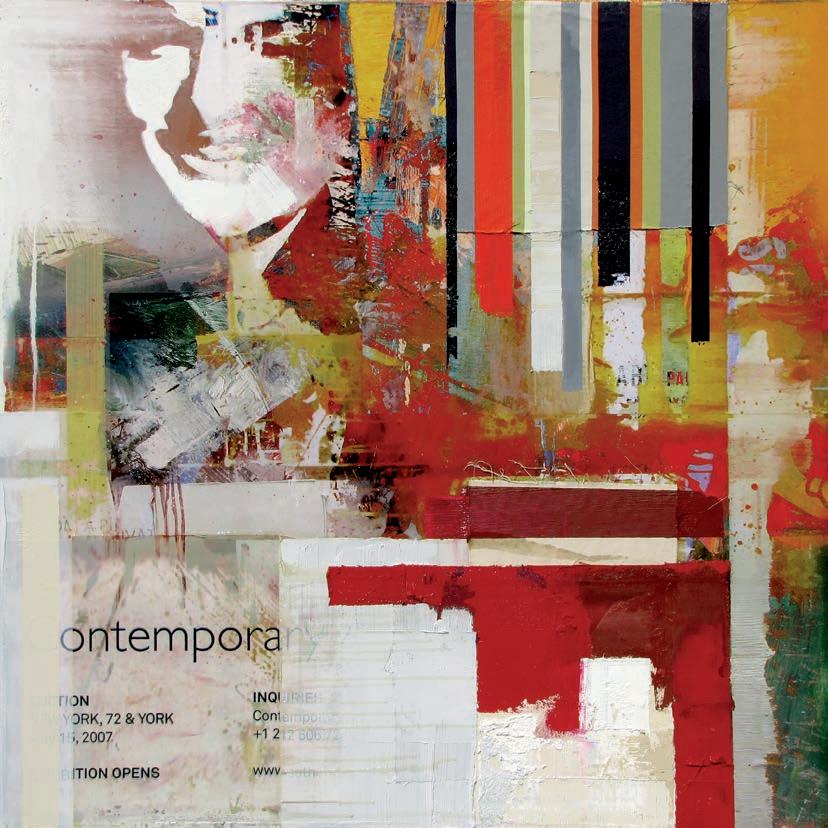

15 Advertisement »The Hermitage/Prado« | 2015 | Oil, Inkjetprints on Canvas | 120 x 120 cm

21

Untitled Painting on Andy Warhol´s Self-Portrait by Christie´s 2014 Oil, Inkjetprints, Fabric on Canvas 160 x 160 cm

27

200 x 150 cm

Peter Vahlefeld: Shopping at the National Gallery, London

Peter Vahlefelds intuitives Interesse an Malerei mischt sich mit dem Interesse an ihrer immer stärkeren Mediatisierung. Was ist ihr eigentlicher Wert und nicht nur ihr monetärer Preis und ihre bildnerische und verbale Präsenz in den Medien? Kunst und Kommerz waren immer untrennbar verbunden, Kirche und Establishment ermöglichten nach ihrem Gutdünken die zuweilen feudale künstlerische Existenz. Heute bestimmt ein Netzwerk öffentlicher Sammlungen, etablierter Privatsammler, Kritiker und Galeristen über erfolgreiche Künstlerkarrieren. So wird wie in vielen kreativen Berufen die ständig nachwachsende Avantgarde beobachtet, gefiltert und partiell aufgesaugt, bis sie irgendwann mit dem neuen Etikett Mainstream und um ihre Unabhängigkeit gebracht, Eingang in die etablierte Kunstwelt findet.

Aktuell sind zwei der fünf ikonischen „Sonnenblumen“ van Goghs in der National Gallery in London nach 65 Jahren wieder dort gemeinsam zu sehen. So wie ihnen geht es vielen Werken großer Museen. Sonnenblumentassen, T-Shirts, Schals, Kühlschrankmagnete, Mauspads und unzählige andere Merchandising-Produkte werden mit dem medial tausendfach multiplizierten und komplett ausgelutschten Motiven verkauft. Mit einer leichten Gänsehaut und der schaurig-schönen Freude am Bizarren stellt man sich den Akt der Selbstverstümmelung eines der mittlerweile teuersten Künstler der Moderne vor. Das menschliche Drama hinter den Arbeiten ist widersprüchlich recherchiert und interpretiert und wurde schon früh aus strategischen Gründen frisiert. Kurz vor der ersten Delle des Kunstmarktes Ende der 80er Jahre des letzten Jahrhunderts zahlte der japanische Yasuda Konzern schon 1987 unfassbare 72 Millionen Mark für die „Sonnenblumen“ des niederländischen Nationalheiligtums und legte noch einen Anbau des Amsterdamer Museum drauf.

Der unvoreingenommenen Beziehung Bild-Betrachter beraubt, verschlissen und ausverkauft, ist das nur ein Beispiel, wie Kunst als teure Marke mit hohem Wiedererkennungswert dem wirtschaftlichen Überleben oder Wachsen Ihrer Häuser dienen muss. Symbolverlust und totale Entzauberung sind die Folge. Teuer im Sinne immer neuer Kunstmarktrekorde bezeichnet dabei nicht mehr den echten Wert eines Kunstwerkes. Eben jenen Wert, der in der Faszination des Betrachters liegt. In seiner individuellen Begegnung mit dem Bild. Vor dem er, ergriffen oder verzaubert, schockiert oder begeistert innehält und verweilt. Vor welchen Bildern geht es uns als Betrachter noch so? Sind es nicht nur noch die Bilder der Avantgarde, die wir noch nicht kennen und die uns an nicht-etablierten Orten begegnen? Sind nicht die Arbeiten international bekannter Künstler zur Marke

verkommen, die wir in einer Millisekunde wahrnehmen, uns dann aber der Provenienz, dem Preis(rekord), dem Titel, dem Entstehungsjahr, dem Leihgeber o.ä. zuwenden?

Um diese Frage geht es Peter Vahlefeld in seinen Arbeiten. In Gesprächen äußert er sich immer wieder kritisch über diesen Ausverkauf der Kunst, bei dem man gerade in Ländern mit magerer öffentlicher Kulturförderung rätselt, ob die Werke mehr dem Kommerz unterworfen sind oder der Kommerz den Werken einer Sammlung dient. Es erfordert Selbstdiziplin und Hingabe, um sich in der National Gallery zwischen den geführten Menschenmengen und Kopfhörerträgern der „Blockbuster“ noch einen Moment der Kontemplation zu erkämpfen. Einen Moment, in dem man auch einen van Gogh in Ruhe und ohne die mediale Vorprägung im Kopf auf sich wirken lassen und abwarten kann, was das Bild mit einem macht. Bestimmt die Nachfrage das Angebot an Merchandising in der Kunst? Oder das Angebot die Nachfrage? Erschließt sich dem auf den Museumsshop konditionierten Besucher das eben Gesehene eher im Taschenformat und als Notizblock oder Küchenschürze? Macht es das Werk in seiner Verfügbarkeit zuhause sympathischer? Oder geht es um den positiven Kurzkick des Shoppens, der zum vermeintlichen Wohle aller Beteiligten Einzug ins Museum gehalten hat? Sind wir als hochbeschleunigte Medienbildkonsumenten selbst schuld an der endlosen Vervielfältigung der Bilder, wie sie schon Walter Benjamin besprach? In der kollektiven Wahrnehmung verlor für ihn das Kunstwerk seine Aura. Die so entstehende kollektive Ästhetik bot für ihn zwar die Möglichkeit der Entwicklung hin zu gesellschaftlichen Emanzipation, weg von der reinen Wahrnehmung durch Eliten. Andererseits barg sie für ihn aber auch die Gefahr der Vereinnahmung und Entzauberung, die Kunst am Ende immer ein Stück weit bewahren sollte.

Dr. Stefanie Staby

Peter Vahlefeld

born in Tokyo, Japan

1988 Grant, Parsons School of Design, Paris

1990 Honor-Degree, Parsons School of Design, New York

1991 American Illustration 10th Annual Award, New York

2003 Photoshopaward, Berlin

lives, loves & works in Munich & Berlin

Solo Exhibitions & Events

2015

Benefit Auction, Sotheby´s, Vienna

Saatchi Art, curated by Rebecca Wilson for Collectors in Edmonton (Canada), Kiev (Ukraine)

One Artist Show, art Karsruhe, Galerie Michael Heufelder

Shopping at the National Gallery, ROCO Interior Design Magazine, London

Saatchi Art Collection, curated by Rebecca Wilson, Venice, California, USA

Monet – Manet – Money, White & Case, Munich

One Artist Show, Art Bodensee, Galerie Michael Heufelder

2014

Christie´s + Andy Warhol = Everybody Disco, Earlybird Venture Capital, Munich

Feels Like Miami, Saatchi Art Collection, curated by Bridget Carron, Los Angeles, California, USA

Art Basel Miami Beach at British Vogue, London

Saatchi Art Collection, curated by Rebecca Wilson, Venice, California, USA

Artist Talk: Stephanie Senge, Peter Vahlefeld & Prof. Wolfgang Ullrich, nurjungekunst, Munich

Art Bodensee, Galerie Michael Heufelder

Spotlight on Berlin, Saatchi Art Collection, curated by Katherine Henning, Los Angeles, California, USA

Saatchi Art, curated by Rebecca Wilson for Collectors in Oslo (Norway), Houston Texas (USA), Mumbai (India)

Ist das Silikon in Pamela Andersons Brüsten echt?, Elizabeth Cooper Gallery, Leipzig

The Warhol Economy, White & Case, Munich

2013 Featured in: Highlights of the Year; Inside the Studio; Our Curator´s Picks; Saatchi Gallery, London/ Los Angeles/Online, Inc.

Salon Populaire, Galerie Michael Heufelder, Hamburg

Ist das Silikon in Pamela Andersons Brüsten echt?, Galerie Michael Heufelder, Munich (Catalogue)

Salon Populaire, Arena, Berlin (Groupshow)

Contemporary Art Collection, White & Case, Munich

2012 Auction of Contemporary Art, Neumeister Moderne, Munich

New Worxx, Irmin Beck, Munich (curated by Dr. Stefanie Staby)

Painting vs. Photography, White & Case, Munich

2011 Contemporary Art Collection Grunwald, Munich

Robert Mapplethorpe Overpaintings, ZDF Berlin

Kunstindex Berlin, Arena, Berlin (Groupshow)

Photography vs. Painting, White & Case, Munich

Pictures of Pictures, 46 Parachute Purple, New York (Groupshow)

2010 J´adore Cannes oder where´s my fuckin´Gucci shoe tree, Kultursalon, Vienna

J´adore Cannes oder where´s my fuckin´Gucci shoe tree, Chloe Savigny, Paris

Honorarkonsulat Ecuador, Munich (Galerie Michael Heufelder/Dr. Stefanie Staby)

J´adore Cannes oder where´s my fuckin´Gucci shoe tree, Fiona Alison, London

2009 El Quitasol, Galerie Michael Heufelder, Munich (Catalogue)

El Quitasol, McDermott Will & Emery, Munich

2009 I shot Andy Warhol, Schlosspavillon Ismaning, Munich

2008 I shot Andy Warhol, Galerie Brennecke, Berlin

I shot Andy Warhol, Galerie Winkelmann, Düsseldorf

2007

Nur wer den Klatsch der Stadt kennt, findet den Mörder, Galerie Michael Heufelder, Munich (Catalogue)

Nur wer den Klatsch der Stadt kennt, findet den Mörder, McDermott Will & Emery, Munich

Nur wer den Klatsch der Stadt kennt, findet den Mörder, Galerie Winkelmann, Düsseldorf (Catalogue)

Nur wer den Klatsch der Stadt kennt, findet den Mörder, Galerie Brennecke, Berlin (Catalogue)

Nur wer den Klatsch der Stadt kennt, findet den Mörder, Earlybird Venture Capital, Munich

Pop-up Gallery de Miguel, Luisenstrasse 55, Munich, (curated by Credit Suisse/Dr. Stefanie Staby)

2006 Was stimmt nicht, wenn alles in Ordnung ist, Galerie Brennecke, Berlin

2005

At home he feels like a tourist, Pop-up Gallery de Miguel, Luisenstrasse 55, Munich (curated by Dr. Stefanie Staby)

2004 Luxus, Stille, Lust, Stadtmuseum/Kunstverein Bautzen (Groupshow) Catalogue

At home he feels like a tourist, Galerie Brennecke, Berlin (Catalogue)

At home he feels like a tourist, Galerie Winkelmann, Düsseldorf (Catalogue)

Insideout, Patrick Heide Art Projects, London

2003 Digitale Bilderwelten, Willy-Brandt-Haus, Berlin (Groupshow)

Der Geschmack der Stadt, Volksbühne, Hamburg

2002 Natura Morta, Galerie Brennecke, Berlin

Lauter Still-Leben, Galerie am Michel, Hamburg

Still Life, Galerie Sarré, Munich

2001 Natura Morta, Art Transfer, Munich (Catalogue)

1997 Souvenirs, Galerie in der 7. Etage, Eternit, Berlin

1995 Still Life, Philip Morris, Berlin

1992 Still Life, Visual Miracles, New York

1991 Society of American Illustrators, New York (Groupshow)

1991 Barneys, New York (Groupshow)

1991 Still Life, Visual Miracles, New York

1990 Possible Photography, Ward Nasse Gallery, New York

Art fairs

2014 Art.Fair Cologne (Galerie Michael Heufelder) 2014 bis 2012 art-Karlsruhe (Galerie Michael Heufelder); 2010 bis 2004 art-Karlsruhe (Galerie Brennecke); 2007 Liste Köln Art Fair (Galerie Brennecke); 2002 Kunst Köln, Galerie Brennecke

Private & Public Collections

Eternit, Berlin; Philip Morris, Berlin; Schering, Berlin; Dobergo, Lossburg-Betzweiler; McKinsey & Company, Düsseldorf; Victoria Versicherung, Düsseldorf; Geneva Business School, Geneva; Fiona Alison, London; Dallmayr, Munich; Grunwald, Munich; Heisse Kursawe Eversheds, Munich; Riedenauer Education, Munich; White & Case, Munich; Chloe Savigny, Paris; Sammlung Alexander Stauder, Vienna; Bennett Property Holdings Co. Ltd, Mumbai, India