Dear readers,

Welcome back once again for another amazing issue!

The theme of this issue is one very close to our hearts, as we have both experienced living in different countries throughout our lives, and have lived with the feeling of adjusting to a new place, culture, language, customs and social groups.

Even so, everyone’s circumstances, and unique relationship to the place where they live, or where they have come from, can make these experiences feel radically different.

Depending on what country you move from and to, of course, you will have a different experience…Whether you already know the language of that country is also a huge point of difference…Whether you move alone, or with a spouse or with your whole family…Whether you’ve ever moved to another country before… Whether you’re an adult or a child (and exactly what age you are) when you move...Whether there are any prejudices against your people in the country that you’re moving to…And whether you have moved for economic opportunities, familial reasons, to experience a different culture, or to flee from an ongoing war, will all of course, have completely different bearings on your experience.

There are so many factors that influence our personal relationships with place and identity.

It’s barely ever enough for most people to say, “I am (insert singular national identity)” or “I’m from (insert place of origin)” and neatly sum up their story of origin, without batting an eyelid.

More often and not, these answers are fraught with contradiction, complexity, personal and political history, and many times, a hugely revealing part of ourselves - which we sometimes just don’t want to get into with a complete stranger.

What we aimed at with this issue is to fully explore these parts of identity, to get a sense of the diversity, and perhaps commonality, of these experiences, and as always, try and bring them together by combining the work of artist and writers, into one cohesive whole.

We were absolutely fascinated by some of the stories shared in this issue when we received them. Stories of emigration, war, transracial adoption, and even a community of people trying to revive a remote settlement formed by their ancestors in the Mediaeval period, to name but a few.

The host of international art which appears alongside these works, as always, tells its own story, and we feel, helps these themes resonate on an even deeper level. We also have a strong offering of editorial photography for the second time running, which we are incredibly excited about.

We’re so proud of all the work included in this issue, all of the amazing emerging artists and writers who have contributed, and of having been able to bring to life a topic of this importance and magnitude on our platform.

We hope it can open your mind to experiences you may never have encountered or thought about before, and that these may resonate with you, as you go about your own journey through this world.

So, without further ado, we welcome you to come along, and share in the many worlds inside these pages.

Safe travels, Dom & Siria VAINE Editors

LIANNE WILSON p. 12-13 ‘Dasperghenegi’

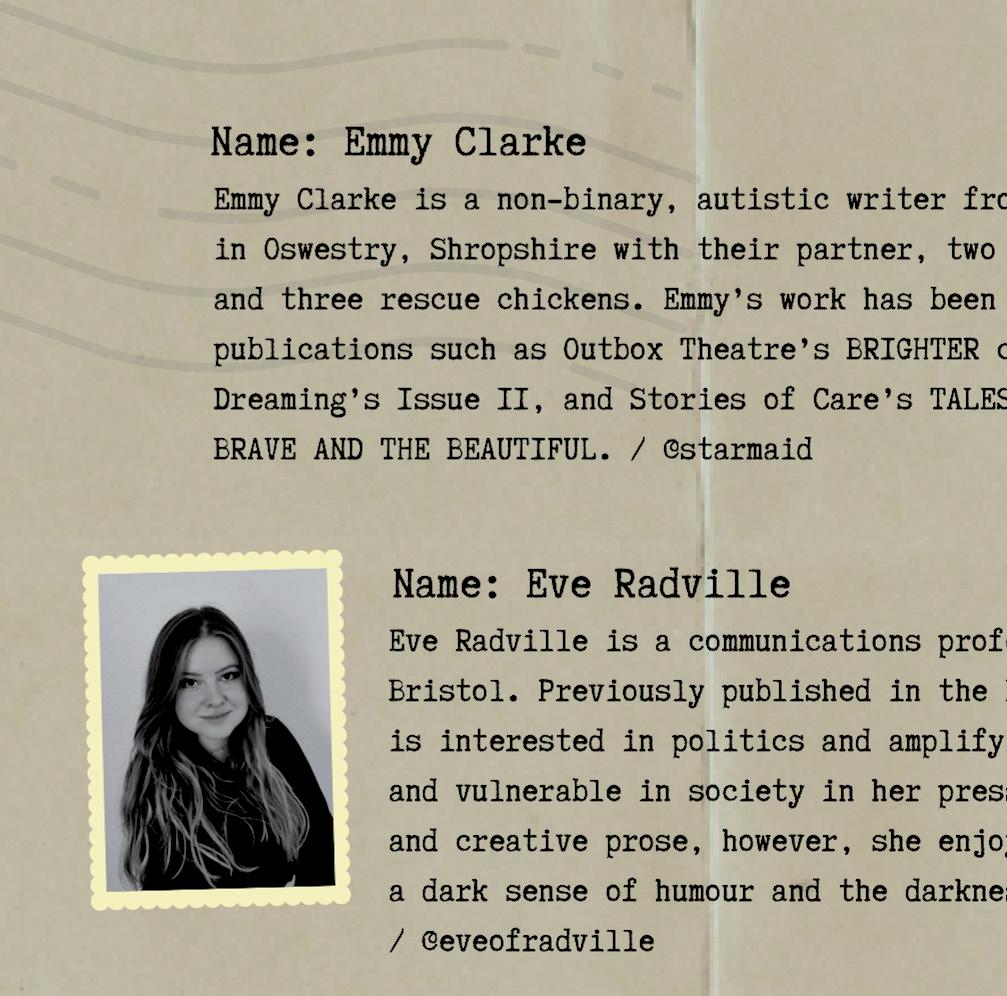

EMMY CLARKE p. 24 ‘SAME’ MARY PAULSON p. 26-27 ‘Arc’

BENJAMIN HUSBANDS p. 46 ‘Study in Semiotics #1’

NATALIE HAYWOOD p. 67 ‘On Yer Jollies’

SODÏQ OYÈKÀNMÍ p. 68-69 ‘my body is a garden’

ADAM PANICHI p. 97 ‘Contrappunto’

RAWAN SOKAR p. 104-107 ‘In the Lament of Identity’

EVE RADVILLE p. 15-21 ‘I am not your friend’

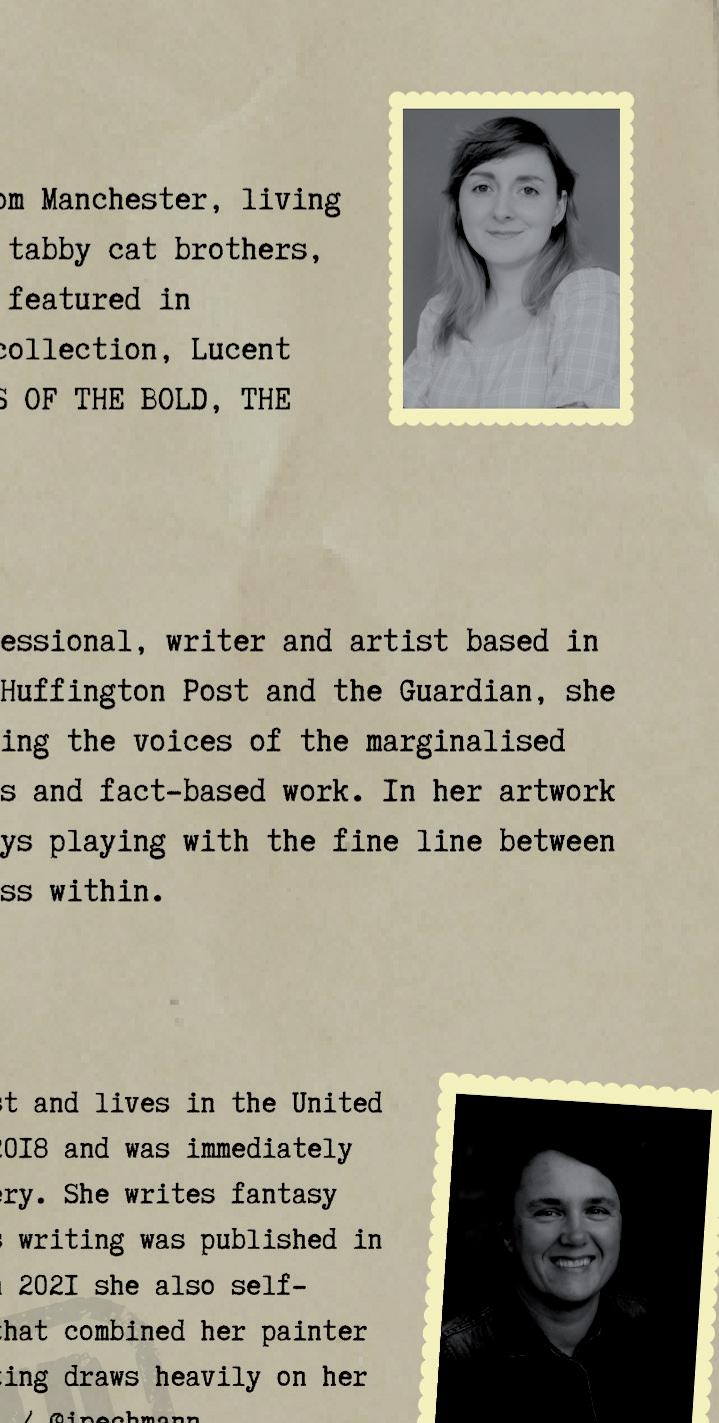

JUDY MA p. 28-33 ‘Temporarily Misplaced’ ILDIKO PECHMANN p. 70-73 ‘Hiraeth’

ANNA NIXON p. 109-113 ‘Orange on the inside’

ANA BALACI p. 7-11 ‘I dream of Sarmale’

PX p. 48-53 ‘A journey of adoption and identity’

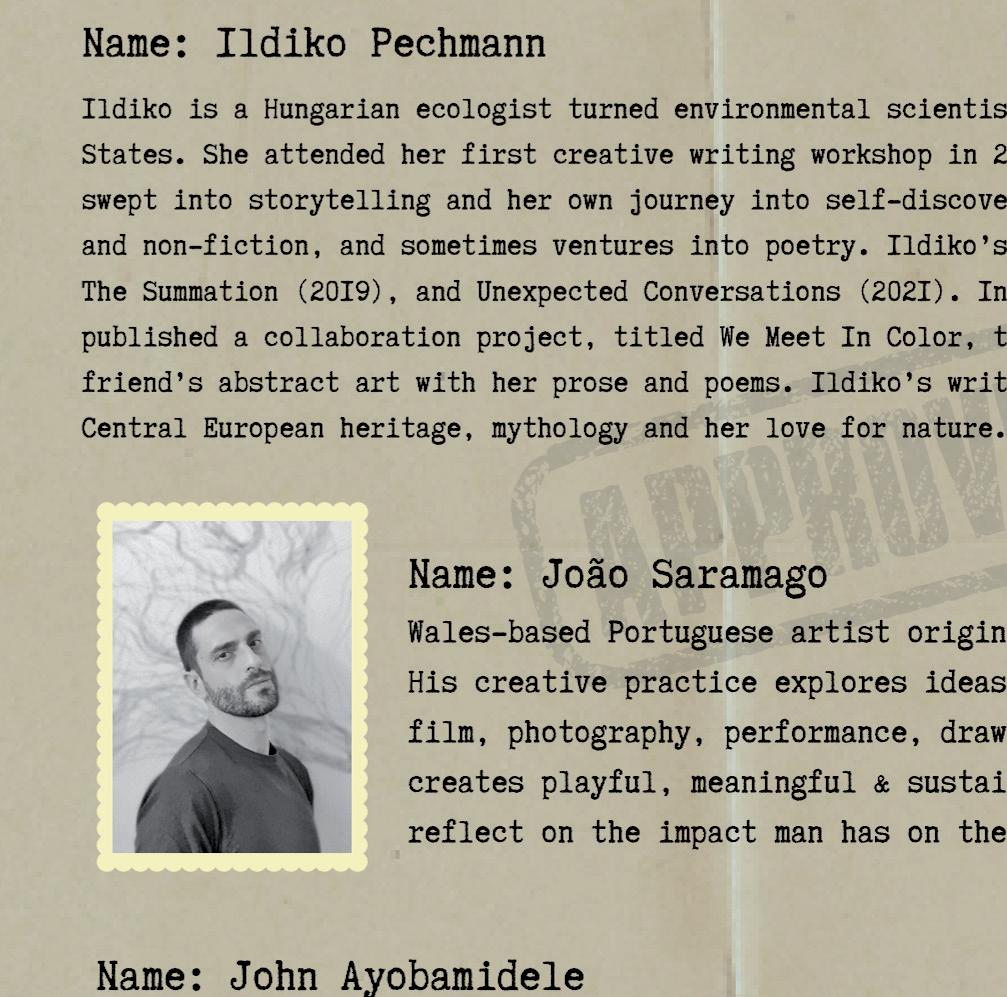

LAETITIA LESIEURE DESBRIEREBATISTA p. 74-79 ‘But where are you really from?’

SERGEY GUSEV p. 90-95 ‘On the other side of the barricade’

DIEGO FABRICATORE p. 99-102 ‘War belongs to others’

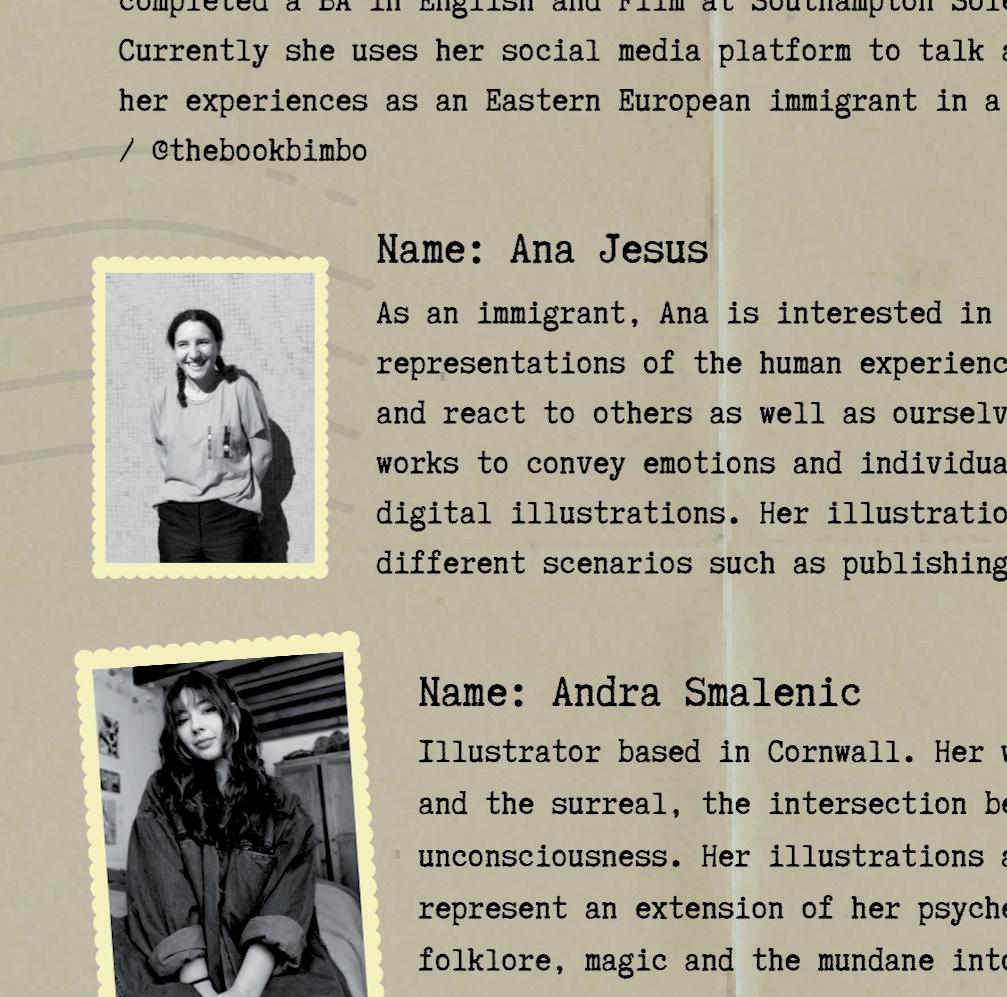

ANA JESUS ‘Diaspora’ p. 6

ANDRA SMALENIC

‘Heavy Coat’ p. 8-9

‘See you soon’ p. 11

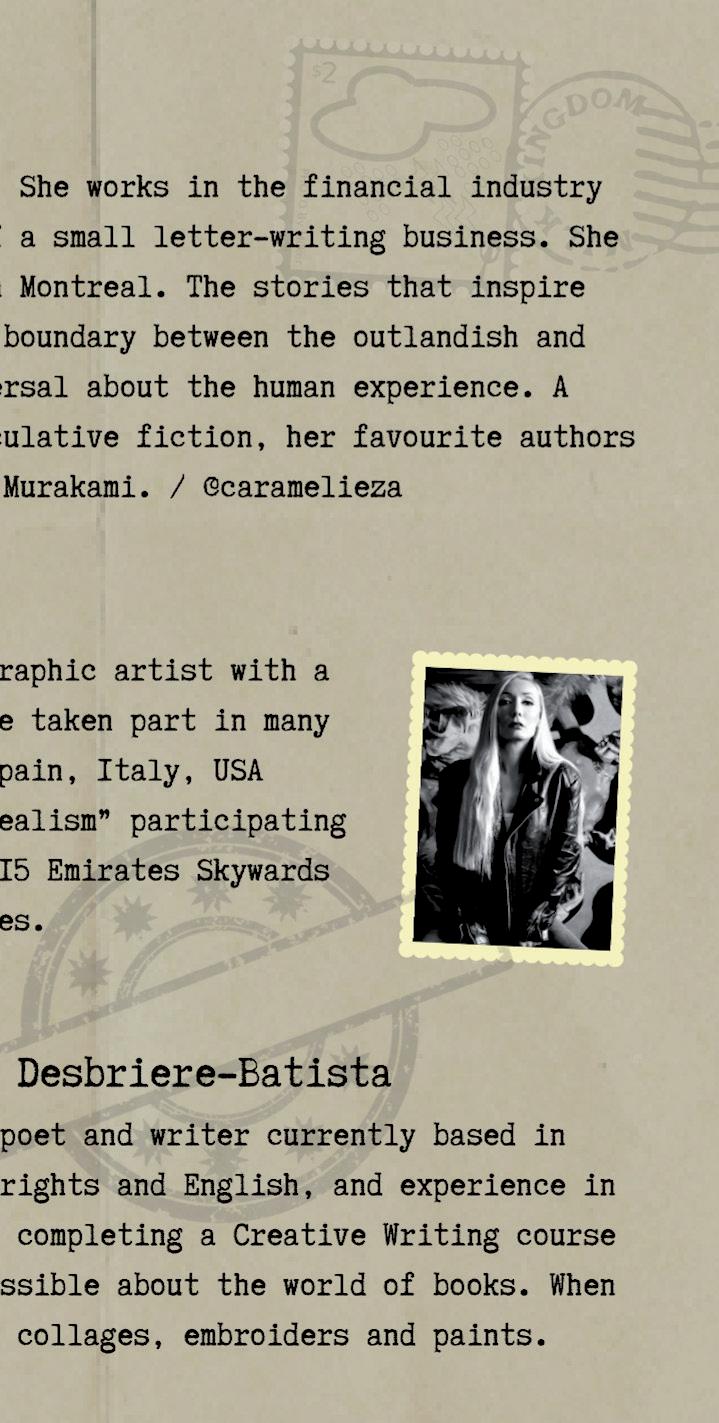

JOÃO SARAMAGO

‘Invisible Matter’ p. 12-13 ‘The Betrayal Cycle’ with Auntie Margaret p. 46-47

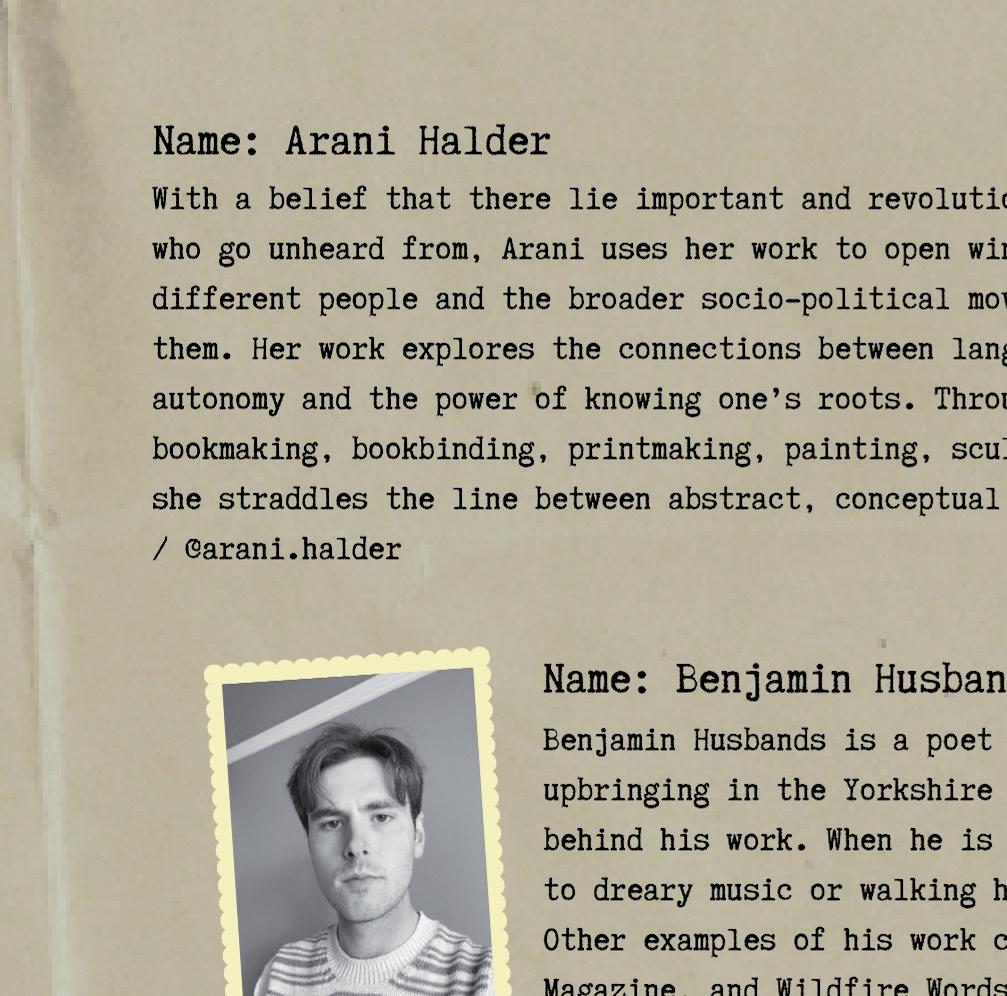

ARANI HALDER

‘People, Period’ p. 22-23 CASSIO ‘Urbana’ p. 27

MUGIRE PEACE DAVID ‘Icon 02’ p. 25

JOHN AYOBAMIDELE ‘The Journey so far’ p. 66

E.L. RODRÍGUEZ

‘Care for you, care for me, care for all of us’; ‘Cycles of time, growth and joy’ p. 68-69

XINAN YANG

‘I Still Care’ (series) p. 70-73

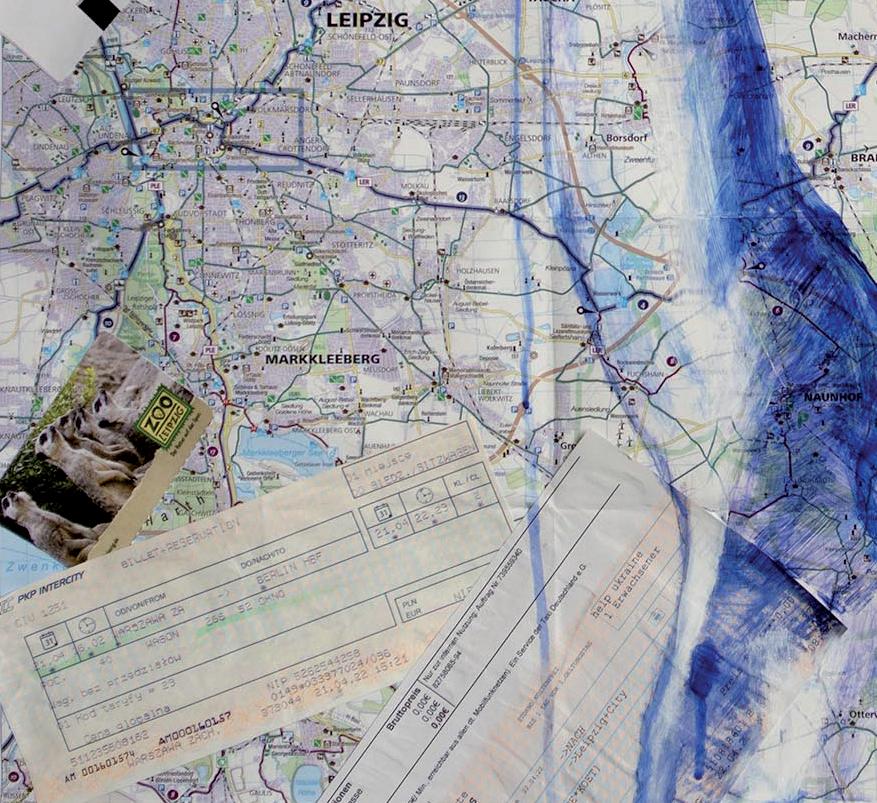

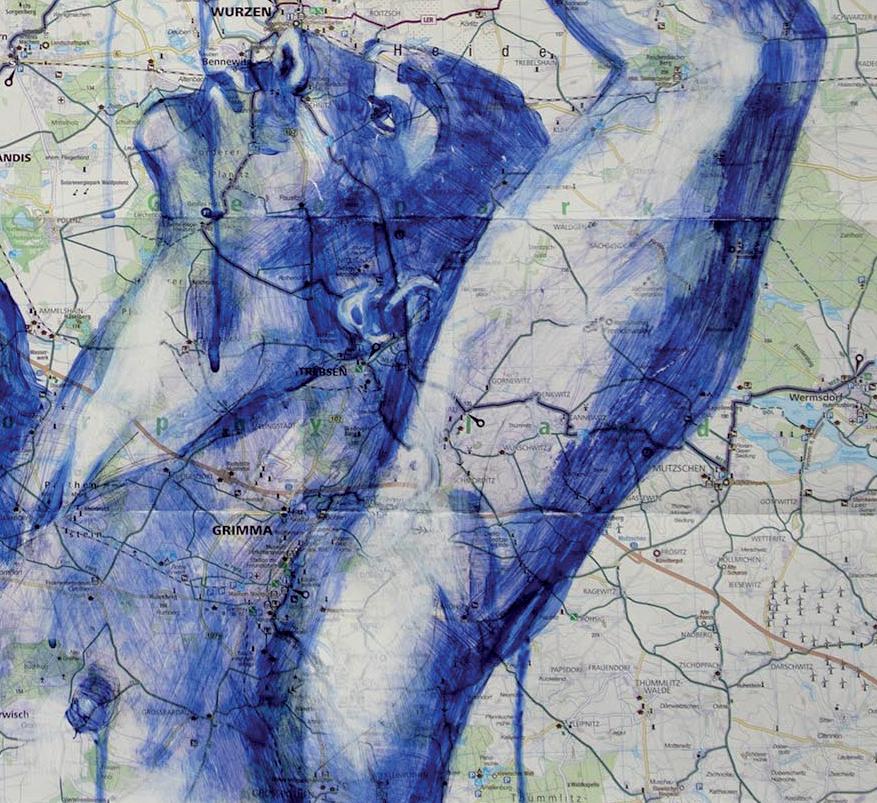

KATERYNA BORTSOVA

‘A way to my heart - Italy’ p. 96

‘Way to my heart London’; ‘To Catch the Leipzig’ p. 98-101

ALEJANDRO MACIAS

‘The Space Between’ p. 103

NATALIA TCHERNIAK

‘Repainted Self’, ‘Drowned Self’ p. 104-7 TARA LYNCH

‘I Heart Dublin?’ p. 108

PASCUAL + VINCENT

‘The Saxons of Transylvania’ p. 34-45 SIPHEPHILE SIBANYONI

‘The Last Defenders’ p. 54-65 MATHUSHAA SAGTHIDAS

‘Not just Brown, not just Indian’ p. 80-89

The first time I set foot outside the borders of Romania, I was emigrating, alone, to a country I had never seen outside the screen of my television or the pages of books. I was freshly twenty, my whole life packed into one big suitcase as well as several reused grocery bags in the back of my father’s Dacia, and I was ready to start my new life, one I had imagined myself living for the past four years, the life of a student in the UK.

I was filled with the kind of idealism that is reserved only for the blissfully unaware.

In many ways, having been born in Romania, in 1995, only five and a half years after the Romanian revolution, meant being born into a generation and country in transit — from dictatorship to democracy, from socialism to capitalism, from outdated technology to the shiny, new, globalised world of the internet. It is perhaps not unthinkable, then, that so many of us, born during that time, find ourselves now in a perpetual transitional state as immigrants living in the West.

Most of us were brought up longing for Western freedoms and commodities — not least degrees and careers that our country simply could not offer us. In our minds, we saw ourselves walking the streets of Western capitals such as London, Berlin, Amsterdam or Paris more readily than we did the streets of Bucharest, Brașov, Sibiu or Cluj. In many ways, we had left Romania long before our physical departure was to take place.

* Sarmale is a traditional Romanian dish consisting of stuffed cabbage or sometimes vine leaf rolls. Variations of this dish exist across several regions both in Europe and West Asia. They are believed to have originated in Turkey, however they are a multicultural dish. It is this multicultural element, this shared familiarity, that, to me, makes them the perfect dish.

A contributing factor to this phenomenon is of course the internalised Westernised lens through which many of us were made to see our homeland. If you are to look up emigrant Romanian thinkers, writers, or artists, of which a considerable number constitute the literary canon, you will soon discover many of them vehemently denied and distanced themselves from associations to their Eastern roots, disparaging their own culture, portraying it as primitive and backwards, its cities as dirty and dilapidated. Proximity to the West and, even more so, assimilation to the West is then understood as the only viable path to success.

For me, and other Eastern European immigrants my age that I have spoken to, this internalised Western gaze was quickly dismantled when we found ourselves living in overpriced, dingy flats in the UK, which often had mould and rat infestations, and which by comparison made our parents’ flats in brutalist apartment blocks in our home countries, with their insulated walls and lack of wildlife, seem almost an oasis.

Moreover, the intense individualism and fanatical capitalist ideology so deeply ingrained into Western culture constituted, for me, a real culture shock. Upon voicing my frustration with the downward social mobility element of migrating to the West, I was faced with several replies telling me I must just be lazy, if only I was willing to work 80 hour weeks, I too could reap the benefits of a mid-management position; if only I let myself be exploited, I too could be the good kind of immigrant.

In 2015, after my father dropped me off in my small university dorm room. As soon as the door closed behind him, I burst into tears. Going from seeing my parents every day to the realisation I didn’t know when I would see them next was, naturally, a shock and my reaction, looking back, was symptomatic of a realisation I would have again and again over the years — the realisation that coming from a culture in which community plays a central role, I now found myself within a space and a culture in which individualism reigned supreme.

It was with all of this in mind that I began speaking about my experiences online and discovered a whole community of Eastern European immigrants who felt similarly, who related to my experiences and I to theirs.

‘Heavy coat’ ANDRA SMALENIC

Romania — and, more broadly, Eastern Europe, but particularly the Balkans — exists in a liminal cultural space, simultaneously too Eastern to be found acceptable by the West, and too Western to fit in with the true East. This state of inbetweenness, so prevalent in the region and which comes as a result of many factors — such as its socialist past, the threat of Russian imperialism, as well as Ottoman influence — is a perpetual source of disagreement and division, both within the region and outside.

And nowhere is this more evident than online. “Still western” someone comments on a video in which I voice my frustrations at the blatant Xenophobia I have faced as a Romanian immigrant in a post-Brexit UK, or at having my culture appropriated, misrepresented and reduced to what is ultimately a xenophobic and antisemitic myth in Dracula. Similarly, on a video in which I talk about the elements of Romanian culture I often find myself homesick for, such as our food — oh how I dream of sarmale, aubergine salad and halva — or traditions and superstitions such as the evil eye, I received comments like “pseudo turk” as well as accusations of “trying to be middle eastern”.

Alternatively, on a video in which I talked about the fact that Eastern European

‘See you soon’ ANDRA

SMALENICparent-child relationships — or rather family-child, as extended family often plays a significant role in the Eastern European child’s upbringing — are not as transactional as those I’d observed in the West, I had an influx of comments implying we are leeching off our families by allowing our parents to help and support us by not asking us to move out at eighteen.

Such is the fallacy of social media platforms, which while their social aspect indicates a play at community, they constitute predominantly Western-centric spaces and more often than not actively encourage and promote division. At their core, these platforms are agents of capitalism and while we are being sold the idea of community, ultimately division is far more profitable.

But what does this mean for Eastern Europeans today whose countries teeter on the edge between such opposing entities, East and West, with both having a marked influence on our culture, our ideology and our perception of the world as well as our place within it? In many ways we belong to both, and we belong to neither. More than that, when we do belong, often times we discover our belonging to be conditional.

Can the liminality of Eastern Europe, and its relation to the periphery, bridge the gap between East and West? I’m not certain. In many ways the West has worn out my idealism. Yet the home I know, Romania, the one I find myself homesick for so often, is one that exists within this intersection. And so, like many others in my position, seduced at first and later burnt out by the West, I dream of the familiar — of community, of belonging, and of sarmale, just like the ones my mother makes.

My a alsa bewa mil vledhen y’n taves ma Kyns my dhe gothhe

Y leverir ny wra nevra dos mas Dhe daves re hir Mes ow thaves yw Le efan, sita kov May hallav omystyn ynni Kepara redenen owth ankrullya Dell wra ow thaves omystyn pell

Taves poran hir lowr Rag gul pons dres keynvoryow Ha treusi kansvledhynnyow

Taves may hwra ilow Rolya war’gan morebow Ha’gan kerghynna Ha’gan dewana

Hag yth o dasjunya gensi Mammdra, mammyeth Kepara: Gwia gwias

Tarenna tan an golon Tevi eythin yn garden rewlys Ystyn leuv ha drehevel dorn Lenwel lester, ayr y’n skevens Bewa nowydh

I could live a thousand years in this tongue Before I got old

They say never does good come Of a tongue too long But my tongue is A vast place, a city of memory That I can stretch out in Like a fern unfurling As my tongue stretches far

A tongue just long enough To bridge oceans And span centuries

A tongue where music* Rolls onto our shores And surrounds us And permeates us

And reconnecting with it Mother city, mother tongue Is like: The weaving of a web The thundering of fire in the heart† Growing gorse in an ordered garden Reaching out a hand and raising a fist Filling a vessel, air in the lungs Newly living

*or sea mist †or enthusiasm

BY SIRIA FERRER

BY SIRIA FERRER

Besides, Amy already had friends. When she’d started secondary school it had been a little rough. She wasn’t as pretty as some of the other girls, or as fashionable, but over time she had found her flock. She’d learned how to hitch up her skirt and plait her hair in a way that showed everyone else around her that she belonged. Now, her and Lucy were inseparable. She wouldn’t let anything get in the way of that.

Lucy had the best way of dealing with Ugne. She would look at her, smile sweetly and say: “Look love, I don’t want to play, but you see that boy over there, the one in the green jacket? He’d love to. Tell him Lucy said he’ll play, okay?”. She nearly always picked Noah, because Lucy fancied the pants off Noah, but to keep Ugne off the scent she’d sometimes pick someone Amy fancied too, and tell Ugne to say Amy sent her. Luckily, Amy had a new crush every week.

Ugne would approach, and the boy in question would laugh before she even opened her mouth, looking over to Lucy and Amy giggling in the corner. Noah was starting to clock on. He craned his neck to look past the weird girl and shout back at Lucy: “At this rate, if you fancy me so much you’re gonna have to ask me out yourself, you cheeky cow!” She gave him a flirty little wave. Amy couldn’t help but reflect on what a genius Lucy was.

Lucy made Amy feel so confident. Like what people thought of her didn’t matter.

Amy was in the toilets, washing her hands when she saw Ugne approach. Not today, Satan. “I swear to god, if you ask me to play cards again, I’m going to lose it.” She did not need this. The girls’ toilets were a sacred place where everyone could catch up away from the boys. Not a place to get propositioned by some freak about a card game.

“Why you don’t like khards, Amy?” Ugne asked, looking sheepish. Her English was getting better. “At home, I play all the time”.

Amy was losing patience. “You’re not at home though are you? You’re at school.”

“My friend. At school. They always play with me”. Ugne was looking at her stubbornly. “You must play”.

Exasperated, Amy looked at Ugne. “I’m not your friend. And I never will be, Oooga Booga.” Ugne just looked her in the eyes and shrugged, putting the cards in her pocket.

She didn’t approach Amy again.

She was excited, but she was dreading the fact that there were journalists present. They always asked her about her name. Some of them even did a little internet search and found out it means fire in her native language. Then they always ended up writing something patronising about how it was only natural that a society which had been pagan for so long had borne an artist so in touch with her roots, ‘wrought in the fires of her traumatic early years’. It was always something pretentious like that.

The worst were the ones who realised that other people back in Lithuania also had ‘interesting’ Lithuanian names. “Your names all correspond with the elements, don’t they? I definitely met someone whose name meant fog in Lithuanian, I’m sure of it.” Ausra. Meaning ‘dawn’. Ugne thought wryly of how no one blinked an eye about meeting an English Dawn. It was only a foreign one that caused so much consternation.

It was Ugne’s first big gallery opening. She had never expected her art to take off so stratospherically, especially so quickly. She’d only just turned 24!

Is a book that is tailored to women of the Indian Peninsula and is aimed at addressing the stigma surrounding menstruation in South Asia, while also raising awareness on safe menstrual health.

It contains anecdotes from the people of the peninsula, age-old remedies for menstrual health issues, suggested sustainable menstrual products, Hindu myths surrounding the process and the science behind menstruation.

Having grown up in Northern India, I have either witnessed or been subjected to the limitations of menstrual equity there. There is a culture of silence around menstruation; discussing it is often treated as taboo. People on their period are often excluded from society because they are seen as impure; and schools often neglect to teach about reproductive health. Through my work I aim to give back to where I come from by providing a wide and inclusive lens on the topic.

My artist’s book is meant to aid conversation and allow people to be able to explain menstruation to their children and loved ones. I want my experience as a South Asian woman to help facilitate such discussions so that the world can be a more (menstrual-y) equitable place for future generations. In a time where bodily autonomy and agency are being limited and challenged for people who menstruate and can give birth, ‘People, Period.’ aims to give back a small aspect of one’s right over their own body.”

MARY PAULSON

MARY PAULSON

Between the East and Hudson rivers ambulance sirens pierce the air, window air conditioners shake with devotion

and all night, squares of egg-yellow incandescence burn in the city’s windows.

Behind the glass, brick, steel and structure, millions of private galaxies buzz with soft, audible energy. The door from our apartment is open to the black tar roof— there are no stars, just a ghostly pink-white light—

I was born someone small under the sky. They told me wherever I went, God would always be there. I imagined God lived in my suburban Jersey backyard, that when the clouds broke and sunlight streamed radiance from a narrow fissure far above, I was seeing heaven.

Here we lie together— you in your universe, me in mine—

Everywhere I am, my heart beats alongside something else, also alive—

At the street level, chaos reigns gently. Nearby, under the dome of Avery Fischer Hall, violin music shatters and dissolves into snow.

Much farther away, there are white birch trees that spread like angels across Russia—

In New Mexico, the vast, flat mesas recede into a wide western sky. Along the

northern and western borders of the Himalayas, great feeding rivers are born to flat-bottomed valleys.

The gradual northward drifts of the Indian subcontinent shake the earth and the Andean foothills descend with grace towards the Amazon before kneeling to the Putumayo and Napo waters. I was born like everything else, small under the sky—

‘Urbana’ CASSIO

Still in the queue were eleven other jobs, and Beth’s thesis was ninth in line. In shorts, she waited, pinching her bare legs as the printer regurgitated the works of complete strangers. She wondered how the other students were so confident, letting anyone passing by judge their writing; unlike her - timid, cowering beside the printer - scared that others might regard her work as worthless.

All around her was the swoosh of paper sliding into the output tray. Beth caught some lone words, but they could just as well have been snow on a disturbed TV screen.

The longer she stared, the more she felt the thoughts in her head slow down. Something fuzzy stirred in the pit of her stomach, tickling her from the inside. It was the feeling of being on a ride through the country, when she pressed her forehead against the cool window and felt her eyeballs squeezed when the train sped past a dense row of trees. It was as though something deep inside her had been drawn out of her body and discarded between the trees far behind.

Before she knew it, that part of herself had become irretrievable. If she kept staring at the paper and printer, the hypnotic sound and movement might cause her to lose a fundamental part of herself. Within a day or two, she might notice a change in her usual way of thinking. If she raised her hand, she’d see it turn flimsy, white, without any nerves, sinew or bones; and when she heard the beep, she’d willingly feed her non-hand into the printer. Then the cycle would continue with her other hand, her arm, moving down to her leg, until every part of her was decrepit and flat.

At least, the sensation was familiar to her. She still remembered it from years ago: diving head-first into water, leaving behind everything she knew. The cold quickly seeped through her skin and spread to her lungs. She felt the little icebergs in her body crackling and melting; then, what seemed like hours later, the frozen bits connected to form a new heart and other organs, so even though her appearance was the same, she had changed on the inside in a fundamental way. What troubled her was that when she looked in the mirror, it wasn’t clear what had changed.

Beth blinked. The long week had drained away her energy. The all-nighters made her question her sanity and wavered her grasp on reality. All she had left was to watch the printer spit out the result of her work. What was it all for, really—a stack of paper covered with baffling markings. Yet it had been her night and day; the totality of her best and worst days in the last four months recorded in this paper. Her word choice and sentence structure reflected the novels she read. There was a clear contrast in style somewhere between the sixth and eighth page, which she had written during the three days she had read all of one author’s books before moving on to continue her surrealist phase.

Did she set out her research well enough? Only the opening sentence still resonated with her; the rest lost in a hurricane of her own anxiety. The proof of her existence was this dissertation. She’d put everything in it. And what if she still failed, or had to resubmit again? Did it mean she had learned nothing, and had left everything she knew just to achieve nothing?

She remembered the other world vividly. The place she lived in before she dove through the water and had her insides reconstructed.

If a mysterious figure approached her in the library at midnight and gave her a choice between telling him all about her home or to have every memory of the place taken from her, she’d choose to share all of her memories with him in an instant. It wouldn’t matter if they’d never met before.

She’d answer every one of his questions with as much detail as she could muster; tell him about her childhood, running through the soft and pillowy blue and white fields, craning their necks to gaze up at the rice paddies; about the cats that leapt from branch to branch, their little paws never touching the ground. Tell him how in the mornings, children floated in their pyjamas, until heavy backpacks helped them drift back down to the carpet. Tell him about her school, then recall everything she’d been taught growing up. She only knew trees to grow down towards the skies, and how easy it was to pick apples from the trees that were five meters tall but reached her shoulders.

If he asked her if they were always flying, she’d try to explain. It wasn’t ‘flying’ exactly. She’d try to please him with words like ‘floating’, ‘gliding’, even ‘swimming’. But eventually, she’d give up and explain that there was a word in her language that perfectly summed up the mechanics of the movement, but the word had no equivalent in English. They could move in an efficient manner, even though the gravity did not apply in the same way as it did on Earth.

“So, it’s like walking on the Moon?” the stranger might ask.

Hearing this, Beth would shrug, and reply “Kind of”, so at least he had a point of reference and hopefully be satisfied with it.

It wouldn’t be a tell-all if she neglected to recall what the lessons were like at school. How they were interesting at first…seeing mice transform into teaspoons, the soft fur disappearing and the skin turning silver, the body frozen as though anesthetized, only the neck extending, like a

But she wouldn’t be able to answer when the stranger asks her why she left. There was nothing she wanted to elaborate on about that topic, and she would stop suddenly, as though he had touched a bruise that hadn’t healed after so many years; she would ask him to leave, to protect it from being prodded, especially by someone she’d just met.

The other day, when her eyes were red from lack of sleep, and the third cup of coffee made her heart beat so fast her head spun and her neck ached, Beth opened up the suitcase. The smell was not as strong as she expected. She had thought the scent of her past would be overwhelming, that she’d start crying from the force of the memories.

The Val in this picture was also taken from behind. She found the photo in her coat pocket, creased down the middle, from years spent tucked away in the case. Val’s face leaned slightly to the right so Beth could see the bridge of her nose. Her hair covered her eyes. A hint of a nostril behind a black lock of hair. A hand tucked into the coat pocket. The same coat.

On the floor of her room, she reviewed the scenery in her head, expanding upon the limitations of the picture. She recalled the food stalls on the other side of the bridge, the churches, the sound of a river from afar, chasing a hat that the strong wind had blown away. The trees and the students under the canopy’s large shadow, flames appearing out of their palms. And she’d remember the heat from the flame conjured in her hand, the way it lit up by taking warmth from her own body and left her shivering, until Val put the coat around her. The same coat. And she closed her eyes, trying her best to fall deeper into the memory.

In the waking hours, especially in the early mornings, she would be filled with regret, until the moment she drank her coffee and walked around her apartment with her feet firmly on the ground. She relaxed when she turned on her laptop, or flipped over a textbook, and returned to the numbing hum of her rigorous study schedule.

At night, thinking back to those days, to the buildings, to Val, she would sometimes lie awake, knowing there was more to this world, to this city, to the grind. She knew she would never go back, even though sometimes she considered it more than a possibility. But also knew that she’d never truly belong to any one place.

The printer beeped. Twelve out of twelve jobs completed.

Once the semester ended and the holidays began, maybe she might meet someone new, and catch up with old friends—even the ones who couldn’t be bothered to reply to her text now. In a couple of months, they may need to rely on each other to cast away the feelings of homesickness and inadequacy. She would lessen her grip on the past once she had a clearer picture of the future.

But today, the machine spat out waste, page after page. Words that no longer made sense when put onto paper, just taking up space. And Beth found herself missing the furry teaspoon, sometimes with the tail still attached.

‘

Pascual + Vincent are two Spanish photographers collaborating as a duo since 2013. The human condition is their field of personal and artistic action, and their work proposes a polyhedral and transversal vision in the way of seeing and understanding that relationship between the human being and the space that surrounds it.

The Saxons of Transylvania’ is the second part of a trilogy that began in 2014 in Romania with a first project: ‘The tree of life is eternally green’. Both works have been published by the English publisher Overlapse, and have received numerous national and international awards.

www.pascualvincent.com @pascual_and_vincent

The Saxons of Transylvania is a photography work focused on ethnic German Saxons returning to Transylvania to preserve their distinctive heritage built up over eight centuries.

Although they were born in Transylvania, their identity has been coloured by World War II and the Communist period, when most of the population was expelled or fled their towns and villages.

Their civilization, now vanished, is being recovered by a scattered group of people we have portrayed. These ‘last Saxons’, are trying to rebuild the past and to forge a future for the Saxons in Transylvania, which is still uncertain.

***

According to legend, in the German town of Hamelin, a mysterious man appeared one day, who with the help of his magic silver flute, offered to release the village of its plague of rats.

After successfully finishing the job but without receiving his promised payment, the colourfully dressed piper returned while all the adult villagers were in church. This time he used his flute to exact revenge, bewitching the local children and luring them to follow him away.

At Poppenberg Mountain two stone crosses were later arranged (in reality) marking the place where the children were thought to have disappeared. Legend says the mountain opened up and the children travelled underground until emerging from a cave in Transylvania, where they settled into seven cities.

Over 500 years later, Goethe wrote a poem based on the story and also referenced it in his version of Faust, but the tale written by Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm is the best known around the world. Convincing theories exist to believe the literature about the Pied Piper of Hamelin was based on fact, inspired by the colonization of Central European territories by King Géza II of Hungary in the 12th century.

To defend against Turkish and Tartar invasions, ‘locators’ were hired to recruit young people from populated areas in the Moselle river region and then lead them to settle in Transylvania and fortify border towns. They cleared forest land and founded villages in exchange for legislative privileges and exemption from paying taxes.

search of their roots. They have created associations and foundations whose aims are to follow strict rules for classical preservation using traditional craftsmanship, respecting the architectural achievements and artistic creations of the original Saxons of Transylvania. Additionally, they help energize underdeveloped urban and rural communities in their social and economic recovery, and support sustainable development.

Great stories are always made up of a series of smaller ones that give meaning to the whole. The Saxons were born from ethnic origin but also diversity. There are many stories to share about them; who they are now, how they arrived in Transylvania, what they represented, and their evolution over a period of eight centuries.

For this reason, we explore their sense of history and how that diversity constitutes a richness in need of greater awareness and understanding. Given that their stories are complex and entrenched in medieval lore, we could lose ourselves in seeking out the origins of their history, like the mist entangled in the summits of the mountains.

I’ve always had trouble identifying myself. Who am I and where do I belong? It wasn’t until I lived abroad that I discovered I usually was “sasoaica” in Romania, I was “Rumaenin” in Germany, while in Switzerland people’s first guess was “Deutsch”, and in England “Continental”, altogether “European”. So a matter of perspective and choice, I thought. But how do you make that choice?

In a moment when I didn’t know where I belonged anymore, I searched for my peace in Cincu, the little village of my maternal grandparents. This village had always been the scenery of my dreams, and it was the one escape I intuitively fled to when in doubt. When it was time for me to change perspective.

Born and raised in Bucharest, I grew up speaking German to my mother and sister, and Romanian to my father. Since my grandparents on my father’s side had died before I was born, I used to go to my mother’s parents during school holidays.

My memory of Cincu has always been embellished with an abundance of fruits and flowers, myself sitting under my pear tree, surrounded by ducks and geese. Or with the sweet smell of cinnamon and nuts and rum from my grandmother’s Christmas baking, alongside “Stille Nacht” played on trumpet through the sparkling blue night and real candles in the Christmas tree. Or Grandma’s Strauss waltzers she played in the evenings on her harmonica with lights in her eyes, remembering when her father came home - from working as a carpenter in Vienna during winter - with all those new and exciting Operettas. And stories of the Siberian Lager (concentration camp), the cold, the fear and the bitterness that follow me to this day like a chemical taste in my mouth when I hear the word “war”.

The first couple of years after moving to Cincu I could not change anything in the house. Every drawer I opened played the movie of my memories in search of understanding my own move. Only after I met Alex did I feel the circuit was complete. As if I closed the circle of my ancestors’ unrest. Living and working together, researching the ‘whys’ and the ‘hows’ of our ancestors and sharing their wisdom of harmonizing with nature through our SOXEN NGO and KraftMade project is a fascinating journey of joy and discovery. Here is where I feel connected, at home and at peace.

BENJAMIN HUSBANDS

BENJAMIN HUSBANDS

I

David Lean landscape, atomic tangerine to pantone 19-4035.

II Yorkshire expands, the land subsides and the springtime sighs escape collapsing mines.

III And with great ceremony, you look at me for the first time.

IV

And I’ve known you my whole life – at least that’s what it feels like.

V

Like something cinematic –the great swell, non-diegetic. And maybe that’s it. Maybe

VI the currency of affection is polished parquet flooring and pink ladies browning in their

VII cellophane; the two of us homesteading, horizoned, on a frontier of our own making.

‘The

Over the years, I have always questioned who I am, where I’m from and why my features are different from my family and friends. I spent a lot of time studying myself, trying to comprehend what makes me similar…or different, and trying to put together the pieces of the puzzle, despite knowing there are some pieces that might remain missing forever.

What I’m about to describe is a very personal (and totally subjective) history. A retrospective look at my journey through adoption and identity, which can’t necessarily be extrapolated to the lives of other adoptees.

My name, although I won’t reveal it in this text, is the same as many others’, except that throughout my life, mine has always been accompanied by an expression of surprise. A gesture of unease, as if people expect my name, or surname, to be more…‘exotic’. Like me, I suppose. But what is a name, apart from a mere signifier of identification?

At the age of 10 months I was adopted in Nanjing, China, the city I was born in. It became the centre of an adoption boom in 1996, following the broadcast of a documentary called ‘The Dying Rooms’ a year earlier, which exposed the reality of orphanages in China, struggling with the massive issue of abandoned girls caused by the country’s one child rule.

My adoptive parents, although from different regions of Spain, had settled in Ibiza, which was to become my home following the adoption, and for the next 17 years, until I moved to Valencia to study medicine, and two years ago to Asturias, where I’m completing my placement.

My adoption was one of the very first between China and Spain. My parents didn’t have it easy, and had to fight extremely hard for my adoption to go ahead. They managed it in the end of course, but only after two gruelling months of travelling back and forth across China between the orphanage and the embassy in Beijing.

Finally, on the 2nd of September 1996, the adoption was approved and I arrived at a new home with my new family. This was an absolutely radical change which separated me from my native culture and biological family. With a new family came a new culture and country to discover. It was a reality which I would come face to face with many times in years to come.

Two years later, my parents also adopted a second Chinese girl, from a different region to mine, who became what I now know as my sister. With the excitement that a two-year-old girl might have for seeing (and giving a name to) their new baby sister, I visited China for the first time. Although I obviously don’t remember much of the trip, from what my parents later told me and my sister, it must have been quite the event.

One of the highlights was getting lost as we walked out of a shadow puppet show. How would they find me in a room full of Chinese people? Easy - I was the only Chinese girl who didn’t understand Chinese.

This is when I started to identify with the phrase: ‘neither one nor the other’.

Following this first encounter with my origins and those of my sister, we returned to the rest of the family in Spain, as we had the first time I arrived. My sister’s birth city, Wuhan, the now famous (thanks to the recent pandemic) capital of the Hubei province and the most populated city in central China, was also one of the sites with the highest incidence of abandonment of girls.

I’d like to talk shortly, before continuing, about the mark that adoption leaves. It’s a feeling which becomes ‘embedded’ in all adopted children, and implies abandonment by the biological family, and an abandonment of their culture. An abandonment which sticks in the mind, above all in small children - in the so-called ‘implicit memory’. This imprint remains, and only through a therapeutic approach to parenting can the wound of this abandonment start to heal.

At the end of the day, abandonment implicitly carries with it the message that the person is of no worth, doesn’t matter, and is for that reason, abandoned. This is a feeling that I have known for many years, much like many other adopted children. It’s not so much about the ‘why’ of abandonment, but rather the fact itself of having been abandoned. There could be a justifiable cause, but it would still be an unjustifiable situation.

I’ll now continue with my biographical story. Throughout my years living in Ibiza, as is to be expected, I had some good moments and some worse ones. I remember, as a child, how I thought I looked the same as my mother. I couldn’t see any difference in our features. I looked in the mirror without ever noticing any of my Asian features.

It’s interesting isn’t it? How the feeling of belonging to a place or a person, in this case a family, can transform your perception of your intrinsic identity.

But that innocent, natural feeling, perhaps naive, was short-lived, when I was mocked in school for looking different - because of my eyes or my complexion.

A curious detail about all this, which I wasn’t aware of at the time but now understand, is the fact that I only suffered this type of abuse from newly arrived classmates. Those that I’d known since preschool treated me the same as everyone else. It was only those that later joined my class in years to come that singled me out as different. Insecurity, the feeling of wanting to fit into an established group…which neither I nor they knew at that time, was the feeling that they subjected me to with every ‘joke’ or comment or allusion to my ethnicity.

The step up to secondary school was, without doubt, one of the worst periods of my life. Compounding the loss of my old school friends and, as I could not change who I was or my background - which kept proceeding me everywhere I went - I began to suffer a much more intense form of bullying. The mere fact of being labelled as ‘Chinese’ for me started to feel derogatory, even hurtful.

As if the discomfort I felt every time I set foot in school wasn’t enough, at home the emotions that this brought up were not being validated. So of course, I felt alone, misunderstood and hurt. Having to face these verbal, physical and perhaps worse of all, psychological aggressions on a daily basis, opened up a wound for me, so deep that I could barely stand to look at myself. It hurt too much, and at that point I started to emotionally shut myself off from the world.

I never had any real support in dealing with this behaviour from the teaching staff at my school, or from my parents, and for that reason, one day I just simply stopped mentioning these incidents at home.

I managed them by myself, as best I could. But thanks to a few people, who I’m proud to call my friends, who

saw beyond my physical appearance, I was able to bear the weight of those tough adolescent years. As one of the fundamental pillars in my life, they have been without the shadow of a doubt the best thing that came out of that period - and that which followed - of darkness and unrest.

This wound I mentioned earlier kept growing throughout my adolescent years, like an active volcano - occasionally releasing its lava to destroy a small part of its surface, creating ever greater craters in the earth. A wound full of small ramifications, of channels I have navigated along this long journey through identity, a process of comprehension and understanding of my origins and the process of adoption.

All those years of bullying meant that I never wanted to accept my Chinese identity, because being Chinese was what made me different and the subject of jokes and abuse. This left me with an internal battle between my Spanish and Chinese identity, in which my Chinese side had been gradually diminished.

I’m now aware that it’s just as important as my Spanish identity. Because I am both. Over the years, people have tried to pigeon-hole me into one of the two categories, without letting me be both, while these last few years of self-discovery have led me to realise that I am, and want to be both. I need both parts: they complement each other well and one does not contradict the other.

I am still on a journey of self-acceptance and have only just started to figure out who I am, but I think at least I now have a few more clues about where I want to go.

“I’m now aware that it’s just as important as my Spanish identity. Because

I am both. Over the years, people have tried to pigeon-hole me into one of the two categories, without letting me be both, while these last few years of self-discovery have led me to realise that I am, and want to be both.”

“Initially we used dry grass, sticks, clay, seeds, and shells as materials to make our traditional ornaments. Over time we started to use attractive beads made of plastic and glass that we obtained from other communities through trade. I have had this ear pierced from the moment I got married to my husband.”

Talek, Massai Mara Kenya (December 2015)

This series is the journeys taken in exchange of solace, livelihood, awARENESS AND OTHER ENDEAVORS, WITH THE INHABITANTS OF THE WORLD, THROUGH THE LENS. AN IN DEPTH NARRATIVE BASED ON THE EFFECTS OF GLOBAL WARMING, CLIMATE CHANGE, MODERNIsATION and digitalisation.

Zanzibar beach Stone Town (December 2016)

“We don’t like being here. We need to fend for our families. Sleeping with different women for money in our culture is very demeaning. We are always prepared to receive new tourists”.

“The most painful thing is seeing your peers being on western clothing and leaving the village for greener pastures in the city. Then they get so depressed there, struggling to cope. The man I had to marry turned out to become an alcoholic. He couldn’t cope with city life.”

Himba Land

Kunene District Namibia (March 2018)

“We are not allowed to take our livestock to the grazing fields during the day. Tourists complain of not being able to spot any wildlife. Therefore in the dry season, our livestock dies of drought, thus causing famine in different villages. We pay fines when spotted with our livestock grazing during the daytime. We sleep during the day and we have no roles to play anymore. We wake up at 2am and take our livestock to the grazing fields. Unfortunately the Mara National park is the only grazing land we have. It is pretty risky because wild animals are not used to seeing us in the dark, so they attack us. So many warriors and livestock have been killed.”

- Edward Naurori

Naboisho Conservancy Talek Maasai Mara Kenya (December 2015)

Naboisho Conservancy Talek Maasai Mara Kenya (December 2015)

“I have seen so many deaths and so many births. I am a traditional healer and midwife. Before healing others I start with healing myself. I might be 105 years old, nobody is sure.”

Talek Maasai Mara Kenya (2015)

Land dwellers from Vukuzenzele informal settlement in Phillippe, Cape Town, protesting outside the Parliament of South Africa over a piece of land where they were forcibly removed by Vukuzenzele council’s housing scheme, in order to construct a filling station owned by BP Oil.

Cape Town South Africa

As a bairn, tha school year ran from August t’ June. Our ‘alf term was int’ middle o’ September n everyone would go on holiday ‘cos it were dead cheap. Cos o’ that, it were called the Burnley holiday n when I read Falling Man for me Master’s degree, I asked me mam where we were on 9/11 n she said up in Cumbria int’ caravan watchin news unfold ont’ tiny telly we ‘ad to constantly move the aerial of in order t’ get an ’alf decent signal. One year, tha government decided we should be akint t’ rest o’ country n should change tha long tradition that went reyt back t’ industrial revolution n ‘ave the same school ‘olidays as everyone else. That meant, one year, we got a nine-week ‘oliday, which, to a young ‘un, felt like forever.

Ont’ days that it were crackin’ flags, my mam would make us some butties t’ scran later on n we’d galivant up the ginnel, down cobbles t’ lodge that belonged t’ old mill. Some days, I’d climb up tha waterfall that linked it wi’ upper lodge which were gradely fer using a fishing net in t’ find right small fish t’ have a gander at. N even on days where it wer proper chuckin it down n borin, me mam would tek us t’ library or let us bake at ‘ome t’ pass all 63 school free days we ‘ad. N now, a look back on it as an ‘oliday as rare as tha Preston Guild, where, as wee mill town kids, we were forced to leave ‘istory behind n play catch up.

‘The Journey so far’

JOHN AYOBAMIDELE

from my mouth like morn dew from a baobab leaf they say something must kill a man a virus an ancestral curse a misfired bullet — enough! enough of the post-mortem look carefully & you’ll find the scalpel of this country in my brother’s jugular stretching it’s hands towards my neck your neck our necks

‘Care for you, care for me, care for all of us’ (12” x 16” oil on birch wood panel); ‘Cycles of time, growth and joy’ (11” x 14” oil on birch wood panel)

E.L. RODRÍGUEZ

E.L. RODRÍGUEZ

ILDIKO PECHMANN

ILDIKO PECHMANN

it’s a cool drawing. the colors are of love but of the darker hues. two men in love. well, one of them in despair and the other comforting him but their postures are telling. it’s still bizarre even after living here for almost two decades. there are things that are just strange, like the spellchecker autocorrecting colours to colors or analysing to analyzing. and the woman yelling at you with a southern accent but only after she pulls at her own blouse you realize she wants you to take off your bras for the exam. or the off-duty cop shouting in your right ear and you’re frozen to the spot precisely understanding that what separates life from sudden death is time. time the on-duty cops take to get to the bar, if they want to, that is. or the officer at the motor vehicle commission whose manner radiates that you are something big brown and smelly the horse left on the turf and you wonder if you should tell her you have a PhD, and speak three languages. would that help her see the person? these are not the only memories, though. remember Alaska? the breathtaking flight over Denali. when you glanced through the glass above the Grand Canyon with a baby kicking in your belly. the fetus felt your excitement too. the fall colors in Acadia, the redwood forest, the sight of Alcatraz and the thundering sound of the Niagara Falls. but then you recall the quiet green of Ireland and the narrow roads where you lost a side mirror to an opening door. the misty rain of England and the painstakingly beautiful accent. the infuriating coolness of Amsterdam, the sweet taste of the weed lingering in the air. the stubborn superiority the Germans still exude even after losing two wars. but still! you felt at home in Bonn. people were kind. they took you in. the loud Spanish who were punished by COVID for their love of life. your sister married one. and you’re circling and circling above the heart of Europe. don’t want to but you are going home. the tiny little country that history wea-

thered, cut off its limbs and head but the heart still beats and only the Irish and Armenian would understand what it takes to live surrounded by enemies. the country where people still think that if something is not cured by Neogranormon or pálinka, then no doctor can help. but then here no one understands. just as they don’t know the books you grew up with. just as the puns are lost on them because there’s no way you can translate your favorite jokes or quote the poems that speak to your heart. because you have to see the gentle slopes of the Bükk mountains or the peaceful meandering bank of the Tisza River to understand its mindless rage when it gallops through the plains flooding everything. the feeling is overwhelming so why don’t you go home? home. where is home though? there are a thousand places like home and you just happen to live in one of them. funny that the witch who has the land in her bones would say something like that. roots. you need roots otherwise the wind blows you away. but how long does it take to grow roots? the ones that are strong enough to tether. first, you grow the thin fragile ones to feel out the soil and see if it can nurture, if you like the taste. only then you can grow the thick, sturdy ones to hold you in place. it took the death of your mother to cut your roots for the first time. you wonder just what it would take now. it’s a cool drawing. you used to be in love with one of the men and strangely the feeling isn’t muddled. rather it transforms into a kind of longing to be loved by someone the way he is loved by the tall catlike figure with icy blue eyes. and finally you understand why writing is such a blessing, for finally you can unload a bit of the cacophony that swirls in your head.

This is a question I am never asked, even though in my case it probably deserves to be, even though I wouldn’t be able to formulate an answer that manages to be at the same time coherent, concise and comprehensive.

I am what some call a third-culture kid. My parents changed jobs when I was ten years old and suddenly we had to move, once, then twice and then a third time. Before, I was already the kid who spent the holidays in Belgium or the Dominican Republic to be with family. Now I was the kid leaving our small city in Southern France for Paris, then Bamako, then Montreal.

I remember walking home at age sixteen in glacial streets wishing people would just ask me what it was like, classes starting at 7.30, walking dirt roads in 45-degree weather, eating alloco plantains, spending school breaks visiting Timbuktu, Dakar and Ouagadougou. Maybe if they did, it would get easier to talk about it, to make sense of it. This life.

And yet I also hate when they do ask, who does, and how. I hate how I feel naked revealing so much about myself sometimes to a stranger. I hate when, no matter what I try to say and how much, they will often keep to their first impressions, or the things they think they know about that kind of experience. That this life, this type of travel, is somehow easier and better than a life lived in a single place. That it is a life of financial abundance and fancy dinners with ambassadors and nothing else. These thoughts probably comfort them in the common idea that people with my upbringing truly are brats ‒ army brats and diplobrats, but brats nonetheless.

“I hate how I feel naked revealing so much about myself sometimes to a stranger.

I hate when, no matter what I try to say and how much, they will often keep to their first impressions.”

But the truth is, it was not so then and it is not so now, neither particularly fancy nor easy. To convince them, though, I would have to tell them that there is more to these stories of expatriation, both for the parents and the children who did not choose this life. I would have to tell them how, moving to Paris at 18 after six years abroad, I had no idea how to relate to my classmates. I did not understand the slang they used or their pop culture references. They did not understand my unidentifiable accent or where I was coming from. How, after that, I left again, on my own this time, to Lyon, Berkeley, Paris, New York and now London where I know no one. How my passport is the closest thing I have to a picture of my life these past ten years, and that life has been leaving. And it is my choice now and I have left so many times, but it does not mean it does not hurt sometimes.

I would have to explain that this is how moving feels: suddenly the smallest things, numbers, become imbued with new significance. You count the days since you arrived, thinking ‘19 days ago I was sleeping in another city, in another country.’ Thinking ‘85 days ago I didn’t know I would be moving.’ The first few days or weeks, especially at night, your mind keeps going a hundred miles an hour about all the things that make this place not home. You want to skip all the days until the time when everything will feel natural ‒ unlocking the front door, finding your way through the aisles at the grocery store. You cannot wait until a month or two or three later when these streets have been walked, these names have been spoken and the way to work or school is muscle memory. Until that happens you just have to trick your mind into thinking this is home.

Leaving is easy, I’ll give them that. And not just because it was my parents’ choice then, and now, my own. But because it still feels full of possibilities. Realising that you are not bound to one place for the rest of your life is just freeing. Starting afresh does not mean the problems you had before will disappear, but it is in many ways a second, or third or fourth, chance. A journey to becoming a different you, a new outlook on life and the world. It can be exhilarating to know all that is out there, to go and be part of everything the planet has to offer. And it’s also easy, because you plan and daydream beforehand. Before you even set foot on the train, plane, car or bus that will take you away, your mind is already gone.

Arriving is always the worst though. It’s having to learn to belong. You are familiar with the concept of living here, in this new place. You are familiar with the theory of it. But your body still finds itself having to learn how to exist in the reality of here. The terminology of life and moving through the world of here. The loneliness of having to do it on your own. Arriving is a continuous process. Your body catching up with your brain, pushed back every time you cannot make yourself clear, every time you get lost, every time you look at your phone hoping to become invisible.

Your body is at the core of this experience. Unused to the springs of the mattress, the sounds outside your window, the taste of food. Still unused to being so far from all the places that used to be home and the people who know how to love you. Missing touch, kisses, smells, hugs and hands.

How can I tell them that it is expatriation and that doesn’t mean it didn’t shape my entire identity? How can I explain my fear of being trapped in a place and how I always want to leave? That I am the same and different from my grandmother who left her native Belgium in 1959 and ended up living in five other countries after, the same and different from my mother who left her native Dominican Republic and ended up living in five other countries before moving back to Santo Domingo? How do I tell them my body is erasing my Dominican-French-Belgian-Malian-Canadian upbringing, that I am all and none of the above?

How can I talk about it to people who don’t know and not make both the possibilities and the déchirement at the heart of this life visible for all to see? I do not know how to make people understand who I am without having to let them into the intimacy of me, my experiences, my identities. If I do that, will it even be enough for them to get it? That this life is one of moving and

“You count the days since you arrived, thinking ‘19 days ago I was sleeping in another city, in another country.’”

“Because they know. Because they too know no other way of living than constantly navigating spaces between belonging and otherness, between being locals and foreigners, drifting comfortably between different identities”

leaving and that it’s just a life, with its perks and tragedies, like any other.

Because I have few answers to all of these questions, because the answers I do have take too many words to verbalize, because I both can’t and have to be asked about it, I now find myself seeking people who have a similar experience of life. People with whom I can be quiet or say all of the words and either way I know that they’ll get it. Because they know. Because they too know no other way of living than constantly navigating spaces between belonging and otherness, between being locals and foreigners, drifting comfortably between different identities. But also because they too have felt that very specific type of geographical pain and openness.

Our shared complex history spanning countries and continents creates an immediate bond and a degree of silent understanding that feels like relief and that, since I first left France at age twelve, I have only found with fellow third-culture kids, exiles, immigrants, bicultural, multiracial, ethnically ambiguous diplobrats ‒ Filipinas raised in China living in London with their Italian boyfriend, Salvadoran-Americans studying in Paris, Dominican-French people met in Bolivia, befriended in Montreal and who now call New York home, Lebanese Canadians existing between Montreal and Beyrouth, Koreans who arrived in the US as teens, French girls who had never lived in France before they turned 18. These people are my fellow citizens, the population of an invisible country, connected by our complicated connection to geography. When I catch myself longing for this question, for community and roots, for someone to want to understand the map of me, I know now these are the people I can and don’t have to talk about it with.

‘NOT JUST BROWN, NOT JUST INDIAN’, focuses on the lived experiences and beauty of South Asian women as well as celebrations, traditions and history of South Asian countries from a female perspective.

“As an Eelam Tamil woman, like most other South Asians, I just made the assumption I was Indian, as if that’s the only country to exist in South Asia, as I feel our cultures and traditions are often classed as one (hence the name).

It was as if I was made to feel that my ‘appearance’ didn’t seem to fit the expectation of what some outside or even within the South Asian community believed a Tamil woman should be. Working with SA women from their respective countries, I wanted to show parts of their stories and culture from an authentic perspective - to give them a space and chance to celebrate who they are and everything they have been raised around; and really amplify these stories.”

The images for each country focus on different aspects of its culture.

For India, Mathushaa has focused on the celebration of Holi, by letting the models create a Rangoli pattern (colourful patterns made out of white and coloured rice powder) - something that they would do for festivals. Given that all girls in shot are, in fact, creatives, it made sense to given them the chance to do this.

Nepal focuses on sisterhood and the influence of caste in their culture - by having traditional wear that reflects the caste that their families are from.

Sri Lanka/ Tamil Eelam focuses on the life of our grandmother and what life was like for her back home whilst showcasing the beautiful differences between Tamil and Sinhala culture.

Afghanistan focused on celebrating family and little things that the girls in shot (who are also cousins) would do growing up - such as dancing.

Pakistan focuses on beauty traditions such as the influence of hair oiling and wearing Kajal.

Pakistan focuses on beauty traditions such as the influence of hair oiling and wearing Kajal.

www.mathushaasagthidasphotography.com @mathuxphotos

India

Art Direction: @radhika.photos Styling: @aaishah.p Make Up: @yasitskrishy Models: @shaw.22 / @aaliya.choudhury / @yasitskrishy

Afghanistan

Art Direction and Styling: @ha_ida Make Up: @saida_hoss Models: @fariaaa_r / @susansherifi / @farhat_draws / @adria.pawz

Nepal

Art Direction: @suprinax

Styling and Make Up: @namii.ie Models: @reeyadarnalbk / @ronisha_nal / @rojinadarnal / @suprinax

Sri Lanka/ Tamil Eelam

Art Direction: @bypeoni Styling for Sinhala Models: @sahxni Styling for Tamil Models: @keertspleats Make Up: @rebeccaraveendran Models: @rebeccaraveendran / @nirodha.perera / @lourdesnavo / @workbypree

Bangladesh

Art Direction: @waheeda_art Styling: @asaaaa._.zz / @voidinayah @mariakayum_ / @tartine___ Make Up: @voidinayah Models: @waheeda_art / @asaaaa._.zz / @mariakayum_ / @tartine___

Pakistan

Art Direction and Styling: @armani_sy Make Up: @mariumjeelani Models: @mariumjeelani / @_bismahsaleem / @henab30

have your tires stabbed and your windshield smashed. You see the difference? The police have to hunt the anti-war attributes, since they follow orders, but it will be common people who oppose your display of macho patriotism.

Putin wants a strong Russia, united under his command and the “Z” idea, but what he actually has is two generations of voters who want him gone — liberals, conservatives, libertarians, socialists, even nationalists — all of them want a real political struggle, since the only politician you may find on TV or in federal or regional government is merely a pawn for the regime. All the liberals are made out of plastic, conservatives — carved out of wood, socialists — paper figurines, none of them believe anything they say, none of them represent anything but what Putin needs them to at any given moment. It is a 20-year-long political plateau, a swamp of fake ideas, the future slowly drowning in favor of a single person who overstayed his welcome for a devastating fifteen years.

The catch of Putin’s regime is simple — you can go about your life, being almost free, you can travel abroad if you like, but you can’t participate in politics unless you represent the ruling party or any of the puppet parties. This is the difference between authoritarian and totalitarian: authoritarianism wants you calm and relaxed, it just wants you taxes and the right to rule you, while totalitarianism wants to interfere with your life, it will dictate how to dress and what to read, it requires not only your taxes and political power, it also demands you showing constant active support. Putin used to be strictly authoritarian, and only recently has he created the climate for totalitarianism. Regime hounds on the look for traitors, numerous repressive laws passed every other month, dissident books and books with LGBT content taken off shelves in stores. Meanwhile the economy suffers, and prices rise every other week — primarily due to the suicidal political decision to start a war.

The picture looks dark indeed, but I try to remain optimistic, and I believe that Putin is expanding the bubble of civil tolerance that is about to burst. Since the job market is in coma,

my girlfriend used to play guitar and sing in the streets, and whenever she sang classic Russian pacifist songs, passers-by gave her twice the money she would get usually.

I believe that if you stand alone with an anti-war poster, no one will join you, but if there’s a thousand protesters, thousands and thousands more will

join. There’s an undeniable demand for the expression of pacifist ideas, but there’s no way to express them and be certain of your safety. Here’s one more common phrase of Putin’s era: “everybody understands everything”, meaning that you see through the propaganda and yet remain incapable of any action. Well, with the start of the war this phrase turned too emotional, and the ironic undertone of it is gone. And, like the phrase goes, everybody understands it as well.

The current political struggle is in a way a struggle of generations. Putin surrounded himself with old men, and the only ones who still 100% believe the propaganda are the old people who never learned to use the Internet, whose sole source of news is still state-controlled TV. During the late Brezhnev period in USSR there was a term “gerontocracy” — the power of the old, since you had to climb a long ladder of party positions to reach the near-top, and it took many years of your life to do so. The old ruled the young, prohibiting, arresting, controlling. I was two months old when Putin became president for the first time, and I was 18 when he did for the fourth time. By the time of the 2024 presidential election I will be 24, and there’s a whole generation of people like me, each fed up with corruption and lies, each an individualist in their own way, each wanting to see Russia free and peaceful, integrated into the world, not shut off from it.

Many believe the 2024 election to be the moment the bubble bursts open, revealing all the contempt and hatred for Putin and the system he had been building for two decades worth of lives. Belarus dictator Lukashenko is believed to have just 3% of real support, and I believe Putin has around the same percentage, maybe around 5-6%. The trick is to make the few favoring you vocal, and the majority silent. Any Navalny channel video reaches 4-5 million views in 2-3 days, which is greater than the biggest TV channels with state propaganda.

They make it impossible to speak out, so you believe you are alone in your beliefs. They make it impossible to take action, so you believe you are powerless in your struggle. They double down on law enforcement, so you always feel weak and threatened. In truth, these same policemen will turn against the regime when the tide turns. Recently an ex-policemen turned lawyer got jailed for five years due to a fabricated case, because he was protecting the very rights of policemen. This regime is omnivorous, and sometimes I have a feeling they truly believe they are all-powerful, but in reality they have already bitten off so much more than they could possibly chew, and I believe they are about to find out when it is already too late for them to spit it out.

The famous Russian cinema historicist Naum Kleiman once told a story about how he and his family got deported to the middle of nowhere during late Stalin rule. He was just a boy, and with his family there was a number of deportees, among them a sophisticated old woman. The police commissar announced

‘Way to my heart - London’ Pastel, (100x140), 2016 KATERYNA BORTSOVA

No migration is so abrupt and heartbreaking as those caused by war. When the only premise is to survive, destination matters little, there is no luggage nor pretensions, it’s all about keeping breathing.

This is how my grandfather arrived in Argentina after batlling in the Second World War, leaving behind a wife and two small children in a devastated Italy. He settled with other Italians in a distant country with an unknown language and after six years of hard work and silence - silence is heavier than you think - he was able to bring his family to his side and start their life from scratch.

From the declaration of war, through battle, exile, to the reunion and the beginning of a normal life, more than a decade passed. His son (my uncle) refused to call him dad, as he saw in that man a stranger of whom he had no memory. And although my grandfather won his unconditional love and never made any reference or portrayed himself a victim of anything, that devastating and absurd war, from which we learn nothing, forever changed the course of his (and my) existence.

“Why can’t we dispense once and for all with this death machine?” I asked myself in my youth without glimpsing any answer.

Today I see that I didn’t find an answer because I was looking for it in the wrong place: I was looking outwards, towards the past, towards the high military officials, the political leaders. Looking for someone responsible, a culprit, and there are many people making the same mistake that I made.

The outbreak of the latest and most resounding war made me address the issue once again, but this time

from a much more accurate and uncomfortable perspective: looking inward, and what I found was not encouraging.

Nobody wants a war. However, that word so feared and that is producing so much noise today, is strongly linked to humanity and its historical evolution. We still cling to a love for our homeland, to the symbols and customs of our little corner that do not allow us to see the underlying

danger of this love that we proclaim with pride and flags. Every time we raise the flag, build statues or print old heroes faces on bills to commemorate dates that made our nation glorious, where the political lines that shaped the map were drawn with blood, we are establishing a difference with the one next to us. This generates discord, resentments and, eventually, confrontations, in a patriotic world where no one is willing to let go of anything.

‘The fall of Europe’

We take reality as it is handed to us chewed up: we believe we own the earth, the nature, and even the stars. We grieve for the casualties of “our” soldiers, and take pride in their victories; we madly hate public enemy number one, as if a war could be the business of a single person.

A war needs the complicity of entire nations and we are actively responsible for buying the excuse that justifies it. Even today, with all our reasoning and foresight, we continue to believe the tale of the bad guy and the good guy, because it is easier and more comfortable. We don’t want to think that those leaders that we ourselves elected, in free elections, have much more in common with that public enemy that we were taught to hate, than we would like.

Hermann Hesse, critic and witness of the two greatest catastrophes of the last century put it with absolute rawness and clarity:

“And despite how incredible it may seem, the war goes on. This only happens because we are lazy, conformist and very cowardly. It is possible because deep in our hearts we somehow accept or tolerate war. Because we throw all our military resources and our souls to the wind and allow the bloody machine to keep on rolling. That very thing is what politicians do and what armies do, but we who are witnesses are no better than they are.”

Understanding that war doesn’t belong to others is not easy to assimilate; it is necessary to look and listen inward. I don’t think we can get rid of war until we’re free to look at a map without seeing those imaginary lines of political division. In other words, I don’t think we can get rid of war until we can tear down all our internal borders, since many of us feel foreign in our own land, in our own home and even in our own body.

My skin is the colour of the melting sky I see each evening through the supermarket window. It’s close to sparkling in the halogen lighting, with a sheen like the sun on water. Sometimes I pretend I’m the sun itself, glowing in its half hung state. I watch as it falls through the murky pane, as if dipping a toe into the fields before diving under. Other times I imagine us all as suns. A hundred suns in a green plastic crate. Held in a moment between night and day, held in the space between tree and basket.

So far ten hands have stroked my skin. Seven of them were children. One girl with uneven pigtails plucked me out whilst her mum wasn’t watching and kissed me. She rubbed my skin as if summoning a genie and whispered,

‘I know’ before putting me down. Perhaps she saw that I was the sun, or that I shined like the sun on water. The other children were less purposeful, and stroked with light, unbothered fingertips. They felt like the breeze that rattled the trees back home. There was a constant movement in the orchard, and now there’s light for every hour and no birds or wind or rain. Just hands. Seven children and three grannies. One of those plucked me out too, but instead of kissing me she just pinched me, tutted, and put me back.

I am one of a hundred, if I can read it correctly on the little white label. We roll and glide over each other, constantly shifting. As one of us rises another falls and we revolve around the crate like the sun around the earth. We were brought here from two neighbouring orchards in the north of Spain, where mosquitos bit my brothers and sisters and flies used us as perching spots. A lark once decided to build a nest on my branch, and I witnessed its children’s open beaks and early cries. We matured through the months together, with fluttering soft feathers shedding and

adult ones pricking their skin. Then we were plucked from the tree together. They soared into the air and I was placed in a crate on an aeroplane.

In the basket next to us on the supermarket shelf carrots lie in crowded rows. They share our skin colour but not our hue, because theirs is not soft like ours but sharp. When they’re freshly bathed the carrots glisten like the smiling people on the posters. Like them the carrots roll and fold with each touch, as if trying to get an even tan.

On our other side are sweet potatoes. That’s what they’re called, but they don’t look anything like the potatoes at the other end of the aisle. Their skin is the sallow brown of dry soil, crumbling at the edges and curving in and out. They smell of earth clad boots on dusty paths, and are a mirage of my post home. I used to wonder why they were put with us, with their skin a completely different shade, but then I saw one cut clean in half. Inside its flesh was orange, the beautiful burnt orange of an overripe apricot. Then the pattern made sense.

Most of the people who cast shadows on us as they pass have skin the colour of the lighter parts of peaches. When their children speak to strangers or they tap their pockets repeatedly at the till it turns to the shade of the darker part. Some of them have skin the colour of walnuts or polished coconut shells, though there are not as many of them. They weave around shelves and rattle trolleys from the sunrise to the sunset, and even after that.

I am looking at the shadows the early sun casts in the car park, as

‘I Heart Dublin?’one woman catches my eye. Her skin, like mine, is shining with the morning sun. Her eyes, a hazel brown like the sun and the earth combined, rush to skim the shelves and fall fixed on mine. She thrusts one hand out towards me, the other one on the strap of a cream shoulder bag. As she lifts me from my position on the top of the stack her thumb grazes across my skin. It feels soft and warm and fills me with a comforting thrill. I am whisked through the air with a bird’s eye view of the supermarket. The carrots, apples, sweetcorn, tomatoes and potatoes fly past beneath me.

Then we get to the till, and it is as black as the pavement’s tar. One strip of jet black rotating. Everything seems to rotate here, though perhaps that is just my perspective. The woman’s hand spins me against her palm, long slim fingers in quick movements. It is lights, conveyor belt, floor, shelves in one swift motion. Again and again until I am flung forward with an

‘Is that all?’

- Bebas Neue: Copyright © 2010 by Dharma Type. SIL OPEN FONT LICENSE Version 1.126 February 2007

- Another typewriter: Copyright © Johan Holm dahl https://www.dafont.com/johan-holm dahl.d314

- Acakadut: Copyright © Wep https://www.dafont.com/wep.d7858

-Blowbrush: Copyright © Petar Acanski https://www.dafont.com/petar-acans ki.d5738 https://www.instagram.com/thizizraz/