10 minute read

Offertory

By Aidan Fry Edited by Ceci Villaseñor Designed by Lauren Yung

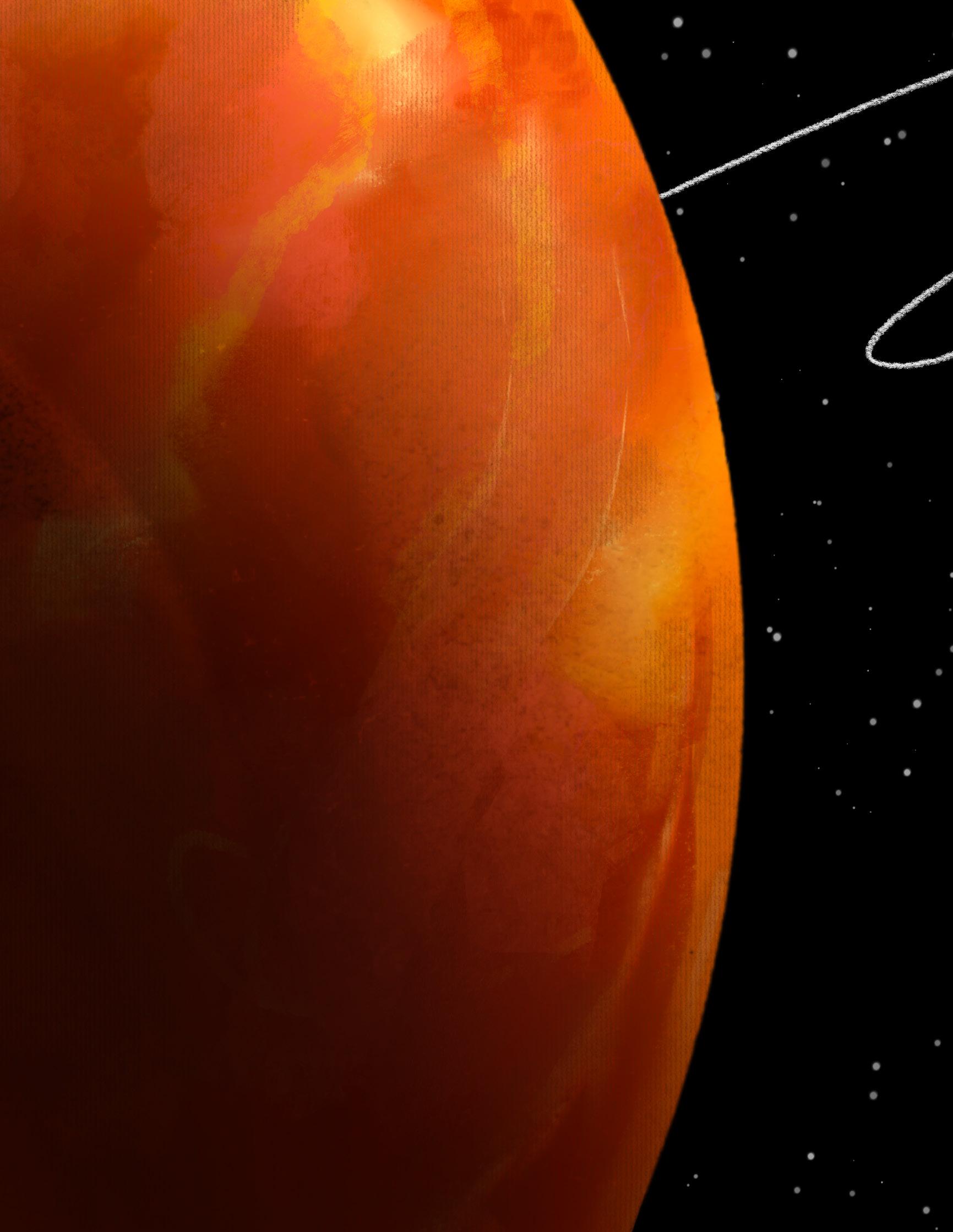

As Isaac walked out of his lola’s house and Renata limped into her bedroom, neither looked behind them, but both were trying to figure out what went wrong. Isaac’s gifts lay untouched beside the old box TV in the living room, and the food prepared by Bikbik in the kitchen had gone cold. Maybe Renata should’ve offered him some. But she figured he wouldn’t have liked it, given the “food” he claimed to eat back on Mars. “Well, not exactly food,” Isaac said. “It turns iron oxide into a sort of protein powder. Like a dietary supplement. It’s not a meal by itself, but it’s still pretty nutritious. You take those sometimes, right, lola?” “Absolutely not,” Renata replied. “I have a cook that makes real food. And not using iron oxide, mind you. Using real ingredients. Where on Earth would I find iron oxide anyways?” Isaac thought for a moment. “Rusted metal,” he said. “The brown stuff is iron oxide.” “I don’t keep rusted things,” she said. “I’m not a hoarder.” “Keep it, at least.” He tried to lean the contraption against the glass TV stand, next to the rest of his gifts. “I’ve already told you I don’t want your machines, Isaac,” she spat. “I’ll get Bikbik to throw them out if I have to. I will not have them in this house.” Isaac didn’t reply or meet her eyes. He simply dumped the last gift on the floor and went back to sitting on the armchair across from her. “By God,” Renata said. “Didn’t your mother teach you to have some respect?” Isaac wasn’t sure how to respond to that, so

Advertisement

he didn’t. But thinking back to that moment as he walked past tightly-packed houses, most decrepit and abandoned, surrounding thin streets made thinner by dozens of parked cars, he recalled his first and only concrete memory of Renata before today. He was young, though he wasn’t sure how young. His grandparents had come to America to visit, back when they were still well enough to fly in planes. His mother had briefed him before they arrived. “Isaac,” she told him, “Remember to speak up when speaking to your lola. She can’t hear very well. So speak up. OK?” He stared up at her and nodded, and when his lolo and lola arrived they were kissing his face and pinching his cheek and muttering things in a language he didn’t understand, so he didn’t feel the need to speak.

Juli picked up the slack for him. “Isaac has been interested in chess lately,” she said once they had settled in. “Why don’t you and your lola play each other?” In truth, Isaac had stopped being interested in it ever since he lost three times in a row to Caspian and refused to show up to the chess club the day after. But his mother still gave him chess books and chess boards for his birthday and for Christmas, so he nodded. Renata beat him. It wasn’t even close, in fact. All Isaac’s chess strategies and instincts had eroded into nothing, and even though he told himself he didn’t care about the game anymore, the embarrassment from that defeat still stung. Because of the loss, yes, but also because of the look on his lola’s face. How she glared at the board after he made careless move after careless move, any sense of hope for her grandson vanishing in minutes. When the game was over, neither said a word as Isaac left the guest room, not bothering to bring the board with him. That sole memory of her was why he thought his second gift would be a good idea. “It’s a puzzle game. Very popular back on Mars. You just tap the button here and you can start playing whenever. Also, very energy efficient.” “I have no need for video games,” Renata

replied.

“Technically it’s not a video game. There’s no controller, I mean. It uses a telepathic connection. So you see the image in your head, and you think of what you want to do, and that controls it. You don’t need to move around at all.” How quickly a few generations can suck out any sort of excellence, Renata thought. The fierceness that she had so carefully taught to her daughter was nowhere to be found. Was this all that wanting the best for her child got her? Out of the living room now, she had managed to climb into her bed, but her room’s flatscreen was refusing to turn on. She squeezed on the power button with all her might, thrusting the remote towards the TV with each press, but to no avail. She huffed and admitted defeat, laying back on her pillow. She’d probably forget to ask Bikbik to replace the batteries later. Yes, luxury was both a blessing and a curse. Renata wondered if her hard work had been in vain. Her mind wandered back to her days in the University

of the Philippines at Quezon City. This was back when the entrance fee was so low that getting in said something about one’s intelligence instead of one’s wealth. Slum boys walked side by side with sons of politicians as scholars of the nation, and everyone wore flip flops as a reply to the designer clothes of the elite universities next door. During the many sitdown protests against President Marcos, she recalled a line from an American song being played over the speakers: “We don’t need no education…” Renata saw her first American at an awards ceremony for Garcia Hibionada, her lolo and Isaac’s great-great-grandfather. He had been the mayor of a now-dead town when he was killed during World War II. The Americans told everyone that he resisted the occupation by the Japanese and would be remembered as a brave hero, but in hindsight, Renata surmised that the real reason for the medal of honor was because he died and the Americans felt sorry for him and his family. In any case, the medallion wasn’t made of anything valuable, so the family decided not to sell it. But they still ended up losing it thirty years later, when Juli’s brother, Manang Rodrigo, placed it around the neck of a stray dog and tried to take a picture but ended up scaring it away with the flash of the camera. “It recharges when you put it out in the sun, see?” Isaac pointed to the grey panel on the device’s back. “Just don’t leave it out for too long.” “I don’t like to stay out in the sun for too long,” Renata said. “It’s not good for my skin.” Isaac suddenly became aware of how much his chance of skin cancer was increasing with each step he took under the sun. He pressed a button on the left arm of his spacesuit, and a clear, UV-resistant visor swivelled to cover his head. He was nearing his ship now, parked in the middle of an open field. It was the only suitable landing spot near Renata’s house; the rest of the surrounding area was covered in cramped homes and dense forest. Renata thought that she had failed to impart her fierceness into Juliana, which resulted in the sorry state that Isaac was in today. In reality, the opposite was true. Stamping through tall grass, Isaac recalled shouting match after shouting match with his mother after school, some over forgotten homework assignments and others over skipped classes, each one ending with Isaac whimpering to hold back tears and Juliana pulling him close and apologizing over and over, but in her head lamenting that her worst fears had come true, that she was the mother of a son that would never amount himself to anything. For Isaac, each fight solidified the thought that it was better to be loved by no one than to be loved and be held responsible for the inevitable disappointment of his loved ones’ expectations. And so, as commercial trips to Mars began to fly out, he boarded the first spaceship he could and never returned. That was, until he received news from his parents that his lolo had died in his sleep. Isaac had so little memory of his grandfather that the death didn’t shock him at all, but thinking about it more, his lack of shock over the death eventually made him very shocked indeed. Determined to not let that one embarrassing chess match be the only memory he had of his lola, he took a year after the death to build up the courage to return, then another a year to save up enough money to buy a spaceship, then another year to learn to drive the spaceship before finally making the trip to Earth. And as Isaac finally reached his spaceship in the middle of the field and climbed up the ladder to the entrance hatch, he surmised that the critical mistake may have been when they were discussing languages. Maybe he shouldn’t have given his first gift at all. “At least Juliana had the good sense to teach you Ilongo,” Renata noted. “Ha ha. Um, no,” Isaac said. “I’m not actually speaking Ilongo.” He pointed to the small white box attached to the shoulder of his spacesuit, and that was when she realized that the words he spoke were not coming from his mouth. They instead were emitted from a speaker that was filtering his voice through and translating it. Renata looked at the machine, then back at her grandson, then back at it. “And I actually have a second one of these to give to you, as a gift. I think you might find it useful.” Renata found her words again. “Oh. Yes, a gift. I see. Well, that’s very generous of you, but you see, I don’t need a translator. So I’m afraid you’ll have to keep it.” “Well, that’s alright,” Isaac said, putting it down beside the TV. “I have other things.” When Renata realized that her son was using a translator, the first thing that came into her mind was not disappointment, but a memory of her lola Isabelle Hibionada, Isaac’s great-great-grandmother.

Along with Garcia, she had moved from Spain to the Philippines to follow her merchant husband. But she was stubborn. Even after she had birthed children and sent them to public school, she refused to speak the dirty Ilongo dialect, instead only speaking Spanish and forcing all those in her presence to do the same. This was why Renata’s mother, Rose, grew up speaking fluent Spanish, and why when Rose had her first crippling stroke, the only trace of language left in her for two months after was a babbling, murky mess that her children could only understand the proper nouns of. After two months of her mind’s forced isolation inside her body, Rose’s first order of business after recovery was establishing immediate Spanish lessons for the children. None of them were able to do the same for their own children. Instead, what Renata did for her little Juliana was instill a sense of purpose. The country, as she saw it, was dying a slow death under years of dictators and complacent populations. She saw no hope in staying. So she let Juliana grow up to be suffocated by the walls of their home and be drawn to the thrill of adventure so that when it came time for her to leave the nest, she would go far, far away. To a place that would give her the future she could not have here. And it worked. For when Juliana reached a certain age, after a few years of accounting during an economic slump had successfully worn her down, she left the Philippines to work as a flight attendant. Renata didn’t see her leave, but she imagined her flying away on a Dreamliner, and saw in her mind that she wasn’t looking back at her, and smiled and thought that was the end of it. That she wouldn’t be returning. But then what was this that she saw, standing at the foot of her door as she hobbled into the living room? A little boy wearing a spacesuit too big for him. His face was just barely visible at the top, like a monkey peeking out from behind a tree. The eyes of Renata’s daughter had come back. “Hi, lola,” he said. “It’s me, Isaac. Your grandson.”