STATISTICAL REPORT 2015

The Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE

Associate Professor Marion Saville, VCS Executive Director

Associate Professor Julia Brotherton, Medical Director, Registries and Research

Genevieve Chappell, Director, Registry Operations

Bianca Barbaro, Geographical Consultant

Floriana La Rocca, Follow-up Manager

Louise Ang, Health Information Manager

Karen Peasley, Health Information Manager

Karen Winch, Health Information Manager

PRODUCED BY

Elizabeth Aquino Perez, Health Information Manager

Copyright Notice © 2017 Victorian Cytology Service Limited (ACN 609 597 408)

Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry PO Box 161 Carlton South Victoria 3053 03 9250 0399 registry@vccr.org www.vccr.org

Published December 2017 ISSN 2202-4417

These materials are subject to copyright and are protected by the Copyright Laws of Australia.

All rights are reserved.

Any copying or distribution of these materials without the written permission of the copyright owner is not authorised.

LIST OF TABLES

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Table

Figure

Figure

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

THE NATIONAL CERVICAL SCREENING PROGRAM IS ENTERING AN EXCITING TIME OF SIGNIFICANT POLICY CHANGE. IN 2014, THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCED THAT THE PRESENT CERVICAL SCREENING PROGRAM WILL CHANGE TO A PRIMARY HPV SCREENING TEST AT A FIVE-YEAR SCREENING INTERVAL FOR WOMEN BETWEEN THE AGES OF 25 AND 74 YEARS.

This strategy is known as Renewal and will commence late 2017. The Renewal will ensure that Australian women have access to the best and safest screening program based on current evidence. Until the changeover, the screening policy recommendation remains as two yearly Pap tests for women aged 18 to 69 years of age.

The VCCR is working closely with VCS Pathology to support the Compass trial, which is a randomised controlled trial that is comparing two and a half yearly cytology based cervical screening with five-yearly primary HPV DNA testing. The Pilot trial commenced in October 2013 and the Main trial commenced in January 2015. The trial is a sentinel experience of the Renewed program and offers eligible Victorian women and their healthcare practitioners an opportunity to be part of the new screening program at an early stage. The trial is being led by researchers from the Victorian Cytology Service (VCS) Ltd. and the Cancer Council New South Wales. The VCCR is providing follow-up and reminders to women in the Compass trial which ensures that the Registry is fully prepared for the forthcoming changes and experienced in managing women following the new screening pathway.

One of the key activities of the VCCR is to improve participation of Victorian women in the cervical screening program by sending reminder letters and conducting research into under-screening. In 2015, with ongoing assistance from the Victorian Government, the sending of second reminder letters to Victorian women regarding Pap tests continued to be an important initiative for the National Cervical Screening Program.

During the screening period of 2014-2015, the estimated two year participation rate for women aged 20 to 69 years was 57.9%, which is a slight decline from the previous two year period 2013-2014 of 59.2%. The only age group which experienced an increase in participation in 2014-2015 was women 60 to 69 years who had a participation rate of 62.8%. The highest participation rate was amongst women 50 to 59 years, of whom 66.5% had a Pap test in the two year period 2014-2015.

There has been an ongoing decline in two year participation among younger women with participation in women aged 25 to 29 years falling more than ten percentage points over the last decade from 60.2% in 2004-2005 to 48.9% in 2014-2015. Whilst this is a continuation from an existing underlying trend, it may now reflect HPV vaccinated women becoming complacent about the need for screening.1 It will be important to emphasise to young women that participation in screening, whether or not they received the HPV vaccine, is important when they are invited to start screening at age 25 years in the Renewed program.

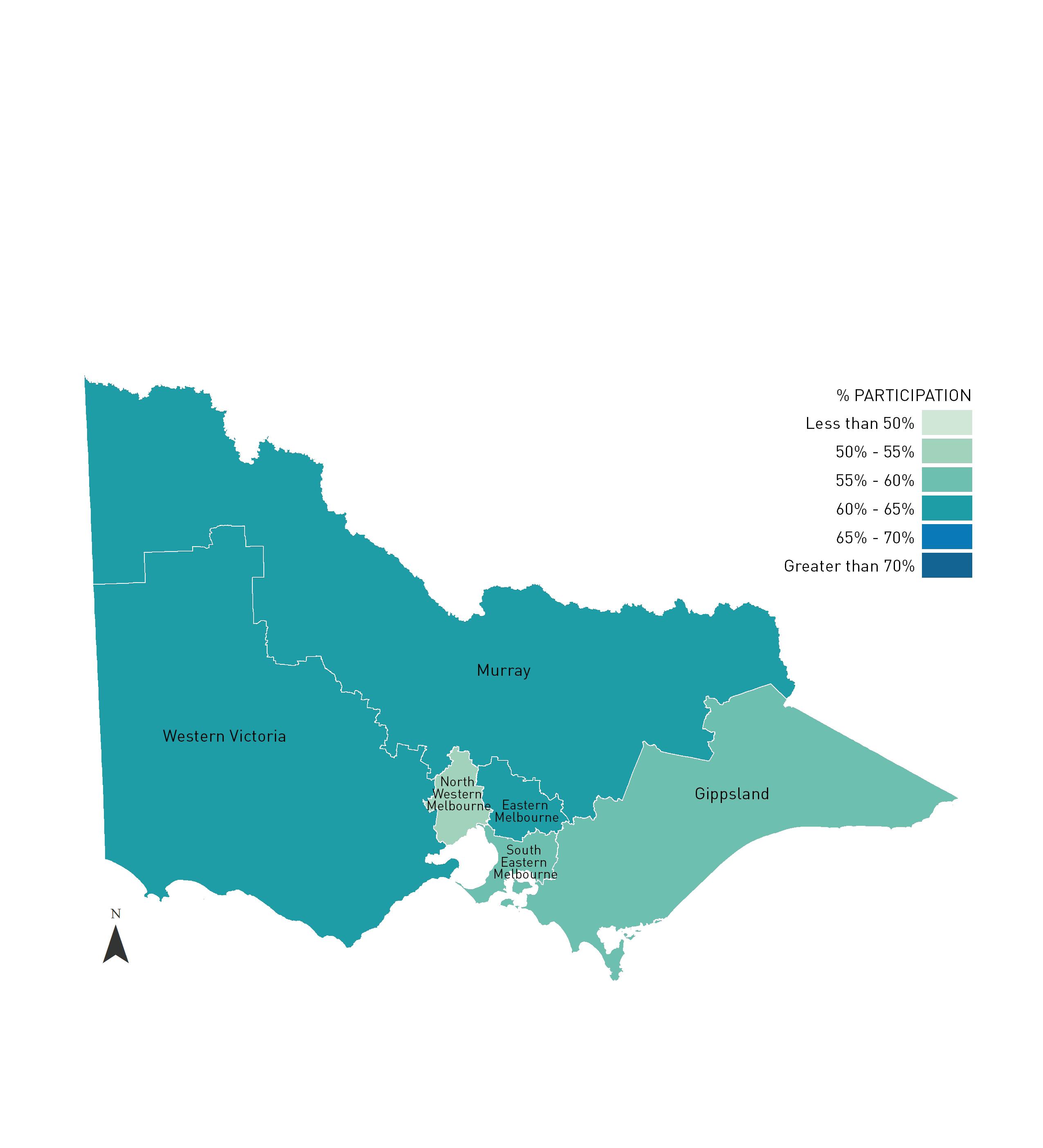

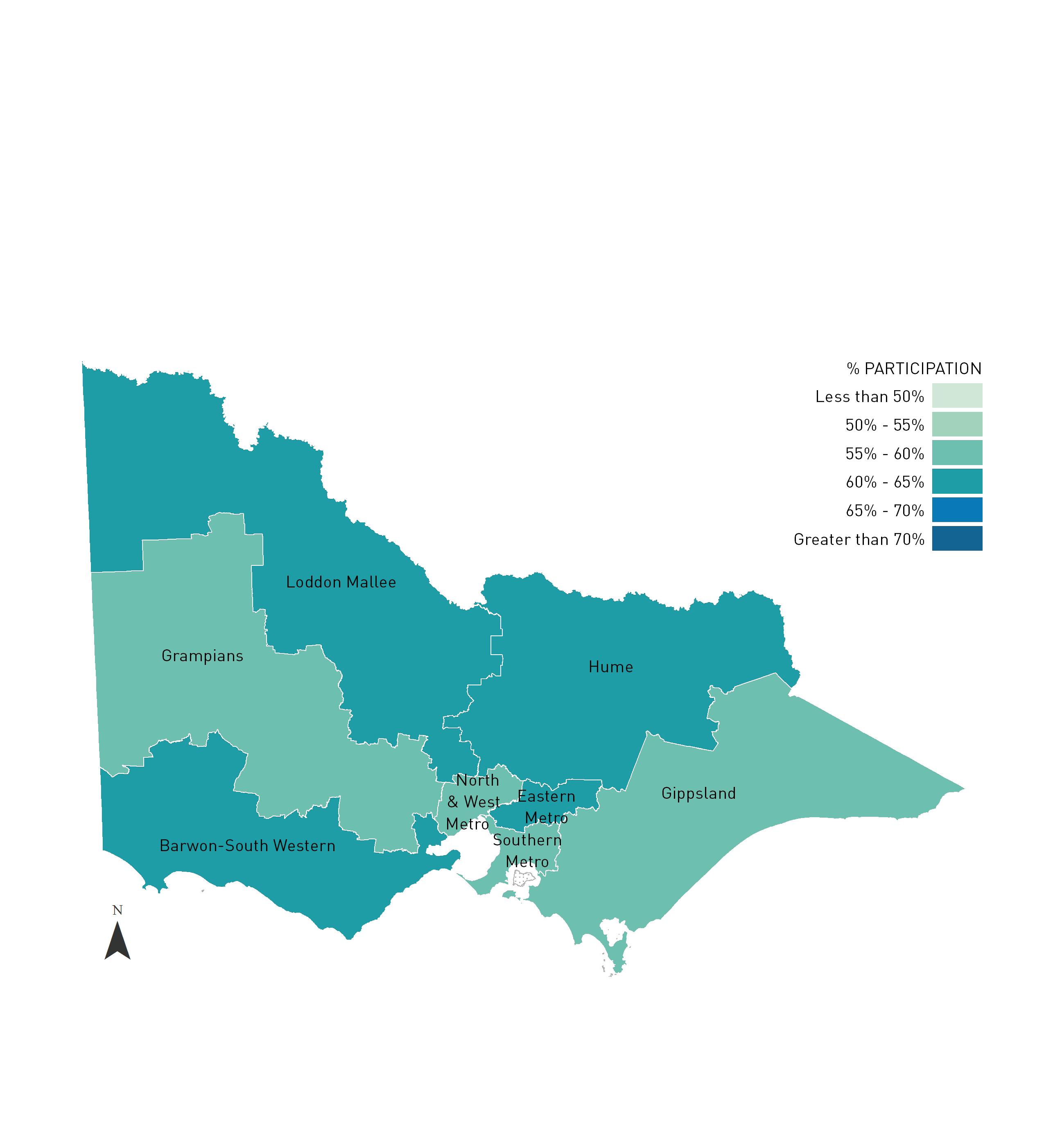

Substantial variation exists in screening rates between different areas of Victoria, as represented by Primary Health Networks, with the two year screening rates for 2014-2015 ranging from 54.7% to 61.6% across the six networks. The screening rate for the eight Health regions ranged from 55.5% to 62.9%, while the estimated two year participation rate for the 79 Local Government Areas ranged from 42.0% to 78.2%.

As part of the follow-up and reminder program, the VCCR registered a total of 602,505 Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) 2 in 2015, representing 575,574 women, and sent 503,013 follow-up and reminder letters to women and practitioners. In 2015 there were 19,480 HPV DNA tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) completed as part of the Compass trial, representing 19,453 women and inclusion of these data in the report is described further in Sections 1.6 and 2.1.

More than 7,000 abnormal Pap tests were followed up by the VCCR in 2015. Of these, 1,627 questionnaires were sent to the practitioners for further information on women with high grade abnormalities. Along with following up women with abnormal results, 478,776 reminder letters were sent to women in 2015 across all Pap test reporting categories. Of the first reminders sent to women after a negative Pap test, 31.3% of women had a subsequent Pap test within three months. Almost 142,000 second reminder letters were sent to women and, of the 134,575 sent after a negative Pap test, 17.7% had a subsequent Pap test within three months of the reminder.

Of Pap tests recorded by the VCCR during the period of this report, a definite high-grade squamous cell abnormality was present in 0.7% of tests and an endocervical abnormality was identified in fewer than 0.1% of tests. Of the 3,683 high-grade cytology tests which had histology reported within six months, 2,735 were subsequently confirmed with high-grade histology on biopsy. This represents a positive predictive value of 74.3% and reflects the high quality of laboratory reporting in Victoria. Rates of high-grade histology diagnosis in screening women continue to decline in the cohorts who received the HPV vaccine, with ongoing declines in women aged <20, 20 to 24 and 25 to 29 years.

Over the last decade there has been a gradual increase in the proportion of CSTs collected by nurses, with over 5% of all tests collected by nurses over the last five years. In 2015 tests collected by nurses represented 5.6% of all CSTs collected in Victoria, highlighting the significant role nurses have in the National Cervical Screening Program.

VCCR continues to work closely with program partners to identify groups in our community that are less likely to screen. Collecting information from women attending screening about their identification as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, their Country of Birth and the Language Spoken at Home is critical for understanding who participates in cervical screening. The overall percentage of women screened in 2015 who had their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander status recorded by the VCCR was 26.6%, for Country of Birth 22.1% and Language Spoken at Home 22.9%.

According to recent data (2015) from the Victorian Cancer Registry, incidence and mortality from cervical cancer in Victoria remain at very low levels, at 4.5 and 0.8 per 100,000 women respectively. This is a tremendous achievement and reflects the success of the National Cervical Screening Program in Victoria, which is underpinned by the VCCR. Despite this success, further efforts are necessary to improve participation amongst under-screened women as 81% of Victorian women who were diagnosed with invasive squamous cervical cancer in 2014 had never had a Pap test, or were lapsed screeners, prior to their cancer diagnosis.

1 Budd

. Med J Aust.2014;201:279-282.

2 Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) refers to Pap tests collected as part of the National Cervical Screening Program, as well as both Pap tests and HPV DNA tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) collected as part of the Compass trial.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND

The Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) is one of eight such registries operating throughout Australia. Victoria was the first State to establish such a register and commenced operation in late 1989 after amendments to the Cancer Act 1958.

The Pap test Registries, as they are commonly known, were introduced progressively across Australia throughout the 1990s. The Registries are an essential component of the National Cervical Screening Program and provide the infrastructure for organised cervical screening in each State and Territory.

The VCCR is a voluntary “opt-off” confidential register of Victorian women’s Pap test results. Laboratories provide the VCCR with data on all Pap tests taken in Victoria, unless a woman chooses not to participate.

The VCCR works closely with the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and other Program Partners including PapScreen Victoria, which is responsible for the communications and recruitment program aimed at maintaining the high rates of participation of Victorian women in the National Cervical Screening Program.

1.2 FUNCTIONS OF THE VCCR

The VCCR facilitates regular participation of women in the National Cervical Screening Program by sending reminder letters to women for Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) and by acting as a safety net for the follow-up of women with abnormal CSTs.

From October 2015, the new Victorian Improving Cancer Outcomes Act came into effect which underpins the operations of the Registry and the reporting of cervical screening and related tests to the Registry.

The core functions of the VCCR, are to:

• follow-up positive results from cancer tests

• send reminder notices to women who are due for CSTs

• compile and publish statistics

• provide known screening histories to laboratories reporting CSTs

• provide quantitative data to laboratories to assist with their quality assurance programs

• provide aggregate data to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) so that the National Cervical Screening Program can be judged against an agreed set of performance indicators

• where appropriate, provide access to the Register to persons studying cancer.

1.3 NATIONAL POLICY: THE NHMRC GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF ASYMPTOMATIC WOMEN WITH SCREEN DETECTED ABNORMALITIES

On 1 July 2006, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines for the Management of Asymptomatic Women with Screen Detected Abnormalities 3 were implemented around Australia. The main changes to the previous guidelines were:

• the change of terminology for cytology reports to the Australian Modified Bethesda System 2004

• to repeat Pap tests for most women with low-grade squamous abnormalities

• to not treat biopsy proven low-grade or HPV lesions

• to refer all women with atypical glandular cells for colposcopy

• to refer all women with a possible high-grade lesion for colposcopy

• to use HPV tests and cytology as a test of cure for women treated for CINII and CINIII.

The VCCR participates in the National Safety Monitoring of the NHMRC guidelines. 4

3 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2005. Screening to prevent cervical cancer: guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities, Canberra: NHMRC.

4 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2013. Report on monitoring activities of the National Cervical Screening Program Safety Monitoring Committee. Cancer series 80. Cat. no. CAN 77. Canberra: AIHW.

1.4 RENEWAL OF THE NATIONAL CERVICAL SCREENING PROGRAM

While the National Cervical Screening Program has been successful since its introduction in 1991, the science relating to cancer continues to change. New technology to assist with the detection of cervical cancer has been developed, new evidence has emerged about the optimal screening age range and interval, and the HPV vaccine has become available.

During 2011, the Standing Committee on Screening of the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council commenced the review of the policy and operation of the National Cervical Screening Program. Input and feedback was sought from expert committees including the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) and reference groups for the best evidence on screening tests and pathways, the screening interval, age range and commencement into the program for both HPV vaccinated and non-vaccinated women.5 A cost-effective screening pathway and program model was then proposed and endorsed to ensure women have access to a cervical screening program that is safe, effective and efficient, and based on current evidence. The planned commencement date of the renewed program is 1 December 2017.

In summary the recommendations for Renewal include:

• a new Cervical Screening Test – a HPV DNA test – to become the primary screening test, followed by a triage Pap test if necessary

• HPV testing to be done every five years for HPV vaccinated and unvaccinated women aged 25 to 74 years

• women with symptoms can have a cervical test at any age

• invitations for women to attend for screening, recall and follow-up

• the option of a self-collect HPV sample for under-screened and never screened women. 5

1.5 THE NATIONAL HPV VACCINATION PROGRAM

The National HPV Vaccination Program commenced in April 2007 and is already having a substantial impact on the prevalence of HPV infection and cervical lesions in vaccinated cohorts.6 Between 2007 and 2009, 12 to 26 year old females were offered the quadrivalent HPV vaccination (Gardasil) in a national catch-up program provided through schools, general practice and other community providers. Since 2009 the program has offered routine vaccination through schools for 12 to 13 year old girls. From 2013, vaccination of boys at 12 to 13 years has also been offered, with a two year catch-up program for 14 to 15 year old boys finishing in 2014.

The Pap test Registries around Australia play an important role in monitoring the impact of the vaccination program on participation rates in cervical screening and on cervical abnormalities and cancer in the long term. The importance of continuing regular CSTs for vaccinated women is emphasised as part of the National HPV Vaccination Program.

A National HPV Vaccination Program Register (the HPV Register)7 was established to support, monitor and evaluate the National HPV Vaccination Program. The Victorian Cytology Service (VCS) Ltd., which has operated the VCCR for over 25 years, was engaged by the Department of Health and Ageing in February of 2008 to establish and manage the National HPV Program Register.

The HPV Register receives data from all States and Territories and from all types of vaccination providers including local councils (who in some States deliver the school vaccination program), general practitioners, nurses and other immunisation providers around Australia. The Register records basic demographic information and information about HPV vaccine doses administered in Australia.

The HPV Register supports the program by sending statements on vaccination status to eligible vaccine recipients and their providers, and by providing reports and de-identified data to approved providers and researchers.

Linkage of data held by the HPV Register with information held by cervical screening and cancer registries will be a critical component of monitoring and evaluating the impact of vaccination. Through de-identified data linkage undertaken between the HPV Register and the VCCR through to the end of 2011, we demonstrated a 48% reduction in the rates of the most serious cervical pre-cancers for women who had been completely vaccinated in the school-program, compared with unvaccinated women. 8 These data indicate that the downward trend observed among young women within VCCR and national screening data can be ascribed to HPV vaccination.

5 Australian Government, Department of Health, National Cervical Screening Program Renewal website viewed 1 December 2016. http://cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/ Content/cervical-screening-1

6 Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JML, Kaldor JM, Skinner SR, Cummins E, Liu B, Bateson D, McNamee K, Garefalakis M, Garland SM. Fall in Human Papillomavirus Prevalence Following a National Vaccination Program J Infect Dis. 2012; 206 (11): 164551.

7 The National HPV Vaccination Program Register website. http://www.hpvregister.org.au , viewed 1 December 2016.

8 Gertig DM, Brotherton JML, Budd AC, Drennan K, Chappell G, Saville AM. Impact of a population-based HPV vaccination program on cervical abnormalities: a data linkage study. BMC Medicine 2013; 11:227.

1.6 DATA INCLUDED IN THIS REPORT

This statistical report provides timely information about cervical screening in Victoria during 2015. In most cases the methodology and terminology used in VCCR reports are consistent with that published by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) as part of reporting indicators for the National Cervical Screening Program.9

Cervical Screening Tests

While the VCCR records Pap test data for Victorian women, it also captures data from the Compass trial. The Compass trial is a clinical trial comparing two and a half-yearly Pap test screening with five-yearly HPV DNA screening.10 The Compass Pilot study commenced recruitment in October of 2013 and the Main trial commenced recruitment in January of 2015.

In line with Cervical Screening Renewal, HPV tests are now considered Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) along with Pap test cytology. Where relevant, both the Pap tests and HPV tests completed as part of the Compass trial have been incorporated into the statistics in this report and noted where applicable. Generally, Compass HPV tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) are included in the participation statistics in Section 2 of this report but not in the other Sections which relate to cytology or histology.

Participation rates

This report includes information on participation rates of CSTs (i.e. conventional Pap tests and Pap tests/HPV tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) as part of the Compass trial) for women aged 20 to 69 years in ten year age groups and additionally by five year age groups for the 20 to 29 year old group. Population data have been adjusted to exclude women who have had a hysterectomy, using modeling carried out by the AIHW based on the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). The two year participation rates are also presented by Primary Health Networks (PHN), Health region and Local Government Area (LGA).

The number and proportion of CSTs collected by nurses are presented in this report, by year and Health region. Further information regarding CSTs collected by nurses is available in the report ‘Evaluation of Cervical Screening Tests collected by Nurses in Victoria during 2015’, available on the VCCR website at http://www.vccr.org/data-research/statistical-reports/annualnurse-reports

The Participation in Screening section also includes some limited information on the identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and the collection of indicators of cultural diversity, such as Country of Birth and Language Spoken at Home.

Information on the proportion of women who rescreen early is also featured.

Cytology coding

Information provided on the cytology report of Pap tests is pre-coded by the pathology laboratory according to the Cytology Coding Schedule. Appendix 1 outlines the Australiawide cytology codes that have been used since 1 July 2006 to correspond with the implementation of the NHMRC guidelines.11 The Cytology Coding Schedule allows a Pap test report to be summarised to a six digit numeric code covering the type of test, site of test, squamous cell result, endocervical cell result, other non-cervical cell result, and the recommendation made by the laboratory in regard to further testing.

Data are presented in this report on the proportion of Pap tests classified according to results, including unsatisfactory, negative, squamous abnormality and endocervical abnormality. The percentage of Pap tests collected during 2015 without an endocervical component is also presented.

Histology reports

The 2015 histology results in this report are as notified to the VCCR by July 2016. The vast majority of histology reports were notified by this time. The VCCR also receives a proportion of colposcopy only results, most typically when a histology report is not available. Data included in this report excludes results reported from a colposcopy report alone (i.e. no laboratory report). This report also provides information on the correlation of cytology reports received by the VCCR during 2014 and subsequent histology reports received up to six months later.

In 2013, the VCCR implemented a program for colposcopists to submit additional information relating to colposcopies performed in Victoria. These data assist with the follow-up of abnormalities and the monitoring of colposcopy quality. Summary reports are being provided to colposcopists to assist them in monitoring and improving their practice.

Follow-up protocol

The VCCR Reminder and Follow-up protocol is based on the NHMRC Guidelines for the Management of Asymptomatic Women with Screen Detected Abnormalities.12 The Reminder and Followup Protocol used by the VCCR in 2015 is shown in Appendix 2.

Reminder letters are not sent to women whose VCCR records indicate a past history of hysterectomy or of cervical or uterine malignancy, or to women who are over 70 years of age and whose last Pap test was normal.

Cervical cancer incidence and mortality

Information on cervical cancer incidence and mortality is provided in this report courtesy of the Victorian Cancer Registry at the Victorian Cancer Council. Also included is a section examining the screening history of Victorian women diagnosed with invasive and micro-invasive cervical cancer during 2014.

9 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. Cervical screening in Australia 2014–2015. Cancer series no.105. Cat. no. CAN 104. Canberra: AIHW. 10 Compass trial website. http://www.compasstrial.org.au/, viewed 1 December 2016.December 2016.

11 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2005. Screening to prevent cervical cancer: guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities, Canberra: NHMRC. 12 Ibid.

2. PARTICIPATION IN SCREENING

2.1 NUMBER OF CERVICAL SCREENING TESTS AND WOMEN SCREENED

Table 2.1 shows data on the number of Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) registered and the number of women screened for each year of the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry’s (VCCR) operation. During 2015, a total of 602,505 tests were registered from 575,574 women. This is an increase of 7,365 tests and 7,902 women screened from the previous year.

As described in Section 1.6, CSTs include HPV tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) and Pap tests as part of the Compass trial, as well as Pap tests as part of the National Cervical Screening Program. Table 2.1 includes 3,706 Compass HPV DNA tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) from 3,577 women for 2014, and 19,480 Compass HPV DNA tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) from 19,453 women for 2015.

In interpreting the information in Table 2.1, it is important to consider that while it is recommended that women screen every two years, a small proportion of women in Victoria are screened on an annual basis. Additionally, correct attribution of CSTs to the same woman over time is not always possible, sometimes resulting in a possible overestimation of women recorded on the VCCR. However, over the last 10 years, 95% of women with a Pap test record on the VCCR have had a Medicare number recorded. This has resulted in more complete record-linkage of different episodes of care for women.

The VCCR is a voluntary “opt-off” registry; however, the proportion of women who are part of the screening program but decide to opt-off the VCCR is estimated to be fewer than 1%. Correlating VCS laboratory records with those held by the VCCR shows a ten year (2006-2015) opt-off rate of 0.33%. Where a woman objects to her Pap test being registered, the VCCR holds no information about that test.

TABLE 2.1 Number of Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) registered and number of women screened in Victoria, 1990-2015.

Notes

• The number of CSTs registered and women screened on the Registry as of 1 December 2016. CSTs include Pap tests and both Pap tests and HPV DNA tests (without Liquid Based Cytology) completed as part of the Compass trial (refer to Section 1.6).

2.2 PARTICIPATION BY AGE GROUP

Method of calculating participation

The participation of women estimated to be part of the Victorian Cervical Screening Program by age group is expressed as a percentage. This is determined by dividing the number of women screened by the number of women in the general population who are eligible for screening.

The number of women screened (numerator) is determined from the VCCR. It is the number of women resident in Victoria who had at least one CST in the time period of interest and have not had a hysterectomy according to information held by the VCCR. It includes women who have participated in the Compass trial.

The eligible population (denominator) is the number of women in the general population averaged for the time period of interest, and adjusted to include only women with an intact cervix. To determine this, the Victorian female Estimated Resident Population (ERP)13 calculated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is averaged over two years and then adjusted to exclude the proportion of women estimated to have had a hysterectomy using the known percentage of women who have not had a hysterectomy. Whilst VCCR participation statistics produced prior to 2011 used hysterectomy fraction estimates from the National Health Survey,14 these data are no longer collected by the ABS. In VCCR Statistical reports from 2011 onwards, population data for the latest screening periods have been adjusted with hysterectomy estimates from analysis conducted by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) using data from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD).15 This is consistent with the national approach.

It is important to appreciate that changes in the methods used to calculate participation impact upon the actual participation estimates. Hence comparisons in participation over time should be made with caution.

Limitations of participation statistics

As previously discussed, one limitation to these participation statistics is the imperfect record-linkage between multiple CSTs from the same woman that could result in an overestimate of the number of women screened. This needs to be considered carefully when looking at participation over a longer time period (such as for three or five years) as this overestimate of women screened will be relatively amplified thereby producing an overestimate in participation.

In addition, where site of specimen information is not reported to the Registry when a Pap test is taken from a woman without a cervix, the woman will be incorrectly included in the numerator.

Participation in cervical screening by age group

Table 2.2 shows the estimated cervical screening rates for Victorian women by age group for one, two, three and five year periods, with data adjusted to exclude women who have had a hysterectomy.

TABLE 2.2 Estimated cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria 2011-2015 by age group over one year, two year, three year and five year periods.

13 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 3101.0 – Australian Demographic Statistics, Dec 2016 (release date 27/06/2017).

14 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 4364.0 – National Health Survey: Summary of Results, 2004-2005 (release date 27/2/2006).

15 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. Cervical screening in Australia 2014-2015. Cancer series no. 105. Cat. no. CAN 104. Canberra: AIHW.

Notes

• The eligible female population is adjusted to exclude the estimated proportion of women who have had a hysterectomy using hysterectomy fractions derived from the NHMD.

• The table provides the percentage of women screened as a proportion of the eligible female population (crude rate). The numerator only includes women who have not had a hysterectomy according to information held by the VCCR.

• Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Periods covered apply to calendar years.

The one year screening rate for women aged 20 to 69 years during 2015 was slightly lower than the previous period of 2014 (31.6%).16

The two year screening rate (for the calendar years of 20142015) for women aged 20 to 69 years is estimated at 57.9%, which is a slight decrease from 59.2% for the previous reporting period (2013-2014).17 The increase in the eligible population was slightly higher than the increase in the number of women screened which has led to a small decline in participation. The 20 to 29 year old cohort reported the lowest two year participation rate at 44.2% (a decrease from 46.0% reported for the previous period) while the 50 to 59 year old cohort had the highest participation at 66.5% (for 2014-2015).

Over the three year period from 2013-2015, the participation rate of Victorian women aged 20 to 69 years is estimated at 71.1%, which is a slight decrease from the previous period of 2012-2014 (72.6%). Table 2.2 also highlights the five year estimated participation rate of 83.4% for 2011-2015, which is a slight decrease from the previous period (83.9%).18 Five year participation rates for women aged between 20 and 49 years decreased slightly from the previous period, whereas participation for women aged over 50 years increased.

16 Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR), Statistical Report 2014 Available from: http://www.vccr.org/data-research/statistical-reports 17 Ibid. 18 Ibid.

Estimated two year participation over time

As seen in Table 2.2.1 and Figure 2.2.1, there was a small decline in participation over time for each age group between 2000-2001 and 2010-2011. An increase in the number of women being screened occurred in most age groups in the 2011-2012 and 2012-2013 periods. It is likely that the introduction of a second reminder letter19 in 2013 was responsible for the improved participation in women aged 40 and over during that period. In contrast, except for the age group 60 to 69 years old, the 2014-2015 period has seen a decline in participation, particularly in the younger cohorts of women aged less than 50 years (refer to Figure 2.2.1).

TABLE 2.2.1 Estimated two year cervical screening rates by age group, 2000-2001 to 2014-2015.

Notes

• * 2000-2001 to 2004-2005 population data has been adjusted using the 2001 National Health Survey hysterectomy fractions estimates.

† 2005-2006 to 2009-2010 population data has been adjusted using the 2004-05 National Health Survey hysterectomy fractions estimates.

‡ 2010-2011 to 2014-2015 population data has been adjusted using the NHMD fractions estimates (courtesy of the AIHW).

• Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Periods covered apply to calendar years.

FIGURE 2.2.1 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by age group, 2000-2001 to 2014-2015.

Notes

• The graph provides the percentage of women screened as a proportion of the eligible female population (crude rate). Women screened only includes women who have not had a hysterectomy according to information held by the VCCR. The eligible female population is adjusted to exclude the estimated proportion of women who have had a hysterectomy using hysterectomy fractions as indicated by the symbols *, † and ‡; which are outlined in the notes under Table 2.2.1.

• Women screened by the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Periods covered apply to calendar years.

19 The second reminder letter provides a further prompt for a woman to attend for a Pap test if the first reminder following a negative result does not result in a Pap test being received by the Register within 36 months.

Figure 2.2.2 illustrates the consistent decline in participation over time in the 20 to 24 and 25 to 29 year age groups. This ongoing decline in participation among younger women may have been exacerbated by the availability of HPV vaccination, which provides primary prevention against those cervical cancers caused by HPV types covered by the vaccine, and which was offered to young women aged up to 26 years in Australia from 2007. This is a cause for concern as younger vaccinated women may be becoming complacent about the need for screening, as suggested by their lower participation than unvaccinated women in an analysis linking VCCR data with the National HPV Vaccination Program Register (NHVPR). 20 Continued education of vaccinated women about screening is necessary to maximise protection against cervical cancer.

FIGURE 2.2.2 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women aged 20 to 24 years and 25 to 29 years, 2003-2004 to 2014-2015.

HPV Vaccination Program

to 24 years

to 29 years

Budd AC, Brotherton JML, Gertig DM, Chau T, Drennan K,

M. Cervical screening rates for women vaccinated against human papillomavirus Med J Aust.2014;201:279-282.

2.3 PARTICIPATION BY AREA

Method of calculating participation

The participation rate for age eligible women (i.e. aged 20 to 69 years) in cervical screening for Primary Health Networks (PHNs), Health regions and Local Government Areas (LGAs) is expressed as a percentage.

The numerator is the number of women by postcode who had at least one Cervical Screening Test (CST) in the time period and who have not had a hysterectomy according to the information held by the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR).

The denominator is the estimated number of women in each Postal Area21 adjusted to exclude the proportion of women estimated to have had a hysterectomy using the hysterectomy fractions from the National Hospital Morbidity Database (NHMD). 22

To calculate the estimated participation rates for areas, data by Australia Post postcodes and Postal Areas were mapped to LGAs and PHNs using conversion files sourced from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and the Commonwealth Department of Health respectively.

The mapping of the 2014-2015 participation data for LGAs is based on concordances 23 consistent with the ABS Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS). 24 Participation data by Health regions are calculated as an aggregate of LGAs, while PHNs were created based on the Postal Areas to PHN concordance file. 25

Limitations of participation statistics by area Small-area data (e.g. Health regions, LGAs and PHNs) are subject to greater measurement error than the data in Sections 2.1 and 2.2. The main source of inaccuracy in the following tables are likely to be due to:

• an overestimate of women screened due to conservative file matching by the VCCR

• applying the national hysterectomy fractions to the relatively small female population resident in the Postal Areas

• the proportion of Victorian Pap tests reported by laboratories outside of Victoria which are not reported to the VCCR (this mainly affects areas located on the Victoria/ New South Wales and Victoria/South Australia borders)

• the differences between the Australia Post postcodes used to report screening numbers according to address data given by the woman (used as the numerator in calculating participation) and the ABS Postal Areas for which population statistics are available (used as the denominator). It is important to note that although there are commonalities between postcodes and Postal Areas, they are not exact matches and their boundaries can differ The underlying reason for the differences in these boundaries is that the ABS Postal Areas were created specifically for Census purposes and disseminating statistics, while postcodes are designed to distribute mail.

When comparing participation rate estimates by geographical area, it should also be noted that these are crude rates, i.e. they have not been age-adjusted. Therefore, areas with older populations will have apparently higher screening rates than areas with a high population of young women because of the strong correlation between age and screening rates.

21 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016, customised report. Victorian Female Estimated Resident Population by Postal Area at 30 June 2014 and 30 June 2015.

22 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. Cervical screening in Australia 2014-2015. Cancer series no.105. Cat. no. CAN 104. Canberra: AIHW.

23 2014 Postcode to LGA converter algorithm (based on 2011 Mesh Block boundaries) supplied by the ABS and based on the Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS) correspondence.

24 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2011. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 1 – Main Structure and Greater Capital City Statistical Areas, July 2011. Cat. No: 1270.0.55.001.

25 Australian Government Department of Health, PHN Concordances file. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/PHNConcordances , viewed 1 December 2016.

2.3.1 PARTICIPATION BY PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORKS

On 1 July 2015, the Australian Government established the Primary Health Networks 26 (PHNs) to replace Medicare Locals. Table 2.3.1 shows the participation rates for the six PHNs in Victoria, which are partially or entirely located within Victoria, using methods discussed at the beginning of Section 2.3.

TABLE 2.3.1 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by Primary Health Network, 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

FIGURE 2.3.1 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by Primary Health Networks, 2014-2015.

The Primary Health Network of Murray overlaps the Victoria/NSW border. Refer to Appendix 3 for a map of Primary Health Networks with the Victorian State border illustrated.

2.3.2 PARTICIPATION BY HEALTH REGION

Victoria is divided into eight Health regions, with five in rural Victoria and three covering metropolitan Melbourne. Using methods discussed at the beginning of Section 2.3, the two year participation rates have been calculated.

TABLE 2.3.2 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by Health region, 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

1. 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 data: participation data by Health region is calculated as an aggregate of LGAs. Postcode/Postal Areas mapped to LGA using a 2014 converter algorithm supplied by the ABS and based on the ASGS correspondence data. Population data adjusted using estimated hysterectomy fractions from the AIHW NHMD.

Notes

ION

Les s th an 50%

• The table provides the percentage of women screened as a proportion of the eligible female population (crude rate). Women screened only includes women who have not had a hysterectomy according to information held by the VCCR.

• Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Periods covered apply to calendar years.

50% - 55%

55% - 60%

60% - 65%

FIGURE 2.3.2 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by Health region, 2014-2015.

65% - 70%

Gre ater th an 70%

Unincorporated Victoria refers to the areas within Victoria which are not administered by incorporated local government bodies.

INSET: Melbourne and surrounds

2.3.3 PARTICIPATION BY LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA

Within Victoria there are 79 Local Government Areas (LGAs). Using methods discussed at the beginning of Section 2.3, the estimated two year participation rates have been calculated.

TABLE 2.3.3 Estimated two year cervical screening rates for women resident in Victoria by Local Government Area, 2013-2014 and 2014-2015.

Pyrenees

Yarriambiack

1. Refer to Appendix 3 for maps showing LGA codes.

2. 2013-2014 and 2014-2015 data: Postcode/Postal Areas mapped to LGA using a 2014 converter algorithm supplied by the ABS and based on the ASGS correspondence data. Population data adjusted using estimated hysterectomy fractions from the AIHW NHMD. The table provides the percentage of women screened as a proportion of the eligible female population (crude rate). Women screened only includes women who have not had a hysterectomy according to information held by the VCCR.

Notes

• Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Periods covered apply to calendar years.

2.4 CERVICAL SCREENING TESTS COLLECTED BY NURSES

The credentialling of nurses every three years to perform Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) recognises nurses’ expertise and dedication to the Victorian Cervical Screening Program. This process has been set in place to allow nurses to be accountable to the public and responsible for their individual practice while at the same time maintaining a standard of excellence. The credentialling program is coordinated by PapScreen Victoria.

The Registry holds data on CSTs where nurses are credentialled and funded by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to be eligible for their own ‘practice number’ at VCS Pathology. Also included in this analysis are CSTs from nurses using private pathology services. These nurses provide cervical screening data to PapScreen Victoria, which is then provided to the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) for analysis.

During 2015, a total of 33,780 CSTs were collected and reported to the Registry by 432 credentialled nurses. This number represents 5.6% of all CSTs collected in Victoria during 2015. This figure reflects the significant role of nurses in cervical screening, with the proportion of CSTs performed by nurses having increased over the years from an initial reported figure of 0.8% (5,170 tests) in 1996 to approximately 5-6% of tests in the last 5 years. Table 2.4 shows the number and proportion of CSTs collected by nurses over the last 10 years.

TABLE 2.4 Proportion of Cervical Screening Tests collected by nurses, 2006-2015.

2.4.1 PROPORTION OF CERVICAL SCREENING TESTS COLLECTED BY NURSES BY HEALTH REGION

Data on CSTs collected by nurses were analysed by Health region. 30 The following table and figure show that the rural Health regions had a higher proportion of tests collected by nurses, for women with a cervix, than those within metropolitan Melbourne. Between 2014 and 2015 the proportion of CSTs collected by nurses increased across all Health regions except the Grampians (decreased) and Loddon Mallee (no change). The largest change between 2014 and 2015 was seen in the Hume region, which saw a 3.6% increase in the number of tests.

TABLE 2.4.1 Cervical Screening Tests collected by nurses from women resident in Victoria, by Health region, 2015.

Health region

of CSTs collected

Nurse cervical screening data highlight the important role that nurses have in the delivery of the Victorian Cervical Screening Program, particularly in relation to the substantial number of CSTs collected by nurses in recent years and the high quality of their tests. As observed in recent years, CSTs collected by nurses are more likely to have an endocervical component, which is considered to be a reflection of test quality. 27 General Practice and Community Health settings remain the main types of practices where nurses collect CSTs (88% of practice types in 2015). 28 During 2015, 42.5% of the CSTs collected by nurses were from women over 50 years of age compared with 33.2% collected by other provider types in Victoria during this period. 29

1. Excludes 284 post-hysterectomy CST, 534 CST with interstate postcodes or not able to be mapped, and 241 CST where postcode was missing.

2. Excludes nine nurses with interstate postcodes.

Notes

• Department of Health, Modelling GIS and Planning Products Unit (2013). Concordance file created using Australia Post postcode file, ABS digital geographic boundaries (Cat. no. 1270.0.55.006) and Health regions.

• The 3,896 tests from nurses using private pathology services are not included in these statistics as postcode was not collected.

27 VCCR, Evaluation of Cervical Screening Tests collected by Nurses in Victoria during 2015, p. 9. Available from: http://www.vccr.org/data-research/ statistical-reports/annual-nurse-reports 28 Ibid p. 4. 29 Ibid p. 8.

FIGURE 2.4.1 Proportion of Cervical Screening Tests collected by nurses from women resident in Victoria, by Health region, 2015.

Unincorporated Victoria refers to the areas within Victoria which are not administered by incorporated local government bodies.

OF CSTs COLLECTED BY NURSES

Unincorporated Victoria

2.5 CLOSING THE DATA GAPS: IDENTIFYING ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER PEOPLE, AND COLLECTING COUNTRY OF BIRTH AND LANGUAGE SPOKEN AT HOME

Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) has shown that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are four times more likely to die of cervical cancer than non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. 31 A recent analysis identified that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women resident in Queensland participate in cervical screening at a rate over 20% lower than other Australian women. 32 The national “Closing the Gap” strategy is a commitment by all Australian Governments to overcome disadvantage and improve the lives and health outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 33

Women from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds have also been identified as an under-screened group. 34 Strategies for engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and CALD women, and increasing participation, are a priority for the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) as outlined in the Victorian Cancer Plan (2016-2020).

Where provided by practitioners, laboratories, and directly by women through updates of personal information, the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) will record if a woman has identified as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, as well as her Country of Birth and Language Spoken at Home, as indicators of cultural diversity.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women

The overall percentage of women screened in 2015 who had their Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status recorded by the VCCR was 26.6% (n= 152,853). Table 2.5.1 shows the number of women by their identification as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person, the distribution for those women on the VCCR for whom these data was collected, and a comparison to distribution of those Victorian women aged 20 to 69 years identifying as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander in the 2016 Census. Of those with their identification reported to the VCCR, a higher proportion were identified as Aboriginal, or both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, than among all women in Victoria in 2016. Possible explanations include that those providers who asked, collected and reported this information to the VCCR were more likely to see Aborginal and Torres Strait Islander women, a difference in age distribution between women who are screening and the overall population, or differing levels of self-identification as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander between screening data and the 2016 census.

TABLE 2.5.1 Reporting of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status to the VCCR of women resident in Victoria screened during 2015.

1. 97.8% of women with status reported were 20-69 years.

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2016 Census of Population and HousingTable Builder Basic, Victorian data as of 5 July 2017.

Notes

• Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

• Due to rounding percentages, there may be some discrepancy in totals.

VCCR is working closely with Program Partners including the DHHS, PapScreen Victoria and VCS Pathology to improve the identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and the ongoing collection and reporting of CALD data to the Registry. VCS Pathology continues to work with nurses who collect Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) to support and encourage the identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and the recording of this information on the VCS Pathology Request Forms. Of all practitioner types, nurses have the highest rate of reporting these data, with 97.4% of CSTs collected by nurses during 2015 including this information. Table 2.5.2 shows the number and proportion of Pap tests by practitioner type, where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander information was recorded on the woman’s record.

31 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2017. Cervical screening in Australia 2014-2015. Cancer series no.105. Cat. no. CAN 104. Canberra: AIHW.

32 Whop LJ, Garvey G, Baade P, Lokuge K , Cunningham J, Brotherton JML, Valery PC, O’Connell DL, Canfell K, Diaz A, Roder D, Gertig DM, Moore SP, Condon JR. The first comprehensive report on Indigenous Australian women’s inequalities in cervical screening: A retrospective registry cohort study in Queensland, Australia (2000-2011). Cancer 2016 May 15; 122(10):1560-9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29954

33 Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Closing the Gap website. http://closingthegap.dpmc.gov.au/, viewed 1 December 2016.

34 Mullins R 2006. Evaluation of the impact of PapScreen’s Campaign on Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Women. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria.

TABLE 2.5.2 Number and proportion of Pap tests collected from women resident in Victoria during 2015 with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status recorded by Practitioner type.

Notes

• Excludes women who had a HPV DNA test (without Liquid Based Cytology) as part of the Compass Trial.

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) women

The overall percentage of women screened in 2015 who had a Country of Birth recorded by the VCCR was 22.1%. 35 The most common countries of birth outside of Australia were Vietnam, England, New Zealand, United Kingdom (includes Channel Islands and Isle of Man) 36 , China, India, Philippines, Italy, Malaysia and Greece.

The overall percentage of women screened during 2015 who had Language Spoken at Home recorded was 22.9%.9 The most common languages reported other than English were Vietnamese, Greek, Italian, Mandarin, Arabic, Chinese (not elsewhere classified), Spanish, Cantonese, Turkish and Hindi.

2.6 FREQUENCY OF EARLY RE-SCREENING

While the current Australian screening policy recommends screening every two years after a negative Pap test report, a proportion of women are screened more frequently. A small level of early re-screening can be justified on the basis of a past history of abnormality.

In late 2000, the National Cervical Screening Program adopted the following definition of early re-screening:

Early re-screening is the repeating of a Pap test within 21 months of a negative Pap test report, except for women who are being followed up in accordance with the NHMRC guidelines for the management of cervical abnormalities.

This definition recognises that some re-screening may occur opportunistically between 21 and 24 months after a negative Pap test report and this may be cost-effective.

To determine how many women are truly screened early, women with a prior cytological or histological abnormality recorded by the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) within 36 months of the index Pap test were excluded. This is in line with the national reporting of indicators by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) for the same period and is also consistent with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines.

Table 2.6 shows the number of subsequent Cervical Screening Tests (CSTs) over a 21 month period for women who received a negative Pap test report in February of 2014. These data show that 89.3% of women aged 20 to 69 years who had a negative Pap test in February 2014 had no further tests within the next 21 months (2011: 86.7%, 2012: 86.4%, 2013: 87.3%, 2014: 88.5%). Over the last decade, there has been an increase in the proportion of women with no repeat CSTs, indicating a decreasing rate of early re-screening.

Of the women who had an index Pap test during February of 2014, 10.7% were subsequently re-screened early (with at least one CST) over the next 21 months. As seen in Figure 2.6, some variation in early re-screening occurs by age group.

TABLE 2.6 Subsequent Cervical Screening Tests within a 21 month period for women aged 20 to 69 years resident in Victoria with a negative Pap test in February of 2014.

35 Women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing, are included.

36 United Kingdom (includes Channel Islands and Isle of Man) is assigned when the Country of Birth is not further specified.

Notes

• Excludes any woman whose index Pap test in February 2014 was part of the Compass trial as re-screening was not due at the routine interval of 24 months.

• Re-screening at 21 months includes women with cytology tests including conventional cytology/LBC taken as part of the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) as well as women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing.

FIGURE 2.6 Percentage of women resident in Victoria by age group who had an index Pap test in February of 2014 and then re-screened early (within 21 months).

Notes

• Excludes any woman whose index Pap test in February 2014 was part of the Compass trial as re-screening was not due at the routine interval of 24 months.

• Re-screening at 21 months includes women with cytology tests including conventional cytology/LBC taken as part of the National Cervical Screening Program (NCSP) as well as women screened as part of the Compass trial, either using cytology or HPV testing.

3. CYTOLOGY REPORTS

Cytology reports received by the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) are coded according to the 2006 Cytology Coding Schedule (refer to Appendix 1). From this coding, Pap test results are categorised into the broader groups of unsatisfactory, negative, having no endocervical component, and having a squamous abnormality or endocervical abnormality. These groupings are consistent with the cytology result types reported to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) for the national indicators for the same period.

For this analysis, the results of 574,474 Pap tests from any provider type were considered. These include Pap tests which were collected during 2015, from women of any age, but exclude post-hysterectomy smears (also referred to as vault smears).

3.1 UNSATISFACTORY PAP TESTS

An unsatisfactory Pap test result is defined as having:

• unsatisfactory squamous cells (SU) and unsatisfactory endocervical cells (EU), or

• unsatisfactory squamous cells (SU) and no endocervical cells (E0) or no endocervical abnormality (E1).

Of Pap test results received during 2015 by the VCCR, 16,682 were recorded as having an unsatisfactory result. This equates to 2.9% of Pap tests. The National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC) Performance Measures for Australian Laboratories Reporting Cervical Cytology (NPAAC 2006) includes a recommended standard for the proportion of specimens reported as unsatisfactory as between 0.5% and 5.0% of all specimens reported. 37

3.2 NEGATIVE PAP TESTS

A negative Pap test result is defined as having squamous cells with no abnormality (S1) and no endocervical cells (E0) or no endocervical abnormality (E1).

Of the Pap test results received during 2015 by the VCCR, 523,157 were recorded as having a negative result. This equates to 91.1% of Pap tests.

3.3 PAP TESTS WITHOUT AN ENDOCERVICAL COMPONENT

The presence of endocervical cells within a Pap test specimen is considered to be an indicator that the transformation zone (TZ) of the cervix has been sampled. Most pre-cancerous abnormalities of the cervix arise in the TZ. Pap tests identified as not containing an endocervical component (ECC) are coded as having a result of E0 for the endocervical cell result.

Of the Pap test results received during 2015 by the VCCR, 164,626 were recorded as not having an ECC present in the specimen. This equates to 28.7% of Pap tests.

As illustrated in Figure 3.3, the proportion of Pap tests without an ECC has gradually increased from 21.4% in 2005 to 28.7% in 2015 (p < 0.0001).

3.3 : Percentage of Pap tests from women resident in Victoria without an endocervical component, 2005-2015.

The proportion of Pap tests containing an ECC has also been declining at a national level. VCCR therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the hypothesis that ECC negative (ECC-) Pap tests may be associated with reduced sensitivity. This study confirmed that women without ECC had a lower rate of confirmed HGA but found no significant increase in the rate of invasive cervical cancer following ECCtests. The results do not support differential (accelerated) follow-up in women with a negative test without an ECC. 38

component: A cohort study with 10 years of follow-up. Int J Cancer 2014 Sept 1;135(5):12139.

3.4 PAP TESTS WITH A SQUAMOUS ABNORMALITY

As seen in Table 3.4, the number of Pap tests collected during 2015 with a squamous cell abnormality (an abnormality of possible low-grade lesion or worse) was 34,357, which equates to 6.0% of all Pap tests for the year. The proportion of Pap tests with definite high-grade abnormality (i.e. highgrade lesion with or without possible micro-invasion or invasion, invasive squamous cell carcinoma) was reported as 0.7% in 2015.

TABLE 3.4 Number and percent of Pap tests collected from women resident in Victoria in 2015 with a squamous abnormality.

3.5 PAP TESTS WITH AN ENDOCERVICAL ABNORMALITY

The presence of endocervical cells within a Pap test specimen is necessary for the detection and reporting of glandular abnormalities including atypical cells, possible high-grade lesions, endocervical adenocarcinoma in situ and adenocarcinoma.

The following table shows the proportion of Pap tests for 2015 where an endocervical abnormality was detected. Pap tests which are known to have been collected post-hysterectomy are excluded. For 2015, the total number of Pap tests with an endocervical abnormality (atypical endocervical cells of uncertain significance or worse) was 409, which equates to fewer than 0.1% of all Pap tests for the year.

TABLE 3.5 Number and percent of Pap tests collected in 2015 from women resident in Victoria with an endocervical abnormality.

(S6)

3.6 TYPE OF TESTS

As per the Cytology Coding Schedule (Appendix 1), the VCCR records the type of Pap test taken as:

• conventional cytology (A1)

• liquid-based specimen (A2), or

• split sample, i.e. conventional and liquid based specimen (A3).

During 2015, the proportion of liquid-based tests (A2 and A3) was 4.9% of all tests reported to the Registry. Nearly all of these tests were “split samples” (A3), where the conventional Pap smear is accompanied by the liquid-based specimen. Only 0.5% of all Pap tests were liquid-based specimens only (i.e. A2). As for Compass liquid-based specimens (A4), the proportion was 2.23% of all tests.

4. HISTOLOGY REPORTS

This section describes the histology reports that were notified to the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR) during 2015. From October 2015, the new Victorian Improving Cancer Outcomes Act requires mandatory reporting of all cervical screening tests and relevant histology to the Registry. All cancers must also be notified to the Victorian Cancer Registry by laboratories, hospitals and the VCCR.

In 2015, there were 21,822 histology reports relating to the cervix received by the VCCR. The following table shows the distribution of histology findings for 2015. Note that data presented in Table 4 includes all histology reports received by the VCCR, and are not restricted to the most severe report for a woman.

TABLE 4 Histology findings reported to the VCCR in 2015.

1. The number of histology reports notified to the VCCR as at 1 December 2016.

2. Carcinoma of the cervix – other: includes small cell carcinoma and other malignant lesions (may include tumours of non-epithelial origin).

5. HIGH-GRADE ABNORMALITY DETECTION RATES

In 2015, the overall rate of histologically-confirmed high-grade abnormalities detected in Victoria for women aged 20 to 69 years was 6.66 per 1,000 women screened. 39

Figure 5.1 illustrates the detection rate of histologically-confirmed high-grade intraepithelial abnormalities per 1,000 screened women for each year from 2011 to 2015 by five year age group. The graph clearly illustrates that younger women have a much higher rate of high-grade abnormalities than older women. The higher rates of abnormality in younger women are a result of incident HPV infection following the onset of sexual activity. Women aged 20 to 24 years in 2015 were 12 to 16 years in 2007 when the HPV vaccination program commenced, so are less likely than older vaccine eligible cohorts (aged up to 34 in 2015) to have been infected with high-risk HPV types through sexual activity prior to vaccination. Therefore we expect to see increasing vaccine effectiveness against high grade abnormalities detected amongst women in this age group over time, which is indeed what is observed for 20 to 24 year old women in Victoria. Historically this age group had the highest rates of abnormalities but from 2010 the rate has been higher amongst 25 to 29 year olds. Since 2008, the rate in 20 to 24 year olds has fallen from 21.1 (not shown in figure) to 9.2 per 1,000 in 2015 (p<0.0001) (2009=18.7; 2010=17.9; 2011=15.8; 2012=15.3; 2013=13.5; 2014=11.0).

FIGURE 5.1: Detection rate of high-grade intraepithelial abnormalities (histologically-confirmed from 2011-2015 per 1,000 screened women, Victoria, Australia.

Also notable is that, following an underlying increasing trend in incidence as still being observed in the 35 to 39 year old and 40+ age groups, the high-grade detection rate for 25 to 29 year old women for 2015 has fallen for the third year in a row (2008=18.4, 2009=18.9, 2010=18.1, 2011=18.8, 2012=18.8, 2013=17.7, 2014= 15.5, 2015=14.5). This suggests that the vaccination coverage rate in this age group may now be sufficient to be preventing new infections and high-grade disease, despite many women in this age group having been sexually active prior to vaccination.

According to the National HPV Vaccination Program Register (NHVPR), Victorian women aged 15 to 19 years in 2015 have a notified three-dose vaccine coverage of 72.2%, those aged 20 to 24 years have a notified coverage of 61.6% and those aged 25 to 29 years have a notified coverage of 37.1% (NHVPR, unpublished data).

39 Note that the method used to calculate the rate of high-grade abnormalities is consistent with the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Indicator 4.2 (Refer to: AIHW 2016. Cervical screening in Australia 2013–2014. Cancer series no.97. Cat. no. CAN 95. Canberra: AIHW). Women screened by the Compass trial are excluded.

Figure 5.2 shows the rate of histologically-confirmed high-grade cervical abnormalities by year since 2000, for young women (<20 years, 20 to 24 years, 25 to 29 years, 30 to 34 years, 35 to 39 years) and those 40+ years of age. The previously noted decline 40 in women under 20 years of age (following the implementation of the National HPV Vaccination Program between 2007-2009) is continuing, with the rate reduced by nearly 75% from 11 cases per 1,000 women screened in 2006 down to three cases per 1,000 in 2015 (p<0.0001). Also notable is the declining high-grade detection rate for women aged 20 to 24 years, with the rate progressively and continuously declining since 2008, and the commencement of declining rates in the 25 to 29 year old age group more recently.

recorded on the VCCR.

Notes

• 40+ yrs includes all women aged 40 years or older and is not restricted to an upper age of 69 years.

6. CORRELATION BETWEEN CYTOLOGY AND HISTOLOGY REPORTS

Tables 6.1 and 6.2 show the correlation between cytology results and histology findings. The correlation is restricted to cytology performed in 2014 where a subsequent histology test was reported within six months. Colposcopy reports, without histological confirmation, have been excluded from this analysis.

In interpreting this information, it is important to consider that only a minority of low-grade cytology (atypia and CINI) is further investigated by colposcopy or biopsy, and an even smaller percentage of negative cytology reports are followed by colposcopy or biopsy. Women who have a biopsy are likely to be an atypical subset of the whole group of women with negative or low-grade cytology reports (for example they may be women with repeated low grade results over a long period of time or women with symptoms).

The correlation data presented uses the Cytology Coding Schedule implemented in July 2006 (refer to Appendix 1), which is based on the Australian Modified Bethesda System of 2004. The following correlation tables compare the cytology result with the most severe histology finding within a six month period (including same day), for squamous and endocervical

abnormalities. The histology classification and method of correlation presented is consistent with the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) national reporting indicators. It is based on the test, not the woman, and these data include women aged 20 to 69 years at the time of the cytology test. They also include the records of women who reside outside of Victoria but have data recorded on the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR).

Where a definite high-grade squamous cytology result was reported, 74.3% (2,735/3,683) of cytology tests were subsequently followed by a high-grade histology at biopsy (including high-grade CIN not otherwise specified, CINII, CINIII and micro-invasive and invasive squamous carcinoma). This figure represents the positive predictive value of a highgrade cytology report for high-grade squamous histology. The National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC) performance standards require that not less than 65% of cytology specimens with a definite high-grade epithelial abnormality must be confirmed on histology within six months as having a high-grade abnormality or cancer. 41

TABLE 6.1 Correlation of squamous cytology to the most serious squamous histology within six months, for women aged 20 to 69 years, for cytology tests performed in 2014.

1. Negative cytology: no abnormal squamous cells or only reactive changes.

2. Possible high-grade cytology: includes possible high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

3.

4. SCC: Squamous cell carcinoma.

Notes

Women with a Pap test report of ‘atypical endocervical or glandular cells of uncertain significance’ (E2) have glandular (or endocervical) cells on their smear which, in the opinion of the reporting pathologist, appear unusual but are not sufficiently abnormal to justify a more significant diagnosis. Unfortunately there is overlap in the cellular features caused by benign, inflammatory changes (by far the most common cause) and more significant processes such as pre-cancer (occasionally) and cancer (rarely). The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guidelines 42 recommend colposcopy as an initial evaluation because of the risk of

invasive cancer. 43 This elevated risk has been confirmed internationally in a recent long term registry follow-up study in Sweden. 44 As seen in Table 6.2, of the 18 women with cytology reports of ‘atypical endocervical or glandular cells of undetermined significance’ (E2), one woman who underwent histological evaluation within six months was subsequently diagnosed with invasive cancer. The positive predictive value of an abnormal endocervical cytology report (E2-E6) for high grade endocervical abnormality on histology was 92.8% (116/125).

TABLE 6.2 Correlation of endocervical cytology to the most serious endocervical histology within six months, for women aged 20 to 69 years, for cytology tests performed in 2014.

1. AIS: Adenocarcinoma in situ.

2 Endocervical adenocarcinoma- invasive: includes adenocarcinoma and embryonal/clear cell carcinoma.

3 Carcinoma of the cervix- other: includes small cell carcinoma and other malignant lesions (may include tumours of non-epithelial origin).

4 Glandular cytology: includes atypical glandular cells of uncertain significance (E2).

5 Possible high-grade cytology: includes possible high-grade endocervical glandular lesion.

Notes

• The correlation excludes diagnosis based on colposcopic impression alone. This analysis allows for cytology to be the same day as cancer diagnosis.

• Due to rounding percentages, there may be some discrepancy in totals.

41 National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC). Performance Measures for Australian Laboratories Reporting Cervical Cytology (Third Edition 2015), Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health.

42 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2005. Screening to prevent cervical cancer: guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities, Canberra: NHMRC.

43 Mitchell HS. Outcome after a cytological prediction of glandular abnormality. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol. 2004; 44(5):436-40.

44 Wang J, Andrae B, Sundström K, Ström P, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J, Sparén P. Risk of invasive cervical cancer after atypical glandular cells in cervical screening: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2016; 352:i276. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i276

7. FOLLOW-UP AND REMINDER PROGRAM

The VCCR Reminder and Follow-up Protocol (refer to Appendix 2) adheres to the 2006 NHMRC Guidelines. As part of the follow-up service provided by VCCR, a total of 503,013 follow-up and reminder letters were mailed to women and practitioners in 2015.

Follow-up

The VCCR actively follows up women with screen detected abnormalities on their Pap tests. Women with high grade abnormalities are followed up more intensively. In 2015, 7,396 Victorian women had a high-grade abnormality reported on one or more of their Pap tests, 6,830 (92.3%) of whom were followed up with colposcopy and/or biopsy within the following nine months. A further 258 (3.5%) of women with high-grade abnormalities predicted on their Pap tests in 2015 were followed up with a Pap test only.

During 2015, the VCCR sent out 1,627 questionnaires to healthcare providers seeking further information after a high-grade abnormality Pap test result and 4,504 after a low-grade abnormality result. These questionnaires are part of the follow-up of abnormal tests and seek information on colposcopy or biopsy to appropriately adjust the follow-up interval. The VCCR also sent out 15,200 reminder letters to healthcare providers following low-grade or unsatisfactory Pap test results.

During the year, 689 women with a high-grade abnormality required further follow-up by the VCCR as no further information had been received by five and half months after their Pap test. For these women, at least one phone call to the healthcare provider was made to ascertain follow-up, with many requiring additional calls. In 391 cases, the Registry sent letters to these women, mostly by registered mail to ensure that they were aware of their abnormality and to encourage them to seek further care from their healthcare provider.

Of the 51,914 women with low grade Pap test results related to the 2015 VCCR follow up and reminder program, 28,000 women required follow up and reminder actions. In total, 55,884 follow up actions occurred for low grade women, including 13,966 reminder letters. The VCCR also sent 2,332 letters to women with low grade abnormalities as further information had not been received by the recommended Reminder and Follow-up Protocol time interval.

Reminder Correspondence

A total of 478,776 reminder letters were sent to women in 2015. There were 337,641 first reminder letters and 141,135 second reminder letters sent. All letters are printed in-house weekly for mail-out. The following table is a summary breakdown of the VCCR first and second reminder activities during 2015.

First Reminders to Women

Between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2015, 337,641 first reminder letters were sent to women in the categories shown in Table 7.

Of the 322,276 first reminders sent after a negative Pap test, 101,010 (31.3%) women had a subsequent Pap test within three months of the date of the reminder.

Second Reminders to Women

Between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2015, 141,136 second reminder letters were sent to women, in the categories shown in Table 7.

Of the 134,575 second reminders sent after a negative Pap test, 23,768 (17.7%) women had a subsequent Pap test within three months of the date of the reminder.

8. CERVICAL CANCER INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY IN VICTORIA

8.1 INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY RATES

The aim of the National Cervical Screening Program is to reduce the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer. Data on cancer incidence and mortality in Victoria are collected by the Victorian Cancer Registry (VCR) and notifications are compulsory from laboratories, hospitals and the Victorian Cervical Cytology Registry (VCCR).

During 2015, 181 new cases of cervical cancer (all types) were reported to the VCR, and 41 Victorian women died due to cervical cancer. 45

Figure 8.1.1 shows the incidence and mortality rates from cervical cancer in Victoria from 1982 to 2015. The incidence of cervical cancer has declined dramatically since the 1980s, with a considerable decline from the mid-1990s. There was a plateau in incidence in 2000 and the rate has remained relatively stable since that time at between four and five per 100,000 women. A slight increase in incidence was noted in 2012 (5.7 per 100,000 women), which has been followed by a subsequent decline to 4.5 per 100,000 women during 2015.

The mortality from cervical cancer in Victoria has declined gradually over time and since 2002 has been around one per 100,000 women, which is among the lowest in the world. 46 The mortality rate for all types of cervical cancer in 2015 was 0.8 per 100,000 Victorian women (2013: 1.0 and 2014: 1.0).

Figure 8.1.2 shows the age-standardised incidence rates for cervical cancer by histological subtype over time. The greatest impact of the National Cervical Screening Program has been on invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, with

age-standardised incidence rates in Victoria declining from 6.3 per 100,000 women in 1989 to 2.1 per 100,000 in 2015. Incidence rates for micro-invasive cancer have increased slightly since 2000; and in 2015 were 0.8 per 100,000 women screened (2012: 1.0, 2013: 1.4 and 2014: 1.0). Cytology based cervical screening is less effective for the detection of adenocarcinomas, 47 which now represent a larger proportion of all cancers due to the success of the program in reducing the incidence of squamous cancers. It is anticipated that the National HPV Vaccination Program will reduce the future incidence of adenocarcinomas and it is likely that HPV based cervical screening will be more effective than cytology based screening at detecting the glandular precursor lesions (adenocarcinoma in situ) of these cancers.

Figure 8.1.3 shows the age-specific incidence rates of cervical cancer by histology and age, grouped over the three year period of 2013 to 2015. The age-specific incidence of invasive squamous cervical cancer increases in the 30 to 34 year old age group, followed by subsequent peaks in women aged 45 to 49 years, 55 to 59 years, 70 to 74 years, and 85+ years. Microinvasive cervical cancer has a small initial peak in women aged 25 to 29 and its highest peak amongst women 35 to 39. Incidence declines steadily thereafter with a small secondary peak in women 75 to 79 years. Other cervical cancers peak at 40 to 44 years of age and decline steadily thereafter with a second peak in women aged 85+ years.

Figure 8.1.4 shows that from 2013 to 2015, the rates per 100,000 women diagnosed with cervical cancer in Victoria peak for those aged 35 to 39 years (11.7) followed by women aged 40 to 44 years (11.5) and women 85+ years (10.7).

Notes

• Source: Victorian Cancer Registry, Cancer Council Victoria 2015.

45 Thursfield V, Farrugia H. Cancer in Victoria: Statistics & Trends 2015. Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne 2016. Figures presented here vary slightly from those in the previous published report due to availability of updated information.

46 International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012, online analysis. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/online.aspx , viewed 1 December 2016.

47 National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2005. Screening to prevent cervical cancer: guidelines for the management of asymptomatic women with screen-detected abnormalities, Canberra: NHMRC.

FIGURE 8.1.1: Age-standardised incidence and mortality rates for all types of cervical cancer in Victoria, 1982-2015.

• Figures may vary slightly from those provided in previous years due to updated information on diagnosis date, morphology, etc.

• Source: Victorian Cancer Registry, Cancer Council Victoria 2017.

FIGURE 8.1.2: Age-standardised incidence rates for cervical cancer by histological subtype in Victoria, 1982-2015.