Volume 16, Issue 2 Sex

Ink Magazine is produced at the VCU Student Media Center. P.O. Box 842010 Richmond. VA. 23284-2010 Phone: (804)828-1058 Ink Magazine is a student publication, published bi-annually with the support of the Student Media Center. To advertise with Ink, please contact our advertising representatives at advertisesmc@vcu.edu. Material in this publication may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from the VCU Student Media Center. All content copyright © 2024 by VCU Student Media Center, All rights reserved. Printed locally at Carter Printing Co.

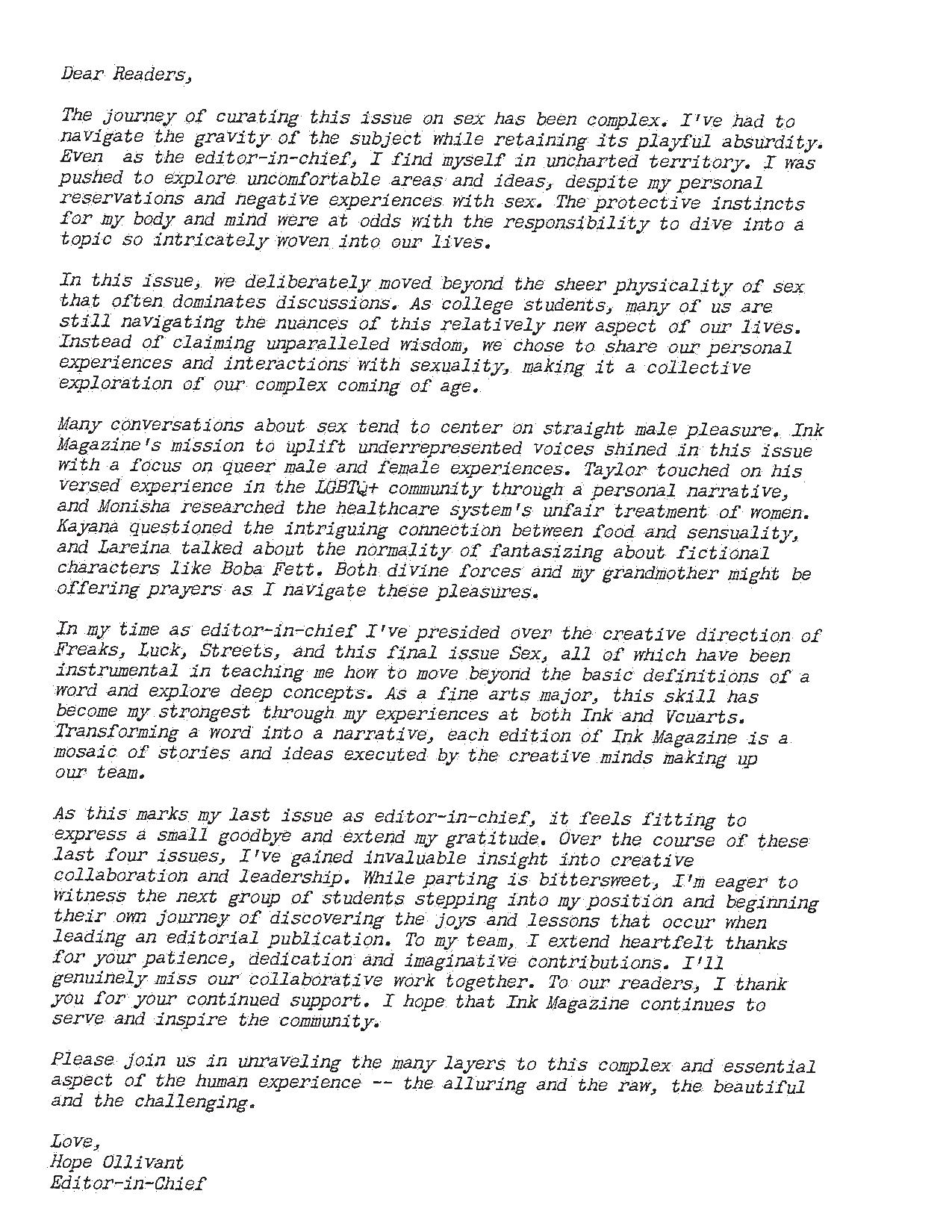

Hope Ollivant Editor in Chief

Monisha Mukherjee

Literary Editor

Stella Tessarollo Art Editor

Kobi McCray Photography Editor

Andrew Kerley

Senior Copy Editor

Sydney Folsom

Graphic Design Editor

Julianne Lane Music Editor

Kayana Jacobs Fashion Editor

Natalie Uhl Social Media Manager

Naomi Lilac Gordon Newsletter Editor

Front Cover

Isaiah Mamo

Back Cover

Caleb Goss

Selah Pennington

Layout Design

Sydney Folsom

Caleb Goss

Lesly Melendez

Hope Ollivant

Stella Tessarollo

Director of Student Media

Jessica Clary

Business Manager

Owen Martin

Creative Media Manager

Mark Jeffries

Contributors

Marty Alexeenko

Lareina Allred

Lydia Behler

Mya Blys

Yaa Boachie

Emerald Capers

Amyna Dawson

Julie Dinh

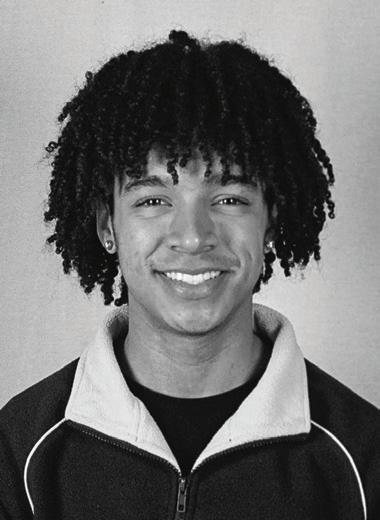

Taylor Gayot

Caleb Goss

Suong Han

Nathan Hosmer Nevarez

Amanda Hurst

Zoya Javaid

Chloe Johnson

Nova Kayne

Isaiah Mamo

Selah Pennington

TC Priest

Beaux Reeder Bijoux

Harley Salmen

Isabelle Samay

Peake Webb

1 INK

2

Staff Photos 4-5; Trans//Sexuality 6-9; Nymph 10-13; But I’m A Lesbian 14-17; Girl Rap 18-20; Mad Lib 21; On The Line 22-25; Don’t Worry 26-29; STUD 30-35; I Want to F*ck Boba Fett 36-39

Staff Photos 4-5; Trans//Sexuality 6-9; Nymph 10-13; But I’m A Lesbian 14-17; Girl Rap 18-20; Mad Lib 21; On The Line 22-25; Don’t Worry 26-29; STUD 30-35; I Want to F*ck Boba Fett 36-39

4

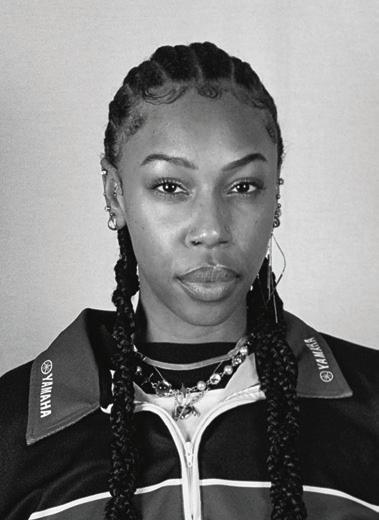

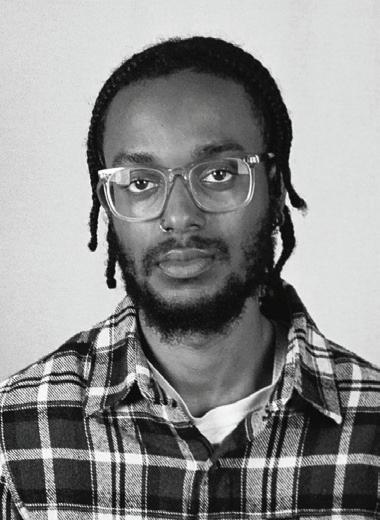

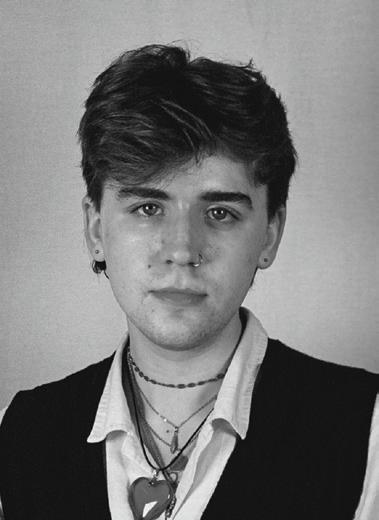

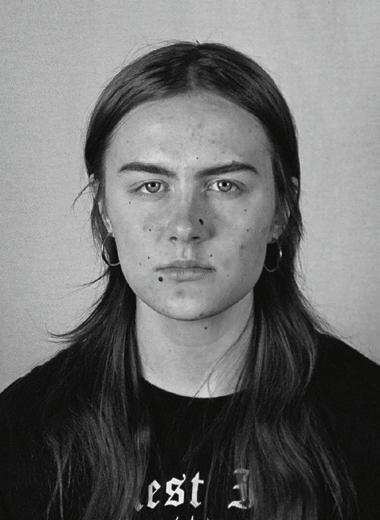

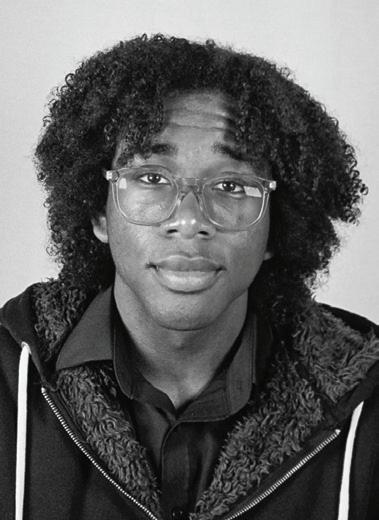

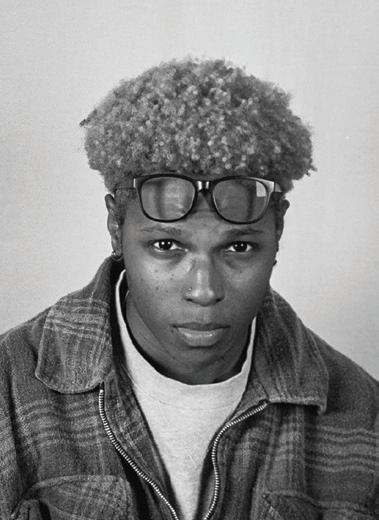

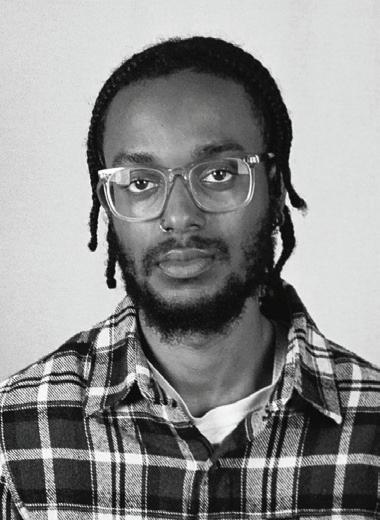

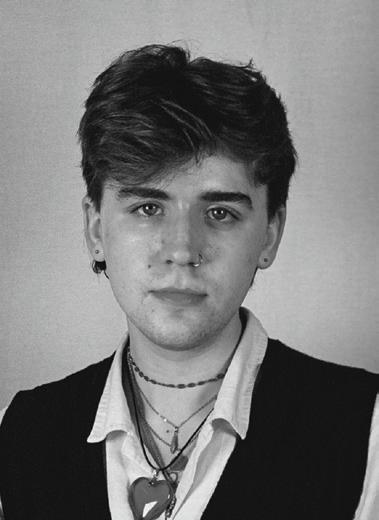

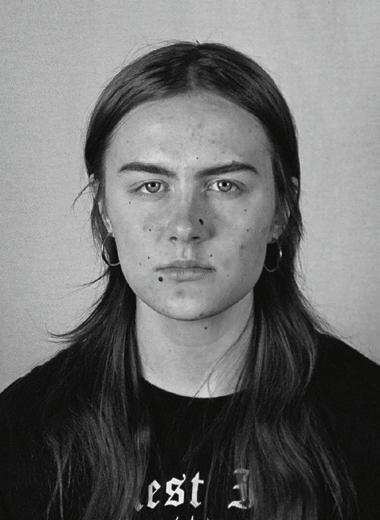

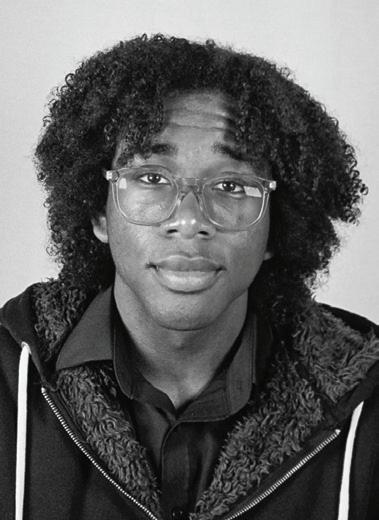

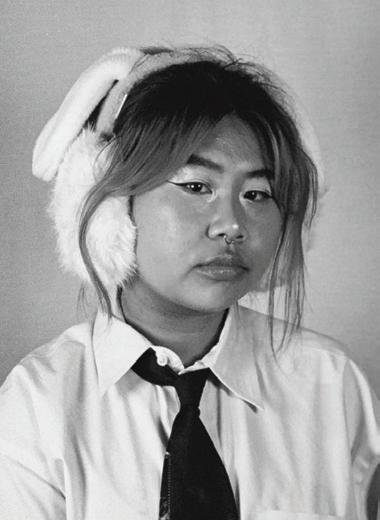

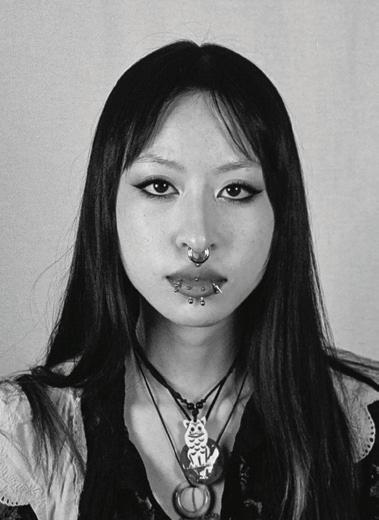

Akili Williams

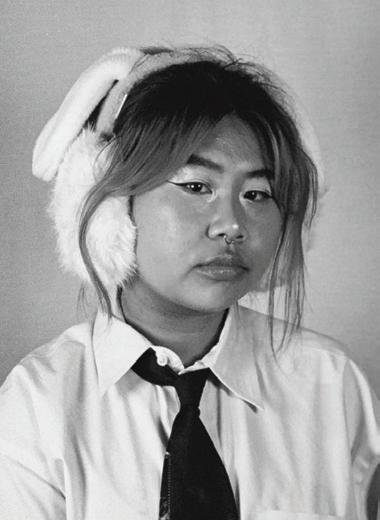

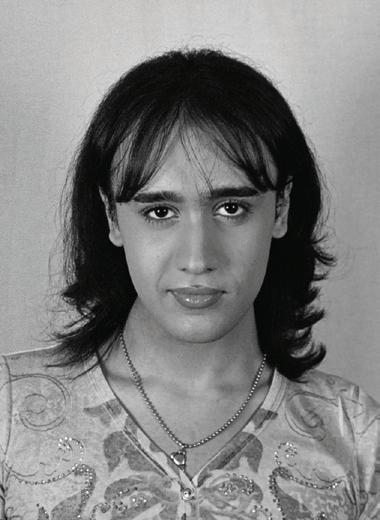

Amyna Dawson

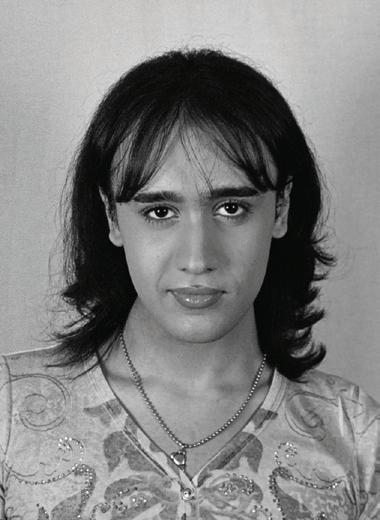

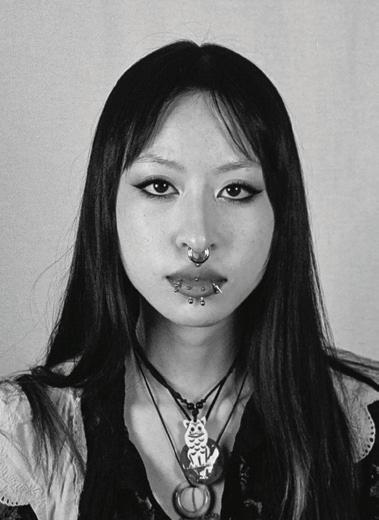

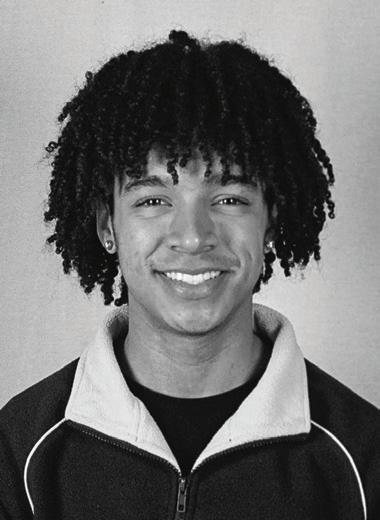

Kobi McCray

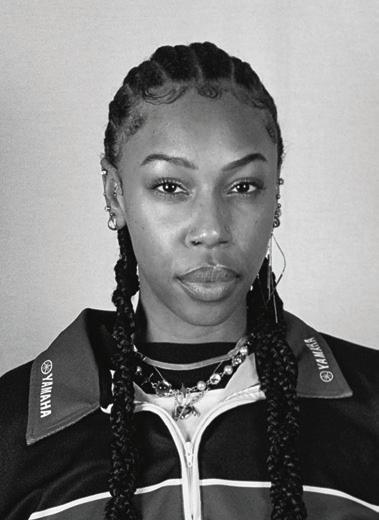

Ryan Benson

Lesly Melendez

Marty Alexeenko

Natalie Uhl

Asha Hubbard

Sydney Folsom

Hassam Virk

Stella Tessarollo

TC Priest

Amanda Hurst

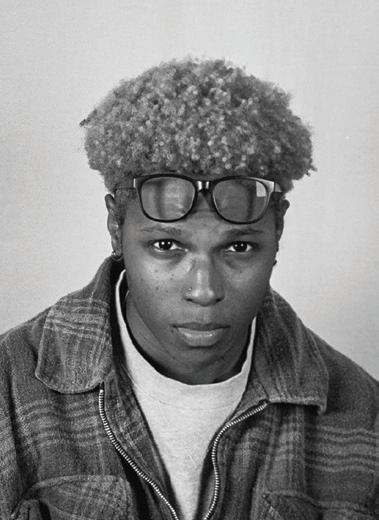

Monisha Mukherjee

Julianne Lane

Zoya Javaid

Mason Rowley

Claudia Andrade-Ayala

Walker Cosby

Erin Dakota

Paige Perkins

Jaylyn Johnson

Jasmine Purchas

Caleb Goss

Julie Dinh

Lydia Behler

Elliot Crotteau

Antonio Smith

John Gregory

Kendahl Bell

Evelyn Vandrey

Isaiah Mamo

Peake Webb

Cristina Sayegh

Samah Elhassan

Isabelle Samay

Andrew Kerley

Megan Piston

Beaux Reeder Bijoux

Hope Ollivant

Kayana Jacobs

Lareina Allred

Chloe Johnson

Selah Pennington

Naomi Lilac Gordon

5 INK

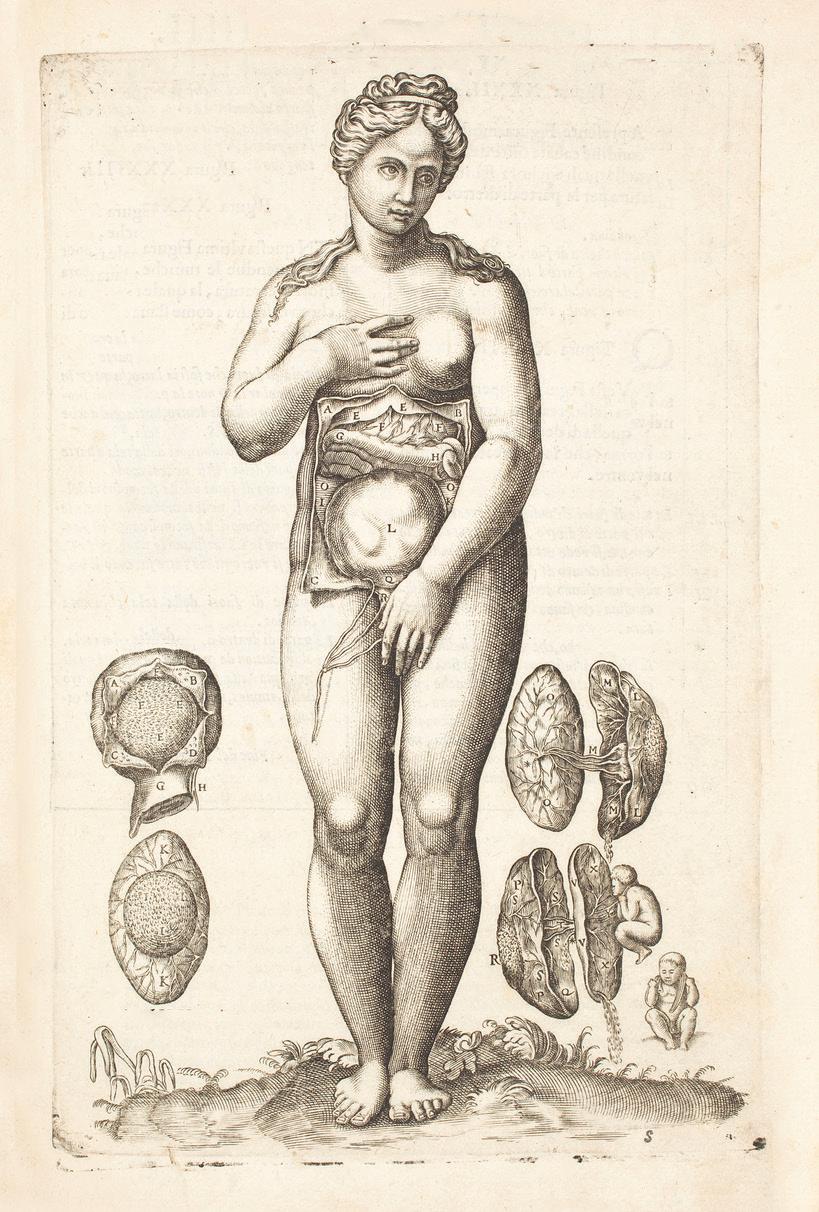

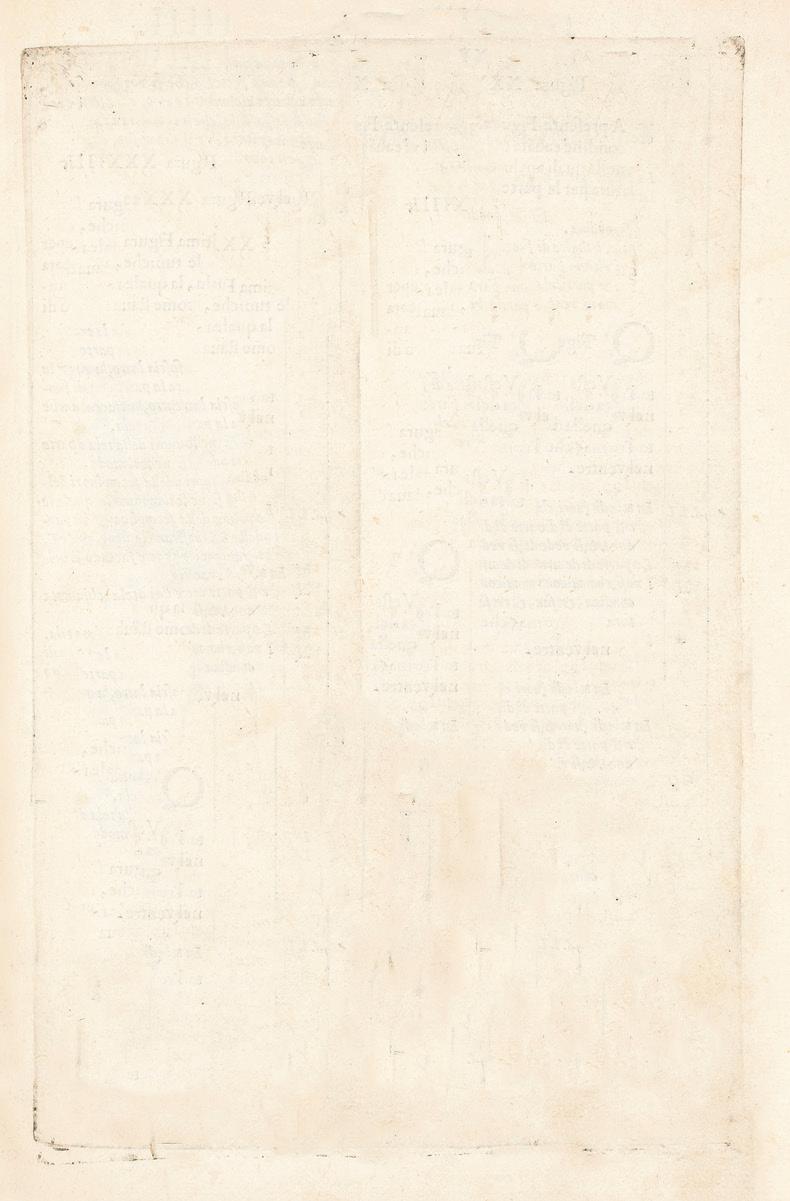

Written by: TC Priest

Illustration by: Isabelle Samay

Written by: TC Priest

Illustration by: Isabelle Samay

My husband and I are legally registered lesbians.

On May 12, 2021, the two of us sat at a little desk in the John Marshall Court building to sign our marriage license.

“Okay, now please fill out your gender, sign and date.”

Owen and I held our breath and looked at each other. I took a beat then spoke up, a bit hesitant, trying to assess this middle-aged woman with the highlighted pixie cut sitting across from us (I’m remembering her as a white, early-aughts Halle Berry). “So… does this need to reflect our government IDs? Or can we mark how we… identify?”

“Oh… well, um,” she looked between us, pulling her lips into her mouth in nervous contemplation, then continued, “Please go ahead and put whatever you… are… today.”

What we “were” that day were two adults about midway through our second puberties with patchy facial hair, voices in an indiscernible octave range and big Fs on our IDs.

God bless that woman. She had no idea what to make of us, but she was doing her very best to be open to whatever it was she was looking at. Love is love, you know? Love wins. In the eternal words of Jennifer Lawrence: Gay Rights!

Growing up assigned female at birth, I had crushes on boys and desires for very strong friendships with girls (i.e. crushes). By early teenhood, I’d recognized my feelings for girls for what they were. Around 13 I came out as bisexual to two friends. To their credit, despite their general attitude toward the whole thing (one of denial), neither dropped me over this disclosure. Nevertheless, their lukewarm reception set off my retreat to the closet.

Around this exact time, a new boy came to our school. Despite my first words about him to a friend being, “The new kid’s gay, right?” and my gender presentation at the time being incompatible with the type of person I assumed he would be attracted to, I quickly developed a

crush on him that would linger for the next year. We became good friends, but the crush was never reciprocated.

The memories from this time still have the ability to send pangs of embarrassment through my body that can stop me in my tracks in the middle of a Whole Foods, or leave me staring at my feet in a scalding shower. However, time and self-reflection have afforded me the chance to look back on this painful span of my history with clarity and compassion for my 14-year-old heart and mind. I didn’t have a crush on him as the girl I appeared to be then. I had a crush on him as the young queer boy I hadn’t yet realized I was. I’ve looked him up on social media a few times since then and I take a certain satisfaction seeing I now hold a strong resemblance to a man he dated for several years.

It took time, but after my first excursion from, and subsequent retreat to the closet, I’d come out again. Upon this second emergence, I decided I must be a lesbian. In the time between my first and second coming out, the few encounters I’d had with boys were undesirable at best, and abusive at worst, so I wrote them off completely and never thought twice about it.

At 16, in the wake of these revelations, I had my first queer relationship. At the time, we each identified as lesbians, but we’ve both since transitioned. In the queerest of ways, I think back on that relationship now as two boys in love. With the lenses of time and self-awareness unclouding my vision, I can see us as young queer boys, fumbling into a relationship based solely on our mutual love of video games, mutual attraction and mutual understanding that we were the only queers around. While the relationship itself was a disaster unfolding at 240 frames per second, we were both in desperate need of sexual experimentation with someone who made us feel safe.

I would live most of my young adulthood identifying as a lesbian; ebbing and flowing between my tendency toward masculinity, while balancing the feminine energy I knew I contained, but was terrified of expressing. Essentially, this looked like me wearing lace bras and underwear beneath thrifted Cosby sweaters or $5 t-shirts and khakis from the Target boys’ section, and being a partner who was alarmingly quick to agitation, jealousy and a persistent need for control (these would be the repression manifesting, of course).

7 INK

In my mid-twenties, I had my third coming out. I purchased my first binder and, while it helped at first, truly coming to terms with being trans was terrifying. In the two years that followed I would start and stop hormone replacements dozens of times before finally deciding it was the right thing for me and feeling brave enough to tackle the grueling years of misgendering and humiliation I knew would follow.

The changes began: the cracking vocal puberty, the sparse and slow-growing facial hair, the fullness leaving my cheeks and the aggressive nose hair no one tells you about. As my body started to resemble the mental image I’d always held of myself, confidence bloomed. People were seeing me the way I saw myself. My crippling social anxiety slowly diminished. The energy that I was able to exude, the authenticity I was able to embody, was now being returned to me by nearly everyone I spoke to. The depth of even my most basic interactions was substantially greater. The jarring whiplash of my inner world colliding with my outer reality had finally ceased. With this alignment and blossoming confidence, my mind started to allow itself to wander in ways it hadn’t since I was very young. I started to notice men again. I turned 30 last November. As the date approached, I found myself becoming more introspective than usual. More than anything, I thought a lot about early childhood; the knowing I’d had, the inborn knowledge of my self. Before I understood anything about my body being similar or dissimilar to anyone else’s, I existed as the young boy I knew myself to be. It was innate. Not until I was forced to acknowledge others’ perceptions of me differing from the way I existed in my purest essence did I feel the first instances of that jarring whiplash.

In much the same way, my childhood sexuality felt pure and autonomous. I felt strongly toward people of all kinds and assumed this to be normal. The confrontation of my innate truths with the pressures of the world forced me to consider the normalcy of these feelings. I had no language at this young age to comprehend the discomfort my inner world experienced when butting up against the outer world, but my subconscious graciously set me straight, so to speak, and took on the responsibility of designating my desires as acceptable or unacceptable. This breach of my inner sanctum by the binaries of our society infected me and mutated the phenotype of my gender and sexuality, morphing me into the gender I’d been assigned, with the appropriate sexuality to match.

Even as I began to transition, I thought, as many trans people do, that perhaps what I’d been feeling at those young ages wasn’t attraction at all, but rather feelings of envy. Do I want you, or do I want to be you? It may have been envy in part, but when I find that untouched part

8

of my self, pockets of that purest essence, I can again sense that initial untainted attraction I had toward people of all genders. But throwing off the shackles of the gender binary latched to the chasms of your mind is difficult, and I believe the metaphorical wrists of some deep part of me have been forever scarred by those bonds. For instance, I feel my ability to find men sexually attractive is tainted by the residual effects of these bonds; it hinges upon feeling I am engaging with them as someone they perceive only as a queer man. Trans friends I’ve spoken to over the years confirm these phenomena of morphing sexuality post-transition, the confused feelings of envy versus attraction, and of their sexualities being contingent upon the ways in which they are perceived by potential partners.

The language we use for our identities can paradoxically feel as specific as it is insufficient. Labels are convenient words to convey ideas about ourselves. They are important indications of our current understanding of our relationships to gender and sexuality and how we wish to be perceived. However, they are often completely inadequate tools for doing so. We mean for the words to be interpreted literally, but we also understand that there’s a billowy, gauzy strip of nuance blustering in the winds of our personal experiences of queerness. The labels I used over the years were never the wrong ones, they were exactly what worked for me at the time. Just because they have changed does not indicate a binary right or wrong. In fact, it does not indicate anything at all but the complexity of the interplay between what we know of ourselves, what we know of how we are perceived, and the way the interactions of those things make us feel. When my husband and I got together we did identify as lesbians, but by the time we’d filed our marriage license, that label and the gender markers that reflected it were obsolete.

Typical discourse tells us that gender identity and sexuality are distinct facets of a person, but many trans people’s experiences show us just how closely they can be linked to and influenced by each other. Is this evidence of those scars of cis-heteronormative bondage? Maybe, but I think it’s so much more than that. We aren’t the sum of our traumas or our societal indoctrination.

I think part of liberation is adopting queerness as an important part of ourselves and finding words that help us build a strong sense of self while ensuring we aren’t building new walls to confine ourselves with. Take it from someone who has been an L, G, B, T and a Q, don’t close yourself off to what life has to offer because of a belief you hold about yourself, whether imposed upon you or chosen freely, even if it’s just about who you think you’re allowed to f*ck. Most of us extend a pliancy to others and the fluidity of their identities, but I’m not sure we always extend ourselves the same.

9 INK

10

Creative Director and Photographer: Isaiah Mamo Stylists: Emerald Capers, Isaiah Mamo Makeup: Isaiah Mamo Model: Emerald Capers

13 INK

Lesbian BUT I’M A

14

Interview

with Professor Brooke Taylor (they/them) Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies

By: Kayana Jacobs and Peake Webb

I’ve always adored women. Since I was a child I’ve been surrounded by multi-dimensional women. Identifying as a lesbian has given me a deep understanding of my own sexuality and identity. The first time I heard anything about queer history, stories and revolutions in a classroom setting was in college. I took an intro to Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s studies course with Professor Brooke Taylor my freshman year. My heart broke for my younger self. If I were taught these things in my earlier school years rather than having to search through the lesbian archives to find any piece of media that I can see myself in, my younger self wouldn’t have felt so “othered” in their sexuality. Being able to talk about my sexuality and my love for women freely is a great privilege. Taking that class and learning about all the lesbian writers and activists has made me even more proud to identify as lesbian.

— Kayana Jacobs

INK: What does lesbian mean to you? How does the identity stand out?

BROOKE: Now I believe the term has broadened to include everyone who identifies as a woman — which I think it should. Some people still argue that point, but for me, regardless of your birth sex, if you identify as a woman and you are primarily attracted to other women, and you identify yourself as a lesbian, then you are a lesbian. I do think the identity has stood out more so in the past than it does now. With first wave feminism, being a lesbian

was an important political statement as well as an identity. We can see how that has taken shape over the decade, with lesbians playing a key role in the women’s right’s movement.

INK: Do you feel socially limited in your expression of your sexuality by social judgment?

BROOKE: I always knew that I was gay. I’ve never liked the term lesbian even before I knew my gender identity was non-binary. I just hated the term lesbian. I’ve always been attracted to women and I’ve never struggled with my sexuality, but I did struggle with how people in my life would deal with my sexuality — especially coming from a Christian background. I had to accept that there would be people who I loved who would never agree with how I understand myself. I think it came with age. I see a lot of young queer people struggling with this. As a realist, I think there will always be a level of ‘otherness’ — being a queer person in the world — but there are better pathways to community that I’ve seen in my lifetime, and I’m hopeful that continues.

INK: Could you talk about the significance of representation and visibility of lesbian sexuality in media, literature, and educational curricula?

BROOKE: We’re in a time in America where, especially in southern states, there’s a push to censor everything related to sex. We see it in the educational battles happening in Florida, and it’s starting to happen in Virginia. I think LGBTQ+ identities are important to include in middle and high school sex education, but we’re at a point where anything related to sex is being considered inappropriate. Especially in talking about

“The idea that ‘if the heterosexual male is no longer needed in sexual or romantic relationships, what is their role? ’”

15 INK

public schools right now. In Florida, any school getting money from the state can’t teach things that the state disagrees with. Critical race theory, gender and sexuality — marginalized identities really do need to come to the forefront and resist censorship.

INK: How do societal stereotypes about sexual roles and behaviors impact the way lesbian couples are perceived ?

BROOKE: The stereotypes about lesbians that come to mind, for me, have to do with there having to be a more masculine person in a relationship, or two feminine partners competing for attention, or one partner being less sexually satisfied. I think that assumption is made because in cishet relationships, there’s an expectation of a dominant and submissive partner. However, even heterosexual relationships don’t always follow the gender lines that people expect. One of the big misconceptions about the lesbian identity from the media that’s still prevalent today, is the idea that lesbians hate men. The resistance to patriarchy itself has created a narrative that women who love women, somehow, must hate men. I think that goes back to the patriarchal idea of power — the need to be needed. The idea that ‘if the heterosexual male is no longer needed in sexual or romantic relationships, what is their role?’

INK: Going off of that, some people assume that in a lesbian relationship, there’s a ‘dominant’ and ‘submissive’ partner, mirroring heterosexual relationships. Could you talk about the fallacy of this assumption and the variety of dynamics within lesbian relationships?

BROOKE: In lesbian relationships, sometimes you see ones that ‘mirror’ hetero ones, but you also see ones that are

dom/dom, stud/stud or fem/fem. Even titles like dominant and submissive take different shapes — are we talking about the way we present our gender, or who makes decisions, or sexual dominance?

INK: What do you think about the misconception that lesbian sex is not ‘real’ sex?

BROOKE: People still tend to believe if penetration is missing, then sex isn’t ‘real sex.’ It’s a misconception because the only people who need to be worried about a sexual act are the people involved. Statistically, cishet women orgasm less. The thing that’s missing from these conversations is a prioritization of pleasure, which can come from a variety of ways. Some people exclusively orgasm through clitoral stimulation, some people orgasm specifically through penetration and everything in between.

INK: How do you think the erotic serves as a tool for resistance within lesbian sexuality, particularly in the face of societal norms or oppression?

BROOKE: The erotic is about pleasure, what brings you joy, what turns you on sexually and non-sexually, what gets you up in the morning and what motivates you. I think people need to protest for their pleasure as much as we advocate for different social causes, because we only have this one life. Whether that’s traditional erotic pleasure, or learning about yourself and finding out what makes you happy — I think everyone can do that. I think that joy, especially in communities of color, communities that deal with intersectional oppression like black and brown lesbians, the most radical thing you can do is find pleasure in the face of that oppression.

16

17 INK

girl rap

Written by: Zoya Javaid

girl rap

Written by: Zoya Javaid

We all know the familiar rush of excitement that takes over–maybe you’re in your bedroom getting ready, or out clubbing with the girls – and you hear the hook to a song that’s your group’s anthem. You scream along together, to the bold and powerful tones of that familiar feminine voice. Your fave doesn’t rap about her obsession with a man but rather, how the world should be obsessed with you. Swimming in each other’s voices and erupting into laughs, it makes you remember why music is fun! We all remember the WAP craze of 2020, know the insanity that stan Twitter devolves into whenever Nicki Minaj drops a new album. Megan Thee Stallion, Flo Milli, Ice Spice, Doja Cat, Azealia Banks, and Cardi B are only a few leaders of the modern girl rap empire. This fresh unapologetic genre of music is empowering and oozes self confidence. Yet it attracts ten times more hate and criticism than any other genre. These women are repeatedly labeled crude, vapid sell outs. But this critique tells us more about the kind of society we occupy than the quality of these musicians at all.

When I was a kid, the music industry was an intimidating beast; not made for people like me. You had to be a crowd pleasing Ken doll dripping in privilege to get anywhere substantial, and being plus-sized added a different layer of insecurity too. I was always hyper-aware of the fact that I would never look like the artists I idolized. This was made crystal clear growing up in the 2000s by one detrimental thing: The Taylor Swift Effect. Taylor first entered the Billboard Top 100 in 2006, two years after I was born, and she remains popular and beloved to this day. She was easy to idolize as a kid, but as I grew into my own person, her image proved more harmful than helpful. When the “it girl” of the decade is a thin, wealthy vision of easily digestible caucasian mediocrity, it’s hard to not take your opposing characteristics as flaws that make you lesser. She set the standing for musical success that every little girl dreamed of, but instead of shattering the glass ceiling she just created a Barbie-shaped hole that everyone like me killed themselves trying to fit into.

Everything changed when I turned on the TV one day and saw music videos like Nicki Minaj’s “Superbass” and MIA’s “Paper Planes.” They opened up a whole new world for me. One where it’s not just allowed, but celebrated to be a woman of color making art that people love. As a teenager I turned to girl rap, finding showstopping artists like Maiya the Don and Rico Nasty: Exceptional lyricists creatively skilled beyond comprehension. They were the antithesis of the Taylor Effect. Women who weren’t afraid to take up space and make art, despite a society that tells them they’re doing it all wrong. They didn’t care because they were doing what they loved and making art that they were proud of. That’s all I wanted to feel growing up. Knowing that was possible changed the way I saw myself forever.

Though I myself am a practicing enthusiast, girl rap is far from loved by everyone. People from older generations and anti-feminists around the globe have taken to the

internet to complain that this type of music is nothing but trash. They see it as harmful and inappropriate to today’s youth, but these stereotypes are misguided. Girl rap is underappreciated and overlooked because white supremacy and purity culture have forged a society that doesn’t take women of color seriously in any aspect of the professional world, much less the music industry. If society saw our sexuality and experiences as normal and healthy, we wouldn’t be so widely hated and criticized, but it’s impossible for white society to leave women of color alone. They will always care about everything we do to an extreme measure. And it’s not because of “vulgar content.”

When white artists like Miley Cyrus or Brittany Spears, go through eras where they show off their bodies more or act like they don’t care what people say, the public takes it as a “rebellious phase.” It doesn’t speak for the quality of these women or even women as a whole because it’s seen as out of character for white women. It’s a costume they can throw on for a month or two to be a little bit more interesting before everyone gets bored of it. It’s not real to them. It’s an attention grab because they’ll never have to deal with that kind of reaction being their reality. Purity culture is the white woman’s baseline. They are expected to grow up wholesome and innocent, rebel from their perfect childhoods, discover their easily digestible sexuality, and then move on into frigid adult life forever. That’s how the coming-of-age movie goes, right? White women are expected to do that because purity is built into society’s vision of them. Women of color, especially Black women, don’t get that privilege. Those movies are never about them. Purity is never assumed of them. They have failed as proper women from the moment they’re born with melanin. So when brown and black women make music about expressing normal, healthy sexuality, it can only be raunchy and obscene. Everything we do is overanalyzed and criticized by the people who are waiting for us to mess up, waiting for a reason to discredit the work that we do. Anything to prove that we don’t belong on stage with them.

Women in rap have existed for decades. Missy Elliot, Salt N Pepa, Queen Latifah, and Lauryn Hill dominated the 90s and early 2000s with their sound. They paved the way, creating the essence of girl rap that we crave so much. Icons that crafted the art that so many artists take influence from. However, many argue this type of girl rap isn’t the same as what we have now. Claiming music then wasn’t as “sexed up” as it is now. They argue female musicians used to focus on the substance of their art instead of how it sells, but I disagree. Male musicians have been “selling out” since the dawn of time, but nobody shames Harry Styles for selling nail polish. It’s always “do what you gotta do” until a woman makes a decision you disagree with. Because of this, “pretty girl rappers” and their fans are treated like they’re vapid and substanceless, aiding the idea that the genre can’t be taken seriously. It’s scary how fast the world can decide to turn against women of color. Even iconic, world-famous women who everyone adores are not immune to the demonization. In 2020 Megan Thee Stallion was shot by Tory Lanez during an argument after a party. She was unarmed and had to

19 INK

" This fresh, unapologetic genre of music is empowering and oozes self confidence.

"

go through surgery and intensive recovery because of the event. Although she was a victim, the situation turned against her fast. As Lanez floundered to defend himself he villainized Megan heavily, turning his fans and the internet against her. “He lied to anyone that would listen and paid bloggers to disseminate false information about the case on social media. He released music videos and songs to damage my character and continue his crusade,” Megan said in a statement. She was harassed, receiving massive amounts of hate after already enduring a traumatic event that is still joked about online. The internet is notorious for its negativity – a given for any public figure – but women of color are not held to the same standards as other celebrities. People are practically eager to turn on us. You could be the most successful, perfect woman in the world and even when you do everything right, you’ll still be despised, just because you are a woman of color.

It’s no secret that art created by people of color has to fight to receive recognition. We celebrate diversity in any aspect of the media we consume but that is not the finish line. Art of color has to fight to be seen. That’s why casual diversity is so non-existent. We’re not in the coming-of-age movies because movies about us coming of age aren’t light and fun. They’re centered around tragedy and traumatizing hardship. Our art is extreme because our experiences are extreme. Because it has to be extreme for it to be recognized by people who haven’t lived it. So when people who’ve lived

through extremities make art about it, of course, it’s not going to be quiet and calm. It’s going to be loud, insane and showstopping. But that’s what makes it so inspiring. We love girl rap because it is a manifestation of how we feel without the world holding us back. We need things like that to make us feel powerful, to show us that it is possible. Being a woman of color is undeniably a production, a constant never-ending tightrope walk. Womanhood is a painted smile on a ceramic shell, camp and shiny. Femininity is astounding. She turns heads and gives the world something to admire. She’s an act. An ordeal, a dilemma, an experience, burlesque. She forces them to stop and listen, sickeningly sweet. She wants to burn going down your throat and force your teeth to rot. She won’t make this easy for you. Womanhood is fatal. It’s gruesome and macabre. A warning sign to everything else living, proof of how painful it all can be. Then they expect authenticity. We’re shamed for the opposite but they couldn’t handle it if we gave it to them, it’s too intertwined with our pain. The kind of tragedy nobody wants to witness. But those who know the pain applaud our performance, finally a show of their truth. And somehow through it all, through the tightrope walk, the pain and mistreatment, our resilience shines through. We make art, inspire each other, fight for what we believe in. We manage to show the world that it’s worth it to exist, no matter how excruciating it may be. To be a woman is to perform right? So why are we mad at the production style?

20

21 INK

O N T H E L I N E

23 INK

Creative Director & Photographer: Isaiah Mamo Makeup/Styling: Nova Kayne, Yaa Boachie, Nathan Hosmer Nevarez, Isaiah Mamo

Production Assistant: Maya Blys Print Assistants: Chloe Johnson, Maya Blys, Harley Salmen

Models: Nova Kayne, Yaa Boachie, Nathen Hosmer Nevarez, Emerald Capers

24

25 INK

Don’t Worry

26

Written by: Monisha Mukherjee

Written by: Monisha Mukherjee

Every year my friends and I have a little friendsgiving dinner. Our hostess friends always make mac and cheese and have some leftover turkey, and the rest of us bring some side dishes and far too many different desserts. There I was this past year, playing with my buddy’s half-deaf cat, making casual conversation, asking Rebecca if she’d got in to see the doctor. She told me she had but she couldn’t get an official diagnosis of her Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS). As soon as she said it, Arian started telling her to find another doctor ASAP. I could see the concern in her eyes and I knew her story quite well. She’d spent the last year in gut-wrenching pain unable to get any diagnosis, being told that she was just overreacting, and even being branded a “drug seeker.” She had to travel 200 miles to see a specialist covered by her insurance, and upon finding a procedure that could help her, her doctors dragged their feet on moving forward because they were more concerned about potential risks to her fertility than her pain (she also didn’t care about fertility risks). Finally there was a surgery. It turned out there was a cyst coiled around her fallopian tube that had been choking off all blood flow to her lower body. The sharing circle expanded from there, and everyone with a vagina piped up to explain their episode of abandonment by the medical establishment. It ranged from “it turned out to be nothing,” to “I almost died.”

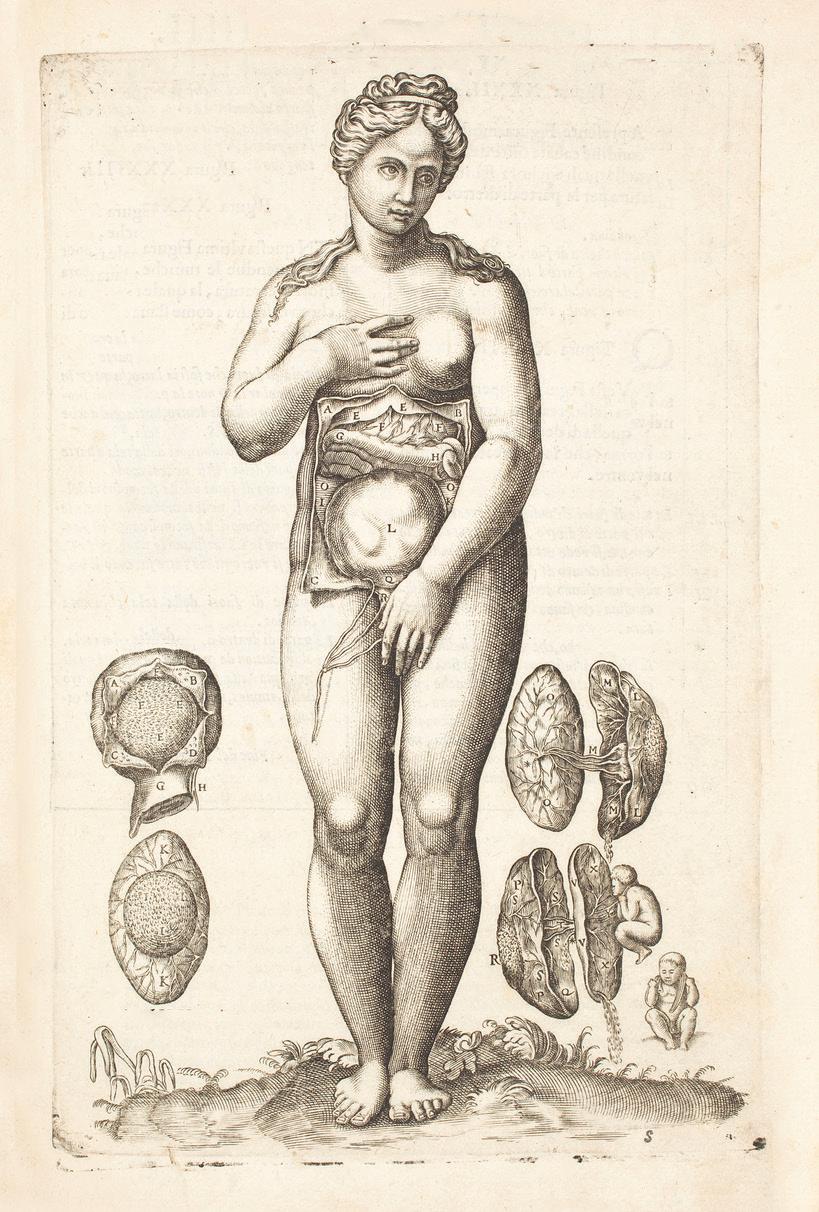

While researching for this article, I learned that the word “hysteria,” defined as an exaggerated or uncontrollable emotional state, is derived from the Greek word “hystera,” meaning “uterus.” When it comes to treating women, this word’s repurposing embodies the underlying perception of female patients perfectly. The gender gap in healthcare isn’t the result of a few dismissive doctors. It’s a systematic failure that is bleeding into all aspects of the medical system.

At this point, hearing the words “don’t worry about it,” from doctors evokes a guttural reaction in my body. I would love to say that my friendsgiving was just a poor sample size, but the statistics show otherwise. The Journal of Women’s Health stated that those who visit the ER with chest pain and other symptoms related to heart disease are twice as likely to be diagnosed with a mental illness than their male counterparts. Another study by Academic Emergency Medicine showed women were 25% less likely than men to be treated with opioids for acute abdominal pain. I could keep listing for hours, but the point is made clear by the fact that the dismissal of women’s concerns in medicine is so common it has its own term: “medical gaslighting.” The perpetuation of medical gaslighting isn’t all just hater doctors, it’s more about a subconscious attitude woven into the medical community. “While some gaslighting is done consciously, a lot of it happens unconsciously, too. A triage nurse may not deliberately tell a woman who comes to the ER complaining of chest pain that it’s all in her head, but she may notice that she’s very anxious and subconsciously make that assumption”, Dr. Mieres of the Katz Institute for Women’s Health explained in an article with Northwell Health.

Whether it’s intentional or not, women often feel talked down to by medical personnel, and therefore uncomfortable going to them for help, especially when it involves sexual health. According to the organization Jean Hailes for Women’s Health, their most often visited pages are those on vulvar and vaginal health, showing that women feel more comfortable searching for information on their own than asking their healthcare providers.

The discomfort is heightened even more by the extreme focus many doctors have on weight. According to a study by Obesity, 69% of women have experienced weight- related discrimination by a doctor. Teresa Altomare, a middle-age woman named in a Glamour article of weight-shaming in medicine, explained how one doctor even told her she was too fat for a proper cervical exam. Two weeks later, a Planned Parenthood was able to do the cervical exam without issue. Oftentimes, discussions of reproductive health and treatment plans to address discomfort or illness in reproductive organs will leave patients at odds with their doctors, rather than receiving support. A Vox article explained an example where a young woman with adenomyosis, an illness of the uterine lining that leads to chronic pain and bleeding, had found that a hysterectomy, a surgical procedure to remove the uterus, could present an end to her constant pain. Despite the patient being educated and aware of her choice and its effects on her future health, the hospital intervened, stopping the procedure as they viewed it as unnecessary sterilization. Patients are supposed to have medical autonomy, to make their own informed decisions, yet many doctors and hospitals try to force their own beliefs onto their patients. This focus on preserving what society believes a woman should value is geared towards making healthy future moms, and not necessarily healthy people.

27

When it comes to anything sex-related, it also doesn’t help that doctors do not receive adequate training. The Washington Post explained in an article on sexual shame how many doctors carry conservative beliefs into their work leaving them ill-prepared to adequately address individual needs when it comes to sexual organ-related health. They also pointed out that it doesn’t help that medical schooling is quite inadequate in this area and the lack of information and training has providers operating on personal belief, leaving their patients feeling ashamed and uneager to go to them for help.

Should a woman manage to weave through the snake pit of doctors who dismiss her and find a trusted physician, she will come to another hurdle, the dumpster fire known as medical insurance. According to FortuneWell, women are annually spending fifteen billion dollars more than men for out-of-pocket expenses, not including pregnancy costs. For most women, it is too expensive to be alive when they are healthy, and it is bankrupting to try to maintain their health when it slips. There is also a unique barrage of medical issues such as miscarriage, endometriosis, PCOS and menopause, which all often involve extensive out-of-pocket care, according to The Helm.

On top of that, after the roll-back of the birth control mandate, companies no longer have to offer all forms of birth control. So if a woman’s boss doesn’t want to offer the pill, they don’t have to. Despite the thousands of women who rely on it for dealing with hormone imbalances, period pain and the desire to have safe sex and not get pregnant.

All of this comes with the caveat that a woman can afford insurance. According to a source in Women’s Health, one in five uninsured people skip treatment because they can’t afford the cost of care. The International Federation of Health Plans lists the cost to stay a day in a hospital without insurance as $5,220. Getting your appendix removed is $15,930 and giving birth in a hospital is $10,808; surprisingly less than the appendix, but if you need to have a C-section, you might just have them repossess the kid.

In everything that I’ve talked about so far, I haven’t even touched on how women of color are diminished even more than white women, and far more often accused of lying about their pain to seek drugs. I haven’t even begun on how the gender gap is more like a gender abyss when it comes to the trans population, or non–feminine presenting people. I haven’t been able to start at the very bottom and look at how even booking an appointment with a specialist for any women’s issue is often a wait of six months, and a drive of a hundred miles, and I’m not talking about in a rural area or a developing country. I’m talking about the east coast of America. If I was to truly put everything out on the table, this article would become a novel.

Last year, I had a cancer scare when I found a mass in my neck. I went to several doctors who told me there was nothing there, till finally one did a proper exam. I walked home that day with a lot on my mind, but the main thing I remember was the extreme relief. Someone had just told me I might have cancer, but being believed felt stronger than the fear. Scans were done, I was fine. I’ve spent a lot of time telling sad stories, but in writing this article two things give me hope. The first was how easy it was to find sources for this article. The gender gap is no longer a myth or conspiracy theory that needs to be proven, it’s a well-known fact, and I am a big proponent of the concept that the first step to solving a problem is admitting there is one. The second is, oddly, that friendsgiving again. While all the stories we heard were depressing, the only reason a lot of my friends were around to tell those stories is because there was someone that broke the chain – a good doctor, nurse, technician or psychiatrist who did their job. I am a medical staffer myself and something I’ve learned, being in the industry, is that when people go to the doctor they are often at their most vulnerable. They don’t know what is going on, they feel terrible, and all they want is for someone to be on their side. I’ve seen providers I work with take that panic seriously and the patient seemed to start feeling better as soon as they said the words “I understand. Let’s see what we can do.”

28

“

t he D ismissal of Women ’ s concerns in me D icine is so common it has its oW n term : me D ical gaslighting ”

29

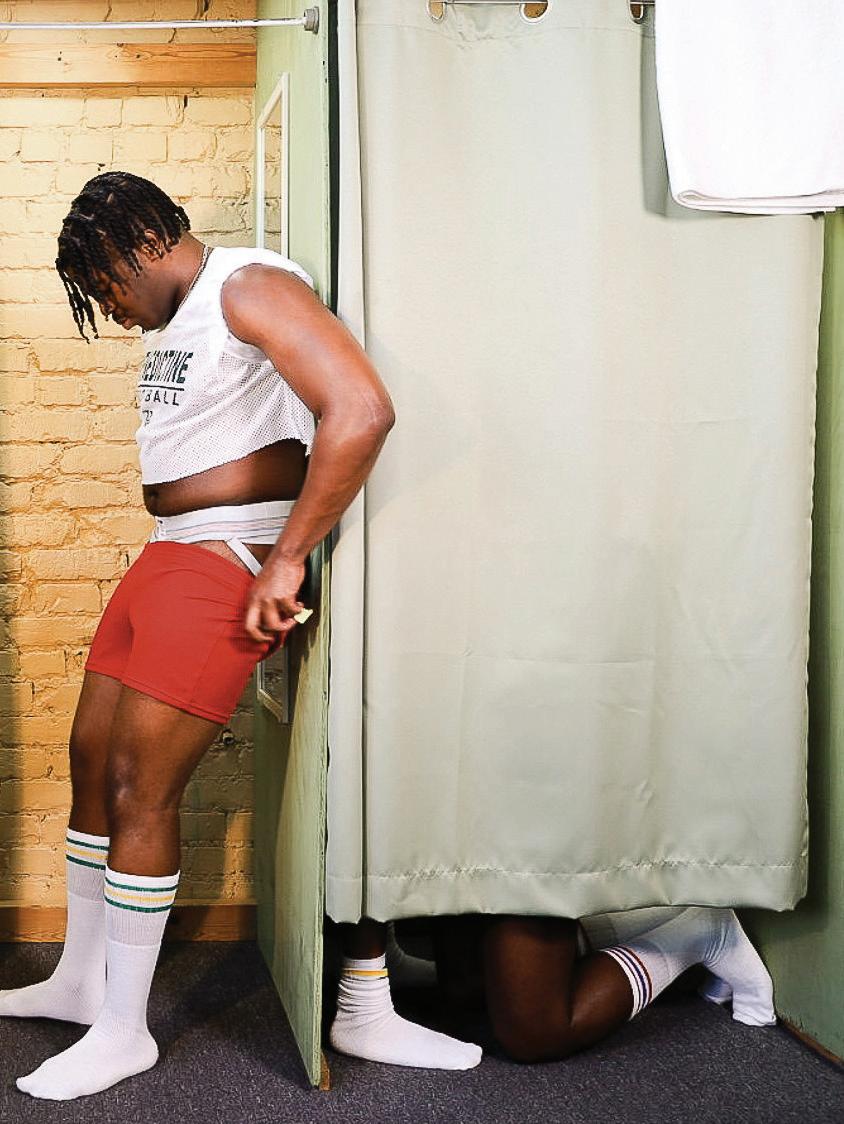

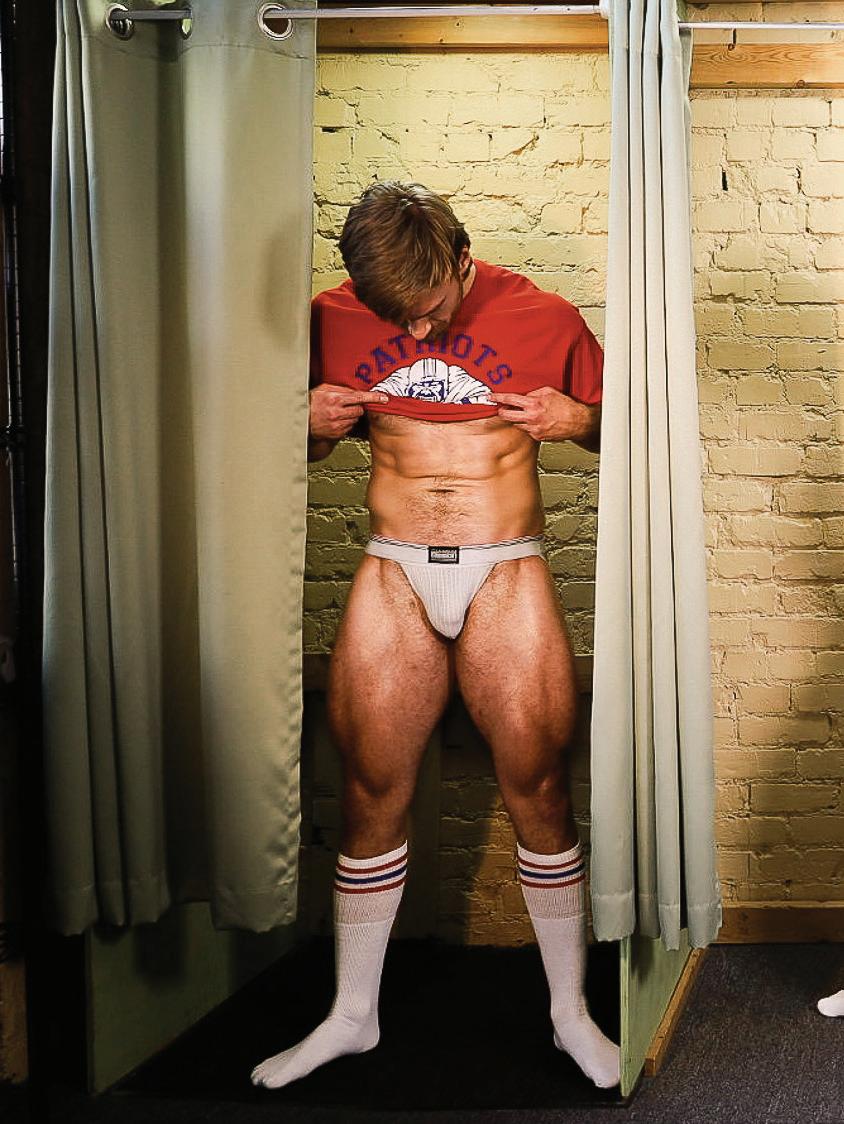

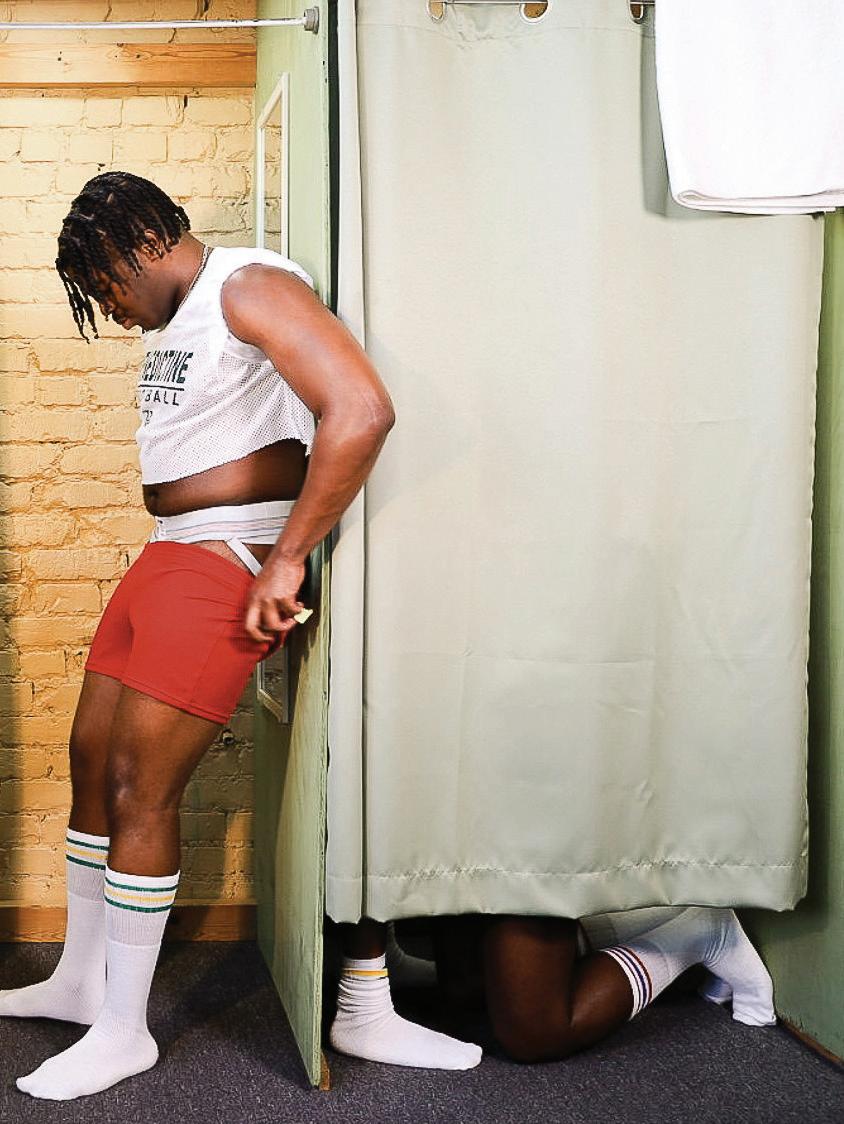

STUD

CreativeDirector:CalebGoss

Photographer:SelahPennington

Stylists:SydneyFolsom,HopeOllivant,CalebGoss

LightingAssistants:AmynaDawson,KobiMcCray

Models:JacobSimmons,RonnieOlugbemi,OscarConcia,BenClark,JadenAlbuquerque

Writtenby:LareinaAllred Illustrationby:MartyAlexeenko

Writtenby:LareinaAllred Illustrationby:MartyAlexeenko

When I inevitably try and get a real, adult job with real, adult people, I’ll probably regret having my legal name attached to the fact that I used to write Star Wars fan fiction. From this moment on, my sordid internet history will be immortalized in print and forever aired out for the shame of my parents. Now let’s talk about smut.

I’m the kind of person who covers their eyes when people so much as kiss on-screen. I handle sex scenes in movies with all the grace of a 10-year-old boy who just discovered cooties. Sucking face? Disgusting. Someone takes off their clothes? Pack it in boys, the show’s over. It’s always awkward and weird. Contrary to popular belief, I don’t want to see Megan Fox’s cleavage. I want to see her loved and respected with a stable income! I have no interest in seeing a famous actor nude. They are like naked mole rats to me, sexless and vaguely disorienting. Watching them rut against each other in skin-colored underwear is no more arousing than watching paint dry.

The rare feats of film that actually get intimacy right — “Normal People” and “Fellow Travelers” come to mind — are usually helmed by women and queer people. These shows understand what mainstream Hollywood is seemingly incapable of grasping: that intimacy goes beyond the physical. Sex is never truly about sex. It is about vulnerability and pain. And yes, about being unapologetically horny. But even as some executive producers are actually listening to their fan bases, others still think women should shave their armpits during a zombie apocalypse, I can always count on fan fiction.

It’s no coincidence that the filthiest, gayest erotica is often written about straight-laced white men. The Omegaverse was invented by J2 shippers in the Supernatural fandom, and one of the most popular fan pairings in Tumblr’s “smol bean” heyday was BBC’s Sherlock Holmes and John Watson. If everything in those sentences was straight-up word salad to you, consider yourself blessed. Now consider yourself cursed, because I’m going to explain everything about online fan culture in agonizing detail.

Since the beginning of time, homo sapiens have needed to reproduce. The urge to stick d*cks in things has been the driving force of our species’ success, so it’s no surprise that most of our songs, shows, and advertisements include a lot of half-naked people. However, the artlessness of traditional pornography has made it pretty clear I’m not its target audience. Seeing an endless stream of beautiful, waxed women being penetrated by men, who probably don’t know how to wash their asses, is upsetting to me and my homegirls.

You might be throwing in the proverbial towel now. If women and queer people don’t want to watch onedimensional sex dolls of themselves be thrown around on porn websites, what do they want? It’s impossible! You give up! But fear not. To get a true glimpse into the desires of the minority, you only have to visit one place: Archive of Our Own.

Think of the Library of Alexandria, the Library of Congress and the library of… something. I’m running out of culturally significant libraries, but just imagine them all combined under a single website. Only instead of the writings of Socrates or the poetry of Sapphos, this library — affectionately referred to as “Ao3” — holds millions of fanworks on everything from “Dragon Ball Z” to “World of Warcraft”: thousands of nerd franchises that, to the untrained eye, may seem like breeding grounds for incels and unwashed nerdo-freakazoids. Dive deeper under the surface, however, and you’ll find a staggering amount of women who want to f*ck Darth Vader.

Way back in the age of the dinosaurs, our forebears had to mimeograph their “Star Trek” fan fiction, print it out on actual paper, and give it out at conventions. These devoted ancients were born into the age of copyright, after authors started suing people who copied their plots. This shadowy, underground network of fan authors compiled binders of fics, self-organized to edit each other’s works, and crowdsourced funding to offset the costs of publishing. They were also usually, overwhelming, women.

When the internet sprung into existence, it became a well of resources. The early 2000s saw a boom in the number of fan sites and forums, some tiny and dedicated to only a specific “ship” and others that eventually indexed millions of works from every genre. The juggernauts of today — think Wattpad, Tumblr, and of course, Ao3 — all have their own individual flavor. Now, with the days of needing to print and collate Kirk/Spock porn being in the past, you can find any imaginable fanwork with the quick press of a button. The berth of material available, free of charge all day any day, is almost dizzying. Entire communities are centered around supporting one another in fandoms; sending each other compliments and reviews, writing personalized fan fiction for friends, and forming real friendships in the cyber-marketplace of ideas.

When I was twelve, my parents took my iPod away. Bereft of my usual sources of emotional comfort, I bypassed the restriction system on my school Chromebook, searched my favorite writers usernames by memory, and individually copied novels worth of fan fiction into my Google Drive. You have no idea how horny a teenage girl can be. When refused all other avenues of exploring her sexuality in a fulfilling way, she’ll either repress her feelings so hard she collapses into an actual black hole… or she’ll read yaoi. The latter is the more common scenario.

Every female friend I’ve ever had has read some kind of fan fiction. Even if they barely visit their old Wattpad accounts, or are one of those freaks who buy Colleen Hoover books, if you walk up to a girl between the ages of 15-25 and ask them if they’ve ever read smut, the answer is almost always “Yeah, obviously.” Its ubiquity is almost as impressive as the fact that no one really talks about it. I would love to publicly declare I read romance novels about Captain America without fear of social malign, but unfortunately we, as a society, still have a long way to go.

37 INK

Most of my male friends — the heterosexual ones, obviously — tend to regard fan fiction with the wariness of a toddler approaching a skittish horse. They know nothing about it, and their ignorance is almost as cute as their fear. But if they actually want to know how to please their girlfriends — many of whom I know, and most of whom I pity — they already have a wealth of advice at their fingertips.

For too long, we have had to accept men being objectively terrible at sex. It’s a rite of passage for every pervy male comedian to make jokes about not being able to “find” the clitoris, that elusive beast! Too many of my friends have told me about losing their virginities with a grimace on their face, and it’s a rite of passage for every pervy male comedian to make jokes about not being able to “find” the clitoris, that elusive beast!

The world has done a p*ss-poor job of teaching men how to prioritize other people’s desires. I don’t know about you, but the last thing I want to do is teach some 23-year-old Chad with a business degree and inferiority complex, how to touch a woman without driving her to celibacy. I’d rather just sit in my own bed eating Oreos, reading fan fiction about Boba Fett. The Boba Fett of my dreams doesn’t need to be taught how to kiss. He can read my mind and automatically know all of my deepest desires. His hands are the size of baseball mitts. He rips open my proverbial bodice and ravishes me with all the force of a man who allows himself to cry and does not harbor resentment towards his mother!

I guess guys’ version of reading fan fiction is just watching women’s boobs bounce in video games while they shoot at each other and yell slurs. Or giving themselves porn addictions and joining incel forums. (Side note, I love men! I have many male friends! My boyfriend is even a guy! #Ally.)

Anyways, a lot of men’s bafflement about the mysterious workings of the elusive, female mind could be solved if they actually paid attention to what we wanted. But we have become very good at hiding it. After all, it often feels too awkward to look someone in the eye and say “Can you love me, in a forceful way? I’ve lived my whole life being too ashamed to seek what I actually want. The world has convinced me that voicing my desire will make me somehow disgusting and worthless; someone fallen and cheap. The power of my own sexuality is too scary to confront, so I can’t even let myself enjoy intimacy without feeling inherently corrupted. Growing up religious really did a number on me. By the way, do you have genital herpes?”

That’s way too much emotional baggage to unpack during one mediocre Tinder date. It is, however, perfect fodder for every Ao3 author who writes novels’ worth of smut about Naruto characters!

In between the gaps of everyday life — which is often humdrum and disappointing — fan fiction offers a place to feel valued in your own desire. It celebrates what queer and female-led spaces actually enjoy, instead of what the world has continually told us we should just roll over and endure. It indulges in the deepest forms of fantasy. It explores heartache and pain and love. It builds community.

The backbone of modern culture is not Zach Snyder or Quentin Tarantino. It is teenage girls, 50-year-old divorcees and gay furries who spend hours upon hours blogging, writing and thirsting. Fan-edited trailers for movies can rack up millions of views. One of the most read fan fictions in Ao3 history is a gay romance between Dream (yes, the Minecraft streamer guy) and GeorgeNotFound (another Minecraft streamer guy). Hundreds of thousands of people post every day, multiple times a day, providing content for other fans free of charge for no other reason than that they really love video games, anime and Star Wars.

I’m not going to pretend that every piece of smut deserves a Pulitzer prize. There is some veritable garbage out there, chock-full of bad descriptions of “quivering members,” lots of damp body parts, and “quivering thighs.” There’s usually a lot of quivering. But for every cringe-filled penis analogy, there’s also fanwork that reads better than most published books. You have to take the cringe alongside the literature, allowing it as simple evidence of people just trying to have a good time. No profit margins, no camera crews, no million-dollar budgets. Just regular people who are earnest, creative and mind-bogglingly horny.

You’d be surprised how much you can learn about the world once you read about what real people want — and once you learn what you want. Live, laugh, love, and be free! Read extremely explicit Star Wars smut! Write a novel’s worth of erotica about comic book characters! Or just be content with the knowledge that all of this is out there for you, if and when you want to take a look. Millions of people have found joy doing what they love, by writing about doing who they love. It’s time for you to do the same. After all, the deepest desires of humanity have stayed the same throughout time. What do we all yearn for? Love. Affection. Acceptance. To be known as we are and still valued for it. To imagine that someone out there sees us, really, truly sees us. To be gently cherished. And also to be finger-blasted by Ghost from “Call of Duty.” When refused these joys, the maligned of the world must dream their own dreams. Then, in comes the fan fiction.

It’s too late now to hold onto any semblance of shame. I’ve probably already ruined any chances I ever had of landing a government job by writing this article, so I’ll say it loudly and proudly, open as I am with you now as my true bosom friends: I WANT TO F*CK BOBA FETT!

feed me

Creative Director and Stylist: Kayana Jacobs Photographer: Isaiah Mamo Lighting Assistant: Lydia Behler Model: Taylor Gayot Makeup Artist: Taylor Gayot

THE BACK

CreativeDirector&Photographer:AmynaDawson Models:KeelyBuchanan&KaylaHollingsworth

CreativeDirector&Photographer:AmynaDawson Models:KeelyBuchanan&KaylaHollingsworth

BACK SEAT

Stylist:SuongHan LightingAssistants:SelahPennington&KobiMcCray

Stylist:SuongHan LightingAssistants:SelahPennington&KobiMcCray

46

T his Bed Is No Longer Yours

47

Creative Director, Photographer and Makeup Artist: Julie Dinh Stylist: Beaux Reeder Bijoux Lighting Assistant: Chloe Johnson

Models: Syton Nontong, Mikayla Turner, Julianna Garcia, Yve Ho, Abdou Sanda, Grace Nambo, Grace Nguyen

Where is there to go but to be their home

What sheet do you grab when it’s not held by her

Who

When

else but you to be left of his crumbs you still feed on

the bed that once rocks you, now rocks them feed on

Staff Photos 4-5; Trans//Sexuality 6-9; Nymph 10-13; But I’m A Lesbian 14-17; Girl Rap 18-20; Mad Lib 21; On The Line 22-25; Don’t Worry 26-29; STUD 30-35; I Want to F*ck Boba Fett 36-39

Staff Photos 4-5; Trans//Sexuality 6-9; Nymph 10-13; But I’m A Lesbian 14-17; Girl Rap 18-20; Mad Lib 21; On The Line 22-25; Don’t Worry 26-29; STUD 30-35; I Want to F*ck Boba Fett 36-39

Written by: TC Priest

Illustration by: Isabelle Samay

Written by: TC Priest

Illustration by: Isabelle Samay

girl rap

Written by: Zoya Javaid

girl rap

Written by: Zoya Javaid

Written by: Monisha Mukherjee

Written by: Monisha Mukherjee

Writtenby:LareinaAllred Illustrationby:MartyAlexeenko

Writtenby:LareinaAllred Illustrationby:MartyAlexeenko

CreativeDirector&Photographer:AmynaDawson Models:KeelyBuchanan&KaylaHollingsworth

CreativeDirector&Photographer:AmynaDawson Models:KeelyBuchanan&KaylaHollingsworth

Stylist:SuongHan LightingAssistants:SelahPennington&KobiMcCray

Stylist:SuongHan LightingAssistants:SelahPennington&KobiMcCray