11 minute read

The Cloneycavan Man by Nick Siviter

The Clonycavan Man

Nick Siviter

Finnley hates the priest who is fucking his wife. He reviles the way his dark habits ride upon his towering and bony shoulders to his wife and describes in sickened detail the sunken hawkish look of the priest which churns his stomach. Finnley loves his wife, who is fucking the priest. He loves her for the skill of her hands, woven into woolen garments that are soft like a goose’s down, and the way those clothes accent the healthy curve of her figure. He often flatters his wife with praise of her skin, which is smooth, pale, and delicate like the contouring feathers of a swan’s belly. Finnley adores the forest which he is now hiking through. He often writes short amateurish verses extolling the forest’s lush greens, its swirling footpaths and bright clearings. He describes the invigoration he feels when the earthy aroma of mossy boulders fills his head and the nectar of the morning dew glosses his feet. Because Finnley loves his wife he is traversing the forest, carrying a ponderous burden, a large shoulder-slung package. And because he loves the forest he traverses it steadily, and because his pace is steady he nears his destination: a forgotten, overgrown mausoleum.

Twenty-seven years ago Finnley built a small cottage by hand in the new village of Crathie. The village had grown around a rotten little monastery, which still squats atop a wide hillock. Outside the village the sweeping grass is pierced by an eruption of brilliant white stone. The fang of stone is pearly, as if freshly washed, and when the sun shines it’s brilliance becomes blinding. When a storm gathers it bites into the dark, juicy meat of clouds. The trees of the forest block any view of the fang, but Finnley is familiar with the forests, and is rarely lost.

Twenty-five years ago while buying a new set of stockings, Finnley had met Cliodhna and she had shone in the light of day. During the nights, in the soupy warmth of peat-fueled fire, the light flickered over her freckles and the smoke clung to their sweat. In the mornings he walked in God’s forest with the healthy stride of a young man, and in the early light found the mausoleum sitting low to the ground.

Avery Eckert

Finnley feels the weight of the package over his shoulder, he thinks about the mausoleum and feels apprehensive, feels scared. He has never entered it, but the entrance is clear of rubble, and at times Finnley feels drawn to it. The village of Crathie is northern, yet the summers are boggy, and on the hottest days his cottage steams him. On days like those, Finnley imagines it must be quite cool and pleasant in the moist bowels of the old structure, in fact he finds its damp entrance quite inviting, attractive even. But he remains repulsed by the remains which lay entombed beneath it.

Thirteen years ago, in the monastery, a lanky young priest gave a sermon. For the first time, Father Deaglan stood at the pulpit of a chapel, newly built by the hands of the village. Now Finnley is standing before the mausoleum, built by hands long dead. His path through the forest wound in overgrown curves and the uneven ground jostled the package on his shoulders. His aged legs are stiff and his arms are burning, so he sets the package down in the living grass. There is a familiarity to the stonework of the mausoleum. The weight of the cyclopean construction is still apparent to him, twenty-five years of age passed over the granite like a breeze.

Finnley takes a moment, and a deep breath. On the air is a faint smell of bog coming from the area past the mausoleum. The earthy smell of peat makes him think of his wife, of cold nights spent in the cottage. On the ground is the package at rest, but in his mind thoughts are racing, he thinks of the priest and his skin crawls. In the vestry a man who isn’t Finnley once caught Father Deaglan and Cliodhna having a go at each other. He thinks of what the priest had done to him, and he thinks of what he has done to the priest. Finnley doesn’t like thinking about it, because he considers himself a pious man. He also considered the priest a pious man. Finnley feels sick when he thinks of his wife, but he does not blame her. He doesn’t like thinking of it, because he considered her a faithful woman. The holy man and his habits broke that faith, and the rules of their own. If Father Deaglan can break the rules Finnley decides so can he.

So he braces himself and hoists the oblong package once again. The mausoleum is dark inside. Even feet past the entrance Finnley can barely see his own rough hands, but he can feel the clammy walls around him and slowly makes his way deeper. The flagstones of the floor are cracked by thirsty roots which make his pace unsteady. And from the ceiling vines hang and tickle his weathered face as if they’re trying to tempt him deeper. The light of the day continues to fade. A treacherous set of stairs leads him further down into the earth with slippery and uneven steps. At the bottom the narrow hall opens into

a larger room where the rank moist air makes Finnley hack and cough hard enough to drop the package. Its weight falls to the ground with a dull thud and a wet smack and he leans against the wall to catch his breath.

Finnley is conflicted. In one thought he respects priests because they are holy men and educate his village on the words of God. They do important moral service and Finnley loves God and all his creations. In another thought he feels betrayed and confused. Finnley weighs the thoughts, like two jagged fragments of flint, they poke into his most sensitive areas. His emotions, his honor, his masculinity, his pride, anger, jealousy, resentment, regret, rustling—the package is wiggling against his foot—shock. Fear. Finnley’s breath is gone again and his chest feels like a boulder is sitting on it. Quickly he runs his hands over the uneven wall and the broken floor until he finds a loosened chunk of granite. Pressing his knee into the midsection of the package to hold it still, he puts the rest of his weight into one unwieldy bludgeon to the top of it. The force takes him to the floor and as he lays across the once again stilled cargo he gasps and wheezes for breath. His face is burning and he still feels lightheaded, regardless he shakily stands and weakly pulls the package out into the room. Further into the room the air only grows sourer and denser. A short distance in is enough for Finnley, in the darkness the package felt as hidden as it would eb beneath heavy earth.

Finnley exhales. His body relaxes. But he can’t put his mind to rest, he needs to leave. So he carefully feels his way back retracing his steps to the wall. Which he now allows himself to feel in detail. It feels like a river stone in winter and Finnley finds the contact quickly growing uncomfortable as if the rock is trying to suck the life out of his own body. Finnley’s heart speeds up again, pounding a tight wad into his throat and hurrying him down the corridor and up the stairs. He doesn’t breathe or swallow properly until he emerges into the hot afternoon sun. Then he breathes deeply, relishing the warmth of life and tries to savor the songs of chaffinches and coal tits around, but their song is saccharine and makes his head hurt. The smell of bog is stronger, and more acrid now, has the wind changed? It’ll only get stronger, from here Finnley will need to traverse the bog for the shortest route back to Crathie, where he desperately wants to return.

A cool breeze licks Finnley’s back, sending a shiver through his body and sending him stumbling past the mausoleum. The direct sunlight is brutal compared to the clammy feeling of the mausoleum and Finnley is forced to squint while the heat beats down on him. The path towards the bog from the mausoleum is not one often traveled, and so the reassuring footpaths are absent.

But Finnley, with his knowledge of the forests is confident. His feet move by their own will, stepping over rocks and roots and ditches, wandering towards the edge of the bog while his mind wanders to its own destinations.

Finnley knows he can’t go to church anymore, He’s committed a mortal sin and his guilt is too great to bear entry a chapel. He doesn’t think himself to be a hypocrite. There’s too much noise in his head for him to form a coherent plan, but he decides that his life will never be quite the same. Deep in thought, he almost steps directly into the fetid maggot-filled remains of a hare. The stinking writhing meat repulses Finnley and he stumbles backwards onto the peaty soil, scrambling to distance himself from the foul scrambled matter in front of him. His brain is fried, scramble from the shock, and at this distance the smell curdles his stomach and makes him gag. He hunches over the forest floor, drool spilling from his mouth and heat growing in his throat, but he manages to choke it back and pinches his nose, taking care to move around the pile of decay.

How long would it take, he wonders to himself? The body he left in the mausoleum, one day, would look like this wouldn’t it? If some poor unfortunate soul stumbled upon the mausoleum in, say, the next month, what would they find? Would it be a soaked bag full of maggots and a clean skeleton? Or a pile of slippery flesh? Or just a malformed corpse, bloated from gaseous rot. Finnley pushes onward, sickened and unable to clear himself of decay.

Finnley walks, and the smell of peat does not grow. Finlley’s worry grows. There should be a heavy smell of peat encompassing him by now, but the scent is as faint as it had been. He stops and turns around a few times, trying with growing worry to get his bearings in the forest. Finnley is struck hard by a realization: The forest is all trees. He’s surrounded by trees and they all look the same. Why had he never noticed? And how had he ever found his way before. The smell of peat is still as faint as eve and without a footpath there’s no direction for him. Finnley looks to the sun, keeping in mind that the bog lies west of his starting point, only to find that a thick layer of cloud lies across the sky. The diffuse glow provides no clue as to direction. So he chooses a direction, he turns right from where he is and walks.

He walks until his feet hurt and until he can’t stand to see a single rotten stump or toadstool poking out of the soil. He stops walking when the sky grows dark. Time has stretched out indeterminably for Finnley, and the possibilities of an approaching storm and an approaching night seem to be equally possible to him. The Idea of traversing the forest at night brings a sour tang to Finnley’s

mouth and makes him swallow uncomfortably and brisken his pace in a new direction. The humid heat is growing and bathing him in slick sweat.

This time the smell of peat grows, it is sour and earthy, but not comforting like it once was. It smells like home, somewhere he can no longer feel comfortable, and heat, which is making him uncomfortable. When night falls the heat will go, but the darkness will bring his walking to a standstill, tripping him with invisible roots and rocks.

By the time Finnley reaches the edge of the bog His clothes are damp, his feet are sore, his legs are shaking. The smell of peat is dizzying, his feet sink into the wet loam of the bog proper.

The bog was once a comforting place, full of life and movement, the smell of peat would fuel Finnley on his way home. Now the bog is disgusting to Finnley. It’s dead still and the sun is eclipsed by opaque rolls of cloud, making the rough, bristly undergrowth blend into the ground and catch at Finnley’s trousers. The smell reminds him of the decay that peat is born from, the acidic scent burns through his throat and makes him tear up. His vision blurs and smears the bog into a soup of browns and greens. The water sloshes in his ears while the birds mock his struggle from above. His senses melt together. The sucking mud pulls at his shoes and the wet air drips off his red, feverish skin. Tears run down his face and mix with the runnings from his nose. Finnley feels as though he’s liquefying into the putrefaction that he’s trudging through.

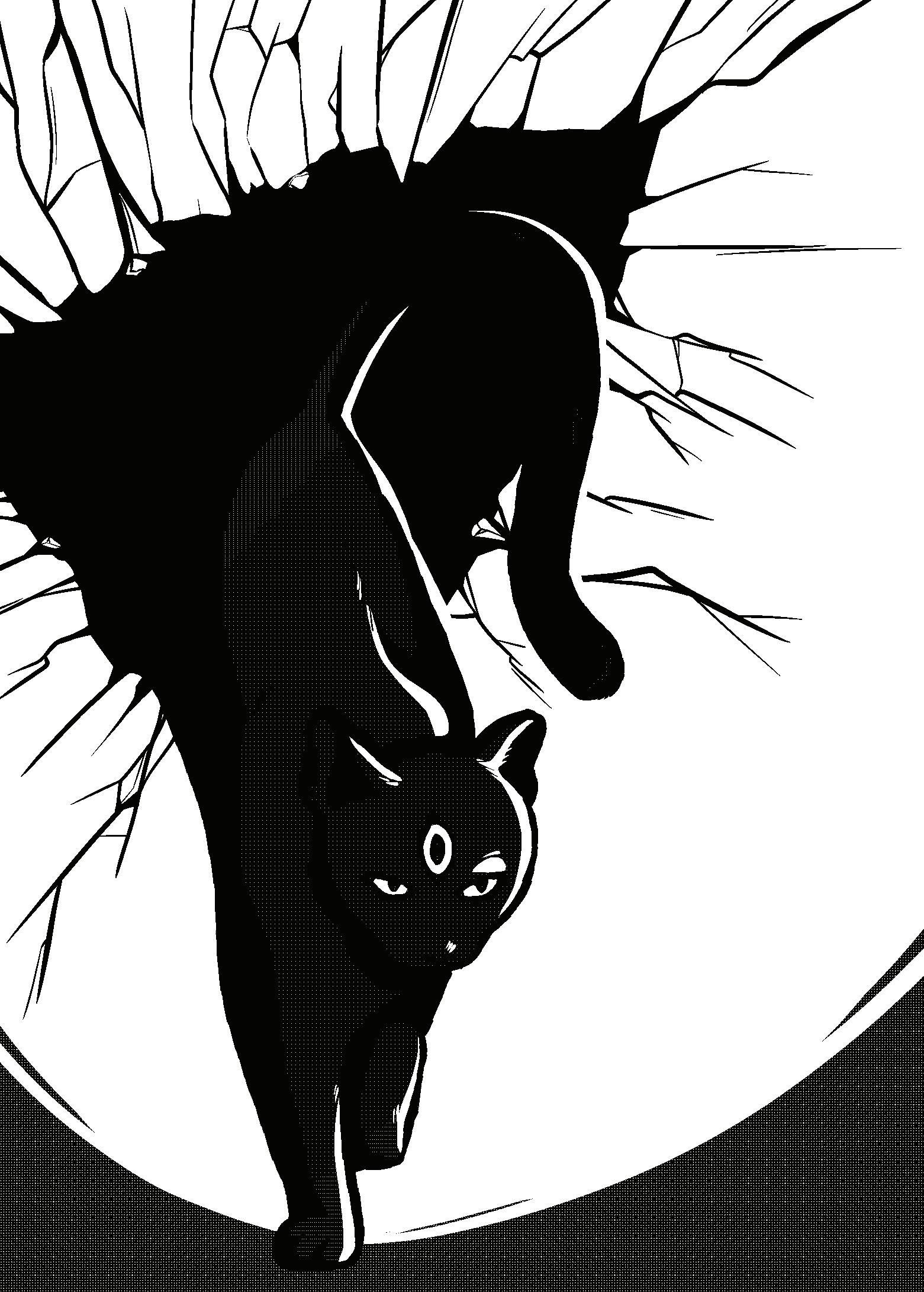

A root pulls his feet out from under him and he goes flying into the water of the bog. It’s hot and thick, full of dead vegetation and mud. Beneath him are roots which his feet become hooked in. His arms are weak from carrying the package and he can’t keep his head above water. So he sinks. The water at the bed of the bog is thicker, and much cooler, and it cradles him in loving arms.