5 minute read

The Things in the Woods by Jessica Soffian

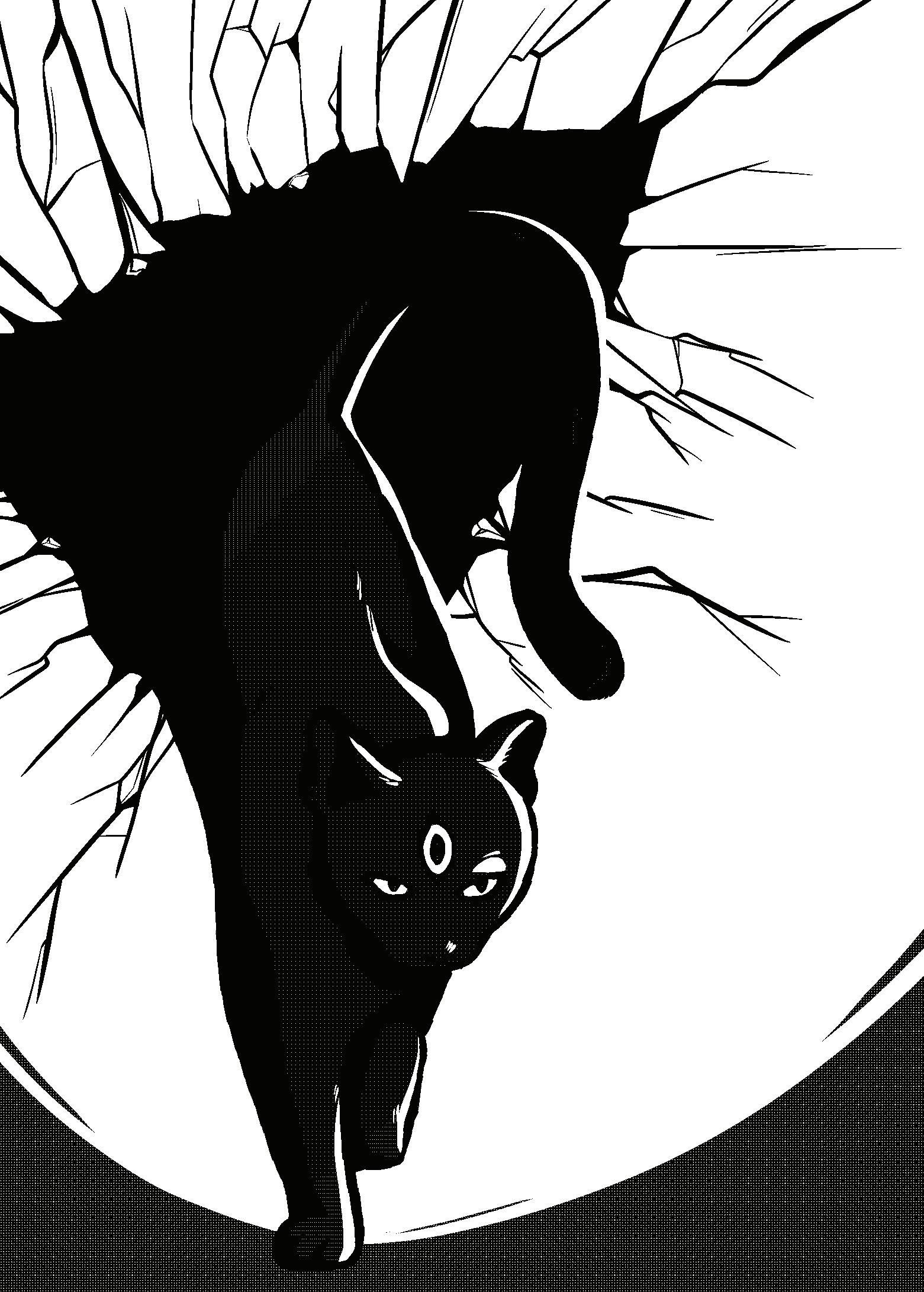

The Thing in the Woods

Jessica Soffian

You were only eleven the first time you saw the thing in the woods.

You were out with your father in the wintertime, shivering in your hand-medown coat and your soaked-through boots. You did not want to be there; you wanted to be at home by the fire, curled up at your mother’s side and lulled to sleep by the gentle sussarus of her voice. But fire needs wood to burn, and according to your father you were a man now, and you wanted to prove it. So, into the woods you went, into the snow and the looming shadows of fir trees. Your lungs ached from the cold of the air and the ax you carried was too heavy for you, but if you stopped moving forward you might lose sight of your father and the dark branches overhead looked almost like claws, so you kept trekking.

You were amusing yourself with composing songs under your breath—rambling ditties with little form or direction to them, but entertaining for your young mind—when your distraction caused you to miss the gnarled root that rose from the snow before you. Your boot caught on it and you tripped and fell facefirst. Now all of you was wet and cold, even your hands in the new mittens your mother had knitted you. You started to cry, but when you looked up to call out to your father he was no longer there.

But it was.

Your cries stopped mid-breath at the sight of it, just inches away, watching you with horrible eyes like bottomless pools, ageless and deep and aching to swallow you up. Everything was frozen in that moment—even the snowflakes seemed to have stilled in the air—as you stared at it. As it stared at you. Mist formed around its muzzle from the wheezing huff of its breathing, and you knew just looking at it—at the gruesome crown of jagged bone-knives reaching from skull to sky, at the armored feet just the right size to crush your hand into nothing inside your new mittens—this monster could kill you. Easily. And looking into those ancient eyes you knew that it wouldn’t even care.

Jessica Soffian

You willed yourself to reach for the ax where it had fallen, thinking desperately that perhaps you could at least scare it off, but you found you were paralyzed by sheer terror of the thing before you. You simply could not will yourself to move. You could barely breathe. You were certain, suddenly, that this is where you would die, eleven years old and soaked through and alone.

And then, miraculously, by grace of God or luck or some mercy of sheer indifference, it turned and walked away, leaving you shivering in the snowdrifts.

Later, your father did not believe you. Your mother smiled gently and patted your head, but you could tell she did not believe you either. She bundled you up in blankets and handed you warm cider and rubbed your frozen toes until the color returned to them. Your father put the new logs on the fire and sighed as he looked at you.

“I guess you’re not quite ready yet,” he said, rubbing his beard. “We’ll try again when you’re older.”

And you knew: you were not quite a man after all.

For years, you feared the woods. You refused to enter them alone, staying only on the outskirts and sneaking anxious glances into the mess of gnarled branches. The memory of it plagued you; every gust of wind was the horrible rasp of its breath, every dark branch moving on the outskirts of your vision was the tip of its bony crown. For years your sleep was restless, and you often woke up sobbing from fear of the dreadful beast you had seen. The specifics of the memory faded over time, leaving only the afterimage of terror, and you found yourself resenting your younger self for being so afraid of what you grew more and more certain was just an ordinary deer or an oddly-shaped tree. Eventually, you started to wonder if you hadn’t just made the whole thing up entirely; if you’d ever actually seen anything at all.

Until the second time.

You were seventeen then, older and more mature. Your voice had recently dropped several octaves and the acne on your chin had started to look more like stubble, and so you thought yourself a man. You went into the woods alone for the first time since the encounter to prove this manhood to yourself and to the world and to anyone who scoffed at you for your childish fears. You walked among the dark branches and looming firs, and the crunch of your boots in the snow and the pulse of your own breath seemed so loud to you, but you told

yourself you were not afraid.

And then you saw it again, there in the glade. Again, time froze, and it looked at you. It loomed before you and it was just as your nightmares recalled it: its eyes were black as depthless pools, just as you remembered, and just as you remembered its crown of bone stretched up and up, branching into sharp points, perfect for goring. Its legs were as you remembered them as well; long and knobby, too spindly to hold such a massive creature, and yet there it was, standing atop the snow which somehow did not give under its weight.

Alone in the forest, you looked at it: the thing from your nightmares, the thing that you knew in the pit of your stomach could so easily be your death. It wasn’t a deer like you’d hoped—you’d seen deer, and felt chills down your spine at their almost-resemblance—and this wasn’t that. Deer are slender and graceful; the fur on this thing hung off it like moss from trees, and its chest was thick and muscular like the trunk of some great oak. Deer were also docile creatures, skittish and easily frightened, but this thing—whatever it was—stood still and strong and stared you down without a hint of fear in its horrible, horrible eyes. There were stains of rust flaking away on the sharp points of its bone-crown and you knew: this thing had killed. As that thought came to you, the creature lifted its head up towards the grey sky and cried a high, haunting bugle, and the sound of it rose every hair on your body and chilled you down to the bone.

It looked at you, with those horrible eyes, and it finished its battle cry. And it took a step forward.

You were not a man, after all. You were the same little boy you’d been before, alone in the woods with this ghastly, wretched thing.

So you did the only thing you could do: you turned, and you ran.