ISSUE #12

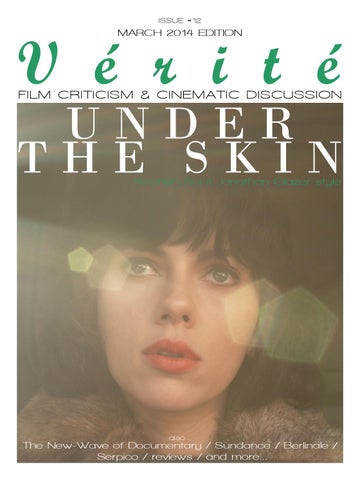

V é r i t é MARCH 2014 EDITION

FILM CRITICISM & CINEMATIC DISCUSSION

UNDER THE SKIN Scottish Sci-fi Jonathan Glazer style

also...

The New-Wave of Documentary / Sundance / Berlinale / Serpico / reviews / and more...

ISSUE #12

V é r i t é MARCH 2014 EDITION

FILM CRITICISM & CINEMATIC DISCUSSION

UNDER THE SKIN Scottish Sci-fi Jonathan Glazer style

also...

The New-Wave of Documentary / Sundance / Berlinale / Serpico / reviews / and more...