6 minute read

Imagine: Milo Trnovsky

Milo Trnovsky

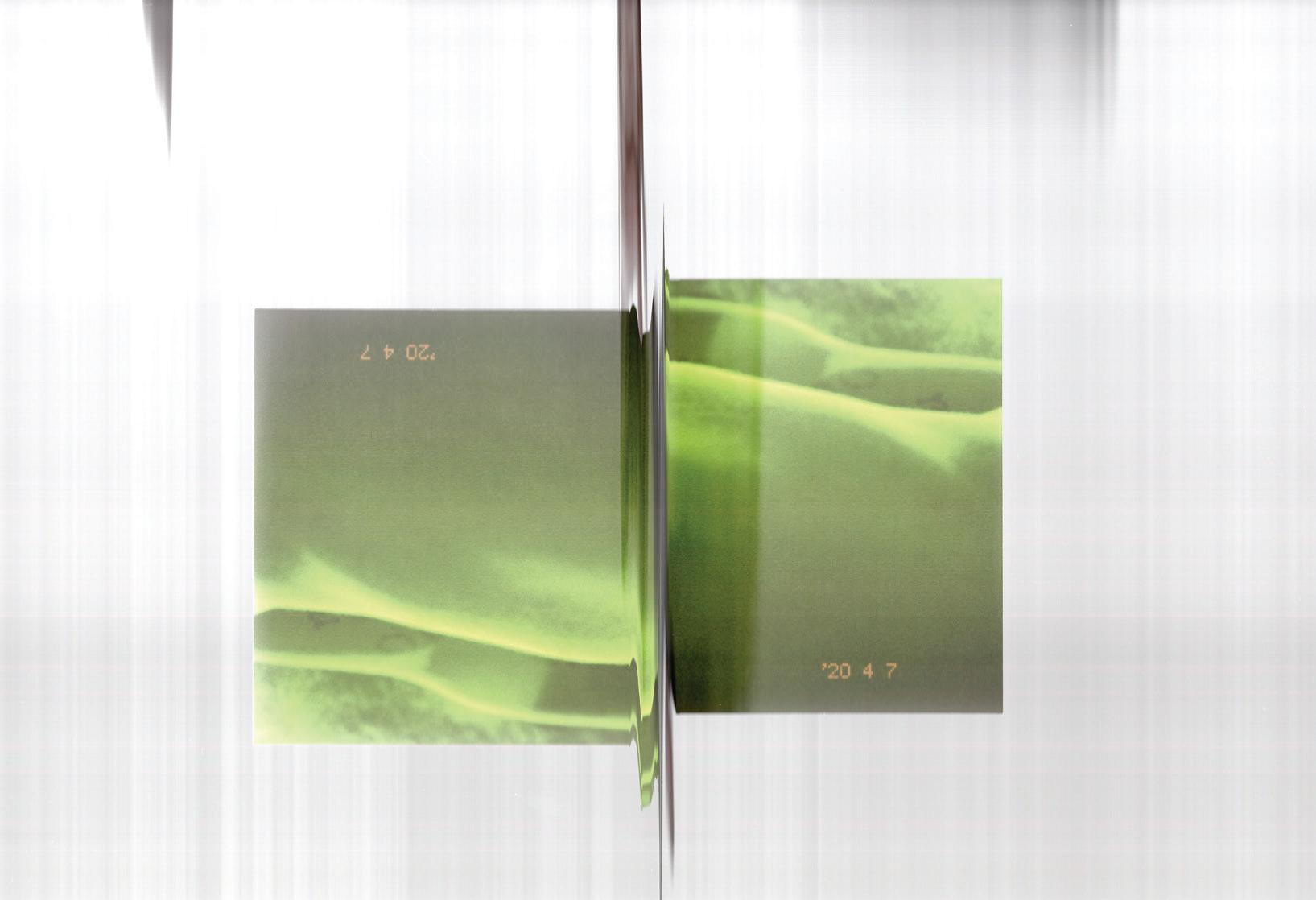

Interview Christina Massolino Right: “Fluid” 2017, blown glass with colour rod wraps, sold before measured

Milo Trnovsky is an artist currently studying a Bachelor of Art and Design (Honours) at UniSA. Preceding this, Milo worked predominantly with glass while studying a Bachelor of Visual Art at UniSA, which they graduated from in 2017. Milo draws a lot of inspiration from their own lived experience as queer and non-binary/gender diverse. They began engaging with themes of fluid movement and gender expression in 2015, when they first began experimenting with glass blowing, during a time that Milo says they were questioning their “identity on a daily basis.”

Milo spoke with Verse about how gender should be viewed more accurately as a spectrum, one that defies the common binary terms of ‘male/female’. Although society frequently deems this binary structure as the only acceptable option of gender identification, Milo believes that with an open mind, the willingness to learn and listen, everyone has the ability to understand their own gender identity and break-down existing norms. Thankfully for us, we have people like Milo who are itching to share their knowledge and experiences, not only through conversations and written communication but through their art as well.

You use they/them, he/him pronouns. Why do you use these pronouns, and how does it affect you when people acknowledge them and use them correctly?

I’ve never felt like a “girl”. When I was a kid, I made an effort to reject all assumptions of being a born female. I dressed as a tomboy, associated myself with boys and participated in activities deemed as only appropriate for boys at our age. I remember how much it felt like an insult to be called a girl, yet when I was questioned by my mum, I refused any possibility of being a boy. This persisted through high school, but started to fade away more as my body developed. I realise now that I suppressed any thoughts of being trans/gender diverse out of fear. Four years ago, I undertook a masterclass at Pilchuck Glass School and with tremendous help and support, I started using they/them pronouns and occasionally he/him pronouns. I also started to go by Milo, one of the names my parents contemplated if I were born male. It was hard to make it stick when I came back home, but now almost everyone sticks to my preferred name and pronouns. I guess the best way to explain what it feels like to be gendered correctly is by asking a question. If I were to come up to you, use the opposite pronoun and call you a different name would you get annoyed? Would you start to go red in the face, feel uncomfortable and want to speak up?

Before we started this interview, you sent me some links (e.g genderbread.org) to sources that make this knowledge accessible. Why do you think people find the existence of gender diversity so hard to comprehend, despite the lived experience of millions of people?

I think it stems from heavily biased education structures enforced by conservative governments across the globe. Our existence isn’t taught in schools and I don’t see it changing any time soon. This is a tough and extremely broad question, but I do strongly believe that our older generations have perpetuated the norm of turning a blind eye to atrocities in history that do not align with their ‘personal’ beliefs. I think if people in power continue to dismiss our existence as a myth or ‘just a phase’, ignore scientific studies and continue to silence those with a voice it will greatly stunt our future generations.

You created a series of beautiful, skilfully glass-blown vessels that expressed gender-fluidity in 2017. How do you find the art of glass blowing has enabled you to express gender related themes? What is it about the quality of glass that allows for this?

I began making these bowls in 2016 and ‘perfected’ my desired outcome in 2017. Through that period of time I was questioning my identity on a daily basis, and still am. I found that in the Hot Shop I could briefly escape my anxious mind and exist in a genderless body, surrounded by loud equipment, a roaring 1200 degree furnace and an overwhelming sense of freedom. I didn’t have much access to colours (glass colour can be quite expensive and I’d recently moved out of home) so I used what I could, giving me mystery colour combinations. Embracing the unknown outcome, I also utilised the fluidity and control molten glass has over your actions. One of the first lessons in glass is that you have to work with it, not against it. Once you’ve learnt to work with it then you can tell it what to do. I think this can be pretty similar to the body and mind. Using themes of fluidity and free movements along with technically sound forms, such as bowls and vases, I strove to portray the vessel as the body and the fluid colours as the identity within.

What direction is your art going in now? Are you still working with glass?

With everything that’s happened in the last couple of months I don’t see my aspirations of starting a glass career coming to fruition. Two years ago, I backed away from uni and the art scene, I developed GAD [General Anxiety Disorder] and shut myself off from a lot of people. This year I finally built up enough courage to go back to uni and blow glass, but that’s been ripped away from me since our studios got locked down. I haven’t felt this hopeless in a while.

To fill time, I’ve tried to pick up film photography again, I hope to distort ambiguous images of my body and overlay them until it is indistinguishable from the original. I’ve also recently started to teach myself how to render 3D figures and environments, and hope to incorporate my photography concepts to generate a moving image.

The arts community typically has a reputation of ‘freethinkers’ and being on the forefront of understanding and expressing challenging ideas. Have you found people within the arts community to be accepting and supportive of you, or have you still faced some significant challenges?

Regardless of what community you’re a part of you’ll always come across people who hate you for no logical reason. Although the art community wants to be perceived as a group that doesn’t discriminate, they still do in almost every aspect. This is quite evident when you look at the lack of presence of gender diverse, queer, and POC identities within our overall art scene. The biggest issue I’ve come across is light bullying, misgendering and deadnaming but I’ve come to expect that in my life, if I don’t, I’ll keep getting hurt. But of course, the majority of people are really nice and just normal.

Who are some of your biggest art inspirations, both locally and globally?

I struggle to pinpoint inspiration to my own work because I think I draw a lot of my ideas from my own lived experience, people and interactions around me. I’m not sure if I could categorise artists I like as direct inspiration but I do admire the work of Tasmanian artist Dexter Rosengrave and their concepts of destruction and disintegration of the self. I’m also very interested in Liesl Schubel, a Canadian born artist, particularly ‘Copy Machine Collages, 2015’ and ‘Facade (We Have Always Been Collapsing), 2013’. I very much relate to aspects of their bio on their website. Reading literature such as ‘Trans erasure, trans visibility: History, archives and art’ by Archie Barry and ‘Breaking Ground on a Theory of Transgender Architecture’ by Lucas Cassidy Crawford has informed my ways of approaching making differently.

How can people support trans/gender diverse people within the arts?

The best way is to buy their work, share it and give them due credit without fetishizing their identity as ‘unique’ or ‘quirky’. Treat us just like any other artist you’d find in a gallery. ☐