To a Western Home Norwegian Immigrants on Their Way to Becoming American

by Ann Marie Legreid, Ph.D.No immigrant group in America has lived and thrived in a vacuum, segregated from other ethnicities. Each has faced prejudice and challenge, debacles on the border, and documented versus undocumented issues. Each has transplanted elements of home cultures in America while adapting and acculturating in a dynamic transnational environment. . . .That is the immigrant story.

People in front of a farm building in Årdal, Sogn, Norway. Ole and Peter Peterson Collection, Vesterheim Archives.Agriculture in nineteenth-century Hardanger, western Norway, was a many-faceted effort— labor-intensive and intimately tied to the mountain and fjord environments. Acres of bare rock and thin, stony soils were the prime mitigating factors against agricultural development. Farmers struggled. Farms were skimpy, some hung on steep slopes, and many fields had to be cleared laboriously of stones before cultivation. The valley bottoms provided the best sites for cropping, especially of barley and rye, but the acreage was small and marine west-coast climatic conditions were seldom favorable. Animal husbandry was a primary pursuit, a few sheep and cattle, a labor-craving industry with limited returns.

A subsistence economy meant the combination of several marginal niches. Some received supplemental earnings and food for the dinner table by joining the annual fishing expeditions in the North Sea, but there were lean years when the herring did not appear. The reindeer hunt was important to the economies of farms bordering the “vidda,” or Hardanger plateau, and mountain and fjord fishing rights were free for all, yielding mountain trout and salmon. Most farms cultivated potatoes and some tended strawberries and orchards of apples.

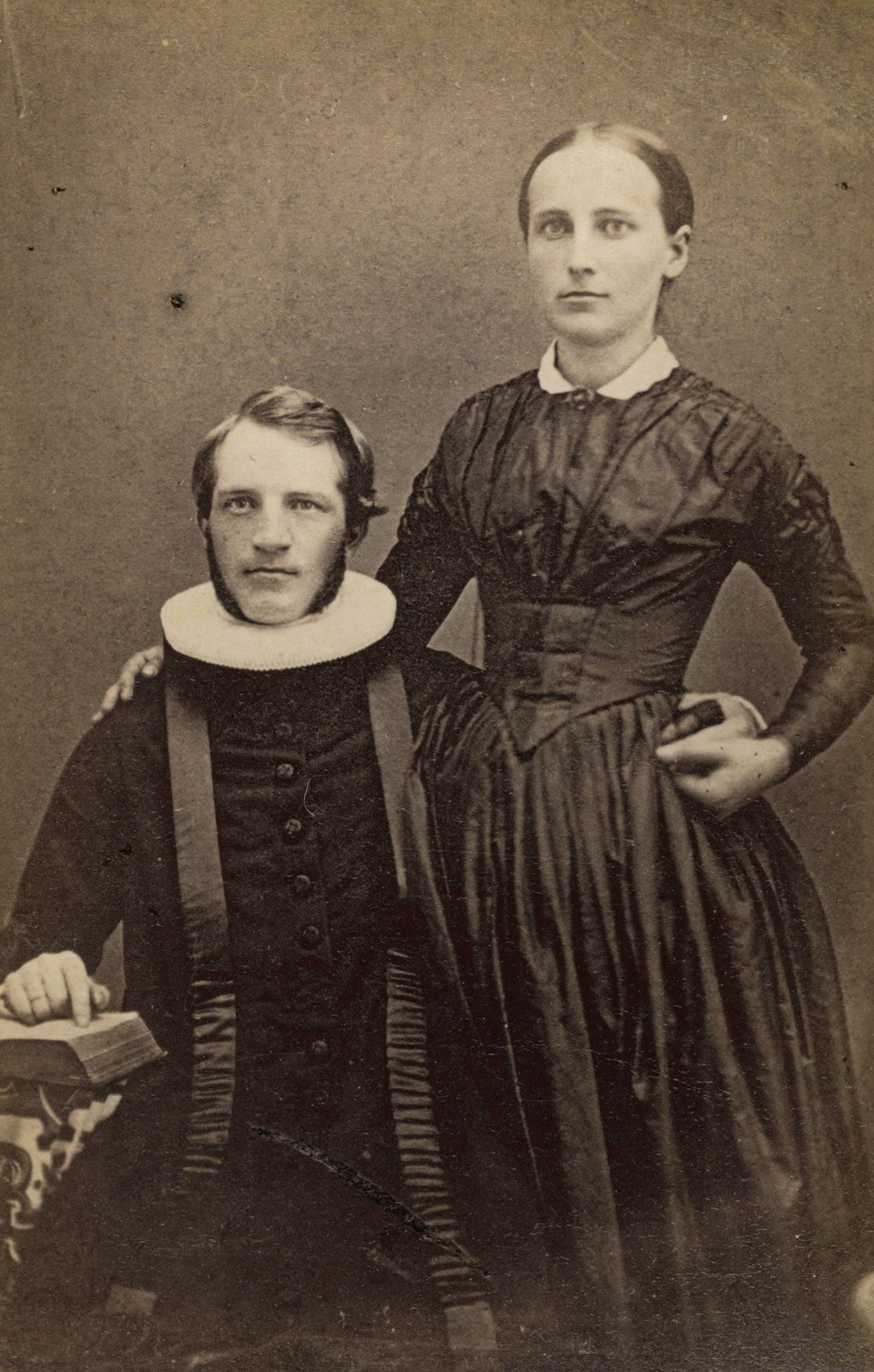

The farm territory was a social as well as an economic unit, the maintenance of which was the concern of all farm residents, including the nuclear household/farm owner, cotters, lodgers, and hired hands. Land was the foundation of social prestige and marriage alliances were formed with an eye to maintaining or expanding property holdings. In the face of daunting physical conditions, the residents lived in a close-knit world based on kinship and neighborly collaboration.

The smallest form of neighborhood association was known as the grannelag, which consisted of the closest neighbors, and probably did not extend beyond the boundaries of the main farm and its cotter units. Members of the grannelag came together to assist on occasions when family could not manage alone as, for example, during the birth of a child or in advance of a funeral. A larger association, composed of persons outside of the immediate farm territory, who came only upon invitation, was the bedlag. These associations were best represented at important entertainments and feasts, such as weddings and burials. When work projects arose, the bedlag was more properly called the dugnad, which varied in size and composition according to the nature of the task at hand. The daily exchange of neighborly help, or bytesarbeid, had a much looser foundation and generally hinged upon familial ties, friendship, or a casual agreement between neighbors.

When hardship presented itself, it was customary for neighboring communities to share the burden, offering aid in the form of potatoes, seed grain, and cash loans, as well as in the provision of personal items, such as shoes and clothing. Through a system of poor rotation, or legd, each farm was expected to feed and lodge a pauper for a specified amount of time, usually a week, at the end of which he or she would be rotated to a neighboring farm. This economic web of relationships was reinforced by marriage and kinship relationships and a strong attachment to and sense of place. Hardanger was an unforgiving yet special environment, and a microcosm of the story of mass movement of Norwegians to distant shores and a western home.1

Between 1815 and 1865, Norway’s population nearly doubled as the curve of child and infant mortality steadily fell with health-care advances. In Hardanger, smallpox vaccinations were pioneered by the parish priests in the first years of the nineteenth century. Population increase placed harsh demands on the cramped fjord communities. Land was limited and generally transferred to the eldest son, relegating siblings to cotter and labor positions. Concurrent with the upsurge in population throughout Norway was the fragmentation of land holdings by partible inheritance and the emergence of a large rural proletariat. Land subdivision and breaking of new plots provided inheritances for the eldest sons and dowries for daughters, but this did not keep pace as population grew and the demand for farmsteads intensified. More and more people patched together plots in marginal areas from which to eke out an existence. There were hungry years, when crops failed and herring populations were sparse. The most important social structural change involved the rise in numbers of the cotter or husmann group, a group disproportionately represented in the mass emigration of the nineteenth century.2

Human pressure was decisive in encouraging migration from Norway, in part because there were few alternative internal destinations. The “America fever” spread early and fast in Hardanger, and its young people were easily influenced to follow ethnic paths across the sea. The Norwegian exodus to America commenced with the departure from Stavanger on July 4, 1825, of 52 religious dissenters (Quakers) led by Cleng Peerson on board the sloop Restauration. After a short-lived agricultural settlement at Kendall in western New York State, the sloopers sold their properties and headed west and, in 1835, they began their selection of lands along the Fox River in northern Illinois (LaSalle County), the first permanently rooted Norwegian settlement in America. Two shiploads of emigrants arrived from Norway in 1836, and although some remained behind in Chicago and formed the nucleus of an urban colony, this transport added substantially to the numbers in the Fox River Valley.

Gjert Hovland, together with his Hardanger-born wife and children, were counted among the sloop settlers. He was a prolific letter writer, optimistic in spirit, and his long, favorable accounts of life in America were hand-copied and distributed by the hundreds in Hardanger and neighboring regions. In 1835, Hovland wrote to his brother-in-law, Torgils Meland of Ullensvang, and vividly described the conditions of his new home: There is “beautiful and fertile soil,” he wrote, “employment and a livelihood for anyone who is willing to work. . .” He noted a classless society where taxes are virtually unknown, there is religious freedom, and laws work to “guarantee the common man’s well-being and advantage.”3

The first contingent of emigrants left Hardanger the following year (1836) and a second followed in 1837, both migrating into northern Illinois. The America fever spread like a contagious disease: In 1838-1839, no less than 40 men and women left Eidfjord, Ulvik, and Granvin parishes in Hardanger to join their countrymen in the Illinois colonies.4 By the late 1830s, land pressure and malaria outbreaks in the Illinois settlements deflected some migrants to Jefferson and Rock Prairie in territorial Wisconsin.

Emigration mania grew as information was disseminated, by letters and leaflets, handbills and newspaper accounts, word of mouth, and the first-hand testimonials of returned migrants. As the America fever spread parish to parish throughout the country, secular and church leaders alike expressed alarm at the increasing numbers of emigrants, especially the young in their most productive years. Bishop Jacob Neumann of Bergen deplored the migration as “a national bloodletting.”

The waves of emigration from Norway correspond closely to the general pattern of North European migration to the U.S., with several crests and dips, the latter created by world wars and depressions. Within Norway, the America fever did not spread uniformly and concentrically outward from the

Descendants of the Sloopers with a model of the Restauration, at the Norse American Centennial, held at the Minnesota State Fairgrounds, June 6 – 9, 1925. Vesterheim Archives.

early core of emigrant activity in the southwest of the country, but was spotty and intermittent, flaring to the north in Voss, throughout the inner valleys of Sogn, and in the east in Telemark and Numedal. During the first decade of emigration, 1836-1845, Telemark, Numedal, and Hallingdal accounted for two-thirds of Norway’s emigrant population.

Migrants from Upper Telemark (1839) passed by way of the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes to Milwaukee, taking land in territorial Wisconsin (Waukesha County) near Muskego. In addition to being an immigrant gateway, Muskego was the center of early religious, political, and educational activities within the Norwegian-American community. It was there, in 1844, that the first Norwegian Lutheran Church in America was constructed. Costly outbreaks of malaria in the mid-1840s, followed by deadly cholera, spelled doom for the Muskego settlement, and it shrank from pre-eminence as settlers searched for more advantageous settlement sites to the west.5

With the end of the American Civil War and passage of the Homestead Act (1862), America became more alluring and, in the wake of several miserable years, the America fever was said to rage in the veins by the late 1860s. Emigration slowed during the intermittent good and bad years of the 1870s, but the floodgates opened in the early 1880s, sending unprecedented numbers of Norwegians to overseas destinations.

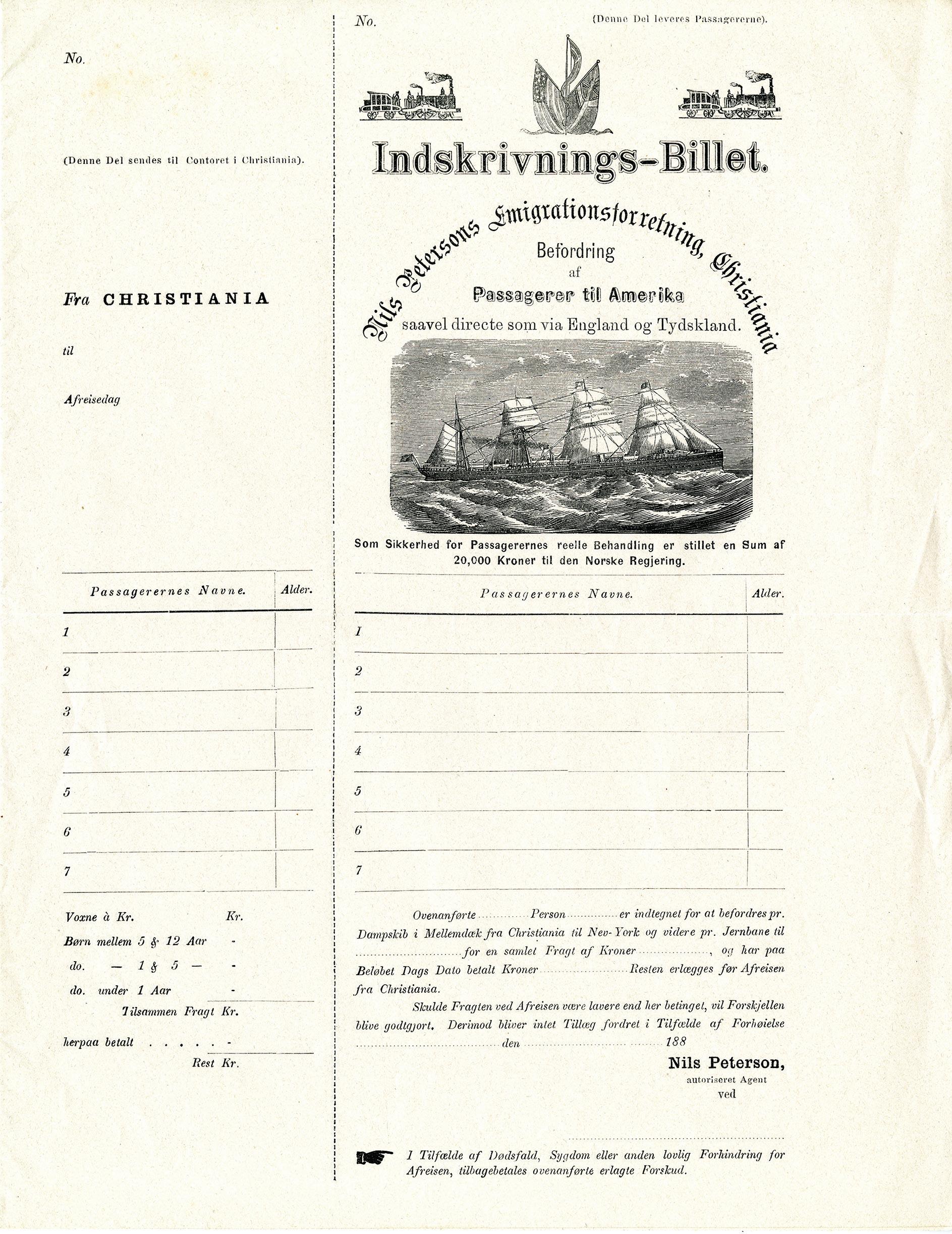

Once the pinnacle was passed, prepaid tickets or travel money filtered into the home districts to keep the streams flowing, a phenomenon undoubtedly facilitated by price wars among the steamship lines. The cost of a ticket from Norway to Minnesota held steady at about 210 kroner through the second half of the nineteenth century. Migrants often took loans or sold possessions to fund their passage. Some received remittances and pre-paid tickets from their kin in America. A bump in the emigration occurred on the heels of the American financial crisis of the 1890s, although emigration never again

reached the heights of the 1880s. With improved labor and earning options in Norway, migrants from Norway to the U.S. tapered off into the twentieth century, their numbers replaced by cheap labor from southern and eastern Europe.6

While the emigration from Hardanger was moderate to heavy at times, some of Norway’s regions and parishes exhibited light emigration, especially those with a more diverse economy, land resources, and stronger carrying capacity. What constitutes the complex of motives that determined the decision to stay or to leave?

Personal ambitions and aspirations were variously compounded with economic cycles, demographics, inheritance, kinship, and family circumstances. Young people ages 16-30 were the strongest represented among all of the age groups that left Norway and their proportional share increased through the nineteenth century. The oldest movers, those over 45 years, are not numerous in any decade and, like dependent children, diminished proportionately toward century’s end. The proportion of working-age single migrants grew at the expense of older, married migrants, a trend identified for other immigrant groups that came to the U.S.

Kinship was a key motivating factor in the decision to emigrate, both a push and a pull factor, and is largely responsible for the self-generating character of these great transatlantic migrations through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. People moved in chain migration, part of established flows of family members and friends, and in specific channels from common origins to common destinations. Colonization efforts led by churchmen, railroad, and steamship companies brought people from a common parish in Norway to a common congregation in the Midwest. Settlers in the North Beaver Creek community of western Wisconsin, for example, came overwhelmingly from the parishes of Inner Hardanger in a well-established and vibrant chain migration of sibling groups and parents with children. Family members in America offered ticket money, temporary housing, and advice on accommodations, employment, and land taking, making the move more inviting and less daunting.

Spring offered special advantages as a departure time, giving the new arrivals ample time to find work or a first farmstead before the onset of winter. Sharing familiar customs and language, immigrants naturally clustered in ethnic enclaves in both rural and urban settings, i.e., Brooklyn’s Red Hook-Bay Ridge, Minneapolis’s Nordic neighborhoods, Minnesota’s Norwegian Ridge (Spring Grove), Chicago’s Milwaukee Avenue colony, Poulsbo near Seattle, and Stoughton and Westby in Wisconsin.

Northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin served as the cradle of Norwegian settlement in North America, Minnesota became the heartland of their settlement, and Minneapolis and Chicago emerged the undisputed centers for NorwegianAmerican organizational life. Mass immigration of Norwegians was well-established by the late 1860s, with New York, Quebec City, Chicago, Milwaukee, and Minneapolis serving as key gateways. The earliest migrants flowed into Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa, and later migrants moved into Michigan, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Kansas, Texas, and enclaves to the west.

Old, established settlements, such as Koshkonong in southern Wisconsin, gave birth to new colonies across a large swath of the Upper Midwest and westward into the mountain and Pacific states. Norwegian settlers were enticed by propaganda from the railroads, states, and steamship companies, as well as the individual efforts of ethnic colonizers. They were drawn by the Northern Pacific and Great Northern Railways into the Dakotas and settled in farm and small-town settings among other immigrant groups. Norwegians operated mixed grain-livestock and wheat farms, worked as contractors and builders, and quickly became upwardly mobile in the professions, especially with the second generation. However, Norwegian-Americans remained more rural and farm-focused than the other Nordic groups well into the twentieth century.

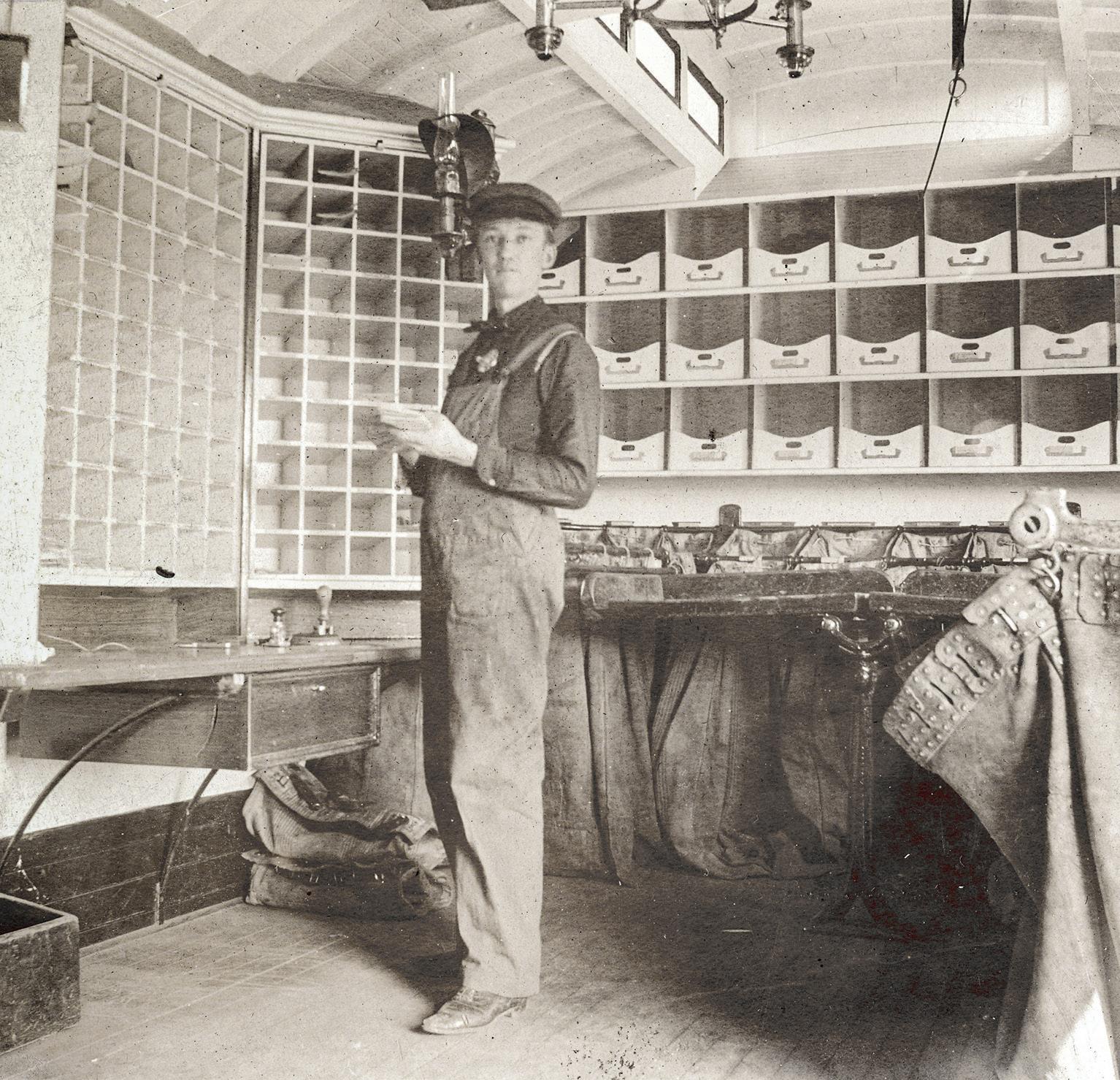

Many Norwegian immigrants were farmers who supplemented their incomes by seasonal work in the lumber camps. Others were iron miners or found employment in cities such as Superior, WI, a port for grain and iron exports. Most Norwegians migrated to the Canadian Prairies indirectly via the northern United States. They followed the tracks of the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National railways, mostly westward from Winnipeg, and took up residence alongside

other Nordic migrants. They avoided the dry prairies, settled the parklands of mixed grass-woodlands, and established themselves as lumbermen and agriculturists in mostly mixed farm and wheat operations. They gravitated toward the professions in prairie towns and cities, most of them employed as industrial, craft, and railroad workers.7

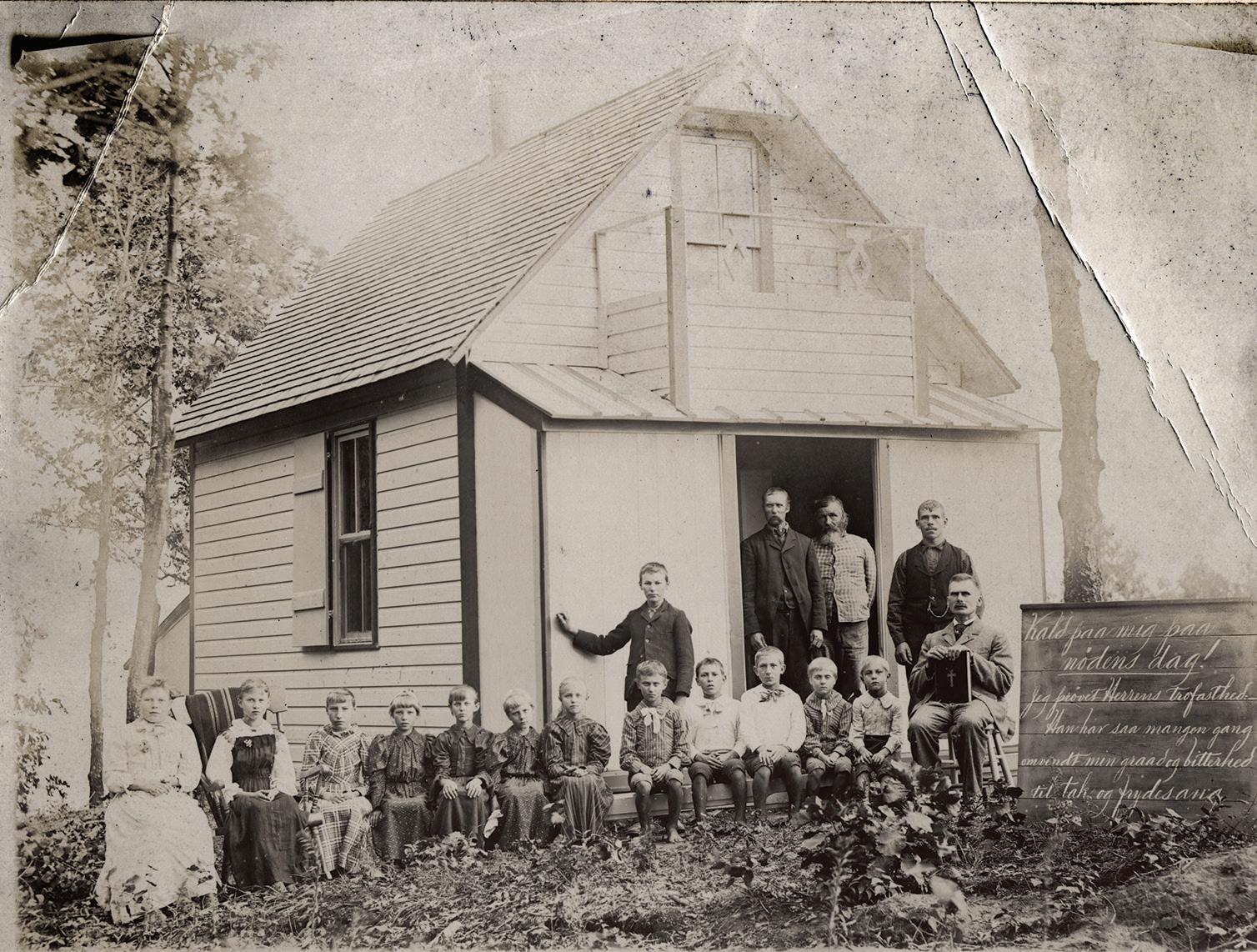

Norwegians established a flora of ethnic organizations, newspapers, medical facilities, schools, and universities and, of those who had a religious affiliation, most were members of the Norwegian Synod of the Lutheran Church. Some were members of the German-led Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church, Conference, Haugean and Eielsen Lutheran groups, the Free Church, Methodist, and other Protestant denominations.8

Pride in Norwegian heritage has been epitomized through the generations in Syttende Mai, Midsummer, and other ethnic activities, such as Sons of Norway events, bygdelag gatherings, congregational lutefisk dinners, and community song fests. Norwegian national holiday Syttende Mai celebrations are held in far-flung locations from Minneapolis and Chicago to Poulsbo, WA. Among the leading centers for NorwegianAmerican history are the Norwegian-American Historical Association in Northfield, MN; the heritage collection at Vesterheim Museum in Decorah, IA; the Norwegian American

Genealogical Center and Naeseth Library in Madison, WI; the National Nordic Museum in Seattle, WA; and Scandinavia House in New York City.9

Norwegians who migrated to the U.S. after the Second World War settled mainly in major metropolitan gateways like New York, Chicago, Minneapolis, and Seattle. In recent decades Norwegian immigrants to the U.S. have been mostly of the professional class, live in metropolitan areas, and generally have not built links to old, established NorwegianAmerican communities or joined ethnic organizations. Thousands of Norwegian citizens live and work in American cities today as, for example, Houston, TX, in connection with the oil industry; Washington and New York with international companies and government agencies; and San Francisco, Seattle, and Minneapolis in medical, high-tech, and other professional careers.

The great transatlantic migrations brought more than 900,000 Norwegians to the U.S. from 1825 to the present, with 87% of them migrating between 1865 and 1930. The peak year was 1882, with 28,788. Chain migration resulted in the transplantation of old-country patterns and practices, many of them tied to folk traditions and Lutheranism. Use of the ethnic language is limited today, but Norwegian

America still embraces many elements of its ethnic heritage, such as ethnic foods, music, and holiday traditions. Due to a heightened interest in ethnic identity, the number of Americans who identify as “Norwegian” in the U.S. census has grown steadily in recent decades. In 1980, 3.45 million Americans claimed Norwegian ancestry; by 2009 that number had risen to 4.64 million. Minnesota leads today in the number of citizens of Norwegian ancestry (868,361), followed by Wisconsin, California, Washington, and North Dakota.10

There were always voices of longing, homesickness or disillusionment, regrets at the loss of a motherland, and some acted on their impulses by returning to their home communities. Men were more prevalent in the return migration than women and, among both groups, the largest single category was composed of persons under the age of 30. The majority traveled home alone rather than in the company of kin and friends. Most emigrants from Norway never saw their homeland again. For some, regular visits home kept families intimately connected through the generations.11

Norwegian migrants were generally well received by their host society, fitting in reasonably well within the expectations of White Anglo-Saxon Protestant society. As farmers, domestics, and industrial laborers, they were generally welcomed by their hosts as reliable and hardworking. But Norwegians in America did not escape ethnic stereotyping as, for example, the comments and cartoons that portrayed them as simple-minded farmers, drunken sailors, and fierce, pillaging Vikings. They were also the victims of quack doctors and traveling medicine men, unscrupulous business people, and opinionated churchmen who led them into divisive

Ole A. Anderson, the son of a pioneer pastor, was said to be the most popular young man in Decorah, Iowa—tall, blonde, handsome, well-mannered. He met Mary Katterud, the first public school teacher from Winneshiek County, they fell in love, were betrothed, and Mary began planning their wedding. Then came Lincoln’s call to arms, and the Decorah Guards chose Ole Anderson to be their lieutenant. At the Battle of Blue Mills, Ole took a musket ball to his head. Almost collected into a burial cart, Ole spent eleven months in a Union hospital before he was sent home to Mary—a broken man, mentally shaken, never to recover, a Confederate musket ball still lodged in his temple. Vesterheim Archives.

debates on subjects such as slavery, predestination, church versus public schools, language, and women’s right to vote. Universal education in Norway meant that most migrants were literate and many Norwegians joined the efforts to establish schools, colleges, and educational programs in their new environment. They played active and visible roles in advancing health and sanitation campaigns. They fought infectious diseases, provided leadership in water and food control, made medical advances as doctors and researchers, and brought American norms of domesticity into their homes and communities. A decent home, good health, education for their children, and Christian respectability were Victorian ideals to which the immigrants aspired.

The Souvenir booklet prepared for the centennial of Norwegian immigration (1925) shows an impressive record of involvement by Norwegians in reform movements, e.g., the League of Women Voters, The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Red Cross, Young Women’s Christian Association (and YMCA), Parent Teacher Association, Eastern Star, and the boards of hospitals and humanitarian groups.12 Old models of bedlag, dugnad, and community cooperation encouraged

them to collaborate on projects and causes in their American neighborhoods and communities.

Some Norwegian Americans took up the gospel of reform as formal educators and administrators in the public schools, acting as proponents of scientific farming and domestic science or “proper housekeeping.” Agricultural extension programs and institutes and a plethora of printed media preached the virtues of scientific approaches to improving the public health and, in particular, the living standards in rural America.

Norwegians in America participated in many capacities at many levels in conducting reform and did so through education. They were keenly aware of the need for educating their children, both male and female, and they founded schools and academies quickly on the heels of their arrival. Norwegian immigrants had benefited from some schooling in their homeland—nearly all at the elementary level, and a few at the teachers’ seminaries, folk high schools, and universities. The value of that education was generally not questioned. Life in the Old World had taught them to view education as symbolic of social rank. Practical life skills and thinking for oneself, moreover, were fundamental to their pioneer existence.

The first schools were generally modeled on European prototypes in which children met in private homes, the omgangsskole (ambulatory school), lessons were taught by the most educated male, and religion was the primary subject. Children were to be educated for catechism and confirmation and to lead good Christian lives.

Religious instruction was the core of a child’s education and, according to Clara Jacobson (Blue Mounds, WI), “much of the early training fell to the mothers who supervised the children’s lessons while they did their sewing, spinning, and carding. The first step in the educational process began with learning the ABC’s in preparation for reading prayers and then the Catechism. For Jacobson, this began at the age of seven, and she learned to read ‘Norwegian first of course.’”13 The America letters are replete with examples of proud parents writing home about the intellectual development of their children. Susanne Kristiansdatter and Alf Nielsen wrote from the Blue Mounds community:

“We will now report a little about our daughter Turi, that she has learned to read Our Father and table prayers and other small prayers.” A year later Turi read every day and her sister Gunhild had learned to spell. Two years later Guri had learned the entire Catechism and read avidly. These children had made excellent progress and had never attended a day of school.14

Before the advent of Rural Free Delivery (RFD) and public lending libraries, Norwegians in America banded together in reading societies to assure access to books and magazines in rural communities. Reading societies, or laeseselskaber, in Norwegian-American communities numbered in the hundreds. These were generally well organized societies with constitutions, by-laws, and specific guidelines for membership. Some groups were gender- or age-specific, while others had a mix of farmers, farm wives, elderly residents, and teenage boys and girls. Unlike Norway, where books would have been prescribed by librarians and ministers, the rural reading societies afforded settlers the opportunity of free

choice, from light fiction to Norwegian literature to pragmatic articles about life and farming. For the children of the home, they provided early exposure to the classics, current affairs, Norwegian literature and history, and very practical details about scientific housekeeping and farming. Reading societies were convenient and valuable steps on the way to becoming American.

From the 1840s to the 1870s, Norwegians in America were drawn into the debates about the common or public schools versus the parochial schools. In the Manitowoc Declaration of 1866, the ministers of the Norwegian Synod debated whether the American or common school should be called “heathen” or “religionless,” and ultimately decided on the use of “religionless” as less offensive to their American neighbors. The official position of the Norwegian Synod was that the common or secular schools, run by atheists, were “corrupting their children.”

Because of danger in American education, the Synod would build a parochial system of such high quality that it would be unnecessary for Norwegian Lutherans to send their children to the district schools.15

By the 1860s, it was clear to most Norwegians that a vocational or professional education was possible only in the Americans schools, and hence, the Scandinavian Lutheran Educational Society was formed and the campaign began to “place Scandinavian professors in American colleges and universities.”16

Rasmus B. Anderson joined the school debates in the 1870s, advocating for the common schools, eventually infuriating the church leaders by calling American schools “a thousand times better than ‘these sideshows’ of schools which the Synod has established.” Anderson and other proponents of common schooling warned that the parochial schools “would only isolate the Norwegian immigrant from the mainstream of American life.” Anderson believed firmly that the Norwegians should embrace the American school system. “The doors to this country’s schools,” he wrote, “are open to us. The American does not distinguish in his high schools, academies, and universities, but invites the immigrant child to the school desk, to sit together with his own. Why not accept this generous invitation?”17 For churchmen the need was obvious: place Norwegian Lutherans on public school boards and train more teachers from the Norwegian community to teach in the public high schools, academies, colleges and universities.

The vast majority of Norwegians accepted the American school system, believing that Norwegian language and culture could be maintained and the Lutheran faith preserved through proper training in the church and home. They built and maintained these schools, hauled wood to heat them, and charted the progress of their children as they learned the English language and American ways. Thus, the cultural effect of American education was Americanization, the creation of a dual identity, with an intermediary Norwegian-American language, i.e. Norwegian phonetic spelling of English words and many “new” words mixed into Norwegian in letters home. “We have gotten a school teacher from Norway who is a seminary student,” wrote Engel Bjotveit from North Beaver Creek in 1869. “He shall conduct school six months—and the remainder of the year in another district—earning $25 a month—we also have an English school, which can be used by anyone at all.”18

Migration research has long recognized emigration as a highly selective and time-specific process heavily influenced by economic conditions. People seek opportunity. An overwhelming number of Norwegian migrants to America were economic refugees in search of a better life for themselves and their children. The story of Norwegians coming to America has repeated itself many times through the decades as migrants/asylum seekers have arrived in the U.S. from many disadvantaged, often war-torn areas of the world. For all of these immigrant groups, we have seen one overarching theme—a search for a better life for them and their children,

and within that theme many sub-themes: persecution, want and despair; kinship and community; youthful adventure and optimism; job seeking and upward mobility; prejudice and stereotyping; religious bearings; homesickness; language issues; generational conflict; education and reform; political debates; and the ebb and flow of migration in response to the larger currents of economic and political change.

Throughout American history, immigrant policy has fluctuated in response to the vacillations of the public and the wrangling of its politicians, sometimes open and inviting, at other times closed and threatening, treating asylum seekers as criminals. A large share of the migrants in the world today are fleeing circumstances of violence, crimes against humanity, and that poses profoundly difficult ethical dilemmas in cases of arrest, detention, and family separation.

Immigrant settlement has been largely logical and practical through the decades, with migrants congregating together in mutual aid and shared heritage. Migrant networks have generally been powerful in aiding migration and in facilitating the integration of their members into American society. Those immigrant clusters and networks have never been rigid or static, however, but malleable and changeable, expressing the fluidity of the American experience.

No immigrant group in America has lived and thrived in a vacuum, segregated from other ethnicities. Each has faced prejudice and challenge, debacles on the border, and documented versus undocumented issues. Each has transplanted elements of home cultures in America while adapting and acculturating in a dynamic transnational environment. Those who left the hard life in Hardanger for a new life in America built successful lives based on the transplantation of their old ways—and adaptation to new ways—on their way to becoming American. That is the immigrants’ story.

Endnotes

1 Tobias and Agnes Lægreid, Gards- og ættesoge for Eidfjord (Eidfjord kommune, Hardanger, Norway: Kulturkontoret, 1992).

2 Ann Marie Legreid, The Exodus, Transplanting, and Religious Reorganization of a Group of Norwegian Lutheran Immigrants in Western Wisconsin, 1836-1900, doctoral dissertation (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1985).

3 Olav Kolltveit, Granvin, Ulvik og Eidfjord i gamal og ny tid, vol. II (Bergen: Boktrykk, 1977), cited in Ingrid Semmingsen, Norway to America, A History of the Migration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 18.

4 Legreid, 130-144.

5 For a summary of these early settlements, see Semmingsen, 10-31.

6 For a statistical analysis of the migration from Hardanger to western Wisconsin, see Legreid, 145-237.

7 Odd S. Lovoll, The Promise of America: A History of the Norwegian American People, revised edition. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

8 Clifford E. Nelson and Eugene L. Fevold, The Lutheran Church Among Norwegian-Americans, vol. I & II (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing, 1960).

9 April R. Schultz, Ethnicity on Parade: Inventing the Norwegian American Through Celebration (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994).

10 Odd S. Lovoll, “Norwegian Americans,” retrieved on April 14, 2020, from https://www.everyculture.com/multi/Le-Pa/NorwegianAmericans.html

11 Legreid, 237-243. For an in-depth analysis of re-migration, see Mark Wyman, Round-Trip to America. The Immigrants Return to Europe, 1880-1930 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993).

12 Norse-American Centennial Souvenir booklet, Norse-American Centennial Committee, 1925.

13 Monys Ann Hagen, Norwegian Pioneer Women: Ethnicity on the Wisconsin Agricultural Frontier, master’s thesis (Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1984), 107. For statistics on educational institutions, see Martin Ulvestad, Nordmændene i Amerika, deres Historie og Rekord, vol. I (Minneapolis: History Book Company, 1907).

14 Hagen, 108.

15 Frank C. Nelson, “The School Controversy among Norwegian Immigrants,” in Norwegian-American Studies and Records, vol. 26 (1974), 210.

16 Nelson, 211.

17 Nelson, 217.

18 Letter from Engel Bjotveit, North Beaver Creek, Wisconsin, to family in Norway, February 3, 1869. Norwegian American Historical Association, private collection.

About the Author

Ann Marie Legreid is professor of geography at Shepherd University in Shepherdstown, West Virginia, a public liberal arts institution beneath the Blue Ridge Mountains. She earned her Ph.D. and M.S. in historical geography from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and her B.S. in geography from the University of Wisconsin-River Falls. She has also been an academic dean during her years in West Virginia. Her specialties are European and North American geography, cultural geography, population and development, and migration studies. A Wisconsin native, her ancestral roots are in Eidfjord, Hardanger, and Flisa, Åsnes, eastern Norway.