Imagine this.

After a meal of boiled potatoes, sliced meat, and apple pie with a sugared top crust, a curly-haired child opens a jewelry box. Colorful strands of necklace beads taper towards their clasps. Flower-shaped rhinestone brooches sparkle like fairy wings. Pairs of earrings rest on velvet. Glancing at Kristine, who naps before an afternoon of quilting, the six-year-old pulls out of the magical box what she loves most: a Norwegian sølje

Once belonging to Kristine’s mother, the pin is a cascade of lacy filigree. Its silver dangles shimmer like creek water in sunlight. Cradling loveliness in her hands, the little girl imagines wearing the treasure at the neck of her blue plaid taffeta dress—where the Peter Pan collar pieces meet—to church on Sundays. She could push her tumbling hair back with a plastic headband to show off the matching earrings. When Kristine, who is 70 years older than her visitor, stirs, the young daydreamer places the sølje in the old woman’s jewelry box and scurries to the guest bedroom to pretend to nap.

It’s 1962.

Above, the author as a four-and-a-half-year-old angel.

Sweet days with Kristine Goli float into my mind when I piece together the story of a childhood in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Norway shaped my fiercely ethnic community of fewer than 100 people in the heart of southern Wisconsin, not far from Madison. Fragments of memories and oral history aren’t enough to make sense of my past, so more than 40 years after I moved from Daleyville, I enter Vesterheim Museum, where a collection of Norwegian søljer gleams under glass. Looking at brooches and bridal crowns, with round and diamond-shaped dangles to ward away evil spirits, I contemplate the everyday mysteries of being a Perry Norwegian Lutheran Church pastor’s daughter. As an adult, I step out of details to understand my long-ago home in a Norwegian-American enclave.

In 1958, when my parents and I moved to Daleyville, the place had the personality of a cozy grandparent. Most grownups who lived on either side of the county road that made up the unincorporated village’s only significant street had emigrated from Norway, or were first- or second-generation Norwegian Americans. Old folks moved in when they retired from milking cows and harvesting crops. Like Kristine, who was the church organist, they hissed their Ss and breathed in audibly when they said “yah” while listening. Women handed out lefse wrapped in white napkins at Halloween. Only a handful of children lived in Daleyville. Young and middleaged families farmed the lush countryside. The school had two rooms.

My dad’s majestic church stood at the crest of a ridge, across from the school. Its name, Perry, connected to the Perry Norwegian settlement that spanned about 60 square miles and was divided into ten school districts, including Daleyville.

The Daleyville Store sold bottled milk, canned goods, and other basics; people didn’t have to drive the curvy eight miles into Mt. Horeb unless they had urgent errands. Outside

Rural Norwegians, until about the mid- to latenineteenth century, usually wore silver every day and definitely on special occasions. Men might wear silver collar pins, buttons, and buckles. Women commonly wore søljer, or brooches. Even babies wore tiny silver ring-shaped pins. Søljer held the blouse closed, added ornamentation, could be a form of portable wealth, and were believed to provide some protection against both real and supernatural threats. Some styles are specific to particular fylker or counties, others were used all over Norway. Søljer were frequently brought to America by immigrants, and women continued to wear them here for reasons of ornamentation and ethnic pride.

Sølje from Rogaland, Norway, early twentieth century. Vesterheim 1982.025.001—Gift of Mrs. Louis H. Hein.

Left to right:

Earring, Oslo, Norway, 1960. Vesterheim 2000.070.001.3—Gift of Mary Severson.

Earring, Dokka, Oppland, Norway, circa 1930. Vesterheim 2000.039.008.a—Gift of Stanley Morud.

Earring, Lervik, Stord, Norway, mid-twentieth century. Vesterheim 1982.015.014.1—Gift of Ethel M. Jensen.

of the store, around the back, vats of lutefisk showed up at Christmastime. Inside year-round was a wheel of Swiss cheese, sold in wedges. The blacksmith shop next door morphed into a car repair business, operated by a man with greasy hands. The post office, creamery, gristmill, newspaper, and performance hall had long since disappeared. Daleyville, which became a formally recognized hamlet with the arrival of two Norwegian brothers—O. B. and Tarjie Dahle—in 1853, was not the lively economic center it was in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Even so, more than 30 homes, mostly constructed between the 1890s and 1915, remained.

Sidewalks unpredictably appeared and disappeared, but from one end of Daleyville to the other was a short walk. Folks knew each other and knew where everyone lived. Near the north edge of Daleyville, for instance, flowers in summer window boxes marked the house belonging to dear, middle-aged twins. Anna and Amy Haadem did housework in Madison (the capital city about 25 miles away) and tended fragrant red geraniums that bloomed in pots inside their living room during winter. Kristine’s white house was four up from Anna and Amy’s, sheltered by a windbreak of spruce.

Before I met her, Kristine worked as a piano teacher, traveling weekly by horse and buggy to the homes of more than 25 girls and young women to teach scales and classical music. In an outdoor group picture circa 1910, her pupils wear white dresses adorned with long chain necklaces. Some have gathered their hair in stiff bows. Kristine started as organist for Perry Lutheran when she was about 15 years old—first filling in for her older sister who was too ill to play for a wedding. She was the church organist for 69 years.

As a two-year-old, I started my tradition of going to Kristine’s house (at her invitation) to spend the day. New in Daleyville, I was friendless, except for my young religious

parents. Kristine’s upright piano, which I plunked, was in the parlor, the dark room with a picture of her mother in an ornate frame on a marble-top table. Kristine took care of her frail brother Adolph, whose eyesight was nearly gone and his abilities limited; he was a shadowy figure with a cane and sunglasses, often sleeping. In Kristine’s backyard, a silver pump spilled cistern water into an enamel pail we carried into the house because Kristine said it tasted better than what came out of the indoor faucets; we used a long dipper to pour water into clear glasses when we mixed up mid-morning drinks of sugaryorange Tang. She called me søte tulle, the name her mother had called her. I thought it meant “little spiller,” because my water often sloshed onto the table. Now I know her Norwegian words were those of endearment: sweet little girl.

My busy parents, serving their second Lutheran congregation, appreciated Kristine’s many happy offers to entertain me for the day. Besides officiating at church functions, Dad orchestrated the controversial construction of an educational wing, navigating between two factions who argued, at times, in Norwegian. My mother was Dad’s unsalaried daily helper, as were most pastors’ wives back then. Kristine, who never married, and I became best friends; she knew my overextended mother needed support.

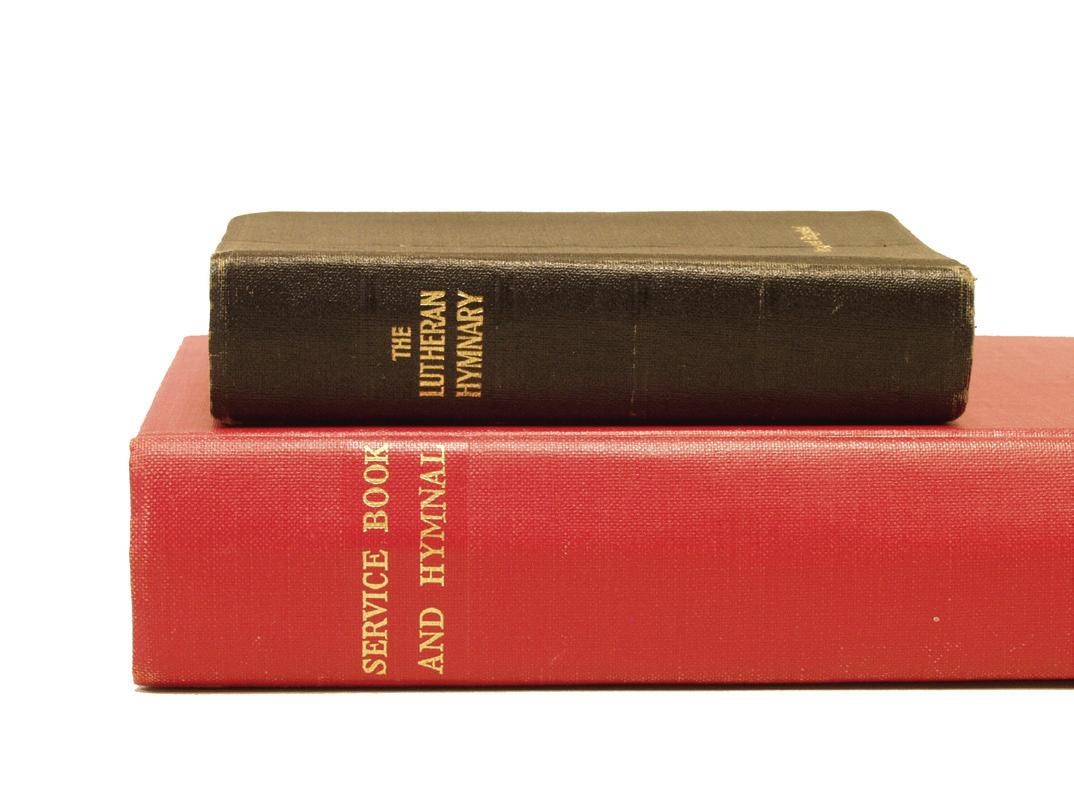

Some days Kristine took me along when she practiced the organ. With an array of stops at her command and her feet stepping on pedals as if she were a fast dancer, Kristine thundered out songs from the red hymnal. Occasionally she played the music for songs in the small black hymnal—the lightweight book that had no notes. A few irate people left my father’s congregation over the introduction of the red hymnbook, claiming it was too heavy to hold. Kristine’s preludes were soothing, reflective. I sat on the bench at her side and watched the music without knowing what the notes meant, or I sat on a wooden pew, studying stained-glass windows edged with uneven agate-colored bands and a series of medieval four-petal flowers.

Besides filling our days with music, Kristine and I prepared food. Some mornings we made lefse—mixing cooked potatoes, butter, flour, salt, and sugar in a big bowl with our

The “Black Hymnal” and the “Red Hymnal” The Lutheran Hymnary—Vesterheim Library. Service Book and Hymnal—Vesterheim Library—Estate of Constance Jacobson.

finishing touch. Kristine slipped a hand-carved lefse stick under the flattened dough circles and dropped them, one at a time, on the hot griddle. After turning them once to brown both sides, she piled them on a kitchen plate. With a too-big floral apron across my chest and under my armpits, a bow tied across my back, my job was keeping the stack warm under a white towel embroidered with a day-of-the-week theme in one corner. When the lefse was fresh, we ate samples slathered with butter and sugar. Other days we fried doughnuts in sizzling oil, or we baked cookies. Whatever we made, I carried a couple dozen home in a paper bag.

While I walked into Kristine’s heart, my dad had a shakier start in Daleyville. When the Perry Norwegian Lutheran Church Board of Trustees called him as pastor, they assumed he was one-hundred-percent Norwegian, truly one of them. They believed the “sen” in “Andersen” was a mistake for “son,” not an indication that he had a Danish father; some parishioners could not accept the fact that my father was only half Norwegian. The tradition of Perry pastors with pure Norwegian lineage was broken. In a few church records to this day, “son” is still uncorrected. My mother had not an ounce of Scandinavian blood in her German background. Growing up in Washington, D.C., and traveling to New York City on trains with white-gloved girlfriends to visit museums had not prepared her for English conversations that switched into Norwegian, or the custom of “julebukk-ing.”

She and my father, who knew nothing of the custom either, didn’t expect 15 disguised parishioners to show up in the living room on our first Christmas night in Daleyville— even if the house came equipped with a rosemaled kubbestol carved from a hollowed tree trunk.

Masked intruders, draped in oversized winter coats on backwards and sporting unzipped galoshes, sat silently for a long time while my mother and father fretted about what to do after rounding up more chairs. The Christmas service was long over, so no one needed to get anywhere fast. Offering festive cookies got no response. Asking the mute visitors what they wanted didn’t work. Eventually the uninvited guests uttered a few squeaking noises and grunts as clues.

Even if my baffled parents had realized the object of the game was to correctly guess the identity of each julebukker to make him/her depart, they had only been in Daleyville a few months and did not know every church member by name. The congregation had a tangled membership roll of close to 1,000. Finally, the merry-makers removed their disguises and chatted. Before they left, they ate a light lunch my mother quickly pulled together: coffee and leftover rosettes, krumkake, and berliner kranser that congregation members baked and brought on platters to us earlier that week.

As well as keeping alive the “julebukk-ing” tradition that had been forsaken by most Norwegian-American enclaves by the late 1950s, parishioners remembered fusses between Perry Norwegian Lutherans over “high-church” Norwegian customs versus “low-church” American practices, predestination, and benevolence. Surprisingly, as folks didn’t have much money in the 1860s, the congregation gave the generous sum of $1,134 towards the formation of Luther College, whose early mission was training pastors and teachers who had Norwegian ties. Past tragedies were not forgotten, either. In May 1878, a tornado damaged the church and parsonage soon after Pastor

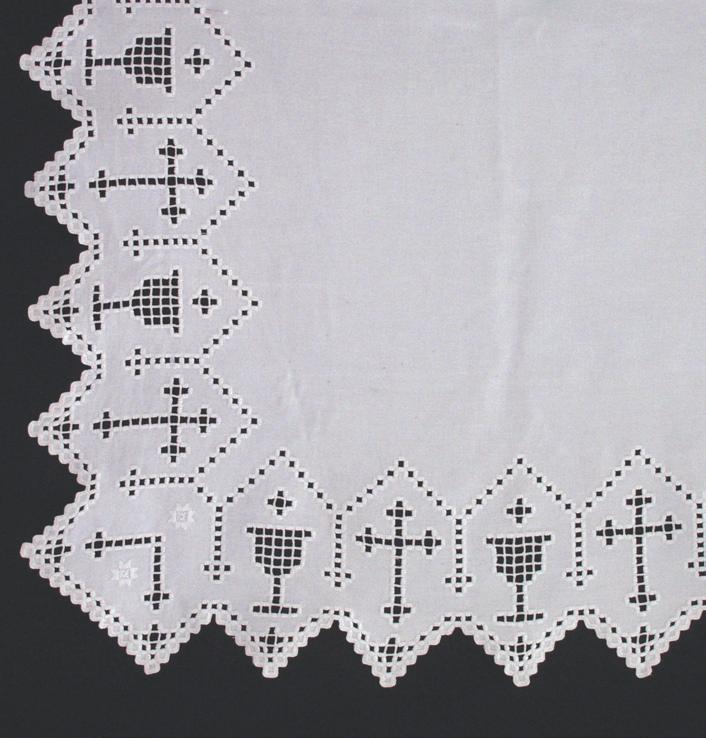

Altar cloth with hardangersøm made by Dorothy Holst in 1964 for the Norwegian Seamen’s Church in Brooklyn, New York. Detail. Vesterheim 1984.138.001—Gift of Norwegian Seamen’s Mission by Pastor Jan Johannesen.

When they conducted services in their home or a parishioner’s home, many times pioneer pastors made do with a table or trunk as an altar and a nice linen tablecloth as the altar cloth. Once churches were established, a specially-made textile, in white or the color of the church season, would go on the altar. Hardanger embroidery, a counted thread embroidery with cut and drawn work, is well suited for altar cloths and other church textiles.

Abraham Jacobson resigned due to poor health. On the day of the storm, Jacobson and his family were preparing to move shortly to his boyhood home, a farmstead outside Decorah. The pastor, who was carrying packed boxes into the summer kitchen, was injured by flying debris and lifted into the air. Pastor Jacobson’s teenage daughter, Clara, was upstairs writing a good-bye note in her teacher’s autograph album when the roof was ripped off the parsonage and all the windows shattered. After the storm, Clara found her Norwegian sølje by a gatepost.

Brilliant lightning strikes in 1888, 1903, and 1935 were reasons the church of my childhood had a short tower instead of a pointed steeple—no one wanted to tempt the weather’s fury further. The last strike started an uncontrollable night fire, leaving a shell of blackened stone. The Gothic-style church, rebuilt after the wild 1935 thunderstorm, sits on its original hillcrest.

When I stood in the churchyard on a sky-blue day and looked in all directions, I saw farms marked by groves of shade trees and crop fields: true dairy country. My small world seemed big. Blue Mounds—another Norwegian pioneer settlement whose name felt good on my tongue, but never seemed like any blue shade in my box of crayons—was visible to the north. A plaque near the church’s front door recorded that Perry congregation was “Organized Nov. 5, 1854.” A state-church-style splinter group from the local Haugeaner parish, their first service in their own building was held on Christmas Day 1858, roughly 100 years before my family arrived.

Inside our church, white and golden Gothic chancel furnishings were enshrined in a rounded apse. On the altar, a painted wavy-haired Jesus stood with his arms out in blessing,

his hands showing nail holes of Good Friday. Hardanger embroidery covered the altar table. As pastor on Sundays, my dad wore a flowing white surplice (a version of the robe I wore when I sang “Jesus Loves Me” in junior choir) over a long black cassock. Adorned with a satiny, fringed stole, his clothes seemed more suitable for a woman than a man. He didn’t look like the stern photos of many previous ministers lined up on the basement walls, fancy ruffed prestekrage encircling their necks.

The Perry Norwegian Lutheran Church basement, with its handy kitchen for women’s work, was a place of white sugar cubes, sweating glasses of water, and strong coffee made with a raw egg in the percolator to catch the grounds. When folks gathered for church dinners or funerals, ladies of the congregation heaped long cardboard-brown tables with deviled eggs, casseroles, buttered buns, lefse, large frosted cakes, and fruit pies. People chattered in English and Norwegian, lingered before going home to do farm chores. I always shot to Kristine’s side, putting my plate of food next to hers.

Down the road from the church was the Prairie-style parsonage, its backyard spilling into a serene garden-like cemetery and an alfalfa pasture. Built in 1919, the brick parsonage looked like a sturdy house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, with its broad white eaves, brown-red bricks, front gable over the full-length sun porch, and clusters of whiteframed windows. The Daleyville Cheese Factory functioned next door. A white barn—which we didn’t use—was near the pasture that previous pastors had been allowed to rent out for extra income. Ours was Perry’s third parsonage, the first being the clapboarded log cabin that the Abraham Jacobson family lived in at the time of the wicked tornado that killed a man in their yard. The second was stick-style, wooden.

Norwegian-American drama in the Perry Norwegian Lutheran Church parsonage was typical, partly because the Board of Trustees decided how to spend, or not spend, money on home repairs. Only after months of pleading by my parents did the trustees show up to check on a problematic toilet—my mother knelt while the trustees huddled together and watched it flush until it overflowed. Decaying kitchen floor tiles were ignored so long that Dad, without permission from the trustees, nailed the squares down for safety.

One morning, however, my weary mother received a surprise phone call from a trustee’s wife, who announced, “The men are coming to put down a new floor.” “When?” she asked. “In fifteen minutes.” Grumbling, the workmen had to pull out the new nails first, and then rip up the linoleum. As usual when in the repair mode, once the job was started, they worked at their whim—for a few hours every few weeks. Upstairs bathroom updates took three months.

I often sauntered out of the parsonage’s backyard a short distance to the grassy cemetery of sparkly granite and old marble stones. (I couldn’t visit Kristine every day and children my age were scarce.) Flanked by a cornfield and a half circle of spruce trees, the cemetery was my happy playground. The custodian, Helmer Grinder, mowed the grass and tossed out plastic flowers faded from too much sun. Discards made perfect bouquets for pretend weddings when I married an invisible groom, and for funerals I performed amidst thinleafed tiger lilies, cascades of fragrant peonies, and coral-pink clover.

When I learned to read, I differentiated between graves with life statistics etched in English and those in Norwegian. White marble markers used født for “born” and døde for “died.” If he wasn’t too busy and I asked him to, Helmer translated religious sentiments like “Hvor stor er dog den glaede, At man med Jesu maa. I herrens Tempel traede og i Hans forgaard staa.” (How great is my joy to know that we, together with Jesus, must enter the Lord’s temple and stand in His presence.)

Not afraid of the dead, I thought of them as people whose job it was to lie underground, peacefully in caskets. I zigzagged my way through the rows, careful not to step on Golis, Syftestads, Rundhaugs, Petersons, Lunds, and Jeglums. I picnicked with cereal and juice by the babies and children.

“When a child dies,” Helmer said, “it breaks your heart.” In Daleyville, I never attended real funerals, where death brings sorrow that a plate of homemade food served by ladies in the church basement cannot erase.

When I was young and thinking about people coming and going, Norway seemed to be a life choice: You either came from there, or you wanted to go there once more before you died, if you had enough money. But I never understood where “there” was. Or why people from Daleyville just didn’t move briefly to a place only a few miles away called Little Norway, with its sod-roofed and cedar-shingle-roofed houses, ceramic nisser hidden in trees, and the stave-church-like building from the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. My parents drove me there now and then.

On the outskirts of Blue Mounds, Little Norway was at the end of a narrow road canopied by branches and edged with tall grasses and slender Queen Anne’s lace. Stepping out of our car, I was drawn to women guides who flitted about in Norwegian national costumes—a simple red vest, black skirt,

In Norway, the prest, or Lutheran minister, wore clothing that was “fossilized” from the years after the Reformation. The ruff collar was once part of the European fashion for upperclass and official men, including ministers. The outfit of ruff (prestekrage or prestekrave), heavy black wool robe, and white surplice, traveled to America with the early Lutheran pastors. However, in America some (followers of Han Nielsen Hauge in particular) thought the minister’s garb distanced the minister from his congregation. Increasingly after about World War I, pastors conducted services in light-weight black robes, white surplices, and stoles in colors determined by the church season: for example, white or gold for Easter and Christmas, purple for Advent and Lent, and green for ordinary time.

Robe and ruff worn by Vilhelm Mortensen, ordained in 1882, who served in Chicago and Brooklyn. Vesterheim 1999.076.001 and .004—Gift of Eugene Mortensen.

white blouse adorned with a sølje, and silver-buckled black shoes. Dad often chatted with Olin Ruste, a kind-hearted tour guide whom I saw in church each Sunday. Did he, and the women who dressed similar to a doll I owned, live in Little Norway?

As I tried to sort out the location of the Old World, maybe, I reasoned, many adults I knew had moved to Daleyville from Little Norway. Maybe Little Norway was a section of Norway—but that made the Atlantic Ocean voyage part of the journey to the New World unclear. Geographical details outside of my sprawling two-and-a-half-story house and ribbon of a road were sketchy. The Norwegian-American farmstead—filled with Norwegian furniture and objects collected by members of the family that founded Daleyville— seemed like another rural Wisconsin village, not a museum with a modest admission fee.

Though Kristine was born near Daleyville in 1886, our across-the-street neighbors sailed to the United States from Norway. Like many immigrant girls, Anna Grundahl did housework for richer folks in Minneapolis before getting married. Twenty years older than Anna, her husband Thore was a farmer. Typical of Daleyville-area sets of siblings, Anna’s sister married Thore’s brother. Widowed in 1951, Anna moved to a newly built bungalow in Daleyville.

Robe, surplice, and stole worn by Orville M. Running, ordained in 1934, who served in Tacoma and Chicago. In 1946, he began a long career teaching Bible and art at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa.

Vesterheim 2006.022.001, .003, and .006—Gift of the family of Orville M. Running.

When nearly 70-year-old Anna needed to talk to my mother, or my mother needed to talk to her, they walked a few yards across the street to the other person’s house. Telephoning was long distance, because Anna was on the Hollandale party line and our family on Mt. Horeb’s. Whenever anyone used the phone, anyone on the line could pick it up and listen. One early morning, for instance, my mother called the pediatrician in Madison to consult about ear infections. Later, the phone rang two longs and a short and a woman who didn’t identify herself offered home-remedy advice.

Anna kept bits of Norwegian culture in her house. She grilled lefse on the old wood stove in her basement, even though the cheery kitchen was equipped with an electric stove. Anna rosemaled willowy leaves and flowers in a palette of gradated tints on wooden plates, and gave us a plate to hang on the wall: a tipped square of four-petal periwinkle flowers with black crosshatch centers. In fancy script she wrote “Spis min venn / Kom snart igjen” (Eat my friend / Come soon again) around the rim.

Tucked next to Anna’s little house was Tollef and Ella Brynjulfson’s modest wood-sided house. Tollef emigrated from Norway soon after an unnerving teenage rite of confirmation: The severe pastor lined up the children according to

During the first generations of Norwegian immigrants to America, rosemaling remained a dormant art. There may have been examples of rosemaling on the trunks, boxes, and bowls that immigrants carried with them, but almost no one continued to actively paint once they arrived in America.

It wasn’t until the middle of the twentieth century that rosemaling was revived as an active art form. Following the example of Per Lysne, an immigrant painter in Stoughton, Wisconsin, many Norwegian Americans tried rosemaling

flowers around them, from photos of historic painted pieces, and from the bright, cheery “smorgasbord plates” that Per Lysne made in quantity.

During the first decades of the rosemaling revival in America, there was little formal instruction and even fewer “rules.” Painters experimented with colors and designs, with techniques and materials. Most followed the Lysne style, which he had learned during his youth in the Sogn district of Norway. By the time Vesterheim began sponsoring classes and annual exhibitions in 1967, many talented painters had left an American stamp on this Norwegian tradition.

David

Bentwood box (tine), painted by M. E. Fadness, Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, 1972. Vesterheim 1982.084.001—Gift of Mrs. August Hackbarth and Elmer Fadness.

intelligence for public questioning. Tollef, who often strolled across the street to chat, told my mother that people in the Old Country never got to know their pastor, only seeing the aloof man of God at church services, or tending his vegetable garden. Contemplating his journey to America, Tollef never imagined he would be, in his old age, the friend of an American pastor and pastor’s wife. The day he had a heart attack, Tollef staggered to our front porch and lived.

When Tollef arrived in southern Dane County, he could speak only Norwegian. As a hired man on a farm, he attended a country school in a room full of little children to learn English. Eventually, he married Ella and they worked their own farm. When Tollef was in his seventies, my parents hired him to build a playhouse in our backyard, complete with windows and a front door to fend off mice. My mother thought Tollef and his co-worker Ole Stensby, who lived down a few houses from the Brynjulfsons, looked like nisser scurrying about with hammers, saws, tape measures, and jars of nails. Tollef and Ole conversed in Norwegian, but switched to English when my mother stopped by with cups of strong coffee. Their finished product—complete with shingled

roof—was perfect for tea parties with dolls. I swept it clean with a miniature broom.

By the time the Brynjulfsons moved from their farm into Daleyville, Ella was wheelchair-bound. As a young mother, she had contracted mumps, which left her with severe physical problems. As an old woman suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, she exercised her hands by mending bib overalls for relatives. She cross-stitched light-blue gingham aprons, using white embroidery thread.

Though the Brynjulfsons flew a small Norwegian flag each Syttende Mai and Norwegian words easily fell from people’s lips, Daleyville women of the 1950s and 1960s didn’t cling to ethnic clothing traditions. Ornate regional Norwegian bunader with exquisite embroidery, trim, and beadwork, like those that grace Vesterheim displays, were out of fashion. For everyday, Kristine, my mother, and other ladies wore shirtwaist, kneelength dresses cinched with matching fabric belts. Buttons were plastic, skirts billowy. With a low heel, shoes were practical black.

Sunday dresses were a bit fancier, at times with a silver sølje near the throat, and some women wore stoles. Occasionally after church, I was urged by fur-owners to snap open and

Aprons were standard dress for everyday in America, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with versions for women for everyday and dress, for children, and for men. Women’s dress aprons were usually white with some crochet or other lace trimming the hem or inserted toward the bottom. For everyday, many women wore aprons made of printed cotton, called calico, or of checkered woven cotton, called gingham. Gingham could be spruced up with cross-stitch embroidery. Depending on the thread color and whether the stitches were placed on the light, medium, or dark squares in the check, different decorative effects were achieved. The child’s apron is pinafore style providing maximum protection for an active girl.

Like the apron, a thimble is designed for protection, but also for facilitating needlework, such as sewing, quilting, or embroidery. Thimbles can be made from a variety of materials, but very often appear in metal. The little dimples, called knurling, help catch the back of the needle to push the sharp tip safely and easily through the fabric. Thimbles can be plain or decorative. For many people, thimbles symbolize the long tradition and skill of hand sewing

Thimble, silver and carnelian, Norway, mid-nineteenth century. Vesterheim 1991.083.002—Gift of Dr. Edith Borroff.

Thimble, early twentieth century. Vesterheim 1995.004.013—Gift of Laura Brye Aune.

Thimble, silver and glass, Norway, 1906. Vesterheim 1998.049.001— Gift of Lydia Ness Roberts.

Thimble, silver, circa 1900. Vesterheim 1994.069.033— Gift of Paul and Hermine Magnus.

closed the pointy mouths of the eerie fox heads and touch the thickly crocheted balls that hung near the animals’ ears. Wool sweaters for autumn and winter were American-made. Most people didn’t have the money to travel back to Norway to buy lovely hand-knit traditional sweaters associated with Norwegian Americans until the 1970s and beyond. As a toddler, though, I owned a just-my-size genuine Norwegian sweater, as well as a dainty circular sølje, rosemaled box, and souvenir bowls featuring painted girls wearing bunader: all gifts from Serena Holmes, a woman in my dad’s first congregation who visited her homeland.

Quilting wasn’t a Norwegian practice (in Norway people wove coverlets for beds), but many Norwegian-American women, including Kristine, embraced quilt making. Often she had a quilt stretched tightly on a wooden frame set up in her front parlor. Wearing a white sweater, she sat on a caneseat, straight-back chair, rolling and unrolling the quilt when she finished one section and couldn’t reach the unstitched cotton fabric. With one hand below the quilt, she kept the other on top with a thin needle between two fingers. Kristine wore silver thimbles on both middle fingers—one to push the needle down and the other to tap it back up.

On the floor under the quilt, I watched her needle flash in and out, noting the appearance of feather wreaths, swirling leaves, and crosshatch lines that looked like the gingham of Ella’s cross-stitched aprons. I didn’t know it then, but Kristine was paid to quilt, and her tiny uniform stitches were as identifiable as a signature. People brought her tops they had

pieced, or tops left undone by women who had died too soon. Sometimes Kristine made the entire quilt. At church basement charity auctions at Perry Lutheran, her quilts often brought the highest bids.

Kristine Goli’s splendid sewing and her care for me—the pastor’s daughter—was another place where tradition held strong at Perry. Clara Jacobson, the pastor’s daughter in Daleyville from 1868 to 1878, wrote sweetly in her memoirs about “Christine Goli, who was very proficient in all womanly arts, but especially in sewing.” That Christine, my Kristine’s relative, was a young single woman who helped Mrs. Jacobson sew dresses for Clara as Christmas presents, including one of “nice woolen material” and a “blue and black plaid dress, trimmed with black velveteen.” Christine was born in 1846 and died in 1900.

Like my Kristine, Christine, whose name is sometimes spelled Kjerstine in records, connected with the pastor’s family out of compassion and goodness. According to Clara Jacobson, “as the only daughter in a well-to-do family she [Christine] did not need to go out to work, so it was only through kindness that she spent so much time at the parsonage.” Clara remembered her Christine as a best companion for the pastor’s wife, partly because she made work seem “like play to them and the whole house resounded with merry laughter…. Even if Mother was very tired and worn she gathered new life and courage when Christine arrived.” Over handwork and other daily tasks, “Mother and she became fast friends and comrades who shared joys and sorrows with each other.”

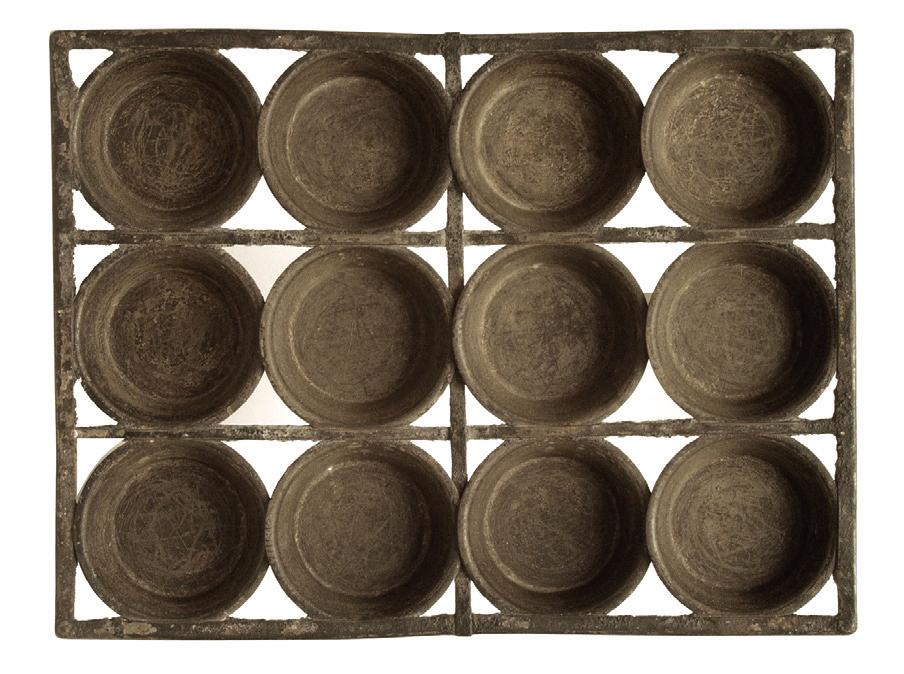

Baking traditional foods like lefse and krumkake requires special tools. Many immigrants brought these cooking tools from Norway. Others made new wooden tools in America. Even though kitchens and cooking methods have changed greatly over the past 150 years, many Norwegian Americans still prepare and enjoy lefse and krumkake

Lefse is usually made from a potato-based recipe. The dough is formed into large rounds, and rolled to its final thinness with a special grooved rolling pin. The lefse turner is a stick thin enough and long enough to slide under the round, move it to the cooking surface, flip one side to the other, and remove it to cool.

Krumkake is a crispy cookie that is baked in a flat, decorated iron, then rolled into a cone shape before it cools. The irons were long-handled in nineteenth-century Norway, when rural Norwegians cooked over open fireplaces. In America, stoves were used to cook and heat homes, and therefore new short-handled stove-top krumkake irons were produced and sold to Norwegian Americans. Today, electric versions are available. Despite these technological changes, the result is the same: a crispy, sweet cookie with elaborate pressed designs.

Lefse rolling pin, Norway, nineteenth century. Vesterheim 1984.121.001—Gift of Joan Hrachovina.

Lefse rolling pin, Aga, Hardanger, Norway. Vesterheim 1981.022.001—Gift of Betsy Jagersen.

Rolling cookie mold, Garlibakken, Valdres, Norway, 1950. Full and detail. Vesterheim 1978.056.001—Gift of Mrs. Charles Peterson.

Krumkake iron made for Andreas Elton, Dokka, Norway, circa 1850. Full and detail.

Vesterheim 1984.021.001—Gift of Ada M. Amundson.

Lefse turner, Leif Melgaard, Minneapolis, Minnesota, circa 1975. Vesterheim 1994.078.001—Gift of Ruth Johnson.

Muffin pan, Illinois, circa1870. Vesterheim 1980.102.001— Gift of Laura Hutchinson Davis.

Krumkake iron, Alfred Andreson & Co. Minneapolis, Minn. Vesterheim 1972.015.026— Gift of Marion and Lila Nelson.

Both ubiquitous bed coverings, one comes from rural Norway and one comes from rural America. Handwoven wool or wool and linen coverlets, called åklær, were made in several different weaving techniques. They were common in emigrants’ baggage to serve as bedding on board ship. In America they were usually replaced by pieced quilts made of store-bought cotton fabrics. Quilts could be utilitarian or highly decorative. Often some of the quiltmaking work would be shared among women who were relatives, friends, community members, or church members. Quiltmaking was also an important fundraising activity for rural Lutheran church Ladies Aid societies from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries.

Above, Quilt in flying-geese pattern, pieced by Mattie Powers of Clarinda, Iowa, circa 1870. Completed in 1917 by friends. Detail.

Vesterheim 1994.029.011—From the estate of Edna Dessery.

Left, Åkle (coverlet) in double-point krokbragd (boundweave), woven by Gjertrud Johanne Knudsen, Nesttun, Hordaland, Norway, circa 1880. Detail. Vesterheim 2005.024.001—Gift of Charlotte Offerdahl.

For a wedding gift in 1979, my Kristine gave me a friendship star quilt she pieced from scraps of misty blues and tangerines, creamy ivories and browns. The summer weather was so hot that she hand-tied with white yarn, five knots to a block—something I’d never seen her do when I sat under her quilt frame. Before, in the summers, she had always stitched with thread from a spool.

Though I loved the quilt, something didn’t seem quite right. In my mid-twenties, I needed Kristine’s hand stitching; if I didn’t own some tiny stitches done by soft hands that often held mine, it seemed I would lose her, lose my childhood. A year later, when she was in her mid-nineties, I mailed her my first quilt top, frantically made in Seattle on a new Viking sewing machine. Kristine hand-stitched that flying geese quilt I pieced of cotton calicos in shades of red and purple. She thought it would be her last one before she died, but it wasn’t.

While I was living a carefree childhood in southern Wisconsin, my dad won the trust of the Perry congregation and skillfully guided congregational leaders to come closer to agreeing on the decisions about the new educational unit. In the midst of this, he led the factions through discussions about whether or not to drop the yearly reporting of the names of people and amount of money they gave as offerings, for all connected with Perry Lutheran to read. After much fussing, the trustees decided to publish just the envelope number and the amount. Not too many years earlier, the Norwegian tradition of assessing each parishioner a specific amount— widows were to pay two dollars per year—for the offering was still in practice.

Old church records were written in Norwegian script. Often people nearing Social-Security-benefits age came to my dad to secure copies of their baptismal records as proof

of identity. This required detective work. They didn’t have birth certificates and were often surprised to learn they were baptized with a last name that they never knew about. Names of immigrant families in the Daleyville area could change as easily as putting on a new pair of overalls. For example, some of the Daleys of Daleyville spelled their last name Dahle. The Grenders were children of the Grinders. Adolph Peterson (who lived in Kristine’s childhood house) changed his name to Peter Olson and moved to Minnesota.

My mother—the unpaid assistant to the pastor who also was trying to figure out who was related to whom—proofread bulletins, offered tactics for success in a community descended from the state-supported church of Norway, and cleaned the turn-of-the-nineteenth-century parsonage. With 60 windows to shine, original woodwork to dust, a mirrored built-in buffet to de-clutter, a sunroom to sweep, and enough cupboards for a huge farm family, she had plenty of housework. Her mothering duties increased, too, with the arrival of my brother and sister. My overworked parents gratefully accepted Kristine’s frequent invitations for me to keep her company until I was eight.

In the summer of 1964, when Kristine was 78, the district president of the by-then American Lutheran Church (the parent organization to which Perry belonged) suggested to another Wisconsin congregation—German in ethnicity—that my father would be a good pastor for them. They needed someone to guide their factions to build a new educational wing and my father had been successful with Perry.

Suddenly, our family took a road trip that didn’t end in Mt. Horeb at Olson’s Restaurant for thick chocolate malts, or in Madison at Stassi’s Shoe Store. The unfamiliar town we visited had a confusing number of streets. The population of two-thousand-plus listed on a sign at the edge of town seemed

unmanageable. Their parsonage was a small ranch-style onestory. Their cemetery was far from the church, out of sight. Even a downtown with more than one store wasn’t appealing. The Sunday morning my father announced to the Perry Norwegian Lutherans that he had accepted another congregation’s call, I sat in the balcony in the soprano section of the senior choir with my mother, close to the organ. Over her maroon robe Kristine wore a beaded necklace, ambercolored, from her magical jewelry box. Usually she trumpeted the last hymn as soon as my father announced the page number after the benediction. That morning she paused. She was crying. After the postlude, I asked her what was wrong. She held me close, saying I was too young to understand. I’d understand later, she said.

In Vesterheim, surrounded by church quilts hung on walls, lefse rolling pins, and rosemaled kubbestoler, a woman pushes back her tumbling hair with a plastic headband. She is making better sense of her Norwegian-American story. Her details from the 1950s and 1960s mix well with the phenomena of brave immigrants finding their way in a New World 100 years earlier.

It’s as if her Daleyville friends and life are just around the corner, even though the granite marker of her best NorwegianAmerican friend reads, “Kristine O. Goli / 1886 – 1985” and is decorated with patches of lichens.

The place in which she finds herself is a fiercely ethnic museum. In it, Norwegian immigrant culture is preserved and interpreted for the visiting woman and her two sweet daughters, who stand with her before lighted cases, looking at a collection of cascading søljer that shimmer like creek water in sunlight.

It’s 2007.

Rachel Faldet is assistant professor of English at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa. Her essays have appeared in The Carolina Quarterly, The Christian Science Monitor, Iowa Woman, Tapestry, and Wapsipinicon Almanac. Editor of Our Stories of Miscarriage, she was a guest on NBC’s Today show. She wears sølje earrings for everyday.

Paul Andersen, Sarah Andersen, and Kristin Brue helped with oral history and facts. Visiting Daleyville, Perry Norwegian Lutheran Church and cemetery, the Perry Historical Center, and Little Norway verified memories and history.

Reading The Historical Perry Norwegian Settlement, published by the Perry Historical Center in 1994, was invaluable. Detailing Daleyville and surrounding area history, the book includes lists of houses and their families through time.

Settlers of Dane County: The Photographs of Andreas Larsen Dahl by David Mandel (Dane County Cultural Affairs Commission, 1985) and Sixty Years of Perry Congregation compiled and edited by C. O. Ruste (1915) were useful.

Clara Jacobson was another pastor’s daughter who loved the cemetery and was afraid of julebukker. Connecting with her through her writings about her girlhood in Daleyville was like making a friend. Longhand, typed, and published versions of Clara’s memoirs are housed in Vesterheim’s library. “Childhood Memories” was written in 1943 when Clara was eighty years old. “Memories from Perry Parsonage” appeared in Symra in 1911 under the title “Minder fra Perry Prestegard.” It was revised for Norwegian-American Studies and Records, Volume XIV, published in 1944 by the Norwegian-American Historical Association.

Jennifer Kovarik, Laurann Gilbertson, and David Faldet offered assistance as I reclaimed my Daleyville home.