motifs,

nineteenth or early twentieth century.

motifs,

nineteenth or early twentieth century.

From the earliest times, symbols embellished textiles, giving them great beauty and conveying meaning. This was particularly true when, as was common, textiles were made and used for rituals.

The symbols might be woven directly into the cloth as it was made, or added later by embroidery, or printed with wooden stamps. Woven tapestry was more common in Viking times, and embroidery was more popular in later periods.

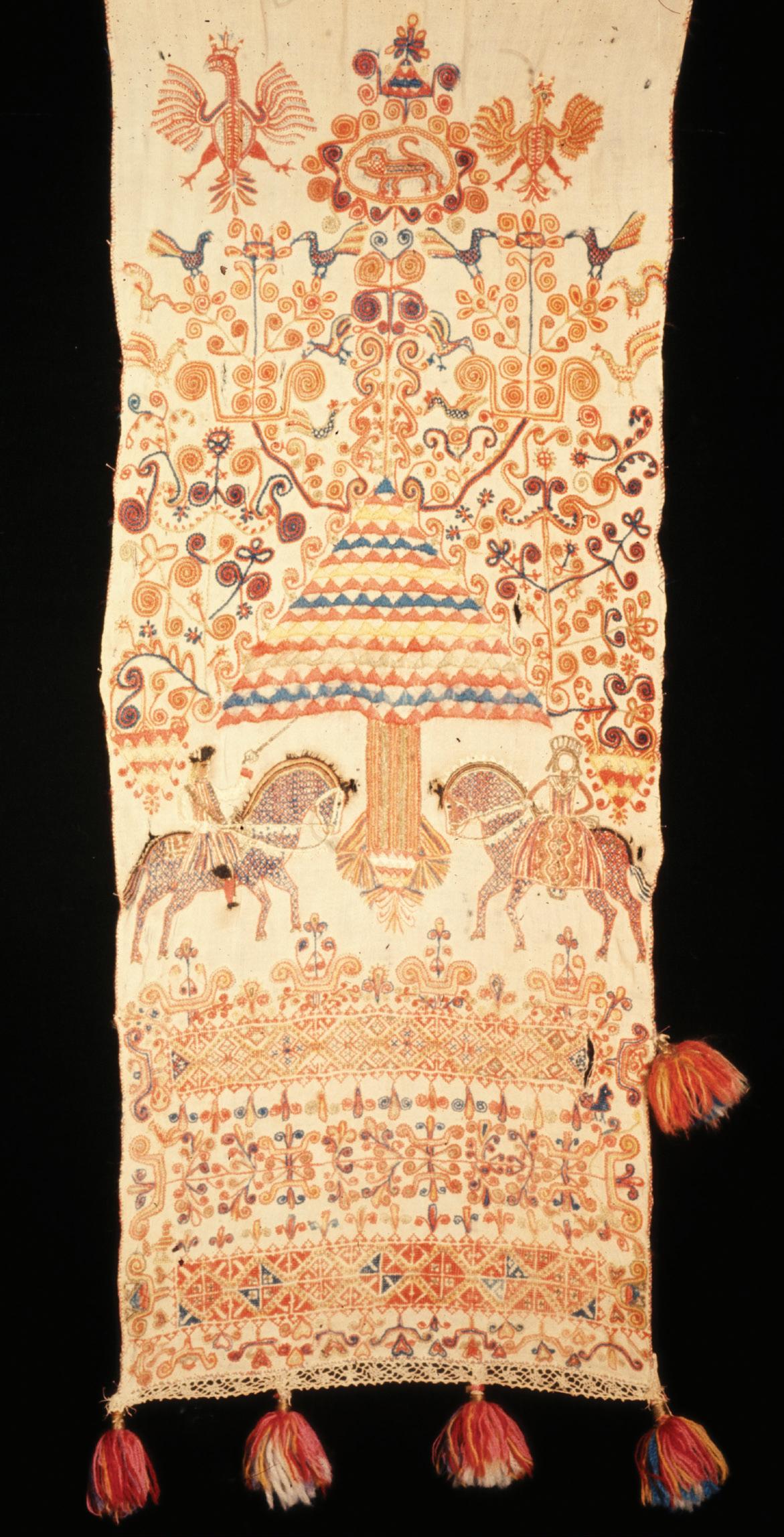

In Viking times, symbols that were already millennia old were woven or embroidered on cloths used in ceremonies. It is easy to see these symbols on the Oseberg tapestry and other textiles that were remarkably preserved in a Viking ship found in 1904 near Tønsberg in Vestfold County. The Oseberg ship was built between 815 and 820 C.E. Parts of the Oseberg tapestry portrays processions, offerings of textiles with symbolic designs, and symbols marking people, animals, and buildings. People are also dressed in ceremonial attire and shown conducting a ritual. A thousand years later, many of the same symbols were used on nineteenth-century ceremonial cloths in Norway and elsewhere in northern Europe. This is certainly a testament to the tuition and dedicated conservation of the women who made them.

The exhibition Sacred Symbols, Ceremonial Cloth, on view at Vesterheim through February 21, 2010, focuses on symbols found on Norwegian textiles before the arrival of Christianity and appearing well into the nineteenth century. The exhibition showcases precious Norwegian textiles, both from Vesterheim’s collection and on loan from Telemark Museum and private collections, and explains their symbols and use in

Found aboard a Viking ship buried under a mound near the Oslofjord, the tapestry dates from 834 C.E. On the ship were the skeletal remains of two women and everything they would need for the afterlife: food, chests, beds, transportation (horses, cart, and sleighs), agricultural and household tools, shoes, and textiles. Everything was well preserved by the thick layer of blue clay under the ship. Some believe that the older woman is Queen Åsa of Agder, grandmother of King Harald Fairhair, and the younger woman her servant. Others believe they are priestesses or weavers.

The tapestry was woven in soumak, or brocade, with wool and linen yarns on a warp-weighted loom. It is only 6.25 to 9 inches wide. The length is unknown because the textile is fragmented. In now-faded colors, the tapestry displays a combination of symbolic and narrative imagery. Some of the tiny figures hold symbols in their hands, while others wear symbolic clothing, headdresses, or masks. Solar and seasonal symbols, trees of life, ships, and shrines are depicted. Horses pull ceremonial carts piled high with decorated textiles, and people clothed in similarly-patterned clothing walk alongside on their way to offer the gifts to the deities. The scenes are divided by trees of life and bordered by zigzag patterns. The tapestry is in the collection of the University Museum of Cultural Heritage and housed at the Viking Ship Museum on Bygdøy, Oslo, Norway.

family and community celebrations. Alongside these, artifacts from Vesterheim’s collections in metal, wood, and bone extend the theme.

The Good and the Holy

Some of the oldest symbols used in textiles represent the sun—swirling and concentric solar circles, rosettes, sun-like flowers, and star-like swastikas that whirl both left and right (figure 1). The Vesterheim logo has such a symbol. Solar worship came to Scandinavia with trade in the early Bronze Age from the Mediterranean world. Scholars Kristian Kristiansen and Thomas Larsson trace this image along the Danube River and up into the Danish islands in the graves of priestesses of the sun, who wore large bronze circular disks on their abdomens (see “Further Reading” at the end of this article). Later, these large disks can be seen worn by ladies on the Oseberg tapestry. Round brooches are still worn with the Norwegian bunad (festive folk costume). Traditional bridal crowns were often decorated with solar symbols, too.

During all of this time, the hakkekors or swastika symbol was associated with holiness and goodness. The swastika appears many times on the Oseberg tapestry in connection with praying people. Even when the Oseberg tapestry was discovered in the early twentieth century, the old meaning was familiar to Professor Gabriel Gustavson, who excavated it. The swastika symbol, one of the oldest signs of the seasonal rotation, now has more negative connotations after it was coopted by the Nazis in the mid-twentieth century.

Solar symbols are represented in the nineteenth century on large ceremonial cloths, on carved and painted wooden objects, and on jewelry. One ceremonial cloth shows a goddess holding trees of life between golden suns (figure 2).

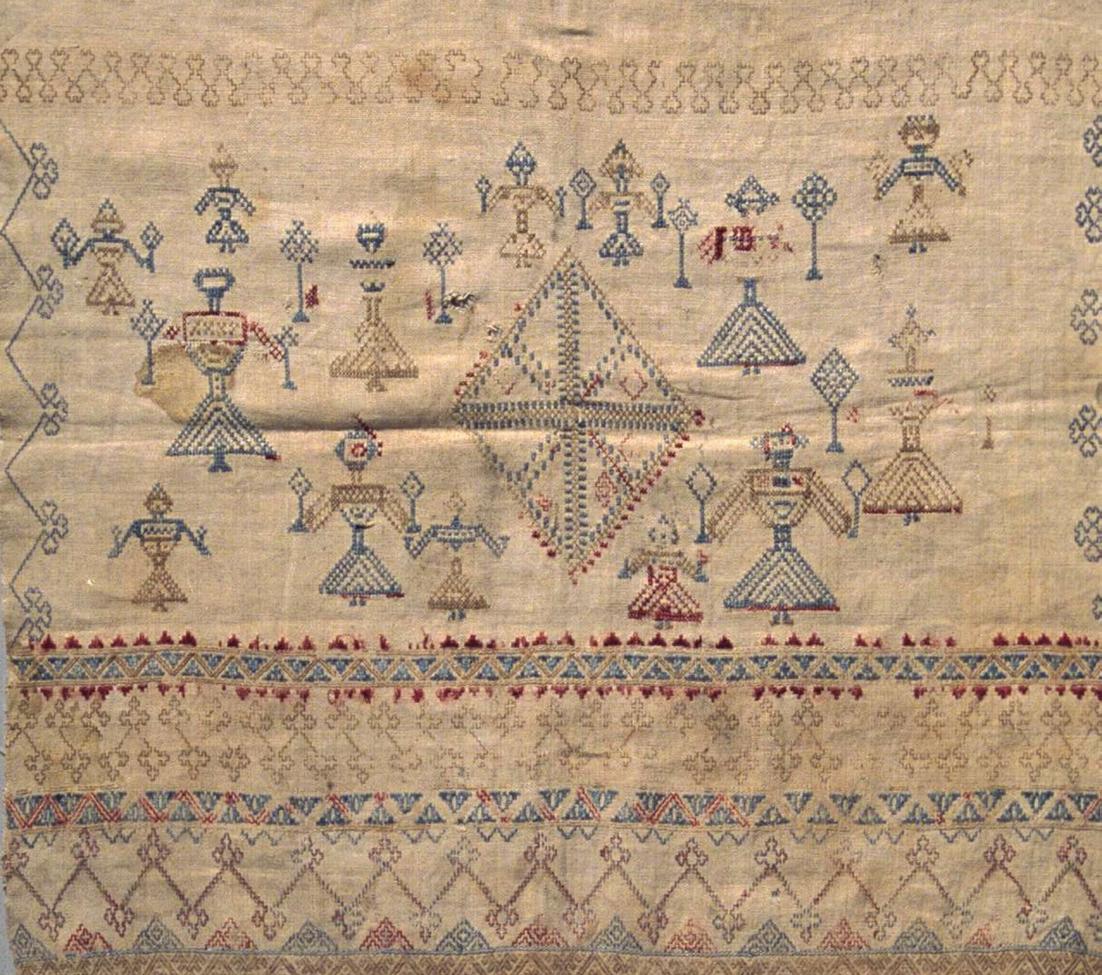

Next, the exhibition focuses on fertility symbols for wedding ceremonies. In many cases, the bride created these textiles herself, embroidering fertility symbols onto her belt

cloths and on cloths for her groom. These symbols, many from the Neolithic period, appear on the Oseberg tapestry as well, but in the nineteenth century they were represented on wedding garments and on textiles displayed during the wedding ceremony. Many of the large ceremonial cloths from the area around Oslo show large female deities holding up hooked rhombic forms, the age-old symbol of the womb (figure 3). Other females hold the “fertile field” symbol, a quartered rhomb with four seeds in the quadrants (figure 4).

As many as 14 different female figures may hold up these rhombic forms (figure 5).

As we look at these ritual textiles, we may wonder whom the female figures represented. Unfortunately, unlike in other countries in the north, no information was collected in Norway to assist us in identification. We see that they are not ordinary females, nor are they identified by name. They appear in rituals, but not church rituals. They do not appear to be Christian, although those who embroidered them certainly must have been. In their pose, their color, and their accompanying symbols, they are similar to other north Russian and Ugric goddesses, who are crowned, have upraised arms, and hold trees of life or other abstract fertility symbols. Thus we may posit that they represent a female deity. However,

Figure 6: Carved printing block (skinnfellrose) with spiral motifs. Hallingdal, Norway, nineteenth century. Vesterheim 1995.004.015—Gift of Laura Brye Aune.

in contrast to the single deity we so often see on other northern ritual cloths, in Norway many deities are portrayed in multiples as in figure 5. Thus we must look to specifically Norse mythology for answers.

A tentative answer presents itself when we read about the pre-Christian goddesses of the Vikings, particularly the oldest class of them, the disir. Hilda Davidson explains that general belief held that “the disir were family and guardian spirits, closely associated with particular localities, to whom sacrifices were made for luck, or for fertility of the land and those owning it. Thus, at the highest level, they were connected with the royal dynasty.”1 She also says that “the northern goddesses were not specialists and cannot be seen as individual divinities who concentrate on one particular side of life or activity . . . they were special guardians of women of the household, linked with their families over the generations . . . the goddess is linked with successive turning points in a woman’s life, menstruation, marriage, childbirth, and menopause, all marked as significant events in the relationship of the goddess with the women of the household.”2

Even up to the early nineteenth century, when researchers were collecting data in the mountains of Telemark, they noted that offerings were given to local non-Christian deities by both men and women, who may have believed that “yet not all the disir have gone.”3 It is possible that, given this close relationship to household spirits, women memorialized this closeness on the distinctive ritual cloths they embroidered for their special family feasts.

Other cloths made for fertility depicted horned headdresses on the goddesses, horned animals, and reciprocal spirals called ‘ram’s horns,’ to encourage male potency. On the groom’s cloth, the bride might also embroider a horned deer. We occasionally see horned deer on women’s belt cloths, too. The spiral wooden stamps used for decorating sheepskin coverlets also incorporate these heart-shaped spirals. They, too, stand for fertility (figure 6).

Fertility symbols were most common on the large ceremonial cloths made in eighteenth and nineteenth century Norway to hang behind the high seat of the farmstead at festive times like Christmas and especially at weddings (figure 7). The bride and groom took their seats in front of these cloths during the wedding ceremony. Dressed in clothing and jewelry that covered them with symbols of fertility, they embodied the concept, not only of their own personal fertility, but, to an extent, the fertility of the fields and the farm animals surrounding them. This section of the exhibition features ceremonial hangings, bridal belt cloths, cloths for the groom’s hat and neck, and other textiles (figure 8). Wooden

Figure 7: High seat cloth (høgsetebrudeduk) made by Birgit Augundsdatter Håtveit (1774-1805) for use when she and Hans Hanson Askild (1767-1810) married in 1792, Bø, Telemark, Norway. NF.2001-0006B, Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo, Norway. A reproduction of this textile, made by Helga Bergstrom, Sauherad, Telemark, Norway, will be part of the exhibition

Access to the Divine and the “Other” World

The final group of symbols in the exhibition relates to end-of-life ceremonies. At death, another group of cloths facilitated the transition into the next world. Signs that appear on textiles from the Oseberg burial are still woven or embroidered onto the likkross towels that are arranged in the shape of a cross over the coffin. On the coverlet draped below them is a small woven equal-armed cross at the center, and it is on this symbol that the lighted candle is placed.

The equal-armed cross is not the Christian cross, as some might suppose. Many symbols were adopted by newer religions after the fall of Viking society, but we can easily see that the equal armed cross (figure 11) was part of the pre-Christian world’s symbolic vocabulary on the Oseberg textiles—having as its meaning the crossroads.5 This special place represented not only the roads to the points of the compass—north, east south and west—but additionally to the upper world and to the underworld. Thus, shamans and priestesses, or volva, in Viking times approached the crossroads in order to access the spirit world beyond our own. It is this world that is represented

chests to hold wedding textiles, carved boxes and stamps for sheepskin coverlets, and bowls for the wedding feasts are all assembled in this section of the exhibition.

If this display of fertility symbols proved effective, new life would soon be growing under the bride’s belt cloths, and it was time for another set of symbols, those protecting her and her new child, most commonly seen on kinnlag, or christening cloths. In the nineteenth century, the baby was swathed with bands of symbols to ward off harm until the christening. These included symbols that whirled in opposite directions, such as left- and right-whirling swastikas and letters that stood for opposites, such as S and Z, (which were also familiar to women who spun yarn in S and Z twists). Other chains of motifs included the zigzag, often seen around the edges of clothing as protection, or chains of goddesses united by their zigzag skirts. Protective symbols, displayed on wood objects as well as textiles, show knots and locks, common from Viking times. As on the Oseberg tapestry, we see the valknut, Olavsknut, and mara lock (figure 9) woven onto the offered textiles, held in the hands of people, or carved on wooden items. According to research done among older Norwegians in the 1920s, who remembered these symbols as having specific protective powers, these protective signs still had power in the twentieth century.4

In the section of the exhibition focusing on protective symbols, one can see cloths to protect the mother and baby, blouses with zigzag designs on the breast (figure 10), a special cap made for the baby with protective designs, and the S/Z design of the christening wrap. Antique sheepskin coverlets with protective and fertility-enhancing designs hidden in their folds covered the bed. Carvings on wooden trunks and boxes show the knot and lock motifs that protected their contents, as well as larger symbols once carved on barns and granaries to protect animals and crops. The large containers of strengthening food brought by friends to the mother in her confinement were marked with similar designs.

Figure 11: Equal-armed cross from an embroidered basket cloth (sendingsklede), Telemark, Norway. Embroidered date of 1733. SM.0633, Telemark Museum, Skien, Norway

nineteenth century. The burial mound was the site of offerings of food, and the ancestors sometimes appeared to family members who had ‘second sight.’

This transition from our world to the ‘other’ world is represented by other age-old symbols. The tree of life, with its roots in the earth and its branches in the heavens, is a good example (figure 12). An embroidered baptismal wrap (figure 13)shows men and women in the branches of a large tree of life. The figure of the goddess with upraised arms, but with her feet on the earth, is another symbol that bridges the two worlds. Horses with solar riders are also sometimes seen as embodiments of the trip into the other world of the dead.

Also featured in this section of the exhibition are large hangings with tree-of-life and equal-armed-cross designs woven or embroidered on them. In the exhibition, likkross cloths are set up on a coffin so it is possible to understand how they were arranged. Museum collections contain textiles with equal-armed crosses and deities holding trees of life or standing beside trees. Similar motifs are also carved in wood.

Figure 13: Baptismal wrap (kinnlag), Norway. NF.1992-1969, Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo, Norway.

12: Groom’s belt cloth (belteklut), Telemark, Norway. NF.1915-0822, Norsk Folkemuseum, Oslo, Norway.

The many pre-Christian symbols that have come down into our world on textiles and other folk art are a precious heritage. They were a vital part of nineteenth-century agricultural life and were greatly needed for all events of the life of the farm and its inhabitants. Knowledge of their meaning was still available in the early twentieth century and even today the age-old symbols are occasionally woven or embroidered on cloth (figure 14). That they survived so long is a testament to their necessity in folk society and to the craftspeople who repeated them over and over on the items they used for rituals of protection and fertility.

1 H. R. Ellis Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1988), 113.

2 H. R. Ellis Davidson, Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe (London: Routledge, 1998), 185.

3 Hans Ellekilde and Axel Olrik, Nordens gudeverden, Vol. I. (Copenhagen: Gads Forlag, 1926), 324.

4 Andreas Mørch, “De svidde på tre,” Under Norefell, 4(1), 1988, 26.

5 Mikkel B. Tin, De første formene: Folkekunstens abstrakte formspråk (Oslo: Novus, 2007), 292.

Further Reading

Christensen, Arne Emil, Anne Stine Ingstad, and Bjørn Myhre. Osebergdronningens grav, vår arkeologiske nasjonalskatt i nytt lys. Oslo: Schibsted Forlag, 1992.

Christensen, Arne Emil and Margareta Nockert, eds. Osebergfunnet, Bind IV Tekstilene. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Universitetet i Oslo, 2006.

Kelly, Mary B. Goddess Embroideries of the Northland. Hilton Head, SC: Studiobooks, 2007.

Kostveit, Åsta. Kross i kake, skurd i tre. Oslo: Landsbruksforlaget, 1997.

Kristiansen, Kristian and Thomas Larsson. The Rise of Bronze Age Society: Travels, Transmissions and Transformations London: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Figure 14: Betty Rikansrud Nelson, Decorah, Iowa, Norse Goddesses wall hanging in doubleweave pickup, wool on wool, 2009.

About the Author

Sacred Symbols, Ceremonial Cloth

is made possible through the generosity of Humanities Iowa and the National Endowment for the Humanities

The Royal Norwegian Embassy

Kate Nelson Rattenborg with matching funds from Thrivent Financial for Lutherans

John and Veronna Capone

Paul and Carol Hasvold

T. Eileen Russell

Jane Y. Connett

Carol O. and Darold Johnson

Mary B. Kelly is guest curator of the exhibition Sacred Symbols, Ceremonial Cloth, on view at Vesterheim through February 21, 2010. As a researcher at Norsk Folkemuseum in Oslo in 2005, she became interested in the Norwegian ceremonial cloths that were recently transferred to the museum from a collection in Sweden. Kelly has documented symbols on European folk art for 30 years, producing a trilogy of books on Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and Greece, and most recently on the countries of North Europe. She also writes for textile publications such as Fiber Arts, Piecework, and Needle Arts. She was professor of art at Tompkins-Cortland Community College from 1973 to 2000. Kelly lives in Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, where she maintains a weaving and painting studio. Visit her online at www.marykellystudio.homestead.com.