From the Autobiography of Ole G. Felland

Edited by Jeff M. Sauve

Ole G. Felland, An Introduction

Professor Ole Gunderson Felland was born October 10, 1853, in Koshkonong, Dane County, Wisconsin. His parents, Gunder G. and Tone Felland, married in 1844 and emigrated from Norway with one child and seven other family members in 1846 on a vessel named The George Washington. They arrived by oxen in Koshkonong on August 11, 1846.1 Ole Felland was the fifth of nine children born to the couple.

In the book, American Lutheran Biographies published in 1890, Felland contributed a sketch of his early life (referring to himself in the third person):

The parents took great pains to give their children a good education, and Ole attended both the parochial school and the common school, whenever they could be reached. Being of a puny size, he was not much of an account on the farm, and as he evinced desire and aptitude for learning, his parents sent him, at age 14 years of age, to Decorah, Iowa, to attend Luther College.2

Felland dedicated his life to the pursuit of knowledge and affirmation of faith. After graduating from Luther College in 1874, Felland continued at Northwestern University, Watertown, Wisconsin, where he received his master of arts degree in 1876. In 1879 he completed his theology degree at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri, and accepted a call at Kasson and later Hayfield, Minnesota.

In 1881, the fledgling St. Olaf’s School, now St. Olaf College, called Felland to serve as an instructor. During that time, Felland married Thea Midboe in 1883. Six children were born to this union. Together, the couple served as the resident heads for Ladies’ Hall until their home, affectionately called “Heimro” meaning “house of peace,” was built in 1901. Unfortunately, their time of bliss was shortened when Thea became ill in 1905 and passed away.

As an earlier pioneer of the school, Felland influenced an entire generation of students, teaching chiefly the classical languages. To his credit, Felland developed the college library from a scant 700 volumes to a collection of more than 26,000 volumes 35 years later. In addition to his contributions as a teacher and librarian, Felland enjoyed several hobbies, including gardening and photography. His photography collection, widely used today, comprises nearly 2,000 images that document nearly 40 years of the college’s development along with that of Dane County and local environs.

O.G. Felland, 1906. Courtesy of St. Olaf College Archives.

Retiring in 1928, Felland spent the winter months living with his two daughters who resided in New York City. Shortly before his retirement and concluding eight years later in 1935, Felland devoted his energies to writing an autobiography. The manuscript, long held in the St. Olaf College Archives, has remained up to this point unpublished and rarely referenced. The following passages illustrate a man who was described at the time of his funeral in 1938 as “. . . a gentleman of the old school, cultured, dignified, broadminded, and tolerant, but also affable, friendly, and interested in the welfare of all young men and women who through the long years came under his influence.”3

These passages are primarily excerpted from the second chapter of O.G. Felland’s unpublished autobiography, “Early Education,” (written between January 18, 1933, and March 31, 1934). Felland tells his childhood recollections with clarity and richness in detail, peppered with anecdotes illustrating his family life as well as his Koshkonong neighbors and teachers. Spelling, punctuation, and grammatical conventions are Felland’s own.

Early Education

In the year of my birth the Norwegian Synod was founded and that was really the beginning of organized educational work among our people. And the only educational work that we knew of was the Norwegian. English language was a foreign language, and American was at a low stand in southern Wisconsin.4

There were not schools in the settlement in those early days and my parents were also our first teachers. A district school house had been built before my time, but even as late as when I began to go to school it was kept only 2 or 3 months a year, and the Norwegian settlers simply ignored it for some years. They had their own parochial school, taught by a Danish teacher by the name of Jens Jensen Aggerholm.5 But before I went to his school I had already mastered the ABC, which I learned at home before I was three years old, watching and listening to mother while she was helping my older brother Olaf with his lessons.6

The primer which I used had been published by our minister, Rev. A.C. Preus. It contained the alphabet and easy exercises and on the last page a picture of a crowing cock, underneath which was the following verse;

Naar Hanen glad of munter galer

I Dagningen hver Morgenstund

Til Born den ligesom da taler

At Morgenstund har Guld i Mund.7

Among the word exercises I remember distinctly this phenomenon: Tetotalafholdenhedsselskaberne, which I firmly

believed to be the longest word in the world, and when I had mastered it, I must have felt that there was not much more to learn. The illusion dimmed and finally vanished.

My first day at school was in a log house on a farm that father had bought nearly half a mile north of our home, called Holstad, then occupied by a tenant. It was the first day of a new term, and there were several other children who entered school for the first time, among which I remember especially one by the name of [Knut] Martin Olsen Teigen, who was about the same age as myself. He was an unusually bright boy and we were school mates for several years. He afterwards studied, became a minister, then studied medicine and became a doctor. He also had literary interests, wrote poetry and narrative prose.8

As indicated, school was kept in private homes (Omgangsskole), about a week in each home.9 There would be about 15 to 20 children present, seated around a table on boards placed on chairs or boxes. School began at 8 o’clock and lasted till 5, with an hour intermission for dinner, which was brought along from home and eaten on the premises. In this way we traveled from farm to farm, the most distant about two miles from my home.

We had an uncle and an aunt living about two miles west, and when the time school was in their neighborhood, we and our cousins, Uncle Vetli’s children, used to live with them for a couple of weeks, I and my sister usually with Uncle Ole, and our cousins at Aunt Sigrid’s, and when the school was in our neighborhood, these cousins would in turn live with us, Uncle Ole’s at my home and Aunt Sigrid’s at Uncle Vetli’s. Thus we came to feel as though we were all one big family.

Our work consisted in religious instruction, to which usually the morning sessions were assigned. Our text books were Luther’s Small Catechism and Dr. Pontoppidan’s Explanation, in which a daily lesson was assigned, to be committed to memory at home, and when a little advanced we took up Bible History, in my earliest years, [W.A.] Wexels. This was also memorized and when those books were finished it was time to take them up again. These same books were also used by the minister in preparation for Confirmation, which usually began in September and continued with weekly meetings until the Confirmation between Easter and Pentecost.

The afternoon session was generally devoted to writing, arithmetic, sight reading. etc. Writing was at first taught by means of a slate on which the teacher wrote the letters or words to be copied by the pupils. More advanced pupils used pen and ink in copying a line which the teacher wrote at the top of the page. Aggerholm was a good penman.

In arithmetic no textbook was used by the pupils, but the teacher had a textbook from which he copied or dictated a problem on our slates, and when we had worked them out, he would look them over and show us our mistakes, if any, and assign a new problem. In this way we were taught to add, subtract, multiply and divide both integrals and fractions.

In sight reading we had no textbook and I used a copy of the New Testament which had two columns on each page, one in English and one in Norwegian, and in this way I read through some of the Gospels and the Acts.10

ABCs of School Life

During these years from the age of 4 to 14 I attended these parochial schools very regularly, and on the average about 5-6 months every year. In my sixth year I began to attend our district school [common school] and learn English, although I had a sort of speaking knowledge of it.11 At any rate it did not take me long to master the primer and first reader. I can not recollect the name of my first teacher in English. We generally had a new teacher each new term and the only ones whose names now occur to me are, Louise P. Ordavy, John Lee Fuller, Ole Moe, and Guro Ingebretson.

Miss Ordavy taught one summer term either 1862 or 1863. As I remember her, she must have been interested in Geography. I got my first lessons in map drawing from her, and she also taught us much local geography, how Wisconsin was bounded, how Dane county was bounded, the names of the townships in Dane county, how Pleasant Springs, (our township) was bounded etc. These lessons were repeated every day by the whole school in concert, and there was generally a race to see who could get to the goal first and end it loudest.

I was at a disadvantage because I had entered late on account of having been sick. I got along tolerably well with the boundaries, but when it came to the enumeration of the long list of townships of Dane county I lost track. Miss Ordavy noticed this and volunteered to give me private lessons if I would stop over after school. We agreed and it did not take me long to master the list of 50 or 60 names beginning with Albion, Berry etc. and ending with Westport and York.

That first lesson in map drawing was different. Miss Ordavy placed an outline map before me and asked me to copy it. I said I couldn’t. She said: Oh, just try! I said: I won’t! She said: You stay after school, I’ll show you. I stayed and she helped me, we both wept copiously, finished the map drawing.

She washed away the tears from my eyes (and her own, too) and we parted as friends.

The following summer we had a new teacher, but Miss Ordavy called one day at Fuller’s where she had boarded while teaching. Elbert Fuller, one of the sons, told me that she was there and suggested that we ask the teacher for permission to get a pail of water for the school house. This was granted. When we came to the house we walked right in through the open door, and Miss Ordavy recognized me and exclaiming: Oh, my little friend Ole! She embraced and kissed me. Of course I felt very cheap and awkward and struggled to get away, but I have long since forgiven her the liberty she took.

John Lee Fuller was the oldest son of the farmer Fuller above referred to. He had formerly attended the same district school as an advanced student in mathematics, and after a short course at some academy been hired to teach during the winter term, when there was no work on the farm, and hence many of the older boys availed themselves of the opportunity. Discipline was rather difficult, but Mr. Fuller was determined to maintain it at any cost with ferule, switch and rod.

About 1864, we got a new teacher by the name of Ole Moe. He was a newcomer from the southern part of Norway, probably Jaderen or Agder, and spoke that dialect. He also served as Precentor in the West Koshkonong church for many years and was held in high esteem as such. Pretty much the same textbooks and methods were used by him as by Aggerholm, except the arithmetic, but by that time arithmetic was taught in the public schools, and I have no distinct recollections of his teaching. I remember he made us memorize hymns from our hymn book, we used Guldberg’s [Salmebog] at that time.

The fourth teacher mentioned, Miss Guro Ingebretson, was the daughter of a Norwegian farmer living about a mile east of Stoughton, who belonged to our church. I was then in the highest class, the fifth reader (McGuffey) and studying English grammar [W.C. Kenyon’s Elements of English Grammar]. She was very mild and gentle in her ways and was a great favorite with all. It was the time when we had just got a new assistant pastor by the name of J.D. Jacobson. He and Miss Ingebretson became acquainted, engaged, and soon married. He was soon after called as professor at Luther College where he later became my teacher, and I may again come to refer to him and his wife.

Preparing for Luther College

It was either that summer or the previous one [1866 or 1867] that father engaged a student from Norway by the name of Victor Neuberg as a private teacher for me and my younger brother and sisters.12 We met daily in my parent’s bedroom. I studied chiefly Universal History, using a Norwegian text book, besides arithmetic, geography etc. this course lasted about six weeks. I may not have gotten much out of this course, but it shows that my parents were interested in the education of their children, going even to the expense of a private teacher for our sole benefit.

In the fall of 1867 I entered the confirmation class of Rev. [Jacob] Otteson and attended pretty regularly once a week. We met at the parsonage in a room in the basement, which had been set aside for that purpose, and I had a chance to review the books which I had been learning in the parochial schools for the last 9-10 years. These hours of instruction our pastor knew how to make extremely interesting. Rev. Otteson was not only an able, learned and pious minister, but also endowed with rare sense of humor and wit and could mimic and satirize the stupidities and folly of ignorant youth. In the following spring I was too young for confirmation, and decided to take advantage of another year at his feet.

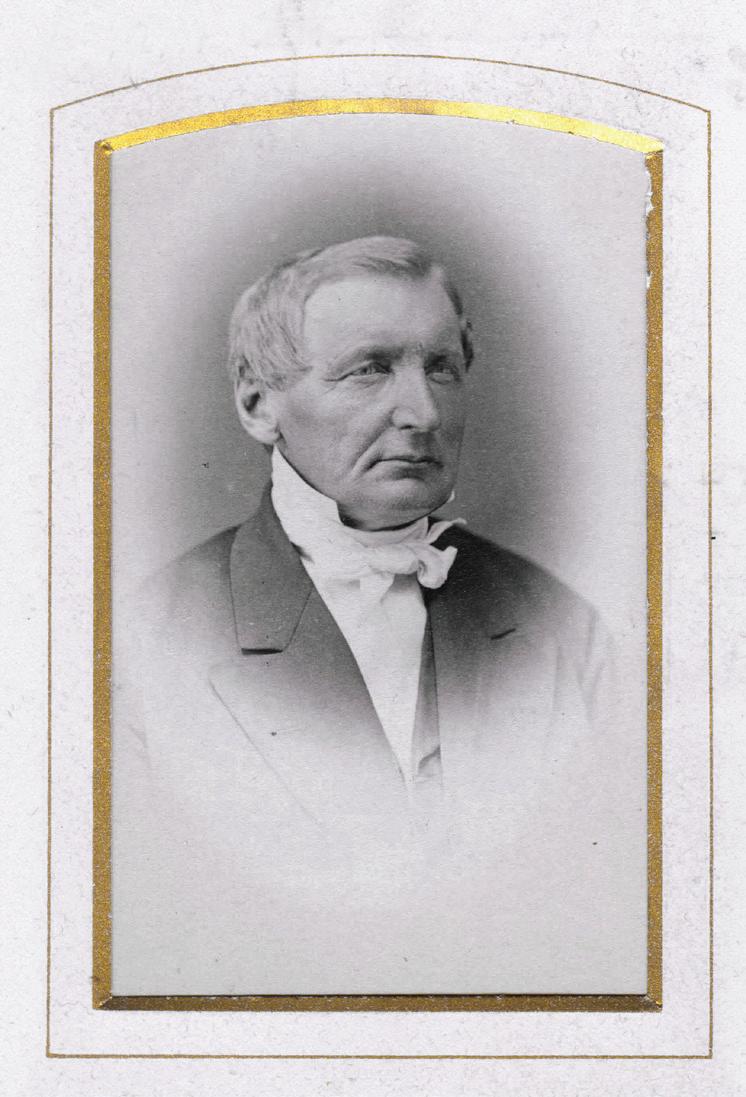

Shortly after the Civil War ended a Norwegian emigrant arrived, who was destined to play an important role in my life. He was a distant relative of mine by the name of Olaf Mandt.13 He was a boy of unusual gifts for acquisition of knowledge, and soon mastered English. Having been

Olaf Mandt. Courtesy of the NorwegianAmerican Historical Association.

employed by Rev. Otteson as a school boy, he went to live at the parsonage and soon ingratiated himself with the minister so much that he was treated as a son and adopted as such, and Otteson became responsible for his education. In August 1867 he joined the Confirmation class of the following year. I also attended this class though not enrolled as a member because I was not of the required age of 14. The following spring he was confirmed, and Otteson had already decided to send him to Luther College in the fall of 1868.

During the summer we were much together and often talked of literature, especially poetry. I had called his attention

to some of [Thomas] Campbell’s poems and he soon became quite enthusiastic, got a volume of Campbell’s poems and committed some of them to memory. He often spoke of the prospect of going to college and began urging me to go along. I listened eagerly, but without much hope as I saw an insurmountable obstacle in the fact that I was not confirmed. He thought that obstacle could be overcome and argued that I could get confirmed in Decorah just as well, and as I had been in his class, I would not need much time for preparation.

I gradually became obsessed with the idea of becoming a student, and started propaganda at home, but at first with no promise of success. Time began to fly, week after week passed, July was nearly gone, only a month left, on the first of September the college year would begin, and I was old enough, my brother Olaf was just the same age when he went to college.

My parents did not argue much, but saw the difficulties in the way: I had been very sick, and they were afraid I could not stand the strain.14 And then the expense! Finally, only a week before it was time to start. Mother began to give way; perhaps it would be best to let him try a year anyway; he is not very strong—not much good on the farm anyway. It soon appeared that father was quite willing to give his consent, so it was decided that I should go, and now there was a very busy week of preparation.

I had to have a new suit of clothes, linen and bed clothes, including an empty mattress etc. There was a cousin by the name of Martha staying in our house, a good needle woman, who helped making my suit. Coat and vest were made of black broadcloth that had been bought in Stoughton, but trousers were made from a heavy homespun woolen, made right in the room in which we were living.

Mandt and I had agreed on the day of departure, and we met in Stoughton. We both went to the photographer William

A. Fermann, and had our pictures taken, and we were both weighed. I weighed only 68 pounds and they all thought I was too light, and it has often occurred to me that there must have been an error, but the year was 1868, which made it easy to remember, and later on whenever there was a question about my weight, I called on the coincidence of the year and my weight to verify the fact. And at college it soon became evident that I was the smallest boy there and the lightest that had ever enrolled as a student at Luther College.

Luther College Faculty, December 1872. Standing, Freidrich A. Schmidt, Nils O. Brandt. Seated from left, Gabriel H. Landmark, Lyder Siewers, Knut E. Bergh, Laur. Larsen. Courtesy of the Norwegian-American Historical Association.

Endnotes

1 Koshkonong, Dane County, Wisconsin, was established by Norwegians in 1840 and became the third largest Norwegian settlement in the state by 1920. In fact, Dane County by 1890 boasted the fourth most Norwegian population of any county in the United States (6,728) behind Cook County, Illinois (22,365), Hennepin County, Minnesota (13,014), and Polk County, Minnesota (6,801). Olaf Morgan Norlie, History of the Norwegian People in America (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1925), 235.

2 Jens Christian Roseland, American Lutheran Biographies or Historical Notices of Over Three Hundred and Fifty Leading Men of the American Lutheran Church, From Its Establishment to the Year 1890 (Milwaukee: Press of A. Houtkamp & Son, 1890), 216. Accessed online via Google Books, August 17, 2010.

3 “Last Rites Held for Prof. Felland,” Northfield Independent, June 16, 1938; “Professor O.G. Felland, St. Olaf Teacher and Builder, Dies Friday,” Northfield News, June 17, 1938, 1, 5. “Professor O.G. Felland,” St. Olaf College Alumni Magazine, September 1938, 12.

4 The Norwegian Synod established an educational policy that in Theodore Blegen’s words, “revealed a critical attitude toward the American common school, whose spirit and discipline, it declared, were not conducive to the Christian development of the children.” Theodore C. Blegen, Norwegian Migration to America: The American Transition (Northfield, Minnesota: Norwegian-American Historical Association, 1940), 246.

5 Aggerholm boarded at Ole and Beinta Fimreite’s farm and for a time the Fimreite farmhouse served as the parochial school.

Felland considered Beinta “the worst scold I ever knew.” Aggerholm told Felland’s mother, “that the only thing he could eat with relish there was boiled eggs; he felt sure that they would be clean inside, even if the outside was not.” O.G. Felland, Autobiography (manuscript held in the St. Olaf College Archives, Northfield, Minn., 1927-1935), 15-16. Original notebooks later transcribed by unknown person, ca. 1967, 71 pages.

6 Concerning his parents’ education, Felland noted: “Father had a good education in the common branches taught in Norway at that time, that is, besides religion, the three R’s. Though he could write he did not practice it much. As far as I remember it was limited to signing his name. But he was fond of reading. He would buy nearly every book offered by the minister, these books being of a religious or edifying character, and of course all in Norwegian. Mother had never been taught to write and when her signature was required, as in the case of deeds, she made a cross. But she could read, and in later years when she had more leisure, she read diligently, especially religious literature.” Felland, 5, 8.

7 Translation provided by Dale Hovland, Bloomington, Minnesota, August 9, 2010:

When the cock full of gaiety/happiness crows

At dawn each morning

It’s as if it is saying to children

That morning has gold in its mouth

8 Knut Martin Olsen Teigen (1854-1914) was indeed a fascinating individual. Recommended reading: Orm Øverland, Chapter 13: “Knut Teigen and Peer Strømme: Natives of Wisconsin” in The Western Home: A Literary History of Norwegian America (Northfield, Minn.: Norwegian-American Historical Association, Distributed by University of Illinois Press, 1996), 170-186.

9 Felland writes of one tragic incident when school life and home life intersected: “Ole [Ole Oftelie] had a brother by the name of Bjorgulf, who was accidentally killed by upsetting a load [of lumber] which he was hauling. The parochial school was just in session at the home of his parents when his body was brought home. I saw the bruised corpse, and it made a deep impression on me. School was dismissed for the day, the only holiday of the parochial school that I can remember; it was probably in the year of 1858, before I was 5 years old.” Felland, 17-18.

10 Aggerholm stated at the school conference held at Rock Prairie (Oct. 1-2, 1858) that “as a matter of pedagogy, particularly in the matter of interesting the minds of young pupils, an unvaried diet of religion was inadvisable; and he therefore urged the inclusion not only of arithmetic and writing, but also of geography, natural history, and world history.” Blegen, 246.

11 Recommended reading: Frank C. Nelsen, “The School Controversy among Norwegian Immigrants,” in Norwegian-American Studies 26 (Northfield, Minnesota: NAHA, 1974), 206-219. Available online at www.stolaf.edu/naha/pubs/nas/volume26/index.htm

12 Victor Neuberg impressed Felland as a fine athlete and knew many “tricks.” Felland wrote, “I recall one day after school was dismissed, when we went outside to play. The farm wagon was standing in the yard with planks for hauling stone, instead of the wagon box. My brothers were turning handsprings on the ground. After watching them for a while Victor espied the wagon with its hind end toward him. He took a short running start, placed his hands on the planks, made a leap heels over head and landed near the front of the end firmly on his feet. I have never seen that trick repeated by any other man.” Felland, 12.

13 Rev. Olaf Mandt died of a bowel inflammation on Sept. 27, 1880, at the age of 28. Since 1877 he had served the Emigrant Mission for the Norwegian Evangelical Lutheran Synod of America in Baltimore. William S. Pelletreau, Historic Homes and Institutions and Genealogical and Family History of New York (New York, Lewis Publishing Company, 1907); Francis P. O’Neill, Index of Obituaries and Marriages in The Baltimore Sun, 1876-1880 (Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc., 2000). Accessed online via Google Books, August 17, 2010.

14 Referring to his sickness, Felland wrote, “In the early spring of one of these years (1866-68), I fell ill with pneumonia, very sick, they despaired of my life and I was told afterwards that I had been in delirium several days. Dr. Magelson was summoned and treated the case as was instrumental in saving my life. But mother too should be given at least equal credit, and their final success I ascribe to Him who had given me life in the first place. At the same time one of my school mates by the name of Erik Garen was also down with the same sickness, had delirium and recovered. My folks told me afterwards that when I was out of my mind I was always talking about school and school books and lessons and games, snapping my thumb as if I were playing marbles, while Erik would be raving about cows and horses and feeding the pigs, or other farm work. That, I understand he has been doing all his life. . . . I too, have followed the program of my delirium. Is delirium prophetic?” Felland, 12-13.

About the Author

Jeff Sauve is an associate archivist for St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota. In addition, he serves as an associate archivist for the Norwegian-American Historical Association (NAHA), which is located at St. Olaf College. He advises numerous local history organizations and offers his writing talents to help bring history to life, including the article “A Helping Hand: The Efforts of American Relief for Norway” in Vesterheim, Volume 5, Number 2, 2007. Sauve was recently recognized by the Minnesota Alliance of Local History Museums, who awarded him the Minnesota History Award for his editing of Pioneer Women: Voices of Northfield’s Frontier. The published booklet (2009), the first in a series put out by the Northfield Historical Society, highlights four first-hand stories of Northfield women who lived between 1856 and 1876. An award-winning columnist, Sauve writes a monthly column, “Looking Back,” for Sons of Norway Viking magazine.