Introduction

In the years leading up to the First World War, Nationalists and Unionists were opposed over the issue of Irish Home Rule. The Nationalists wanted their own Parliament in Dublin, while Unionists were opposed to this on religious and economic grounds.

By 1914 the Home Rule Crisis had deepened and sharply divided the country, leading to the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Irish Volunteers. Both groups had armed themselves with guns covertly brought in from Germany.

The outbreak of war in August 1914 temporarily defused the situation as both sides throughout Ireland provided recruits and generally supported the war effort.

Nationalists, who wanted Home Rule, had been committed to the war by John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP).

A minority of the Irish Volunteers, led by Eoin MacNeill, disagreed with Redmond and broke away. The larger Redmonite group became known as National Volunteers, and was supported by most Nationalists in south Armagh and south Down.

The anti-war minority retained the name, Irish Volunteers. The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret revolutionary group, exercised influence with the Volunteers and planned the Rising without MacNeill’s knowledge.

Despite two major setbacks, the interception of a ship carrying weapons from Germany and the subsequent cancellation order given by MacNeill, the Rising took place on Easter Sunday 23rd April 1916.

The Rising had some direct impact on the local area. A Newry man, Patrick Rankin, took part in the Rising and was involved in forming barricades in the General Post Office (GPO), and in street fighting. Newry IRB members, John Southwell and Robert Kelly, were arrested after the Rising and imprisoned.

The shooting of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a famous pacifist, writer and supporter of women’s suffrage, by Captain Bowen-Colhurst had local repercussions as Skeffington was originally from Downpatrick.

Poster advertising a Home Rule meeting in Newry, 1911 Armagh County Museum Collection Illuminated front cover of Newry’s Roll of Honour Newry had reputedly one of the highest enlistment rates of any town in Ireland and the Roll of Honour records 867 names. It remains unfinished as no further names were added after April1915. From 1916 onwards, recruitment began to fall away due to the heavy losses sustained on the western front. By 1918 supporters of Sinn Féin began to disrupt some of the recruiting rallies, most notably in Newry at the end of August 1918. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

These

Down County Museum Collection

Members of the South Down UVF marching through Kilkeel Courtesy of PRONI d2638/D/49/145 Postcard of Downpatrick under ‘Home Rule’

postcards were issued by Unionists to show what they thought towns in Ireland might be like under Home Rule.

Easter Week

During Easter Week 1916 a small group comprising Irish Volunteers and members of James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army, seized Dublin’s GPO and proclaimed an Irish Republic. British forces were brought into Dublin to put down the Rising, which lasted for almost a week.

Outside of Dublin, some Irish Volunteer units had also mobilised in places such as Cork, Galway and Coalisland, but because of Eoin MacNeill’s countermanding order, most of them returned home without fighting

In Dublin 64 of the rebels were killed, along with 132 British soldiers and around 230 civilians. Public opinion was initially unsympathetic to the rebels due to the loss of life and the destruction of public buildings in Dublin. In Newry, the Nationalist Frontier Sentinel newspaper described the events in Dublin as a “Wicked and Insane Movement”.

After the execution of the key leaders of the Rising, including Patrick Pearse and James Connolly and mass arrests of IRB members and Sinn Féin supporters, there was an upsurge of sympathy among many of the Nationalist population.

Postcard showing Sackville Street, Dublin, after the Rising Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Letter written by an unknown author who attended the month’s mind mass for Thomas MacDonagh, one of the leaders executed after the Rising Éamon Donnelly Collection, Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

“… There was Requiem Mass this morning in the University Church for the repose of the soul of Professor Mac Donagh … Mrs Mac Donagh was weeping all the time. She was dressed in black (excepting of course the Republican colours) the little boy was with Miss Grace Gifford and had a white suit on him – and the little girl had a little white frock. Poor little things.”

Postcard showing Sackville Street, Dublin, after the Rising Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Letter written by an unknown author who attended the month’s mind mass for Thomas MacDonagh, one of the leaders executed after the Rising Éamon Donnelly Collection, Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

“… There was Requiem Mass this morning in the University Church for the repose of the soul of Professor Mac Donagh … Mrs Mac Donagh was weeping all the time. She was dressed in black (excepting of course the Republican colours) the little boy was with Miss Grace Gifford and had a white suit on him – and the little girl had a little white frock. Poor little things.”

Design: G. Watters 07929131753

Postcard featuring the signatories of the Irish Proclamation which was issued during the Easter Rising, by the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army Courtesy of Cathy Brooks

Patrick Rankin – participant

The following witness statement given to the Bureau of Military History in 1948 refers to the Easter Rising of 1916:

‘‘… Peter McCann proposed that the three of us (Peter, my brother Owen and myself) should go to Dublin. … I thought it over, one brother in the family was sufficient, and Peter McCann was better living for Ireland ... I got John Southwell’s bicycle … as it was more free than my own, which was a Pierce of Wexford, and very heavy … It rained very heavily... until I arrived in Dublin about 7.30 p.m. (I carried a six inch revolver on my journey and, fortunately, I was not stopped by the police). … In a short time I was brought before Tom Clarke who knew me previously and he asked me had I any news of the North. I told him I had none. I think the old veteran knew as much as I did, but he never said a bad word about any man or county in the North. … He thanked me for getting through to the G.P.O. but he would have been delighted and happy to have had some hundreds of his own people from the Northern Counties present.”

Rankin’s descriptive account after his arrest highlights the diverse views of the Dublin public on the Rising. This includes an old woman saying “God bless you boys”, but others were not so sympathetic; with women following the prisoners shouting to the soldiers; “use your rifles on the German so and so’s”

Rankin was later imprisoned in Stafford prison in England, before being interned at Frongoch Camp in Wales. He was held until July 1916, and allowed to return to Newry.

Courtesy of the Irish Military Archives

Patrick Rankin (left) in the uniform of the Philadelphia National Guard In June 1914 Patrick Rankin went to live in Philadelphia, where he joined the National Guard. In his witness statement of 1948, Rankin said that he had joined the National Guards “… to train and prepare for the future.”

Courtesy of Joe Murray

Ruins of the General Post Office in Dublin after the Rising Down County Museum Collection

Born in Newry in 1889, Patrick Rankin was a painter by trade. In 1907 he became a member of the IRB. Courtesy of Joe Murray

Courtesy of the Irish Military Archives

Patrick Rankin (left) in the uniform of the Philadelphia National Guard In June 1914 Patrick Rankin went to live in Philadelphia, where he joined the National Guard. In his witness statement of 1948, Rankin said that he had joined the National Guards “… to train and prepare for the future.”

Courtesy of Joe Murray

Ruins of the General Post Office in Dublin after the Rising Down County Museum Collection

Born in Newry in 1889, Patrick Rankin was a painter by trade. In 1907 he became a member of the IRB. Courtesy of Joe Murray

Local involvement

Harry Willis

On his way home from Dublin on Easter Monday evening, Harry Willis had his car commandeered by a group of armed Volunteers from Castlebellingham. The following account is taken from the Frontier Sentinel, 6th May 1916:

“Mr. Harry Willis, son of Mr. Thomas P. Willis, Newry, was one of those who on Easter Monday evening had his motor car commandeered by the Sinn Féiners near Castlebellingham, when he was returning from Dublin. The other occupants of the vehicle – Dr. Cronin, Mr. W. C. M. Smith, V.S., and Mr. W. H. Connor – were ordered out, and till 5 a.m. on Tuesday morning he had a most exciting time conveying parties of insurgents to Tara Hill, Oldcastle, Drumcondra, and other parts. … Mr. Willis’s father is a member of the Carsonite “Provisional Government,” and additional humour is lent to the performance through the same motor having participated in the memorable gun-running scenes at Larne a few years ago.”

John Bannon

From Newry, Jack Bannon was in Dublin during Easter 1916. Like a number of army reservists, he had been called up with the outbreak of war. The following information comes from his diary which details his wartime experiences:

“Then came the Dublin Rebellion – Easter Week 1916 – when we were ordered for Dublin. A troop train left Belfast with a few hundred troops aboard, … From the moment we arrived in Dublin we were sniped from every quarter house, top gates and windows, and from houses overlooking the station, and any of our boys who tried to leave the Station generally got knocked out by these snipers. After two days we left the railway station and got into the city, but in doing so we lost quite a few men. The British Forces were in several parts of the city at this time, but were not in touch with one another, with the result one party at a time was firing at each other and caused a number of casualties. We had little to do with this affair and all were delighted when it was over.”

Thomas P. Willis, father of Harry Willis, was a staunch Unionist, who had been Chairman of Newry Urban District Council Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

John Bannon in the uniform of the Royal Irish Rifles After the Rising John Bannon applied to be a Drill Instructor in “any part of Africa”, and served in the King’s African Rifles in East Africa until April 1919.

Courtesy of Patrick Bannon

Thomas P. Willis, father of Harry Willis, was a staunch Unionist, who had been Chairman of Newry Urban District Council Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

John Bannon in the uniform of the Royal Irish Rifles After the Rising John Bannon applied to be a Drill Instructor in “any part of Africa”, and served in the King’s African Rifles in East Africa until April 1919.

Courtesy of Patrick Bannon

Easter Sunday

Sinn Féin

Éamon

Éamon Donnelly and his eldest child, Eleanor (Nellie), c.1923 On

1916 Donnelly joined with Volunteers from the north who mobilised at Coalisland, Co. Tyrone. He later acted as director of elections in 1918 for the

party in north east Ulster and was a founder member of Fianna Fáil.

Donnelly Collection, Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Courtesy of Patrick Bannon

Political Aftermath

As Nationalist attitudes hardened with the execution of the leaders of the Rising, many former supporters of the IPP turned to Sinn Féin.

The death of the south Armagh IPP MP, Dr. Charles O’Neill, provided the opportunity for the first electoral clash in Ulster between Sinn Féin and the IPP.

Violence characterised some of the campaigning, Countess Constance Markievicz was pelted with eggs in Newry and Éamon de Valera was reputedly injured near Crossmaglen, while supporting the Sinn Féin candidate Dr. Patrick MacCartan. The IPP candidate, Patrick Donnelly, was a Newry solicitor and his campaign included visits by leading members of the IPP including Joseph Devlin and John Dillon.

The election was won by the IPP, but the campaign had helped boost the profile of Sinn Féin in the area.

In the general election held in December 1918, as part of an electoral pact, the Sinn Féin candidate in the South Down constituency, Éamon de Valera, withdrew his candidature to ensure a victory for the IPP candidate, Jeremiah McVeagh.

Across Ireland as a whole, though, the election was a disaster for the IPP. Sinn Féin gained 73 out of the 105 seats, while the Unionists took 26 seats and the IPP only six.

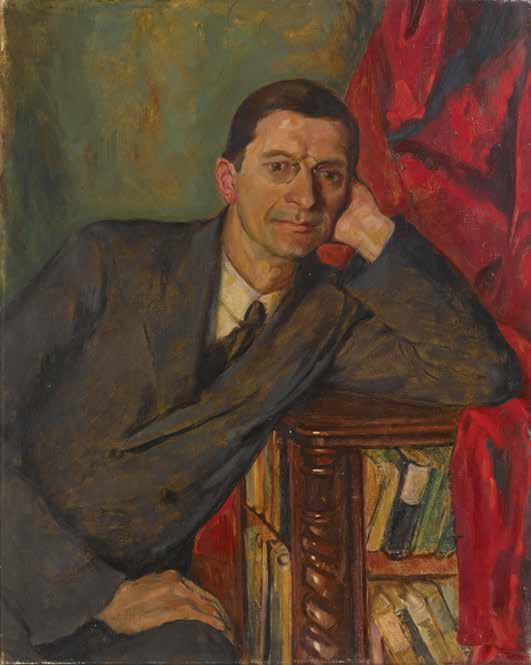

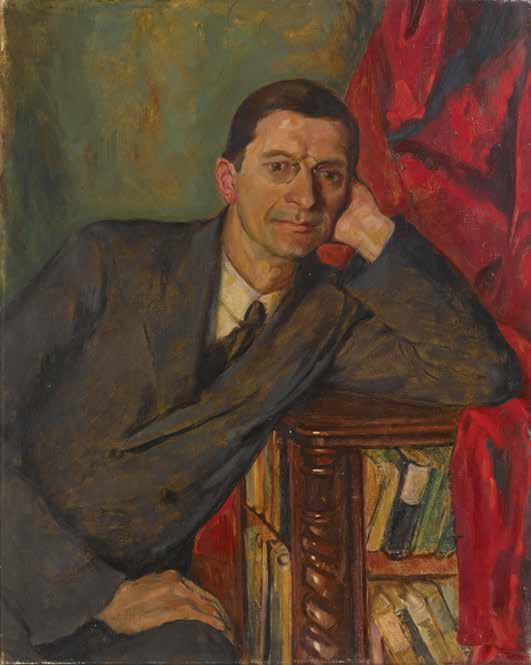

South Armagh by-election poster produced by Sinn Féin, 1918 From a by-election contest precipitated by the death of the sitting MP. In response to a fall in recruitment across the British Isles from 1915 onwards, various levels of conscription were introduced in a series of Military Service Acts. The threat of conscription being extended to Ireland became a contentious issue in Irish politics after 1916. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection Local Nationalists Standing, Frank Aiken (2 from left), John McCoy (4 from left),and seated Padraig Quinn (left) and Ned Fitzpatrick (right). In April 1917, Aiken hoisted a number of Sinn Féin flags around Camlough and in April 1918 he was arrested and imprisoned for ‘illegal drilling’. Reproduced by kind permission of UCD Achives Painting of Éamon de Valera by Margaret Clarke, 1928 Éamon de Valera, the only leader of the Easter Rising not to be executed, was a member of Sinn Féin until 1926. He founded a new party, Fianna Fáil, and was subsequently elected Taoiseach or Prime Minister three times and then President of the Irish Republic. Margaret Clarke (nee Crilly) was a Newry-born artist who became one of Ireland’s foremost portrait painters in the inter-war years. Reproduced courtesy of The Irish News and Fiana Griffin. Photography by Bryan Rutledge.

Postcard showing Sackville Street, Dublin, after the Rising Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Letter written by an unknown author who attended the month’s mind mass for Thomas MacDonagh, one of the leaders executed after the Rising Éamon Donnelly Collection, Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

“… There was Requiem Mass this morning in the University Church for the repose of the soul of Professor Mac Donagh … Mrs Mac Donagh was weeping all the time. She was dressed in black (excepting of course the Republican colours) the little boy was with Miss Grace Gifford and had a white suit on him – and the little girl had a little white frock. Poor little things.”

Postcard showing Sackville Street, Dublin, after the Rising Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Letter written by an unknown author who attended the month’s mind mass for Thomas MacDonagh, one of the leaders executed after the Rising Éamon Donnelly Collection, Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

“… There was Requiem Mass this morning in the University Church for the repose of the soul of Professor Mac Donagh … Mrs Mac Donagh was weeping all the time. She was dressed in black (excepting of course the Republican colours) the little boy was with Miss Grace Gifford and had a white suit on him – and the little girl had a little white frock. Poor little things.”

Courtesy of the Irish Military Archives

Patrick Rankin (left) in the uniform of the Philadelphia National Guard In June 1914 Patrick Rankin went to live in Philadelphia, where he joined the National Guard. In his witness statement of 1948, Rankin said that he had joined the National Guards “… to train and prepare for the future.”

Courtesy of Joe Murray

Ruins of the General Post Office in Dublin after the Rising Down County Museum Collection

Born in Newry in 1889, Patrick Rankin was a painter by trade. In 1907 he became a member of the IRB. Courtesy of Joe Murray

Courtesy of the Irish Military Archives

Patrick Rankin (left) in the uniform of the Philadelphia National Guard In June 1914 Patrick Rankin went to live in Philadelphia, where he joined the National Guard. In his witness statement of 1948, Rankin said that he had joined the National Guards “… to train and prepare for the future.”

Courtesy of Joe Murray

Ruins of the General Post Office in Dublin after the Rising Down County Museum Collection

Born in Newry in 1889, Patrick Rankin was a painter by trade. In 1907 he became a member of the IRB. Courtesy of Joe Murray

Thomas P. Willis, father of Harry Willis, was a staunch Unionist, who had been Chairman of Newry Urban District Council Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

John Bannon in the uniform of the Royal Irish Rifles After the Rising John Bannon applied to be a Drill Instructor in “any part of Africa”, and served in the King’s African Rifles in East Africa until April 1919.

Courtesy of Patrick Bannon

Thomas P. Willis, father of Harry Willis, was a staunch Unionist, who had been Chairman of Newry Urban District Council Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

John Bannon in the uniform of the Royal Irish Rifles After the Rising John Bannon applied to be a Drill Instructor in “any part of Africa”, and served in the King’s African Rifles in East Africa until April 1919.

Courtesy of Patrick Bannon