War Declared: the local impact of World War II

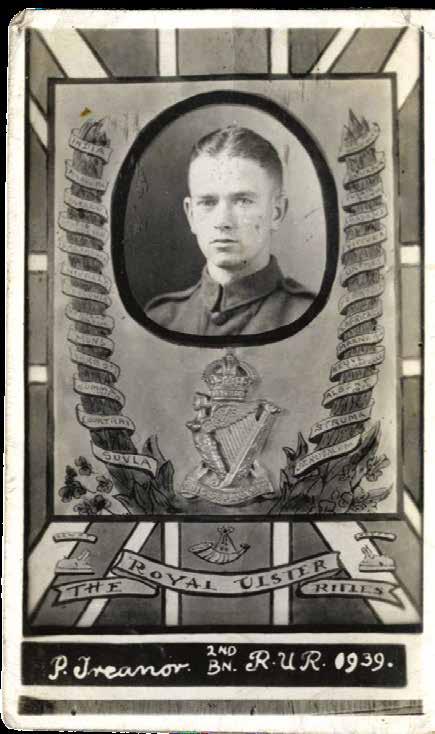

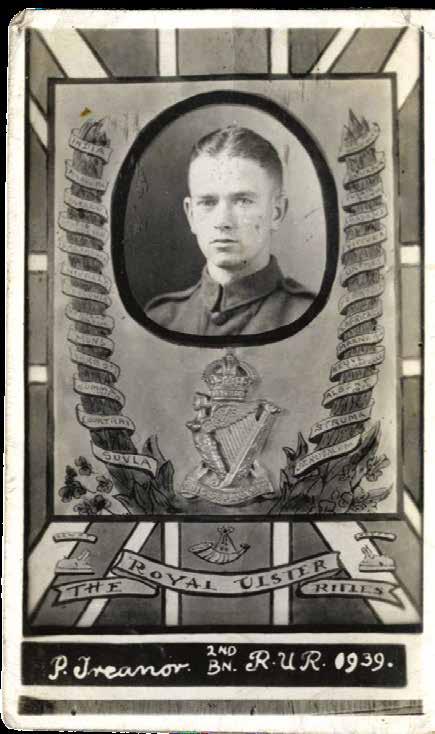

Memorial Card for Rifleman Patrick Joseph Treanor, Linenhall Square, Newry, of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles, who was killed on active service in Belgium on 28th May 1940, aged 20.

Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Memorial Card for Rifleman Patrick Joseph Treanor, Linenhall Square, Newry, of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles, who was killed on active service in Belgium on 28th May 1940, aged 20.

Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Réamhrá an Chathaoirligh

Tá lúcháair orm réamhrá a scríobh don leabhrán taispeántais seo a théann leis an taispeántas sealadach dar teideal “Cogadh Fógartha: an tionchar a bhí ag an Dara Cogadh Domhanda go háitiúil” atá in Iarsmalann an Iúir agus Mhúrn.

D’fhógair An Ríocht Aontaithe cogadh ar an Ghearmáin ar 3 Meán Fómhar 1939, agus tá an taispeántas suntasach seo ag comóradh ochtó bliain ó bhris an Dara Cogadh Domhanda amach, trí shúil a chaitheamh ar thionchar na coimhlinte ar an Iúr agus Múrna. I measc phríomhthéamaí an taispeántais cuirtear béim ar na hullmhúcháin a rinneadh sa cheantar don chogadh go mall sna 1930í, Cosaint Shibhialta, earcaíocht áitiúil sna fórsaí armtha, aslonnaithe, ciondáil agus smuigleáil, reisimintí a bhí lonnaithe sa cheantar, agus teacht trúpaí agus eitleoirí na Stát Aontaithe sa bhliain 1942. Chomh maith leis sin, sa taispeántas seo pléitear impleachtaí an Chogaidh ar an gheilleagar áitiúil, go háirithe i gcomhthéacs phobal an teorann, agus oidhreacht an Chogaidh ar an cheantar go mall sna 1940í agus 1950í. Pléitear na téamaí seo fosta trí chuimhní cinn ó dhaoine áitiúla a léiríonn tionchar an Dara Cogadh Domhanda ar dhaoine aonaracha, theaghlaigh agus phobail. Is minic nach ndéantar taifead ar scéalta den chinéal seo in áiteacha eile.

Ba mhaith liom mo bhuíochas a ghabháil le daoine a d’fhreagair na hachainí a rinne an Iarsmalann ar lorg chuimhní, iarsmaí, ghrianghraif agus doiciméid; is achmhainn fhíorluachmhar é an t-ábhar a thug siad chun na glúnta atá le teacht a chur ar an eolas faoin tréimhse seo i stair an cheantair.

An Comhairleoir Marcas Ó Murnáin Cathaoirleach Chomhairle Cheantair an Iúir, Mhúrn agus an Dúin

Chairperson’s Foreword

I am delighted to write the foreword to this exhibition booklet, which accompanies War Declared: the local impact of World War II, a temporary exhibition at Newry and Mourne Museum.

The United Kingdom declared War on Germany on 3 September 1939 and this major exhibition marks the eightieth anniversary of the outbreak of World War II by looking at the impact of the conflict on Newry and Mourne. Key themes in the exhibition include preparations for war in the area during the late 1930s, Civil Defence, local recruitment in the armed forces, evacuees, rationing and smuggling, regiments stationed in the area and the arrival of American troops and airmen in 1942. The exhibition also considers the effect of the war on the local economy, especially in the context of a Border community, and the legacy of war in the area in the later 1940s and 1950s.

These themes are also explored through the memories of local people which highlight the impact of World War II on individuals, families and communities. Many such stories are often undocumented elsewhere.

I would like to thank all those who responded to the Museum’s appeal for memories, artefacts, photographs and documents; their contribution is invaluable for interpreting this period of local history for future generations.

Mark Murnin Chairman of Newry, Mourne and Down District Council

Councillor

Life on the Home Front

Situated on the western fringe of Europe, Ireland did not escape the ravages of World War II. By this time Ireland was partitioned into two separate jurisdictions, Northern Ireland and Éire. Around 38,000 men and women in Northern Ireland volunteered for the war effort. The Irish Free State, renamed Éire in the 1937 constitution, pursued a policy of official neutrality, though over 150,000 Éire citizens were employed in the war effort as they sought work in British factories, while 40,000 joined the British forces.

On the day war was declared, the passenger liner SS Athenia, en route from Belfast to Quebec, was torpedoed in the North Atlantic. Many of the 1400 passengers on board lost their lives, including some from the Newry area.

Fearing German invasion through the south, British troops were stationed almost immediately around Newry, joined later by American forces in their preparations for battle and in the last months of the war, troops from the Regular Belgian Army were also stationed locally.

The war had many direct consequences on daily life for local people. The German invasion of much of mainland Europe and submarine activity in the Atlantic and around the British coast resulted in shortages of foodstuff, clothing and petrol. There was also an impact on the economy and restrictions on travel were introduced. This affected people on both sides of the Irish border.

Members of the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) pictured outside Newry Town Hall. Branches of the WVS were organised locally. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Members of the Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) pictured outside Newry Town Hall. Branches of the WVS were organised locally. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

One of the most visible aspects of the war in Newry were the defensive features that were built including pillar boxes and metal and concrete blockades on the main roads leading in to Newry.

Air Raid Precaution measures were also implemented. These included the regulation of lighting, known as the Blackout Order, to restrict lighting at night to prevent aerial attacks. Black fabric was used to cover windows of buildings while car and bicycle lights were screened. Newry was one of the first towns in Northern Ireland to have special blackout ‘starlight’ street lighting.

Air Raid sirens and shelters were situated in Newry, Bessbrook, Kilkeel and Warrenpoint. Some local people became Air Raid Precaution (ARP) Wardens who were to ensure that the blackout was maintained and to advise and direct the population in the event of an aerial attack. Gas attacks were widely feared, and gas masks were supplied from distribution points such as Newry Town Hall, Kilkeel Courthouse and several local primary schools. The Women’s Voluntary Service (WVS) was established as a support unit for the ARP. In Newry and Warrenpoint

they assisted with the distribution of evacuees and organised recycling campaigns. Many local men joined the Local Defence Volunteers, more commonly known as the Home Guard who were responsible for Home Front security.

Air Raid Precaution measures also facilitated the evacuation of children from large urban areas. At least 1,446 children were expected in Newry in the first ‘wave’ of refugees on 8 September 1939. Few arrived, and it was not until the following July that more significant numbers began to arrive. The numbers of evacuees increased dramatically in the aftermath of the Belfast Blitz in April and May 1941 with many children and their families finding shelter in the Newry area.

In response to shortages, rationing had been introduced in Britain in November 1939, and in January 1940 to Northern Ireland. The system aimed to ensure that everyone got a fair share of scarce resources. Following registration everyone was issued with a ration book. Set amounts of foods were allocated to each person on a weekly basis with coupons which were exchanged for goods in shops.

Tommy White a farmer from Ballynaskeagh, outside Newry, pictured in 1941 with Billy Bleakley, an evacuee. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

The government encouraged everyone to make use of any land they had to produce vegetables and foodstuffs. Under the government’s compulsory tillage policy, farmers were set quotas of crops to grow and cultivate, particularly oats, barley and wheat which had previously been imported. They were given subsidies to help them achieve this, especially if it required increased mechanisation such as the use of tractors. Flax production increased dramatically during World War II to make up for the shortage of other fibres and was used for making ropes, fabric, parachutes and for linseed oil.

As most of the clothing factories had to concentrate on making uniforms for the forces, there was a limit on the amount of clothing produced for sale in the shops. People had to ‘make do and mend’. Men were encouraged to wear austerity suits which had fewer pockets and no turn ups, while women’s skirts and dresses were also made shorter.

Materials were in short supply during the war and there was extensive recycling of goods. Paper was recycled to make books and newspapers. Newry and Warrenpoint had a ‘Wings for Victory’ campaign, where people were encouraged to give their scrap metal to reach a certain target, to ‘Build a Spitfire Scheme’.

Newry Home Guard, pictured at Sandys Street Presbyterian Church. Members in the photograph include Jackie Reid, Billy Heather, Eric Linton, Ernie Ferris, Jack Ferris and Benny Davis. Courtesy of William McAlpine

Newry Home Guard, pictured at Sandys Street Presbyterian Church. Members in the photograph include Jackie Reid, Billy Heather, Eric Linton, Ernie Ferris, Jack Ferris and Benny Davis. Courtesy of William McAlpine

The war brought positive economic benefits as large numbers of people were employed in the construction of defense structures and the production of materials for the armed forces.

For example, Bessbrook Spinning Mill produced over 22,000 yards of cloth for use in the manufacture of tents and uniforms. Smith & Pearson, an engineering firm based at Merchant’s Quay in Newry, produced steel tanks which were used in the construction of Mulberry harbours. At the request of the Admiralty the firm moved to Warrenpoint and began to produce landing craft. Construction began in 1943, and when the Allied forces began retaking control of Europe in the Normandy D-Day landings of June 1944, many of these landing crafts were used.

As an agriculturally-based society, Northern Ireland was not as badly off for food as Britain. Cross border smuggling was also rife, as shops in the villages on the southern side of the Border were relatively well stocked, particularly in the early years of the war. Goods, which were in short supply on one side of the border, could be exchanged for items that were more plentiful on the other side. To supplement their rations local people would have gone to Omeath by car, bicycle, train or the Red Star Ferry Service and brought back cheese, bacon, jam, chocolate, cigarettes and lighters.

Social functions were organized to boost morale or to raise funds for the war effort. While on leave, British and American soldiers in the Newry area would often have crossed the border. They would have worn civilian clothes and socialised and gone to dances in places like Blackrock. Irish comedians such as Jimmy O’Dea and Jack Cruise entertained British and American troops in the Town Hall, Newry. While in Kilkeel, the Vogue cinema was a popular venue not only for film screenings, but also for cabaret acts, dancers and musicians to entertain the troops.

Thomas McCrum, Sam Burns, Tommy White and Jack White pictured working at the flax dam, Ballynaskeagh in 1941. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Wartime queue outside ‘The Pork Shop’, Dundalk. Meat was one of the many items rationed on both sides of the border. Courtesy of the County Museum, Dundalk

Thomas McCrum, Sam Burns, Tommy White and Jack White pictured working at the flax dam, Ballynaskeagh in 1941. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Wartime queue outside ‘The Pork Shop’, Dundalk. Meat was one of the many items rationed on both sides of the border. Courtesy of the County Museum, Dundalk

Troops in the Area

The first fifteen months of the war saw the arrival of increasing numbers of British troops in Northern Ireland. This was initially to maintain internal security, but by May 1940, their function had changed to guarding against German invasion through the south of Ireland. The first British troops to arrive were units of the 53rd Welch Division, some of which were stationed in Newry and Bessbrook and trained on Slieve Gullion. Other British regiments to come to the area included the Cheshire Regiment and the Northumberland Fusiliers.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour 7 December 1941, the United States of America formally entered the war. The first American

troops arrived in Belfast in January 1942 with the purpose of building new airfields to prepare for the arrival of further troops. Land at Greencastle near Kilkeel, Co. Down, had already been requisitioned on 9 December 1941 by the British Air Ministry, as a site for one of the airfields. Around 800 people were employed in the construction of the new aerodrome which opened on 30 July 1942. Over the next year the aerodrome proved invaluable as a stopover facility for aircraft, and became home to United States Air Force units engaged in maintenance, training and flying operations. General Patton visited in March 1944 when he inspected his 5th Infantry Division in the Mournes. Local tradition has it that female nurses were asked to leave the platform, so they would not hear his colourful language. American officers socialised with local people throughout the area and some girls became GI brides.

The Earl and Countess of Kilmorey with their grandson, Nicholas Anley and two American officers at Mourne Park, Kilkeel. Courtesy of the Anley Family

Performers in the Vogue Cinema, Newry Street, Kilkeel in the 1940s. The Vogue Cinema in Kilkeel was officially opened by the Countess of Kilmorey on 19 April 1940. As well as screening films, it was also used as a venue for entertaining troops stationed in the district. Courtesy of Rae McGonigle

There were also American troops stationed around the district at Bessbrook, Drumbanagher, Dromantine and at Ashgrove, Newry.

Several large houses and estates in the area were requisitioned to accommodate the British and American troops. Camps, comprising Nissan huts, were set up in the grounds of the estate for the troops while the officers resided in the

main house. The owners were usually allowed to remain in residence but their movements around their own property were sometimes severely restricted. Examples of requisitioned houses and estates include Mourne Park, near Kilkeel (the seat of the Earls of Kilmorey), Narrow Water Castle, Warrenpoint, home of the Hall family and Mount Caulfield, near Bessbrook, owned by the Richardsons of Bessbrook Spinning Mill.

GI brides and friends at a farewell dinner held in the Royal Hotel, Kilkeel in the 1940s. Courtesy of Catherine Hudson

Nissan huts at Ballyedmond, near Rostrevor, which was the camp for the 10th Infantry Regiment of the American army. Courtesy of Catherine Hudson

Those who Served

Many people from the Newry and Mourne area joined the armed forces during World War II. There was an army recruitment office at 97 Canal Street in Newry and local newspapers encouraged people to enlist in one of the armed services. Very few families in the area were unaffected by the war and often more than one family member enlisted.

One of those from Newry who died on active service was Michael Flood Blaney, the son of Charles Blaney, the Town Surveyor in Newry. Blaney joined the Royal Engineers Bomb Disposal Unit on 5 December 1940 and was killed a few days later when defusing a bomb at Manor Park in Essex. He was posthumously awarded the George Cross in 1941. Another who died was Cyril

Wiltshire. Originally from Wales and a member of the Welch Regiment, Cyril Wiltshire married a local girl and lived in Castle Street in Newry. He was killed on 21 July 1944 when his battalion came under heavy attack from German forces in Normandy.

Many others lost their lives at sea. Royal Navy Petty Officer John Felix O’Connell from Camlough, was among the 1,415 men who died when HMS Hood was sunk in the Battle of the Denmark Strait on 24 May 1941. This was the greatest single shipping loss of the War. Merchant ships were also a prime target for attack and, in October 1941, Bernard Golding from Erskine Street in Newry was lost when SS Walnut, owned by Joseph Fisher and Sons in Newry, went missing in the Irish Sea.

Local merchant seamen, Bernard Murphy (left) from Cloghogue and Terry O’Hanlon (right) from Lower Fathom, Newry, who served on the Dorrien Rose, pictured outside Buckingham Palace on 23 September 1941, after being decorated for their bravery. Courtesy of Eileen Murphy

Local merchant seamen, Bernard Murphy (left) from Cloghogue and Terry O’Hanlon (right) from Lower Fathom, Newry, who served on the Dorrien Rose, pictured outside Buckingham Palace on 23 September 1941, after being decorated for their bravery. Courtesy of Eileen Murphy

Nurse Margaret Anderson, from Ballinran, Kilkeel, was a veteran of World War I, and served in the nursing reserve in World War II and took part in the evacuation of Dunkirk. An obituary, following her death in 1956, described her as Mourne’s Florence Nightingale.

Courtesy of Elana Patterson, and the family of Margaret Anderson

Nurse Margaret Anderson, from Ballinran, Kilkeel, was a veteran of World War I, and served in the nursing reserve in World War II and took part in the evacuation of Dunkirk. An obituary, following her death in 1956, described her as Mourne’s Florence Nightingale.

Courtesy of Elana Patterson, and the family of Margaret Anderson

A local member of the Royal Air Force who was killed in action was Charles Murray whose family lived in Poyntzpass. Murray had joined the RAF in 1936 and had seen service in Palestine. He was killed when his plane was shot down over Poland on 30 August 1944.

A number of local men played a part in some famous episodes of the war. Robert Caldwell, who lived in Cowan Street, Newry, was a crewmember of HMS Exeter, which was in the Battle of the River Plate, off the coast of Uruguay in December 1939 when the German battleship, Graf Spee, was destroyed. Caldwell was welcomed as a ‘local hero’ when he returned home on leave in March 1940 and was awarded a gold watch by the Young Men’s Institute in Newry.

The evacuation of Allied Troops from Dunkirk in June 1940 also saw involvement by local service men. Bernard Murphy, Chief Engineer, and Terry O’Hanlon, First Mate, were among the crew of the Dorrien Rose, a tramp steamer, which made three trips across the English Channel, rescuing 1,600 men, before the ship’s boilers gave up.

Major Gerald Reside, a Newry architect and engineer and a member of the British Expeditionary Force, was one of the last soldiers to be evacuated from Dunkirk.

Another who saw active service was Lt. John Gough who served with the 3rd Battalion Irish Guards in Normandy and Belgium in 1944-5. He was involved in the capture of ‘Joe’s Bridge’ on the Bocholt-Herentals Canal in Belgium and led a night attack at the village of Gildehaus when the Battalion crossed the Rhine into Germany in April 1945.

Nora Patricia Mahood, from Newcastle, trained as a nurse at the Royal Victoria Hospital. She joined Queen Alexandra Royal Army Nursing Corps, and from 1945 to 1948 looked after former prisoners of war in India. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Nora Patricia Mahood, from Newcastle, trained as a nurse at the Royal Victoria Hospital. She joined Queen Alexandra Royal Army Nursing Corps, and from 1945 to 1948 looked after former prisoners of war in India. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Women were not exempt from military service and many of them joined the Women’s Royal Navy (WRNS) such as Lady Hyacinth Needham and the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) including Peggy Hall. Others joined the WVS, who assisted the ARP, as well as raising funds for the war effort and helping with evacuees. Many other women served as nurses such as Margaret Anderson and Nora Mahood.

James Quinn and comrades in Germany, James is pictured third from left, holding a camera. James Quinn, originally from Kilkeel, emigrated to America in 1936, and from 1943 – 1945 served in the American army with the 563rd Motor Ambulance Company. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

James Quinn and comrades in Germany, James is pictured third from left, holding a camera. James Quinn, originally from Kilkeel, emigrated to America in 1936, and from 1943 – 1945 served in the American army with the 563rd Motor Ambulance Company. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

The End of the War

Hitler died on 3 May 1945 and by 8 May, Germany’s surrender was being reported and was designated Victory in Europe (VE) Day. A Victory Parade was arranged for Newry on the following evening and there were to be bands and sports at the Intermediate School. At 10 o’ clock all the Protestant Churches held Thanksgiving Services. On the following day, 10 Wednesday, a United Service took place in Newry Town Hall, which was also the venue for a CEMA (Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts) Concert and relaying of the Prime Minister’s speech at 9 o’ clock. Bunting was displayed for street parties and crowds gathered at Trevor Hill to hear the Victory Announcement and the King’s speech. Hitler effigies were burned on the bonfire lit at the Intermediate School and parades and bonfires for Victory Celebrations took place in Markethill, Poyntzpass, Warrenpoint, Rathfriland and Kilkeel.

Following the Japanese surrender, Victory in Japan (VJ) Day on 15 August, confirmed the war had truly ended. As prisoners of war and men and women demobbed from the forces returned, further ‘Welcome Home’ events took place. For many families who had lost loved ones, life would never be the same again.

The years following the war saw many changes. From 1947, the Education Act provided free and compulsory education up to the age of 15, while the National Health Service, extended to Northern Ireland in 1948 made medical treatment free and available to all. In Newry, a scheme of house building created housing in Rooney’s Meadow, James Connolly Park and in the Daisy Hill, Monaghan Row area. In 1952 electric street

lighting was introduced and Newry became the first town in Ireland to be completely lit by electricity. Gradually, wartime restrictions were lifted, although shortages of goods remained, and rationing continued through to the mid-1950s.

Erecting an electric light, Monaghan Street, Newry. Newry Urban District Council appointed P.J. Murray, Electrical Contractors, to install electric street lights in Newry in 1952. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Erecting an electric light, Monaghan Street, Newry. Newry Urban District Council appointed P.J. Murray, Electrical Contractors, to install electric street lights in Newry in 1952. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

© William McAlpine

© William McAlpine

Lost in History: the sinking of the SS Athenia 3 September 1939

Mary McGrath

On 3 September 1939 at 11.15 am, Great Britain declared war on Germany. Within hours a German U-Boat, one of 14 secretly deployed around the coast of the British Isles, torpedoed the unprotected passenger liner the Athenia killing 98 passengers and 19 crew of 1,100 passengers and 345 crew.

On the 1 September the Athenia, bound for Montreal in Canada, set sail from Glasgow, stopping off at Belfast and Liverpool to pick up passengers. Most of the passengers were women and children and included Jewish refugees trying to escape the impending war.

Athenia owners had taken the precaution of blackening its portholes and dimming the navigation lights as the ship journeyed through the Irish Sea towards the Atlantic Ocean. Having received news of the declaration of war the captain posted a notice to all passengers at noon on the same day and took the added precaution of removing the lifeboat covers.

Within hours of the British declaration the German U-Boats were put into active service, but were bound to operate under the Prize Rules which forbade attacks against passenger liners

At 4.30pm a German U-boat, under the command of a Lieutenant Lemp, spotted the Athenia travelling outside normal shipping lanes, at speed in a zig-zagging formation. At 7.30pm, having wrongly deduced that the liner was an armed merchant ship and observing none of the international protocols, Lemp ordered two torpedoes to be fired, one of which struck the Athenia. A subsequent SSS (Sunk by Submarine) distress call was intercepted by Lemp’s crew which allowed them to identify the vessel as a passenger liner by reference to the Lloyds’ Register of ships.

At the time Hitler was still optimistic of a diplomatic solution with Britain and Lemp, understanding the consequences of his actions against innocent and defenceless civilians, ordered the U-boat to leave the scene without offering assistance to victims and decided not to report the incident to his superior officers. He asked his crew to remain silent too. The German authorities first heard the news of the sinking of Athenia from BBC World Service. They were anxious to avoid a reoccurrence of the events of the World War I when the sinking of the Lusitania had resulted in bringing America into the war. It was late September before the German Naval authorities became fully aware of the details of the attack on the Athenia but kept quiet and covered up these details for political reasons.

Reported and condemned worldwide, as a monstrous war crime, Lemp’s attack was a propaganda gift to the British. Hitler’s first step was to deny any responsibility for the attack and Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Goebbels, issued a statement claiming that it was a British torpedo that sunk the Athenia in an attack planned by Churchill in an attempt to bring America into the war. The truth about the sinking of Athenia only emerged after the war at the Nuremberg Trials in January 1946. Several ships responded to Athenia distress call - HMS Electra, the Swedish yacht Southern Crossing, the Norwegian freighter Knute Nelson and the American freighter, The City of Flint. Tragically more passengers and crew died in the rescue attempt. The Norwegian freighter Knute Nelson had rescued 449 survivors but had accidentally crushed one of the lifeboats with its propeller, with only 8 of the 53 on board surviving. Yet another 10 survivors died when their lifeboat capsized under the stern of the Southern Cross and another 3 survivors were crushed to death while attempting to transfer unto the Royal Navy destroyers.

Athenia survivors were taken to Glasgow and Galway. Many heart-breaking and courageous stories emerged including accounts from people with relatives in the Newry area. One of the victims was a Mrs Burrows, the sister of the manager of the Belfast Bank in Newry, a Mr Coleman. She had been travelling with her son and daughter to Montreal and was killed during the rescue attempt by Knute Nelson. Buried at sea, her children were rescued and returned to Glasgow. Early reports exposed the confusion experienced by authorities. For example, reported missing persons, Miss Anne Doyle (Hilltown), Miss Mary Carroll (Rathfriland) and Michael McShane a native of Newry, were eventually located on other ships. Mr and Mrs Cass-Beggs, whose relatives were from Rostrevor, received

the joyful news that their missing child had been found on the vessel City of Flint. Other survivors from nearby districts were Mary Hunt (Tandragee), John Shiels (Carlingford) and Patrick Cunningham (Dundalk). Mrs Phil Smyth and her two daughters, the sister of Mr V. Kelly, a well-known Newry draper and outfitter in Hill Street, had the lucky misfortune to miss their return journey to Canada on the Athenia. She had been late at reclaiming her passage and as a result her berths had been allocated to others.

The loss of the Athenia on the first day of the war generated much controversary, confusion and political sensitivity. It was instrumental in hardening global opinion against Germany, particularly in America.

Athenia Timeline: Sunday 3 September 1939 03/09/1939

04/09/1939

Sinks (Monday 4 September)

Picture of the passenger liner SS Athenia, torpedoed in the North Atlantic on the day war was declared, 3 September 1939. © TopFoto

Britain Declares war on Germany Athenia Captain notifies passengers of war German submarines put on active service German U-boat spots Athenia Athenia torpedoed

Athenia

Wartime Newry

William McAlpine

Based on memories recounted by William McAlpine to Noreen Cunningham in March 2019.

I was born in Chapel Street in Newry in 1933 and a few years later my father and mother became live-in caretakers of Thompson Memorial Hall, on the Downshire Road, and we moved there.

Newry before the war was laidback, but during the war, life changed completely. I remember standing at the gate of the house and everybody was talking about the war. I was six years old and I wondered how does war start, does everybody come out fighting with sticks?

I attended Windsor Hill School, which at that time was in Church Avenue. At school we usually never carried our gasmasks, but it was compulsory to bring your gasmask for an air raid practice. We would have put on our gasmasks and would have trooped out into the air raid shelters in the playground and sat in them before going back into school again.

All the main thoroughfares into the town had blockhouses and fortifications of big concrete blocks, maybe five feet square. There were two or three of them across the road with iron girders in them, and the same again on the other side, so traffic would have to zig zag round them.

There were fundraising activities such as Spitfire Week. There was a platform in Kildare Street, just opposite where the Bank Restaurant is now, they had a ‘thermometer’, which was red at the bottom, and as the money came in the ‘thermometer’ would have gone up and up until it reached a certain amount, so a Spitfire could be bought.

I remember the night of the Belfast Blitz, the siren went off, and it was a peculiar siren for air raids and when you heard that then you knew there was danger. We were living in the north end of the town, so off we went out the Crieve road and I remember distinctly hearing the German planes. They had a funny droning sound. Droning you know, it wasn’t a level sound, and I could hear them go over.It was so quiet you could hear the

thump thump of the bombs in Belfast. I think I did see the sky brighten up towards the north on the Crieve Road because it was high ground there.

There were also evacuee children at our school. One of them was Beryl Fisher who was in my class, when the war was over, she went back to Belfast.

Entertainment at that time was the radio and the cinema. On the odd occasion my mother would allow me to go to a matinee, I watched films such as Roy Rogers, Abbott and Costello and Frankenstein. On the radio, I listened to Children’s Hour, it was Toy Town, with Larry the Lamb and Mr. Growser. It came on at about 5.30pm and I would never miss it. I also remember pantomimes in the Town Hall, and Bobby Graham and Jack Sommerville who put on shows. Bobby Graham was terrific, a natural born comedian and the Town Hall would have been filled with people.

Work was more plentiful, and I remember my grandmother, who was not an elderly lady, getting a job in a canteen catering for the American soldiers. They used to employ local people, and I remember her working there, and the canteen was in Hill Street, where the Magnet Centre is now.

William McAlpine (right) and Norman McAlpine (left) playing outside their home on the Downshire Road, Newry. Courtesy of William McAlpine

Newry was fairly well off for rationing, and the farms around here produced a lot of foodstuff and there was never a shortage. Although we had to have our ration books and clothing coupons. The only thing that was rationed as far I could see, as a child aged eleven, was sweets. We were only allowed about 3 ounces a week for sweets, but I overcame that by jumping on my bicycle and going to Omeath. I filled my pockets full of sweets, and although the customs knew what we were doing, they never stopped us.

There was a large contingent of American troops stationed at Ashgrove, and there were Nissan huts all along there and the army had taken over a lot of buildings. That was the reason why we had to move out of the big house in Downshire Road as the army needed it coming up to D Day, and we moved to Sandys Street.

The American soldiers and some of the Welch regiments would have come to church and it was announced that families could invite some of them to their house. Bill Shelton, who was an American soldier, came over nearly every night of the week until they were all shifted off for D Day.

Everything settled back after the War and I got a job in 1948 in W&S Magowan’s Printers and stayed there for forty-two years.

A cub scout since the age of seven, William McAlpine (pictured standing, back row, second from left) at the 1st Newry Earl of Kilmorey scout camp in Mourne Park, Kilkeel, July 1944.

Courtesy of William McAlpine

Bill Shelton, an American soldier, was a regular visitor to the McAlpine home, pictured 19 August 1943. Courtesy of William McAlpine

A cub scout since the age of seven, William McAlpine (pictured standing, back row, second from left) at the 1st Newry Earl of Kilmorey scout camp in Mourne Park, Kilkeel, July 1944.

Courtesy of William McAlpine

Bill Shelton, an American soldier, was a regular visitor to the McAlpine home, pictured 19 August 1943. Courtesy of William McAlpine

World War II Air Raid Shelters in Newry

Noelle Murtagh

Noelle Murtagh

On the 1 September 1939, two days before war was declared, a blackout order was imposed in Newry to restrict lighting at night. New developments in warfare increased the risk of an aerial attack and the blackout aimed to make cities and urban areas difficult to be seen from the air. The threat of such an attack necessitated extensive Air Raid Precaution plans.

Air Raid Precaution (ARP) Wardens were appointed to ensure that blackout was maintained and to advise and direct the population in the event of an aerial attack.

A siren was installed on top of the Town Hall, which could be heard up to three miles away, to warn people that the Luftwaffe (German airforce) were approaching.

Newry Urban District Council requested air raid shelters for 5% of the population, approximately 600 people. They asked that they be in areas with high population densities. They suggested that shelters in children’s play centres in Needham Street, Kilmorey Park and Boat Street be converted. It was estimated that they would cost £75-£80 to convert. Mr Blaney, the Town Surveyor, invited tenders to build the shelters and the total cost of the air raid shelters came to £1094 10s 0d. Each air raid shelter was slightly different in design but would hold about 60 citizens. They were very basic, without lighting or running water and were only an emergency bolthole.

In total there were air raid shelters in 27 locations around Newry, including three near Linenhall Square. One was at Newry General Hospital,

Blockhouse on Rathfriland Road, Newry, now demolished. Courtesy of William McAlpine

another at Erskine Street Barrack gate and one was located at the bottom of O’Rourke’s Hill. Other notable locations included Marcus Square, Canal Street and High Street.

Other changes to Newry included massive reinforced gun emplacements called pillar boxes. Streets and bridges were partially blocked off with metal and concrete blockades known as “dragon’s teeth”.

Fortunately, Newry did not come under attack from the Luftwaffe; however, during the Belfast Blitz of April and May 1941 some of the 180 German Bombers involved were seen and heard flying over Newry. They flew across Carlingford Lough and headed north to Belfast. Fire services in Belfast were so overwhelmed, that crews from all over Northern Ireland, were sent to assist. On hearing of the horrific situation in Belfast, Irish Taoiseach, Eamon de Valera, sent fire engines from Dublin, Drogheda and Dundalk to assist, and these green fire engines were seen travelling through Newry.

Detail of air raid shelter, from plan of Newry General Hospital, early 1940s. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Detail of air raid shelter, from plan of Newry General Hospital, early 1940s. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Memories of Kilkeel during World War II

Matthew Murphy

Based on memories recounted by Matthew Murphy to Noreen Cunningham in March 2019.

I was just nine years old when the war broke out. We were not aware of what a World War meant, but everyone was very apprehensive and of course money was very tight.

As we had a grocery shop in Kilkeel, food rationing meant a lot of unpaid extra work for us; there were endless coupons, counting them and cutting them out from ration books. The custom you got was only from people who had their ration books with us. If there was anyone on holiday they had to go to the local food office for what was called an emergency card to be able to buy food. We had to comply with the regulations and serve them. This often meant that you were left short for your own customers, and then you had to go to the food office for an emergency supply card to fill the gap.

Whittens, who were wholesalers in Newry, were our main supplier of foodstuffs. Most commodities such as tea and sugar were got in bulk. This involved a lot of work each evening, weighing them out, tucking them into paper bags and getting them packed up and stacked on the shelves. It was difficult to portion out some foodstuffs particularly butter.

Just outside Kilkeel there was a restricted military area, and because I was delivering groceries to customers on the other side of that area on my shop bike, I needed a special pass from the military and my identity card to go in and out of the restricted area.

Due to the blackout, you had to have your windows blacked out with heavy curtains. Tommy Graham was employed by Kilkeel Urban District Council to check that all the shops closed on time.

There were very few private vehicles on the road because of the petrol rationing. Cars had a round metal cover that clipped over their headlights. The covers had slots which directed the light towards the ground.

Street lighting was severely restricted because of air raids, but we were very fortunate in south Down because we didn’t have any air raids.

There were air raid shelters located in the schools. There were rehearsals and demonstrations of what to do if the air raid sirens went off.

We did not carry gas mask at our school, but the other schools had them. I remember the pupils of Mourne Grange Preparatory School had gasmasks.

Halfway through the war, the American troops appeared. They wore different uniforms than the British military and had their own equipment, tanks and lorries. Initially, they took over all the large sheds, such as the potato stores around the harbour and parish halls as billets. The Americans were very generous and friendly, and the people liked them.

The airfield for the Americans at Greencastle was started during the war years and provided work and good wages, which in turn was good for the shops.

There was a gunnery school out along the shore. During target practice aircraft flew up and down continuously along the coast, towing a target about 200 yards behind the plane and when it passed the troops on the ground opened fire. The planes were lucky they weren’t shot down themselves! It was very noisy for people living in the vicinity and that went on continuously for weeks at a time.

There was a great sense of relief when the war was over. I don’t remember any official celebrations, but people were happy, as the war had been a bad experience for a lot of people particularly those who had someone killed in action.

There was no sudden improvement in business after the war, as food rationing continued for quite some time after that until things became more freely available.

Helpers at Y.M.C.A., Kilkeel, 1940s, pictured from left to right, are N. Hanna, M. Edgar, F. Chambers, A. Chambers, F. Girvan, W. Graham, J. Graham and M. McKee

Courtesy of Catherine Hudson

Helpers at Y.M.C.A., Kilkeel, 1940s, pictured from left to right, are N. Hanna, M. Edgar, F. Chambers, A. Chambers, F. Girvan, W. Graham, J. Graham and M. McKee

Courtesy of Catherine Hudson

Serving with the Irish Guards in World War II: memories of Lt. John Gough

Lt. John Gough was born in London in 1925. He spent his early childhood in India where his father, Hubert Vincent Gough, was Inspector General of the Nizam’s police force in Hyderabad. The family returned to England around 1933 when John Gough entered the Oratory Preparatory School in Oxfordshire and then Downside School in Somerset.

It was at Downside that John decided to join the Irish Guards. There was a strong connection with Downside and the Irish Guards stemming from the fact the Rev. Fr. J R (Dolly) Brookes, who was a chaplain to the regiment, was a Benedictine monk at Downside Abbey. John’s mother was also keen for him to join the Guards.

John joined in 1943 and began officer training with a Brigade Squad at Caterham. Accommodation at Caterham comprised Nissan huts with twenty young trainee officers in each with a sergeant in charge. A trained soldier looked after the squad. John received further officer training at various other camps before going to Scotland. In Scotland he was trained to command a Bren Carrier Platoon which carried armaments and supplies, and acted as stretcher bearers in combat. While he was in Scotland, in July 1944, John was ordered to join the 3rd Battalion Irish Guards in Normandy.

John had to make his own way to France. He crossed the English Channel in a smallish ship and landed at the Mulberry harbour at Arromanche. Once landed, he had to ‘thumb it’ until he met up with the Battalion and was given command of the carrier platoon.

When John met up with the Battalion, they were resting in an orchard preparing next day to go into action. John was asked by Col. J O E Vandeleur (known as Col. ‘Joe’), commander of the Battalion, to remain back as he had only arrived. The action took place at a farmstead called Pavee, near the village of Sourdeval, where casualties were heavy.

At this time John remembers travelling around in a captured amphibious German Volkswagen which had an engine and propeller at the back and was like a dodgem car to drive. He also remembers the Battalion feeling rather depressed at the numbers of officers which had been lost in the fighting.

Ken Abraham

Based on interviews with John Gough by Andrew Oglesby in March 2010 and Ken Abraham in February 2019. Lt. John Gough pictured at the time of his commissioning as an officer in the Irish Guards in 1943. Courtesy of John Gough

In the succeeding weeks the Battalion advanced with the Allied Forces across northern France towards Belgium. After the Liberation of Brussels, the Battalion, now known as the Irish Guards Battle Group 3rd Battalion, and under the command of Col. ‘Joe’ captured ‘Joe’s Bridge’, Bridge No.9 on the Bocholt-Herentals Canal on 10 – 14 September.

John was asked by Col. ‘Joe’ to do a reconnaissance on the other side of the bridge as it was suspected that enemy forces were still present. The following day the Battalion came under attack by German tanks, a counter-attack which transpired to be cover for enemy withdrawal.

The capture of Joe’s Bridge was the prelude to Operation Market Garden (17 – 22 September) which aimed to capture bridges to facilitate the invasion of Germany. The Dutch cities of Eindoven and Nijmegen were liberated. John was near the village of Elst in late September where the Battalion came under heavy shelling from German tanks and returned to Nijmegen for the winter.

John remembers the very cold winter of 1944. Members of the Battalion wore snow camouflage and high numbers of personnel were killed in accidents on the frozen roads. At this time John left the carrier platoon to become a Platoon Officer.

In April 1945, the 3rd Battalion crossed the Rhine into Germany and John led a night attack at the village of Gildehaus which was strongly held by the Germans. They had blown up a sea mine on the road in the village to impede the Allied advance.

Lt. John Gough in Brussels after the liberation of the city in September 1944.

Courtesy of John Gough

John remained in the Irish Guards until 1947. During a tour of guard duty at Hillsborough Castle he attended a New Year’s Eve Party at the Grand Central Hotel in Belfast, where he met his first wife, Lady Hyacinth Needham, daughter of the 4th Earl of Kilmorey.

After leaving his regiment, John worked for the Gezira Cotton Company in Sudan. John and Lady Hyacinth were married in July 1953 and came to live at Moore Lodge on the outskirts of Newry in the mid-1950s. He initially worked in the quarry industry before setting up a dairy farm at Moore Lodge which he carried on until his retirement c.1980.

Memories of growing up on an American Air Force Base

Mary Gallagher

Based on memories recounted by Mary Gallagher to Noreen Cunningham in March 2019.

World War II had an important impact on my family. In 1942 when Langford Lodge, near Crumlin, Co. Antrim, was opened as an airfield for the United States Army Air Force, my father, John McDermott, was one of many local people recruited by them. After the war ended, my father continued to work for the American Air Force for many years and that is how my two brothers and I, grew up in England.

Born in 1916, my father was originally from near Loughbrickland, Co. Down and he would probably have been in his mid-twenties when he started work with the American Air Force. His role at the base was varied, and he carried out many duties including caretaker, gardener, cook, cleaner and waiter.

When the war was over, the Americans left Langford Lodge and moved to Bovingdon, near Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire, England. Bovingdon Air Force base was owned by the Royal Air Force, but the Americans and the RAF had used it as a base for bombing raids during the war, and as a supply base. My father had moved with them to Bovingdon and he was given a job as caretaker in their ‘Mess Hall’ which was a communal central hall where the Americans used to socialise when they were off duty. The Mess Hall was part of a number of pre-fabricated huts and buildings that had been hurriedly constructed during the war.

In 1953 my father returned home and married my mother, Anna Mary McClorey. He had known her for many years, as she was also from the Loughbrickland area, and lived in the townland of Ballynaskeagh.

She went back with him to Bovingdon, where he had a farmworker’s cottage near the base and they had three children. My memories date from the late 1950s into the mid 1960s and my siblings and I went to school in Hemel Hempstead, but we grew up with American Air force families, who lived in adjacent cottages. I remember the Berger family, and the Matthews family, because they had four children who were all roughly the same age as us. They did not attend the same school as us, and were educated in their own school, on the base. American Air Force service families moved about a lot. Ruislip in Middlesex and Mildenhall near Stansted, Suffolk were two other large American Airforce bases.

John McDermott, pictured in the Mess Hall at Bovingdon air base, worked for the United States Army Air Forces at Langford Lodge during World War II. Courtesy of Mary Gallagher

As children growing up, we were always surrounded by American accents. The Americans had access to a lot of their own food, and my mother was introduced to real pasta spaghetti by her neighbours, who showed her how to cook it. They also gave us boxes and boxes of candy, bubble gum in little pink packets, and wee chocolates called Hershey’s Candy Kisses wrapped in silver tin foil.

My dad used to cut the grass and maintain the gardens near the Mess Hall and there was an air raid shelter just outside the Hall, it was made of brick and was dug into the ground. By the 1960s it still had not been fully demolished and we played in the wee small ‘rooms’ whose roof was long gone and open to the sky.

Near the Mess Hall I remember there was an office where two ladies, Brenda and Jill worked, a fully stocked library, a couple of billiard tables, a dart board, in the corner a large fish tank and a big red coca cola machine that dispensed ice cold coca cola bottles for 6d. On the base there was also a large chaplaincy, a gym for basketball and a tenpin bowling alley.

Another memory I have is of seeing the space capsule which came to Bovingdon in a large American transport plane and created great excitement. In February 1962 the capsule had carried U.S. astronaut John Glenn three times around the earth. He was the first American to orbit our planet from space.

I also remember Bovingdon airfield being used as a film set for movies. The Battle of Britain, 633 Squadron and The Dambusters were all filmed there. We had been used to the usual Anson and Dakota airplanes flying in and out, but when the movies were made we saw the real Lancasters and Spitfires.

The American Air Force left Bovingdon around 1963. My father got a job in an aeronautical factory near St. Albans, where he was well paid, but both he and my mother wanted to return home to be near their elderly parents. We left England for good in August 1965, when I was nearly eleven years old.

The space capsule, pictured at Bovingdon airfield, toured American Air Force bases in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Mary Gallagher

The space capsule, pictured at Bovingdon airfield, toured American Air Force bases in the early 1960s. Courtesy of Mary Gallagher

The Charles Murray Collection

The collection includes a wide range of material including correspondence, photographs, training notebooks, medals and other material which originally belonged to Sergeant Charles Murray who was killed on active service during World War II on 30 August 1944. The material was donated by the Murray family in 2015, with further material donated in 2018. The collection has been catalogued and a list provided in Appendix 1.

From Acton, near Poyntzpass, Charles Murray joined the Royal Air Force in 1936. He initially trained in England but, by early 1939, was in Palestine where he spent the early years of the War. However, by 1943 Sergeant Murray was being stationed at various RAF Stations in Britain and Northern Ireland. He was killed on the night of 30 August 1944 when the Lancaster Bomber, on which he was a Flight Engineer, was shot down during a bombing raid on Stettin in Poland.

The aircraft came down behind enemy lines, in a region which was to become Soviet territory. This meant that the Murray family and the relatives of the other crew members, all of whom were also killed, found it extremely difficult to get information as to what had happened to their loved ones who were listed as “missing”. Sergeant Murray was not confirmed dead until July 1945 and it was a number of years before the family were able to receive information that he was buried in Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery in Poland.

The collection includes letters which Charles Murray wrote to his family, mainly to his sister Annie. Although subject to strict censoring, they give some idea of life in the RAF during World War II. A few were written from RAF Ramleh in Palestine and one, written around Easter 1939, describes a period of leave in Tel Aviv which “beats anything in England with surf boards and boats”. Sergeant Murray’s correspondence shows that Tel Aviv was quite popular with members of the Armed Forces in Palestine when they had a weekend’s leave.

Sergeant Murray took part in the North African Campaign and a menu for a Christmas Dinner shows that he celebrated Christmas 1941 with No.6 Squadron at the Kufra Oasis in the Libyan Desert. This strategic location had been taken from the Italians by the Allies in the early months of that year. Correspondence dating from 1943 and 1944 shows that Sergeant Murray was back in Britain. In April 1944 he was at RAF St. Athan in south Wales which specialised in training Flight Engineers.

Among the more poignant pieces of correspondence is the telegram, dated 30 August 1944, which Mrs Emily Murray received informing her that her son was “missing”. Equally moving are letters sent to Mrs Murray by the families of the other crew members on the Lancaster Bomber expressing their support and

Ken Abraham

Sergeant Charles Murray in the late 1930s, see NMM:2015.30.132. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

sympathy; presumably, she was doing the same for them. Many of these letters document the efforts made by the families to obtain information about what had happened to their loved ones.

Included in the donation are a series of photographs which show Charles Murray with his RAF comrades and places which he visited in

Palestine. Of particular interest are his training books which give an insight into his training as an RAF Flight Engineer. Sergeant Murray’s medals have also been given to the Museum. These were never awarded to him and were sent to his mother after the war ended.

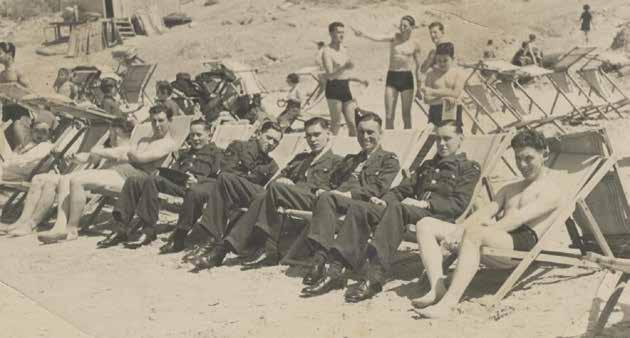

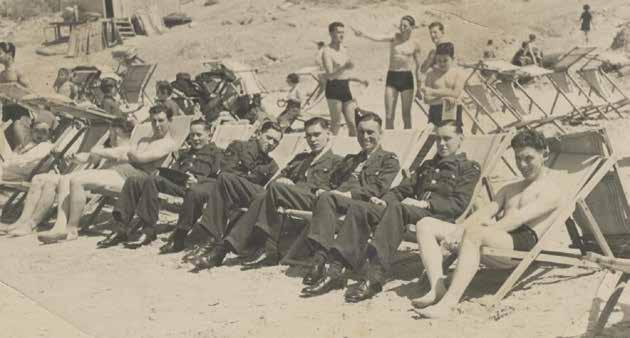

Sergeant Charles Murray (seated in deck chair, third from left) with his comrades on a beach in Tel Aviv. On the reverse of the photograph, Sergeant Murray wrote “those chaps [in uniform] on my left have just arrived here.” See NMM:2015.30.95 Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Royal Air Force No. 6 Squadron photographed in 1940, see NMM:2015.30.86. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Sergeant Charles Murray (seated in deck chair, third from left) with his comrades on a beach in Tel Aviv. On the reverse of the photograph, Sergeant Murray wrote “those chaps [in uniform] on my left have just arrived here.” See NMM:2015.30.95 Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Royal Air Force No. 6 Squadron photographed in 1940, see NMM:2015.30.86. Newry and Mourne Museum Collection

Appendix 1 - The Charles Murray Collection

List

compiled by Noreen Cunningham

ITEM DESCRIPTION

NMM:2015.30

30.1

Letter From Charles Murray, C. Flight, 6 Squadron, RAF Ramleh [Ramla], Palestine, to ‘Dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie), dated 16/1/1939. Discusses an insurance case, domestic family matters and the whereabouts of George Wilson, presumably in the Armed Forces in Palestine.

30.2 Letter From Charles Murray to ‘Dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie), no address, not dated but probably around Easter 1939. Discusses going to church, family matters and going to Tel Aviv: “it beats anything in England with surf boards and boats. We do not get down here often but it is a bind carrying a revolver”.

30.3 Letter From Charles Murray to Annie (his sister), dated 12/9/1939, no ad dress. Discusses censorship of letters, family matters and church going.

30.4 Letter From Charles Murray to ‘dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie), C. Flight, (6) Squadron, Ramleh, Palestine, not dated but probably late 1939. Discusses possibility of sending a Xmas present home, church going and refers to going for a weekend to Tel Aviv. He mentions that “The only bother going out here is the fact that one has to wear uniform and revolver and it makes a bad impression.”

30.5

Letter From Charles Murray, 228 Squadron, RAF Station, Lough Erne, Northern Ireland to his sister, Annie, dated 1/1/1943. Refers to arrival at the RAF Station at Lough Erne, collection of suit by Paddy and New Year greetings

30.6

Letter From Abraham Fish, Hotel Fish, 66 Hayarkon Street, Tel-Aviv, Palestine to Mr [Charles], Murray dated 27 August 1940. Refers to a camera which Charles Murray had lost while staying at Hotel Fish.

30.7

Letter From Charles Murray, 228 Squadron RAF Station, Home Forces, to his sister, Annie, dated 5 March 1943. Thinks it is unnecessary from him to write so often as he is now stationed near home. Discusses family matters.

30.8

Letter From Charles Murray, No.2 S of TT Hut P.6, Cosford, to his sister, Annie, dated 21/4/1943. Refers to his arrival at RAF Cosford (in Staffordshire) and says he has asked to be posted near home to help with the harvest.

30.9

Letter From Charles Murray, 3 Wing Hut P6, 136 Entry F.II.A., RAF Cosford, Staffs, to ‘Dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie), dated 3.6.43. Refers to going on a weekend to London, domestic matters and Cassie’s wedding.

30.10

Letter From Annie Murray, Acton, Poyntzpass, Co. Armagh, to Charles Murray, dated 1st July 1943. Refers to sending a parcel, cutting hay and going to a dance in the Legion Hall.

REFERENCE

30.11 Letter From Charles Murray, No:3 Wing Hut P.6. F.II.A , RAF s of TT Cosford, Staff., to Annie Murray, not dated (probably 1943). Refers to a weekend with Joe in Liverpool, domestic matters and reports that his course is almost finished.

30.12 Letter From Charles Murray, c/o Sgt’s Mess Lindholme, Nr Doncaster, Yorks, to ‘Dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie), dated 15/7/1944. Refers to not having received any letters from home, would like Paddy to get him a motor cycle, Kevin to send him cigarettes or tobacco and domestic matters.

30.13 Letter From Charles Murray, No 2 Sgt’s Mess, Hemswell, Lincs, Nr Gainsboro, to ‘Dear Sis’ (his sister, Annie) dated 16/8/1944. Thanks his sister for a parcel and cigarettes, harvest and hopes to get a reply from her before ‘I leave here which should be in about ten days.’ Written on RAF notepaper with crest on top left side of page.

30.14 Letter From J.G. Carter, RAF Station, Elsham Wolds, Barnetby, Lincs., to Mrs Murray, dated 31 August 1944. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray has been reported as ‘missing from operations.’ J.G. Carter is an RAF Catholic Chaplain.

30.15 Letter From A.R. Dunton, Sunnyside, Bentinck Road, Altrincham, Ches., to Mrs Murray, dated 4 September 1944. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray is missing. A.R. Dunton’s son, Frederick Ross Dunton was also on the Lancaster crew.

30.16 Letter From Charles Evans, Air Ministry (Casualty Branch), 73-77 Oxford Street, London, W.1, to Mrs Murray, dated 7 September 1944. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray “is missing as the result of air operations on the night of 29/30 August, 1944, when a Lancaster aircraft in which he was flying as flight engineer set out to bomb Stettin (Poland) and failed to return.” Enquiries about him are being made through the International Red Cross Committee.

30.17 Letter From A.E. Peake, Pleck, Walsall, Staffs., to Mrs Murray, dated 7 September 1944. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray is missing. Written on behalf of the family of Airgunner Sgt. James H. Peake who was also a crew member of Charles Murray’s plane.

30.18 Letter From Mrs Lilian Carey, 39 Chilcott Road, Knotty Ash, Liverpool, 14, to Mrs Murray, dated 10 September 1944. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray is missing. Mrs Carey’s husband, J.J. Carey, was also a crew member of Charles Murray’s plane

30.19 Letter To Mrs Murray, December 1944, letter incomplete and not signed. Written from Canterbrae, 57 North Circular Road, Belfast. Expresses sympathy to Mrs Murray on the news that Charles Murray is missing.

30.20 Letter From Margaret Ampthill, 7 Belgrave Square, London, S.W.1, to Mrs Carey, dated 29 December, 1944. Refers to Sergeant J.J. Carey as missing and discusses report received from the International Red Cross Committee in Geneva about six airmen losing their lives.

30.21 Letter (photostat) Not signed but probably from Margaret Ampthill, 7 Belgrave Square, London, S.W.1, to Mr Dunton, dated 27 December, 1944. Refers to Flight Lieutenant Dunton as missing and discusses report received from the International Red Cross Committee in Geneva about six airmen losing their lives.

30.22 Letter From Margaret Ampthill, War Organisation of the British Red Cross Society and Order of St. John of Jerusalem, 7 Belgrave Square, London, S.W.1, to Mrs Murray, dated 2 February 1945. Refers to Sergeant C.M. Murray as missing and discusses report received from the International Red Cross Committee in Geneva about six airmen losing their lives.

30.23 Letter From J.A. Smith. Air Ministry (Casualty Branch) 73-77 Oxford Street, London, W.1, to Mrs E. Murray, dated 24 July 1945. Informs Mrs Murray that in view of the lapse of time and the absence of news relating to Sergeant C.M. Murray, he is now presumed dead as of 30 August 1944.

30.24.1 Letter From A.R. Dunton, Sunnyside, Bendinck Road, Altrincham, Ches., to Mrs E. Murray, dated 27 September 1945. Informs Mrs Murray that he has made repeated enquiries to the Air Ministry about the missing Lancaster and crew, but no further information is available. Explains that the difficulty lies in that the bomber came down over Stettin which is in the Russian occupied area. He had written to Mr Molotov of the Russian Embassy, but no further cooperation was forthcoming. He will make further enquires at the Air Ministry. Attaches a copy of the letter he had written to the Air Ministry on 24 July 1945 (NMM:215.30.24.2)

30.24.2 Letter (photostat) From A.R. Dunton, Sunnyside, Bendinck Road, Altrincham, Ches., to the Air Ministry, dated 24 July 1945. Requests further information on his son and other members of the crew of the Lancaster which did not return from a raid on Stettin on 29 August 1944. Outlines information already received and refers to confusion regarding a seventh crew member and identification of his son.

30.25 Letter From F. Bannocke, Office of Air Attache, British Legation, Strandvagen 82, Stockholm, to Mrs E. Murray, dated 16 November 1945. Informs Mrs Murray that a search through their records has not uncovered any details about the fate of her son.

30.26.1 Letter From A.R. Dunton, Sunnyside, Bendincke Road, Altrincham, Cheshire, to Mrs E. Murray, dated 31 May 1946. Informs Mrs Murray that his latest enquiries about the missing Lancaster have not met with much success. Encloses a letter from Air ViceMarshall Harries (NMM:2015.30 26.2).

30.26.2 Letter (photostat) From Air Vice-Marshall (address not given) D. Harries to Mr Dunton, dated 18 May 1946. Refers to information from captured German documents that Mr Dunton’s son’s aircraft crashed near Sparrenfelde, west of Stettin. The Russians have offered search facilities and enquiries will be made by the Royal Air Force Missing Research and Enquiry Service but search in Russian occupied territory will not begin just yet.

30.27 Letter (photostat) From A.R. Dunton (address not included) to G.M. Haslam, Air Ministry, dated 19 March 1948. Refers permission being granted for one Royal Air Force officer and one Army officer to go into Poland and be attached to the Polish Research teams and hopes the Stettin and Sparrenfelde areas will be included in the search. Refers to a letter to be sent, written in German, to the Mayor of Sparrenfelde asking if they can supply any information about the aircraft which came down near their village.

30.28 Letter (photostat) From A.R. Dunton, Sunnyside, Bendinck Road, Altrincham, Cheshire, to Mrs Murray, dated 19 March 1948. Refers to a visit made by A.R. Dunton to the Air Ministry on 10th March where he saw original German documents relating to the lost Lancaster Bomber. Documents stated that the Lancaster came down west of Sparrenfelde, 8 1/2 kilometres west of Stettin and seven crew lost their lives. The bomber was carrying a special camera, radar equipment and high explosive bombs. Includes extract from a letter from G.M. Haslam reporting permission had been given for one RAF officer to be attached to Polish Research Teams. Mentions that letter had been sent to Mayor of Sparrenfelde asking for assistance in obtaining news. Adds in handwritten PS “I have tried several times to get you a copy of the London Gazette dated 1 Jan 1942 so that you could have this record of Charles destination.”

30.29 Letter Proforma letter from F. Higginson, Imperial War Graves Commission, Wooburn House, High Wycombe, Bucks., dated 7 March 1953 to Mrs E. Murray. Requests information for the erection of a headstone [to Charles Murray]. Originally accompanied a form.

30.30 Letter From F. Calmut, Imperial War Graves Commission, Wooburn House, High Wycombe, Bucks., dated 16 April 1956 to Mrs E. Murray. Refers to renumbering of graves in the Posen Old Garrison Cemetery in Poland. Gives new number for grave of Sergeant Charles Murray.

30.31 Letter Proforma letter from representative of the Secretary, Imperial War Graves Commission, Wooburn House, High Wycombe, Bucks., dated 21 August 1956. Indicates that “relatives wishing to visit war graves would be welcomed by the Polish people.” Provides information on travel by boat from Hull to Gdynia twice monthly.

30.32 Letter Proforma letter of sympathy sent from Buckingham Palace to Mrs E. Murray (not dated). Printed signature of King George VI.

30.33 Letter From Charles Murray, Hut A8 2 Wing, RAF St Atham, Glam., S. Wales, to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie), dated 24 April 1944. A thank you letter for a parcel containing a cake (nibbled by mice) and cigarettes. Says that he hopes to get home on leave.

30.34 Letter From Charles Murray, c/o Sgt’s Mess, Lindholme, Doncaster, Yorks., to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie), not dated. Refers to domestic matters including Pat Cavanagh’s marriage, possible acquisition of motor bike and sending a parcel to Mrs Henshall in Cheshire.

30.35 Letter From [Mrs Lilian Carey] (not complete), 39 Chilcott Road, Knotty Ash, Liverpool 14, dated 4.1.44 (date is a mistake, should read 1945). Refers to missing crew of bomber.

30.36 Letter Air Mail letter card from Charles Murray, 6 Squadron RAF, Middle East Forces, to Annie, his sister, Egyptian post mark, dated 21st October 1941. Expresses thanks for letter and card. Refers to deaths of “my old friends” at home.

30.37 Letter From Charles Murray, 3 Repair Section, ARS (13 M.U.), Henlow Camp, Bedfordshire, to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie) dated 24 October 1943. Refers to domestic matters and hopes to get nine days leave in about two weeks instead of leave at Christmas.

30.38 Letter From Charles Murray, Hut 010 4 Wing, 56 Entry F.II.A., RAF St. Atham, Glam., S. Wales, to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie), not dated. Mainly concerns domestic matters including recovery of Raymond from an accident. Mentions censorship of letters and parcels and that they “have also been warned to keep our communications as brief as possible. Hopes to get leave and to “arrive in time to get a few extra jobs with the harvest”.

30.39 Letter From Charles Murray, Hut 010 4 Wing, 56 Entry F.II.A., RAF St. Atham, Glam., S. Wales, to his sister, Annie, not dated. Mainly concerns domestic matters including the death of a relative, possibly his aunt Jessie and thanking her for the shamrock.

30.40 Letter From Paddy and Paul, 114 Edward Street, Lurgan to Charles Murray, not dated. Refers to domestic matters and death of Aunt Jessie. Written on receipt from P.J. Murray, Electrical Contractor.

30.41 Letter From Marie Loughlin, Church Street, Poyntzpass, to Charles Murray dated 27 March, (year absent). Expresses thanks for letter of sympathy sent to Tom on the death of his mother. Refers to planting of spring crops “at the present time all hands are busy preparing to get the crops in, which is a big item everywhere now”.

30.42 Letter From Joyce, 50 Sandhurst Court, Acre Lane, Brixton, S.W. 2 to Charles Murray, dated 22 June 1943. Expresses disappointment that Charles failed to turn up on Saturday.

30.43 Letter From Sr. M. Patrick D.C. (Prioress), Carmelite Monastery of Mary Immaculate and St. Therese, Glenvale, Newry, Co. Down, to Mrs Murray, dated 20 March 1941. Expresses thanks for her “generous gift” and will “remember you and all your intentions in our prayers and above all Charles”.

30.44

Postcard Showing Royal Avenue from Castle Junction, Belfast sent from Charles Murray to P.J. Murray, dated 4 November 1936. “Passed O.K. Sailing tonight for Oxbridge. Will write when I land. Going through London”.

30.45 Postcard Featuring RAF Camp, West Drayton sent by Charles Murray to “Dear Sis”, (his sister, Annie) not dated. Sent after his arrival at West Drayton and says they are staying there until the following week.

30.46 Letter (photostat) From Charles Murray, 6 Squadron RAF, Middle East Forces, to Annie, his sister, dated 28 September 1941. Refers to mother’s illness and requests to be contacted by cable if any change in her condition. Informs his sister not to expect him home that year as “the term has been changed to four years overseas which will complete my time.” Written on proforma notepaper.

30.47

Letter (photostat) From Charles Murray, 6 Squadron RAF, Middle East Forces, to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie) dated 23 January 1942. Relates to domestic matters, thanking her for her letter, and states that he had not received any xmas mail yet.

30.48 Letter (photostat) From Charles Murray, 6 Squadron RAF, Middle East Forces, to “Dear Sis” (his sister, Annie) dated 25 May 1942. Relates to domestic matters, and refers to letters from his cousin, Sheila.

30.49 Letter (photostat) From Alex Harding, No 7 Elgin St., Woolwich, N.S. Wales, Australia, to Mrs Murray, dated 26 November 1944. Expresses thanks to Mrs Murray for her letter of sympathy and hope, and expresses hope that their sons will be found.

30.50 Telegram From Charles Murray to Miss Murray, dated 7 December 1940. “Happy Xmas Dont worry. Charles Murray.”

30.51 Telegram From Charles Murray to EFM Murray, dated 15 June 1941.“All well Hope same Charles Murray.”

30.52 Telegram From [Charles Murray] to Murray, dated 10 July 1942. “My thoughts are with you please write many thanks for letter Murray.”

30.53 Telegram Telegram from Charles Murray to Miss Ann Murray, dated 13 June 1944. “Hope family well moving to new camp write later love Charles Murray”.

30.54 Telegram From Aeromantics Kermington to Mrs Murray, dated 30 August 1944. Informs Mrs Murray that “Sgt Charles Malachi Murray is reported missing from operations on the night 29/30 Aug 44”. Letter follows immediately and any information will be forwarded. Requests that she does not speak to press.

30.55 Telegram From Charles Murray to Mrs E Murray, date not legible. “All’s well hope same Charles Murray.” 30.56 Envelope Addressed to Charles Murray, Acton, Poyntzpass, Co. Armagh, N. Ireland, date not legible. RAF censor stamp at bottom left-hand corner. Manilla, “On His Majesty’s Service”.

30.57

Christmas card Signed “From Auntie & Mollie To Charlie with love” Embossed green and yellow floral design with violets on cellophane window on front, “Loving Thoughts” with green ribbon. 30.58

Christmas card Signed “From Molly To Charlie with love”. Polyethylene front with two robins and floral design and greeting “With every good wish”. 30.59

Christmas card Signed “From Charlie”. Picture of Christ with John the Baptist and two lambs on front with greeting “Greetings from the Holy Land”. 30.60

Postcard Illustrated with cartoon of soldier with orange trees captioned with message: “Greetings from the Middle East” and “READY TO PICK”. 30.61

Postcard Illustrated with cartoon of soldier in Scots military uniform and a gentleman in Arab dress captioned with message: “Greetings from the Middle East” and “WHEN TWO SKIRTS . 30.62

Postcard Featuring cartoon of Mussolini captioned with message “FINITO MUSSOLINI” and “TURN IT ROUND”. 30.63 Christmas Card Signed “To Mother From Charles”. Depicts cartoon of aeroplane and pilot and greeting:” Here’s hoping - that you’ll have a MERYY XMAS and A HAPPIER NEW YEAR” and “SERVING WITH THE RAF MIDDLE EAST, XMAS 1941”.

30.64 Prayer card With prayer “GOD KEEP YOU”. Decorated with a Celtic design. Handwritten on reverse “To Annie From Evelyn”. 30.65 Menu Souvenir Christmas menu from ‘A’ Flight, No.6 Squadron Detachment Royal Air Force. Kufra Oasis, Libyan Desert, dated 1941.

30.66 Menu Souvenir menu from Royal Air Force Station, Ramleh [Ramla], Palestine, dated Christmas 1939. Decorated with RAF crest and scenes of life in Palestine. 30.67 Menu Souvenir menu from Royal Air Force Station, Ramleh, Palestine, dated Christmas 1940. Decorated with RAF crest and images of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. 30.68 Menu Souvenir menu from Silver Jubilee Dinner held for No. 6 (B) Squadron, at Royal Air Force Station, Ramleh, Palestine, dated Tuesday 31 January 1939. Decorated with RAF Bomber Squadron crest and cartoon. Signatures of guests on reverse.

30.69 Certificate From The Pioneer Total Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart presented to Patrick Murphy, dated 20 January 1935. 30.70 Badge Pink fabric Sacred Heart badge with beaded edge, and small silver medal. 30.71 Badge Circular pink fabric Sacred Heart badge. 30.72 Driver’s license With red cover issued to Charles M. Murray, Acton, Poyntzpass, issued 11 August 1937 until 10 August 1938. First change of address, Hut 11 78 Squadron, RAF Dishforth, second change of address, No. (6) Squadron, RAF Detachment, Haifa, Palestine. 30.73 Savings book Post Office Savings Bank Book issued to T.[Charles] M. Murray, Hut 417, No.2T Wing, RAF Henlow, Beds, dated 1937. 30.74 Instruction card Providing instructions to officers and airmen of the Royal Air Force regarding precautions to be taken in the event of falling in the hands of the enemy, reprinted May 1940. 30.75 List Records seven names and addresses of Next of Kin and religion of Charles Murray and his fellow RAF crew members, not dated. 30.76 Medical slip Issued to Charles Murray, dated 13 April 1942.

30.77 Leaflet Commonwealth War Graves Commission leaflet with order form explaining that families can purchase copies of cemetery and memorial Registers containing the name of their relative killed in the 1939 - 1945 War. Order form refers to the Register of ‘Russia & Poland’ which includes “535937 Sgt. Charles Malachi Murray, R.A.F., 30.8.44 Poznan Old Garr. Cemetery”.

30.78 Notice Warning Notice in English and Arabic issued by R.N. O’Connor, Military Commander, Jerusalem District, warning of military operations.

30.79 Notice In Arabic, on pink paper. 30.80 Drawing Charcoal drawing of Charles Murray in profile. Wearing RAF cap and uniform. Signed at bottom left-hand corner, not legible.

30.81 Notebook Royal Air Force training notebook compiled by Charles Murray. Handwritten with pencil drawings and diagrams of aircraft parts. Contains an Aeroplane Maintenance Form, dated 1 November 1937.

30.82 Notebook Royal Air Force training notebook compiled by Charles Murray. Handwritten in pencil and ink with drawings. Not dated.

30.83

Notebook Royal Air Force Observer’s and Air Gunner’s Flying Log Book compiled by C [Charles] Murray. Contains details of flying exercises in Palestine, January 1939 - December 1941. 30.84 Photograph Black and white photograph of Charles Murray wearing Arab headdress. 30.85 Photograph Black and white photograph showing A Flight 6 Squadron, 1940, in front of an aircraft. Charles Murray pictured back row, 5th from left. 30.86

Photograph Black and white photograph showing 6 Squadron, 1940. 30.87 Photograph Black and white photograph showing 6 Squadron, 1942. 30.88 Photograph Black and white photograph possibly showing 6 Squadron with an aircraft. 30.89 Photograph Black and white photograph showing squadron, possibly at a Christmas party. 30.90 Photograph Black and white photograph possibly showing squadron, possibly at a Christmas dinner. 30.91 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Charles Murray (on right) with another gentleman in civilian clothing at a pyramid in Egypt. 30.92 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Charles Murray in uniform, in a military cemetery at the grave of OB Leut Haugg, German Flying Corps. 30.93 Photograph Black and white photograph showing members of A Flight with lorries. 30.94 Photograph Black and white photograph showing members of C Flight hockey team. 30.95 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Charles Murray with comrades on beach at Tel Aviv. 30.96 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Charles Murray with comrades in camp. 30.97 Photograph Black and white photograph of formation flying A Fight, 6 Squadron. 30.98 Photograph Black and white photograph showing aerodrome camp at Hiafa [Haifa] in 1938. 30.99 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Ramleh [Ramla] village. 30.100 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Jaffa Gate, Jerusalem. 30.101 Photograph Black and white aerial photograph showing the Mount of Olives. 30.102 Photograph Black and white aerial photograph showing the Garden of Gethsemane. 30.103 Photograph Black and white aerial photograph showing ruins at Jerash. 30.104 Photograph Black and white aerial photograph showing ruins at Jerash 30.105 Photograph Black and white photograph showing crest of RAF 6 Bomber Squadron. 30.106 Photograph Black and white photograph showing Charles Murray in RAF uniform with family group. 30.107 Photograph Colour photograph of Charles Murray’s grave in Poland. [NMM:2015.30.108 - NMM:2015.30.131 relates to the Murray family electrical business]

30.132 Photograph Head and shoulders photograph of Charles wearing his RAF cap and uniform c. 1940.

30.133 Medals