11 minute read

Editorial

Barry Flanagan, Gallifa Study XII, 1992, edition of 8 + 2 ACs, bronze 28.9 × 14.9 × 14 cm; courtesy of Barry Flanagan Estate

Alice Maher, Berry Dress, 1994, Rosehips, cotton, paint, sewing pins, 25 × 32 × 24 cm; collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, purchase, assisted by funding from Maire and Maurice Foley, 1995; courtesy of IMMA

stayed with me. I have found myself many times looking at the catalogue of the Dublin show and stopping at that page, that being one of the important aspects of a work of art, something that operates upon you, if I can put it like that, over time. Fergus Feehily Berry Dress (1994) Alice Maher We see an upright child’s dress – cotton, buttoned, with pleated sleeves, stiffened with paint. The skirt of the dress is crafted from rosehip berries and pins; it sits on a raised glass shelf where it spills and pools, like globulous, congealed blood drops. At first glance, and from a distance, the dress – perched high, overhead – is a strange, floating, juju object. But when you move closer and view it from below, this little dress pulls the viewer into a disturbing, uncanny, aesthetic entanglement. Peering up into a dress is a transgression of socio-cultural norms, a taboo. But with this sculpture, one has to take up this position of transgression for Berry Dress to reveal its secrets. Not only is the inside and the outside of the sculpture simultaneously, ominously, present to vision. From this somewhat perverse position, the viewer can also see that the pins which pierce the cotton material to stitch the rosehip berries to the skirted dress would pierce the flesh, should the dress be donned. This is a baby’s dress. And it represents danger, and threat. The inception, execution and reception of Berry Dress cannot be separated from the social context of the 1990s in Ireland, a time during which Church and State mandated sanctions on divorce and contraception shaped the sexual mores and behaviours of the nation. The rosehip is the berried fruit of the rose flower and the fruit is the sexual organ of the plant. The hip berry forms as the result of successful pollination: the rosehip is, both literally and symbolically, the plant’s pregnancy. Whilst the dress represents the oppressions that the body – and, with regard to reproductive rights, the female body most particularly – were subject to since the foundation of the Irish State, it also speaks to us through time, to remind us of the unacknowledged and unspoken perils and dangers of childhood as well as its joys and freedoms. The hairs hidden inside the rosehip berry can be used as itching powder, a substance that Maher recalls formed part of her childhood pranks with friends. The pins concealed inside Berry Dress not only, then, signal threat but also the glorious, subversive irreverence of children’s play. The dress, fashioned from berries garnered from ditches, is also a memory conduit for the oppressive labour of living in the countryside, of coping with and managing nature. But it also recalls us to youthful days spent picking berries, the sensorial delight of squashing these fruits between pincered fingers, the anticipation of sticky juices running over fingers, staining tongues. Over the years, the rosehip berries have shrivelled so that the sculpture takes on a fetish or relic-like status that provokes reflection on the relationship between time, memory, maturity and ageing, of both the individual body and the collective Nation body. Yet, Maher’s Berry Dress is not only a holder for memories of a recent past; memory persists through time to connect the past to the present and the future. Berry Dress labours through such “memory work”, embodying, visibilising and corporealising both the passage of time as well as the transgressive potential of memory to prod, irritate, rattle and provoke turbulent emotions, those feelings that are ever-present and always on the verge of erupting into present time. Tina Kinsella Perpetual Motion (1996) Rachel Joynt & Remco de Fouw THE GENIUS OF Rachel Joynt and Remco de Fouw’s quite monumental sculpture – commissioned by Kildare County Council under the Per Cent for Art scheme – is for me, mainly in what it is not. The work is not made of metal, it has no sharp angles, it is not a sculpture of yet another equine figure (the curse of Kildare public sculpture); in fact, it is not figurative at all, but is uniquely conceptual. Joynt and de Fouw have cleverly produced a very site-specific and roadthemed sculpture relating directly to the commission. The hollow Ferro-cement sphere, located on a busy roundabout, replicates the road system that surrounds it on the Naas dual carriageway. With arrows indicating the flow of traffic around it, Perpetual Motion is the most playfully assertive of public sculptures. This is no easy task for an artwork unable to be experienced while static. Seen at speed through windscreens, contemplating the artwork is not really an option. Brilliantly aware of these viewing conditions, Perpetual Motion taps into the absurdity of the busy commuter, as well as early romantic notions of the autobahn. Jonathan Carroll The End and The Beginning I (1997) Kathy Prendergast THERE ARE AESTHETIC minefields in making artwork, IEDs that threaten to blow your career into smithereens particularly if you are a woman, a mother and you choose as your subject matter the historically undervalued experience of childbearing and motherhood. In the work The End and The Beginning I (1997), a delicate, gentle celebration of growing and ageing, Kathy Pendergast knowingly enters the fray, wending her way with supreme skill. Using the simplest of materials, she evokes the absent body, allowing the viewer to imagine, celebrate or grieve. So much fine balancing, evocation not explication, and at the same time the work is filled with humanity and common understanding. An arte povera work using a simple Mothercare baby’s bonnet. I remember buying exactly the same bonnet for my own baby, undoubtedly one of the reasons why I love this work so much. The fine, wisp-like hair sewn into the bonnet brings to mind the tousled warmth of a baby’s head and hair, and at the same time the frail brittleness of old age. The End and The Beginning I provokes so many memories; a small Van Dyke oil study, The Princesses Elizabeth and Anne, Daughters of Charles 1, bonneted and entitled with pearls around their necks. We can remember them, or we can go to the soggy fens of Northern Denmark, yielding up Bronze Age Tollund Man, his hanged and collapsed body crowned with a beautiful pointed leather cap. All ends and all beginnings. Cecily Brennan

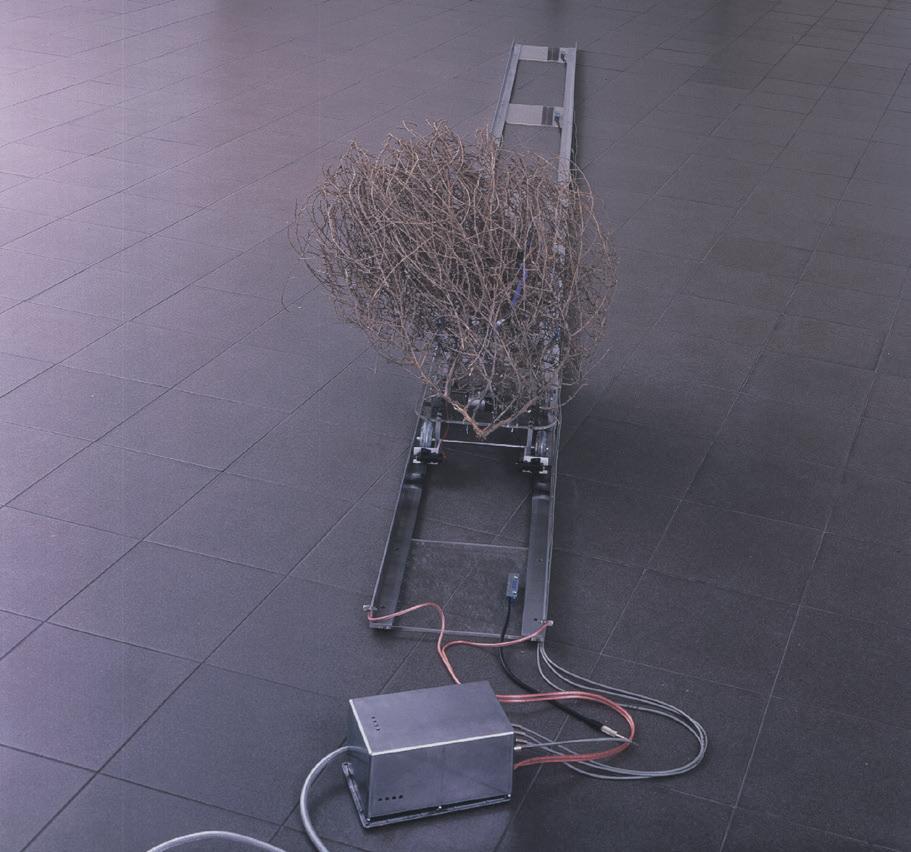

Stray (1997) Siobhán Hapaska

SIOBHÁN HAPASKA’S Stray (1997) was one of an ensemble of sculptures she presented at that year’s Documenta, the sprawling five-yearly exhibition in the small German city of Kassel, which remains one of the two most significant such events on the international art calendar. (The other is the Venice Biennale where Hapaska represented Ireland, alongside Grace Weir, four years later). Curator Catherine David’s historically recondite Documenta X included an unusually small number of younger artists. So, for Hapaska, then in her early 30s, to be offered a substantial gallery of her own in the Documenta-Halle was a serious accolade. Stray comprises a short stretch of aluminium track on which a genuine American tumbleweed, attached to a motorized support, shuttles back and forth endlessly, a long way from home, while lodged in the brittle tangle of its branches is a polystyrene cup (a

Siobhán Hapaska, Stray, 1997, American tumbleweed, copper, aluminium, electronic components, 67 × 70 × 500 cm; courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery

Lorraine Burrell, Consumed Utterances, 1998, fibreglass and resin, speakers, 27 cm × 22 cm × 40 cm; courtesy of the artist

Eilis O’Connell, Carapace, 2018 edition; photograph by Donal Murphy, courtesy of the artist and Scott Tallon Walker

second version of the work swapped this out for a length of blue ribbon). While Hapaska herself tends to emphasise the sculpture’s intimations of mobility, there is no denying that the tumbleweed’s freedom of movement has been seriously compromised in the process of its translation from the wideopen plains to the art gallery. Like much of this artist’s work over the past quarter of a century, Stray invites us, succinctly and with disarming levity, to consider a bundle of serious concerns: the nature-culture dynamic, the tension between motion and stasis, the question of displacement, differences between native and alien, and problems of origins and roots. Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith Consumed Utterances (1998) Lorraine Burrell IN THE SPRING of 1998, Derry’s Context Gallery (the CCA as it’s now known) held a show of Belfast artist Lorraine Burrell’s then recent work, titled ‘Consumed Utterances’. The central piece was a small, ridiculous sculpture which gave voice to diverse thoughts on physical and intellectual sustenance. Its cleverness, couched in puerile absurdity, placed it firmly in the Dada tradition. The scarlet resin object, ovoid with two protuberances, was described by me at the time as: … looking like an hermaphrodite stomach, from which emanates a recording of a babbling Pinky and Perky voice, reciting quotations both profound – Descartes’ “I think therefore I am” – and absurd – Ohio Express’ “Yummy yummy yummy, I’ve got love in my tummy/ and it makes me feel alright” … interspersed with sounds of burping, farting, babyish giggling and the occasional “fuck off – whoops! …” (CIRCA Issue 84, Summer 1998, p.57). Quotations also included Shakespeare and Philip Sidney, whose “sweet food of sweetly uttered knowledge” defines the nature of the object’s monologue. The work was accompanied by staged photographs of the artist interacting with the work – in one chatting amiably and in the other sharing a mutual sulk. This has continued to be a characteristic of much of her work since – photographic records of her relationships with her own sculptural production. Art is thus saved from being alienated from its maker and instead a symbiosis is established with the fruits of her labour. I loved this piece at the time and, looking back on it now, I love it all over again. Colin Darke Carapace (1999) Eilis O’Connell AS IS EVIDENT in this relatively early sculpture, a common feature of O’Connell’s work is its inherent dynamism, whether in disclosing the inner surface of Unfurl (2000 and 2018) or initiating the vector-like flight of Reedpod (2006). For any given motion there exists potential for its opposite, a dualism enacted in Carapace, with its two distinct forms united in perpetual motion. Like the familiar yin-yang symbol, these are spiral-bound, the origin of each arising from the other. It is a choreography the sculptor returned to in 2016 and 2018, with miniature bronze, steel and silver editions. Dualism is integral to the lived world, where language articulates our focus on the sameness and difference between ourselves and ‘other’, and between things. It is an environment in which forces of order and disorder interact, and species thrive by devising means of protection. The momentum of this piece suggests autonomy from an ever-changing context. Made from stainless steel, with some parts woven, the ‘carapace’ of the title refers to the hard layer that covers and safeguards animals such as crabs and turtles. While metals (especially bronze) are favoured by O’Connell, her repertoire of materials also includes lead, resin and fibreglass. Susan Campbell Ghost Ship (1999) Dorothy Cross I’LL ADMIT IT – I never saw this work at the time, but undoubtedly felt its presence and sometimes imagine it as I look out to the Irish Sea from the Northside. I like to repeatedly trace the moments when Ireland began to consider its vision for public art as one which was intrinsically linked to contemporary art practice. The year 1997 saw a move to revise the National Guidelines for Per Cent for Art Scheme, in recognition of new artforms and the introduction of the Nissan Art Project Award. This brave new initiative, launched in association with IMMA, provided significant investment and opportunity for the creation of new work that would represent an ambitious modern Ireland – an Ireland that was projecting itself onto an international stage. With this new venture, artists could explore new contexts, experiment with materiality and time, and be emotionally responsive to our sites of history. Under the award, Dorothy Cross’s Ghost Ship proposed a tribute to 12 engineless, anchored, skeleton staffed ships which floated on the Irish sea. The ships marked sites of danger and acted as guides to all vessels which entered our waters and were later replaced by automated marine buoys. Dorothy’s winning idea was met with much anticipation in the media. The coverage highlighted challenges, curiosity, excitement and the individuals involved in its creation; the work performed its site, monumentalised the disused ship and excited audiences everywhere. From the acquisition of the ship from the Commissioner of Irish Lights, the valuable manpower of the sea scouts, the unwavering support of the commissioners and the curator, Sarah Glennie, and the creation of the new phosphorescent paint and timed UV light system (which would see the work arrest in daylight and shimmer in darkness), Ghost Ship was in-situ for three weeks. It surpassed its original timeframe through

Dorothy Cross, Ghost Ship, 1999, DVD, 12 min. 17 sec. loop; courtesy of the artist and Kerlin Gallery