7 minute read

Scale and Ambition. Jane Fogarty and Isabel Nolan discuss some of

Alan Magee ‘Among the dregs of daily toil’ The LAB Gallery, Dublin 7 February – 16 March 2020

Lauren Gault ‘C I T H R A’ Gasworks, London 23 January – 22 March 2020

ALAN MAGEE’S EXHIBITION, ‘Among the dregs of daily toil’, could have been perfectly timed to capture the zeitgeist of the recent general election. In a series of highly conceptual works, Magee explores understandings of labour and the handmade, broadly speaking, through the prism of critical theory. Magee creates an allegory for how human intellect and self-identity is tied into the material self – the sustenance of the body and life. Marx understood this as ‘species essence’, from which individuals have been alienated by modern capitalism’s demand for the mass production of useless and meaningless things. Magee presents seven works, as listed on the gallery leaflet – a mix of kinetic and object sculpture, video and printed imagery in a taut and bare display that benefits from an abundance of white space. Magee finds different ways to illustrate the mind-body relationship by creating a visual study of himself making digital and ceramic objects. From one piece to another, ideas overlap to create satisfying linkages.

The first piece encountered is the most poetic work. Subconscious Labour, Conscious Growth is placed in The LAB’s vestibule space on a slender square plinth with a sleek glass case. Inside the case a set of seven iron finger-nail castings are casually arranged, as though they are artefacts in a vitrine, a bit like some of the Ór displays at the National Museum of Ireland. These items, however, are pitiful, unsightly and grubby with rust and white corrosion. They carry both the contemporary burden and the historical loss of human endeavour to capitalism.

In the main gallery, a large banner hangs over a bar and drops down on two sides, confronting the visitor immediately. Machine Flesh #1 & #8 depicts the veined surface of unidentifiable internal organs through which fingers can be seen pushing and pressing down. To the right of the banners another work, Immaterial Organ Series, comprises 12 slick hexagonal grey plinths laid out in a molecule diagram imitating a trendy tech expo. On each plinth, Magee has placed one crude and gaudy handmade ceramic sculpture of an organ – a liver, kidney, bladder and so on. These vulgar lumps of bright pink glossy matter are, like the fingernail iron castings, at odds with the highly conceptual and technological nature of the other works on show. In the next space a video projection shows Magee forming these ceramic organs while wearing a virtual reality headset with a back projection showing his virtual environment – simply a 3D image of the organ he is trying to blindly approximate in clay. The banner, organs and video triggers an abstract feeling of visceral discomfort – a kind of involuntary gut wrenching that is utterly let down by the elementary appearance of the ceramic objects. Both the iron castings and these three linking works amplify the feeling of disconnection between body and mind.

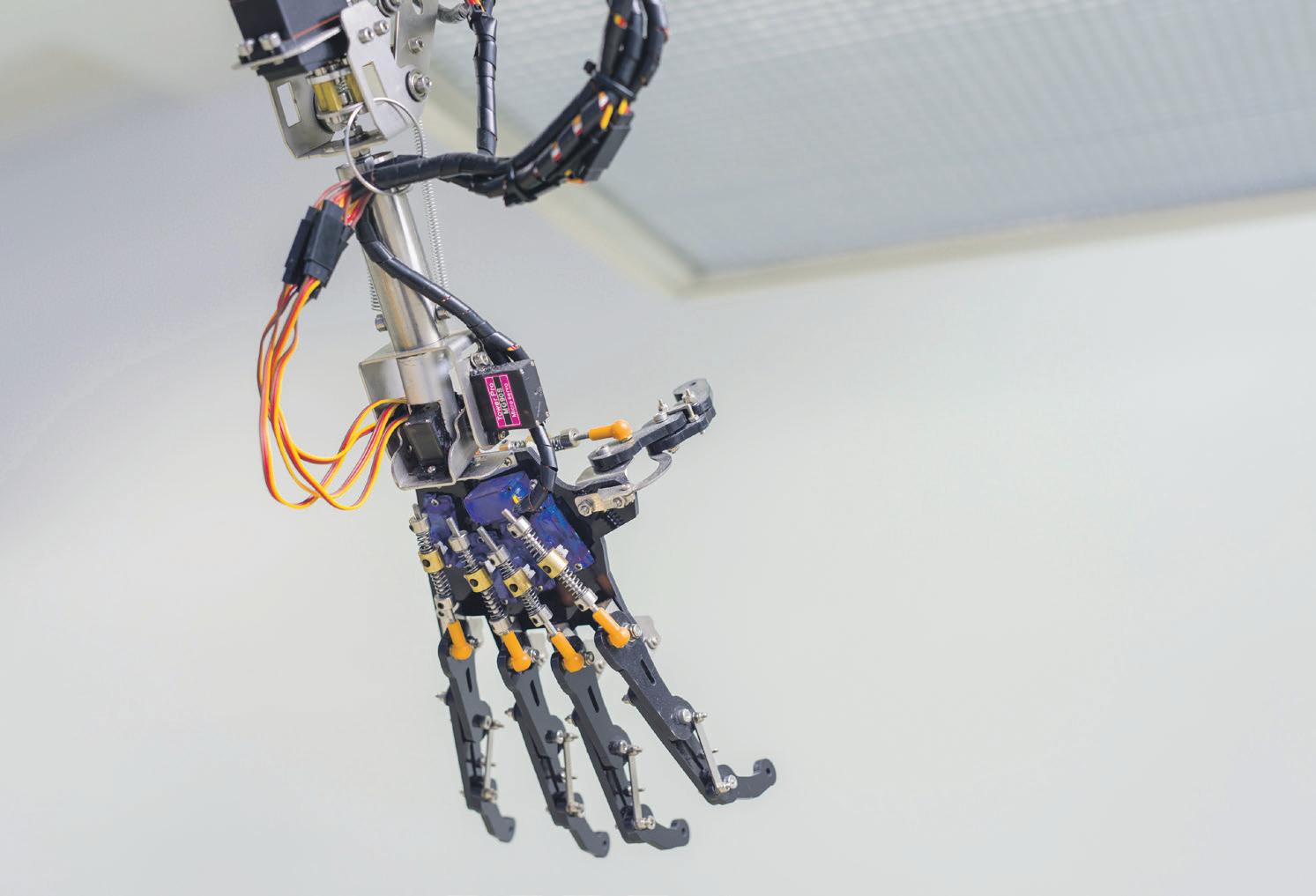

Hanging on a metal scaffold nearby, a robotic arm flexes and moves from time to time in Celestial Machines (a). Beside it, in Celestial Machines (b), an eleven-minute video documents Magee’s complex construction of the robot from tiny component parts. This is the most satisfying work in the exhibition and makes for compulsive viewing. The arm emits murmuring clicks and wooshes with each flex, moving gracefully in a dancing ballet. There is closure in this work, as the product of the intricate and skilled workmanship in the video is evidenced by the robot prototype elegantly demonstrating its range of movement. The two works reinforce the fundamental affirmation of making useful things in an uncomplicated and humble manner.

The final work in the show, 1 and 0 paper balls, brings humour to Magee’s thesis. A tiny recessed shelf holds two tiny scrunched up paper balls, one of which has been 3D printed in sandstone. Twelve feet above, till roll spews endlessly from an invisible slot, upon which the code required to process the 3D printing is thermally printed. The scrunched-up paper is described in the gallery list as Magee’s ‘redundancy letter from lecturing post’. While it punctuates the exhibition with a very definitive full stop, there is also a sense that Magee has barely scraped the surface of this humongous human theme. The recent general election, helped in some way by climate action, marks a growing consciousness of how the capitalist economy has impacted the human condition, wellbeing and the environment. Magee pitches an insightful and affecting series of works that is reflective of this awakening. Carissa Farrell is a writer and curator based in Dublin.

Lauren Gault, C I T H R A, 2020, installation view, commissioned by Gasworks; photograph by Andy Keate, courtesy of the artist

‘C I T H R A’ IS AN exhibition of new work by Belfast-born and Glasgow-based artist, Lauren Gault. This is Gault’s first solo exhibition in London, showcasing installations that both revisits and further exploits the artist’s key approaches and concerns, which revolve around the use of unorthodox techniques and a wide variety of materials. The show emerges out of research undertaken by Gault during a residency at Gasworks in spring 2019. A key starting point came from a publication held in the British Library, a long forgotten science-fiction novel, The Men of Mars (1907), by Martha Craig, a relative of Gault’s. Craig was an explorer who developed a series of theories, including explanations for the origin of the universe, material travel and dual consciousness. From this book, loose conceptual overlaps feed into each other and inform subjects addressed in the exhibition.

The gallery text primarily frames this conceptual riffing around the artist’s upbringing in rural Ireland and the mythological figure of Mithras. An early rival to Christianity, this Roman religion produced iconography which centred on bullslaying, with repeated images of dogs, snakes and ravens. What connects these disparate ideas is a shared vocabulary relating to the history of agriculture, which is present throughout the show, and within this, Gault finds stories about wildness and domestication. It seems almost as if the two exhibition spaces are divided between these polar opposites. The first space addresses ideas of wildness, through sculptures of wild animals and burning Roman arches; while the second describes the rise of the industrial, through depictions of extinct species and the usage of mass-production techniques.

In the first room, there are three distinct sculptures which share a pale palette of pure and off-whites, light greys and a rare poke of brown. Collectively, the sculptures act as a stage for particular protagonists: arched and snarling eyeless dogs with sharp teeth, stretching upon their hind legs against the taut nylon; a leisurely disembodied hand resting on a platform above; and hand-sized bulls sinking into the base of a long, narrow floor-based sculpture. In the second, mostly dark and empty space, three transparent water tanks are cut into the ceiling. Light shines through the liquid within each of the tanks, casting a gentle sparkle onto the wall behind. The emptiness in the space allows the light to bounce and glow, in contrast to the synthetic quality of the water tanks. One easy-to-miss hoof-print emerges from the wall, hauntingly depicting an auroch – an extinct species of wild cattle – serving as a reminder of what progress can leave behind.

Related but not exactly the same, there’s a logic between the adjacent poetic resonances of history, biography and mythology which seems to guide the construction of the works. It is less useful to think of these sculptures as singular objects; rather they seem to act as a sequence of materials, relationships and actions which hold a symbolic weight of their own. I think that’s why the charm of the works is found more so in particular sculptural flourishes, rather than the whole piece itself: in the taut nylon, stretched over solid wooden boards, which gives way to long sleek slender curves of fabric; in the offwhite dust, set against the bright titanium surfaces of the sculptures and walls, which act as framing devices; and in a sagging ball of glass, frozen like a water droplet.

While there are many narratives and formal strategies to engage with in Gault’s work, it’s something beyond this which feels significant too. Her process is shaped by the rituals which she riffs upon, while history – that of agriculture, of Ireland and her own personal biography – becomes a raw material, creating rich points of departure for wider social and ecological concerns. More and more contemporary artists are revisiting unknown thinkers with alternative theories as subjects for their work, with such inquiries often focused on redeeming counter-histories and reflecting on other existential possibilities. Gault creates sculpturally-led works which hint at something almost occultic, the off-terrain spirituality of rituals centered on a tension between wildness and domestication, harnessing the otherworldly energy of nature and myths. Chris Hayes is an Irish writer and editor based in London.