4 minute read

Irish Sculpture of the 1980s

Liam Gillick, In order to be able to draw a limit to thought, 2001, wall mural, Balfour Avenue, Belfast; photograph by Ros (geograph.co.uk), distributed under Creative Commons License BY-SA

a film and work exhibited at IMMA, a beautiful print edition, and was memorialised on a national stamp. For me, it highlighted the number of supports needed to truly realise the vision of the artist, while setting a new standard for what artists working within this realm might come to expect. It is these invisibilities that will always keep Ghost Ship firmly in my memory. Caroline Cowley

In Dublin (1999) Tina O’Connell

I vividly recall experiencing Tina O’Connell’s In Dublin, encountering it as both object and event amongst an excited crowd of onlookers packed into a pub in the Liberties. I remember the intense concentration of energy in the building and a heightened sense of shared time, uncommon in my experience of sculpture. Part of my own excitement stemmed from the opportunity to go upstairs, moving from the ‘public house’ into a more domestic realm. I made many trips up and down those stairs, trying to see the whole of the sculpture – an impossibility. From above, a briefly perfect sphere of bitumen sat waiting, apparently inert. But something was always happening below, as the viscosity and weight of this thing was pulling it relentlessly down through the hole and onto the floor. I remember this process as slow, slow, slow and then suddenly fast, so fast I think I actually missed the moment when the black stuff touched the ground.

In Dublin was an ‘Off Site’ commission by Project Arts Centre, one of many ambitious temporary works programmed by Fiach MacConghail and curated by Valerie Connor during the construction of Project’s new gallery building on East Essex Street. An Irish artist based in London, Tina O’Connell made the sculpture while on residency at IMMA, with support from multiple organisations including Irish Tar. The object itself, later remade for the exhibition ‘0044’ at PS1 in New York, consisted of a bitumen sphere, assembled from two casts, over a metre in diameter and weighing a tonne. It was installed in The Barley Mow, a disused pub on Francis Street, an area then (and now) subject to the forces of gentrification. The interior was then entirely intact, complete with a wooden bar and dark leatherette seating. Twenty years on, the signage is still visible, but the building is little more than a shell, its windows either missing or boarded up. Standing in front of The Barley Mow, I try to imagine the exact centre of the dark sphere that once descended from ceiling to floor, using this structure as the support for a massive, and irreversible, hourglass. Maeve Connolly

2000s

Shane Cullen, The Agreement, 2002, photograph by Ian Charlesworth, courtesy of the artist and Golden Thread Gallery

Detail from The Paradise book, 2002; photograph courtesy of John Hutchinson

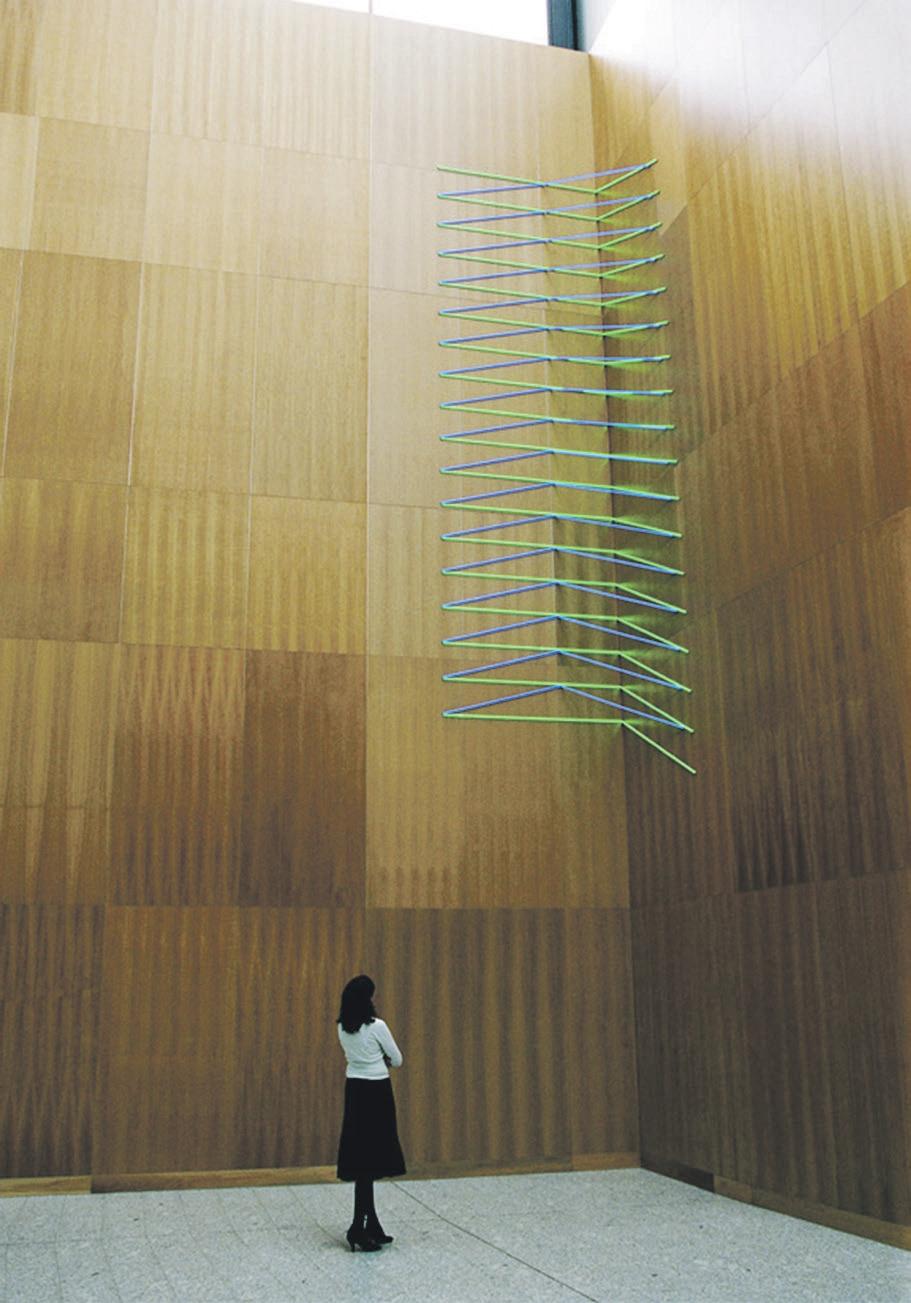

In order to be able to draw a limit to thought (2001) Liam Gillick

THIS WALL TEXT, located on a gable end on Balfour Avenue in south Belfast, was commissioned as part of The International Language, an event organised and curated by Grassy Knoll Productions (Phil Collins, Annie Fletcher and Eoghan McTigue) that took place across Belfast between 28 April and 12 May 2001. The International Language also included performances, interventions and public sculptures by local and international artists Heather Allen, Phil Collins, Jeremy Deller, Seamus Harahan, Torsten Lauschmann, Eoghan McTigue, Philip Napier, Asier Pérez González, Susan Philipsz, Stuart Watson, and Sislej Xhafa. The question in Liam Gillick’s wall text, “How can quantum gravity help explain the origin of the universe?” was one of 10 questions about theoretical physics that the artist publicly posed in Belfast using wall texts, cake decorations, taxi business cards, beer mats, a conference/lecture and a website. With the exception of this wall-based work, little exists publicly today (bar a review by Miriam de Búrca in CIRCA, Autumn 2001, which is archived online) to document The International Language and the public art produced as part of it, emphasising the importance of defining and canonising permanent as well as intangible and temporary public art works. In order to be able to draw a limit to thought does not commemorate, celebrate or advocate the views of any particular community, as many of the traditional Belfast murals it is listed alongside in guides do; nor does it attempt to heal, renew or restore, like other more recently commissioned public art in Belfast. Instead, positioned at the end of a terraced street overlooking the River Lagan, it provides a striking, thought-provoking moment of questioning that continues to interrupt the affirmative fluency of the daily commute and the prescribed touristic ‘post-conflict’ city experience. Alissa Kleist

The Agreement (2002) Shane Cullen

SOME SCHOLARS OF the 1998 Good Friday Agreement hail it as a model of ‘constructive ambiguity’ – an artfully uncertain structure, open-ended enough to invite contrasting interpretations of its contents. Evasive language allowed difficult decisions to be postponed. Definitive plans were not set in stone. For other commentators, any emphasis on the perceived ambiguity of this momentous, multi-party accord is misleading. The Good Friday Agreement is, they argue, a work of skillful specificity: an intricately wrought textual construct that delineates precise and distinct political proposals, using sensitive, subtle language to articulate communal aspirations and shape new political forms.

Shane Cullen’s sculpture The Agreement (2002) – a land