18 minute read

Irish Sculpture of the 1990s

mark artistic response to the official resolution of conflict in the north of Ireland, originally commissioned by London’s Beaconsfield gallery – can be read in each of these contrasting ways. It is a work of monumental scale and style: the entire 11,500-word text of the negotiated settlement mechanically inscribed onto fifty-five four-foot-wide polyurethane panels. Massive, and imposing, it gives the appearance of solidity and permanence, resembling an elaborate public memorial, intricately detailed with unchanging, authoritative declarations. As such, it appears to mark the solemnity of an historical milestone with ambition, grandeur and certainty. And yet, this is an ‘uncertain’ sculpture too: made from relatively lightweight material, it is mobile and potentially impermanent. It is not set in stone. Rather than a grounding, durable form, it is a precarious maquette, a promise of a monument-to-come. Cullen’s sculpture, variously staged in Belfast, Derry, Dublin, London and Portadown during the early, anxious, post-Troubles years, is an ambiguous construct: a shifting, unsettled, ‘open’ form, that also, at an important point in Ireland’s recent history, pointed towards the hoped-for potential of closure. Declan Long

More Than Anything (2004) Maud Cotter

A MODULAR STRUCTURE of variable dimensions made from 1.5mm birch plywood, More Than Anything embodies many of the themes that continue to preoccupy Cork-based sculptor, Maud Cotter. Cotter has worked consistently with materials that allow her to provoke awareness of such interfaces as mind and matter, interior and exterior, individual and collective, macro and micro. The work was installed in different guises in the Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast (2004), Crawford Art Gallery, Cork (2005), VISUAL, Carlow (2009) and, later, The Lab, San Francisco (2011). Where one iteration appeared to overwhelm the existing infrastructure and evoke architectonic form, another slowly encroached and divided spaces. The basic units from which each is made are lightweight, yet strong, and mirror the cellular makeup of the body. Also reminiscent of spinal structures, they convey resilience rather than vulnerability. The crosses formed where planar elements connect allow light and air to penetrate, while the repetition of this motif and its scaled-up explorations of horizontality and verticality invite comparison to the Modernist grid. At the art-craft juncture, the work’s systematic construction recalls the woven textile, an ancient technology bound up with cohesion and unity. However, a lack of rigid regularity breaks rank with this analogy and suggests propagation and growth. Susan Campbell

Zip (2004) Corban Walker

CORBAN WALKER WAS commissioned by Aisling Prior for Breaking Ground – the Ballymun Regeneration Per Cent for Art programme – to create a site-specific work for the interior atrium of the Civic Centre in Ballymun. Responding to the vast proportions of the space, Walker created a sculptural piece for one of the corners, comprising interlacing green and blue LED lights. With meticulous geometric precision, Zip appears to weave together the two perpendicular walls. This work attests to the philosophies of architecture and scale, recurrent in Walker’s wider practice, which often involves the creation of free-standing geometric configurations or minimalist glass stacks. Installed high on the wall, viewers must experience Zip from floor level, while looking upward. This spectator position highlights the ways in which Walker, the son of an architect, seeks to consider the pedestrian experience within the built environment. Joanne Laws

A Pampootie

FOR MANY REASONS I found it impossible to choose a favourite piece of contemporary Irish sculpture, but an unexpected alternative quickly came to mind – a pampootie from the Aran Islands. When I began to wonder why, the reasons became clear. First, I recalled that one had been included in ‘A Dream of Discipline’ (2006), a show by Kathy Prendergast, Dorothy Cross, and William McKeown at the Douglas Hyde

Napier & Hogg, The Soft Estate, 2006; photograph by Peter Richards, courtesy of the artists and Golden Thread Gallery

Gallery, and that an image of the same shoe had appeared in an earlier gallery publication called The Paradise (2002). The pampootie had accrued some sculptural or ‘artistic’ qualities by osmosis.

More significantly though, I’ve always found the shape of pointed-toe pampooties graceful and beautiful, almost otherworldly, as though they were worn by fairy folk. Their real social origins, of course, were far more down-to-earth. Made from single pieces of untreated hide with the hair left on, held together by leather laces or twine, pampooties were used as everyday footwear by Aran fishermen, who had to keep them moist in order to retain their suppleness. They were not expected to last very long.

It is said that J.S. Synge insisted on the use of real pampooties in his productions of his Aran Islands play, Riders to the Sea, because their pre-modern ‘authenticity’ was crucial to one of its themes, the tension between tradition and contemporary life. This natural ‘authenticity’, however romanticised, as well as their sense of functional agility, helps to account for much of my liking for them. At the same time, however, they are inextricably linked in my mind with artists like Kathy Prendergast, Dorothy Cross, and Aleana Egan, because their work frequently references, or is made from, natural materials and vernacular objects. I find it endlessly fascinating to see how the meanings of ideas and things keep shifting and developing according to their contexts and connections. John Hutchinson

The Soft Estate (2006) Napier & Hogg (Philip Napier & Mike Hogg)

THE SOFT ESTATE comprised a constellation of various and changeable sculptural units, orbiting around a series of dining tables. The tables functioned as specially constructed negotiating tables, whilst the accompanying units explored forms of measure and a revised language of assigned common attributes. Initially the first of the tables appeared as a sturdy extending dining table. The table, beautifully manufactured, by Gilbert Logan and Sons, was actually a facsimile of a table originally destined for the ill-fated Titanic that now resides on public display in the Custom House, Belfast. Strategically presented in a de-familiarised state, and fully lengthened with its engineered mechanism exposed by the deliberate omission of its central panels, the work invited considered reflection and discussion.

The second table existed in a bastardised state, prone to fail under its own weight, as a precarious assemblage. It stood vastly over-stretched and provisionally shored up to prevent

Tim Shaw, Parliament, 2006, black polythene, wire and straw; photograph by and courtesy of the artist

Eva Rothschild, The Rock and the Arch, 2007, polystyrene, jesmonite, ceramic tiles, grout, painted steel, 311 × 447 × 144 cm; photograph by Andy Keate, courtesy of Courtesy Modern Art London, © artist

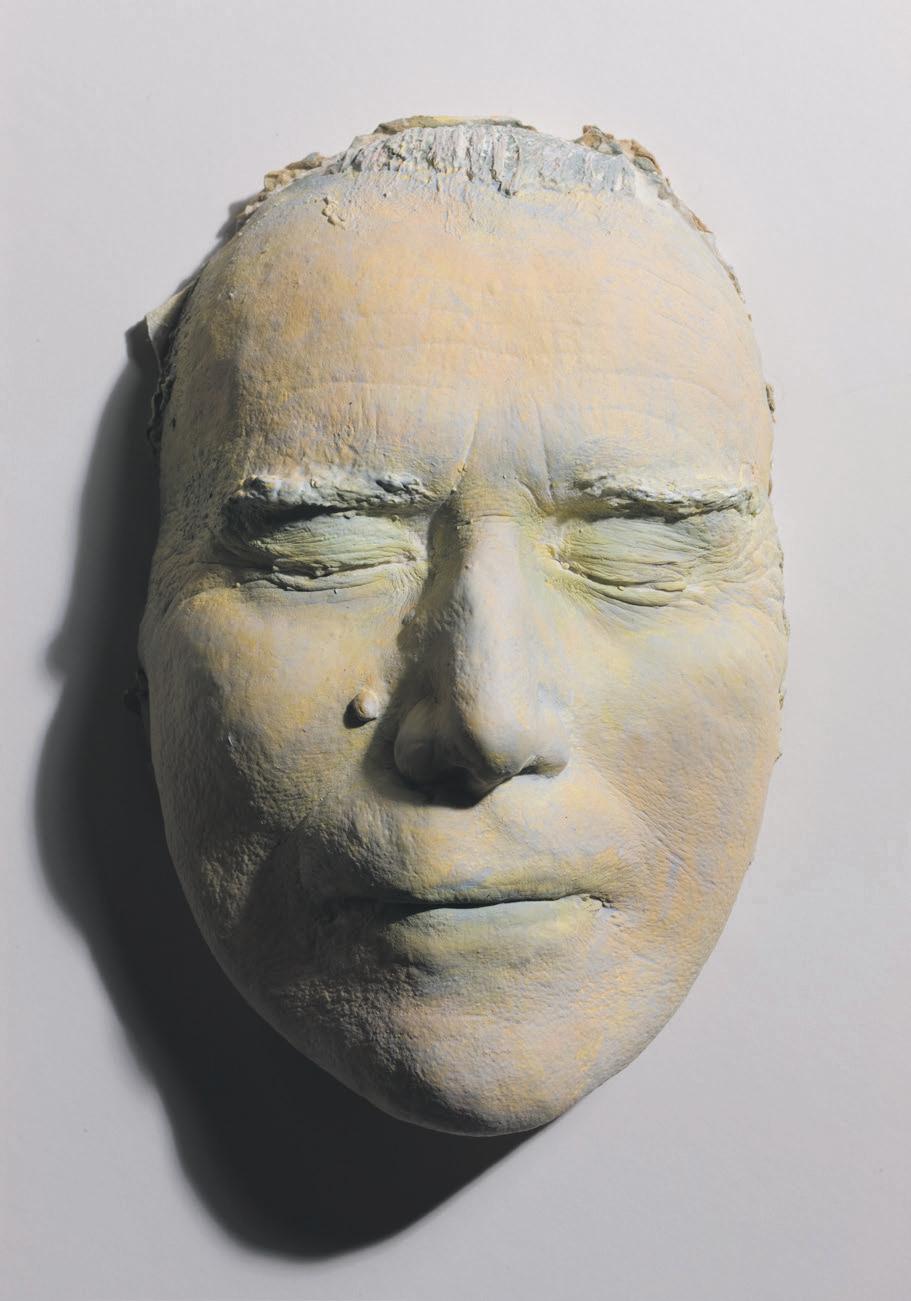

Brian O’Doherty, Charles Simonds, Patrick Ireland, The Burial of Patrick Ireland, Death Mask, 2008, plaster cast and paint, collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, donation, 2008

its inevitable collapse. Again, the table made a feature of its negative space, a temporary gap to be filled, and provided a counterpoint to the first table’s assured historical posturing. Rather, it brought to the fore a sense of the collective amnesia, necessary suspension of disbelief, and the tangible fragility on which the optimism for the then relatively new North of Ireland had been founded.

The Soft Estate was first shown at the Golden Thread Gallery in 2006, before being reconfigured and re-presented at The Temple Bar Gallery, Dublin, and as part of the University of Ulster’s Interface project, ‘I Confess’, in Belfast. In later configurations of the project, the initial two tables were accompanied and then superseded by the introduction of a pneumatic dining table – a table that quite literally bucked the potential of any negotiated consensus being formed. The tables, the measuring tools and the diagrammatic displays functioned simultaneously as parts of a whole and as units with something in common, associated in theory that formed temporary groups “within which various relationships can be found.” Sure enough, as if foretold through this project, the region’s newly formed political structure collapsed through its quest for consensus. Peter Richards Parliament (2006) Tim Shaw PARLIAMENT MARKED A pivotal moment in the work of Belfast-born sculptor Tim Shaw. Prior to making this work, Shaw had been consumed for four years by a large commission for the Eden Project in Cornwall that contained over 30 life-size elements – copper-beaten figures and vines depicting a Dionysian sacrificial rite that celebrated untamed nature. After completing this monumental work, Shaw retreated from the studio and took part in the artist residency programme at Cill Rialaig in County Kerry. After two uninspiring days of acclimatising to the cold, bleak landscape, he began to notice flickering shapes in the trees. At first glance, they appeared to be the dark silhouettes of crows and rooks but revealed themselves to be shredded pieces of agricultural polythene, snagged in the branches.

Inspired by the illusion, Shaw set out to make 25 life-size rooks from materials gathered from the surrounding area – polythene, straw and wire. The behaviour of the birds invited the comparison with those in positions of power and the resulting installation saw Shaw augment the sculpture with a soundtrack of corvid voices, layered with the chattering of debating parliamentarians. A clear departure from his wellknown work in metal, this work manifested a desire to make political commentary within his work. Subsequent works Man on Fire, Tank on Fire and Casting a Dark Democracy all draw directly on elements that can be traced back to the Cill Raillaig work – the heavy use of black polythene, augmenting sculpture with soundscapes and using the work to make a political statement. Parliament has been exhibited several times since its creation, most notably at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 2019 and most recently with Anima Mundi at the empty and derelict Vicarage Flats in St Ives, Cornwall. Rob Hilken Hotel Ballymun (2007) Seamus Nolan ON A SUNNY day in spring, the views from the Thomas Clarke Tower were fantastic; priceless, in real estate terms, and yet before long everything would come tumbling down. The demolition of Ballymun’s iconic towers may seem like a portent for other, more widespread collapses, but on that bright afternoon the canopy of blue stretched faultlessly to the horizon. Fifteen floors below, familiar streets looked beautiful too, abstract and logical, in a way that never seemed true on the ground. Though I grew up on the fringes of Ballymun, it remained oddly obscure, a no-go area ruled by kids much tougher than me. Ballymun was no one’s idea of a destination and yet, here it was, an obsolete tower block reimagined as a boutique hotel.

In the first decade of the new millennium ‘Breaking Ground’, led by curator and artistic director Aisling Prior, commissioned an extraordinary array of artists’ projects in the Ballymun area. Most of these engaged directly with local communities and collectively they helped to redefine the idea of public art in Ireland. In tandem with a regeneration programme that, ironically perhaps, would see the destruction of the towers, Seamus Nolan’s project was an audacious last stand. Declan McGonagle called Breaking Ground “A museum without walls”, and as sunlight flooded into the top floor of the tower housing Hotel Ballymun, his metaphor felt literally true. In the nine, short-stay bedrooms, tasteful arrangements of twigs and fresh flowers civilised the bare walls. Different in every room, abandoned furniture and household bric-a-brac had been refashioned into new forms of modernist chic. A side-table looked like a Rodchenko sculpture. Old chairs were spliced and reformatted into mildly indecent couplings. A cool and clean aesthetic with a twist – it was as though the working class had taken out a subscription to Elle Décor.

Dublin airport was just up the road and as a plane flew in low between the tower and the sun, its shadow moved across the concrete interior. Perhaps I’m imagining this. Or I might be confusing it with a trip to Marseille, where for two days my wife and I lived in the Unité d’Habitation, otherwise known as Cité Radieuse – the radiant city. We were less high up there, the seventh floor I think, but the sense of elevation was even greater, because we were inside Le Corbusier’s masterpiece. Being in Marseille made my appreciation of Nolan’s project greater too. I felt the link between the two visions in my bones.

In one corner room, a puffed-up double bed was supported by a myriad of spindly chair legs. How deliciously incongruous it looked, as though Kafka’s Gregor Samsa – waking from his beetle dream – had transformed into the bed itself. There was a rubble room too, I seem to remember, a small room full of the stuff the whole building would soon become. In the music room a stack of old cassette tapes had been left behind by previous tenants and were playable on a dodgy-looking ghetto blaster. Randy Crawford’s Rainy Night in Georgia leaked out between the sunbeams. I’m imagining that too. I don’t remember what was on the cassettes. I wish I could. I was touched by the idea of it though; the past lives recycling on those dusty tapes, their wobbly hiss like the oxygen of the future slowly leaking away.

Though fully booked throughout its four weeks, Nolan’s project was built to fail. It was, in a sense, a hymn to failure; an elegant pass at what might have been. More than 70 people had collaborated to organise and run the hotel, its undoubted poignancy off-set by the sheer scale of its ambition. While larger questions persisted about the long-term fate of Ballymun and its communities, on that bright afternoon at least, everything was illuminated. John Graham The Rock and the Arch (2007) Eva Rothschild FRAGILITY AND SOLIDITY are playfully inverted in Rothschild’s two-part sculpture, in which neither element looks especially stable. An example of her inventive use of materials, the ‘rock’ has been hewn from polystyrene and covered in tiles to create an illusion of heaviness. This is an effect the artist, who lives and works in London, later exploited in Do-Nut (2009). Also difficult to discern, the frail-looking arch is constructed from durable steel. Both components are faceted, which counters their differences to establish some commonality. The steel ‘arch’ hints at human form, its bifurcations alluding to limbs – as made explicit in the similarly structured Someone and Someone (2012). Reading from left to right the ‘figure’ overtops onto the rock, but in the reverse direction appears to arise from it. Where a straight line establishes a direct connection, the arch instigates a more dynamic link. Its apparent instability and the rock’s irregular profile channel Baroque tendencies, evidence of a critical practice that also revisits the restrained ethos of Classicism and decisive language of Constructivism. An artwork from a sculptor as willing to engage cosmic machinations as the prevailing political landscape, it invites viewer interactions that unshackle experience from expectations of certainty. Susan Campbell Burial Mask (2008) Brian O’Doherty, Charles Simonds, Patrick Ireland Give a man a mask and he’ll tell you the truth – Oscar Wilde

ON 20 MAY 2008, the artist Patrick Ireland was buried in the grounds of the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA). He was thirty-six years old and had been a pioneer of installation art in the form of a series of Rope Drawings since 1973. He was buried wearing a mask of the face of the artist Brian O’Doherty, made by Charles Simonds. O’Doherty’s multifaceted career put identity at its core for sixty years, using several fictitious personae and anticipating the concerns of much later art. Patrick Ireland’s ‘life’ began almost fifty years ago, following Bloody Sunday in Derry on 30 January 1972, when 13 civil rights marchers were killed by the British Army. In a unique gesture of peaceful protest, O’Doherty changed his artist name to Patrick Ireland in 1972, the first performance art in Ireland. This durational performance was to last for thirty-six years until the Troubles ended in the Good Friday Peace Agreement in 1998 and the Burial of Patrick Ireland in 2008. Taking a historical event rooted in conflicts of identity, the Name Change gesture only became complete when the artist’s name no longer represented that conflict, as efforts to transform fixed notions of identity became established. It is to be hoped that the ‘death’ of Patrick Ireland and what the name stood for will remain a memory, a part of art history. Brenda Moore-McCann

Suzanne Walking in Leather Skirt (2008) Julian Opie

WHEN INVITED TO nominate a piece of sculpture, I immediately thought of a public work, and Julian Opie’s Suzanne Walking in Leather Skirt came to mind. On reflection, of course, there are works by Irish born artists that come to mind also. However, as this work has been on public exhibition outside The Hugh Lane Gallery on Parnell Square for over ten years now it is surely part of the soul of the city. It was acquired after the exhibition ‘Julian Opie: Walking on O’Connell Street’ (20 January – 25 October 2008) curated by Barbara Dawson, Director of the Hugh Lane. That exhibition down the centre path of O’Connell Street made a marvellous impact, featuring five animated walking figures, some relaxed and others appearing more stressed. It was a perfect example of how works of art can engage the public; I remember being struck by how I myself was stopped in my tracks and observing so many others being affected and even mesmerised in the same way. Up close and from a distance, those works lit up the street. Suzanne Walking in Leather Skirt is a portrait in simple black outline with light, reflecting the contemporary age of light and movement. It could be a shadow or refection. Like all simple images, it is complex too. It is the movement and energy that I get from it that affects me each time I pass it. It can have the effect of slowing the pace and be quite hypnotic. It has a timeless quality. Oliver Dowling

Voices (2009) Cecily Brennan

VOICES COMPRISES OF five unique life stories from people living in Ballymun, commissioned by Breaking Ground when Ballymun was in the middle of its regeneration process. Working with five people from diverse backgrounds, these individual’s stories covered alcoholism, sexual and physical abuse, homelessness and self-harm, but perhaps most importantly, reflected each individual’s capacity to love and survive hardship. Each person was represented by one photograph, a still life of something suggested in each story, along with an audio piece of their story. The work launched in Ballymun Civic Centre in August 2009, before being permanently located in Poppintree Community Centre. While the work at first glance appears quite minimal and simple, the interviews draw the viewer deep into each participant’s life. Disarmingly honest and open, some of these stories were harrowing, reinforcing a sense that we can never know what is truly going on in people’s lives. The work in its simplicity also disguised the monumental effort and devotion of Cecily herself, who worked tirelessly and selflessly with the participants over two years, becoming deeply involved in their lives. If Breaking Ground’s mission was to present public art projects in diverse and alternative ways, Cecily’s work was a resilient triumph, celebrating the voices of the voiceless, and the stories which are uncomfortable to hear. Paul McAree

Cecily Brennan, Voices, 2009, commissioned by Breaking Ground; image courtesy of the artist

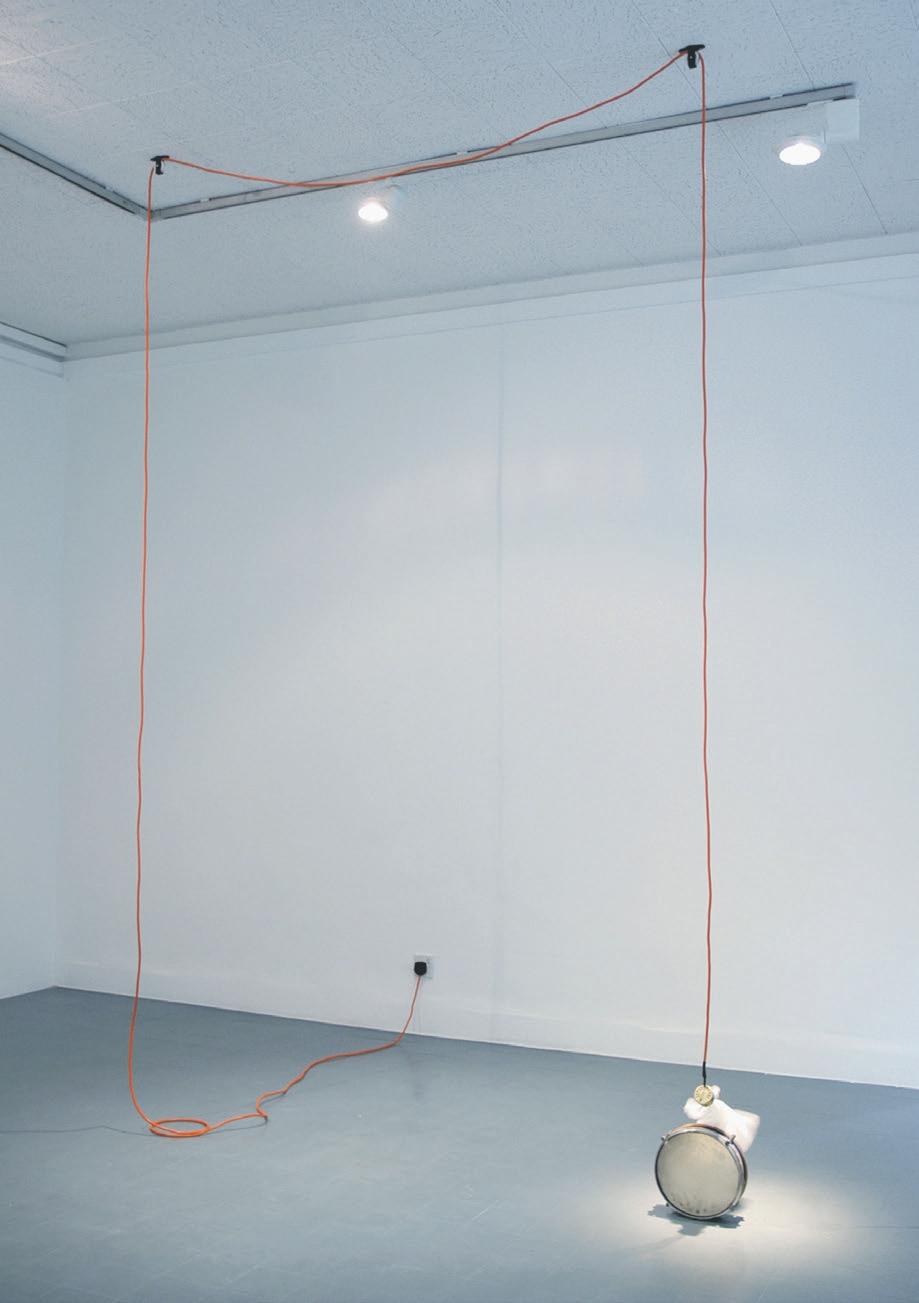

Drum Roll (2009) David Beattie

DAVID BEATTIE’S KINETIC sculpture, Drum Roll, featured in the exhibition, ‘All humans Do’, presented at Whitebox (New York) and The Model (Sligo) in 2012, supported by Culture Ireland. Drum Roll is innovative in terms of its materiality, interdisciplinarity and public engagement strategies. A plastic bag is attached to a drum, which rolls forwards and backwards. We hear the rustling sound of plastic being squashed, twisted and expanding again. A machine facilitates this activity, driven by a motor linked by a long wire to the power socket. The piece gives new meaning to the 18th-century Zen kōan about the ‘sound of one hand clapping’. Form, they say, is function; but maybe, function, in the case of Beattie, is form. Beattie has continuously worked with materials that transcend their original function, making connections with sculptural forms in unique but quotidian ways. Beattie continues to be successful in major public art commissions and has brought his forensic interest in materiality to these new works. Aoife Tunney

2010s

Misneach (2010) John Byrne

CURRENTLY LOCATED ON the grounds of Trinity Comprehensive School in Ballymun, Misneach (Courage) is a public sculpture created by John Byrne in 2010, curated by Aisling Prior and commissioned as part of the Ballymun Regeneration, the largest urban regeneration project ever undertaken in Ireland. Subverting the military tradition of equestrian sculpture, Misneach depicts a local Ballymun teenager (the then seventeen-year-old Toni Marie Shields) astride a horse, modelled from a former colonial monument, the Viscount Field-Marshal Gough Memorial, originally sited in Phoenix Park until it was destroyed by Irish Republicans in 1957.

Cast in bronze at 1.5 times life-size and mounted on a monumental granite plinth, Misneach’s significance lies not only in the triumphant artistic accomplishment of the work itself, but in what the controversy it provoked at the time revealed. Its proposed placement in the town centre of Ballymun, spurred responses spanning from the sublime and the sardonic-fuelled, to outright hysteria by certain media moguls. At times this bordered tantalisingly close to public discourse

David Beattie, Drum roll, 2009, drum, motor, plastic bag, electrical cable, dimensions variable; courtesy of the artist and Berlin Opticians Gallery

John Byrne, Misneach, 2010, bronze on granite; photograph by Rory McAllorum, courtesy of the artist