I WAS NOT A FEMINIST

Various Authors

I Was Not a Feminist

First edition, 2018

Project Coordination Verónica del Pozo Saavedra

General Edition Patricia Cocq Muñoz

Art direction Karina Cocq Muñoz

Design and layout Juan Rosales Garrido

Cover illustration Sol Undurraga

Printed in Fugar Impresores

I Was Not a Feminist

© Cocorocoq Ediciones Santiago de Chile www.cocorocoq.com ISBN 978-956-9806-0

Contents

Introduction

Prologue

Story by María Gracia Sandoval Iturralde

Story by Laura Lacayo Espinoza

Story by María Francisca Stuardo Vidal

Story by Laura Sofía Martínez Quijano

Story by Catalina Bosch Carcuro

Story by Lesly Mirel Ruiz Brindis

Story by Ana María Fernández Ureta

Story by Verónica del Pozo Saavedra

Story by Laura Sánchez Gil

Story by Eugenia Guareschi

Story by Grettel Salazar Chacón

Acknowledgement

Dedicated to Amanda, Teba and all the girls who are learning to be women, to whom we hope to deliver a more fair and free world.

Introduction

Nobody is born as a woman, pointed out Simone de Beauvoir, but one becomes one. Through the process of socialization, we are taught our position, roles, characteristics, and even the emotions we can feel based on our biological sex. It is what feminism has called gender.

But it is also true that no one is born a feminist, as Marta Lamas Encabo has pointed out, among many others. Feminism is a progressive awareness of the position and subordinate condition in which women find ourselves in a patriarchal system, present both at home and in public life. This awareness is inspired by thousands of experiences, reflections, and books. But above all, at least in my case, inspired by other women. Friends, colleagues, acquaintances, teachers, references.

For many women who are adults today, that degree of awareness has been a long time coming. Some, on the other hand, have been raised in a critical vision of the patriarchy since their birth, but even so, they have been required to work on different aspects in which their upbringing conflicts with the hegemonic culture.

Everything depends on our biographies, on our personal life experience, which gives us subjectivity to face reality. This is how we can verify it when reading the history of the first women who wrote against patriarchal domination and who became reference points for all of us. All of them experienced in some way the sensation of living oppressed, and from that personal experience, with great courage, they questioned the patriarchy and the construction of gender roles. Because, as Marxism maintains, it is the material conditions of existence that determine the awareness we have of reality.

"I was not a Feminist" is not an academic book, it is an intimate, anecdotal book. It was born in the midst of the vortex that was the creation of the first Association of Feminist Lawyers of Chile (ABOFEM), in which I participated as one of its directors together with a group of admirable women, and from the enormous response that the Association has had by political and social actors. A few months after its creation, terrified, I found myself wondering how it was that I came to be a feminist and belong to a group with these characteristics, an issue that seemed distant to me a few years ago.

It is also born from the need to revisit my own biography. I am a human rights educator, I have hope for change, so I am interested in stories of transformation. That is why I was also interested in learning about other paths, from other women with whom I interact on a daily basis. Perhaps because, as the psychiatrist Jean Shinoda Bolen points out, something similar happens with biographies as with archetypes: “we see ourselves reflected in the experience of another woman and we become aware of some aspect of ourselves that we were not previously aware of, as well as what we have in common as women”.

So I asked the women that I feel close to, although today they are all over Latin America, to give me their testimonies. Some have joined late, like me, and others have been studying and working on it for a long time. But they have all come to label themselves as feminists.

The question was simple: how did you become a feminist? I wanted to know what were the people, situations, reflections and sensations that led them to become aware of the condition of our gender and denounce it.

"I was not a Feminist" contains their stories, accompanied by illustrations inspired by them, with the purpose of helping us digest each story from the sensations and not only from the cognitive. They are stories that continue to be written, because we have a lot to learn and unlearn along this path.

In them there are many common topics: restlessness or discontent, emotional dependence, frustrations and professional challenges, theory and books. But something that runs through all the stories is the inspiration of other women. It seems that the slogan is true: to start a feminist revolution you only need a friend. However, I take advantage of this introduction to make a "disclaimer": in a Latin American context of ultra-segregated societies, our most intimate circles are almost always made up of people in conditions similar to ours. As a result, this book lacks gender, class and age diversity, since, as I pointed out, it was born as an intimate project, an experiment in sorority between friends and does not pretend to reflect the wide diversity of women. However, while the project has progressed, we are faced with the need to carry out a second part in which we can include diverse perspectives on sex, gender, class and age range, adding new stories.

I hope you enjoy this first version, dedicated to anyone who is interested in reflecting on their own path in feminism, no matter where we are in it. I also sincerely hope that these stories resonate with you, that they serve to generate greater degrees of selfknowledge and to give new meaning to your own stories.

Verónica del Pozo Saavedra Book coordinator I Was Not a FeministPrologue

Freedom, Equality and Fraternity. The ideal of the Republic fueled by a revolution, the French Revolution.

It would be logical to think that this iconic moment in universal history was not just a fight against the monarchy and its abuses, but progress for all. For everyone. But not.

As Nuria Varela and Antonia Santolaya recall in their book “Feminism for Beginners” (and the more I read about gender, the more beginner I feel) the French Revolution was profoundly machismo.

It was of little use that they starred in the march on Versailles in search of the king and queen. As an anonymous woman from the time recalls, despite the fact that the “revolutionaries” said that a nobleman could not represent a commoner, the men did feel they had the right to speak for the women and left them out of the National Assembly.

The last straw was when Parliament shouted to the four winds the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Just like that, of the Man and the Citizen. Only of them.

To denounce this discrimination, Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Women and of the Female Citizen. After this and other acts of rebellion, Olympe ended up... hanging.

Was Olympe a feminist? Logically, she was looking for something as simple as difficult to understand for many: equality, but true equality; not just for men. Did she know that she was a feminist and when did she become one? Impossible to answer, what is evident is that reality made it impossible for him to look to the side.

And so it has happened to many of us. From everyday life, we have witnessed the imbalance of power between men and women. First in the domestic space; with mothers who, if they worked together outside the home, also did so alone inside the home.

Later, we learned about machismo in advertising that exclusively dedicates products such as detergents to us that will make us happy because we will have more time to… take care of the children. As if we didn't need extra hours for ourselves, as if housework were our responsibility and so were the children.

And of course, we also saw in the public sphere the absence or scarcity of women in politics, in the economy. The disparate salaries, the positions still in 2018 prohibited. Never a Minister of Finance in Chile, never a President of the Supreme Court.

"I was not a feminist" is the name of this book and that does not last long. With an awakened conscience, by living, feminism becomes a necessity. Because feminism is nothing more than a synonym for equality only in the field of gender. It is simply wanting men and women to be born and live free and equal in dignity and rights, in opportunities and in the freedom to choose the roles they assume and the way they decide to live.

I read emotionally in this book testimonials from Mexico, Colombia or Nicaragua. I recognize common stories and they lead me (once again) to thank that feminist wave that in May 2018 reached a country like Chile: with long coastlines and still narrow possibilities for millions of women.

Because the young women who took to the streets put women's demands at the center of the public debate, because they made us question ourselves, because they forced me to read more, because they encouraged me to continue talking about leveling out a highly uneven field.

I know that I live this fight for greater degrees of equality from a position of privilege, but that forces me and all of us who share a public platform or who have greater resources, to look for others.

To help so that no one is left behind, so that gender is not a limit.

Because machismo, like any form of inequality (and those who wrote this book know it well) always affects those who have less the most. That girl who will be taught less math in public school than her bank partner. The worker who, after spending a couple of hours riding public transportation to get to her job, returns to her house to take on the housework alone.

That is why all those who aspire to freedom, equality and fraternity should be feminists. That is why men should also be feminists and renounce the privileges that accompany them from the cradle and that become invisible to them permanently. Because this world will be much fairer and happier when they say "I was not a feminist... and now I am".

The pessimists will be able to say: one wave and another of feminism throughout history and on the beach the sand is still dry. But it happens that the beach is no longer the same and we are not the same.

Mónica Rincón, Journalist, Chile.

Testimonials

My school uniform was missing a button. The fact would not matter so much if it were not for the fact that the uniform belonged to a convent school in Quito, the small capital of my country, and that day I sewed on the button when I got home, remembering how I saw my grandmother sew and well, no. I'm going to detract, with a little common sense.

When I was 12 years old, we were at the kitchen table, the one where all the daily family conversations take place, mine was quite traditional. That night my dad got very traditional. For some reason I commented on the button that I glued on the dark red jacket, which was combined with a checkered skirt, making all the girls look without any difference, perfectly uniformed and trained. In my house the Hail Mary or a rosary was never said at dawn, but if it was about quality education, then we had no problem feigning interest in the Wednesday masses.

The button. Yes, the button sewn by me that afternoon was the reason for my dad to answer me between spoonfuls of soup and: “Well, I think it's very good that you sewed the button. Now that you know how to sew, you can learn to cook too”.

Ipso facto, without a doubt, a heat made my blood boil and my hair stand on end. I took a deep breath and without pausing I moved my mouth to pronounce: "I tell you, dad, that sewing and cooking are things that are not in my plans."

María Gracia Sandoval Iturralde, Ecuador, 35 years old. Illustration by Pau Gasol Valls

María Gracia Sandoval Iturralde, Ecuador, 35 years old. Illustration by Pau Gasol Valls

A response that was not from a 12-year-old girl. Correction: that at that time it was expected of a 12-year-old girl. My dad was surprised by the solvency and the immediacy with which I replied. But the statement and the answer don't matter, the magic came immediately after. As soon as I answered, we exchanged glances with my mom and I could see her knowing smile, a proud and sideways line that was drawn on her mouth. That exact moment, my mother and I were partners, friends, allies and, without even knowing the word, neither she nor I felt sisterhood like an electric current.

My dad was surprised and immediately looked at my mom expecting an explanation for my irreverence. My mom kept her smile full of meaning and said absolutely nothing, because we both knew there was nothing to explain.

That loose button was revealing that my dad did not see in me the plans that, at the age of 12, I did manage to visualize. It was the red dot that made us talk and make it very clear what I did not want to do because it has always been more useful for me to be sure of what I do not want to do, above the things I would like to do -.

That social mandate became my biggest fear ever since, and I tried to express it in various ways: I mutilated my long, straight hair to wear a short bob well attached to my head, I refused for years to wear colors other than blue and black and my closet only kept pants with huge hems that dragged with each step. Only today I can understand that it was my way of refusing to be that girl-mold that I was expected to be.

I wanted more, but I was trailing insecurity, the kind that has been imposed on us since we were little girls and stalks us until it defeats us at certain times, because what we have been taught about being a woman is terrifying and exhausting. But despite this, I have been able to take refuge in a sheltered space that is sorority, and with that I want to stay.

I am lucky to feel it every day, not a day goes by that I do not share that feeling with other women, in the most banal situations and in the harshest figures of injustice. That containment current is happening in my body and in my head, even with women I don't know.

From that day on the button stuck well. Between my mother and I there is an understanding of the life of the other beyond the obvious mother-daughter relationship: we have been companions, women who show solidarity and support each other. And it was with her that I immersed myself in the swing of Arab dance, a space that has been especially significant. There I discovered with other women to love the body that they teach us to hate, to feel comfortable and content with them and to strengthen ourselves in freedom.

Now I stick and unstick loose buttons every day, deconstructing ideas, mine and those of others, about what it means to be a woman and there, without masks, is sorority.

I don't know what day I became a feminist, but I know I owe it to the strong women in my family, those who don't call themselves feminists today. Their life stories, which are also part of my history, taught me about the injustices, contradictions, challenges, and struggles that women face.

My great-grandmother was born 97 years ago in the north of Nicaragua, but when she was very young she moved with her father to a peasant community in the west of the country. She then got married when she was a teenager and God sent her 9 daughters and 3 sons. They never told me details, but as a girl I heard that my great-grandfather gave her a "bad life." The violence she suffered, the little possibility of deciding and planning her maternity, her devoted fidelity even in widowhood, and the death of her youngest daughter due to never-diagnosed cervical cancer, taught me about the injustices of being a peasant woman in my country.

My grandmother was also born in the countryside and got married at the age of 18. She and my grandfather believed that education, which they did not have, was the possibility of well-being and freedom for their 3 daughters and 3 sons. At the age of 36 they moved to the capital where their eldest daughters were already studying. My grandmother opened a business in Managua and since economic independence, her strong personality and her captivating leadership in her neighborhood and her church, she challenged in the public sphere the role she had been assigned to be a woman. But, at home, she continued to take over the kitchen, serving and washing her husband's dishes and forgiving seventy times seven as God intended, all my grandfather's infidelities. Her story taught me the contradictions of being a working woman in my country.

Laura Lacayo Espinoza, Nicaragua, 27 years old. Illustration by Diego Flisfisch.My mom lived most of her life in Managua. As a child, still in the country, she assumed the role of her older sister taking care of her brothers. As a young woman, she collaborated with the fight against the Somocista dictatorship and, during the Sandinista Popular Revolution in Nicaragua, she voluntarily went to war to defend the revolutionary project. Subsequently, she led a local organization that works for the sexual and reproductive health of women, where she learned very closely about the violence suffered by girls, adolescents and women in the supposed "sixth best country to be a woman" (according to the Economic Forum World). My mom learned to be brave, strong, and rational in the mountains, the game, and the world of work to earn respect in traditionally male leadership spaces. Those values were paramount to being a single and financially independent mother when my dad passed away and my sister and I were still little. Today, many years later, she is learning to embrace her emotions and find personal fulfillment beyond the self-sacrifice of motherhood. Her story taught me the challenges of being a mother and a professional woman in our society.

The story of these 3 great women continues with my story. When I was little I played with barbies, baldheads and kitchens as well as with puzzles, books and chess. They pierced my ears at birth, they dressed me in pink and I sang and I confess that I still sing at the top of my lungs songs by Shakira where love is pain, dependence on your partner and elimination of your identity as a person. However, my mom and dad taught my sister and I with words and actions that we could be anything we wanted to be. It was, perhaps, my first apprenticeship on the path of feminism.

In that journey, my first march at the age of 15 was transcendental, to which I went with my mother and one of my best friends ever since. It was 2006 and women's sexual and reproductive rights in Nicaragua were going back 100 years by eliminating the figure of therapeutic abortion and penalizing it completely. The indignation that this decision of the Nicaraguan political parties generated in me, in open alliance with the Catholic Church, was the beginning of my closeness to feminist activism and to join in believing and defending that we should decide about our bodies.

I remember back then I didn't want to call myself a feminist, it scared me. But not because I found it offensive, but because I saw it as an honor that I didn't deserve, as a title that only some with more experience, consistency, studies and gray hair than mine deserved to carry.

And even with the fear of the label, my comments gave me away and I was many times the "crazy feminist" in spaces at my university, my work and my volunteering. I was reflecting while growing up, along with books and conversations with other witch friends, about our personal experiences: the first bullying, the dependence on walking with a man to feel safe, the first abusive relationship with a partner, the fear of men of women Arrechas (as people who have a strong or angry attitude are called in Nicaragua), the expectations of romantic love, the pressures on the duty of our bodies, the frustrations of not being listened to by men in roles of power, the questioning of male bosses in my work about my feminist activism, the request for support from women to get out of the cycle of violence, the rape of a friend that we did not recognize as such until many years later or the calls for support to access a safe abortion in a State that penalizes it. My story has taught me the personal and political struggle involved in being recognized as a feminist woman in our society.

I don't know what day I became a feminist, but little by little, by embracing my family, personal, and other women's history, I began to understand that being a feminist is not a title that one must deserve or a point of arrival. It is letting yourself be inspired by other women and joining this vital and liberating path where we find ourselves, questioning, deconstructing and we manage to lose our fear of being uncomfortable, of putting on purple glasses, raising the purple flag and the green scarf to fight daily for our Rights.

María Francisca Stuardo Vidal, Chile, 31 years old. Ilustración by Héctor Ruiz “Chaochato”.

They always laugh at me because I tell the stories in a spiral. It took him years to narrate how I stepped in a puddle when I went to buy bread. I am more interested in describing the texture of a fabric than clarifying what it is for and my news criteria go more hand in hand with rarity than with social relevance. It's that I like the details.

For this reason, I want to give context to my personal story: two women like sisters, a heteronormative family, a Catholic school for women, an active participant in religious groups and a provincial in a Chile that can be summed up as what can be achieved in Santiago. In my world, dad's nap is respected because "poor thing, he works all week." In this micro universe, abortion is synonymous with madness, virginity is a control of quality and integrity; language and its appropriation are linked to biology.

I also come from that part of matriarchal Chile, which is outlined with a family of warriors, of women who take care of and of aunts who assume nephews as children, of widows who raise the litter, of women for whom the end of the month is a constant threat. I would not take it into account until much later, but it refers to me like a feminine force that flows through my veins, a fighting heritage that I cannot, that I do not want to ignore.

As a child she was awkward, stubborn, inquisitive, inquisitive. They called me "Gladys Marín" as a form of contempt. I received it firmly, while inside I questioned the world, which gave me lessons, instead of explaining the why of things.

At that age, my dream was more to learn to draw than to become a ballerina. Not so much because I didn't like to feel my body moving, but because my aunts said that it was too “electric” to do it well. I was funny, but not graceful.

When I grew up, humor was my refuge for what I didn't have. Actually, for what I thought I didn't have. So was reading, the desire to learn. Dreaming that one day I would tell stories from different latitudes, that I would interpret many voices and that I would be the best at it. Meanwhile, out there, in that cosmos surrounded by schoolgirls, being wanted was the free way to public recognition, a highway to personal fulfillment.

Years later, after graduating in journalism, I fulfilled my dream and went to Haiti as a volunteer, one year after the earthquake that displaced more than 600,000 people. I told my editor that I would no longer work for the newspaper, so I packed my life into a couple of suitcases and left. I left behind the questions of why I quit my job a good and prestigious job and a boyfriend a good man who perhaps wouldn't wait for me—to “try my luck”.

That trip was the possibility of experiencing the profound happiness of feeling universal, finding my voice, telling stories through images, embracing my political positions without fear of defending them and clinging to the radical hope of changing the world. I went through markets hugging women I didn't know, entranced by their strength and their joy in fighting against the violence that stalked them daily; I shared laughs and jokes regardless of the language, I danced in the street, celebrating the sunsets. I loved, I loved myself deeply and in absolute freedom.

I confess that the most difficult part of leaving Chile was coming back. Return to the old questions, about me, my decisions, the revival of that inquisitive and inquisitive girl. Despite this, I still did not understand why, when and how the scales never tipped in our favor.

A few months passed in which I moved through a micro-habitat, very much mine, with my body in one place, but my head and heart shared. I promised myself not to stay in Chile for too long, for fear of transforming myself into a shell without content.

There were my other sisters, my friends and teachers. Those that I was collecting on trips, jobs, unsuspecting coffees, drinks and dances. The ones who got excited about every decision, no matter what lay ahead. The ones that were overturning seeds of restlessness, random phrases, heartfelt hugs. Those became my family. Comfort. Confidence. Love.

In the following years, I visited many countries in Latin America, some with a planned route and others for an indefinite period, like today, when I am still outside of Chile collecting memories and stories. Many of them alone. Alone. How heavy is that word, when they ask you: “And you, did you come alone? Don't you have a family? As if having my energy and my healthy body was not enough. Just like when I was nine, at 29 being a woman and not fitting in with the predestined idea of who I should be made me an insufficient character.

For the first time, I was faced with building a home just for myself. To inhabit it and with it, move through a new space in which I was transforming wild places into familiar spaces; I understood that the table looks just as beautiful when only a plate decorates it; I exercised the habit of asking myself the same things and answering myself, to see if one of those surprised me. I learned to take mental photos, to capture the light of those spaces and wrap myself in it, to the sound of music, to the beat of a good book.

Throughout this journey, home took on another dimension and was built like a shell that I carry on my back and accompanies me wherever I go. Traveling that path, my body was also exposed and allowed to be transferred by the murders of so many sisters, at the hands of those who do not conceive that they are only theirs. Tears welled up over and over again reviewing the news, with the impotence of knowing that this could be the fate of any of us travelers.

There was news that tore me apart, that deprived me of the peace of living alone. My body trembled with the violence that plagues us in the streets, in the neighborhoods. The change from grief to rage was light: I felt that by violating her body it was also mine that was stretched out like a battlefield, within a war that we did not choose to fight.

From physical violence, I was discovering those others in which the fight is much more subtle. The one I had with my body, with talking a lot, with laughing out loud, with warming up, with provoking debate and demonstrating dissent. With understanding that the law, the economy and the press are used to keep us where they always want us: cornered.

Feminism then became a trench and the needle that threads my story, that gives it meaning and that allows me to see today all the discomforts I faced. It is the meter of my mistrust, my fears, my insecurities. Feminism gave me meaning and sustenance. He taught me to inhabit myself, to explore the territory with a critical but alert lens. She took away my burdens and taught me that love for other women was nothing more than a clear sign that our reality is shared. Feminism also gave me the possibility of embracing myself and “apapachar” or “embracing with the heart”, as the Mayans say. To build collective dances, feeling protected and caring, as a responsibility to make this fight last. To memorize phrases that uncover new paths to travel. To revisit love, build alliances. To hold hands with another, no matter who it is, because we have so much in common that we don't need to introduce ourselves.

Today, there is no longer any guilt for not giving birth, for giving an opinion, for contradicting, for questioning. Today I can be attractive, funny, intelligent and close. Today I can be what I propose and everything will be fine. No matter what the world out there says, today I am finally perfect for me. My house is on my back and I believe so.

Laura Sofia Martínez Quijano, Colombia, 33 years old. Ilustration by Carolina Celis.

I must confess that I have never considered myself an active feminist. In fact, I refused to say that it was, on the one hand, because I did not identify with the concept, but also because I consider that it is difficult for me to incorporate it into my daily life, it is difficult for me to use inclusive language, I even made fun of its use, I I complicate and entangle myself by referring to myself, girls or women (cis or trans) as "one" instead of the so normalized, idiotic and generalized "one", and, still, even surrounded by the most admirable feminist friends, I feel that day by day I am "building" a concept that still seems completely new to me.

But forced to face my story, I also ask myself, how come I was not a feminist from the cradle? How is it that surrounded by so many women who have marked and guided my path, who have taught me through actions and examples what courage, strength, determination and, above all, the power of women are...how is it that I don't feel do I take care of that being a relentless feminist?

Last year, life has forced me to carry out an exercise in deep selfknowledge, it has put me to the test in a way that I always thought I would be immune to and those experiences led me to rebuild and identify who have been the people who marked me and for which today I have a "defined" identity... and they have all been women! Women ahead of their time, warrior women, peasant women, beautiful women, and, as we say in Colombia, barraca women.

Paulette, my paternal grandmother, a Belgian, decided in 1940, in the middle of World War II, to take a ship to the United States to meet my grandfather, a medical student whom she married by mail through the consulate. It is the typical love movie, in which a woman leaves everything for the beloved and promised man, who will save her from being part of the tragedy of a war. On the contrary, it was a woman who, at the age of 20, refused to be part of a boring European society, looked for a handsome Latino, asked him to marry her, and arranged everything from a distance to go on an adventure that she wrote herself. She so refused to depend (as was done at the time) on a man defending her that she bought a gun to ensure her own safety and led a group of foreign women in Colombia to emancipate themselves from their husbands.

Sofia, my beautiful maternal grandmother, was born in a city where women are known for being "strong," strong, loud-voiced, and outgoing tempers, all with negative connotations and stigmatizations of "complicated" women. A woman so beautiful that Neruda himself wrote a poem for her when he met her in Colombia. When we told her it was because of her beauty, she always replied: "Don't offend me, it wasn't because of beauty, but because of character." I will always remember how she told me that her only unfulfilled dream was not having studied law, because her father and brothers forbade it, "why can a woman never rule the law." Thanks to her "character" and strength, despite not having had a law degree, until her last days she sought to do justice to the most excluded people in Bogota society. One of her great friends, today one of the most well-known poets (a member of the Communist Party) in Colombia, when I went to her house to have tea, I would sit next to her and say: “Mijita, if we are not the ones who wrote the stories and we have our voices up, the world will continue to be told by men, and we are not going to get anywhere that way”.

Years later I had the great privilege of working hand in hand with some women and now friends, absolutely brave and an infallible example of resilience. Consu, Emita, Rocío, Inés, and many other leaders taught me through their work and their love for their family that when one is loyal to what is theirs and to the people around them, there is no way not to survive and get ahead.

Inés is a leader who comes from Los Llanos, a region of Colombia marked by war. After being displaced from their lands, she arrived at the settlements located on the outskirts of Bogotá, a place where violence and exclusion from the armed conflict is reproduced and replicated, one that has left women the greatest victims. As soon as she arrived in Brisas del Volador, she organized a group of women called ASOMUMEVIR, Association of Women for a Better Living, in order to give the women of her neighborhood a space to meet, welcome, unite and rebuild. A place where they could also look for alternatives for a better quality of life that war, gender violence, patriarchy and social structures did not allow them to have.

Inesita, after so many years, remains loyal to her neighbors and companions, because she always told us that it was the only way to face the injustices that life inflicted on them. Professors, teachers, sports partners, parties, discussions and trips, grandmothers, mothers and friends, all women... are the ones who, at each important stage of life, have taught me how powerful and indomitable the strength of a woman is, and how this is millions of times greater when it is allied to another.

Rebuilding my story, I realized that I am a firm believer that loyalty between women is unrivaled. That the true rivals of women are the beliefs that the patriarchy has imposed on us, prompting us to compete, to envy, hate and jealousy to divide us and diminish the great strength and true power that a group of women generates.

So I question myself, with all this responsibility in my hands to follow their example, how is it possible that I am not a true and profound feminist?

I question myself then, with all this responsibility in my hands to follow their example, how is it possible that it is not a true and profound feminist? What am I missing to be? Or am I already one and I don't consider myself as such?

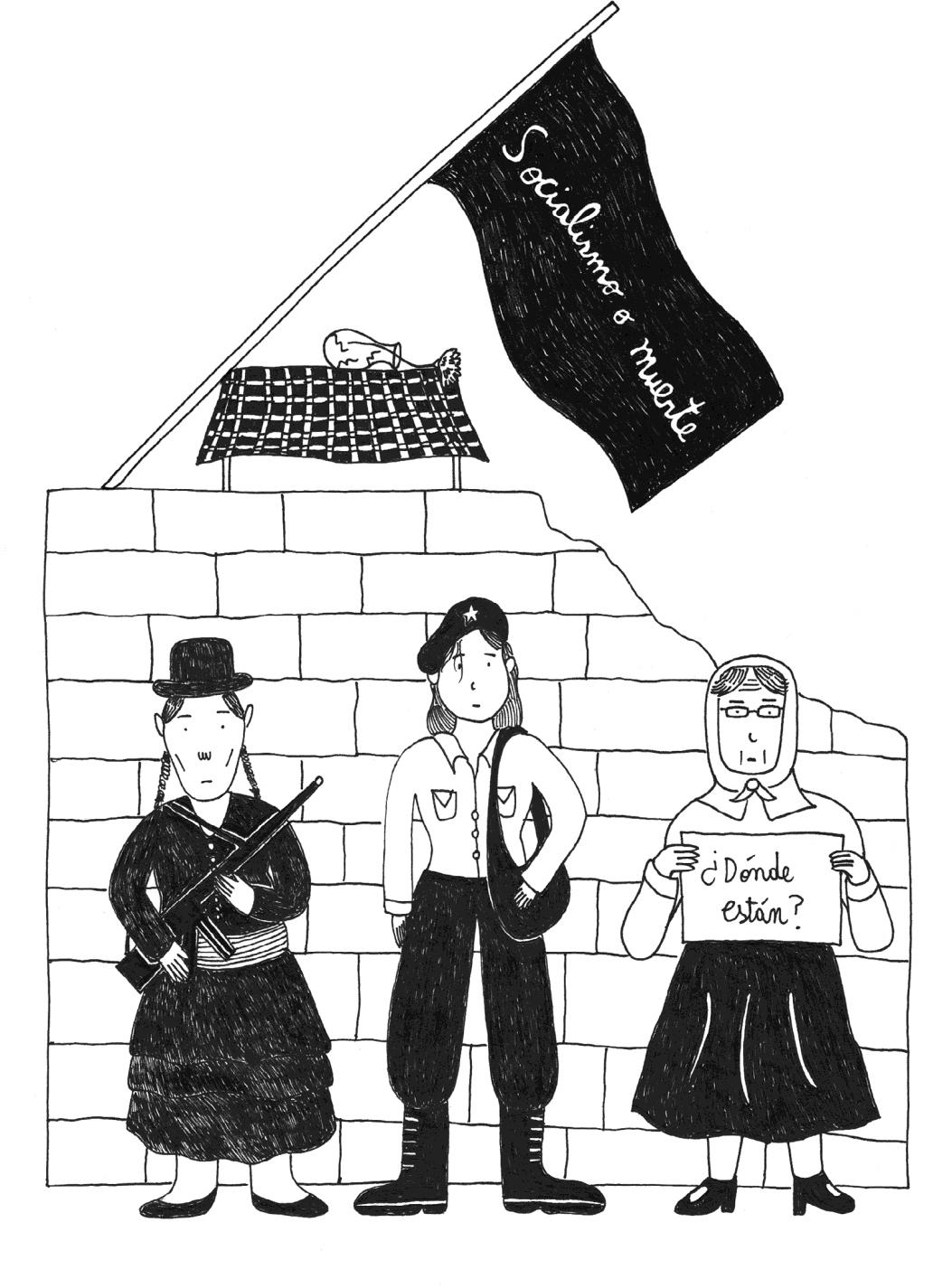

Catalina Bosch Carcuro, Cuba, 44 years old.

Illustration by Sofía Flores Garabito.

I was born in Havana in the 1970s, the place where my mother arrived, a Chilean exile after the Coup d'état, together with my father who, although he was Cuban, had been wandering the world and uprooting himself for several years.

Being a girl in this Cuba was being a pioneer, wanting to be like Che and being part of every moment in which Fidel was applauded. I remember getting ready to go to the marches in the Plaza de la Revolución and feeling the emotion when I saw the Comandante appear. Thanks to him, and to those who accompanied him in the fight against the Batista dictatorship, we lived in an enchanted world. Not even Yankee Imperialism had managed to defeat us at Playa Girón and I felt completely certain that if they invaded us again they would perish in the attempt to subdue us. My land was a safe place. We did not lack to eat, to have fun, to educate ourselves, to heal ourselves and to fill our hearts with shared hopes. That's why a part of me was always calm, confident and joyful. But not another part. There was a place where the Revolution did not reach, nor Fidel, nor the example of Che, nor hope. In my house my dad hit us, yelled at us, insulted us, broke things for whatever reason made him angry. It was a classic Sunday: my mom couldn't have lunch at the time he wanted and then the monster would wake up, destroying everyone in its path. Many times I tried to avoid hitting her and my little brother, I learned to do things around the house and cook to have everything ready when he wanted.

Already in the 80's, my mother began to work at the Cuban headquarters of an international organization for women. There they carried out the beautiful work of strengthening, gathering and training women leaders from different countries of Latin America. They worked hard against all injustices, both those that occurred outside and inside their homes. It was there that I met the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, Combatants from Nicaragua and El Salvador, Peruvian Peasants, Community Leaders from Brazil and many others. With their cute costumes and accents, with their energy, conviction, courage and sweetness, they allowed me to listen to a strange and fascinating song. They talked about the dictatorships and wars that afflicted their peoples, about hunger, misery, violence against women and the right to decide over their own bodies.

In Cuba, there was no talk of gender, patriarchy, machismo, child abuse, or sexual abuse. The Revolution and Socialism were supposed to have ended all social problems. The only thing I remember close to these concepts was "proletarian chivalry", a value that in the speech he tried to promote to boys, with the idea that they be kind in their treatment of girls.

But thanks to that network of women who brought ideas from other places and to the fact that my mother was allowed certain "ideological deviations" because she was a foreigner, I began to hear about feminism, gender, equality between men and women. Then that part of me that had never felt hope began to smile.

I became a teenager. The Berlin Wall fell. In Cuba they shouted Socialism or Death. At school we read Casa de Muñecas and I was happy finding a space for the first time to talk to my classmates and the teacher about what "El Portazo de Nora" meant for the women's movement. At that point, a dating relationship had ended in which I suffered many types of violence for more than a year. We had left home without my father and I was still hiding in fear from a neighbor, the father of my best childhood friend, to not touch my genitals again.

These days it gets dark later in Santiago de Chile, where I have lived for a quarter of a century. Spring prevails with its blossoming plum trees and the song of the birds. In the first years of being here I did not distinguish that beauty and my longing for the Caribbean Sea was persistent. This city was too gray, blue, brown and black like the clothes of the people. It was not right to talk about exiles, disappeared or torture. The women called it “getting better” when they were going to give birth and “being sick” when they had their period. There were illegitimate children, no couple could get divorced, and termination of pregnancy was not allowed under any circumstances. I never listened to “Te Recuerdo Amanda”, except in some nostalgic and remote Peña de Izquierda.

Santiago was dark, but it was changing color. Today my daughter goes with her green scarf around her neck to the march for the legalization of abortion. My college class writes a public statement supporting victims of sexist abuse. Many paint canvases purple and talk about gender, finally understanding that it is not the material with which clothes are made, but rather the material that often gags our mouths. Today my surviving patients of sexual abuse dare to tell what happened to them and go, like a bird singing on a plum blossom, to conquer the joy that was previously denied to them.