10 minute read

Manon Benders

interview with Manon Benders

Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital at UMC Utrecht is home to the most expert knowledge relating to neonatal neurology in all of the Netherlands. This children’s hospital is one of the nine Dutch specialized maternity centers. We spoke to professor Manon Benders about studying babies’ brains prior to birth and in premature babies, stem cell research, and the ‘soft’ side of research.

Text: Marleen Hoebe and Jim Jansen Photography: Bob Bronshoff

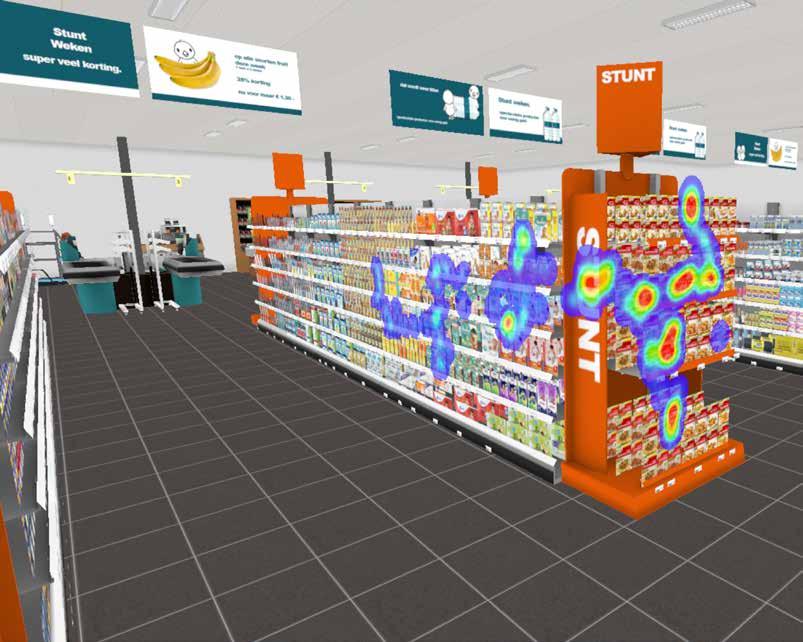

Can you study babies’ brains? ‘I was in Geneva last year, where I learned about a special application of MRI technology from a neonatologist, whose experience was mostly with newborns. This technology allows you to measure the size and maturity of the brain directly after birth. This knowledge has enabled me to put together a research group. We are now also studying the brains of babies prior to birth, in collaboration with gynecologists. Because life doesn’t begin at birth; the baby is alive and is developing in the womb. We place the coils of the MRI scanner on the mother’s abdomen. This gives us an image of the entire baby, and allows us to study the brain in detail.’

Are newborn babies affected by the MRI scanner? ‘There are no risks related to MRI research, because it uses magnetic fields and not radiation. The scanner does make a lot of noise, but newborns are given triple hearing protection. First, they are given yellow earplugs, then earmuffs over that, and, finally, an acoustic hat that blocks a third of all sound. The children just go on sleeping.’

What do you see on the brain scans? ‘In the final trimester of pregnancy, the brain develops from smooth to folded, just like the adult brain. This development takes place over the course of ten weeks. It’s incredibly fast, very bizarre. ‘The brains of premature babies, born from twenty-four weeks, are completely smooth. Their brain development takes place in an incubator at the hospital. In the incubator, the conditions are very different, and the process can be disrupted by the medication they are given, or by the ventilator they are on.

‘The brains of premature babies are often a lot smaller than those of healthy babies. They are often surrounded by a lot of fluid and water. If you were to measure the circumference of the skull, it would seem they their brains are the same size as those of healthy babies, but that is not the case. We see that many of these children have developmental problems, such as behavioral, learning or psychiatric disabilities, later in life. The brain lags behind. The question is whether they will, ultimately, catch up and whether we can influence this development. That is what we are currently studying.’

How do you study whether premature babies are able to catch up? ‘For us, it is a must to see babies again after motor development and psychological development. And doctors also look at the number of hospitalizations and the quality of life. Sometimes these doctors build up such a good bond with the parents, that they are later invited to a patient’s graduation or wedding.’

Do you find that premature children experience severe problems in later life? ‘It depends on what you mean by severe. Many children continue to have problems, such as ADHD. But many people with ADHD lead wonderful lives. A large percentage of these children also display characteristics of autism. These children are less likely to have a relationship or a job in later life. Sometimes, they have difficulty holding their own in society. Occasionally, there are distressing cases, such as children with multiple severe disabilities. Fortunately, that is a minority.’

Can these distressing cases be prevented? ‘In the Netherlands, we adhere to a limit for premature babies. Babies born at less than twenty-four weeks are not actively

treatment, to see how they are doing. It is only when you know that, that such intense and radical treatment can be justified. We want to know how they develop. After they have been released from the hospital, we see the children periodically from the due date of forty weeks – at six months, fifteen months, three and a half years, five and a half years, and eight years. We monitor cared for, because their chances of survival are so slim, and they are likely to experience severe problems in later life. Half of the babies born at around twenty-four weeks survive. After that, the chance of survival increases by 10 percent with each week of pregnancy. After twenty-five weeks, there is a greater chance that the baby will survive.

detailed explanation of what they can expect. As long as parents are well informed, we are usually able to come to a decision together.

‘Sometimes the decisions are very difficult. When I was expecting my second child, I got a call from Tilburg when I was around twenty-four weeks pregnant. They had a premature baby there that was born at twenty-three weeks and was very active, and they were asking if we would treat the child. Saying no, when you are carrying a baby of around the same age, is terrible.’

CV

Manon Benders Born 24 January 1969 in Hellevoetsluis

1999 PhD in medicine, University of Leiden 2003 – 2008 academic position in neonatology, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital Utrecht 2006 – 2007 academic position, University of Geneva, Switzerland 2009 – 2015 neonatology staff member, University Medical Center Utrecht 2014 consultant and clinical researcher, King’s College London, UK 2015 – present professor of neonatology, University Medical Center Utrecht

‘Babies under twenty-four weeks are born, but not treated in intensive care. We always take into account whether the intensive care that the child requires, but that can do damage, bridges the situation to improvement. If you know that children may be severely handicapped, we believe we should not treat them. This is done from love, to prevent severe suffering.’

How do you decide to terminate treatment? ‘When expectations are that prospects will be grim, we always make the decision with a team of doctors, nurses, and, if necessary, other specialists. We take into account how many radical treatments would follow. The final decision is always taken in consultation with the parents. The parents receive a

Where does this interest in premature children with developmental difficulties come from? ‘Very early on, in the second year of my medical studies, I knew I wanted to be a neonatologist. I was attending the birth of twins at twenty-six weeks. I found it so fascinating that I thought: this is the work that I want to do. I was interested in cognitive development of babies born prematurely or with difficulties.’

What has been discovered within neonatology in recent years? ‘Neonatology is rather a recent development. In the past, it was practiced by gynecologists. It wasn’t until the 1970s and 80s that the field really took off. In the Netherlands, it is very well organized. Mothers who are about to give birth prematurely are transferred to one of nine specialized centers. This means that the appropriate support for child and mother is available.

‘A great deal of progress has been made. The greatest breakthrough was right before the turn of the century, with surfactant, a drug that develops the lungs, ensuring a high chance of survival for babies with very immature, damaged lungs. Another important step is the drug that we give mothers prior to delivery for the development of the baby’s lungs. This means that babies have to spend less time on respirators and there is a less risk of cerebral hemorrhaging.

‘At first, we were preoccupied with the technical side of the field. Now we are going in the softer direction. We are more concerned with the babies’ comfort and

whether they are experiencing pain or stress. We also want to involve the parents much more in the care of these babies. At the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) we are switching from eight beds in one large space to single rooms, so parents can stay with their babies. We believe this is better for the parents and the children. I think this is one way to make even more progress.’

What would you like to accomplish with your research? ‘Ultimately, we want to use brain scans to predict how premature babies will develop. That is why it is so important to see the children again further down the road, so that we know which factors and which brain structure will play a role early on. This will enable us to begin treatment sooner. We can already predict cognition at early primary school age, because we can look at the network connections between the different areas of the brain. But life is

more than just a high IQ.

‘I believe solutions are not only to be found in imaging. The children are hooked up to all kinds of measurement equipment. Everything is monitored: brain activity, heart rate, breaths per minute, any disruption in oxygen levels, lab results, radiology results, every dirty diaper, when they are fed, how often they spit up, whether they experience stress, how often they are given attention by their parents, and many more things observed by the nurses. We want to combine this (big) data with brain scans, readings taken using EEG, and long-term development. For this, we need smarter people than doctors. Physicists and mathematicians can use this data to create a prediction model. We would prefer a system that notifies us when a child is getting too much or too little of something. ‘Stem cells are also the future. They go to wherever there is damage, like magic. They

repair damaged tissue. This applies to brain damage, damaged lungs, and maybe even to damaged intestines in children with severe intestinal problems. We now have permission from the ethics committee to give stem cells to newborn babies with cerebral infarctions.

‘As we speak, we are also working on a major European application. Together with other researchers, we want to treat various groups of newborns with stem cells, for example, premature babies with lung problems. Our share of this study will cover stem-cell therapy for babies with brain damage due to lack of oxygen before, during or after birth. It is not yet clear whether this application will be granted, but we do expect that stem cell therapy will improve the care of newborns within ten years.’

What does the future look like for neonatology expertise here at UMC Utrecht? ‘We have officially been recognized as having the most expert knowledge of neo

natal neurology in all of the Netherlands. This recognition is given on the basis of various criteria that you provide, such as care, education, and research. Doctors often come here from abroad to learn about the brains of newborns. ‘We also want to impart knowledge and to learn from others. That is why we want to work with other institutes in Edinburgh, London, Munich, and Toronto to bring together various expertise. Collaboration also provides a larger and more varied patient population, which allows us to find answers to more problems. It will enable us to compare patient populations.’

Have you learned from foreign hospitals yourself? ‘Yes, I have travelled to various places around the world to increase my knowledge of neonatal neurology, which I was then able to apply here. Every doctor should really work at a few different hospitals. Otherwise you will only ever do things in the way you were taught at your own hospital. Other hospitals show you that there’s more than one way to get a job done, because every hospital does things just a little bit differently. But more importantly, things that are done better elsewhere can be applied at your own hospital. Everyone should work on cross-pollination.’