MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE PAGE 24

KWANZAA’S SEVEN NIGHTS OF LIGHTS PAGE 11

FROST LIKE A BOSS

PAGE 31

DOULAS DELIVER HOPE TO MOMS

PAGE 33

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE PAGE 24

KWANZAA’S SEVEN NIGHTS OF LIGHTS PAGE 11

FROST LIKE A BOSS

PAGE 31

DOULAS DELIVER HOPE TO MOMS

PAGE 33

More extreme weather is on our horizon. What happens to Missouri communities when the calm after the storm doesn’t come?

PAGE 12

THE VOICE OF COLUMBIA DECEMBER 2021The “It’s Not Like I’m Drunk” Cocktail

2 oz. tequila

1 oz. triple sec

1/2 ounce lime juice

Salt

1 too many

1 automobile

1 missed red light

1 false sense of security

1 lowered reaction time

Combine ingredients. Shake. Have another. And another.

Never underestimate ‘just a few.’ Buzzed driving is drunk driving.

Igrew up in the foothills of Kwa-Zulu Natal, a province on the east coast of South Africa that flanks the Indian Ocean. My fondest memories are of family holidays at the beach, eyes stinging from the salty water and hands marred with wrinkles from being in it too long. After an ocean dip, I’d grab warm fries and a grilled cheese from the local truckshop, prop myself up against a towel laid across my parents’ tailgate and snack away.

Happiness for me was spending summers this way, something I never really considered would change in the immediate future. But, it turns out, changes were coming more quickly than I could’ve anticipated. Climate change has taken the world by storm: The planet is warming, sea levels are rising, and severe weather events continue to devastate communities worldwide.

Since the 19th century, humans have heated the planet by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit, according to The New York Times. This has largely been caused by burning fossil fuels for energy — an activity that this summer initiated scorching wildfires in the West, widespread heat waves and severe

flooding in the Midwest and heightened natural disasters across the country.

As scientists have long predicted, the more temperatures rise, the more frequent and intense natural disasters will be. This is something that’s only been exacerbated by countries’ delay in minimizing their carbon emissions. During the aftermath of intense summer flooding in many Midwestern cities, it might have been easier to focus on the destruction in the wake of extreme weather events instead of what’s causing it, but time is no longer on our side.

In this issue of Vox, we explore how people affected by natural disasters in Missouri rebuild against the stark backdrop of global warming and American idealism (p. 12). The Midwest is no stranger to these types of disasters, which manifest in the form of extreme weather events that wreak havoc in small, often rural and isolated communities and elicit little federal recognition or financial support.

Join us at Vox in recognizing not only how Midwestern communities rebuild time and time again, but also how they define themselves and their legacy in the aftermath of tragedy.

MANAGING EDITORS EMMY LUCAS, REBECCA NOEL

DIGITAL MANAGING EDITOR GRACE COOPER

ONLINE EDITOR KATE TRABALKA

ART DIRECTORS MAKALAH HARDY, MOY ZHONG

PHOTO EDITOR MADI WINFIELD

MULTIMEDIA EDITOR ALEX FULTON

ASSISTANT EDITORS

CULTURE HANNAH GALLANT, TONY MADDEN, EVAN MUSIL

EAT + DRINK VIVIAN KOLKS, MADDY RYLEY

CITY LIFE SAVANNAH BENNETT, JARED GENDRON, COLIN WILLARD

DIGITAL EDITORS TIA ALPHONSE, PHILIP GARRETT, SASHA GUMENIUK, ALEXANDRA HUNT, SHULEI JIANG, HANA KELLENBERGER, KATELYNN MCILWAIN, ZOIA MORROW, JULIAN NAZAR, ANNA ORTEGA, RASHI SHRIVASTAVA, NIKOL SLATINSKA, CEY’NA SMITH

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS NOAH ALCALA BACH, LAUREN BLUE, ANGELINA EDWARDS, ISABELLA FERRENTINO, ATHENA FOSTER-BRAZIL, ANNA KOCHMAN, CHLOE KONRAD, CELA MIGAN, ELISE MULLIGAN, MIA RUGAI, DANNY RYERSON, ANNA SAGO, STEPHI SMITH, SOPHIE STEPHENS

MULTIMEDIA EDITORS ERIK GALICIA, AUZZIE GONZALEZ, CARA WAGNER

ART ASSISTANTS SIOBHAN HARMS, JACKIE LAMB, MARTA MIEZE, HEERAL PATEL, BRADFORD SIWAK

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR HEATHER ISHERWOOD

DIGITAL DIRECTOR SARA SHIPLEY HILES

EXECUTIVE EDITOR LAURA HECK

OFFICE MANAGER KIM TOWNLAIN

Courtney Perrett Editor-in-ChiefFor a feature about the Columbia Civic Orchestra, photographer Owen Ziliak went into the rehearsal space in the Sinquefield Music Center. The group of professional and amateur musicians practices there weekly. Ziliak says the photographs are meant to transform sound into sights. “Music is all about depth, space and time,” he says. “What might be the greatest thing about music is that you don’t need your eyes to experience any of it. When creating these portraits, I want the viewer to experience the music without hearing it. In my photographs, my camera is my instrument, the lights are my bow and the shadows are the notes. And your eyes are ears.” Clarinetist John Bell is in the orchestra.

Correction: A story in the November issue should have stated that recycling pickup is biweekly.

Vox Magazine @VoxMag

@VoxMagazine @VoxMagazine

ADVERTISING 882-5714

CIRCULATION 882-5700

EDITORIAL 884-6432

vox@missouri.edu

CALENDAR send to vox@missouri.edu or submit via online form at voxmagazine.com

TO RECEIVE VOX IN YOUR INBOX sign up for email newsletter at voxmagazine.com

DECEMBER 2021 VOLUME 24, ISSUE 9

PUBLISHED BY THE COLUMBIA MISSOURIAN

320 LEE HILLS HALL

COLUMBIA, MO 65211

MAGAZINE

Cover Design: Moy Zhong

Of the more than 130,000 people evacuated from Afghanistan in August, about 1,200 will resettle in Missouri. The state ranks in the top 10 of states receiving Afghan evacuees, according to U.S. State Department data. Dan Lester, the executive director of Catholic Charities of Central and Northern Missouri, estimates about 300 Afghan refugees will settle in mid-Missouri.

The evacuation began as the United States prepared to end its longest war by withdrawing troops from the country Aug. 30.

Catholic Charities is the resettlement agency for refugees relocating to mid-Missouri. As an affiliate of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, one of nine national resettlement agencies, the organization has welcomed refugees to mid-Missouri for more than 45 years and helped more than 4,000 refugees. The agency had assisted 110 Afghan arrivals as of Nov. 9.

People fleeing Afghanistan face several barriers to finding refuge. According to Refugee Council USA’s website, the resettlement process begins when candidates are referred by the United Nations Refugee Agency. Then, refugee officers from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security interview the candidates. If the candidates are approved, they complete health screenings and receive any necessary medical care. The Refugee Processing Center obtains an assurance for the candidates from one of the nine national

refugee resettlement agencies. Assurances confirm that a local agency can receive the candidates. Once resettlement agencies confirm assurances with local affiliates, refugees travel to the communities where they will resettle. Tens of thousands of Afghans are on U.S. military bases waiting to be resettled by local agencies.

As refugees enter the U.S., nonprofits such as Catholic Charities and City of Refuge are integral in the process of making sure people receive support to rebuild their lives.

The first face refugees see when they arrive in Columbia is someone from Catholic Charities greeting them at the Columbia Regional Airport. “When you see people coming off the airplane, and they’re smiling, and they feel safe, and they feel secure, then that really can help give you the energy to keep pushing forward, to try to make a positive change,” Lester says.

From night one, Lester says Catholic Charities and community sponsors — religious groups and community groups such as mosques, synagogues and rotary clubs — provide refugees with immediate needs, including housing, clothing, bedding and culturally appropriate food.

These groups handle resettlement in a way that spreads the workload among volunteers and sponsoring groups. Volunteers take on some of the day-to-day tasks of helping people integrate and become comfortable in the places they resettle. “It helps newly arrived refugees to more quickly feel at home in their new surroundings because they have a community that wraps their arms around them and really welcomes them,” Lester says.

After refugees have physically settled into their new homes, charities continue to help them adjust to their new environments. Sponsoring groups help with orientation to American grocery stores, public transportation, obtaining driver’s licenses, finding employment, accessing healthcare and enrolling children in school.

Unlike Catholic Charities, City of Refuge is not a resettlement agency, which means that the organization helps people after their inital relocation. Leah Glenn, the program coordinator at City of Refuge, says the nonprofit remains as a resource to refugees no matter how long they have been in the U.S.

Glenn says people first come to City of Refuge with many questions about learning English or finding a better job. “And then, as the years go by, they become better acclimated to life here,” she says. “They may have fewer questions, but maybe they’re wanting to know how to vote and understand more elaborate things with our culture.”

Jenifer Perkins, a parent educator at Columbia Public Schools, helps resettled families with groceries, English lessons, and finding community resources. “You get to know a lot about them, and you just form a great friendship,” she says.

Perkins says the families she works with learn about culture in the U.S., and she learns about the families’ cultures. “It’s been fun learning

To work with either organization, visit their websites for applications at cccnmo.diojeffcity. org or cityofrefuge columbia.org.

about the foods they eat, what happens at home and the difference between the parenting styles,” she says.

There are several ways to volunteer at charities that assist refugees, such as sorting files and donated goods, assisting with English language learning, helping at community events as frontdesk attendants or greeters, providing childcare or setting up an apartment for resettled people.

Catholic Charities has an Amazon Wishlist on its website that includes the most-needed items. Items on the wishlist include lotion, towels, detergent, diapers and baby clothes.

Lester says if you can afford to donate money, cash donations give the agency the most flexibility to purchase essential items, pay rent, stock fridges or take care of anything else that might be needed on a case-by-case basis.

Glenn says City of Refuge needs help obtaining items such as toiletries, clothing, furniture and cleaning supplies.

Local storm chaser Tanner Beam keeps an eye on the sky for tornadoes and other extreme weather.

BY SOPHIE MÉNARDWhen dark clouds rolled over Kansas City one day in 2005, Tanner Beam had no idea a terrifying experience was just around the corner.

Beam was 5 years old and sat in the back of his grandparents’ car while they drove him home. Despite his grandmother’s calm demeanor behind the wheel, he could tell the dark clouds behind them made her uneasy. Then a microburst –– a downward burst of wind and rain from a collapsing thunderstorm –– hit close to them on the highway. The wind became violent and tore down an Arby’s sign while a Taco Bell was being destroyed a few blocks down. Beam was terrified. “I just saw the raw power of Mother Nature that day,” he says.

Since then, Beam’s life has revolved around his passion for extreme weather. He set out to learn everything he could about meteorology, and he chased his first storm when he was 15. The 21-year-old is now a junior studying atmospheric science at MU.

When he’s not in class, he grabs his camera and follows the weather alerts to capture images, often with his friend Ezekiel Rice. “He thinks about meteorology every day,” Rice says. “He’s trying to learn more stuff every day, always planning his next step.”

Vox spoke with Beam about his experiences chasing after Mother Nature’s wrath.

Your heart is racing a thousand miles an hour. Every storm is different. They all have their own special beauty within them. It’s hard to explain. Each type of storm has its own rush. A tornado is going to feel

different than a shelf cloud. A boundary between a downdraft and updraft of a thunderstorm, or a big lightning storm, is different from a blizzard.

Which storm was the most impressive?

Is there a lot of waiting around?

Be prepared.

“(Storm chasers) have to at least have National Weather Service certified spotter training so they know exactly what they’re looking for,” Tanner Beam says.

Don’t chase alone.

“If you go alone, then technically you have to record by yourself, look at radar by yourself, and you have to drive,” Beam says.

“You’re more focused on looking at the radar than you are paying attention to the road.”

That would be a tornado I chased in 2019 in Kansas City. There was a tornado emergency, meaning a large destructive tornado moving through a densely populated area. We came across the damage right away. Trees were shredded of leaves, bark chopped right off the top, a white pickup truck got thrown into a ditch. That was very impressive. We got a little too close, though. We needed gas so we stopped at a gas station and got directly in the back of the tornado. We got in the car, went as quickly as we could and somehow escaped.

Yeah, sometimes storms don’t materialize at all. They’ll fizzle out, and you drove eight hours for nothing. You look at models throughout the morning and the day before. Then you pinpoint a location called a target area, which you’ll be heading to. You have to drive there before the storm has even formed to make sure you’re there on time. Then the storms could pop anywhere within that 50-mile radius. You drive to the storm and hope it will get going. Eighty percent is complete boredom.

Is storm chasing fun even when you don’t see anything?

It’s fun going down country roads, blasting music with your friends waiting for a storm to pop. Going bowling or eating some food at a restaurant before the storm, waiting for it.

While others are seeking refuge from a dangerous storm, Tanner Beam is already hot on its trail. The MU atmospheric science student has been chasing extreme weather since he was 15.

Each month, Vox curates a list of can’t miss shops, eats, reads and experiences. We find the new, trending or underrated to help you enjoy the best our city has to offer.

BY TONY MADDEN

BY TONY MADDEN

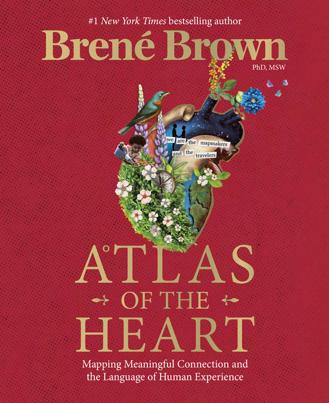

At Main Squeeze’s weekly Woman-Owned Wednesday event. The event seeks to promote collaboration among women business owners in Columbia rather than fostering competition. Main Squeeze, every Wednesday in December, 4–7 p.m.

At one of Columbia’s Magic Trees, which light the city every holiday season. The city’s first Magic Tree, at the Village of Cherry Hill, celebrates its 26th year. The Village of Cherry Hill, corner of Scott Boulevard and Chapel Hill Road; The Crossing, 3615 Southland Drive; Downtown, Ninth Street and Broadway.

Wine and eat cheese with some furry friends at Papa’s Cat Café’s Wine & Whiskers event. A reservation includes cheese, two glasses of wine, a fruit and veggie tray, baked goods and adult coloring pages. For $5 extra, you can paint your own wine glass. Papa’s Cat Café, Dec. 17, 5:30 p.m, papascatcafe.com/reservations; $20

Bestselling author Brené Brown’s new book Atlas of the Heart and watch her virtual presentation hosted by Skylark Bookshop. Pulitzer Prizewinning journalist Tony Messenger will discuss his new book Profit and Punishment: How America Criminalizes the Poor in the Name of Justice at an in-person event at Skylark. Brené Brown, Dec. 2, 7–8 p.m., online, register at skylarkbooks.com/events, $32–37; Tony Messenger, Skylark Bookshop, Dec. 9, 6:30–8 p.m., free

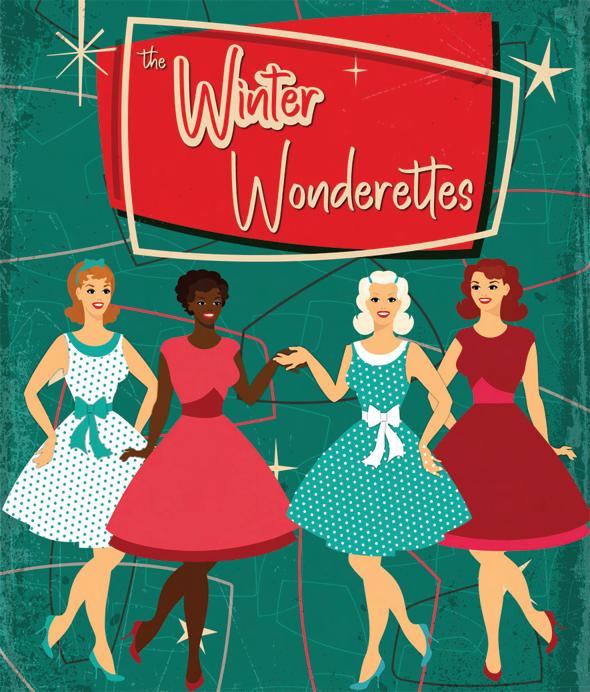

To singer and playwright Lisa Rock keep the Carpenter family’s holiday traditions alive in A Carpenters Christmas. Rock and her six-piece band will honor the Carpenters’ performances from their two holiday albums and Christmas variety shows. Missouri Theatre, Dec. 7, 7 p.m., concertseries.missouri.edu; $25-35

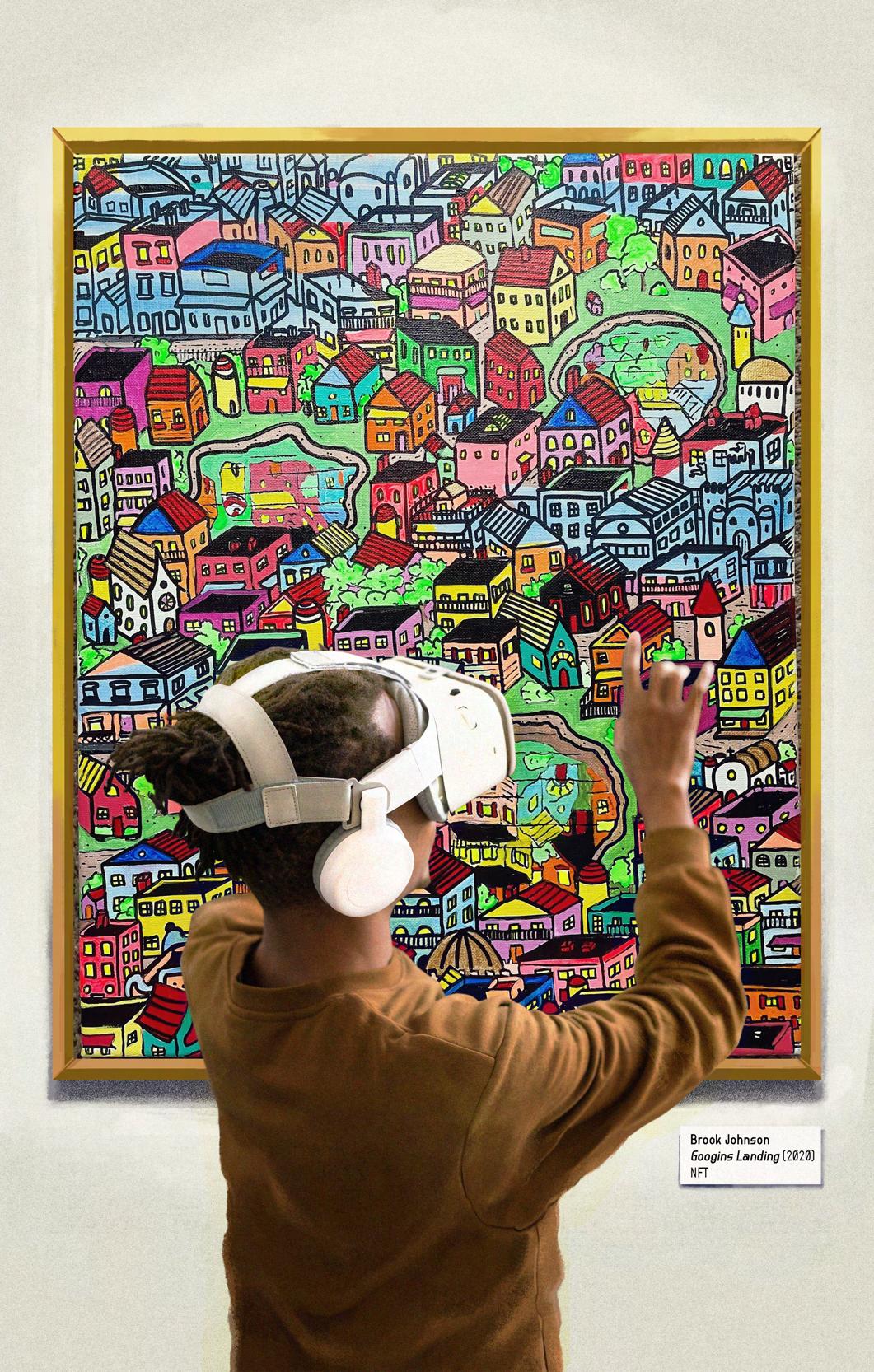

With a couple clicks and a search engine, anyone can download a digital copy of a famous painting. But it’s not authorized. By comparison, NFTs, short for non-fungible (not replaceable or interchangeable) tokens, allow art connoisseurs to collect and keep digital art in ways that support the artist who created them.

An NFT is a digital asset of a photo, meme, painting or other multimedia piece with an identifying code that someone can purchase. This code, made possible by blockchain technology, is what makes an NFT different from a digital copy of a piece of art. It’s like a signed Michael Jordan basketball card. It’s one of a kind, it can’t be traded for just any card, and it makes you proud knowing that you’ve got one.

Although NFTs originated in the early 2010s, they increased in popularity in 2021 after more companies, artists and celebrities began to create and sell them using cryptocurrency.

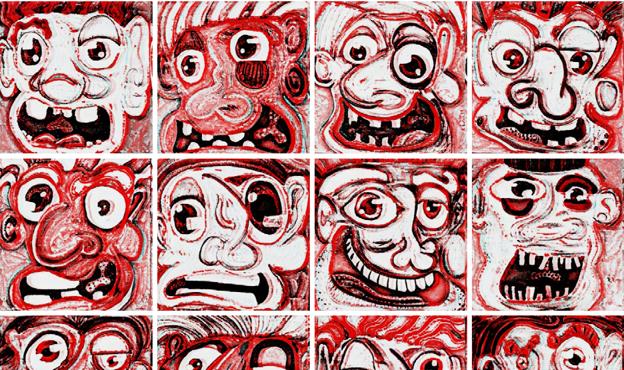

Two Columbia-based artists are among those getting in on the trend: Brock Johnson and Stephen Evans. Johnson got his start with NFTs after hearing about them from a friend, and he began creating them in August. So far, he has made five.

“I think there’s also a little bit of bragging rights in there,” Johnson says, explaining that NFTs present an opportunity to own a rare artifact.

Evans, another local artist, has made 41 NFTs. He digitizes some of his original art and has a series of NFTs based on nursery rhymes and fairy tales because

NFTs are flooding the digital market and providing new outlets for expression.Someone might buy an NFT for their collection or to display it in a virtual space, artist Brock Johson says.

he writes and illustrates children’s books.

“It’s just a different way to share my story,” Evans says. He predicts NFTs will become more ubiquitous as a signifier of social status or even a form of currency itself. “You know there’s a buyer for everything,” Evans says. “If you’re willing to do the work, someone’s willing to pay for it.”

For Evans, creating and selling NFTs is a way for artists like himself to personalize their involvement with their customers. It gives them a virtual platform to reach a wider audience rather than confining viewers to the physical bounds of a gallery show. Without those limitations, NFT artists can work with and communicate more directly with their patrons.

Johnson says people buy NFTs for various reasons: to flip them for a profit, keep them as part of a personal collection or display them in digital spaces, for example, on the wall of a virtual home as part of an immersive game. NFTs are making waves in the art world by opening up new possibilities for how people can consume and collect art.

This portion of The Faces of Steve (2021) is part of Stephen Evan’s collection of NFTs that depict expressions and characteristics.

Find these artists online: Brock Johnson, @fatknee13, is on Instagram and Twitter, or Stephen Evans on Instagram @malidivianstephen or at Artlandish Gallery on Wednesday afternoons.

In March, a mosaic of NFTs titled Everydays: The First 5000 Days by digital illustrator Mike Winkelmann, or Beeple, sold for more than $69 million. The sale made Winkelmann the third-highest-selling living artist, according to The New Yorker. Companies are commercializing NFTs. For example, NASDAQ reported that Funko, a brand known for its figures and pop culture products, plans to develop NFTs and put them on TokenHead, an app and website designed for NFTs. Despite the technological advancement NFTs provide, the environmental impact might not be worth it. Generating NFTs requires significant computer processing, which means that each NFT carries a large

carbon footprint. The New York Times reported that Ethereum, a software platform used to develop NFTs, uses almost the same amount of energy per year as Hungary.

Johnson and Evans both say they were not fully aware of NFTs’ effect on the planet, but they want to learn. “I’m sure when this is figured out, everybody will jump on board,” Johnson says. “I don’t want to be environmentally destructive.”

NFTs provide new ways for art to proliferate in digital contexts by creating accessible outlets for self-expression and changing the way we regard art ownership. With this uncharted territory, however, come potential risks to the planet that we’re still learning about.

The winter holiday illuminates the heritage of the Black community.

BY CELA MIGANKwanzaa is a cultural celebration with roots in the ’60s that knits together the Black community. Kwanzaa traditions include singing, dancing, poetry reading, African drumming, gift giving and feasting.

Community activist Nia Imani credits herself with bringing Kwanzaa celebrations to Columbia nearly 40 years ago as a way to focus on Black history and culture in mid-Missouri.

Held Dec. 26 to Jan. 1 each winter, the holiday allows people to reflect on the past year.

“I think that this time is the best time for Kwanzaa because it helps you to pull together everything that you’ve done in that past year,” Imani says. “You examine it, and you see what has been good and what has not.”

Kwanzaa was founded by Maulana Karenga, a Black nationalist, in 1966 to keep Black culture alive. He modeled the holiday after traditional African harvest festivals and named the holiday using a Swahili phrase matunda ya kwanza, meaning “first fruits.”

Kwanzaa centers around seven principles: unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, collective economics, purpose, creativity and faith. Each principle marks a value in African culture. Seven candles are used to symbolize the principles and are placed in a candle holder called the kinara. A candle is lit every day during Kwanzaa, and the seventh day typically culminates in a feast.

Mataka Askari, a certified peer support specialist at Burrell Behavioral Health, says the principles aren’t unique to Kwanzaa alone. “When you strip away all the cultural additives and you get to the root core principles, you’ll find that these principles of Kwanzaa run parallel through all systems of spiritual cultivation or religions,” Askari says.

Many members of the Black community say they recognize and use the values of Kwanzaa even if they don’t celebrate the holiday.

Fontella Henry, co-owner of Big Daddy’s BBQ, focuses on self-determination in her own life. She says she doesn’t celebrate Kwanzaa but strives to embody this principle. “We don’t do a lot of the creative celebrating and we

Nia Imani addresses a crowd at Progressive Missionary Baptist Church’s annual Kwanzaa Celebration in December 2017. Imani spoke about the significant symbols of Kwanzaa, which include the kinara, or a candle holder, that houses the seven candles that represent the seven principles of the holiday.

just on (the) daily try to live that and know our purpose,” Henry says.

A personalized holiday

Kwanzaa has rituals and traditions that are different for every community member.

Part of Imani’s Kwanzaa celebration entails physically and spiritually clearing out the old. This allows her to look back on the year and evaluate what went right and what could have gone better.

Imani says the growing commercialism of Kwanzaa celebrations makes items more accessible but takes away the creativity of making homemade items, such as the kinara or a scrapbook.

Nonetheless, the most important part of Kwanzaa for Imani isn’t necessarily celebrating publicly but rather getting the word out about Kwanzaa and celebrating with close family.

Kwanzaa in Columbia

In the Columbia community, Kwanzaa celebrations vary from those put on by the city and churches to festivities at home with loved ones.

Progressive Missionary Baptist Church hosts an event where people can learn about and celebrate Kwanzaa. There’s music, dancing, storytelling and candle lighting.

The Columbia Parks and Recreation Department hosts candle-lighting ceremonies, a city Kwanzaa celebration and a Black-owned business expo. Last year due to the pandemic, it gave away free Kwanzaa celebration bags with instructions and supplies for rituals, according to the Missourian

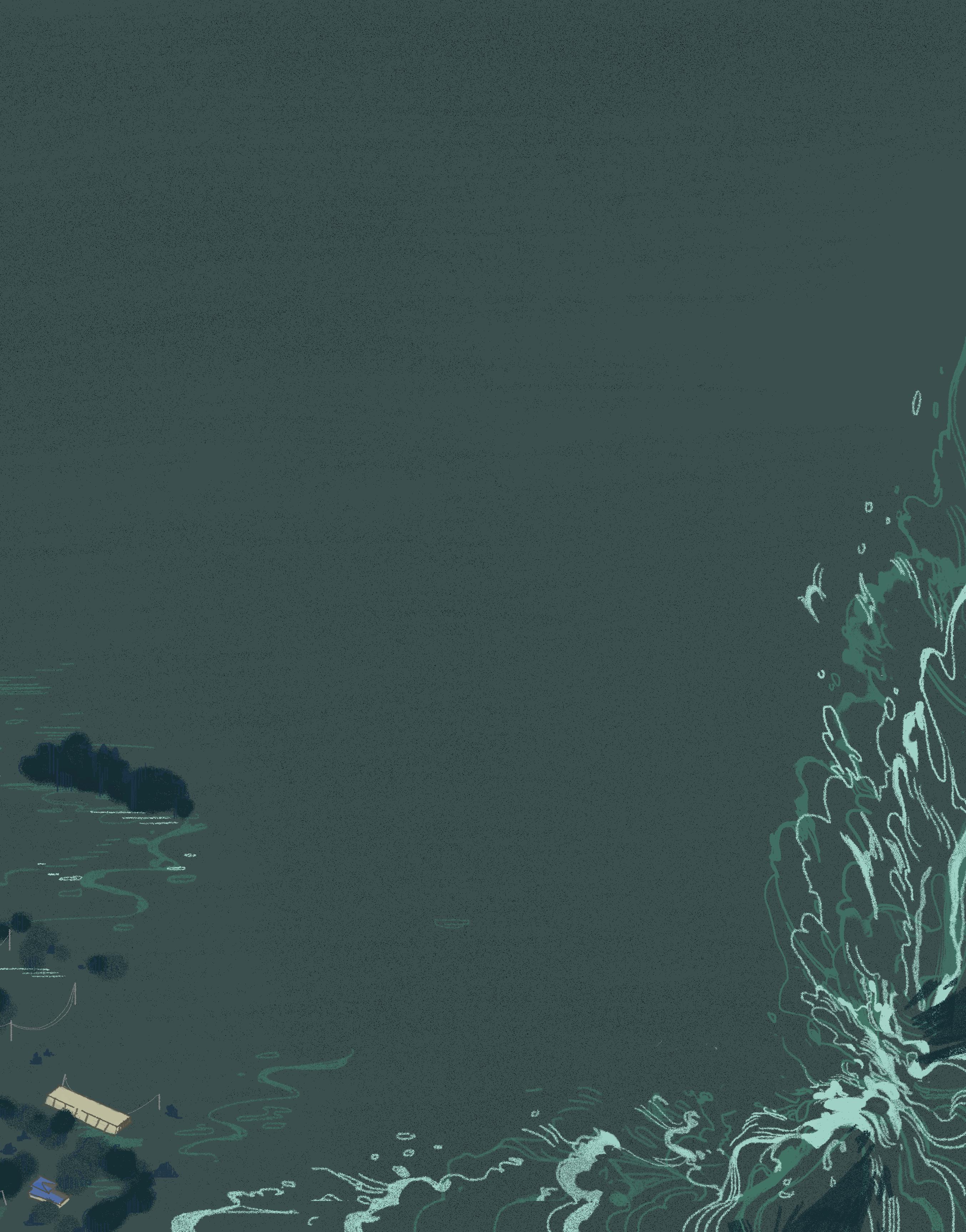

A storm here, a flood or two there — bad weather in Missouri is expected, and scientists agree that climate change will make these extreme weather events much more frequent. Missouri’s disasters aren’t wildfires or hurricanes but rather ice storms and floods, which are just as damaging. And our approach to rebuilding as a community, often rooted in idealism, will only take us so far. Vox examines the layers of inequality that rise to the surface in the aftermath of natural disasters.

BY MOY ZHONG

BY KATELYNN MCILWAIN AND ANNELEEN OPHOFF

BY MOY ZHONG

BY KATELYNN MCILWAIN AND ANNELEEN OPHOFF

Agreen glow illuminated the skies over the state capital and colored everything it touched with an eerie hue. The light bathed the white walls of the Missouri State Capitol building on that evening in 2019. Next to it, the Missouri River reflected a growing set of clouds, distorted by an increasing amount of ripples and waves. The wind howled and announced a night for the history books.

11:30 p.m., May 22, 2019, Jefferson City

Less than a mile south of the Capitol, Akisha Pinnell-Walls was nervously pacing when the door blew open at her rental home on Jackson Street. “I knew something bad was going to happen,” she says. Pinnell-Walls was 35 weeks pregnant with twins and had been experiencing some contractions that evening. The TV was off, phones were put away for the night, and weather updates didn’t reach them. That’s when the tornado hit.

“Suddenly, my ears started popping, (my husband) Reginald made a crazy face, and I just said, ‘We’ve got to go,’” Pinnell-Walls says. While she rushed down the basement stairs to safety, her husband ran through the house to get their 11-monthold, Reggie. Thankfully her three teenagers weren’t at home that night. “As soon as I hit the middle part of the stairs, I heard a sound like a bomb had gone off,” she says. She threw herself behind a brick wall and landed on her belly, which caused her contractions to become severe — five weeks early.

As the tornado passed over the house, the basement was plunged into darkness. Upstairs, the living room was full of shattered glass, the roof over the porch had disappeared, and a runaway boat obstructed the yard. To this day, Pinnell-Walls still doesn’t know where the boat came from.

Before the tornado ravaged their home, Pinnell-Walls was anxious about the telltale signs of a severe storm. She’d learned in high school classes about natural disasters and shared her concerns with her husband. His response?

“There are no tornadoes in Jefferson City.”

The EF-3 tornado that swept through the city that night injured 33 people and damaged 516 residential buildings, 30 government buildings and 82 commercial buildings. Pinnell-Walls says her husband’s doubts reflect a popular belief that the hilly landscape of the city would protect it from tornadoes. There’s also the belief that an event that traumatic is too unlikely to happen to them and too far-fetched to be the new normal.

Experts, however, say otherwise.

Extreme weather, worsened by climate change, is hitting Missouri with an uppercut. The landlocked heartland of the country is presumably safe from the attention-grabbing tropical storms on the coasts and the annual round of forest fires out West. However, warming temperatures are increasing the severity of weather events including storms and flooding in mid-Missouri, says Robert E. Criss, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

In fact, 98% of Missouri’s counties have issued disaster declarations since 2015, according to the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, a Washington-based organization that works with donors and aid groups to assist in emergencies. But when those storms and flash floods happen, government relief organizations such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency don’t necessarily swoop to the rescue.

A low-attention disaster is one that doesn’t receive a FEMA individual assistance declaration. Without media coverage, these disasters cause damage that remains unseen outside the community. And a lack of recognition comes with a lack of incoming money to help. In this package, Vox explores the climate change contributing to the frequency of these disasters, a town forever gone because of flooding, the struggles for assistance and how daily lives have been changed.

“If the scale of a disaster is too small, FEMA doesn’t offer household grants to recover any property losses,” says Cari Cullen, director of the Midwest Early Recovery Fund, a project of the Center for Disaster Philanthropy. “More and more disasters fall into a category where FEMA does not have the capacity, the time or the resources to actually intervene. And when there’s limited media coverage, there’s less money coming from elsewhere. In the end, there are insufficient community resources to meet the needs of everybody.”

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy has a phrase for these incidents: low-attention disasters. Communities that experience low-attention disasters have a harder time accessing recovery resources and making sure the whole community can bounce back.

Because of structural inequalities in the U.S., disasters like these exacerbate existing stress points in low-income communities along the lines of class and race. “Many communities have, historically, not received the same investment in their communities,” Cullen says. Because of a lack of access to affordable housing, people live in rentals or mobile homes too fragile to weather a storm. Other houses have

depreciated in value so much that someone outside of a community might not see the importance of rebuilding it.

Job insecurity can throw a sucker punch, too. “Hourly workers can’t put their job on pause for a few days and figure out what to do next,” Cullen says. Single parents disproportionately feel that pressure. “They struggle twice as hard to generate the income necessary to pay for recovery.” And a history of discrimination has eroded the trust of immigrants, who often have trouble accessing information and resources. The intersecting vulnerabilities create obstacles for marginalized groups. “Low-income areas and Black and Indigenous people really are on the frontline of climate change,” Cullen says.

Studies from the University of British Columbia, Rice University and the University of Colorado show that even when FEMA assists communities, white disaster victims receive more financial aid than people of color, even when the damage is similar. Not only do white individuals generally receive more support from the federal agency, so do the neighborhoods they live in.

Structural inequalities and disasters fueled by climate change provide a deadly mix of realities that leave many Missourians exposed. Without federal agencies in your corner and as climate change worsens, the disasters will continue in frequency and severity, one blow after another.

Some who’ve fallen victim to extreme weather events don’t use the term “disaster” to characterize experiences they’ve come to know as routine. When living in a country that demands constant productivity, people are forced to roll with the punches. It’s the heart of American idealism: Work hard, pull yourself up by your bootstraps, and move forward. Missouri riverfront communities, a population increasingly vulnerable to flooding, are an example of communities who have come to expect disasters. Hartsburg is one such community, a small agricultural village 22 miles south of Columbia. Situated on the banks of the Missouri River and Hart Creek, its residents are accustomed to summer flooding.

The best known disaster to hit the town was the Great Flood of 1993. Water levels rose as high as living room ceiling fans and the rampaging river blasted several openings in the levees around the community.

But beyond this historic event, cleaning up after a flood is a way of life for the town’s residents, including Jason Thomas, who was 10 in ’93. He remembers churches and local groups, such as Hartsburg American Legion and Hartsburg Lions Club, coming in with supplies to clean homes and rebuild. Today, disaster responses continue to be community-centric.

Soybean fields surround a dilapidated country road that was destroyed during the Great Flood. Bill Molendorp, mayor of Hartsburg, recalled the farm houses that used to be there before the flood.

Bill Molendorp, the mayor of Hartsburg, has lived there for 31 years and has experienced numerous floods. “I know there’s a flood coming before any weather updates,” he says. “I’d see the farmers bringing their equipment, piece by piece, to higher grounds when they feel it coming. It’s such a sinking feeling.”

Molendorp says floodwaters have picked up houses and left sand strewn across farmland. Some of the floods have scoured gaping holes as deep as 70 feet across the farmland.

In 2019, hundreds of volunteers helped residents stack thousands of sandbags to protect the 250-year-old town from the rising floodwaters. About half of Hartsburg’s land is protected by three staggered layers of levees that minimize floodwater damage to 3,500 acres of land in southern Boone County. Some homes, though, are left unprotected.

Even so, government aid isn’t necessarily the go-to for the residents, who can trace their lineage back to the first German immigrants who settled there. “They’ve known the land since forever, and because of that experience, we can take care of it better,” Molendorp says. He prefers not to go through the cumbersome red tape associated with FEMA and wants instead to do what he knows best to take care of his home. Like most houses in the area, his is now built off the ground, and he keeps his living space on the second floor.

“Flooding in Hartsburg is always a concern,” Thomas says, describing how the community knits together to “look after their neighbors and family and friends” and to mitigate the effects of disasters. “You never know what Mother Nature is going to do. You can only fight what you can and fix what we got at the end of it.”

Seven feet under Chad Coy led his employees in restoring their facility after significant flooding

June 25 brought 7 feet of water into the Missouri Athletic Center on Forum Boulevard. Three days later, the operation was up and running again. Coy, the director of the center’s Parisi Speed School, and the rest of the staff spent 12 hours cleaning up what they could of the flood’s wreckage. “We didn’t miss a beat,” Coy says. “You’ve got two options: quit or push forward. And for us, quitting is not an option.”

The Great Flood April–October 1993

Missouri and Mississippi rivers

The flood threatened the Missouri Capitol and caused the deaths of 50 people along with $15 billion in damages.

Central Plains ice storm

Jan. 29–31, 2002

Central U.S.

This storm affected 78 counties across Kansas and Missouri, the hardest hit states, and resulted in over 1 million people

An informational display titled Neighbors helping Neighbors, placed along the portion of the Katy Trail running through Hartsburg, details major floods that have hit the town between 1903 and 1995. From a restaurant owner serving food while standing in the floodwaters to group meals in the firehouse, community support runs deep. It’s human nature.

“Disaster begins and ends locally,” Cullen says. “I would say that your first call isn’t FEMA or the government but those places where you already have a network and connection: your friends, family, church or neighborhood organizations.”

Not everyone enjoys the same resources and cohesion after a disaster, though. It’s common and admirable, even, to be able to count on the philanthropic efforts of local churches and volunteers to rebuild after destruction. But at what point will the floods and tornadoes be too much for even the most tight-knit communities?

“They continue that cycle down into a persistent, chronic, and ongoing poverty along our river beds,” Cullen says. “I fear that disasters will increase in intensity and scale faster than we can manage. More and more communities will then be left completely on their own to recover. And they will not recover.”

Tornado outbreak sequence

May 29–30, 2004

Central and southern U.S.

An F4 tornado swept through Weatherby, Missouri, and caused at least three deaths, six injuries and $5 million in

Historic ice storm

Jan.12–14, 2007

Southwest Missouri

The ice storm, which caused the greatest power outages for Missourians since December 1987, caused more than 200,000 people in southwest

Since 1990, there have been 53 federal disaster declarations in Missouri. The largest category is severe storms followed by floods.

Three hours after the tornado swept through her home, Pinnell-Walls went into labor. Outside, the streets were littered with fallen trees and power lines. Driving their damaged Pontiac G6 past debris, off the road and around potholes, the couple finally made it to the emergency room, only to find that the power had been down and the hospital was relying on a backup generator.

Knowing that the family’s living situation had drastically changed in a matter of hours, the doctor medically delayed the birth of their twins. “She knew I had to handle my business first,” Pinnell-Walls says. In the upcoming days, churches and charities gathered around the family, replaced their lost items and provided emotional support. “There was nothing more that I could ask for,” Pinnell-Wall says.

Except for a place to live. For weeks, the family stayed at a hotel paid for by charities and locals.

Winter storm

December 2007

Boone County and 40 other counties

Heavy rain, sleet, snow and ice caused four people to die and more than 170,000 homes to lose power.

After the Great Flood, Hartsburg turned former residential properties into green spaces and community parks including this art

But finding a long-term solution proved difficult. “The prices skyrocketed after the tornado,” Pinnell-Walls says. “And nobody wanted to rent to families with children.”

Eventually they moved into a two-bedroom apartment that had a door frame infested with cockroaches. Although it provided a roof over their heads, the family had to split up because there wasn’t enough space. Pinnell-Wall’s teenage children lived at their dad’s for nearly two years.

“Seeing my kids being separated was horrible,” she says. “I felt broken as a mother.”

The family received funding from FEMA to rent temporary housing, but in hindsight, most of the help came from charities, often churches. “I had never even been to those churches,” Pinnell-Walls says. “It’s just what was in their heart to do.”

Still, Pinnell-Walls says she doesn’t feel frustrated with local or state representatives. “It was

Eleanor McCrary had never worried about flooding damage until her belongings were ruined

McCrary’s storage unit, at StorageMart, was next to Bear Creek, and the water had seeped into hundreds of dollars worth of her belongings. All of the ruined furniture and items had to stay in the unit until McCrary’s insurance claim came through. She wasn’t expecting flooding to affect her, having associated it with only coastal states. The lesson McCrary learned from the experience was to “do her own research” and be cautious about what risks could be encountered in different locations before choosing a place to keep possessions.

Groundhog Day blizzard

Jan. 31–Feb. 2, 2011

U.S. and Canada

Heavy snowfall from Kansas City to St. Louis led to the closing of I-70, the first blizzard warning in Columbia’s history, a three-day closure of MU and a record 23 inches of snow for Warrensburg.

F5 tornado

May 22, 2011

Joplin

The .75-mile-wide tornado led to the deaths of more than 150 people and heavily damaged or destroyed over 5,000 structures.

Flooding

April 29, 2017

South and central Missouri

Parts of Missouri were flooded with 10 to 12 inches of water during this historic flooding that resulted in 93 evacuations, 33 rescues and more than 1,200 heavily damaged or destroyed homes.

Flooding

June 24, 2021

Boone County and 20 other counties

Severe storms, winds and tornadoes led to power outages, water rescues, damage to homes and powerlines and made some state roads unusable.

installation near the Hartsburg Baptist Church.

To qualify for FEMA funding after a natural disaster, regional authorities follow a federal declaration process.

Step 1: State of emergency declaration

The governor issues an executive order declaring an emergency to help the state mobilize resources and state agencies to the region.

Step 2: Local damage assessment

County officials survey and assess the degree of damage and estimate cost of recovery.

Step 3: Joint damage assessment County officials request an assessment from local, state and federal officers.

Step 4: Requesting a federal major disaster declaration

The governor can submit a request if the combined damage assessment exceeds the state threshold.

Step 5: FEMA review

After a review, FEMA submits a recommendation to its headquarters and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Step 6: Presidential determination

If the president decides the disaster merits a federal disaster declaration, FEMA gives financial assistance.

Communities have to meet multiple criteria to qualify for government funding. When they don’t, donations and volunteer organizations are left to fill the gaps.

BY RASHI SHRIVASTAVAWashed over by heavy downpours and starved for financial help, small, overlooked communities are at the epicenter of low-attention disasters.

“Economically, many folks are literally hanging on by a thread,” says JoAnn Woody, external relations program manager at the American Red Cross. “It just takes one small emergency to put them over the edge.”

Missouri is brimming with low-attention disasters that receive little to no financial assistance from federal and state government agencies, which prioritize aid distribution following large scale disasters. This leaves volunteer organizations to do the heavy lifting of rebuilding communities when they don’t qualify for government assistance.

Woody remembers the day after the Joplin tornado, which destroyed one-third of the city. On one street, she passed stone houses built in the ’40s and ’50s — their stones smooth and polished — and noticed that the houses were tilted. “The only word I can come up with is, it’s violent,” she remembered telling her friend on the phone.

The Joplin tornado was the costliest tornado in modern U.S. history, causing more than $3 billion in damage. But what about the tornado that damaged 150 homes in Dexter in July or the damaging winds that sounded like a freight train in Perry in the same month?

Mike Cappannari, external affairs director for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, says unless there is a presidential declaration of disaster, the agency does not provide any financial assistance to the affected communities.

In Missouri, the ball then falls into the court of the State Emergency Management Agency, which doesn’t have a dedicated budget for disaster relief. The state provides assistance through the Missouri Emergency Human Services, but it does not operate in a vacuum. It partners with other state health agencies, volunteer organizations and faith-based organizations.

Financial responsibility falls to nonprofits and local government agencies after federal and state

assistance is given or the disaster doesn’t qualify for the assistance.

Susan Lutton, the executive director of a free legal program for low-income individuals at Mid-Missouri Legal Services, says most legal issues that surface after a disaster are related to housing. After the tornadoes that touched down in Miller County in 2019, the program helped hundreds of families, she says. “We only have two housing law attorneys and frankly, they’re just overwhelmed,” Lutton says.

This trickle-down effect of funding has created inequities and forced volunteer organizations to find creative ways to rebuild communities.

Gaylon Moss, the disaster relief director at the Missouri Baptist Convention, made up of 2,000 churches, says it relies on an average of $50,000 of annual donations to help pay for recovery actions including cleanup. “The volunteers and their work bring the most value to disaster recovery,” he says.

“Disasters don’t discriminate; they hit any community, any place,” Moss says. Recovery, however, is not so equitable. Undocumented individuals for instance, do not qualify for FEMA assistance and are hesitant to interact with government entities.

Some communities have unique challenges while recovering from a natural disaster. When Mark Twain National Forest, a region with rural and poor communities, flooded and qualified for FEMA assistance in 2017, the agency was unable to provide assistance to people without proof of home ownership. “A lot of homes that had passed down over the years from family members, they’ve just lost track of paperwork and didn’t have a deed,” Cappannari says. This prompted FEMA to be flexible about acceptable documents to prove property ownership.

Despite the myriad of nonprofits stepping in to fill the gaps, there’s only so much they can do.

“It can be frustrating,” Woody says. “We all do this because we’re humanitarians — we want to be able to fix things, and we can’t fix it as one organization.”

Aid eligibility by county

No designation

Public assistance

Individual assistance

Individual and public assistance

Total public assistance distributed: $81,719,366

Sources: Michael Cappannari, external affairs director, FEMA Region 7 and www.fema.gov/disaster/4451

Total individual assistance distributed: $7,477,718.54 21

Map courtesy of Free Vector Maps

Water system expert Robert E. Criss wades into the consequences and solutions to climate-fueled disasters.

BY JULIAN NAZARAfter studying water-related environmental problems for over three decades, Robert E. Criss says most of the problems and damages associated with climate change in Missouri are avoidable.

Criss, professor emeritus of earth and planetary sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, specializes in hydrogeology, the geology of water and its systems. Drawing on his vast knowledge of Missouri hydrogeology, he has offered solutions to local environmental problems, such as flooding, landfill problems and groundwater contamination, at public hearings in the St. Louis area.

Vox sat down with Criss to discuss climate-related flash flooding in Missouri and how human decisions exacerbate the problem.

How do human actions impact climate change and the planet’s weather?

Climate change and other human effects change the nature of Earth’s surface, and the way we’re interfering with the hydrologic (water) cycle is making things hotter. An example of this is strip mining in certain parts of the world. We are throwing waste into creeks. Also, many rivers in the world run dry because we pump them out. These actions cause gross changes to the surface of the Earth.

Climate change is probably making more intense storms. Heat stroke and heat exhaustion are the biggest weather-related killers. This is followed by tornadoes and flooding. They’re all getting worse. As the temperature goes up, all these things follow hand in hand.

How will climate change affect Missouri residents in the future?

We’re a flood state and a tornado state. It’s one of the most hard-hit places, especially for having such a low population. We have plenty of damages and fatalities.

Climate change will bring higher temperatures and more intense rainfall. The more intense rainfall brings on flash flooding, which is the biggest cause of deaths. Flash floods come suddenly. They come and go in a single day often. They catch people by surprise. They’re what really kills people.

It’s particularly getting amplified, especially in Missouri, because we continue to build stuff in the wrong place. Putting stuff along creeks and flood plains, that’s just asking for trouble.

What are some common misconceptions about climate change?

Inappropriate land use also has a lot to do with climate change. I think people don’t see the benefits of forests or parks. Those things will help ameliorate climate change. I think the fixation on CO2 alone for driving climate change is incorrect. People aren’t thinking enough about jets.

So many of these problems are fundamentally driven by population growth in the world. If we don’t limit population growth, our standard of living will continue to go down. There will be fights over water. Disease will run rampant. We are not going to solve these problems by fighting all the symptoms.

What should be done to combat the effects of climate change?

We can plant more trees. We can promote greener energy sources. The main thing we need to do is rethink how we get along with the planet. We shouldn’t be so cavalier with the way we use the land. It doesn’t make sense to build a commercial operation in a flood plain. You’re not only putting people and infrastructure and merchandise in harm’s way, but you’re also destroying the best cropland in the world.

At the same time, we’re destroying the valuable groundwater resources beneath the land. The goal of our future, in a world with a growing population, is going to be good farmland and water. Why would we destroy those things just to build a store in the wrong place?

How can Missouri’s leaders respond to climate-related disasters?

They should be more supportive of green energy and recycling efforts. They should be far more supportive of zoning regulations that keep buildings out of flood plains. We are a big coal-burning state, which is extremely destructive to land, vegetation, soil and groundwater systems. We ought to be a little more progressive. It’s going to hurt us in the long run if we’re not. Thoughtful people won’t want to live here.

“(God’s) always with us, regardless of how dark our days may seem.”

— Debra Robinson

Authors Elaine Lawless and Todd Lawrence co-produced the documentary Taking Pinhook in addition to writing a book about the town’s flooding.

Authors Elaine Lawless and Todd Lawrence co-produced the documentary Taking Pinhook in addition to writing a book about the town’s flooding.

Meet the everyday musicians of the Columbia Civic Orchestra, a nonprofit volunteer group that makes music for the people.

EEvery Thursday at 7:30 p.m., 40 to 50 musicians gather in a room in the Sinquefield Music Center. Muffled conversations come first as the players take their seats and unpack their instruments. Snippets of melody follow, quiet and disarranged, as each musician warms up.

The orchestra’s conductor, Barry Ford, observes the scene. Then he steps forward and swishes his baton. Silence ensues. “We have not much to talk about,” Ford says. “Let’s play.”

Woodwinds lead the orchestra into the first movement. Violins join, and “The Moldau” by Czech composer Bed ř ich Smetana swells to the point of creating goosebumps. The Columbia Civic Orchestra is rehearsing for its first live performance since February 2020, which happened Nov. 6. There will be another Dec. 11.

The origins of the orchestra have become mythological. Its founding conductor, Anthony Addison, moved to Columbia in the early ’90s,

saw that ordinary people were rarely invited to perform with professionals and decided to change that. The Columbia Civic Orchestra, or CCO, is a group where professionals and amateurs play together — for free and for their own enjoyment.

CCO’s current music director, Stefan Freund, shares Addison’s original vision. “We are open to having anyone who wants to give music a try,” he says. “We have doctors, lawyers, accountants, students, professors — a body that really is reflective of the Columbia community.”

Freund has been at the helm of the orchestra since 2004, but an arm injury prevents him from conducting this season. Maestro Barry Ford is filling his place. Agile and upbeat, Ford conducts with his whole body, the tone of his voice and even the direction of his toes. “I will let you hit the drum,” he says, joking with the percussionists during rehearsal. “I am that conductor.” Minutes after, he celebrates a particularly successful section with a jump and a midair turn.

Closest to him playing the violin sits Sally Swanson, 71. Whenever she talks about music, she becomes strikingly expressive. Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A major transports her to her childhood living room in Winfield, Kansas, where her father, a clarinetist, gave lessons. Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony feels like “watching people riding horses through a big meadow,” she says.

Swanson admits she cried while performing it at the Missouri Theatre.

“I got all teary eyed; I could hardly see the music,” she says. “Because it dawned on me that at my age, I may never play that piece again.”

Playing the violin was not exactly what Swanson wanted. Her heart belonged to per-

cussion, but her parents and her school’s band director steered her toward violin lessons. She performed in high school and college but didn’t major in music. Instead, she studied architecture. She hung wallpaper professionally and owned a soccer gear store on Business Loop.

For Swanson, joining CCO meant returning to performing in an orchestra. It also reminded her how tightknit a musical community could be. “Everyone is very kind to each other,” she says.“We don’t even try out for where we sit. We sit in the section where we’re comfortable and nobody questions that.”

The comfort of a group is what enticed Nick Shapiro, 58, to join the orchestra. Upon moving to Columbia from Chicago, he was looking for ways to get involved with the community. He also didn’t mind a reason to resume playing cello, which he hadn’t done since college.

“I did not know what to expect,” Shapiro says. Back in 1998, when he first met Addison after signing up, Shapiro was well out of practice. He feared an orchestra that was willing to accept him would not be that good.

But CCO proved Shapiro wrong. The musicians were passionate, Addison and his successors were driven, and the quality of performances only grew over the years. What’s more, CCO turned into an integral part of the community. “It now has a history,” Shapiro says. “Years give it stability, a foundation that pretty much ensures that we keep going on.”

On a more personal level, CCO supports Shapiro’s professional priorities. As a young musician, he swapped the piano for a string instrument to perform with a group. Later, he grew busy working in real estate and raising a family.

“But I’ve always enjoyed music,” Shapiro says. “And the orchestra is a great way to be with people, producing something that is really, really rewarding.”

Valentina Arango, 25, has loved meeting new people and sharing her musical passion since

arriving in Columbia to pursue a master’s degree in flute performance. She fell in love with the instrument at a music school in her hometown of Medellín, Colombia. At 15, she met Alice K. Dade, an MU flute professor who was teaching at a musical festival in Medellín.

“I really liked how she was handling everything,” Arango says. She knew she wanted to learn more from Dade. Arango kept in touch with her on Facebook, asking Dade for advice before performances or sending her videos to listen to. In August, she finally arrived at MU to study under Dade’s mentorship.

Mere months later, a friend convinced Arango to join CCO and play the piccolo, a woodwind instrument related to the flute. At first, Arango was scared. “I played shrilly because the piccolo is high-pitched, and I

didn’t want to bother anyone,” she says. “But the maestro (Barry Ford) said I can play how I want to play, and it is really nice.”

Their time at MU encouraged oboist Lauren Beran, 23, and trumpeter Zach Beran, 27, to join CCO and brought them together as a couple, too.

“Someone tapped me on the shoulder,” Beran says, recalling the “abridged version” of their meeting after a wind ensemble concert. “I didn’t know who this redhead girl was.” They saw each other again, played in the university orchestra together, and the rest, both say, is history.

This season, the newlyweds will be performing together again. Both say they find playing at the community level refreshing.

“With students, you get the level of playing, but then you don’t have the experience,” Beran says. With CCO, it’s the opposite. “Comparing the two, I would always take experience over skill.”

For Lauren Hynes, now Beran, an English

teacher at Hickman High School, it is a chance to keep practicing. “You’re not being graded or yelled at by the maestro if you do something wrong,” she says. “People just come together because they enjoy making music.” The only problem, she says, is that CCO doesn’t always have enough people.

Swanson might know why: It is often hard to convince amateurs that they are good enough to play in an orchestra. “If you don’t have self-confidence, it’s a good place to start, because we will support you and help you,” Swanson says. “But you’re going to have to stick with it, too. There are times when you’ll think you will never be able to play this section or even know what the hell is going on.”

But after practicing at home and rehearsing, musicians will get it, Swanson says. They always do, and she has the orchestra experience to know it.

How can you find fresh seafood in Columbia? Catch the fare at Cajun Crab House Seafood Market.

BY CHASE MEILI

BY CHASE MEILI

In northwest Columbia near Cosmopolitan Park, a bright-blue building sits alongside a busy roundabout. This is the storefront of Cajun Crab House Seafood Market, which has a reputation for selling fresh, wild-caught seafood in mid-Missouri. A few blocks east of the market on Business Loop 70 West lies the Cajun Crab House Restaurant, which serves the catch — boiled or fried.

Columbia sits about 760 miles away from the Gulf of Mexico, a 12-hour roadtrip, and yet Kevin Dinh, the founder and part-owner of the market and restaurant, has made it possible for fresh seafood to be served to customers in a landlocked state.

Dinh has been distributing seafood to Kansas City and St. Louis since 2014

and founded the restaurant in Columbia in 2018. His Mississippi Crab Company owns a fleet of refrigerated vans and delivers loads of seafood from Biloxi, Mississippi, to Columbia multiple times per week. These deliveries allow Columbia residents to buy fresh snow and Dungeness crab and shrimp, among other fare.

CCH market and CCH restaurant only sell fish caught in the Gulf of Mexico, compared to the mass-produced fish sold at many local grocery stores. Inland states often use fisheries to farm-raise fish for sale. Even though they are convenient and cheaper, farm fish are not as healthy as those that are wild caught. The diet of corn, soy and other oils fed to farm fish causes elevated rates of sat-

urated fat and contamination, according to the Alaskan King Crab Co.

A customer of the seafood market, Elijah Wright, discovered the spot when he moved to Columbia a year ago. “They have more options than the grocery store, and

it’s always been great quality,” Wright says. The fresh catch comes with challenges though. COVID-19 has wreaked havoc on the distribution of virtually every product due to breaks in the supply chain, and customers are now used to

Check out the Cajun Crab House Seafood Market at 904 I-70 Drive SW, open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily except Mondays. The Cajun Crab House Seafood Restaurant, 308 Business Loop 70 W., is open Monday–Friday 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.

seeing empty shelves in grocery stores from the disruption. The seafood market is especially volatile while the supply chain falters due to the higher risk of spoilage, which requires more resources to transport the products inland and an overall higher demand than supply.

Dinh said that high demand and a shortage of seafood has caused prices to skyrocket by 200%. Shrimp prices are particularly high right now, in large part due to bad weather for drivers and fishers, high fuel costs and staff shortages.

These fluctuations affect the pricing at the market and restaurant because it costs more to catch and transport the product. Tara Nguyen, the manager at the restaurant, says she doesn’t believe that increased prices will affect sales.

After all, “we have loyal customers who have been with us for years,” Nguyen says. When COVID-19 stops affecting those customer’s lives so acutely, she says they hope to open a new restaurant location sometime next year.

Now, who says you can’t get good seafood in the Midwest?

Baby octopus is among the catch you can find at the market, along with a variety of crab, lobster and scallops.

Columbia cookie pros serve up the dessert decorating essentials you’ll need this holiday season.

BY CHLOE KONRADAh, the holiday season. The smell of pine needles fills the air, fresh snow might soon blanket the streets and families come together to celebrate. Oh, and there’s also the looming pressure to bake for everyone you know and make it look nice while you’re at it.

But don’t stress. With the holiday cookie season peeking around the corner, three Columbia bakers — Trish Robertson of Flour Power by Trish, Chelsea Branscum of Chels the Baker and Alanna T’ia of Sugar Butter and Flour — helped Vox put together a list of decorating essentials (patience!) and tricks of the trade (edible glitter!).

Let’s start with the basics: your delicious cookie canvas. Sugar cookie dough is great for making and freezing ahead of time, Branscum says. Just defrost your batch before baking. Pretty much any recipe works, whether it’s Grandma’s best kept secret or an online recipe with an oversharing introduction, as long as it’s easy to work with. When rolling the dough out, use plenty of flour to make sure it doesn’t stick, and keep it to about 1/4-inch thickness. Then pick your favorite cookie cutters, bake and let cool completely before beginning the fun.

Most sugar cookie connoisseurs use royal icing, a mixture of powdered sugar,

egg whites and water. We’re not sure why something so simple was given such a grand name, but it works well for bakers because it hardens quickly into a matte finish. However, it’s important to watch how thick you make it.

“Getting icing consistencies right so you have really sharp details and you don’t have messy cookies with icing everywhere is just really tough,” Branscum says. Use an edible marker to trace your patterns first, then outline blocks of color in medium consistency icing, and then flood, which means filling those blocks in with runnier icing.

Piping dreams

Learning how to properly use a piping bag can be the trickiest thing for a new decorator to master, T’ia says. “It’s having a steady hand; it’s knowing what size tips to use and what consistency of icing for you to squeeze in your icing bags,” she says.

Keeping it simple is key, in Robertson’s words. “You don’t have to make

it complicated to make it look nice,” she says.

Sandwich bags are a great substitute for piping bags, and practicing your designs on parchment paper ensures the final product comes out perfect. This can even be a way to unwind while learning a new skill. “Make five or six cookies on a weekend and just practice,” Branscum says. “Use it as a little selfcare time or activity.”

Don’t fret. Mistakes will inevitably hap-

Branscum says to give different icing consistencies a try.

Flour Power By Trish 443-800-5099 flourpowerbytrish. com

Chels The Baker chelsthebaker.com

Sugar, Butter and Flour 226-6400 sugarbutterandflour. com

pen, and it’s important not to sweat the small stuff. Robertson says decorations can be a life (and cookie) saver.

“I’ve learned over the years if I didn’t like the way something turned out, I hide it with whipped cream, with chocolate or adornments,” she says.

Robertson also recommends edible silver and gold paint for simple holiday flair, as well as edible glitter for a show-stopping finish. When the holiday season rolls around, she always makes sure to keep some stocked in her kitchen.

In Branscum’s words: “These kinds of things go hand in hand with patience.” Staying flexible and willing to learn is essential. So is having the right utensils. Robertson relies on her offset spatula and maintaining the right mindset. T’ia’s go-to method for improving her skills is heading to the web. “There’s all kinds of tutorials you can do, you just need patience and the right tools,” she says. “Some things you just can’t fudge.”

A VERY HOLIDAY

DECEMBER

12 • MISSOURI THE

PRESENTED BY:

A Black doula group advocates for the mothers and babies who are losing their lives at alarming rates in America’s healthcare system.

BY KATELYNN MCILWAIN

BY KATELYNN MCILWAIN

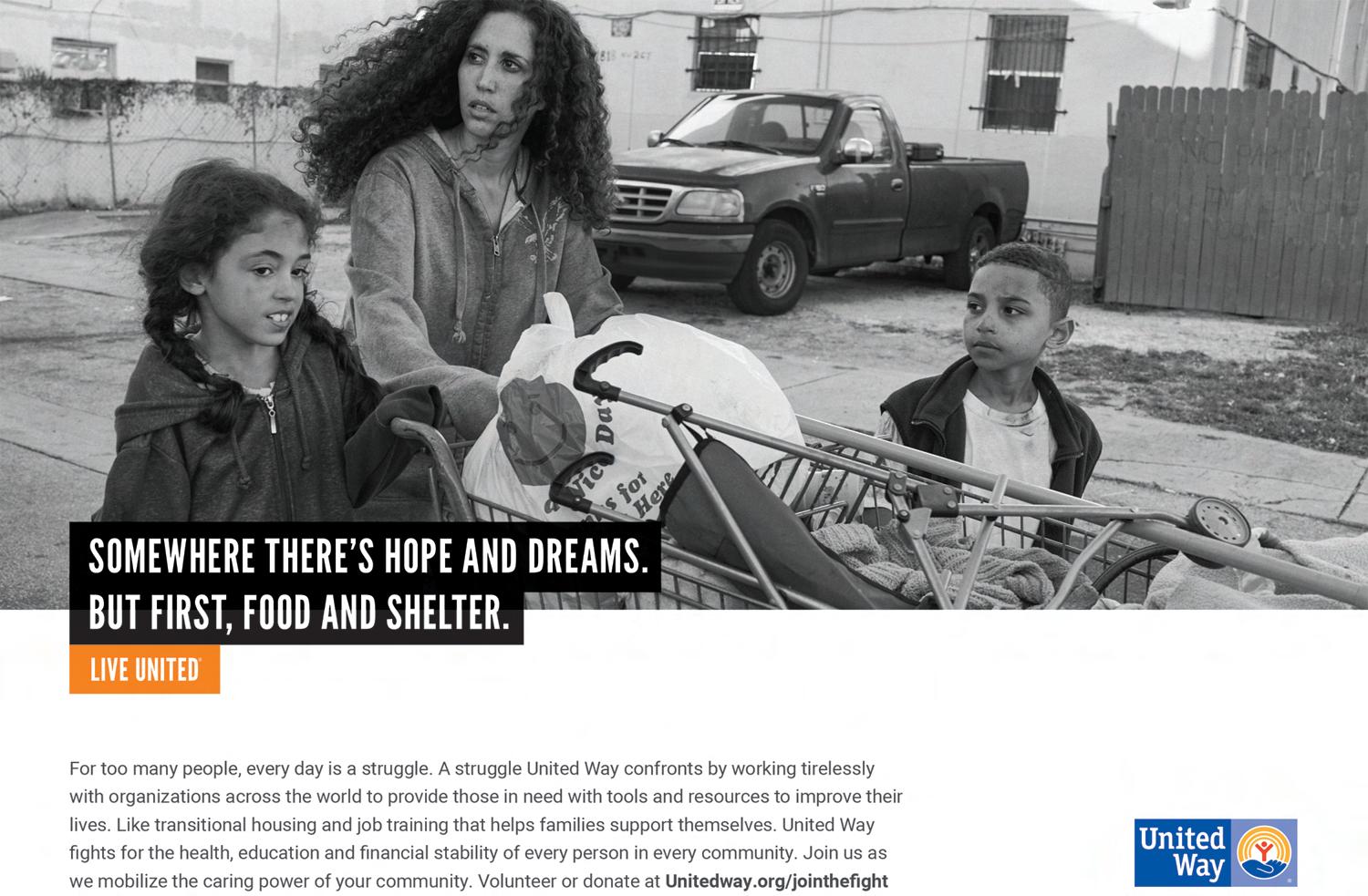

Letters on the refrigerator at a MidMissouri Black Doula Collective meeting remind the group of its mission. Black women are 3.55 times more likely to die during childbirth than white women, and overall maternal mortality in the U.S. is high.

Inductions offered too readily. Cesarean sections that felt forced. At first, the women of the Mid-Missouri Black Doula Collective thought these experiences were their own. But during their first meeting as a cohort in July, they quickly learned that their stories of childbirth were nearly identical.

“There was not one woman in the space that had not had some trauma in the midst of what should be the most beautiful experience of your life and the life that you’re bringing into the world,” says Erica Dickson, founder of the cohort and mother of three.

The U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality among developed countries. There were 20.1 deaths out of every

100,000 live births in 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What’s more, non-Hispanic Black women are almost four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women.

Dickson hadn’t known these statistics until about three years ago. She was pregnant with her daughter at the time and remembers staying up until 3 a.m. one night searching for ways to mitigate her risk. That’s when she learned about doulas.

Doulas support mothers and their families during pregnancy, birth and postpartum life. Without formal medical training, they guide the family through birthing plans and positions and might even help

Rokeshia Ashley was well-informed going into the birth of her daughter, Emery, who was 1 year old in these photos from 2018. Ashley has a doctorate in Black women’s bodies and health communication, but she worries other women won’t know enough to advocate effectively for themselves and their babies.

Doulas support mothers and families from pregnancy into postpartum. Here are some of the roles a doula might fill:

• Develop a relationship with the mother.

• Help create a birth plan.

• Provide stress- and trauma-reducing techniques.

• Offer emotional support during childbirth.

• Encourage participation from the partner.

• Assist in breastfeeding.

with tasks such as housework when postpartum depression makes the at-home responsibilities challenging.

During the birth itself, doulas stand with the mother to provide advocacy, comfort and empowerment. “You shouldn’t have to spend the energy advocating while you’re giving birth,” Dickson says.

The Mid-Missouri Black Doula Collective is breaking ground as the first cohort in Columbia. The cohort brings together 10 doulas with a common goal: educate women about their choices during childbirth and personalize a phenomenon that’s gone from home to hospital.

Before childbirth took off as a hospital industry around the 1920s, having a child was a family affair supported by local midwives. At-home birthing without medical interventions was painful and often fatal. But medical assistance, such as lying on your back to deliver a child, can be counterintuitive or even harmful for mother and baby. It increases the risk of stillbirth. These medical interventions introduce complications that, for Black women, are compounded by hospitals’ roots as racist institutions.

“If my grandmother’s grandmother’s grandmother was birthing children in the worst times that we’ve experienced here

in America, why are we still dying?” says Briana Cato, a member of the collective. “Why are we still getting cut open? Why are we still submitting our birth experience into the hands of someone else, like a doctor, who doesn’t have the personal connection to our birthing experience?”

To Cato, the modernized process feels more like a machine, one that can save lives when complications arise but one that removes autonomy. During her pregnancy, she felt pressured by her doctor to be induced, something that seemed unnecessary according to her own research.

The collective seeks to return to a personalized approach to the birth process.

Dickson is the assistant supervisor of student services at Columbia Public Schools. Cato owns a business that promotes womb wellness. Each member has something to offer, which future clients can consider when choosing a doula.

But doulas are just one part of a larger battle for better health outcomes for women of color in America.

Even as the founder of Uzazi Village, an organization based in Kansas City that works to decrease maternal and infant mortality among Black and Brown families, Hakima Payne knows doulas are only a partial solution to a failing system.

“Hospitals are getting the trust off the backs of trusted community members, who are doulas, but the system itself doesn’t deserve that trust,” Payne says. She trained members of the Mid-Missouri Black Doula Collective.

As a past labor and delivery nurse, she saw enough women enduring births that marginalized them to spur her into the work she’s doing now: helping establish community-based doula programs across the country.

Taylor Gaines, another member of the collective, has a similar experience as a surgical technician at Boone Health. She was born in Columbia and raised among a family of nurses. “Being in healthcare for so long, (Payne) really kind of woke me up to, ‘Hey, these things are going on in our community, and we need to be the ones that stand in and kind of bridge that gap,’” she says.

Courtney Barnes, an obstetrician-gy-

necologist at the Women and Children’s Hospital, is trying to bridge that gap, too. She started the midwifery program at MU, developed the hospital’s low intervention room and launched group perinatal care about three years ago. Perinatal care includes the health of women and babies before, during and after birth. She raised $10,000 with the help of a fundraiser and hospital donors to pay for the collective’s summer training. But to her, long-term change is like trying to steer the Titanic.

“I’m really great at getting the baby out when things are dicey,” Barnes says. “I can do forceps deliveries; I can do C-sections; I can take care of complicated people with medical-comorbidities.

“But OBs don’t do unmedicated physiologic birth as well as midwives. And we know that. We know that midwives have lower infection rates, better patient satisfaction, less tearing, patients feel loved and supported — all of those things by midwives,” Barnes says. “And that’s threatening (for us) because then you have to think to yourself, ‘Well, maybe we could do it a different way that might be better,’ and that’s uncomfortable for people.”

Barnes says many medical professionals might push for medical interventions such as C-sections or inductions because they’d rather do what they know to see the baby delivered than face the

The Mid-Missouri Black Doula Collective looks to make childbirth a safer experience. Some of its members are (from top left): Briana Cato, Jeadawn Cropp, Valen Devereaux, Erica Dickson, Taylor Gaines, Patricia Hughs, Da-Malia Ramsey and Samantha Watkins.

possibility of things going south and a lawsuit following close behind.

“It’s been a journey,” Barnes says. “Change is hard. Change is really hard.”

Payne says she’s sober-minded about the work doulas are doing, but there’s more to be done.

“To ride in on the coattails of trust that the doulas have earned is cheating, and it’s never going to work long term,” Payne says. “The health system has to earn its own trust by changing and becoming less racist.”

The collective is preparing to advocate for mothers both at home and in delivery rooms until that change comes.

During the summer, the group completed certificates in breastfeeding, childbirth education, sexual and reproductive health and perinatal doula training. To become fully certified, members write essays, observe births and develop resource guides. The collective will offer sliding scale services to all women once it’s up and running, especially to women of color who face inequities in healthcare.

“I know that we will be under a microscope as a collective of Black women in the state,” Dickson says.

But the members say they’re willing to do the work even under scrutiny. It’s worth it to save their own lives.

On any given afternoon at Strawn Park or Albert-Oakland Park, you might hear the clattering of plastic discs against dangling chain links and metal baskets. These are the sounds of an up-and-coming pastime: disc golf.

Disc golf is one of the fastest-growing sports in the world with a 33% increase in games played from 2019 to 2020, according to the popular disc golf app UDisc. With four courses that offer varied environments and difficulty, Columbia has become a hub of professional and amateur disc golfers alike.

Disc golf, much like traditional golf, is played on an 18-hole course. Players utilize discs and fling them into metal baskets, which are this sport’s version of holes. Full games can be finished in around an hour.

Many of the city’s ardent disc golfers are members of Columbia Disc Golf Club.

Tracey Lopez from Davenport, Iowa, warms up for a September tournament with other competitors in the Pro Masters Women 50+ division at Indian Hills Park. She finished the Tim Selinske U.S. Masters tournament in fifth place.

Toss up some discs at these parks: Strawn Park

801 N. Strawn Road

6 a.m. to 11 p.m.

Albert-Oakland Park

1900 Blue Ridge Road

6 a.m. to 11 p.m.

Indian Hills Park

5009 Aztec Blvd.

6 a.m. to 11 p.m.

Established in 1983, the organization found its place in the community not long after the city welcomed its first disc golf course in 1980 at Albert-Oakland Park.

The club boasts 1,700 members in its Facebook group and has hosted high-profile competitions, such as the Tim Selinske U.S. Masters Championship tournament, which is sponsored by the Professional Disc Golf Association and took place in September.

Joe Douglass is president of Columbia Disc Golf Club. He says people travel to Columbia from outside the city, state or even farther to play at Harmony Bends, the championship-level course at Strawn Park. “I’ve met people there that came all the way from England to fly it,” he says, noting that people from Canada have ventured here to play, too. “It’s definitely a destination course. It’s on a lot of people’s bucket lists.”

which makes it friendly for newcomers. The “driver” is much thinner and more difficult to control but can also fly much farther. Two versions of the driver exist: distance and fairway, with the former possessing the most potential for speed and distance. Finally, the “mid-range” is what it sounds like; it travels farther than the putter but not as far as either of the drivers.

“Absolutely have a putter,” says club member Vince Kovacs to newcomers. “And some patience, and humility.”

But the name of the game lies in the course layout. In that respect, Columbia offers plenty of variety. Two of the city’s courses are at Albert-Oakland Park, with each divided into upper and lower levels. The two others are at Indian Hills Park and Strawn Park.

Greg Friestad from Iowa City tees off at Harmony Bends, the course at Strawn Park that is designed for high-level competition. Playing in the 50+ division, he finished the U.S. Masters tournament in 20th place in the Pro Masters 50+ division.

To some, the recreation has served as a gateway into athletics, competition and, by extension, community. “I never thought I’d play sports,” says CDGC member Tonya Amerson. “And I love it. And I’ve met so many amazing women from different careers and different backgrounds. It’s awesome.”

Another aspect that makes the sport more accessible is its low cost. “That’s the beautiful thing about it,” member Dave Kennon says, who has a practice course in his backyard. Unlike normal golf, players don’t have to lug around 14 separate clubs. Instead, the disc sport features four general categories of discs. The “putter” is a slower disc that travels less distance and handles much like a Frisbee. It’s easy to control,

Kovacs says the upper course at Albert-Oakland is the most beginner-friendly while the lower one requires players to stretch their drives over longer distances.

Indian Hills Park is a more technical course and features obstructive trees. In contrast, Harmony Bends is the most challenging course, with clear out-ofbounds areas and changing vertical terrain, keeping each hole fresh.