Our Common Ground

Columbia’s patchwork of people promote diversity, inclusivity and community.

Columbia’s patchwork of people promote diversity, inclusivity and community.

Re cently I was asked, “What’s your favor ite moment from the past year?” casual, late-night, hot tub talks, right? One person’s “hot take” answer (his words) was that the COVID-19 pandemic was his favorite part. As he said this, a list of events and happenings ran through my head.

We’ve had a year turned sideways: a global pandemic, social justice movements, a new presidency, a stock market crash and the list goes on. As uncomfortable as it feels, I might have to agree with the aforementioned hot take. But perhaps the better description is that the pandemic was “defining,” not “a favorite.”

The pandemic brought change, reflection and silver linings. Most of all, it allowed many of us to slow down. This time in history is called The Great Pause for a reason. Although it (rightly) caused uncertainty, anger and fear, I think it’s also important to see the positives.

This past year has also shown me that journalism matters more than ever. I’ve always clung to the cliche that journalism gives a voice to the voiceless, and I think that truism has come to light, especially this year.

In one of this issue’s feature stories (p. 12), Vox writer Katelynn McIlwain explores Columbia’s own roots of racial terror. She elevates previously silenced voices and gives us a history lesson on important events that happened right here. Vox also introduces you to the people of The WE Project, a community photography initiative aimed to capture marginalized voices and stories (p. 17).

People and places bind us. Vox captures community and culture, and it’s part of how I’ve come to know Columbia as home. With bachelor’s and soon-to-be master’s degrees, I’m leaving with an education and an appreciation for the people who make Columbia what it is: a colorful community with diverse people, places and experiences.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EMMY LUCAS

DIGITAL MANAGING EDITOR FRANCESCA HECKER

ART DIRECTOR MAKALAH HARDY

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS NOAH ALCALA BACH, CORINNE BAUM, SAVANNAH BENNETT, LAUREN BLUE, EMMA BOYLE, ADAM COLE, JOZIE CROUCH, ROSHAE HEMMINGS, ANNA KOCHMAN, CHLOE KONRAD, KATELYNN MCILWAIN, CELA MIGAN, COURTNEY PERRETT, KAYLEE SCHREINER, RASHI SHRIVASTAVA, SOPHIE STEPHENS

EXECUTIVE EDITOR LAURA HECK

EDITORIAL DIRECTOR HEATHER ISHERWOOD DIGITAL DIRECTOR SARA SHIPLEY HILES

OFFICE MANAGER KIM TOWNLAIN

Vox Magazine @VoxMag

@VoxMagazine @VoxMagazine

ADVERTISING 882-5714

CIRCULATION 882-5700

EDITORIAL 884-6432

vox@missouri.edu

CALENDAR send to vox@missouri.edu or submit via online form at voxmagazine.com

TO RECEIVE VOX IN YOUR INBOX sign up for email newsletter at voxmagazine.com

JULY/AUGUST 2021 VOLUME 24, ISSUE 6 PUBLISHED BY THE COLUMBIA MISSOURIAN 320 LEE HILLS HALL COLUMBIA, MO 65211

EMMY LUCAS Editor in Chief

Cover Design: Makalah Hardy

In February, Bradford Boyd-Kennedy of Rock Bridge Christian Church emailed me about the county’s Community Remembrance Project, and I immediately knew this was a story I wanted to tell. I’d interviewed Boyd-Kennedy for a Vox story in July 2020 about Christian churches’ response to the Black Lives Matter movement. I was honored he contacted me, but I honestly was terrified of not giving the story — about remembering the lynching of James T. Scott in 1923 — the writing it deserved. That paralyzed me for a bit. It was also depressing to spend weeks discussing the brutal deaths of men who share my skin color. Learning that the Scott memorial had been vandalized right after I finished my last interview was especially crushing. I cried. But I think the vandalism gave me the fuel I needed to write with conviction. I hope I did the story (p. 12) justice.

Katelynn McIlwain

Katelynn McIlwain

This invasive fish species is a real piece of carp.

With a new location and a new name, Love Columbia is ready to provide support for even more local families who face poverty.

BY NIKOL SLATINSKAFour months into the pandemic, Shannon Anderson found herself sharing a room at the Red Roof Inn with her spouse and five children, ranging in age from 2 to 12. The Topeka, Kansas, native had come to Columbia for a job at the Boone County health department, but their living arrangements fell through the day before Anderson arrived.

Although she was working, most of Anderson’s paychecks went toward hotel room costs and food. They had come to Missouri for a better life, but the hardships seemed never-ending. “I just felt like I was spinning in a circle with no way out,” she says. Then, a friend recommended she try

In 2020, Love Columbia helped over 900 people with housing, job services and financial assistance. Tasha Fisher (above left) is a service coordinator for Path Forward, which provides life coaching to clients such as Heidi.

something called the Extra Mile financial coaching program, offered by the poverty relief resource center Love Columbia. Anderson sent an email to the program coordinator. That message changed her life.

When the pandemic hit, Love Columbia had to figure out quickly how to serve clients while maintaining safety protocols. When Anderson emailed seeking help, Kelli Van Doren, who coordinates the Extra Mile program and Love Columbia’s transitional housing efforts, began working to find stable housing for the family while also helping with hotel bills.

Anderson’s family wasn’t alone. Within the first week of pandemic closures in March 2020, Love Columbia put 23 families who had become homeless into hotels. Van Doren worked closely with clients to help them fill out applications and arrange for transportation. With the help of grants from the community, the organization helped hotel occupants make plans to move into more permanent housing.

As the pandemic exacerbated fragile living situations, it also heightened Love Columbia’s need for a larger office space. After 13 years, the organization had outgrown its two buildings. Those who have long known the group might still call it Love INC. That’s the name of the national, faith-based charity under which executive director Jane Williams first opened the local chapter in May 2008. It collected and distributed resources, but over time, Columbia’s chapter of Love INC developed its own assistance programs. That self-sufficiency, coupled with rising affiliate dues from the parent organization, pushed the Columbia branch to go independent officially and take a new name on Jan. 1 of this year.

The move to a new location began in fall 2020, when the organization learned that the former Boone County Family Resources building downtown

was available. The property came with two residences, one of which had potential as transitional housing. Such opportunities led the Love Columbia board to decide the location would make a perfect new center.

With the help of donations from the community, including $750,000 from Veterans United Home Loans and $1 million from the Veterans United Foundation, the group made it happen.

The moving trucks finished unloading at the new center at 1209 E. Walnut St. by March 12. A long, narrow hallway extends just to the right of the front lobby desk. Rooms branch off from the corridor, creating numerous little crossroads along the main route.

The layout of the building mimics the nonprofit’s primary objective, which is to serve as the intersection of needs and resources for Columbians. “Someone was in here yesterday and said, ‘I feel like I’m walking down a street,’” Williams says. She hopes the space comes to function as a path toward a better life for clients.

Opportunities await Williams says the 12 coaching rooms at the new location create more opportunity for volunteers and the 16 employees to help a greater number of people. In 2020, Love Columbia found permanent housing for 101 homeless families or in-

Love Columbia’s transformative year included a relocation for its furniture bank and retail store. Previously on Business Loop 70 West, Love Seat opened at a larger building, 2600 Rangeline St., March 23. Love Seat provides free furniture and housewares for families in need. For information about any of Love Columbia’s programs, or to volunteer, visit love columbiamo.org.

dividuals, Williams says. It also provided job, housing and financial coaching to 410 people, supplied furniture to 123 families and funded 21 no-interest loans, plus many other additional services, according to the group’s impact summary.

The past year served as a wake-up call to many about the need to find viable jobs that pay living wages. To accommodate an increasing demand for financial coaching and credit building, Williams says she hopes to double the 114 volunteers who assisted last year.

Tutoring volunteer Rich Wolpert says he could use more help in his department, preparing people for job training and high school equivalency tests. With the upgrade in the new location from his shared conference room, he now has his own office, plus a good-sized classroom next door.

As a retiree, Wolpert began volunteering last August to fill his free time. Most weekdays, though, he gets to his classroom at 8 a.m. and leaves at 2 p.m. “I was in the Marine Corps, and there’s a saying, ‘Anything worth doing is worth overdoing,” Wolpert says. “So that’s kind of my model for the way to do stuff.”

Van Doren says she looks forward to the return of more personal interactions between clients and volunteers such as Wolpert. She worries about how to engage clients and new volunteers in meaningful ways as the numbers of each rise, but she knows forging those relationships is vital. “You can read about poverty or people struggling in the newspaper, but when you know them, when you sit in a room with them, you’re just like, ‘They’re my friend,’ ” she says.

The pandemic exacerbated tenuous living situations. In response, Love Columbia created the Bridge program to address homelessness and help clients such as Verdell (left).

Chloe Callahan is a Bridge coordinator.

Anderson says she thinks the organization’s new downtown home will allow it to help many more people. “When going through that program, I was able to see things in a totally new light,” Anderson says. “I would hope that anyone in it would take advantage of it.”

As large as the new center is, the need for the tight-knit feeling of an interconnected community has never been greater. Down the main hallway, the rooms await, ready to be filled with resources, connection and, as always, love.

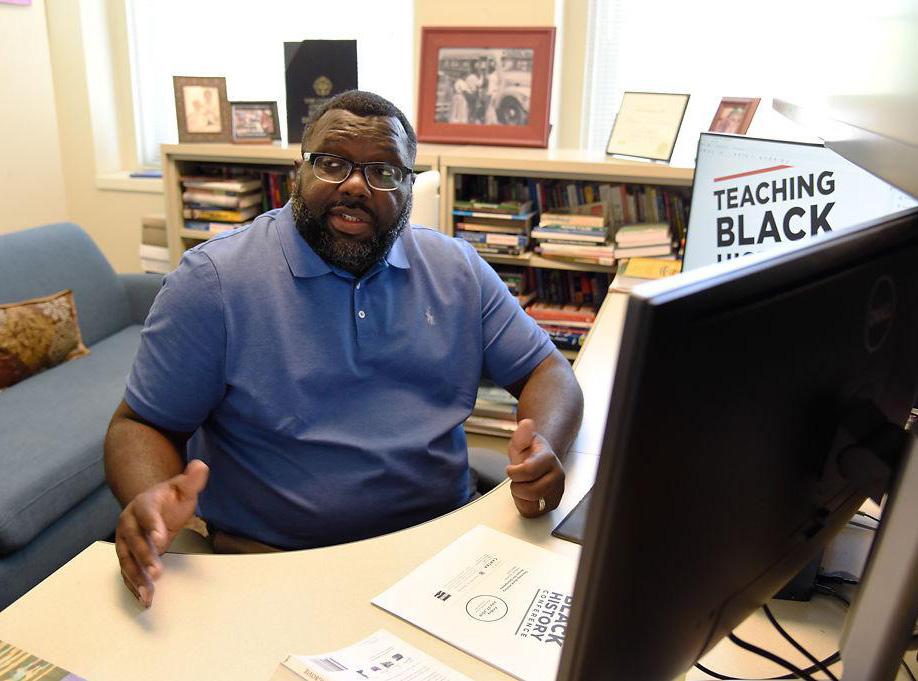

Education professor LaGarrett King advocates for a different approach to teaching Black history, centered on the perspectives of those who lived it.

BY ROSHAE HEMMINGSOn the surface, MU education professor LaGarrett King is calm and collected. However, he is busily preparing for the fourth annual Teaching Black History Conference, attended last year by 1,000 educators.

King, originally from Baker, Louisiana, has dedicated his career to researching how Black history is taught and reforming instructional approaches. He’s become a national leader and has been quoted in outlets such as The Wall Street Journal and USA Today

“LaGarrett is really leading the charge on how we think and teach Black history and what that looks like,” says Greg Simmons, a Battle High School teacher who works closely with King.

The theme of this year’s conference, “Teaching Tulsa’s Black Wall Street and the History of Race Massacres,” reflects an approach to understanding history from Black perspectives. The 1921 Tulsa massacre destroyed the thriving Black business district, and historians disagree if the death toll was 36 or more than 300.

The conference is part of MU’s Carter Center for K-12 Black History

Education, which King founded. King says people are hungry for the knowledge the Carter Center provides. The conference is especially relevant as the U.S. debates teaching critical race theory and the systemic roots of racism. Vox spoke with King about this year’s conference and the education system.

What is lacking in Black history education within the K-12 system?

The Black history we teach is not necessarily history that’s taught through Black perspectives or voices. It’s more of a sanitized, white version of what they think Black history is and who they think Black people are, so it’s this imagined aspect of what Black history is or what they want Black history to be.

What does teaching Black history differently look like?

When you teach through Black people and through Black history, you see a history that’s totally different. There’s this ideological shift that needs to be made within history education for Black folk in terms of this notion of Black

history. Typical renditions of Black history education would be Black history began with European contact and colonization. That makes it seem like Black people didn’t have a history before white people found them.

Why is this conference important?

It is a beautiful conference where you get to listen to, engage with and work alongside those who have the same beliefs you do, and that’s very powerful. A lot of the teachers are some of the only ones pushing the humanity of Black people, and when they’re in this space, they come alive. History teaches us that white people are the center of the historical narrative, and at the conference they’re not. Black people are. Black history is.

Why select the Tulsa race massacre as this year’s theme?

LaGarrett King founded the Carter Center for K-12 Black History Education. More than 1,000 teachers attend its annual conference, which takes place online this year July 23 to 25. For information, see education. missouri.edu/ learning-teachingcurriculum/cartercenter/.

Oklahoma had tons of independent Black towns right after the turn of the century that were booming economically. So to really humanize these particular people and understand the economic trajectory of these people soon after enslavement, I think is something that is a beautiful history that we need to understand and explore. Also, we need to understand that white folk be mad. There’s all these teachings that society attempts for us to do: Pull yourself up by the bootstraps, do this, do that, and you will always be respected. I think historical events like Black Wall Street and what happened to it elicits this notion of all that is BS.

What silver linings have you found during the past year?

The pandemic allowed us to slow down and think about society. We learn history, and we can kind of predict the future. That new Negro vibe coming in the 2020s, it mirrors the 1917, ’18, ’19, booming ’20s aspects because the same things are happening. A new Negro creative class will come out of this because it forced us to sit back, relax and strategize. My biggest thing for young people has always been not necessarily what do you want to be, but how can you help society?

To Catherine Raven discuss her memoir Fox & I with MU’s Sarah Humfield as part of Skylark Bookshop’s virtual event series. The book documents the friendship between a solitary woman and a wild fox, exploring the importance of the relationship we have with our natural world. Virtual event, July 22, 7 p.m., register at skylarkbookshop.com/new-events

Each month, Vox curates a list of can’t-miss shops, eats, reads and experiences. We find the new, trending or underrated to help you enjoy the best our city has to offer.

BY EMMA BOYLE

The MU Museum of Art and Archaeology as it moves to its new home. The museum, which moved off-campus to Mizzou North in fall 2013, will display parts of its collection in the lower east level of Ellis Library. maa.missouri.edu

With fellow creators each month at Creative Mornings Columbia, which is free and open to all. The organization celebrates local talent and connects like-minded people with the goal of forming a community that seeks creativity in all areas of life. The dates of the July and August meetings are still TBD, but will be hosted via Zoom with the themes of “Home” and “Release.” Register at creativemornings.com/cities/cou, monthly on Fridays, 8:45 a.m.

The soothing aroma of wild lavender at Battle field Lavender in Centralia. The farm grows 14 varieties of the herb and is a must-see for na ture-lovers. Depending on the growth of the plants, you can pick fresh laven der yourself or purchase some from the farm’s store. Classes for growing, tasting and crafting with lavender will also be available at Battlefield soon. Battlefield Lavender, 20601 N. Rangeline Road, Centralia, Sat.–Thurs., 9 6 p.m.; Friday 9 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.

The local LGBTQ+ community at Mid-Missouri PrideFest. The event will be held at Rose Music Hall with headliners to be announced, and a parade to kick off the weekend. Aug. 28–29, midmopride.org

King Theodore Records reflects owner Jesse Slade’s love of both music and collecting.

BY ADAM COLE

BY ADAM COLE

The new record shop in Ashland houses pop culture art in addition to stereo equipment and new and used vinyl, CDs and cassettes.

Jesse Slade’s dreams are coming true in 200 square feet of space.

Earlier this year, Slade was working at In The Groove Records in Jefferson City but was ready for a change of pace. He reached out to friend Lars Van Zandt, who co-owns Century Tattoo in Ashland with Cody Finley. The next day, Van Zandt and Finley invited Slade to the store.

“I ran up there, and I thought they were gonna offer me a front desk job or something,” Slade says.

Instead, the tattoo artists offered Slade a side room in their storefront — 200 square feet to be exact — to sell records, play some music and bring his dream to life.

Since February, Slade has been piecing together his storefront. He and his parents, Nella and Phil Slade, have traveled across Missouri to buy records wholesale, and his cousin, Carl Harig, built stacks and shelving for vinyl.

King Theodore Records is set to open July 17. The shop, named for Slade’s Pembroke Welsh corgi, will sell new and used items in store and online. There will be buy-and-sell services for new and used records and stereo equipment, plus CDs and cassette tapes. Music will pump through the store and Century Tattoo.

His spin on a record store

Slade grew up in Lake of the Ozarks in a household with dynamic music tastes. His father listened to country as a child but became an avid fan of Pink Floyd and Black Sabbath. His mother is big on rock

The opening of King Theodore Records in Ashland is the culmination of a lifetime of collecting for music enthusiast Jesse Slade (above). The store, connected to Century Tattoo, will house thousands of new and used records (below) as well as music memorabilia.

and folk, in particular Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. When Jesse was a baby, Nella Slade rocked him to sleep with Dylan playing in the background. His first concert was even Dylan — in utero at 7 months. “He definitely heard the music,” she says.

Slade started collecting vinyl at age 13, when he bought his first record, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, at a garage sale. His mother still remembers when they got him his first turntable at 17. “Ever since then, the boy just went crazy on buying albums,” Nella Slade says.

Everywhere Slade went, his stereo and vinyl collection went with him. They moved with him to attend school at St. Charles Community College, and they moved again when he transferred to Central Christian College of the Bible in Moberly.

Most of that eye translated to a collection showcased in a bedroomturned-den space at Slade’s home in Columbia. The space includes a desk setup, a projector and, of course, a record player. But most notably, the walls are covered with ends and oddities from music, movies and TV. A good majority of the decor is making the move to Ashland.

Coming full circle

Matt Ballou, the artist who created the King Theodore logo (a corgi with a crown, of course), is a friend of Slade’s and teaches at MU’s School of Visual Studies. He says he sees the storefront as an extension of Slade’s den, where he and Slade often hang out, either listening to albums or watching documentaries.

“The thing that I have always been really struck by is how passionate Slade is about the art that he likes,” Ballou says. “The music, the musicians, the aesthetic and the mood of those things. And I’ve always loved talking to him about it. We’ll sit there and we’ll listen to Frank Ocean, and we’ll talk for an hour or two about one song.”

Over the past five years, Ballou says Slade’s work in a record store and starting his own venture provided focus. “I think he feels like he’s steering the ship in a way,” Ballou says.

100 E. Broadway, Ashland Tues.–Sat.,11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; set to open July 17

@KingTheodore Records on Facebook and Instagram

In March 2014, Slade began working at In The Groove. He estimates his collection totaled about 500 albums when he started at the record store, but by the time he left in February, it had increased to about 4,000 records. Much of Slade’s collection is becoming part of his new store’s inventory — about 2,000 total, accounting for a fifth of the store’s vinyl stock.

A self-described “curated hoarder” from shopping garage sales Saturday mornings with his family, Slade now has scattered music and pop culture artifacts throughout the store. “I feel like I have a fairly well-curated eye,” Slade says.

“A lot of times, life can feel like it’s sort of happening to you as opposed to you directing it,” he says. “And what I love about it, from a friendship perspective, is just seeing a guy really feel like he’s gaining some traction.”

Some of Columbia’s theater companies are putting live performances center stage again this summer.

BY SOPHIE STEPHENS

BY SOPHIE STEPHENS

The show must go on — outdoors, that is. For more than a year, local theater companies took shows online or canceled performances altogether. But many are now ready to return live and in-person.

In spring 2020, Columbia Entertainment Company was just weeks away from its April show when the doors shut. CEC went virtual with its show Disenchanted! Stay-At-Home Version in October 2020. Maplewood Barn Theatre put on an outdoor show in June 2020. Others followed. Slowly, in-person theater and performances have returned.

Looking ahead to CEC’s 43rd season, it will return to a full in-person operation. The season will run through early 2022. Audiences can’t wait.

“Our core theater community is ready to come back in whatever capacity we allow them to do so,” says Elizabeth Alexander, CEC’s artistic and marketing director. “I’ve had some people write me and say, ‘If you need someone to just open the curtain and close the curtain during the show, I am there.’”

entertainment

After Maplewood Barn put on an out-

door show in June 2020, the group took the rest of the summer off to reorganize. Now, the company will be running a full 2021 season leading up to Missouri’s bicentennial celebration in August.

“There’s just something wonderful about sitting on the lawn in a lawn chair or bringing your blankets, a picnic lunch, a bottle of wine and just sitting out and watching performances,” says Morgan Dennehy, president of the Maplewood Barn Theatre Board of Directors. “It’s almost nostalgic in its charm. But pandemicwise, I think it probably makes people feel a little safer.”

The theater will follow Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local recommendations. Additionally, the theater is encouraging people to use the online box office and use credit cards during performances to minimize the amount of cash handled.

Maplewood Barn has been producing outdoor theater well before the pandemic, but many other arts events made the transition to outdoor performances as well. True/False Film Fest held its 2021 program outdoors, and the MU Department of Theatre is holding its Summer Repertory Theatre produc -

Columbia Entertainment Company

A Killer Party, June 24–27 and July 1–4, 1800 Nelwood Drive, cectheater.org

Maplewood Barn Theatre

Henry V, July 8–11 and July 15–18; Plan 9! The Musical from Outer Space, Aug. 19–22 and 26–29 and Sept. 2–5, 2900 E. Nifong Blvd., maplewoodbarn. com

MU Department of Theatre

Madagascar: A Musical Adventure, June 24–27 and July 1–3, outdoors at Traditions Plaza, theatre.missouri. edu

Playhouse Theatre Company

Shows will return in October. stephens.edu

tion of Madagascar: A Musical Adventure outdoors at Traditions Plaza in June and early July.

Although outdoor performances can be different due to limitations in lighting, sound or makeup, it’s a unique arts experience. MU student Jake Price, who worked on tech for Madagascar, says the hardest part of moving outside is the set up. “We don’t want the illusion to break,” Price says. “We still want things to kind of blend in and make it seem like a part of the performance.”

Some local venues aren’t rushing to leave online theater behind. Talking Horse Productions has been offering digital entertainment as it waits to resume in-person operations. The company has not yet announced plans for its upcoming season.

Alexander says CEC plans to continue livestreaming in-person performances as long as it’s within the production’s licensing agreements. The theater is producing A Killer Party online, for example. “We were able to reach people who maybe want to come to your shows in person but live out of town or can’t get off of work, and so finding new audience members was a really exciting part of that,” she says.

Dennehy predicts that as fall and winter approach, Columbia could see performing arts return to packed schedules, and the creative community is ready. “No matter what theater it is, it manages to crawl inside you and find a hole and just sit there and live and expand until it just becomes a part of who you are, and when you don’t have it, it’s like a part of you is missing,” Dennehy says.

It took a year for the Community Remembrance Project of Boone County to prepare a recognition of an act of racial terror in Columbia. It took one night of vandalism to attempt to erase that history.

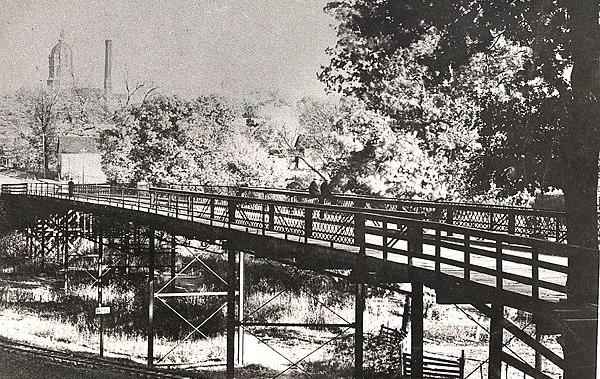

On April 29, the CRP of Boone County, a group established through the Equal Justice Initiative in March 2020, hosted a soil-collecting ceremony to honor the life of James T. Scott, a Black man who was lynched in 1923 at the since-removed Stewart Road bridge. Nearly 200 people attended the ceremony, gathering around the sun-dappled entrance to the MKT Trail, where a memorial plaque for Scott has stood since 2016. One by one, participants scooped soil into three jars labeled with Scott’s full name and the date and place of his death.

Just a week later, the memorial plaque honoring the historic site was forcibly removed and stolen. All that remained was an empty pedestal.

The Stewart Road bridge is gone. So is the original Boone County Jail where a mob dragged Scott from his cell. As Columbia develops, relics pointing to Scott’s murder are vanishing.

Racial terror is often buried and forgotten. The Community Remembrance Project aims to preserve history.STORY BY Katelynn McIlwain DESIGN BY Makalah Hardy Photography by Sydney Lukasezck

As more and more visual reminders of racial terror and hatred are erased and lost to history, the CRP of Boone County strives to remember by collecting soil from where terror was planted. During the ceremony, Wiley Miller, a member of the CRP, noted that as a landscape changes over time, the soil will change the least. By collecting jars of soil, the CRP is committed to remembering.

At the April ceremony, the sound of soulful music, reverent speeches and amicable chatter lifted up into the trees surrounding the MKT Trail entrance as attendees honored Scott’s memory. In 1923, those same trees were a silent jury as a mob hanged Scott from the bridge while he pleaded his innocence. And the soil, carrying the lifeblood of thousands of lynching victims in the United States, remains as a reminder of this country’s dark past.

The CRP of Boone County began with a movement in Rock Bridge Christian Church. The Rev. Sarah Klaassen, the pastor of Rock Bridge, facilitated a book club on Dear White Christians, a book by Jennifer Harvey that calls on white Christians to shift radically their thoughts about race. It caught on so well that the congregation added a second club. Many congregants also knew they needed to be proactive in righting the wrongs of terror against Black Americans. They believe their faith requires it.

Bradford Boyd-Kennedy, a leader within the Rock Bridge church, started noticing his restlessness about race on Saturday afternoons. After serving with the predominantly Black Fifth Street Christian Church, he would return to his home with his wife, Vicki, untouched by the effects of generational trauma his friends at Fifth Street were more likely to have experienced.

“We got to the point where we weren’t surprised to hear about people

saying they were raising their grandchildren and the history of family dynamics and relationships that I seldom experienced personally, at all,” Boyd-Kennedy says. “Finally, I began to realize, well, reconciliation is a wonderful thing, but I didn’t see that approach making many changes in the lives that Vicki and I lived, and in the lives that our Black friends, if I can use that term, experienced.”

He and some other Rock Bridge members reached out to the Equal Justice

Jars of soil from the site of James T. Scott’s lynching are marked with the day he was murdered. In 2011, a headstone for Scott (above) was placed in Columbia Cemetery.

Initiative. EJI is a nonprofit based in Montgomery, Alabama, that works to end racial injustice and reform the criminal justice system. It began organizing CRPs in 2015 within local communities to gather soil, with the aim of looking at history through a holistic lens — one that includes lynching. There are now six local CRPs in Missouri and many more throughout the country. EJI connected Boyd-Kennedy with others in Boone County who wanted to start a remembrance project in mid-Missouri.

As the state with the second highest number of lynchings outside of the South, there is much to remember.

Keslie Spottsville, secretary for the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City, was impressed by Boyd-Ken-

As a landscape changes over time, the soil will change the least.

nedy’s eagerness. She met him when he attended a meeting of the CRP of Missouri in Kansas City. She showed him around the Black Archives, where there is a Soil Collection Exhibit for Missouri lynching victims. The Black Archives is an organization that preserves the history of Black people in the U.S., with a focus on the Kansas City area.

She says it took about a year to get the ball rolling for the CRP in Boone County. Boyd-Kennedy gathered interested members to start planning, and Spottsville helped them through the EJI vetting and training process. When the group was officially established in March 2020, there were about 13 members. It was time to start digging.

Unearthing the past

Brittani Fults, an MU alumna, was one of the people recruited to the CRP of Boone County. Originally from Kansas City, her presence in the group is a testament to history on its own. In 2016, she and the other members of the MU Association of Black Graduate and Professional Students revived Scott’s history by erecting the now-vandalized memorial to him near the entrance of the MKT trail.

Now, five years later, she is helping the local CRP remember Scott and other Black victims in Boone County. Her passion is in facilitating educational opportunities to learn about the Black past. She says previous jobs as the education and outreach coordinator for MU’s Title IX Office and as an investigator for the University of Kansas’ Title IX Office have shown her in real time how lack of educa-

tion causes people to repeat our country’s history of discrimination in the worst ways.

“One of the things that I always tell people is that once you are informed, you do have a responsibility to use whatever tools, whatever skills, whatever capabilities that you have to honor those legacies by doing the best you can for other human beings,” Fults says.

She helped coordinate several educational events leading up to the ceremony, including “The Past is the Present: Conversations on Racial Injustices from the Classroom to the Living Room.” The presentation explored how racial identity and injustice can be addressed in the classroom and at home while being mindful of what is appropriate for different ages. Knowing Black history — and not just the flattering parts — can help even young people start seeing the generational effects of Black trauma and not be complicit in continuing those effects.

Boyd-Kennedy describes it as swimming in white supremacy, being so accustomed to it that it’s no different than a fish swimming in water.

Fults experienced her own frustration with education when she discovered that, as a Black studies minor at MU, she never formally learned about Scott’s murder. “Here I am, paying for this curriculum to teach me about Black studies, the history of Black people in America, and I don’t even know what happened across the street,” Fults says. She knows this education can be uncomfortable. But getting it into open air starts the process of healing.

“I don’t even like being outside,” Fults said as she sat down after Scott’s

ceremony. Despite her discomfort, she recognized that engaging with nature allowed the participants to be active in their commitment to preserve the history that was living and breathing around them. To her, the experience is spiritual, grounding her in the time that has passed since Scott’s murder. “So, even when I’m asking other people to be uncomfortable, I also have to be uncomfortable,” she says. “The onus is on everybody to get uncomfortable. Are you willing to push through it? Are you willing to use whatever resiliency that you have to push through that uncomfortability to get to the next level?”

Why we remember

Nick Foster, a member of the CRP of Boone County, says the project allows him and other white Columbians to use their privilege to address the actions of their ancestors. During his visit to EJI’s memorial sites in Montgomery, Alabama, he went to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. As he walked through rows of hanging steel columns, all of them etched with the names of lynching victims, he paused when he saw the column dedicated to

Photography by Haley Singleton and Courtesy of State Historical Society of Missouri VOX MAGAZINE • JULY/AUGUST 2021 Community members gather soil from the site of James T. Scott’s lynching (left). Scott was hanged from the since-demolished Stewart Road bridge (right), just west of Stewart and Providence roads.“The onus is on everyone to get uncomfortable. Are you willing to push through it?”

Brittani Fults, Community Remembrance Project

victims from where he grew up in Birmingham, Alabama.

“I couldn’t help but think that when some of those things took place, I very likely had family that was there,” Foster says. “I had forebearers who benefited from others being put down and limited in their opportunity to access the bounty of this country. So, I have to — I need to recognize that as a white person that I still benefit from what’s happened in the past.”

One way Foster responds is by discussing and distributing reparations with the Anti-Racism Work Group at Rock Bridge Christian Church. “We don’t know exactly what reparations looks like, but if we want to repair the damage of what’s happened in the past, reparations, it seems to me, is part of the equation,” Foster says.

Preston Wilson, a doctoral graduate from MU and former president of the MU Association of Black Professional and Graduate Students, says remembering keeps us from being purely reactive when we witness modern-day lynchings — the deaths of Black people at the hands of police. The shock value and short-lived hyper-fixation on new occurrences of racial terror can distract from the ways that dehumanization of Black life has seeped into every sector of life in the U.S. Black people will continue to be murdered until we address their dehumanization at the source, he says. “I’ve always said that America is very successful at acute attention but has failed at chronic care,” Wilson says.

When Wilson taught choir at Start High School in Toledo, Ohio, he says he

witnessed district administration and other teachers treat his class, composed of about 85% Black students, differently from others. He says he was discouraged from taking them on field trips because his students “didn’t know how to act.” To him, it clearly was racism, just not as overt.

“Racism is much more than getting called the N-word,” Wilson says. “Racism is much more than police brutality. It’s deeper than that. And we have to get the majority to understand those nuances.”

Why we don’t remember Frank Bowman, a law professor at MU, says he recognizes that remembering racial terror in Columbia can be tricky. The community didn’t just “parachute” into this time. There are still sentimental connections to the past.

To start, he says, there’s still a living generation of Columbians who stood by the city’s response to the Jim Crow and Civil Rights era, specifically with the celebrated placement of Confederate Rock on MU’s campus in 1935. The rock was moved to the courthouse in 1975 and once again to the Battle of Centralia memorial site in 2015.

“It’s not just ancient memories or projections backwards,” Bowman says. “The familial community and inheritances have kind of allegiances and predispositions and guilt or resentment or what have you that you still have in living people who have actually living memory of how we’ve moved to the present day. And then of course, whatever they passed along to their own children.”

Bowman also noted that as a universi-

ty community, Columbia is full of what he calls “imports.” Not everyone here shares the common historical view of the city. “There’s a really uneasy coexistence at times between that largely alien, outsider community and the people who are actually from here, which creates dissonance, I think, at times,” Bowman says.

For Black people, specifically, Spottsville of the Black Archives says remembering can be challenging because it’s traumatizing to relive terror against victims who share your skin color.“We’ve never even healed from enslavement,” she says. And she notices that in Black communities, it’s common not to start difficult discussions about collective pain because of the historical need to be strong, as a race, in the face of adversity. Pausing to heal wounds wasn’t an option. “We have not actually addressed our historic trauma, collectively, in any kind of way. We haven’t had the apparatus, I think.”

When it comes to remembering racial terror, being oblivious is a path often traveled — willfully or not. At the soil collecting ceremony for Scott, the constant sound of cars driving past on Providence Road served as a reminder that not everyone will pause to reflect. A quartet of young men jogging down the trail glanced at the ongoing ceremony but did not stop. Neither did the dog-walkers, though their pups were certainly excited by the crowd of gathered people.

But as long as the soil remains, the history still lives to be told. And the CRP of Boone County is committed to helping Columbia remember.

After Scott’s memorial was vandalized, it took only a day before the plaque was found and welded back onto the pedestal. With enough diligence, history can be restored. And, equipped with knowledge of racial terror, Columbia might be able to tread consciously toward a better future.

As long as the soil remains, the history still lives to be told.

Formed out of the idea that photos can change perceptions by telling people’s stories, The WE Project began with Valérie Berta taking portraits to spark conversations about people’s experiences and give an entry-level glance into who they are.

Berta created the project shortly after the 2016 election. The election “just gave me that push,” she says.

Berta, a photojournalist and Missouri School of Journalism alumna, wanted to do more for her community and decided to utilize her talents as a journalist to push for change. “I can call my reps, I can do all the work that we need to do, but what is my unique gift?” Berta says. “What can I bring to this? I’m a photographer, so I thought, ‘OK, let’s make pictures.’”

She picked up her Nikon D 750 and started The WE Project. “I wanted to celebrate, highlight, put a positive, restorative light on communities who have been traditionally marginalized and not shown in a positive way,” Berta says. “I want to change the world.”

Berta takes all of the photos of the subjects in her own home. She spends time speaking with each person, sits them down in front of a backdrop, recounting some of the most impactful parts of their lives and, with the click of the shutter, captures their vulnerability and truth.

Berta has a gray sheet, black sheet and white panel she uses as backdrops. “The reason was that I wanted to put people on as equal a basis as possible,” Berta says. “This is going to be the same for everybody, it’s going to be the same light, the same reflector, the same thing.”

Despite setting up the portraits the same way, Berta still wants each one to reflect the subject’s personality. Berta does not coach people to smile but instead lets their natural selves come through.

Portraits are the core of the project, but Berta has tapped into other storytelling elements such as video and text to dive more deeply into these life stories. The content is then posted to The WE Project website and social media channels. Berta has also done exhibits and panel discussions at MU’s The Bridge and the Boone County Historical Society to display the portraits.

The WE Project has grown to a gallery of more than 100 portraits since the first in March 2017. Berta compares it to the Humans of New York photo project.

In February, Berta registered The WE Project as a nonprofit in Missouri with the help of pro-bono lawyer Sarah Read. This is the first step to make the project a collaborative effort where Berta would not be the only one shooting the portraits. Berta says funding will be easier for a nonprofit, and she’d love to find a designated space for the project outside of her home.

The need for acceptance and justice extends beyond mid-Missouri, and Berta is looking to plant seeds wherever she can. The best-case scenario, Berta says, is that the project will expand to other states. “If I can go to South Carolina, teach people how to do a WE Project there, give them all the tools and then just leave it for them to do whatever they want with it, that would be so great,” Berta says. “So I got the idea of just trying to widen it to a national level instead of just Missouri.”

To that end, Berta is working to start monthly panels that encourage the community to get involved and foster more discussion. “When

your time is up on this planet, there’s not much to take away but what you did,” Berta says. “I’d like to leave a mark in a positive way to bring something to the table.”

Each time a participant joins the project, The WE Project leaves another mark. Berta has no plans to slow down. “It’s ongoing as long as people are willing to share their stories and walk into my studio and be photographed.”

A na Garcia met Berta in 2017 at Columbia’s Women’s March where Berta was giving a speech. Garcia had heard Berta before and found her inspiring and easy to talk to. Garcia grew up in Mexico, Missouri. However, Garcia and her family emigrated from Mexico City when she was 6. They were undocumented. Garcia didn’t speak about this part of her life until after she received protection through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals in 2016 at age 20. DACA allows undocumented

immigrants who meet specific age, education and time frame requirements to request protection from deportation and permission to work legally. These young undocumented immigrants are often referred to as Dreamers because of provisions that are similar to the never-passed Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors, or DREAM, Act.

Garcia is one of about 2,950 Dreamers in Missouri covered by DACA as of December 2020. Despite receiving DACA protections, she had complicated feelings about the program. In the small naturally lit sunroom in Berta’s house, the two of them got to talking. “There was a lot of this negative idea of what a DACA recipient looks like,” Garcia says.

Undocumented people are often stereotyped as violent and uneducated. Garcia wants to put an end to the stereotypes surrounding DACA recipients and undocumented families. The WE Project gave her a platform to do that.

“I wanted to put a face to it,” Garcia says. “Your neighborhood, your neighbor, your classmate, someone you work with — someone that can look as normal as any other person in your community could be going through this legal situation.”

Garcia wasn’t always as open about her identity as she is now. She didn’t talk about her status until four years ago, and even then she knew some people wouldn’t be as supportive as she’d

hoped they’d be. “My truth was hard to accept,” Garcia says. “It felt like I was embarrassed by it. And to finally just be me was a relief. I knew that for some people, they wouldn’t take it very well. But I also knew that those people probably didn’t really belong in my life.”

Now, Garcia has spoken to classes and given speeches at Moberly Area Community College diversity and inclusion meetings. Her story has been published in both the Missourian and the Columbia Daily Tribune . “The project allowed me to share my story,” Garcia says. “And for people to see me as I am. I think in a way, too, I have been able to heal as well by sharing my story.”

Safa Mohameed, 28, found Berta through a mutual friend. “I like her pictures, her stories,” Mohameed says. “She put it on Instagram, and I wanted to do it.”

Mohameed and her family immigrated to the U.S. from Mosul, Iraq, as refugees five years ago. Mohameed says her family wasn’t safe from terrorists at the time, so they left everything behind and moved.

According to Pew Research Center, about 9,880 Iraqi refugees entered the U.S. in 2016, accounting for 12% of all refugees that year.

The atmosphere was light and comfortable in Berta’s house as she put Mohameed in a variety of poses for her portrait. “She told me how to sit, stand, how to take the picture,” Mohameed says. “And I like her look when she looks at you and says, ‘Oh, I like this — don’t move!’”

Mohameed says it’s rare, but every once in a while someone will make a comment about her hijab or the clothes she wears. “In 1,000, you will find one,” Mohameed says. “Like talking to my kids, ‘Why are you talking in Arabic?’ someone might say. ‘You should talk in English.’”

The WE Project has given exposure to her online clothing business, Oh My Abaya, where she makes and sells traditional abayas. And the story allowed her to put a name and story to the idea of refugees. “The first thing I want people to know is it’s not easy to move from one life to new life and change everything, but it’s possible to do it,” Mohameed says.

Danyiel Kelly was able to speak out about an addiction that plagued him for almost three decades through The WE Project.

In the early ’90s, a woman he was with in Philadelphia had her purse stolen. When Kelly attempted to get her purse back, he was stabbed. “To numb this, I turned to using drugs,” Kelly says.

In 1992, Kelly became addicted to crack cocaine and resorted to criminal activities to support his habit. “I stole from my people, stole from my mom,” Kelly said. “That was really heartbreaking for my family because I’m the black sheep of the family. Nobody else in my family gets into trouble.”

Kelly is the oldest of seven. He spent a total of 15 years in prison on six separate occasions. Kelly was arrested the sixth time in 2013 for failure to return a rental laptop after not making payments. As a result, he was sent to prison for five and a half years. It was then he realized he needed to transform. “I was determined to be a better person, I was determined to be a good son,” Kelly says.

This ultimately led him to Berta and The WE Project. Kelly was attracted to the project because its goals aligned with those he has worked into his life post-incarceration. “I have released the past and embraced it,” Kelly says. “I don’t have to be ashamed anymore, and that’s what I like about The WE Project.”

Kelly, who is not used to being photographed, found himself excited for the opportunity the project provided to capture its participants at their most natural and to give viewers a lens into their life experiences. Berta

says the goal is to connect with others even if just by viewing a portrait or reading a story.

Berta says the more people view the portraits and understand what is happening in others’ lives, the more sympathy and compassion are able to be spread throughout the community.

Kelly hopes his portrait does just that: helps others hear his story and relate to him, his family and his struggle. “You’re not alone, I want them to know that,” Kelly says.

After 27 years, Kelly has found sobriety. Currently, Kelly works as a coach for recovering addicts and encourages collaboration between mental health, recovery and treatment providers. “When they see me, I tell them all the time, I’m just like you guys; I’m just doing a lot better for you,” Kelly says.

Suzanne Bagby met Berta at City Council meetings. Bagby has been active in the Columbia community since 2004 and says she believes in the need for projects that address racism. “We need to have more people saying I denounce racism, I do not accept it here, racism doesn’t live here,” Bagby says.

Berta agrees Columbia isn’t seeing change as quickly as it should, which is why the project aims to

start intersectional dialogues. “I think Columbia likes to see itself as this progressive enclave, and it really is not when you go when you dig deep,” Berta says. “Maybe we’re having a little more conversations, but it’s not being translated to anything tangible.”

Bagby started her own organization, The Bagby Community Helping Hand, with her husband in December 2020. She has experienced this lack of change firsthand. She says initiatives like The WE Project providing teaching moments for young people in similar circumstances. “I’ve really had a lot of not-great experiences living here in Columbia,” she says. “I’m trying to make it better for younger people, so anytime I experience something, I’d like to make it into a lesson.”

The core of The WE Project, sharing stories with the community, is what Bagby believes needs to happen to create change. Hearing stories from the news or online is not the same as engaging or learning from those who have witnessed discrimination first hand. “I can think of a time and place of employment that I should’ve spoken up, and I didn’t,” Bagby says. “When you feel that something is wrong, you’re going to have to speak up and let someone know that this is not right.”

The more people view the portraits and understand what is happening in others’ lives, the more sympathy and compassion are able to spread.

Chef Gaby Weir grew up in a kitchen, which fed her passion for food and knowing its origins.

BY SAVANNAH BENNETT

BY SAVANNAH BENNETT

When Gaby Weir was 9 years old, she spent a summer helping her grandmother cook in Venezuela. Weir learned how to quarter, or cut into four equal pieces, a whole chicken with a dull paring knife. “From that chicken, she taught me to make arroz con pollo, which is the dish that taught me to cook by instinct,” Weir says. “I don’t follow a recipe; I can make it anytime from memory.”

Weir grew up around cooking. Her mother owned a family restaurant in Venezuela, so she helped in the kitchen. Weir washed dishes, made fruit shakes and garnished plates.

By the time she was 14, Weir knew she wanted to be a chef. She overheard a conversation about someone attending culinary arts school, a term she had never heard before. Once Weir realized it would help her become a professional chef, she knew it was what she wanted to do. Weir says it felt like a rush of energy. “I clearly remember the sensation in my body,” Weir says. “I knew at that moment I had to attend culinary arts school.”

But there was a bump in the road that delayed this dream. When she was in high school, Weir, along with her mother and stepfather, immigrated to the U.S. After she graduated from high school, Weir wasn’t able to attend culinary arts school like she wanted because she didn’t have the visa requirement.

At the time, she was a “Dreamer,” an immigrant minor who qualified for the Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, also known as the DREAM Act.

Instead of attending culinary school, Weir worked at fast food restaurants, bagel shops, pasta places and steakhouses. These jobs allowed her to stay close to doing what she loves, making people happy with food, but she still held onto that dream of going to culinary arts school.

When she had her daughter, Erika Weir, and was about to receive U.S. citizenship in 2007, she decided it was time to attend culinary arts school. Weir enrolled in a program at The Hotel at Kirkwood Community Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Weir seized every opportunity she could at the school. She took every class available, participated in every extra activity offered and even studied abroad in Japan. She attended school while raising Erika and working part time at restaurants.

After she graduated, Weir enrolled in a mini course for entrepreneurship and joined the American Personal & Private Chef Association. This way, she could be her own boss. She started Personal Chefs & Private Functions in Iowa City. She ran the company for four years until an agency reached out to her with a job as a private chef for a family in the Kansas City area. Weir worked for that agency for two years until she moved to Columbia with her partner, Christina Holzhauser, and Holzhauser’s son.

In Columbia, Weir opened Chef Gaby LLC and began working as a chef for Windsor Street Montessori School. Weir wanted to work at the school because she could create more attention for food justice.

To Weir, food justice is “the common understanding that fresh food is inclusive and a human right.” The concept supports a community’s ability to grow, sell and eat healthy food. Weir says access to raw fruits, vegetables and meats, especially from sustainable sources, should be readily available to everyone.

Weir considers herself a chef activist, which is someone who uses food and culture as a form of social justice. She says not many people are educated on food justice but that she is trying to help people become more aware of it. People can become more conscious consumers by learning more about their food’s origins through farming practices and sourcing, cultural influences and organic practices.

Weir believes food can make a difference in how people understand their culture. Food can be a powerful tool used to connect people. “When an immigrant child, a first generation American or a child of color sees themselves reflected in the lunch plate and the lesson that comes with it, a warm space is created for that child,” Weir says.

At Windsor Street Montessori School, Weir often switches from chef to teacher to help the children learn about the farmers who grow the food and the culture of the dish. She helps students know where the ingredients come from, what it takes to get the products and the process the food goes through to become a delicious meal. She also invites producers to talk to the students about what they do.

The purpose of these lessons is to teach children that food is a love language. Amy Barrett, Weir’s friend and bookkeeper, describes Weir and her cooking as truth. “Whether a simple to-

Arroz con pollo, rice with chicken, was the first dish Gaby Weir learned to make as a child in Venezuela.

For information about Gaby Weir’s services as a chef, caterer and instructor, visit hirechefgaby.com.

mato soup, traditional pan de jamón or a conversation about capitalism, you will get the truth from Gaby,” Barrett says. As her bookkeeper, Barrett gets to see how Weir develops her menus. Barrett says Weir always does her research when planning where to buy the ingredients.

“She cooks as if she also wants people to get a sense of the history of the dish itself,” Barrett says.

Since fall 2020, Weir has been able to use the kitchen at Windsor Street Montessori School for running her business along with preparing meals for students. “This arrangement is a big deal to me because it is allowing me to reach out to other small independent schools who need catering and who are interested in the same food philosophy that has now become my signature food program,” Weir says.

Her goal is to form a small team to cater to more small schools in the area and focus on school lunch catering.

Pick yourself some wild edibles this summer with this basic guide to foraging four plants around Columbia.

BY ANNA KOCHMANAlthough it recently has gone viral on platforms such as TikTok, foraging has long been a source of free and flavorful food for those curious enough to get outside and explore. Foraging is the practice of finding, collecting and consuming wild edibles, including plants, mushrooms and fruit.

Ann Koenig, a community forester with the Missouri Depart ment of Conservation, says even city dwell ers can take part. Foraging is easily accessible, especially in warmer months, regardless of whether you live in an urban or rural environment.

“A lot of people, when they think about getting out in nature, they think they have to go to the very wildest places,” Koenig says. But in reality, some of the most delicious wild edibles could be just around the corner.

Beginning foragers should proceed with caution because many plants have lookalikes that can be toxic to ingest. Rachael West, a wild edibles educator in Springfield, says newbies should be sure to check multiple guidebooks’ descriptions of a plant before eating it.

It’s also important to be cognizant of your relationship to the natural world. Hannah Hemmelgarn, assistant program director at MU’s Center for Agroforestry, highlights the importance of what she calls “honorable harvest.”

“The way I think about honorable harvest is tending to the relationships that we have with the plants that we harvest,” she says. As a hobbyist forager herself,

Hemmelgarn advises seeking out invasive species to harvest and being conscious of the way you interact with nature. West agrees to target invasive plants rather than native species because invasive species can inhibit native plants’ growth. With these tips in mind, Vox compiled a starting field guide to help you try foraging this summer.

In Missouri, common St. John’s wort mostly colonizes in areas that have been disturbed by humans, such as roadsides and train tracks. From May to September, it produces flowers that are edible.

How to spot them: This shrublike herb’s yellow flowers have five petals. The woody stems have many crowded leaves.

How to consume them: Tea made from the flowers and leaves can have anti-inflammatory properties. In tincture form, it’s said to have numerous health benefits. Watch out for: You won’t want to consume its taller (and toxic) cousin, tansy ragwort. Ragwort reaches about 6 feet tall, while St. John’s wort maxes out around 1 to 3 feet.

Amelanchier arborea

Serviceberries are a great wild edible for city dwellers because they often aren’t, well, wild. Due to its large flowers, this small tree or shrub is frequently planted as an ornamental element in landscaping. Sometimes called juneberry, it produces berries from June to July.

How to spot them: Serviceberry produces showy, white flowers in spring and then reddish-purple berries in summer. Look for alternating, jagged leaves. It can grow to be 15 to 30 feet tall.

How to consume them: “The raw berries are rather bland, but make a good jelly,” according to Wild Edibles of Missouri by Jan Phillips The berries also make a delicious pie or tart — use them as you would blueberries. Watch out for: Pokeweed is a toxic lookalike with similar berries. It sports leaves with smooth edges, as opposed to serviceberry’s jagged ones.

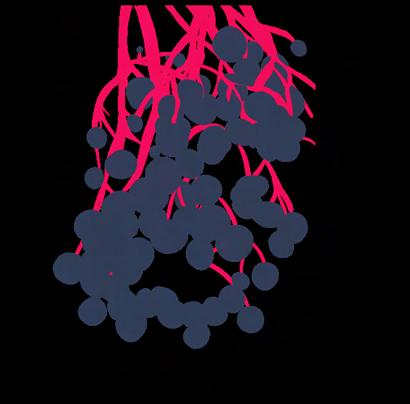

Sambucus canadensis

Elderberry shrubs thrive in the moist soil along streams or rivers. They’re also often found along borders such as fence rows, roads and train tracks. In Missouri they’re often cultivated as a crop. Elderberries flower from May to

July and produce dark purple berries from July to September. “Now is a good time to identify them because they have a very distinctive flower,” Koenig says. How to spot them: Elderberry shrubs have lacy white flowers and opposite leaves with “toothed,” jagged edges, according to Wild Edibles of Missouri The berries are clusters of small, dark purple fruits. How to consume them: Although the berries won’t ripen until late summer and early fall, the flowers can provide delicious flavor if added to pancake batter, muffin mix or other baked goods. When fried in a simple batter, they make tasty fritters. The berries often are used to make juices, jams and syrups. Watch out for: The shrubs’ bark and stems are poisonous. Instead, harvest the flowering tops. Distinguish elderberry

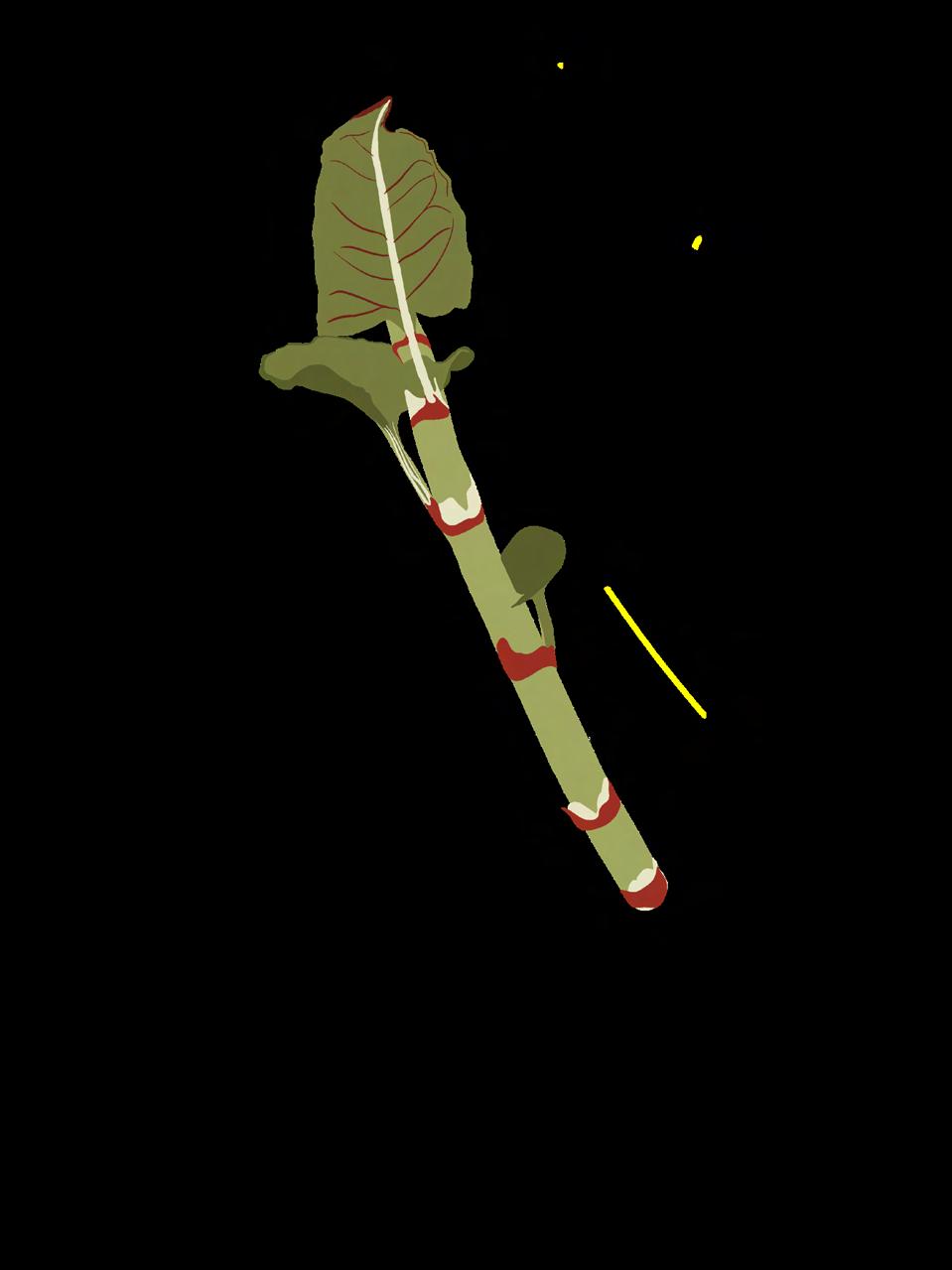

Japanese knotweed (right) is an invasive plant with edible stems.

Both the flowers and the fruit of elderberries (below) are great in cooking.

@chaoticforager. She features a recipe for strawberry knotweed pie, which she says is similar to strawberry rhubarb pie. Watch out for: Noninvasives that resemble knotweed, such as Missouri’s official state tree, flowering dogwood.

Mid-Missouri Buddhists use meditation and mindfulness to confront deep-seeded issues.

BY RASHI SHRIVASTAVA

BY RASHI SHRIVASTAVA

Surrounded by multicolored files, papers and calendars, Venerable Ji Ru sits in an office in Augusta, Missouri. He wears a light-brown traditional Buddhist robe, and his bald head shines in the incandescent light. Miniature statues of the Buddha sit on top of a cupboard behind him.

Ru, the chairman and abbot of Mid-America Buddhist Association, has been a Buddhist monk since 1980. He was born in Malaysia and was introduced to Buddhist teaching in Thailand.

He came to the U.S. in 1993, in part to spread the message of peace and nonviolence. Ru had witnessed firsthand the effects of gun violence and racism in America when he was at a Buddhist center in Chicago. “(The) monk is very sensitive to war and killing because we teach no killing to our disciples and followers,” Ru says.

That shared message extends to Columbia’s Buddhist community. The principles of harmony and nonviolence have been particularly relevant as America grapples with the ongoing murders and police brutality against Black people. In particular, the group, or sangha, at Show Me Dharma has taken strides to confront the pain of racism.

“When George Floyd was murdered, the teachers met,” says Rose Metro, a teacher at Show Me Dharma.

“The Buddha really provides some wonderful tools for dealing with issues of identity and difference,” says Rose Metro, a teacher at Show Me Dharma.

“And we decided that it was important for us not only to make a statement, but to make commitments for the future in terms of what we wanted to do.”

On June 26, 2020, a month after George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis, Show Me Dharma released a statement. Written and signed by Show Me Dharma teachers and board members, the statement urged members of the local Buddhist community, a predominantly white group, to educate themselves about racism.

“It is our responsibility, as practitioners of Buddhism, to examine the ways in which we may have caused harm due to the delusions of racism in all its forms, including white privilege and white supremacy, which are endemic to our culture, whether that harm was conscious, unconscious, or structural,” the statement reads.

The history of the American Buddhist community is not without its own problems.

Buddhism in the U.S. has been dominated by white people, Metro says. The traditions were brought to the U.S. in the ’60s and ’70s. A movement grew, spurred mostly by white men who created their own factions and practices rather than integrating with existing

“They formed communities that felt comfortable to them,” Metro says. “And those were not necessarily comfortable spaces for the diversity of people who exist in the U.S.” It’s a tension point Show Me Dharma is working to ease today.

Metro says Buddhism has answers to some of the painful questions raised in society today about racism and equity.

“I think the Buddha really provides some wonderful tools for dealing with issues of identity and difference,” Metro says. According to the Buddha, ignorance is one of the three poisons that afflict all people who are not yet enlightened. “I see racism as a form of ignorance,” Metro says.

The main practice in Buddhism is meditation, or as the community calls it: “time spent on the cushion.” Metro compares the process of meditation to the slowing of a fan’s blades. “When the fan is running, you can’t see the individual blades; it’s just a blur,” she says. “But if you slow the fan down, you can see its true nature, what it really is. I think meditation allows us to do that; to slow down that blur of the mind.”

This mindful observation and contemplation can help practitioners examine racism’s psychological foundation. “What the Buddha would guide us to do is to notice our reactions, become conscious of them and then react in a more skillful way,” Metro says.

Karma is another concept Metro links to racism. Karma means that people are accountable for their actions and responsible for carrying out their intentions mindfully.

Metro says that when white people first learn about systemic racism, a lot

of guilt and shame can emerge. The Buddha said it’s important to balance compassion with equanimity. “Equanimity is ‘I’m going to try to take the wisest and most skillful actions I can to address racism,’” Metro says. “‘But, I also can’t control every aspect of that process, right? I’m going to make mistakes.’”

Show Me Dharma, which was founded in 1993 by Ginny Morgan, launched a book club to discuss Larry Yang’s book Awakening Together: the Spiritual Practice of Inclusivity and Community, as well as foster revelations around racism, white privilege and how to mindfully address it. The group has also tried to join sessions led by Buddhist teachers of color through Zoom, Metro says. But it is a task that has proven to be difficult.

“We also have realized that the relatively small number of teachers of color who exist across the U.S. are extremely in demand right now,” she says. “We also don’t want to put extra burden on them.”

With these efforts, mid-Missouri Buddhists are working to help unroot racism and bring more compassion.

As Ru says from Augusta: “We need to live in harmony. We need to live in peace. We are interdependent on each other.”

A local researcher has been fishing for ways to curb the spread of Asian carp by finding markets for the invasive species.

BY COURTNEY PERRETT

BY COURTNEY PERRETT

Picture an ugly 20-pound fish leaping skyward, smacking into an unsuspecting boater. That fish, and hundreds of thousands like it, is the invasive Asian carp, the subject of a yearslong MU research project.

Mark Morgan, a researcher in MU’s College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, has cultivated a new way to curb this species’ proliferation throughout the Midwest. He devised a method to turn the fish into a powder, which he hopes will help address developing communities’ lack of access to nutritious food. That powder will be shipped to countries in need through a Missouri-based humanitarian program, Convoy of Hope.

Two types of Asian carp, the silver and the bighead, live in the slow-moving waters of Midwestern rivers. Originally brought to America in the 1970s from China, the carp were intended to rid ponds of pests and improve water quality, Morgan says.

This became problematic, however, when some carp escaped during a flood from an Arkansas fish farm into the Mississippi River and started rapidly spawning. When the carp population exploded, the species had a disastrous impact on other fish, Morgan says. That’s because invasive fish outcompete native fish for the plankton that make up the basis of the food pyramid, causing many local fish species to decline.

Asian carp are also a safety risk for anglers. Silver carp are notorious for leaping from lakes and rivers when they sense boat engine vibrations. This jumping has been known to damage boats and injure anglers with broken bones or concussions, Morgan says.

It is a challenge, he explains, to stop the carp from getting into more Midwestern rivers and lakes, as they spawn multiple times a year. When Morgan realized the invasive carp’s damage to local fish populations and the industry, he started trying to see if there was a local market for these fish by serving seasoned, smoked carp as food.

It turns out, Missourians are willing to try the carp for the novelty, but it did not catch on because of the fish’s stigma as trashy or cheap, says Quinton Phelps, assistant professor at Missouri State University.

Asian carp fillets consist of a white meat that crumbles off the bone. It can be seasoned to resemble sausage or ground

turkey for use in chili or tacos, Phelps says. Although people are willing to eat carp disguised as something more appetizing, it is not sustainable for anglers to sell the fish because the market price is so low.

After having little luck with the local market, Morgan traveled to a remote village in Haiti with a sample of carp to do a taste test with locals, looking for a market in developing nations.

The trip inspired Morgan to pursue a viable method of transporting the fish. “There’s no way to freeze, salt, package and smoke it,” Morgan says. Instead, he pulverizes and dries carp meat into a fine powder that can be used as a dietary supplement.

Carp is high in nutrients, including protein, iron, calcium and a full spectrum of essential omega and amino acids, which are all important for the body to function.

During his trip, Morgan learned that half of Haitian women are anemic, meaning that they have low levels of iron, which can, among other things, threaten reproductive health. He realized if he could make the powder product viable, it would help women there and elsewhere get the nutrients they need to live healthier lives.

Asian carp can weigh 20 pounds and be 1 to 2 feet long. Commercial fishers can catch up to 5,000 pounds of them per day but there is little market for the fish, says MU researcher Mark Morgan.

Morgan started a partnership with Convoy of Hope after meeting senior director Kevin Rose at an event in Columbia. As part of its school-based feeding program, the group will be shipping Morgan’s carp powder for free to a number of the 21 countries it serves. “To us, having a product like this puts more resources in our toolbox,” Rose says.

Columbia Entertainment Company debuts its online musical A Killer Party: A Murder Mystery Musical. See if you can crack the case.

June 24-27 and July 1–4, 1800 Nelwood Drive, $14, cectheater.org

Henry V

You might think the king is but a man, and you’d be right. Shakespeare returns to the Maplewood Barn Theatre with Henry V. July 8–11 and July 15–18, 8 p.m.,

2900 E. Nifong Blvd., $13 for adults, $8 for children

Anyone can draw out their artistic talents with Columbia Art League’s Sunday Sessions. These biweekly classes cover a range of topics, including finger painting in oils with Pam Ganior, pamphlet stitch books with Mary Sandbothe and even smartphone photography with Kelsey Hammond.

July 11, July 25, Aug. 8, Aug. 22, 2–4 p.m., from $20

Join the MU Museum of Art and Archaeology’s virtual events for conversations about selected artworks from the museum’s collection. Attendees will have the chance to sketch the pieces following the discussion.

July 20 and Aug. 17, 10–11:30 a.m., free, register at v

With this series, Ragtag Cinema partners with community groups to

educate Missourians and inspire conversation surrounding difficult topics. For the showing of Judas and the Black Messiah, the theater will join with ROCK the Community to discuss the power of community and genre. July 22, Ragtag Cinema, free

Voices of Arrow Rock, Spirit of the Missouri Frontier is a production about the realities of the mid-19th century Missouri frontier. It is an official Missouri Bicentennial project. Aug. 7, 10 a.m., Christian Church on Main Street, Arrow Rock; Aug. 8, 2:30

p.m., Center for Missouri Studies, Columbia, free, 660-837-3231

Boone County Fair

For the first time in more than 5 years, the Boone County Fair will be held in Columbia. Experience the brand-new car show,

a demolition derby, talent competitions, livestock shows, a family-friendly carnival, the Boone County Country Ham Breakfast and more. July 20–24, 5212 N. Oakland Gravel Road, some events require payment, theboonecountyfair.com, 474-9435

Lace up your running (or walking) shoes for the Hope for Heroes 5K event, hosted by The Food Bank for Central and Northeast Missouri. The run/walk benefits the Veteran VIP Pack Program, which helps food-insecure veterans obtain nutritional items.

June 26, 7:30 a.m. to noon, Cosmopolitan Park, register at sharefoodbringhope.org/ hope5k, $30

It’s more than OK for kids to get messy in this obstacle course. Kids ages 4 to 15 will traverse under and over walls, scamper over balance beams and splash through mud. July 10, 7:30 a.m., Gans Creek Recreation Area, $25 per child, 874-7460

Light up the night on the MKT Trail at Kaleidospoke, a self-paced 8-mile bike ride from Flat Branch Park to Twin Lakes Recreation Area and back. Riders can enjoy s’mores at the Twin Lakes halfway point. Aug. 28, 7–10:30 p.m., Flat Branch Park, $17, helmets and front and rear lights required, register at como.gov/parksandrec

In honor of Columbia’s 200th birthday, Odyssey Chamber Music Series will celebrate the city’s past and present musical history. Keep an ear out for the classic 1924 composition Rhapsody in Blue, and you might even get to join in a “Happy Birthday” serenade to our fair city. July 2, 7–8:30 p.m., First Baptist Church, 1112 E. Broadway, free

The Bel Airs

The influential surf rock group will bring its eclectic grooves and showmanship to the banks of the Missouri River just in time to celebrate Independence Day. July 4, 6–9 p.m., Cooper’s Landing, free

Black Pumas

Ninth Street will once again be alive with the sound of music. Grammynominated group Black Pumas rocks Columbia’s Summerfest with its Austingrown funk. Aug. 6, 6 p.m. doors; 7 p.m. show, Ninth Street, $35

Shakey Graves

Texas musician Shakey Graves will shake up The

Blue Note’s Summerfest series at Rose Park with his blend of blues, country and rock ’n’ roll. Aug. 13, 6 p.m. doors; 7 p.m. show, Rose Park, $30

Food Trucks in the Parks

Grab some tasty takeout from one of Columbia’s many food trucks at Cosmo Park, Stephens Lake Park

This summer, say “hi” to food trucks like Mr. Murphy’s (above left) in Columbia’s parks, or take in a show at Rose Park with Shakey Graves (above right).

or Cosmo-Bethel Park. Or picnic and enjoy the scenery. July 7, repeats the first Wednesday of every month, 5–7 p.m.

Blues & BBQ Bike Night

Vroom over to Mid America

Harley-Davidson for fingerlicking food from Como Smoke & Fire. Blues DeVille Band provides toe-tapping tunes. July 23, 5–9 p.m., 5704 Freedom Drive, free

Ezra Prince claimed the kingly crown during the Mid-Missouri Pride Pageant held June 4. Seven contestants (five queens and two kings) performed lip-syncs and dances on stage during the night of celebration. Lorilie was named queen, Bennifer Lopez was regent and Prince was king. The pageant was canceled last year, so this was the first crowning since 2019. Mid-Missouri PrideFest will also return this year, with events Aug. 28 and 29 at Rose Music Hall.