With some 25,000 schlösser (castles, palaces or manor houses) scattering Germany, you don’t have to travel far to live out your own Grimms’ fairy tale

Reviewed by James March

Raise the drawbridge!

Parkhotel Wasserburg Anholt has big fairy-tale energy, thanks to its impressive moat. But it’s just one of a host of grand castle stays around Germany, with plenty making the most of their medieval roots

A moat lends any castle stay a touch of gravitas, and this is no exception. Set within a 34-hectare park bursting with magnolia trees, this grandiose medieval stay lies beside the Dutch border in Germany’s deep north-west. An ornate on-site museum is a delightful bonus for guests, with works by masters such as Rembrandt, Jan van Goyen and Bartolomé Murillo on display, while the Mediterranean-influenced restaurant is even more unexpected amid all this Germanic grandeur. Beyond the castle grounds, the outdoors beckon. Spot lynx, boar and deer at nearby Biotope Wildlife Park, or take to the gently undulating roads of Münsterland to cycle the untaxing 100 Castles Route. Rooms from £179 per night, including breakfast; schloss-anholt.de

Alamy

Scanning bouquets of forest from its rocky plateau in the Bavarian upland of Franconian Switzerland, this castle’s bucolic setting is as peaceful as it is spectacular. Mornings are soundtracked by gentle birdsong, while the hallways and lounges inside are flanked by silver suits of armour and mounted swords. These nods to the hotel’s medieval aristocratic history extend to the decor inside the 22 rooms and suites, where you’ll find patterned canopy beds and Gothic windows. The vibe extends to a meat-heavy Franconian menu, while outdoor activities are no less on brand, including archery, axe throwing, knights’ tournaments and falconry. Doubles from £186 per night, including breakfast; burg-rabenstein.de

While the battlefields of South Africa’s KwaZula-Natal province shine a light on its difficult past, a war on poaching is currently being won in its private reserves

ÒWe have to learn from history, but we don’t.” The heartfelt words of Mphiwa Ntanzi, a guide for Fugitives’ Drift, were carried on the bitterly cold wind as we huddled on a ridge overlooking a large plain. It was there that a force of 20,000 Zulu warriors had obliterated a British contingent in just two hours in the Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879. As clever as the Zulus were, this was as much a tale of colonial arrogance and wasted lives.

We were in the heart of the South African province of KwaZulu-Natal, and Mphiwa had just finished explaining that when the Zulus first came to this area and found plentiful grass for their cattle, they named it the Place of the People of Heaven.All the British of the late 19th century saw was a chance to merge South Africa’s hotpotch of colonies.They believed that the Zulu stood in their way, so they engineered a war they thought they’d win.

Mphiwa had talked us through the events leading up to the battle in which the British mounted their invasion of Zululand, confident of routing the Zulu army. Thinking their enemy was 55km away, a temporary camp had been set up at Isandlwana while the commander of the British forces in South

Africa, Lord Chelmsford, led the majority of the troops away to look for the Zulu.

“They underestimated their enemy,” said Mphiwa. “A dangerous thing to do.”

Mphiwa was born locally, and for him there was a personal connection to this history.“My grandfather and great-grandfather fought in the battle on the Zulu side,” he revealed.

We drove down to the battlefield and were met by the sobering sight of numerous white cairns marking where the bodies of British soldiers were found. In the car, Mphiwa played a tape of the late historian David Rattray setting the scene for the battle, outlining the characters involved: “It reads like a great Shakespearean tragedy,” the recording narrated.

the 1964 film starring Michael Caine. Based on events in the hours following the routing at Isandlwana, it tells the story of how a small number of plucky Brits held out against the Zulu army in nearby Rorke’s Drift.

“Several thousand Zulus marched on Rorke’s Drift and its 139 British soldiers”

A gifted storyteller, Rattray did much to popularise battlefield tours of KwaZulu-Natal before his untimely death. I was staying a couple of nights at Fugitives’ Drift, a lodge and private reserve that is still home to his family. I had attended one of David’s lectures back in the 1990s, but I could remember little from it; instead, the first picture of the AngloZulu war that came to mind was from Zulu,

In the afternoon, I headed to Rorke’s Drift to see it for myself, and it was a shock to find just how intimate the site was. In 1879, the then mission station had been commandeered by the British as a field hospital and supply depot, and a small garrison was left there while the British forces headed out in search of the Zulu army. Following the battle of Isandlwana, several thousand Zulus marched on Rorke’s Drift, where just 139 soldiers, some already ill or injured, repelled them after 12 hours of fighting.Their only defence was a swiftly erected wall made of maize bags. ElevenVictoria Cross medals were awarded to men who fought there, the most ever in a single action by one regiment.

The hairs tingled on the back of my neck as I heard the story of the encounter, vividly told by another one of Fugitives’ Drifts’ guides. As we walked around the outside of the

After surviving colonisation, deforestation and enforced labour, Costa Rica’s Indigenous peoples are reviving traditions and ecosystems lost to the centuries – and visitors are welcome to join in

Words Lina Zeldovich

Jeffrey Villanueva picked a ripened yellow cacao fruit off the tree and hacked it open with a sharp knife, showing me the white seeds inside.

On a wood-burning stove underneath the tall canopy of the Costa Rican jungle, more seeds were already roasting inside an iron pot, giving off a fragrant aroma. He stirred them with a wooden spoon and, once they were done, transferred them onto a long, hand-carved tray.

Next, he ground the dark-brown seeds by hand, unloading the tray onto a boulder before picking up a stone and rocking it back and forth across the seeds, crushing them into a powder.

cultures found here. The country is home to eight Indigenous peoples, comprising 24 communities spread across the country. Each is preserving and restoring traditions, foodways and crafts, some of which were thought lost following colonisation and the arrival of the Spanish in the mid-16th century.

“Costa Rica is home to eight Indigenous peoples, comprising 24 communities spread across the country”

“Want to try your hand at it?” he asked me in Spanish, translated by my guide, Pedro Flores. I took over the stone, which I could barely lift, and mimicked Jeffrey’s hand movements the best I could. Once the seeds were pulverised, we gathered up the powder. Soon enough, I was sipping my morning cacao drink the authentic way: boiled in water and without sugar or milk. It was a far cry from the way I make hot chocolate at home, using a pre-packaged mix.

Costa Rica is famous for its forests and wildlife, but many visitors overlook the

)

Jeffrey belongs to the Bröran people of the Térraba (also spelt Teribe) community, who have resided on the banks of the Térraba River in southern Costa Rica for many generations. Though traditionally hunters and fisherpeople, the Térraba also grow beans and corn, embracing the wisdom of their ancestors, which states that: to have a long, healthy life, all food must be made and eaten fresh. The morning’s cacao-making process was a testament to that – it was the freshest, most fragrant drink of cacao I’d ever savoured.

The tour operator I’d arrived with works with the local communities to help them share traditional recipes and crafts, as well as tell their stories in their own voices. However, that history often isn’t easy to hear.

Before the Spanish arrived in Costa Rica, its Indigenous peoples lived off their ancestral lands for generations, taking only what was needed and conserving the rest.When

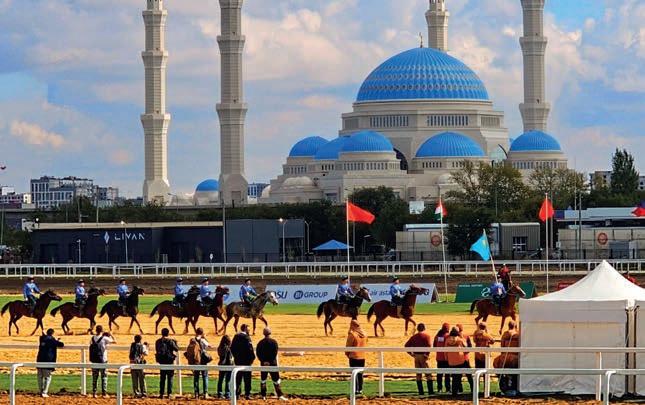

As the final arrow of the World Nomad Games is fired in Kazakhstan’s capital, we explore a nation balancing its nomadic roots with a fast-evolving future

Words & photographs George Kipouros

Dust swirled as teams of horses thundered across the steppe, their riders engaged in a fierce contest of strength and skill. Around them, the air crackled with more than just adrenaline; it was the sense of something ancient being brought back to life.

I was watching a game of kokpar, a sport that stems from the nomadic tradition of Central Asia, in which riders gallop at full tilt while battling for control of a dummy goat carcass. It’s rugby meets polo, a true test of endurance and, as I discovered, not for the faint-hearted.

Tension filled the air as the teams from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan faced off.The thunder of hooves echoed as the former raced the carcass over the scoring line time and again for a home win, to the roar of the crowd.

“The horse was domesticated here on the Kazakh steppe more than 5,000 years ago,” said Yelmira, my local guide, hinting with a tinge of pride that the preternatural skill of the players had been a long time in the making.

Above us, an arrow display sliced through the sky, tracing arcs reminiscent of the paths once travelled by the nomads who ruled these lands.This was the start Kazakhstan had hoped for, as it welcomed

athletes and spectators to capital Astana this past September for theWorld Nomad Games, a sporting event unlike any other.

The Games are a celebration of ancient traditions, where sports such as zhamby atu (horseback archery), bürküt salu (eagle hunting) and er enish (horseback wrestling) take centre stage. It’s a reminder of the shared heritage that once united the nomadic peoples of the Great Steppe, and its fifth edition saw some 2,500 athletes from 89 countries gather for the “Nomad Olympics”. For me, the Games were an opportunity to discover seldom-visited Kazakhstan ⊲

the

commence (

) A

– one

–

Slow travel has never been so fast! Join a train journey across Andalucía, where high-speed rail lines linking the region’s great sights reveal how the legacy of Islamic-era Spain lives on

Words Martin Symington

ÒWe are sitting in the centre of the greatest city of the medieval Islamic world after Constantinople,” pronounced a ravenhaired lady at the table next to mine.

My ears perked up. I was sat in a teteria –North African-style teahouse – in Córdoba, having stopped for a sticky date pastry.The lady (Yasmina), it transpired, was a guide at the neighbouring Mezquita de Córdoba, the giant mosque that was once the crown jewel of Al-Andalus, a part of the Iberian Peninsula that was once ruled by a succession of Caliphates, who held sway here for nearly eight centuries (711–1492 AD).

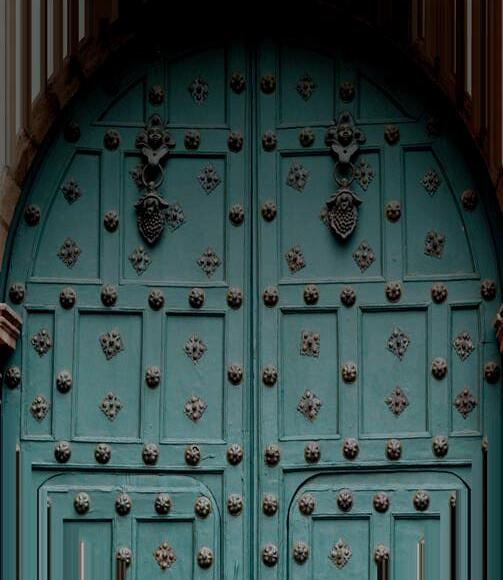

I already had an inkling of what my new friend meant.While threading the medina-like maze of plazas and alleyways in Córdoba’s Old Town, my nostrils had registered the

aromas of mint and incense. I’d seen bronze doors carved in Arabic script, and I’d spied a mihrab prayer niche in the wall of a Christian chapel that hinted at another life entirely.

The ‘Moors’, as the Arab and Amazigh (Berber) peoples who invaded the Iberian Peninsula are known, have left their imprint on everything in Andalucía, from architecture and music to food and language.Their Islamic culture gave the region its character, which has long struck me as remarkable given nowhere else feels so full-bloodedly Spanish. And yet it took a rail journey through the great cities of southern Spain – Seville, Córdoba and Granada – where the secrets of Al-Andalus are preserved, to make me see that these two things are often inherently connected.

“Spain has the second-largest highspeed rail network in the world”

It was a revelation made possible by an altogether more modern invasion that happened here 32 years ago, when the first stretch of Spain’s 4,000km of high-speed rail lines opened, connecting Seville to Madrid.Today, Spain has the second-largest high-speed rail network in the world (after China), making it easier for visitors to join the cultural dots across its 17 autonomous communities.

In addition to the services already running, train operator Iryo began high-speed-services from Madrid to Seville and Córdoba last year.There are now more ways than ever to explore the region at speed, even if you take it slowly in between. So, where better to start than the first capital of Al-Andalus, where Spain’s modern rail revolution also began?

As the cognac houses and wineries of south-west France increasingly open their doors to the public, a trip to Bordeaux and Cognac reveals the history behind our favourite tipples

Words Juliet Rix

Bordeaux and Cognac. Across the globe, these names conjure images – and maybe tastes –of rich vin rouge and golden spirit. Few will immediately think of the historic towns in south-western France after which these drinks are named. But the two remain inextricably linked, and a visit to the region brings them deliciously together in a haze of creamy stone cities and lines of green vines, ancient monuments and modern museums, global brands and small family makers.

The relationship between this part of France and alcohol goes way back. Rémy Martin might be celebrating its 300th anniversary this year, but it’s not nearly the oldest of the cognac houses.And even those venerable producers are mere striplings when compared with the area’s history of wine production, which probably began with the Romans making vinum in Burdigala (Bordeaux).

Fittingly, it was here, in France’s UNESCO-listed ‘City of Wine’, where I began my journey. Bordeaux’s historic heart, built from local limestone, glowed as if washed in sweet Sauternes. My eye was caught by the grandeur of the merchants’ houses lining the crescent curve of the Garonne River (which gives the city its ‘Port of the Moon’ moniker).This was once the busiest port in the world after London, and for centuries it was also the only route to market for the region’s wine.

Today, the 18th-century Place de la Bourse – an iconic sight when it was built – is once again the most admired spot in the city.The glistening, Instagram-friendly reflection of its palatial buildings in the 21st-century Miroir d’eau (Water Mirror) draws visitors aplenty. I, however, chose to leave them behind, walking through cobbled streets and elegant squares until I came to the Gothic Cathedral of St André.

It was here that the 15-year-old Eleanor of Aquitaine was wed to the future King Louis VII in 1137, an early milestone in a notable life. Having ticked off Queen of France, she later married Henry Duke of Normandy, who then acceded to the English throne as Henry II, making her Queen of England. Loyal to her hometown, Eleanor awarded Bordeaux a monopoly on wine imports to her new kingdom, beginning a special relationship that (with a few bumps) continues to this day.

and long, low chais (above-ground cellars). You can see inside one of them – the former residence of Louis XV’s royal wine broker –at the BordeauxWine andTrade Museum.

At 89 Quai des Chartrons (now the US consulate), there are more ghostly reminders of the area’s wine-trading past. I paused at the front to look at a small relief of Thomas Jefferson.

“Bordeaux’s Fête le Vin is the largest wine fair in France”

The British were not only key consumers of wine, but in due course also became makers and traders (you may still notice Anglo names on Bordeaux wine labels). Upriver, in the Chartrons district, merchants – first Dutch, then British and Irish – built stylish homes that were more than residences. Behind their fashionable frontages lay working wineries

The American ambassador to France and president-to-be was here in the 1780s “for his health”.

A passionate oenophile, Jefferson had planted vines in the US and was trying to make his own wine; it proved an enterprise less successful than politics. Heading down a passageway at the side of the building, I found echoes of the past on the limestone wall: circles left by the ends of barrels that were stacked here before being rolled to waiting ships. It’s a history that still resonates today.

The city’s past is played out on vast screens at the uber-modern Cité duVin museum, on the banks of the Garonne. Its tower swirls like wine in a glass, while the multi-media galleries inside transport visitors across the world of viticulture. I ended my tour with a glass of red on the roof, looking right along the river to the orangey arches of the 1822 Pont St Pierre – which is gorgeously floodlit at night.

In the distance, the masts of tall ships rose like signposts from the past, as if still awaiting a hull full of wine.Three of these spectacular vessels visit each year for the Bordeaux Fête le Vin, the largest wine fair in France. I’d arrived just as it was kicking into gear.

Wooden stalls ranged across a kilometre of the riverfront. So, with my festival pass in hand (which included 11+ tastings), I took a gustatory wander through some of Bordeaux’s six major wine regions, 65 appellations and thousands of winemakers, from Saint-Émilion to Sauternes. And as the sky darkened, I turned my eyes upward for the drone show, to see lights form and reform into falling vine leaves, pouring bottles and emptying glasses.

This festival is paradise for the viti-curious. Often, the person filling your glass is the producer themself – a growing number of whom are women. It was here I met Sabine Silvestrini of Château Chéreau, who told me of the difficulties the region’s winemakers face.

“It’s a challenging time, with consumers drinking less red wine and climate change bringing more extreme and unpredictable weather,” she explained.

Indeed, some 75% of the region’s wineries are trying to reduce their carbon footprint;

Step into a world of rich traditions and ancient knowledge by exploring 50 unforgettable experiences crafted by Indigenous communities. These immersive encounters invite you to encounter diverse cultures and landscapes while supporting a more thoughtful and sustainable approach to travel…

In the ever-evolving world of travel, few movements have captured our attention and ignited our passion like the rise of Indigenous tourism. This growing sector is about far more than just visiting breathtaking destinations or ticking off landmarks from a bucket list. It’s about connecting with the very soul of a place through its First Nations, their traditions and the unique stories that have shaped their cultures for millennia.

At Wanderlust, we’ve long believed in the power of travel to transform both visitors and the places they explore. However, we’re also acutely aware that not all forms of tourism have been beneficial. Indigenous communities, in particular, have often found themselves marginalised, their cultures exploited or packaged in ways that strip away authenticity.

But today, there’s a shift underway: a reclamation of narratives by Indigenous peoples themselves, who are welcoming visitors on their own terms and sharing their heritage in ways that empower their communities.

It is this spirit of empowerment and cultural preservation that inspired The Origin List, our first-ever compilation of 50 standout Indigenous tourism experiences from across the globe. This list is a celebration of Indigenous-led tourism, highlighting immersive, authentic experiences that honour the deep cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples and offer travellers the opportunity to engage in meaningful ways.

So, what is Indigenous tourism?

It’s a form of travel where Indigenous communities take the lead in creating experiences that reflect their traditions, landscapes and ways of life. It’s a chance for travellers to not just see a place, but to truly understand it by hearing stories passed down through the generations, learning traditional crafts, tasting ancestral foods and participating in sacred ceremonies. It is, in essence, a journey of connection; one that fosters respect, understanding and cultural appreciation.

The Origin List isn’t just about pointing travellers to extraordinary destinations; it’s about recognising the significance of

Indigenous voices in shaping those journeys. From the jungles of the Amazon to the vast deserts of Namibia, and from the icy expanses of Greenland to the sun-soaked islands of Fiji, these 50 experiences offer a window into the unique worldviews and traditions of Indigenous peoples around the globe.

But why create this list now? As the world grapples with the impacts of overtourism, the travel industry is at a crossroads. Many popular destinations have been loved to the point of degradation, and the homogenisation of travel has made it harder for travellers to have truly authentic experiences. Indigenous tourism offers a compelling alternative by emphasising sustainability, community and respect for local cultures. It invites travellers to step off the beaten path and engage with places in a way that benefits both the traveller and the host.

At Wanderlust, we champion travel as a force for good. By supporting Indigenous-led tourism initiatives, we can help preserve cultural heritage, create economic opportunities for local communities and foster a deeper

From 3km-wide waterfalls to opera houses in the jungle, we plot the best routes to experience Brazil’s wildlife, history, cities and Indigenous cultures

Words Alex Robinson

Lose yourself in the vast wetland habitats of the Pantanal and Brazil’s eccentric capital

Best for: Wildlife, light adventure, river snorkelling and Brazilian architecture.

Why go? To overwhelm your senses in South America’s goldstandard wildlife destination, to swim in crystal-clear rivers and to feel tiny next to Oscar Niemeyer’s monumental buildings.

Route: Cuiabá; the Pantanal; Chapada dos Guimarães; Nobres and Brasília.

TV shows by the dozen have showcased Africa’s lion-teeming Serengeti plains. But no less wonderful or less wildlife-filled is Brazil’s Pantanal. This UNESCO-listed, Ramsar-protected wetland is larger even than Great Britain. It’s where to go if you really want to stand a chance of seeing jaguars in the wild.Along the way, you’ll find giant anteaters, rheas – South America’s ostrich-equivalent –plenty of other cats (from the moggy-sized jaguarundi to the labrador-sized ocelot) and wild animals you’ve probably never heard of.

The birdwatching is superb, with raptors on every other fence post, metre-long indigo-blue macaws nesting in the ipê trees and myriad waterbirds – from man-sized jabiru storks to tiny hummingbirds.There are two main airport entry points – Campo Grande

early morning and late afternoon, when the nocturnal animals (like cats and anteaters) are still active.The temperature is cooler at this time, and the Pantanal looks at its most beautiful, with the sun on the horizon, red as a blood orange, silhouetting branchperched hawks and wading herons.

Pantanal horses are smaller than the European varieties; they are docile, well treated, well fed and used to carrying tourists, so you won’t need any previous riding experience to enjoy a horse safari.

in the southern Pantanal (where transfers into the Pantanal are pricey) and Cuiabá in the north (where prices are lower but visitor numbers are heavier). Both are small state capitals – of Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso respectively. There’s little to keep you in their urbanity, so head directly from the airport to one of the working fazenda ranch houses, which serve as bases for exploring the wild.

In both its northern and the southern reaches, the Pantanal is fringed with low tabletop mountains, where the ancient, rain-worn rock leaches almost no sediment. As a result, the rivers that run off it are as clear as mineral water.They also offer superb snorkelling. Use the city of Nobres (in the north) or the town of Bonito (in the south) as access points.

The Pantanal has two seasons: the dry season between April and October and the wet from November to March. Both are great for extraordinary photographs, but it’s during the dry season when you’ll see the most animals.This is when the Pantanal’s seasonally flooded lakes and gallery forests shrink and the wetlands become a landscape of open savannahs dotted with lakes and cut by meandering rivers and stands of low cerrado woodlands pinked with trumpet trees and purpled with jacaranda. In dry season, you’ll see plenty of animals from the pool at your fazenda or on the paths connecting your bungalow and the main ranch house, but it’s the hikes, 4WD rides and horse safaris that get you into the heart of it all.

Pantaneiro cowboys still access the wilds on horseback, and this is one of the best ways to penetrate the wilder stands of woodland and wetland, cover a decent distance and chance upon animals that are wary of the noise of 4WDs.The best times for a ride are

Colours of the Pantanal (this page; clockwise from top) The endangered Lear’s macaw; the glittering-bellied emerald hummingbird forages for nectar on flowering plants; the giant anteater can weigh up to 50kg; (opposite page; clockwise from top left) brycon can jump out of the water to pluck fruit and seeds from low-hanging trees; conservation projects allow people to see wild jaguars at the Encontro das Águas State Park; the Modernist 7,000 sqm Alvorada Palace in Brasília was built in just two years

“People forget that Central Brazil is where the Pantanal meets the Amazon. There are so many animals unique to this transition zone. I particularly love heading into our forests in the early morning to spot the ultra-rare Tapajós saki, which is only found in the buriti palm forests around the Tapajós and Madeira river tributaries. They’re such gentle animals – and a key disperser of rainforest seeds.”

Raquel Zanchet, executive director of the Jardim da Amazônia Lodge conservation project (jardimamazonia.com)

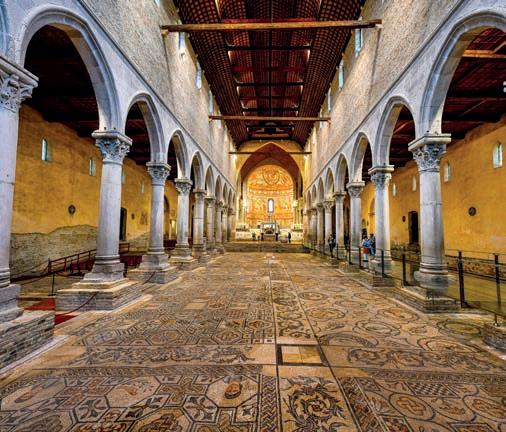

Italy’s north-eastern jewel is too often overlooked for its Venetian neighbour. But while the latter wrestles with overtourism, this former Habsburg outpost offers a welcome antidote, writes Kiki Deere

Comfortably tucked away in Italy’s north-eastern corner, bordering Austria to the north and Slovenia to the east, Friuli Venezia Giulia is all too often forgotten in favour of its neighbouring region,Veneto.Yet venture here and you’ll discover an amalgamation of cultures and landscapes that make this unlike anywhere else in Italy. This is a place of magnificent Roman riches,Venetian architecture, Habsburg cities, marshy lagoons, snowy mountains, karst terrain and rolling vineyard landscapes.

The Romans were quick to acknowledge the region’s strategic location at the crossroads of East and West, building one of the Empire’s foremost outposts at Aquileia. The town’s Basilica harbours exquisite Roman finds, not least an early Christian mosaic floor that is the largest – and oldest – surviving example of its kind in the Western world.

Beautiful Udine served as one of theVenetian Republic’s most important cities. As a result, many of its porticoed loggias and elegant palazzi bear the image of the winged lion of St Mark – the symbol of the Republic. Art abounds here, and Udine is dubbed the ‘Città del Tiepolo’ for its spectacular Rococo fresco cycles by the

18th-century painter Giovanni BattistaTiepolo, which are among the artist’s most significant. Regional capitalTrieste was the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s first port city, and once imported tonnes of coffee to serveVienna’s cafés (even today, it still imports 40% of Italy’s coffee). It became a city of grand boulevards and elegant Neoclassical cafés, where writers, intellectuals and artists gathered to exchange ideas. The border town of Gorizia, too, was long under the thumb of the Habsburgs, and a distinctly Central European feel still pervades its streets today.

Spend a few days exploring the region and you’ll soon discover a cuisine that is as varied as its cultural offerings, with rich culinary traditions marrying Italian, Austrian, Slovene and Venetian flavours.

The region’s topography is no less diverse. The limestone karst plateau stretches into Slovenia, dotted with secluded beaches and offering no shortage of trekking opportunities. To the north are the jagged Dolomites as well as the Carnic and Julian Alps, playgrounds for outdoor enthusiasts, while the central plains run down to the Adriatic, where thatched fishermen’s dwellings dot lagoons that serve as important wintering grounds for birds.

“Overlooking the Gulf of Trieste, the Castello di Miramare is a highlight, surrounded by lush gardens offering breathtaking sea views. You can also take in glorious vistas as you walk the Rilke Trail, where cliffs plunge into the Adriatic. And make sure you experience an osmiza in the Karst, savouring local wines and homemade charcuterie. Discover the medieval streets of Cividale, a UNESCO World Heritage site, hike the majestic peaks of the Carnic Alps and learn about creativity at the ITS Arcademy – Museum of Art in Fashion in Trieste. History, nature and tradition intertwine here at every corner.”

Barbara Franchin, director of the ITS Arcademy Foundation (itsweb.org/its-arcademy/)

Next issue on sale 30 January 2025

Our editors pick the destinations that deserve the spotlight in the year ahead

The Three Guianas Capitals of Culture 2025 The Great Gatsby’s USA Indigenous British Columbia The Natural Wonders of Saint Lucia Northern Namibia