010 Re:Discovery

020 Obituary: Gordon Parks

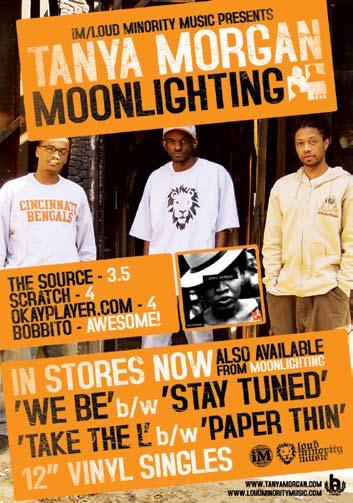

022 Tanya Morgan is a hip-hop group

024 The untold saga of J Rock’s Streetwize 032 Thes One’s matrimonial mixtape

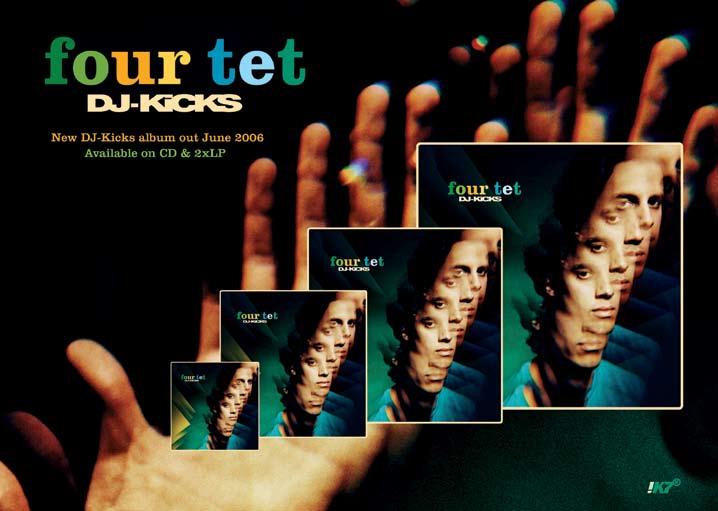

038 Four Tet selects eclectic

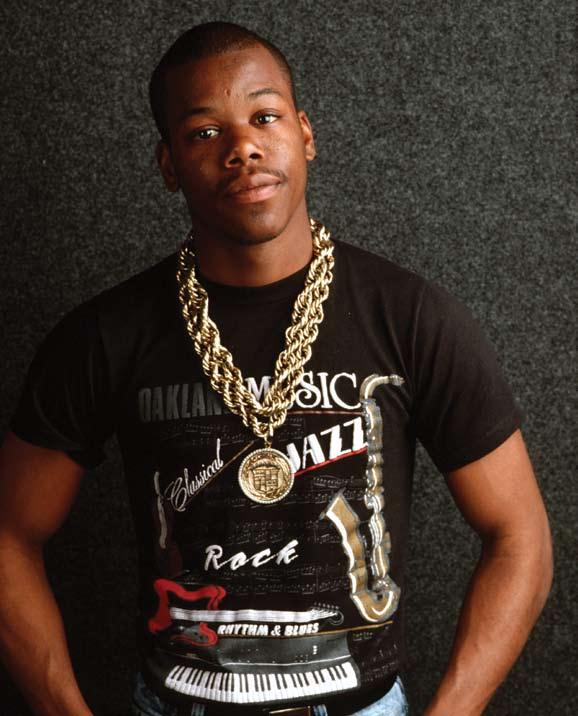

044 Bay Area hip-hop and the rise of hyphy

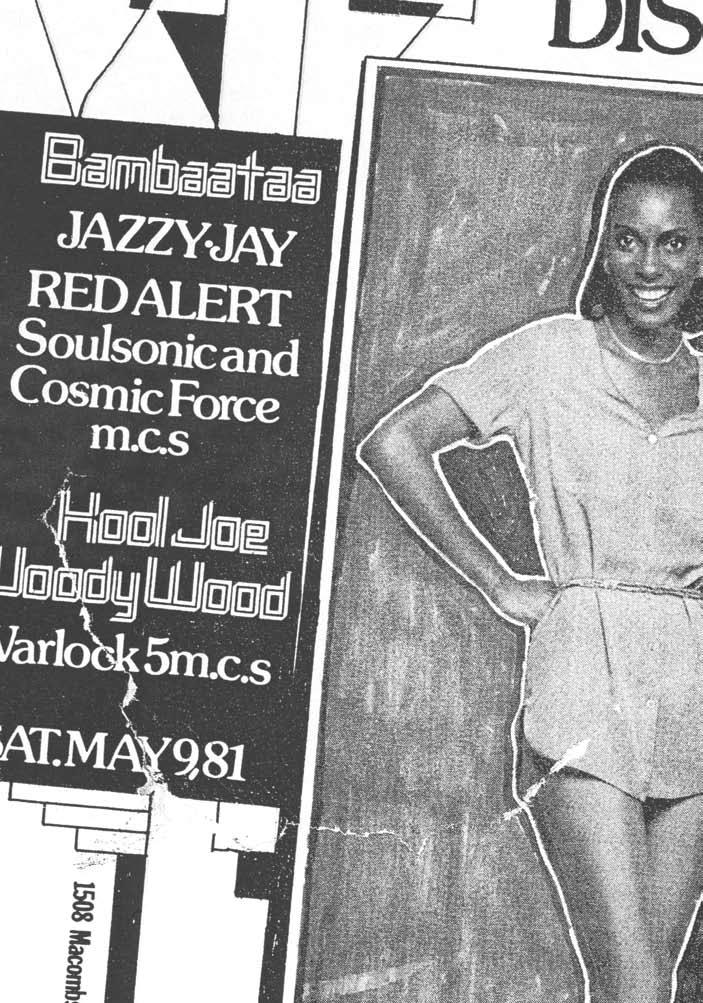

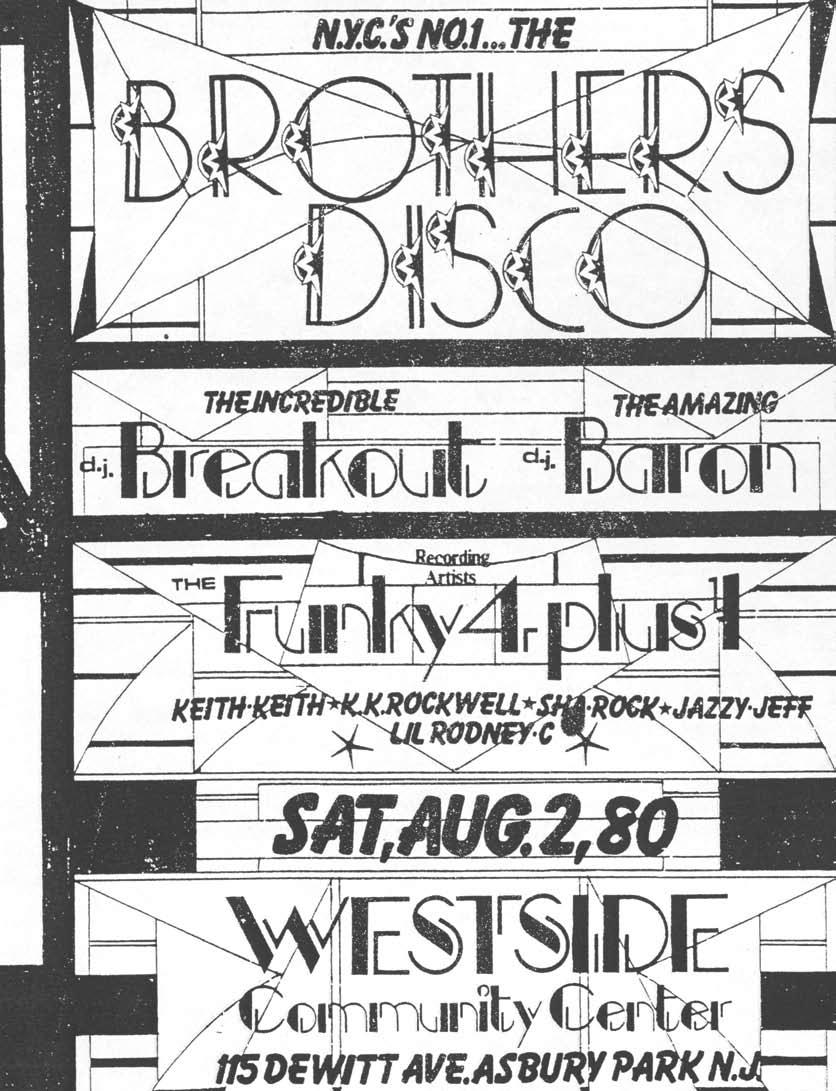

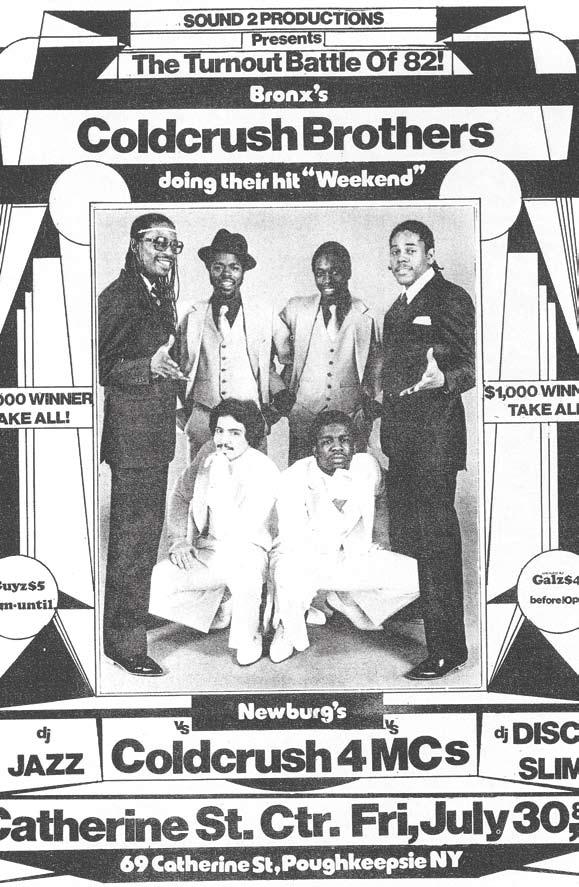

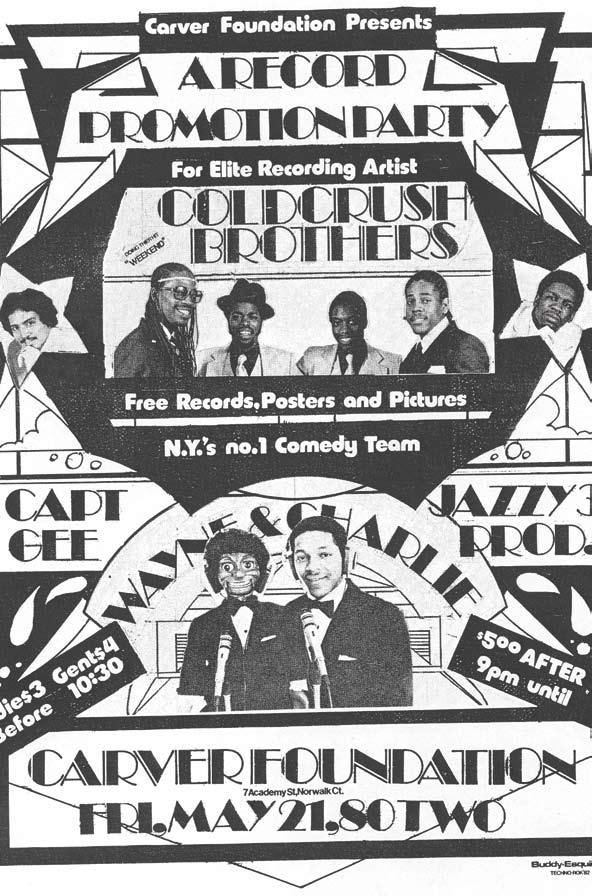

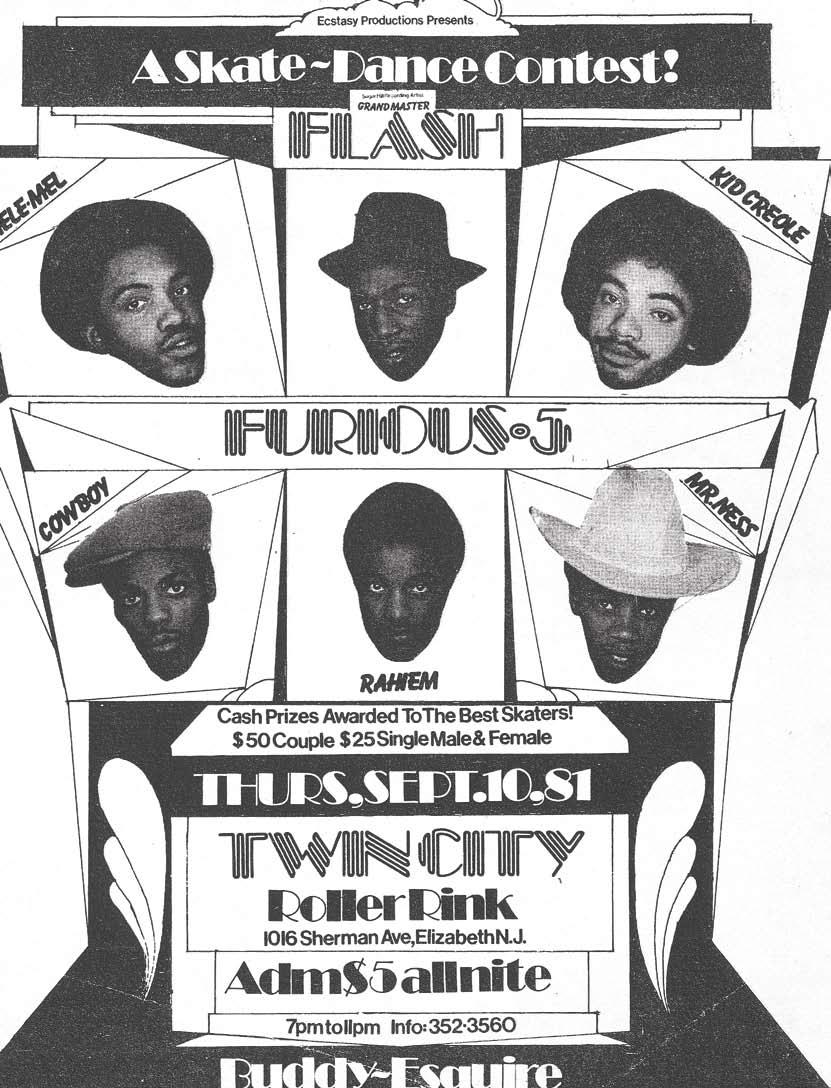

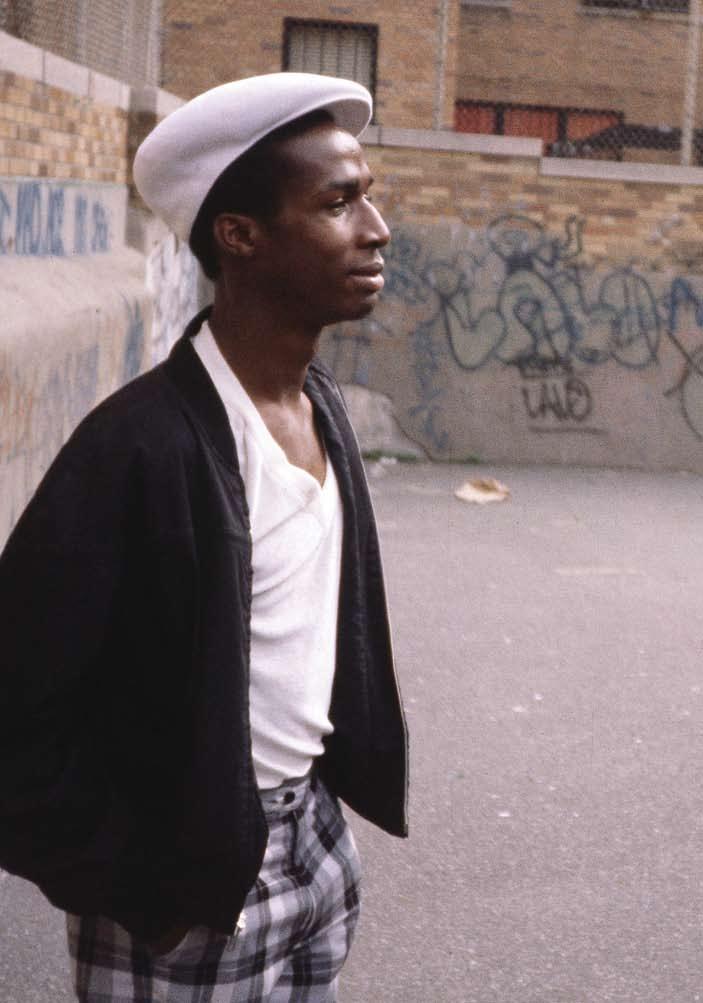

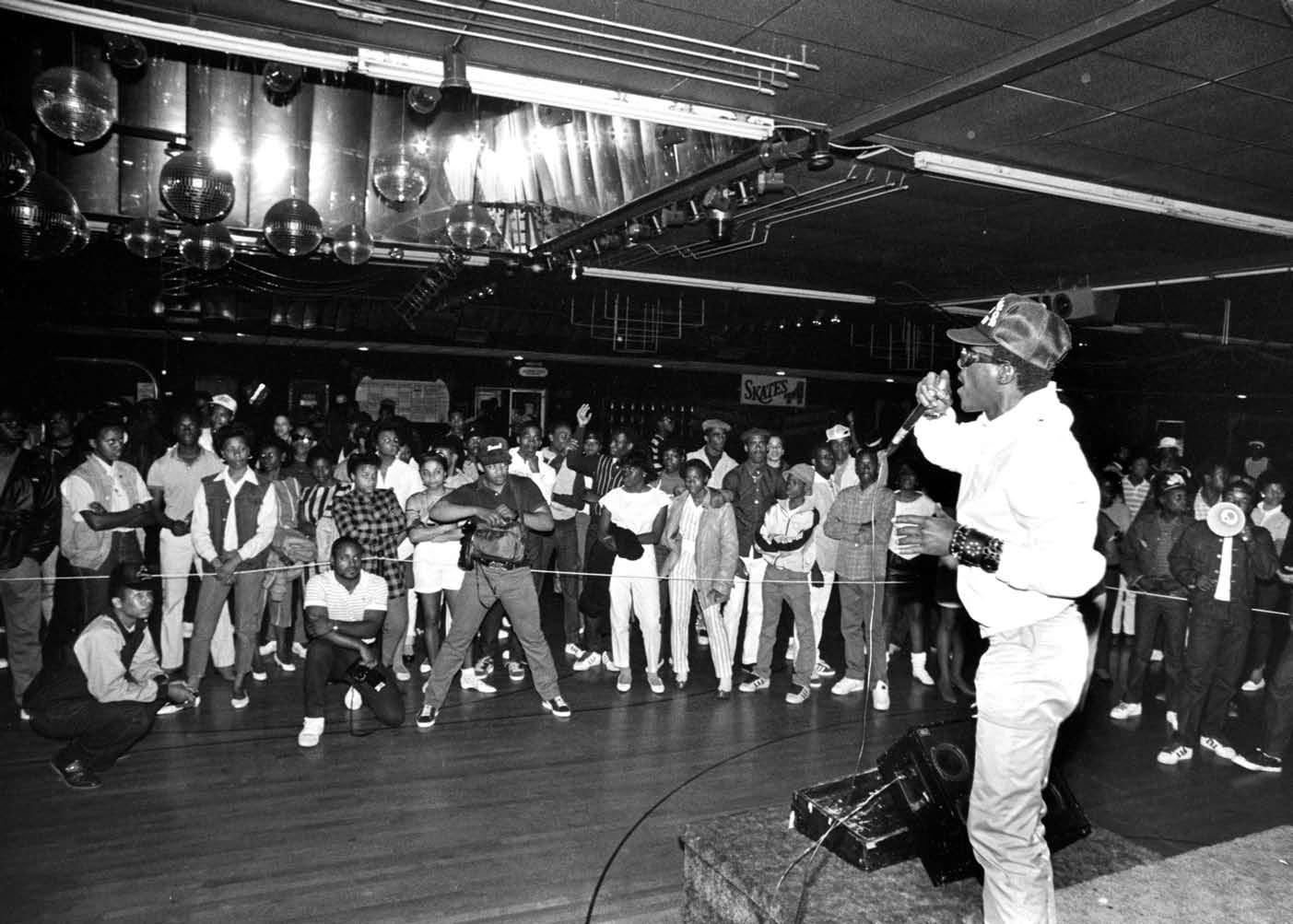

050 Buddy Esquire and the art of the show

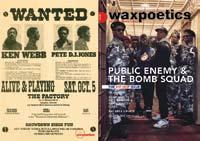

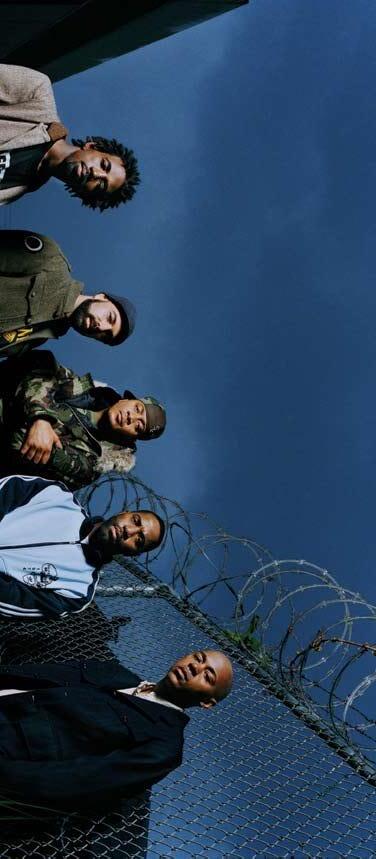

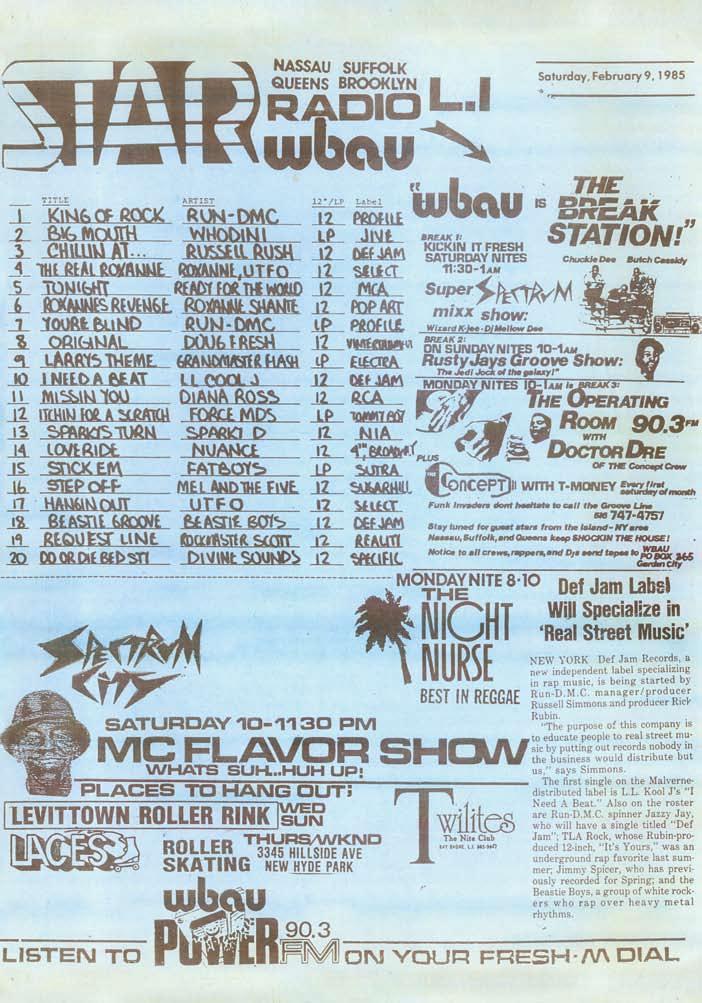

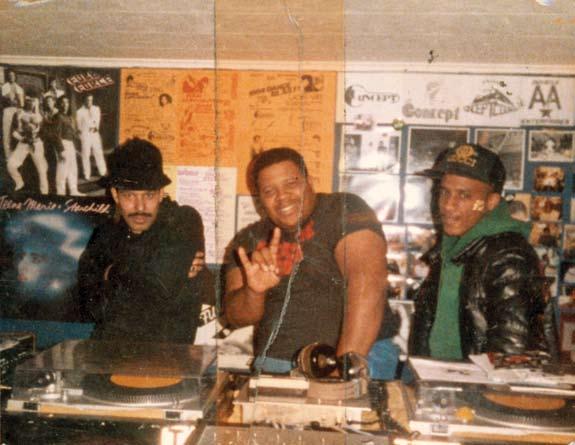

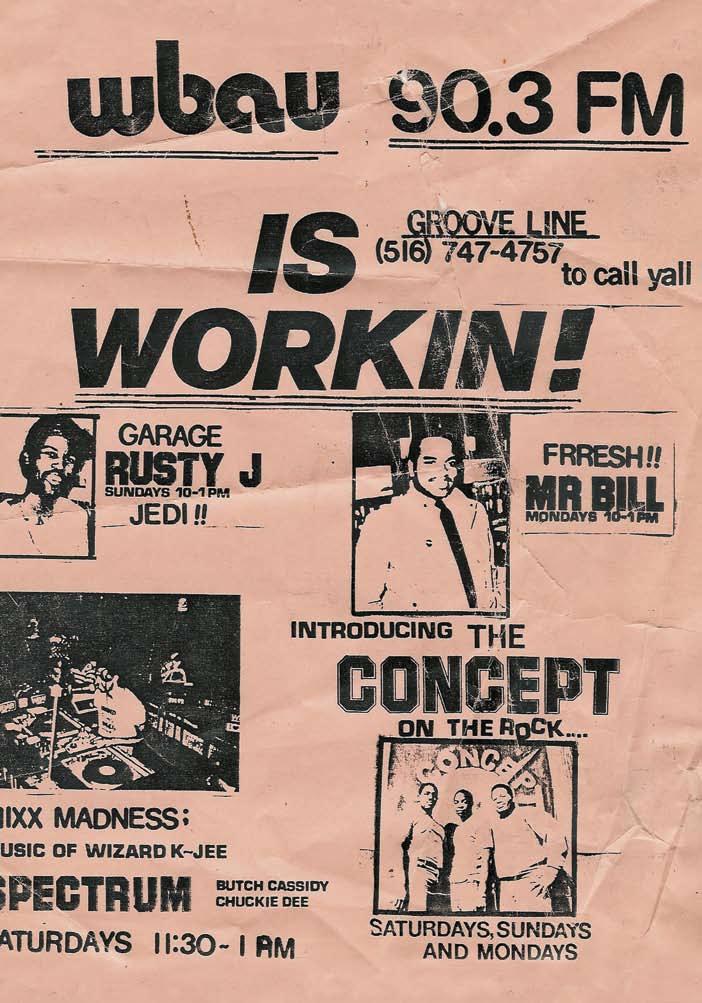

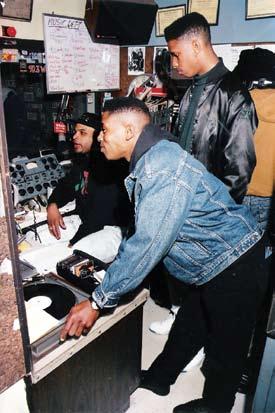

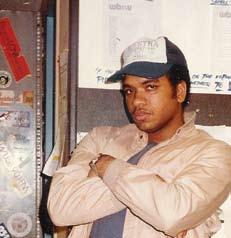

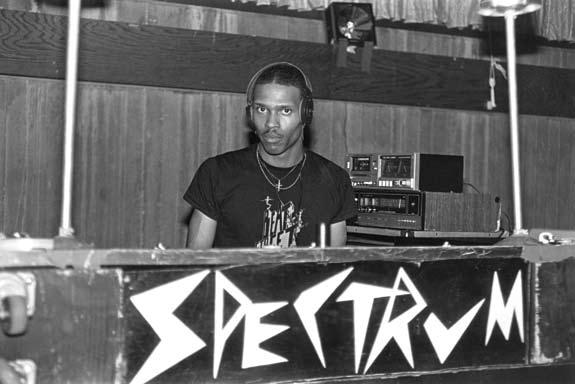

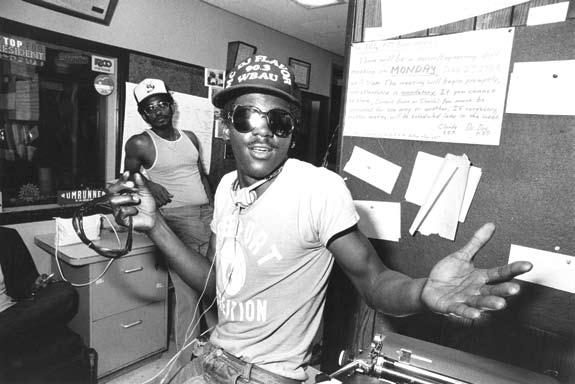

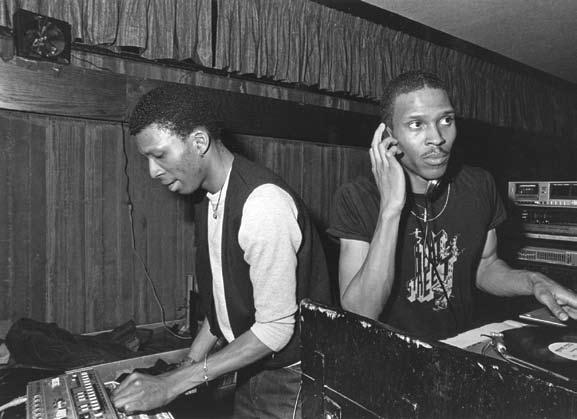

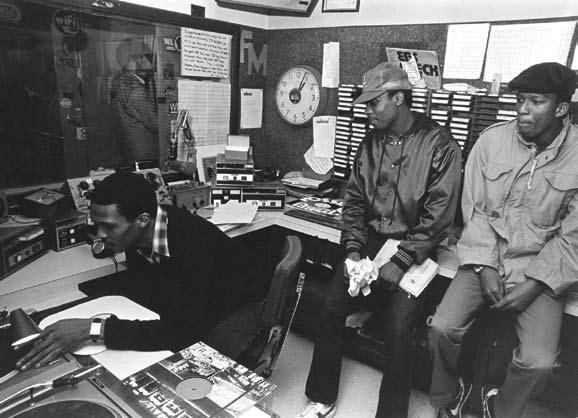

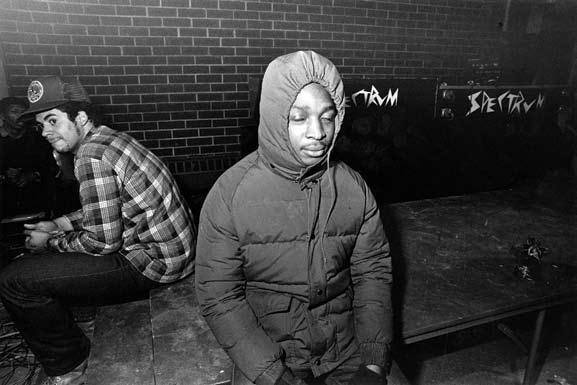

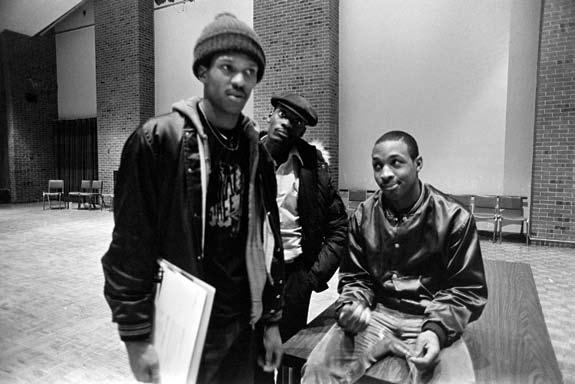

060 WBAU put Strong Island on the map

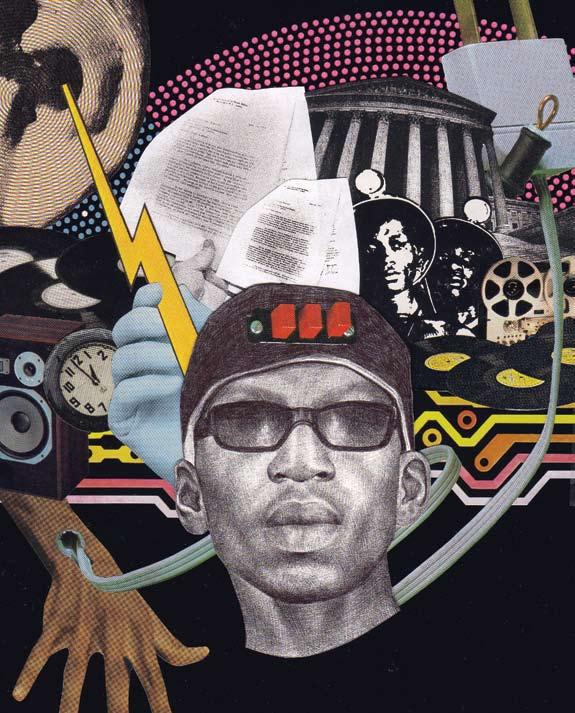

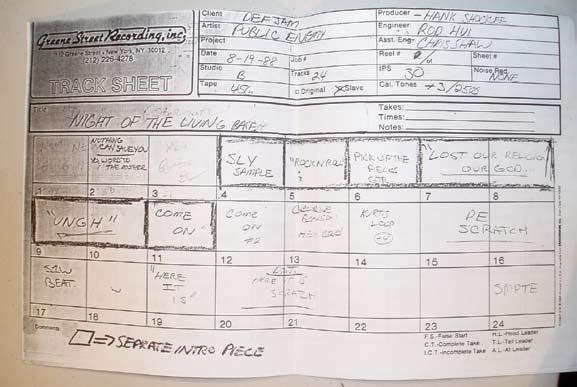

070 Academic Archive: Hank Shocklee

076 12×12: The Breaks

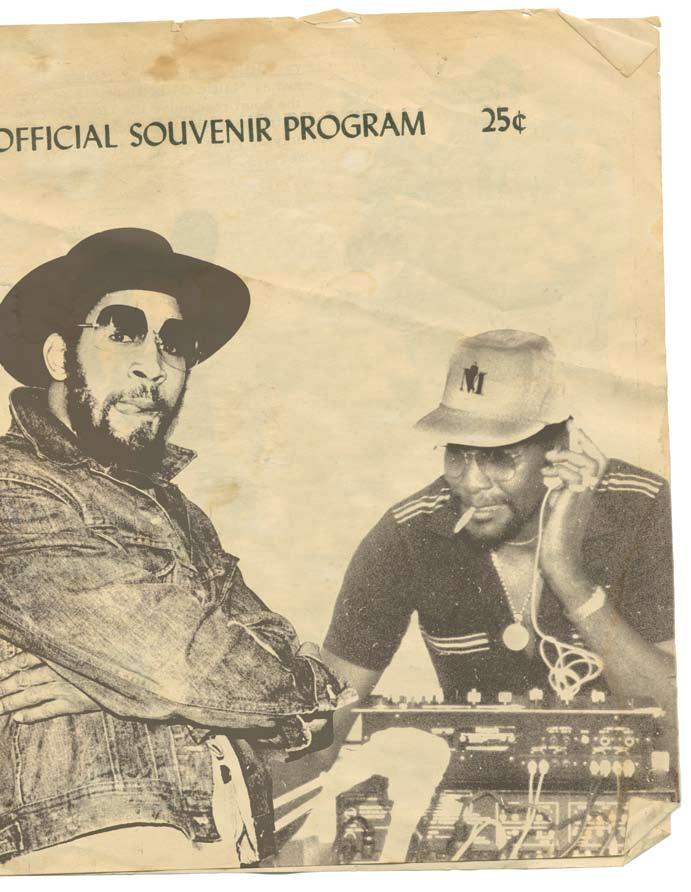

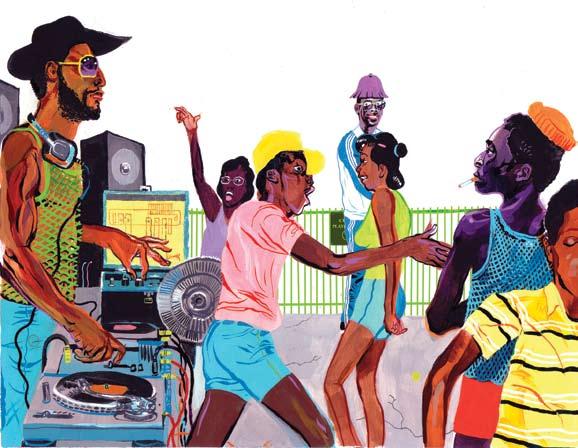

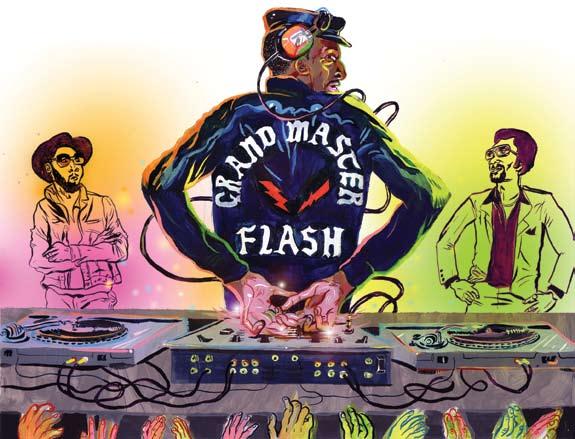

084 Kool DJ Herc vs. Pete DJ Jones

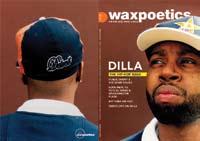

098 Jay Dee Remembered 112 Questlove’s Life Lessons with Dilla 118 An oral History of the Bomb Squad 138 Audio Heritage

Published by Wax Poetics

Editor-in-Chief Andre Torres

Editor Brian DiGenti

Creative Director Kevin DeBernardi

Marketing Director

Contributing Editors

Dennis Coxen

Dante Carfagna

John Paul Jones Andrew Mason

Contributing Photo Editor B+

Sales and Marketing Manager

Accounts Manager

Michael Coxen

Joy DiGenti

Copy Editor Tom McClure

Editorial Intern James Steiner

Design Interns Sean Manchee, David Wakasa

Marketing Interns Alex Biedermann, Ed Ntiri, Dominic Wagner

Contributing Writers Joe Allen, Brandon Burke, Robbie Busch, Anaïs Carayon, Dante Carfagna, Joe Keilch, Anna Klafter, Jason Lapeyre, Lucas MacFadden, George Mahood, Jeff Mao, Andrew Mason, Mark McCord, Ed Ntiri, Mark Randolph, Ronnie Reese, Jesse Serwer, Paul Sullivan, Ahmir Thompson, Dave Tompkins

Contributing Photographers Charlie Ahearn, Harry Allen, B+, Joe Conzo, Rob Ditcher, Glen E. Friedman, Richard Louissaint, Paul Sullivan

Contributing Artists James Blagden, Luke Rocha

Printed by MGM Printing Group

Distributed by Indy Press Newsstand Services

DJ Jones flyer, courtesy of Pete Jones (and thanks to Elemental for providing image). Dilla Cover: Photographs by B+.

Wax Poetics, Inc.

45 Main Street, Suite 311, Brooklyn, NY 11201

Phone: 866-999-4WAX or 718-624-5696, fax: 718-624-5695, email info@waxpoetics.com Website www.waxpoetics.com

To advertise contact advertising@waxpoetics.com or call 718.644.2244.

To sell Wax Poetics contact direct_sales@waxpoetics.com or Diane Hakimi of Indy Press Newsstand Services at 415-643-0161 ext. 123, diane@indypress.org.

To subscribe contact subscriptions@waxpoetics.com or visit waxpoetics.com/subscribe.

To contribute contact editorial@waxpoetics.com.

Send promotional vinyl albums and material to the above address.

Wax Poetics is produced on a Macintosh using Adobe software.

© 2006 Wax Poetics, Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication without prior written consent is prohibited. ISSN 1537-8241

I got so much trouble on my mind I refuse to lose –Public Enemy “Welcome to the Terrordome”

There’s a great episode of The Mike Douglas Show from 1974 with Sly Stone. And as if Sly wasn’t enough to make it a classic, Muhammad Ali is also a guest. To stir the pot, Douglas adds Rep. Wayne L. Hays, a White democratic from Ohio, and right off the bat Ali starts sticking it to him. Hays just can’t understand why Ali’s so angry. Sly plays it cool and actually tries to mediate when things get heated, but Ali’s not having it. Sly’s trying to interrupt Ali at one point, and Ali starts giving him the brush off. Sly’s no punk, though, and tells Ali to get his hand out of his face. I begin realizing that television today is nothing like it was thirty years ago. Even in a world of “reality”driven drivel, everything is so scripted that we’re robbed of genuine moments like this. But just as I’m thinking that it couldn’t get any better, Ali looks at him and says, “Let’s not be niggers and fools in front of White people.” Did he really just say that? Several hundred viewings later, it still holds up as was one of the illest things I’ve ever seen on TV.

I’ve been thinking about that quote a lot recently. It’s as if Ali’s greatest fears have come to life, because if you look at TV, you’ll see a whole lot of Us being niggers and fools in front of White people. But who the hell cares what White people think, anyway? Cosby was right, we don’t need to be worried what they think as much as what we think. But we’re not thinking. So just days after T.I.’s van got shot up, and only hours after one of our writers finished an interview with him, I sit writing this in a time of crisis. So in this first ever all-hip-hop issue, Wax Poe T ics looks back to a time when a group like Public Enemy and the Bomb Squad was running shit, and wonder what the hell happened? We’re eating a little better, but are we really making any progress? I think it’s time for some revolutionary music.

I remember the first time I heard It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back and realized that my life would never be the same. That album was pure inspiration. For a dude living in a bass-obsessed Florida drenched in Luke Skyywalker, it was refreshing to hear some cats from NY dropping knowledge. But that was the thing about ’87, PE could co-exist along side Luke and it was all good. I guess it wouldn’t have taken Nostradamus to figure out that almost twenty years later, it would be Luke’s influence being felt strongest across this all too depressing hip-hop landscape. But don’t get me wrong, I fucks wit Uncle Luke, so that’s not really the issue. The biggest problem today is that there’s no balance in the music being shoved at us. If Luke’s presence is still felt, where’s PE’s? Is it in Kanye’s remark that,

“Bush don’t like Black people?” And if that’s the case, you mean to tell me with all these thugs out here, Kanye’s the only dude with balls enough to say some challenging shit like that? Where are the next Chuck D, X-Clan (R i P Professor X), and KRS? Truth be told, I’m embarrassed by most of this shit being passed off as hip-hop right now. I like to party more than the next man, but, damn, some of this garbage these niggas are spitting got me cringing. And just when I’m thinking we’ve hit a brick wall, Jay Dee offers his swan song, Donuts, and I realize all hope’s not lost. This album is inspirational, inspired. When you think that the dude was in a hospital bed making a lot of these beats, you realize it was something that he didn’t have a choice in. He had to do it, because it was who he was. Not what he wanted to be, or thought it would be cool to do because he could stack some paper. He did it because it made him feel good. How many of these cats out here now can say that? And then the more I think about it, I begin to realize that maybe this is revolutionary music. In today’s rap climate, where all dudes know is “monkey see monkey do,” it’s rare to find someone just doing their own thing. For Dilla, it was about the subtlety of it all; he didn’t need to bang you over the head. So one of the many things cats can learn from his passing is that being a legend doesn’t have shit to do with going platinum or having your own clothing company. Legendary status comes from respect, and that’s something you can’t fake.

Somewhere in all of the bullshit, I realize this may be our way out of this mess. If we can’t bang ’em over the head with revolutionary music anymore, and we don’t want to be niggers and fools, then maybe it’s somehow about being subtle. Because all the sex, drugs, and murder raps ain’t all that shocking anymore. What is shocking is when someone can make a good record and not have to go that route. These cats that were “hot” a minute ago ain’t staying all that hot for long anymore. Andy Warhol wasn’t lying, but those fifteen minutes are getting shorter by the day. It’s about being subtle and staying true to your vision. Showing young kids that we don’t have to be niggers and fools, now that’s revolutionary. Because with the birth of my second son, Nigel, who’s only three weeks old now (Love you, Angie), I need to be sure that he’s inspired too.

An undeniable percentage of old U.K. rap isn’t worth the plastic it’s pressed on, but this sturdy 1989 12-inch—produced by never-made-it-big North Londoners Fresh Ski and Mo Rock, whose records are experiencing a long-awaited paroxysm of interest—withstands comparison to the upper tiers of aging obscurities from both sides of the Atlantic. The crew is perhaps best known for “Talking Pays” b/w “ Pick Up On This,” the incredible third and final single to emerge on Tuff Groove (TUFF 003), a label bankrolled by U.K. hip-hop pioneer Ricky Rennalls (of Ricky and the Mutations, and Mutant Rockers fame). The label was also home to flawless 12-inchers by Jus Badd (TUFF 001) and the Dynamic MC’s (TUFF 002). Fresh Ski and Mo Rock followed up “Talking Pays” by issuing a trio of stingers on their own imprint, Conscious Music: Atorie came first, then Logic Control M.C.’s (CON-002, produced by Secret Service Productions), and lastly the group’s own six-track mini-album (CON-003).

Artist: Atorie

Record: “It’s My Time” b/w “Mo Rock: Peace of Mind”

Label: Conscious Music CON-001

Release: 1989

The Atorie 12-inch is a personal fa vorite of mine from the era, because it’s so unforced and natural: simple ingredi ents, perfectly combined. “Apache” and “Keep on Dancing” form the bedrock of “It’s My Time,” but avoid sounding tired, thanks to original drum programming, tough stabs, Mo Rock’s sparse but funky cuts, and a sustained minor-key horn sample that gives the whole thing a unique, ahead-of-its-time jazz edge. Atorie is a confident and effortless MC who lets the song’s geographical origins slip out via some irrefutable Londonisms (“riss” for “risk,” as Mell’O would enounce), despite her American twang. The flip is a mid-tempo Mo Rock instrumental somewhat like a lost Wildstyle beat, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with that.

Classics by the likes of London Posse, Hijack, Demon Boyz, and Hardnoise have always been held in high regard, while Aroe’s Crown Jewels mix-CD (the Hear No Evil of this stuff) is a good place to hear a selection of lesser-knowns, and will have mobilized many collectors into high pursuit. The day of reckoning is in arrears for overlooked releases like Atorie’s; it’s their time. . –George Mahood

Reginald Hobdy used to carry a mic in his shaving kit. He called the shaving kit a coffin and the mic a vampire. Sometimes, he plugged into parties, rapped about the “synchronized transmission” of his AK-G-120E, taped it, forgot tape, heard tape in someone’s radio months later and demanded to know who’d cloned his bicuspids. Um—that’s you, Silver Fox—named after a German sports coupe. Some might’ve thought this Drac ditty bag was odd, or that Fox had spent too much time in darkest Alaska (true story), but who’s to question the only guy Kool Moe Dee feared?—the one who helped LL write “I Need a Beat” and would be cited by Kool G Rap as the “futuristic cat who G Rap and LL got their style from.”

Artist: Fantasy Three

Record: “Biters in the City”

Label: CCL Records

Release: 1983

It was Tito and Master OC of the Fearless Four who assembled Fox, Charlie Rock, and Larry Mack as the Fantasy Three, a group snubbed by rap history and reenactments despite creating two records in ’83 that sent foes home with their fake varmint tails between their legs. Fantasy Three’s first single, “It’s Your Rock,” has been sampled by Large Professor, Pete Rock, Three 6 Mafia, and most ibidly, Crash Crew, who, at Sugar Hill’s behest, Xeroxed the beat for “On the Radio.” Thank them for pissing off Fantasy Three enough to do “Biters in the City,” a Webo-footed electro 12, which the group itself thought too “creative,” too fast.

Sampled by the Beatnuts, the instrumental was created by the edit supernauts responsible for “It’s Your Rock,” including Aldo Marin (producer of “Al-Naafiysh” the first Muslim Vocoder jam), Master OC, Dave Ogrin, and Pumpkin, a near deaf drummer with customized headphones (REVERB) who apparently died with all the secrets (i.e., record next to toilet) and left us with a Vocoder crooning “Myyyyyylar,” an asthmatic vacuum cleaner, and some spliced babble from “It’s Your Rock.” Instrumental my ass.

Then the “Transparent Radiation” part—a bombinating (real word) Vocoder that could be Silver Fox chased by an Inuit throat sled. Or that clone drone at the end of Invasion of the Body Snatchers—when the POV zooms into Donald Sutherland’s tonsils. Nothing screams biter like a freshly podded DNA mimeo. . –Dave Tompkins

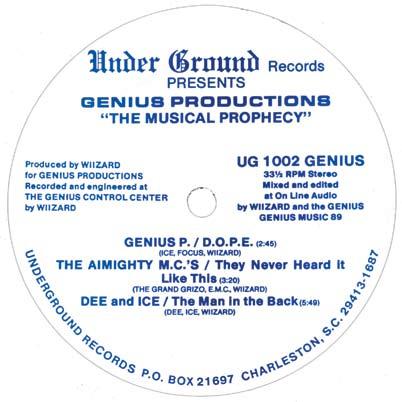

Artist: Genius Productions

Record: The Musical Prophecy

Label: Underground 1002

Release: 1989

The enigmatic Wiizard produced the six tracks on this sampler EP, and he must have been the first dude in South Carolina with access to the entire Ultimate Breaks and Beats library. Or maybe he just had a cousin from New York City that came down and visited him in Charleston one summer, records under arm. This is first-order hip-hop from the fabled silver age, which just as easily could have read “Bronx, NY” on the lower label. What elevates this above other random obscuros from the era is the foggy and extremely perplexing mix, a combination of extraterrestrial quad and distorted, mind-creeper scratching. It’s obvious that the bass and cuts were later overdubbed on top of the already intricate instrumental grooves, but someone was obviously baked during this process. Wiizard tries to squeeze every break known to man (in 1989) into each song, letting his many guest MCs drop quotables such as, “We use gunpowder to brush our teeth, eat sticks of dynamite because they taste sweet.” On “They Never Heard It Like This,” the “Assembly Line” drums get wrapped around the “Blow Your Head” synth to great effect—even more enjoyable when the 808 drops and blows all the other sounds out of your stereo and onto the floor in front of your speakers. Dee and Ice are represented on the final, and perhaps best, track of the EP, with the Wiizard turning the Trickeration scratch into aural wood chips that will severely enhance your burgeoning and carefully cultivated mind garden. And to add insult to injury, the track was additionally released as its own 12-inch. As the rest of the U.S. slowly begins to give up its late ’80s hip-hop ghosts, South Carolina is starting to emerge as a real contender for the non-NY Rap Champ crown, with further records by Major T, Prince DBL and Rocking Rob, and Break Down Academy showing and most certainly proving. . –Dante Carfagna

is on

Handpicked gems tell the story of one of the greatest record labels of all time.

Artist: Section 25

Record: “Looking from a Hilltop”

Label: Factory (FAC 108 A)

Release: U.K., 1984

You know those records you hear DJs play, but you never can find out what they are? That was this record for me growing up. When I would describe it to DJs, they would give me pieces of evidence like “the label is silver” or “the title is something like ‘Shouting from a Mountain’ ” or “it’s an overseas record.” I recently put the word out a different way. I decided to do an homage to the elusive beat for a song on my album to see what comes back. Randomly enough, I was mastering my album with local DJ/producer/artist John Tejada, who said, “Wow, you remade Section 25.” I proceeded to interrogate. Turns out it’s the dub version of a new-wave record called “Looking from a Hilltop” by a group called Section 25. This group formed as a trio in 1978 and got signed by indie Britpop giant Factory Records in 1979. Always overshadowed by label mates Joy Division, they never quite got the recognition they deserved until they released “Hilltop” in 1984. With its Roland 303 and backwards echoing snare intro, the remix version crossed over to the New York club scene and Black radio stations in Chicago. After DJs got the word, it made its way into mixes by the likes of New York’s Latin Rascals and L.A.’s Uncle Jamm’s Army. Not too long after that, Dr. Dre used it in a song called “Telesis” and Egyptian Lover remade the intro for his song “On the Nile.” It seems that this record’s influence resurfaces every few years. In the early ’90s, a few electronic artists had sampled it, and today an extensive CD collection on Section 25 has been released. If you like today’s alternative sound à la She Wants Revenge, then you’ll love this stuff. . –Lucas MacFadden

A barrage of Centipedes drop through the magic mushrooms and attack the dubbed-out bunker of electro over a frenzy of hand claps and lead-footed drum-machine stabs while a carnival of souls cheer from a Bambaataa-less pit of reverb. TWR were some Boston boys with reverb, and they weren’t going to let you forget it. By putting the dub-a-licious “Those Who Rock” as the first track on the 12-inch, they beamed out an Atari Force transmission of bombastic proportions to let us know that the instrumental was key. As they tell us later, they were “Using def-ill equipment, funky-fresh high tech.” The video game sound effects, a mix of Centipede and Galaga, that lead into the TWR war room were synched up with enough stuttering drum programming to create a shoot-’em-up arcade fever dream where the echoing voice of the Wizard of Rockin’ shouts out to his homeboys, the Writer of Rhymes and DJ Krush. His mission was to keep reminding the listener that they are “Those Who Rock,” and he does so till the bitter end when a swarm of insects swallows him up.

Artist: TWR Production

Record: “Those Who Rock/ Coolin’/ Stupid Deff!”

Label: TWR Production

Release: circa 1986

TWR decided that level two was where they needed to start rapping. On the second track, “Coolin’,” they took the drum pattern from the first track, but replaced the sound effects with the simple vocal sample “Coolin’ ” and repeated it with an itchy trigger-finger fanaticism. They built the track on overdubbed variations of that one word, pitched up and down to create a choral bed. Then the Wizard of Rockin’ was free to jump all over it as he used the same technique to double himself on the two verses. Yeah, only two. And no chorus to speak of. They were out to rock and didn’t want the fussy words of rap to get in their way. With the B-side, “Stupid Deff!,” TWR show their hand. The repeated hi-hat and screeching-wheel scratch attack was cribbed straight out of the Def Jam playbook. They eschew pesky choruses for a display of turntablism heavily influenced by the bottom of a cough syrup bottle and a broken Trak-Ball controller. After two short verses, DJ Krush takes over to scratch and claw his way over the wall of sound that they’d built for themselves, leaving nothing in his wake but the mysteries hidden behind the break-dancing robot and brick wall that grace the label of this old school curiosity. . –Robbie Busch

by Mark Randolph

The recent passing of Gordon Parks on March 7, 2006, at the age of ninety-three made me wonder why the general public had little or no knowledge of his achievements. Could it be a sign of the times? Could race be a factor? Or could it possibly be America’s lack of interest in anyone or anything of relevant cultural significance? Perhaps, I can remedy this injustice and shed some light, posthumously, on an American icon whose accomplishments transcended race and speak to the di Y American spirit.

Born in rural Kansas in 1912, Parks was reared during a time of great racial strife in America when a brotha could get strung up for breathing too hard. His mother was the main influence on his life, never allowing her son to justify failure with the excuse that he had been born Black, and instilling in him self-confidence, ambition, and a capacity for hard work. During the cash-strapped Depression, Parks was taken aback by magazine photographs of migrant workers and bought his first camera, a Voightlander Brilliant, for $7.50 at a pawnshop. Parks was totally self-taught; the photo clerks who developed his rolls of film recommended him to a store in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he began shooting women’s fashion. Parks worked on several freelance jobs, then moved to New York and became a freelance fashion photographer for Vogue

While on a trip to Washington, D.C., during which Parks experienced some of the most vicious racism of his life, he shot his most iconic photograph, American Gothic. It depicts Black office cleaner Ella Woods holding a broom in one hand and a mop in the other, in the pose of artist Grant Wood’s stone-faced farm couple, with the American flag as a powerful backdrop. In 1948, a photo essay on a Harlem gang leader got him a permanent job as staff writer and photographer for Life magazine. He was the magazine’s first

Black photographer and worked there for the next twenty years, covering such diverse subjects as fashion, sports, Broadway, poverty, and racial segregation. In fact, Life sent Parks to “infiltrate” the Nation of Islam in 1963, but, instead, he and Malcolm X became close friends. Parks had the compassion and insight to be the voice of the poor and disenfranchised, but also possessed the skill and sophistication to make these unpleasant subjects palpable for the mostly high-tone Life readership.

In 1969, Parks became the first Black director of a major Hollywood film with an adaptation of his semiautobiographical novel, The Learning Tree Parks also composed the film’s musical score and wrote the screenplay. This story of a young boy coming of age in rural Kansas was seen by some as over-sentimentalized and “clean.” But minor criticism withstanding, the film holds up as the universal tale of a boy’s rite of passage and is included in the National Film Registry. Parks’s most famous film was also his most well known. Shaft (1971), along with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1970), ushered in the blaxploitation film era. Both Parks and Song director Melvin Van Peebles abhorred this term, but both films’ influence on the genre cannot be denied. In fact, Parks’s son, Gordon Parks Jr., directed the blaxploitation classic, Superfly (1972). Parks Jr. was even loaned a substantial amount of money by dear old dad when he went over budget after the first week of shooting. Parks’s next two films, the New York cop flick, The Super Cops (1974), and the fantastic blues biopic, Leadbelly (1976), were his most critically acclaimed. The Super Cops tells the true story of two Brooklyn cops, dubbed “Batman and Robin,” and their rather unique ways of fighting crime. Leadbelly, the story of blues musician Huddie Ledbetter, is seen by some as the best film about a musician ever. It’s a blood and guts story of defiance in the face of brutal racism. It’s the straight-up blues, baby. This celluloid gem still remains unavailable on either V hs or dV d.

In a world where mediocre talent is lauded and culture is expendable, Parks stood for something real in our contemporary American maelstrom. Parks exploded stereotypes by countering them with profundity. He was as self-made as self-made men get. Parks summed it up best when he said, “So many people could do so many things if they would just try, but they’re frightened off because they haven’t been trained to do this or that... I just picked up a $7.50 camera and went to work.” True indeed. .

Tanya Morgan is a hip-hop group By

Hidden behind the mysterious name are MC/producer Von Pea from Brooklyn, and MCs Donwill and Ilyas hailing from Cincinnati, Ohio. The trio completed the bulk of their first album, Moonlighting, by passing tracks through cyberspace, but have an affinity for cassette tapes and the golden era of hip-hop.

Expand on the cassette tape analogy.

Ilyas: That was the last time hip-hop was off the hook, for real. The purple Cuban Linx tape? [laughs] Right?

Von Pea: I thought it’d be cool to have an actual cassette passing around. Lot of people remember cassettes as the golden era. Just putting you in that mind state, automatically putting you in the mid-’90s. Your album touches on stereotyping.

Donw I ll: [People] say, “Oh, you’re like Common.” When you’re not talking about drugs, you’re just grouped into this big ball. Like, “Y’all rapping about the same thing, just not drugs and guns.”

Ilyas: I was rhyming about guns and all too, until I heard Midnight Marauders, and was like, damn Had someone to show me an example.

Von Pea: The very first song I ever posted online— everyone was like, “He sound like Jay-Z. Oh, he sound like Mase. Or “No, he sound like T3.” Nobody was like, “I like that line.” Everybody wanna say who you sound like first.

Ed Ntiri

Donw I ll: I find myself doing that a lot [too]. [When] people ask, “Define your sound,” you start classifying yourself. “It’s like Little Brother, Common, Kanye.”

Von Pea: We just everyday hip-hop, having fun. I don’t know how else to describe it.

Donw I ll: That’s what the name is all about. You don’t know what it is: The name sounds like it could be a punk rock act, a singer, western, neo soul. We kind of throw people through loops, constantly.

How do you see underground versus commercial acts?

Ilyas: I wouldn’t say I’m pro-underground. I’m promusic. I don’t try to diss mainstream, but I feel that the mainstream is out of balance.

Donw Ill: Not anti-radio at all; I play the radio. I can probably sing the entire “Lean wit It, Rock wit It” right now.

Von Pea: I might even say that we anti-underground. Not “underground” as far as a type of music, but “underground” as a mentality of what underground is supposed to be. Cats are ashamed to become successful. People are caught up in perception. I say I’m anti-perception, and if “underground” is part of that perception, then I don’t want to be part of it. We gonna get caught up in something, but we gonna fight it to the end. .

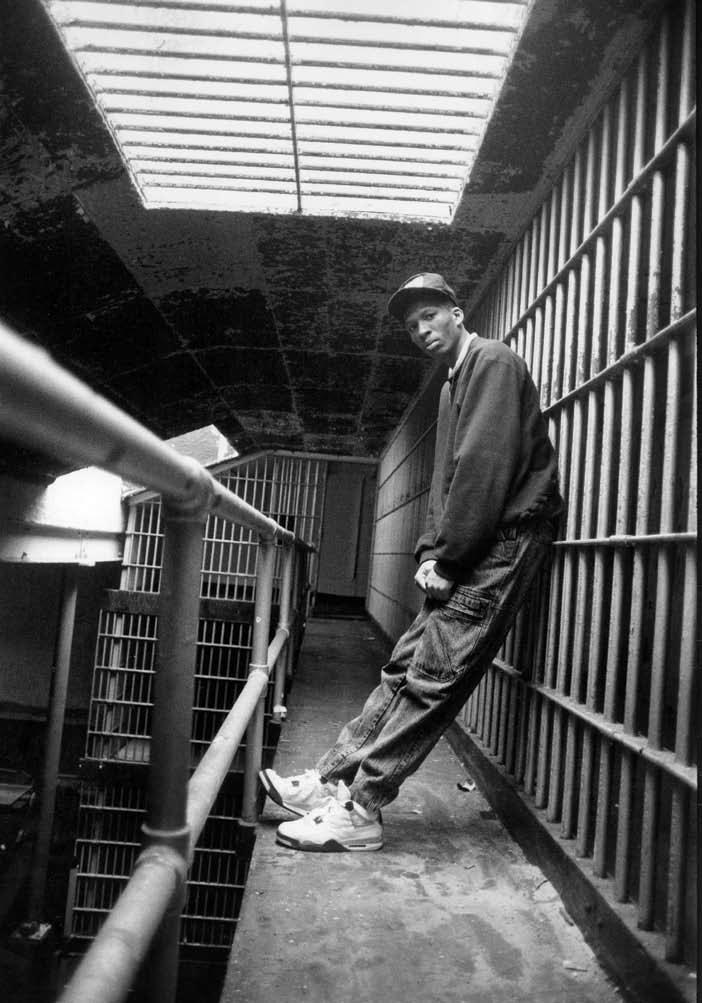

The untold saga of J Rock’s Streetwize

by Jeff Mao

You’d be forgiven for dismissing Streetwize, J Rock’s first and only LP, on sight upon its release back in early 1992. Despite the decidedly urban-oriented album title, there on the album cover—dipped in Yankees gear, posed beside a deep-purple Porsche—is J Rock, mad-dog mugging in classic rap fashion but incongruously stuck somewhere in the woods, a backdrop seemingly more fit for “Kumbaya” sing-alongs than concrete-jungle drama. ¶ Real informed heads, however, knew the deal. J Rock (government name: Floyd Johnson) was, in fact, a talented, no-nonsense MC in the Guru/Latee mode; an introverted fellow who, while still in his late teens, garnered a Source magazine “Unsigned Hype” write-up back in the bible of hip-hop’s salad days (December 1990). Foliage notwithstanding, his hometown of Newburgh, New York—a forty-five-minute commute from Gotham to the north and across the Hudson River—was less upstate safe haven than neglected, festering urban satellite.

“I think when people hear ‘upstate,’ they’re thinking trees and farms and stuff,” Johnson recalled in a rare interview in January 2004. “But at that time, [Newburgh] was slum; basically like the Bronx [but] upstate. The same thing you seen in the city, you seen up there—drug dealers, shootings. At that time, the West Coast really started coming [hard]—Ice Cube and NWA and them. And I kind of figured I’d do the same thing [they were doing] but with an East Coast flavor to it. I sort of took that concept and things I saw around the neighborhood and figured I would do an album for Newburgh.”

Though inspired by the conditions afflicting crack-era Newburgh, J’s suite of finely crafted hood chronicles transcends locale. In songs like the visceral title track, the swagger-filled “The Messiah,” and the twin tales of crooked cops, “Brutality” and “The Shakedown,” Streetwize represents a remarkably cohesive, impeccably produced confluence of hard-rock posturing and conscientious street reportage. J Rock impressively produced much of the material himself. However, a cursory glance of the back-cover credits ids two conspicuous studio accomplices in future super-producers DJ Premier and Easy Mo Bee (both at the time still fledgling beat-makers who regularly toiled at the album’s recording HQ, Suchasound Studios in Brooklyn). Preemo and Mo Bee’s lost board work shines big time; the former on the minimalist, Meters-fueled “Ghetto Law,” the latter on the hi-hat-reliant opening opus, “Let Me Introduce Myself.”

But if their presence is the album’s main angle of interest to hip-hop fanatics, ultimately it’s a name in the credits that’s well off the rap radar that’s actually most intrinsic to the backstory of this underappreciated gem, that of its executive producer, Jeff Murphy.

Alternately known by the Shawn Carter–esque handle “Jazz E,” Murphy (seen profiling by his pristine white Cher-

okee Limited on the album’s back cover) was an industrious, former underground radio jock whose early ’80s High-Powered Hours program on famed Newark, New Jersey, station W h Bi filled the late-night weekend slots left vacant when broadcast pioneers like Mr. Magic and Sweet G (of “Games People Play” fame) moved onto bigger endeavors. The proprietor of a Newburgh-based vinyl emporium, Fast Records (at which J Rock worked as a clerk), and top cat at his own indie record label, Ghetto Groovz, Murphy seemed like just another hopeful young entrepreneur trying to make some noise in the music biz, save for one notable detail: He also happened to be one of the biggest drug hustlers of the lower Hudson Valley.

“For what Jeff did, he was extremely successful,” remembers J Rock’s cousin, DJ Joey T. “Any day, you might catch him with twenty grand in his pocket. Easily. It was around that time when [the crack] scene was kind of exploding. And it was a little bit much for the [Newburgh] police to handle.”

The success of Murphy’s illegal business may have made him a revered figure in the streets, but he maintains that his illicit activities were merely a means to an end. “I went to college,” Murphy explains, “which doesn’t make me any better than anybody else who hustles, but I guess I had a different type of vision. I didn’t believe, at least on the surface, that hustling was a career. I just did it because, truthfully speaking, it was very easy and very profitable. I thought it was kind of a springboard to get me to where I wanted to be.” “Where,” of course, was the burgeoning hip-hop industry.

“[All along] I had been dealing with music,” he says forcefully. “I was there at the [Disco] Fever. I was there going and getting promos from Bobby Robinson at Enjoy Records. I was there playing the first Run-DMC record on the radio. I was there with [Reality Records’] Jerry Bloodrock when

he got his [label] off the ground with Divine Sounds and Rock Master Scott, and eventually signed Doug E. Fresh. All these guys did these things on their own. So I had seen the blueprint, per se. And I was very motivated.”

So much so that Jazz E enthusiastically championed the steady moral compass of much of J Rock’s material, his own ethically dubious side dealings be damned. Streewize ’s curious choice for a lead single was the overtly earnest “Save the Children”; its picture-sleeve jacket featured a faux newspaper article (from the fictitious 6th Boro News) discussing the societal ills that adversely affect kids (supplanting Murphy’s original idea of posting actual missing children reports as they appeared on the back of milk cartons). More anecdotal and effective in its approach was the dynamic second single, “Neighborhood Drug Dealer,” a brilliantly detached narrative charting the rise and fall of a notorious street pharmacist inspired by Murphy’s own life. In the first of a series of bizarre convergences of rhyme and reality, the aspiring rap mogul even brashly appeared in the song’s artfully directed video in (what else?) the title role.

“What was so funny about Murphy was he so wanted to be on television,” says DJ Premier. “I remember when he did the video; he was like [in nasally voice], ‘Yeah, yeah, I’m gon’ be on TV !’ He used to talk like that. ‘Premieeerrr, it’s on now. I’m gonna be poppin’!’ ” Murphy claims that he simply played the drug dealer role in order to ensure an authentic on-screen portrayal of “The Life”—something he was particularly sensitive to after enduring a disappointingly abstract and muted video treatment for “Save the Children.” “Because I had lived it and I knew what the drug dealer lifestyle was,” he reasons, “I didn’t trust no one else to do it but myself.” Murphy’s take on the song’s sobering story line (which ends less than happily for its antihero) remained something of a mystery at the time, even to J Rock.

“I thought it was kind of funny,” says Johnson, “because when I wrote the song, he knew it was about him, but he didn’t really say anything about it.”

In actuality, the hypocrisy of his livelihood in relation to the messages in the music he was promoting was readily apparent to Murphy, and difficult for him to reconcile.

“Once you start selling drugs and you put your future and your life on the line, basically, money becomes your primary focus,” he says in hindsight. “So I guess I had basically sold out my liberties and my freedom for money, and I was doing all these people harm. But on the other hand I’m saying to myself, ‘If this rap thing kicks off, then I won’t

have to sell drugs anymore.’ So I guess I was trying to save myself from myself, so to speak.

“Your actions always speak louder than words,” he admits. “But I never would have told a person to do what I did. That’s why I was in agreement with the idea that the drug dealer had to go down in the video. Even if I was bringing negative karma onto myself [by acting it out].”

Sure enough, just three months after the completion of the “Neighborhood Drug Dealer” clip, the video’s climactic arrest sequence came to life as Murphy was pulled over by police while driving in Harlem, and bagged for criminal possession of narcotics. Though he managed to beat the case (having been allegedly searched without probable cause by an officer from uptown’s infamously corrupt 30th Precinct, aka the “Dirty 30”), another calamity soon emerged from which Murphy and the Streetwize project would never fully recover—J Rock’s sudden retirement.

Johnson’s exodus left Ghetto Groovz’s one-man roster talentless. Even today, the ex-MC remains laconic on the details of the rift, but maintains that his boss’s criminal activities were never a factor. “One thing I’ll say is that Jeff kept me away from that,” he recalls. “I worked at the record store, and he never did anything around there—at least that I knew of. And so I never seriously worried about it. He really looked out for me.”

Murphy believes that Johnson’s then-girlfriend actually soured him on the music business, and laments the lost potential of his former protégé: “If that guy could have ever understood the extent of his musical talent…” he wonders aloud. “J Rock’s gift actually wasn’t rhyming. He was a superb beatmaker. Superb When Premier did the remix to ‘Neighborhood Drug Dealer,’ he told me, ‘I can’t do anything with the beat better than what he already got, but I’ll do something for you.’ The sad part about it was that [Floyd] never really understood the commitment it took [to make it].”

Others believe that Johnson simply grew sick of dealing with Murphy’s demanding personality. “[Floyd’s issue] wasn’t monetary,” says Joey T. “It was a point of Jeff bossing Floyd around, saying, ‘You gotta do this, you gotta do that.’ Floyd got tired of it and said, ‘I’m out.’ ” Johnson would subsequently attempt a short-lived comeback with Joey and Poughkeepsie pal Paul Nice in a group ill-fatedly christened Def Row (quickly aborted once a Ruthless-less Andre Young and his lil’ homie Calvin Broadus hit the charts) before calling it quits for good. “I’ll always love music,” Johnson summarizes in reflection. “But life goes on.”

Despite having already lost an estimated $50,000 on Streetwize, Jeff Murphy would continue to harbor hopes of making it in hip-hop. Splitting time between New York and Atlanta, he became an early investor in Tragedy Khadafi’s mid-’90s indie label, 25 to Life. But in yet another bizarre, self-prophesizing turn, Murphy was arrested again on criminal possession charges in November 1995 in Georgia, and went to trial the following March facing, yes, twenty-five years to life. (He eventually won a reduced sentence, serving nearly nine years between correctional facilities in Georgia and New York before coming home in May 2005.)

Today, Murphy works for a community activist group in Newburgh, mentoring troubled youths and speaking about his own experiences to deter them from following the path he had chosen. He hasn’t seen Floyd Johnson (a computer programmer living on Long Island, when last heard from) since well before his incarceration, and marvels that rabid hip-hop vinyl collectors typically pay in excess of one hundred dollars for Ghetto Groovz’s sole LP release. He estimates only twenty-five hundred were ever pressed, and roughly a thousand actually ever sold. The speculation that thousands of back stock copies of Streetwize were whisked away upon his incarceration and remain stowed in his mother’s house’s basement down South, he claims, is false Newburgh urban legend. It’s with some bewilderment that he absorbs the fact that folks are just now getting wise to the musical savvy of Streetwize

“On the one hand, I’m shocked that anyone’s still interested in the album,” he states wryly. “To quote a phrase NWA used to use, I thought I had a box full of Frisbees.

“But on the other [hand], I’m not really shocked,” he continues, disappointment detectible in his voice. “Because I’m gonna be honest with you: I really, really, really, really thought I had removed myself from hustling. I thought I had actually really, really, really did it. I was so committed to the project that I just knew I had something. I was just like, ‘I gotta keep pushing, something’s gonna happen.’ ”

In the end, Jeff Murphy will tell you that Nas was wrong: the rap game and the crack game weren’t actually that similar after all—at least not when it mattered most. “I didn’t understand the marketing and the distribution part of the business, and I was intent on doing it myself. I was just doing everything like I did in the street.”

He pauses briefly for a moment, perhaps momentarily lost in the memory of those years.

“It’s hard for you to tell what the movie is like when you’re acting the movie out,” he concludes philosophically. “You have to sit back and be able to see it on the screen, and then see how other people react, and say, ‘Oh man, I really did this?’ ” .

Jeff Mao, aka Chairman Mao, is one of the furious five minds behind burgeoning media conglomerate, ego trip. He is the coauthor of ego trip’s Book of Rap Lists (St. Martin’s Press) and ego trip’s Big Book of Racism! (ReganBooks).

Special thanks to Sasso for digitizing the video.

“Four Tet’s Kieran Hebden does a double-whammy with this batch of weirdness for !K7’s classic mix series. Brilliant.” - XLR8R

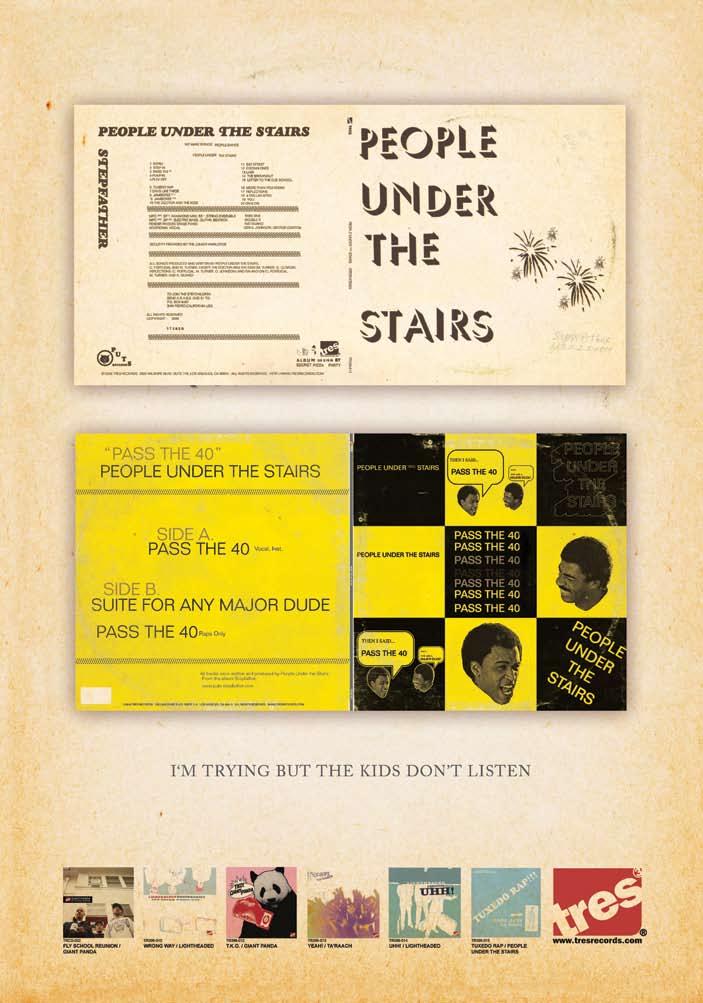

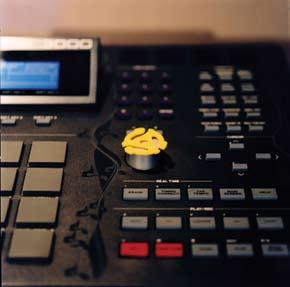

Thes One’s matrimonial mixtape

by Anna Klafter

photo by B+

The date is May 15, 2004, and Christopher Portugal, the rapper and producer better known as Thes One of People Under the Stairs, is entering his wedding on top of a large elephant. “I climbed onto that bad boy and I rode into that piece,” says Portugal. The traditional ceremony, which took place in front of seven hundred people, was the culmination of a six-year relationship with his girlfriend of Indian descent and was followed the next week by a Catholic wedding in Peru. In true record collector fashion, Portugal and his bride, Ritu, marked the occasion with a mix-CD representing both of their cultures and tastes.

Mithai, a Hindi word for the gift of sweets one brings to another’s home, is not just a collection of amazing tracks, but the soundtrack to a relationship that grew alongside Portugal’s formidable musical career. Portugal breaks down the essential tracks:

“The Promise”

Thes One (Pl70 Inc., off the master) 2004

Basically, I was not the right choice. I wanted to make song that was equivalent to the Bollywood movie song with the son-in-law trying to win the dad over with some fancy dance routine. Playful, but serious. “Look, it doesn’t matter, because we love each other, and this arranged marriage thing is not going to work for us. She loves me, so we’re getting married.” That was the theory behind that. So I made the track and recorded it during the process of making the mix- cd. It was definitely for [her father]. He thought it was nice; he didn’t think it was challenging, and it wasn’t. I had already won him over at that point. We were getting married, but there were years of struggle between him and I, so what better way to end that but with a song. I’m not mad. There was a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy with her parents about dating. They didn’t want to know unless it was serious. The whole time we were dating, they were ramping up the arranged marriage process. Things started to get frantic; it was tough on our relationship. There’s the whole process of putting ads out. Meanwhile, we’re in a monogamous relationship. We’re trying to hold it down, and they’re actively looking for a husband for her. She told her parents, and they utterly freaked out. Then it was on. On, in terms of “You can’t marry him.” There was a year or two of that, and they met my family. They eventually came around. All the Indians are doctors and lawyers and this Latino guy isn’t a doctor or a lawyer, so this song documents my stance.

“Mujhe Zindagi Ki Duva” Ek Zindghi Arman Bhari (OST) (EMI India) 1984

I’m an “old school” record shopper. I go digging with visual cues; I know my years; I can look at a cover and know the year. These are things you pick up when you’re digging and you don’t have a portable —you don’t want to be making stupid decisions. In L.A., I go through a bin and I can fly through it. I get to India and I don’t understand anything on these records—can’t read Hindi. I’m looking at these records and they all look good. So I fall back on dig-

ging theory. Everything is a soundtrack, so I start looking at years—’70, ’71, ’73, basically ’69 to ’75. I pull a giant stack, five feet high. I start listening —this music is garbage. I’m listening and this music sounds like it was recorded in the ’50s. I pull a record from ’82 and it’s off the chain; it sounded like it was recorded in ’72. Okay, apparently in India 1984 was like 1974; they were running five to ten years behind Western music trends. So, I pulled a stack from ’77 to ’85 and then I started finding all the cool shit. If you get deep and get beyond the covers and known stuff, there’s some really cool shit out there and its really it’s own thing.

With this record, there’s this psychedelic rock guitar and disco beat, pumping. We picked music together. I was playing that for her, and she’s like, “Damn, [the singer’s] saying, ‘Welcome to the party, have a good time, it doesn’t matter what other people think.’ ” It was weird how that fit in.

Stereolab Dots and Loops (Drag City) 1997

Absolutely mandatory. I used to work in a record store, Rhino Records in Westwood. This was in the early ’90s. As soon as I decided what I wanted to do, make hip-hop: Okay, I’m a beatdigger, so I needed a job at a record store so I could get first pick of all the records. I was only thinking about old records. Rhino mid-’90s, I’m digging all the old records, but being at the counter, I’m exposed to all the new things. I started getting exposed to new things that were totally outside of my sphere of what I would listen to—Stereolab being the most notorious.

Dots and Loops was about to come out—people were putting pre-orders on it. I was like, “Man, this record has to be something serious.” The day it came in, they had it in the listening station. I’ll never forget it. I went over the listening station on my break. It completely changed my whole life and I don’t mean that lightly. That record changed my life, it changed the way I look at music it changed the way I think about production in all senses, it changed the way I dig for records. It changed everything. And from that point

it became my favorite record and I exposed Ritu to it and she loves the record. It’s just a really important record, so it’s important that we fit one of the songs on there and I think it’s important that we put the first song of the record on there. “Brekhage” is the first song on Dots and Loops

“Move On Up”

Curtis Mayfield Curtis (Curtom) 1970

Damn Kanye West! He ruined the song. For Kanye, it’s like “Move On Up” and get richer. I don’t think I’m ever going home, I got so much Louis Vuitton. Dumbass. For us, this track fit what we were growing through. It’s parallel to what’s going on with America, with first generation communities, rebelling against their parents.

“I Would Die 4 U”

Prince and the Revolution Purple Rain (Warner Bros.) 1984

Prince. I had to put Prince on there. She said I had to put Prince on there. But Prince belongs on there because Prince is that dude. My wife grew up in Whittier [CA]; she was big into all the freestyle stuff. We wanted to have a few things that represented that side as well. You will notice there is suspiciously no hip-hop on there; that is a little bit deliberate on my part, because the hip-hop thing is the obvious thing. When you’re starting a life with someone it’s so much bigger than that. There’s very few hip hop songs that would translate well to this without being like, “Ewww.”

“Cross Country”

Archie Whitewater Self-Titled (Cadet Concept) 1970

I don’t think I’ve ever known another track I could play for any person, pretty much, and they’d like it. It’s not on the cd because Common sampled it, it’s on the cd because it’s one of the top five songs for me of all time. It’s a very moving song. What they are talking about is relevant; lot of the song is coming out of the Vietnam era, there’s a sense of turmoil and of struggle. It fits the theme of what we have gone through. It’s the right song and it’s on there for the right reason not the wrong reason. Yeah, it’s rare, but that’s not why it’s important. We wanted it because it’s a dope song and we love it. It could be a dollar record, it could be a

hundred dollar record.

The beatdigging community as a whole has fallen victim to comodifying the music more than what is fair. It takes away from things. Saying a record is $300 or $1000 doesn’t justify its existence on a mix. I love some records that are worth a dollar. I hate to see our community where our value is just [in] your rares; it might as well not be music. It might as well be Pez. Beatdiggers and collectors lose sight. Just because something is or is not rare doesn’t make it good. It’s your taste. It’s what you like. I don’t care what other beatdiggers think about our wedding cd.

The rarity of the music doesn’t come into play. You should only be playing music that has meaning to you. The important thing is the song.

“Peruano Hasta La Muerte” Pepe Miranda (Rey Record) 196?

It’s a really nationalistic, powerful track about Peru. It just gives me shivers thinking about it, because it means so much to me personally. Being the only cousin in America from my Peruvian family, it’s always been tough for me to maintain that cultural connection. That’s why I got into hip-hop in the first place; because it was kind of a foster culture. It was something I could be a part of, because I didn’t have a family to be a part of. I have, like, no family in America; hip-hop was that family for me. That song—I spent every summer going to Peru, and that song means a lot to me, culturally. Putting it on there, the song falls dead center on the cd. It’s in Spanish, but I was hoping some of the Indian people would get the idea of what it was about. This song being on the cd is me saying, “I’m not going to compromise any of my culture.”

“Get into the Party Life”

Little Beaver Party Down (Cat) 1974

This is a super-crucial song. It was our life, and it is not our life anymore. You know, you get married, settle down. It’s the perfect farewell to my twenties and that lifestyle. Once you are married, you have less incentive to go to the club, I’m more than happy watching Law and Order and staying home. My single friends will never understand this—“Awww, he’s married now.” Shut up. I save more money, I cook more meals, and I’m really happy for the

right reasons at this point. “The Party Life” is an important track because the party life was important to us and it was a part of us.

“We’ve Only Just Begun”

Port Authority Self-Titled (The Navy) 1971

I was making a wedding cd, and I was like, “Okay, we have to put some version of “We’ve Only Just Begun” on there. I was trying to find a version that fit into the mix well, and the Port Authority version did. It’s funny because “We’ve Only Just Begun” is the wedding song. Any digger worth a grain of salt has a zillion different covers of it.

“O Saathi Re”

Sunil Ganguly Electric Guitar Hindi Film Tunes (Odeon) 1979

This was huge song in the 1970s in India. This is a song that all of my wife’s aunties and uncles know, but why would I know this track? It’s because of record collecting, but putting it on the cd surprised a lot of people. It goes, “What would the purpose be of my living without you?” It fits into the dedicative nature of the mix. It fits in so many ways to my situation. From the movie O Saathi Re

“Loving You Sometimes” The Outcasts (Plato) 196?

Cut Chemist played this for me. Now, he’s a very sarcastic dude. I don’t see him get super-excited about records a lot. But that record he was really excited about. He was like, “I got to play you this record, it’s going to blow your mind.” He played it for me, and I was like, “Holy shit. You’re right, this is incredible.” It was representative of garage and Gulf beach music, but it was dark and it was about love. He was like, “Man, I’m going to start playing this out,” and I was like, “Man, you’re crazy.” And he did. I heard him work it into his set a few times. Thematically, it fit perfectly with the cd We both love it, and it would be cool to expose people to it. And it is fairly rare, fairly unknown.

“The Visit”

The Cyrkle Neon (Columbia) 1967

Ritu used to come over to my house and we would be laying around, and of course there were records everywhere,

and if you’re a record collector and all of the sudden you have a significant other, it’s like they weren’t there to buy all the records and they weren’t there to listen to all the records. Inevitably there’s going to be a part where she is like, “Play me a record.” You can pull out a record and maybe this record is worth $3000 and put in on, but if it sounds like cat shit, later on in life she’s going to be like, “Do you really need more records?” So you have to pick something that is representative of what you do. I picked this song because I thought it was a good example of what it means to me to be out there finding songs that I would never be exposed to. Just the ultimate 180 degrees from the things we are exposed to on a daily basis in America, music-wise. You don’t hear songs like that on the radio, you don’t hear songs like that on commercials…you just don’t hear stuff like that.

“Khullam Khullam Pyar”

Film Hits 1975 [Khel Khel Mein OST] (EMI India) 1975

The song says, “We are not going to be ashamed of our love, so deal with it.” It talks about blossoming love; we’re free. There is an underlying message to the whole cd

“Holding You, Loving You”

Don Blackman Self-Titled (GRP) 1982

Another suspicious “oh, he’s being a beatdigger” track. It was never properly released on GRP; it never appeared on an album. While we’ve been together, I’ve been digging really hard; it’s almost part of our relationship. One year for my birthday, I really, really wanted that record and she got it for me. Then I made a beat out of it for her [“Give Love a Chance”]. It made the record-collecting thing “ours.” .

Anna K L af T e R is a writer, DJ, and educator living in San Diego, California.

People Under the Stairs’ Stepfather LP is out now on Basement Records.

Four Tet selects records from across the board

by Paul Sullivan

photo by Paul Sullivan/Rob Ditcher (Photografik)

Kieran Hebden moves through the illimitable world of sound and space with grace, fortitude, and remarkable sonic acumen. His is a restless journey that casually erodes boundaries, subtly proposes musical theories, and explores the musical shaman within. ¶ His first band, Fridge (formed alongside bassist Adem Ilhan and drummer Sam Jeffers), released increasingly soul-searching documents with titles like Ceefax (1997) and Semaphore (1998), albums that celebrated freedom of choice and conjured up itinerant spirits that critics tried to bottle and put in a jar labeled post-rock.

on 2001’s Pause (released the same year as the fourth Fridge installment, Happiness), he sampled harps and accordions from British folk and psychedelia. This time he was named captain of an illusory genre called folktronica.

2003’s Rounds sealed Hebden’s fate as an unpredictable outsider, a mercurial magician working inwards from the peripheries of the music world, and an artist who thought nothing of shedding skins and turning dark corners. For 2005’s Everything Ecstatic, Hebden remixed his own history, turning in a set of dense, five-dimensional songs that surprised even his most astute followers.

Recently, Hebden has moonwalked further out of the circle, stepping backwards through time and sideways into illogic to collude with veteran drummer Steve Reid for a series of cathartic celebrations of rhythm and circuitry.

With Reid—best known for his work with legends such as James Brown, Martha and the Vandellas, Fela Kuti, Miles Davis, and Sun Ra—Hebden has finally thrown off the shackles and embarked upon a series of shows and recordings based on pure improvisation. Called The Exchange Session (Vol. 1 & 2), these albums represent yet another quantum leap into the unknown for Hebden, one of the few artists of the twenty-first century that isn’t afraid to let his fans listen in as he delves ever deeper into the rhythmical and mystical possibilities of sound and space.

Why did you start Four Tet?

I was listening to jazzy drum and bass and was furious because it mellowed the jazz elements out, and I hated that. So I started Four Tet initially thinking to do modern-style dance music that was heavily influenced by jazz, but a mad, heavy type of jazz, which was epitomized on Dialogue, a deeply free-jazz-influenced album. At first, I never envisaged doing more than a single, but then I heard Thirtysixtwentyfive being played twice in the space of an hour and a quarter on two different shows on the radio and realized it might have some potential.

Why have you collaborated with so many people over the last five years?

I get a huge kick off other musicians being interested in what I’m doing. Of all the people who say they like what I do, whether journalists or labels or friends, when another musician says they’re excited, that touches me. When other musicians take an interest in working with me, it has always seemed a real honor.

You don’t adhere to any particular music or style, but what type of music gets you most excited?

understand artists aligning themselves to scenes and things. To me, it indicates that a scene has reached the end of its line when it has a tag like that. It’s then an established sound. My scene is made up of international musicians. We hang out and see eye to eye on a lot of things. What links the records you’ve chosen below?

These are all personal records for me, in the sense that they are the physical records from the times that I was hugely into them. I worry about whether I’m being innovative and whether I’m moving forward all the time, and these records keep this in mind for me.

I chose this because it’s the record I remember most from my childhood. My father played it all the time; at every single party they ever had, this was the anthem. It’s an incredible song. It’s got enormous production by [Norman] Whitfield—incredible arrangements. It’s perfect pop music.

Blue

Joni Mitchell (Reprise) 1971

My mum listened to Joni Mitchell all the time—still does—so I grew up listening to her too. Blue has become a hugely inspiring record for me. Melodically it’s great, the way it was put together is great, the songwriting is incredible. It never gets any worse; it always sounds good.

Axis: Bold as Love

Jimi Hendrix (Reprise) 1967

Hendrix was truly one of the all-time greats in everything: musicianship, production, innovation.

When I was younger, I never understood feedback, but then it all started making sense to me and this is when my own music tastes began, with Hendrix. I could have picked other albums, but I keep thinking this is the best. It’s a bit more psychedelic in some ways. What they achieved with such limited equipment is amazing.

His debut solo long-player, 1999’s Dialogue, continued to skirt the boundaries of jazz, hip-hop, and electronica, but

In response, the band unleashed their exploratory freejazz opus, Eph (1999), highlighting their urge to expand in all directions, and reveling in their love of performing and working with acts that had little in common: Badly Drawn Boy, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, To Rococo Rot. From 1998, Kieran began releasing audacious solo strikes under the name Four Tet. His first experimental EP, 1998’s Thirtysixtwentyfive, alluded to a well-developed awareness of Krautrock’s locked grooves, the sub-bass tropes of hiphop, and the spiritual quest of free jazz.

It excites me when someone makes a radically experimental record but makes it in a way that people can identify with it. That changes the future of music. [Missy Elliott’s] “Get Ur Freak On,” [Aphex Twin’s] “Windowlicker”—no one could imagine those records before they arrived, but they understood it immediately; the sound is not too alien to them. That’s the ultimate goal—you see people’s perceptions of music changing in real time.

You’re always being lumped into different scenes, from post-rock to folktronica. How do you handle that?

People keep trying, and I keep trying to avoid it. I don’t

Siamese Dream Smashing Pumpkins (Virgin) 1993

This was a landmark teen album for me. There are mad multi-track guitar solos that I could play on guitar. I got this copy on the day of Phoenix Festival. I had just enough money to eat and I still saved something to buy this the morning after the festival. When I got home, I hadn’t washed in five days, and I put this on and it was everything I hoped it would be. I still

listen to it now all the time. Melodically and the way it is built has all had a massive effect on the music I make now.

Sign of the Times

Prince (Paisley Park) 1987

I was always into Prince. I missed his good period, as I was around ten, but the girls at school were into him and being into him gave you a lot of cred with them, especially if you made them a tape. This album is insane because of the way it’s recorded—all made with drum machines played live and slightly off kilter. Sonically, it sounds so different to everything else—the speeding up and slowing down of his voice. I like that level of experimentation.

“Ni Ten Ichi Ryu”

Photek (Virgin) 1997

Everyone goes on about Autechre and Aphex, but I also think Photek was up there. His records were more ambitious than anything else going on; they were on a whole other level. This record is off the scale. What I love about it is not only was it trying to be the most innovative thing ever, it also tried to rock a club at the same time.

Enter the 36 Chambers

Wu-Tang Clan (Loud) 1993

I think that this is one of the best albums ever made. I go back to it again and again as a record I thoroughly enjoy and that has some kind of magic in it that I reach for and aspire to when I make music. I don’t mean I want to sound like them, but I love their mentality.

Tortoise (Duophonic) 1995

This track is all over the place, and it sounds incredible. For me, it was a whole new world of music. The combination of this and “riot grrrl” and K Records and Pavement made me realize that Fridge wasn’t just a band messing around in our bedrooms. Tortoise justified all our interests in drum and bass and lo-fi. They inspired me to see that you don’t need a proper studio to work.

Ege Bamyasi

Can (United Artists) 1972

This is an album that has so many killer tracks and it’s my favorite Can album. It’s hugely influential. No one has ever sounded like them and no one ever will. They came out with a sound that smashed everything up.

Alice Coltrane (Impulse) 1970

I bought this because of the cover. I listened to it and thought, “Wow, that’s on another scale.”

From this, I became obsessive about cosmic jazz and became interested in music that combined radical Black politics and Eastern mysticism.

the Corner

Miles Davis (CBS) 1972

My dad was a sociology teacher and taught a course on the history of hip-hop. He would talk to me about the social background of music, and that was when I understood the bigger picture and got interested in musician’s attitudes. I started to realize that Miles Davis was a hugely inspirational person because of his wanton need to move forward all the time with his music, no matter how popular he was. I bought more and more of his records, but I like this because it’s such a heavy funk album.

Pete Rock and CL Smooth (Electra) 1992

There is something from that era that has had an impact on my production. Pete Rock’s loops and drums always influence me; he has a real natural flow, not too rigid. I can listen to this tune a million times, and every time I hear it, it stops everything.

Steve Reich (Deutsche Grammophon) 1973

I’ve never been into classical music, but I love repetition. Classical has always been to me about having an idea and exploring all the variations of that idea; whereas the music I like, such as hip-hop, is about finding an idea and repeating it until you get bored. I heard Reich was all about repetition and this is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever heard. It has influenced the way I approach things.

Morton Subotnick (Nonesuch) LP (1967)

I’ve got about a hundred squiggly electronic albums, and this was one of the first ones that had big commercial success at a time when most of them were coming from universities and radio stations. You can actually really listen to it. Parts of it sound more contemporary than electronic music that’s around now, in terms of the arrangements and quality of sounds. .

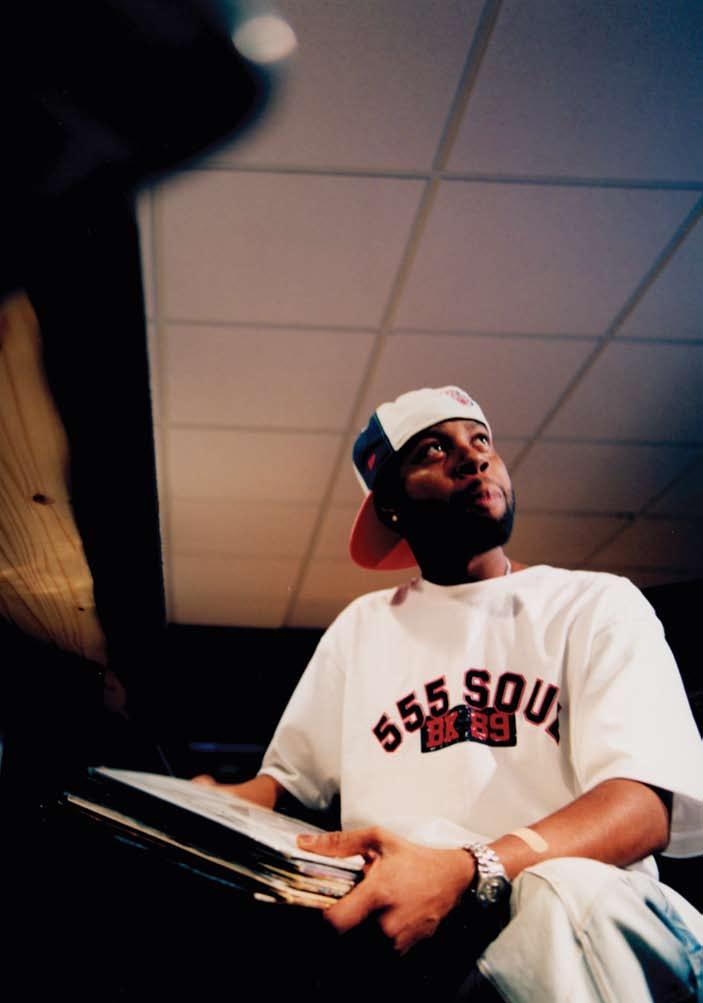

Bay Area hip-hop and the rise of hyphy

by Joe Keilch

It took eight long years before I got my break, So I wonder why rappers make fake-ass tapes. You won’t get paid like I did, so give up punk.

And while you’re in the studio, I’m in the trunk.

–Too Short, “In the Trunk”

Bay Area hip-hop is currently experiencing a resurgence in outside interest that has not been seen in over ten years. Most of the current attention is focused on a new movement, sound, and culture dubbed “hyphy” by hometown hero Keak da Sneak. Before beginning to try to define hyphy, it’s important to back up and look at the history of Bay Area hip-hop and the factors that have affected it. Looking at its history, the musical phases, the business moves, the important subregions of the greater Bay Area, and the support of local radio and retail outlets, one model can be seen over and over: the do-it-yourself approach.

While there were artists who came before him, Todd Shaw’s alter ego, Too Short, aka Short Dog, aka Shorty the Pimp, was Oakland’s first hip-hop superstar. Musically, he was heavily influenced by Black music stars of the 1970s and ’80s; yet another great influence on the crafting of the Too Short character was the 1973 blaxploitation classic The Mack Filmed in Oakland and starring Max Julien, Richard Pryor, and Roger E. Mosley, this film was hugely influential on young men who grew up in Oakland in the 1970s. Watch the movie with someone from Oakland and you’ll hear “Hey! That’s where I…” over and over. While Short grew up in South Central, Los Angeles, and didn’t move to Oakland until 1979, the prototype for the mack spitting game was laid down before he hit “The Town.” And he ran with it. Much like The Mack ’s pimp character, Goldie, recruiting his girls one by one after he got out of prison, Short and his partner Freddy B sold tapes one by one on foot to anyone with a little money to burn—mostly local dope dealers. He’d even make special tapes where he shouted out someone’s name for a little extra. As he explains in Brian Coleman’s book, Rakim Told Me, and in just about every song he’s ever released, once he’d captured that market, he stepped it up and starting selling tapes out of the trunk of his car; they quickly became regional best sellers. The next step was to sign with local label 75 Girls, through which he dropped three records, Don’t Stop Rappin’ ; Raw, Uncut and X-Rated ; and Players. When it was time to move on from 75 Girls, Short started his own label, Dangerous Music. The label’s first release in 1987, Born to Mack, went on to sell over 50,000 copies in the Bay Area alone. It was from these phenomenal sales, without a single, without major-label push, with only Short and his label’s work, that Jive Records came calling. Like Jive would later do with artists from other regions all over the country, Short’s next record, Life Is…Too $hort , was dumped into the market with little to no promotions, no single, no posters. However, Life Is… went on to sell 300,000 in its first three months, largely through Short’s grind on his own behalf and the buzz and fan base he’d es-

tablished with his earlier releases. Once it was clear that he was a “national” artist who could sell big numbers outside of the Bay Area, it was on. Short went gold or platinum on every record he released through the mid-’90s. Musically, Bay Area hip-hop through the mid- to late 1980s and early 1990s was largely based around samples and replaying records by Zapp, P-Funk, Cameo, Ohio Players, One Way, and other artists that are thought of as West Coast funk, at least to people on the West Coast. Examples can be seen all over Digital Underground’s Sex Packets, Richie Rich’s “415,” and Mac Dre’s “California Livin’.” Like Al Eaton, Too Short’s production partner up until Shorty the Pimp, many of the producers during this period played a variety of instruments and would create songs around familiar melodies with a minimal amount of sampling. And, of course, there were liberal doses of the Roland 808 drum machine. Many of Too Short’s records were built around nothing but an 808 drum pattern and a very simple synth line. Combing these stripped-down elements with his trademark “ biiiitch,” the sound was created.

On the back of “Dope Fiend Beat” and “Freaky Tales,” Short became the soundtrack for the entire Bay Area. But, he never hesitated to claim exactly where he was from, East Oakland. As Too Short proudly proclaims in “In the Trunk,” “Every rap I made was about this town.” In the same way, other important areas in the Bay Area asserted themselves. North Bay’s Vallejo had E-40, B-Legit, D-Shot, and Suga T, with Celly Cel in Vallejo’s Hillside area, while Mac Dre and Mac Mall had the Crestside neighborhood locked. The other corner of the triangle was San Francisco, primarily the Fillmore neighborhood, home to JT the Bigga Figga, San Quinn, Messy Marv, and the whole Get Low Players crew. Of course, there were rappers in other parts of the region, including Hunter’s Point, Lakeview, and Oakdale in San Francisco and West and North Oakland. But, up through the mid- to late ’90s, the majority of rappers in the Bay Area could still be found coming out of East Oakland, Vallejo, or the Fillmore. The importance and interplay

of these neighborhoods can also be seen on the numerous collaborations between artists from the three main neighborhoods.

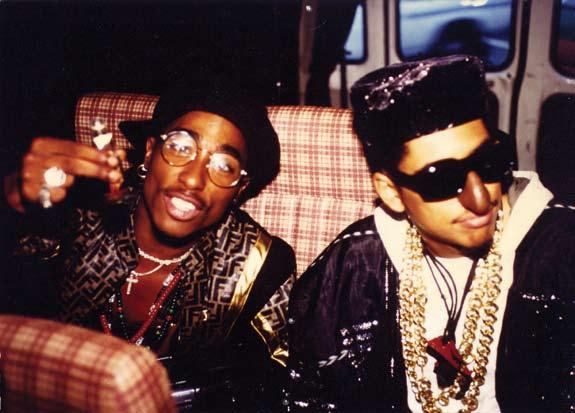

In regard to the di Y model, the following point can’t be made too strongly. With the notable exception of Tupac and Del tha Funkee Homosapien, the di Y approach (sell tapes out of the trunk, move up to a regional label/distributor while developing personal relationships with radio programmers and personalities, and then make the jump to a major label) was the blueprint that every subsequent artist followed. MC Hammer, formerly “The Holy Ghost Boy,” went the independent route before signing with Capitol Records and making a mockery of Bay Area hip-hop. Digital Underground created a regional buzz by distributing the “Underwater Rimes” 12-inch with L.A.-based Macola Records before signing with Tommy Boy and releasing the multiplatinum Sex Packets Young Black Brotha (YBB) Records got first their area and later the whole Bay hooked on Mac Dre, Mac Mall, and Ray Luv through Strictly Business Records before releasing projects on Atlantic, Relativity, and Tommy Boy. San Francisco’s RBL Posse pumped hundreds of thousands of copies of Lesson to Be Learned through In-A-Minute Records—which was run out of local one-stop distributor Music People—before signing to Atlantic Records. And, while later associated with New Orleans, Master P got his start in Richmond, which is about halfway between Oakland and Vallejo. Off the success of his West Coast Bad Boyz project, a compilation featuring staples from the Bay Area scene at the time, P was able to

negotiate the deal with Priority Records that gave him the distribution outlet for the gazillion No Limit releases to follow. (Oakland producer E-A-Ski claims that he hooked P up with Priority based on his relationship with the label.)

Most important of this era was E-40 and his Sick Wid It Records. After building out from his home base of Vallejo, 40 dropped three releases that brought Barry Weiss and Jive Records to his door: his “The Mail Man” and “Federal” and the Click’s “Down and Dirty.” E-40’s increasing sales were evidence of a changing of the guard, his impending rise to the role of Bay representative to the rest of the country, and the next phase of Bay Area hip-hop. Best described by E-40 himself as “mob music,” this style was tailored for California’s car culture. The music is slower and harder than what came before, and the lyrical content was more concerned with speaking directly to the listener and to the realities of the street than to pandering for commercial success. It was led by producers like Khayree, Ant Banks, Tone Capone, Mike Dean, Studio Tone, Sam Bostic, and Mike Mosley, among others, who provided beats for the Luniz, Celly Cel, 3X Krazy, and Spice 1.

At the same time mob music was becoming the predominate sound, the Bay also saw a wave of artists who drew their inspiration from New York hip-hop. Ice Cube’s cousin, Del, dropped his first album, I Wish My Brother George Was Here, in 1991, and was quickly followed by debuts from Souls of Mischief in 1993, and Casual and Extra Prolific in 1994. Del and Souls both made it to a sophomore release before the whole Hiero crew was dropped from their ma-

jor-label deals for not meeting sales expectations, according to Hiero member Domino. In a reversal of Too Short’s formula, they went back to the indie grind where they’ve been for almost ten years now. Domino is clear that “Too Short and the whole indie mentality showed us that there was something other than the major-label route.” As Hiero was hitting Telegraph Avenue, the main shopping strip in Berkeley, with their homemade tapes for sale, they were competing against crews like Hobo Junction, Mystic Journeymen, and the whole Living Legends crew. At the time, there were several important stores along Telegraph Avenue. If they didn’t get at you in between stores—“you listen to hip-hop?”—they’d have a second shot inside the store.

Part of the ability to sell enough units to earn a living as regional or indie artists comes in part from the retail support in the Bay Area. Stores like T. Wauzi’s in Oakland, Star and Zebra Records in San Francisco, Leopold’s and Amoeba in Berkeley, and the mini-chain Rasputin’s have always sold records by regional artists and other independent artists. Balance, the current hip-hop buyer at Rasputin’s and an Mc himself, says that Bay Area releases sell as much as or more than a national artist in Rasputin’s stores. A Bay artist can sell between 7,000–15,000 units in the Bay Area alone. That’s partly due to some store buyers’ understanding of what the people want—many because they are Mc s, dJs, or producers themselves—as well as distributors that have in the past or currently do see the money in Bay artists, including Marin County–based City Hall, Music People, California Record Distributors, and SMC, a farm-team

distributor for Navarre/Universal. The other part of this equation is the success of Bay Area artists in the South and Midwest. As Too Short, E-40, and other Bay Area artists have never sold well in New York, and most of the music industry and hip-hop press machine is based there, they are seen as largely inconsequential and a “regional thing.” But, that dismisses the fact that their platinum-plus sales are largely based on support and their fan bases in parts of the country other than the Northeast. And, platinum on the indie level or with a distribution deal can provide a lot more than just a living.

Radio support has been a much dicier story. On the college and community level, stations like San Francisco’s KP oo, University of California Berkeley’s K a L x, University of San Francisco’s KUsf, and Stanford’s KZ s U have exposed Bay Area artists in differing ratios of street-oriented to more backpack-focused hip-hop. But one station has always been the most important in the Bay Area in any discussion of hiphop, KM e L . In the early to mid-1990s, KM e L was a groundbreaking station. Once home to King Tech and Sway’s 10 o’clock Bomb, the forerunner to The Wake Up Show, KM e L was the most important hip-hop station in one of the U.S.’s top-five markets. Mix-shows routinely broke new records, both soon-to-be regional hits and songs by national artists. The breadth of the Bay’s diversity, from 3X Krazy to Souls of Mischief, from N2Deep to Total Devastation, from Digital Underground to 415, could all be heard. But, as a result of the loosening of FCC radio station ownership regulations in the Telecommunications Act of 1996, KM e L and KYL d

the distantly second radio station of importance—were bought by the media juggernaut Clear Channel in 1999. As a result, KM e L saw the same type of playlist homogenization that Clear Channel stations around the country dealt with. Between 1999 and 2002, the self-proclaimed “People’s Station” added fewer and fewer local acts until its playlist was nearly identical to Clear Channel stations halfway across the country. But in late 2001 and early 2002, the tide started to change. Amidst rising protests in the community, the “People’s Station” added a song called “Closer” by Oakland soul singer Goapele to the rotation. It quickly skyrocketed in numbers of spins and was soon followed by an influx of local talent that was bubbling in the streets, first and most notably, Keak da Sneak’s “T-Shirt, Blue Jeans and Nikes.” Once it became clear that local artists were a big part of what Bay Area commercial radio listeners wanted to hear, the number of locally produced songs on the radio changed quickly. As Von Johnson, music director and mix-show coordinator of KM e L , and self-proclaimed “Bay Area radio boss,” explains, Bay Area artists routinely get seventy to eighty spins per week on KM e L

The first wave of artists after the radio dam broke included Federation, E-A-Ski, Frontline, and Bay mainstays Keak and B-Legit. However, the first wave quickly grew into a split: on one side was E-A-Ski and Frontline with their “New Bay” sound; and on the other stood Rick Rock and Federation. Ski’s sound was more traditional West Coast: big bass lines, synth lines, and melodic choruses, more up-tempo than mob joints but still for riding in cars. In some respects, it was both a transition phase to hyphy and an updating of the classic west-side sound. Federation came out a little ahead of the “hyphy” curve. Their first single, produced by Rick Rock and titled “Hyphy,” dropped in 2003 and contained the blueprint for what almost every producer and artist since has latched on to. Up-tempo with crazy amounts of energy, chaotic elements, vocal samples, and the ubiquitous E-40 guest verse, “Hyphy” ensured confusion in people over thirty and made eighteen-year-olds go crazy. In the end, the New Bay versus hyphy debate was short-lived and, as Federation puts it, “Make a baby mama slap her baby daddy, hyphy!” won out.

And that brings us to some kind of definition of what “hyphy” is. E-40 and Keak view it as a movement. Oth-

ers say that it’s not a movement because it lacks a common definition of itself. In part, it’s a particular musical sound, largely based on Rick Rock’s production and his imitators. Rick describes it as “youngster-driven…high-energy West Coast music.” Partly, it’s white tees, fronts, dreadlocks, and ecstasy pills. Partly, it’s people getting wild and having a good time in spite of the everyday struggle of being young and Black in a fucked-up economy. And, partly, it’s a truly unique regional phenomenon that developed as a result of the isolation that the Bay Area has been living in since the mid-1990s, in the same way that New Orleans did with bounce, Atlanta did with crunk, and Houston did with screw. One thing is clear, it’s something that is as Bay as Too Short selling tapes out of the trunk.