SPRING 2023

READY FOR THE WORLD

News and Events

SOONER MAGAZINE

EDITOR

Anne Barajas Harp

The Big Idea How can meteorologists translate life-saving information to Spanish speakers during weather emergencies?

ASSISTANT EDITOR Sharon Bourbeau

Sooner Nation

Sixty years later, Paul Gregory breaks his silence about the Oswalds and his family’s role in the JFK investigation.

Eugenia Kaufman: Overlooked, but not in the hearts of her students. 32

ART DIRECTION

Walker Creative, Inc.

Steven Walker, Christopher Lee and Kyle Gandy

Sooner Magazine is published quarterly by the University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc. with private funds at no cost to the taxpayers of the state of Oklahoma. The magazine is printed by the Transcript Press, Norman, Oklahoma, and is intended primarily for private donors to the University of Oklahoma and members of the University of Oklahoma Alumni Association. Opinions expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the University of Oklahoma or the University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc.

STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Travis Caperton

Epilogue

Medical students embrace their future during OU Match Day. 33

After earning a 1984 OU psychology degree, Chip Minty started a long career in journalism and PR for The Oklahoman and Devon Energy. He is principal of Minty Communications LLC. When not at work, Chip’s usually riding his bike.

For private donors to the University of Oklahoma and members of the University of Oklahoma Alumni Association ON

Susan Grossman, OU ’83 BA Letters, uses experience in journalism, PR and fundraising to lead the grants program at the Oklahoma City-based philanthropy Kirkpatrick Foundation. She loves adventure, traveling and writing about people who work quietly behind the scenes.

PUBLISHER

The University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc.

Guy L. Patton, President

Archived copies of Sooner Magazine are available on the University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc. website: http://www.oufoundation.org

Copyright 2023 by the University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc. Address all inquiries and changes of address to: Editor, Sooner Magazine, 100 Timberdell Road, Norman, OK 73019-0685. Phone: 405/321-1174; email: soonermagazine@ou.edu.

Travis Caperton PHOTOGRAPHER

Travis Caperton, OU ’93 Journalism, began his craft at the OU Daily. He worked for newspapers including The Aspen Times and was the longtime Oklahoma State Capitol legislative photographer. Travis has served as an OU photographer since 2016.

8

Navigating the Open Oceans of Quantum Synchronicity

Even tiny atoms like to pair up. OU physicists are exploring how to harness quantum synchronization.

12

If You Light it, They Will Come OU’s rec fields get lighting, and students get to play long after the sun sets.

16

Ready for the World

Sooner Works, for uniquely abled students, sends off its first graduates with new life and job skills.

22

The Headbanger’s Overture Opera singer and heavy metal composer Joel Burcham exists in the worlds of both Mozart and Metallica.

26

OU men’s gymnastics, OU soccer and Pride of Oklahoma Marching Band members are mentors to elementary students.

OU 2011 musical theatre alum Adrianna Hicks continues to take Broadway by storm as Sugar—a character made famous by Marilyn Monroe—in the musical adaptation of “Some Like it Hot,” which is nominated for 13 Tony Awards. Hicks originated

the musical role, as she did with Catherine of Aragon in the North American premiere cast of “SIX.” She and fellow “SIX” cast members won the Drama Desk Ensemble Award. Hicks made her Broadway debut in “The Color Purple.”

Tim Headington, OU ’72, is seeing a lot of gold these days—Oscar gold, that is. Headington executive produced Oscar darling, “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once.” The film snagged seven golden statues, including Best Picture. Headington produced 2013’s Best Picture, “Argo,” and the 2011 Best Animated Feature, “Rango.” He also supported the construction of two OU residence halls named in his honor—Headington Hall and Headington College.

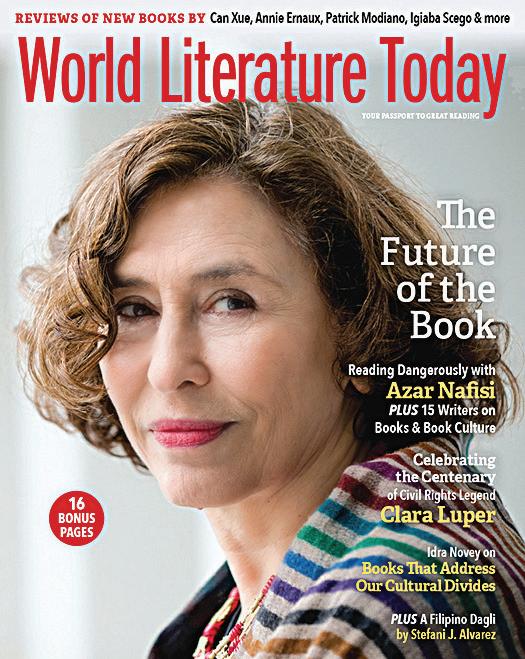

Azar Nafisi, 1979 OU English Ph.D. graduate and internationally acclaimed author of New York Times bestseller Reading Lolita in Tehran, is the first alum ever featured on the cover of OU’s famed World Literature Today. May’s spring issue features an interview with Nafisi on “The Future of the Book” with WLT Editor-in-Chief Daniel Simon. To purchase the issue or read online, visit worldliteraturetoday.org

OU broke its record for research expenditures for the second year in a row. More than $416.6 million in expenditures—an 8% increase—were reported to the National Science Foundation Higher Education Research and Development Survey. “OU research is improving lives and preparing tomorrow’s workforce,” says OU Norman Vice President for Research and Partnerships Tomás Díaz de la Rubia.

Whether it’s a sassy tango or swinging your partner dosi-do, dancing improves lives. Studies show people with Parkinson’s who dance have better balance, walking and cognition. OU offers “Dance for Parkinson’s,” taught by OU faculty in collaboration with The Well, a Norman public wellness center. “They become part of building a community that is filled with dignity, respect and support for one another,” says Michael Bearden, OU professor of dance.

Sooner Magazine may have started in 1928, but you’re never too old for a new look. The magazine’s redesign is the brainchild of Walker Creative Inc. owner Steven Walker and associates Christopher Lee and Kyle Gandy, the same team behind multiple award-winners Oklahoma Today, published by the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department, and ARTDESK, published by Kirkpatrick Foundation. Tell us what you think at soonermagazine@ ou.edu.

PAUL GREGORY’S NEW BOOK

opens with a startling scene: He’s in Oklahoma Memorial Union watching breaking news about John F. Kennedy’s assassination. As the suspect’s picture is broadcast to the nation, Gregory realizes he knows the man who killed the president of the United States.

Gregory’s recollection of the 1963 assassination, The Oswalds, is the first major foray into telling his unique story. A child of Russian immigrants raised in Fort Worth, Texas, Gregory recalls a part of his life that remained quiet for a half-century: How he connected with Lee and Marina Oswald; spent time with the family as Marina tutored him in Russian; and testified before the famed Warren Commission, all while a University of Oklahoma student.

The narrative of Gregory’s book represents a small slice of his upbringing in Fort Worth’s tiny, tight-knit Russian community, a background explaining his study of the language and the country. The two-time OU graduate became a noted economist, academic and author specializing in Soviet economics and history.

“OU played a role by directing me toward Russian studies and language, which served me well throughout my life,” says Gregory, now 81. “Intellectual excitement about the study of Russia, fostered by professors Robert Vlach, Herbert Ellison and Nikolai Rzevsky, left a lasting imprint on me.”

While he picked up some Russian at home, Gregory received his first formal Russian lessons at OU. His studies were bolstered by an unusual source.

Gregory and his father, Peter, met the Oswalds in the summer of 1962. The Gregorys were interested in connecting with Marina, a Russia native who’d married Lee while he lived in Minsk. In 1962, she was raising their infant daughter and spoke little English, leaving her in virtual isolation. Lee visited Peter Gregory in his office; shortly after, it was agreed that Marina would tutor his son.

Paul Gregory formed a friendship with Marina during lessons, delivered via conversational Russian as he regularly drove the car-less Oswalds around town. Gregory believes now that he was Lee’s concession to Marina—a companion she could talk to and spend time with, but one he assumed was in no danger of revealing how poorly Lee provided for their family.

But Gregory unwittingly did just that.

He and his parents introduced the Oswalds to their Dallas Russian friends during a dinner that resulted in the couple’s move to Dallas, where women of the Russian community showed Marina that Lee wasn’t offering her a decent standard of living.

“[The Dallas Russians] would want to meddle, to help out, to tell Marina the facts of life about America and her husband,” Gregory writes in The Oswalds. “Marina’s Dallas Russian friends would become a constant source of friction and conflict. They also gave Marina an escape. If life with Lee became intolerable, they would offer her shelter and protection.”

In the days after the assassination and Lee’s murder by Jack Ruby, Peter Gregory became an important figure in Marina’s life, translating between Lee’s widow and Secret Service investigators questioning her about a possible conspiracy. Both Paul and Peter Gregory testified before the Warren Commission.

Yet, Gregory says, his family didn’t talk among themselves—and surely not among friends and neighbors—about the assassination.

“We wanted to keep our involvement with Lee Harvey Oswald as quiet as we could,” he explains. “Fort Worth was a very

Lee, Marina and baby June in a photo booth at the Fort Worth bus station, where Paul Gregory dropped them after they shared Thanksgiving dinner with his family in 1962.

conservative place, very patriotic, as was the Russian community.”

While he told some fellow OU students about his connection to the Oswalds, word surprisingly never spread around campus. With his parents now gone, Gregory’s immediate family likely heard the full story the first time they read his book, he says.

Gregory attaches little cathartic significance to the retelling of events, but believes his account is an important part of the historical record. Few people who knew the Oswalds are still alive.

“One factor [in my decision to write the book] is the encouragement I got from fellow academics who said, ‘You’ve experienced history, and it’s your obligation to write it down.’ There’s hardly anyone living who had the experiences that I had.”

Gregory’s story and his later contributions to Soviet studies are examples of “the remarkable lives that our OU students go on to lead,” says Emily Johnson, OU’s Brian E. and Sandra O’Brien Presidential Professor of Russian and co-director of the university’s Romanoff Center for Russian Studies.

Gregory has written 12 books and held positions from director of the University of Houston Law Center's Russian Petroleum Legislation Project to chair of the international advisory board at the Kiev School of Economics. He is currently a research fellow at Stanford University’s prestigious Hoover Institution.

“OU alumni go on to reshape fields,” Johnson says. “Paul Gregory is a good example of that.”

Gregory says he doesn’t want to reopen a debate on the assassination; he’s not interested in addressing a multitude of conspiracy theories. Gregory’s memories paint Lee as a legend in his own mind, a man eager to prove his exceptionalism to himself and his wife, with whom he was openly controlling and abusive.

“Everything that I saw says, ‘This guy couldn’t have organized an assassination— and he wouldn’t have been brought into an assassination plot,” Gregory says. “What he did, he was perfectly capable of doing.”

“OU played a role by directing me toward Russian studies and language, which served me well throughout my life.”

—PAUL GREGORY

NATIONAL ARCHIVES-JFK VIA GETTY IMAGES

AN OU GRADUATE STUDENT’S RESEARCH IS BRIDGING THE GAP FOR SPANISH SPEAKERS FACING THE DANGERS OF SEVERE WEATHER.

By Chip Minty

By Chip Minty

NO ONE LIKES TO BE IN THE crosshairs of a tornado-bearing thunderstorm, but for Joseph Trujillo Falcón, the experience was especially traumatic. The dark clouds, the sirens, the weather forecasters with their maps and foreign jargon left an impression that lasted a lifetime.

Trujillo Falcón was only 5 when his family moved from Lima, Peru, to the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where he got his first taste of Tornado Alley.

“Peru doesn't even receive an inch of rain annually,” says the 24-year-old, now a graduate research assistant at the National Weather Center on the University of

Oklahoma’s Norman campus. “To go from there to seeing all these storms pop up, it scared me. It scared a lot of my family members and my community.”

Staring down tornadic storms is stressful enough for English speakers, but for the millions of people in the United States who don’t speak the language, severe weather

can be especially terrifying—and even more deadly. Trujillo Falcón is dedicating his career to improving severe weather communications on a national scale.

After earning his Bachelor of Science degree in meteorology from Texas A&M University, Trujillo Falcón came to OU, where he is completing a Ph.D. in communications.

“To this day, there's no English-to-Spanish dictionary for weather and climate terminology,” he says. “And there are terms that we haven't translated over to Spanish. If we can't even describe the hazard to somebody, how can we expect them to respond or take it seriously?”

Trujillo Falcón says that revelation led him to drop plans to pursue a career in television meteorology and focus on research and advocacy for multilingual issues in meteorology.

“I'm just a firm believer that lifesaving information should be accessible to everyone,” he says.

That journey began in January 2020, when Trujillo Falcón presented a paper at an American Meteorological Society conference in Boston. He started with a story about the devastating EF-5 tornado that struck El Reno, Okla., on May 31, 2013, killing seven Spanish speakers. The El Reno family heard tornado sirens, but because there was no Spanish-language information, they didn’t understand proper safety procedures and sought shelter in a storm drain. The family also missed a flash flood warning. Tragically, flood waters swept them away.

“This sort of thing has happened time and time again,” he says. “That's why I initially wanted to be a broadcaster. I wanted to help these communities. But as I went through college, I realized there wasn’t a long-term solution.”

Trujillo Falcón’s paper proposed developing a uniform vocabulary of Spanish-language terms to describe the level of risk associated with severe storms. The vocabulary also would address the reality that even minute differences in dialect can have an impact on interpretation.

“That day in Boston, people were open to hearing more and wanted to get involved. Honestly, I felt like it was a new chapter in how we approach these communities and how we can benefit them in the future.”

Trujillo Falcón says the conference led to federal research grants and wide buy-in from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), academia and television broadcast stations across the country.

A team of researchers and other graduate students quickly formed around his initiative, resulting in a NOAA-endorsed vocabulary of Spanish-language terms for weather risks. Previous attempts to translate words such as “tornado” and “hail” only caused more confusion because they were not universally understood across all dialects, Trujillo Falcón says. But the team’s use of linguistics experts helped break through those barriers, and the vocabulary currently is being put into practice nationwide.

“Joseph is at the forefront of the effort to do a better job of getting information about hazardous weather to the immigrant population,” says Justin Reedy, OU associate professor of communications and Trujillo Falcón’s co-adviser. “He’s already doing great work, and he’s going to be making many more contributions to this field in coming years.”

Now, Reedy, Trujillo Falcón and other team members are focusing on NOAA-funded field research in western Kansas and the Houston area, as well as a national, online survey to learn more about cultural barriers disrupting weather awareness.

“This is a big, three-year research effort to gather field information on communication and language connections across communities,” says Reedy, who is leading the project involving people from Spanish-speaking communities around the country.

Trujillo Falcón says the work they are doing was a dream that originated when he was growing up, watching his family and friends struggle to understand the English-language media when severe weather rolled through. This long-term career goal wasn’t something he expected to begin while still in graduate school.

But strong affirmation from the meteorological community has shown how seriously experts regard the issue.

“It’s heartwarming,” he says. “The reason I do this work isn't for national recognition or for accolades. It's for those immigrant communities that I was raised in.”

“That's why I initially wanted to be a broadcaster. I wanted to help these communities. But as I went through college, I realized there wasn’t a long-term solution.”

JosephTrujillo Falcón on the roof of the National Weather Center on OU’s Norman campus.

LEARNING WHY THE

TINIEST PARTICLES SPIN

IN PAIRS–AND HOW TO MAKE THEM–HOLDS PROMISE FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES.

BY LAUREN EMERSONIF YOU GO ON A WALK WITH A FRIEND, you might find that, at some point along the way, you’ve unintentionally begun to walk in sync. Likewise, you may have observed a field of blinking fireflies and noticed that they seem to blink at the same time. Just like friends and fireflies, atoms can synchronize with other atoms, and understanding this phenomenon will shed light on many unanswered questions about quantum mechanics.

University of Oklahoma physics professors Doerte Blume, Grant Biedermann and Alberto Marino are leading a three-year research project to advance our understanding of quantum synchronization, which may have an impact on the future of quantum technologies. The project is led through the OU Homer L. Dodge Department of Physics and Astronomy and the Center for Quantum Research and Technology. Their research is being funded by a $1 million grant from the W. M. Keck Foundation, and its main goal is to develop a quantum network of atoms that will help reveal how collective interactions at the quantum—or smallest measurable—level lead to synchronization.

The project, which aims to address fundamental research questions, has practical implications for network synchronization over fiber optic and wireless channels, like allowing two computers to connect wirelessly over long distances. It may also enable the development of advanced computer chips that can store more information in a smaller amount of space. One thing is for certain: fundamental research and technological advancements go hand in hand, and the team is excited to see where their findings will lead them, Blume says.

Quantum synchronization is exactly what it sounds like: interacting particles will sometimes synchronize their spin and motion. The quantum mechanics—or interaction of matter and light at the atomic level—associated with synchronization aren’t fully understood, even when it comes to defining what “synchronization” means at such a small scale.

“What even is synchronization at the quantum level?” reflects Blume, a theorist interested in developing an understanding of quantum mechanical systems. These fundamental questions intrigued her. “How do you define synchronization within the quantum framework? The reason that’s not so obvious is that, quantum mechanically, you always have uncertainty. You can’t have something at exactly a given spot.”

While Blume heads the theoretical branch of the project, Biedermann and Marino provide experimental expertise. Biedermann specializes in implementations of quantum information processing in neutral atom systems, through which atoms have no electrical charge, while Marino specializes in quantum optics—the study of the quantum properties of light and the interaction of quantum light with atoms and molecules. The researchers plan to use cold atoms to create a synchronized quan-

Physics professors Grant Biedermann, left, Doerte Blume and Alberto Marino lead a threeyear research project to advance understanding of quantum synchronization.

tum network in which the appearance of synchronization in atoms can be studied.

To create a quantum network, the researchers must be able to isolate atoms. Trapping an atom with a laser sounds like something that only happens in science fiction, but it’s a reality in physics labs. Tools called “optical tweezers” use tightly focused beams of light to hold a single atom in place. Researchers can then manipulate those atoms. “Now we have the ability to create entangled states between multiple atoms,” Biedermann says. “That’s all done with these optical tweezers.”

Once the atoms in the tweezers are made to oscillate at a specific frequency, researchers propel them to interact with one another through electrostatic forces. This allows the atoms to “feel” each other’s motion to some degree and develop synchronization.

Researchers use light to oscillate atoms at the chosen frequency. “The light will introduce forced oscillation,” Biedermann says. “It’s like taking a pendulum and forcibly swinging it back and forth to make it oscillate at the frequency you determine.”

This can be accomplished with a large amount of “normal” light or with a smaller amount of quantum light—specifically “squeezed light.” Squeezed light has special properties that relate to quantum entanglement and can more effectively interact with atoms than normal light, Marino says. Essentially, it’s better at making the atoms vibrate the way researchers want them to with less uncertainty. Marino has been creating quantum light for more than a decade, and with some small modifications, that light can be applied to the single-atom systems in Biedermann’s lab.

“This quantum synchronization project is really coming at the problem from a whole new angle,” Biedermann says. “Most of the work people are doing in the realm of quantum control either deals with quantum simulation, or they’re approaching it with the goal of building a quantum computer. We’re more interested in the dynamics of how quantum information develops, how it evolves and what type of control we actually have.”

In the long run, an increased understanding of quantum synchronization and quantum mechanics will be used to develop and refine quantum technologies such as computer chips and fiber-optic links. For now, OU’s research team is focused on the crucial steps of establishing the building blocks of quantum synchronization knowledge.

“We don’t actually have a clean, underlying framework that applies to all systems,” Blume says. “We don’t have enough theory, insight and experimental data yet. And when I say ‘we,’ the ‘we’ is all scientists.”

OU has a decades-long history of working with ultra-cold atomic systems, so this project fits perfectly into the greater picture of OU physics research, says Blume. The high-quality lab space at Lin Hall, named for and supported by a major gift from former OU physics faculty member Chun Lin, is perfectly suited for such experiments because its laboratories are designed for sensitive measurements, Blume adds.

Innovative investigations are at the core of what OU research is about. “This kind of basic research into the state of how and why atoms interact is fundamental to paving the way for the revolutionary quantum technologies of the future,” says Tomás Díaz de la Rubia, OU’s vice president for research and partnerships. “Achieving quantum synchronization will enable a myriad of future technologies—like improved quantum networking— and truly pave the way for an exciting future.”

The project wouldn’t be possible without student contributions, Blume points out, adding that students also gain experience and the reward of seeing their hard work come to fruition.

“Grant Biedermann, Alberto Marino and I are not doing this on our own,” she says. “The majority of the funding is going toward supporting and training graduate

students, undergraduate students and postdocs. That’s really the core mission of the university.”

The team is also building an entirely new research apparatus that is extremely innovative and will serve OU physics research for decades to come, Blume says.

“The apparatus will use an atomic species that has much longer lifetimes. It will allow for unprecedented control that goes way beyond the team’s current capabilities, making it easier for different sub-units of the quantum network to interact.”

Their work will bring researchers and quantum physicists closer to understanding the mechanisms of quantum synchronization and creating more advanced quantum technologies.

“There’s so much information embedded in these quantum information systems that we don’t have tried-and-true rules to help guide us to understand what’s useful and what’s not useful,” Biedermann says. “It’s uncharted territory. We’re still kind of navigating the open oceans here.”

The W. M. Keck Foundation was established in 1954 in Los Angeles by William Myron Keck, founder of The Superior Oil Company. One of the nation’s largest philanthropic organizations, the W. M. Keck Foundation supports outstanding science, engineering and medical research.

“It’s like taking a pendulum and forcibly swinging it back and forth to make it oscillate at the frequency you determine.”Lauren Emerson is a strategic communications specialist for the University of Oklahoma Foundation. Individual cesium—or strontium atoms—held in optical tweezers, depicted as simple harmonic potentials. The atoms are synchronized, schematically illustrated by curved pink lines. TRAVIS CAPERTON

AGLOW AGAINST A cloudless black sky, the University of Oklahoma’s recreation fields buzz with students’ cheers and jeers as a half-dozen soccer teams face off on a cool evening.

A year ago, the fields would have been dark and quiet at this hour.

Recent installation of new LED lighting for the recreation fields—thanks to funding from the OU Student Government Association—means students can now play well into the night, creating more opportunities for participation.

Before, games had to be crammed in before sunset, which meant kickoff times often clashed with students’ academic schedules or mealtimes.

Joining an intramural team was a natural fit for Morgan Casillas, an OU advertising senior from Tulsa, Okla., who has played intramural soccer for three years and grew up playing the sport. Now, after long days of classes, she and her friends have extra hours to unwind on the field.

“I love it,” Casillas says. “It just allows more time for us to be out here, and it’s more flexible with our schedules.”

OU’s recreation fields are finally lighted, and students are basking in the playful possibilities.

Students and staff celebrated the first action under the lights with 8-on-8 soccer matches on Feb. 6.

“It’s been fun—a three-letter word to sum it up, it’s been fun. It’s been absolutely amazing,” says Amy Davenport, the director of OU Fitness and Recreation.

“The night the lights were turned on, one of our student employees grabbed a football, looked at another employee and said, ‘We have to throw the ball under the lights!’ ” Davenport recalls. “It was really neat to watch their excitement.”

Lighted fields had long been on OU Fitness and Recreation’s wish list.

“OU was one of the only schools in the Big 12 and the SEC without lighted recreation fields for students,” Davenport says.

Research backed up the demand for lights and the additional extracurricular opportunities they would create: At 4 p.m. Monday through Thursday, more than 10,000 OU students were still in their academic classes during the fall 2021 semester. Days become shorter throughout the semester as natural light wanes.

Students overwhelmingly wanted the opportunity to be outdoors and play sports after the

Intramural sports also help students build community, she says. Through sports, students who might not otherwise cross paths come together.Flag football under the lights. Fit and Rec Director Amy Davenport and Dean of Students David Surratt at the inaugural night game.

sun went down, they responded in an OU survey.

Fitness and Recreation took the data to the Student Government Association, or SGA, which ultimately decided to fund the project.

Their support provides not only more opportunities for students to play, but also more opportunities for student employees to officiate, Davenport says.

Plus, more playing hours means popular sports like flag football, a fall semester favorite, can now be offered during the spring, too. Soccer, which normally starts in March, was able to get underway about a month earlier this year.

“SGA made a huge impact on student lives by funding this project,” Davenport says. “It’s so much more than play—it’s health. It’s wellness. It’s teamwork. It’s communication.”

Intramural sports also help students build community, she says. Through sports, students who might not otherwise cross paths come together.

When Jerry Bruns arrived on OU’s Norman campus from New York in 1990, he didn’t know a single person in the state, he says. Playing intramural sports—just about every one that was offered—was how he made friends and found his community.

“Intramurals were probably the best part of college for me,” he says. “I loved it.” Bruns, who now owns a Play It Again Sports franchise selling new and used sports equipment in Norman, was happy to hear about the new lighting system and what it means for future generations of OU students.

Since games won’t have to start so early, “it takes away a lot of that burden of finding people to play a sport with you,” he says. “I think it’s a definite positive.”

Brian Limekiller, a political science senior from Tulsa, has played intramural sports for most of his time at OU, including soccer, softball and basketball. It was tough to find times when a group of students could all meet for early games.

A player heads the ball during intramural soccer. Lighting means that OU students can enjoy intramural sports throughout the year.

“Being able to play later—7:30, 8, 9—I think it’s a great improvement,” he says, walking away at the end of a soccer game on the newly lighted fields. “Intramurals cover a lot of different groups of people. I think the installation of lights will make it accessible to many more people.”

Even students who haven’t played intramural sports before are making use of the new opportunities. Jack McGowan, an OU nursing senior from Fort Worth, Texas, joined one of his first games after a friend asked him to fill a spot on their soccer team.

McGowan says he got to help a friend, and he benefited, too: The fresh air and exercise was a perfect stress-reliever, especially since he had a capstone project presentation the next morning.

“That’s why I’m out here,” he says. “Just having a good time.”

SOONER WORKS LAUNCHES ITS FIRST GRADUATES WITH LIFE SKILLS,

FRIENDSHIPS AND A PRICELESS OU EXPERIENCE . BY

TAMI ALTHOFF

BO COCHRAN LOOKS down at his fitness watch.

It’s 11 a.m. on a Tuesday, and he’s already logged a significant number of miles.

“I like to do my exercises,” he says, adding he walks an average of 12 miles a day.

Cochran logs many of those steps through his internship with the Pride of Oklahoma Marching Band. As a member of the logistics team, he helps set up for practices and provides support on game days. The rest are acquired walking around the University of Oklahoma’s Norman campus, where he attends classes, and at the Jimmie Austin OU Golf Club, where he earns tips cleaning golf carts.

Internships, classes and living on campus may seem like routine activities for a college student, but for Cochran, the opportunity is a gift made possible through Sooner Works, a program that began in 2019 with just three students— Cochran and cohorts Madison Mason and Peyton Dumas.

An inclusive, post-secondary education (IPSE) program for students with mild to moderate intellectual and/or developmental disabilities, Sooner Works allows uniquely abled students the opportunity to attend classes, hold a job and even be a part of fraternities, sororities and other student organizations. Students live in OU residence halls and, in some cases, apartments or rental homes.

Sooner Works, which is recognized as a comprehensive transition program by the U.S. Department of Education, is offered through the OU Zarrow Institute on Transition & Self-Determination.

Based on similar offerings at universities like Clemson and Texas A&M, Sooner Works is a four-year certificate program featuring mainstream OU courses, along with a specific Sooner Works curriculum to help students develop life skills necessary to thrive while living and working independently. Each student participates in internships either on or off campus, with juniors and seniors holding paid internships.

“We like to say this program is the next stage of inclusion at the university level,” says Kendra Williams-Diehm, Zarrow Institute director. “We have high expectations for our students and they are held accountable. It’s not a charity, feel-good organization. It’s a college program, and our members are 100% OU students.”

There are currently 24 students in the four-year program, and eight freshmen are set to begin next year. While there is capacity for 48 students, Williams-Diehm says funding doesn’t yet support those numbers.

Rylee Murray, Sooner Works social worker and instructor, says to qualify for the program students must be between the ages of 18 and 26 and diagnosed with an intellectual and/or developmental disability.

“Students who would be a great fit would also have the motivation to be successful as a college student, the ability to live independently, the capability to adapt to change, no significant behavioral or emotional difficulties, and a basic understanding of reading and writing,” says Murray. “We have accepted students with a wide variety of disabilities including, but not limited to, Autism Spectrum Disorder and Down Syndrome.”

Cochran, a percussionist, has focused on music courses and honing his conducting skills while at OU. He plans to continue working with the OU School of Music after graduation.

“Bo speaks in music,” says his mom, Kari Cochran. “There is something very organic about how he can relate to music and apply the skills he’s learned. If there was a way, we would have him continue in any and all music classes available. For Bo, it is a natural extension of himself to take music classes and be involved in OU’s music program.”

Peyton Dumas says his coursework has focused on health and nutrition. He interned at OU’s Sarkeys Fitness Center and, like Cochran, enjoys exercise.

“I want to become a fitness instructor,” he says. “I was overweight when I was younger, so I work out a lot. I feel a lot better.”

Dumas also spends significant time with his fraternity, Brothers Under Christ (BYX), and participates in OU’s annual Sooner Scandals music revue. He says he enjoys acting and hopes to join a community theater after graduation.

“Often these students have been told that they cannot do many things in life, including going to college,” Murray says. “I see their added motivation to succeed and overcome barriers that many thought would be impossible. I have seen so much growth in them throughout their time in the program.”

Another way Sooner Works helps integrate its members with other OU students is through an affiliate program, Peer Partners. OU students can volunteer with Peer Partners, serving as mentors to Sooner Works participants.

Madison Mason, who is enthusiastic and social, says the partners are a special

“Often these students have been told that they cannot do many things in life, including going to college. I see their added motivation to succeed and overcome barriers that many thought would be impossible. I have seen so much growth in them throughout their time in the program.”Chris Loerke and Madison Mason at an OU home football game. Bo Cochran and family celebrate his acceptance into OU’s Sooner Works program. Bo Cochran on the first day of classes August 2021. Sooner Works senior Peyton Dumas.

—RYLEE MURRAY

part of Sooner Works. She remembers her first experience as a new student.

“In August 2019, we did Move-In Day. I moved in and my family helped set my room up. It was exciting,” she says. “I got to do a campus tour with my male Peer Partner, Chris Loerke. He showed me around, where the museum is, and all the history.”

Mason says she appreciates going out to lunch, dinner and movies with her partners.

“We also do Halloween parties, Valentine’s Day parties,” she says. “I enjoy dressing up and having fun.”

Kimrey Klamm is the student socialization intern for Sooner Works. An early childhood education junior, Klamm found out about Sooner Works and Peer Partners when she had a class with one of the students her freshman year.

“I immediately knew that this was something I wanted to be a part of. I quickly became acquainted with Peyton, Bo and Madison. From the moment I met each of

them, I knew Sooner Works was special because of the people they selected to be in the program,” she says.

“Peyton always has a joke and is ready to hang out or work. Bo is quick to tell you about his music, and he is always

ready to smile or dance. Madison refers to herself as ‘The First Lady of Sooner Works.’ She comes to every event with a smile on her face and makes sure that everybody is happy and having a good time. To say work-

“I think Sooner Works is an incredible opportunity because it allows the partners to learn to work with all kinds of students and to take an active role in making OU a more inclusive campus.”

—KIMREY KLAMMSooner Works students at a going away party for founding associate director Mindy Lingo, center.

ing with these three students has been amazing is an understatement.”

Klamm says Peer Partners provide Sooner Works students with both friendship and advocacy on campus. She says most students have at least three partners, with a goal of spending time with a partner at least once a week. More than 100 OU students have expressed interest in being a Peer Partner.

“My personal goal for each Sooner Works student is for them to know they have friends on campus who support them,” Klamm says. “I think Sooner Works is an incredible opportunity because it allows the partners to learn to work with all kinds of students and to take an active role in making OU a more inclusive campus.”

Since starting the Sooner Works program, Mason has moved to an apartment off campus and learned to navigate Norman using the city bus system.

Dumas has entertained the idea that it might be possible to become a professional actor.

Cochran has forged a friendship with Mason that he says will last a lifetime, learned to love his independence, and created a dream job for himself in instrumental music conducting.

“I am hopeful that nontraditional avenues may arise that can help him reach this goal,” Kari Cochran says. “He has made so many friends and connections in the band programs at OU; as these individuals enter into their post-graduate worlds, I believe they will open doors for Bo that we have not even thought of.”

In May, Mason, Dumas and Cochran culminated their time with Sooner Works by participating in the pinnacle of the college experience—graduation. All three were excited about senior pictures, trying on caps and gowns, taking part in Commencement and earning their certificate of completion.

They’re also eager to see what they can achieve beyond college, as are their families.

“We had planned for Bo to be with us for a lifetime. That he can now be independent

and has the voice to advocate for himself is amazing. Sooner Works has provided an avenue for him to achieve these things,” Kari Cochran says. “If you had asked us four years ago whether he’d be able to accomplish what he has, Bo would have said yes, and we would have been hesitant. I hope he always proves us wrong with his accomplishments.”

Williams-Diehm says her staff has learned just as much from Sooner Works students, especially the inaugural cohort.

“This first class has helped us so much. Their parents have been supportive and forgiving, and we are so grateful for that,” she says. “I can remember these three as freshmen, and we all sat in the office wondering how this was going to work. Now to see them independently maneuvering around town, it’s wonderful. They’ve gone through that college transformation, and they’re ready to become adults. They are totally trailblazers.”

The divide between heavymetal music and classical opera isn’t insurmountable for OU voice professor Joel Burcham.

BY SUSAN GROSSMAN TRAVIS CAPERTON

BY SUSAN GROSSMAN TRAVIS CAPERTON

, MTV and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart led to Joel Burcham becoming a tenor, a teacher and a heavy-metal composer. Whether it’s the screaming, energetic guitars of Pour Some Sugar on Me by Def Leppard or the dark drama of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, the University of Oklahoma associate professor of voice and opera coach says the combination of seemingly disparate influences shaped him from an early age.

“I wanted to be a professional musician ever since I could remember, especially a guitarist,” he says. “I thought that over-driven rock guitar was the coolest music I had ever heard. It was exhilarating. Whether my parents loved it or not— and they didn’t—I did. And next to the

operatic classical voice, I think it is still the coolest.”

As a 1980s kid growing up in the heart of Illinois farm country, Burcham idolized the guitar gods of heavy metal bands like Quiet Riot and Metallica. He immersed himself in rock music, listening to metal on the radio, watching music videos on MTV, and playing cassette tapes he received via a monthly club subscription. He envisioned himself one day fronting his own band; on lead guitar, of course.

“My love of music is directly linked to hard rock and heavy metal because I heard that first,” he explains. “I was a hyperactive kid, and the hyper-energy of this music matched my own as a child, as well as my musical skill set and aspirations to be a performer.”

When he saw the movie "Amadeus" in 1984, Burcham says he was transformed. Loosely based on the life of Mozart as told by jealous fellow composer Antonio Salieri, the Academy Award-winning period drama tells the story of a bitter rivalry set to Mozart’s music.

“That movie changed my life,” he says. “Mozart’s works came alive and made classical music accessible to me. After that, I went on a classical music binge. I wanted to be an opera star.”

Burcham’s dream of fronting a rock ‘n’ roll band was put on hold. He became a front man of a different sort as a classical opera performer.

Sooners may have heard him singing incredible renditions of "The Star-Spangled Banner" at various sporting events, performing in operas staged at OU, and with the Oklahoma City-based Painted Sky Opera. In addition, Burcham has sung numerous roles

around the United States, including for the Utah Opera, Colorado’s Central City Opera, Opera Omaha in Nebraska, Madison Opera in Wisconsin, and Tennessee’s Knoxville Opera. He is also a prolific concert soloist and recitalist. His operatic repertoire is vast, and he speaks German, French and Italian.

Burcham also writes, performs and records original heavy-metal compositions under the name “Thlipsis” and has served as a vocal coach for local Oklahoma heavy-metal bands such as Locust Grove, Sign of Lies and Perseus.

This future balancing act between opera and rock wasn’t always obvious. Burcham studied piano, sang in choirs and participated in school musicals while growing up. After earning both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in vocal performance, he spent two years as a music teacher for mental health facilities.

“I found the work to be exhilarating,” he says. “However, the amount of paperwork you have to do in that field drained my enthusiasm and I knew I couldn’t do it for a living.”

Burcham pursued a doctorate in musical performance at the University of Wisconsin. During a residency with the Utah Opera and Utah Symphony, he paused his doctoral program for a taste of the sacrifices required to become a professional opera singer.

“At that point, I did not like singing because of what it was costing me in my personal life,” he says. “I was married and knew I wanted a family. Opera life is lived out of suitcases on the road. I realized then the doors that have consistently opened for me have been in academia, so I returned to Wisconsin to finish my degree.”

After six years teaching at the University of Colorado, Burcham arrived at OU in 2013. A decade later, he still loves his job. There’s student recruitment; weekly, individual lessons with 15 students; plus a one-hour studio class, during which voice majors gather to perform and critique each other.

Burcham feels a great sense of fulfillment watching his students grow as they adapt his teaching methods and techniques to their voices. “There are tenors I’ve taught who are better than me, and I take great satisfaction when they do bigger things, as well.”

First-year doctoral student and tenor Matthew Corcoran will be apprenticing this summer at the world-famous Santa Fe Opera, serving as an understudy for the lead role of Cavaradossi in “Tosca” by Giacomo Puccini.

“My love of music is directly linked to hard rock and heavy metal because I heard that first. I was a hyperactive kid, and the hyperenergy of this music matched my own as a child, as well as my musical skill set and aspirations to be a performer.”

“I would not have this huge opportunity without Dr. Burcham,” says Corcoran, a Lowell, Mass., native. “He is on par with the best in the profession due to his knowledge, passion and love for teaching. Dr. Burcham has a way of conveying concepts and speaking to students that is respectful and helpful. Classical music is like Bordeaux wine. All the aromas and flavors develop—much like the voice— with age, and he is very skilled at teaching me how to shift what my voice is capable of doing.”

Kayla Marshall, a Midwest City, Okla., master’s student in musicology, recalls her first voice lesson. After a few scales, Burcham suggested her range was that of a coloratura soprano, the highest of all vocal ranges, rather than the soprano Marshall thought she was.

“I remember when I disagreed, he told me he was the professor, then handed me a book to read about it,” she says. “He was right. Dr. B has a lot of respect for his students. When it’s time for class, he usually has a grasp on how your day is going. Sometimes he says, ‘We just need to sing.’ I trust him, and he is preparing us to be as successful as humanly possible.”

Burcham also gets to share his love for rock with OU students. He teaches a survey course, “Music in the Rock Era: Heavy Metal,” geared toward non-music majors, and has inspired like-minded fans such as Corcoran.

“The best singers can do many different styles, and a well-rounded musician can change the timbre of their voice,” Corcoran says. “There are different techniques used in death-metal screams, for example, that I can do.”

Burcham still maintains hope that he can make a mark in the rock world, just as he has in opera. He continues to write and record rock and metal music and has plans to seek grant funding to produce an album, adding even more diversity to the OU School of Music and its voice program.

“The thrill I get from classical music and high-energy rock and metal is the same,” he says. “They are both loud and, as a natural extrovert, the energy of both matches my personality—I get chills across my entire body and attack my operatic singing and training as if I really was a rock guitarist.”

At three Norman Public Schools' sites, some superheroes wear OU men’s gymnastics, soccer and Pride of Oklahoma Marching Band uniforms.

BY J AY C. UPCHURCH

BY J AY C. UPCHURCH

all started as an innocent e-mail from a local teacher to a collegiate coach.

Over the past 17 years, that simple e-mail has blossomed into a series of rewarding partnerships between University of Oklahoma students and Norman public elementary schools that could be used as the blueprint for mentorship programs across the country.

Since 2005, thousands of Cleveland Elementary School students have been impacted by regular classroom visits from members of the OU men’s gymnastics team, student-athletes who give generously of their time and energy and who often become positive role models. That program also has inspired two new mentor partnerships between OU’s soccer team and Adams Elementary and The Pride of Oklahoma Marching Band and Kennedy Elementary.

“I thought it was something that had a lot of potential,” OU men’s gymnastics coach Mark Williams reflects on his team’s relationship with Cleveland Elementary. “To be honest, it’s probably one of the best decisions we’ve ever made regarding our program.”

“Once we got it going, it really took off,” says the author of that original e-mail, program founder and former Cleveland Elementary School music teacher Regina Bell. “Everyone involved embraced it—the kids, the teachers and the entire school, plus all the gymnasts.”

Asking his student-athletes to find time to squeeze a mentorship program into their already-demanding school and training schedule was no simple request. But Williams has seen how the positives far outweigh any negatives that might exist.

“The partnership we have built with Cleveland Elementary has had a long-lasting impact, not only on our success in terms of community outreach and fan participation, but also in the fact my guys have been changed in so many positive ways thanks to the relationships they’ve built with those young students,” he says.

“It warms my heart that my team members have always been willing to give of themselves to these kids, especially knowing how much of a difference their presence has made for so many of them.”

The Cleveland program blueprint—which has been followed by Adams and Kennedy—assigns a classroom to each OU gymnast, who in turn devotes

an hour or two each week to helping with everything from tutoring kindergarten to fifth grade students in the classroom to participating in various games and activities at recess.

The gymnasts also perform during school assemblies, and OU invites the entire school to what has become known as “Cleveland Night,” a regular-season gymnastics meet where students help run the evening’s festivities, handing out awards and escorting the OU gymnasts during introductions.

For its part, the OU soccer team hosted a special “Adams Night” at one of its home games this fall, an event that drew an estimated 800 additional fans made up mostly of Adams students, teachers, administrators and their family members. Students decorated the stands with homemade signs, and the Adams choir opened the pregame ceremony by singing the national anthem.

Kennedy Elementary officially launched their partnership with the Pride by attending one of the band’s November rehearsals, where they provided members with cookies and drinks.

“The kids treat us like celebrities. It can be pretty humbling at times,” says fifth-year senior gymnast Spencer Goodell of Tigard, Ore. “The best part of the experience is feeling like you can influence their lives. And just knowing that has definitely changed my life in a positive way, as well.”

Goodell’s insight has become a recurring theme over the years.

“I think knowing they have all of those little eyes watching their every move really brings out the best in the gymnasts,” says teacher Megan Allen, who currently coordinates the Cleveland program. “The kids see them as superheroes, and that’s a lot to live up to.”

Second grade Cleveland teacher Jessica Trent has seen the positive impact the program has had on many of her students.

“To be honest, it’s probably one of the best decisions we’ve ever made regarding our program.”

—MARK WILLIAMS

“For as long as I’ve been here at OU, we’ve had various teams go to local elementary, middle and even high schools to participate in reading programs and mentorship programs that positively impact young students. Having this type of influence on the community is something we feel very strongly about.”

J OE CASTIGLIONEBand members James Francisco and Chloe Kelly dance with students at the Kennedy Elementary Snow Ball. OU gymnasts and mentors get high fives from Cleveland Elementary students before competing. Goalkeeper Makinzie Short talks Adams students through their work. ERIKAH BROWN THERESA BRAGG

“Having an additional role model in the classroom can be inspirational in so many ways but can really make a big difference for some of the students who don’t come from great backgrounds.”

According to Director of Athletics Joe Castiglione, OU student-athletes perform, on average, around 5,500 hours of community service each year. He believes mentorship programs serve a greater purpose.

“For as long as I’ve been here at OU, we’ve had various teams go to local elementary, middle and even high schools to participate in reading programs and mentorship programs that positively impact young students,” says Castiglione. “Having this type of influence on the community is something we feel very strongly about.”

Bell Johnson points to Cleveland’s mentorship program as one of the main reasons she made the decision to pursue a future in gymnastics while still an elementary school student.

“I was fortunate enough to develop a great relationship with several of the gymnasts, and I kind of grew up around those guys,” says the Norman native, currently a junior on OU’s national champion women’s gymnastics team. “It definitely helped inspire me to take gymnastics more seriously, and to eventually come to OU.”

Although still in their infancy, there have been plenty of signs of success for the Adams and Kennedy programs, as well.

“We’re excited about the possibilities,” says Heather Murphy, Adams’ school counselor and mentorship sponsor. “It’s been so great to see our students forming relationships with the players and really looking forward to that part of their week.”

“I like it when the soccer players come to our class and help us with our schoolwork,” says Saylor Jones, an Adams kindergartener. “They sit with us and read, and sometimes play games with us. It’s so much fun.”

Participation in the mentorship programs is not mandatory for OU students, but all three partnerships have enjoyed solid support from student-athletes and band members, Castiglione says.

“The impression that Pride members have made on our students so far is profound,” says Kevin Russ, a former OU band member who is a first-year teacher at Kennedy. “Whether it’s talking about music or listening to a mentor play their instrument, the kids love the time they get to share when the band members are in our classrooms.”

Norman Public Schools District Superintendent Nick Migliorino is hopeful more mentorship programs involving OU and local schools could be on the horizon.

“What a blessing it is to have a major university in our backyard, and especially to have them get involved with our schools and help inspire and lift up young students,” says Migliorino. “There are so many levels of positives. We will always be open to these types of partnerships and to any of the coaches and athletes who are willing to invest their time and efforts in our schools.”

IN OCTOBER 1950, David Burr, a brand-new graduate about to embark upon a career of incomparable service to the University, offered a tribute in this magazine to a favorite teacher. She was an assistant professor of modern languages named Eugenia Kaufman, and she deserves our attention for two reasons. She was notable for what another of her former students, University College’s Dean Glenn Couch, called “her capabilities as a teacher and as a human being.” And she serves as a sobering reminder of how unmarried women teachers were treated by this and other universities.

Eugenia Kaufman was born in Leon, Kansas, on February 2, 1889. When she was nine, her parents and older brother Kenneth moved to the Cherokee Strip and then to a farm near Weatherford, Okla. In 1904, she joined her brother at Southwestern Normal School, practically walking distance from the farm. She planned to become a math teacher, but a brilliant new professor of German appeared at Southwestern, and, as Burr put it, the arrival of Roy Temple House “dates the advent of Miss Kaufman’s interest in foreign languages,” and from that time on, “it has been her work.”

In 1910, armed with a “certificate,” she began teaching

in small-town high schools. Summers were spent studying in Norman, where Professor House relocated in 1911. In 1917, Kaufman received her bachelor’s degree (later doing summer studies at the universities of Mexico, California, and Chicago). OU hired her as a teaching assistant (1919), an instructor (1920), and an assistant professor (1927). For thirty-seven years, she taught German, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. During the final years of her career, her classes met in “Kaufman Hall,” named after her brother Kenneth, who’d become an honored teacher, literary critic and editor.

Kaufman’s life was her teaching. Another of her students was Savoie Lottinville, later director of the University Press. “She was never content to teach merely the mechanics of the language,” he told David Burr, “but to imbue the student somehow with the spirit of the literature.” She had a special regard for returning World War II veterans, but valued every student and offered her help to each. She was the sort of teacher who took counseling seriously; the sort that brought flowers to class from her famous garden and invited students home for ice cream and cake after the final exam. A departmental evaluation in 1952 described her as, “not only a fine teacher but also a sympathetic counselor and friend of long standing to a whole generation of university students … She is, in short, a knowing, kindly, and gentle soul.”

On the other hand, Kaufman was so absorbed by her teaching and counseling that she sometimes neglected other duties. After twenty years, her mentor, Professor House, described her as “very loyal and responsible, tries hard to be punctual, but is forgetful and constitutionally unable to budget her time. Very intelligent, industrious, helpful

to students. Would be useful on committee work if it were not for her forgetfulness.” She might have smiled at those comments if she had ever gotten to read them.

Like other single women, Eugenia Kaufman was never rewarded to the extent warranted by her merits. She was held at the rank of assistant professor for twenty-five years, making her (along with one other individual) OU’s longest-serving assistant professor. Her department’s plea for promotion in 1952, “if only on the grounds of common humanity,” was finally approved shortly before her retirement. Kaufman’s nine-month salary in 1927, her first year as an assistant professor, was $2,200 (roughly $37,000 in today’s dollars). Eighteen years later she was still being paid $2,200, and at her twenty-fifth year as an assistant professor and thirty-third as a faculty member, she was paid $4,200—about $46,000 today. A green, new assistant professor today would be paid almost double what OU paid her after decades of superb service. The injustice was based on the belief that single women did not have the same financial needs as men, a belief never applied to single men.

As she was about to retire, her chair wrote: “She is not … a woman who ardently seeks material rewards; rather, her deepest satisfaction must be found in the grateful hearts of generations of students who have known and loved her, but who haven’t always taken the trouble to say so. To have inspired such loyalty and personal devotion could well be the desideratum of all of us.” In poor health, Eugenia Kaufman announced her retirement on her sixty-eighth birthday. She died in January 1963.

W. Levy is Professor Emeritus of the OU History Department and has written two books on OU history.

Envelopes were torn open and graduating students from the OU College of Medicine and OU-TU School of Community Medicine

celebrated with family and friends during Match Day as they discovered where they will spend their residency training.

The University of Oklahoma Foundation Inc.

100 Timberdell Road

Norman, Oklahoma 73019-0685