7 minute read

Observed Trends in Maximum Temperatures in Northwest Mexico

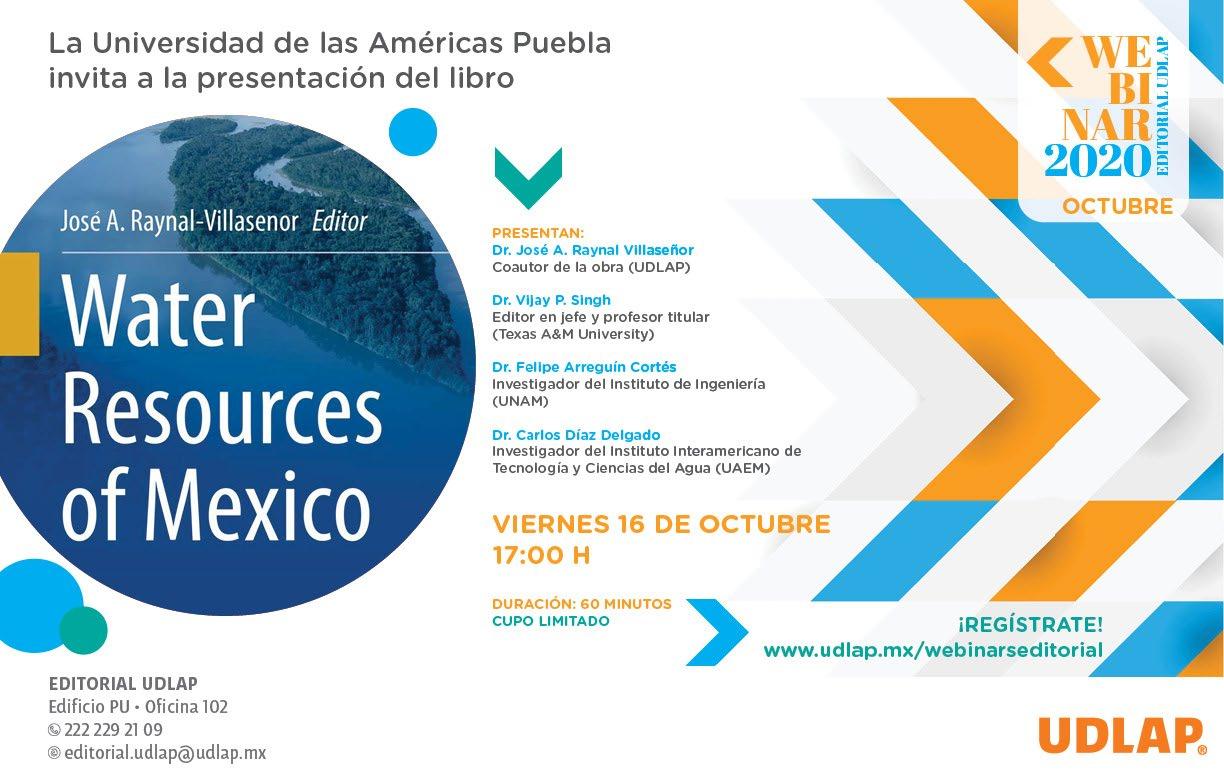

BOOK PRESENTATION:

WATER RESOURCES OF MEXICO

Through the webinars organized by the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (udlap) publishing house, the “Water Resources of Mexico” book by Dr. José A. Raynal Villaseñor, professor at the Universidad de las Américas Puebla and member of the unesco Chair on Hydrometeorological Risks, was presented. This new publication is a reference for scholars and decision makers since it unites renowned specialists and experts regarding the water problems of the country.

This comprehensive volume, edited by Springer, presents the topic of water resources of Mexico from a different angle. During the webinar introducing this work, Dr. Raynal Villaseñor stated that this book is the summary of two and a half years of work by the authors of the 15 chapters included in the publication. Besides covering geohydrology, “Water Resources of Mexico” also offers a brief account of ancient water resource works such as the chapter written by Dr. José Raynal on hydrological and hydraulic works of the Aztec civilization. In addition, other academic researchers from udlap discuss topics such as data models for river basin management in Mexico, climate change and hydraulic sources, and the possible scenarios created by the impact of global warming on evaporation in Mexico.

This book is part of a series entitled “World Water Resources” edited by Dr. Vijay P. Singh, a tenured professor at Texas A&M University, who during this presentation shared that the series was developed after realizing that water safety is one the challenges of the 21st century. As such, to achieve water sustainability, water safety had to be addressed from three essential perspectives: environment, economy, and society. Then, he explained that, by addressing these topics, each book in the series seeks to contribute to the abovementioned change and foster the development of water sciences, particularly, in each region as in the case of the edition dedicated to Mexico. Dr. Felipe Arreguín Cortés, a researcher at the unam’s Engineering Institute and a co-author, also participated in the event. He emphasized that the book is well focused and offers current solutions. Therefore, it is a well-prepared book. “The first three chapters carefully review the surface and underground hydrological issues in Mexico, including aspects we need to solve the large problem we face regarding the overconcession of surface waters and overexploitation of aquifers. There is another very important chapter on the water–energy–food chain, which is currently necessary as we need more food and energy supplies. In fact, this chapter is addressed at a high level with technical precision.” The preceded part in quotes is the argument of Dr. Felipe Arreguín Cortés. Dr. Carlos Díaz Delgado, a researcher at the uaem’s Inter-American Institute of Water Science and Technology and co-author of the chapter on the water–energy–food chain, stated that the mentioned publication could be considered a masterpiece on water science in Mexico “for its magnificent content and treasures for supporting strategic decision-making aimed at building a more sustainable nation. The book has been enriched by the knowledge cultivated and accumulated over many years by a team of 31 authors carefully selected by the editor. The knowledge contained in the book has been compiled within the boundaries of 15 chapters in just 288 pages,” as asserted by Dr. Carlos Díaz Delgado.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON “WATER RESOURCES OF MEXICO,” VISIT:

CHAAC AND HIS TORCH: THE MAYANS AND CLIMATE

UXMAL RODRÍGUEZ MORALES

Great builders, inventors of the number zero, exceptional astrologers, maiden sacrificers, and predictors of one of the many ends of the world etc. This is how the pre-Columbian Mayans are recognized, one of the American cultures that most fascinates mankind. The interest in this ancient civilization has flourished, especially, but not only motivated by everything related to its calendar and the year 2012. One of the mysteries surrounding the ancient Mayans is the enigma of their so-called disappearance.

Although the Mayans did not really disappear, this denomination refers to the drastic population reduction in their main cities, decrease and ceasing of the construction of large buildings and stelas, and abandonment of powerful cities in their time. This event is known as the Classic Mayan Collapse, and it took place during the period denominated as Terminal Classic by Mayan archaeologists, approximately between the years 750 and 1050. However, these limits vary according to different authors and approaches. This event happened gradually and unevenly, both temporally and spatially, in the territory occupied by the Mayans. For this reason, some history experts and archaeologists avoid using the term collapse and refer to this event as the decline or abandonment of the Classic Mayans.

The pre-Columbian Mayans inhabited a wide territory within the Mesoamerican region, mainly from the Yucatan Peninsula to El Salvador. This area is extremely heterogeneous and exhibits large differences in terms of orography, soil type, vegetation, and climate, especially rainfall. Although approximately 70% of the rainfall typically occurs during a 5-month period between June and September, there is a south–north gradient in terms of the total amount. Rainfall is heavy in the southern areas in the Central American mountains called the Mayan highlands and decreases as one moves northward from the Yucatan Peninsula, a region known as the northern Mayan lowlands.

Being a sedentary agricultural civilization, which settled in a region with very few large rivers, most of the Mayans depended mainly on the presence of springs and rain for agriculture and on their water storage capabilities for domestic use. This can be seen in the development of structures such as the cisterns or chultuns of the Puuc area, Palenque aqueduct, and different-sized reservoirs in Tikal, Calakmul, and Caracol. All are clear examples of the systems used by the Mayans to adapt to their natural environment. However, they were still susceptible to rainfall changes. For this reason, one of their main gods in their pantheon was Chaac, a one and manifold god, lord of the rain and of the four cardinal points, represented in various forms and with different costumes, especially with a torch during droughts.

Many hypotheses about the factors prompt the Mayan decline: armed conflicts of different kinds such as social uprisings, internal wars for dynasty succession, army invasions from rival cities, plagues, environmental degradation, and weather variations. The last two options have been gaining strength in recent years as reflected in the increased number of general publications about the events, especially in those that associate them to weather events. In addition to the renowned 2012 prediction, the renewed interest in Mayan civilization is surely owing to an increased awareness of our relationship as a civilization with nature and the role we are playing in the anthropogenic climate change.

Another factor that has reinforced the idea of climatic events as triggers of the Mayan decline, specifically droughts, are the diverse paleoclimatological reconstructions that have taken place in the zone inhabited by the Mayan and other surrounding regions. These reconstructions consist in estimating past rainfall amounts and temperature values from various sources such as the study of variations in the chemical composition of lake, channel or fluvial deposition sediments at river mouths. In addition, these estimates can also be made using stalactites, studying the pollen of the different soil layers or by the well-known method of analyzing growth rings in trees.

From the abovementioned studies, it has been possible to determine that the Late Classic period featured more precipitations, which also coincides with the boom of the Mayan civilization. In this period, the population increased, influence areas from large rival city states like Tikal and Calakmul expanded, and construction of the great monuments that represent the maximum splendor of these important metropolis exploded. There is also evidence of several drought and arid periods during the Terminal Classic and Early Post Classic, matching the period when the population declined and large cities were abandoned. In some reconstructions, a more precise temporal analysis can be done, so it allowed to establish a dry period approximately between the years 760 and 910 CE when recurrent 3-to-9-year droughts took place over a period of 50 years. This period is consistent with the decline of the Mayan civilization,