AT HOMEONTHE GREATERWESTSIDE

Two Inherent homes on the 600 block of North Ridgeway Avenue are available for first-time buyers under the city’s Building Better Neighborhood and Affordable Homes program.

Two Inherent homes on the 600 block of North Ridgeway Avenue are available for first-time buyers under the city’s Building Better Neighborhood and Affordable Homes program.

The Better Neighborhoods and Affordable Homes program offers qualified buyers up to $100K in down payment assistance

By DELANEY NELSON and FRANCIA GARCIA HERNANDEZ Contributing Reporters

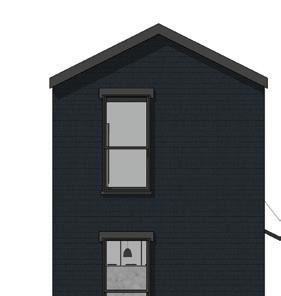

Two brand-new modern single-family homes sit across the street from a West Humboldt Park elementary school and health center at the intersection of North Ridgeway Avenue and West Huron Street. They boast new windows, a beautiful facade, new fences and landscaping, a sign of the high-quality modern finishes and amenities found inside.

See VACANT LOTS on page B2

and economic

Continued from page B1

The homes have sustainable and smart home features, boasting energy-efficient construction, all-electric connections and high-end Google smart home devices such as thermostats, security cameras, WiFi routers, keyless locks and speakers. They are even ready to install an electric vehicle charging station if their future homeowner chooses to.

These West Side homes stand as a beacon of opportunity – proof of what can be built on thousands of vacant lots citywide.

“We are not just building homes, we’re really focused on making sure that we’re building home ownership,” said Sonia Del Real, vice president of sales and economic development for Inherent LC3, the West Side company that manufactured and installed these modular homes.

About a mile from the homes, a crew of local construction workers assembles the homes that will soon be installed on the West Side and other

neighborhoods in the city. Rather than building on-site, Inherent LC3 assembles the modules of the home at their West Side warehouse, a process that takes 10 to 12 weeks. Once the two modules are finished – one for each story –they are transported to the parcel where they are set and finished.

“A neighbor could leave for work at eight o’clock in the morning, they come back and there’s a whole house,” Del Real said.

In total, a new home could be ready in 15 weeks. Unlike traditional construction, construction crews are not restrained by weather, allowing for efficiencies and faster construction times, Del Real said.

Inherent LC3 will bring 24 properties to the neighborhood, turning vacant lots into affordable homes. The lots were owned by the city and transferred under a land redevelopment agreement that requires new construction on these lots to remain affordable.

The company has also built homes for lots owned by the Cook County Land Bank and created a micro-home prototype last year that was proposed as a solution to temporarily house migrants.

Two West Humboldt Park homes have been sold and two are currently on the market, Del Real said. More houses are underway and will be installed on North Lawndale Avenue in the proj-

Apowerful group of real estate agents agreed to settle a lawsuit that alleged the group’s commission rules forced homeowners to pay higher fees when they sold their houses.

A federal judge granted preliminary approval to the settlement terms in March, and as part of it, the group, National Association of Realtors®, is expected to pay $418 million in damages.

Key changes to the process of buying or selling a home will be made, as well, to account for more transparency and encourage market competition.

Before the settlement, broker commissions were typically paid by sellers. The seller’s agent usually agreed to split the commission with the buyer’s agent. These commissions typically range from 5% to 6% of the total cost of the home — an industry-wide standard that is much higher than in other countries.

But buyers are not always made aware of the full cost of purchasing a home, particularly when it comes to the broker’s commission. The same goes for sellers. Homeowners sued the NAR, alleging the organization fixed broker commissions at high rates and discouraged clients from seeking better terms, which cost them more money

The lawsuit also argued that the trade group

violated antitrust laws by mandating that the seller’s agent make an offer of payment to the buyer’s agent. As it stands, the settlement will end the practice of sharing commission rates on the Multiple Listing Service (which is only accessible to agents) and theoretically make the process of negotiating compensation more transparent.

Beginning in late July 2024, agents will require prospective homebuyers to sign an agreement that discloses their broker’s commission — how much the buyer will compensate their agent if they go through with the purchase — and who will pay it. A contract must be signed before a Realtor® can represent a client and show them properties.

Agreeing on the terms before viewing properties provides clarity for buyers on what services they can expect from their agent, experts say. It also guarantees buyer’s agents will get paid for their work.

For some, the process won’t change much. Commissions were technically always negotiable, even before the proposed settlement. Many Realtors® already used buyer-agent agreements, although they were not previously required in Illinois.

There is now no option for agents to show a

ect’s first phase, with more homes coming to West Huron Street and West Ohio Street in the future.

Once completed, the homes will be available to first-time homebuyers who qualify for financial assistance from the city’s Better Neighborhoods and Affordable Houses program.

This city program aims to promote affordable housing by pro-

house to a buyer without written agreement, said Michelle Flores, a Chicago-area Realtor® who represents both buyers and sellers.

The agreement will state how much the buyer is willing to pay the agent to represent them, with the understanding that when they want to view house, the agent will first to negotiate for the agreedupon compensation on the listing side, Flores said.

“But in the event that don’t receive compensation from the listing side, the buyer is responsible to pay the buyer’s agent,” she said.

On the seller’s side, the settlement bans advertising a commission for the buyer’s agent on the MLS, the online listing platform that only real estate agents have access to.

“Instead of me offering compensation on the MLS to the buyer’s agent, the buyer’s agent has to come to me and say, ‘Hey, Michelle, I see a listing. I have a potential buyer, I would like to show that listing to the potential buyer. Are you offering compensation?’” Flores said.

She would respond with the compensation for that particular unit, she said. Then, the buyer’s

viding up to $100,000 in a forgivable grant for downpayment assistance, closing costs and appraisal gaps to eligible first-time homebuyers. The grant amount varies based on buyers’ income and neighborhood residency

Homebuyers complete the traditional homebuying process and an additional process to obtain the BNAH grant. The program requires buyers to live on-site for 10 years after purchasing. It is available for single-family homes and multifamily buildings with up to four units. Yet, all properties must have been developed on citys

agent will say, “Great, that works for us!” Or say no, because the compensation is outside the amount they agreed upon with their buyer client.

The main widespread effect of the settlement will likely be lower commission fees for sellers, as agents try to compete for business.

Flores said one potential downside of the settlement is that it could put lower-income buyers or those who don’t have a lot of cash at a disadvantage.

“If sellers are adamant about not paying a buyer agent commission, then who’s going to pay the buyer agent?” she said. “Buyers who don’t have the funds will fall in that category of not being able to buy — we already know which demographic is going to suffer.”

Flores also said this might make the home-buying process take longer or seem more daunting to prospective homeowners.

Realtors® say the details of how the settlement will play out haven’t been determined. And although a federal judge granted preliminary approval to the settlement in March, the final approval hearing won’t be until late November of this year. It is widely expected to be approved.

In addition to the city’s homebuying assistance program, Inherent LC3 provides homeownership assistance services for five years, including quarterly maintenance and energy efficiency checks.

“We feel that the first five years or we know that the first five years are critical in homeownership or for home or sustainable homeownership, “ Del Real said.

Through a partnership with Northwestern Mutual, the company offers death and disability insurance subject to underwriting at no additional cost. For the first five years, buyers also obtain free services from security company ADT

Homebuyers can select between a two-bathroom, three-bedroom home without a basement and a one-bathroom, two-bedroom home with a basement developed by Inherent LC3. The homes have a kitchen, on-site laundry, a living space and an enclosed backyard.

When possible, buyers can select from several facade design options and customize some of the kitchen, bathroom and flooring finishes. The hallways are wide enough for wheelchair access, increasing accessibility for aging families.

“We don’t want to call these starter homes. We want people to stay in them for a long time and pass them on, that’s how you build generational wealth,” Del Real said.

Amid rising costs and gentrification, some organizations have found a creative way to obtain homeownership and to combat the displacement of longtime residents: community land trusts.

The goal of this shared ownership model is to provide affordable home prices, and in the process, keep people in their own neighborhoods.

A land trust, typically a nonprofit organization, buys the land on which a house sits, then sells the house at a discounted price to a community member while retaining ownership of the land underneath the home. In exchange, the buyer will sell the home at a discounted, affordable price if they decide to leave.

“It’s essentially a vehicle to increase community control over what happens in the real estate market, and also to preserve the affordability of housing in a rapidly gentrifying market context,” said Geoff Smith, executive director of the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University.

Black southern farmers are credited with starting the first community land trust, or CLT, in the United States during the Civil Rights Movement. Now, there are about 230 community land trusts throughout the country.

Research from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy showed that land trust properties had substantially lower foreclosure rates in the aftermath of the 2008 housing crisis than conventional properties. This allowed community members to ride out price increases in their neighborhoods.

Lower-earning homeowners were disproportionately hit by subprime lending and the high unemployment rates that followed the housing crisis. Because CLTs kept homeowners from obtaining subprime loans in the first place, they were buffered from the impact of the economic recession, according to Lincoln Institute researchers.

Julio Pensamiento, Here to Stay Community Land Trust board member, said land trusts are an opportunity to give homes back to the community, rather than having them fall into the hands of predatory developers.

“It’s essentially to provide somebody a second chance, instead of the alternative, which would be to sell your home, foreclose, whatever

it may be, and then move elsewhere,” he said. “We want to be able to keep those legacy families here operating in our neighborhoods.”

Here to Stay is one of three CLTs operating in the Chicagoland area. The nonprofit, which serves low- to moderate-income households across Hermosa, Avondale, Logan Square and Humboldt Park, has acquired seven homes since incorporating in 2019. It has sold three homes, with two more sales expected within the next month, said program director Kristin Horne.

The Northwest Side land trust was born in response to community members’ need for affordable housing. It can curb displacement, allowing residents with varying income levels to live in neighborhoods such as Logan Square and Hermosa.

“(People) were afraid of being displaced, pushed out of the community entirely. They wanted homeownership so that they were able to have permanent roots in the community,” Horne said. “We know we can’t stop gentrifica-

tion outright — but we can at least slow it down.”

The goal is long-term affordability, made possible through a 99-year ground lease. During that period, the organization retains the rights to the land and controls its use. Major renovations that would change the home’s value must be approved by the trust. That keeps properties from being flipped for profit, Pensamiento said. Here to Stay also requires the homeowner to live on the property

Wealth accumulation — a main benefit of homeownership — looks different in a community land trust. Depending on the agreed-upon terms and resale formula, a homeowner will collect a share of the home value appreciation rather than its entirety. They will also earn home equity, although at a limited rate compared to the amount generated by conventional property value appreciation.

CLTs have the potential to promote sustainable homeownership and community stability by lowering housing costs and providing housing support. But the model may not fit all neighborhoods, said Smith, who is also a member of the Illinois Community Land Trust Task Force.

In a neighborhood like Logan Square, which

has become highly inaccessible to people with modest incomes, the community land trust creates an opportunity for affordable homeownership — and an amount of wealth accumulation.

Questions remain about whether the CLT model provides the same benefits in neighborhoods like Austin that are relatively more affordable and have more available housing for sale.

“It’s not a one-shoe-fits-all. We’re not saying there should be a million land trusts and this is the only way to promote affordability,” Pensamiento said.

Aside from promoting affordability, community land trusts can be a vehicle for long-term residents to stay in the neighborhoods they have called home, preserving some of the neighborhood’s identity and culture, Pensamiento said.

“Being able to push folks out right and uproot families and uproot cultures is something that we want to put a stop to.”

Follow us each month in print and at https://www.austinweeklynews.com/ at-home/, where you’ll find additional resources and useful information.