Painter

SALOMON GRIMBERG

SALOMON GRIMBERG

Published by Rowland Weinstein and Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco on the occasion of the exhibition

Jacqueline Lamba—Painter

March 11–April 22, 2023

Weinstein Gallery 444 Clementina Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

©2023 Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco

Essay, From Darkness with Light ©2001 Salomon Grimberg

This article was first published in Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 22, no. 1 (Spring-Summer, 2001), 5–13

Publication directed and edited by Kendy Genovese

Photography of artwork by Michael Synder

Designed by Linda Corwin, Avantgraphics

Text set in Chaparral Pro/Baskerville

Weinstein Gallery would like to extend our profound gratitude to Aube Elléouët-Breton, Marcel and David Fleiss, and Salomon Grimberg, without whom this catalogue and exhibition would not be possible.

Front and Back Covers: Behind the Sun (detail), 1943

Inside front cover: In Spite of Everything, Spring (detail), 1942

JACQUELINE LAMBA

JACQUELINE LAMBA

From Darkness with Light

By Salomon GrimbergABOUT HER PAINTING, IN SPITE OF EVERYTHING, SPRING (1942, inside front cover), Jacqueline Lamba (1910–93) wrote: “The object is only a part of space created by light. Color is its non-arbitrary choice in transfiguration. Texture is the crystallization of this choice. The line does not exist, it is already form. Shadow does not exist, it is already light.”1

Light makes things visible; but too much light can blind. Jacqueline Lamba died with the belief that “she would not be recognized as an artist because she was a woman, had been married to André Breton (1896–1966), had stopped painting Surrealism, and had a difficult personality.”2 Why such a bleak view from someone who had lived obsessed with light?

Born in Saint Mandé, Seine, a suburb of Paris, Jacqueline Mathilde Lamba was the younger of two girls from the marriage of Jane Pinon and José Lamba.3 Jacqueline’s birth was a disappointment to her parents. She personalized it and built her future sense of self seething inside that her parents wanted a boy and not a girl, and called her “Jacko” and not Jacqueline.4 When she said, “Men win because they are men,”5 she inferred that she was doomed to live the life of a loser. Jacqueline grew up wanting to be a boy. The family referred to her as a “garçon manqué,” the French term for tomboy, which literally means “incomplete boy.” Into late adolescence she wore pants, cropped her hair, and referred to herself socially as “Jacko.”6

Jacqueline’s mother had been dissuaded from entering medical school by her family and encouraged instead to follow the more traditional role of marriage and homemaking; however, she remained a serious reader.7 Jacqueline admired her intellect: “My mother was anti-Catholic, she had rather broad ideas. She saw a book by Cocteau in my pocket; she said to me, ‘well, you are reading horrible things.’ She had an excellent library, and she read. She knew who he was.”8 José Lamba was an agricultural engineer and author of several articles on Mediterranean roses, diseases of banana trees, artificial cotton, and related subjects.9 He had been honored by the French government and in 1910 was working in Egypt redesigning Cairo’s city gardens, among other projects. The Lambas returned to France for Jacqueline’s birth and went back to Egypt, leaving their newborn in France, in the in the care of a nursemaid for her first 18 months, and with Jane’s parents the following year.10

Huguette Lamba, Jacqueline’s older sister by three years, lived with her parents

in Egypt and remembered the summers when the family returned to France. She recalled that Jacqueline, like their father, liked the light and heat. “Our father took us to Cannes, he himself liking the light and heat. She had our father’s love for drawing, and drawing well, and the love for plants; she always liked flowers a lot.’’11 On Friday, February 27, 1914, driving his automobile in Heliopolis, Egypt, José Lamba was in a fatal accident. Jacqueline was three and a half years old. Huguette recalled: “My sister used to say that the only thing she recalled about my father was that one day when she was enraged, my father took her in his arms, walked to a balcony where there were many flowers, picked one and gave it to her, which calmed her anger.’’12 This early memory became the cornerstone on which Jacqueline Lamba structured her life. She nurtured the illusion that, had her father lived, her life would have been quite different. A friend recalled how, “right before her death, Lamba spoke about his death as the great tragedy of her life because he really had loved her.”13 Despite having

lived an extraordinary life, Lamba’s belief that it had been tragic suggests that, despite appearances, she had lived in pain.

Just before the start of World War I, the widowed Jane Lamba, her younger sister Lucy, the girls, and their governess Henriette, sailed back to France. They settled in Saint Mandé, at their maternal grandparents home on the Rue Cart, remaining there until 1918, when they took an apartment in Paris on the Avenue Suffren, near the formal garden the Champ de Mars. Grandmother Jeanne was religious but respectful of the rest of the household members, who were nonbelievers. Her grandfather, a former administrator of the Paris Hôpital de La Pitié, wrote “soap opera” romances for newspapers and magazines. He taught the girls word games and took them on promenades to the Bois de Vincennes near their home. During the last year of the war, the girls, ages seven and ten, were sent to a nonreligious boarding school. Lamba liked it there and told a friend amusedly, some 25 years later, that whenever families came to inspect the place, she was presented as the typical child.14 With her golden curls, large hazel eyes, and rosy cheeks, she was showing signs of the great beauty that would bring her fame but also prove problematic. In fact, in her seventies she confided to Martica Sawin: “If I had been less beautiful, I would have been a better painter.”15 More likely, she was not taken more seriously because she was a beautiful woman, although Lamba herself was preoccupied with her image. As her daughter Aube Breton Elléeouët explained, she was “a narcissist, used to being admired for her beauty.” Aube’s earliest recollection of her mother is of her sitting at her vanity table looking into the mirror: “I have the feeling of her presence, but I don’t have the feeling of a motherly presence . . . . She was much more preoccupied with herself than with the child that I was. I have a lot of memories of my father, since he was more often with me than Jacqueline.”16

Lamba’s art education began with frequent visits to the Louvre with her sister and mother, reinforced by her friendship, from about age twelve, with Marianne Clouzot. Marianne and her sister Marie-Rose were about the same age as Jacqueline and Huguette, and their mothers had been friends before their respective

marriages and the Lambas’ move to Egypt. Their father, Henri Clouzot, was a curator, first at the Fornay Library and later, in 1920, at the Palais Galliera, currently the Costume Museum. At their home Lamba saw, for the first time, African and Oceanic art, which Clouzot collected, exhibited, and wrote about. And at the Palais Galliera she saw exhibitions of decorative arts, printed fabrics, and painted paper that proved decisive in her formation as a visual artist. From October 1926 through June 1929, Lamba attended the Ecole de L’Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs on the Rue Beethoven, graduating “with full satisfaction due to the quality of her work.”17 She created designs for books, homes, and advertising, including fabric and paper for large retail stores such as the Bon Marchéand Trois Quartiers. However, attracted by Symbolist art, particularly the work of Maurice Denis, Lamba decided to become a painter. Although her mother advised against a profession that would bring little economic security, Jacqueline began visiting artists’ studios, such as André Lhote’s, then recog-

nized for his teaching as well as for his art. She identified with their individuality and started creating small canvases. Two pastel drawings from 1927, done when she was just 17, show her precocious skills. Her Self-Portrait (opposite) makes an imposing presence as it nearly fills the page. Drawn sensuously in rich earth tones, it brings to life a youthful Lamba, auburn hair cut short, her large hazel eyes looking directly at the viewer. A drawing of the androgynous L’Ange Heurtebise (Pg. 31), from Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus, reveals how at that early age she was already attuned to the intuitive world, her relationship to mirrors, and her gender dysphoria. Grateful to Marianne Clouzot for introducing her to Cocteau’s text, Lamba gave her the drawing along with the Cocteau book illustrated with a nonobjective “portrait” of Heurtebise by Man Ray.

In that same year, 1927, Jane Lamba succumbed to tuberculosis—she was 47. It was a difficult period for Jacqueline. She was completing her second year of decorative arts school as well as caring for her mother and Huguette, who was paralyzed by depression. The loss of her father had crystallized Jacqueline’s no-nonsense perspective on the inevitability of life. Now, her mother’s premature death added another layer of toughness, causing her to be cautious about attachments. After Huguette moved in with relatives whom Jacqueline found stiflingly conservative, she decided to live on her own.

Supporting herself on the meager earnings from her design work, Lamba moved into a series of boarding houses. Initially, she took an inexpensive room at a “home for young women” run by nuns, on the Rue de I’Abbaye, recommended by her friend Théodora Markovitch (Dora Maar), whom she had met the previous year through Marianne Clouzot. Maar was a Surrealist photographer and painter, and later Picasso’s lover and the model for his “crying women.”18

It is likely that Maar influenced Lamba, who began to experiment with photography at this time. Several of her images appealed to the publisher José Corti, who reproduced them in the magazine Du Cinéma in 1928. Lamba’s interest in light becomes apparent in these abstract photographs of Paris bridges and the Eiffel Tower. Focusing on details of steelworks that turn, twist, and open to the sky, they emphasize movement

and the interplay between dark and light. Robert Delaunay’s then popular paintings of the Eiffel Tower and Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical compositions are her obvious influences in these photographs. A metaphysical still life has a Roman bust of a youth, his blind gaze turned toward bands of light that slide through half open shutters. In Swimmer (c. 1928), a scene taken from life, she leaves the viewer unclear whether the figure floating on shimmering rough

water is a person or a mannequin, male or female.

Other images from 1928 include Dreamer, in which a cane lies as if it were a person on a metal bed, its arched neck twisted forward, away from the pillow on which it rests; Fountain, a simple close-up of a fountain sculpture that suggests a sea monster rising from the water; and Lit Room, where a patch of light slips through an open window leaving its illuminated imprint in an otherwise darkroom.

In 1934, while she was living at the Hôtel Medical on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Jacques, another boarding house, her life took a dramatic turn. She recalled:

I had a cousin (André Delons, an ex-Grand-Jeu member) who was older than me, about three years. So one day [in 1932] he says to me, “you should read Breton.” I had heard about him, but [could not buy] expensive books . . . .Therefore, he lent me some, and I was just astonished . . . . It was not Surrealism that interested me. It was what Breton was saying, because he was saying things that affected me, exactly what I was thinking, and I had no doubt that we were going to meet one way or another.19

She also said that Breton’s writings offered a definitive response to certain problems that are exceptionally difficult to resolve individually: problems regarding the relation between the poetic and artistic sensibility and a revolutionary consciousness, militant or otherwise, applied to all levels of existence. The thoroughgoing, exalting, unique spirit of Breton and his friends, their whole approach to life and the world, and the tone of certainty and supreme defiance that accompanied it: all this fulfilled me, liberated me, and instilled in me a joy such as I suspect young people today can scarcely grasp. 20

While teaching French in England and Greece, in 1932 and 1933, Lamba read Breton’s The Communicating Vessels, wherein he proposed a poetic realm to link and equalize opposites, like dreaming and wakefulness. When she returned to Paris, she was determined to arrange a meeting. Maar, who by then was involved with Picasso, offered to make the introductions, but Lamba declined, wanting to orchestrate the meeting herself.

Lamba planned her “accidental” encounter with Breton for 7:30 on the evening of May 29, 1934, at the Café de la Place Blanche. She was 24 years old,

he was 39. Breton had studied to become a physician and worked with shell-shock victims during World War I. Through his patients he became aware of the manifestations of the unconscious and became obsessed by the idea of accessing their internal reality and transforming it into art. Breton’s magnetism and feel for the creative process was behind his discovery. Moreover, as Freud, whom he revered, had conceived psychoanalytic theory to understand psychic processes, Breton conceived Surrealism to give them literary and visual credence. An only child, Breton rarely mentioned his past. When his daughter Aube asked him why, he asked her to “imagine every possible humiliation”—he had experienced them all.21 This may partially explain Breton’s paradoxical nature, his fluctuations between being autocratic and demanding unconditional devotion and being sweet, even childlike and tender.

In retrospect, Lamba explained: “He saw in me what he wanted to see, but he didn’t really see me.”22 She, too, saw in him only what she wanted. Although they longed for a life of poetry, their intransigent personalities doomed their relationship from the start. Nevertheless, for at least nine years, the influence of each over the other nurtured their creative work. When they met, Lamba was making art and surviving financially by swimming nude in a glass pool at the Coliséum, a Montmartre dance hall on the Rue Rochechouart. Just over five feet tall, she was described by a friend as having an extraordinary body: “Since she loved the sun, golden all over and very well groomed. She swam like a fish, naturally; she looked better naked than dressed.” She exercised, worked out on a trapeze, and took care with her diet.23 Simone de Beauvoir recalled seeing her at the Cafe Flore, with “shell pendants in her ears, eyelashes painted with mascara, bracelets clashing as she waved her hands to show off those long, alluring fingernails.”24 Jacqueline Lamba had an extraordinary presence, was well read, and expressed herself with educated opinions. She also had a temper that earned her the nickname “Bastille Day.”25

Breton immortalized Lamba and the night of their meeting in his book L’Amour fou (1937), writing, “This woman was scandalously beautiful. From the first moments, a quite vague intuition had en-

couraged me to imagine that the fate of that young woman could someday, no matter how tentatively, be entwined with mine.”26 And so it was. First she appeared in his dreams, then in his writings, and after he evicted his then lover, Marcelle Ferry, Lamba moved into his small living space on the Rue Fontaine. When Lamba suggested they marry, Breton agreed, and they did, on August 14, 1934, less than three months after meeting. She wore black and refused to invite any family.27 The poet Paul Eluard and the sculptor Alberto Giacometti were witnesses at the wedding. Man Ray took the wedding pictures, photographing the bride nude with Eluard and Giacometti,

André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba at the International Surrealism Exhibition , 1936

André Breton and Jacqueline Lamba at the International Surrealism Exhibition , 1936

recreating Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Breton had been adamant about not having children, but meeting Lamba changed his mind. When she discovered she was pregnant, he eagerly awaited the birth of their daughter, Aube, which took place on December 20, 1935. The idea for her first name, meaning Dawn, came from a miniature drawing of daybreak by Victor Hugo in Breton’s collection. The romance in their relationship began to wither even before Aube’s birth, however, when Lamba realized that a too-high gas bill could overwhelm a longed-for poetic life.28 Breton blamed Lamba’s carelessness, and she grew tired of his extreme frugality. She began to experience her multiple roles of muse, wife, housekeeper, and now mother as an imposition. Breton earned little and collected compulsively. Lamba recalled, with acrimony, “years spent with no money, surrounded by a priceless collection.”29

The worst insult may have been Breton’s minimizing her need to paint, which at the time of their meeting was paramount. As with other women artists associated with the Surrealists, Lamba discovered that it was her role as muse that mattered most. Eileen Agar, a British Surrealist, remembered:

Among the European Surrealists double-standards seem to have proliferated, and the women came off worst. Breton’s wife, Jacqueline, was expected to behave as the great man’s muse, not to have an active creative existence of her own. In fact, she was a painter of considerable ability, but Breton never mentioned her work.30

Although Lamba was immediately included in Surrealist activities, collaborating in making exquisite corpses and decalcomanias,31 and exhibiting her paintings with the group, her contributions were rarely acknowledged. For example, in 1935, the year following her marriage. Lamba showed two paintings in the May “International Surrealist Exhibition” held in the Ateneo de Santa Cruz de Tenerife, but neither her name nor the titles of her works were listed.32 In later years, when her work was referred to in the Surrealist literature, it was said to have caused the breakup of her marriage. This chronic neglect enraged her and confirmed her belief that “men win because they are men.” Never theless, despite fulfilling her many obligations as Breton’s wife, Lamba continued to make art. In May 1936, for the “Exhibition of Surre-

alist Objets” at the Charles Ratton Gallery in Paris, Lamba exhibited four objects: Pour la poche; La liberté; Aux lévres de vermouth; and La femme blonde (shown above), as Jacqueline B (Breton-Lamba), as well as two collaborative works signed André and Jacqueline Breton. One of these, Le petit mimétique (1936) (above), could be an ironic reference that dovetails the unconscious alliance underlying their relation-

ship. It is a box containing a dried praying mantis, spread and pinned through the thorax onto a stack of leaves. In captivity, these carnivorous predators eat their young, and the female devours the male after copulating should he not escape.33

Lamba and Breton traveled to London for the “International Surrealist Exhibition” in June and July of 1936, where, as Jacqueline B., she exhibited two untitled objects and Les Heures (1935) (opposite), painted while she was pregnant. On an oval shaped canvas, the profile of a woman-shell lies dormant on its back, alone in the bottom of a dark ocean. Lamba’s anthropomorphism of a commonly known “queen conch” shell suggests a symbolic self-portrait shaped by her emotional state during the pregnancy. If Breton was “king” of Surrealism, she was its “queen.” With its thick, bright pink flaring lip, Lamba transformed the shell into a vulva, referring not only to her pregnancy and self-absorption but also to her isolation and role as a sexual object. For the delicately painted work, she reshaped the queen conch’s protruding nodules in its body whorl into a spiral crown, and then added a vacantly staring eye and a slender leg and tiny foot wearing a highheeled shoe.

A comparison of Les Heures with Portrait of André Breton as Saint-Just (1937) (opposite), is instructive. While she portrays herself as a beautiful sexual object, she links him to the French revolutionary, Louis Antoine Léon de Saint-Just (1767–94), a Robespierre associate who helped overthrow the Girondists and bring on the Reign of Terror. Lamba’s ambivalence comes through, however, in choosing SaintJust, who, despite his brilliance and heroism, lost his power. He was guillotined, becoming an “hommemanqué,” an incomplete man. Breton is dressed in a period black suit, white ruffled shirt, and a white ribbon tied in a bow at the neck, looking wraithlike, with his flat gray skin and pink lips. He holds in his right hand a quartz crystal and gazes furtively, not at the viewer but at something within the painterly space. On his shoulder a black butterfly—”the soul and the unconscious attraction towards the light”34—nearly blends into the sky, and in the distance, the illuminated Tour St.-Jacques stands out against the night. The strangeness of the painting, however, is in the placement of a nighttime event “inside” the room

while outside the window it is daylight. Painted the same year that L’Amour fou appeared in print, Portrait is Lamba’s visual response to her husband’s text. In L’Amour fou Breton eulogizes quartz crystal: “There

could be no higher artistic teaching than that of the crystal, [a] perfect example of [creation].” The Tour St.-Jacques, which Lamba pointed out to him on their first evening together as “the world’s greatest monument to the hidden,” Breton associated with the alchemist Nicholas Flamel and his wife Perrenelle, whom he believed had achieved transmutation, which “allowed [her] to contemplate the admirable works of nature.”35 The sculptural image of the physicist and philosopher Pascal under the tower, built to honor his experiments with the weight of air, is Breton’s reference to Lamba’s image submerged in water, recalled in his texts about her in L’Air de l’eau (1934) and L’Amour fou (1937).

Also in 1937, a set of 21 postcards, La Carte surréaliste, reproducing works by Surrealist artists was published. Four were by women: Lamba, Maar, Nusch Eluard, and Meret Oppenheim. Lamba’s The Bridge of Slumber (opposite), depicts, in sequence, a rose, initially wrapped in tissue paper, gradually shedding its protective coat until it is fully exposed. It begins to disappear, leaving its imprint on the ground. The significance of these few works by Lamba from the thirties cannot be overstated, for they reveal how she transformed poetry into Surrealism. Also, they are all that is known of her early creative efforts, as Breton destroyed all of her work after she divorced him.36

Lamba was torn by her competing roles as wife, mother, and artist. She loved Aube but resented that her care took so much time and energy; she loved and admired Breton but resented being subservient to him. As Breton’s spouse, she remained nameless, and was always referred to as “her,” or as “the woman who inspired,” or as “Breton’s wife.” Lamba had been given (and taken on) the identity of a trouvaille, a found object that inspired. On an impulse, she had left for Ajaccio on September 6, 1936, where she found work and stayed for more than a month, leaving Breton and eight-month-old Aube in Paris. It was not the first (or last) time she left, returning each time hoping to make the marriage work.

The Bretons’ financial situation did not improve in 1937, even after they were given an opportunity to earn salaries overseeing the Gradiva Gallery. Eluard predicted their failure: “His store isn’t coming along. Breton’s not cut out for this kind of business. Nei-

ther is Jacqueline.”37 Breton did not have the heart to sell the art, and Lamba was impractical; he continued to write, she to paint. For the Sur realism exhibit held that June at the Nippon Salon, Tokyo, Lamba exhibited Le cantonnier (1937), her last documented painting from that decade. She also showed at the “International Surrealist Exhibition” that took place on January 17, 1938, at the Galerie des BeauxArts in the Faubourg Saint-Honoré, which Simone de Beauvoir called “the most remarkable event that winter,”38 but again, neither her name nor her works appeared in the catalogue. That March, however, with the publication of Breton’s La Trajectoire du Rêve, a compilation of essays on dreams and a letter to him from Freud, Lamba’s Vielleuse illustrated Benjamin Péret’s edited text.

In April 1938 Lamba and Breton sailed for Mexico, a trip arranged by the poet Saint-John Perse, who

was at the time at the Quai d’Orsay (Foreign Office), and Doctor Henri Laugier from the Recherche Scientifique. She recalled:

We were in a particularly difficult material situation. These two persons were successful in being able to send André on a cultural mission to Mexico in order to give lectures on poetry and painting. We thought quite naturally that our accommodations were all taken care of; the opposite would have meant canceling this trip. Upon disembarking, we were met by a secretary from the

embassy, but . . . nothing else. As for money, we had just enough to last us eight days. With the return tickets in his pocket, André decided immediately to take the next boat. He was discussing this with the secretary when [Diego] Rivera introduced himself. He transmitted to us the invitation from Lev Davidovich [Trotsky] for the day after tomorrow and offered us hospitality in his house in Saint-Angeline [San Angel] during our complete sojourn of between three to four months. There on the threshold was the exceptional Frida Kahlo de Rivera, dressed in the fashion of the women of Tehuantepec region. And, as unexpected things were revealed, she told us that she was a surrealist painter. Her canvases surrounded, tragic and sparkling like her.39

The three couples, the Bretons, Riveras, and Trotskys, traveled around the countryside together. Breton and Trotsky co-authored For an Independent Revolutionary Art, which was signed by Breton and Rivera, as Trotsky did not wish to jeopardize his already precarious welcome. Thirty years later Lamba detailed the men’s conversations in a published interview about the Mexican trip. Lamba and Kahlo became close friends, and the following March, when Kahlo visited Paris to exhibit her work, she stayed in the Rue Fontaine apartment, sharing a bedroom with three-year-old Aube. When Kahlo at that time said to Lamba, “Men are kings. They direct the world,” Lamba could not have agreed more.40

In July 1939, after spending part of the summer with the other Surrealists at Chemilieu and part at Breton’s parents’ home, Lamba abruptly left for Antibes, once again leaving Aube with her father. When World War II broke out, Lamba was on the beach at the Midi with Maar and Picasso, who portrayed the two women in Night Fishing in Antibes (1939). Breton was drafted for the medical corps. In the meantime, the Surrealist exile had begun: Dalí was safe in New York, and Matta, Tanguy, and Kay Sage were on their way, as were Nicolas Calas and Kurt Seligmann. Wolfgang Paalen and Alice Rahon were in California, on their way to Mexico, and others were looking for places that would take them. Meanwhile, Lamba and Aube shifted about. They stayed for a time with Marie Cuttoli at Shady Rock, her home in Antibes, then with Maar and Picasso, who had taken them under their wing. Breton began visiting them after his transfer to

Poitiers. When they returned to the Rue Fontaine in February 1940, Picasso gave them a painting to sell, as their financial situation was desperate; however, by mid March Lamba and Aube were back in Royan, staying at the Hôtel du Tigre. On June 14, Hitler took France, and the government collapsed, splitting the countr y into two zones after the Germans entered Paris. The Nazis occupied the northern territory, and the Vichy government headed the unoccupied zone.

Following Breton’s discharge in early August, Lamba and Aube met him at the home of Doctor Pierre Mabille in Salon-de-Provence, near Marseille, the only seaport in the unoccupied zone.

At that moment Varian Fry, an American representing the Emergency Rescue Committee, also arrived in Marseille, his mission—to save as many artists, writers, and political dissenters as possible from the Nazis. The Bretons were lucky. Thanks to Victor

Serge, a Russian Trotskyist refugee who had spent two years imprisoned for speaking against Stalin and been loudly defended by Breton, who had challenged French Stalinists on his behalf, the Bretons were added to Fry’s list of those waiting for visas. They were housed at Villa Bel-Air, a farmhouse that Breton rebaptized Air-Bel, where Serge was already installed with his 17-year-old son Vlady. The charismatic Breton organized the group, which, at various times, included Victor Brauner, René Char, Oscar Dominguez, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Jacques Hérold, Wifredo Lam, André Masson, Benjamin Péret, Tristan Tzara, and Remedios Varo, into a commune of sorts. The young Vlady viewed these Surrealists with a mixture of suspicion and derision, finding odd their fascination with watching caged praying mantises devour each other, as if in a miniature, self-contained war that could not affect them. Watching Lamba exercising on her trapeze, he imagined her to be a circus performer. He recalled that she kept a low profile, spoke rarely, but was a striking presence, an elegant “grande dame.”41 It was here that Breton wrote Fata Morgana, a 500-line poem dedicated to Lamba, with illustrations by Lam that captured the Bretons’ underlying dynamics.

Lamba recalled Air-Bel with nostalgia, despite frugal meals, the lack of basic needs generated by the uncertainties of war, and conflicts with Breton. The interaction with the group is what she enjoyed:

“I was happy, in other words, selfish. Those were the Surrealists. What did you expect us to do? One had to hold on. One wasn’t at any rate to go sobbing into a synagogue. It would have been stupid to do that. We did what we had done before, we just continued.’’42 With the most primitive materials, they made art, wrote, and played inventive games, distracting themselves from the war raging around them. There were collaborative collages and drawings in which, on a single sheet of paper, each person made a contribution and the final product was read as one. Lamba’s hopeful attitude appears at least in one of them, in which she might have been conjuring the memory of José Lamba as she drew an Egyptian pyramid and a bird flying overhead. The best remembered game, later printed, was the Marseille card game, following the traditional playing deck format with four suits,

each with numbers ace to ten and then three picture cards. The four suits are Love, a flame; Dream, a black star; Revolution, a bloody wheel; and Knowledge, a lock. Replacing the court cards are the Genius (King), with Baudelaire, Hegel, Lautrémont, and the Marquis de Sade; the Mermaid (Queen), with Alice, Larniel, the Portuguese Nun, and Hélène Smith; and as the Magus (Jack), Freud, Novalis, Pancho Villa, and Paracelsus, all figures of interest to the Surrealists. Brauner, Breton, Dominguez, Ernst, Hérold, Lam, Lamba, and Masson drew the cards. Lamba explained, “I am Baudelaire,”43 which is why she drew him.

Jacqueline Lamba, André Breton, and five-yearold Aube embarked for New York via Martinique on March 25, 1941. Thanks to the patronage of Peggy Guggenheim, who sponsored the Bretons visa and stay in the United States, they arrived in New York, finally, in June. Kay Sage furnished a fifth-floor walkup apartment for them, at 265 West 11th Street, between West Fourth and Bleecker streets in Greenwich Village. Lamba described to Maar her spacious study, lit by a skylight, where she could paint.44 She thanked Fry for his generous help, writing: “What is for sure, is that America is the Christmas tree of the World.”45 Nevertheless, she missed France, and returning was never far from her mind.

Lamba first exhibited in New York in Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century Gallery inaugural show (October 1942), “Objects–Drawings–Photographs–

Paintings–Sculpture–Collages, 1910 to 1942,” showing three collaborative drawings done at Air-Bel with Breton, Lam, Dominguez, Brauner, and Hérold. She had her own work included in Guggenheim’s historic all-women exhibits, “31 Women” (1943) and “The Women” (1945). Ethel Baziotes recalled the Surrealists’ arrival in New York, “bringing the magic of Europe with them,” infiltrating the American mindset. Baziotes, who first met Lamba and Breton at one of Guggenheim’s parties, recalled a mesmerizing Lamba:

She was utterly enchanting, a most magical subject, a work of art herself; she did not have to do anything. She herself was out of a fairy tale; she took great interest in how she appeared in the world, her choice of clothing, make up, her whole state of being was highly rarefied. At parties, she’d wear 18th-century clothing bought at theatrical establishments, always long with narrow waists and full around the hips. Her presence was extraordinarily beautiful and she had a forceful personality.

As a couple, Lamba and Breton also made an indelible impression: “Together they looked wonderful, very unique people; something about them escaped definition—utterly fascinating. They seemed very well matched.”46

Their reality, however, was more prosaic. Lamba’s chronic discontent came to a boil in New York. A small monthly stipend from Guggenheim and Sage’s help with the apartment gave the Bretons financial stability for the first time. Too, their roles were suddenly reversed. She, fluent in English, a language he refused to learn, communicated for them both. Removed from his milieu, he was viewed simply as another Surrealist rather than as the head of the group, and he came across as a “caged animal.”47 Lamba began to paint full time. She wrote to Maar: “Now I am working in a completely serious way, to such an extent that I can’t possibly understand how I could have managed to avoid it before.”48 Although the new work was still surrealistic, it was nonobjective. While at Chemilieu during the summer before the war, Matta and Lamba had discussed painting “morphologies,” cosmic transformations arising out of destruction.49

In New York, Lamba began creating fractal landscapes, vaults with ribbed sides, metamorphic rocks, fragile and sharp honeycombed spikes, and hallucinatory gorges illuminated with crystalline inflores-

cence. They projected birth and regeneration through light, as opposed to the cosmic disasters focused on destruction and death prevalent in Matta’s New York paintings. Among the works she created during this period was Pour André Breton, dessin pour la vie (1942) (Pg. 18), a life-affirming work using sfumato, with the paper as a light source. It depicts a chromatic world of translucent hills, valleys, and archetypical haloed personages. Only four of these works have survived. “I did quite a few, I was still into Surrealism,” Lamba recalled. “One day Matta showed up, saw my work, and he said to me, ‘It’s just like what I’m doing.’ So I destroyed everything.”50 She regretted it later.

Meanwhile, Breton, with the help of Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp, was establishing the Surrealist review VVV. Seeking an official American editor with access to money, they settled on Kay Sage’s cousin David Hare (1917–92), a photographer who produced phantomlike imagery. The bilingual Lamba was called in to translate, and Hare, who spoke no French, “fell head-over-heels in love with her the first minute he saw her.”51

For the first issue of VVV (June 12, 1942) “Jacqueline Breton” contributed an untitled photo collage (Pg. 20) of a night scene with a couple looking into the horizon. The heavens integrate various skies, some starry, some cloudy. The woman’s body, from head to toe, is shaped out of a fisherman’s net, through which one can see the ocean. For the second issue (March 1943), now as Jacqueline Lamba, she contributed Non, Il ne fait qu’en chercher, me replique-je (No, he’s only looking for it, I told myself) (1942 (Pg. 20), the fractal landscape that was exhibited in “31 Women.” Painted as if through a frosty mist, a smooth fluted pillar between crystalline inflorescences rising from the floor holds up a cave opening. Opposite a delicate wall of fractured rock, dark cones rise from the ground on a horizonless landscape surrounded by pools of light. (These two works are known only from their reproduction in VVV.)

With Hare, now, she collaborated on Animal, Vegetable, Mineral Figures–Two Movements Each (1942), companion sculptures made of plaster, wire, rocks, and feathers. Hare began making sculpture after meeting Lamba. She recognized his talent in the playful way he made small, beautiful objects with plaster and discarded materials, including wire and string, and insisted he do sculpture seriously. He sought technical advice from their mutual friend, Alexander Calder, who by then was creating his “drawings” with wire.52

“If you leave me I will destroy you,” Breton warned Lamba when she asked for a divorce.53 She had seen his wrath and his ability to sever relationships with anyone who crossed him. Lamba sought Kahlo’s counsel in Mexico, where she and Aube were Kahlo’s guests for seven months during 1944. Kahlo portrayed Lamba’s predicament in the still life, The Bride that Becomes Frightened When She Sees Life Open

(1943). Lamba is the doll in the upper left corner, peeking at the scene before her, fruit, larger than she, cut open and arranged aggressively in a sexually suggestive manner. The doll represents Lamba as a Surrealist ornament. Now, in the face of reality, with a chance to separate and individuate, she is frozen in fear of the world beyond.

Lamba returned to New York determined to seek a divorce. Breton reminded her that she would get nothing from their Rue Fontaine home. Choosing freedom with uncertainty over the security of a gilded cage, she accepted his conditions.54 Before leaving for Mexico, Lamba created Behind the Sun (1943) (Pg. 32), a celebration of her relationship with Hare. Stained with flat, translucent earth tones, the richly painted canvas resembles a hanging fabric in which cutout gaps expose a blue sky. Drawing the viewer ’s eye toward the far right is a phallic form facing an opening. A new source of imagery is Indian fabrics and artifacts, which Hare, who had lived among the Hopi as a child, collected.

In April 1944, Lamba had her first one-woman show in New York City, at the Norlyst Gallery, exhibiting eleven oil paintings and six works on paper

created between 1942 and 1944. Although most of these works have since been lost or destroyed, among those still extant are In Spite of Everything, Spring (Pg. 34) and Behind the Sun (Pg. 32). A line from the invitation reads: “Any expression in art not stemming from Liberty and Love is false.” Surprised by the strength of the show, the Art Digest reviewer wrote: She thinks of space as something destroyed by light when light makes full forms and objects in it. One would expect this theory to be illustrated by just such cobwebby plasmas, sparkling jewels and abysmal blues as we do find in her paintings; but l was unprepared to see these things laid down on canvas in so direct, clean and unfussed a manner. We would say she has indeed taken light’s mea-

sure. She creates an intoxicating dream world at the Norlyst Galleries this month. Her husband is André Breton.55

The Surrealist dealer Julien Levy recalled being “under a cloud with Breton because of my close friendship with David Hare, the cause of André’s divorce from Jacqueline Lamba.”56 When they split, Lamba and Aube moved into Hare’s apartment at 42 Bleecker Street. They subsequently moved to his house in the Hamptons and then to Roxbury, Connecticut, with each move making it more difficult for Breton to visit his daughter. Hare continued to explore the sculptural medium, his work attracting the attention of Clement Greenberg, who wrote that he stood “second to no sculptor of his generation, unless it be David Smith.”57 Thanks to an inheritance, Hare and Lamba lived a comfortable life, free to make art. They even exhibited together, from August 13 to September 8, 1946, at the San Francisco Museum of Art: “Painting by Jacqueline Lamba and Sculpture by David Hare.”

By all accounts, the Lamba-Hare marriage was initially a happy one. Lamba went from being the ornamental wife expected to behave and keep personal opinions to herself, to being herself: blunt, outspoken, without measuring her words, sometimes to the point of unconscious cruelty. Ethel Baziotes found Lamba’s open contempt of the “bourgeoisie” fascinating, as well as her readiness “to tell others they were not original. She was full of likes and dislikes— very strong with her opinions, very forceful, especially about people. She was very instinctual,” she added, “and expressed it in just about practically every way. [Once] she and David Hare came for lunch in the 40s and she noticed how I loved my domesticity, and she said how much she hated it. She was a very beautiful animal.”58 Ernestine Lassaw recalled: “Jacqueline was not an easy person, and people did not like her a lot; she was very contentious, demanding, hard on others, expecting them to live up to her expectations.”59 Lamba’s demeanor gradually toughened, and so did her painting. Building on her training in fabric design, Lamba began creating images assembled as quilts or puzzles: fragments cut flat, smooth edges integrated with a soft color line forming boundaries between them. Toujours printemps (1947) (Pg. 45) is a near-abstract landscape painted in a diffuse palette of golden hues: below a gray sky, a house stands to one

side of an oval pond around which tall-stemmed flowers grow. The painting links the soft focus work created in New York during the war with the hard edged paintings that followed later that year. In Rivière Noir (1949) (Pg. 46), a jagged blue river travels from one corner of the canvas to the other between bodies of land formed by triangular shapes of ochre and brown and speckled with white. In Tournesol et deux cercles (1949) (Pg. 22), a single sunflower covers the canvas: its leaves, petals, and the sun above blending sharp edges and round forms. Picasso’s influence is most apparent in the handling of the strong black line used to outline flat forms, which then are filled in with color. Although Abstract Expressionism was the current American idiom, Ernestine Lassaw recalled that Lamba “did not care much about American artists. Picasso was the love of her life, she had very close ties with him [and] wanted to paint like him; she thought Picasso was the last word in art; she idolized him.”60

In the June of 1947, Lamba and Hare traveled to France to view their work in “Le Surréalisme en 1947” at the Galerie Maeght, the first Surrealist show since war’s end. By this time Lamba had lost interest in Surrealism and painted nothing new for the show, exhibiting only La promenade, les jeux (1945), from the fractal landscape series. Along with Arp, Brauner, Calder, Donati, Duchamp, Ernst, Hare, Matta, Sage, Dorothea Tanning, and Toyen, she created a lithograph for the portfolio published for the exhibition. She and Hare visited Dora Maar, who, having been supplanted by Francoise Gilot, was spending the summer alone in her country home in Ménerbes. Lamba had come also to see her one-woman show at the Galerie Pierre, her first such in Paris. A small but comprehensive retrospective, it brought together her paintings from 1942 to 1947, the years she had been away. Critics were uniformly complementary but could not help mentioning that she had been Breton’s wife and had inspired L’Amour fou.

While in France, the 37-year-old Lamba became pregnant. She described her experience:

I am fine but uncomfortable in my body. The child is taking all that I have in the way of energy and I am as if sleeping or trying to in order not to feel my body that I feel does not belong to me anymore. The spirit follows the rhythm. It’s nice weather, we are back in Roxbury, I

cannot paint and I don’t feel like drawing. A baby scale, special blankets and layette furniture have invaded the house.”61

Meredith Merlin Hare, her “golden boy,” was born in New York on June 19, 1948. Thereafter, Lamba created for herself an internal lifeline split: before Merlin and after Merlin. She inscribed in the back of her photographs the date when they were taken and Merlin’s age at the time, whether he was in them or not. An uncomfortable pregnancy did not keep Lamba from fulfilling her commitment to the Passedoit Gallery in New York. “The gallery where I had the show was not large enough for all the works I wanted to show, but it was not too bad. Next year there will be a much larger one.”62 She exhibited 15 paintings, from April 27 through May 1948, and wrote in her personal notes, “1948: no longer painting surrealism.”63

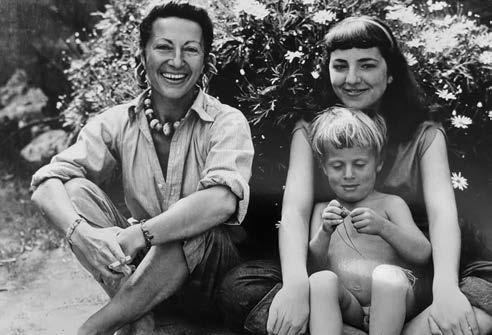

Jacqueline, Aube, and Merlin, Cannes, 1953

As the new decade began, Lamba’s painting began to shift, reflecting growing trouble with Hare. The Lassaws recalled “his many girl friends, experimenting with drugs,”64 and Ethel Baziotes witnessed the change—”drastically, her whole state of being was different. She was much graver.”65 Lamba’s paintings became quieter, more subdued, her brushstrokes looser, her palette warmer. One of several separations took place following a trip to New Mexico. It was unusual for Lamba to paint people, but in U.S.A. Taos (1950) she portrays two faceless persons in the distance, framed by vegetation, standing side by side before a brick building, their heads turned toward each other. The landscape Les papillons noirs (c. 1950)

(below) is an ambitious work and the largest canvas from the period. It is a study in contrasts: The upper half of the painting is a gray, monochromatic sky; black butterflies whirl, leaving behind swirling light shadows of their aimlessness. Below is a colorfully splattered field where wild grass and flowers grow tall, undisturbed. The painting is the spatial metaphor of Lamba’s discomfort. The event that triggered her realization that her relationship with Hare was over took place at a party. When he introduced her as “my wife,” the other person blurted out “which one?”66 She returned to France in 1954, first leasing a place at 93 Boulevard Gazagnaire, in Cannes. When Hare followed her there, she asked Picasso to offer him an assistantship. But Hare declined, claiming that he wanted to do his own work.

Her marriage over, the following year she and Merlin moved to Paris, to a studio at 46 Rue Gay-Lussac; Hare sent money to Lamba every month for the next

42 years.67 Reality forced Lamba to establish a new sense of self. She later explained to Stephen Robeson-Miller that she had painted Surrealism to please Breton and expressionist landscapes to please Hare, and that now (in 1977) she was painting for herself.68

With her usual merciless objectivity, Lamba reappraised her earlier work and destroyed much of it. She began again with the basics, drawing from a model, painting from the human figure, and producing generic landscapes and still lifes. The early stages of the process, although derivative of Matisse, produced work that was strong and immediate but not reflective of what she sought. Lamba had become a convert to psychoanalysis after reading Freud’s theories about the unconscious 25 year earlier. At that time, the Surrealists were satisfied using a loose form of free association to make art, but uninterested in using it as tool for internal transformation. Lamba reconsidered: conflict and frustration over unmet

needs could not only be reflected in painting but also speak to the creator about the root of the problem. If aware of her unconscious as it surfaced, it would allow her to work directly with her essence, transforming as she made art.

Sometime between 1955 and 1962, Jacqueline Lamba entered psychiatric treatment with Dr. Gaston Ferdière.69 It is likely that she had met Ferdière in 1935, when he and Breton participated in the International Congress for the Defense of Culture. A militant leftist and a strong supporter of popular education, Ferdière is remembered for treating Antonin Artaud—with whom Lamba had been friends—in 1943 after the poet entered the Rodez asylum, where Ferdière was director, and finding that the most effective therapy for him was making art.70 Details of Lamba’s treatment are unknown, but she told a friend that, as she turned 50, “her energy was different. There was little time, and she wanted to use it to paint. When you have children and a man in your life, you cannot paint.”71

In the summer of 1962, Lamba began creating her signature mature work: landscapes, springs, and mountains, pieced like puzzles, loosely integrated, ultimately fragmented. The experience that triggered them might have been a regressive pull during a temporary separation from Merlin who, for the first time, was spending the summer with his father in the United States. Lamba vacationed in Biot and SainteAgnès, where she created paintings like Biot (1963–1966) (Pg. 63), a small vertical canvas in which she projects her awe of nature. In her newest pattern or working, Lamba also made calligraphic drawings like the nonobjective L’Ivette a bu res (1964) (Pg. 66), in which fragments of black calligraphy shape the structure. The white paper is used as both light and medium to bind the writing. These works perhaps show the influence of Mark Tobey, who in the 1950s had been influential in the development of the French Tachism, which was of interest to Lamba. It is likely that she saw his 1960 show at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Like Tobey, Lamba believed that painting should come through meditation rather than action, which is the opposite of how she had worked under the influence of Picasso.

For 17 years, between 1963 and 1980, Lamba

spent summers at Simiane-la-Rotonde. This small medieval-era village grew out of a rocky hill and faced a squared plain covered with fields of lavender. Day after day, she quietly followed the same ritual. She woke early, painted past midday, took long walks, and in the evening prepared dinner. These summers provided reflective experiences that also sparked images created after she would return to Paris. Plaine de Simiane (1964) (Pg. 64), for example, is composed of overlapping patches of intense color—reds, greens, and yellows applied flatly to the surface with spots of black and white emphasizing light.

Lamba’s friendship with Picasso continued. When

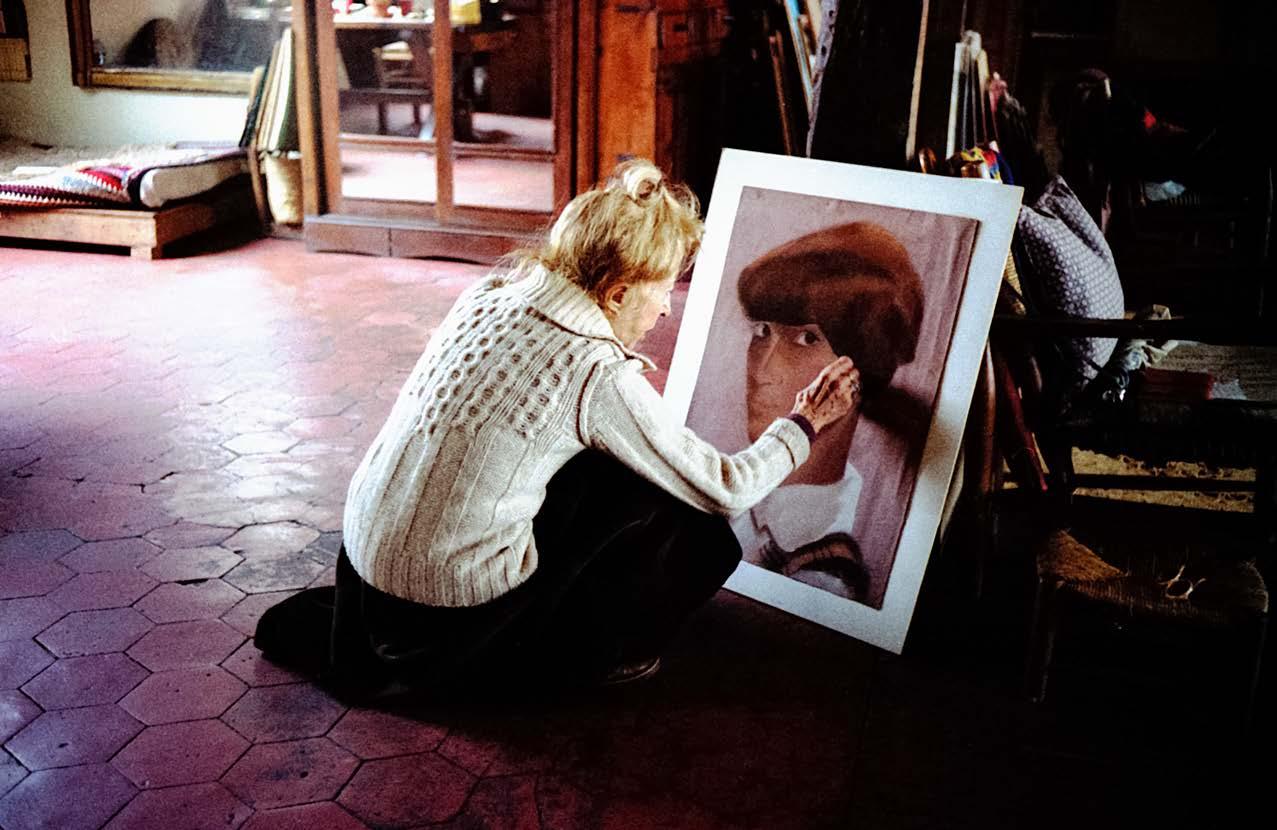

Jacqueline Lamba in Mexico, 1938

Jacqueline Lamba in Mexico, 1938

she showed him the work she had done between 1962 and 1967, he liked it, and thanks to him Lamba exhibited 50 of these works. Her largest show to date, it was held from August 11 to October 31, 1967, at the Picasso Museum, housed in the Château Grimaldi, Antibes (the same building that appears in the background of his Night Fishing in Antibes). Lamba was pleased beyond words: it was the show that satisfied her most.

After the Picasso Museum show, Lamba refused to exhibit anywhere less prestigious, and she became inflexible in her demands. She told Aube that she would show only at the Beaubourg, but when the director asked her to bring two paintings to the museum, she refused, insisting that he come to her studio to view her work.

Lamba grew increasingly more isolated in her seventies, tired of people calling her to ask about Breton.

Although she longed to be sought out and recognized for her own work, she was difficult to reach. She saw a few friends and occasionally her children. Staying in Paris, she began creating complex cityscapes so painstakingly detailed they often took months to complete. These would alternate with large canvases of skies like Nuages roses et Turquoises (1980 (Pg. 87), in which clouds of blue, salmon, green, and gray draw the viewer to their light.

Marianne Clouzot, who had become a painter, sought Lamba out to rekindle their childhood friendship. She recalled:

I went to see her marvelous apartment, on the Boulevard Bonne Nouvelle, which was of extraordinary beauty. I was absolutely dazzled by her apartment and by her painting . . . . She had the appearance of being very content at being all alone. She was sufficient unto herself. She looked well, was not suffering, and painting occupied her entirely. I admired her a lot . . . . The paintings were huge . . . immense . . . with little touches of landscapes. I was very sur prised because it was painting that was very gentle, not at all hard, not at all cutting, as they had been in America.72

Lamba’s solitude, which disturbed others, “she claimed as a necessary condition for her work. It was an acetic conquest.”73 In the summer of 1988, Lamba wrote to Martine Cazin: “Being alone did not mean my lack of desire to meet neither beings nor friends but to be inhabited by one’s self, either to love or to create.”74

That would be the last summer that Jacqueline Lamba spent in Paris. She had a mild stroke and showed symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, and her daughter and son, at her suggestion, moved her to the countryside, to Rochecorbon, to a small 18thcentury chateau turned into a retirement home. There she made art “until she could no longer hold a pencil.”75 She died on July 20, 1993.

Salomon Grimberg, a Dallas-based child psychiatrist, writes frequently on the women of Surrealism. He curated the traveling Jacqueline Lamba exhibit (May 2001-February 2002) organized by the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

Acknowledgements

I thank the following individuals who so generously shared—variously—their time, memories, and archives with me during my research for this first lengthy English-language article on Jacqueline Lamba: Ethel Baziotes, Aube Breton Elléouët, Martine Cazin, Marianne Clouzot, Dominique de Noailles, Oona Elléouët, Therry Frey, Merlin Hare, Huguette Lamba, Ernestine Lassaw, Federica Matta, Fabrice Maze, Debbie Patla, Stephen Robeson-Miller, Martica Sawin, Vlady Serge, and Dolores Vanetti-Ehrenreich. —Salomon Grimberg

Notes

1. Th is painting was exhibited in Lamba’s first solo exhibition, at the Norlyst Gallery, New York City, in April 1944, and in “Surrealism and Abstract Art in America,” which opened at the San Francisco Museum of Art later that year. Q uote from Norlyst catalogue, n.p.

2. Aube Breton Elléouët (Jacqueline Lamba’s daughter), interview with the author, October 1999, in Paris.

3. The primary source on Jacqueline’s early years is her sister, Huguette Lamba, i nterview with the author in Paris, October 1999, plus her written reminiscences and her interviews with filmmaker Fabrice Maze, for his documentary film on Jacqueline Lamba.

4. Oona Elléouët (Jacqueline Lamba’s granddaughter), interview with the author in Paris, October 1999.

5. Merlin Hare (Jacqueline Lamba’s son), interview with the author in Victor, Idaho, September 1999.

6. Marianne Clouzot, a childhood friend, kept several portraits of Jacqueline L amba done at the time, dressed as a man, titled “Jacko,” which she showed me during an interview in Paris, October 1999.

7. Dolores Vanetti-Ehrenreich, a French actress who came to America to marry Teddy Ehrenreich, a physician, was a translator for the exiled Surrealists as their publication VVV was being developed. She remembered Lamba’s admiration for her mother, whom she referred to as a “grande dame” who had been on early reader of Proust. Interview with the author April 1999, in New York City.

8. Jacqueline Lamba told this to Teri Wehn Damisch, in Paris, October 1986.

9. Copies of these articles for the Bulletin de L’Union des Agriculteurs d’Egypte are in t he Merlin Hare archive.

10. Aube Elléouët interview. Lamba’s daughter, who had worked as a social worker dealing with children, believes that her mother’s problems began at birth, being abandoned at a crucial period of her development.

11. Fabrice Maze interview, Paris, October 1999.

12. Ibid.

13. Debbie Patla (Lamba’s daughter-in-law), interview with the author in Victor, Idaho, September 1999.

14. Vanetti-Ehrenreich interview.

15. Quoted in Martica Sawin, Surrealism in Exile and the Beginnings of the New York School of Painting (Cambridge, Moss.: MIT Press, 1995), 306.

16. Aube Elléouët interview.

17. Letter from the school; Elléouët archive.

18. See Julie L’Enfant, “Dora Maar and the Art of Mystery,” WA) (F96/W97), 15-20.

19. Damisch interview.

20. Jacqueline Lamba, “A Revolutionary Approach to Life and the World,” in Penelope Rosemont, ed., Surrealist Women: An International Anthology (Austin: University of Texas, 1998), 77.

21. Aube Elléouët interview.

22. Mork Polizzotti, André Breton: Revolution of the Mind (New York: Farrar Strous a nd Giroux, 1995), 404.

23. Vanetti-Ehrenreich interview.

24. Simone de Beauvoir, The Prime of Life (New York: Harper-Colophon Books, 1976), 278.

25. According to Mary Jane Gold, an American heiress living in France prior to W WII who assisted Varian Fry, head of the American Rescue Committee, in helping European artists and intellectuals escape the Nazis; in Polizzoti, Breton, 403.

26. André Breton , L’Amour fou (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 41.

27. Huguette Lamba interview.

28. Aube Elléouët interview.

29. Polizzotti, Breton, 415.

30. Eileen Agar, A look at My life (London: Methuen, 1988), 120-21.

31. This technique, invented by Oscar Dominguez, consisted of spreading diluted gouache with a wide brush and laying another sheet on top. When the two sheets separated, the result looked like rocks, caves, forests, and other natural formations.

32. Lamba lists the show in her handwritten curriculum vitae in the Elléouët a rchive; Huguette Lamba recalled that she exhibited two works in the show.

33. See Ruth Markus, “Surrealism’s Praying Montis and Castrating Woman,” WAJ (S99/S00), 33-39.

34. J.E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols (New York: Philosophical Library, 1981), 35.

35. See George Melly and Michael Woods, Paris and the Surrealists (New York: Thomes and Hudson, 1991), 19. Also, C.J.S. Thompson, The Lure and Romance of Alchemy (New York: Bell, 1990), 87-90. Flamel lived on the Rue Notaire, near the former belfry of the church St.-Jacques-la Boucherie, built in the 16th century a nd pulled down in 1802.

36. Jacqueline Lamba, interview with the author in Paris, August 1987, told how, a fter returning to France, she attempted to retrieve her early paintings from the Rue Fontaine apartment but found they were gone.

37. Paul Eluard, Letters to Gala (New York: Paragon Press, 1989), 230.

38. De Beauvoir, Prime of Life, 258.

39. Interview between Arturo Schwartz, Italian dealer in Surrealist art, and Jacqueline Lamba, November 1972; Elléouët archive.

40. Hayden Herrero, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (New York: Harper and Row, 1983), 250.

41. Telephone interview with Vlady Serge, September 26, 2000.

42. Damisch interview.

43. Ibid.

44. Letter from Lamba to Maar, September 18, 1941, reproduced in the Dora Maar estate sale catalogue, Les Livres de Dora Maar, October 29, 1998, Maison de la C himie, Paris, 12.

45. Michèle C. Cone, Artists Under Vichy: A Case of Prejudice and Persecution (Princeton: Princeton University, 1992), 124.

46. Ethel Baziotes was married to Abstract Expressionist William Baziotes; telephone interview with the author, October 4, 2000.

47. Anna Balakian, André Breton: Magus of Surrealism (New York: Oxford Press, 1971), 173.

48. Mary Ann Cows, Picasso’s Weeping Woman: The Life and Art of Dora Maar (Boston: L ittle, Brown, 2000), 159.

49. Conversation between Federica Matta and Roberto Matta, for the author, Paris, Ja nuary 1999.

50. Damisch interview.

51. Vanetti-Ehrenreich interview.

52. Therry Frey (David Hare’s last wife); telephone interview with the author, October 15, 2000.

53. Lamba interview.

54. Lamba revealed this, in Damisch interview.

55. Quoted in Surrealism in America During the 1930s and 1940s: Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection (Salvador Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Fla., November 7, 1998–February 21, 1999), 131–32.

56. See Julien Levy, Memoir of an Art Gallery (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1977), 280.

57. Angelica Zander Rudenstein, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (New York: A brams, 1985), 789.

58. Baziotes interview.

59. Ernestine Lassaw, married to sculptor lbram Lassaw, was a friend of both Lamba a nd Hare; telephone interview with the author, September 9, 2000.

60. Ibid.

61. Undated note; Elléouët archive.

62. Ibid.

63. Lamba’s handwritten curriculum vitae; in ibid.

64. Lassaw interview.

65. Baziotes interview.

66. Aube Elléouët interview.

67. When Lamba entered a retirement home in September of 1988, her daughter covered the expenses.

68. Stephen Robeson-Miller met Lamba in France in 1977, when he was preparing t he Kay Sage catalogue raisonné; telephone interview, October 22, 2000.

69. Huguette Lamba interview.

70. See Ronald Hayman, “Antonin Artaud,” in Margit Rowell, ed., Antonin Artaud: Works on Paper (New York: Abrams, 1996), 24.

71. Martine Cazin interview.

72. Ibid.

73. Ibid.

74. Letter to the author, October 1, 2000, quoting Lamba’s letter to her from July 8, 1988.

75. Aube Elléouët interview.

The P laT es

In Spite of Everything, Spring 1942

Oil on canvas

44⅞ x 60 inches

Private Collection

Roxbury Astres 1946

Oil on canvas

35 ⅞ x 52 inches

Roxbury Astres 1946

Oil on canvas

35 ⅞ x 52 inches

Intérieur d’une maison la nuit

1947

Oil on canvas

21⅞ x 27¾ inches

Sans titre (Tournesol)

1948

Oil on canvas 43¼ x 20⅛ inches

Autour d’une ville

1949 Oil on canvas

31½ x 50 inches

Autour d’une ville

1949 Oil on canvas

31½ x 50 inches

Sans titre (Tipis indiens)

1951 Oil on canvas 34¼ x 74⅝ inches

Sans titre (Tipis indiens)

1951 Oil on canvas 34¼ x 74⅝ inches

Cannes

1951–1956

La grande chaumiere

1956

Oil on canvas

61¾ x 72½ inches

La grande chaumiere

1956

Oil on canvas

61¾ x 72½ inches

Haute Provence 1962 –1971

Plaine de Simiane 1964

Oil on canvas

35 x 45⅝ inches

Plaine de Simiane 1964

Oil on canvas

35 x 45⅝ inches

Simiane 1964

Oil on canvas

39½ x 59½ inches

Cities 1970 –1983

Sans titre (ville de jour pointilliste)

1980

Clouds and Springs 1960 –1986

“

The secret would be to capture on canvas each form in its special light, that is to say at the precise moment in which the light becomes form. This would be like seeing a rainbow in the fullness of night.”

from Lamba’s mission statement, Norlyst Gallery catalogue, 1944