WOLFGANG PAALEN

Scenes for a Sorcerer

Published by Rowland Weinstein and Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco on the occasion of the exhibition

WOLFGANG PAALEN –Scenes for a Sorcerer

September 23–November 17, 2023

Weinstein Gallery

444 Clementina Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

©2023 Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco

Essay, Wolfgang Paalen—Scenes for a Sorcerer

©2023 Andreas Neufert

Publication directed and edited by Kendy Genovese

Photography of artwork by Michael Synder, Nicholas Pishvanov, Seth Matarese, and Carter Andereck

Designed by Linda Corwin, Avantgraphics

Text set in Garamond

Weinstein Gallery would like to extend our profound gratitude to Dr. Fariba Bogzaran and the Lucid Art Foundation, Mark Kelman, Andreas Neufert, and The Wolfgang Paalen Society, without whom this catalogue and exhibition would not be possible.

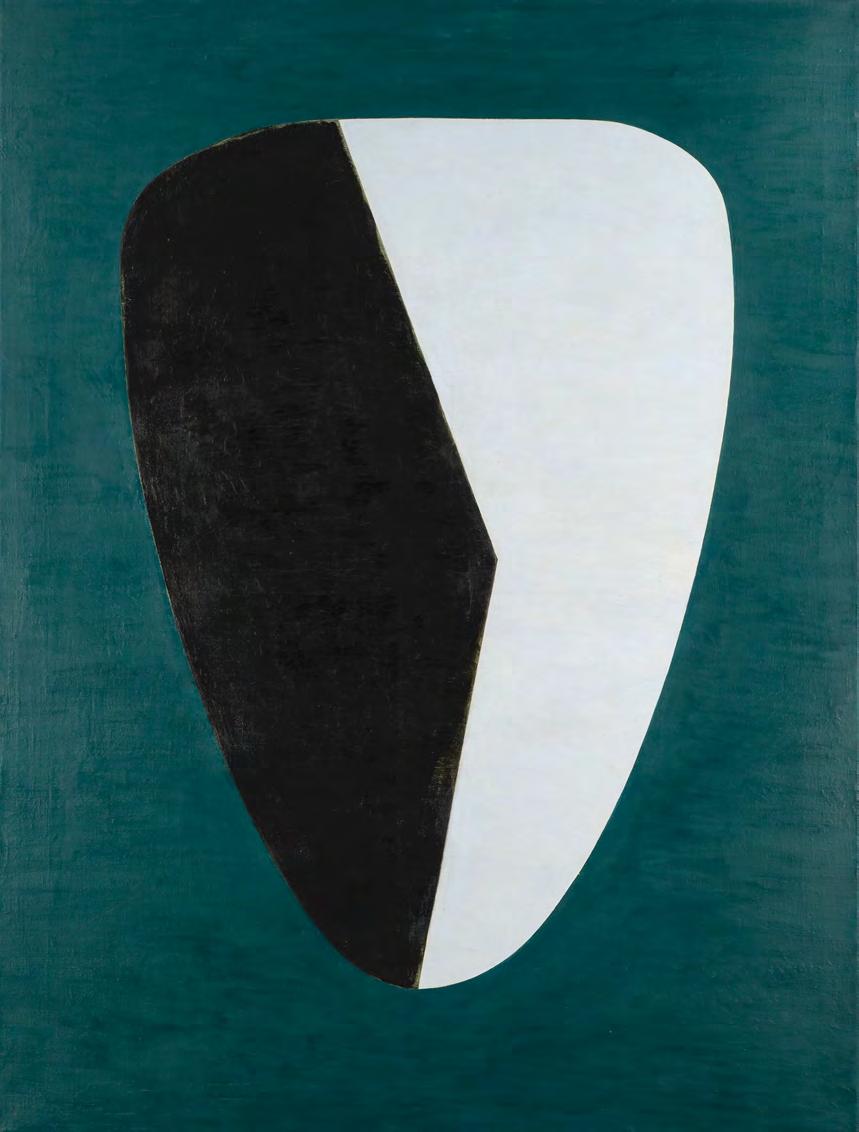

Front Cover: La table d’emeraude (detail), 1953

“Dear Julien, P. S. to my recent letter: Do you know Paalen’s work? I suppose that you have seen some reproductions. Among the young Surr[ealists]’s he ought to come out— he paints scenes “for” a sorcerer (you never see the witches). All this to hope that you might show him in N.Y.”

—Marcel Duchamp, letter to Julien Levy, January 1939

“It is time to leave Europe,” said Wolfgang Paalen to Helene Meier-Graefe when, on his last visit to Munich’s Marienplatz in the autumn of 1938, he wanted to invite her to dinner in one of the open alehouses. It was one of those still-warm September days, already robbed of its summery quality by the wind that blew fresh, rainy air down from the Alps into the city, but that hardly mattered compared to the other abysses in the illusory idyll of that day. On Marienplatz, in the midst of the Sunday bustle, a public gas-mask exercise was being held by the SS. It was about to turn into a folk festival.

Paalen had just turned 33, the divorced wife of the great German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe was already in her late fifties, but this did not stop him from continuing to address her in letters over the next few years as Aya, my you, and reassuringly telling her: “You, my Aya, are in all my future plans.” From the early 1920s in Berlin, he had an unusually passionate and at the same time self-reflective relationship with Aya, a woman who could have been his mother. He maintained this relationship, mainly by correspondence, until the end of his life. In 1958, a year before his death, Paalen wrote to her in retrospect: “The postscript of our letters was always such a beautiful dungeon for forbidden desires and missed fulfilment,” thus explaining the unusual duration of this relationship: Its intensity was rooted in the mystery of having been lived only as a possibility. Paalen was a man who loved the subjunctive, and the farewell to Aya, which anticipated the farewell to Europe, coincided with a period of exuberant artistic development centred on an obscurely illuminating dialogue with the possible feminine.

The central object of this dialogue, which took place in the innermost part of the self, was the work of art as the resonant field of an incredibly sophisticated mind and its desire to excavate so much that was unborn from the great lake of the unconscious that the future of humanity would shine out in it. And the means and end to which this commitment was consistently directed was precisely what the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once described as enlightenment through the evidence of the possible.

In January 1938, together with Marcel Duchamp, Paalen was responsible for the design of the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Palais des Beaux Arts in Paris, and under its ceiling of empty coal sacks he installed one of the first environments in the history of art, as Georges Hugnet later recalled: “(. . . the gently undulating floor was covered up to the ankles with withered oak leaves, and in the middle, in a fold in the floor, a long, fully irrigated pond was set up with real water lilies and reeds.” The opening was at 10 p.m., and visitors entered the grotto-like, ominously alienated exhibition hall through a corridor of transformed mannequins, illuminated only by the torches distributed to them at the entrance. The mannequin La Housse that Paalen decorated and Denise Bellon and Man Ray captured in photographs, with its silk scarf, the giant flying fox over its head and the eerie, mushroom-covered leafy dress, looked like one of the barely visible, floating totemic fairy creatures from his pictures, whose magic appeal Marcel Duchamp wished to paraphrase with his witchcraft title because they were painted with an enchanted mixture of ephemeral traces of candle smoke and seemingly electrified lines in oil. For their first public view in the Surrealist gallery Renou et Colle in May of the same year André Breton, who himself was on a journey to Mexico, had submitted a text that began with the words: “A lattice gate turns, this is the realm of Paalen. The great poplar avenue of its interior leads into the abyss of childhood with the images of fear (. . .),” thus aiming at the core of the emotion that Paalen wanted to use to open a new chapter of the Recherche surréaliste in the midst of the prevailing erotic context.

What Breton and Duchamp perceived and promoted as a mysterious darkness, as the warning undertone of a Romantic who seemed to rely on his feelings as the only standard, was soon revealed to be the large-scale project of a thinking painter who apparently felt comfortable in the knowledge that he could put painting and its moral meaning on a completely new footing.

In May 1939, he was the first of the Parisian Surrealists to set sail for the New World with exile in mind. Accompanied by his wife Alice and their mutual friend Eva Sulzer, he boarded a ship for New York shortly after the opening of his solo exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery in London. After a series of meetings with intellectuals, artists and gallery owners, and a visit to the National Museum of the American Indian, he set off again, but not, as planned, for Mexico, where the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo had invited him during her visit to Paris in 1938. As if guided by an invisible hand, he crossed the Canadian continent by train and arrived in British Columbia in June. With

his two companions, Paalen had embarked on an extended expedition through the Indian reserves of the Northwest Coast. From a local dealer in Wrangell, Alaska, he acquires the house front of a Tlingit chief, with a semi-abstract depiction of an enormous standing mother bear, with half-human, half-animal faces painted on her head and limbs, looking at the viewer in a suggestive, silent, but also questioning way. Rising up on her paws like a menacing monster, she welcomes the visitor with a laughing face, spread legs and open belly. Paalen had the large work sent to Mexico in advance, where he himself arrived in September 1939, shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, who were unaware of his adventurous plan, met him at the airport and accompanied him to Coyoacan, where he first settled in the symbolic neighborhood of the houses of Frida Kahlo and the most important author of scientific socialism, Leon Trotsky. In January 1940, in the new premises of the Galería de Arte Mexicano, he inaugurated a major surrealist exhibition that he had planned with Breton, who had remained in Paris for the time being, and the Peruvian poet Cesar Moro. In August of the same year, Trotsky was killed with an ice pick in a second assassination attempt ordered by Stalin. Paalen broke off his initially euphoric contact with the hermetically sealed circle of Mexican communist painters and retreated to San Angel. He had been preoccupied with mother religions since his early youth, and when, in 1943, he attempted to undermine Sigmund Freud’s entire edifice of totemism, incest fear and patricide outlined in the 1912 essay Totem and Taboo, a cornerstone of Surrealist beliefs, the mother bear stood behind his argumentation as silent but no less grandiose evidence.

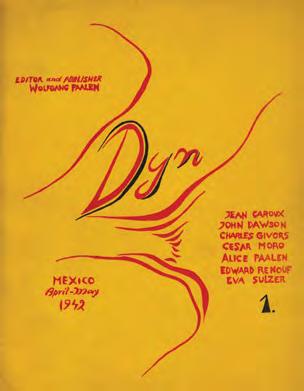

After his first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1940, where the American artists Baziotes, Pollock, Gottlieb, Newman and Motherwell saw for the first time the Fumages Paalen had painted in Paris, he sank into increasing loneliness in Mexico. “He writes, he paints incessantly, he reads instead of sleeping, and yet he feels he is achieving nothing, he has crises of terrible gloom and sadness, cruel doubts about what he is doing—and what remains to be done,” his wife Alice wrote worriedly to André Breton in New York in 1941. In the spring of 1942, the New York art world was astonished and surprised by the intellectual result of this endured and intense working phase, the art magazine DYN (from the Greek tò dynaton—the possible). In the first issue, he publicly bids his friend Breton farewell to Surrealism. In the second issue, published in July of the same year, he again shocked his former mentor with an inquiry on dialectical materialism and an article with the provocative title The Dialectical Gospel, a well-founded rejection not only of political dialectics, but above all of materialism as a philosophical concept.

The table, the tree, the ground beneath his feet had long been to him, in truth, wildly swirling collections of particles in which, microphysically speaking, you could reach for metres. And his paintings had since long reflected a hallucinated world of disintegrating matter, with fibrous figures shooting up to great heights before the eye, and an earth that cracked like ice right in front of you. They were studies of different kinds of twilight, of the pre-world, of

Top: Stikine House front, 1939

Bottom: Wolfgang Paalen´s studio building by Max Cetto, San Angel, Mexico, 1944, with the Totem Screen and Polarités majeures, 1940

the supposition that matter was light that had become heavy and the world of things swollen shadows that filled space like liquid gas. Nevertheless, he wanted to get to the bottom of the obstinacy of the materialistic conception of being, knowing that new principles of thought would produce a new kind of art, one that would no longer put the individual at the service of a higher idea. He called for nothing less than a complete break with the “simplistic concepts of Marx and Hegel” and a revision of the Surrealists’ close adherence to the axioms of Freud, in order to arrive at a new and entirely unique self-understanding of the artist, beyond personal desires, dogmas and systems.

By the time Vienna-born Wolfgang Paalen entered the Parisian surrealist scene in 1936, Breton’s avant-garde was already more than a decade old; and by 1941, when he distanced himself from it, the project that held it together had already become a transatlantic one, a European-American adventure of the mind in flight. As great as the attraction between the two intellectuals seemed to be in this relatively short period of time, the differences in their worldviews could hardly have been overlooked even before then. For Paalen, chance, that indispensable and much-discussed poetic device of Surrealism, did not reveal a fixed chain of events leading back to desire as the primary cause, as Breton believed. Rather, it released the bracket of consciousness over an ever-present, ever-fluctuating playground of possibilities in which the artist could participate. The choice of the ancient Greek term DYN for the title of his journal was a provocative reflex to the current debate on contingency in physics, which had become famous with Einstein’s statement “God does not play dice” at the probably most famous Solvay Congress in Brussels in 1927. With this statement, Einstein wanted to shoot down the quantum theory, in which Nils Bohr and Louis de Broglie had elevated the possibility to a scientific category. The new concept of light was astonishing in this respect, because it gave tremendous proof of what is only visible as an effect, and which is inconceivable without this effect: the dark universe suddenly appeared to be full of possible light that had not yet struck anything on which to appear. And the artist, by virtue of his special way of seeing, in which something always shines through, something always comes to the surface, like a shimmering, opalescent drop of oil on water, which can touch nothing without taking with it something else that no one has seen before, was able to help these possibilities, which can only be grasped by the human gaze, to their slumbering reality.

Paalen was a singular phenomenon; he was predestined to use the atmosphere of upheaval in New York from his exile in Mexico for nothing less than a tabula rasa, a complete revision of modernism, to overcome the paralysis in which artists found themselves at the end of the 1930s. With his magazine DYN, published from Mexico in five issues between 1942 and 1944, he briefly became the most important art theorist of the war years, and his editorial work allowed him to develop his intellectual powers to the full. Paalen’s brief stays in New York and two solo exhibitions at Julien Levy’s in

1940 and Peggy Guggenheim’s in 1945 made him known in art circles as a painter, but his predominant absence from the New York scene and the widespread reception of his groundbreaking essays in DYN (and in Form and Sense in 1945) ultimately fostered his image as a kind of intellectual secret agent who influenced events mainly indirectly through his fiercely debated ideas. His break with Breton over the thorny issue of Marxism also made it easy for the young American artists to avoid him, at the latest by the time they realized how important their original American self-image would become for the course of their success. Robert Motherwell, who had spent a few months with Paalen in Mexico in 1941, corresponded with him almost weekly between 1942 and ‘45, and enthusiastically promoted his ideas in New York until 1946-47, very quickly forgot how much he owed to the Austrian for his success in the fifties. In 1986, shortly before his death, he wrote to me that he had only known Paalen in passing and that if there had been any correspondence, his assistant had unfortunately destroyed it by mistake.

The fact that Paalen’s ideas are now recognized by almost all historians as influential, if not fundamental, in the nimbus of theories that dominated the climate of New York in the 1940s only testifies to their sharpness, decisiveness and clarity. This belated recognition remains, in retrospect, impressive evidence of the farreaching effect of these ideas on the creative atmosphere of an entire era. The painful paradox for the painter, however, was that the genesis and impact of his own work took a back seat, so that the theoretician’s fame was ultimately detrimental to his own career as a painter. As early as the forties, Paalen often regretted to friends his decision to make a name for himself as an intellectual, insisting on these occasions, with a plaintive undertone, that he was, after all, a ‘peintre avant tout.’ Perhaps this is why many of the artists who were still theoretically active in the forties, such as Motherwell, Rothko and Newman, became increasingly silent after 1950, when the art market and official criticism began to intervene in primary events.

In pre-war Paris, on the other hand, artists who, like Paalen, were also writers, buyers and sellers of primitive art, advisors and organizers of exhibitions, and private philosophers, were particularly recognized and welcomed. Breton was taken with the young Paalen

not only because of his aristocratic appearance, but also from the very beginning because of the unusual linguistic skill with which he was able to objectify the violent inner convulsions of his apparently crystalline mind. Manic-depressive in nature, he was just as quick to burst into exuberant enthusiasm and create a mood of new beginnings among his friends out of thin air as he was to sink into unfathomable sadness or destroy his counterpart with razor-sharp criticism. He seemed to possess the seismographic sensibility of a Kafka and the philosophical rigour of a Wittgenstein, and in mythladen New York he was often compared in appearance and visionary presence to T.E. Lawrence. One thing is certain: his point of view set him apart from his contemporaries long before his exile, and still makes him a peculiar case of modernism and its history, which finds it hard to find a place for him, seemingly unfamiliar with his life and work.

In fact, Breton had discovered the Viennese Paalen in the haze of Parisian abstraction. He took him under his wing in 1936. Surrealism had been in a political crisis since Breton’s dispute over Stalin’s show trials with Aragon. Everything in Breton was calling for new ideas and unconventional artists who could also think. And so it was that this man with the thoughtful countenance and a bewildering aura of sadness, of restless creativity and the burden of constantly doubting the meaning of things and of sinking into abysmal thoughts with equal relish, came across him just in time. Paalen seemed cultivated to him, serenely sad in a twisted way, pursuing the substance of life in art without any ifs or buts, as unsuited to everyday life as he was sensitive, as Breton had always wanted for himself. As a homeless Central European with an eccentric pedigree of Jewish avenue aristocracy, Viennese and Berlin Bohemianism and German Romanticism, he carried a real-life theme with him. Working on it seemed to keep him alive, but it was also likely to cost him his entire life.

Compared to the work of his contemporaries, Paalen’s first surrealist paintings of 1937 showed a new kind of shock, focused entirely on the power generated by the shudder of a sudden awakening of consciousness. The Fumage was congenial to this creative point of departure, and it also showed that this was the only way Paalen could reach the heart of his darkness: the line transforms

into the hallucinatory figure, electrifying itself, charging itself with imaginary figurations as in a waking dream. It shows a point of emotional compression, which is called a shudder, an echo of fear, and which allows what is felt to leap into form: very similar to the phantoms we project onto unfamiliar objects in the half-light, or the dream figures that lived on for a moment when we awoke as children in the twilight, filling the lifeless clothes on the chair in front of our bed with movement. Above all, Fumage shows the great importance of the line as an independent means of expressing the trembling, nervous in-between state called fata, waking dream or even epiphany. Paalen was interested in the electrifying movement of painting because it seemed to echo the electrifying movement of our consciousness, and the device he invented fully corresponded to this context.

Fumages were pictorial imaginings initiated by candle smoke, which also influenced the appearance and iconography of the larger oil paintings. With the Fumage, Paalen had confirmed the myth of the Kafkaesque mind, which uses the act of painting to trace the imponderable trajectories of thought. At the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London in 1936, he had already contributed a work he called Drawing, made with a candle (Dessin, fait avec un bougie). It consisted of a linear frame of black smoke stains without any further treatment, and clearly shows the importance of Fumage as a preliminary form of line. In the oil paintings, too, it plays the role of a gestural provocateur optique that merges with the painting or is almost indistinguishable from it. Autonomous attempts at Fumage, either on paper or on canvas primed

with white oil paint, are initially juxtaposed with the oil painting, in which the Fumage then recedes as the starting point for painting with brush and paint.

In the first pictures, from 1937, Paalen imposes an orderly pictorial structure on the actionist fumage design. Veristic means of painting are used in such a way that horizon lines, foreground and background become recognizable. However, the transfigurative creatures, rendered with tremulous, nervous brushstrokes, negate the concept of space and time imposed by the illusionist means of painting. In the many paintings entitled Paysage totémique, the visible coherence of the landscape is almost imperceptibly disrupted. Cracks, fissures and abrupt chasms hint at the emergence of an underworld hidden beneath the thin surface. Its inhuman character is also determined by the passage of time, which no longer belongs to time and yet seems to be trapped within it. The viewer is dependent on the unit of time of the sudden as a point of orientation. Everything in the painting points to this moment of shocked consciousness, in which the two appearances of the inner and outer image are superimposed. In this other state, the viewer witnesses a metamorphic change from the vegetable to the animal: what was still attached to the biomorphic, disordered substance under the ground develops into zoomorphic hermaphrodites, lifted into the vertical with long veils in weightless, glassy rigidity against a background foil that changes from cool blue and green-grey to purple.

Surrealism had always condensed the poetic heritage of Baudelaire and Edgar Allen Poe into one essential point: the attempt to expose consciousness to its own risk, as it were, and to achieve a differentiation of sensibility through its extreme states. Poe was exemplary in renewing horror as an isolated mode of aesthetic perception in poetry. Paalen used it in his paintings, but only to bring about the realization and recovery of its original childlike quality. Horror would eventually give way to a pure receptivity to what Poe had already described in his theory as surprise. For the horrible was nothing more than a secondary quality imposed on surprise by its sudden appearance. Paalen brings sudden horror back into focus as a central category of aesthetic experience in order to liberate it from its negative theological contexts. He uses the horror that seizes you when the devil jumps through the window and remains in the position of the jump. But he wanted to show that it is the devil that religions have used to suppress free thought. Muteness is the decisive effect of such an attack of sudden terror, but what speaks of the great Fumages of 1938 is the power of a melancholic longing to enter into conversation with this unspeakable being.

In his best works, Paalen was an artist with an extraordinarily finely tuned, detailed lyrical gift, who knew how to stage all the dialogical energies in this intrasubjective realm with sensitive delicacy. No painter before him had ever so precisely depicted this state of consciousness of sudden awakening from a deep dream. All the Fumages of 1938/39 span the light blue expanse between the edges of the picture, like an undulating canvas held in trembling. The small-scale events, like the silvery, filigree traces of the back of the brush, the sudden condensations of color, echo, resonate and add up to an impression of expansiveness that actually seems to reproduce something of the electrify-

Top: Orages magnétiques, 1938. This painting Paalen gave to André Breton shortly before his trip to Mexico in 1938 and it inspired the text on Paalen, written in a storm crossing the Bermudas. Private collection

Bottom: Paysage totémique, 1937 Oil and fumage on canvas. Lucid Art Foundation

ing processes that accompany the shock-like waking dream in the mind. Time and space, normally opposites, meet, touch each other for a moment with faltering breath, as if on the verge of death. But then something strange happens. The fear disappears.

Paalen’s decision to become a painter was clear by the age of 16, when he took sporadic lessons from the Berlin Secessionist Leo von Koenig—a virtuoso portraitist of the ashen, near-death faces of German intellectual life. After an unsuccessful application, he avoided the academy and oriented himself towards the French taste of the modernist Berlin salons and galleries, pursuing visual studies of Cézanne, van Gogh and Matisse, until he discovered Cubism during his first stay in Paris in 1925. The profound impression made on him by the Cubist paintings of the Analytical period never left him, and as if on an odyssey, he sought out areas of conflict in order to open up what he saw as an unrecognized potential in this art movement. He believed that he had discovered a special pictorial space for himself, an interplay between significant, semi-abstract forms and their resonance in the eye, and so it is not surprising that, from 1932 in Paris, he vehemently tried to resist the dogma of the non-figurativeness of abstraction with biomorphic and semifigurative pictures. The paintings of this period are a unified protest against the debate about pure, absolute form that prevailed among the purists around Mondrian. They attempt to approach the figures of a thought that had hitherto remained unconscious at a point where perception sets in, where it can be discerned by which desires, instincts or feelings it is driven. The thoughts that Paalen expressed in a survey by Christian Zervos that appeared in the Parisian art magazine Cahiers d’Art in 1934 are similar to those of Willem de Kooning when he mocked the ‘comfortable comfort of pure form’ in a speech at the Museum of Modern Art in 1952. Paalen’s paintings are neither pure and absolute, nor do they refer to an objective world outside the picture or to the familiar arsenal of symbolic forms that Surrealism claimed for itself. He remains within the reality of painting, as the abstracts demanded, but opens up a strange, magical world of archaic forms from a primordial world between possibility and reality, in which what is seen is transformed by the fact that it is seen and how it is seen. Only the act of seeing and thinking, that is, the underlying idea, decides which of the possible offers of form becomes a truly decipherable shape—and it is not the image itself that makes this realization. If the image of this shape is lost in the imagination of the viewer, it is no longer present in the picture.

Before the great Surrealist exhibition in Paris in 1938, a number of objects were created, including Paalen’s Le genie de l’espèce, a pistol made of delicate animal bones, and Nuage articulé, an umbrella covered with sponges. Subtly, two complementary levels of meaning are combined into a whole: death and the means that bring it about, and protection from the rain (rain could also mean hail of bombs) and the water-sucking that makes protection absurd. The ambiguity of Paalen’s black humor could only be guessed at, and both enor-

mously successful objects showed with aplomb what a powerful resonance the playful uncovering of subliminal correspondences and emotional similarities in an image can have when it traces the real process of the dream. That his humor concealed an almost prophetic view of the future was, in this light, perhaps a sad stroke of luck. In March 1939, both objects appeared in the London Bulletin of the Surrealists, Le genie de l’espèce as an illustration of a poem by E.L.T. Mesens on the absurd logic of the theorem that the end justifies the means, Nuage articulé as an illustration of a provocative statement on the Munich Conference of the European powers with the caption: “A sponge umbrella reminiscent of another umbrella that has achieved sad fame.” The rolled-up umbrella of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain was stylized, especially by the British public, as a reminder of his policy of appeasement, which had to be regarded as a failure after Hitler’s Czech offensive in October 1938. If Paalen’s intention with his objects was to uncover and pinpoint the slow and unnoticed emergence of war in the interstices of reality, he had succeeded.

When Breton acquired Paalen’s 1939 Fumage Combat des princes saturniens III at the Julien Levy Gallery shortly after his arrival in New York in 1941, he was completely focused on the cathartic effect of the primordial, mythical struggle it expressed. He was unable to see that Paalen’s Fumages anticipated the plastic automatism of which the American painter Robert Motherwell spoke in the early 1940s, as opposed to psychic automatism. His later Elegies of the Spanish Republic translated the rhythmic swelling of the Fumage from within into a painting of huge proportions, going back to a series of small drawings Motherwell had made when he came to Mexico with Matta in 1941 and decided to spend a few months with Paalen after the latter’s departure. On the pages of this Mexican sketchbook, spots appear within a framework of fine lines that seem to develop out of themselves to the edge of the figurative. They are similar to the semi-abstract forms that Paalen had created in 1938 in his ink paintings called Encrage, using rapid twisting movements and bubbles. They are a good example of how perception shifted to the process of developing form, and how the development of content could no longer be seen in isolation from it. Accustomed to the high intellectual level of the Surrealists, it is understandable that Paalen’s interest was initially focused solely on Motherwell, who had studied philosophy and who, in the course of their loose collaboration in DYN, had championed a number of American contemporaries, most notably Baziotes, Holtzman and Pollock, each of whose first publications of pictures appeared in DYN 6 in 1944. Until the mid-1940s, Motherwell was mainly associated with the European Surrealists, only coming into closer contact with Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman in 1945. The so-called Guggenheim Circle of Surrealists expanded decisively to include the young Americans, who vigorously debated all Surrealist and counter-Surrealist theories. This deepened an old division between Matta and Paalen over the concept of space and influenced its reception.

To appreciate the discrepancy between the ideas of such a pre-figurative space and the more traditional concept, it is sufficient to look at the interplay

of formal language and pictorial space that Matta had worked out in his paintings between 1939 and 1945. What immediately stands out is what contradicts Paalen’s ideas. In The Years of Fear from 1941-42, the early drawings of biomechanomorphic figures, which seemed to obsess Matta throughout his life, are transformed into a large, colorful picture; they fly through a pictorial space that at first glance seems as infinite as it is tectonically structured by its clear line structure and numerous perspective views. Despite the multi-perspectival glimpses and the multiple superimpositions of painterly layers, the painting suggests a measurable depth space. It seeks to draw the eye into the same empty box that de Chirico, Tanguy and Max Ernst had filled with material objects. Paalen had been working on his own version of cosmic pictorial beings during his early years in Mexico between 1940 and 1945. New Yorkers did not discover this until April 1945, when he showed his paintings in Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery.

Paintings like Les Cosmogones and Nuit tropicale evoked a new pictorial space because they were limited to pictorial, painterly means: Rhythm, light and color. Inspired by the rhythmically expressive figure reliefs on the outer walls of the Mayan temples of Palenque and the semi-abstract cubist imagery of the indigenous totem art of British Columbia, they worked out the cubist rhythm, which Paalen compared in his text to fugue and jazz, through a mosaic-like texture and complementary contrasts. In this way, he was able to create the atmosphere of a deeply moving, poignant encounter with beings that would act as an anthropomorphic resonance of a most elementary human sense. They would lead us to answers to elementary questions that were waiting somewhere in our consciousness. And when Paalen called these pictorial beings Cosmogons, he meant exactly this cosmic sense, and not some futuristic metaperson from the fourth dimension. Paalen understood them as a kind of pictorial variant of the ancient choros tragicos, the tragic chorus. In Nietzsche’s writings on The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music, the choros is understood as the basis of reality, conveying the idea of what it means to be. The Cosmogons were meant to present themselves. They were not meant to tell or announce anything, but to appear and disappear like a hallucination in order to guide man towards the event that was essential to him, but which no one could know except himself. Only in this way can it be understood why these images so resolutely renounce any representation, any narration, and why in them “(. . .) there is no life or death of a being, no individual landscape, the knotting and unknotting of a particular situation, but only the circle of eternal appearance and disappearance.”

Paalen had arrived in New York in March 1945 to prepare for his exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century gallery, which opened on April 17, immediately after Jackson Pollock’s second exhibition. Over the next few months, in the hope of forming a group with Motherwell, he stayed with Luchita Hurtado, his second wife, as a guest of the Motherwells. Alice RahonPaalen also exhibited immediately after him. It was hoped that a production of his play The Beam of the Balance, a kind of dramatized variation on the Cosmogon theme, would be staged in New York. William Baziotes, Motherwell himself, and Mark Rothko had each had their first solo exhibitions at Peggy

Guggenheim in the winter, and the intellectual exchange between American artists, who were essentially in competition with each other, began slightly to open up to what Paalen saw as a kind of possible joint activity akin to science. The fact that this did not succeed was, as in Mexico, certainly one of the main reasons why the basis for his group project was finally rooted in San Francisco, even though he enjoyed a high reputation among practically all the younger artists in question. Evidence of this can be found in the list of painters chosen by Barnett

Newman to form this potential new group, on which Paalen appears twice (once with his Surrealist works and once with his new works from Mexico).

Paalen’s analogy of the painter’s conception of the image and drama, the idea of possible, invisible forms outside the radius of familiar associations and identities, could spark off a dramatic play of the imagination via the image, which, by appealing to a starting point in the viewer’s identity, was completely directed towards that identity: this idea was certainly of inflammatory power

Wolfgang Paalen with his painting Les Cosmogones, 1945. Photo by Eva Sulzer

Wolfgang Paalen with his painting Les Cosmogones, 1945. Photo by Eva Sulzer

and can be found especially in the statements of the American artists in the first and only issue of the magazine Possibilities, which Motherwell published in New York in the winter of 1947/48 in a continuing analogy to DYN. In the preface (editorial statement) to Possibilities I, 1947, Robert Motherwell and Harold Rosenberg related the “greatest confidence in pure possibility” to the need to radically open up the concept of art in the time of political depression, and for Willem de Kooning the concept of possibility meant “a wonderful, uncertain atmosphere.”

In 1948, one of the two children Luchita brought into the Paalen household from her previous marriage died of polio in Mexico. The couple decided to move with the family to San Francisco, where they worked with Gordon Onslow Ford and Lee Mullican in a newly formed artist community: the Dynaton Group. They lived partly together in a large house in Mill Valley and had solo exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Art and a group exhibition at the Stanford University Art Gallery, where he also presented parts of his essay on the new spatial concept he had been working on for years. It was published as a catalogue on the occasion of the group exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Paalen’s continuing desire to maintain his main center of life in Mexico and to rekindle his friendship with André Breton during an extended stay in Paris then led to a friendly divorce from Luchita and new plans. From Mexico, Paalen travelled to Paris in 1951 with his new girlfriend, the American painter Marie Wilson. He lived there with short interruptions for the next three years in Kurt Seligmann’s studio house in Paris, built by André Lurçat. He reconciled with Breton, spent summers at Breton’s house in Saint-Cirq-Lapopie, participated in the invention of surrealist games, such as Ouvrez-Vous? and L’un dans l’autre, and painted a considerable body of lyrical abstract paintings, which were exhibited in Paris in 1952 (Galerie Pierre) and 1954 (Galerie Galanis-Hentschel) with remarkable success. One of the four issues of Breton’s art magazine Medium-Communication Surréaliste was dedicated to Paalen. After an extended trip to Germany, he returned to Mexico in 1954. Paalen’s last years in Mexico were marred by increasing health problems, mainly due to his bipolar (manic-depressive) disorder. With the help of his friends and supporters, Eva Sulzer, Jacqueline Johnson and Gordon Onslow Ford, he managed to buy an old house and studio in Tepoztlán, Morelos, where he lived and worked for the last years of his life. His passion for collecting Olmec sculptures led him on increasingly adventurous expeditions and ventures into the wilderness of eastern Mexico and the Yucatán. As an expert and source of ideas, Paalen assisted the American filmmaker Albert Lewin on his epic film The Living Idol. In 1958, Paalen received André Pieyre de Mandiargues and Octavio Paz in Tepoztlán, both of whom published texts about Paalen after his suicide. On the night of September 25, 1959, Paalen left his hotel room at the Hacienda San Francisco Cuadra in Taxco de Alarcón, where he sometimes sought relief from his depression. He was found dead the following day, shot

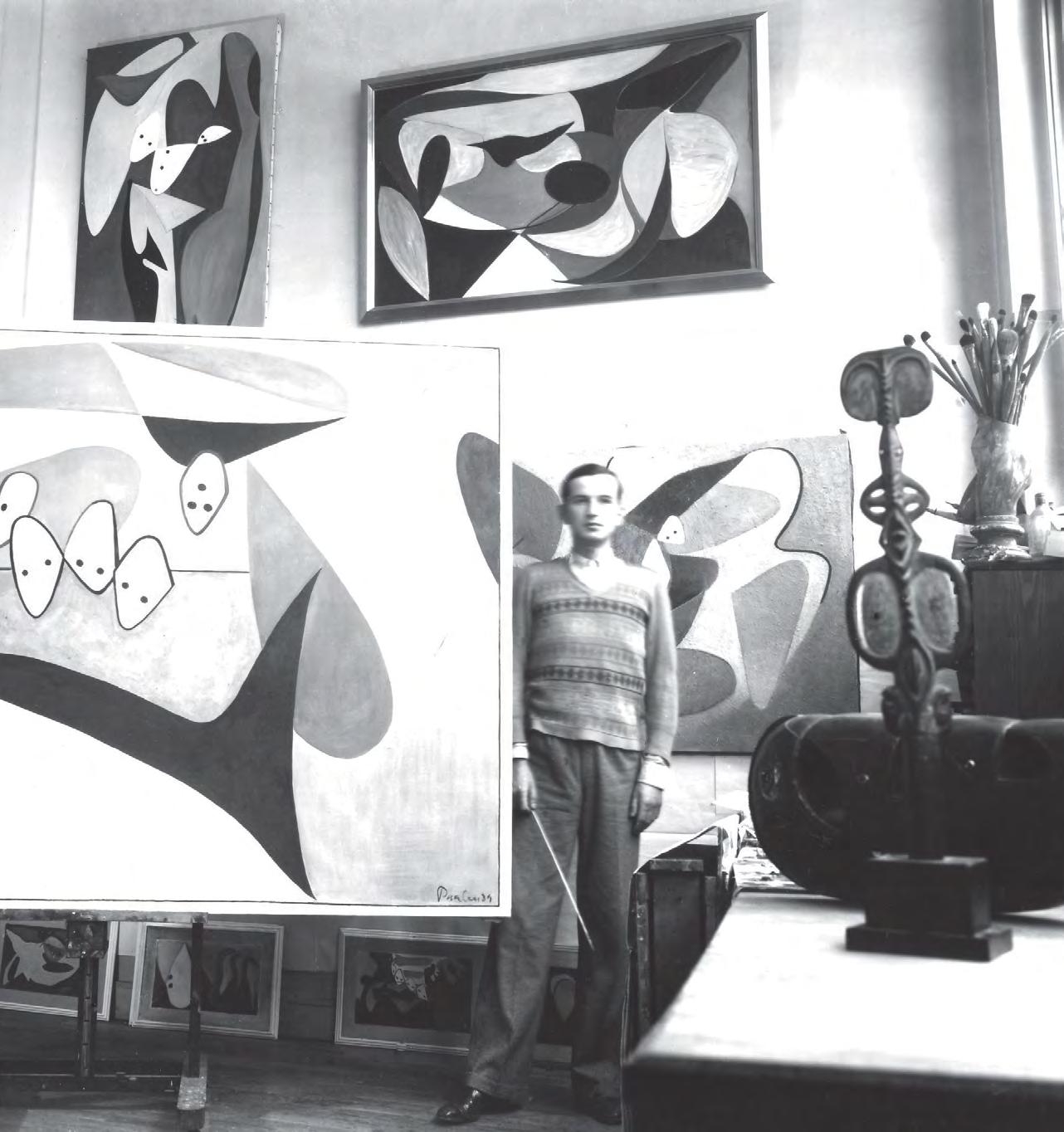

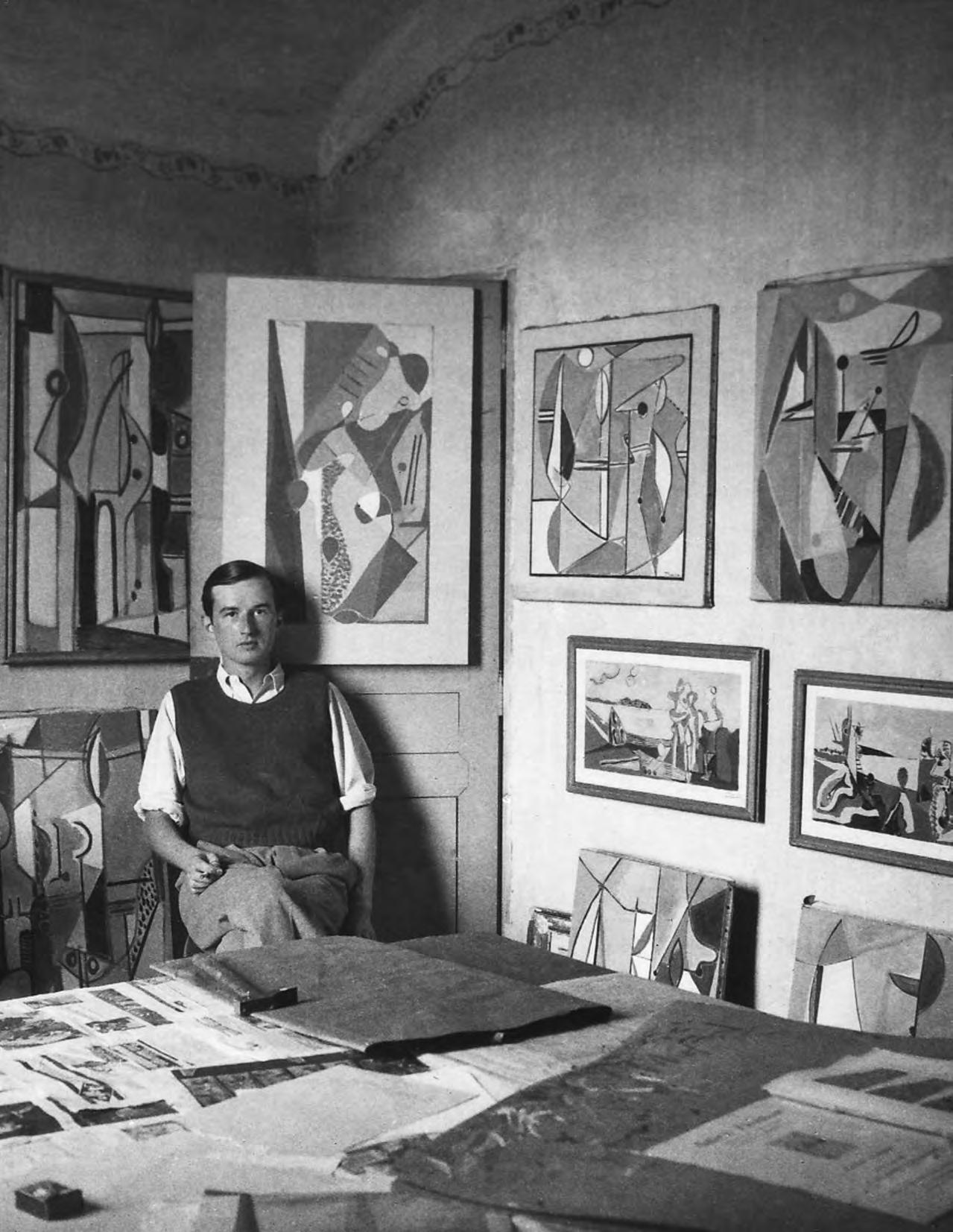

Cubism and Cycladic Period

1927–1937

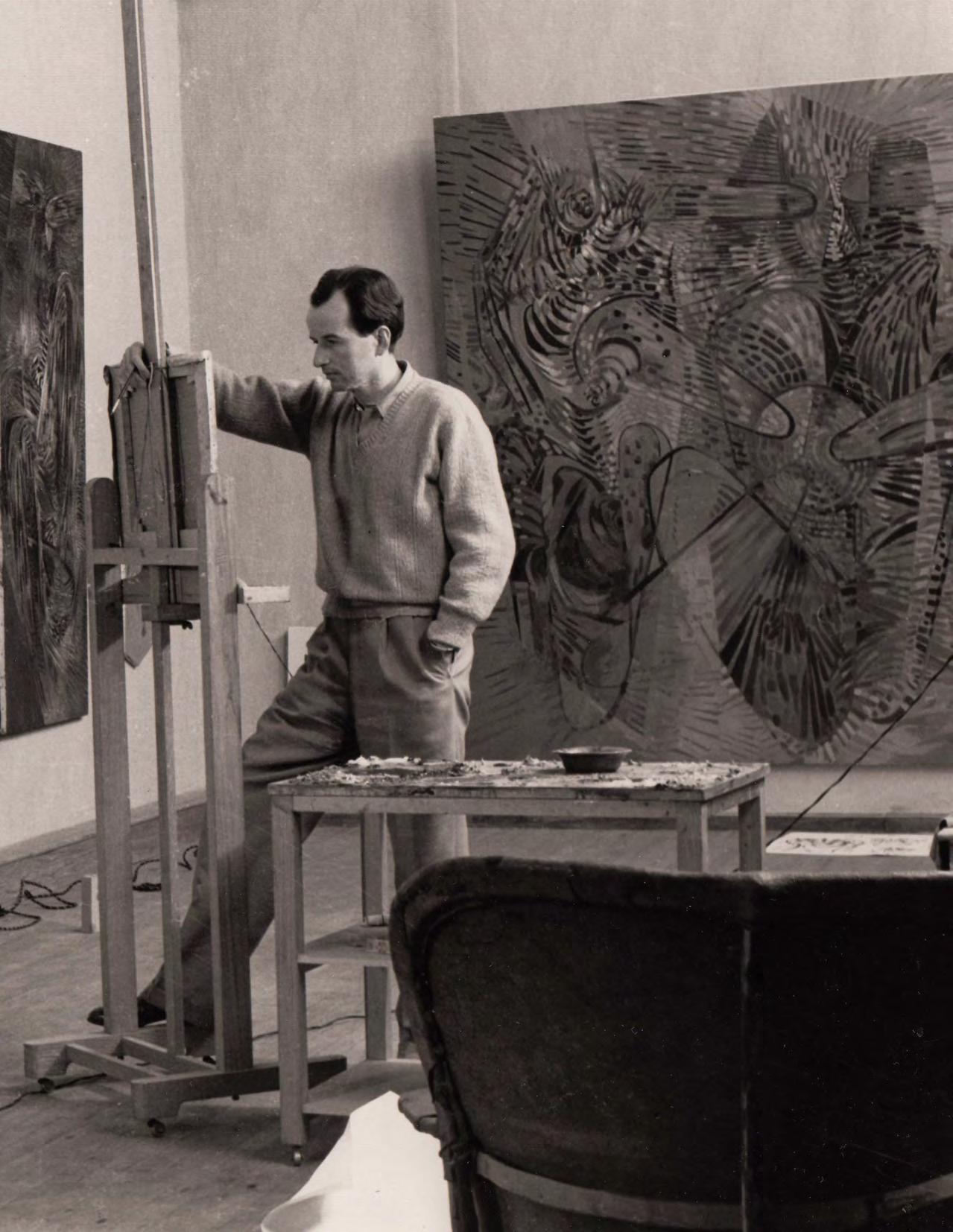

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio in Paris, rue Pernet, 1934

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio in Paris, rue Pernet, 1934

1927

Signed “Paalen” lower right, dated “1927” lower left Oil on canvas

13½ x 10½ inches

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio, Cassis, 1932

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio, Cassis, 1932

1932

Signed “Paalen” lower left

Oil and tempera on canvas

36 x 23½ inches

Cycladic Head

1935

Marble on wood stand

12 x 9½ x 4½ inches

Courtesy the Lucid Art Foundation

1935

Oil and tempera on canvas

51½ x 38¼ inches

Courtesy the Lucid Art Foundation

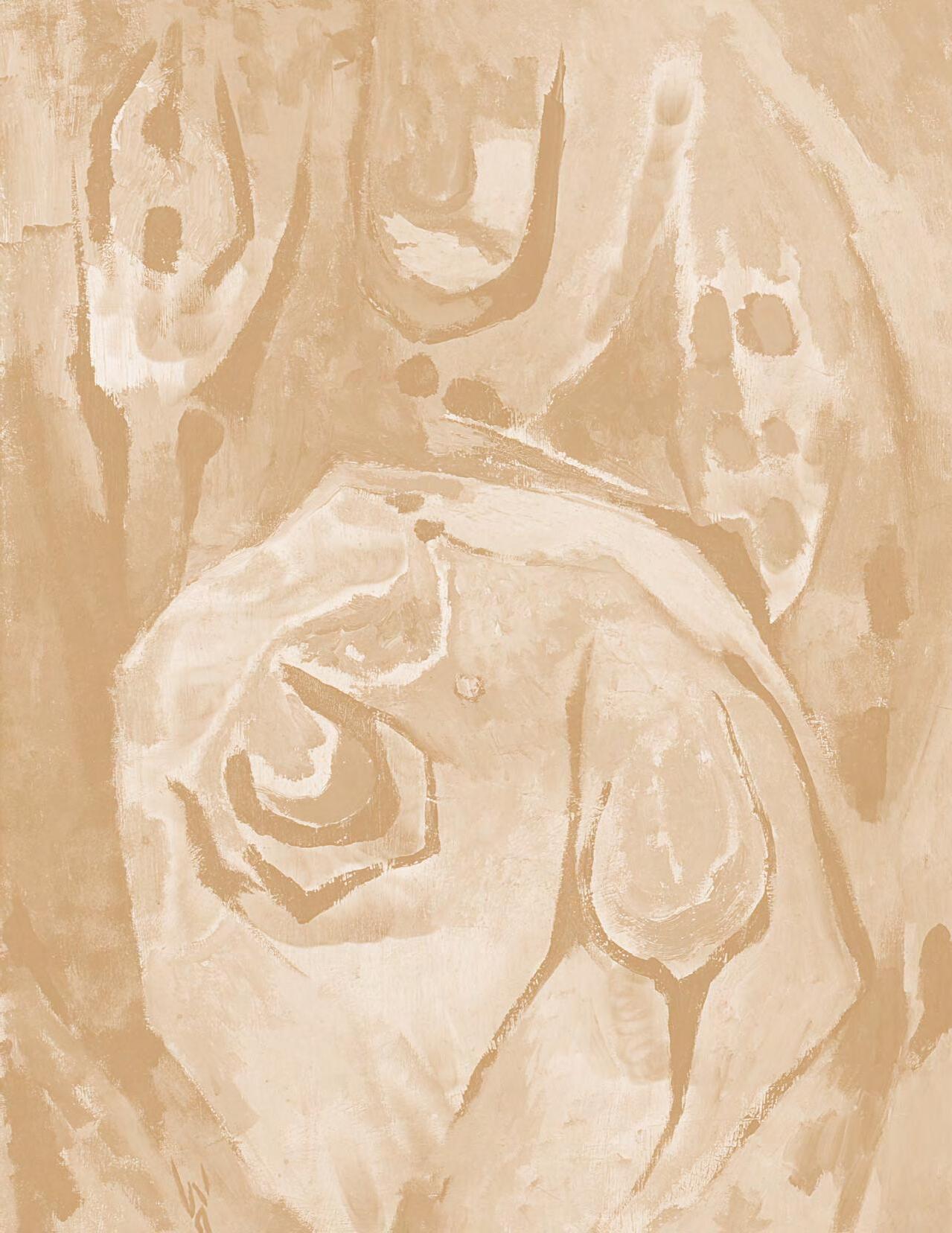

“Among the pictures of this period is to be found “La femme blonde.” (The Blonde Woman). She constitutes in her utter simplicity the sister to those Greek sculptures that seem the true images of the first human being. Like violincellos without strings that vibrate in themselves. It seems as if certain awe forbade the instrument to be strung.”

– Gustav Regler, Wolfgang Paalen, 1946

La femme blonde

1936

Oil and tempera on canvas

25½ x 36 inches

Wolfgang Paalen’s L’Heure exacte on display at the International Suurrealist Exhibition, Mexico, 1940

Wolfgang Paalen’s L’Heure exacte on display at the International Suurrealist Exhibition, Mexico, 1940

“In its unadulterated form, fumage is pure poetry; it describes, in a sense, how thought is formed from the nebulous cloud within the mind that precedes a clear thought. To describe it, he [Paalen] came up with the metaphor of the wish that knocks from within, unrecognized, on the door of consciousness and wants to make itself heard.”

– Interview with Andreas Neufert

Nature morte à la mouche

1937

Fumage on canvas

16½ x 13 inches

Collection Mark Kelman, New York

L’heure de la femme où la terre se mouille

1938

Signed with initials and dated “WP 38” lower left

Ink, watercolor and candle smoke on paper

11⅞ x 15⅝ inches

Private collection, Berlin

Fumage

1938

Signed with initials and dated “WP 38” lower right Candle smoke on double cardboard paper

14¾ x 19⅝ inches

Private collection, Berlin

Wolfgang Paalen, Avant La Mare installation, Exposition Internationale du Surrealism , Paris, 1938. Bettman Archive/Getty Images

Wolfgang Paalen, Avant La Mare installation, Exposition Internationale du Surrealism , Paris, 1938. Bettman Archive/Getty Images

Poultry and mammal bones, brass, velvet mounted in black wooden box with glass lid

9 x 15 inches (animal bones)

12 x 16½ x 2½ inches (wooden case)

Authentic replica after the original (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City), edited by the Wolfgang Paalen Society e.V. in a limited edition of 8 copies and one proof copy. Paalen Archive No. 38.27 b, Edition No. 4/8 Courtesy the Wolfgang Paalen Society e.V.

L’Heure exacte (II)

1939/1940

Oil, feathers, and glass eyes on wood 15 x 15 x 1⅝ inches

Collection Mark Kelman, New York

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio, San Angel, Mexico, 1947. Photo by Walter Reuter

Wolfgang Paalen in his studio, San Angel, Mexico, 1947. Photo by Walter Reuter

“I saw him [Einstein], I knew where he was and I used to go and watch and draw him until I had my drawings complete and then I painted him. I could never get him to sit for me because he wouldn’t sit for anybody . . . This painting was poetically conceived . . . emerging through it something like a firmament—suggested stars—suggested lights . . . ”

– Wolfgang PaalenPortrait d’Einstein

c. 1940-1941

Signed with initials “WP” lower right; inscribed and dated indistinctly “WP Albert Einstein 1940” on the verso Oil and fumage on canvas 36 x 28⅝ inches

Origines

1940

Signed, dated, titled and dedicated on verso ‘“Origines”

au poète César Moro son ami WP 42’

Oil on canvas

18⅛ x 15 inches

Private collection, Berlin

1941

Signed with initials and dated

“WP 41” lower right

Oil on canvas

45 x 57½ inches

Courtesy the Lucid Art Foundation

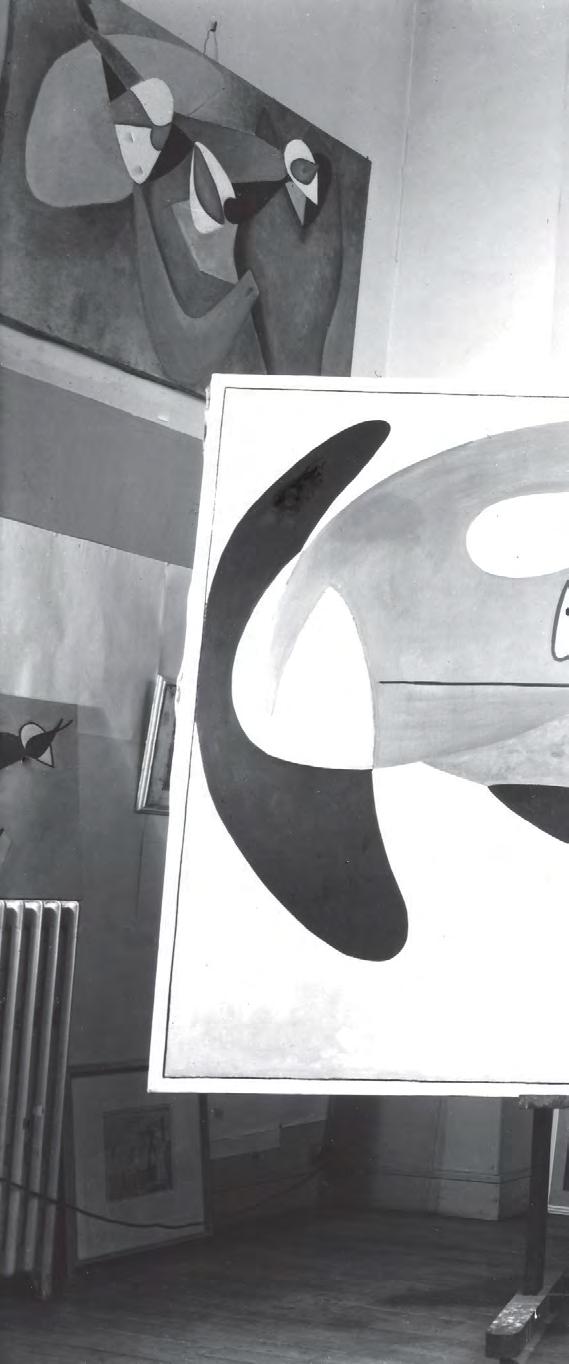

Wolfgang Paalen´s studio in San Angel with Les Cosmogones and Messenger, c. 1945

Wolfgang Paalen´s studio in San Angel with Les Cosmogones and Messenger, c. 1945

“The final version of this magnificent, swirling, mysterious painting—perhaps Paalen’s highest achievement—can be seen as a profound attempt to evoke, from within, the experience of universal consciousness. With its tile-like references to trees, water, and sky, which are suggestive of the coastal rain forest as a cosmic garden, Les Cosmogones is an invitation to acknowledge a universe of becoming, within which we’re luminous particles.”

– Colin Browne, curator of I had an interesting French artist to see me this summer—Emily Carr and Wolfgang Paalen in British Columbia, Vancouver Art Gallery

Les Cosmogones

1944

Signed with initials “WP” lower right

Oil on canvas 96 x 93 inches

Dynaton Exhibition, San Francisco Museum of Art, 1951

Dynaton Exhibition, San Francisco Museum of Art, 1951

Projét pour un monument

1945

Wood Sculpture: 94½ x 15½ x 3 inches

Base: 9 x 16 x 19 inches

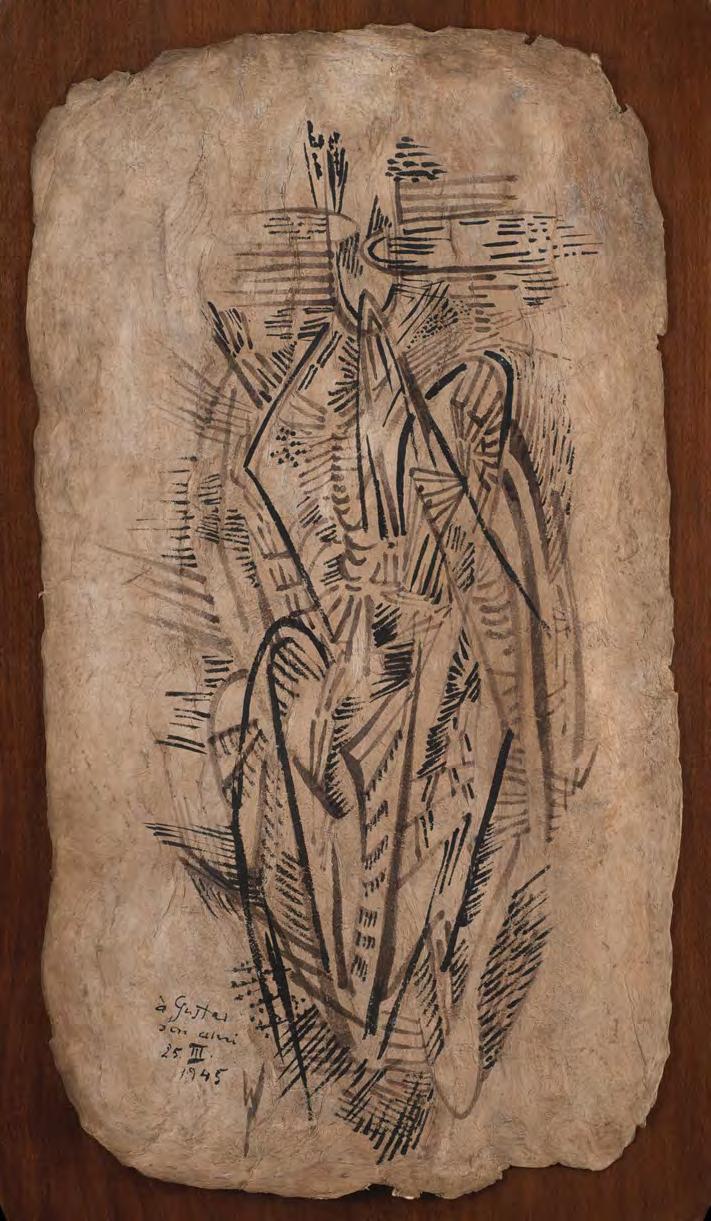

Untitled 1945

Signed with initials “WP” lower left India ink on Amate paper 26 x 14¼ inches

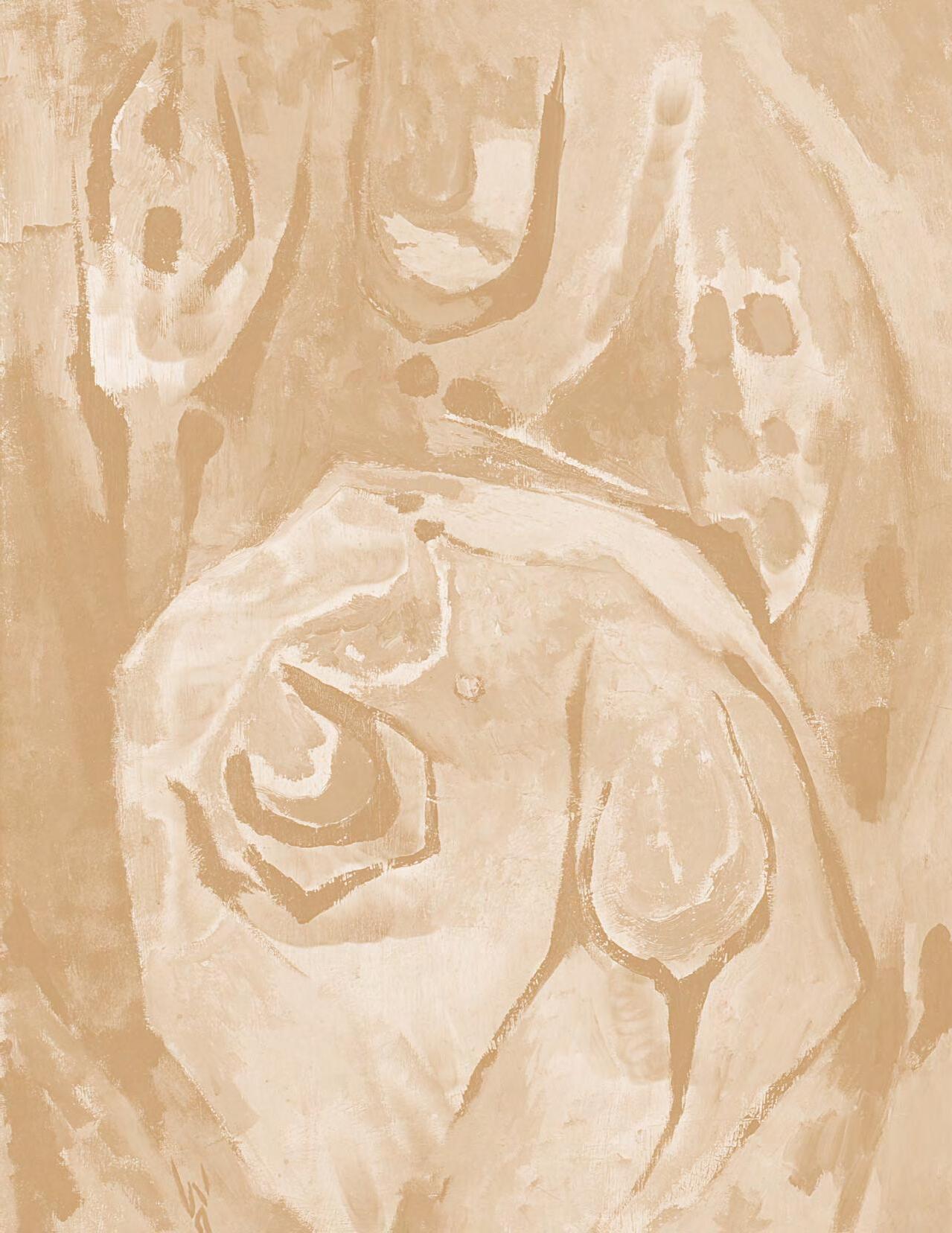

Signed with initials “WP” center right

Oil and ink on Amate paper

18 x 10¼ inches

Courtesy the Lucid Art Foundation

Untitled 1946

Signed with initials “WP” upper right

Ink and gouache on Amate paper 24⅝ x 15⅝ inches

Collection Mark Kelman, New York

“In the Cosmogons series the interactivity of the spectator and the universe is rhythmically expressed. There is no longer any arbitrary encrustations of anthropomorphic fragments or any non-puritanism. The radiant curves coordinate themselves into great “personages” which are the new protagonists of the eternal Promethean play. The planetary sense becomes a true cosmic consciousness. There is no longer the life and death of a being, any individual landscape, the knotting and untying of any particular situation, but rather the circle of the eternal coming and passing.”

– Gustav Regler, Wolfgang Paalen, 1946

Untitled 1946

Signed, dated and inscribed

“à René Lefevre-Foinet son ami Wolfgang Paalen Mexico 1946” lower right Gouache on Amate paper 23¼ x 10⅝ inches

1949

Signed with initials and dated “WP 49” lower right

Oil on canvas

80½ x 60¾ inches

Courtesy the Lucid Art Foundation

1948

Tzalam “wild Tamarind” wood

Height: 44⅞ inches

1949

Signed with initials “WP” lower right; signed and inscribed ‘à Madeleine Rousseau son ami Wolfgang Paalen Paris 1952 “Cosmogones”’ on verso

Wolfgang Paalen in Kurt Seligmann´s studio in Villa Seurat, Paris, 1954

Wolfgang Paalen in Kurt Seligmann´s studio in Villa Seurat, Paris, 1954

Signed with initials and dated

“WP 53” lower right

Oil and fumage on canvas

31⅞ x 23⅝ inches

1953

Signed and dated “Wolfgang Paalen 1953” lower right

Oil on canvas

51⅛ x 63¾ inches

Signed with initials and dated

“WP 53” lower right

Oil on canvas

36¼ x 25½ inches

1954

Signed with initials “WP” lower right

Oil and fumage on canvas

19¾ x 25⅝ inches

“Paalen’s thought processes possess no antecedent in surrealism . . . I believe that no more serious or more continuous effort has ever been made to apprehend the texture of the universe and make it perceptible to us. I can think of no more rewarding task for those truly independent critics who are anxious to steer clear of well-trodden paths than to pay the most careful attention to Paalen’s evolution.”

– André Breton, “A Man at the Junction of Two Highways”

André Breton at his 42 Rue Fontaine studio, 1960. Photo by Ida Kar © National Portrait Gallery.

André Breton at his 42 Rue Fontaine studio, 1960. Photo by Ida Kar © National Portrait Gallery.

1955

Signed with initials and dated

“WP 55” lower left

Oil on canvas

51 x 38 inches

“The main concern is not to operate for eternity, but in eternity.”

– Wolfgang Paalen

Excerpted from an extensive chronology written by Andreas Neufert

1905

Wolfgang Robert Paalen is born on July 22 in Vienna. Parents: Clothilde Emelie Gunkel and Gustav Robert Paalen. The Hofburg in Vienna purchases one of the first vacuum cleaners (model “Atom”), invented by Gustav Robert Paalen.

1910

Wolfgang starts school. Gustav Robert Paalen acquires the Portrait of Señora Sabasa García by Francisco de Goya. He develops a lightweight household vacuum cleaner, the “Dandy,” predecessor of the “Vampyr,” which is assemblyline-produced by AEG from 1916. Wolfgang’s brother HansPeter Paalen is born.

1914

July: Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia; start of the First World War. Gustav Robert Paalen becomes Austrian agent-general of the central purchasing company. Joins the Friends of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum. Acquires Lucas Cranach’s Venus and Cupid.

1916

Gustav Robert Paalen donates 250,000 gold marks to the Friends of the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum Berlin for the acquisition of the Titian painting Venus with the Organ Player, previously with Oskar Kokoschka, and arranges its transport from Vienna to Berlin.

1917

Due to the war, the Paalen children receive private lessons from the organist and tutor Georg Lubrich, a student of Max Reger. Lubrich ignites the Paalen children’s passion for spiritualism and clairvoyance. Private tuition in Greek, music theory, and the philosophy of Schopenhauer and the Vedas. Wolfgang Paalen experiences a hypnopompic in front of the manor forest, which had been devastated by an infestation of black arches (Lymantria monacha); in his 1938 text “Paysage totémique,” he stylizes this experience as a spiritualist awakening. He draws a series of nudes that he later overpaints in black.

1919

Wolfgang’s brother Michael-Josef is born in Sagan. May: the family visits Paris during the Versailles Peace Conference.

1921

January: the Paalen family moves into the Villa Caetani Grenier in Rome. Wolfgang studies antique art under the Prague-born archaeologist Ludwig Pollak and painting with Leo von König.

1924

Wolfgang returns to Berlin; applies unsuccessfully to study at the Academy. Contact with the art critic, Julius Meier-Graefe, affair with the latter’s second wife Helene Meier-Graefe (Aya). Attends the sculpture classes of Adolphe Meyer. Meets the Swiss painter Serge Brignoni and the music student Eva Sulzer. First Impressionist paintings. Participates in the autumn exhibition of the Berlin Secession. Visits Gottlieb Friedrich Reber’s Van Gogh and Cézanne collection at Château de Béthusy near Lausanne together with Eva Sulzer.

1925

Apartment-cum-studio in Paris. Friendship with Hans Reichel and Ursula Schuh. Summer in Cassis. Visits Georges Braque.

1927

Follows Aya to Munich. Participates in Hofmann’s summer school in Cassis. Studio in La Ciotat near Cassis.

1928

Visits the exhibition L’Époque héroïque du Cubisme in Paris. Visits Braque in Varengeville-sur-Mer. His parents divorce.

1929

Death of his brother Hans-Peter in the Wiesengrund asylum in Berlin-Wittenau. Stock market crash and start of the Great Depression. Group exhibition at the gallery of Alfred Flechtheim, who supports Wolfgang by purchasing his work. Paalen fully commits to becoming a painter.

1930

January: return to Paris; studio-apartment adjacent to Jean Hélion and Hans Hartung. May: meets Max Beckmann again. June: participates in the Salon des Surindépendants (together with Meret Oppenheim, Richard Oelze, Hans Hartung, and Luis Fernández). Summer in Cassis. Attends Fernand Léger’s open painting classes. His work is shown at the Rhenish Secession in Düsseldorf. Meets Picasso at Galerie Rosenberg in Paris. Hélion introduces him to Georges Vantongerloo, Piet Mondrian, and Auguste Herbin.

1931

Summer visits to Berlin, Sagan, and the Baltic Sea with Eva. In Sagan, his brother Rainer, who suffers from bipolar disorder, attempts suicide with a pistol, possibly in Wolfgang’s presence. During his six-week recovery period, Rainer studies religious, occult, and spiritualist literature, which he discusses with Wolfgang. His engagement with contemporary texts about death and eschatology

(Maeterlinck, Dunne, Renan, et cetera) consolidates Wolfgang’s anticlerical views and channels his interest toward Surrealism. Meets Alice Philippot (Alice Rahon).

1932

Paalen develops a post-Cubist pictorial language with potentially figurative elements. Summer: travels with Alice to Normandy and Brittany, reads matriarchal myths and Das Mutterrecht (Mother Right) by Johann Jakob Bachofen. Visits Reber’s Picasso collection in Lausanne together with Alice. Visits Picasso’s studio in Paris. Group exhibition at Galerie Bonjean in Paris.

1933

January: Hitler is appointed Reich Chancellor. July: Paalen travels to Spain and visits the prehistoric cave paintings of Altamira. Back in Paris, he uses driftwood roots to create a series of fetish-like objects (Objets faits avec racines).

1934

Purchases Cycladic idols. Exhibition of indigenous wooden sculptures from British Columbia at the Musée Trocadéro. Exchanges with Christian Zervos. Joins the artists’ group Abstraction-Création. The American collector Albert Gallatin acquires the painting Visages planetaires (1934) for the Museum of Living Art at New York University. On March 27, 1934, Paalen marries Alice. Travels to the Cyclades. Leaves Abstraction-Création together with Hélion and Arp. Solo exhibition at Galerie Vignon, Paris. Review by Christian Zervos in Cahiers d’Art. Another visit to the prehistoric caves at Altamira.

1935

Short essays by Paalen in Réponse à une enquête (Cahiers d’Art no. 14, 1935) on overcoming the divide between Abstraction and Surrealism. Group exhibition Thèse—Antithèse—Synthèse at the Kunstmuseum Luzern. March: trip to London with Alice, visit from Henry Moore, whom he introduces to Roland Penrose. April: visits Valentine Penrose at Château Le Pouy (Gascony), an affair begins between Alice and Valentine. They spend the summer at Valentine’s house in Licq-Athérey (Pyrenees). Paalen illustrates Valentine’s volume of poetry Le nouveau Candide. From Licq, he visits Lise Deharme at her palais in Montfort-en-Chalosse, where André and Jacqueline Breton are spending their holidays with Man Ray and Paul Éluard. Breton introduces Paalen to his group of Surrealists. Exhibition of ritual masks from British Columbia at Galerie Ratton in Paris. December: Paalen participates in the Exposition de dessins surréalistes at Galerie Les Quatre Chemins in Paris. He is given the Surrealist name “Le Castor de la treizième dynastie” (Beaver of the Thirteenth Dynasty).

1936

January: start of Alice’s affair with Picasso. For the International Exhibition of Surrealism in London (New

Burlington Galleries), Paalen prepares four portfolios, each containing fifteen Surrealist drawings. April: solo exhibition at Galerie Pierre in Paris. May: exhibition of Surrealist objects, together with objects of non-European tribal art at Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris; alongside objects made of roots and clay, Paalen displays L’heure exacte. Participates in the London exhibition with twelve works, including his first fumage, Dictated by a Candle. Participates in the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism at MoMA, New York. August: Alice has an abortion which also spells the end of her affair with Picasso. Paalen suffers bouts of severe depression. Trip to Cassis with Eva, reconciliation with Alice. Start of their ménage à trois. Journey to Athens, Delphi, and the Cyclades. Work on an iconography of the waking dream using fumage. October: return to Paris, work on his first fumage-inspired oil painting, Pays interdit. Fumage becomes his main mode of artistic expression. Start of the Spanish Civil War. Deepening friendship with Breton. News breaks about the Stalinist show trials and terror in the Soviet Union. Éluard and Aragon break with Breton on account of his support for Trotsky and opposition to Stalin.

1937

Breton opens Galerie Gradiva in Paris, designed by Paalen, Yves Tanguy, and Marcel Duchamp. Alice and Valentine spend time in India. Paalen contributes illustrations to Forneret’s Le diamant de l’herbe. Participates in the Surrealist exhibitions in London (Artists International Association) and Cambridge (University Art Society). July: trip to Munich, visits the Degenerate Art exhibition. Begins to contemplate emigration. Visits his brother Rainer in Bohemia. August: in Cavalaire and Cassis with Jean Varda, Eva, and Alice. Nudism, dream reincarnation, free love. Illustrations for the program booklet of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu enchaîné at the Theâtre de la Comédie in Paris and for the new edition of Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror. Acquires the model of a Haida totem pole from Ratton. Paysage totémique series. October to December: preparations for the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme at the Palais de Beaux Arts (Galerie Wildenstein) in Paris. Works on the exhibition concept and design, officially responsible for “Eaux et broussailles” (water and foliage). Editorial work on the Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme, which is published for the exhibition in 1938. Alice’s affair with Georges Gérard, who later dedicates his autobiography, L’Abeille noire, to her.

January: Paalen participates in the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme at the Galerie des Beaux Arts (Galerie Wildenstein) in Paris with five objects, four paintings, and the installation Avant La Mare (an artificial pond with reeds and water lilies); he also covers the entire exhibition floor with leaves. Further exhibitions in Amsterdam (Galerie Robert) and Den Haag (Koninklijke Kunstzaal). Object Le genie de l’espèce. Breton’s Trajectoire du rêve is published by Gallimard with an illustration by Paalen (Rêve de glaçon),

together with Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror. Paalen produces his key works Orages magnétiques, Plumages, Orphée, Ciel de pieuvre, Taches solaires, Pays medusé, and Battle of the Saturnian Princes. March: annexation of Austria by the Nazis. April: Breton acquires Orages magnétiques and writes the essay “Non plus le diamant sur le chapeau” for the catalogue of the Paalen exhibition at Galerie Renou et Colle, Paris (in June). Herbert Read and Roland Penrose plan a counterexhibition to Degenerate Art in London (originally to be titled “Banned German Art”); due to the policy of appeasement, it opens in July under the title 20th Century German Art Paalen participates as the only Surrealist. Breton signs the Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art in Mexico with a searing condemnation of National Socialism, fascism, and Stalinism. September: Munich Agreement. Paalen produces his first encrages (encres automatiques, ink drawings). Translates and illustrates the Verzeichnis einer Sammlung von Gerätschafte n from Lichtenberg’s Göttinger Taschen-Calender for Minotaure no. 12–13, 1939, which also contains Breton’s article “Souvenir de Mexique” and Kurt Seligmann’s report from British Columbia, “Entretiens avec un Tsimshian.” December: Frida Kahlo visits Paris and invites the Paalens to Mexico.

1939

Duchamp arranges exhibition opportunities for Paalen in London (Guggenheim Jeune, February 1939) and New York (Julien Levy Gallery, May 1940). The Gitxsan totem pole acquired by Seligmann in Skeena is exhibited in the peristyle of the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. Preparations, together with Breton, for the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Mexico, which Paalen is to curate. February: solo exhibition at the Guggenheim Jeune in London. Herbert Read reviews the exhibition in Minotaure. Peggy Guggenheim acquires Paysage totemique de mon enfance (1937). Paalen joins the Société des Americanistes in Paris, together with Seligmann. May: Breton gives Paalen a letter of recommendation for Jan van Heijenoort (Trotsky’s assistant in Mexico), requesting a meeting between Paalen and Trotsky. Paalen boards the MS Nieuw Amsterdam and travels to New York. On board he works on the essays “Surprise et inspiration” and “L’image nouvelle” and studies books on quantum theory and cosmology. May 19: arrival in New York. Received by Julien Levy, first contacts with American artists (William Baziotes, Gerome Kamrowski). Visits collections of North American indigenous art (Heye Foundation Museum of the American Indian and Museum of Natural History) and studies relevant literature (Curtis, Cook, Barbeau, Besson, Swanton). Starts his travel journal Voyage Nord-Ouest. June: departure for Ottawa, where he visits the French anthropologist Alfred Barbeau. Onward journey via Winnipeg and Jasper through the Native American areas around the Skeena and Fraser Rivers to Prince Rupert; reads Trotsky’s The Lesson of Spain, first notes for Paysage totémique. Voyage on the HMCS

Prince Robert via the coastal islands and Ketchikan to Sitka, Alaska. Via Juneau to Wrangell, where he visits Walter C. Waters’ Bear Totem Store and acquires a partition screen

from the Chief Shakes’ house of the Naanya’aayi clan of the Shinkukedi, painted with a depiction of the Bear Mother. Via Hazleton and Kispayax back to Prince Rupert. Trip with Barbeau to the Queen Charlotte Islands and visit to the community longhouse of the Mamalilikala tribe of the Kwakiutl in Mimkwamlis on Village Island. August: visits the Canadian painter Emily Carr in Victoria and onward travel via Alert Bay to Vancouver. Visits the Golden Gate International Exhibition in San Francisco. September: Hitler invades Poland, start of the Second World War. Paalen’s US transit visa expires; he arrives in Mexico City on September 14, received by Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Juan O’Gorman. Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer, and Gustav Regler are interned in French concentration camps (Le Vernet and Les Milles) as potential enemies of the state. Benjamin Péret is arrested in Rennes as a Trotskyist. Roberto Matta, Nicolas Calas, Yves Tanguy, and Kay Sage manage to leave France for New York. November: Frida Kahlo divorces Diego Rivera. Paalen attends the Day of the Dead festival in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, together with Rivera. From 1939 onward, most of the leading left-wing intellectuals in Mexico toe the Stalinist Comintern line. Trotskyists (including Paalen) are automatically accused of collaborating with the Nazis. The Kahlo’s home in Coyoacán becomes a focal point of the political battles fought within the artist community. Paalen moves to San Ángel; preparations for the Surrealism exhibition in Mexico. Exhibition poster with image of a snake. Disagreements about the exhibition’s emphasis on the original Surrealists; the Mexican artists are unsure whether to align with Surrealism (and as such also with Trotsky and Breton) or form an independent group. Also shown at the exhibition are replicas of Nuage articulé, Chaise envahie de lierre, and L’heure exacte, drawings by anonymous asylum inmates, masks and figures from Paalen’s South Pacific collection, and ritual dance masks from various regions of Mexico from Rivera’s collection. The collection of indigenous art from British Columbia is retained by Mexican customs.

1940

January: Opening of the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Galería de Arte Mexicano, Mexico City. César Moro adopts Paalen’s liberal political line against Stalinism in the preface of the exhibition catalogue. As a result, the Mexican painter David Siqueiros describes the exhibition and catalogue as “Bretonian aesthetic crime.” April: opening of his solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York with twenty-three paintings, one object, encrages, and fumages. Reunion with Varda, Tanguy, Sage, Onslow Ford, and Seligmann. Last public appearance before his withdrawal from the group around Breton. William Baziotes, Gerome Kamrowski, Adolph Gottlieb, Jackson Pollock, and Barnett Newman attend the opening. Positive reviews. Smoldering dispute with Breton over dialectics and Surrealist doctrine; Paalen questions the need for a male leader in principle. With his unconventional views and criticism of Dalí, he becomes known in New York as Surrealism’s only dissenting rebel. In

a series of experimental paintings and drawings inspired by Louis de Broglie’s study Matière et lumière, Paalen develops a new concept of space (Infra-Space). The picture as a pulsating force field of conflating vortexes of waves and particles. Inseparability of space and spatial experience through pictorial means. Paalen campaigns for the release of Breton and others from France. A first attempt on Trotsky’s life is unsuccessful (May 24), police raids of Paalen’s and Rivera’s homes; the latter subsequently goes into hiding and flees to the USA. Paalen discovers that his letters to Breton had been intercepted. Pleads with Julien Levy to request special asylum from President Roosevelt and help raise travel funds for the Surrealists stranded in Marseille.

1941

June: Breton arrives in Martinique. Urged by Peggy Guggenheim, Pierre Matisse, Kay Sage, and David Hare, who had provided travel funds and visa guarantees, Breton decides to settle in New York; Victor Serge, the Soviet dissident who had accompanied him, travels on to Mexico, where he is joined in November by Esteban Francés, Benjamin Péret, and Remedios Varo. July: Paalen sends the manuscript for Paysage totémique to Breton in New York, openly criticizing dialectical materialism. Breton immediately asks Paalen to objectify his theories. After reading the essay “L’image novelle,” Breton asks him not to leave the group. September: Matta takes Robert Motherwell to Mexico, who stays with Paalen for several months. November: work meeting with Moro and Motherwell to found DYN magazine; Paalen tells Breton about the imminent launch of DYN. Breton breaks off all contact with Paalen and plans the launch of his journal VVV. Surrealist group exhibition at the New School for Social Research.

1942

March: first issue of DYN with “Farewell au Surréalisme” (Paalen’s declaration of withdrawal). Survey on dialectical materialism. June: first issue of VVV with a repudiation of Paalen’s ideas. July: DYN 2 with sixteen primarily critical responses (from Bertrand Russell, Meyer Schapiro, Albert Einstein, Clement Greenberg, and Pierre Mabille, among others). In “L’evangle dialectique,” Paalen deconstructs dialectics from a linguistic perspective. DYN and Paalen’s theories are fiercely debated among New York’s artistic circles. With his text “Surprise et inspiration” in DYN 2, Paalen attempts a pragmatic celebration of cognitive and imaginative powers and a sober rehabilitation of the concept of revelatory, visionary inspiration. October: DYN 3. Duchamp designs the exhibition First Papers of Surrealism in New York. Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery opens in New York as a nexus for Abstract and Surrealist art. Paalen’s mother Emelie dies; his brother Rainer dies in a Czech mental asylum (suspected euthanasia by the Nazis). Gordon Onslow Ford and Jacqueline Johnson move into El Molino, an old mill building in Erongarícuaro, Michoacán. Jacqueline translates for DYN. Paalen becomes a figurehead

for dissident Marxists in Mexico. Trip with Miguel Covarrubias to Tlatilco and La Venta (archaeological centers of the Olmec culture).

1943

Discord between Paalen and Matta about the conception of Surrealist pictorial space. Matta plans a competitor journal to DYN in New York and workshops with Motherwell, Pollock, Lee Krasner, Fritz Bultmann, William Baziotes, and others; Matta demonstrates the fumage technique. Paalen creates chromatic, mosaic-like “picture beings.” Preliminary notes for The Beam of the Balance, a visionary play about a young couple that, along with Doctor Faustus, sets out for the utopian city of EO; a reckoning with political totalitarianism. Paalen’s collection of totem art from British Columbia is shown in San Ángel. Publication of DYN 4–5 with the influential essay “Totem Art.”

1944

August: Paalen’s prologue on the liberation of Paris (“Today and Tomorrow”) in DYN 6 with the essay “On the Meaning of Cubism Today,” as well as the first reproductions of works by American artists like Jackson Pollock, William Fett, and Harry Holtzman.

1945

February: Exhibition at the Galería de Arte Mexicano, Mexico City. March: René d’Harnoncourt and Covarrubias show Paalen’s collection from British Columbia at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City (El Arte Indígena de Norte Amerérica). May to June: exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in New York. Barnett Newman lists Paalen in a private note titled “America has a new art movement (the first authentic art movement here),” along with Pollock, Rothko, Hoffman, Gorky, Baziotes, and Motherwell as “the men in the new movement.” Paalen meets Luchita Hurtado del Solar through Isamu Noguchi. News of his father’s death. August: atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. November: Paalen’s “Form and Sense” appears in Motherwell’s publication Problems of Contemporary Art. Completion of the play The Beam of the Balance.

1946

Three-month stay in New York with Luchita, including trips to Motherwell’s Quonset Hut in East Hampton on Long Island, where Paalen’s new play is read. Autumn: solo retrospective at Galerie Nierendorf in New York. Gustav Regler contributes to an autobiographical text by Paalen, which is published in parallel with the exhibition as a first monograph of the artist. Several-month stay with Louise Nevelson.

1947

January: return to Mexico. Trip to Bonampak and the excavation sites of the Olmecs. Divorce from Alice; marries

Luchita. February: obtains Mexican citizenship. Winter: no. 2 of Problems of Contemporary Art: Possibilities is published as the founding text of Abstract Expressionism with key statements from DYN. “Conspiracy of silence” (Motherwell) regarding Paalen’s innovative role in New York.

1948

February: Paalen and Luchita travel to New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Géo Dupin visits Paalen in Mexico. November to December: Paalen and Luchita visit Motherwell in East Hampton. Visit from Rothko and Newman to discuss the setting-up of a new art association. Solo exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. In Mill Valley he meets Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, and Jean Varda. Work on the essay “Metaplastic.” With Onslow Ford’s help, Paalen buys a large, old, wooden house in the densely forested Mill Valley area near San Francisco. Also, through Onslow Ford he meets Lee Mullican, who had approached Ford after reading DYN

1949

February: preface to the catalogue for Lee Mullican’s exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Onslow Ford shares a studio on the decommissioned ferry Vallejo in Sausalito, which he had purchased together with Jean Varda. Paalen moves into the house in Mill Valley.

1950

Metaplastic exhibition at Stanford Art Gallery, Palo Alto, with talks by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Paalen, and Onslow Ford.

1951

January: the newly established association exhibits at the San Francisco Museum of Art under the title A New Vision Ancestor room with indigenous art from Paalen’s and Ford’s collections. Publication of Dynaton in book form with the essay “Metaplastic.” Paalen divorces Luchita, who then marries Lee Mullican. He meets the painter, Marie Wilson. August: Paalen returns to Mexico. Extensive travels through Yucatán, travelogue essay about the matriarchal culture of the Olmecs. Visits Edward James in Xilitla together with Onslow Ford. Exhibition at the Willard Gallery in New York.

1952

August: trip to Paris with Marie Wilson. They stay at Kurt Seligman’s atelier-building, Impasse Villa Seurat 1, Paris. Visits Péret, Varo, Arp, and Giacometti, meets Octavio Paz and André Pieyre de Mandiargues. The Olmecs essay “Le plus ancien visage du monde” is published in Cahiers d’Art Reconciliation with Breton, visit to Saint-Cirq-Lapopie. October: exhibition at Galerie Pierre Loeb in Paris. Portrait of Breton.

1953

February returns to Mexico by plane. June: returns to Paris, where he produces an extensive series of lyrical-abstract

paintings. Spends the summer with Breton in Saint-CircLapopie, along with Toyen, Varo, and Péret.

1954

May: exhibition at Galerie Galanis-Hentschel in Paris. Separates from Marie Wilson. Summer: stays at a health resort in Badenweiler with Helene Meier-Graefe and subsequent trip through Germany. Short article in Medium–Communication surréaliste (“Die Situation der Malerei”) and a piece for Breton’s book project L’Art magique. October: return to Mexico by plane.

1955

Moves into an atelier-house in Tepoztlán, Morelos. Solo exhibition at Galerie Paul Kantor in Los Angeles. June: Friendship with the American filmmaker Albert Lewin, contributes to his film The Living Idol.

1956

January: César Moro dies in Lima. February: exhibition at the Galería de Arte Mexicano, Mexico City. Short story “Paloma Palomita.”

1957

Paalen contracts malaria. In a fever, he fires several shots into the ceiling with his revolver. After visiting Onslow Ford in Inverness and Luchita in Los Angeles, he travels to Mérida, Yucatán, in the summer to oversee the purchase of the hacienda San Antonio Dziscal. Increasingly severe episodes of depression. Short stories “Der Axolotl,” “In der Hacienda,” and “The Story of the Peruvian Mirror.”

1958

January: suicide of Óscar Domínguez. March: Bona and André Pieyre de Mandiargues visit Paalen in Tepoztlán together with Octavio Paz. Paalen marries Isabel Marín, the younger sister of Diego Rivera’s first wife, Lupe Marín. September: Meret Oppenheim persuades Paalen to write to a Swiss graphologist and request an analysis. He plans a trip to Switzerland for treatment, which he never takes. October: exhibition at Galerie Antonio Souza, Mexico City. In letters to friends, he mentions the possibility of suicide (“discreet exit”). Becomes implicated in a scandal in connection with illegal exports of pre-Columbian art to the USA. Intermittent short phases of intense artistic productivity. Last visit to Onslow Ford in Inverness, gives him important papers and pictures for safekeeping.

1959

September: solo exhibition at Galerie Antonio Souza in Mexico City. Death of Benjamin Péret. On the night of September 24, 1959, twenty years after his arrival in Mexico, Paalen ends his own life with a gunshot to the head, near the hacienda San Francisco Cuadra in Taxco.