GRANTS and the OLD GRANTITE CLUB

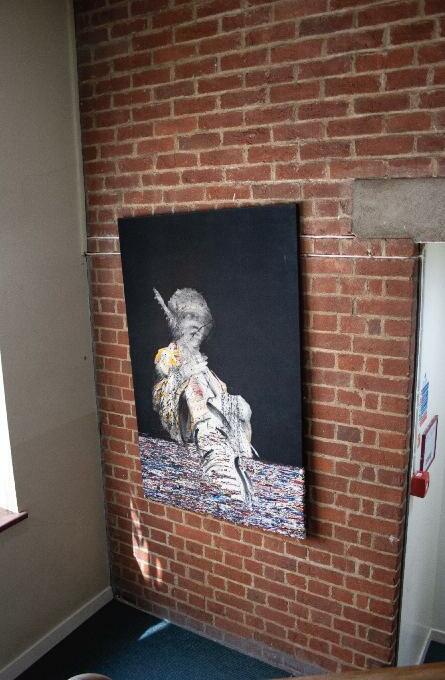

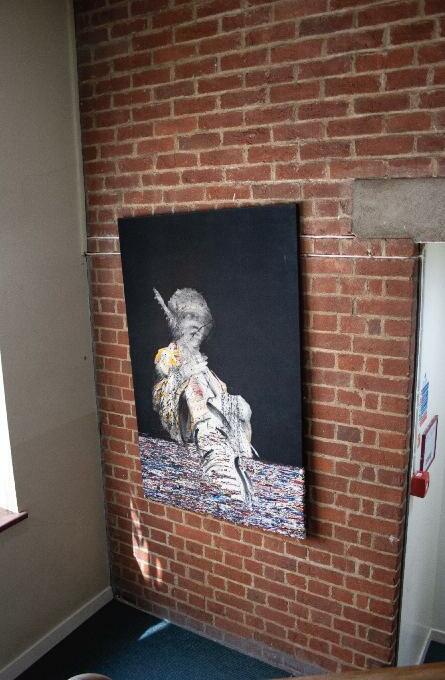

Mrs. Richard Grant (Mother Grant III), painted in about 1815

Mrs. Richard Grant (Mother Grant III), painted in about 1815

A History

GRANTS and the OLD GRANTITE CLUB

NASCITUR EXIGUUS, VIRES ACQUIRT EUNDO OGC The Old Grantite Club 2022

First published in 2022 by Barrington Publications on behalf of the Old Grantite Club, Westminster School, Dean’s Yard, London SW1P 3PB

Copyright © The Old Grantite Club 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN: 978-0-9926607-1-0

Set in Palantino and designed by Oonagh Connolly

oonagh@candc-design.com

Printed in the UK by Severnprint Ltd

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher ’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

3 CONTENTS Forewords 1959 Adrian C. Boult 5 1986 F. D. Hornsby 6 2022 Dominic C R Grieve 7 Histories and Memories Grants’ History to 1959 9 Lawrence Tanner Grants in the 19th Century 13 H. D. Nicholson and Arthur Southey Grants 1959 to 1986 21 Joan Fenton Grants 1986 to 2022 25 Simon Mundy The Old Grantite Club 1921-1959 51 Lawrence Tanner and William van Straubenzee 1959-1986 72 Simon Mundy 1986-2022 74 Tim Woods Lists House Masters 76 Heads of House 77 Presidents of the Old Grantite Club 84 Acknowledgements 85

4

FOREWORDS

1959

Sir Adrian Boult D.Mus., LL.D.

It falls to me as President of the Old Grantite Club to commend this History of Grants and of the Old Grantite Club to all who read it. It is, of course, primarily designed for, and of interest to, those who were fortunate enough to pass their years at Westminster Up Grants. But it will also be of interest to a wider Westminster public and is part of the distinctive contribution of the Old Grantite Club to Westminster ’s Quartercentary Year

For the history of the house we have been able to call upon the unrivalled authority of Mr. L.E. Tanner who was, I think, the very first boy who spoke to me and was kind to me when I entered the House in 1901. His account of the fortunes of the House with the longest unbroken pedigree of any Public School makes fascinating reading, set in the background of the adventurous years in which Grants has formed part of the School. The history of the Club has been assembled by our Honorary Secretary, Mr. W.R. van Straubenzee, relying partially on the old minute books of the Club and partially upon the personal recollections of some of those who helped to found it. As with any work written in recent years, the late Dr G R Y Radcliffe gave invaluable and detailed help.

The house is old, the Club comparatively new. Yet the house is new, as its modern buildings show, while the Club is old when compared to any other house at Westminster. The first plays a vital part in moulding the lives of those who spend five years within it, and the second allows them to keep in touch with the friends they then made and with others older and younger who share the same tradition. But Grants is not exclusive, and never forget that she is part of a far greater whole. It is as a tribute to the 400 years of the school’s life that this modest contribution is made, for it seems right that these matters should be recorded as we start our fifth hundred years of life

5

1986

F.D. Hornsby

It is over twenty five years since the original edition of this History of Grants and the Old Grantite Club was first printed, and there has for some time been a need for a new edition, to bring the story up to date.

The task of editing this new edition, and of chronicling the events of recent years, has been entrusted to Simon Mundy (GG 1968-1972), to whom we are indebted for an illuminating account which will, I feel sure, be read with great interest by all who are associated with the House.

The Club is most grateful to those Old Grantites who responded generously to an appeal for funds to meet the printing costs. This has allowed the Club to distribute copies to all Old Grantites whose addresses are known, and also to provide a sufficient stock of copies for present and future Grantites.

Since 1959 many and far reaching changes have taken place within the House, as Simon Mundy makes clear. But to outward appearances, Grants remains unchanged, as familiar today as it has been to past Grantites over the generations. Unchanged also are the close links which exist between the House and the Old Grantite Club. Long may this continue.

6

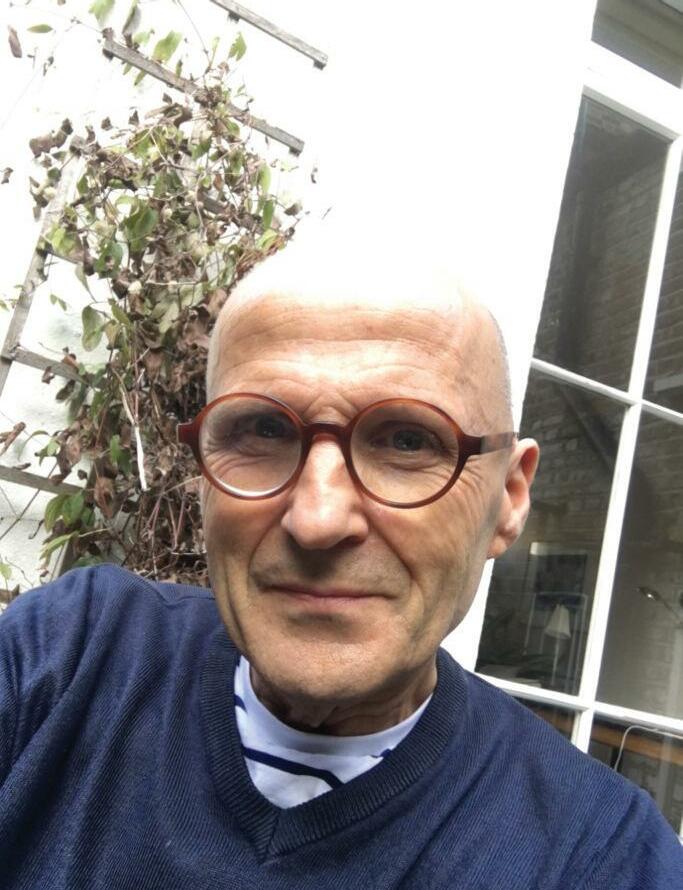

Rt. Hon. Dominic Grieve KC

House histories, like school histories have a risk of being staid. Too often they end up as a somewhat repetitive chronicle of selectively remembered achievements and amusements with the downsides glossed out. But the reader of this volume need not fear this. This chronicle of Grants in a period of immense change is vivid and at times rather startling. As the product of the first five years of David Hepburne-Scott’s house mastership from 1969-74, I had expected the account of life under his successors as House Masters to be of a quieter and more organised community This was certainly the impression they seemed to want to convey when I met them. Yet if anything it comes across, at times, as more, albeit differently, anarchic from the Grants I experienced. I am also delighted to read that the arrival of girls has had a beneficial impact on conditions of life in the House without in any way undermining its identity. Indeed one of the most attractive aspects of this history seems to be that a place which, when I was there, saw itself as exceptional but was rather tribal and inward looking, sees itself both as exceptional and welcoming to others from outside. Survival as a boarding house accessed by many day pupils may explain this. The transformation brought about by being able to enter Grants through the front door rather than the basement another. That this should have turned the front steps into a social hub would make an interesting anthropological study.

There are inevitably some changes I regret to note. Seeing that Walking the Mantelpiece was a genuinely old tradition dating back well into the 19th century and possibly to the origins of the House, its abolition in 1993 on the back of “health and safety” concerns strikes me (as a lawyer who once specialised in this field) as rather absurd. My psychological and physical well -being felt under much greater threat from the “Lagging Test”, now mercifully gone along with lagging, than the excitement of this rite of passage.

But the success of a place such as Grants should not be measured just by historical continuity. As John Carleton said “it is strange that schools pride

7 2022

themselves on their antiquity when they can pride themselves on their eternal youth”. As a boy I used to go and read to the partially sighted Dr Lawrence Tanner, who had started as a boy Up Grants in 1900 and gone on to be a master at the school. He would have been as delighted to read of Grants today as a successful community as I have been.

8

HISTORIES AND MEMORIES

Grants from the beginning to 1959

Lawrence Tanner It is a remarkable fact, and so far as is known unparalleled at any other Public School, that a school boarding house should have borne the same name and have been situated in almost the same place for over two hundred years. Yet such is the case with Grants.

It was in 1749 that Mrs Margaret Grant (Mother Grant 1) became the tenant of a house in Little Dean’s Yard which stood on the site of the old Bursary The House had previously been known as Ludfords, and the poet Cowper had either just left or was still a senior boy in the House when Mrs Grant became its ‘Dame’. She was the widow of a Mr John Grant who had died in Great Smith Street in 1747 where, according to the General Advertiser, he “had kept a boarding school (but probably a boarding house is meant) for many years”. Who the Grants were or where they came from is unknown. The name suggests Scotland, and that they were of a good family may be deduced from the fact that their descendants possessed a large ‘conversation’ picture painted by Highmore about 1730-40 showing the whole family suitably posed in a landscape setting

In 1765 Mrs Grant moved across Yard to the large house which stood on the site of the present Grants. Meanwhile the eldest son, Richard, had grown up. From Westminster (which he entered at the tender age of six and left as Captain of the School) he had been elected to Christ Church, and in 1764, as the Rev. Richard Grant, he returned to Westminster to become an Usher at the School. On his mother ’s death in 1787 he and his wife (Mother Grant II) took over Grants. They lived Up Grants until 1813, and their reign saw the pulling down of the old house and the building of the present Grants in 1789 or thereabouts. Among their boarders were a future Prime Minister (Lord John Russell), a future Archbishop of Canterbury (Charles Longley}, and the 6th Earl of Albemarle who gives, in his Fifty Years of My Life, a vivid account of the

9

House in his time, and lived to be the last officer survivor of the Battle of Waterloo.

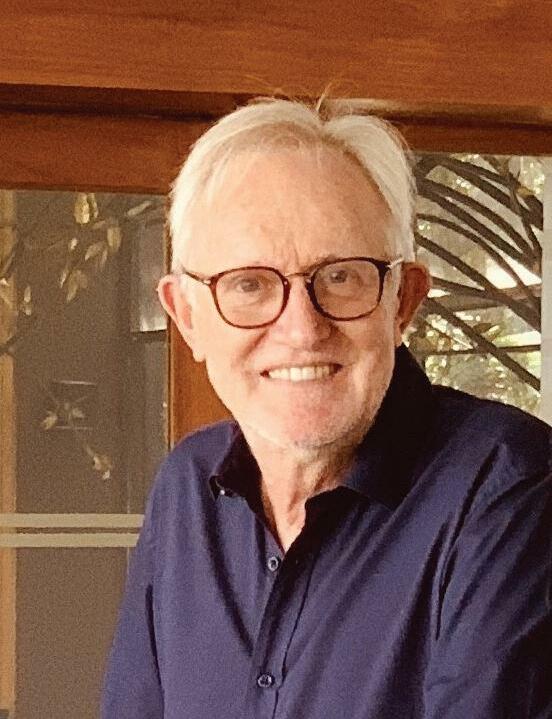

In 1813 the Rev Richard Grant retired to the country vicarage of Stansted Mountfichet in Essex, where he is buried and where there is a tablet in the Church setting out his many virtues. On his retirement he handed Grants over to his son, Richard Grant, and his young bride (Mother Grant III). One would like to know more about this Mother Grant. In 1950 the writer of these notes was able to trace a very charming pastel portrait of her as a young and beautiful woman. This portrait, together with some miniatures of the Grants, were purchased from the owner by the Old Grantite Club. They were handed over to the Master of Grants at the Jubilee Dinner of the Club in 1951 and the portrait now once again, after a hundred years or so, hangs Up Grants. Richard Grant died in 1837 and shortly afterwards his widow left the House and was succeeded by Mother Jones.

The House ceased to be a Dame’s house in 1847 when the Rev. James Marshall became the first House Master. About the same time the Rev. Stephen Rigaud became the Master of the adjoining House. But while Rigauds adopted the name of its new Master, Grants continued to be known both then and for the future by its historic name and thus has preserved the memory of the three Mother Grants who were its Dames for almost a hundred years.

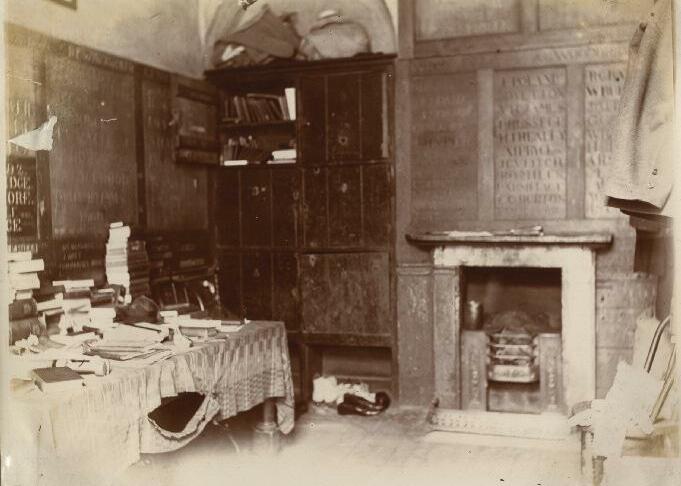

It was in Marshall’s time that the senior boys began to use the rooms know as ‘Chiswicks’ as studies. These rooms which adjoined the old Dining Hall in the Yard at the back of Grants had been originally used as sick rooms, and in their name preserved the only memory of a time when the whole School used to adjourn to the old College House at Chiswick in times of plague and during the summer months. It was, and is, a word peculiar to Grants, just as the custom of making new boarders ‘walk the mantelpiece’ in Hall is a distinctive Grantite custom. Life Up Grants under Mr Marshall has been vividly sketched by the late Captain Francis Markham in his “Recollections of a Town Boy at Westminster”.

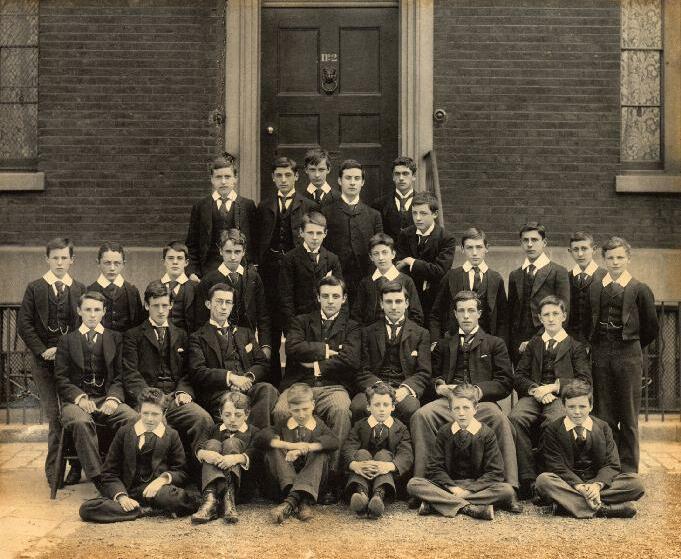

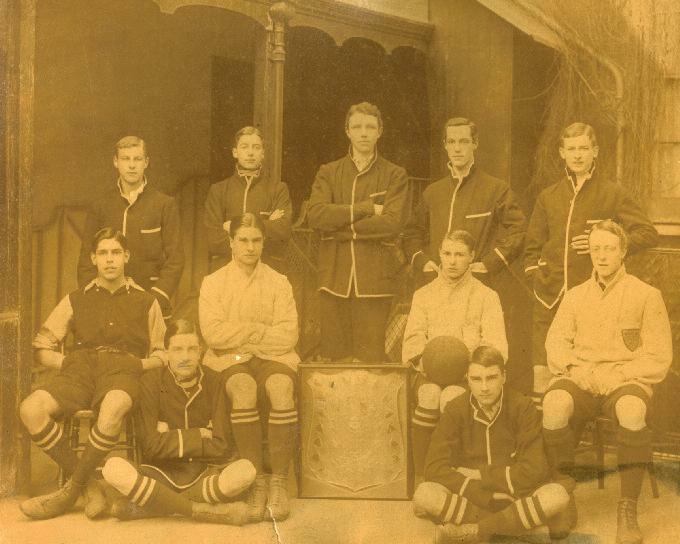

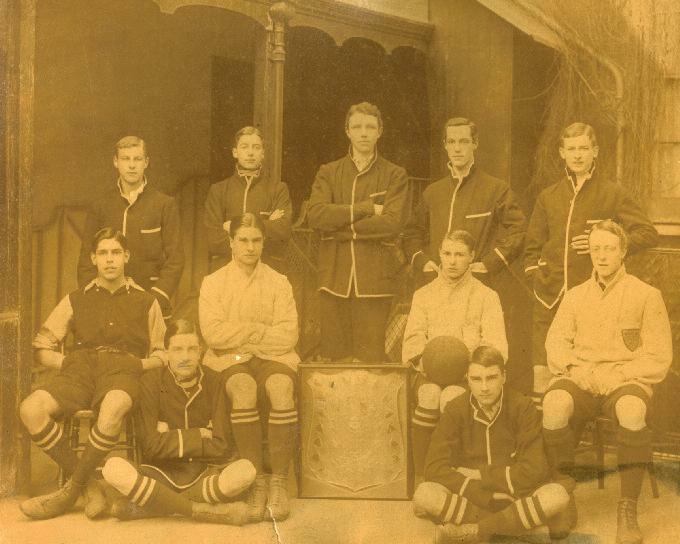

In 1868 Marshall was succeeded by the Rev. Charles Alfred Jones. It was during his time in 1878 that House colours were adopted in the School and the familiar chocolate and blue became the colours of Grants In 1884 appeared the first number of the Grantite Review which may claim, therefore, to be the

1 0

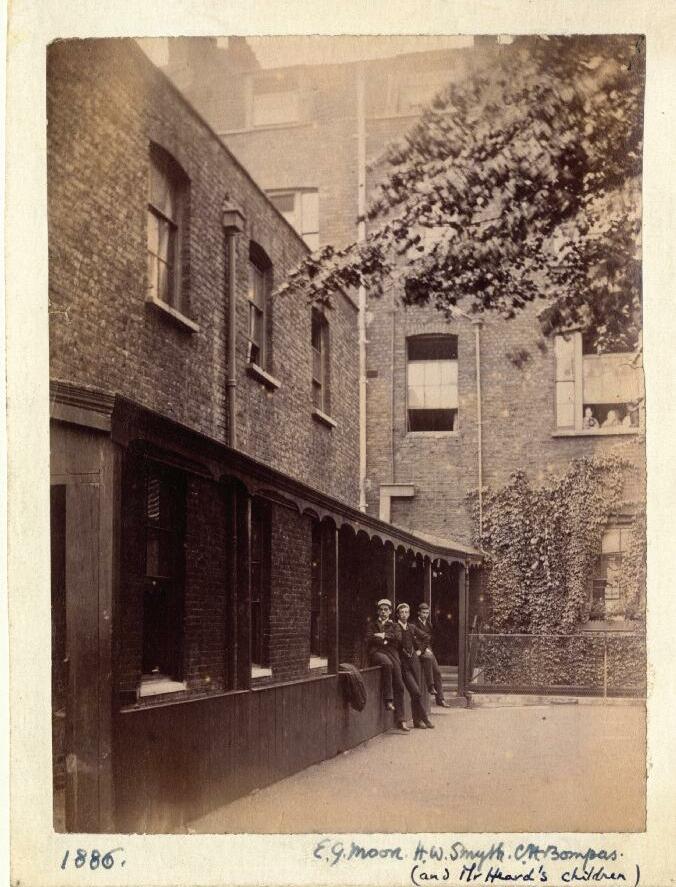

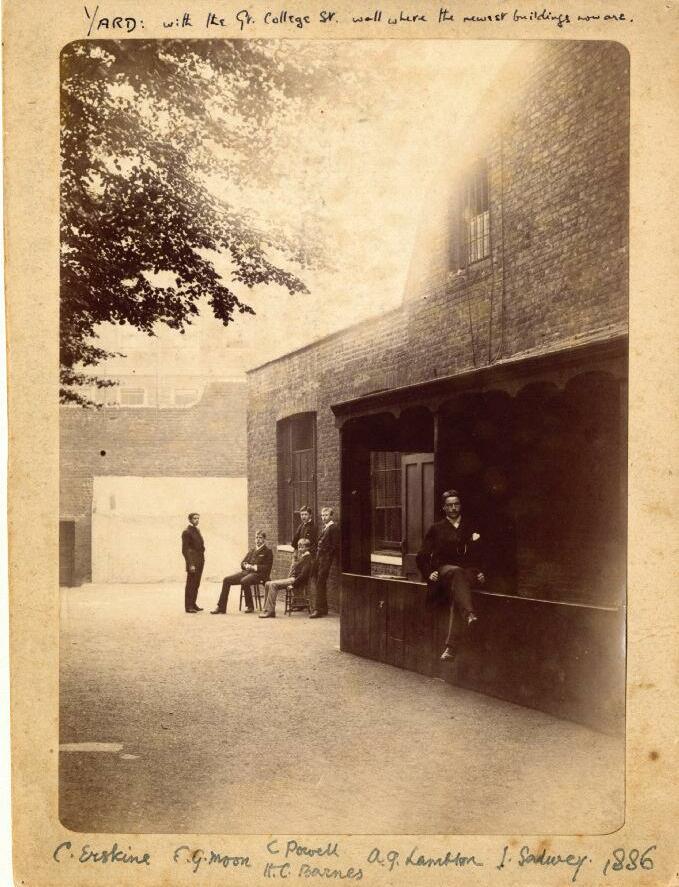

oldest House magazine in the School or perhaps in any Public School. When Jones retired in 1885 he was succeeded by the Rev. William Heard, and shortly afterwards an alteration took place in the exterior appearance of the House

Up to 1885 all the houses in Little Dean’s Yard had had the old up-and-down steps to the front doors. This was the main entrance to Grants and Rigauds, both for the House Masters and for the boys.

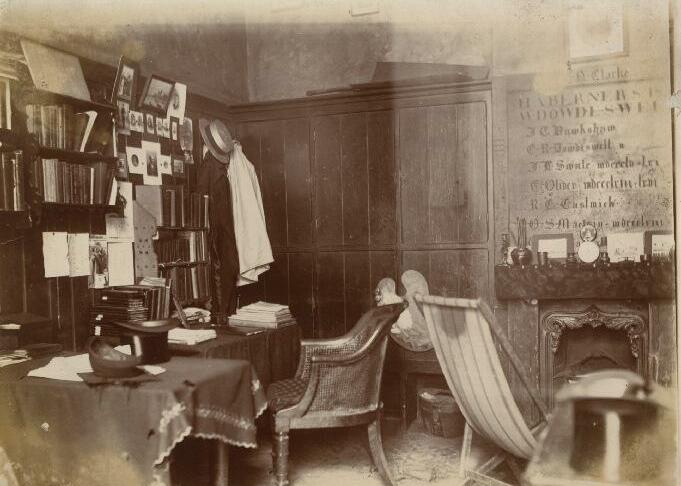

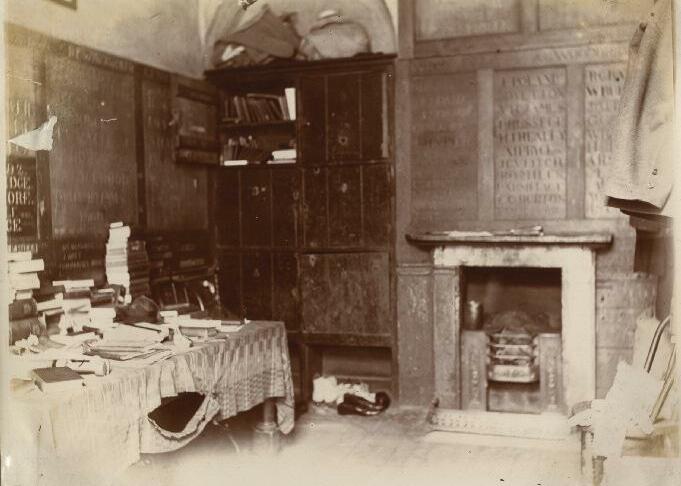

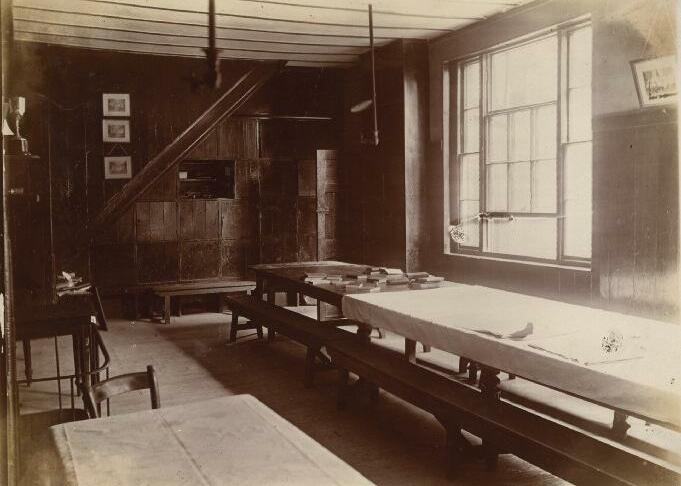

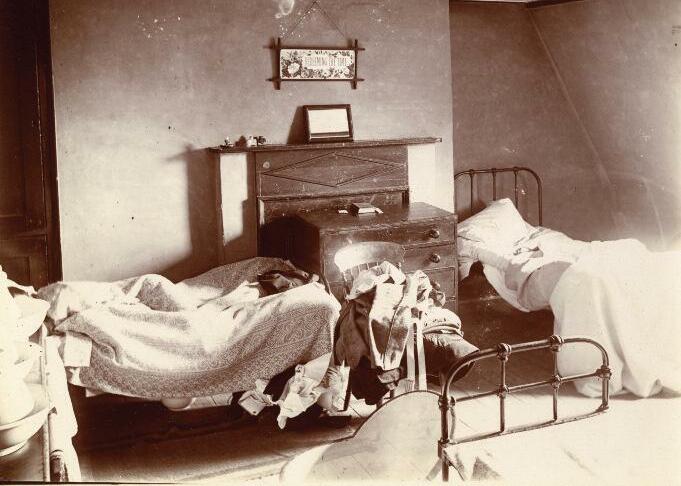

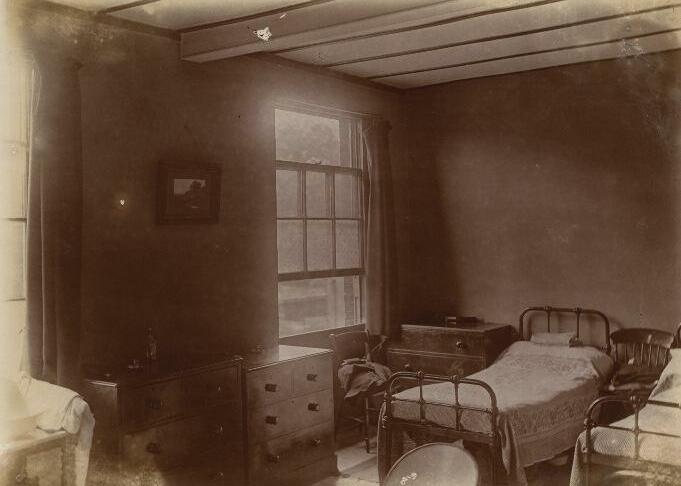

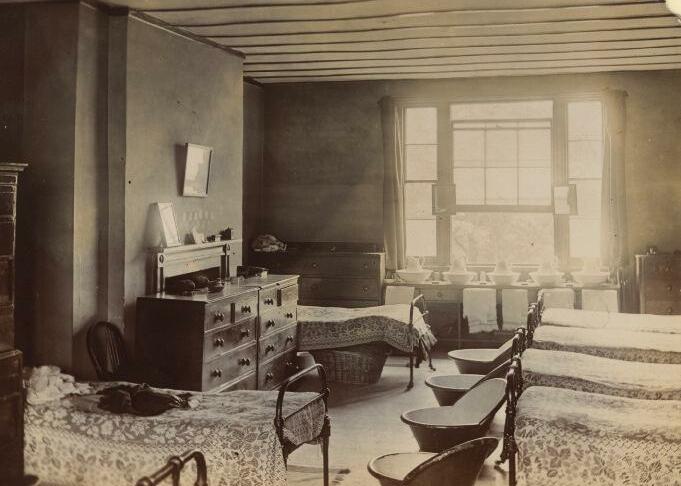

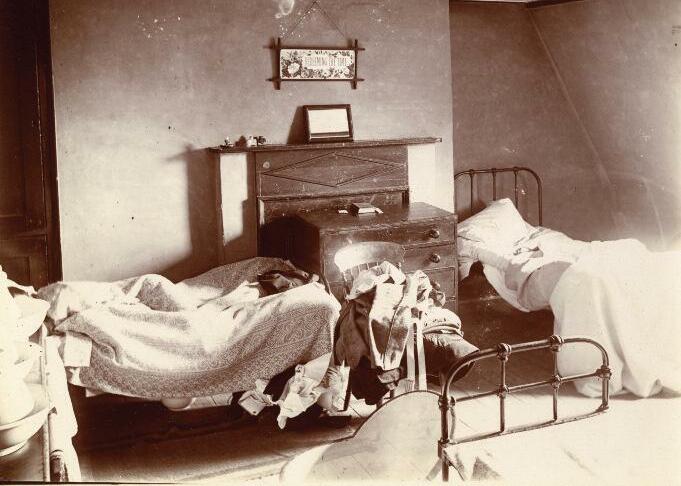

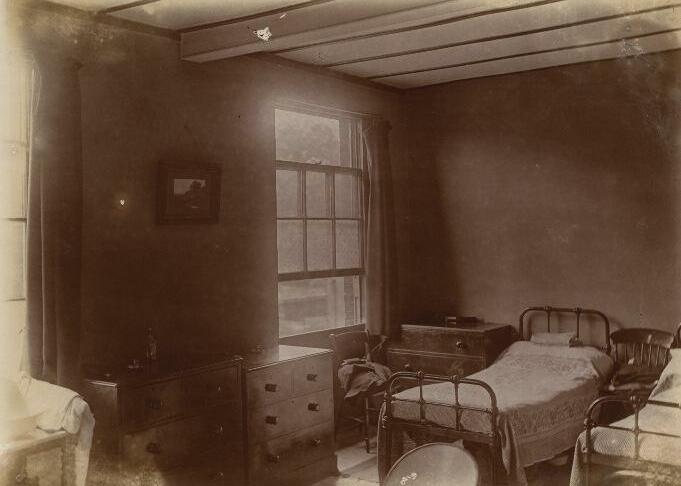

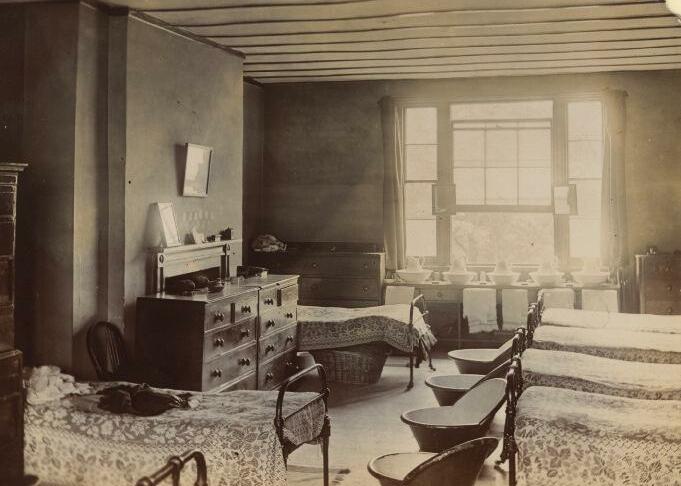

In 1885 a new entrance was made through the basement of Grants for the boys and the front door steps assumed their present appearance. Mr. Heard was appointed Head Master of Fettes in 1890 and Mr. Ralph Tanner was appointed House Master in his place. At that time Grants still retained much of its primitive simplicity. There were no bathrooms – senior Old Grantites will remember the little tin hip-baths, which were placed by each bed in the dormitories – and there was no electric light The passages, Chiswicks and Hall were lit by gas, but the boarders went to bed by such light as could be induced to shine from the little half-hour candles – ‘tollies’ – in their round brass candlesticks which had been used by generations of former Grantites. Other arrangements were equally primitive, but gradually some improvements were made and the more obvious defects removed.

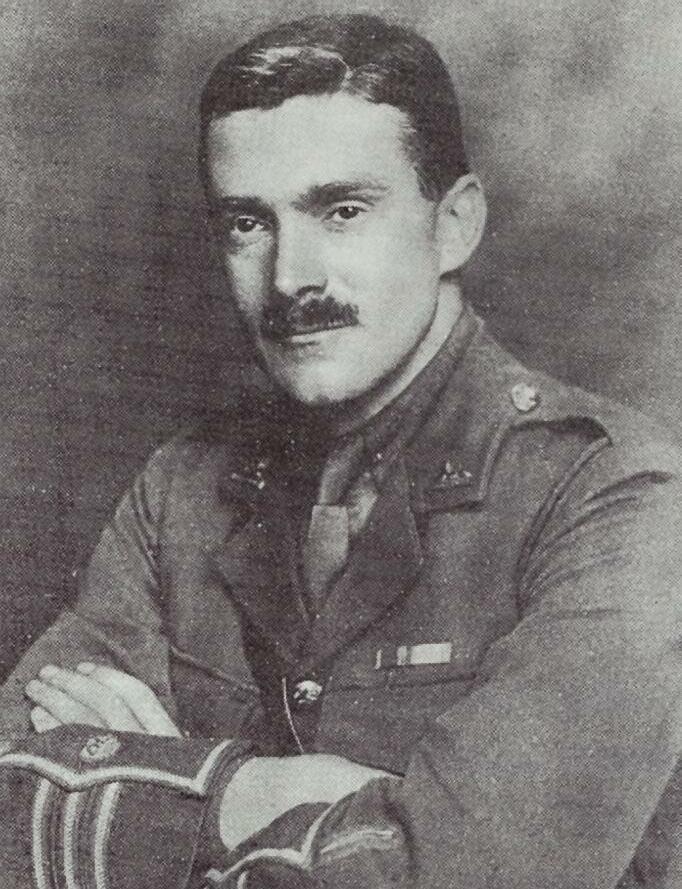

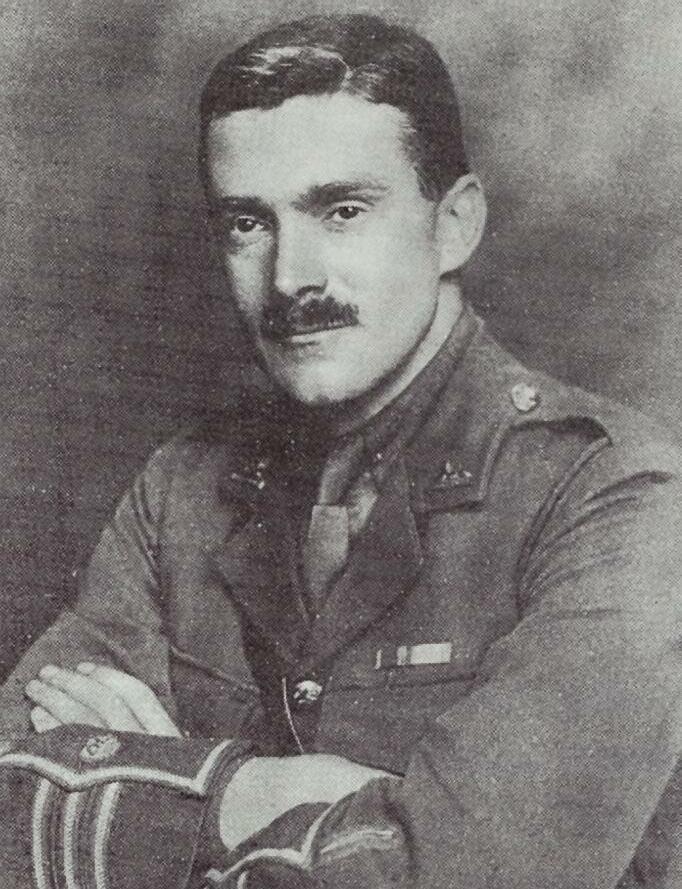

The 1914 War took a grievous toll of Old Grantites, but one Old Grantite, Colonel W. Martin-Leake, gained an almost unique distinction by being awarded a clasp to the Victoria Cross which he had already won in the South African War. He was the third Old Grantite to win a Victoria Cross; the others being Cornet W G H Bankes who was awarded a posthumous VC for gallantry at Lucknow in 1858, and Captain (later Major-General Sir) Nevill Smyth for gallantry at Omdurman in 1898.

In 1919 Mr. Tanner retired. A much loved House Master, Old Westminsters and Grantites subscribed for his portrait to be painted by Mr. Briton Riviere and a replica of the portrait now hangs in the Hall of Grants. Under his successor, Major Donald Shaw DSO, the old Hall was pulled down in 1921 and a new Hall made out of the old Chiswicks. At the same time a new building was erected at the end of the Yard with new Chiswicks, changing rooms, etc. Major Shaw died in 1925 and was succeeded by Mr. A.T. Willett (OW) in whose time much was done to improve the amenities of Grants In 1935 he was succeeded by Mr. T.M. Murray-Rust.

1 1

In 1939, War saw Grants evacuated to Lancing where they were at Lancing College Farm. The fall of France necessitated a second evacuation, this time to Exeter where the House took up residence in Mardon Hall In the autumn of that year the School moved to the borders of Herefordshire and Worcestershire and the House took up residence at Fernie Bank, a house near Whitbourne, where a number of the boys were billeted out in surrounding farms and houses. Fortunately, Grants itself escaped damage from bombing, and for a time in the later years of the War it housed the new Under School under the Head Mastership of Mr. Willett. When in Play Term 1945 Grants returned to Westminster there was no boy then in the House who had been up Grants before the War. But the traditions of the House had held fast in exile and it was with undiminished prestige and vigour that the House returned to new life and interests When the House was fully re-established in its ancient home, Mr. Murray-Rust retired and was succeeded by Mr. J.M. Wilson, under whose leadership the Hall and the adjoining buildings at the back of Grants were rebuilt. These new and greatly improved buildings were completed in 1955 and with them a new chapter in the long history of the House was opened.

1 2

Grants in the Nineteenth Century

Lawrence Tanner

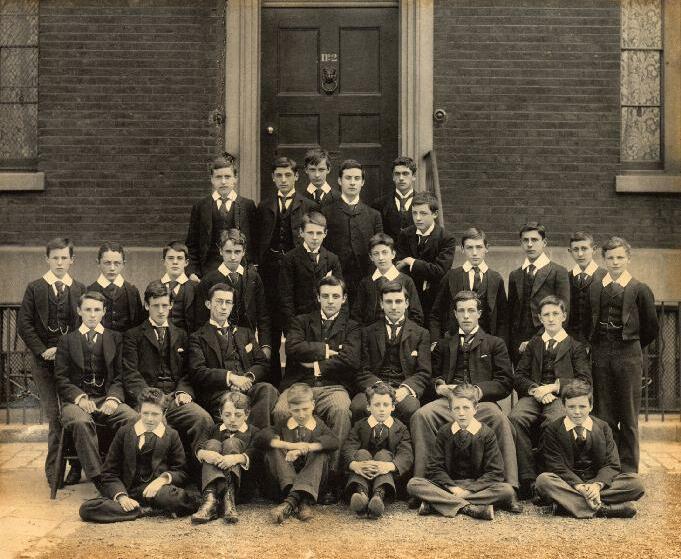

The following two accounts, preserved in the School Archives, give a fascinating picture of life in a boarding House in the middle years of the last century.

The first, by the Rev H. D. Nicholson, was delivered as a speech to a gathering at the Café Royal on March 20th, 1912 and was reprinted as a pamphlet, part of which is reproduced here. The Rev. Nicholson was up Grants from 1842-45.

There was then no resident master at Grants; but the Rev. Hugh Hodgson had a little room on the right of the door for a study Here he had Prayers every night. The house was under the charge of a Lady Matron – Mother Jones ... She was very kind but kept firm discipline, in which she was well supported by the older boys. She had rooms on the left of the front door, and another at the foot of the stairs where she sat in state every Saturday morning to pay us all our weekly allowances.

The rest of the staff consisted of a housekeeper – Old Mother Kelly – a manof-all-work, and two maids. Mother Kelly was the fattest woman I think I ever saw, though old Mother Shotten, who kept the tuck shop, was not far behind ... Her great function was to watch the Friday night washing of all boys under a certain age, previous to their Saturday outing We were stripped to the waist, stood in a pail of hot water, and well scrubbed by the two maids. Another part of the maids’ work was to go out in the evening, after lockers, to fetch beer from a public house which, strange to say, was allowed... The feeding up Grants was very good:

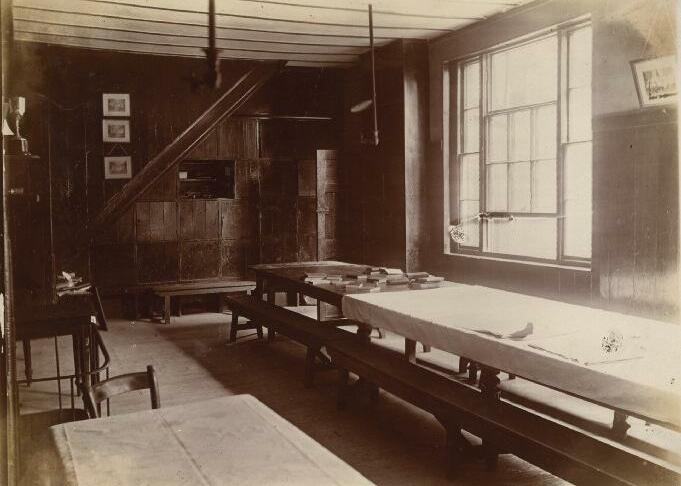

Breakfast: New bread and butter, ad lib. In winter we could make toast, three rounds of bread at the same time, on a long toasting fork reaching over a huge fire. Of course, we were at liberty to add the contents of ‘hampers’ from home ... There were no meals in College Hall, except dinner, until Liddell’s time.

Dinner: The best joints and vegetables; whether there was ever pudding I do not remember.

1 3

Supper: The cold joints from dinner. The Sixth Form boys never joined this meal, but had tea and tuck in their bedrooms.

The second, fuller, description was written by Arthur Southey and dated 'Teignmouth, 18th March 1911’. It has remained in manuscript and has not been published before.

It was in the summer of 1847 that I made my first acquaintance of Grants Boarding House at Westminster. I was only a half-boarder at first, till the end of the summer term. There was a Mrs. Jones who ran the house but she was never seen, except at dinner time at 2 o’clock when she always appeared in black satin. The chief occurrence in the term was the Eton and Westminster Boat Race This caused a good deal of excitement as we had beaten Eton the year before; however Eton returned the compliment this year and beat us handsomely. I went to the race and went after to a supper Up Grants which Mr. Marshall, who had taken the house off Mother Jones’s hands, gave us. Marshall was very kind and wanted to put me up, that I might not have to walk the two miles home through the streets at night, but I told him I would rather go home as I was afraid my people would be uneasy about me.

After the summer holidays were over, I went back Up Grants as a full boarder. I arrived late in the afternoon but there were no signs of any boys about the place. I finally made my way to the hall about 8 o’clock, where there was tea laid out for twelve boys, superintended by a stout matron whose name I cannot recall. I asked her where the other boys were and she said they won’t turn up till the last moment at 10 o’clock. She then went into business with me, undertaking to get me a cup and saucer and plate, and a brown pitcher and white basin for my bedroom (for a consideration – for we had to buy all these necessary articles in those days).

I found myself located with four other boys in a good size room. Furniture: five beds, each with a bureau by its side. These beds turned up when not in use, which was a convenience and gave more room but decidedly inconvenient, as I subsequently discovered, when a too playful companion would suddenly turn it up, thereby disturbing the inmate’s repose The result of this manoeuvre was to send the sleeper ’s feet right over his head. Just as he

1 4

thought his back would be broken he generally managed to slither out on to the floor. Yes, I certainly found my new friends were occasionally rather too playful As I was the newest comer, and the smallest, I had to undertake the office of fag to the room. The duties were not onerous, being chiefly to keep all the pitchers supplied with water.

There was a new matron in charge of the house who succeeded Mrs. Jones – Mrs. Crowther was her name, generally called Mother Crowther. She was very kind to us and well liked by the boys. Including some new boys, there were only fifteen of us in the house, as there were no sixth form boys just then. We had our own way and did pretty much what we liked. Most of us lived in the dining hall, which opened on the back yard, and another party of us lived in a room at the top of the house looking out on the yard. In order that we might have quicker communication with our friends aloft, some bright individual arranged to fasten a stout cord to the window above and the hall door below. Another cord, with a good size ring on it, slid up and down with anything that wanted being sent below. This machinery answered very well and was a source of great amusement to us for some days. At last, when an extra heavy load was coming down (it included, amongst other things, a heavy lexicon and a candlestick with the candle lighted), the string broke and the whole cargo came down just in front of the window where the Master of the House was sitting in his study. He naturally objected to the chance of his window being broken and put a stop to the proceedings for ever.

One day there was a window pane broken in our room, with a large round hole in it. As there was a high wind blowing this made the room very draughty. To obviate this inconvenience we made a raid on all the dirty linen in the room and stuffed up the hole. The result was that by the morning the clothes had all blown away into the next garden, with a fine row of trees belonging to the 2nd Master, Mr. Weare. There was a fine show of shirts, etc., hanging on the trees. I think they were all restored at last, but it must have taken both trouble and time to get them down from the tops of the trees, where they were certainly not ornamental.

In the yard, next to the hall, there were three small rooms which were called Inner Chiswick, Middle Chiswick and Outer Chiswick The name came from a house belonging to the school at Chiswick where boys that were ill used

1 5

formerly to be sent for a change of air. On half school days we were always locked up in the boarding houses for two hours in the afternoon. We were supposed to do some work but we generally got into mischief One afternoon we made a dummy man, filling a suit of clothes with dirty linen etc., and fitted up the life-size figure with a mask and a hat. When it was finished it was hung up by an old rope outside the window. I went into the yard and was looking at it when the rope broke and the dummy, throwing out its arms in the most natural and pathetic manner, fell into the area, after pausing for a few seconds on the top of the Master ’s study window. The servants rushed into the area but were afraid to touch it, saying “he’s broken his leg” which was curled up under him in a rather curious fashion. The horrified master of the house rushed out, saying “who threw him out, who threw him out?” The horror was soon over, for the boys who had made the dummy soon hauled up the remains from the midst of the servants and had, I suppose, to do a pretty stiff imposition for their work.

At this time I lived with five other boys in Middle Chiswick. Three other boys occupied Inner Chiswick and Outer Chiswick was still unfurnished. The Chiswicks were always at war with the Hallites and a perpetual goodhumoured sort of fight, chiefly wrestling, went on most evenings. I hardly ever went to bed without my shirt being nearly torn off my back. We had tea at 8 o’clock, Prayers at 9 and were all in bed by 10.30.

About this time there was a rage for miniature theatres with paste-board figures in front, while the proprietor read out the play behind A new boy was persuaded to give a performance during lockers one afternoon. It was to be a grand affair and Mother Crowther was formally invited. In order to mollify the audience the advocates of the performance distributed oranges among us. This did not, however, serve to keep the peace, but rather the reverse. For, finding the play dull, we began to pitch bits of orange peel over the curtain, on to the performers behind it. They very soon sent them back to us. Mother Crowther, on the first unmistakable signs of a riot, disappeared very quickly. Presently one of the audience sent a whole orange with an accurate aim, which speedily cleared away the whole miniature apparatus. The theatre people savagely tore down the curtain and charged us and the usual free fight followed.

1 6

The same confiding proprietor was afterwards persuaded to start another play, called Robert the Devil, and they even made him buy a good sized box of fireworks for it This took place in the evening in Middle Chiswick It didn’t take long for our audience, who had had enough of it, to bring it to a rapid conclusion by setting light to the combustibles in the box. The fireworks behaved splendidly but we didn’t see it much; the room only being about twelve feet by six we were obliged to throw ourselves face downwards on the floor while the sparks, Catherine wheels etc., flew over us. It was an exciting play but soon over.

As there was always war between the Chiswicks and the Hallites (and they were much more numerous than we were – some of them much bigger than any of us) we found it necessary to fortify our room in case there was a sudden raid As there was no lock to the door this was the way we did it We managed to capture the Hall poker – an enormous one with a large knob at the end. The poker we made red hot and with it bored a hole through the floor just inside the door and dropped the poker down it. The big knob prevented the door from being opened from the outside. It was very effective, but I doubt if the Fire Insurance Co. would have approved of this risky mode of fortification.

One morning after breakfast I wandered casually Up School. There was a large and very heavy old oak chest, which was called the Loss Box, into which any stray books found lying about used to be put. That morning several of the Queen’s Scholars’ 3rd Election had pulled this box into the middle of School and proceeded to amuse themselves by packing it full of small boys One boy was already in when I arrived and another boy, Twiss, was invited to go in too. He shrank back from it. There was no escape and so I stepped forward. I saw there was a hole in one side of the chest. I went in and coiled myself over the first boy, with my mouth close to the hole, and the third boy, Twiss, was very unceremoniously bundled on top of me. The lid was then shut down and the QSS kept turning it over till they got it to the end of the School. They soon tired of this amusement. The oak chest was very heavy and not the less so for being crammed full of live boys. We were let out then. I had plenty of air except when that side of the box happened to be on the floor. We all jumped out as soon as possible and skedaddled down School with considerable alacrity Twiss went into College afterwards and it shows what a rough time the junior QSS had of

1 7

it in those days that when I met him many years after and reminded him of our wooden journey he had totally forgotten all about it.

We used to do a good deal of cooking in Chiswicks in those days, having coffee, etc. One enterprising cook one evening tried his hand at about 2lbs of beefsteak. The meat made such a noise frizzling that we all were quite alarmed at being discovered, what with the smell and the noise. The cooks found the steak was more than a match for them and they hastily took it off the fire. It was quite uneatable. One half was quite raw and the rest burnt to a cinder. It was taken into the yard and thrown over the wall into Great College Street, where probably some lucky dog disposed of it.

Some of us used to slip down to Hungerford Market and indulge in a preliminary breakfast of oysters, which did not in the least interfere with our appetites for the regular nine o’clock breakfast afterwards

On occasions when there was an early Play and no morning school we used to make up a scratch four from the house and go on the water before breakfast. On a fine morning this was very delightful. The river, which is now a desert, was full of sailing barges coming down from the upper Thames with cargoes of fruit, etc. After some time, during which I used to row in the second eight occasionally, when wanted as an extra oar, I became stroke of the Boat. She was a heavy cumbrous boat and so I managed to find two more oars and for the rest of the rowing season we rowed in the third eight (this was the only time we had three eights going). I was out of school for two or three days and another boy, called Lipscomb, took my oar When I appeared again one evening he was delighted, as he found the work rather hard, so he took the rudder and steered us. When we got to Pimlico he took us too near the shore and, citizen Thames making a great swell just then, we were filled with water and fairly swamped, the whole crew sitting up to their waists in the water. We had to haul the boat ashore and turn the water out of it and then we all adjourned to a nearby public house (I think it was called the William IV) and fortified ourselves with brandy and water to avoid taking cold. As we were too wet to go on we turned and rowed back to Westminster.

In the year 1852, at the time of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, I made up a scratch four of my own friends to go and see it This I was not able to do. Some of the senior Queen’s Scholars had made up an eight with some

1 8

Old Westminsters to see it too. As they were short of one oar they came and asked me to take it. I protested but it was of no use, for they knew I had two junior QSS in my boat, so they frankly said “if you will not come with us, we shall not allow the two juniors to row your boat”. There was no way out of it as the power of the senior over the junior QSS was very great. I found a boy named Banks, who was afterwards - poor fellow - killed in the Mutiny in India, to take my place and I rowed in the eight with the Seniors and the Old Westminsters. It was rather a rough cold day. Our boat shipped a good deal of water and we had, at one time, to go ashore and bale out. While this operation was going on I had the mortification to see my own pet four rowing along in splendid style to Kew. After the race was over we rowed to the Old Swan at Battersea, where the OWW in the crew gave us such a splendid lunch that we didn’t want much supper

At the time of the Westminster Play most of us were there. Those of us who were not had a free and easy time of it, all the masters, of course, being at the play. A Sixth Form Town Boy would sometimes give a tea to his favourites. Some of us would take advantage of the time and skip up town and go half price to the old Adelphi, taking care to be back in the boarding houses before the Westminster Play was over.

The number of boys at that time was very low; not much more than a hundred. The QSS took advantage of this and oppressed us Town Boys a good deal. At one play night there had been a good deal of ill feeling between the Scholars and the Town Boys But there were a good many Sixth Town boys and Upper Shell boys, of which I was one. The theatre was built in the dormitory in College. The tiers of seats came nearly to the ceiling. At the back of all was a wooden partition which reached to within two feet of the ceiling. This had a three inch board running along it and on this board a row of small boys were always posted standing. Two QSS with canes sat within reach of the ‘gods’, as they were called, to keep them in order and make them applaud at the proper times. This particular night we Town Boys heard that the ‘gods’, when they went into the dormitory, were to be flogged up between two rows of QSS armed with canes. The senior Town Boys determined to escort them through and so we all charged through the bar at the foot of the stairs The QS in charge of the bar, after vainly trying to keep us back, called to the policeman

1 9

on duty to help him. The policeman, however, was so puzzled at the civil war suddenly breaking out that he didn’t attempt to interfere and we escorted the ‘gods’ safely to their places The senior Town Boys then returned pretty furious and decided they would not allow any ‘gods’ to go up at all next night. This would have left an ugly gap where they were used to stand. I was even requested to go up and try to get the ‘gods’ down there and then. I went in, accordingly, but by that time the theatre was cram full and I saw at once it would be impossible to get them down without making a great disturbance in a public place, so I gave it up. The ‘gods’ themselves probably preferred, now they had firmly settled in their uncomfortable quarters, to stop and see the show and, as it was a tearing wet night, I thought I had better do the same. The Town Boys, being very savage, wanted to fight the QSS but that was impossible at the time of the play The next day a compromise was arranged, the QSS promising that the gods should not be molested on their way up if they were allowed to come.

The above are rough notes jotted down from memory.

2 0

Memories of a Matron 1958-1980

Joan Fenton

When I first came to Grants in January 1958 I think the new studies had been built about four years. I distinctly remember feeling absolutely lost for a few days as I never knew which floor I was on and which end of the building was which. Although there are quite a few photographs of Grants as it was, I found it rather difficult to imagine how it all looked and longed for someone to make a model showing the old stone baths, etc.

Grants single studies were still the envy of other Westminsters, but when the Queen and Prince Philip visited the House in the 1960s, the latter referred to the ‘studyites’ as troglodytes, as he thought them rather dark. Several days before the Royal visit, a great flurry of cleaning took place. The large bathroom was rapidly re-decorated in case H.R.H. should want to see the“japs,’ etc. Mrs. Wilson with the help of Major French, who was then House Tutor, supervised the polishing of Hall floor with a huge industrial polisher. Wilby (Clerk of Works) stamped in and out giving ‘advice and encouragement’. Even in those days security on Royal visits was strict. When the Royal party crossed from Grants to the Science Block, Great College Street was swarming with plain clothes policemen. In those days Grantites could use the door from Grants yard which gave access to Great College Street, but after a few strange visitors found they could come in and pick up this and that, it was kept locked and unfortunate Grantites had to go right round by Dean’s Yard. I never had the luck to apprehend one of those light-fingered visitors, but if they were challenged they usually said they were looking for the Deanery and got away. When the German girls, who used to clean and help with meals, were still in residence, two men must have followed them home one night and got into the House. I found them comfortably installed in the sick room beds. The House Master came and immediately evicted them. We were very amused to get a telephone call from Colonel Carruthers (the Bursar) to say that two men had been seen leaving the back door and had stolen a bottle of milk on the way out

In John Carleton’s day Abbey was still compulsory on Sunday mornings.

2 1

The procession of House Masters and their families leading the boys back through the cloisters was met by the Headmaster in Little Dean’s Yard. Parents and staff chatted for a while before repairing to their various Houses for coffee or sherry before lunch. Sunday lunch had to be collected from College Hall.

In 1958/59 Asian ‘flu’ was rampaging through the country. Westminster did not escape and the Sanatorium in College had to be opened and staffed. This was no easy job. A cook had to be engaged. One such person made delicious cakes and meringues but the boys would not eat them. She had been seen licking her fingers during cooking. These ‘flu’ epidemics were rather overwhelming. Several boys became very ill and had to be whisked over to the ‘San’. We had two Red Cross Sisters to help with the nursing in the House and we had to mark the doors of studies, containing invalids, with a chalk cross so they could keep track of the inmates Remarks were then made about the Plague and jokes about “bring out your dead“ abounded. Both Mrs. Wilson and I succumbed to the ‘bug’, but somehow things went on. The boys were most helpful in those days. A couple of them would materialise to help with meals and run messages. A general awareness of the problems of nursing so many boys was fostered by the House Master, which was a very great help. Rather sadly, I think this sense of awareness on the part of the boys gradually disappeared over the years and the Matron sometimes felt rather cut off from the affairs of the House. Since annual ‘flu’ innoculations were instigated I don’t think epidemics have been such an arduous business.

Rules were strict when I first arrived A way of escaping this rather rigorous existence was to have a couple of days rest in the sick-room. It was hard to winkle boys out when they had obviously recovered. As time went on and rules were relaxed fewer boys wanted to ‘opt out’. With increased freedom life became more exciting and most boys disliked missing what was going on. Towards the end of my stay it was difficult to get boys into the sickrooms and justify one’s existence. No sooner were they in than they wanted to be out! To be fair, I think the general health of the boys has much improved. In 1958 boys who came in at 13 had been born just after the war. I have often wondered if this had anything to do with the fact that they were more often ill. Smog may have had something to do with it Towards the end of my stay Up Grants there were very few cases of serious illness.

2 2

Over the years with the advent of new House Masters so many things were changed. Some changes were for the better. In the 1950s boys were not allowed up into the dormitories during the day ‘Shag’ consisted of a blazer and grey flannels. Electrical gadgets were unheard of. Later these increased so much that one could hardly move around without getting entangled with wires. Many more boys stayed in at weekends. Saturday night up Grants (SNUG) was revived, which proved to be fun for a while. When Denny Brock became House Master in the early 1960s he opened the roof garden. This was a mixed blessing, as boys being boys, there was an awful lot of noise directly over my flat. One end of term boys took their mattresses out and slept on the roof. Looking back, there wasn’t much sleep but a lot of giggling and to-ing and froing. Matron was not amused.

There used to be an Annexe to Grants and Rigauds in No 2 Barton Street under the excellent care of Mr. and Mrs. Craven. When Martin Rogers became House Master of Rigauds, he wanted the whole of No. 2 for Rigaudites. So part of the old ‘San’ in College was converted to dormitories for Grantites under the supervision of a Monitor. This area proved to be no-mans land and was a thorn in the side of the House Master. Quite a few complaints came from the inhabitants of Great College Street about the noise. Happily for all concerned, all Grantites are now under the one roof.

After John Wilson retired from Grants we gradually phased out the German girls. After they had gone, their accommodation was taken over for a time by House Tutors who lived in and were fed by the House Master ’s housekeeper. This plan worked rather well as the tutors took on more responsibility and understood the working of the House generally.

In the early days Hall was still run by Hall Monitors. They kept some sort of order besides being in charge of the dormitories. In this way one could spot future House Monitors.

I well remember an occasion soon after Denny Brock came when he decided that the dinner plates were horribly chipped and needed replacing. In the basement there was an area, open to the sky, that housed the dustbins and was known as the ’banana pit’. The House Master decided that the Monitors could get rid of some of their energy by smashing the old chipped plates against the walls of the pit. A wonderful time ensued.

2 3

The Billiard table was originally placed in Hall. Grantites may remember a beautiful clock which stood on a bracket near it. An unfortunate boy (not a Grantite) knocked it down with his cue It was smashed to pieces The other day I was asked by the School Librarian what had become of it. I think it went into the dustbin.

The boys Up Grants were always playing practical jokes and one day two of them dressed up in brown overalls and went in and out of various classrooms during school supposedly testing the radiators. Apparently they weren’t recognised.

Similarly I never discovered who it was who flew a pair of pyjama trousers marked J. Wilson from the top of the Abbey flagpole, but it created a lot of excitement at the time.

In the old days each boarding House was very much a citadel Other masters had to get permission to enter from the House Master. Now all that has gone, boys and masters come and go as they please. Dryden’s shares Grants Hall for lunch, and for a while Hall was taken over for breakfast and supper as well, when College Hall roof was being renovated. I suppose the old has to make way for the new, but part of the former charm of the House being a world of its own has gone too.

2 4

Grants 1986 - 2022

Simon Mundy

A history of a school boarding house is always a continuum. In the case of Grants, reputed to be the oldest secular boarding house for school children in England, that story has spread over at least 230 years. In the years since the editors finished the previous edition of this book, though, Grants probably has gone through greater changes to its society, if not to its fabric, than at any time in the previous two centuries. It is a radically different place, as is Westminster School itself, and the relationships formed within it – of staff to students (no longer pupils), of young people (no longer children) to each other and to the use of the space – have shifted to the extent that Grants in the early twentyfirst century is almost as changed for someone who was there in the 1950s as a baronial castle turned into a therapy centre.

Each intake of staff and students has nudged the narrative forward, sometimes incrementally, sometimes with a massive shift. The biggest of these was the introduction of girls into the House, first on a daily basis and then as boarders, which involved a wholesale reconfiguring of the physical space. Girls had first started appearing in the sixth form and above years of Westminster ’s school life in the early 1970s and gradually the proportions had increased but Grants remained one of the last bastions of male exclusivitythe Dean’s Yard equivalent of the MCC.

First, though, a glance back at the 1970s, to the lighter side of life Up Grants and a sense of how the House guarded its tradition of being the oldest of the ‘town boys’ houses – slightly aloof from the newer establishments, second only to next door College, and prepared to take on allcomers if it came to mayhem. Here is the account of the final match in one of the barmier inventions of school sports but, despite its irreverence in our rather straight-laced times, one surely ripe for twenty-first century revival. I refer, of course, to Knelging The Flune. The account is from Hugo Moss, who was Up Grants from 1975-79.

“The game was played in Dean’s Yard on the Green using the whole area as a pitch. There were two teams, goals, a referee with a trumpet or trombone

2 5

and someone following him around with an umbrella over his head. The teams carried tennis racquets and the ball, the flune, was a miniature rugby ball, the size of a souvenir ball The ball was passed around the pitch I guess like Lacrosse until a goal was scored. To complete the goal there was the equivalent of a conversion where the goal scorer had to flick the ball into a waste paper bin, called the grommet, placed at a distance equivalent to the player ’s height. The other quirky rules included the game not being able to start until a sparrow had flown east to west across the pitch. The final rule, often not shared with the opposing team until the end of the game, is that ‘Grants always wins’. This brings us to Grants vs Westminster Girls in the scorching summer of ’76. Some of the Grants boys were in fancy dress and had put up a strong team, though in one case slightly hampered by a french maid outfit. This particular pupil went on to be very well known in the entertainment industry When Lis Wilson, the first girl monitor at Westminster, scored a goal, it seemed the obvious thing to do was to carry her into Little Dean’s Yard and deposit her in the fountain. And so a new rule for ’76 was born that the goal scorer should be dunked in the fountain.

Unfortunately, though, when the aforementioned French Maid scored a goal, he decided against the dunking. After managing to escape free from his captors he fled out of Dean’s Yard into Sanctuary, pursued by half the school in a St.Trinians-esque scene. Pursued past tourists, he felt his only salvation was to run into the Abbey Bookshop and hide, which is where the chase ended.

Following the game, a huge water fight erupted around the school with buckets of water being launched out of upper windows at any passer by. This, I remember being on the same day as a parents’ evening. So the whole day went from a scene from Harry Potter, ending up as a scene from If. Our only punishment was Dr John Rae at Latin Prayers the next morning saying simply, ‘Sit down’, instead of his more usual and much mimicked, ‘Will you sit down please’ – and the banning of playing any future matches of Knelging!

Although, this may have been forgotten by now, as Doc John is no longer with us and the school has had several headmasters since then.“

Rather than write a history, this section about the years since the mid 1980s quotes the words of those who lived through them Up Grants: students and staff. The first

2 6

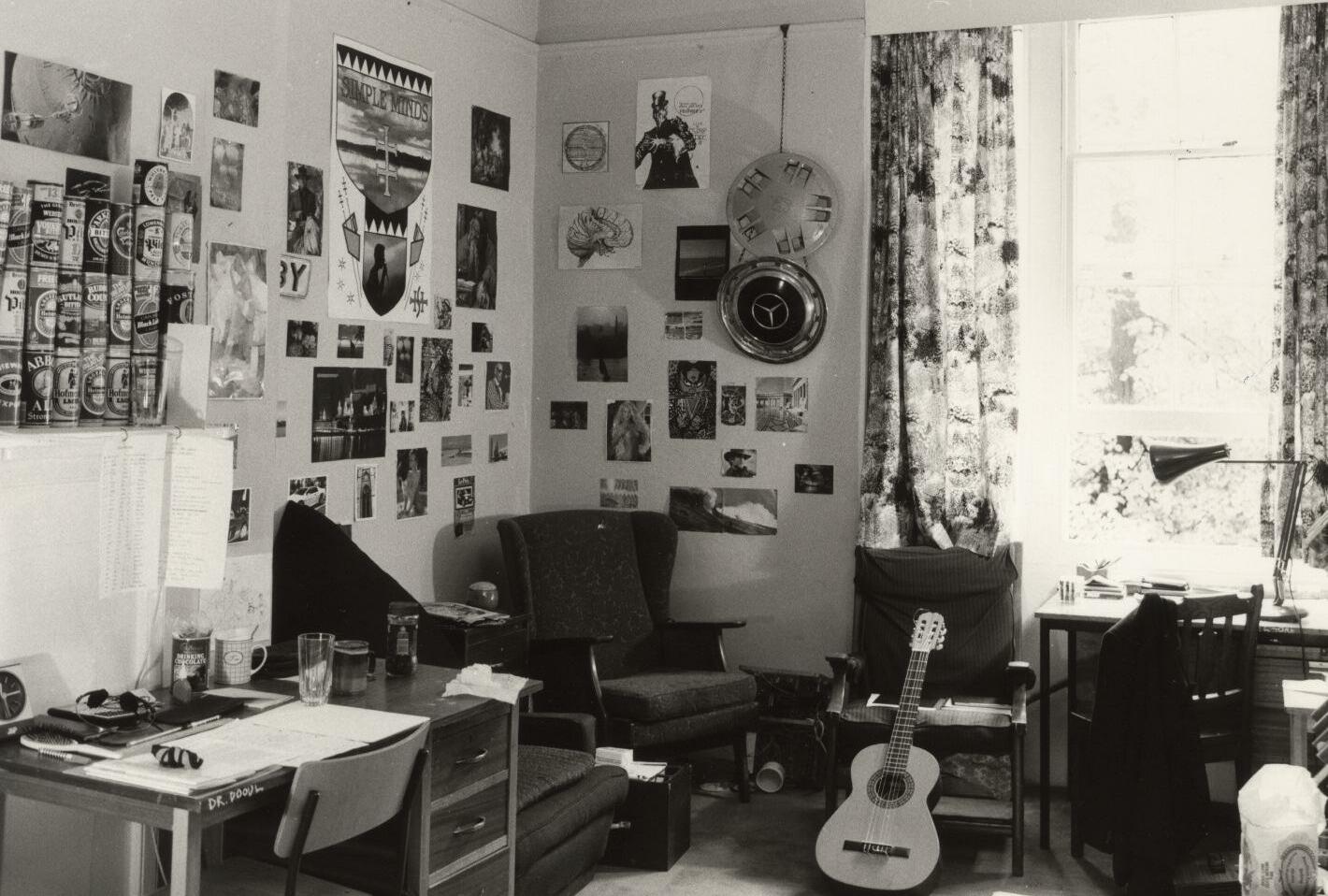

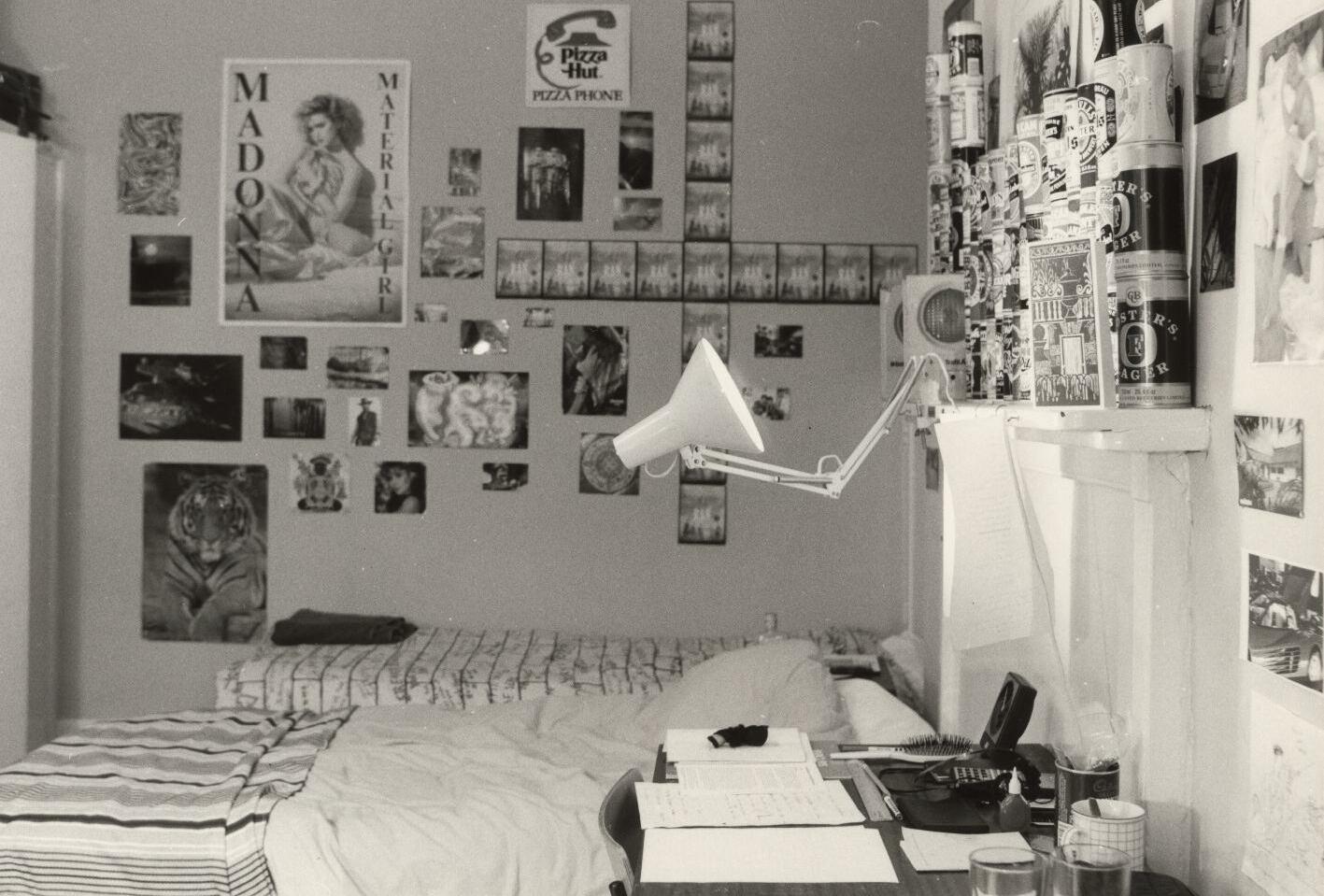

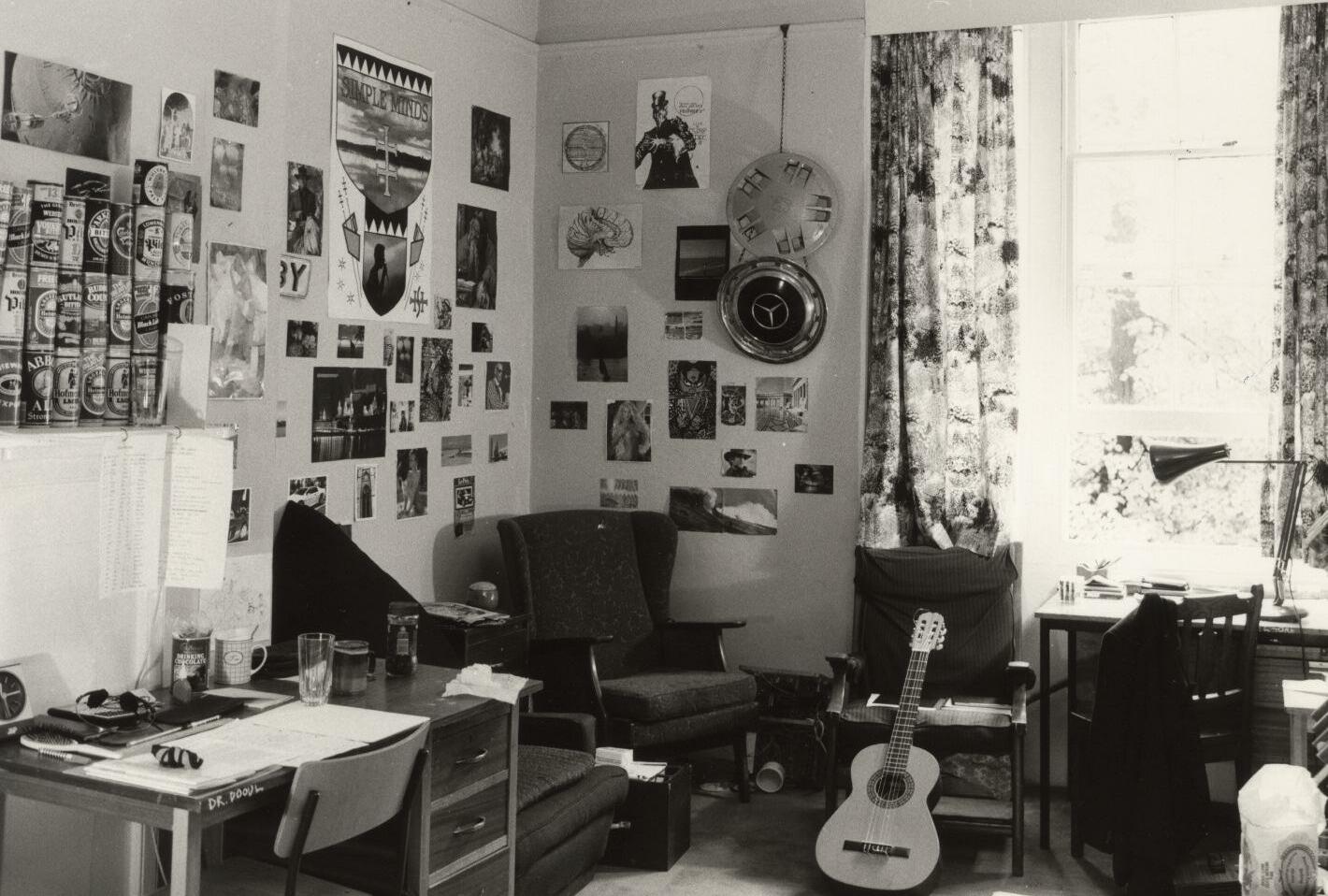

account is from Daniel Doulton.

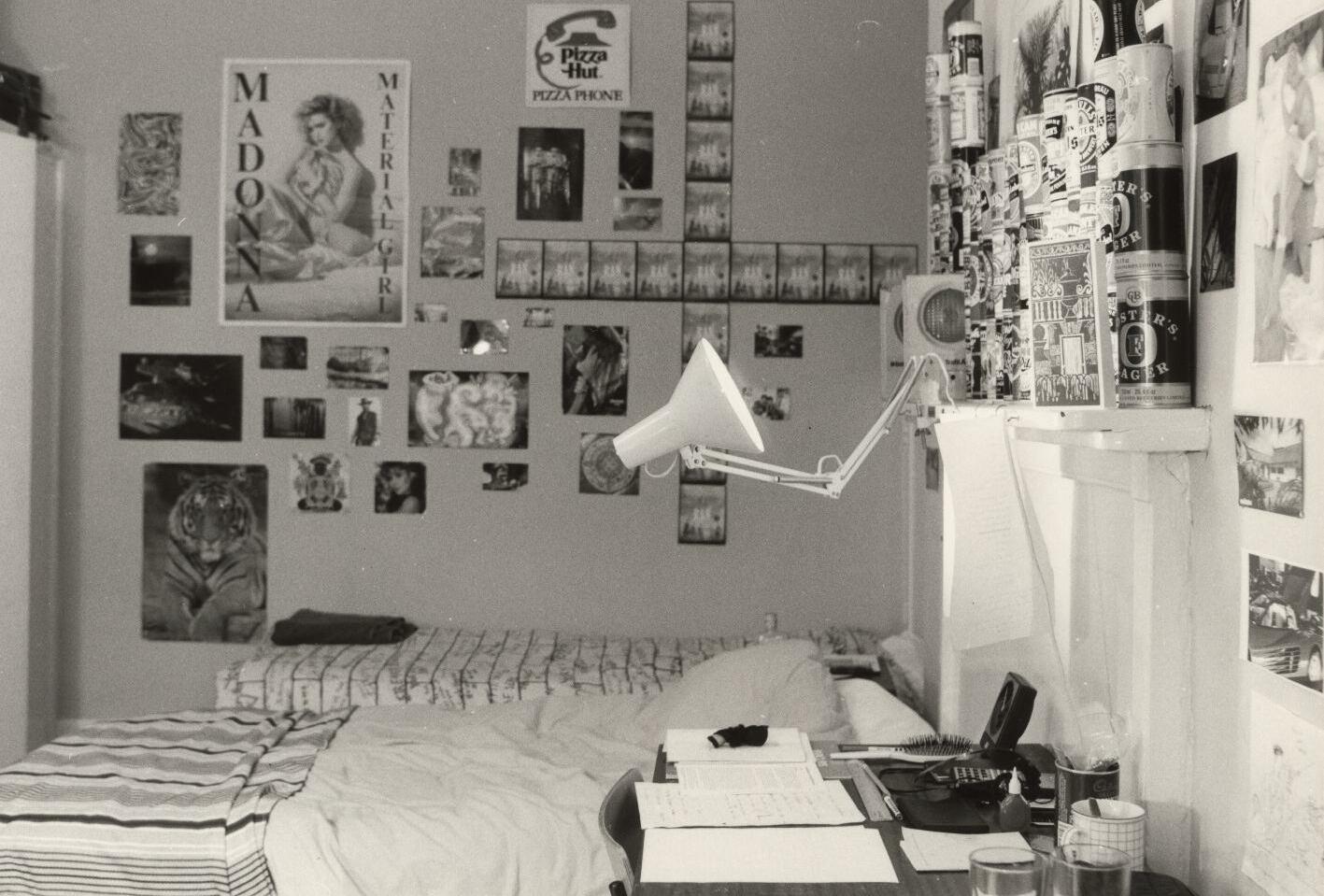

“I was Head of House during 1987-88 Chris Clarke was House Master and he took over from John Baxter who went on to become Head Master of Wells Cathedral School. Under Chris Clarke’s tenure things really changed in Grants – and in a good way. As a measure of Chris’s commitment to the cultural changes he so keenly wanted to effect, he had the House Master ’s apartment flipped from being on the ground floor with the grand entrance from Little Dean’s Yard, up to the top two floors of Grants where the pool room and two dorms were for the new boys and top floor studies for seniors. The previous preserves of the House Master ’s flat were now plush living areas for us Grantites – TV room overlooking yard, pool room, girls area, bar Chris making his study at the new entrance – some control over the gates was still needed! It was a big shift to be able to come into Grants through the real front door, rather than have to skulk through the basement, past the toilets [japs], showers and TV den room, Blanco’s lockers for day boys, which really changed the whole status of being a Grantite.

“Hanging out on the steps into Yard and being generally cool was now a thing. And this set the tone for everything Chris did, which changed the energy and nature of being in Grants. We were all – boys and girls – treated with a lot more dignity, kindness and support, as if we were a large family than the mob for which we’d gained a bit of a reputation. Previous generations had really pushed the limits from daring jibes at other staff, sneaking out at night, drinking and smoking all sorts of things, along with the rebellious fashion propelled by the punk, post-punk, goth and hip-hop waves. Under Chris, he made fashion cool and removed much of the taboo. When it came to errant behaviour, he would seek to talk the issue through, avoiding the immediate escalation and stopped many in their tracks. As Head of House, ‘busting’ smokers became more of a process than kicking down doors and rolling in the grenade of authority. In fact, we ran a ‘policy’ of exporting smokers (often visitors) to other locations which asked them to respect our request and test out others’ which seemingly worked wonders. I think Chris’s chats with offenders dropped in the seeds of concern and I don’t think anyone would want to challenge his kindness. That was perhaps too precious a commodity.

2 7

Compare this with the option of facing the wrath of Messrs Jones Parry, Cogan, or Harben.

“And lastly, girls They went from being a welcome stare to being more included members of Grants with status (yes, they were even made house monitors!) and a real voice. Again, taboos, barriers and misconceptions about having girls in school, let alone in Grants, were all lowered and improved. I’m sure this was as much Chris as it was Emily’s drive – she was after all a former pupil at Westminster. I must however defer to the girls to qualify their experience as I’m sure it was different to what we thought.

“So, out with the fruit fights during prep, smoking with mates in one of the many studies in the ‘new block’, throwing rotten fruit/water bombs/hangars/crap and hurling insults at rival houses (Rigauds in particular – there was an ongoing campaign), macho acts of daring (I once held the legs of a certain Torcia out of a high window so he could recover a snooker ball he ‘lost’ out the window) and midnight raids on dorms (in which I broke my hand – sorry Matron for lying that it was a door that did it…).

“Fashion: well, there was quite a shift during my time from what as a punk era (yes, some dudes did go Mohawk at weekends, even mullet style in the week), goths (massive black back-combed hair, winkle-pickers and drainpipes) to casuals, progressive rock to the explosive hip-hop wave which divided and oddly united the punk/goths and hip-hop crowds. Several defected and became baggy pant, cap bearing, VW badge wearing NYC crew. I’ll never forget sneaking off to the Windmill Club in Soho to one of the first hip-hop nights and being blown away by how different, cool and exciting this was. In stark contrast to seeing The Cult, The Cure, The Ramones, Fields of the Nephilim, Bauhaus… but just as edgy, exciting and alive. And a third choice to the Talking Heads, Talk Talk new wave genre. It presented a real cocktail of music, fashion and choice and I recall many people transiting between them and often oddly out of place. I certainly had my guilty pleasure of music buried across all genres, but of course, you’d pick which one to gang with when going out and choosing your mates.”

Chris Clarke himself saw his time this way:-

2 8

“When John Rae asked me to take over from John Baxter as House Master, I was surprised and very conflicted about accepting the post. We were living in a very pleasant flat in Dean’s Yard, and enjoying our life with all the attractions of London. I had been a tutor in a boarding house and was well aware of the commitment that was expected. However teaching the subject I did (Art) there was a sense that in such an academic school, I had to show the powers that be that I could do the job. Further, there was the accommodation for the House Master and his family; we thought as it stood, it was unworkable for us. Emily and I came up with a plan to improve this situation. The plan was accepted and it remains the way things are now. The House Master ’s flat was moved to the second and third floors, the study remained just inside the front door, and the boys and girls were able to come into the house through that front door rather than access through the basement Much happened during the next ten years 1986/96; happy memories, lasting friendships made and our two children arrived, adopted from Chile. Looking back now I am astonished by the lack of training and preparation. Had I not had the wonderful support of matrons (Daphne MacClaren and Belinda Toes) and experienced tutors (especially Andy Milne as resident House Tutor) I would have been overwhelmed.”

The Head of House duties after Daniel Doulton, during Chris Clarke’s time, fell to Christian Brent. His memories come as flashes represented in a series of lists gleaned from his friends of the time

“Here are the things I have managed to rustle up from my cohort. I am afraid it’s a bit stream of consciousness and not particularly structured but people are reaching back into the dim and distant.

Katie Taylor:

Yellow Timberland boots were the coolest, with floppy hair.

‘dub be good to me’ down the corridors.

The change from Mr. Baxter and the arrival of Mr. Clarke allowed us to use the front door and the floppy haired, yellow booted ones hung out on the front steps leading up to the front door. It was the epicentre of Yard. Grants only

2 9

had two girls in the year, a lot fewer than any other house. I believe that Grants was the last house to have girls. That was a massively overwhelming experience The ‘girls room’ next to the stairs meant that we watched the world go up and down the staircase. Sorry to do this from a girl’s perspective, but it is the only one I have.

Oh and smiling was illegal!

Belinda (new young matron) had an adorable grey cat. She always seemed very popular with the 5th Form.

Felicity Fallon:

Westminster, and Grants, was a pretty weird place for girls in 1988.

Jocelyn Horwood:

Did Chris Clarke ever work out what the mysterious red marks were in the corridors? Made by us playing cricket with leather balls...

Mark Braithwaite:

I had almost forgotten the corridor cricket. Also winkle-pickers

I remember a lot of drinking and smoking and very little homework. Fruit fights with orange softening techniques. Cricket in the yard (with occasional green apple googly in place of the tennis ball)

I also remember a lot of different tie “styles”. Also all the ridiculous crushes and rumours… my teenagers are so much more together – it is a bit embarrassing.

Christian Brent:

I think corridor cricket

Chewable floppy fringes

I have a very distinct memory of one of the Famous Five [Remove in 1986: Nick Burton, Daniel Jeffreys, Stellios Christodoulou, Patrick Dickey, Milo Twomey], having taken a collection in the Abbey, deliberately being the last to return his box so everyone could hear the buckles on his winkle-pickers

3 0

echoing around the nave. My 13 year old self thought it was about the coolest thing ever.

General Grants House 1985-1990

Definite outsider mentality, Grants against the world, Jimi Hendrix blasting out of studies, Chris Clarke opening the front of the house, and so the use of the main stairs,

Forcing people from other houses to enter via the basement “Other Stairs!”, Upon entering the TV room: “Phwoar, open the window, it f***ing stinks in here!”, Walking the Mantlepiece initiation along the corridor in Hall, Fingerless gloves for prep in freezing Hall in the winter, Best tea in the school: Mollie ruling the roost, Running around St. James’ Park at night for ‘training/punishment’, Boris (1985 Remove) a simply enormous bearded 18 year old!

Fashions – New Romantic to Floppy fringes to Flat top haircuts, Winkle-picker boots and skinny trousers, Doc Martin brogues, Black zip up polo neck sweater, Different coloured Converse boots, Embarrassing “Bum-fluff” moustaches”.

Nader Akle has contributed a full and brilliantly vivid account:-

“I was at Grants from 1986 to 1991, where I followed Christian Brent as Head of House and was then followed by my brother Ziad. A rather unusual circumstance for two brothers to succeed each other in consecutive years in that position in the same House, but I hope that Chris Clarke and the House benefited from it.

“I was always a Science rather than Arts student and both essays and prose were a terrible affliction for me. I have a stream of recollection. Walking the Mantelpiece was exclusively for boarders by 1986 (as far as I remember) while the “mantelpiece” was represented by a narrow, high shelf in Grants dining

3 1

room for just this purpose, a rite of passage on our first boarding night –somewhat anticlimactic but requiring team work and assistance for the shorter or mal co-ordinated amongst us – which was somewhat made up for (inadvertently!) a few weeks later when the tradition of “lagging” [a Westminster word for fagging] pretty much died out (was laid to rest) in Grants. A few fifth form boarders (including Tom Forsyth, Merlin Sinclair, Giuseppe Lipari and I), who were unfairly large, sober and forewarned (by a distinct lack of anything resembling stealth) rather too successfully battled out a late-night raid launched by a few die-hard and unsteady (liquid-courage, pillow and stick waving) Sixth form and Remove boys, who were beaten into ignoble and unsteady retreat before the House Master ’s loud outrage arrived.

“For a mild mannered and obviously kind man, Chris Clarke presented an impressive degree of ferocity when the occasion demanded A busy and unsympathetic morning at Matron (Matey’s) followed a few hours later for a few sombre sixth formers. The Remove were too busy and above such antics, according to Griffiths (then Head of House), Evans (Deputy) and Christodoulos (his room-mate), all of whom were largely tolerant of us new boys as they had fourth term and A level preparations to work hard on. We kept largely out of their way.

“There must have been something in the air in Grants from 1986 onwards that encouraged “nesting” among the housemaster and Tutors. The extremely personable couple of Chris Clarke and Emily Reid (apart from being a romance famous in the school that no-one ever mentioned) presented the house with baby Sophia-Jane (Sophie) and shortly thereafter Ignatius (Iggy) – who kept their parents, Belinda Toes (New Matey) and a few willing babysitting Grantites (Wine Gums go a long way!) busy. Nicoletta Simborowski took up knitting and kept under wraps to the last minute her romance with Daniel Gill (the female student body’s hands-down favourite). Anne Middleton and Michael Allwood found each other, not through maths but rather through music (go figure!), and Neighbours trumped EastEnders for some years (Kylie Minogue in shorts helped).

“For the Grantite boys, however, instincts tended to turn to Justice and Rigauds more often than not Over the years both seem to have deserved what we visited upon them: Grantite Justice. I do not think that I can or will relate

3 2

many details but the main thrust tended to be aimed at the pride and misbehaviour of their upper shell and sixth form who were ejected from their beds and locked out into the yard in whatever they were wearing (no shoes) late one cold frosty night (it may have also been snowing) for not looking after one of their own younger boys.

“Girls in Grants – Hmmmmm. Frankly the Grants girls were a pretty sensible (survival instincts!) and integrated bunch and there were always a disproportionately higher number of ‘visiting’ girls in Grants (and perhaps Busbys) than in the other houses – due to our charm and location (Grants was front and centre on the Yard while Busbys was ‘cool’ in an old-school way –think Gryffindor panelling, staircases and brass fixtures). The two houses’ boys were just more relaxed and easy to get on with. This did not preclude, however, the regular ejection of a few girls (usually self-deluded in that over-confident flirty teenage way some girls could be) from the back upstairs bathrooms where they only came to have a smoke and try to awe (bully) the fifth form and lower shell boys into parting with their sweets, crisps and (most importantly) loo-time (not a good idea).

“Issues around smoking were an ongoing battle at Westminster. The school is/was nothing if not pragmatic; both cosmopolitan and a reflection of professional society of the day. The Smoky Common Room knew full well that fire insurance, health advisories, politics etc. were not going to trump the habit of very many students and staff both in terms of nicotine as well as social practice Most institutions (professional, academic, public and private) clearly largely ran/run on tea (nowadays coffee), nicotine and biscuits; neither the students nor the staff nor the teaching alumni (die-hards!), were likely to be deterred or persuaded otherwise.

“Westminsters learned in their first days (weeks if you were slow and unlikely therefore to make it to the sixth form) that bells, league tables, fear of disciplinary punishments, screaming commands or demands are not the toolsin-trade of choice in the society they have entered. Even those of us who don’t get very far with Cicero, Socrates or Plato quickly came to understand (the subconscious is powerful) that the controls or motivations which guided and characterised daily life in the school (and Grants in particular ) had everything to do with pushing or enabling achievement (except when Neighbours, Star Trek

3 3

or Twin Peaks, season 1 were on TV). Integrity somehow seemed to be manifestly ingrained. This of course resulted in a ferociously competitive environment between curricular and extracurricular activities where academic achievement was an unspoken requisite (that’s what we were at school for BUT there was a time for more) at the same time as there was flair and passion brought to sport, music and drama by the staff and pupils that allowed the school (in a comfortable way – except when C.D. Riches was chasing you around the Serpentine at 6 in the morning) to punch consistently far above the weight that our numbers would suggest.

“I suppose we all remember a few teachers, staff and events that have lasting or profound effects on our lives and Westminster was full of these for many of us. The (now institutionalised in memory, I suppose) HepburneScott’s first lesson on how to handle suits, jackets, ties (at least 3 ways to tie a tie in under 3 minutes), and clips (trouser and sleeve for riding bicycles and laboratory work), that generations of Westminster boys will bless him for and remember in detail as he shockingly and nimbly jumped between basement physics lab benches, was the first to address us as gentlemen and with considerable flair commanded and engaged our attention on every subject.

“The Tim Francis first Latin lesson by a giant bear of a man who also doubled as a Registrar for new boys and explained what ‘Westminster Latin’ was and why it was relevant. Oboe lessons in the music centre (thank heaven I was the surplus third school oboist which the orchestra could largely live without ever knowing I existed), where I became adept at knowing when to show even greater ineptitude than I generally possessed as the music master walked past. The Grants kitchen and cleaning ladies somehow being Polly, Molly and Dolly: all as kind, comfortable and understanding as their names would suggest to constantly hungry boys (wolves), who never seemed to have enough toast or peanut butter. They rarely thought much of the out-of-house girls.

“Participating in the Greaze (putting elbows and shoulders to good use!) and coming off better than most (we were all almost winners’) but not quite sure as to how and why that tradition got so tied up in the school’s history, except that it was an excuse to publicly rough-house and exchange/exhibit a few bruises, bloody noses and even an occasional genuine limp as consolation

3 4

prizes for not winning a coin. The institutional pride in having Dr. Muffett (who set Cambridge board Chemistry A level papers) consistently blow something up in classroom practical demonstrations (sometimes with the help of an innocent shuffling of bottles on the bench – to date I check and recheck any components, tools or chemicals) – and even once causing himself and a seriously talented and recklessly brave pupil accomplice to have ringing ears for a few days along with a lab that required more than a little TLC. I believe that a term-long ban on Dr. Muffett accessing any chemicals followed.

“Forcibly developing city-boy survival instincts on the 159 bus and keeping track of the swimming station boys through the Central YMCA's wet changing rooms from the late 80s to early 90s – not a good idea to be losing anyone on the way to or from THAT pool. Proudly entering and seriously making a very amateur and pedestrian rendition of Swing Low Sweet Chariot – without a single Welshman – to the House Music contest that earned us kudos while it both protected our street credibility and allowed us to make the violin virtuosos work even harder to compensate for our lack of technique or flair.

“Learning to interact with people from all levels of society – from Bill the septuagenarian security night watchman in the Abbey Cloisters, who was sometimes ready to trade exploratory access to the late night Abbey for a listening ear to his experiences in the service and a bag of crisps he wasn't really allowed, to sparring at John Locke Lectures or debates with politicians (Edwina Currie gave as good as she got!) or explorers (Fiennes was a high point) or journalists (Ian Hislop still going at it), scientists, city professionals, etc. Reciting in Westminster Latin, sometimes even with a Welsh accent and daring anyone to notice.”

Alex Massey was Up Grants, from 1989-94 (Head of House 1993-94), so there while Nader and Ziad were Head of House.

“My memories of my time Up Grants was one of contrasts and juxtapositions. Some comic – the terrible food in College Hall surrounded by incredible history, architecture and art; some other-worldly – the calmness of mornings in Abbey followed immediately by the chaos and noise of Yard; and some perhaps more troubling, like the friendship, talent and intellect of most

3 5

versus the thuggery of some others.

“Walking up the steps and into Grants there was always a sense of pride though I liked the way the entrance always meant a determined walk through the middle of things going on in Yard. And fun on the left-hand side coming from the TV room contrasted with the more serious things that seemed to happen to the right in the House Master ’s study. Even now, as someone who makes a living in Management Consulting – endlessly talking with and advising others – I like my peace and quiet too. I’ve wondered whether the years after the first year in a dormitory in ‘solitary confinement’ of the single rooms that made up the two corridors above the Grants dining room were the first taste of the pleasures of a quiet space!

“Above all, I remember the kindness and wisdom and teaching talent of people like Chris Clarke, Rodney Harris and many others Westminster, warts and all, is a special place – unique, magical, bonkers all at the same time. Grants was home for five brilliant years – time that shaped and made me like no other equivalent period yet!”

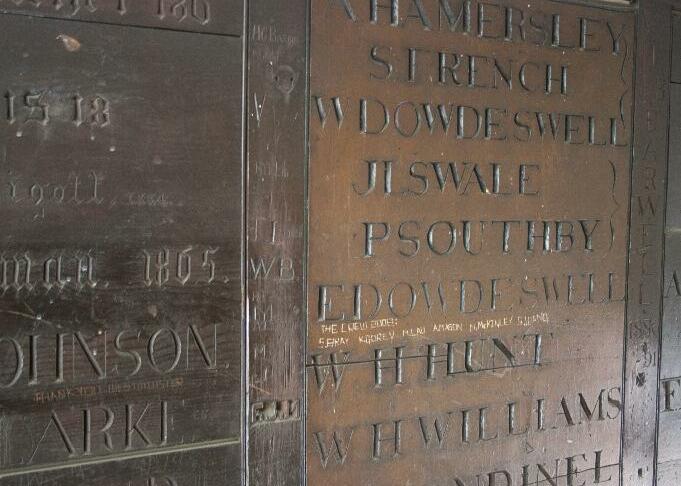

During part of David Edwards’ time as House Master, Peter Cole was the Head of House for 1997-98. He explained in detail the peculiar Grants tradition of walking the mantlepiece.

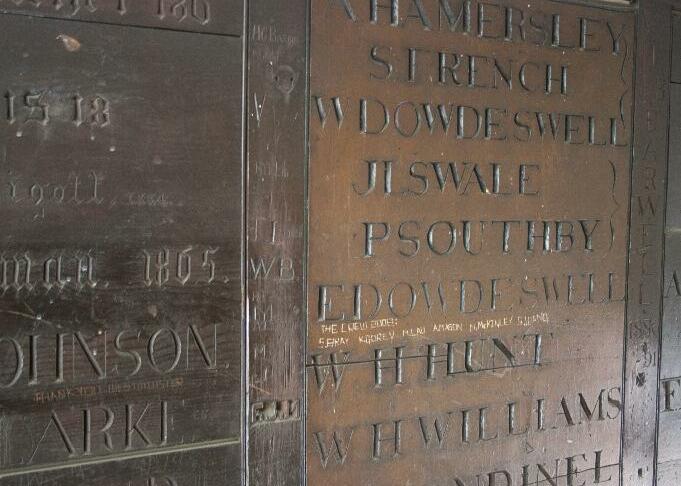

“During the first couple of weeks of a new year, the house would congregate in Grants dining hall to watch the new fifth form struggle up onto a narrow wooden ledge attached to the cladding at the far end. Then you had to walk along it and jump into the HoH’s arms (for me that was Alex Massey). The ledge can’t have been much more than 10 or 15 cm deep and this was incredibly difficult, especially when you weren’t much more than 5 ft tall. The clever ones and taller ones managed to gain a grip on the wooden boards that were nailed up above the ledge with the names of past HoHs and use those for balance. The whole thing was utterly terrifying as the whole house was watching and cheering, including the girls from Barton Street. I remember a couple of my fellow fifth forms falling off backwards onto their heads. I made it of course The year after I did this (1993) I think it was banned I felt a great injustice at this!”

3 6

“The introduction of the Children Act and the effect that had on fagging [lagging] and more generally marked a bit of shift in the social dynamics of the House, and definitely for the better I’ll be honest and say there were some pretty unsavoury characters in the house and general management at that point did little to discourage some pretty horrible bullying, but there was a noticeable shift after that point in the way the house was run. I credit David Edwards with a lot of those positive changes.”

On a lighter note (pun intended), Cole remembered the House Singing Competition, “must have been 1997 (I was HoH). We chose to sing the theme tune from Shaft (can you dig it?); terrible choice really but it meant we could all dress up as 70s gangsters (complete with afros) and yes, dress the fifth form up as ladies (as per usual) We crashed and burned as Rigauds (our great rivals at that point) were on before and switched off all the amps and microphones so no one could hear us when it came to our turn.

“Must shout out to Molly, the Grants dinner lady, who was a big character when I was there. She was a lady of few words but a lot of action and you crossed her at your peril. She was also very efficient. If you turned around to talk to someone on the bench beside or behind you at lunchtime, you’d turn back to the table to find your plate ‘cleared away’. But one look from Molly and you didn’t dare argue.”

Moving on to the years straddling the millennium, Gavin Griffiths – who had been in Wrens as a boy in the 1970s – became House Master of Grants from 1999-2006.

“Looking after Grants was an experience and a half. On taking over as House Master, I was informed that Grants was to be the official residence of the students from ‘Abroad’. Theoretically, you couldn’t come to Westminster as a boarder unless you had somewhere to stay at weekends. This rule was easily circumvented. So many student boarders spent seven days a week in the School – and we had students from Zimbabwe, China, Japan, Korea, Russia, to name but a few. They provided company for each other to some extent, but after twelve weeks were surprisingly not always on the best terms Unforeseeable. In any case, Grants was not the best House to select for this

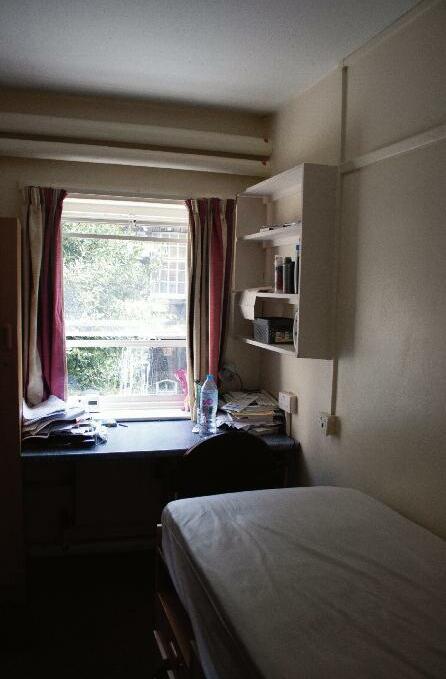

3 7

spangly international role. In 1999, there were four ‘decent’ rooms; the rest were disgracefully tiny – a bed and somewhere to hang your socks. One Russian student, whose patient demeanour never ceased to amaze, spent two years in a space that would prepare him well were his government ever to force him into exile. Eventually, the Authorities were persuaded to knock down a few walls and, miraculously, we then had six ‘decent’ rooms.

“The worry was that boarding would disappear altogether. In my first years, House Masters were encouraged to show potential day pupils and their parents the startling boarding facilities – telly, toaster, and one of the decent rooms – in an attempt to seduce parents into shelling out even more money for the moral and intellectual education of their offspring. After one such tour, one of many where my enthusiasm may have come across as ragged round the edges, an Italian mother put a violent stop to the proceedings ‘I do not understand, Mr. Griffiths, why you would have children, if you take the first possible opportunity to send them away from home. English people are so funny!’ No answer was forthcoming. Boarding numbers remained just about feasible, but it was difficult to persuade more than three or four children to board in the first year.

“The other issue was day pupils. Having come from Ashburnham, I was keen to prove that day pupils and boarders stood on an equal footing: and, given that there were over twice as many day pupils as boarders, this did not seem a bizarre intention. But the fuss when the first day pupil (ever) was appointed Head of House once again showed that the young are as conservative and hierarchical as their elders.

“The other chief development in this direction was the development of tutoring. In days of yore, a tutor would sit down with tutee, flick through the end of year reports and, with magisterial judiciousness, come up with, ‘That seems more or less OK.’ Tutors were now to be more involved. One newly arrived Grantite, whose unwavering suspicion of adults short-circuited hypocrisy, listened patiently as the tutor unveiled the fun that would be had in the following years. How, as tutor, he would be talking to teachers, checking preps, encouraging sport, coming to watch musical performances and contacting parents on a regular basis He finished his set-piece with a question, embalmed in compassion.

3 8

‘Have you anything you would like to ask?’

‘Actually, yes! I was just wondering why on earth you imagine any of this stuff has anything to do with YOU?!’ Possibly, to misquote Dr Johnson, a sentiment to which every bosom returns an echo.

“The high point of the morning was Registration, done with pen and book, rather than electronic gizmo. Students would come into the study; I would tick their names, and an attempt would be made, despite the early hour, at communication. The full importance of my job came to me when a Grantite, still half asleep, walked past the door, ignoring the ritual. Self-righteously, I called her into the study to say good-morning properly. Still dozy but with great kindness, she apologised, rootled about in her bag and handed me her student Oyster card. Temporarily, she had mistaken me for an official on the London Underground In retrospect, this was quite flattering ”

After Gavin Griffiths, David Hargreaves took the helm as House Master.

“I loved running Grants – no qualifiers needed there. I faced a couple of health challenges along the way and found myself getting pretty tired after seven years. But it was always interesting, and mainly fun. The pupils explain that. When you work with upwards of 75 of them in close proximity (I think we reached 81 in my last year), you find you draw off your full range of professional and life experience. As I grew more into the role, my attempts to get people to do up their ties before Abbey became less wholehearted and more parodic. On the other hand, I worried more if people disengaged from their work, especially in the Upper School. The habits of diligence, once acquired, were immensely reassuring for pupils – they were adolescent enough to enjoy feeling they were keeping up with their peers, and sufficiently sophisticated to see the connection between genuine immersion and a keen critical judgement. However surprising it might be appear to students at other schools, academic success – next only to friendships – was what many pupils minded about most. But friendships did mainly come first – no doubt about that.

“The tribal identity of the houses was occasionally insisted upon (during noisy chants at House football or House Singing, back in the day), but most

3 9

pupils expected to draw their friends from all over the school and not just from Grants. Given our location, we were an inevitable drop-in centre. Perhaps like a parent who wants his kids to be feel comfortable enough about their own home to risk bringing their friends round, I was happy to see fresh faces in the Pool Room. It was a bit trying when people of all houses dropped their bags all over the hall on their way to lunch or tea, but hardly a big deal.

“The boarding side took up a lot of my time – not just the being-there part –but I took my share in trying to protect its position within the school. Ever since the 1980s, there had been a lot of casual slippage. Older pupils in particular often felt the charms of having their friends on site were less of a draw than the dearth of restraints in a comfortable London home. Equally, numbers of those seriously keen to come and board at thirteen were also falling Children educated in London prep schools were more likely to be deterred by the prospects of sharing a room (in GG, that happened only in the Fifth Form) than they were to be lured by any Greyfriars idea of boarding as a jolly adventure.

“During my time, there were a lot of school-wide initiatives designed to help. There were endless theatre and concert trips during weekday evenings, gym nights, a weekly dance class – and, as with other Houses, we added plenty of plays and concerts of our own. Obviously, I tried to make the place feel safe, and welcoming without being cloying. In my case, that meant borrowing lots of modern art from a gallery in Cork Street, buying interesting old furniture second hand from the Classifieds to put in the day rooms, and putting in cheap lamps with paper shades from Argos in an effort to wean everyone away from foul overheard strip lighting. It feels a bit precious looking back, but I suppose we all try to find ways to express ourselves in the role. I also used to cook pasta for anyone Up House who felt like a second supper after prep on a Thursday. I don’t know how much difference any of this made to the systemic challenges of recruiting boarders at 13+, but I think they raised expectations and were part of a broad goodwill.

“Socially, academically, sportingly, and culturally, the girls in my time felt to me to have been generally happy in the house and fully involved. Looking back, I am less confident They had a room of their own (a pretty dingy one) but, even by the time I left in 2014, still had no proper changing facilities or

4 0

showers. Nor did I make any girl Head of House – as should have happened on at least two occasions. Traditionally the position was occupied by a boarder, and I should have been less hidebound Undercurrents of life which have surfaced in many schools suggest that many blithe assumptions made about the integration of boys and girls were complacent and plain wrong. I hope that wasn’t the case with us.