Th e New York City DEATH AND BURIAL OF President James Monroe

SCOTT HARRIS

SCOTT HARRIS

39 OPPOSITE: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION TOP: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

james monroe undertook many long and eventful journeys throughout his seventy-three-year life. He crisscrossed the north ern colonies from 1776 to 1778 with the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. While serving as a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress from 1783 to 1786, he explored largely unsettled frontier territory in the Old Northwest. He made two round trips across the Atlantic in the 1790s and early 1800s for diplomatic assignments in France, Great Britain, and Spain. As president of the United States, Monroe undertook three extensive tours of the country: to northern states in 1817, the Chesapeake region in 1818, and the South in 1819.

After traveling far and wide in life, James Monroe continued his odyssey in death—first on a brief and somewhat confusing shuttle between two New York City cemeteries with almost identical names, and finally back to Richmond, the capital of his native state, Virginia. Monroe’s postmortem journeys occurred within an atmosphere of public veneration tinged with commercial and political exploitation.

MONROE’S NEW YORK BURIALS

Monroe died on July 4, 1831, in the home of his daughter, Maria, and her husband, Samuel Gouverneur, at 63 Prince Street in Manhattan. He had moved there after the death the previous year of his wife, Elizabeth Kortright Monroe. Still grieving that loss, he had also endured intense pain from a persistent cough that may have been a symp tom of tuberculosis. 1 Monroe’s long time friend and political associate Tench Ringgold informed James Madison of Monroe’s death in letters written on July 4 and July 7, 1831— the latter being the day of Monroe’s funeral:

I gave you, on the 4th instant, a short account

of the death of your old and valued friend Mr Monroe; and now perform the promise, then made, to write to you again before I left this City. . . .

For many weeks before his death, he was convinced it was impossible for him to recover, & he repeatedly exprest the most ardent wish to die; when the event approached he met it, calm and resigned.2

As the third former president of the United States to die on Independence Day (after John Adams and Thomas Jefferson in 1826), Monroe inspired a funeral that was one of the largest public events in New York City up to that time. One newspaper estimated the procession to be “more than two miles in length. . . . Every street through which the procession moved, was lined with people, the windows and housetops were crowded with every sex and age, spectators of the solemn scene.”3 Udolpho Wolfe, a New York businessman whose father served with Monroe in the Revolutionary War, later published this account:

The interment of President Monroe’s remains in the Second Street Cemetery, took place on the 7th of July, 1831, and was one of the most imposing ceremonies ever witnessed in New-York. The announcement of his death was appropriately noticed by the various legislative, literary, commercial, and judicial bodies in New-York, who universally passed resolutions expressive of their high respect for the deceased, and in favor of attending the funeral. The body was taken by a guard of honor from the residence of his son-in-law, Samuel L. Gouverneur, accompanied by his near relatives and friends, and deposited on a platform which was erected for the occasion, and draped with black cloth, in front of the City Hall, where President Duer, of Columbia College . . . delivered an appropriate address.

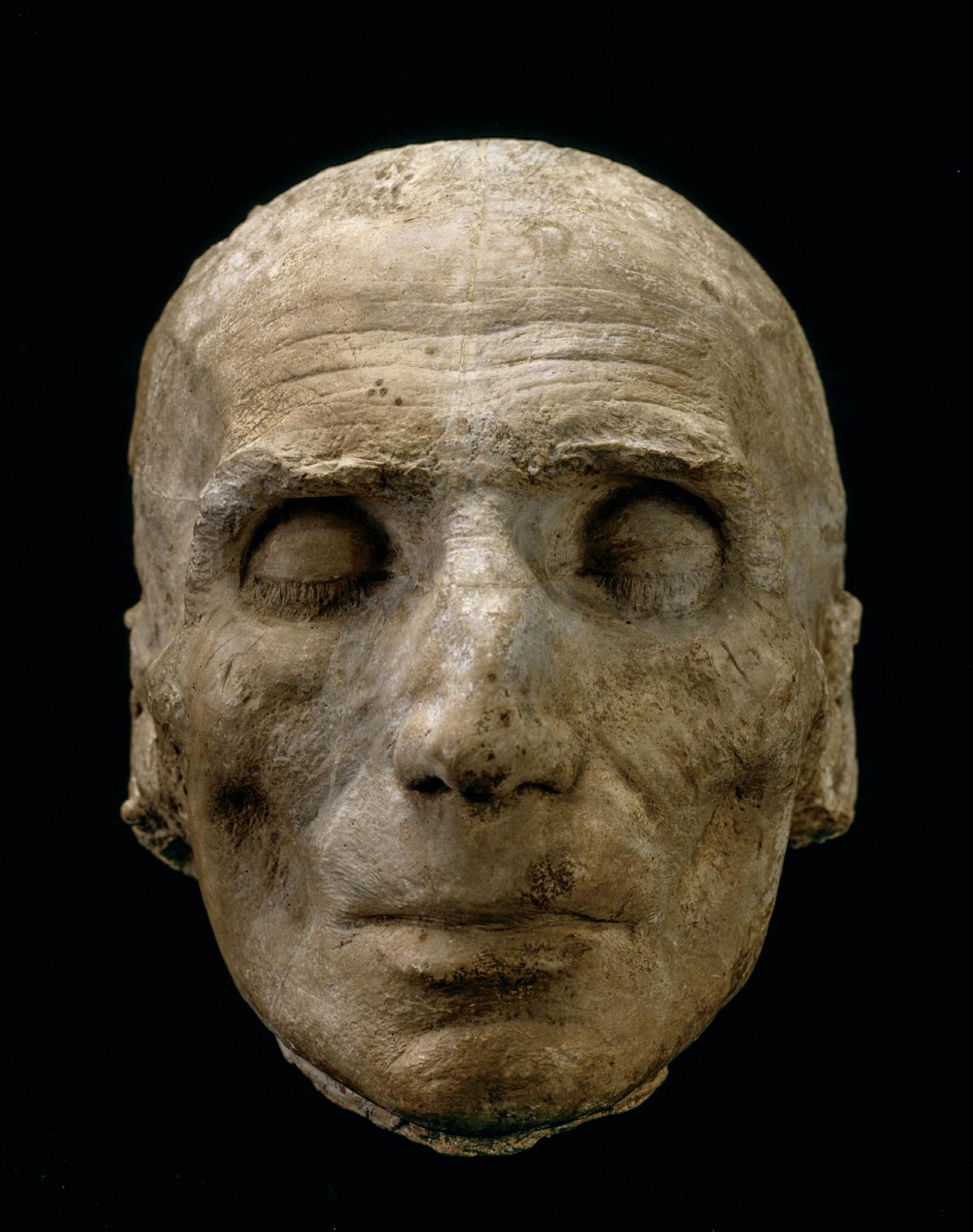

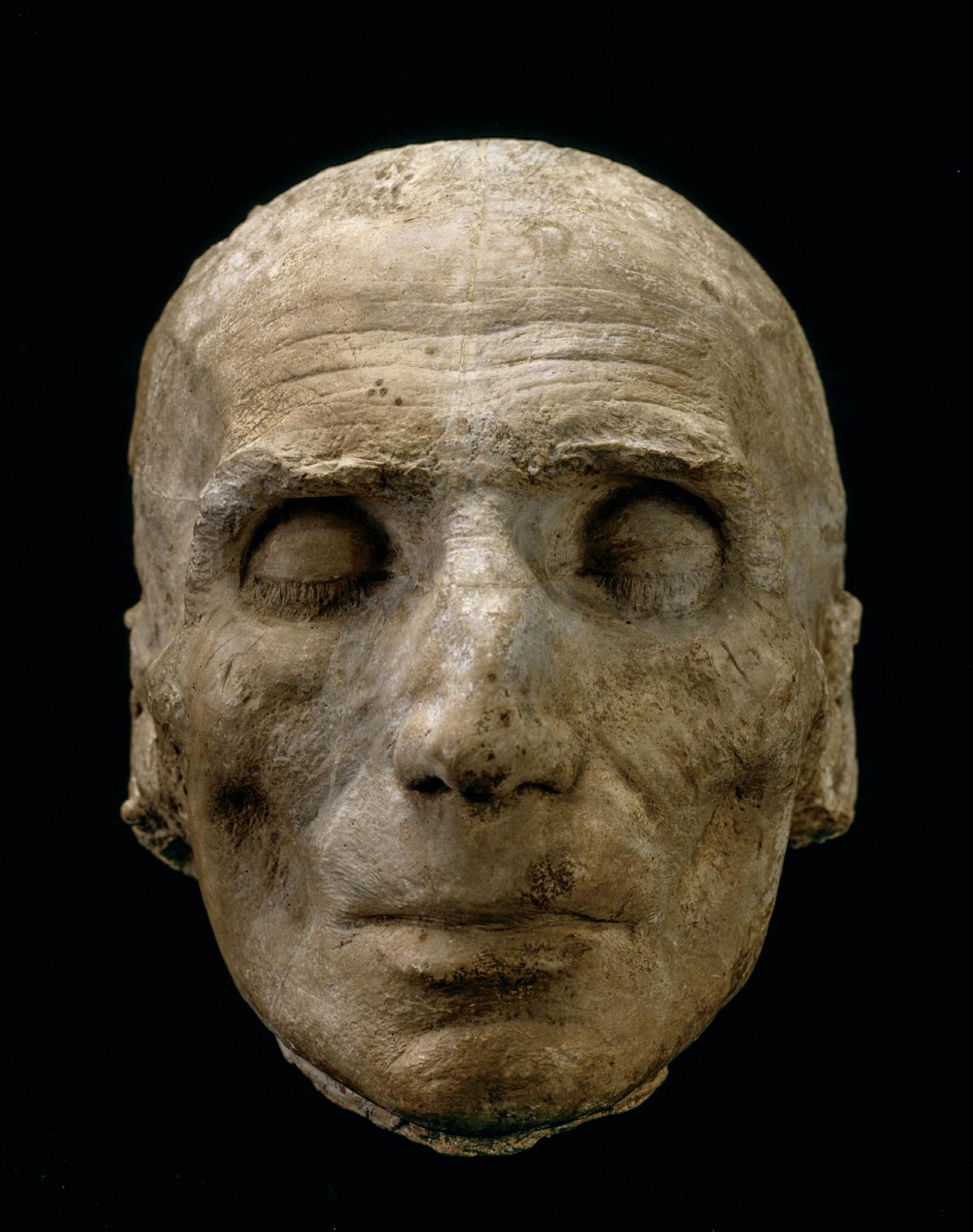

left Artist Chester Harding captured this likeness of James Monore near the end of his life in 1829. After his death in 1831, the mask below was made by New York artist John Henri Isaac Browere. The mask is now in the collection of the Fenimore Art Museum.

previous spread Marble markers embedded in a stone wall identify vault owners in the New York Marble Cemetery where President James Monroe was briefly interred after his death in 1831. He was soon reinterred in the nearby New York City Marble Cemetery. In 1858 his remains were exhumed and his casket displayed in City Hall, a scene captured by a Harper’s Weekly artist, before a final entombment in Richmond, Virginia.

40 PORTRAIT: GETTY IMAGES / MASK: FENIMORE ART MUSEUM white house history quarterly

My

Dear Sir

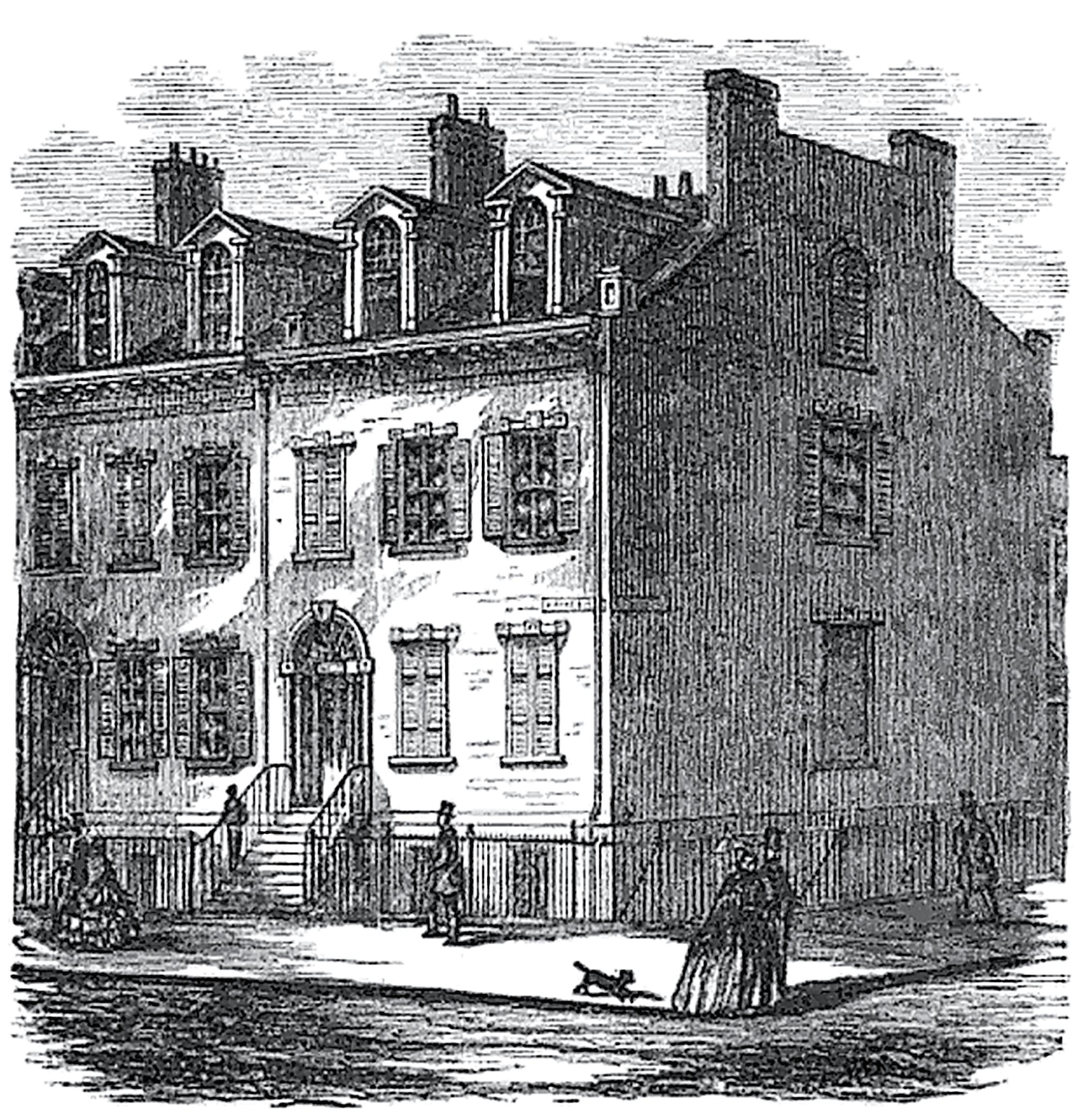

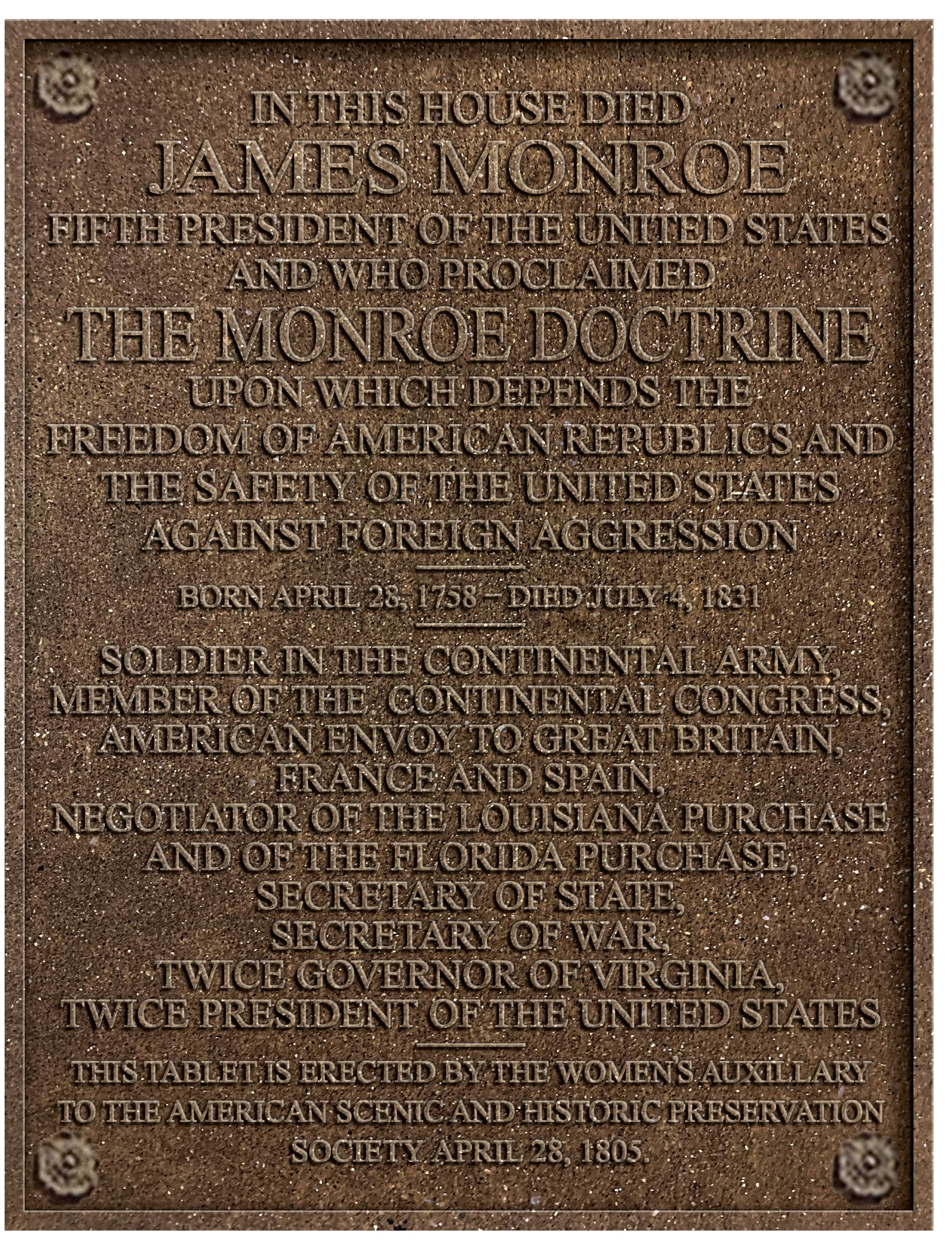

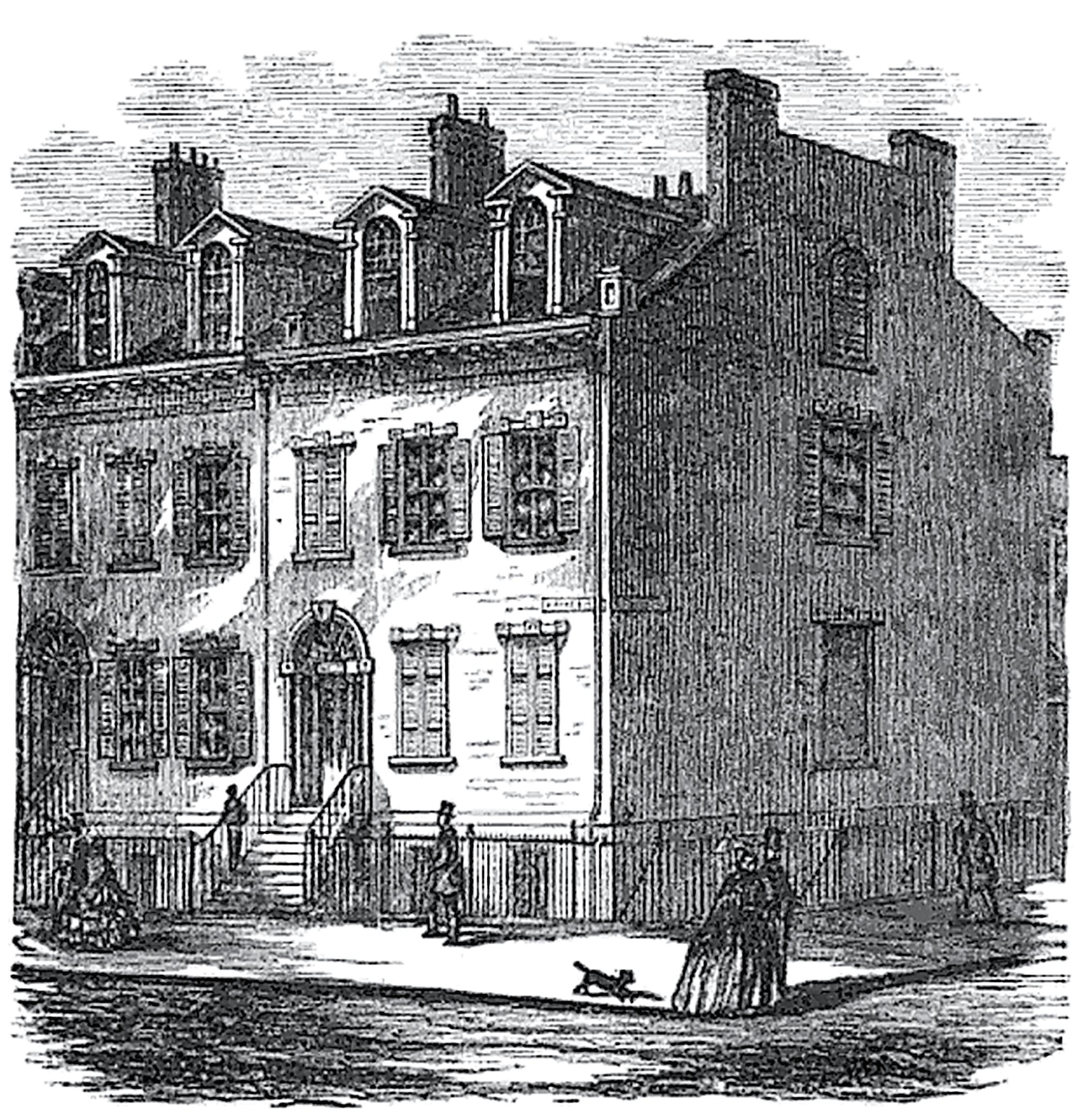

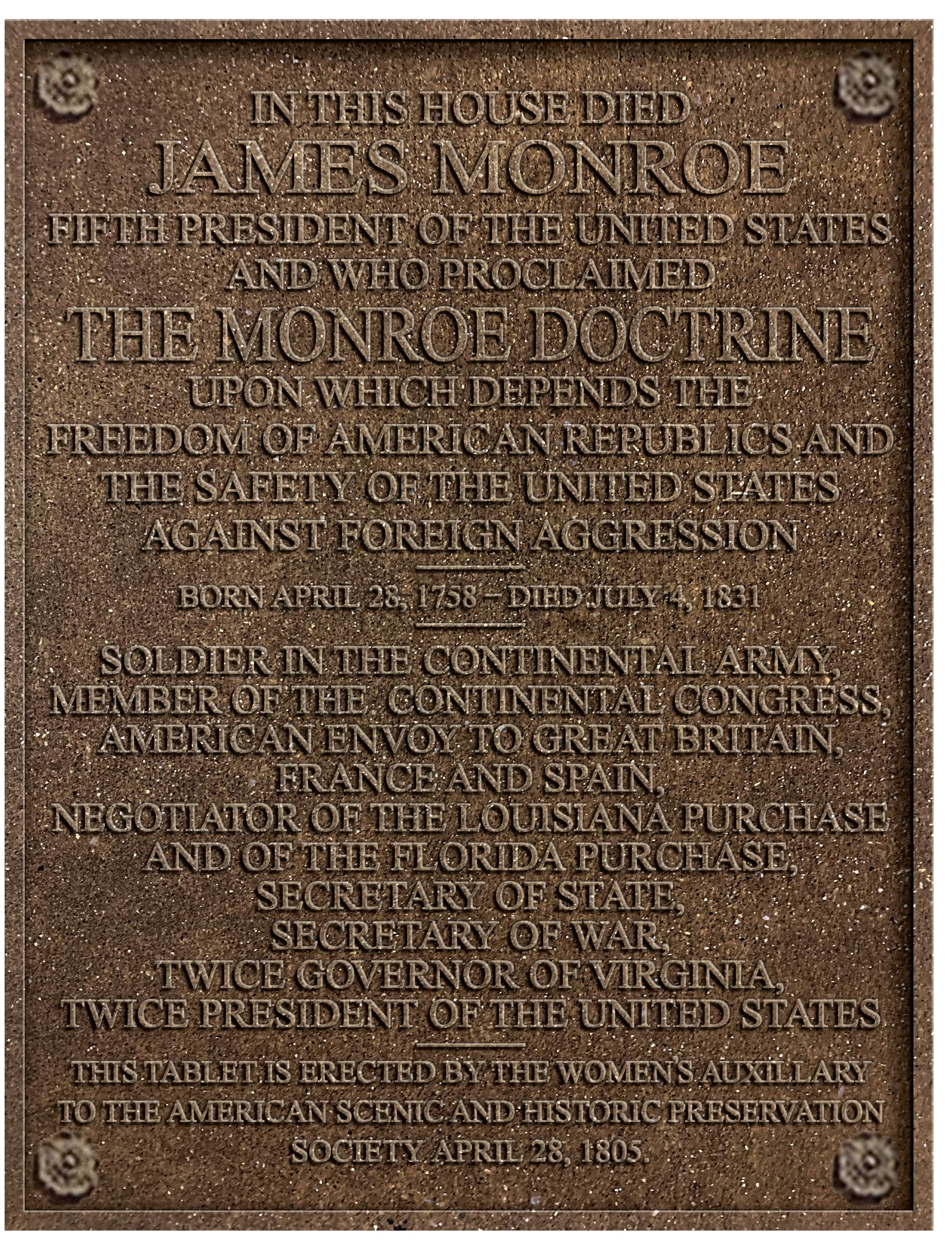

President Monroe was living in the New York home of his daughter Maria and her husband, Samuel Gouverneur, when he died, July 4, 1831. The house at 63 Prince Street (seen top left in the 1820s and below c. 1900) was embellished with a historical plaque by the Women’s Auxillary of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society in 1905. Although efforts were made to preserve the house, it fell into decay and was eventually demolished.

41 TOP LEFT: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION / TOP RIGHT AND BOTTOM: ALAMY white house history quarterly

The body was from thence taken to St. Paul’s Church, the pulpit and reading desk of which were clad in mourning, where the solemn service of the Episcopal Church was read by the Rev. Bishop Onderdonk and Dr. Wainwright.4

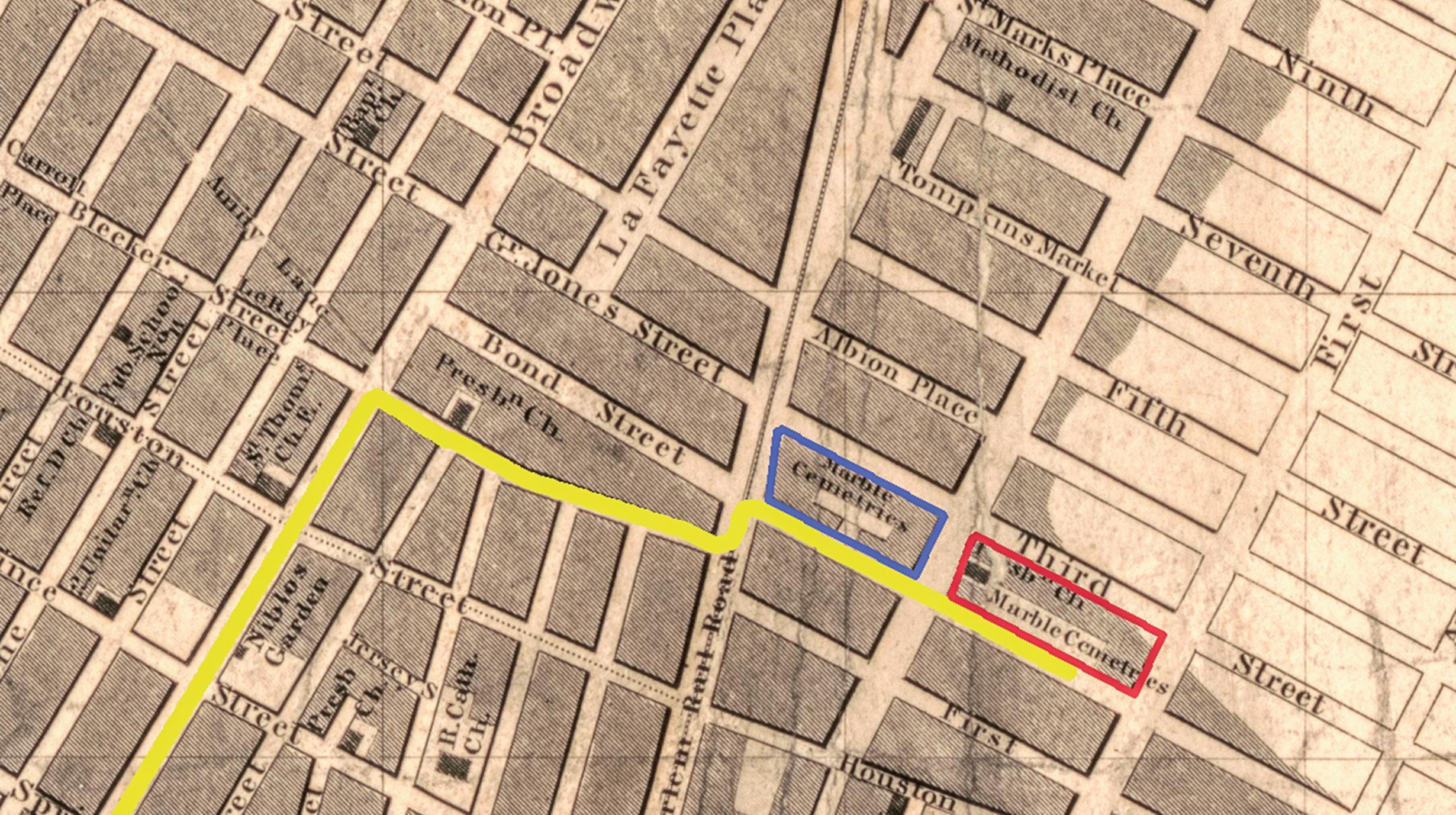

The reference to “the Second Street Cemetery” in Wolfe’s account could describe either of two burying places in New York City that are bordered by the street so named. Both were in business in 1831. They were developed and promoted by the same local businessman and have almost identical names: the New York Marble Cemetery and the New York City Marble Cemetery. Each temporarily housed the remains of James Monroe.

The New York Marble Cemetery was incorporated on February 4, 1831, though site development and burials began late in 1830. Located at 41½ Second Avenue and developed by businessman Perkins Nichols, it was the first public, nonsectarian burial place in the city. The cemetery proved so popular that Nichols founded another one in the summer of the same year (though it was not formally incorporated until April 26, 1832). This was the New York City Marble Cemetery, located across Second Avenue from the first graveyard, and additionally bounded by Second and Third Streets and First Avenue. Although there are many similarities between the two, they have always operated independently. Both cemeteries were at that time on the northern edge of development in lower Manhattan, in an area which already contained several church cemeteries.5

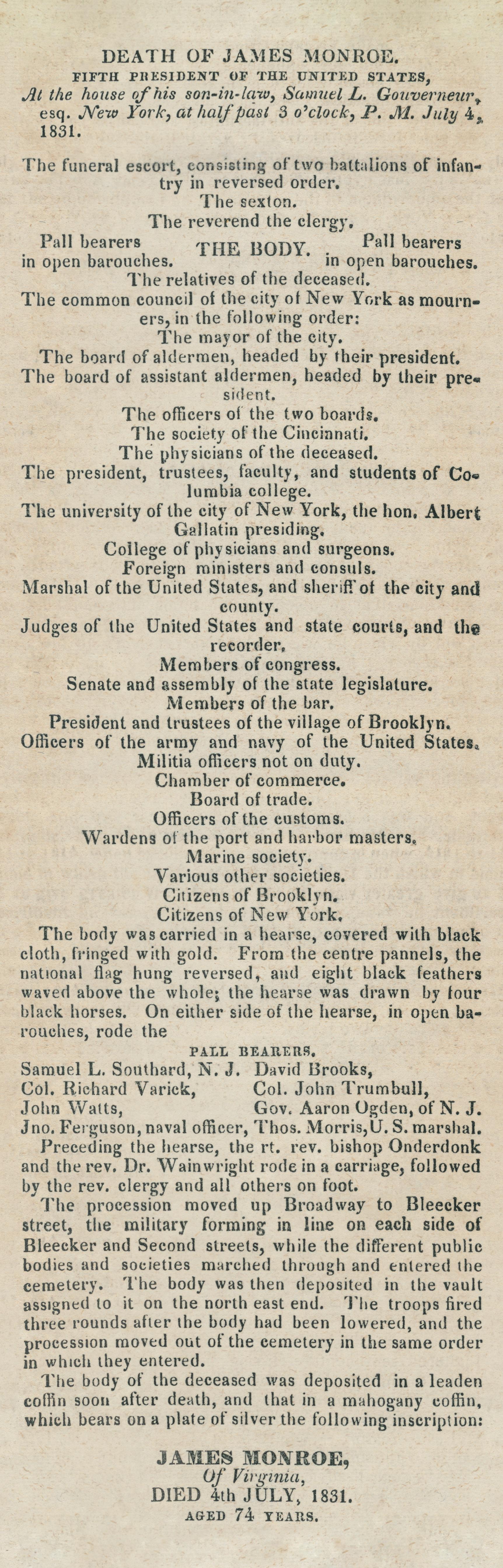

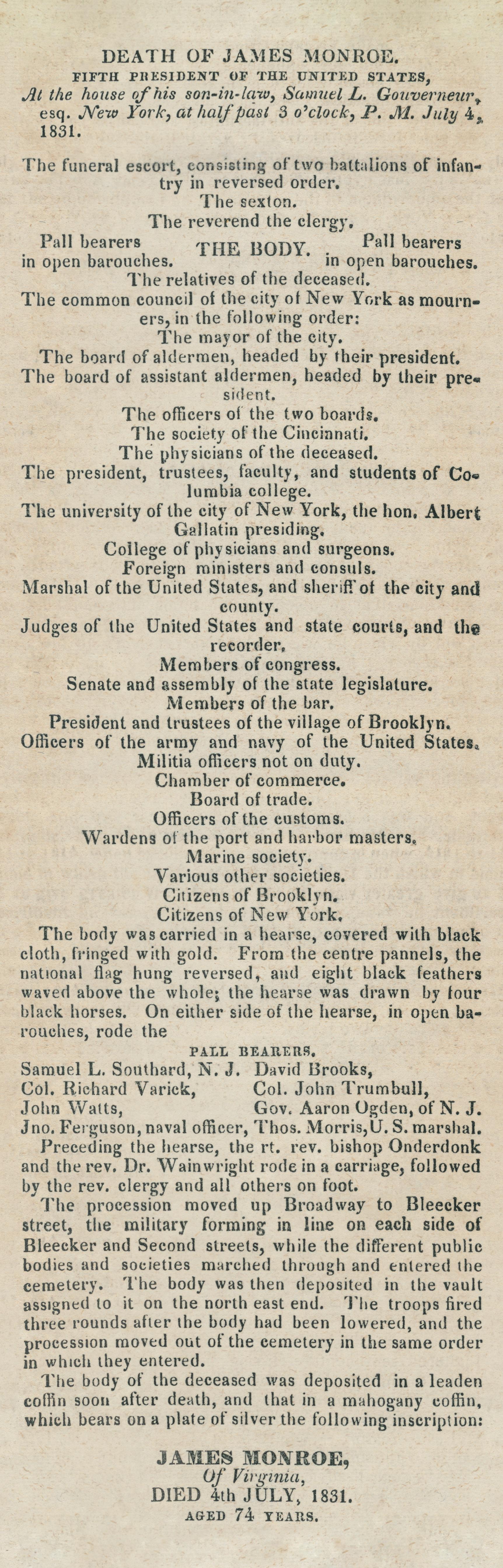

On July 23, 1831, the Baltimore newspaper Niles’ Weekly Register published a lengthy account of Monroe’s funeral that included the order of the procession from St. Paul’s Chapel and the route taken by the procession to the cemetery (or cemeteries):

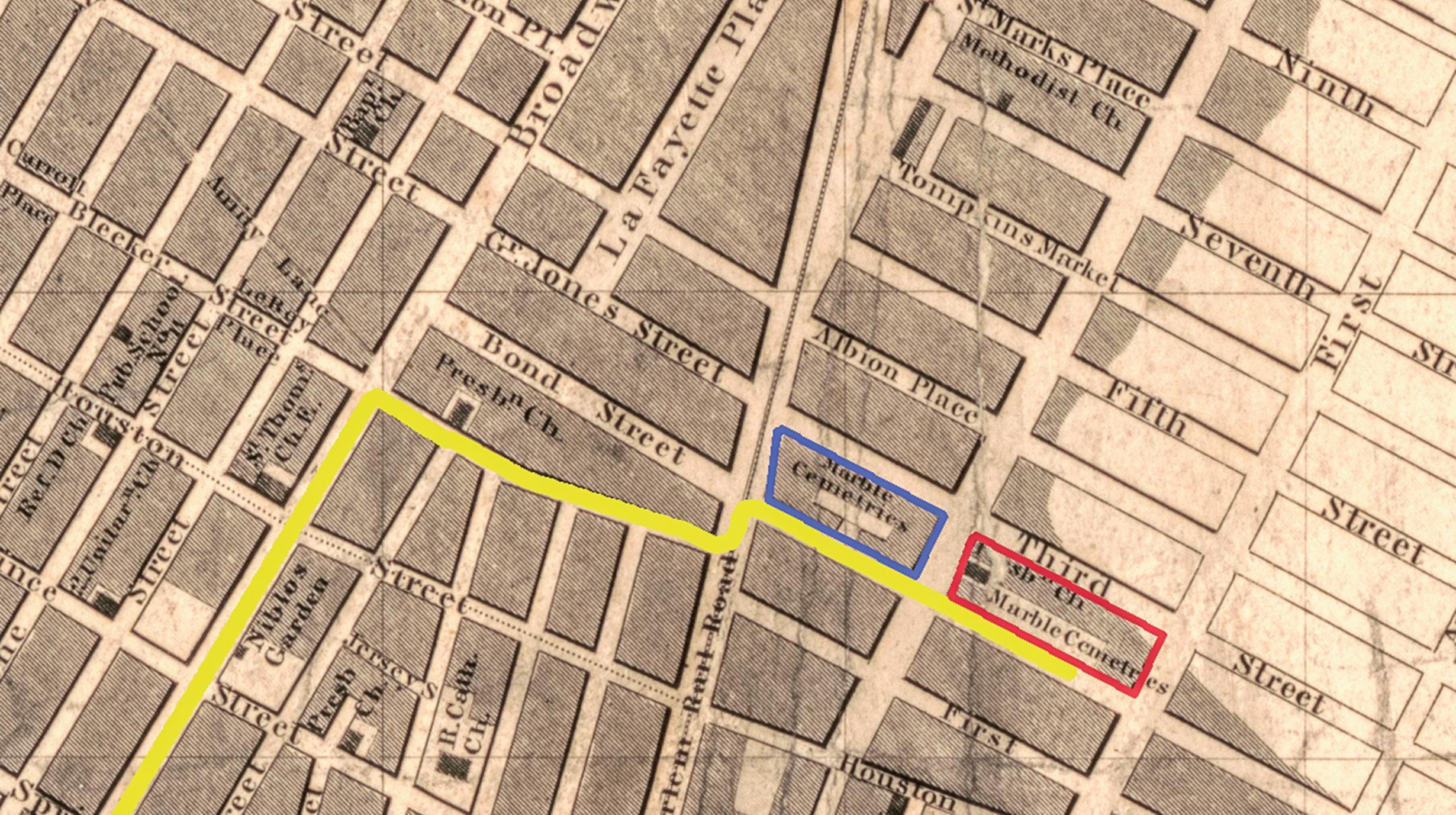

The procession moved up Broadway to Bleecker street, the military forming in line on each side of Bleecker and Second streets, while the different public bodies and societies marched through and entered the cemetery. The body was then deposited in the vault assigned to it on the north east end. The troops fired three rounds after the body had been lowered, and the procession moved out of the cemetery in the same order in which they entered.6

As the procession passed by the troops in formation, it would have encountered the older New

An excerpt from a lengthy account in the July 23, 1831, Niles’ Weekly Register details the participants in James Monroe’s funeral procession, as well as the route taken. According to this report, the hearse progressed up Broadway to Bleeker Street to the cemetery, where the body was deposited in the “vault assigned to it.”

42 WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

Two cemeteries on Second Avenue are seen on the route of the Monroe funeral procession (traced in yellow) on this 1833 map of Manhattan. From St. Paul’s Chapel, the procession moved north on Broadway, turned east on Bleeker Street and continued on Second Street. New York Marble Cemetery (outlined in blue) was likely a short-term resting place for Monroe’s remains. New York City Marble Cemetery (oulined in red) just one block farther east, would hold Monroe’s remains for twentyseven years.

York Marble Cemetery first, and beyond that the New York City Marble Cemetery, then under construction. The account says that Monroe’s body was “deposited in the vault assigned to it on the north east end,” but does not say which cemetery.

The New York Marble Cemetery’s record of burials says the following: “Monroe, James. 07 Jul 1831 b 1758. Removed to NYCMC.”7 “NYCMC” is the New York City Marble Cemetery. That cemetery’s records say the following: “Vault #147 Monroe, James. Interred: 7 Jul 1831. Removed: 2 Jul 1858.”8 Why were the remains of James Monroe apparently interred in two different cemeteries on the day of his funeral? The answer to this question may be found by examining excerpts from stories about the event that appeared in two other newspapers.

On July 16, 1831, the Charleston (S.C.) Daily Courier reprinted an account of the funeral from the New York Mercantile Advertiser of July 8. The story noted the arrangements for interring the body:

The place assigned to deposit the body, was the new Marble Cemetery of Perkins Nichols, Esqr. on Second-street, between the 1st and 2d Avenues; there, in a vault especially appropriated by the owner for that purpose,

the remains of James Monroe were deposited at 7 o’clock. The Artillery and Infantry fired three vollies over the hallowed spot, when the troops, citizens and societies left the ground under direction of the Grand Marshal.9

The location of the “new marble cemetery of Perkins Nichols, Esqr.” aligns with that of the New York City Marble Cemetery. It also implies that the body was placed in a vault there. However, a story in the New York Herald published on May 2, 1858, (when preparations were under way to relocate Monroe’s remains to Virginia) describes a somewhat different sequence of events:

The body was first interred in the old New York Marble Cemetery, founded by Mr. Norris, who allowed it to be placed in his private vault for a time whilst the New York City Marble Cemetery, in which the remains now repose, and in which the Gouverneur family had a vault building, was being constructed. The President shares his grave with Thomas Tillotson, so that the fifth President of the United States has had as yet no tomb of his own, and is even now resting in a vault upon which there is an unpaid assessment of many years standing. Verily, “republics are ungrateful.” 10

43 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS white house history quarterly

The reference to “Mr. Norris” as founder of the New York Marble Cemetery is a misnomer, as the actual founder was Perkins Nichols. Samuel Gouverneur, husband of James Monroe’s daughter Maria, is often identified as the owner of Vault 147 in the New York City Marble Cemetery. However, the cemetery’s records identify Robert Tillotson (the son of Thomas Tillotson) as the owner. Samuel Gouverneur may have leased space for his family members from Robert Tillotson, a common practice at the time.11

How can this confusion be explained? Anne Brown, trustee emerita of the New York Marble Cemetery, shared in a conversation with the author her belief that Monroe’s body would have been placed in that cemetery’s Vault 51, which was owned by Perkins Nichols. Unlike other vaults, 51—and its companion vault, 52—were accessible by a permanent ladder, allowing for relatively easy placement and removal of remains. According to Anne Brown, Nichols had a reputation for accepting temporary burials in his vault, usually for a fee.12

The New York City Marble Cemetery website quotes the following from its New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designation form, prepared in 1969:

The most important person buried in this cemetery was ex-President James Monroe, who had moved to New York in 1830, after the death of his wife, to live with his son-in-law, Samuel Gouverneur. Gouverneur owned a vault in the cemetery, and when Monroe died on July 4, 1831, he became one of the first to be buried here. The interment ceremonies were carried out with much pomp and military pageantry, which served to increase greatly the prestige of the cemetery.13

The phrase “which served to greatly increase the prestige of the cemetery” may offer another clue as to Perkins Nichols’s motivation for facilitating the various dispositions of President Monroe’s remains.

Examining the sundry accounts of James Monroe’s New York interments does not paint a precise, consistent picture of what happened to his remains on July 7, 1831, though the 1858 New York Herald story offers the most straightforward explanation: Monroe’s body was housed temporarily in the New York Marble Cemetery, in either the vault owned by Perkins Nichols or in another appropriated through his efforts. Since most accounts

of the funeral point to the procession concluding at the New York City Marble Cemetery, it seems likely that the body was brought there first and was moved to the other cemetery’s vault following the ceremony that same day. It remained there for an unknown number of days, or perhaps weeks, until the Tillotson / Gouverneur vault was ready for the transfer. The fact that records of both cemeteries show interment on July 7 could reflect the body’s progress through each or could be a clerical error.

Original records of the New York City Marble Cemetery covering the years 1831 to 1843 were

44 white house history quarterly BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

The gates to New York Marble Cemetery, where President Monroe was briefly interred in 1831, carry a historical marker identifying the site as the oldest public nonsectarian cemetery in New York.

The original owners of the 156 underground marble vaults in New York Marble Cemetery are named on the marble markers set in the stone wall that surrounds the perimeter of the small cemetery. No monuments are allowed on the ground above the underground vaults. The cemetery, now surrounded by tall buildings, is seen here in 2023.

45 white house history quarterly BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

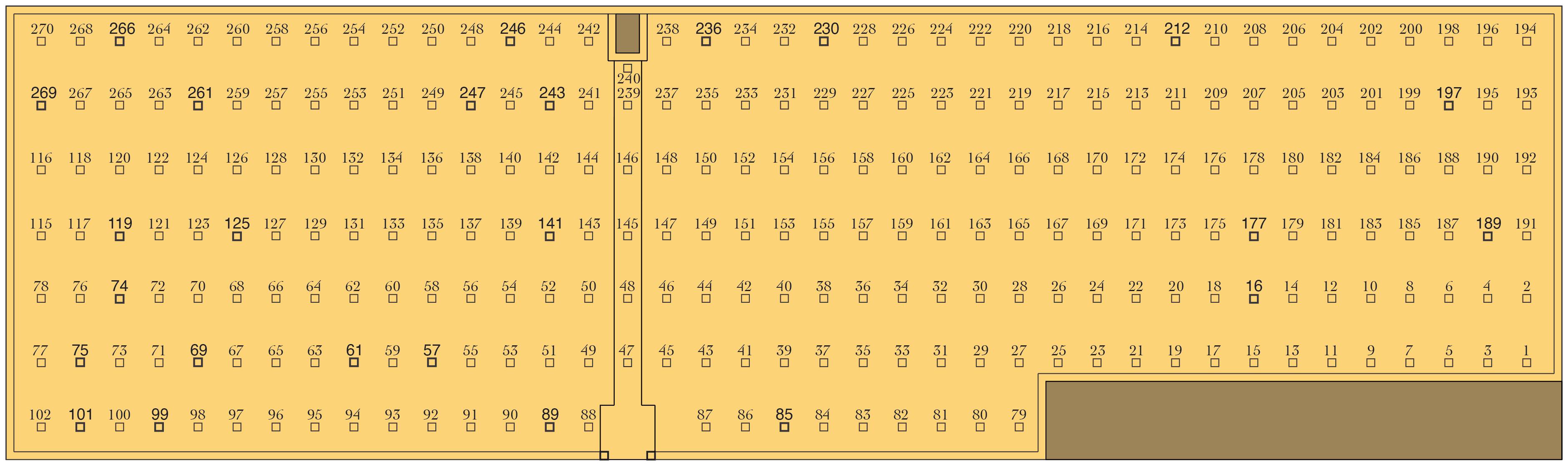

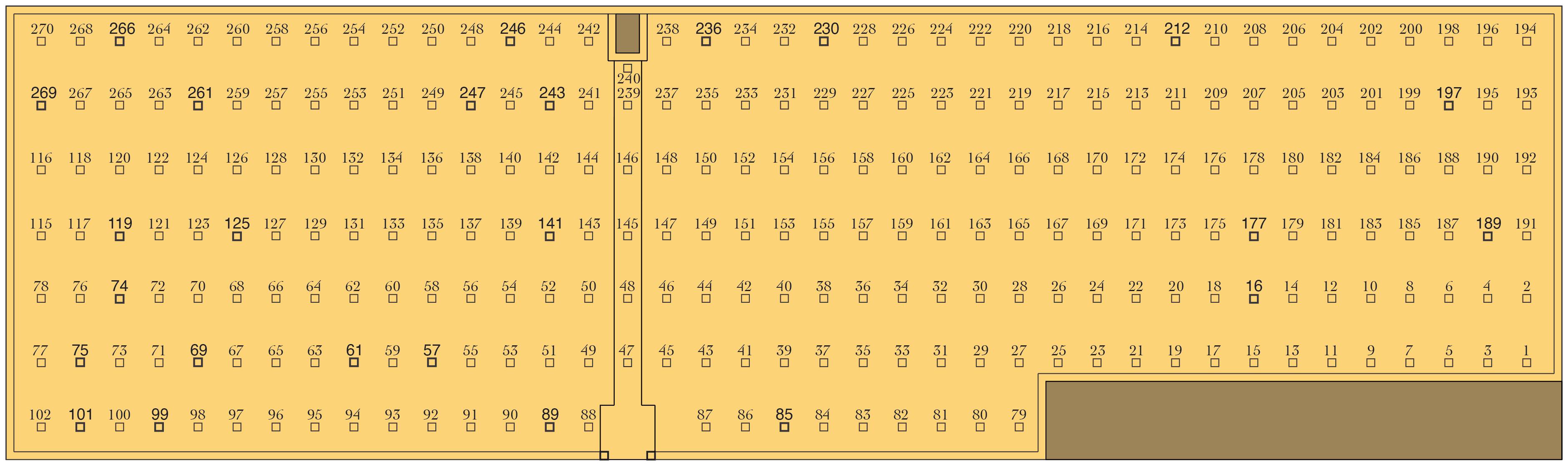

left and opposite Views of the New York City Marble cemetery, President Monroe’s second resting place, are seen here in 2023. Unlike New York Marble Cemetery, monuments are allowed on the ground here. Monroe was interred in the Tillotson vault, no. 147 (see blue outline on diagram below) from 1831 until 1858. The location is still marked with his name although he is no longer buried there.

46 TOP: BRUCE

FOR THE WHITE

HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION / BOTTOM: NEW YORK CITY MARBLE CEMETERY white house history quarterly

WHITE

HOUSE

47 white house history quarterly BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

destroyed in a fire, though some of the information has been reconstructed from other sources. Inconsistencies in newspaper reporting regarding cemetery identification and vault location are not surprising, as conflating the names and locations of the two cemeteries has been a persistent problem even to the present day.14

MONROE’S RICHMOND BURIAL

James Monroe’s body remained in the New York City Marble Cemetery for just short of twenty-seven years before beginning a longer, final trek back to his native state. In 1858, the centennial anniversary of Monroe’s birth, Governor Henry Alexander Wise of Virginia formed a plan to relocate the former president’s remains from New York City for burial in one of three plots purchased by the Commonwealth in Richmond’s new Hollywood Cemetery. Wise also wanted to transfer the corpses of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison from their tombs at Monticello and Montpelier, respectively, to the other two plots. The first step was bringing Monroe home. The governor secured $2,000 from the General Assembly to purchase the three burial plots and initiated a contest for the design of Monroe’s tomb. 15

Why was Hollywood Cemetery chosen for this honor? The 135-acre site outside of downtown Richmond was established in 1847 by a consortium of local businessmen. Designed by Scottish-born architect John Notman, Hollywood (named for the prevalence of that species of tree on the grounds) epitomized a trend in the United States during the mid-nineteenth century to create pastoral, aesthetically pleasing burial grounds that would be equally attractive as public parks. Placing Monroe’s tomb in Hollywood not only provided a fitting resting place for a revered former president; it also suited Wise’s goal of highlighting Virginia nationally to defuse the growing sectional crisis over slavery while enhancing the governor’s status as a potential presidential candidate. The tomb was also seen as a useful enticement for wealthy Richmonders to patronize the new cemetery.16

Governor Wise sent a delegation from Virginia to New York City to receive Monroe’s remains and convey them to their final resting place. On July 2, 1858, New Yorkers bade farewell to their distinguished guest of nearly three decades, as reported in the New York Times the following day:

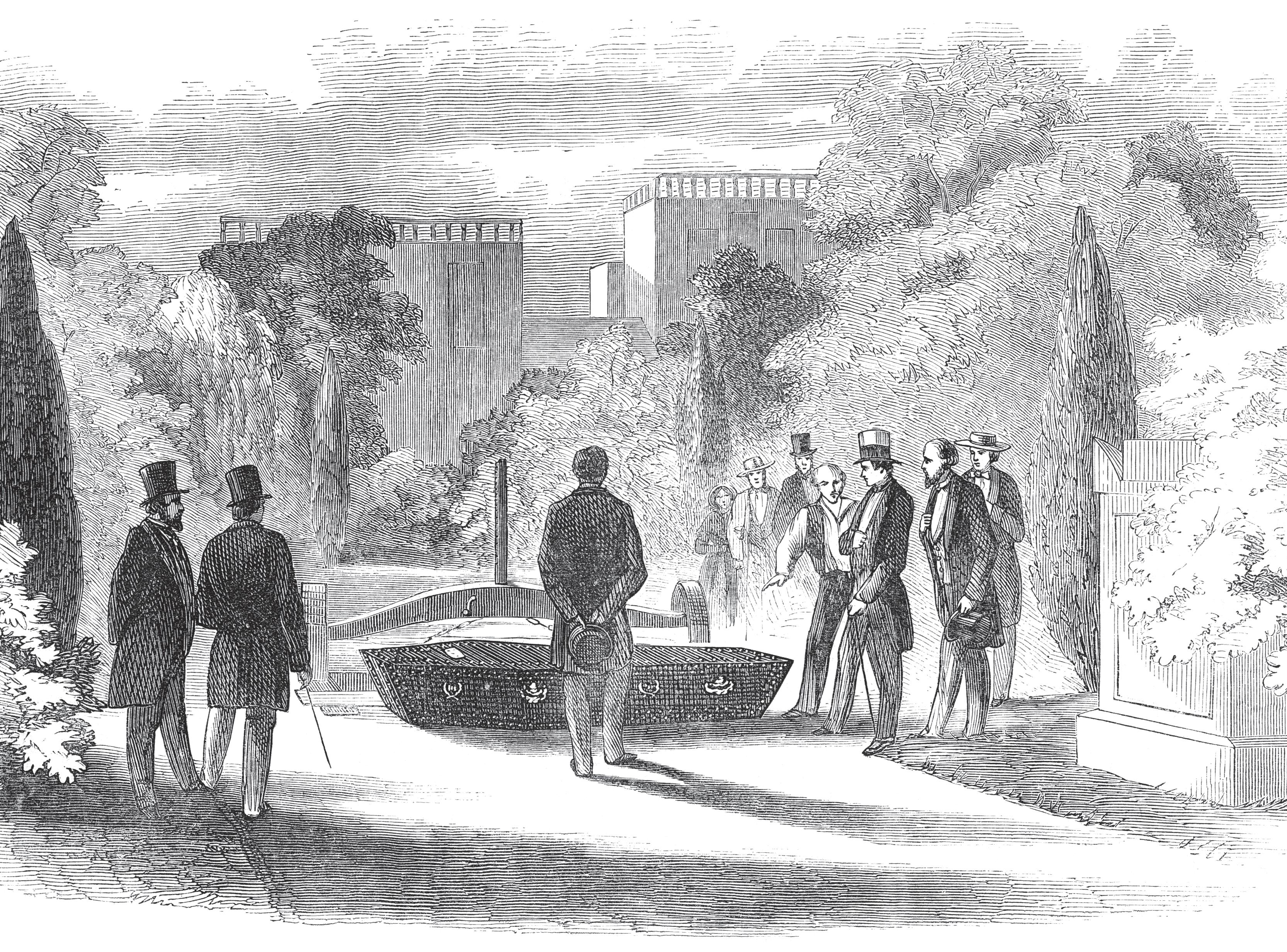

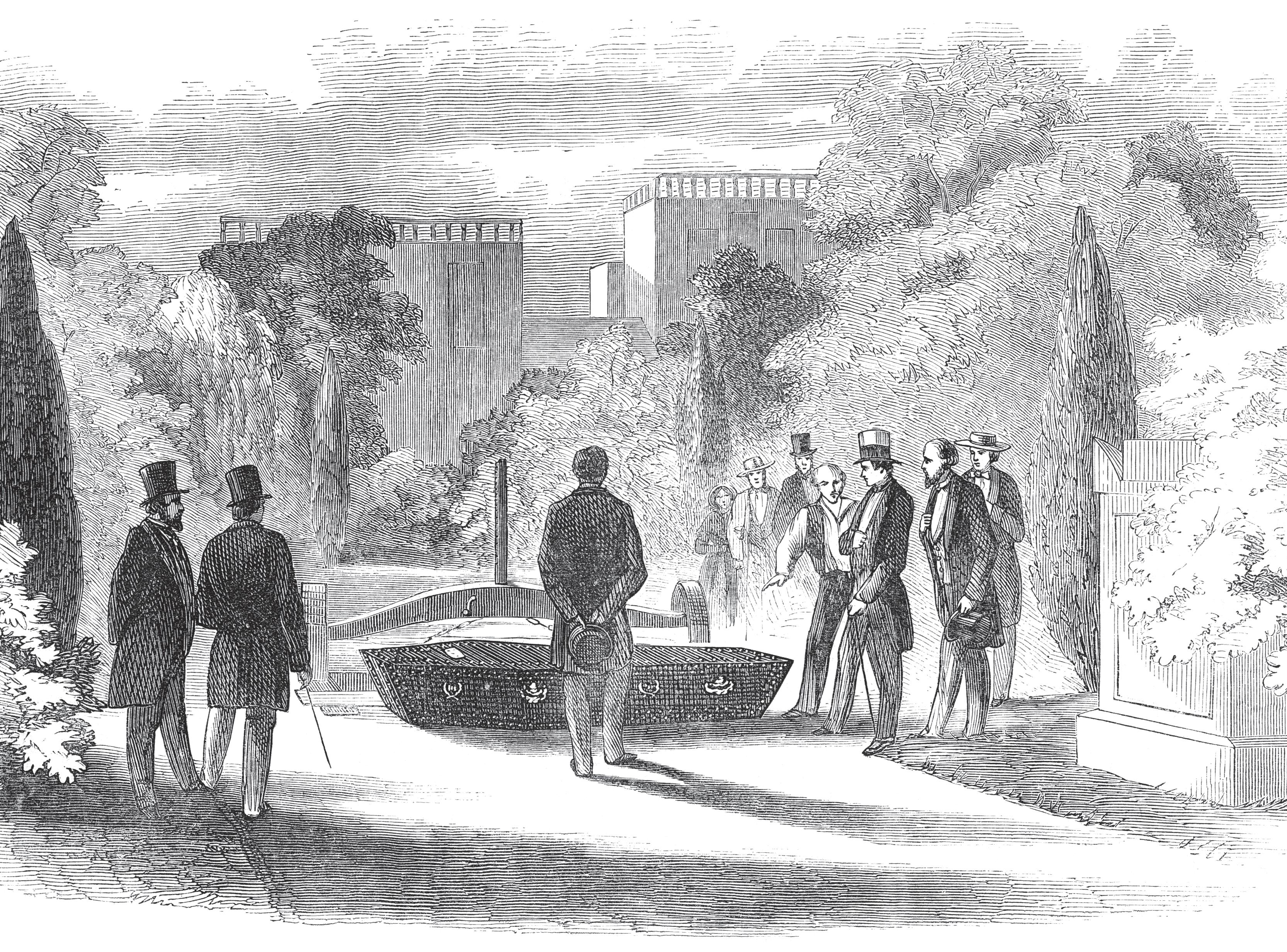

The July 17, 1858, edition of Harper’s Weekly included a series of illustrations documenting the relocation of President Monroe’s remains from New York City to Richmond, Virginia. In the first of four images, a small group gathers to witness the removal of Monroe’s casket from the vault in New York City Marble Cemetery.

48 WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

Monroe’s casket was moved from the cemetery to City Hall, where an estimated ten thousand people filed by to pay their respects to the fifth president of the United States before it was moved to the Jamestown to sail to Virginia. Monroe’s grandson, Samuel Gouverneur Jr., who was not at the event, commissioned this oil painting to include himself facing the foot of his grandfather’s coffin.

Exhumation of the Remains of President Monroe

The remains of James Monroe, fifth President of the United States, which have lain twentyseven years in the Second Street Cemetery, in this City, were early yesterday morning disinterred, and taken quietly to the Church of the Annunciation, in Fourteenth street. There thirty-three pall-bearers, distinguished, and, for the most part, honorable citizens, took charge of them, and, marching down Broadway, attended by a large procession of civilians and the military, with solemn music, while all the bells were tolled, and, from our national vessels minute guns were fired, laid them in state in the City Hall, under the guard of the Eighth Regiment. This morning the remains will be borne to the steamer Jamestown, and surrendered to the keeping of a Committee of the Virginia Legislature, who are charged to bear them to the statesman’s native state, Virginia, for reinterment.17

An estimated ten thousand people filed by Monroe’s casket in City Hall,18 recalling the honor shown by the citizenry twenty-seven years before, at his funeral. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, in its July 17 edition, pictured Monroe lying in state in City Hall. Monroe’s grandson, Samuel Gouverneur Jr. was serving as U.S. consul in Fuzhou, China at the time. Since he could not be present in New York, he commissioned an unknown Chinese artist to render an oil portrait of the scene, adding Gouverneur standing at the foot of the coffin.

The steamer Jamestown arrived in Richmond with Monroe’s remains on July 3, 1858. Two days later, the former president was interred in Hollywood Cemetery with full military honors. In 1859, James Monroe’s tomb was enclosed by a cast-iron Gothic Revival tomb fabricated by Wood & Perot’s Ornamental Iron Works of Philadelphia.19

For 156 years, the iron canopy, popularly known as “The Birdcage,” endured the ravages of weather, the Civil War, and repeated repainting of the original buff-colored metalwork with layers of black paint. By 2015, the multiple paint layers not only

49 white house history quarterly JAMES MONROE MUSEUM COLLECTION

Since 1858, President James Monroe’s remains have rested in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. The grand cast-iron Gothic Revival canopy enclosing the tomb, nicknamed “The Birdcage,” is seen here following an extensive restoration in 2017.

50

white house history quarterly JAMES MONROE MUSEUM COLLECTION

obscured the fine details of the canopy; they also masked serious deterioration to the metal structure that threatened to bring the distinctive landmark crashing down. A two-year $1 million restoration by the Virginia Department of General Services took apart 618 individual cast-iron pieces comprising the canopy, 40 percent of which had to be recast. All 2,500 fasteners that had held the structure together since 1859 were replaced.20 The restoration made this symbol of mourning an elegant and inspiring celebration of life, transforming the final resting place of James Monroe from a “birdcage” into a cathedral.

NOTES

The author is grateful for the kind assistance of Caroline DuBois, President, and Anne Brown, trustee emerita, of the New York Marble Cemetery, and Colleen Iverson, director of the New York City Marble Cemetery, in the preparation of this article. Their efforts, and those of many others, ensure that these historic sites are preserved and interpreted for the benefit of all. The author also thanks Heidi Stello, associate editor of the Papers of James Monroe, for invaluable research assistance.

1. John R. Bumgarner writes, “It is known that the illness lasted for several months and involved his lungs progressively. He had a harassing, exhausting cough, and suffered from fever and severe night sweats. His cough was productive of much mucous and at times gushes of blood. As the disease progressed, his breathing became more difficult. The clinical picture is highly suggestive but is not diagnostic of pulmonary tuberculosis.” The Health of the Presidents: The 41 United States Presidents Through 1993 from a Physician’s Point of View (Jefferson, N.C.: MacFarland, 1994), 35. The register of burials at the New York Marble Cemetery for the period December 7, 1830, to July 15, 1831, lists the cause of Monroe’s death as “consumption,” the period term for tuberculosis. Negative photostatic image of burial register provided to author by Anne Brown, trustee emerita, New York Marble Cemetery, July 1, 2021.

2. Tench Ringgold to James Madison, July 7, 1831, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov.

3. “Funeral of James Monroe,” Charleston (S.C.) Daily Courier, July 16, 1831, reprinting an article from the New York Mercantile Advertiser, July 8, 1831, 2.

4. Udolpho Wolfe, Grand Civic and Military Demonstration in Honor of the Removal of the Remains of James Monroe, Fifth President of the United States, from New York to Virginia (New York: John A. Gray, 1858), 14.

5. “A Brief History of the New York Marble Cemetery,” New York Marble Cemetery website, https://marblecemetery.org.

6. “Death of James Monroe,” Niles’ Weekly Register, July 23, 1831, 371–72.

7. “New York Marble Cemetery Interments by Name,” New York Marble Cemetery website.

8. “New York City Marble Cemetery Interments Listed by Vault,” New York City Marble Cemetery website, www.nycmc.org.

9. “Funeral of James Monroe,” Charleston (S.C.) Daily Courier, July 16, 1831, 2.

10. “The Graves of the Presidents: The Tomb of Monroe,” New York Herald, May 2, 1858, 8.

11. Anne Brown, conversation with author, June 28, 2021. Robert Tillotson was New York’s secretary of state from 1816 to 1817 and U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York from 1819 to 1828. His remains, and those of six other apparent family members, were removed from Vault 147 on November 9, 1894. Several of these, including Robert Tillotson, are buried in the Rhinebeck Cemetery, Rhinebeck, New York. Maria Monroe

Gouverneur died on June 20, 1850, and is buried with her mother and father in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia. Samuel L. Gouverneur died on September 29, 1865, and is buried at Saint Marks Apostolic Church Cemetery, Petersville, Maryland.

12. Brown conversation.

13. New York City Marble Cemetery: Landmark Designation, March 4, 1969, New York City Marble Cemetery website, www.nycmc. org.

14. Colleen Iverson, director of the New York City Marble Cemetery, conversation with author, June 29, 2021. Mrs. Iverson was most helpful in explaining the efforts to reconstruct information from the cemetery’s early years.

15. Wise’s plans for relocating the remains of Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe are discussed in Louis J. Malon, “‘Then Will the Union Be Knit Indissolubly Together’: The Tomb for President James Monroe.” Athanor (Florida State University, Department of Art History) 21 (2003): 33–34. Wise was unsuccessful in his quest to bring the other two presidents to Hollywood Cemetery. The General Assembly’s appropriation is noted in the National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, James Monroe Tomb, Virginia Department of Historic Resources website, at www.dhr.virginia.gov.

16. Malon, “Then Will the Union Be Knit,” 34. While Monroe was not joined by Jefferson and Madison in Hollywood, former U.S. president John Tyler was later buried there. Confederate president Jefferson Davis and thousands of southern Civil War casualties and veterans were also interred in Hollywood, which prospered financially. For an in-depth treatment of the subject of rural cemeteries, see Jeffrey Smith, The Rural Cemetery Movement: Places of Paradox in Nineteenth-Century America (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2017).

17. “Exhumation of the Remains of President Monroe,” New York Times, July 3, 1858, 5.

18. Wolfe, Grand Civic and Military Demonstration, 80: “About three o’clock, permission was granted for the citizens assembled to enter and view the coffin, and it was calculated that about ten thousand persons, exclusive of boys and girls of all ages, availed themselves of this privilege.”

19. “News of the Week: Wednesday, November 18,” Christian Advocate, November 26, 1903, 1942 (46). A final coda came in 1903, when the remains of Monroe’s wife, Elizabeth Kortright Monroe, and one of his daughters, Maria Hester Monroe Gouverneur, were removed from Leesburg, Virginia, and buried at his side. Monroe’s other daughter, Eliza Monroe Hay, died in Paris, France, and is buried in that city’s Père Lachaise Cemetery.

20. “Restoration of Monroe’s Beloved ‘Birdcage’ Complete,” A Gateway into History: Friends of Hollywood Cemetery Newsletter 7, no. 1 (Spring 2017):1–2; Kirsten Moffitt, “Finishes Analysis Report, Monroe Tomb: Select Fragments,” February 28, 2016, report prepared for W.E. Bowman Construction. The author thanks Fred Garrett of Bowman, co-manager of the restoration project, for providing photographs and a copy of Moffitt’s report to the James Monroe Museum.

51 white house history quarterly

SCOTT HARRIS

SCOTT HARRIS