WHITE HOUSE WAX

81 white house history quarterly

Discovering

Th e Wh ite House Record Library

OPPOSITE: JOHN CHULDENKO

JOHN CHULDENKO

THE WHAT? that’s typically the response I get when I tell people there is a collection of vinyl records at the White House, and it’s almost always accompanied by an incredulous look. But it’s true, and I am one of the only people to have ever laid eyes on it.

The White House Record Library originated as a way for the president of the United States and the first family, in their most private, personal moments, to connect with the American people through music. It was intended to serve as a living repository that would evolve and grow as our country changed and our culture shifted, a record collection as diverse as the American people themselves, installed in the White House Residence.

I never lived there, but my uncles did. More than thirty years ago, my mother married President Jimmy Carter’s eldest son, Jack. And along with that marriage came two new siblings, a handful of aunts, uncles, and cousins, and an explosion of incredibly unique opportunities, many taking place on family vacations.

Several years ago, on one of those family vacations, I was talking with my uncle Jeff who told me about a party he had one night. His parents (my grandparents President and Mrs. Carter) were hosting a dinner downstairs at the White House. Jeff and his friends had decided they’d prefer a more relaxed setting—the glass Solarium upstairs

that overlooks the Washington Monument. It’s often used as a place where the first family can relax and unwind, and that’s exactly what Jeff and his friends were doing—hanging out, having fun, and, like most young people, blaring music, specifically the Rolling Stones’ Goats Head Soup At full volume. My uncle heard neither the door open nor the entrance of his mom, the first lady, and Joan Mondale, the wife of the vice president. Their arrival coincided precisely with one of Mick Jagger’s less “family friendly” choruses, a reprise of vociferated profanity. Over and over.

As Uncle Jeff put it, “Mom and Mrs. Mondale did not stay and hang out.”

After Jeff finished his Stones story, and as the laughter subsided, I asked Jeff and my Uncle Chip where they got the records they listened to upstairs. He said that if you wanted a record right away, someone would get it for you, but there was also a collection of LPs up there.

Wait. A What?

And that’s where this whole adventure started.

In the early days of the Nixon administration, the Recording Industry Association of America, learning of a book library donated to the White House by the American Booksellers Association, offered to provide the White House with a collection of recorded works—music and spoken word.

When John Chuldenko’s uncles Chip and Je Carter shared their memories of listening to White House record albums, he began a quest to locate the collection. Chuldenko is seen here (standing far right) with the Carter family during a visit to the Dolphin Research Center, 2017.

82

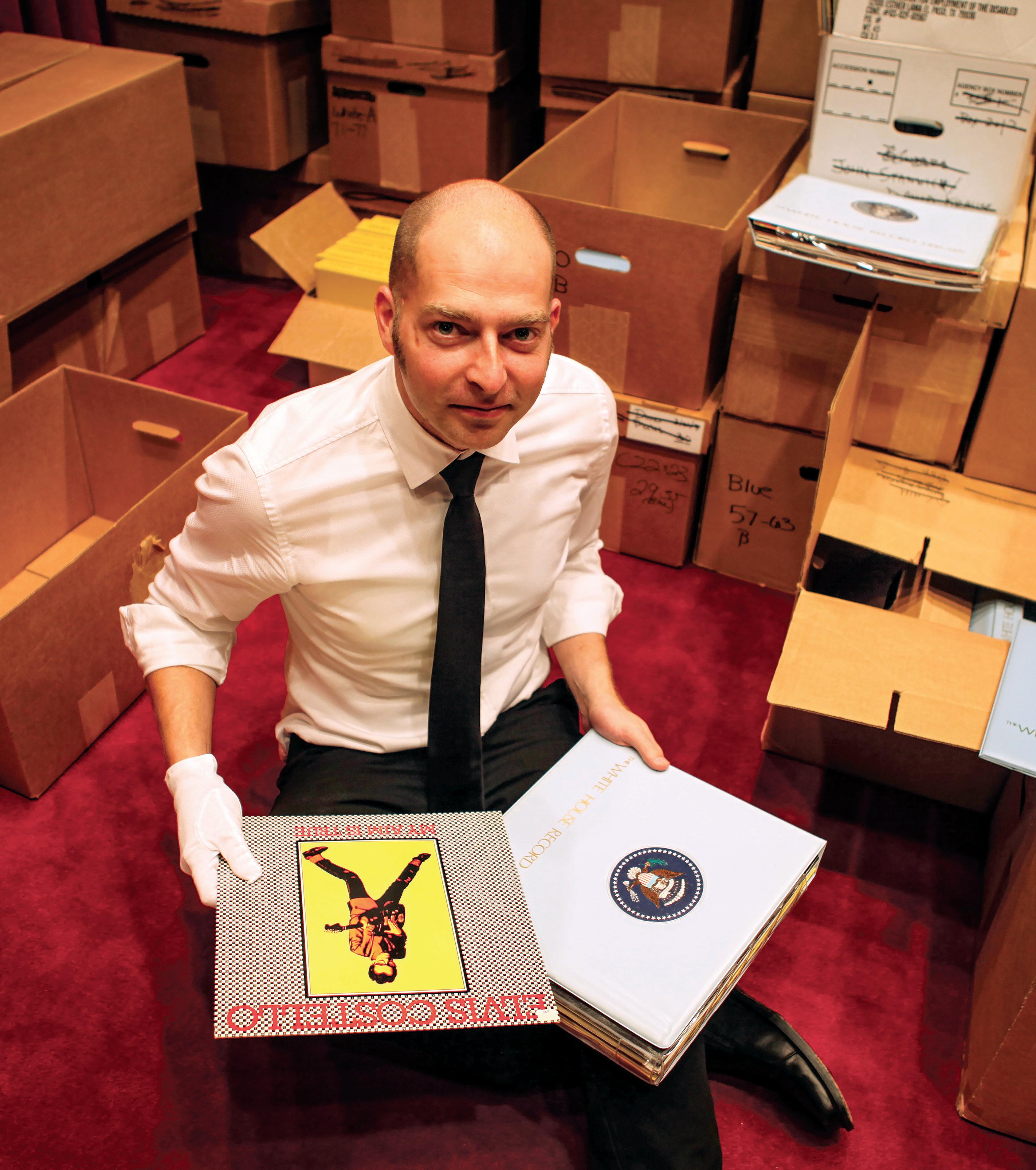

previous spread John Chuldenko sits in the White House Movie Theater surrounded by storage boxes holding the White House Record Library, 2011. above

white house history quarterly DOLPHIN RESEARCH CENTER

above

This collection, along with a turntable and stereo system, would be provided as an official gift to the White House.

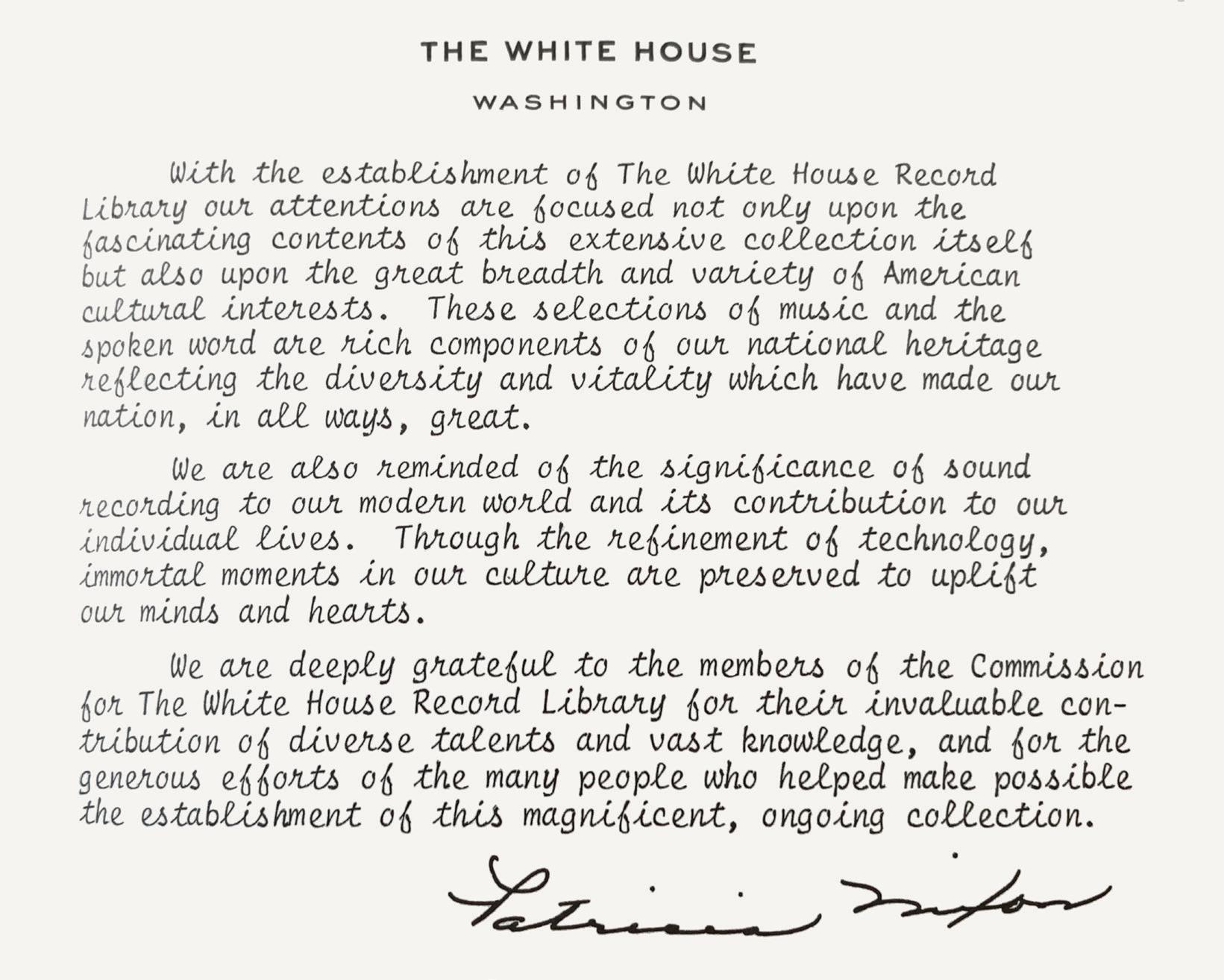

Mrs. Nixon approved a special commission to select the recordings. Each distinguished committee member was chosen for his or her knowledge of a specific genre—Classical, Jazz, Country Folk and Gospel, Spoken Word, and a Popular music genre. This category included rock and roll and was curated by legendary composer and lyricist Johnny Mercer.

The commission began work in the spring of 1970, deliberating among themselves and consulting with advisers of their choosing. While each curator selected the records in his or her assigned genre, final selections were brought to the full commission for approval. Their focus was to curate a comprehensive collection representative of the American cultural tastes over the years. While most of the selections were from American record labels, and most of the performers were American, exceptions were made for foreign performers who significantly impacted American culture.

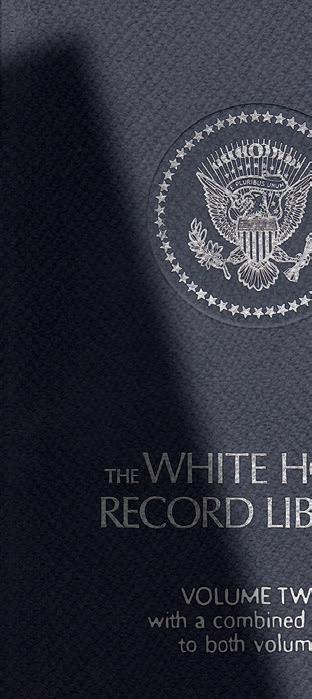

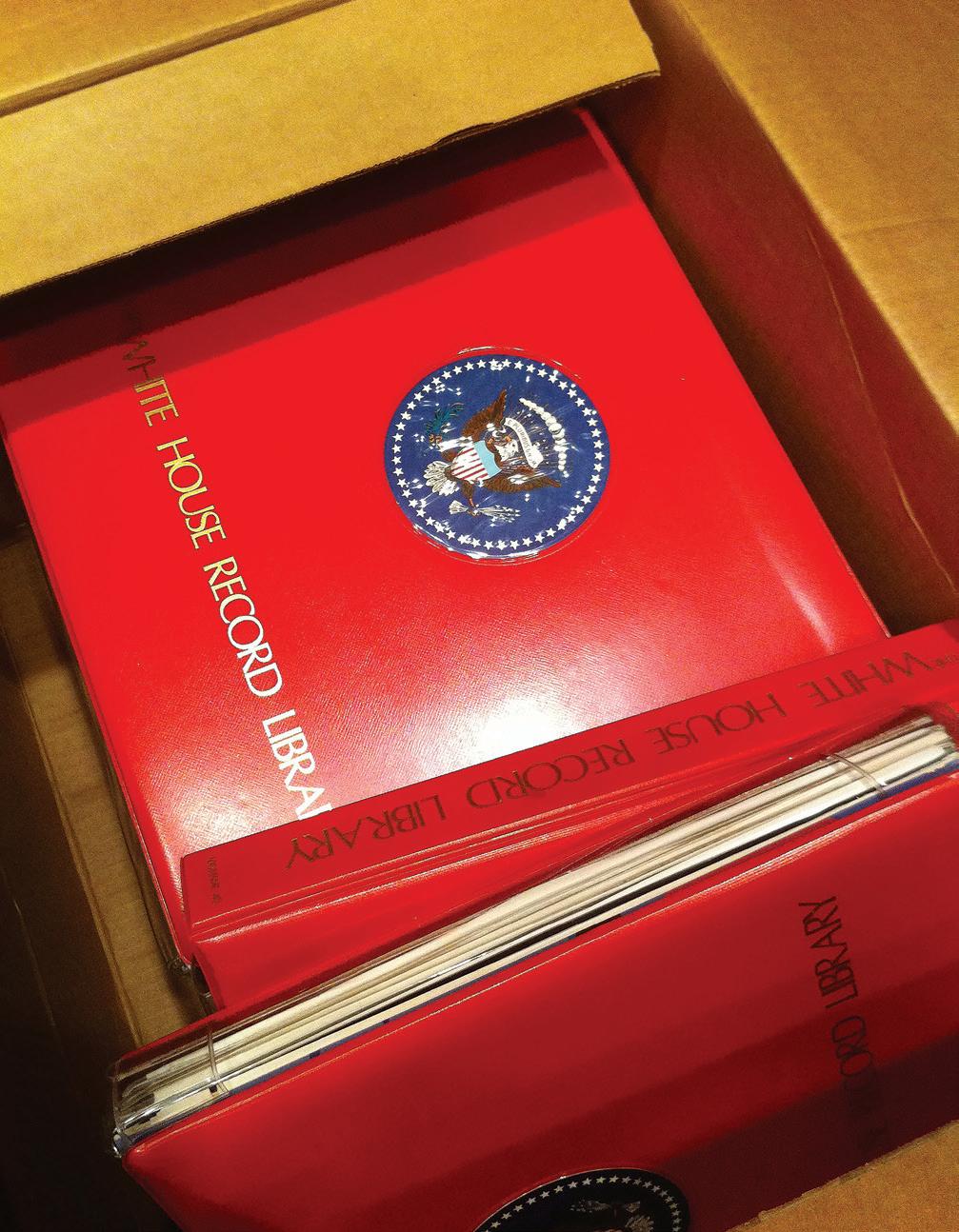

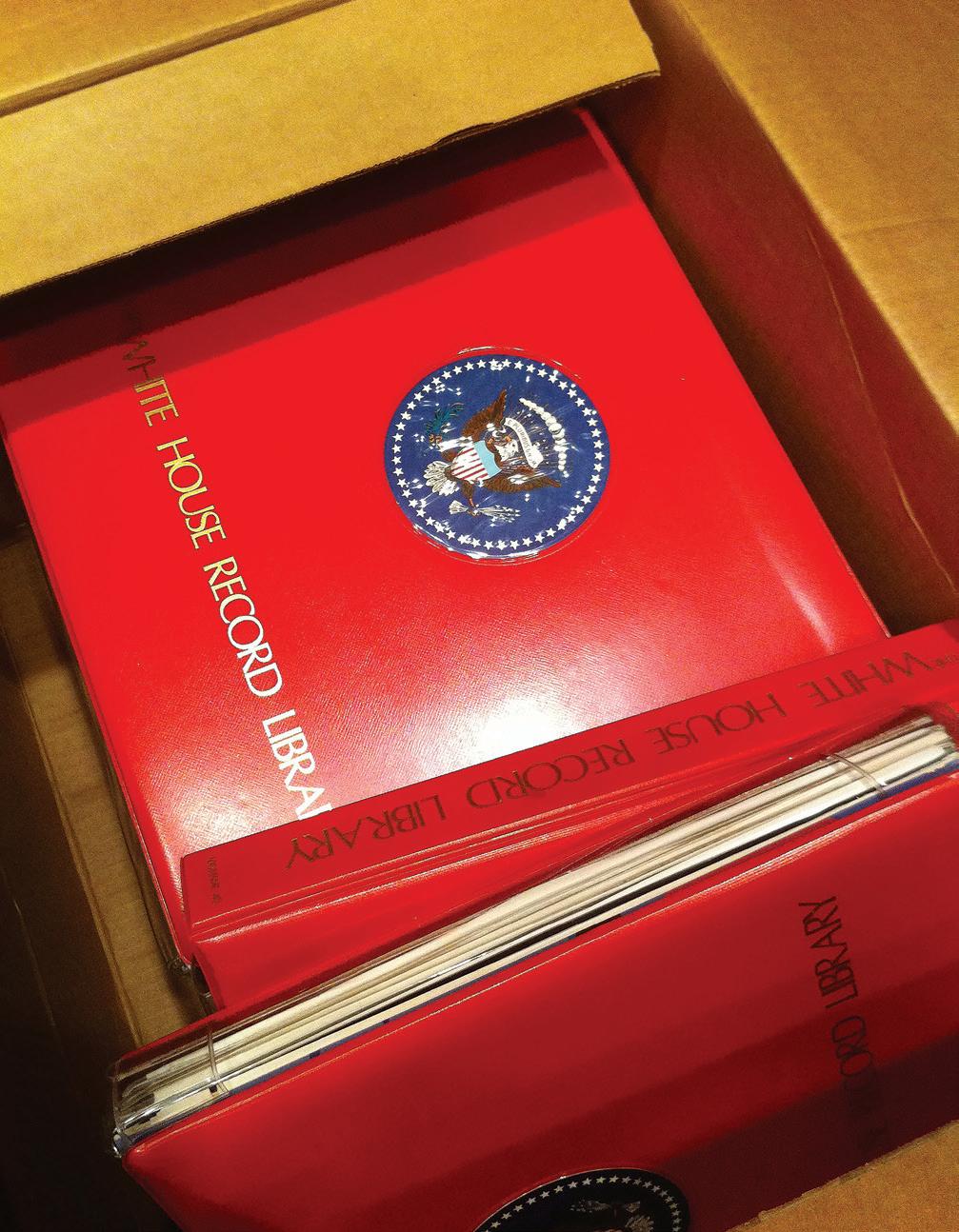

Commission members limited the collection to two thousand LPs, a number they felt could be stored upstairs in the Private Quarters of the White House, where it could be easily accessed and enjoyed by the first family. The records themselves were sourced and collected in vinyl folders, each color-coded according to genre and embossed with the Presidential Seal. Below the seal is gold embossing that reads, “The White House Record Library.” If I haven’t made it clear earlier, it’s the coolest record collection ever.

It was the intention of the commission that the record library be updated periodically so that it would continue to reflect the changing tastes of the American people. And it was. Fast forward to 1979.

It’s important to pay special attention to the popular selections within the record library, not only because they may, by a very general definition, most accurately reflect the tastes of the American people at the time but also because it was these selections that played a large part in the decision to convene a new commission and curate Volume Two of the White House Record Library. In his introduction to the Popular music category in Volume One, Johnny Mercer wrote this:

Well, out of all the songs since records have come into being, we have tried to pick a representative cross-section of the songs and singers that America loved best, the favorites of their own eras—“the legends in their own time.”

You’ll nd many of your favorites in here and you’ll dispute some of the choices, no doubt. But compared to overall output, they shine like stars in the night, like jewels in the red clay.1

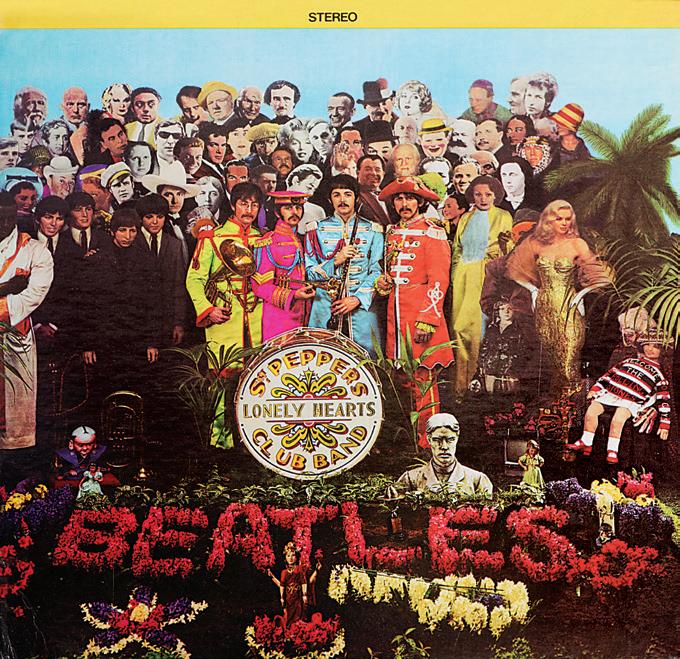

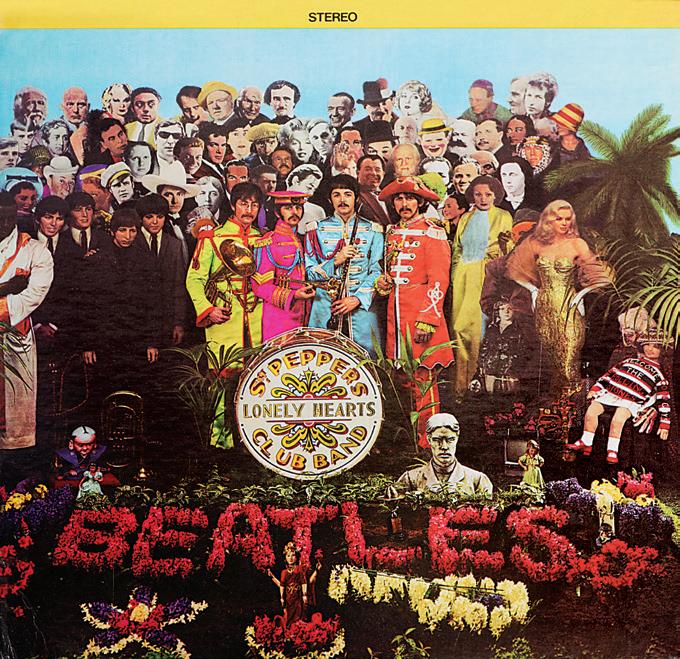

This prescient introduction acknowledges that there will likely be omissions and inclusions some may disagree with; after all, that’s the beauty of music. Notably absent from Volume One is Stevie Wonder and Jimi Hendrix. The Beatles are represented only by Meet the Beatles and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. I mention these omissions only to illuminate the fact that curating such a collection is no easy task, and it was the omissions that eventually led to Volume Two of the White House Record Library and one of the most comprehensive collections of its time.

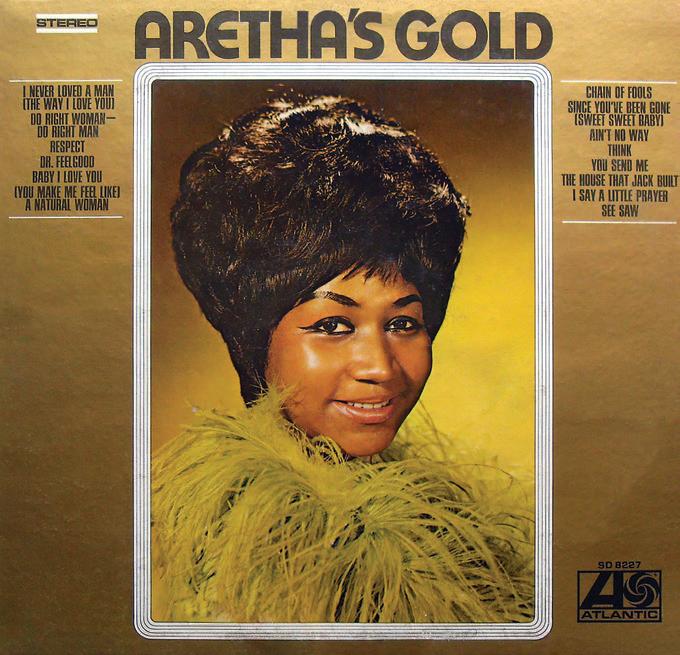

In 1979, when a new commission was formed to update the collection, it was chaired by legendary record producer John Hammond—probably

83 WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

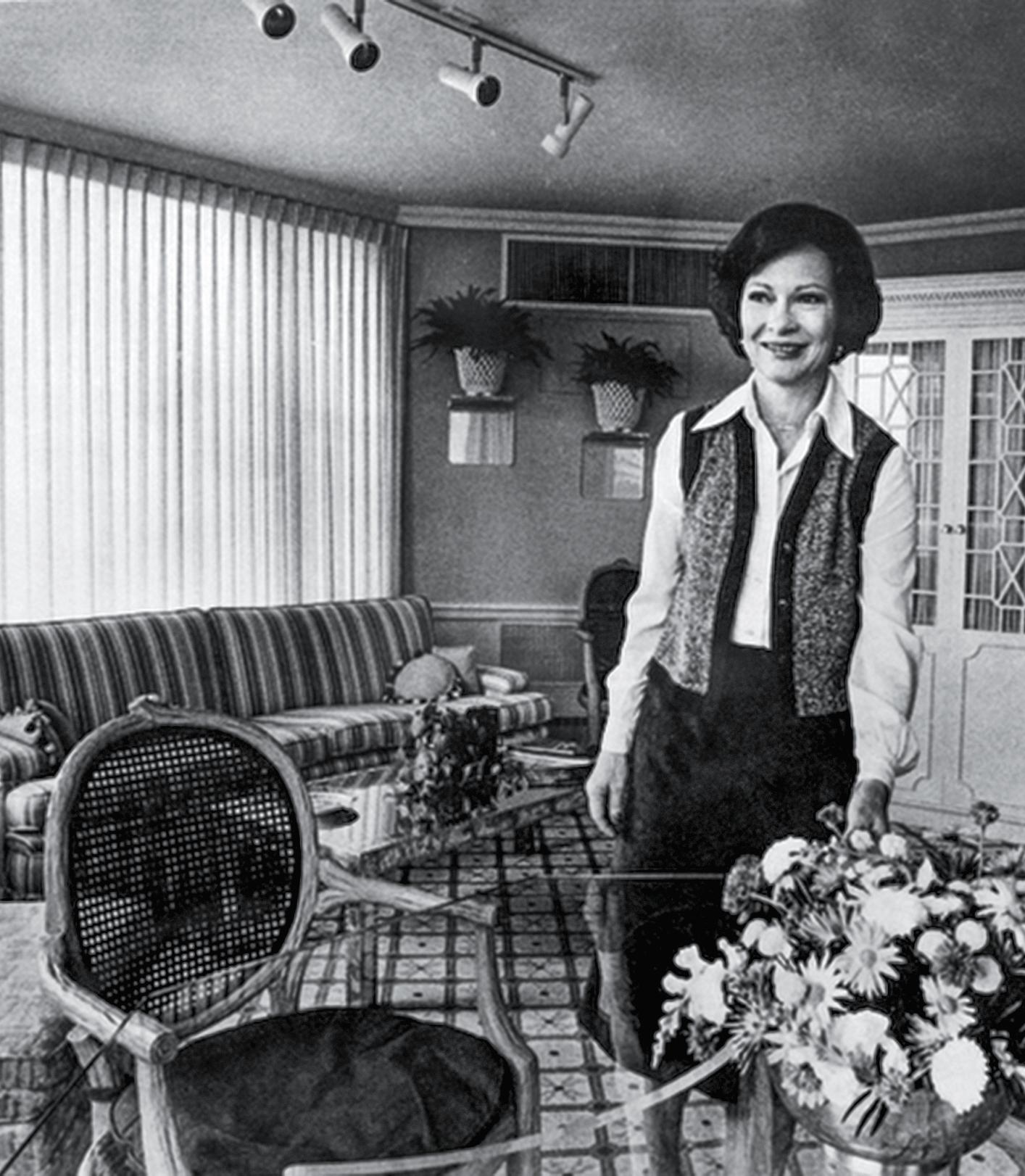

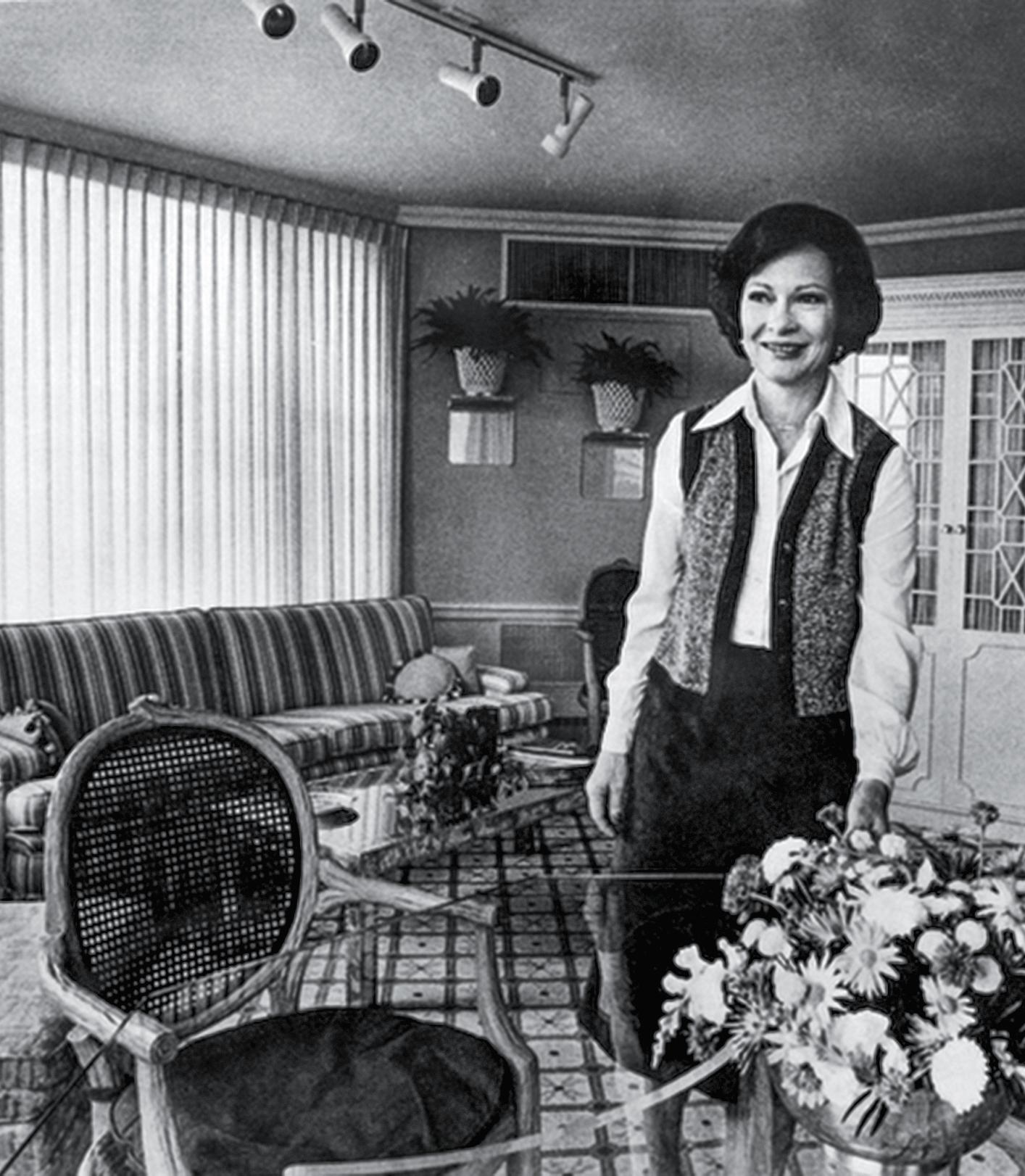

First Lady Rosalynn Carter in the White House Solarium, a comfortable room for family relaxation where record albums were enjoyed.

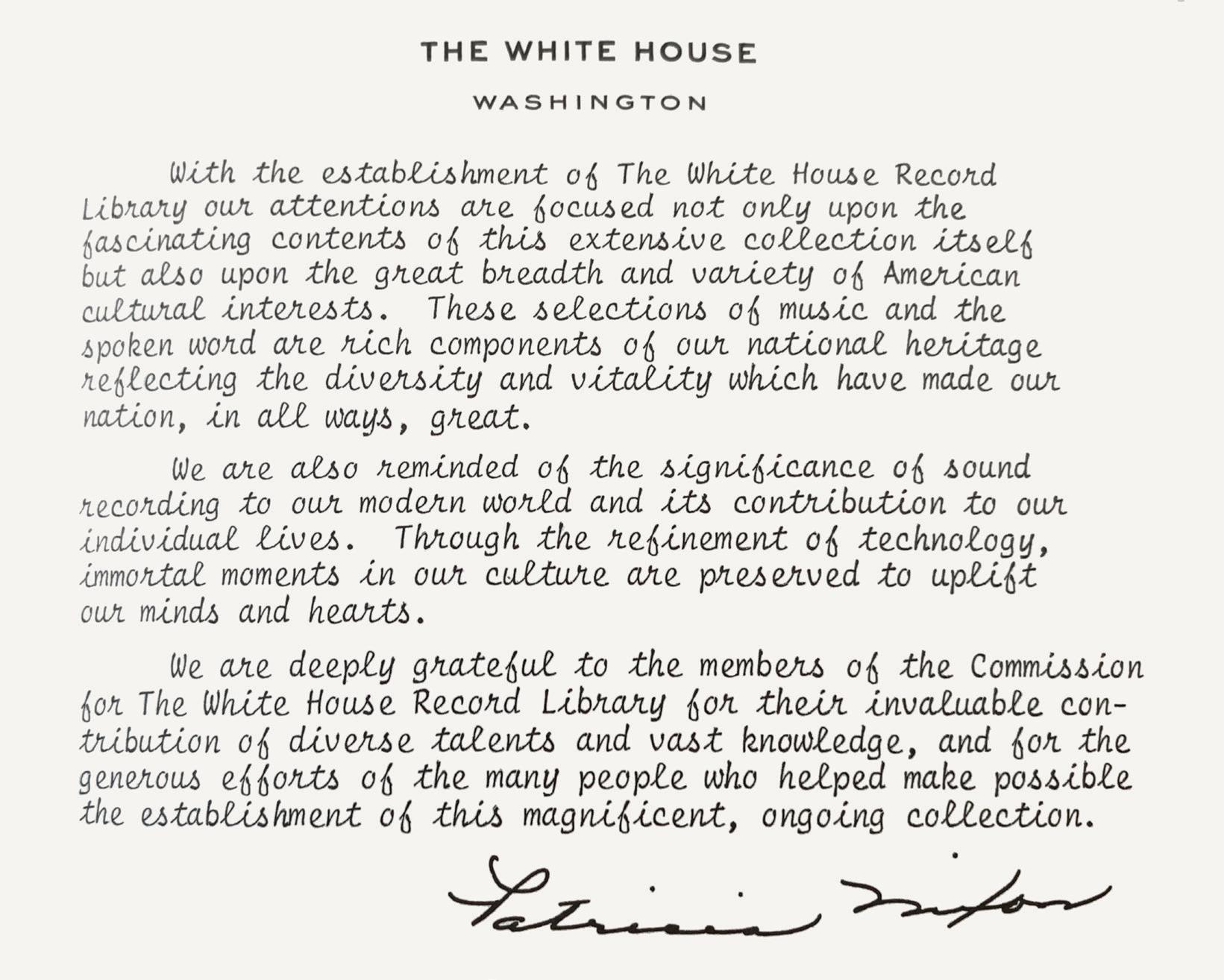

First Lady Pat Nixon, seen above meeting with original members of the Commission for the White House Record Library, explained the purpose and the signi cance of the collection in her introduction to the rst volume of the White House Record Library. Published by the White House Historical Association in 1973, the book listed the two thousand albums in the collection. A second volume followed in 1979.

84 BOTH IMAGES:

white house history quarterly

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

known best for discovering Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen. The Classical selections in Volume Two were chosen by David Hall; Ed Bland curated the Rhythm-and-Blues, Blues, and Black Gospel selections, while the Country, Folk, and White Gospel category was handled by Frances Preston. John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet selected the Jazz albums, and the Spoken Word albums were selected by Paul Kresh. The categories of Popular music and Latin and Contemporary selections fell to a young Bob Blumenthal, then contributing editor of the Boston Phoenix and contributor to Rolling Stone, along with a team of trusted advisers.

Energized by the fact that my grandfather is a true music lover, with tastes ranging from Mozart to Willie Nelson, Hammond and his team set to work on expanding the collection. Blumenthal and his advisers took the opportunity to fill in several gaps in the Popular category. This was rock and roll, after all, and Blumenthal felt liberated to select works that at first might seem controversial for such a prestigious library. He wrote in his introduction to the Popular music selections:

If the music at times seems crude, brash, and preoccupied with the unspeakable and intimate, it is also bold, assured, self-con dent, vulnerable, visionary—a peculiarly American synthesis which has been heard and is now created internationally.2

The 1979 update included calls to revolution, biting satire, songs of redemption, and punk rock anthems. This, to coin a phrase, was not your forefather’s record collection.

I’ve spoken at length with Bob Blumenthal about his involvement in the White House Record Library, and he found the opportunity to curate a record library for the president and first family thrilling. “I looked at the first family as representative of America. That I was picking a record library for America,” Bob recalls. “There was a notion that maybe the kids would introduce their parents to some music or the parents would overhear the kids playing some music. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if a president found any musician in any style because the recording was in the White House Record Library? That’s the impact I want to have.”

Once the selections were finalized, the plan was to present the updated Record Library to the

president and first lady at the White House. But after the outcome of the 1980 election, the clock was ticking, and the push was on to make the presentation before President Carter left office. The commission arranged to meet and present the records at a small ceremony on January 13, 1981, a week before Ronald Reagan was to be inaugurated. “I remember bleachers were being set up on Pennsylvania Avenue and there were moving vans outside the White House when we arrived because things were being packed up and moved,” Bob recalls. Greetings were exchanged, and photos were taken, but the records themselves weren’t actually there. Neither Bob nor anyone else, for that matter, had ever seen these albums. And it would stay that way for almost thirty years.

After that night with my uncle, I couldn’t get the idea of an official White House Record Library out of my head. I started researching. Surely something as monumental as a record collection compiled for the president of the United States would be documented, publicized, a matter of common cultural knowledge. It was not. There was next to nothing about it at all. Internet searches revealed only the two reference catalogs published by the White House Historical Association (publishers of the title you hold in your hands), a mention or two in Billboard Magazine, and an article by David Browne featured in a 2009 issue of Rolling Stone magazine. But that was enough. That was a start. All I needed was a name, a place to begin. So I contacted my grandparents’ office to see if there was any info on the collection at the Carter Presidential Library in Atlanta.

I got one number. Keith Schuler, an archivist at the Carter Center, said he would reach out to the White House on my behalf and see what he could find. I thought that surely after thirty years no one would remember a bunch of dusty vinyl records once stored in the Residence. But a few days later, Keith e-mailed back with the subject line “Success!” At the time, the curator of the White House was Bill Allman, and on his staff was Monica McKiernan, who agreed to take my call.

Taking a deep breath and stifling my mile-aminute excitement, I explained the collection to Monica. While the Office of the Curator had no direct knowledge of the collection, Monica said she’d get back to me. Again, this is where I thought my journey would come to an end. But it didn’t. The gods of vinyl were smiling on me, and a few days

85

white house history quarterly

86 ALAMY white house history quarterly 86 ALL IMAGES THIS SPREAD: ALAMY white house history quarterly

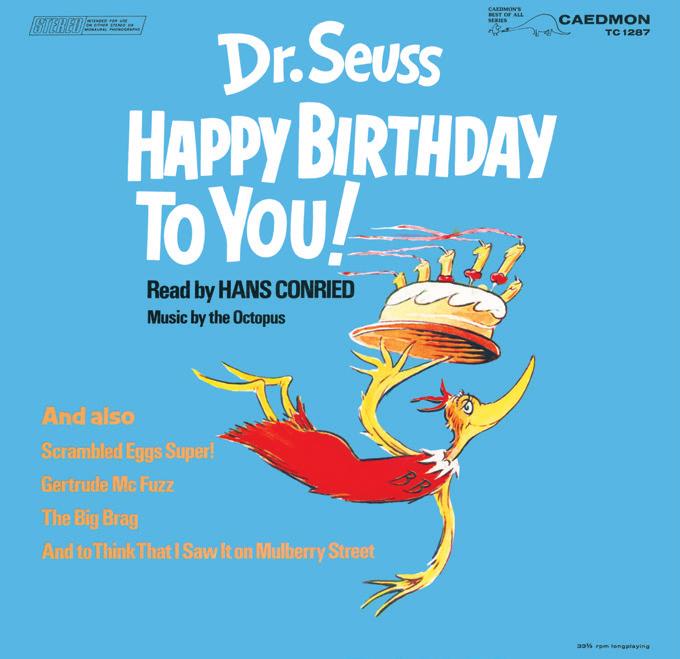

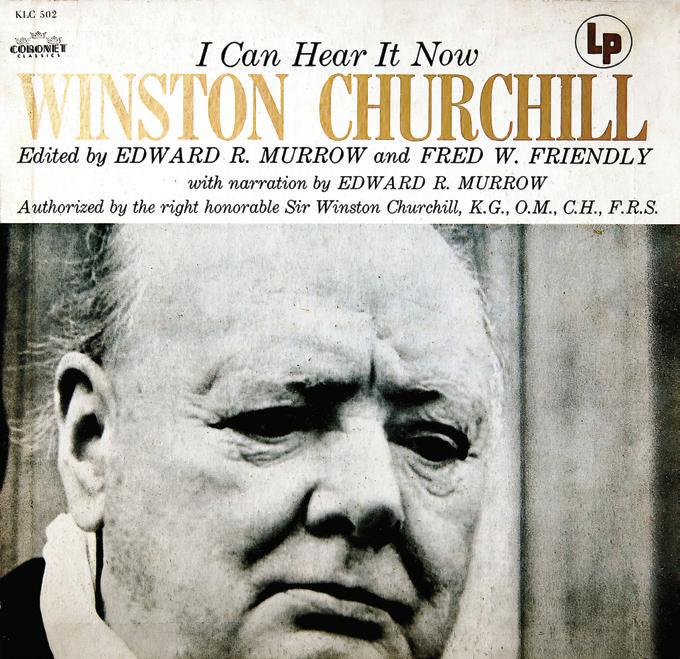

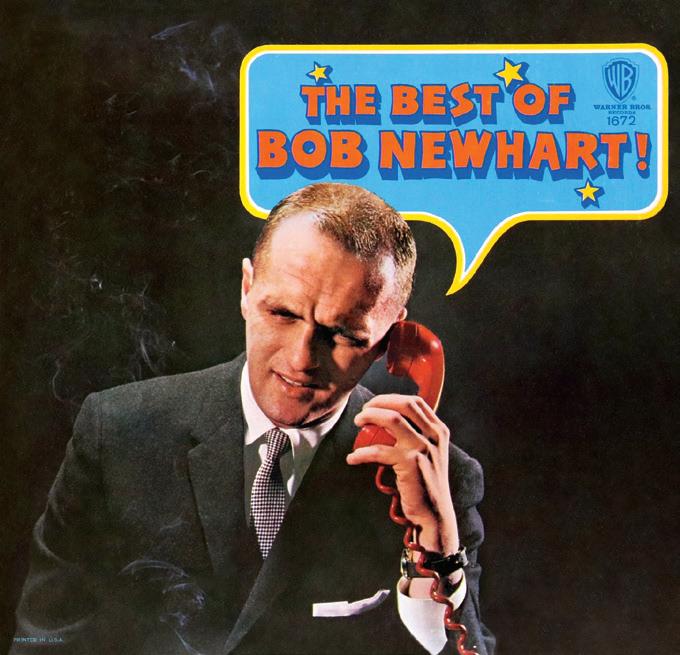

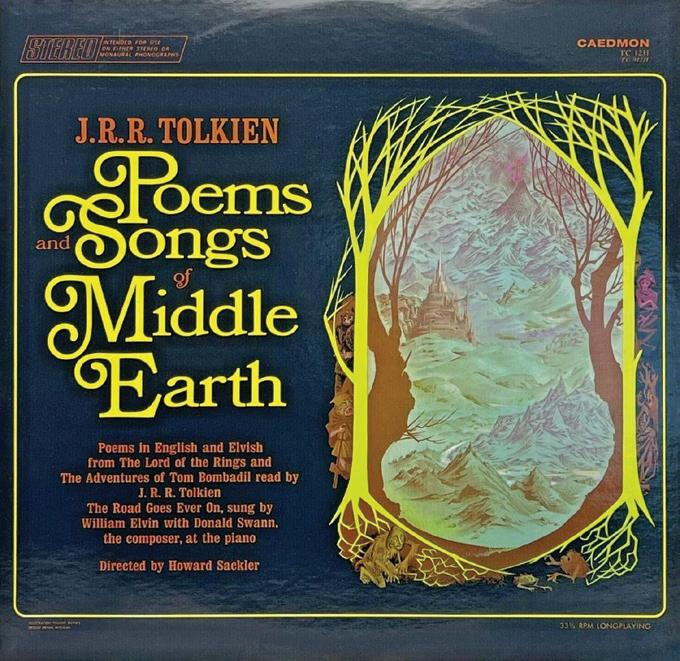

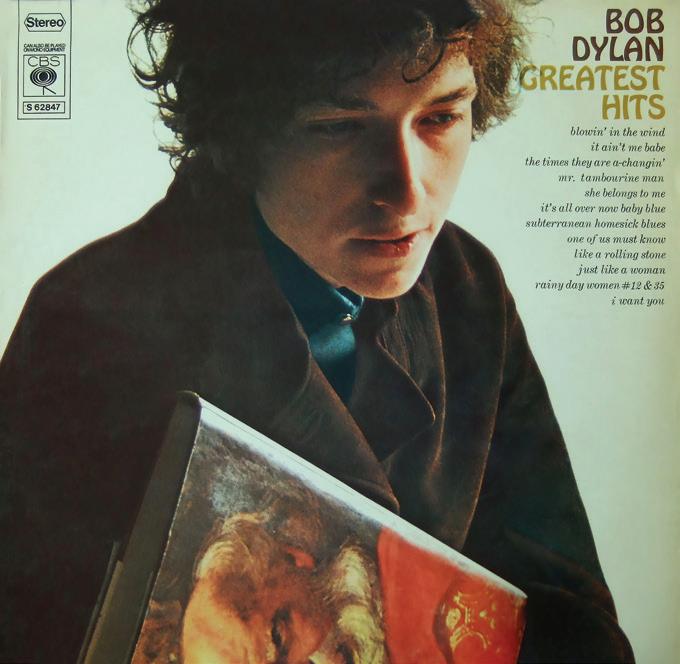

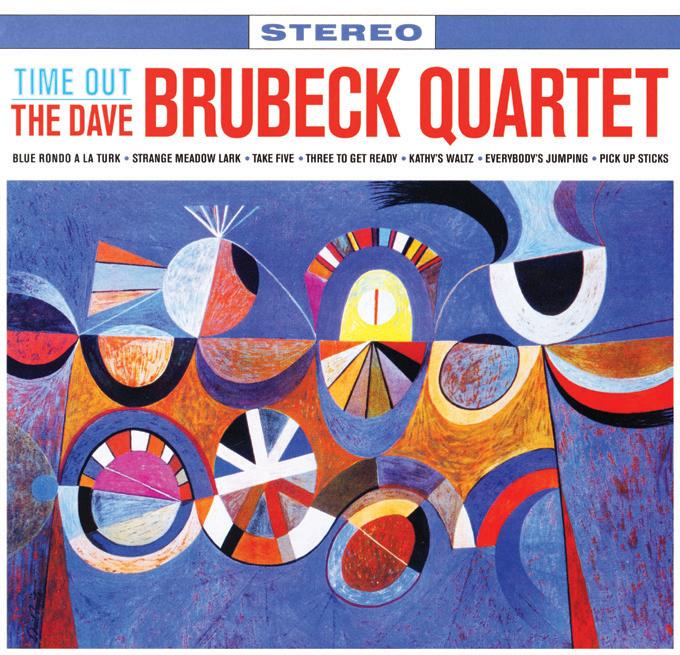

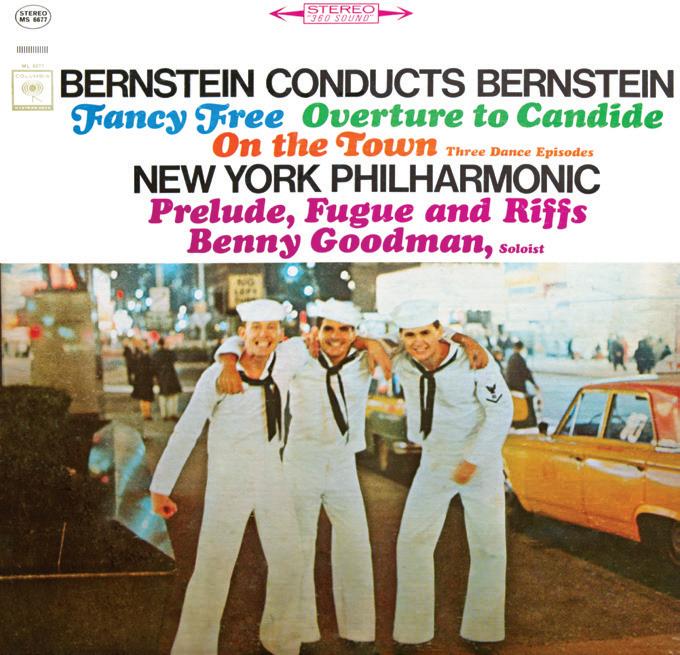

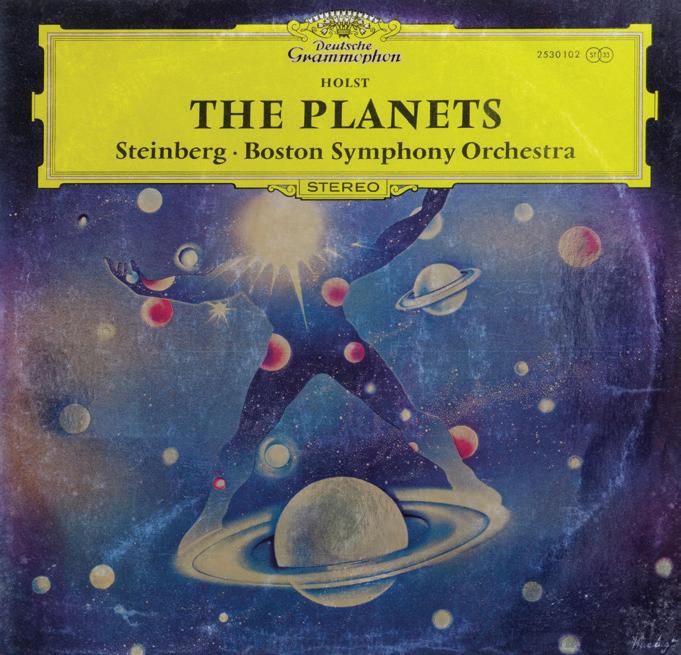

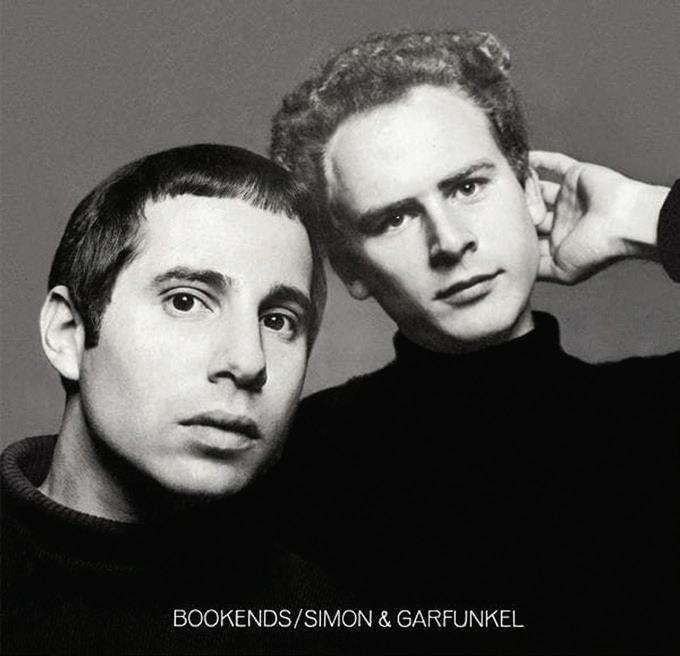

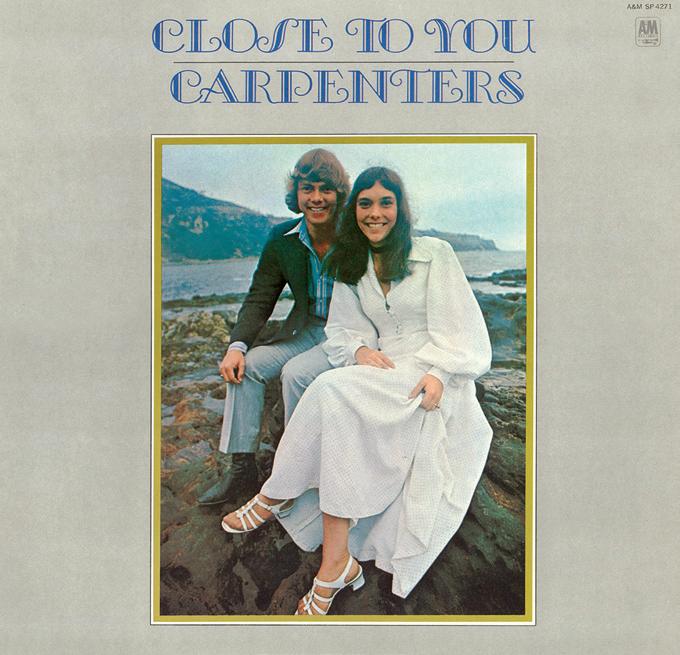

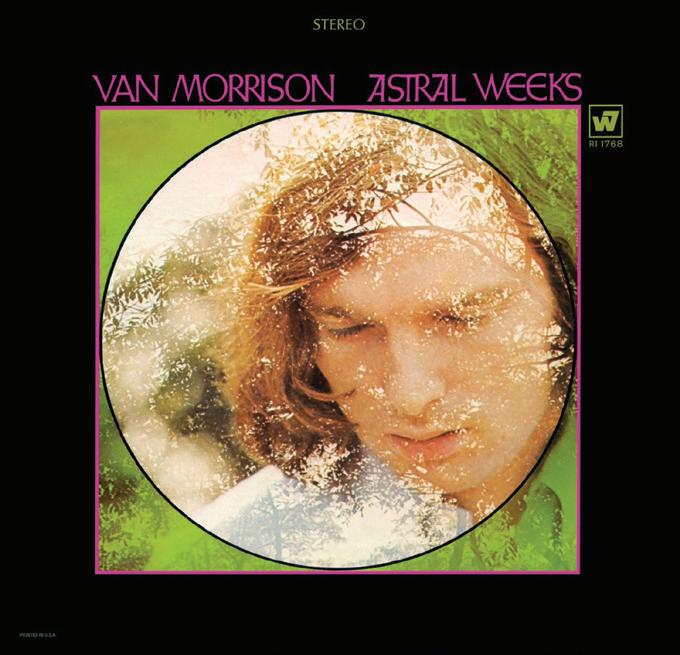

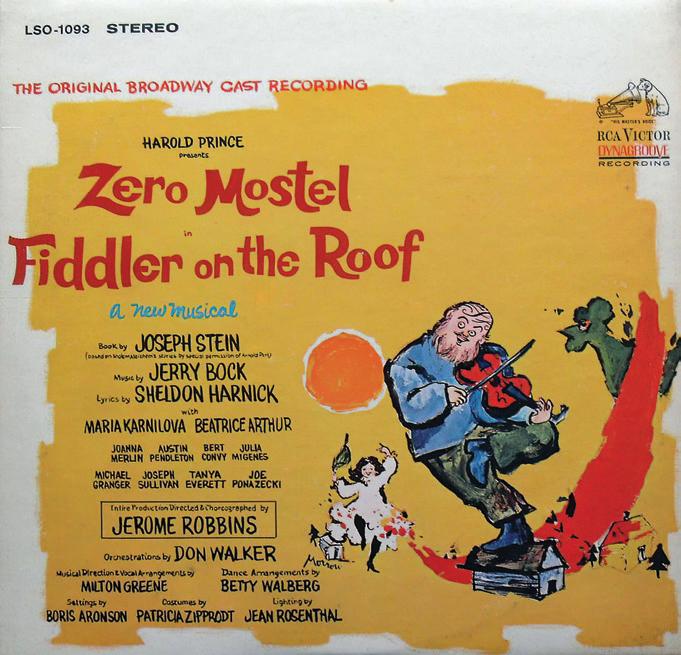

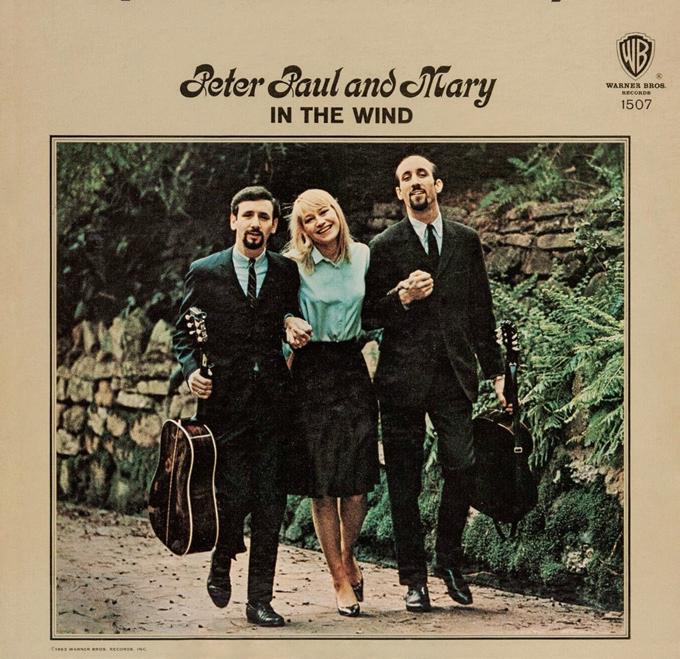

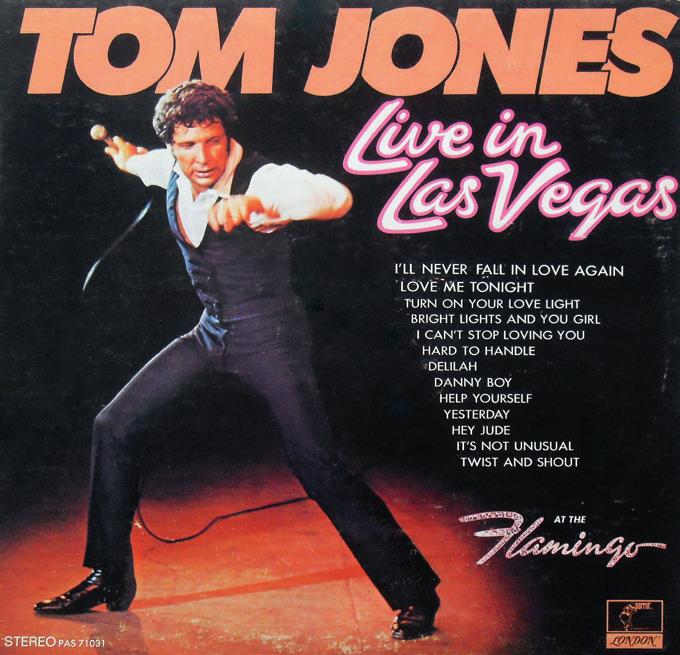

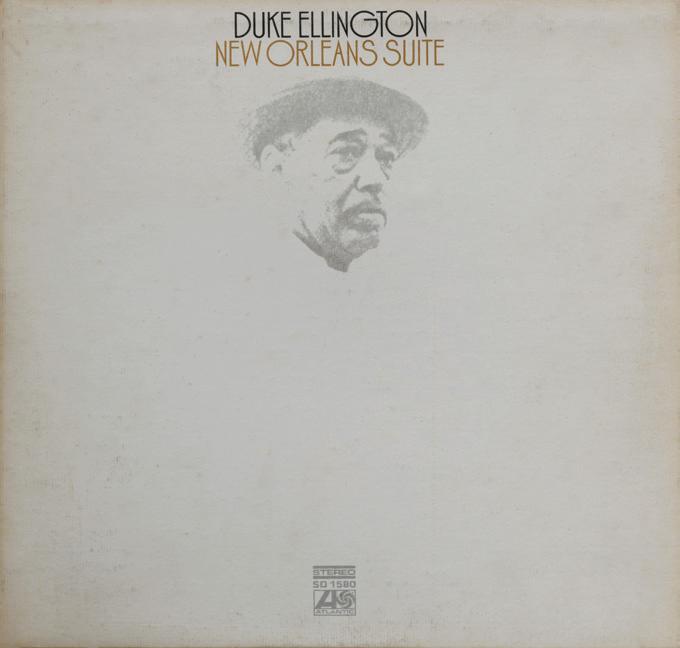

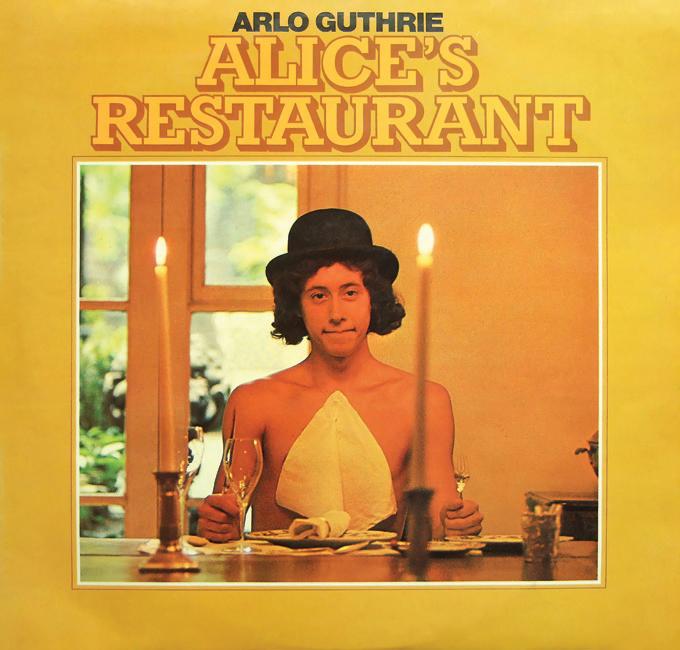

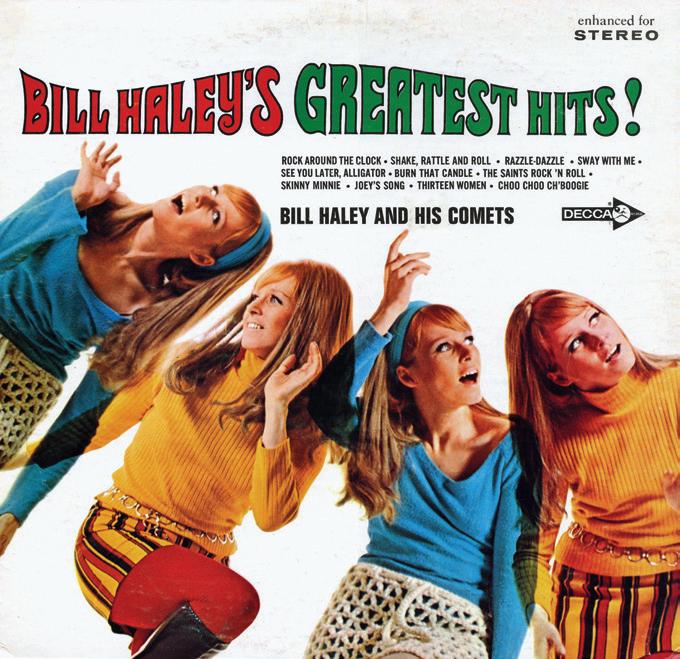

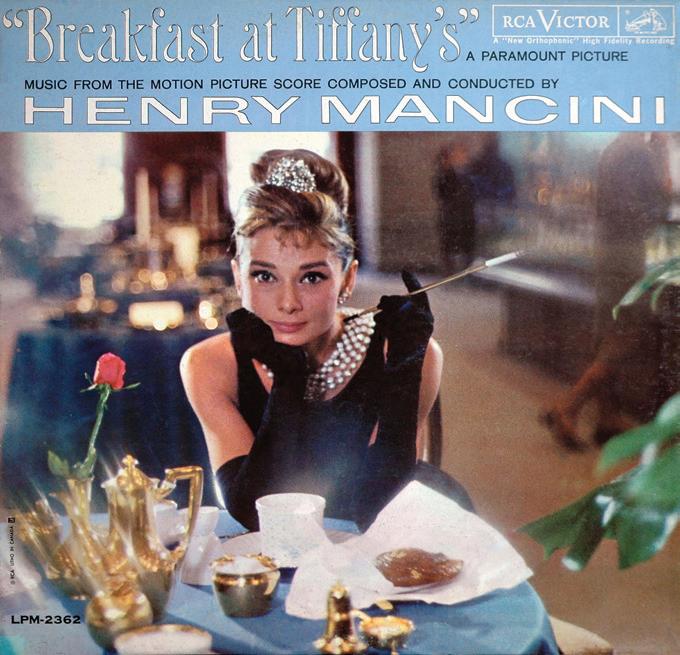

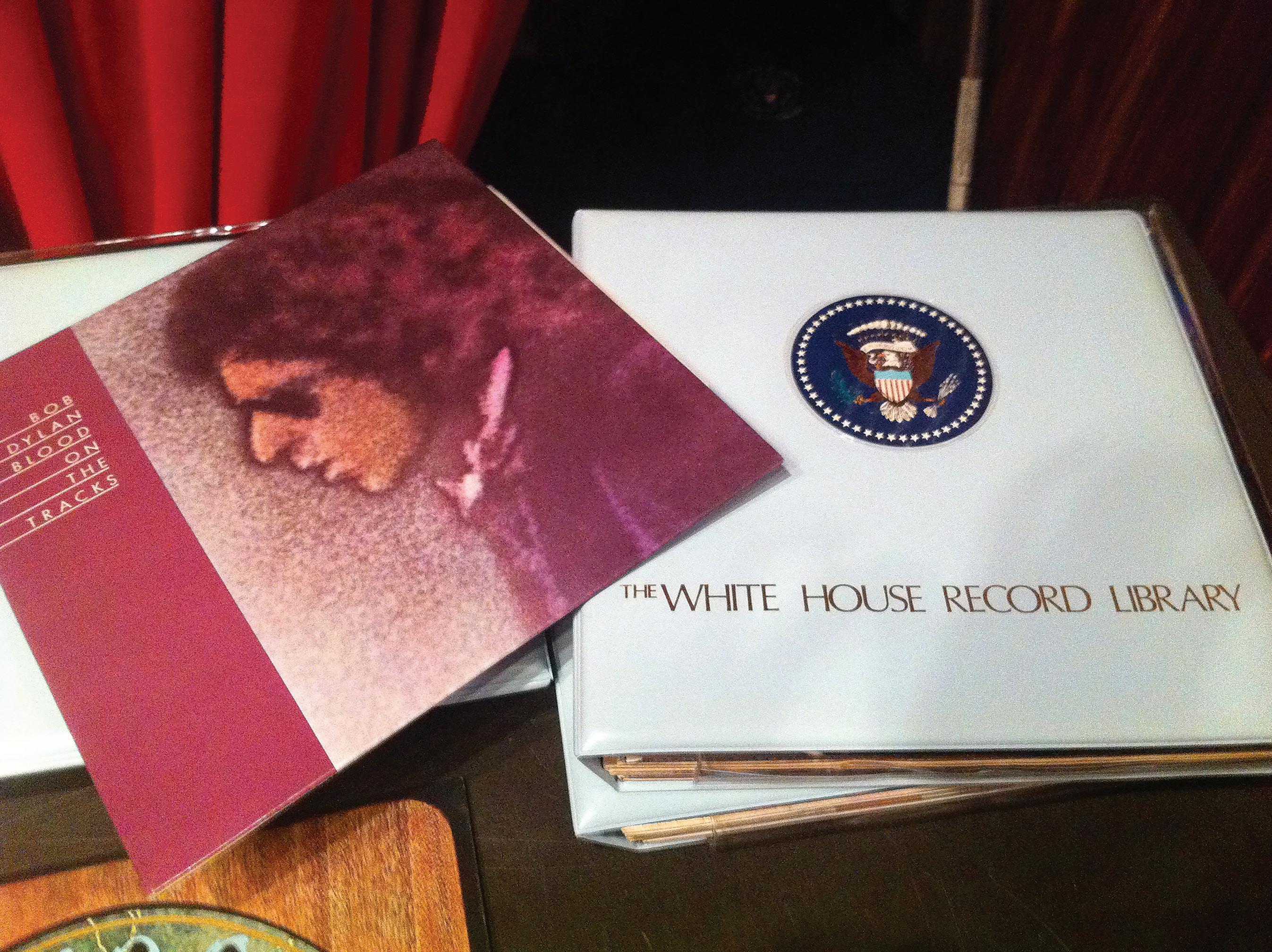

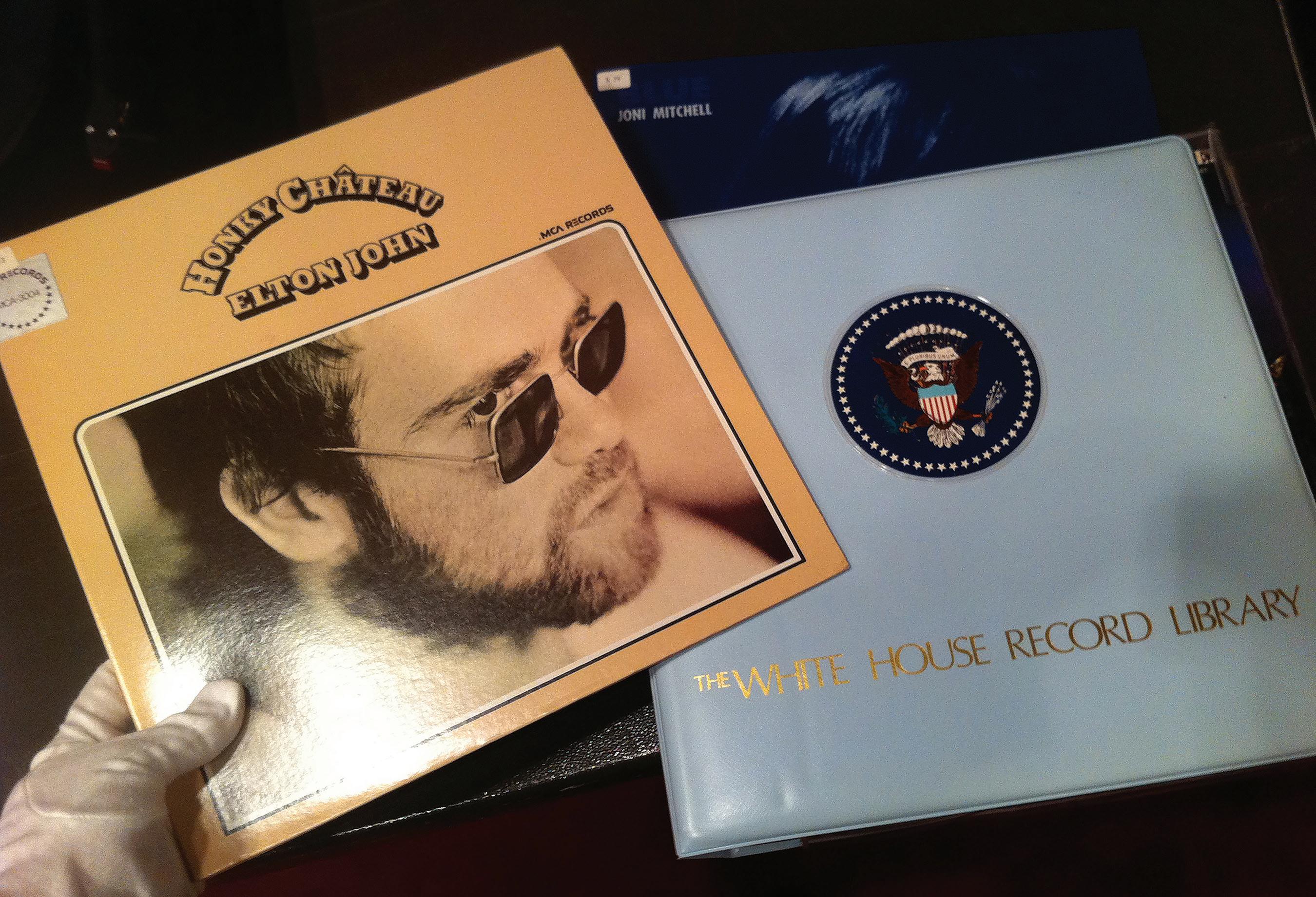

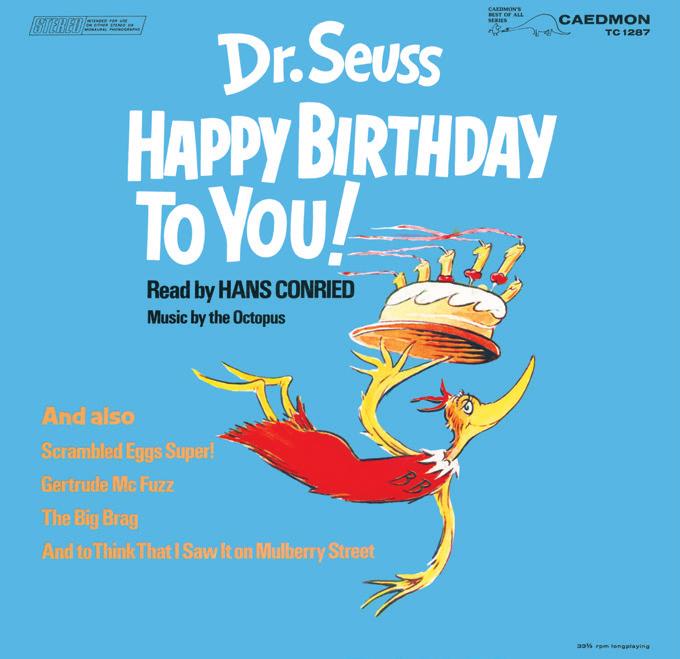

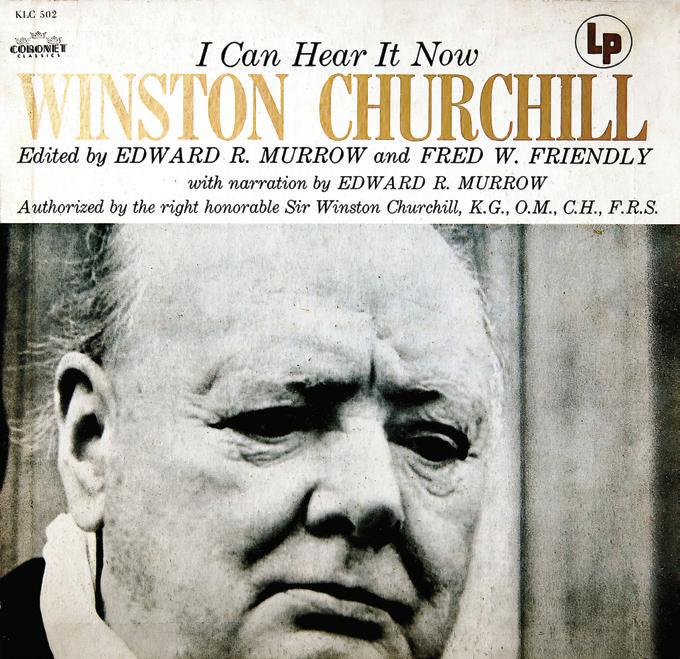

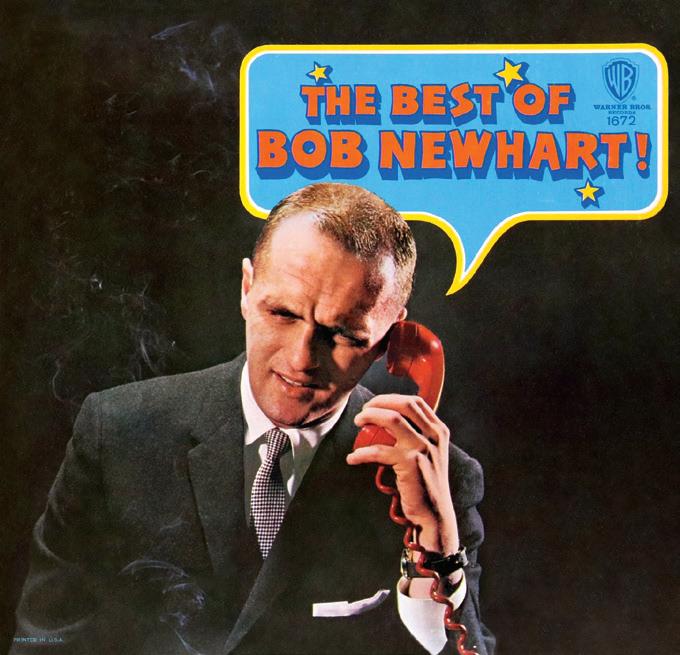

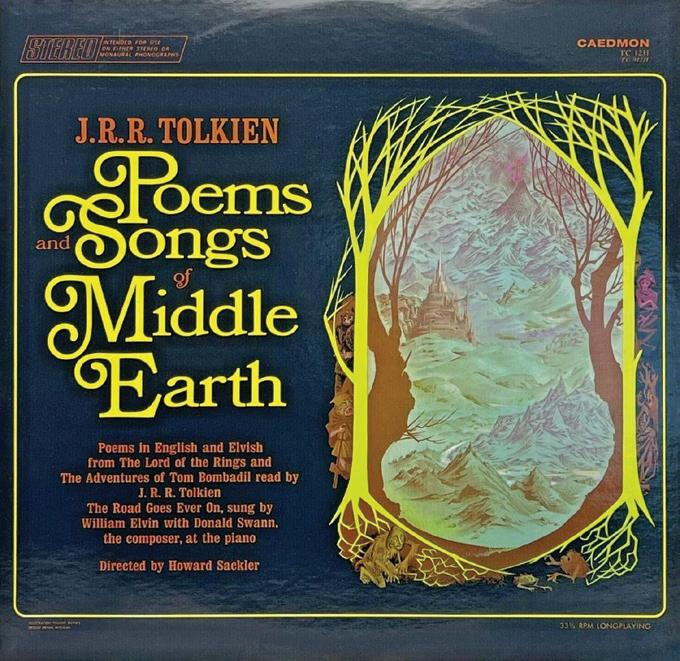

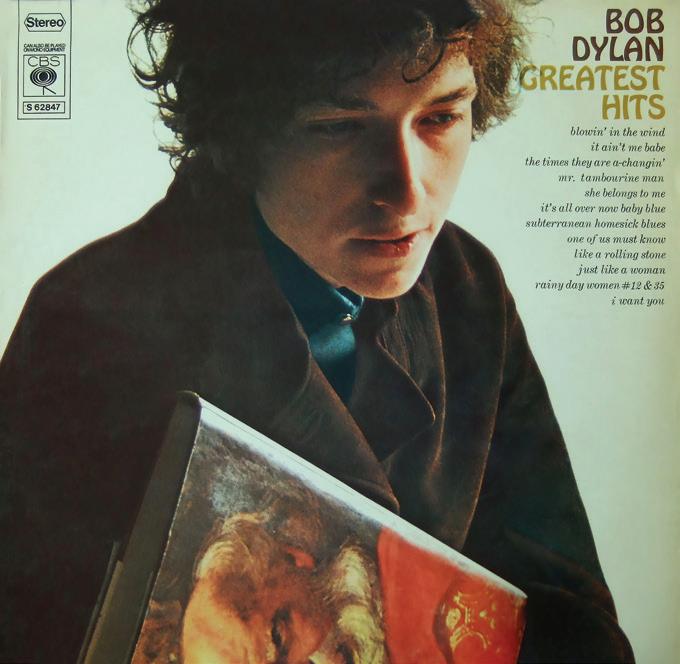

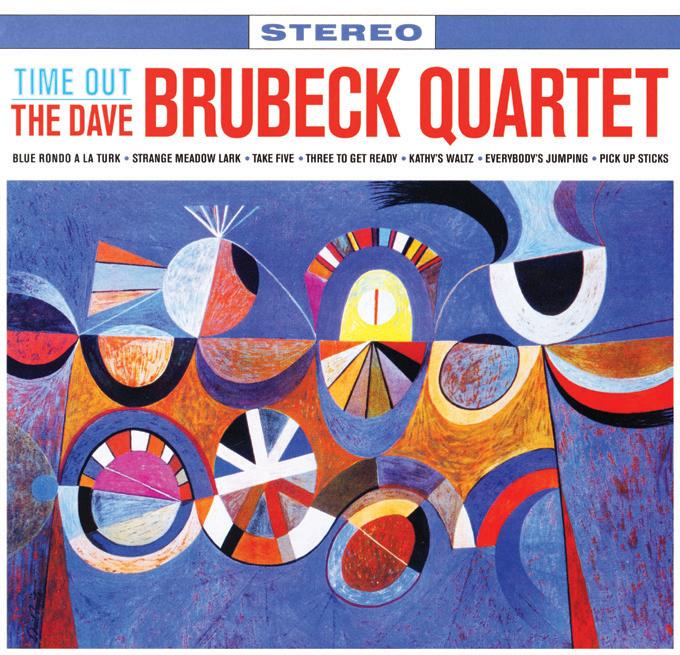

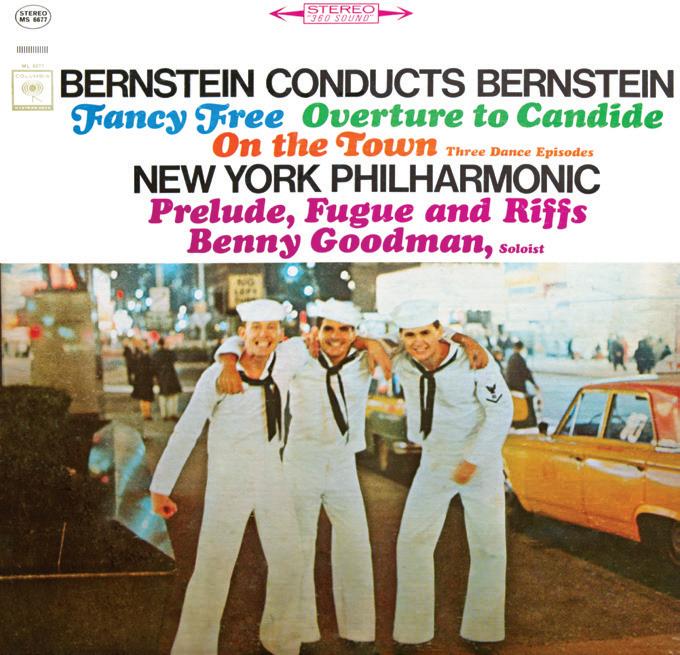

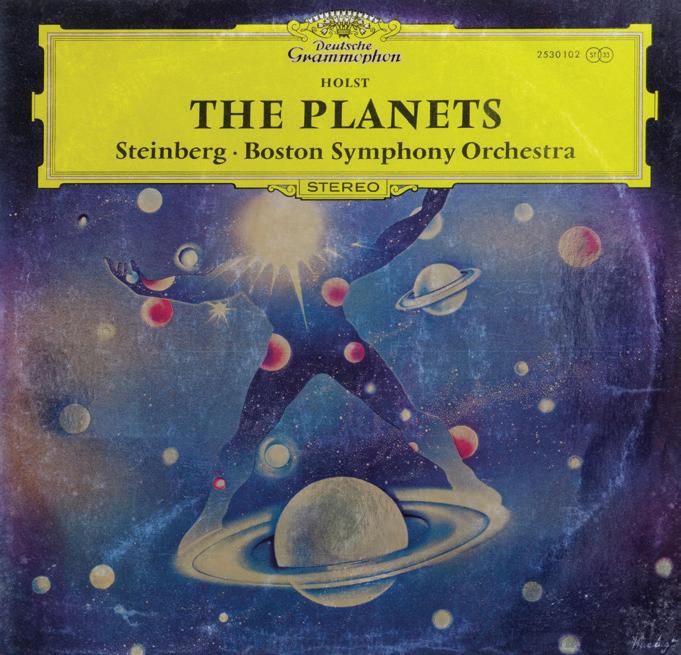

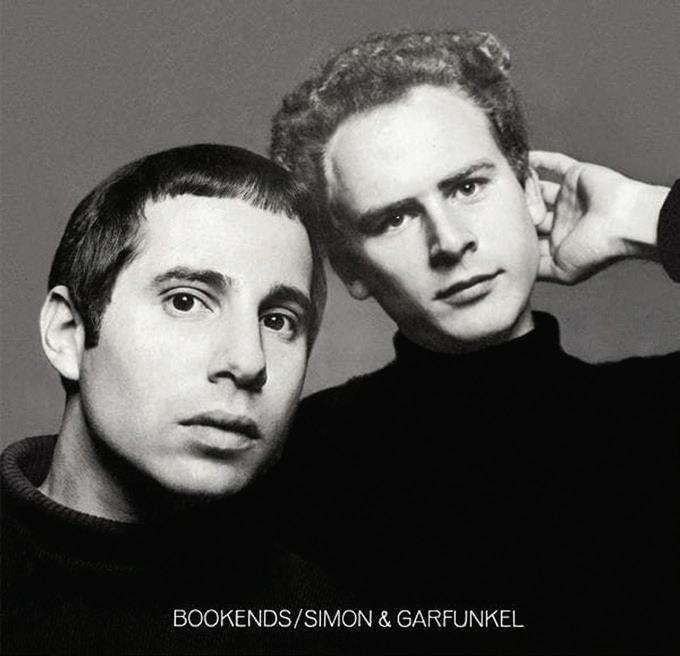

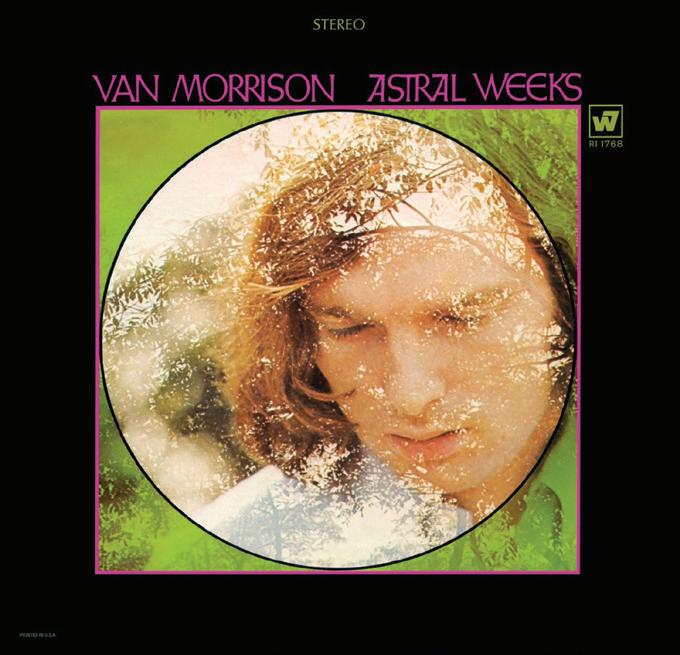

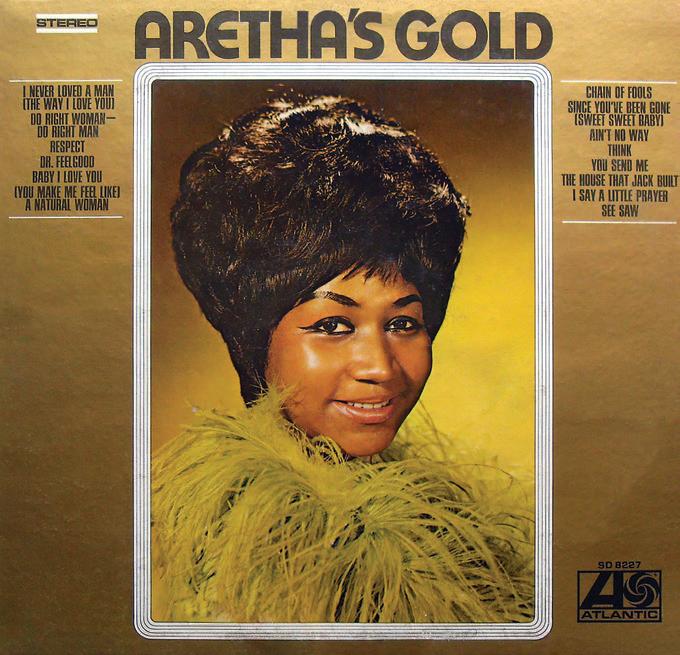

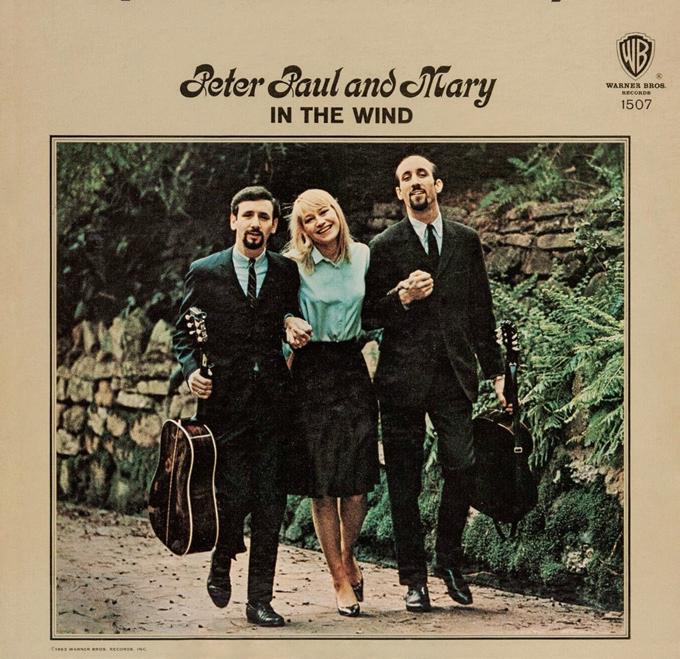

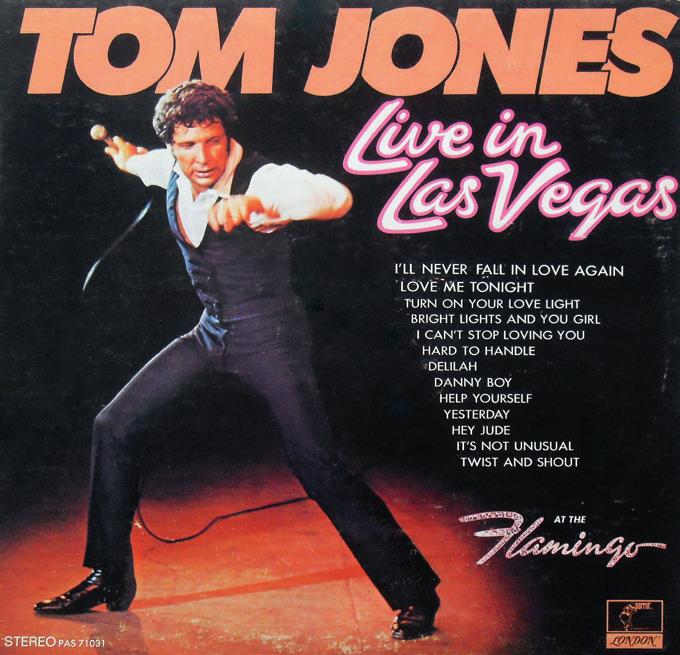

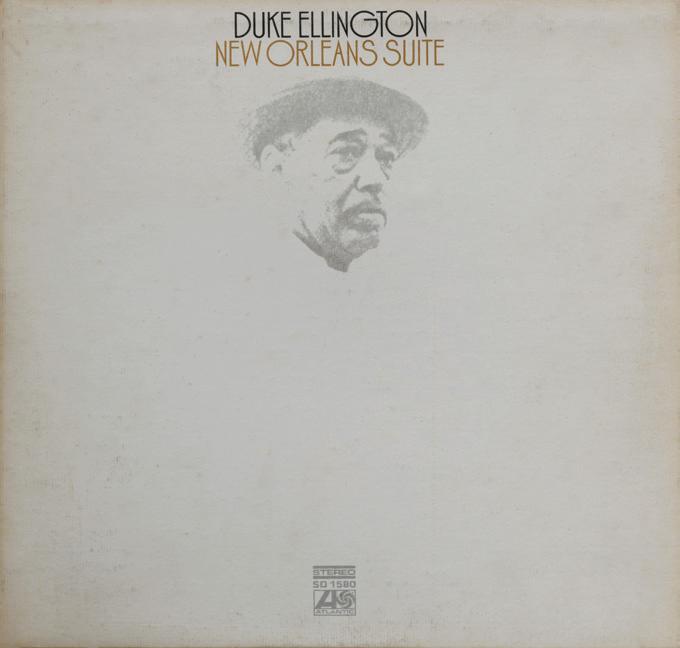

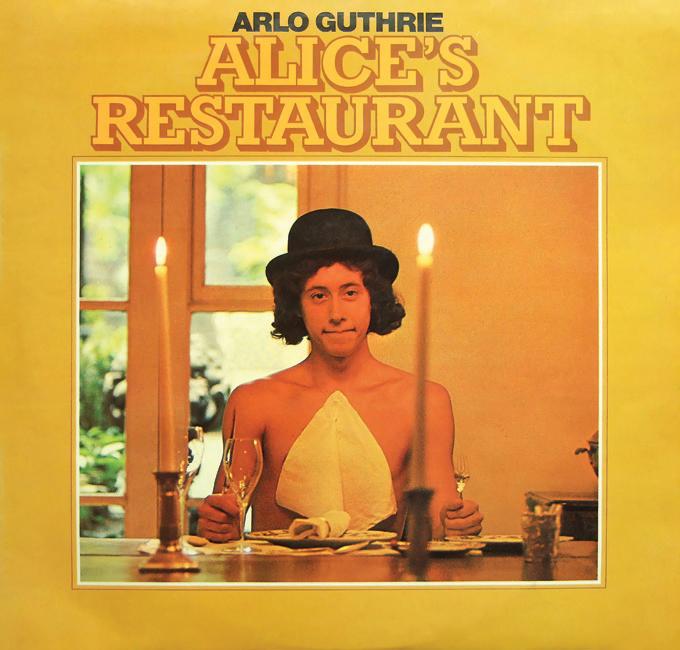

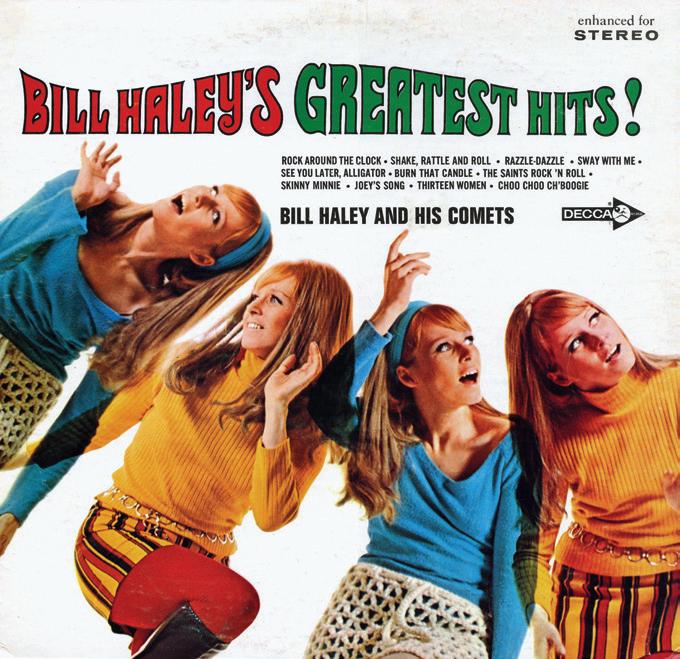

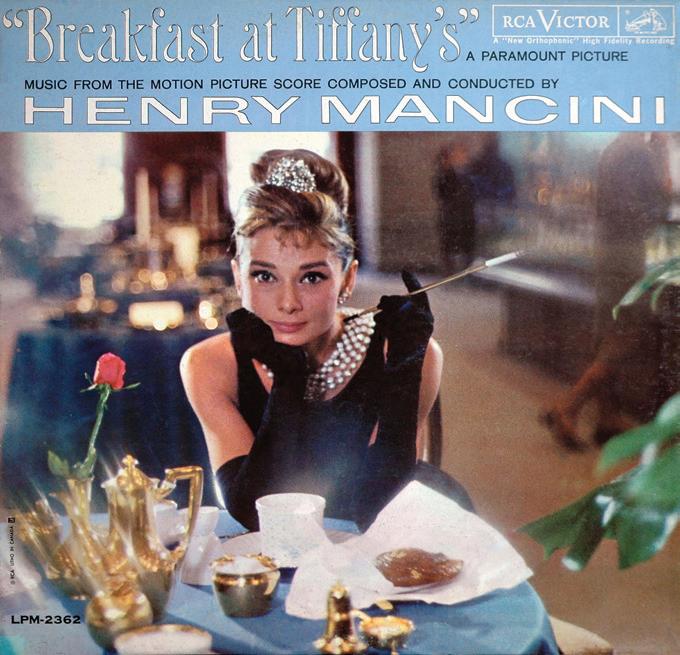

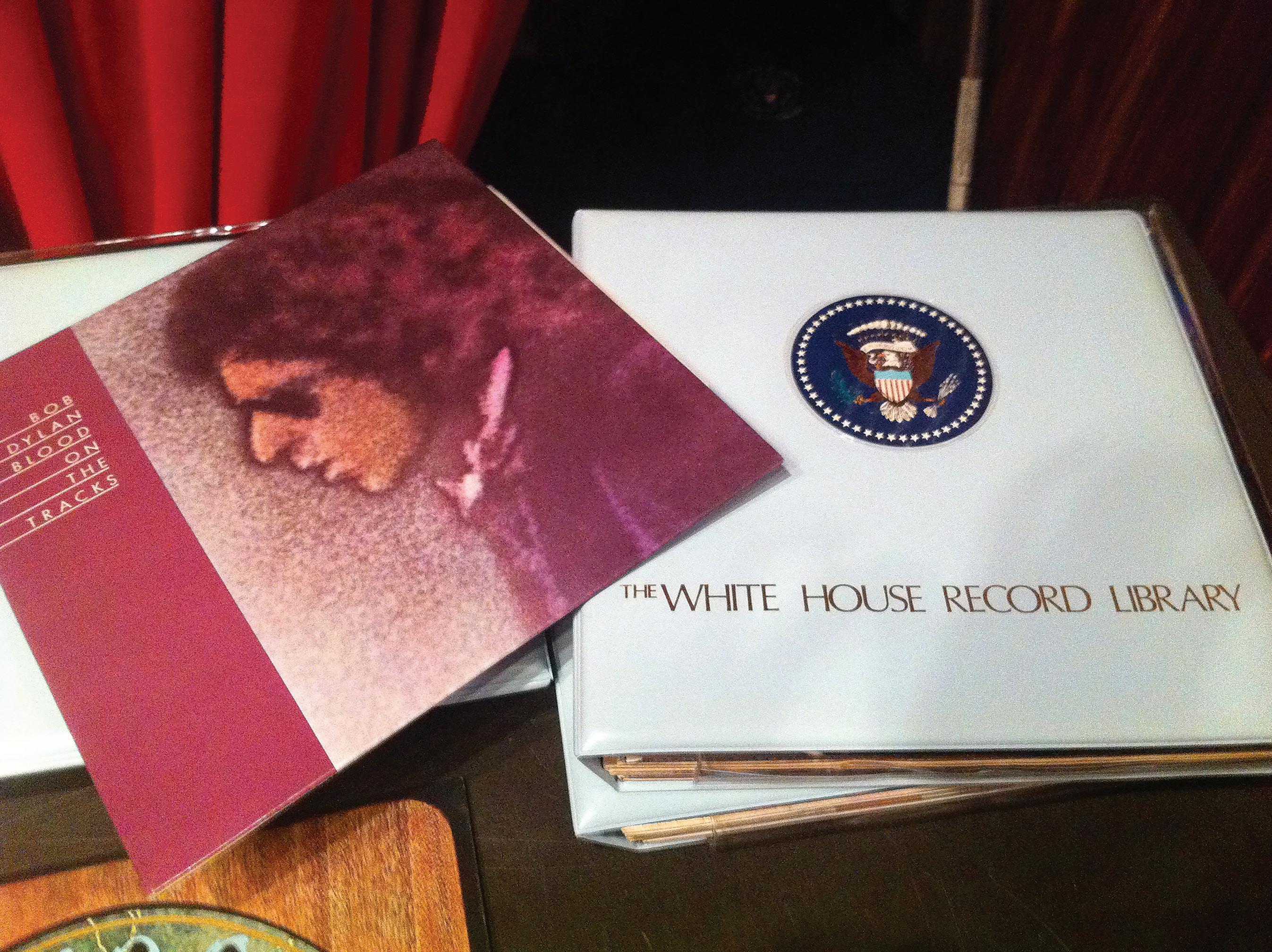

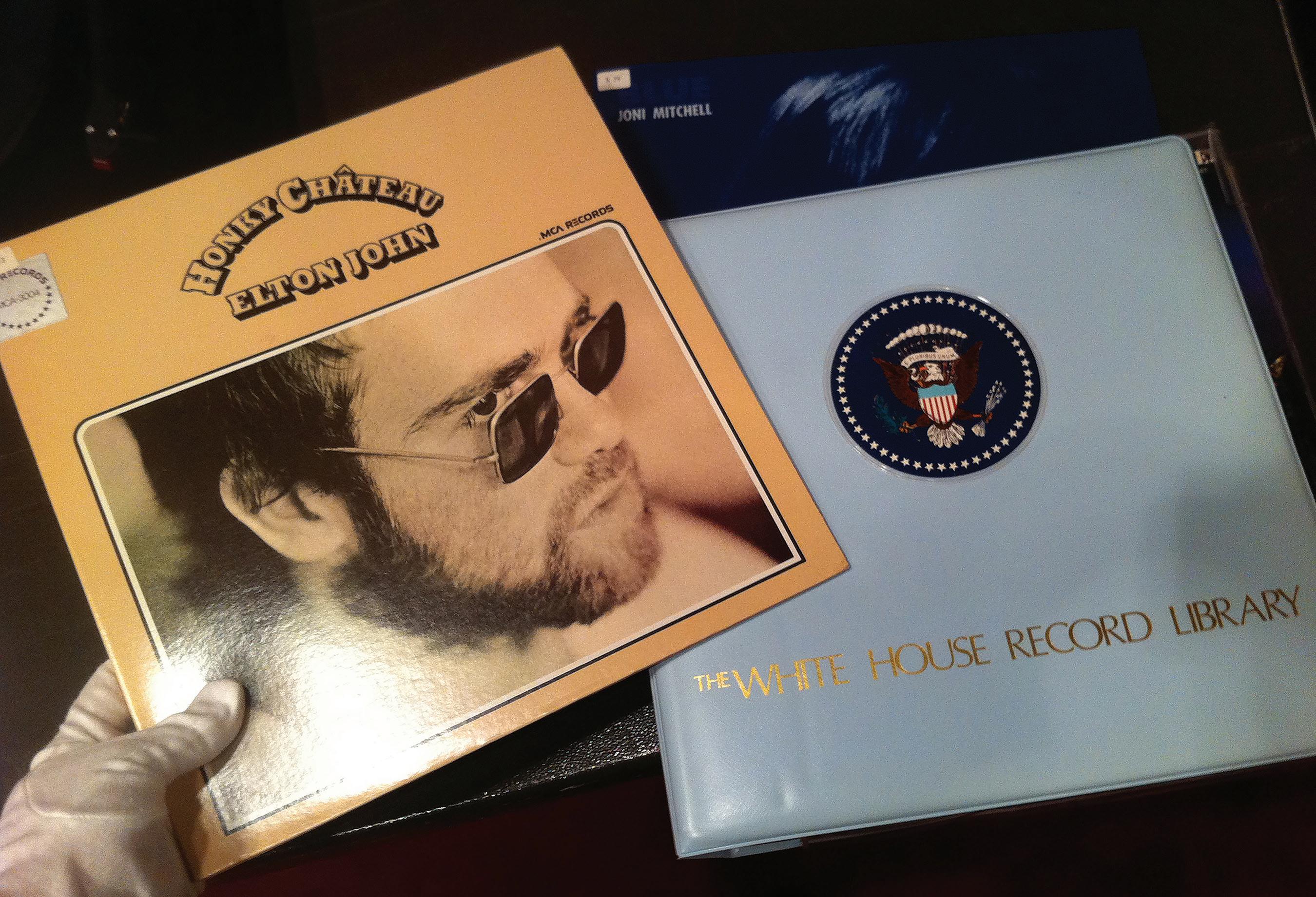

A small sampling of the titles included in the White House Record Library re ects the variety of albums available to the author’s uncles Chip and Je Carter. Included in the collection are classical, popular, musicals, folk, country, gospel, jazz, spoken word, humor, and children’s recordings.

87 white house history quarterly

later she e-mailed me back.

work for you?” she asked. Yes. Yes, that will work.

Dear John,

Yes, we do have a record collection stored at a secure o -site facility. Because it is secure, I cannot pass along the exact location of where the records are being stored.

John, secure off-site facility. Because it secure, I along the exact location records are being stored.

This was, to this day, probably the coolest e-mail I’ve ever received. Full of words like “secure off-site facility” and complete with an “Executive Office of the President” e-mail address. “Secure, off-site facility”: I read it again and again like Ralphie in A Christmas Story. Images of the last scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark flooded my mind. A lonely worker in a cavernous warehouse pushing a couple thousand records through crates of mysterious classified artifacts. Surely these albums were kept between the UFO wreckage and the Holy Grail. The collection was, in fact, real, and I knew that with a little luck, and a tremendous amount of tenacity, the records were accessible.

of the last scene in Raiders Ark mind. worker

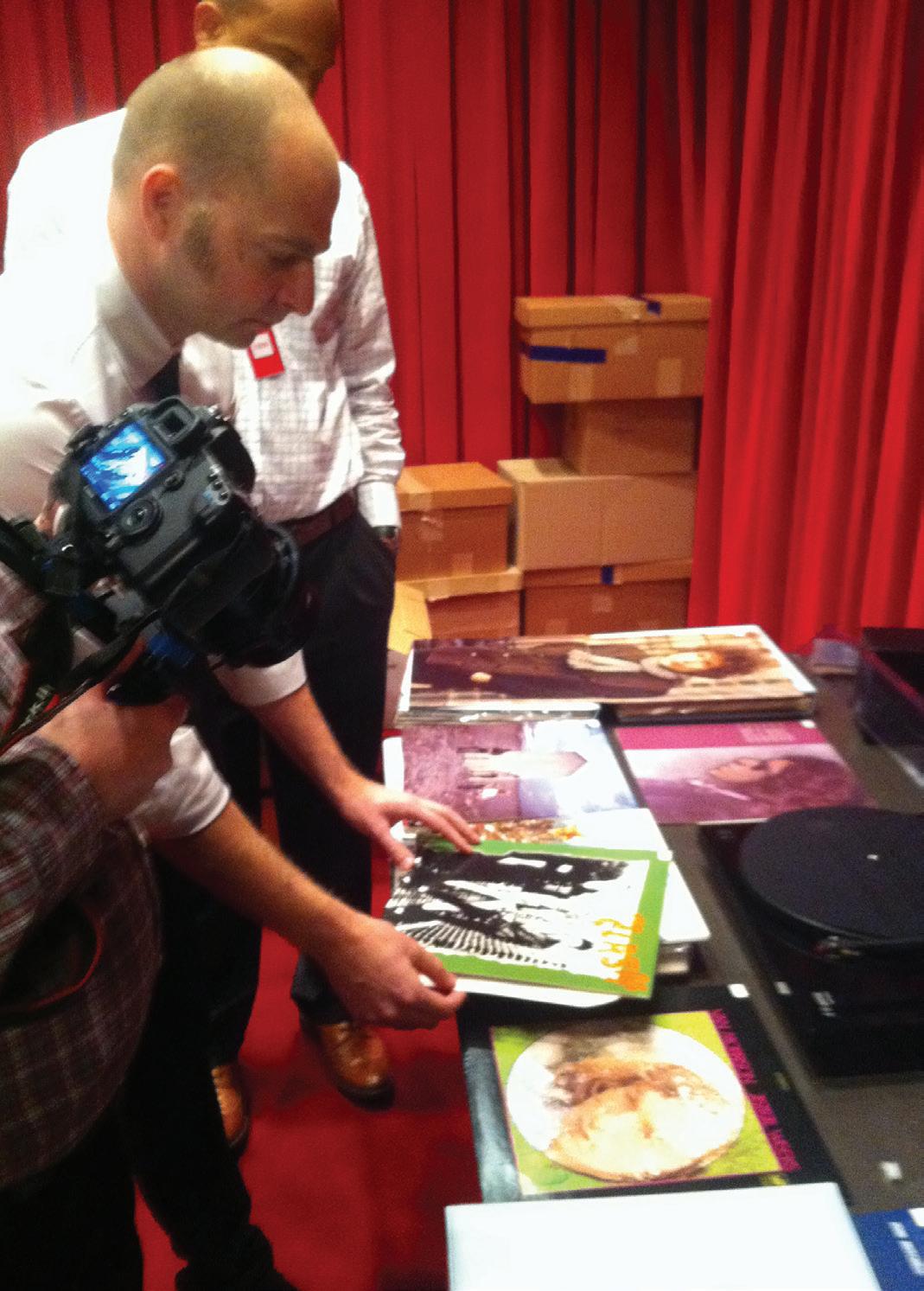

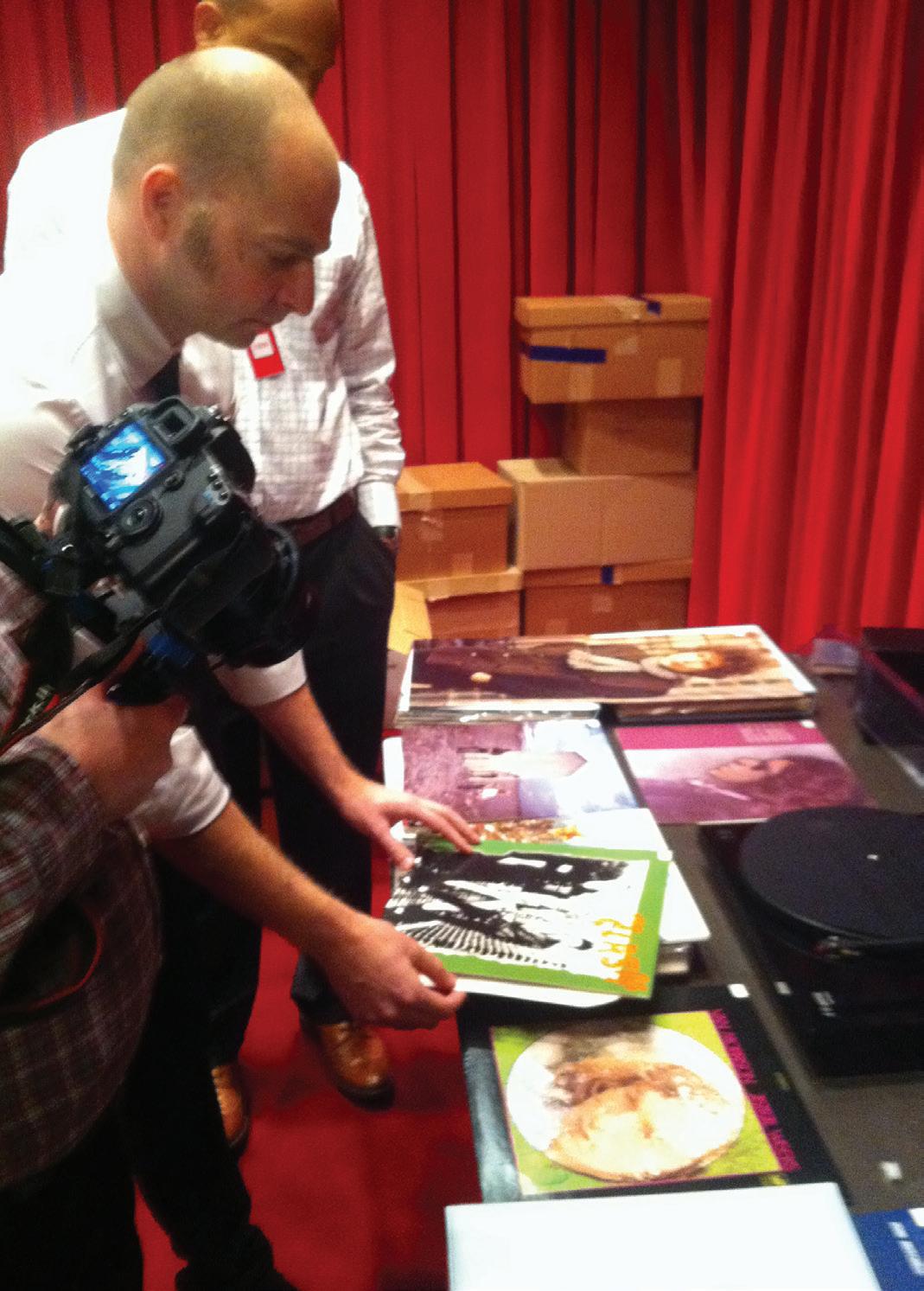

After months of approvals, coordination, cross-country flights, and several roadblocks, I eventually made it to the White House with Bob Blumenthal, his adviser Kit Rachlis, and Rolling Stone writer David Browne in tow. Entering the Movie Theater on the Ground Floor, I came face to face with the records I’d been tracking down for more than a year. There they were, waiting for us, stacked high in cardboard boxes next to the theater screen. Bob, Kit, David, and I looked at each other. This was the actual White House Record Library, and, with Volume Two presented just as my grandparents were leaving the White House, we were the first, the only people to see it, to touch it, to play it! (Yes, I did pack a turntable and small speaker system.)

Trying to contain my excitement, I replied to Monica. Obviously, they wouldn’t allow me into the secure facility, but she surprisingly suggested that the entire collection could be moved back into the White House so I could have a look. “Would that

his Kit Rachlis, and Rollingstarted Costello’s My

Further

(The bonus label of

Like true music lovers, we immediately started digging through the boxes. We called out to one another: “I found The Who!,” “Here’s Joni Mitchell!” We searched for our favorites, and I opened one of the light blue binders embossed with the Presidential Seal to find Elvis Costello’s My Aim Is True. Further digging produced Decade (Neil Young), Blonde on Blonde (Bob Dylan), and The Clash (The Clash) (with the bonus white label 7-inch of “Gates of the West” and “Groovy Times”

left and opposite staff of the White House Office of the Library off-site storage to the White House Theater

John Chuldenko to and speaker system, stacks of boxes were waiting. He and his companions stayed for several hours listening to albums, taking photographs, and absorbing the scope of the historic collection.

left and opposite In 2011, the sta of the White House O ce of the Curator arranged for the White House Record Library to be moved from o -site storage to the White House Movie Theater for John Chuldenko to examine. When he arrived, prepared with a turntable and speaker system, stacks of boxes were waiting. He and his companions stayed for several hours listening to album, taking photographs, and absorbing the scope of the historic collection.

88 white house history quarterly

89 white house history quarterly ALL PHOTOGRAPHS ON THIS SPREAD: JOHN CHULDENKO

left

Among the albums examined by Chuldenko were Elton John’s Honky Château and Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks

90 white house history quarterly BOTH PHOTOGRAPHS: JOHN CHULDENKO

still inside).

We laid out album after album and debated what we’d play first. Bob slid out the pristine copy of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks from its jacket. For those unfamiliar, legendary rock writer Lester Bangs called it a “mystical document,” writing that it “was proof that there was something left to express artistically besides nihilism and destruction.” Springsteen said it made him “trust in beauty” and that it gave him a “sense of the divine.”3 So yeah, Astral Weeks? Go for it, Bob.

Bob switched on the turntable, raised the stylus, and lowered it onto the gleaming surface of the dead wax on the edge of the record: side one, track one. “Astral Weeks.” I still get goosebumps. The tempo perfectly suited for the occasion, Richard Davis’s bass line filling the room, and those first few lines:

To lay me down, in silence easy, to be born again, to be born again.

Packed into anonymous cardboard boxes by government employees and locked away in the secure storage facility, these records that had lain dormant for thirty years were finally unearthed. Born again. Born again indeed.

We stayed for a few hours, playing our favorites while Bob and Kit reminisced about the selections they had made more than thirty years ago. Then Monica popped back in. “Are you almost finished?” she asked. I paused, taking in that question. This was the resurrection of a national musical treasure. Was I finished? Do I have to be? Admittedly, we could have hung out playing records all night long (or at least until President Barack Obama would storm downstairs and ask us to keep it down). “Yes,” I said reluctantly. Monica left the theater, and we started to refile the records we had strewn about the room. Minutes later, a team of overalled gentlemen wheeled dollies into the theater, and, working with alacrity, they loaded up box after box, carrying them back to the secure storage facility. As I watched them go, I couldn’t help but think that these records were headed back to obscurity. There had to be something I could do.

Then I had an idea, a monumental idea. What if there was a Volume Three? Over the last forty years music and America itself have undergone dramatic cultural changes. With the needle lifted on the

collection in 1980, none of the subsequent musical genres are represented—nothing after 1980. There’s no rap or hip-hop, no electronic music, no metal or Madonna. No trap or trance, no emo or Eno. The entire format of the compact disk came and went while the Library lay dormant.

With the country as divided as it is, amid protests, pandemic, the constant doom scroll of social posts, it seems everyone has an opinion on everything—especially music. While admittedly, a record collection alone will not solve our problems, maybe a national conversation about the greatest music of the last forty years could provide some sort of common ground, something we might be able to agree upon. Maybe the White House Record Library could play once more.

notes

This article is adapted from the author’s upcoming book titled White House Wax. The author spoke with Bob Blumenthal in December 2011 and on numerous occasions.

1. Johnny Mercer, introduction to Popular music category, The White House Record Library, Volume One (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 1973), 51–52.

2. Bob Blumenthal, introduction to Popular music category, The White House Record Library, Volume Two (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 1979).

3. Both quotations are widely available. They appear in print in Jon Michaud, “The Miracle of Van Morrison’s ‘Astral Weeks,’” New Yorker, March 7, 2018, and Travis M. Andrews, “The Rage of Van Morrison and the Battle Behind His Masterpiece, ‘Astral Weeks,’” Washington Post, November 30, 2018.

91 white house history quarterly