NELLIE GRANT Marries in the East Room Rediscovered Relics of a White House Wedding WILLIAM ADAIR

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION / WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION white house history quarterly 31

in the winter of 1874, President and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant announced that their daugh ter, Nellie, would be married in May. The groom, Algernon Charles Frederick Sartoris, was an Englishman whom Nellie had met not long before. Her parents were not comfortable with the match. Sartoris was a socialite and a bit of a gadfly at 23, while Nellie was an immature 18. Nevertheless the Grants planned for a splendid wedding, most nota bly redecorating the East Room where the ceremo ny would take place. Andrew Jackson’s three great chandeliers were replaced by even larger ones. Old ornamentation in stucco was adapted and embel lished. Nothing was too resplendent for the Grants’ only daughter. Their decorations, often referred to as the “Steamboat Palace” style, remained the East Room until 1902, when the simpler style we see to day replaced them.

What happened to some of Grant’s decorations is a long story. They seemed to have been lost, and are now found. Some twenty years ago I acquired a collection of interior architectural artifacts at a local auction house. Initially I was on the hunt for antique frames, but my eye was drawn to a small bit of gold leaf shimmering through a pile of wood in the corner of the room, amid other household furnishings.

On a whim, without knowing anything about the objects, I decided to bid and was lucky enough to walk away with the lot. It was only then that I was able to fully examine my new collection.

opposite and previous spread

View of the East Room as decorated for the wedding of Nellie Grant to Algernon Sartoris. Portions of newly installed columns and architectural features seen around the room’s perimeter were later rediscovered by the author.

below

The East Room as it appeared in 1869 prior to the Grant era redecoration. left Nellie Grant and her husband, Algernon Charles Frederick Sartoris, c. 1874.

white house history quarterly32

LEFT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / OPPOSITE: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

In front of me were four hollow-back, carved and painted, fluted wood pilasters, measuring 10 feet × 22 inches × 12 inches, stacked horizontally, one on top of the other in a haphazard fashion. Next to them scattered about the floor, like the Roman Forum, were four Corinthian capitols with carved acanthus leaves and two pairs of carved bases con sisting of rosettes, a wave design, and a meander pattern, all interspersed with other neoclassical archetypes. Each fluted pilaster supported an intricately carved Corinthian capitol fashioned with a row of hand-carved acanthus leaves surmounted

with scrolls. There was also a set of four freestand ing turned and carved wood columns measuring 8 feet × 10¼ inches × 6½ inches. Upon closer examination of the pilasters, I discovered most of the surfaces were covered in degraded gray house paint and embedded with dirt. Nonetheless, I was not discouraged, as paint can sometimes be removed with minimal damage to the original sur faces and I sensed that the artifacts were of extraor dinary quality. To paraphrase my mentor, Paul Levi, “These objects needed looking after.”

Four turned and carved wooden columns purchased by the author at auction.

white house history quarterly34

Two of four hollowback wood pilasters, were purchased in pieces by the author and reassembled as later shortened and reconfigured. The pilasters and columns were made to embellish the East Room during the Grant administration, in advance of the wedding of Nellie Grant.

white house history quarterly 35

BOTH IMAGES THIS SPREAD: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

36 white house history quarterly TOP:

MAX HIRSHFELD / ALL OTHER IMAGES THIS SPREAD: BRUCE WHITE

FOR

THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

opposite

The author, conservator William Adair, at work in his studio in Washington, D.C. Upon examining the Corinthian columns, he discovered Roman numerals behind the gilded eagles, indicating that each column was numbered according to its location. Some of the original yellow paint is visible.

below

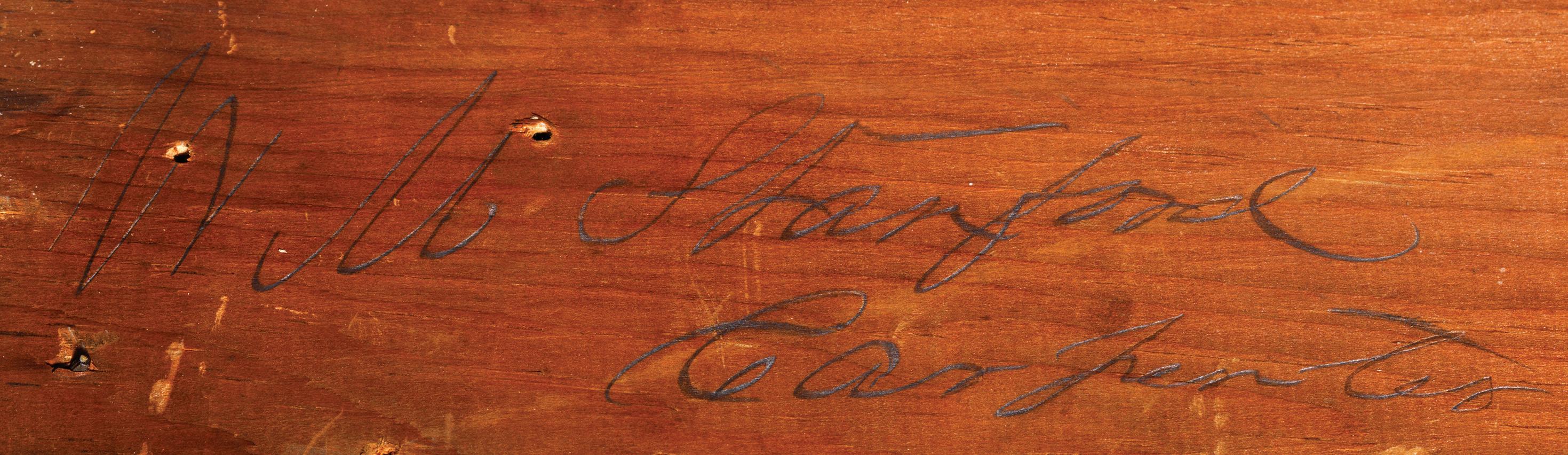

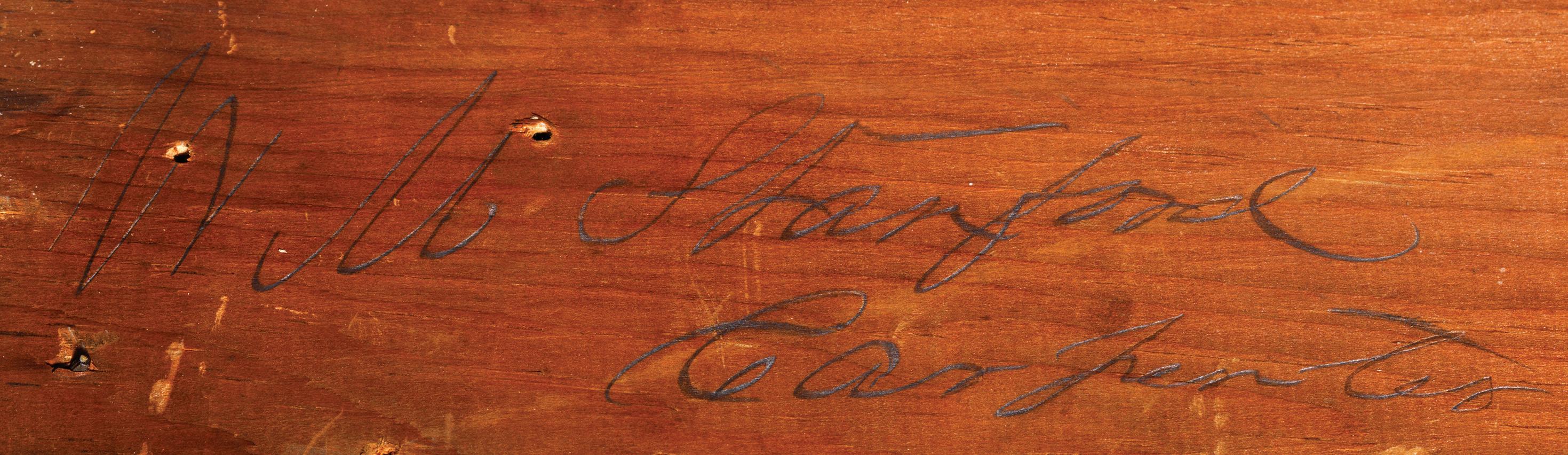

“Will Stanford, carpenter” penciled into the rear of one of the columns. It is rare to find a signature on an architectural piece. The designer of the columns is still unknown.

right

When Adair scraped away portions of later house paint, original gilding and shades of ivory were revealed.

Having first trained as an artist, frame-maker, and conservator of gilded artifacts, and ultimately as a frame historian, I developed an eye for obscure detail.1 I was no longer looking with a casual glance, but really observing, more like an archaeologist and a detective. W hen I worked at the Smithsonian Institution, a colleague once quipped to me, half joking, “A conservator must sometimes learn to see the invisible.” As I continued my examination, I noticed that each of the capitols was carved with Roman numerals at the base of the central acan thus leaf. (I have since learned that each of the cap itols once had a gilded eagle at the center point).2 I also noticed a penciled inscription in flourishing freehand nineteenth-century script, “Will Stanford, Carpenter.” It is rare to have an artisan’s signature on a historic artifact such as this and also fortu nate to have identified the unsung hero of the design team, the carpenter. On the verso of each of the pilasters and columns I found paper iden tification tags with what appeared to be museum accession numbers handwritten in red magic mark er. There was also a fragment of early electrical or telephone wire still nailed to the surface of one of moldings.3 All these details, or clues, could serve as a road map through history, if we can interpret them.

On April 4, 2001, the curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Richard Murray, visited my studio in Dupont Circle and recognized the pilas ters and columns as having come from the East Room of the White House. Apparently, he had ac tually discovered the White House provenance in 1970, when he was a Smithsonian Fellow research ing Alice Pike Barney’s collection of art and furnish ings in the Barney Studio House.

The history of the pilasters and columns is this. In 1874 President Ulysses S. Grant’s directive to his supervising British-American architect, Alfred B. Mullett, was to “elaborate” on the original neo classical designs of Irish architect, James Hoban, who in 1817 had reconstructed the White House

following the fire set by British troops in the War of 1812. To expand on classical simplicity, Mullett divided the East Room into thirds with a double cornice supported by sets of Corinthian columns, originally painted white and gold. They acted as pillars for an elaborate 1874 Greek Revival overmantel mirror in the East Room.4 It quickly became a complicated and ponderous style, like a three-layered gold and white cake with a silver ceiling. But the president’s wishes needed to be

37white house history quarterly

carried out. Congress typically allocates funds for updating, and the enriching of the interiors of the White House was perfectly timed to create a backdrop for the upcoming wedding of Grant’s daughter, Nellie.

For this important high-visi bility commission, Mullett may have collaborated with William J. McPherson, a Boston deco rator, but there is little doc umentation of the project.5 Mullett may have also turned to the Austrian designer Richard Von Ezdorf to over see fixtures and finishing details in the East Room. Von Ezdorf had been raised in Venice and had studied engineering, architectural design, and history in Europe before immigrating to the United States in 1873. He joined the Treasury Department’s Office of the Supervising Architect, first working as a draftsman. He then advanced to design work on the State, War and Navy Building adjacent to the White House.6

Later critics accused Mullett of “using over blown ornament to hide weak form.”7 Others referred to his elaborate work at the New York City Hall Post Office as “Mullett’s Monstrosity.”8 The New York Sun called him “the most arrogant, pretentious, and preposterous little humbug in the United States,”9 and he soon “gained a reputation as a micromanaging authoritarian with an explo sive temper.”10 In 1890, ill and in financial difficulty several years after the collapse of a floor in the City Hall Post Office that killed three people and led to an investigation for negligence, he committed suicide in Washington, D.C. History softened its view of him, and Von Ezdorf, too, is now recognized for his contribution to monumental Victorian architecture.

In 1881–82, President Chester A. Arthur redec orated the White House. He had not immediately moved into the mansion following the death of his predecessor James A. Garfield, as he wanted it refurbished first. Although many presidents rely on the assistance of their wives for such projects, Arthur was a widower and chose to enlist the ser vices of Louis Comfort Tiffany to redecorate the State Rooms.11 Tiffany, one of the first profession al decorators hired to work in the White House, recalled some of the work he had done in the White House:

At that time, we decorated the Blue Room, the East Room, the Red Room, and the Hall between the Red and East Rooms, together with the glass screen contained therein. The Blue Room, or Robin’s Egg Room—as it is sometimes called— was decorated in robin’s egg blue for the main color, with ornaments in a hand-pressed paper, touched out in ivory, gradually deepening as the ceiling was approached. In the East Room, we only did the ceiling, which was done in silver, with a design in various tones of ivory.12

In 1886, the East Room was described in this way: The proportions of the East Room are agreeable, it being 80 feet long, 40 feet wide, and 22 feet high. The ceiling is divided by two heavy cross beams in such a manner as to make the center compartment a third smaller than those at either end. The ceiling itself is in imitation of rough stucco, painted, and then finished in silver aluminum, and finally in mosaic work of three shades of brown. In each part, there is a border of squares covered alternately with arabesques and mosaic. Each centerpiece is one large square with narrow side parallelograms and corner squares. . . . The Cross-beams are supported on either end by an Ionic pilaster and one pillar, with the bases the height of the dado, and floriated capitols. They are also in white and gold. The four large mantels also in white and gold. . . . The cornice consists of one large cove with two members on either side. The molded frieze, two feet deep, together with the cornice and cove, are finished in white and gold, which predominates in the decorations. The cross beams are treated as part of the cornice. Allowing the eye to pass downward to the dado of paneled wood, three feet and a half high, we find the same elaborate treatment of the two leading tints.13

Then, when Theodore Roosevelt became pres ident in 1901, the White House interiors were redecorated once again. It was common practice for many incoming presidents and first ladies to keep up with changing fashions by replacing fur nishings and renovating interiors. For this work

Architect Alfred B. Mullett, c. 1880, was responsible for Grant’s newly redecorated East Room. His work was later criticized for “using overblown ornament to hide weak form.”

38 white house history quarterly U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

below left

Small portions of the mirror pillars still retain their original gold and cream paint scheme, which was later covered over with blue and silver.

below right

The Alice Pike Barney Studio House in Washington, D.C., is seen here in 1933. After Barney’s death in 1931, her daughters held the house until 1961, when they donated it to the Smithsonian. In 1976 the house opened as part of the National Museum of American Art. The Smithsonian eventually closed the museum and sold the building. Today it is the Embassy of Latvia.

Roosevelt commissioned the prestigious New York firm of McKim, Mead & White. The East Room was completely dismantled, thus removing all the work put in by Mullett in 1874 and the subsequent work by Tiffany in 1882.14 All was disposed of at auc tion, including fragments sold as the “East Room Adornments” that consisted of numerous mirrors, mantels, pilasters, and souvenirs.15 (Until 1961, sur plus White House furnishings and architectural fragments were repeatedly salvaged, discarded, or sold off at auction.)16

The property from the Roosevelt renovation was auctioned at the salesroom of C. G. Sloan at 1407 G Street NW, on January 21, 1903. Some lots were purchased by John R. McLean, owner and publisher the Cincinnati Enquirer and the

Washington Post, for his home at 1500 I Street NW. When McLean rebuilt this home in 1907, the East Room elements were removed and may have found their way to the palatial Massachusetts Avenue residence of Thomas F. Walsh, who liked to collect interesting bits of furniture. Walsh’s daughter Evalyn was married to McLean’s son Edward. Walsh’s neighbor on Sheridan Circle, Alice Pike Barney, may have acquired the elements from McLean or Walsh, if not directly from the auc tion. In any case, it was from Barney collec tion of art and furnishings that the National Collection of Fine Arts acquired the East Room elements in December 1961. They were deaccessioned in May 1999.17

39white house history quarterly LEFT: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION RIGHT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

white house history quarterly40 BRUCE WHITE FOR THE

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

opposite

Details of the pillars reveal the original Arabic script visible through the later overpaint.

The original columns had later been overpaint ed with bronzing powder and then painted with a wash of oxidizing greenish glaze of various colors of bronze and silver paint. All four columns have Arabic script visible under this thin bronze glaze. The script was possibly made by Tiffany’s team as part of his redecorating scheme for the room, but there is no direct evidence to back up this claim, yet.

There are some unusual treatments on the pilasters, capitols, and columns still to be exam ined as well as the original decorative and paint ing schemes. More work and analysis need to be undertaken with paint specialists to document the various colors, gilding, and glaze layers on all the surfaces. The “shades of ivory” that Tiffany referred to are actually peeping through the surface of the pilasters, under the protection of the thick gray house paint, waiting to see the light of day, as is the gold leaf from 1874.

It is rare to have the opportunity to study objects like these. What we can learn from them is critical to our understanding of the period. All these various layers of paint and glazes are not only tools for the interpretive history of this room but of American decorative arts history as well. Nellie Grant’s wedding columns illustrate where art, his tory, and a little bit of luck come together to tell a story.

NOTES

1. William Bruce Adair, The Frame in America, 1700–1900: A Survey of Fabrication Techniques and Styles (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects, 1983).

2. Information from William G. Allman, former curator, The White House. To date three of the four eagles have been located, two in private collections and one in the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence.

3. The wire may date from 1891, when electricity was installed in the White House. William Seale, The President’s House: A History, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), 1:570–71.

4. For a description of the redecoration, see Seale, President’s House, 1:454–55.

5. Allman to Tom Michie, May 18, 2000.

6. “Richard Ezdorf (1848–1926),” The Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Life in the White House, online at https:// georgewbush-whitehouse-archives.gov.

7. “Alfred B. Mullett,” Wikipedia.

8. Quoted in Jason Carpenter, “Historic Post Offices: Architectural Masterpieces That Are More Than Just Places to Drop Mail,” posted October 22, 2014, 6sqft, 6sqft.com.

9. Quoted in Cecil D. Elliott, The American Architect from the Colonial Era to the Present (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003), 78.

10. “Alfred B. Mullett,” Wikipedia.

11. For this redecoration, see Seale, President’s House, 1:518–23.

12. Quoted in Tessa Paul, The Art of Louis Comfort Tiffany (London: New Burlington Books, 2004).

13. Hester M. Poole, “At the White House,” Decorator and Furnisher 7, no. 6 (March 1886): 170.

14. For the Roosevelt renovation, see Seale, President’s House, 1:640–45.

15. William G. Allman to Virginia Burden, Gold Leaf Studios,

December 27, 2005, quoting “East Room Adornments,” Washington Post, January 22, 1903.

16. Leslie B. Jones, “Celebrating the White House: Treasures of the First Families,” in Celebrating the White House: Washington Winter Show, January 6–8, 2012 (Washington, D.C: Washington Winter Show, 2012), 37. On September 22, 1961, these practices were ended by law. Public Law 87-286, 75 Stat. 586, section 2, reads in pertinent part: “Articles of furniture, fixtures and decorative objects of the White House, when declared by the president to be of historic or artistic interest . . . shall . . . be considered to be inalienable and the property of the White House. Any such article, fixture or object, when not in use or on display in the White House shall be transferred by the direction of the President as a loan to the Smithsonian Institution for its care, study and storage, or exhibition . . . and returned to the White House . . . on notice by the President.”

17. Allman to Gold Leaf Studios, December 27, 2005. The Barney Studio House on Sheridan Circle is now the Latvian Embassy, and the Walsh-McLean House on Massachusetts Avenue NW is now the Indonesian Embassy. See also “Walsh-McLean House (Indonesian Embassy),” D.C. Historic Sites, https:// historicsites.dcpreservation.org; Kira M. Sobers, “The Alice Pike Barney Studio House,” posted December 4, 2014, Smithsonian Institution Archives, https://siarchives.si.edu. For the deaccessioning, see acc. no. 1968.159A–L, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C. See also Alice Pike Barney Papers, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

white house history quarterly 41