Please note that the following is a digitized version of a selected article from White House History Quarterly, Issue 54, originally released in print form in 2019. Single print copies of the full issue can be purchased online at Shop.WhiteHouseHistory.org

No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All photographs contained in this journal unless otherwise noted are copyrighted by the White House Historical Association and may not be reproduced without permission. Requests for reprint permissions should be directed to rights@whha.org. Contact books@whha.org for more information.

© 2019 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions.

WHAT Flavo r Is The C ake?

White House Weddings and the Public’s Curiosity

white house history quarterly 63

bethanee bemis OPPOSITE: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION ABOVE: RICHARD M. NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

as long as there have been wedding cakes , there have been people saving pieces of it for one reason or another. As early as the seven teenth century, single women took home a piece of the nuptial cake to slip under their pillow, believing they would dream of their future husbands. In the early to mid-twentieth century couples began sav ing wedding cake to be served at the christening of their first child. Today many couples freeze the top tier of their wedding cake to be enjoyed on their first anniversary. Few cakes, however, achieve the lon gevity of presidential family wedding cakes, slices of which reside in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History many years after the nuptials they celebrated.1

White House weddings have long fascinated the public. Because they take place the people’s house, Americans feel a sense of national participation, of being guests by proxy. The bride and groom seem to belong to all of us, particularly if they are members of the president’s family; indeed, the Washington Post explicitly hailed Jessie Wilson as “The Nation’s Daughter-Bride” upon her White House wedding in 1913.2 Those who feel a kinship with a bride and groom naturally want to participate in their wed ding celebration even if they cannot be physically present at the ceremony, and they satisfy this desire in other ways.

One of the “sweetest” ways guests participate in a wedding reception is by eating the bridal cake, a

ritual that testifies to their having witnessed the marriage and accepted its validity.3 Those who are not witnesses or guests can still “consume” the cake visually, by enjoying media descriptions and images. While for early White House weddings one had to be there to enjoy the cake, later weddings were cov ered by the press, with descriptions and then pho tographs of the wedding cake. In some instances slices of the cake were saved in public institutions.

The first several White House weddings were considered very private affairs, in the custom of the day. What is known of their wedding cakes comes from the diaries and letters of guests. For example, it seems there was not enough cake at a reception held for Maria Monroe Gouverneur and Samuel Gouverneur on March 13, 1820, four days after their White House wedding, for future first lady and reception guest Louisa Catherine Adams reported in her diary: “I didn’t get a bit of cake and Mary had none to dream on.”4 The Mary in question was Louisa’s niece, Mary Catherine Hellen, who, despite not having a piece of wedding cake to place under her pillow, would be the next White House bride. Eight years later, on February 25, 1829, Mary Catherine wed John Adams II, Louisa’s son. This time there was enough cake on hand for guests to take home and even enough for Louisa to send a piece to her son Charles Francis, who had not been able to attend. Receiving cake via post enabled him to enjoy his brother’s marriage, albeit after the fact.5

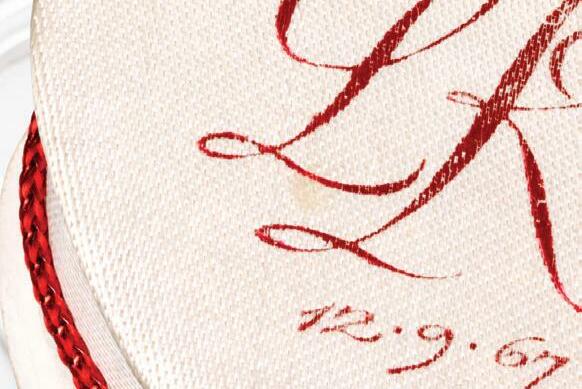

previous spread

Tricia Nixon and Edward Cox share the first bite of their wedding cake, which was embellished with doves and their initials, as seen in the detail. below

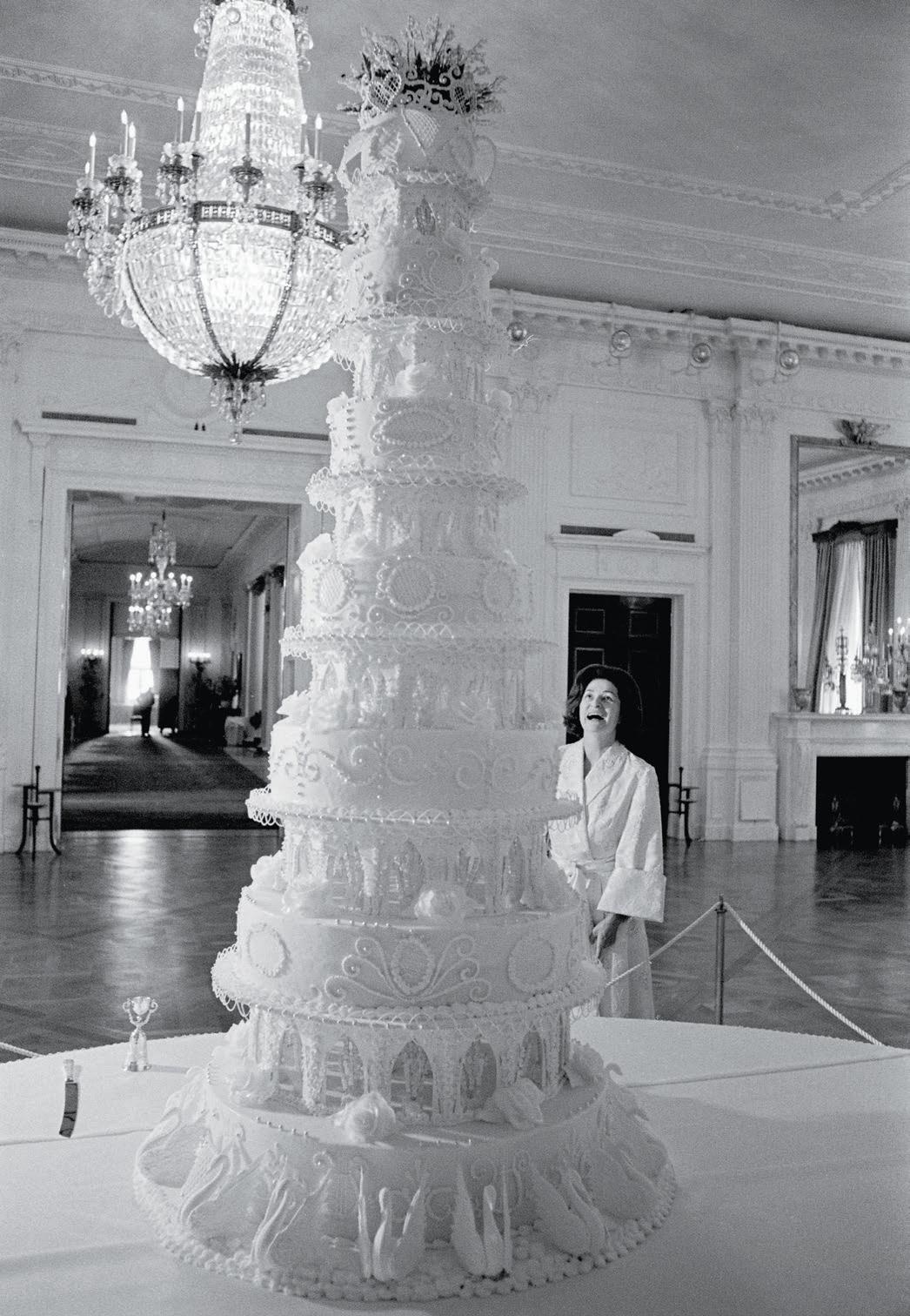

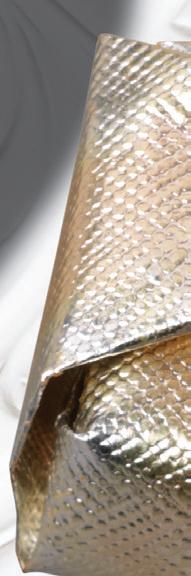

Guests at the 1967 wedding of Lynda Johnson gather to view the cake.

white house history quarterly64 LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

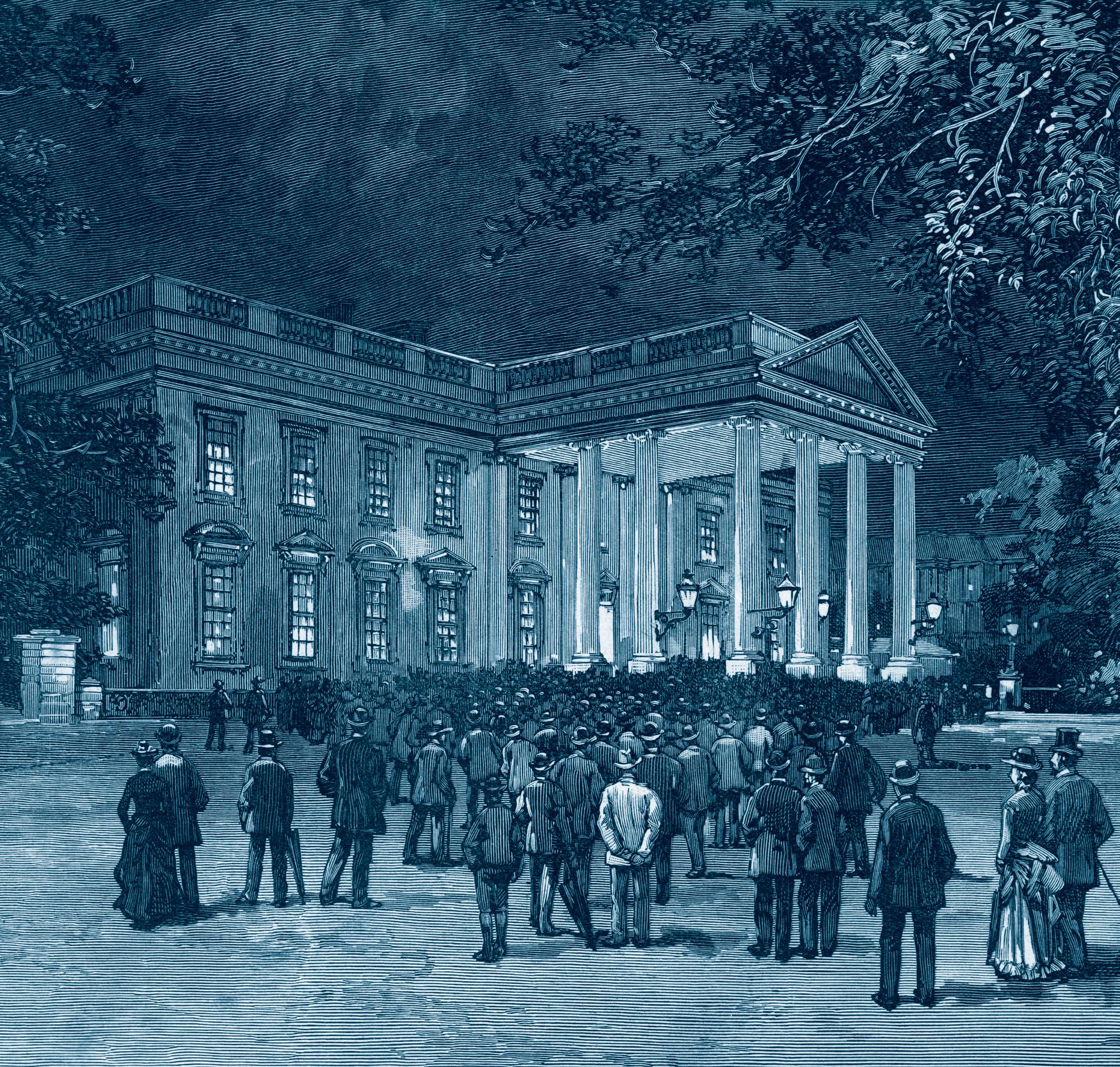

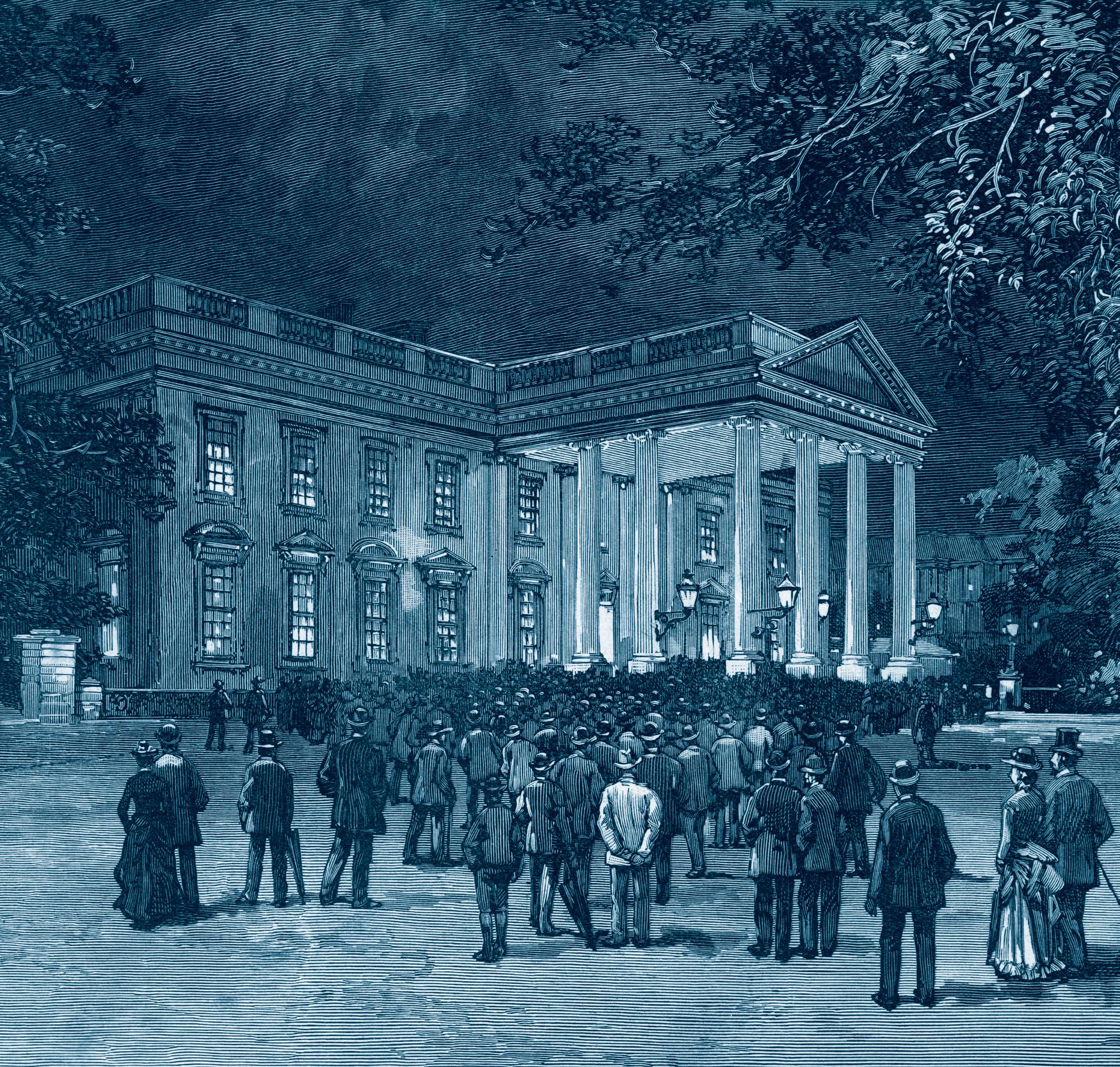

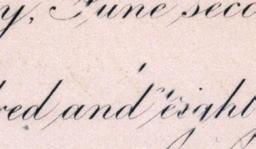

A crowd of curious onlookers waits outside of the White House on June 2, 1886, hoping for a glimpse of President Grover Cleveland and his new bride, Frances Folsom Cleveland.

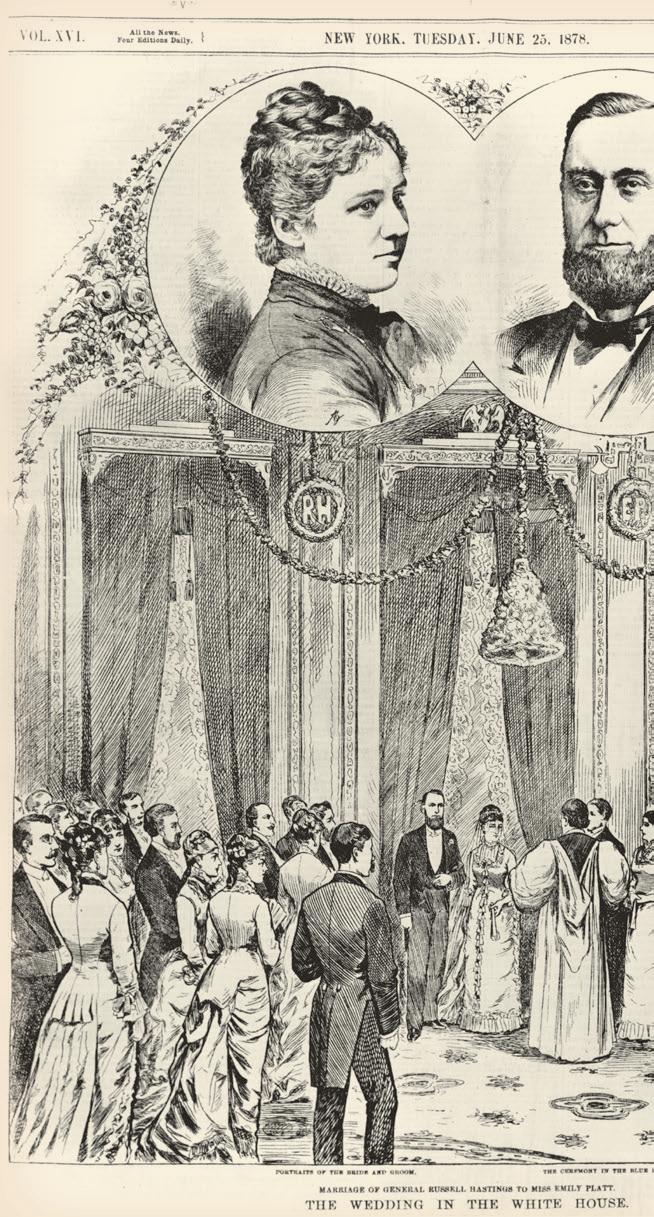

The next few White House weddings received slightly more attention—a few lines in local papers, essentially just announcements, because press coverage of weddings before the 1850s was con sidered vulgar, only for actors and other “low” peo ple. Private documents are still the only source of information on the wedding cake. For example, the White House doorkeeper Thomas Pendel recorded in his diary that at the 1874 wedding of Nellie Grant to Algernon Sartoris, the wedding cake was “put up in little white boxes about six inches long and three

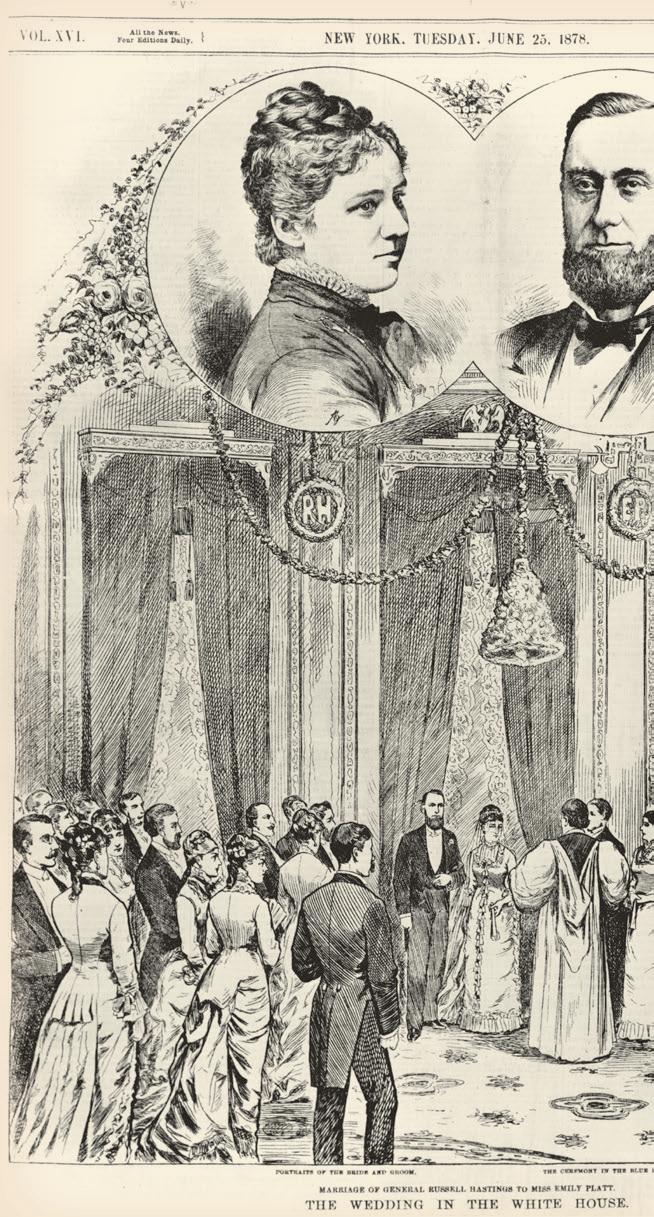

inches wide” for guests to take home and “dream on, that those who were single might dream of their future husbands.”6 First Lady Lucy Webb Hayes explicitly forbade the publishing of bridal details concerning the wedding of her niece Emily Platt in 1878, fearing that “such publicity ha[d] an injurious effect, in many instances, on the parties concerned,” though it was later reported that the cake was white with the bride and groom’s initials stenciled in blue.7

white house history quarterly 65

WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

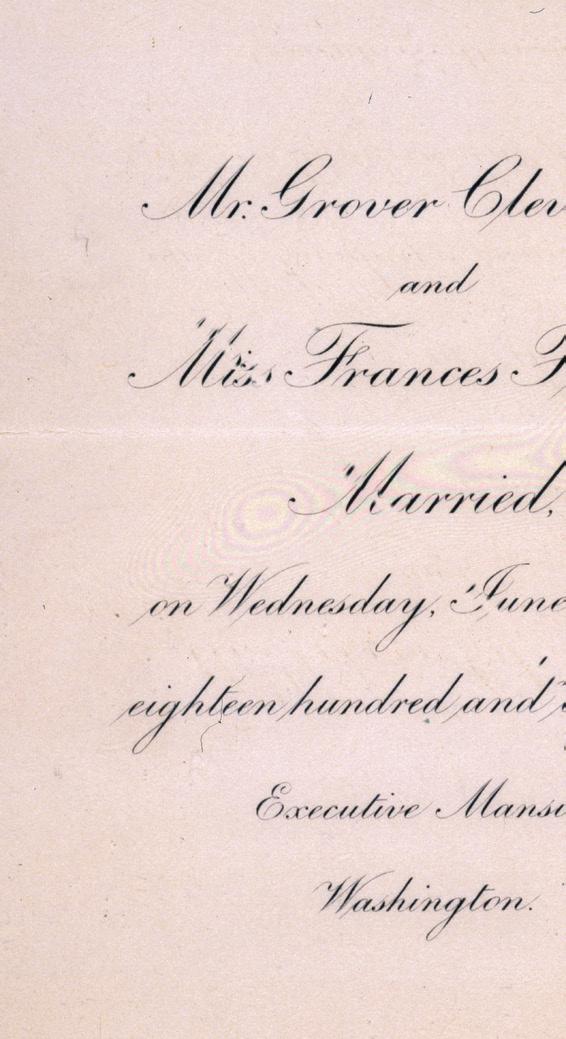

Detailed reporting of White House weddings began in 1886 with the wedding of Grover Cleveland and Frances Folsom, the first wedding of a president held in the mansion. There was no keeping this wedding secret. The groom was president; the bride was young and beautiful, and half his age. The public was captivated. “The interest taken by all classes of people in to-night’s White House wedding,” proclaimed the Washington Post, “is a genuine one participated in by all classes of people.”8 Hundreds turned up in person, uninvited, to stand on the White House lawn during the ceremony, in what was called “a jolly, good-natured gathering and thoroughly democratic.”9 Newspapers across the country scrambled to report the details of the wedding, which had been officially announced only a few days before the event. Prominent among those details were entire paragraphs dedicated to the wedding cake, the first White House wedding cake to be so visually “consumed” by all interested parties. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported the cake to be “a wonder of snowy whiteness . . . there was not a break in the expanse of whiteness which overspread the cake. The initials ‘C. F.,’ raised from the surface, seemed to grow naturally out of it; the waxen wreath of orange blossoms which was deftly fastened round the top looked as though it had grown there.”10 The “little satin boxes which contained slices of the cake material” that were given away as souvenirs of the occasion were, according to Harper’s Bazaar, “highly prized by the one hundred and fifty persons who [were] so fortunate to possess them.”11 In fact, some of those so fortunate were sufficiently gratified as to save their boxes, cake and all. Several boxes survive today, including one in the National Museum of American History and one at the Grover Cleveland Birthplace State Historic Site in Caldwell, New Jersey, which has a piece of cake inside.12

From the Clevelands’ marriage on, no White House wedding could go without at least a mention of the cake in the news. Once the American people got a “taste” of “consuming” the White House wedding from the outside, they remained interested in knowing the details when the occasion arose. If the White House weddings belonged to the people of the United States, then the cakes did as well.

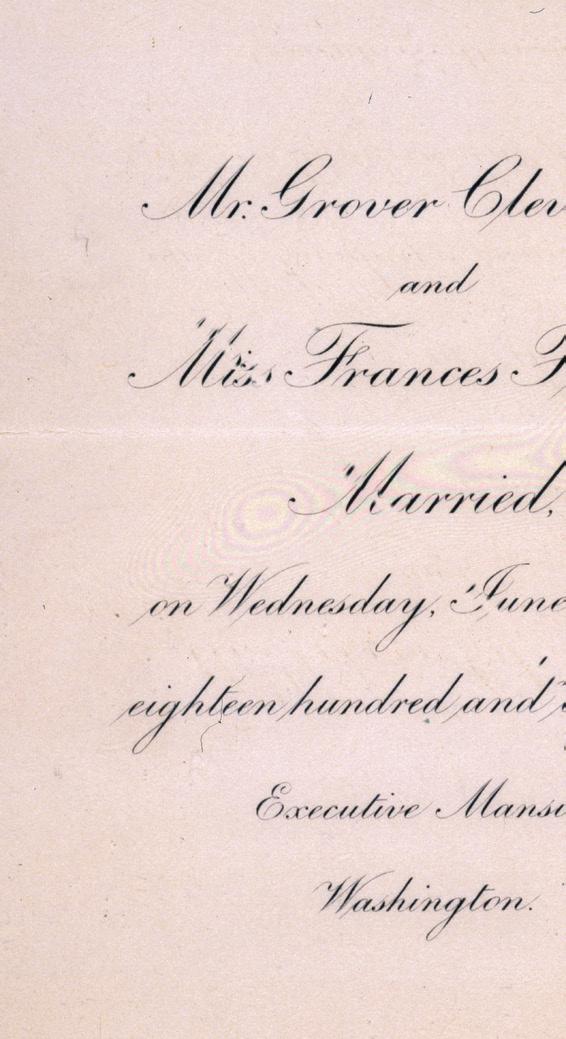

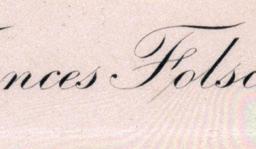

1886 Frances Folsom and Grover Cleveland

As this June 12, 1886, two-page spread in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper confirms, the Cleveland wedding was very big news. A century later White House Pastry Chef Roland Mesnier created a 5 foot tall replica of the wedding cake. Slices of the original were given to guests in boxes, one of which remains preserved in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

white house history quarterly66

ANNOUNCEMENT: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY ALL OTHERS: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

67

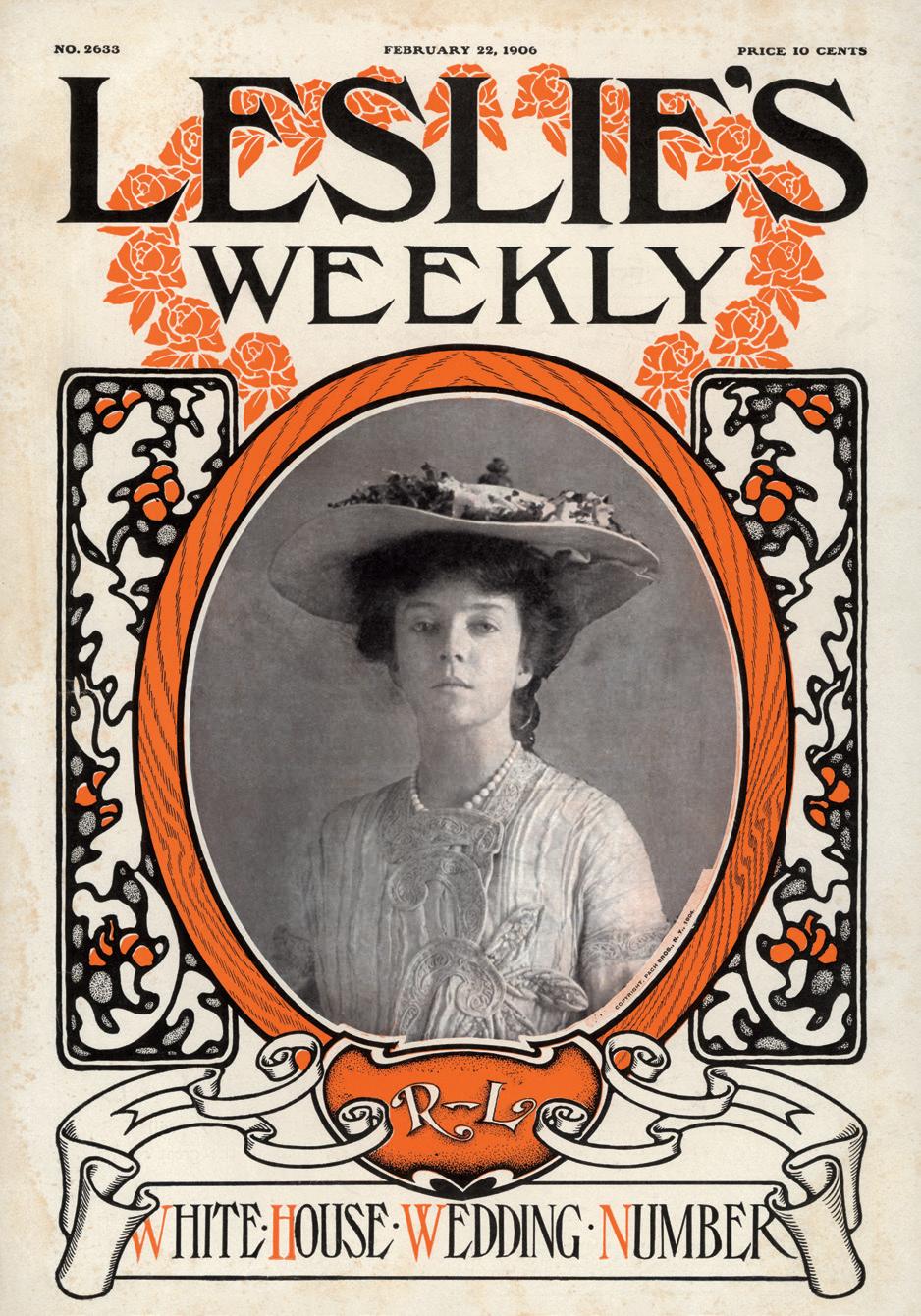

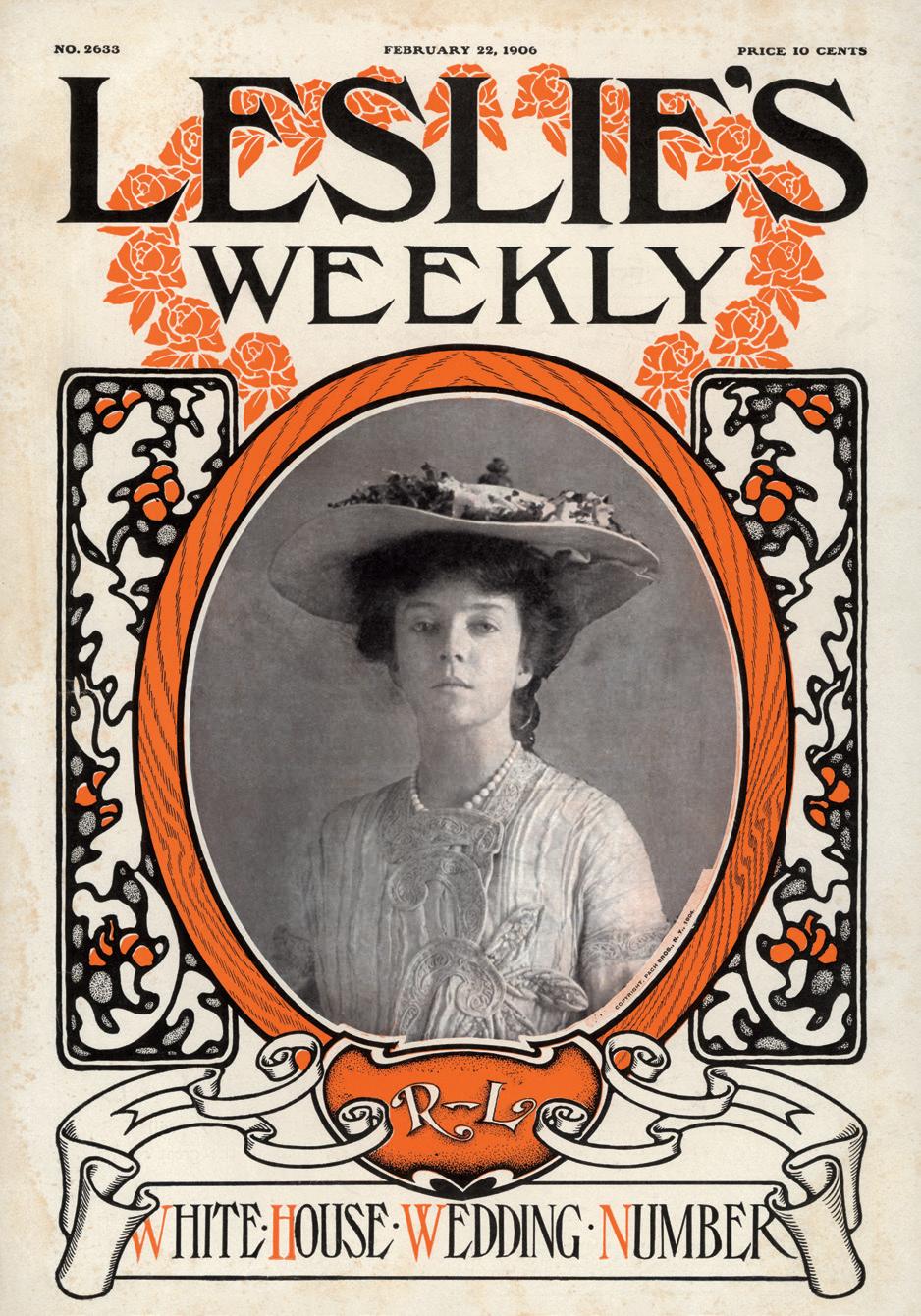

For the next White House wedding, that of Alice Roosevelt and Nicholas Longworth in 1906, the public was treated to the knowledge that the cake was “three feet across and a foot in thickness,” consisting of “four layers of cake with icing in between each.” On top of the cake rested “sugar cupids made after the exact pattern of those which ornamented the cake of Miss Roosevelt’s grandmother.”13 Not only did the description of her cake travel the country, at least one piece did, too. A friend who had attended the wedding sent Dr. H. S. Kinsmonth, a member of the Asbury Park, New Jersey, city council, a piece of Alice Roosevelt’s cake. Dr. Kinsmonth then presented it to the council “as a souvenir of one of the most celebrated weddings that has ever taken place in this country.”14

Written descriptions of White House wedding cakes were enhanced with photographs by the time of Jessie Wilson’s wedding to Francis Bowes Sayre in 1913. Interest in the marital spectacle was so great that the cake merited entire news articles devoted solely to its description. The impressive confection, made by Mme Blanche of New York, who had also provided Alice Roosevelt’s cake, was described as a simple design set off by “a Persian vase, supplied by the bride-to-be, in the center,” which held a bouquet of orchids. A similar cake was made for the express purpose of filling 125 small white boxes for guests to take home.15 There was not enough cake to be sent to the writers of the hundreds of letters that arrived at the mansion asking for a slice;16 instead the public had to be satisfied with a photograph. This wedding marked the first time the public was able to see the actual cake in photograph form, rather than imagining it from written description.

Eleanor Wilson was wed in the White House less than a year later. Her cake, while described as “not nearly so large as that at the wedding of Miss Jessie Wilson,” was still “imposing with its mounds of white icing,” and a miniature chapel decorated the top. Pieces of the cake were placed in white boxes for guests and “dozens of boxes were sent broadcast over the country” to friends.17 Eleanor and Jessie’s cousin, Alice Wilson, was the next White House bride, in August 1918, with a cake described simply as “a typical bridal cake, a ‘white’ cake of large size ornamented only with fancy frosting.”18

1913 Jessie Wilson and Francis Bowes Sayre 1914 Eleanor Wilson and William Gibbs McAdoo

Jessie Wilson (above) selected a Persian vase filled with orchids to top off her wedding cake in 1913. The cake made for her sister Eleanor (below) the following year was topped with a miniature chapel.

68

ALL IMAGES: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

69

Almost a quarter of a century passed before the next White House wedding. In 1942, Harry Hopkins, an adviser to President Franklin Roosevelt, married Louise Macy in the upstairs Oval Room. It was a simple ceremony featuring a cake frosted with the couples’ signs of the zodiac and sculpted by Roosevelt intimate Eric Gugler, the architect of the new West Wing.19

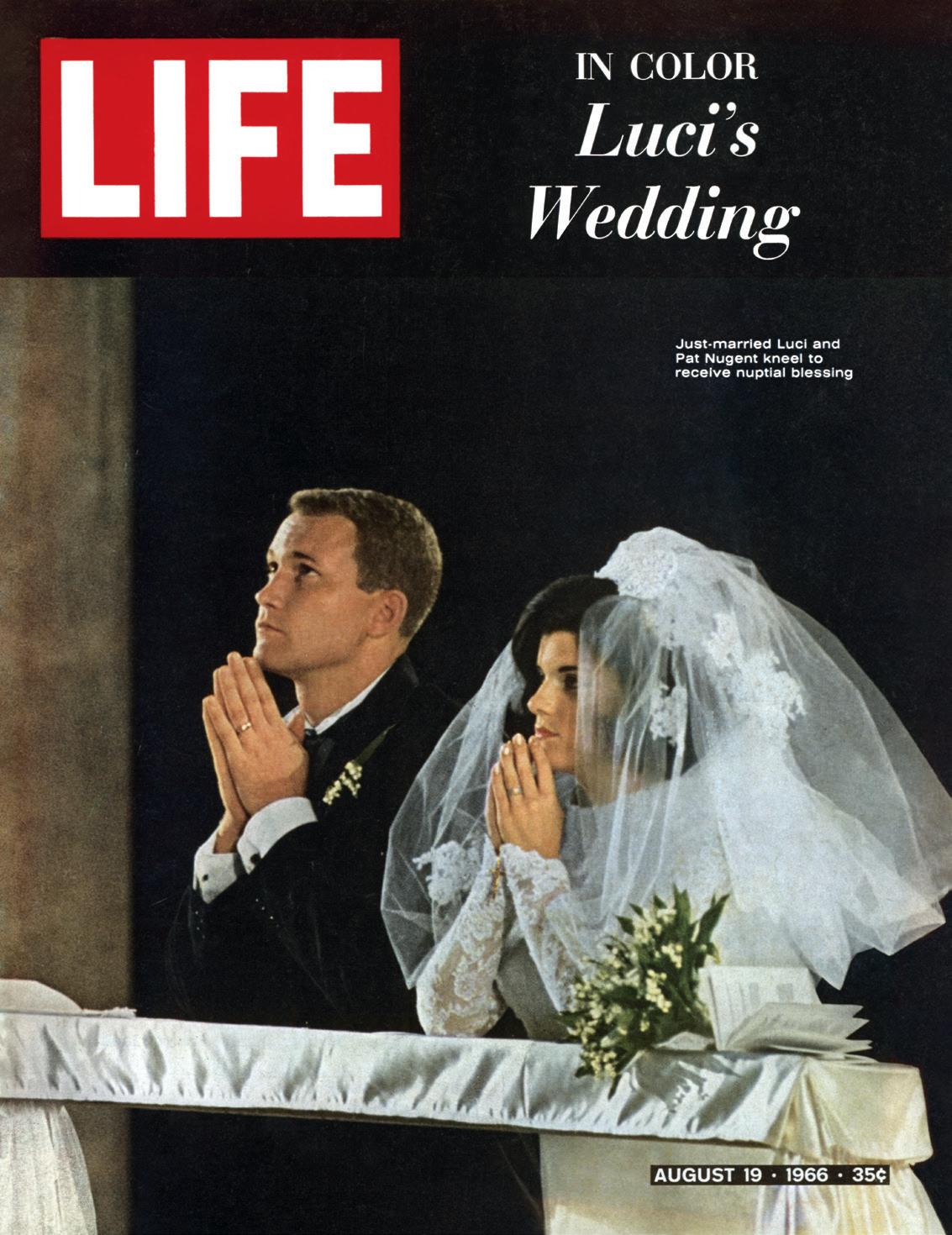

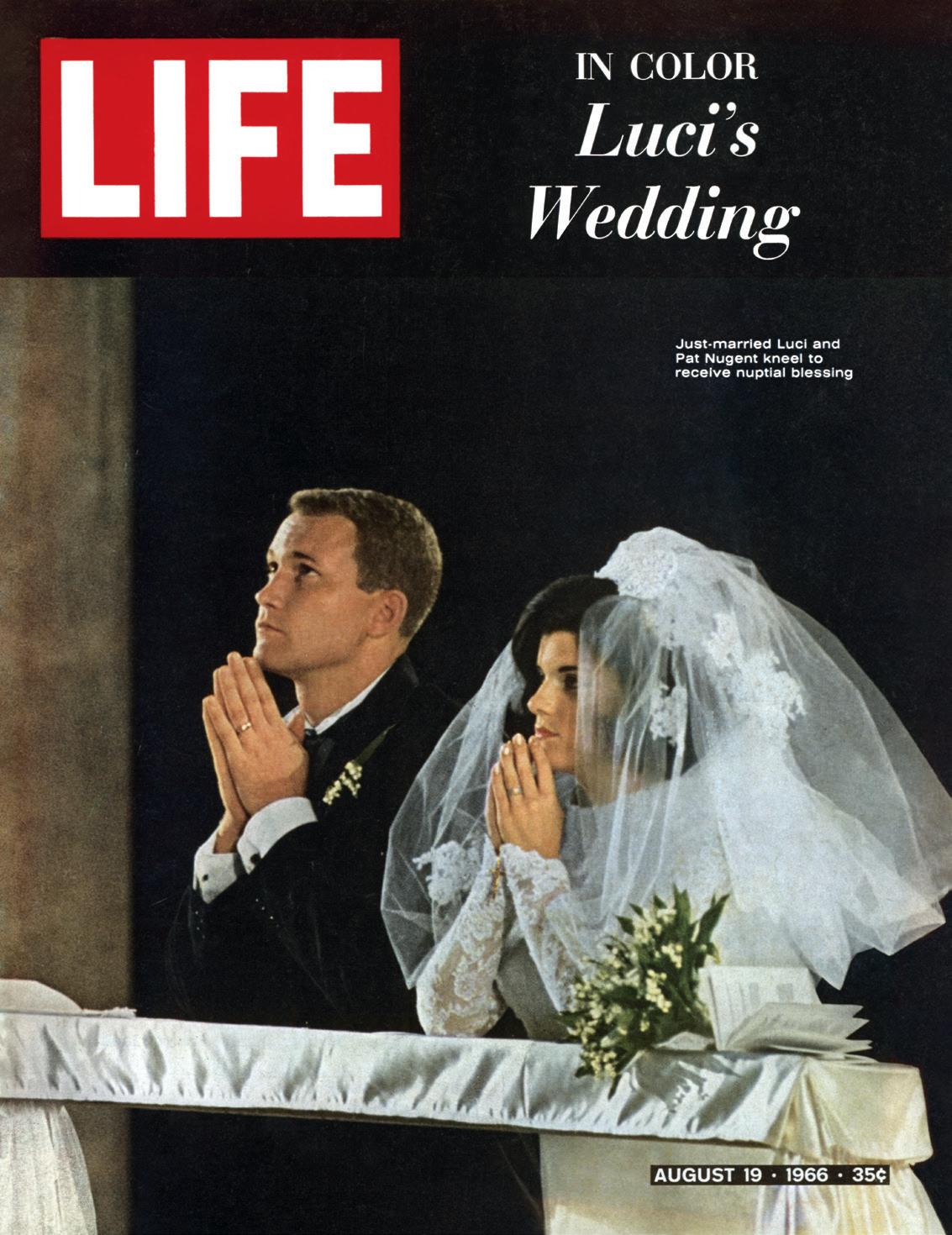

The White House did not see another wedding for more than twenty years, but the next one changed how the American public was able to witness the wedding cake and all its symbolism. In 1966, Luci Baines Johnson, daughter of President Lyndon B. Johnson, married Patrick Nugent at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, and then the couple returned to the White House for a reception. The wedding cake was a seven-tier summer fruit cake decorated with sugar swans, roses, and lilies of the valley. The newspapers showed photographs of the cake and reported that each guest received a slice to take home “in a white satin covered, heart-shaped box bearing, in gold, the initials of the bride and groom.”20 One slice in its box was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, marking a new way for Americans to participate in White House weddings, for they could view the actual cake, even years after it was the ritual centerpiece at the reception. Moreover, the recipe for the cake was released to the newspapers so that those interested then and now might make their own versions.21

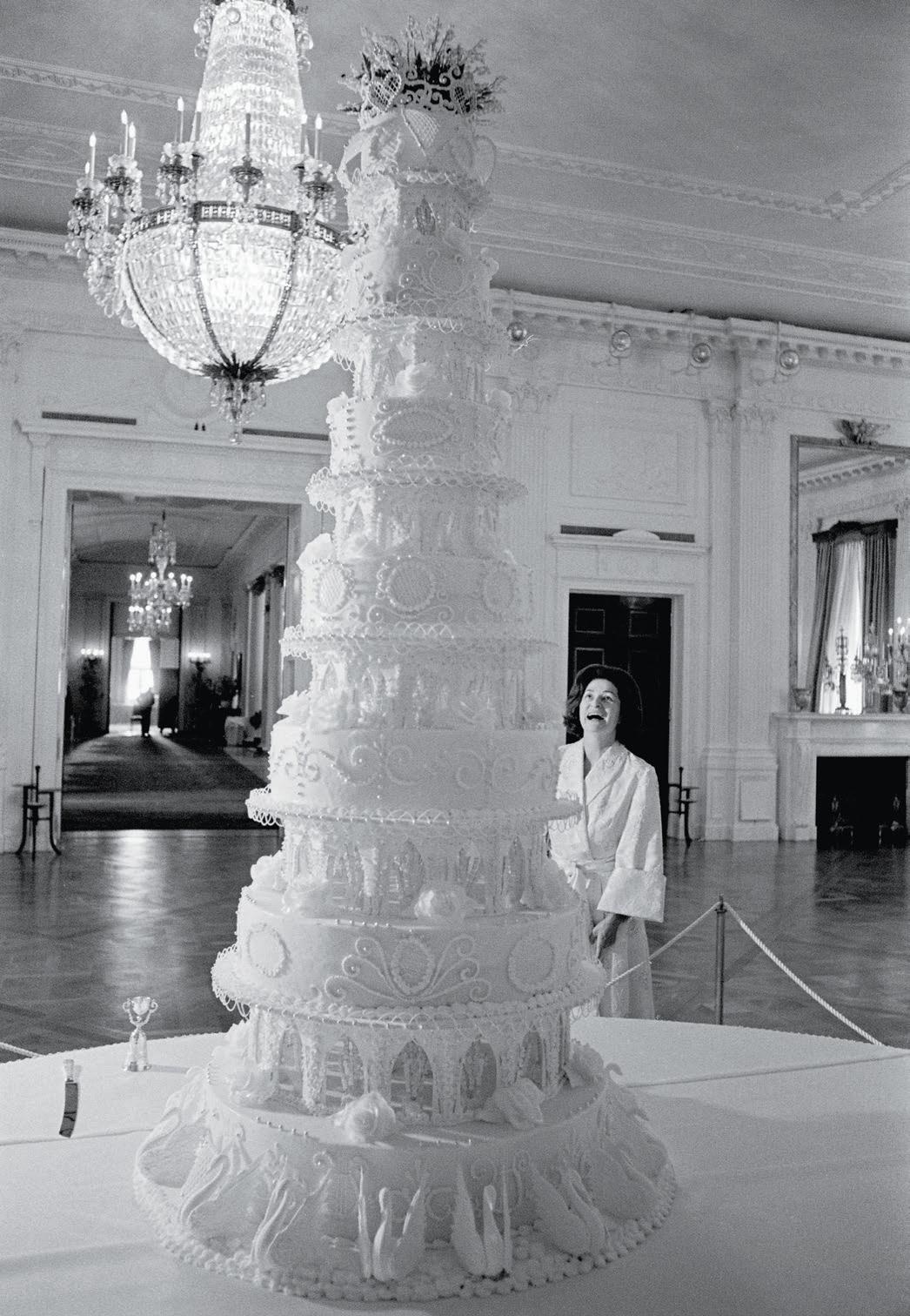

Luci Johnson’s wedding cake was a seven-layer summer fruit cake, baked well ahead of the event and decorated with sugar swans, roses, and lilies-of-thevalley. White House pastry chef Ferdinand Louvat and New York pastry chef Maurice Bonté stood on scaffolding to assemble the cake in the East Room. First Lady Lady Bird Johnson’s pleased reaction was captured when she previewed the cake ahead of dressing for the wedding. The bride and groom cut the cake during the reception as the president looked on, and guests were given slices to take home in heart-shaped monographed boxes, one of which (cake included) is preserved in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

This recipe (right) for the top layer of the cake, a small bride’s cake for the couple to take on their honeymoon, was a favorite of Luci’s and shared by Mrs. Roy Folk Beal, a mother of bridesmaid Betty Beal.

1966 Luci Baines Johnson and Patrick Nugent

70

DETAIL AND CUTTING OF CAKE: GETTY IMAGES / RECIPE AND MRS. JOHNSON: LBJ LIBRARY ALL OTHERS: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

chocolate cake

1 stick margarine or butter

2 cups sugar

2 cups regular flour, sifted

2 eggs

1 tablespoon vanilla

½ cup buttermilk

2 squares unsweetened chocolate

1 cup hot water

1 teaspoon baking soda

Melt chocolate in double boiler. Cream butter and sugar, add eggs. Sift flour and add alternately with milk, then add ½ cup hot water to melted chocolate. Put other ½ cup water in a pan and bring to a boil (this is important). To this add soda and immediately add this to chocolate mixture. Pour chocolate mixture into the batter, add vanilla. Bake in greased loaf pan at 325˚F. Cake will pull away from sides of pan when done.

in

*Mrs. Beale does not ice the cake. She says it is at its best by the third day, grows more moist with age. She wraps it in foil and keeps it in the refrigerator.

71

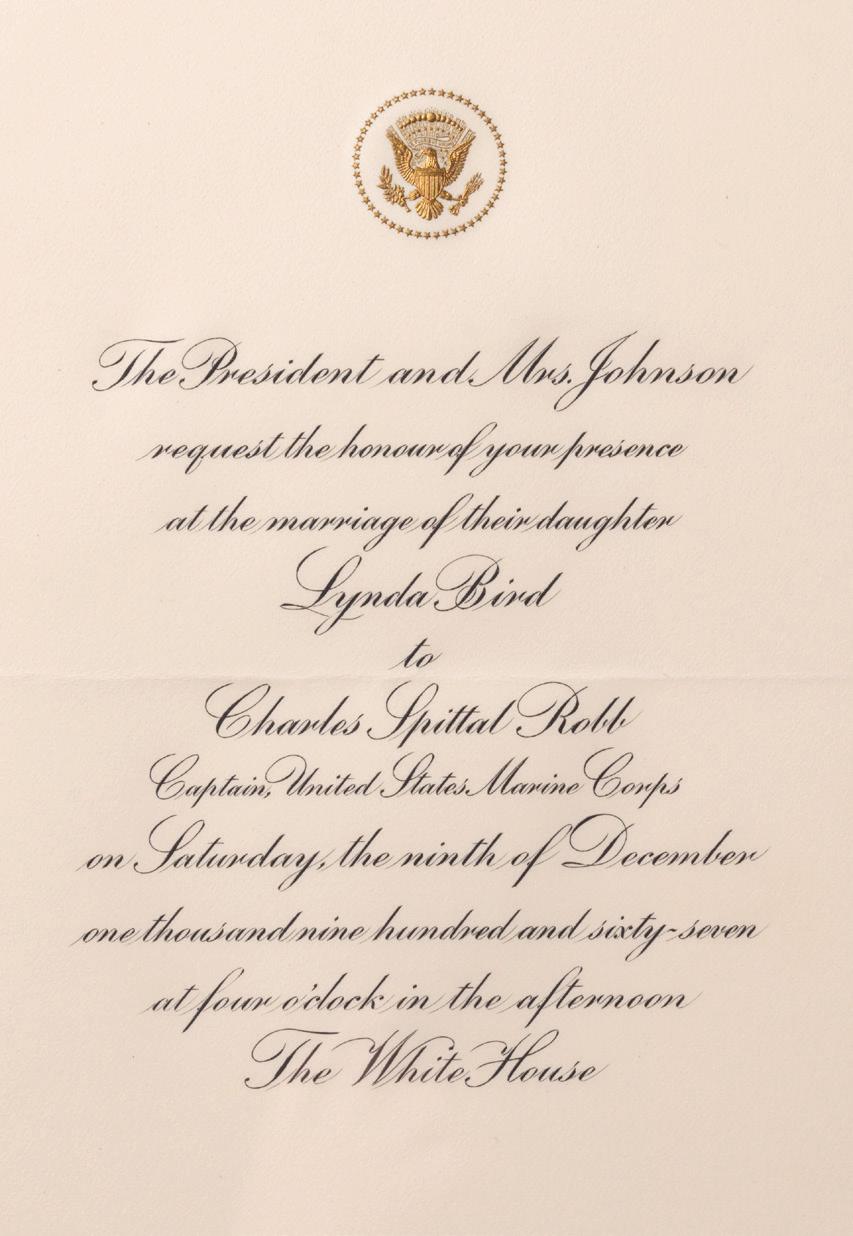

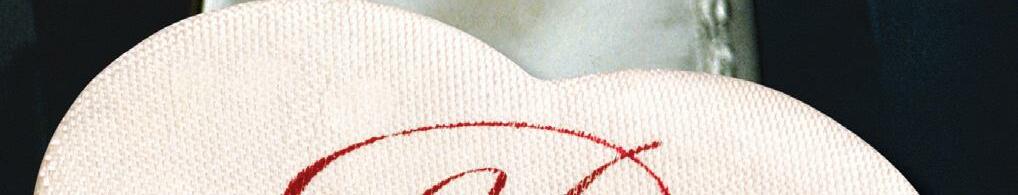

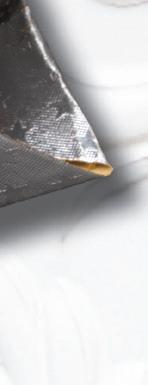

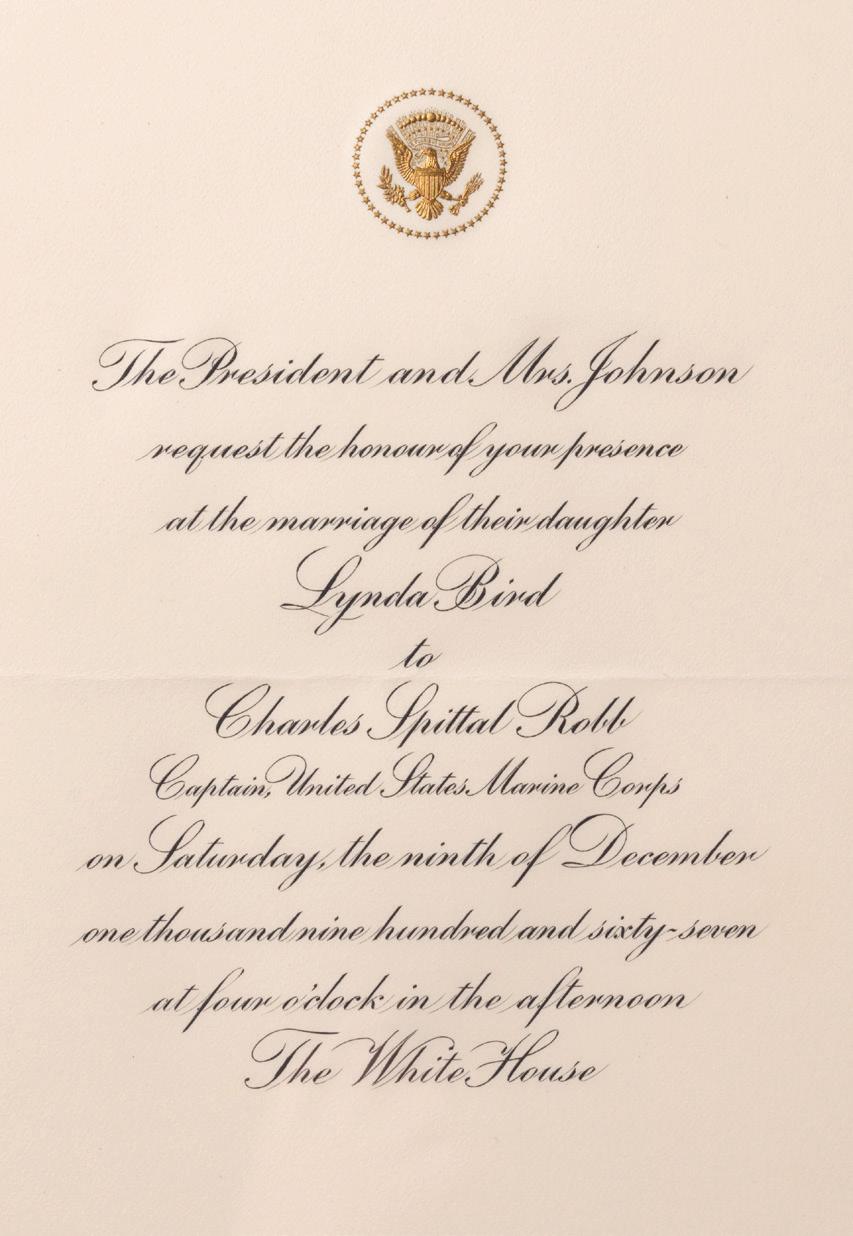

The following year, when Luci’s sister Lynda married Captain Charles Robb in the East Room of the White House, the recipe was also released to the newspapers. The rich, old-fashioned pound cake with raisins was 6 feet tall, weighed in at 250 pounds, and was decorated with sugar scrolls, roses, and love birds. Small squares of the cake were “wrapped in red foil on a red lace tart . . . packed in a heart-shaped box of white satin,” and given to guests as favors.22 Again a box with cake inside was donated to the Smithsonian.

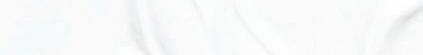

1967 Lynda Bird Johnson and Charles Robb

opposite

Newlyweds Lynda and Chuck Robb are seen making a ceremonial first cut of their wedding cake with Captain Robb’s sword, a tradition in military weddings. The recipe for the old fashioned pound cake was released for publication prior to the ceremony so that people could bake their own version. Small pieces of the cake, measuring approximately 1½ inches square, were given to guests in heart-shaped boxes to take home. The piece pictured here was sent to the Smithsonian Institution as part of the press packet and remains in the collection of the National Museum of American History.

old fashioned pound cake

1 pound powdered sugar

1 pound butter

1 pound cake flour

12 eggs

Flavor with mace and lemon rind.

Whip butter until light, add sugar, and mix for three minutes. Add eggs, two at a time, and continue to mix. Add flour and mix lightly but fully. Bake in paper lined pans at 275 degrees for about 1 hour.

*Note: Lynda Johnson Robb’s cake included raisins.

72

CUTTING OF CAKE: GETTY IMAGES ALL OTHERS: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

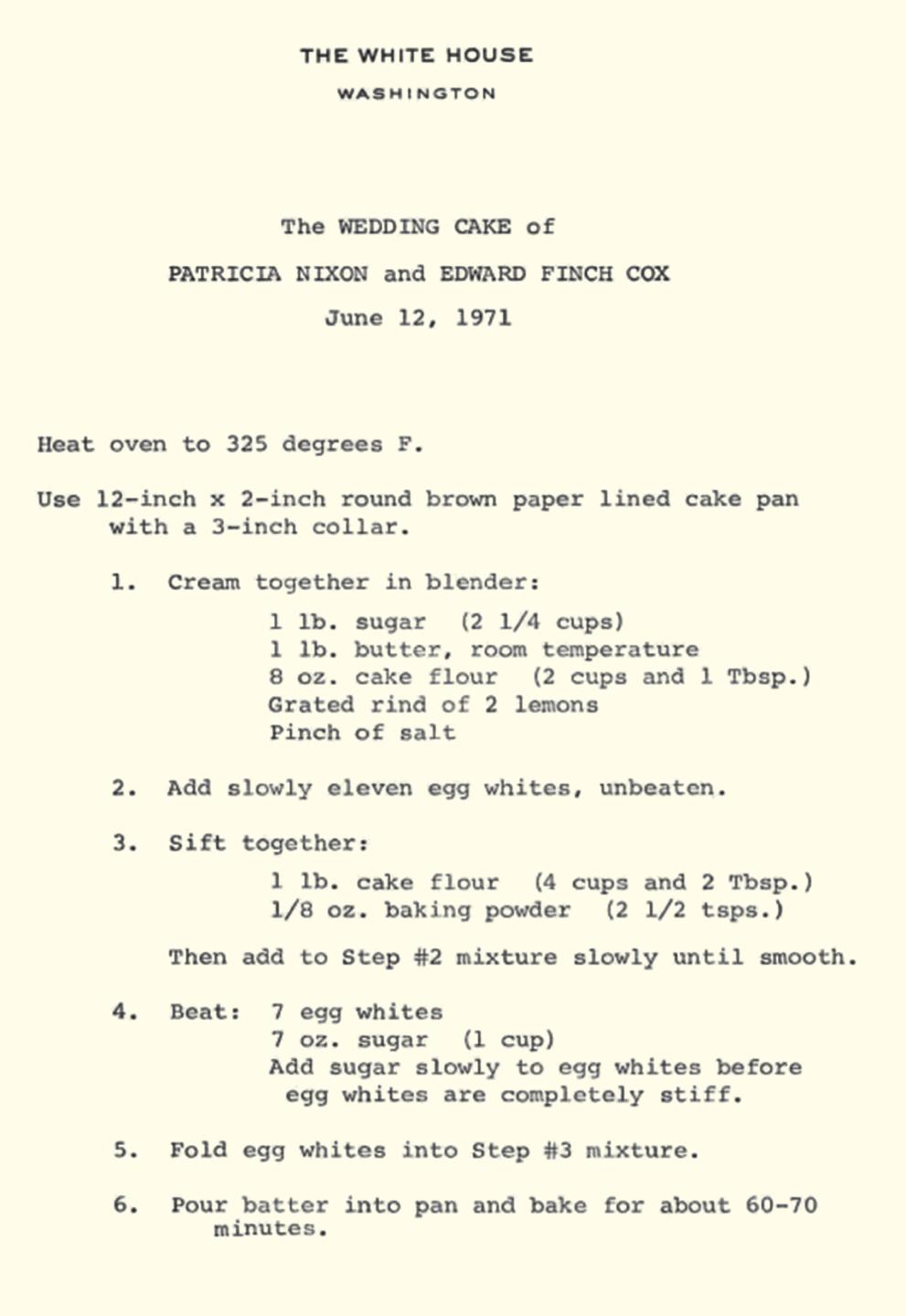

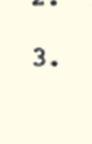

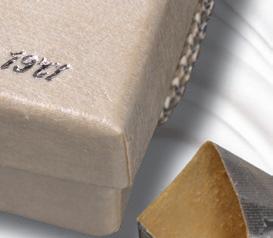

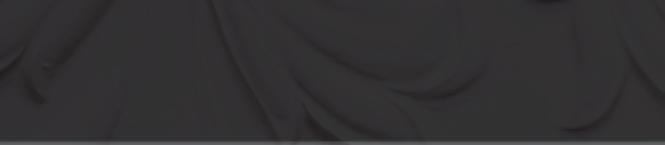

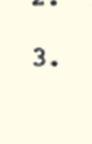

The next White House bride’s cake was for the wedding of Tricia Nixon, daughter of President Richard Nixon, and Edward Cox. It was also shared with the public via a donation and the release of the recipe in advance. But home bakers and food critics declared their results for the lemon pound cake recipe a soupy mess, speculating that the White House had erred in the number of egg whites versus whole eggs. The debate surrounding the recipe was labeled “The Great Cake Controversy” by the New York Times. 23 Fortunately for all involved, the recipe came together beautifully for the wedding It was a “six-tiered . . . 350 pound, lemon-flavored pound cake . . . standing six feet . . . decorated with blown sugar love bird[s] and the initials ‘PN’ and ‘EC.’”24 The piece given to the Smithsonian after the ceremony still sits solidly in its box.

1971 Tricia Nixon and Edward Cox

right

Newlyweds Tricia Nixon and Edward Cox slice their wedding cake, a boxed piece of which joined slices from the two Johnson weddings in the collection of the National Museum of American History. Measuring approximately 2 inches square, the hardened cake now has the appearance of a dried sponge.

Prior to the wedding, newspapers chronicled the difficulty home bakers reported with the cake recipe released by the White House in advance of the wedding.

74

CUTTING OF CAKE: AP IMAGES ALL OTHERS: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

white house history quarterly

white house history quarterly76

To satisfy a public eager for a glimpse of the bride in her wedding gown and hungry for every detail including the flavor of the cake, the media have long made White House weddings front page news. Standing in as a “guest” for the American people, the National Museum of American History preserves reminders of the weddings in its collection. As seen in the display above, visitors to the Smithsonian can view cake boxes, programs, and photographs.

Standing in as a “guest” representing the American people, the National Museum of American History now preserves these three cake boxes, with the all-important cake itself still inside, though no longer edible. This tradition could, however, be changing. A recent White House wedding—that of Anthony Rodham, First Lady Hillary Clinton’s brother, and Nicole Boxer in 1994—was kept almost as private as those in the mansion’s early days, much to the chagrin of journalist Faye Fiore. “What have we come to?” she lamented when it became clear no details on the ceremony were forthcoming, “All we want to know is . . . What flavor is the cake?”25 There was no written description and no photograph. Is this the beginning of a new phase, a return to the first, earliest White House tradition, or simply a one-off? We will have to wait until the next White House wedding to know for sure!

NOTES

1. See, for the general history of the wedding cake, Simon Charsley, Wedding Cakes and Cultural History (London: Routledge, 1992); Carol Wilson, “Wedding Cake: A Slice of History,” Gastronomica 5, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 69–72.

2. “Bride Cuts the Cake; Sister Gets Ring; All Dance Tango,” Washington Post, November 26, 1913.

3. For more on the visual consumption of

nationalism in Victorian England, see Emily Allen, “Culinary Exhibition: Victorian Wedding Cakes and Royal Spectacle,” Victorian Studies 45, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 457–84.

4. Louisa Catherine Adams, diary, March 13, 1820, in A Traveled First Lady: The Writings of Louisa Catherine Adams, ed. Margaret A. Hogan and C. James Taylor (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014), 252.

5. Marie Smith and Louise Durbin, White House Brides (Washington, D.C.: Acropolis Books, 1966), 36.

6. Thomas Pendel, Thirty-Six Years in the White House (Washington, D.C.: Neale Publishing Company, 1902), 75–76.

7. “The White House Wedding,” Washington Post, June 19, 1878.

8. “Miss Folsom in the City,” Washington Post, June 2, 1886.

9. “Married!” Washington Post, June 3, 1886.

10. “His Wedding Day,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 2, 1886.

11. “Mrs. Grover Cleveland,” Harper’s Bazaar, July 24, 1886.

12. See the websites of the Grover Cleveland Birthplace State Historic Site in Caldwell, New Jersey, www.nps.gov and https:// presidentcleveland.org. Also see Eve M. Kahn, “Cakes for Celebrities, Coveted by Collectors,” New York Times, May 10, 2013.

13. “Good Fortune in All Omens,” Boston Daily Globe, February 17, 1906.

14. “Wedding Cake for Council,” Washington Post, February 20, 1906.

15. “Vase and Orchids for Wilson Wedding Cake,” New York Tribune, November 12, 1913.

16. “No Big Wedding Cake at Wilson Nuptial,” Atlanta Constitution, November 22, 1913.

17. “Secretary M’Adoo Weds Miss Wilson,” New York Tribune, May 8, 1914.

18 “Fifteenth White House Bride,” Washington Post, August 8, 1918.

19. Adelaide Kerr, “She Got the Job,” Washington Post, July 26, 1942.

20. Dorothy McCardle, “Real Lilies Crown the Cake,” Washington Post–Times Herald, July 26, 1966.

21. Louise Hutchinson, “Chefs Batter Up for Luci,” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1966.

22. “Lynda Bird Johnson Robb,” Washington Post–Times Herald, December 10, 1967, D1.

23. “No Retest, White House Decides,” New York Times, June 3, 1971.

24. Judith Martin, “Triumph of Wedding Tradition,” Washington Post–Times Herald, June 6, 1971.

25. Faye Fiore, “Keeping Lid on White House Wedding,” Los Angeles Times, May 20, 1994.

white house history quarterly 77

wedding cakes, its origins and implications, with particular respect to its role in

TOP LEFT: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS / TOP CENTER: RUTHERFORD B. HAYES PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY ALL OTHERS: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION