The White House and &

the white house historical association

Board of Directors

chairman

John F. W. Rogers

vice chairperson

Teresa Carlson treasurer

Gregory W. Wendt secretary

Deneen C. Howell president

Stewart D. McLaurin

Eula Adams, John T. Behrendt, Michael Beschloss, Gahl Hodges Burt, Merlynn Carson, Jean Case, Ashley Dabbiere, Wayne A. I. Frederick, Tham Kannalikham, Metta Krach, Martha Joynt Kumar, Anita McBride, Barbara A. Perry, Frederick J. Ryan, Jr., Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen

national park service liaison

Charles F. Sams III

ex officio

Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, Debra Steidel Wall (Acting Archivist of the United States), Carla Hayden, Katherine Malone-France

directors emeriti

John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Janet A. Howard, Knight Kiplinger, Elise K. Kirk, James I. McDaniel, Robert M. McGee, Ann Stock, Harry G. Robinson III, Gail Berry West

white house history quarterly founding editor William Seale (1939–2019) editor Marcia Mallet Anderson editorial and production manager Elyse Werling

senior editorial and production director Lauren McGwin senior editorial and production manager Kristen Hunter Mason editorial coordinator Rebecca Durgin consulting editor

Ann Hofstra Grogg consulting design Pentagram editorial advisory

Bill Barker

Matthew Costello

Mac Keith Griswold Scott Harris

Joel Kemelhor Jessie Kratz

Rebecca Roberts Lydia Barker Tederick Bruce M. White

the editor wishes to thank The Office of the Curator, The White House

contributors

mary jo binker is the author of If You Ask Me: Essential Advice from Eleanor Roosevelt and What Are We For? The Words and Ideals of Eleanor Roosevelt. She is a fre quent contributor to White House History Quarterly.

rebecca durgin kerr is the editorial coordinator at the White House Historical Association and a regular contributor to White House History Quarterly.

In a March 1963 episode of The Lucy Show, Lucy and her friend Vivian help their sons’ boy scout troup build a White House with sugar cubes. The president is so impressed that he invites all of them to the White House to unveil it, but chaos follows after the model is dropped on the train.

the Sparkle

mallet anderson

TELEVISION DEPICTS US PRES IDENTS AND THE WHITE HOUSE

t. walsh

COMES TO THE WHITE HOUSE TO STAY rebecca durgin kerr

WEST WING TAKES TELEVISION INTO THE WHITE HOUSE

the Scenes Memories of the Reinvention of Political Theater

freeman

TO SESAME STREET WITH THE FIRST LADIES

and Set Design

shogan

JACQUELINE KENNEDY’S TELEVISED TOUR OF THE WHITE HOUSE mary jo binker

UPSTAIRS AT THE WHITE HOUSE WITH TRICIA NIXON The Making of the 60 Minutes Televised Tour

F. CALDERONE

IT’S ACADEMIC AND WHITE HOUSE HISTORY Through the 60-Year Lens of the Longest Running Quiz Show on Television

kemelhor

MORE THAN A PHOTO-OP: PRESI DENTIAL PILGRIMAGES TO DISNEY PARKS

bemis

REALISM OF DESIGNATED SUR VIVOR A Story of Presidential Succes

stewart d. m c laurin

foreword

marcia mallet anderson editor, white house history quarterly

HOW TELEVISION Depicts U.S. Presidents And the White House

KENNETH T. IRRWALSH

william seale, founding editor of the White House History Quarterly, has written that the White House “is probably the most richly docu mented house in the world, and the premier sym bol of the American presidency.”1 A fundamental reason for this reputation is television. Television has depicted the presidency and the White House so frequently and, in many cases, so positively, especially in its entertainment programming, that it has led the way in shaping perceptions of these institutions. Perceptions of real and fictional pres idents and the White House as conveyed on televi sion tend to run deep and endure. Everyone knows that the president of the United States, the most powerful person on earth, lives in the White House. And the desire to learn more about this fabled piece of real estate and its chief occupant appears to be insatiable. Ever since it became widely available in the 1950s and 1960s2 television’s collective narra tive of the American presidency has reflected the ideals, successes, and failures of the United States and in many ways the culture and social norms of the country in the modern era.

Television popularized the president as a star, America’s “celebrity in chief,” and showed the White House as the place where decisions are made that fundamentally affect our lives and can transform the world. There is also a public desire, fueled by TV, for information about the first lady,

above President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy congratulate Pablo Casals as guests applaud following his performance in the East Room, November 29, 1961.

left Television cameras focus on First Lady Jackie Kennedy in the State Dining Room as she leads a televised tour of the White House, 1962.

previous

Phil Hartman, as Bill Clinton in 1992, and Dana Carvey, as George H. W. Bush in 1990, are two of many actors who mastered good natured presidential impersonations on Saturday Night Live

above

Among the iconic entertainers who performed in the East Room during the Barack Obama presidency were Aretha Franklin (top), 2015, and B.B. King (bottom), 2012.

the president’s children, presidential hobbies, food and beverage preferences, friends, leisure activities, reading choices, and even presidential pets.

Jacqueline Kennedy introduced millions of Americans to the White House on February 14, 1962, when she led CBS News on a tour of the Residence and the furnishings she had acquired to showcase American history. The tour, guided knowledgeably by the elegant and soft-spoken first lady, drew a huge TV audience of 80 million Americans, and it enhanced Mrs. Kennedy’s reputation as a cultural icon—successful, modern, beautiful, charismatic. She also generated massive attention to the White

House by organizing showy dinners and glam orous social events attended by featured famous writers, artists, scientists, and musicians such as cellist Pablo Casals and composer and pianist Igor Stravinsky.3

This tradition has continued, with the broadcast and cable networks providing breathless coverage of such extravaganzas. Among the most notable in recent years were the concerts organized by Barack and Michelle Obama, which featured iconic entertainers, especially African Americans such as Aretha Franklin, B. B. King, Patti LaBelle, John Legend, and Usher. The Obamas, the first African Americans to serve as president and first lady, said they wanted to demonstrate that the White House was open to everyone, including Black people who might have felt shut out in the past, and the pub licity helped them make this point. Many of the concerts were televised in full or in part.

Television contributed to the rise of a new breed of American leader—a charismatic, telegenic indi vidual who understood that a public figure’s image on TV could be vital to his or her success or failure. And television helped to make the White House one of the most recognizable buildings in the world, associated with American power, democracy, and leadership and forever connected to the individual presidents who lived there.

Media-savvy presidents have tried to link

themselves to the country through television in many ways. Richard Nixon, for example, started out effectively using television for his own purposes, such as with his Checkers speech, when, facing cor ruption allegations, he told a TV audience that he had done nothing wrong and saved his vice pres idential spot on Dwight Eisenhower’s ticket. He failed to impress TV viewers in his televised debates with John F. Kennedy in 1960, but in 1968 Nixon manipulated the medium with staged events and controlled access and persuaded the nation that there was a “new Nixon,” kinder and more engaging than the Nixon of the past. Part of his effort was an appearance on the popular and irreverent TV show Laugh-In, in which the straitlaced candidate played against type by reciting one of the show’s signature lines, “Sock it to me.”

Other presidents followed. As I pointed out in my book Celebrity in Chief, “Democratic challenger Bill Clinton achieved a new level of coolness in the 1992 campaign when he appeared on Arsenio Hall’s TV show and played the saxophone while wearing sunglasses.” President George H. W. Bush “was aghast. It wasn’t ‘presidential,’ he told aides, and he said he wouldn’t do such a thing.”4 But most recent presidents used television to great advantage. President Obama was a pathbreaker in dealing with television. He expanded presidential use of the medium to include not only appearing on the news casts of the broadcast networks ABC, CBS, NBC, and the cable news networks of CNN and MSNBC but also on daytime programs such as The Ellen DeGeneres Show and The View. And he appeared on the comedy TV shows of Jon Stewart, Jimmy Fallon, and David Letterman. As I have written, “Through it all, he . . . projected an image of an unflappable leader, a nice guy and family man, reinforced by nearly everything he has done.”5 Obama and his media strategists understood that the media in the United States were fractured and, to be an effective communicator to as many Americans as possible, he needed to appear on a variety of TV shows that appealed to diverse audiences.

The cultural historian Fred Inglis says that Hollywood created “the star” as a central figure in American culture by relentlessly promoting movie actors and actresses as charismatic and fascinat ing. John F. Kennedy, the first true “TV president,” claims Inglis, “achieved the same goal for himself

left Richard Nixon, while campaigning for the vice presidency in 1952, explained an $18,000 expense fund on national television. The appearance was nicknamed his “Checkers” speech because of the reference to his daughters’ cocker spaniel, seen here with the Nixon family at their Washington, D.C. home.

opposite

In an effort to portray himself as more engaging during his presidential campaign in 1968, Nixon famously appeared on an episode of Laugh-In, delivering the comedy show’s signature line, “Sock it to me!” The show’s hosts Dan Rowan and Dick Martin are seen (top left) on the set of the show. In response, Nixon’s supporters wave “Sock it to ‘em, Nixon!” signs during a campaign rally (top right).

above Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign is remembered in part for his unconventional saxophone performance on Arsenio Hall’s late night show.

right

Barack Obama, seen here on the Jimmy Fallon show in 2008, appeared on many daytime and late night programs during his campaign for president and during his time as president..

through the use of television to generate a spe cial aura around the White House and its prime occupant.”6

As I discussed in Celebrity in Chief,

Presidents are the repository for America’s dreams. Each is both the head of government and the ceremonial leader of the United States. . . . Presidents also are using some of the same techniques as entertainers, such as in-house TV producers and directors, stagecraft experts, makeup artists, advance teams, and writers. The goal is to create favorable images of the president and generate positive impressions, just as press agents and “personal managers” do for Hollywood stars.7

And the White House has become a prime source of material for the entertainment industry, especially television.

Presidents and White House officials are intent on projecting the best image possible. They have been brought up with television, something they have in common with nearly every other American. And they want TV to show appreciation of what they do and are very disappointed when that does not happen. Former Obama adviser Dan Pfeiffer told the Washington Post that journalists also want to gain favorable attention from televi sion, sometimes by playing themselves. “People in Washington are super insecure,” Pfeiffer said, and “also almost universally nerds growing up,” and they seek approval from “cool” Hollywood.8

I saw this dynamic firsthand at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, an annual gala in which the worlds of journalism, politics, govern ment, and entertainment combine for an evening of cozy comradeship. I served as president of the WHCA for a term and was on the board for many years. One incident stands out. Martin Sheen, star of the TV series The West Wing, attended several years ago as my guest. He showed up a bit late in the lobby of Washington Hilton Hotel, where the dinner was scheduled, and he could not resist shak ing hands with well-wishers at a rope line near the red carpet, with TV cameras capturing the inter actions. He broke into a huge grin when the spec tators shouted to get his attention—not using his own name but the name of the character he played on TV, “President Bartlet!” At a reception after his arrival in the lobby and just prior to the dinner,

Sheen was greeted warmly by the large crowd, many of whom sought photos with the famous actor. After a few minutes, Bill Clinton, the guest of honor, arrived and both he and Sheen noticed each other across the room. The crowd parted as Sheen and Clinton walked slowly toward each other like gunslingers in the Old West striding toward a showdown. At the last moment Clinton extended his hand with the greeting, “Mr. President,” and Sheen extended his hand and used the identical greeting, “Mr. President.” They shook hands and the crowd of journalists, politicians, government officials, and entertainers cheered. These insiders were delighted at the Clinton-Sheen connection, which blended government and politics with show business and TV.

Television has, by and large, projected a respect ful view of the presidency and individual presidents, both real and fictional. Of course, day-to-day tele vision news coverage of presidents and the White House is in a different category from that of enter tainment-oriented depictions of presidents on television, such as made-for-TV dramas, comedy programs, and documentaries. News coverage is dominated by the American tradition of adversary journalism in which reporters and editors are in a constant tug-of-war with presidents over how chief executives are portrayed as the media pur sues its watchdog role and tries to hold presidents accountable.

Television news coverage is certainly critical of the presidency, in keeping with the watchdog func tion and independence guaranteed to the Fourth Estate by the Constitution. But there is still an underlying respect for the office that even the most cynical journalists generally maintain. I know this firsthand. I was a White House correspondent for thirty years and have seen this respectful dynamic play out day after day. Reporters like to think of themselves as essentially critics and even scolds, but there is also a deep respect for the office of president and the White House as hallowed ground where history is made. Critical news coverage is often couched in the idea that a president is not living up the expectations for the office or not “act ing presidential.” Rarely is the office itself criticized. It is often idealized.

On the entertainment side of TV, the depictions of the presidents generally reflect public attitudes toward each leader at the moment. But it is almost always undergirded by a respect for the office

Kenneth Branagh stars as Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 2005 television movie Warm Springs, which tells the story of the future president’s battle to regain the use of his legs after contracting polio in the 1920s.

and, by implication, the democratic process, with recognition that the choice of every president is based on a vote of the people and the official elec tors. Overall, depictions of the real commanders in chief have been sharp-edged but not mean-spir ited. Take a look at the Saturday Night Live oeuvre and you’ll see what I mean, notably the brilliant impersonations of Alec Baldwin as Donald Trump, Will Ferrell as George W. Bush, Darrell Hammond and Phil Hartman as Bill Clinton, Dana Carvey as George H. W. Bush, and Hartman as Ronald Reagan, and Dan Aykroyd as Jimmy Carter and Nixon, and Chevy Chase as Gerald Ford.

President Kennedy probably has received the most positive attention across the board from tele vision. He has been played by fine actors, including Martin Sheen, William Devane, James Marsden, and Rob Lowe, and the portrayals mostly under score his charisma, good judgment, and inspira tional qualities.9

Franklin D. Roosevelt also has been treated pos itively. Consider Kenneth Branagh’s 2005 portrayal of him in Warm Springs, a made-for-television drama. The program focused on Roosevelt’s unsuc cessful attempts to regain the use of his legs, which were paralyzed from polio, and his commitment to

turn a resort in Warm Springs, Georgia, into a reha bilitation center for polio victims. This is where he learned empathy, which the drama accurately depicts.

Donald Trump, on the other hand, has often been portrayed negatively, as overbearing, bully ing and self-indulgent, but at the same time char ismatic. President Joe Biden, who took office in January 2021, so far has not provided the comic fodder or exhibited the charisma of some of his pre decessors. He has been less of a regular presence on television, including both entertainment and news shows. His image is a work in progress.

Fictional presidents have generally gotten pos itive treatment. Their TV portrayals often turn out to be tough but not overly harsh, reflecting Americans’ realistic view of their top leader as flawed but worthy of respect. The fictional presi dents are also more diverse than the real presidents, reflecting an idealized, aspirational view promoted by TV writers, actors, and directors. The list of the most popular White House–centric shows in recent years includes several women presidents, an African American, and a Latino. Among the notable depictions of fictional presidents on TV series were Martin Sheen as President Josiah (“Jed”) Bartlet on The West Wing (which aired 1999–2006); Jimmy Smits as President Matthew Santos on The West Wing; Geena Davis as President MacKenzie Allen on Commander in Chief (which aired 2005–06); Cherry Jones as President Allison Taylor on (which aired 2001–10); Dennis Haysbert as President David Palmer also on 24; Kevin Spacey as President Frank Underwood on House of Cards (which aired 2013–18); Robin Wright as President Claire Underwood on House of Cards; Julia LouisDreyfus as President Selina Meyer on Veep (2012–19); and Kiefer Sutherland as President Thomas Adam Kirkman on Designated Survivor (2016–19).

Among the highlights: President Bartlet as played by Sheen was idealistic, hardworking, and decent. On Veep, President (and, earlier in the show, Vice President) Selina Meyer played by Louis-Dreyfus was venal, preoccupied with power and perseverant as she struggled to overcome her limitations. Frank Underwood, played by Spacey in House of Cards, was cunning and clever though menacing and ruthless.

I have had the opportunity to interview Sheen twice for public programs offered by the Smithsonian in Washington, and he explained

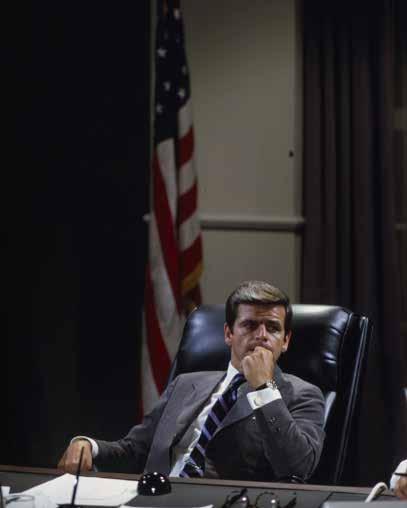

above Geena Davis as President MacKenzie Allen on Commander in Chief, 2006. right Kevin Spacey as President Frank Underwood on House of Cards, 2014.

opposite William Devane as President John F Kennedy in the made for television movie The Missiles of October, 1974.

above and right Author Kenneth T. Walsh discusses The West Wing with Martin Sheen during a public program at the Smithsonian Institution (above). Sheen will always be remembered for his role as President Josiah Bartlet on The West Wing (right).

how he tried to give his character a higher purpose.

Sheen wanted President Bartlet to be a committed Roman Catholic, as Sheen is in private life, so the commander in chief would always be grounded in morality and a clear set of values. Sheen’s por trayal is the most memorable and influential of any TV-series president because he reminded viewers of what the presidency could be and his character was infused with idealism. I was impressed that both Smithsonian programs with Sheen were sold out, and many attendees were young people. The show still has strong resonance across the generations.

It is clear that television has helped to make the presidency and the White House vital parts of our experience as Americans. And this connection will remain a fact of national life as we move deeper into the twenty-first century.

NOTES

1. William Seale, “White House History Quarterly Mission Statement,” provided by the White House Historical Association, April 2021.

2. “Number of TV Households in America,” table online at American Century website, www.americancentury.omeka.wlu. edu.

3. Kenneth T. Walsh, Celebrity in Chief: A History of the Presidents and the Culture of Stardom, With a New Epilogue on Hillary and “The Donald” (New York: Routledge, 2007), 98.

4. Ibid., 9.

5. Ibid., 11.

6. Fred Inglis, A Short History of Celebrity (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2010), 4, 10–11.

Walsh, Celebrity in Chief, 11.

Quoted in Hunter Schwarz, “Real-Life White House vs. Hollywood White House, According to Dan Pfeiffer,” Washington Post, March 12, 2015.

Greg Gilman, “16 Actors Who Played JFK, from Patrick Dempsey to Michael C. Hall,” posted June 5, 2018, The Wrap website, www.yahoo.com.

house

TELEVISION

Comes to the White House To Stay REBECCA DURGIN KERR

television has been a staple in American homes since the late 1940s and 1950s,1 and the White House is no exception. Presidents and first families placed TV sets in the West Wing and in rooms throughout the Residence so they could have up-to-the-minute news—and images—of current events even as they used broadcast television to communicate with the American people.2

In 1950, 9 percent of American households had televisions; by 1960, the number had grown to 87 percent.3 The technology had been a long time coming. It began in 1910 with the French inven tor Edouard Belin’s experiments for transmitting photographs, and it was he who began using the term “television.”4 In 1912 the Washington Herald explained that “television” means “seeing at a dis tance.”5 World War I paused the development of television, but improvements in radio and wire communication continued to be refined during that time.6 During the 1920s Washington, D.C., inventor C. Francis Jenkins worked on a devise that could use radio signals to transmit images, and on June 13, 1925, he demonstrated his “radio vision” machine to U.S. officials, including the secretary of the navy. The Sunday Star stated that “it was heralded as the first time in history that man has literally seen far-away objects in motion through the uncanny agency of wireless.”7 In 1929, Jenkins flew an airplane over Washington and used the

“aerial eye” camera to transmit overhead images of the city’s monuments and buildings via radio waves to a transmitter in a laboratory.8 Experiments in Europe were also successful in transmitting images at this time.9

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose radio broadcasts, called fireside chats, spoke directly to the American people,10 was the first president to be televised. On April 20, 1939, his speech commu nicating the opening of the New York World’s Fair was broadcast in the New York area.11 The demon stration of this new technology excited Americans, but prices for TV sets were much too high for most people and uniform standards for broadcasting and viewing had not yet been established. The Federal Communications Commission announced that television “commercial service could begin on or after 1 September 1940,” 12 and some thought that the presidential Inauguration in 1941 would be broadcast; that did not happen until a decade later.13 World War II interrupted television broad casts, but technological developments during the war helped advance television after the war, and by the end of the 1940s the boom in television sales had begun.14

President Harry S. Truman was the first to allow television cameras in the White House. He gave the first televised speech from the White House on October 5, 1947, urging Americans to

conserve food to help prevent starvation in post war Europe. The three local Washington, D.C., stations combined their equipment to broadcast the speech to Washington, Philadelphia, New York, and Schenectady, New York.15 In 1949 President Truman also became the first to have his inaugu ral celebrations televised.16 During the renovation of the White House (1948–52), wiring for televi sion was installed in just about every room. The Evening Star stated, “In bedrooms and other rooms television sets could be plugged in for programs from practically anywhere in the country, carried over special wires. The screens were tuned in by a special dial arrangement connected with a central control system.”17 At the end of his term, on May 3, 1952, President Truman gave a televised tour of the completely renovated White House.

By the time of the 1952 presidential election, Americans were accustomed to seeing the pres ident on television but were just getting used to televised campaigning.18 Some attributed Dwight D. Eisenhower’s win to his TV commercials.19 The Inauguration on January 20, 1953, was televised

above

Viewers watch as President Harry S. Truman addresses the United Nations, October 25, 1946.

above and right

A family gathers around an early RCA television to watch President Truman’s Inauguration—the first Inauguration to be televised, January 20, 1949.

opposite Schoolgirls in New York City view President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s televised Inauguration during their lunch period, January 20, 1953.

right President Eisenhower consults with television adviser Robert Montgomery following a radio and television report to the nation, June 27, 1960.

below President Eisenhower announces that he will run for a second term during a broadcast from the White House, February 29, 1956.

and demand was high for Eisenhower to appear on television during his first year in office.20 The Key West Citizen stated, “We think the televising of some of the President’s press conferences would not only be educational for the average citizen, but would be an extremely interesting show.”21 After film and television actor Robert Montgomery was brought to the White House to advise Eisenhower on how to present himself on television, presi dential press conferences began to be televised. Montgomery served the president as a media con sultant for seven years.22

Through television, Eisenhower spoke directly to the people at times of crisis, an expectation that continues to the present day. In September 1957, when mobs threatened to prevent the court-or dered integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, he returned from vacation in Newport, Rhode Island, to address the nation from the White House

I could have spoken from Rhode Island, where I have been staying recently, but I felt that, in speaking from the house of Lincoln, of Jackson and of Wilson, my words would better convey both the sadness I feel in the action I was compelled today to take and the firmness with which I intend to pursue this course until the orders of the Federal Court at Little Rock can be executed without unlawful interference.23

In his 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy used television to reach a wide audience, and his poise on camera during the presidential debates helped him defeat Richard Nixon, who appeared less comfortable on television.24 As pres ident, Kennedy had a television set, which he called “that little gadget,” installed in the Fish Room (now called the Roosevelt Room) in the West Wing,25 and on a small television he and members of his admin istration watched the lift-off of Astronaut Alan B. Shepard’s flight into space. In 1961, Kennedy began televising live press conferences.26 To improve his on-air image, Kennedy rewatched press confer ences and brought in Franklin Schaffner, a film and television director, to assist in the setup of cameras and lighting.27 Taping sessions were orchestrated like movie productions. Like Eisenhower, Kennedy went on television to address the American people directly during crises over school desegregation.28 But perhaps the most famous televised event of the Kennedy administration was First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s tour of the White House in February 1962.29 Photographs from the Private Quarters show that by the next year there were console tele vision sets in the Lincoln Sitting Room and the president’s bedroom.

opposite top Senator John F. Kennedy makes a charismatic appearance during a televised presidential debate with Vice President Richard Nixon, October 21, 1960.

opposite below President and Mrs. Kennedy are joined by Vice President Lyndon Johnson and others in the president’s secretary’s office to watch as Alan Shepard takes off in the Mercury capsule Freedom 7 to become the first American to make a suborbital flight, May 5, 1961.

right President Lyndon Johnson watches coverage by three networks on his bank of televisions in the Oval Office as the Saturn 1B rocket lifts off, October 11, 1968.

President Lyndon B. Johnson had not one but three television sets installed in his bedroom and in the Oval Office, so he could watch the news on all three networks at once. His reliance on television to provide him with current information was so acute that his secretarial staff noted in his Daily Diary on September 18, 1966, when Johnson was aboard the presidential yacht Sequoia, that “the televi sion reception was not good, and at one point the President thought he might go back to Washington so he could get good TV reception.”30 By Johnson’s time, it had become conventional for presidents to use television to speak directly to the American people at times of crisis. He addressed the pub lic often, particularly regarding the course of the Vietnam War, and on March 31, 1968, during one of these addresses, he stunned viewers by announcing that his would not run for reelection as president.31

Following television’s slow introduction to the White House in the 1950s and 1960s, its service to presidential ambitions has increased rapidly and its relationship to the presidency become ever more complex. By the end of the Johnson adminis tration, its role in the American presidency was well established. Like Johnson, subsequent presidents,

to a greater or lesser degree, watched television news and commentary to get a sense of public opinion. They went on television to reassure the American public in times of crisis and to impress the American people as well, with events that were carefully staged. Kennedy had watched Shepard’s lift-off into space; subsequent presidents had themselves televised as they watched astronauts in space on White House televisions and spoke to them in messages meant for all Americans, who were also watching. With the arrival of cable news networks, coverage and analysis of the presidents were pretty much 24/7. From the White House, presidents could watch not only space launches but congressional debates, hearings, and votes, all in live time on flat-screen TVs, ubiquitous throughout the West Wing and the Private Quarters but often hidden behind cabinet doors. And, with the arrival of social media, presidents no longer needed to rely on television addresses to get their messages to the American people. With the arrival of video confer encing, they no longer needed to meet with world leaders in person. As new technologies develop, we can expect that future presidents will continue to adopt them.

Richard Nixon, having been upstaged by John F. Kennedy during the televised debate in 1960, took a different approach to winning the 1968 presi dential election. Capitalizing on his reputation for being stiff in front of TV cameras, he appeared in a brief segment of the popular television comedy show Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In, looking stu diously perplexed and repeating one of the show’s favorite lines as a question: “Sock it to me?” One of the first things Nixon did as president was to move Johnson’s three-monitor television to the Executive Office Building (EOB).32 In 1971, President Nixon created the White House Television Office to work along with the television networks to showcase the president’s daily routine for the American public. He and his staff appeared on news and talk shows, and the wedding of his daughter Tricia was tele vised, as was his 1972 trip to China.33 From the Oval Office, in July 1969 Nixon watched the Apollo XI mission on two television sets, one pulled toward the desk and the other closer to the wall. In 1973, Nixon announced to the American people that he would resign the presidency.

At the suggestion of his press secretary, Ron Nessen, President Gerald Ford held an outdoor televised press conference in the Rose Garden in 1974.34 Like his predecessor, Ford watched the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project crew July 18, 1975, on television from his desk in the Oval Office, and he communicated with them via radio-telephone. Also like his predecessor, Ford appeared on a TV com edy show, delivering the famous opening line, “Live from New York, it’s Saturday night,” from the Oval Office for the April 17, 1976, episode of Saturday Night Live 35 President Ford enjoyed having break fast in his private dining room while watching tele vision on a portable set that could be moved around or hidden from sight.

Adapting the informality of President Roosevelt’s radio fireside chats to television, President Jimmy Carter televised his first fireside chat on February 2, 1977. He and his family enjoyed watching television, both upstairs in the Residence and in the so-called “Little Theater,” where they watched the Voyager spacecraft’s Jupiter encounter on closed-circuit television.36

Two televisions are set in place in the Oval Office near President Nixon’s desk ahead of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

above President Gerald Ford often watched a small portable television that could be moved from room to room. right President Jimmy Carter on television during his first fireside chat at the White House, 1977.

President Ronald Reagan’s acting experience in film and television earned him the title “Great Communicator,” for his skill in using the medium of television throughout his presidency.37 During a May 18, 1985, interview with Chris Wallace, he described his technique for reading the tele prompter in the Oval Office,38 where he often held large press briefings in front of multiple cameras. Evaluating his performances, he was able to watch himself on television on sets placed on carts that could easily be moved from room to room in the White House and West Wing. He announced the government-supported advent of closed caption ing, which permitted hearing-impaired Americans to experience television: “The recent initiation in March 1980 of closed-captioned television, which opened this important communications medium to millions of deaf and hearing-impaired Americans, is a significant achievement toward this end.”39

President George H.W. Bush, too, watched tele vision on a small TV set that could easily be moved around. By this time war itself was televised, and on January 16, 1991, President Bush watched the

commencement of Operation Desert Storm from the Oval Office. He used the platform of televi sion to broadcast public service announcements and was proud that he appeared on tv to talk to young Americans about not taking drugs.40 First Lady Barbara Bush often watched her husband’s television appearances in the Private Quarters of the White House.

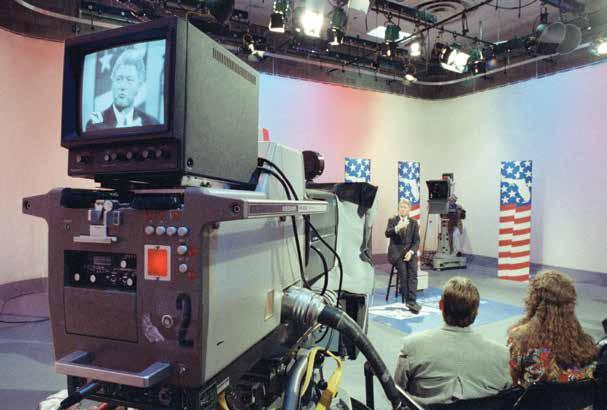

Like some of his predecessors, Bill Clinton used television as a campaign tool when running for president, making forty-seven appearances on talk shows, the most notable of which was when he played the saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show 41 As president, he took advantage of the nearly 24/7 news broadcasts to watch, for example, the tele vised debate between Vice President Al Gore and Ross Perot on the North American Free Trade Agreement and then the vote in Congress on the treaty. Clinton’s 1997 Inauguration was the first time the internet was used to broadcast the events live.42 Scandals involving President Clinton and the resulting impeachment proceedings were heavily televised.

above President Ronald Reagan evaluates a recent televised appearance by viewing televisions set up on carts in the Cabinet Room, October 16, 1986.

AP IMAGES

right President George H. W. Bush watches television coverage of Operation Desert Storm in the in the study adjacent to the Oval Office, January 16 1991.

above Bill Clinton appears on Florida Talks to Clinton: A Town Meeting, in one of many televised appearances made during his campaign for president, September 1992.

Communicating with space crews from the Oval Office continued during the George W. Bush pres idency. From the Roosevelt Room, he was able to wave to the crew of the Space Shuttle Discovery while talking to them on the phone. A remote cam era provided overhead views of President George W. Bush welcoming Mexico’s President Felipe Calderon to the Oval Office on January 13, 2008. Sharing a meal, President Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney watched television coverage of xxx [?] on February 7, 2008. Continuing the tradi tion to speaking directly to the American people through television at times of crisis, President Bush appeared on television to reassure the American people after the events of September 11, 2001, and to inform the public of the progress made during the Iraq War.

From his private study off the Oval Office, President Barack Obama was able to watch Press Secretary Robert Gibbs’s first press briefing on January 22, 2009. He was also able to watch as First Lady Michelle Obama broke ground for the White House vegetable garden on March 20, 2009. This was on a flat screen TV displayed in a wall cabinet. President Obama often conducted televised inter views in the Map Room of the White House. When he watched the launch of the Space Shuttle Atlantis on July 8, 2011, he was able to see split screen cov erage, a great advance over the triple televisions of the Johnson era. In addition to televised interac tions, the Obama administration was the first to use the social media platforms of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat to reach a wider audience on the internet.43

President George W. Bush waves to the crew of the Space Shuttle Discovery August 2, 2005, during a phone call from the Roosevelt Room.

With televisions available throughout the White House, President Obama could follow the news throughout the day. He watches television coverage of his wife, First Lady Michelle Obama, breaking ground for the White House vegetable garden (top), March 20, 2009. And he catches the launch of the Space Shuttle Atlantis on a television in the Outer Oval Office (bottom), July 8, 2011.

Before he was elected president, Donald J. Trump had extensive network television experi ence.44 As president Trump participated in vari ous television interviews at the White House and a Meet the Press interview was taped outside in the garden on June 21, 2019. He was also an avid follower of the TV coverage of his administration. During the coronavirus crisis, his task force pro vided lengthy televised updates daily. Television news programs regularly published President Trump’s Twitter posts to reach those viewers that did not follow him on social media. Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, President Trump and his suc cessor, Joe Biden, relied on video conferencing dis played on televisions to communicate information from health officials directly to the American peo ple. President Biden employed video conferencing to preform virtual swearing in ceremonies of top aides and officials. This procedure not only legal ized the oaths of office but followed the health man dates of all parties involved during the pandemic. Looking towards the future, the White House will continue to keep pace with the changes in television technology and the broadcasting of vital informa tion to the American public and the world at large.

notes

1. Susan Briggs, “Television in the Home and Family,” in Television: An International History, ed. Anthony R. Smith (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 192.

2. John Anthony Maltese, Spin Control: The White House Office of Communications and the Management of Presidential News (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 5.

3. “Number of TV Households in America,” table online at the American Century website, www. americancentury.omeka.wlu. edu.

4. “Seeing by Wire,” Deseret Evening News, April 12, 1910, 6.

5. “What of the Future in Electricity?,” Washington Herald, March 17, 1912, magazine sec. 6.

6. Albert Abramson, “The Invention,” in Television, ed. Smith, 18–19.

7. “‘Radio Vision’ Shown First Time in History by Capital Inventor,” Washington Sunday Star, June 14, 1925, 1.

8. “Television’s New Aerial ‘Eye’ for War and Peace Broadcasting,” New Britain (Conn.) Herald, August 23, 1929, 25.

9. Philip Kerby, “Gangway for Television!,” Washington Evening Star, March 12, 1939, 4, 11.

10. “Communicator-in-Chief: How Presidents Use the Media,” interview by Ted Koppel, Sunday Morning, CBS, May 10, 2020. www/cbsnews.com.

11. “April 1939 Franklin D. Roosevelt Day by Day,” Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, available online at http://www.fdrlibrary. marist.edu; The Associated Press, “McLean Is Re-Elected As President of Associated Press,” Washington Evening Star, April 25, 1939, A-5.

12. Quoted in Abramson, “Invention,” 19.

13. Kerby, “Gangway for Television!,” 4, 11; Brian Wolly, “Inaugural Firsts,” posted December 17, 2008, Smithsonian Magazine, www. smithsonianmag.com.

14. Les Brown, “The American Networks,” in Television, ed. Smith, 265.

15. “First Televised Speech from the White House, Sunday, October 5, 1947,” Harry S. Truman Library, available online at https:// www.trumanlibrary.gov; “Three D.C. Stations to Televise Truman Food Plea Tomorrow,” Washington Evening Star, October 4, 1947, 1.

16. Wolly, “Inaugural Firsts.”

17. “White House Rewiring to Facilitate TV Use,” Washington Evening Star, January 26, 1950, A-28.

18. Harry MacArthur, “Here’s How the TV Cameras See the Presidential Candidates,” Washington Evening Star, January 27, 1952, C-8; Mary Ann Watson, “Television and the Presidency: Eisenhower and Kennedy,” in The Columbia History of American Television, ed. Gary R. Edgerton (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 211.

19. “Communicator-in-Chief.”

20. Watson, “Television and the Presidency: Eisenhower and Kennedy,” 214.

21. “Publicizing Eisenhower’s Press Conferences,” Key West Citizen, April 13, 1953, 3.

22. Watson, “Television and the Presidency: Eisenhower and Kennedy,” 205, 214–15. See also Martha Joynt Kuman, “Dwight David Eisenhower: The First Television President,” White House History, no. 20 (Fall 2007): 4–17.

23. Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock,” September 24, 1957, American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

24. Charles L. Ponce de Leon, That’s the Way It Is: A History of Television News in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 54; Watson, “Television and the Presidency: Eisenhower and Kennedy,” 222–25.

25. The White House: An Historic Guide (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2022), 212–13.

26. Maltese, Spin Control, 5.

27. Watson, “Television and the Presidency: Eisenhower and

Kennedy,” 225–26.

28. John F. Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights,” June 11, 1963, American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

29. Ponce de Leon, That’s the Way It Is, 54.

30. Lyndon B. Johnson, President’s Daily Diary, September 18, 1966, available online at Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum website, www.lbjlibrary.net.

31. Lyndon B. Johnson, “The President’s Address to the Nation Announcing Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam and Reporting His Decision Not to Seek Reelection,” March 31, 1968, American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu.

32. Maltese, Spin Control, 59, 76 145, 222.

33. Ponce de Leon, That’s the Way It Is, 54; Kathryn Cramer Brownell, “Gerald Ford, Saturday Night Live, and the Development of the Entertainer in Chief,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 46, no. 4 (December 2016): 925.

34. Gerald R. Ford, The President’s News Conference, October 9, 1974, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency. ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-78. Brownell, “Gerald Ford, Saturday Night Live, and the Development of the Entertainer in Chief,” 925;

35. Brownell, “Gerald Ford, Saturday Night Live, and the Development of the Entertainer in Chief,” 925.

36. Joel S. Schwartz, “The Promise of a Politician Scientist: President Carter and American Science,” in The Presidency and Domestic Policies of Jimmy Carter, ed. Herbert D. Rosenbaum and Alexej Ugrinsky (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994), 264.

37. Robert E. Denton Jr., The Primetime Presidency of Ronald Reagan: The Era of the Television Presidency (New York: Praeger, 1988), 3, 73.

38. President Reagan and Nancy Reagan, interview by Chris Wallace, NBC Special, May 18, 1985, Courtesy of Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, available online at, https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=EhIeW-fbYiM.

39. Ronald Reagan, Proclamation 5008—National ClosedCaptioned Television Month, December 29, 1982, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/ research/speeches/122982b.

40. George H.W. Bush, Remarks to Schoolchildren at the White House Halloween Party, October 31, 1989, George H.W. Bush Presidential Library, https://bush41library.tamu.edu/archives/ public-papers/1116.

41. Michael Tracey, “Non-Fiction Television,” in Television: An International History, ed. Anthony R. Smith (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 141.

42. Wolly, “Inaugural Firsts.”

43. Kevin Freking, “Obama Uses Social Media to Engage and Persuade,” AP News, January 4, 2017, available online at, https:// apnews.com/02a341c7ab814f0e903c681c5659af11/obama-usessocial-media-engage-and-persuade (accessed on May 12, 2020).

44. White House Historical Association, Donald J. Trump, https:// www.whitehousehistory.org/bios/donald-j-trump

THE WEST WING Takes Television Into the White House

Behind-the-Scenes Memories of the Reinvention of Political Theater

MARC FREEMANno one wants to watch political dramas , or so thought every major network executive in the late 1990s. Lawyers, guns, and money, sure. Lobbyists, gun control, and monetary policy? Not so much. Yet when The West Wing premiered in September 1999 in an environment designed for its failure, it somehow managed to change television and people’s opinions about public service.

Oscar-winning screenwriter Aaron Sorkin, Emmy-winning ER creator John Wells, and Emmy-winning director Thomas Schlamme joined forces to take audiences out of court and operating rooms and into the world of the great experiment of self-government designed by our Founding Fathers.

Foreign and domestic. Legislative and judicial. The show touched it all as seen through the eyes of the executive branch. Along the way, The West Wing delivered thought-provoking entertainment with attitude and style, giving us a glimpse into government’s potential.

So, how did it all come to pass? Some of the leading creative talent behind the scenes of the transformational program recently shared their memories with me. Their insights reveal how they helped reinvent political theater.

LAWRENCE O’DONNELL (writer/executive pro ducer): We never talked out loud about this but we were building a little house the shape of which no one had ever seen.

PAUL REDFORD (writer/producer): We were breaking the rule that you can’t make a successful drama on network television that isn’t some variation of cops, lawyers, or doctors responsible for saving lives. There can’t be any stakes less than that.

ELI ATTIE (writer/executive producer): Nuclear warheads. Housing and education. I think there’s no realm in which the stakes are greater. There’s no reason why a world of intensity and selflessness shouldn’t be a fascinating character drama.

DEBORA CAHN (writer/executive producer): You could talk about things that were meaningful in the world in a way where the entertainment and content are satisfying.

Previous attempts at political drama failed in part because they ignored partisan politics. The West Wing’s characters embraced their beliefs.

THOMAS SCHLAMME (executive producer/ director): The one thing you know when you go to Washington is people don’t hide their politics. It mat ters enormously. It’s where their passion comes from.

Nobody on the show was going rah-rah Democrats. Some of our biggest fans were Republicans. I think Washington thought we were trying to honor the public servants who were there.

KEVIN FALLS (co-executive producer/writer):

And we made the opposition party formidable, with mostly rational and informed arguments. No straw men.

above Martin Sheen during a script read-through. Executive Producer and Director Alex Graves recalled that the cast never failed to be blown away by Aaron Sorkin’s scripts.

previous spread

The Season 3 cast of The West Wing gathers in front of the Presidential Seal and on the set of the Oval Office. Left to right on page 34: Rob Lowe as Sam Seaborn; Dule Hill as Charlie Young; Stockard Channing as Abbey Bartlet; Allison Janney as Claudia Jean (“C.J.”) Cregg; Martin Sheen as President Josiah (“Jed”) Bartlet; Richard Schiff as Toby Ziegler; John Spencer as Leo McGarry; Janel Moloney as Donna Moss; and Bradley Whitford as Josh Lyman.

right

Rob Lowe, as speechwriter Sam Seaborn, made the potentially boring government work seem glamourous and fun to watch.

ATTIE: At the end of the day, Aaron’s and the show’s goal was to be entertaining first, second, third, and fourth.

To help Sorkin accurately capture the president’s workplace, he amalgamated atypical television writ ers with experienced political experts, like O’Donnell who had been a congressional aide to New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and staff direc tor for the Senate Finance Committee and later, Attie who worked in Clinton’s White House and as a senior speechwriter for Al Gore.

O’DONNELL : The problem for a TV political drama is that the most important work in govern ment is the most difficult to film because it’s the most boring.

ATTIE: I was always trying to tell Aaron, speech writing’s not anywhere near as glamorous as you’re depicting it here. First of all, it’s Rob Lowe (Sam Seaborn). Second of all, women are swooning at his rhetoric. This is not something a speechwriter ever experienced, but that was the fun of it.

The writers focused on feeding ideas into the Sorkin supercomputer, which would spit out twenty-two cinematic episodes every season about White House senior staff finding love, purpose, and family in their work.

GRAVES: Aaron was like Mozart. I don’t think when he was on the show that there was ever a readthrough where you didn’t just end up being blown away.

REDFORD: Every time he’d deliver a script it was like Christmas. I so looked forward to reading those drafts because they were just flawless.

FALLS: Some mornings I’d follow his car onto the Warner’s lot and he’d be talking to himself. I knew he was going through the scenes in his head, acting them out, finding the musical rhythm.

To balance out the playwright-in-residence came Schlamme, Sorkin’s artistic director. Schlamme and his family had been fortunate enough to spend two nights in the Clinton White House. That visit had an enormous impact on his vision for the show.

SCHLAMME: I remember being outside the Oval Office. The doors open and Henry Cisneros, George Stephanopoulos, and a couple other people come out talking. I was thinking, “That meeting’s still going on.” They could have been ordering lunch, it didn’t matter to me. It felt like, “Oh my god, there’s so many things being juggled. It’s got to continue.” That was the impetus for the idea on the show that meetings never end.

CAHN: People don’t have time to stop and have a conversation. They’re always on their way some where. Everybody is doing three things at a time and thinking about nineteen.

Schlamme captured that essence with his “Walk and Talk” camera style—long Steadicam shots of charac ters drifting though endless winding hallways. He’d successfully used the technique before on The Larry Sanders Show and Sorkin’s Sports Night, but with cinematographer Thomas Del Ruth, he took it to a new level here.

SCHLAMME: I would be on set for hours when no one was there, doing dialogue, trying to figure out if you go through this door and out that door and then

you stop here, because this is an important beat that you’ve got to hear. The goal wasn’t to get it techni cally proficient. The goal was to get it performance proficient. Once we got it on its feet and did it where it all sort of flowed, I ran to Aaron’s office because I couldn’t wait to show him that this works.

That camera style appears in the first scene of the pilot.

SCHLAMME: This is where Leo (John Spencer) takes the audience by the hand and says, “I’m going to show you what this show is.”

It became a trademark of the show, but that didn’t make filming it any easier.

GRAVES: We used to do three-minute takes with fifty extras with props, lines, comedy, and surprises. Directors would come in and say it was going to be

great. You’d be like, “You’re not nervous enough.”

To design the show’s canvas, Schlamme and pro duction designer John Hutman blended existing White House floor plans, such as the Kennedy-era lobby, with their own blueprints, like replacing the Roosevelt Room’s plaster walls with floor-to-ceiling windows.

SCHLAMME : For the most part, there’s trans parency. That’s what we were trying to emotionally relate to. You see people across from people across from people. If you look at when Sam is talking out side the Roosevelt Room, C.J. (Allison Janney) is in the background going into Toby’s (Richard Schiff) office.

The Oval Office, however, demanded authentic ity. They found it in Simi Valley, where Schlamme tracked down a leftover set from Sorkin’s film, The

left President Bartlet is surrounded by his staff in one of the many iconic “Walk and Talk” scenes created by Schlamme, who was inspired by the idea that meetings never end.

opposite

With the idea of transparency in mind, the set designers opened the interior workspaces replacing solid walls with glass. They maintained, however, with precision, the realism of the iconic Oval Office.

American President.

O’DONNELL: I was stunned by the accuracy of the Oval Office. It was truly spooky because it really was the room. It had no ceiling and that stuff outside the windows was fake. But I realized right away, instantly, that this room is really what’s number one on the call sheet.

On the Warner Brothers lot, the actors brought Sorkin’s words and Schlamme’s vision to life.

REDFORD: They were all new to television but at the same time they were very experienced with their own processes, which they brought to Aaron’s writing.

O’DONNELL: I used to say that every script we sent down to that set they made better and they never changed a word.

GRAVES: One of the things I learned was not to direct them until they had acted. I would construct shots, but the flip side was John or Allison would do something that you never thought could happen and you’d throw out your whole shot list and redo the scene.

The producers reached out to some major Hollywood names to play President Jed Bartlet, making offers to Sidney Poitier and James Earl Jones. Neither expressed an interest.

REDFORD: One that got me excited, but I think he was already ill, was Jason Robards, if only because it would have drawn a direct line from The West Wing to All the President’s Men, which I think is the screen play, maybe more than any, that influenced Aaron in his writing about politics.

SCHLAMME: Hal Holbrook was cast for an eve ning. And then Aaron and I thought that’s not quite

right. Hal’s an extraordinary actor, but he wouldn’t be a person who owned a very expensive bike in the Northeast. We both felt we made a mistake, not about Hal, our mistake. And that’s when Martin Sheen entered the conversation.

Sheen’s personality, in certain ways, seemed to mir ror that of a president.

GRAVES: Martin liked to come in and shake every one’s hand on set and say, “How are you friend?” We would lose like fifteen minutes every time we brought Martin to set.

CAHN: It’s in one of the episodes. You can’t tear Bartlet away from a rope line. The fact that Martin found that kind of joy in making everyone feel wel come created a set environment where it stopped being a place where actors come to perform and turned into this thing that had everybody’s soul attached to it.

The casting of Communications Director Toby Ziegler presented a different obstacle: Two amazing actors, Schiff and Eugene Levy, were vying for the same role, from vastly different perspectives.

SCHLAMME: To get Richard to come back to read for the network was so out of the realm of, “You’re so lucky you get to read for the network.” This was not the way Richard saw it. He was like, “I don’t know if I’m going to show up.” All I could say to him was, “I certainly hope you do.” Eugene came in and was fascinating. He’s a really smart guy. I remember his network reading. He was sitting in a chair and I said, “Eugene are you ready? Let’s go.” And there was the longest pause and I thought, “Is this a choice?” You’re always scared to break the moment. I finally went, “So, Eugene, you have the first line. When you’re ready . . .”. He said, “I’m sorry. I was just contemplating a different profession.” It broke up the room.

Sometimes, an actor’s influence changes the course of their character.

REDFORD: Look at the pilot. C.J., ineptly flirting with someone at the gym, falls off the treadmill. It’s very classic and screwball, and you do not see that C.J. ever again. Allison came with such authority and natural ease that that wasn’t C.J. anymore.

Janel Moloney took her role as Donna Moss one step further.

O’DONNELL: There was no part there. Donna Moss was an assistant functionary who was going to help move Josh (Bradley Whitford) from one scene to another. But then Janel Moloney steps into the frame and steals the moment. She becomes some thing much more interesting than she is on the page. She was in effect forcing us to write to her.

GRAVES: There was a funny phrase the crew had: “Three and eight, we’re going late.” On the call sheet, Brad was three and Janel was eight. If they had a Josh and Donna scene there was going to be some work involved because there’d be a great take one, but the choreography wasn’t perfect, or we didn’t get a story nuance, so we’d go again. By the second sea son, you knew that somewhere between take 12 and 25 this thing was going to happen, a kind of kismet, magical, Hepburn and Tracy thing.

Richard Schiff, in the role of communications director Toby Zigler, is seen above on the set of the Roosevelt Room.

Actress Janel Moloney as staff assistant Donna Moss and Bradley Whitford as Josh Lyman had a Hepburn and Tracy chemistry.

Unfortunately, some characters failed to trans late from the page to the stage. Such proved the case with Lisa Edelstein’s character (female escort Brittany [“Laurie”] Rollins) and media consul tant Mandy Hampton (Moira Kelly).

O’DONNELL: Lisa’s character worked in the pilot but I didn’t see a reason to continue it unless she was going to grow into something else. Moira’s great but I knew right away that she had a prob lem. If the show is a workplace drama and you don’t work in the workplace, they’re going to run out of stories for you. It’s an absolute rule.

Every episode balanced multiple character sto rylines, some connected, some standing alone.

FALLS: What was most refreshing is Aaron didn’t want to lock into a network structure. A-story this, B-story that, cliff-hanger act-outs. A character didn’t have to be in every act and a story could take an act off. He gave credit to his audience that they were smart enough to follow.

CAHN: Because the characters were talking about the most important things in the world every second of their life, Aaron usually threw in some piece of profoundly insignificant life stuff. In the pilot, it’s Leo’s frustration with the misspelling in the cross word puzzle. That Aaron was able to metabolize both of those things at the same time gave his stories such a humanity.

The West Wing world proved similar yet different to our own.

REDFORD: I joke about it but the secret stakes of every West Wing were, we have to get a guy’s signa ture. It was the process—passing a law, making an executive order, starting a war. Something.

ATTIE: I always said the prototypical West Wing scene I think Aaron was aiming for was two smart principals, with totally different POVs [points of view], and both of them are right. Whereas the pro totypical Soprano’s scene was two dumb, deluded people arguing and they’re both wrong, which is

also really hard to write.The West Wing world proved similar yet different to our own POVs.

REDFORD: We arbitrarily decided there’d be this rip in the space-time continuum. I don’t even think we named the president who was before Bartlet until after Aaron left.

CAHN: Aaron didn’t need the audience to follow those kind of things. He needed the audience to believe in the authenticity of the environment they were in.

SCHLAMME: It’s a really brilliant hand-eye misdi rection. It gave us the liberty to make The West Wing not necessarily the way it looks today.

ATTIE: The writer’s room joke was that there was a Kennedy Center but it was named after George Kennedy.

FALLS : We even used fictional countries, like Qumar and Equatorial Kindu.

ATTIE: There’s an episode (“Dead Irish Writers”) where the border of Donna’s hometown is read justed so that she’s retroactively a Canadian citizen, which was an idea of mine that was kind of ridicu lous. Aaron just loved it, however. I remember Aaron pitching Tommy that story. Tommy said, “Is that real?” Aaron and I said at the exact same time, “Real enough.”

Sometimes, scripts ran short, like in the Season 1 episode, “In Excelsis Deo,” forcing Sorkin to add a last-minute monologue for the president’s secretary, Mrs. Landingham (Kathryn Joosten).

GRAVES: The pages come down and go around the set. It’s Mrs. Landingham talking about how her sons were killed on Christmas in Vietnam. I’m busy lining up the shot, so, I don’t read them immediately. Then I start to look around the set and everyone’s crying. The dolly grip’s crying. Catering is crying.

REDFORD: That’s one of the things I love about Aaron’s writing. They beat into every TV screenwriter that you can’t do moments like that. It’s a playwright who has an actor say it in one monologue. But what’s wrong with using that here if you have the actor to play it?

Once in a blue moon, an episode ran long, such as in the Season 3 finale, “Posse Comitatus,” in which the president greenlights the assassination of a foreign leader.

GRAVES: Aaron wrote a teaser where Bartlet cuts himself and takes a towel with the Presidential Seal on it and wipes off the blood. The last shot is the towel dropping and there’s blood on the seal. It’s fantastic but Tommy had to cut something. I was like, “If you cut that teaser I will kill myself and leave an ad and say it’s because of you.” I got over it.

No one however, ever touched the rhythm of Sorkin’s dialogues.

FALLS : Oliver Platt (Oliver Babbish) told me that when he met Aaron on his first day of shoot ing, Aaron said, “Have fun, make the role yours.” So Oliver goes back to his trailer with his script, scrib bles some word changes for his character, and then goes to sit and watch John and Martin rehearse. John says to Aaron, “Is it okay if I change ‘and’ to ‘but’ here?” Aaron looks at his script and gives him a respectful, “No.” Oliver went back to his trailer and learned his part as written.

CAHN: The cast became so used to that. The first time that I had a script shooting, Martin came up to me and said, “Can I talk to you for a second?” There was some line like “It’s going to be difficult” and Martin wanted to change it to “It is going to be dif ficult.” He asked me if that was okay. And I was like, “Martin Sheen, whatever you want is okay.”

For the most part, the network left the producers alone, and yet . . .

SCHLAMME: They did some focus groups when our ratings started to come down a little bit. I remember getting a note from them that maybe the president would get in a plane crash with the first lady and then he’d have to start dating.

Sorkin would accept any idea that intrigued him. The writers did lots of research to peak his interest.

REDFORD: Aaron made a vow early on that we all tried to abide by: that every episode would tell the audience something they never knew before about the White House. Like the term POTUS [president

President Bartlet with a cane after his MS diagnosis in Season 2.

of the United States]. In the pilot, nobody knows what POTUS is. That was a total bit of inside infor mation Aaron had picked up when he was doing research for The American President.

ATTIE: There was a historical anecdote I gave about the origin of red tape. After the Civil War, people’s pension documents were bound up in red tape. When widows would come to get the pen sions, they’d cut the tape to open their papers.

FALLS: I had a total Hail Mary. The president gets medical clearance to have sex with the first lady after his assassination attempt. It started out as a joke in the room, but I decided to pitch it to Aaron and then duck. He initially hated it, then came around. It turned into a hilarious scene between Martin and Stockard Channing in the episode “And It’s Surely to Their Credit.”

REDFORD: I burst the origin of Bartlet’s whole MS [multiple sclerosis] story, his secret deal with

the first lady to hide it, and his not running for a second term because then the MS would start to become symptomatic. That’s all based on real his tory. Bartlet’s MS was the story of hiding FDR’s polio. Harry Truman had a deal with Bess Truman not to seek another term because Bess hated the White House.

O’Donnell and Attie mined their Capitol Hill experi ences to help trigger ideas.

ATTIE: There was a storyline in “Swiss Diplomacy” about Josh being squeezed by his former bosses and feeling like everyone was guilting him about his alle giances. That was based on my experiences with [Dick] Gephardt and [Al]Gore, when both of them were looking to run in 2000.

O’DONNELL: The episode Debora wrote about appointing judges (“The Supremes”) was taken directly from some points I made about the unique approach Senator Moynihan had for appointing judges. He’d made a deal with the Republican senator from his state that even when there was a Democratic president, the Republican senator would always get a share of judicial appointments as long as Senator Moynihan always got a share of judicial appointments when there was a Republican pres ident. This worked out fabulously well for Senator Moynihan when we went through twelve years of Republican presidents.

Political consultants, like Gene Sperling, Dee Dee Myers, Pat Caddell, and Marlin Fitzwater also added to the idea cauldron or answered questions.

CAHN: I talked to four different former chiefs of staff for an episode I did about C.J.’s first day as chief of staff (“Liftoff”). The luxury of getting four of those people on the phone was just outrageous.

FALLS: The best consultants are the ones who say, “Well, it wouldn’t go down like that. But here’s a way around your problem that gets you to the same place.” Our consultants were hardwired like that already. Afterall, their job is politics and governing.

Much as the writers loved interacting with real poli ticians, so too did the actors.

SCHLAMME: Clinton came to visit and said he would use the Roosevelt Room more if it was like this because it felt open and available.

GRAVES: Madeleine Albright would come by when we were shooting in Washington and be like, “Alex you should do a story about what’s going on with AIDS in Africa.” And I’d be like, “Sure, Madeleine Albright.”

The actors loved talking politics, too.

ATTIE: Brad was always obsessed with real poli tics. I remember starting to get more interested in Hollywood and going to the set one day with a copy of Variety tucked under one arm. Brad came up to me in between takes and said he woke up in the mid dle of the night worrying about the deficit projections and I’m literally trying to hide my Variety.

At the end of the fourth season, Schlamme and Sorkin left, leaving Wells as show-runner. He wasted little time leaving his imprint.

REDFORD: The head of the network came to hear our pitches for Season 5 and said, “Whatever you do, please don’t do that Middle East story. We’ve done

all the polling and the public does not want any story about the Middle East.” After he left, Wells turned to the room and said, “We’re doing the story about the Middle East.”

GRAVES: I was at Camp David filming an episode and they said John John (Wells) is going to fly out and have dinner with you. I thought, am I being fired? He said they had this idea that maybe we would run again with two new candidates. What happens a lot on campaigns is that the current White House will fragment to support candidates running. If we do that we could depict the campaign process in a way we never have.

The two candidates ended up being moderate repub lican Arnold Vinick (Alan Alda) and democratic minority candidate Matthew Santos (Jimmy Smits).

O’DONNELL: There were different possibilities of where this character (Santos) could go but once it was definitely going to be Jimmy Smits, I started to think about Henry Cisneros because I wanted to think about the reality of a Hispanic politician rising to that level.

ATTIE: I had to write the first two full episodes in

Republican presidential candidate Arnold Vinick (played by Alan Alda) and Democratic candidate Matthew Santos (played by Jimmy Smits) meet with President Bartlet in the Oval Office during Season 7.

Sorkin added interior windows to the Roosevelt Room, a conference room just outside of the Oval Office, opening up the space.

which we really fleshed out the character, so I was looking for any kind of analogue. This is in early ’04. Obama was still a state legislator but already a phenomenon. I’d read in the New York Times that my old friend David Axelrod was his strategist. So, I called David, and he told me a bunch of stories about what life was like for Obama when he exploded as a candidate.

The death of Spencer and seven years on television brought the show to a graceful conclusion in 2006. Sixteen years later, the show continues to resonate.

O’DONNELL: I thought the mission of the show was to be entertaining television. It turns out there were some kids who found their lives in that show and went on to become a speechwriting team for Barack Obama.

FALLS: The most rewarding thing wasn’t how the show elevated me professionally. No, it’s when I hear people say they were inspired by the show to get into government.

CAHN: This whole generation of people exists who are now policy wonks working in D.C. because they wanted to grow up and be these people.

O’DONNELL: I find myself not just impressed with the show but in awe of it, that it could deliver that kind of inspiration to people who would then do something at the highest level of government.

notes

Author’s interviews with Eli Attie, July 12 and 18, 2022; Debora Cahn, August 25, 2022; Kevin Falls, email message, July 18 and 27, 2022; Alex Graves, July 23, 2022; Lawrence O’Donnell, July 26, 2022 and August 11, 2022; Paul Redford; June 14 and 16, 2022; and Thomas Schlamme, April 15, 2022.

come

Getting to Sesame Street With the FIRST LADIES

DIANA BARTELLI CARLIN

DIANA BARTELLI CARLIN

Can you tell me how to get, how to get from Sesame Street to the White House?

take an 8-foot canary, several endearing puppets known as Muppets, animation mixed with live videos of a diverse group of preschoolers, catchy tunes often resembling advertising jingles, a cast of human characters in a welcoming neigh borhood, and an ordinary looking street—and what you have is a formula for one of the most enduring and successful examples of television’s power to teach as well as entertain. Sesame Street, through its beloved characters, has long found a place in the White House that cuts across political party lines. Sherrie Westin, current president of the nonprofit Sesame Workshop and a member of the George H. W. Bush administration, explains why the partner ship works: “I think it’s been because we’ve always focused on the needs of young children, and so that’s not a partisan issue. That’s something we can all agree on. I think it’s because we’ve stayed true to our mission and focused on what is in the best interest of preschoolers, and with particular pro grams, it is a natural alignment. There is no politi cal focus on one administration over another.”1

When Sesame Street premiered on November 10, 1969, it was the product of a collaboration between award-winning documentary producer Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett, a psychologist and Carnegie Corporation vice president. Inspired by a dinner party conversation about Morrisett’s daughter’s infatuation with television—including the test patterns ahead of the real show—the two set out to answer this question: Do you think tele vision could be used to teach young children?2 At the time, Carnegie was funding research on early childhood education, especially for children from disadvantaged environments who were unpre pared for school success. Through Carnegie fund ing, Cooney consulted with experts on television’s teaching potential and created a concept that has educated children and helped adults educate chil dren, including through White House collabora tions, for more than fifty years. [?]

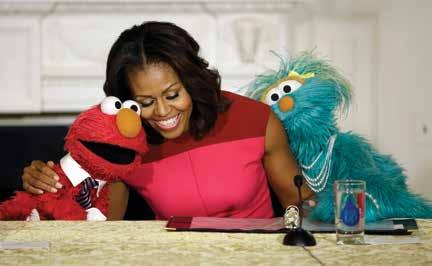

The rich history of the intersection of Sesame Street and 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue demon strates the ongoing commitment of presidents and first ladies to children and their recognition of television’s power to enhance that commitment. Cast and characters’ visits to White House holiday parties and special events align with Sesame Street’s mission to promote literacy and basic math and sci ence skills. Appearances by first ladies on the show enhance the show’s mission and advance White

House projects. Even after presidential families leave the White House, collaborations continue.

THE BEGINNINGS

Less than two months after Sesame Street first aired, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, counselor to the presi dent and member of the Domestic Policy Council, sent a memorandum to President Richard Nixon’s staff secretary with a suggestion that began the long relationship between the children’s televi sion show and the White House. Moynihan wrote: “The new program called Sesame Street on National Educational Television has already shown itself to be so popular and so well done that I think the President would want to send a note to its director. We would be happy to provide additional informa tion if you like.”3

Three weeks later, Nixon sent a letter to Cooney:

The many children and families now benefiting from Sesame Street are participants in one of the most promising experiments in the history of that medium. The Children’s Television Workshop certainly deserves the high praise it has been getting from young and old alike in every corner of the nation.

This administration is enthusiastically committed to opening up opportunities for every youngster, particularly during his first five years of life, and is pleased to be among the sponsors of your distinguished program.4

This letter was not a perfunctory congratulatory message. Moynihan, an academic, understood the show’s potential societal impact. The administra tion’s proponents included First Lady Pat Nixon, whose office arranged for the first Sesame Street White House visit. One memorandum indicated that Mrs. Nixon’s staff requested a performance by several Muppets, but Sesame Street staff thought they were too small to be seen by the large crowd and offered Big Bird and possibly Oscar the Grouch.5 The White House news release about the event provided background on the show’s develop ment and mission and announced, “Sesame Street, TV’s gift to children, will be a special Christmas gift for the children attending the annual Diplomatic Children’s Party on Tuesday, December 22 [1970], at the White House.”6 The five hundred attend ees were treated to a twenty-minute program in the East Room. The event produced an iconic

opposite Big Bird meets First Lady Pat Nixon on his first visit to the White House, December 1970.

previous spread First Lady Barbara Bush was the first first lady to appear on Sesame Street. She is seen here in Episode 2660 with Big Bird, the Count, and children reading Peter’s Chair, 1989.

First Lady Michelle Obama, seen here with Elmo in 2013, often welcomed the muppets to the White House.

photograph of a smiling Pat Nixon looking up at Big Bird while holding one of his feathers. President Nixon sent a thank-you letter to Jason L. Levine, director of public relations for the Children’s Television Workshop, describing the performance as “a special pleasure” and “a highlight of our party for Diplomatic Children.”7