Etiquette Wars and a Celebration at Stephen Decatur’s House

Maria Hester Monroe Marries Samuel Laurence Gouverneur

PORTRAIT: COURTESY

MARY FAIRFAX KIRK PICKLE

white house history quarterly18

WHITE HOUSE WEDDING:

lauren m c gwin

19

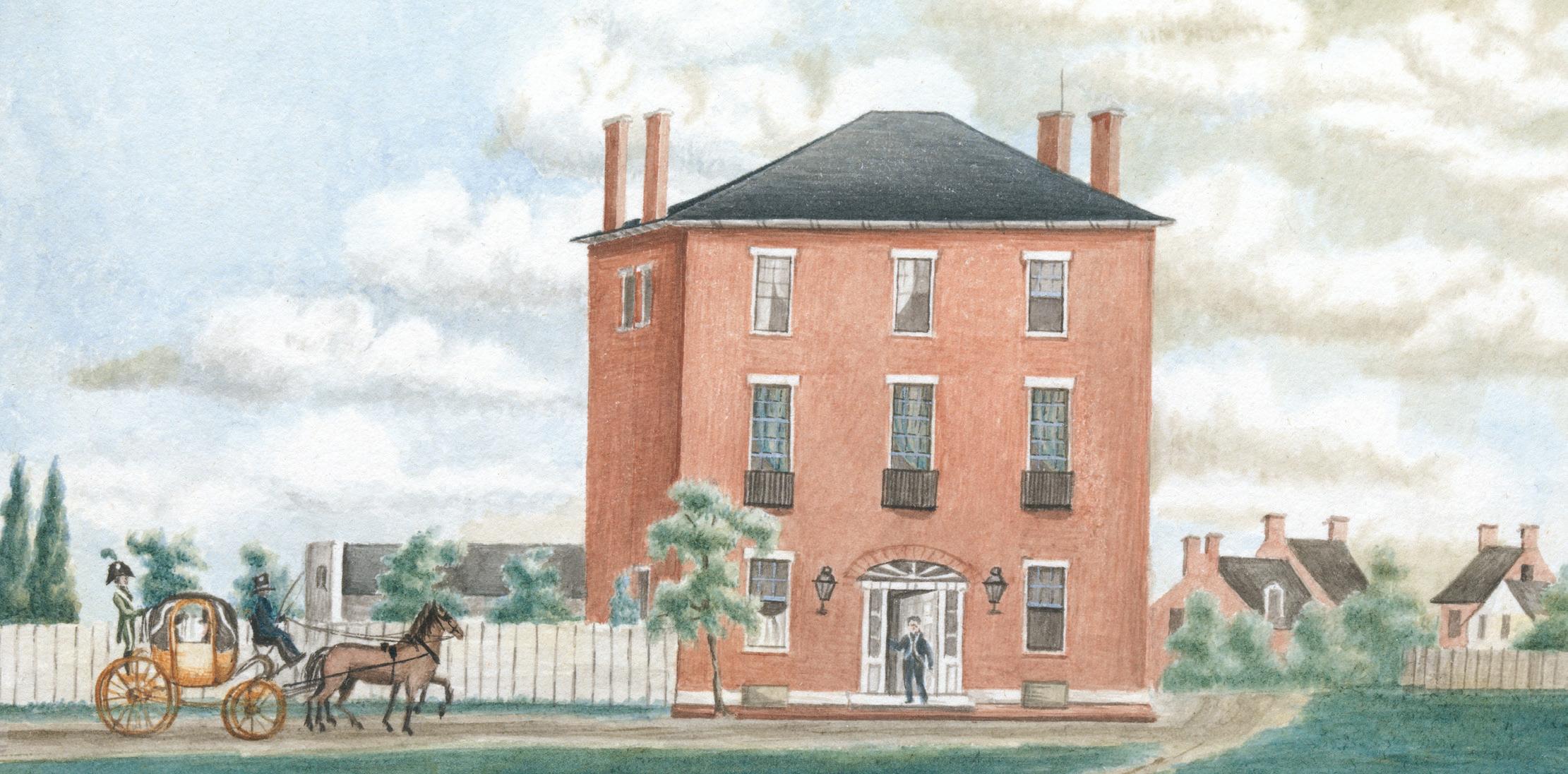

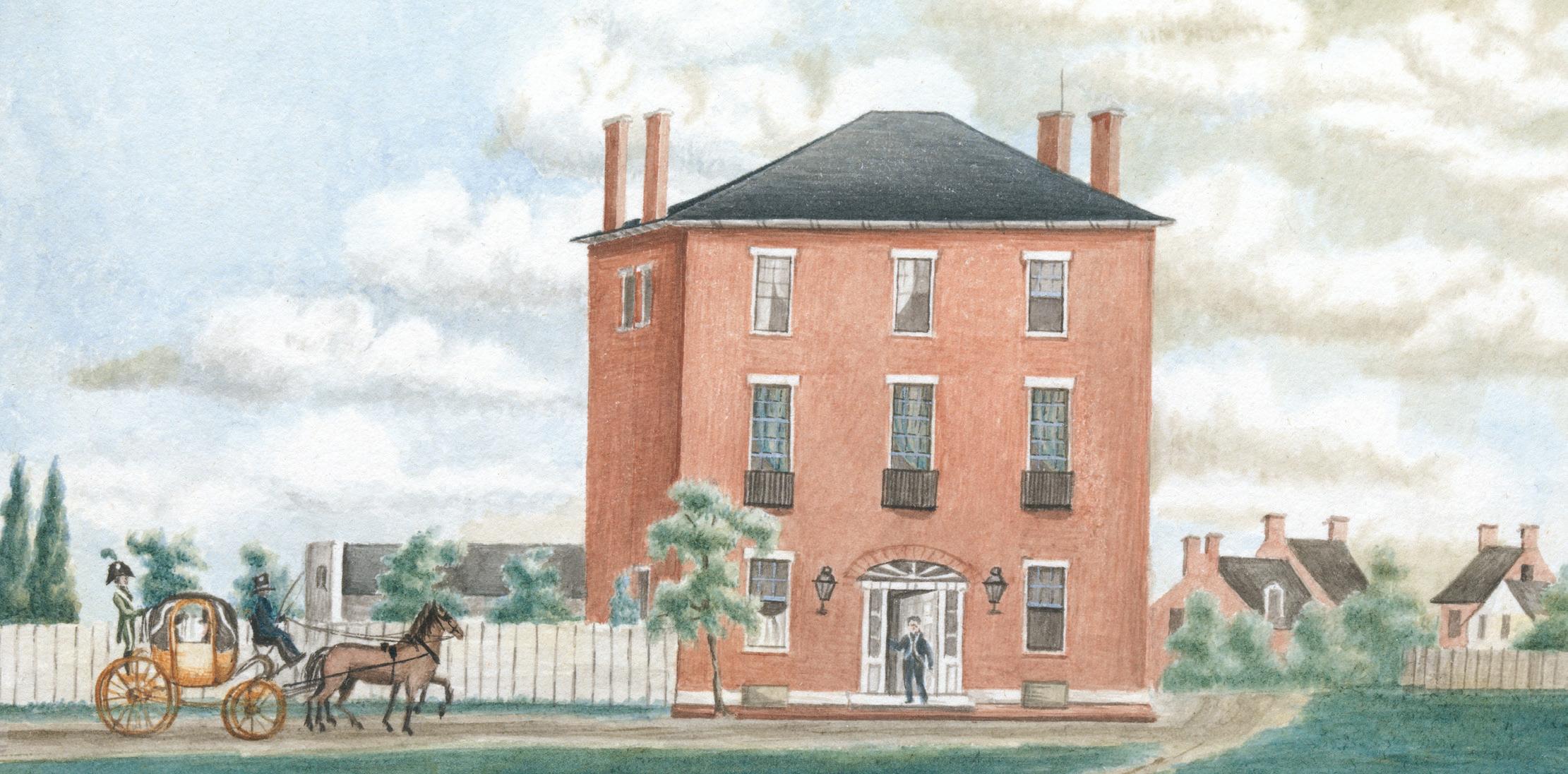

on the evening of saturday , March 18, 1820, carriages transported prominent Washington socialites, poli ticians, diplomats, and naval and army officers along Pennsylvania Avenue to Commodore Stephen Decatur’s new house, “fit for fine entertainments” and designed by the well-known architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. From the elegant front hall they were guided by glittering lamps up the grand winding staircase and received in the second-story drawing room by their illustrious host and his wife Susan. The lamp-lit rooms, furnished with fine furniture and paint ings, along with the prime location of the house on the President’s Square across from the White House, spoke volumes about the wealth and prestige of the naval hero who lived there. It seems fitting that the Decaturs be the first to hold a ball for the president’s daughter, Maria Hester Monroe, on the occasion of her marriage to her cousin Samuel Laurence Gouverneur.

Maria Monroe and Samuel Gouverneur’s wedding was the second to take place at the White House. The first was the wedding of First Lady Dolley Madison’s sister, Lucy Payne

Washington, but the Monroe wed ding was the first marriage of a presi dent’s child. The groom was President Monroe’s private secretary, who had lived at the White House from the be ginning of his administration. As the youngest son of Nicholas and Hester Kortright Gouverneur, a prominent New York family, he was also Maria’s first cousin on her mother’s side and considered quite the catch. He was “a man of decidedly social tastes” and enjoyed throwing lavish entertainments with his wife after their White House years.1 The engagement ring present ed to Maria was a rose-cut diamond placed in a delicate gold setting.2 Four years Maria’s senior at age 21, Samuel doted on his young bride and was heard remarking before the wedding “I con sider myself the luckiest young man in the republic, for the most adorable creature within its borders has chosen me from all her suitors to be a White House bridegroom.”3 The grand ball at Decatur House in honor of the wedding party should have been a celebratory event. Instead, it would be shrouded by political agendas, social intrigue, and the death of Stephen Decatur.

previous spread

It is speculated that this portrait of Maria Monroe, painted c. 1820 by Charles Bird King, portrays her wearing the white satin dress that she wore for both her wedding and a New Year’s Day reception held at the White House that year.

above

This watercolor made by Eugène Vaile in 1822 depicts visitors arriving at Stephen Decatur’s house by carriage as they would have the evening he welcomed society to a wedding reception for President Monroe’s youngest daughter.

opposite

Newspaper announcements provided the only public declaration of the Monroe–Gouverneur nuptials. Today Maria’s wedding ring and sculptural bust are preserved in the collection of the James Monroe Museum and Library in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

white house history quarterly20 WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIAITON

white house history quarterly 21 BAS RELIEF AND RING: JAMES MONROE MUSEUM CLIPPING: GENEAOLOGY BANK

INVITATIONS, SOCIETY, AND ETIQUETTE WARS

Maria Monroe’s wedding was highly anticipated by a Washington society that was accustomed to being included in such occasions, so it came as a bitter dis appointment to a great many who were not invited. Washington society was still getting used to the way the Monroes handled social events in contrast to former President James Madison and First Lady Dolley Madison, whose informality in manners the Monroes actually opposed. During the six years they had lived in Washington while Monroe served in Madison’s cabinet, they rarely entertained. Thus they began their presidential tenure with lit tle favor in society. James Monroe, an experienced diplomat and once min ister to France, sought to model the Executive Mansion after the strict, for mal rules of the European courts in or der to place the United States in a more favorable and sophisticated light with the rest of the world. After all, a second war against Great Britain had been won, and the new nation stood firmly on its own.

To symbolize national pride and the Era of Good Feelings, Monroe furnished the newly rebuilt President’s House richly with French-inspired court furni ture and implemented new formal rules of etiquette that limited interaction with the public.4 First Lady Elizabeth Kortright Monroe, frail, sickly, and unsociable, was constantly compared to the friendly and lively former first lady, Dolley Madison,5 and was said to be aloof, cold, and reserved.6 She was espe cially criticized for not making first calls on the wives of the diplomatic corps and other dignitaries, a practice begun by Dolley Madison.7 Instead, as first lady Mrs. Monroe structured social activi ties at the White House on the model of the European court, where the wives of diplomats called on royalty first.8

John Quincy Adams, secretary of state, and his wife Louisa were friends and advocates of the Monroes and

often defended their actions.9 Louisa Catherine Adams observed, “I am more and more astonished every time I see her [Mrs. Monroe], at the gen eral dislike she seems to have inspired; and can only account for it from the evident superi ority of her deportment to the Ladies who surround her— She was dressed in white and gold made in the highest style of fashion, and moved not like a Queen . . . but like a Goddess.” 10 John Quincy Adams, knowing the foreign ministers and their wives demanded special attention, advised President Monroe to invite them to the reconstructed White House before it opened to the public for the first time on January 1, 1818. The diplomats were temporarily appeased and the next day “insinuat ed how much they had been gratified by the distinction with which they had been treated at the great house.”11 But because the first lady refused to make social calls, the diplomat’s wives responded in turn, and the resentment festered.

The etiquette of social calls became a widely debated subject. In diplomatic and state letters to President Monroe John Quincy Adams warned:

It has, I understand from you, been made a subject of complaint to you . . . that his wife is equally negligent of her supposed duty, in omitting similar attention to the ladies of every member of either house, who visit the during the session. . . . I never heard a suggestion that it was due in courtesy, from a head of department, to pay a first visit to senators, or from his wife to visit the wife of any member of Congress. . . . When I learnt that there was such an expectation entertained by the senators in general, I quickly learnt from other quarters that,

white house history quarterly22 PHOTOGRAPH BY

GENE RUNION / COURTESY HALTON FAMILY

opposite

The snobbish demeanor of Eliza Monroe Hay, eldest daughter of President James Monroe, alienated her from Washington society. Acting as White House hostess in place of her ailing mother, Eliza dominated the planning of Maria Monroe’s wedding, offending those who were not invited to the White House ceremony. This miniature by S. Caruson, c. 1810, captures Eliza in her twenties.

if complied with, it would give great offence to the members of the House of Representatives unless extended also to them. These visits of ceremony would not only be a very useless waste of time, but incompatible with the discharge of the real and important duties of the departments. . . . In paying the first visit to ladies coming to this place as strangers, Mrs. Adams could draw no discrimination; to visit all would be impossible.12

Adams continued to describe what he considered the absurdity of society’s expectations in his diary on January 22, 1818:

All ladies arriving here as strangers, it seems, expect to be visited by the wives of the heads of Departments, and even by the President’s wife. Mrs. Madison subjected herself to this torture, which she felt very severely, but from which, having begun the practice, she never found an opportunity of receding. Mrs. Monroe neither pays nor returns any visits. . . . My wife informed Mrs. Monroe that she should adhere to her principle, but not on any question of etiquette, as she did not exact of any lady that she should visit her.13

Speaker of the House Henry Clay even told Louisa Catherine Adams that he “intended to bring a bill to the house on the subject of etiquette,” an indication of how important the matter of etiquette had become and how quickly it had escalated.14

Much of the controversy over et iquette actually stemmed from the actions of the Monroes’ eldest daugh ter, Elizabeth Monroe Hay, called Eliza, who, because of her mother’s failing health, had assumed the role of first lady. She lived in the White House with her husband George Hay, a prom inent New York attorney. Having been

educated in Paris at the well-known boarding school of Madame Campan, the former lady-in-waiting to Queen Marie Antoinette, she had adopted the European court customs and a snob bish attitude.15 If Elizabeth Monroe was responsible for starting the etiquette war, Eliza Hay fueled the fire. And it was the arrogant Eliza who planned her younger sister’s wedding.

WEDDING AT THE WHITE HOUSE

Maria Monroe, seventeen years younger than Eliza, was often described as “plain and big-boned” and shy, and she was easily overshadowed by her domineering sister.16 Ever concerned with etiquette, Eliza did not believe her 17-year-old sister could manage plan ning the wedding and subsequent White House receptions, known then as “draw ing rooms.” Acting as first lady, Eliza took over the responsibility. Instead of following the social Virginia-style wed ding popularized by Dolley Madison, Eliza modeled Maria and Samuel’s wedding on the private New York style, inviting only a select few. Sarah Seaton, wife of journalist and future mayor of Washington, D.C., William Winston Seaton, said, “The New York style was adopted at Maria Monroe’s wedding. Only the attendants, the relations, and a few old friends of the bride and groom witnessed the ceremony.”17 Thus Maria’s wedding became collateral damage in the etiquette war Eliza was fighting with society. John Quincy Adams, writing on the day of the wedding, explained the impetus for a private wedding:

There has been some further question of etiquette upon this occasion. The foreign Ministers were uncertain whether it was expected they should pay their compliments on the marriage or not, and Poletica, the Russian Minister, made the enquiry of Mrs. Adams. She applied to Mrs. Hay,

white house history quarterly 23

the President’s eldest daughter, who has lived in his house ever since he has been President, but never visits at the houses of any of the foreign Ministers, because their ladies did not pay her first calls. Mrs. Hay thought her youngest sister could not receive and return visits which she herself could not reciprocate, and therefore that the foreign Ministers should take no notice of the marriage; which was accordingly communicated to them.18

Because the wedding was pri vate, there are few accounts of the event. The newspapers carried only an announcement: “On Thursday the 9th inst. in Washington City, by the Rev. Mr. Hawley, Samuel Laurence Gouverneur, of New-York, to Miss Maria Hester Monroe, youngest daughter of James Monroe, President of the United States.”19 Some details can, however, be pieced together from memoirs and dia ries. Although close friends and advis ers to the Monroes, the Adamses were not invited to the wedding, but Louisa Catherine Adams gleaned information that she recorded in her diary. Of the wedding day, she wrote, “The day was uncommonly rainy and stormy & I remained at home all day—Saw no one and heard nothing.”20 The next day the Adamses dined at Colonel John Tayloe’s and heard whispers of the wedding and of those who felt slighted by not receiv ing an invitation:

We heard a great talk of the wedding and as usual many ill natured remarks. . . . I have heard nothing concerning the ceremony except that there were 7 bridesmaids and 7 Bridesmen and a very handsome supper at which 42 persons sat down—There are to be two Drawing Rooms on Monday and Tuesday next. . . . I mentioned that the Corps Diplomatique were not to

be admitted on the occasion to the Ladies and they were all excessively shocked.21

Much later, Maria’s daughter-in-law Marian Campbell Gouverneur wrote a description of the wedding in her memoir:

Only the relatives and personal friends attended; even the members of the Cabinet were not invited. The gallant General Thomas S. Jesup, one of the heroes of the War of 1812 and Subsistence Commissary General of the Army, acted as groomsman to Mr. Gouverneur.22

The wedding ceremony took place on the State Floor of the White House, most likely in the “Elliptical Saloon” (today’s Blue Room), because the larg er East Room was unfinished. The Blue Room was where the president

below and opposite

Portraits of the bride’s parents are displayed today in the Elliptical Saloon (today’s Blue Room) in which she was married. First Lady Elizabeth Monroe (below on far left) and President James Monroe (opposite) look down on the collection of recently regilded Bellangé furniture, which they acquired for the President’s House in 1818.

white house history quarterly24 WHTIE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

most often received official guests, and its elegance and grandeur were often remarked on. One visitor wrote: “We entered a Saloon which is elyptical— crimson papering, with rich gilt bor dering. The windows are corniced with large, gilded, spread eagles. . . . This is a most splendid room.”23 Furnished to impress, this room would have been perfect for the important occasion of the president’s daughter’s wedding.

The ceremony was officiated by the Reverend William Hawley from St. John’s Episcopal Church, located just across President’s Park, and afterward the forty-two guests were invited to dine in the State Dining Room.24 There is no clear record of the wedding dress Maria wore, but one writer speculated it was the same dress of white satin that she had previously worn to the New Year’s Eve reception at the White House.25 At

this time, and until the late nineteenth century, it was common for a bride to wear a gown of colored fabric that could be used at other social functions after the wedding. The young couple discour aged gifts, but they did receive silver flatware in the Old Maryland pattern and a pair of Sheffield plate candlesticks engraved with the Gouverneur crest from the president and first lady.26

The day after the wedding, the young newlyweds left for a three-day honey moon trip, returning to a full schedule of festivities in Washington to celebrate their marriage. On Monday, March 13, and Tuesday, March 14, the White House hosted two official wedding “drawing rooms.”27 The president and first lady mingled with guests at both parties, while Maria received as host ess.28 The Adamses were among the guests, but the invitation list remained selective. Family tensions over the wed ding were not yet forgotten. The groom, Samuel Gouverneur, harbored bitter sentiments toward his wife’s family for not allowing the wedding couple to plan their own wedding. He believed his wife should have been able to invite anyone she wanted to the ceremony. To com pensate, Samuel and Maria planned a series of celebratory balls hosted by prominent members of Washington society. These they wanted to be as in clusive as possible, thus appeasing the diplomats and members of Washington society who were not invited to the wedding. The Gouverneurs would also gain freedom from the interfering sis ter, Eliza. On March 18, 1820, nine days after the wedding, the first ball took place at the home of Commodore Stephen Decatur and his wife Susan.

FESTIVITIES AT DECATUR HOUSE

Situated so close to the White House, Stephen and Susan Decatur’s house was an ideal location and its owner the ide al host to be chosen for the first ball. A

white house history quarterly 25

WHTIE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

richly rewarded naval hero and celebri ty for his heroic actions in the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812, Decatur was a much-loved and prominent mem ber of society and a “special favorite of President Monroe and his Cabinet”29 Attending a ball at his house would have been a social highlight and a way for the Gouverneurs to return to society’s good graces.

Stephen Decatur’s brick three-story house, built with prize money awarded for the capture of the British frigate Macedonian during the War of 1812, had been designed by Latrobe with entertainment in mind. The second story was intended for just such a gala as a wedding party. There was a formal dining room on the left and a draw ing room on the right, with a “com pany room” or guest bedroom to the rear. Doors to these rooms would have remained closed. When the doors were drawn open for entertainment, a steady flow of guests could parade throughout the rooms. According to a later inventory, the dining room lacked a large dinner table and chairs, which would have impeded the flow of guests around the rooms. Instead, it is likely that folding card tables pulled togeth er and covered with cloth were used as dining tables. Since the house was newly built, the plaster walls were cov ered with wash and no wallpaper ap plied. The second-story windows, de signed by Latrobe to be taller than the others, had shutters left open so passers by could admire the sight and sound of the festivities within.30

Guests arriving at the Decaturs would have been dressed in the height of fashion, and that meant French fash ion. French Empire style (1804–15) was adopted in America through the pro liferation of fashion publications and illustrations that portrayed high-waist ed dresses with short puffed sleeves and long loose skirts that created a straight silhouette. Emulating admired mem bers of society, such as Dolley Madison,

who wore an Empire-style dress in her 1804 portrait by Gilbert Stuart, also helped spread the fashion. The sheer, narrow dresses caused a sensation at the beginning of the nineteenth cen tury because of their contrast to the elaborate hooped costumes of previous decades. Different types of clothing began to be held appropriate for dif ferent occasions and times of the day. The stylish “walking dress” was worn for daytime promenades and socializ ing, whereas “full dress” meant evening attire suitable for a ball. The difference was the amount of skin shown. Evening necklines were lower, and the arms were often exposed.31

Artist Riley Sheehey recently envisioned the grand Decatur House ball held for the newlyweds. As Susan Decatur plays the harp, guests seated in a semicircle enjoy the music. As Stephen Decatur devotedly watches her play, his anxiety about the forthcoming duel is obvious.

white house history quarterly26

RILEY SHEEHEY FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

The women invited to Decatur House that evening would surely have been in “full dress,” but by the 1820s the Empire style began to be modified and their ball gowns would have been more embellished, the circumference of the hem gradually increased, and the waistline slightly lowered.32 Stephen Decatur wore full naval regalia, as did guests also from the navy and the army, while foreign diplomats and members of Monroe’s administration would have been wearing colorful high-cut coats with tails, perhaps in green or clar et, to match the silhouette adopted by women.33

Decatur’s ball was meant to be the

launch of a “week . . . destined to be the gayest of the season” with balls planned for every night of the week for the bride and groom.34 The glamour of the fur nishings, company, and refreshments, and the gaiety of the dancing and music created an impressive evening memora ble for all who attended. Few knew the threat of death hanging over Decatur. Even his wife was blissfully unaware of the impending duel as she played the harp for the guests. Months later, practicing her harp would help Susan Decatur “as a resource from ennui these long Evenings and to soothe her deep sorrows.”35 One of the most detailed accounts of the ball was written by a

white house history quarterly 27

youthful Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, later an influential businessman and diplomat. In his memoir he focused on Stephen Decatur:

From my own observation, I am sure Commodore Decatur foresaw the hazard of his position. The day preceding the duel I met Commodore Decatur. He looked ill, and seemed abstracted. The Saturday before, I was at a party at his house. He seemed out of spirits, and I was particularly struck with the solemnity of his manner and his devotion to his wife and her music, as she played upon the harp, the company forming a semicircle in front of her, Decatur himself, in uniform, the centre of the semicircle, his eyes riveted upon his wife. The party was given to Mrs. Gouverneur,

the daughter of President Monroe, then a bride. The Misses Douglas, of New York, afterwards Mrs. Cruger and Mrs. James Monroe, were among the guests. . . . The next week there was to have been a similar party at Commodore Porter’s. In the course of the evening, Decatur said to Porter, his confidant, “I may spoil your party.”36

Decatur’s prediction rang true. Although one more small party did take place, hosted by the Adamses on Tuesday, the following eve ning, on Wednesday, March 22, Decatur died in his office from a wound sustained at the famous duel against Commodore James Barron in Bladensburg, Maryland. Louisa Catherine Adams wrote that same day:

The shocking news of Com Decaturs being mortally wounded in a Duel with Com Baron—My blood Ran cold as I heard it and Mr: A—immediately went off to see him and offer every assistance in his power I followed and when I got there was informed that there were faint hopes of his life—The whole Town was in a state of agitation & a great part of the day his door was crowded with people waiting the sad event—He expired at eight oclock last evening to the grief of the whole Nation who will long mourn the loss of a favourite Hero whose amiable qualities as a private Citizen intitled him to the esteem of all whose esteem & friendship were worth possessing—His style of living has excited some envy in narrow minded people for such there are & such there ever will

Today a portrait of Commodore Decatur hangs in the second floor parlor of his home overlooking Lafayette Square, where he hosted a grand ball to celebrate the wedding of the president’s daughter shortly before losing his life in a duel. He died on the first floor of the house.

white house history quarterly28

BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

be Incapable of such exertions as will promote their own interests & envious of all who rise to eminence they gratify their spleen by the basest calumnies.37

The nation was devastated, and the bridal festivities forgotten. Margaret Bayard Smith, prolific writer of Washington society, stated, “Commodore Decatur’s death, was a striking and melancholy event. . . . From the moment Decatur fell, nothing else was thought of.”38 Sarah Seaton added, “But the bridal festivities have received a check which will prevent any further at tentions to the President’s family, in the murder of Decatur! The first ball, which we attended, consequent on the wedding was given by the Decaturs! Invitations were all out from Van Ness, Commodore Porter, etc., all of which were remanded on so fatal a catastrophe.”39 While Washington society was recover ing from their shock of Decatur’s tragic death, they were at least momentarily distracted from the obsession with eti quette. The Gouverneurs’ plan had suc ceeded. Even though the bridal celebra tions ended abruptly, the only ball held was a significant one. As the final ball to ever be hosted by Stephen Decatur, it made a lasting impression.

When President Monroe’s term ended in 1825, Maria and Samuel moved to Oak Hill, the Monroe family plantation in Virginia, along with the former president and first lady. When Samuel became a member of the New York State Assembly, the Gouverneurs moved to New York; he later served as postmaster of New York City, 1828–36. While in New York Samuel invested in racehorses and the Bowery Theater along with James Alexander Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton’s son. Together, Maria and Samuel had four children— James Monroe, Elizabeth, Samuel L. Jr., and a daughter who died in infan cy. Former President Monroe moved to New York to live with Maria when his

wife Elizabeth died in 1830, and on July 4, 1831, he died from heart failure and tuberculosis. The Oak Hill estate was willed to Maria but was sold to pay off her father’s debts. Maria passed away in 1850 at the age of 47. Many of the family possessions, including Maria’s wedding band, have been donated and remain in the collection of the James Monroe Museum and Library in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Maria’s son Samuel Jr. wrote just after his mother’s death, “A man through life has but one true friend and that friend generally leaves him early. Man enters the lists of life but ere he has fought his way far that friend falls by his side; he never finds another so fond, so true, so faithful to the last—His Mother!”40

NOTES

1. George Morgan, The Life of James Monroe (Boston: Small, Maynard and Company, 1921), 417.

2. Marie Smith and Louise Durbin, “Monroe Wedding Stormy,” Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1966, 15.

3. Quoted in Gilson Willets, Inside History of the White House (New York: Christian Herald, 1908), 270.

4. William Seale, The President’s House, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), 1:151, 155.

5. Esther Singleton, The Story of the White House (New York: McClure Company, 1907), 1:132.

6. Seale, President’s House, 1:143.

7. Allida Black, First Ladies of the United States of America, 14th ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2017), 15.

8. Doug Wead, “Maria Hester Monroe: An Event Marred by Murder,” in All the President’s Children: Triumph and Tragedy in the Lives of America’s First Families (New York: Atria Books, 2004), 223.

9. Singleton, Story of the White House, 135.

10. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams to Abigail Smith Adams, January 15, 1818, online at Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov.

11. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, January 2, 1818, https://founders.archives.gov.

12. Letter of December 25, 1819, quoted in William Winston Seaton, William Winston Seaton: A Biographical Sketch (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1871), 138–39.

13. Quoted in Singleton, Story of the White House, 133.

14. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, December 14, 1818, https://founders.archives.gov.

15. Wead, “Maria Hester Monroe,” 223. Louisa Catherine Adams described Elizabeth Monroe Hay in her diary on January 7, 1818, http:// founders.archives.gov.

16. Wead, “Maria Hester Monroe,” 223.

17. Singleton, Story of the White House, 148.

18. Quoted in ibid., 147. “Poletica” is Pyotr Ivanovich Poletika.

19. “Married,” New Hampshire Sentinel, March 25, 1820, genealogybank.com. Many newspapers carried the same announcement.

20. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, March 9, 1820, https://founders.archives.gov.

21. Ibid., March 10, 1820.

22. Marian Campbell Gouverneur, As I Remember: Recollections of American Society During the Nineteenth Century (New York and London: D. Appleton and Company, 1911), 258.

23. Robert Donaldson, “Notes on a January Through the Most Interesting Parts of the United States and the Canadas,” January 16, 1819, quoted in Betty C Monkman, The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and First Families, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2014), 62.

24. Wead, “Maria Hester Monroe,” 221.

25. Smith and Durbin, “Monroe Wedding Stormy,” 15.

26. Ibid, 15.

27. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, March 10, 1820, http://founders.archives.gov.

28. Morgan, Life of James Monroe, 416.

29. Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, In Memoriam: Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, comp. Winslow M. Watson (Philadelphia: Sherman & Co., Printers, 1872), 160.

30. The inventory taken of Stephen Decatur’s house after his death lists “6 pine tables” used during the reception as make-do dining tables. “Inventory of goods, chattels & Personal Estate of Stephen Decatore [sic], deceased, April 27, 1820,” Inventory & Sales, No. 1—J.H.B., H.C.N., Office of Register of Wills, July 1, 1818 to April 20, 1821, Probate Court Records of the District of Columbia, Record Group 21, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Description of architecture from Michael Fazio, “A Rational House with Complications,” in The Stephen Decatur House: A History (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2018), 196–97.

31. Mary Doering, “The Age of Revolution in Fashion, 1700–1824,” lecture, fall 2012, Smithsonian Associates, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

32. Ibid.

33. Marie Beale, Decatur House and Its Inhabitants (Washington, D.C.: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1954), 3.

34. Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Scribner’s Sons, 1906), 150.

35. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, December 3, 1820, https://founders.archives.gov.

36. Tayloe, In Memoriam, comp. Watson, 161.

37. Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams, diary, March 22, 1820, http://founders.archives.gov.

38. Smith, First Forty Years, ed. Hunt, 150–51.

39. Quoted in Singleton, Story of the White House, 148.

40. Quoted in Gouverneur, As I Remember, 257, 259.

white house history quarterly 29