9 minute read

National

NEWSPAPER READING IS A HABIT

DON’T BREAK THE HABIT!

READ THE WASHINGTON INFORMER YOUR WAY:

n In Print – feel the ink between your fingers of our Award Winning Print Edition n On the Web – www.washingtoninformer.com updated throughout the day, every day n On your tablet n On your smartphone n Facebook n Twitter n Weekly Email Blast – sign up at www.washingtoninformer.com

202-561-4100 For advertising contact Ron Burke at rburke@washingtoninformer.com

...Informing you everyday in every way

THE WASHINGTON INFORMER NEWSPAPER (ISSN#0741-9414) is published weekly on each Thursday. Periodicals postage paid at Washington, D.C. and additional mailing offices. News and advertising deadline is Monday prior to publication. Announcements must be received two weeks prior to event. Copyright 2016 by The Washington Informer. All rights reserved. POSTMASTER: Send change of addresses to The Washington Informer, 3117 Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave., S.E. Washington, D.C. 20032. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. The Informer Newspaper cannot guarantee the return of photographs. Subscription rates are $55 per year, two years $70. Papers will be received not more than a week after publication. Make checks payable to:

THE WASHINGTON INFORMER 3117 Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave., S.E Washington, D.C. 20032 Phone: 202 561-4100 Fax: 202 574-3785 news@washingtoninformer.com www.washingtoninformer.com

In Memoriam Dr. Calvin W. Rolark, Sr. Wilhelmina J. Rolark

PUBLISHER

Denise Rolark Barnes

STAFF

D. Kevin McNeir, Senior Editor, Copy Editor Ron Burke, Advertising/ Marketing Director Shevry Lassiter, Photo Editor Lafayette Barnes, IV, Assistant Photo Editor Dorothy Rowley, Online Editor ZebraDesigns.net, Design & Layout Mable Neville, Bookkeeper Tatiana Moten, Social Media Specialist Angie Johnson, Circulation

REPORTERS

Stacy Brown (Senior Writer), Sam P.K. Collins, Timothy Cox, Will Ford (Prince George’s County Writer), Hamil Harris, Curtis Knowles, Daniel Kucin, D. Kevin McNeir, Dorothy Rowley, Brenda Siler, Lindiwe Vilakazi, Sarafina Wright, James Wright

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Shevry Lassiter, Roy Lewis, Jr., Robert R. Roberts, Anthony Tilghman 5 Dr. Shantella Sherman (Photo by India Kea)

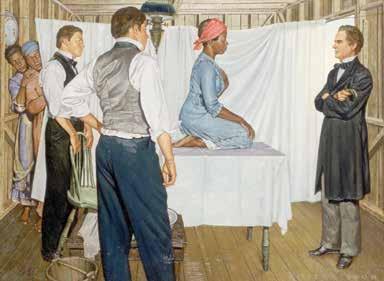

It’s Time for an End to Female Trouble

Dr. Shantella Y. Sherman Informer Special Editions Editor

Edgar G. Mathis, of Manor Texas, wrote in 1900 that he had operated on a Black woman to remove a large uterine fibroid and felt to the need to document the condition, “noting the meager literature concerning this rare form of neoplasm” among African Americans. Mathis’ operational notes – now more than a century old – read like the constant stream of articles, blogs, and research related to Black women and fibroids. That rare condition is shared, according to recent data from the Black Women’s Health Imperative (BWHI) and Hologic, by

more than 26 million Americans.

“Because of the health disparities, devastating impact, and effects of uterine fibroids -- and to save and extend the lives and well-being of Black women -- BWHI commissioned the white paper to amplify the voices of Black women to advance health equity and shift the public perception and policies for social change,” said Tammy Boyd, JD, MPH, chief policy officer and counsel for Atlanta-based BWHI. “The widespread prevalence and disabling nature of uterine fibroids among Black women often surprises some clinicians.”

Boyd found the existence of disparities in diagnosis and care of uterine fibroids result in Black women waiting longer than white women before seeking treatment: normally 4 years of more – which potentially exacerbates their conditions. This results in Black women experiencing more incidents of severe pelvic pain and anemia due to heavy bleeding.

“By any measure, these statistics and outcomes are dire and indicative of a pressing public health crisis,” Boyd said.

Still, little is known about what causes fibroids or how to definitively treat them – without resorting to hysterectomies. In fact, many Black women still approach anything gynecological as off limits, taboo, or shameful. As a result, the “female trouble” our elders whispered about, remains a painful and hidden heritage.

During a 2-day roundtable by the Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR) in Washington, D.C., expert researchers, gynecology-focused health care providers, patients, patient advocates and policy leaders discussed key deficits in research, clinical care, and federal policies. They noted advancements in treatment, including non-hormonal medical therapies that were also fertility-friendly, and the potential if Vitamin D to provide protective effects against fibroid growth without negatively impacting ovarian function.

Additionally, SWHR highlighted the research of The Study of Environment, Lifestyle, and Fibroids – the first prospective study to identify incident fibroid cases based on ultrasound screenings and is specifically designed to investigate African ancestry, vitamin D deficiency, and reproductive tract infection as risk factors for fibroid incidence.

Many offerings of the discussion centered around the science of fibroids, but in equal measure were bed-side manner suggestions that would foster trust between Black women and their physicians.

“We suggest reconsidering a patient’s use of the word ‘normal’ or ‘fine’ when describing menstrual flow or pain because they may not realize that their normal may actually warrant medical concern,” said SWHR Director of Science Programs Irene Aninye. “Quantifying the use of feminine products or the duration of pain and its influence on daily activities is likely to better inform an assessment.”

With so much to unpack, The Washington Informer offers a quick glimpse at information and resources available to our readers to approach fibroids head on, and seek a relief from “female trouble,” without delay or embarrassment.

Read, Learn, Heal. Dr. Shantella Sherman

Researchers Revisit Theories on the Origins and Prevalence of Fibroids among Black Women

By Lindiwe Vilakazi WI Staff Writer

While the cause of fibroids remain a mystery to most researchers, our recent steps (and missteps) with the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted the persistence of bias and racism in medicine. Whether rooting in issues of access, policies, practices, or stereotypes, Black women appear to suffer at greater rates from fibroids than their counterparts.

To address this gap in the literature, the University of Maryland proposed a study, Examining Racism as a Risk Factor for Uterine Fibroids among African American Women, to collect data from 699 African American women in the southern region of the United States. This study examined the relationship between perceived and internalized racism and uterine fibroid diagnosis among African American women. The study revealed a direct effect between perceived racism and the likelihood of a uterine fibroid diagnosis.

Sherilynn Prosser was 14 when diagnosed with endometriosis – a painful condition caused by uterine material growing outside the uterus and causing cramps and excessive bleeding with monthly hormonal changes. Her gynecologist told her it was a condition most Black were predisposed to developing and that there was no exact cure or remedy. She said it felt as if her physician had simply said, “suck it up,” and moved on. It wasn’t until thirty years later when she was diagnosed with uterine fibroids, that she began asking questions.

“I allotted a certain amount of time each month to suffer in silence; I never questioned the diagnosis or treatment until my husband and I were expecting our first child and a sonogram showed the baby sharing womb space with a fibroid,” Prosser said. “Suddenly I had questions about if the two conditions were connected – and if the way I’d been brushed aside as a teen kept me assuming the fibroids were just the endometriosis acting up.”

Prosser is not alone.

Black women are more likely than white women to have uterine fibroids, and the debilitating symptoms often leave them feeling fearful, depressed, helpless, and alone. Many African American fibroid sufferers say they have often had their questions or concerns brushed aside or had their fibroid symptoms misdiagnosed as sexually transmitted infections or unplanned pregnancies.

One survey from October 2020, for instance, found that of 777 Black adults polled in the United States, one in five said they had experienced race-based discrimination in health care settings within the past year. Black women in particular, the study found, were most affected.

Hilda Hutcherson, M.D., a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and a dean at Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, said stress may be related to fibroid risk.

“We don’t fully know what causes fibroids or why they’re more prevalent among Black women, though research suggests that stress may be associated with an increased fibroid risk. Some researchers theorize that a lifelong exposure to racism, combined with limited access to medical resources and a lower overall quality of care, might help explain this disparity in fibroid diagnoses,” Hutcherson said. “There is also preliminary research that shows that hair relaxers — chemicals used by millions of Black women — are associated with higher incidence of fibroids.”

In research first introduced in 1992, phthalates – a substance added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, durability, and longevity – was also present in chemical no-lye hair relaxers. There was an association made between lesions, scalp burns, and the development of fibroids.

Dr. Sophia Sparks, a Dallas-Fort Worth scientist, though, said the science simply does not support conclusively that racism or hair relaxers cause fibroids. Sparks also believes the medical community does a disservice in making racial comparatives in some research.

“There are so many chemicals introduced to the body on a regular basis that it is impossible to say when, where or how they interact with the body once internalized. Phthalates are in no-lye hair relaxers, but also in the plastics and packaging that we use every day – they are used in the chemical coating on pizza boxes to keep them from being greasy, for instance,” said Sparks, who also acknowledged the existence of compounds the FDA labeled safe by themselves, but harmful when introduced to other compounds.

“Fibroids are not a Black women’s issue – they are a female and environmental issue. Instead of looking at fibroids from the position of race, it may be more accurate and logical to do so economically. The truth is that every woman is at risk for fibroids, period,” Sparks said. HS

Our Healthy Living Team is available online

giantfood.com/nutrition

Personalized Virtual consultations available by appointment free services include:

• Individual and family consultations • Online classes • Virtual and phone consultations • Corporate wellness seminars and webinars • Healthy Living by GiantTM blog and podcast • Join our Healthy Living by Giant

Facebook page to interact with us anytime and get tips for starting your personal health journey

contact us here